Proc. R. Soc. B 282, 20151766. (Published online 7 September 2015) (doi:10.1098/rspb.2015.1766)

Having been alerted to the presence of two categories of anomalies, Pruitt and the Proceedings B editorial board recently re-examined the raw data file underlying Pruitt & Pinter-Wollman [1], but see Pinter-Wollman [2]. First, an equation leftover from sensitivity analysis for missing and incomplete data was detected which compromised 21 of the 1448 boldness values. Second, a small number of duplicate sequences suggest one or more copy/paste errors during data assembly, possibly affecting a further 148 values. An unknown portion of these values are likely to be in error. To evaluate the impact of these anomalies, they were removed from the data sheet and the analyses were rerun.

The major conclusions of Pruitt [1] were that bold spiders in colonies of social spiders disproportionately increase colonies' collective aggressiveness, and the impacts of these bold spiders on colony behaviour persist after the removal of bold individuals. The duration of these legacy effects further scales with the bold individuals’ former tenure within groups. The 1274 data points underlying these major conclusions did not contain anomalies.

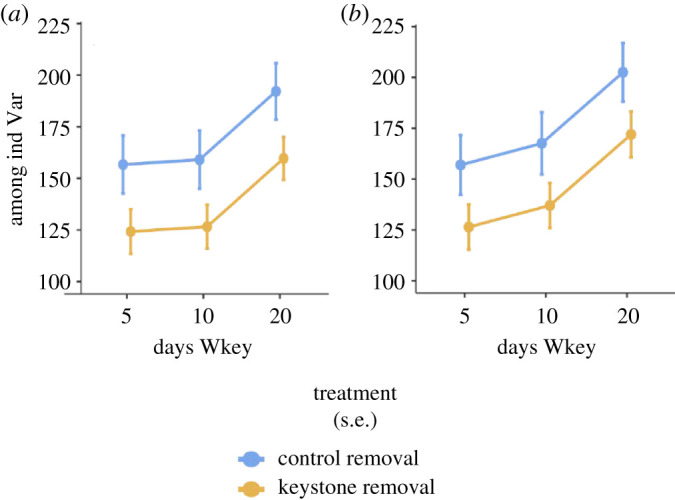

An ancillary finding of Pruitt [1] was that bold ‘keystone’ group members caused the catalysation of greater intraspecific variation in boldness in formerly shy colony members. When the boldness values subject to anomalies were removed and this trend was re-evaluated, a virtually identical pattern is recovered. Bold individuals catalyse greater intraspecific variation in their colonies (table 1 and figure 1). For both analyses, among-individual variation in boldness was used as the response variable in the model, and treatment (adding bold or shy spider) and the latency since an immigrant's arrival (5, 10, 20 days) were included as fixed effects. The presence of the anomalies was therefore not responsible for this ancillary finding and in no manner impacted the study's conclusions.

Table 1.

Test statistics, degrees of freedom and p-values of the combined statistical model, treatment/control removal and days since immigrant's removal terms. The top test statistics are those derived from the original dataset containing the anomalies (original data) and the bottom test statistics were derived from an identical analysis with the anomalies expunged (culled data).

| term | F | d.f. | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| original data | combined model | 4.97 | 3 | 0.004* |

| control/keystone removal | 6.12 | 1 | 0.015* | |

| days since removal | 4.05 | 2 | 0.02* | |

| culled data | combined model | 5.25 | 3 | 0.002* |

| control/keystone removal | 4.79 | 1 | 0.031* | |

| days since removal | 5.15 | 2 | 0.007* |

Figure 1.

Means (±s.e.) of among-individual variation in boldness in formerly shy colony members for colonies that still contained very bold individuals (shy removal controls in blue) versus colonies in which particularly bold spiders had been removed (keystone removal in orange). Depicted on the x-axis are the number of days in which bold (orange) or shy control (blue) immigrant spiders had resided within colonies prior to their removal. (a) Findings from the original article and (b) a reanalysis where the anomalies were expunged. (Online version in colour.)

A final point of clarification in the methods is warranted. The former methods did not explicitly acknowledge that multiple focal spiders were run through their boldness assays simultaneously, rather than one at a time. To run each spider sequentially through these assays would have required approximately 289.6 h of continuous observation and this was not logistically feasible. Furthermore, because stopwatches were used to measure latencies in multiple focal spiders simultaneously, the observer estimated the latency of spiders within a few seconds in real time. This procedure causes some reduced precision and increased subjectivity in these measures.

References

- 1.Pruitt JN, Pinter-Wollman N. 2015. The legacy effects of keystone individuals on collective behaviour scale to how long they remain in a group. Proc. R. Soc. B 282, 20151766 ( 10.1098/rspb.2015.1766) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinter-Wollman N. 2020. Authorship removal correction for ‘The legacy effects of keystone individuals on collective behaviour scale to how long they remain within a group’. Proc. R. Soc. B 287, 20201842 ( 10.1098/rspb.2020.1842) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]