Abstract

In this study, we couple intracellular signalling and cell-based mechanical properties to develop a novel free boundary mechanobiological model of epithelial tissue dynamics. Mechanobiological coupling is introduced at the cell level in a discrete modelling framework, and new reaction–diffusion equations are derived to describe tissue-level outcomes. The free boundary evolves as a result of the underlying biological mechanisms included in the discrete model. To demonstrate the accuracy of the continuum model, we compare numerical solutions of the discrete and continuum models for two different signalling pathways. First, we study the Rac–Rho pathway where cell- and tissue-level mechanics are directly related to intracellular signalling. Second, we study an activator–inhibitor system which gives rise to spatial and temporal patterning related to Turing patterns. In all cases, the continuum model and free boundary condition accurately reflect the cell-level processes included in the discrete model.

Keywords: moving boundary problem, intracellular signalling, cell-based model, continuum model, reaction–diffusion equations, non-uniform growth

1. Introduction

Epithelial tissues consist of tightly packed monolayers of cells [1–3]. Mechanical cell properties, such as resistance to deformation and cell size, and chemical cell properties, such as intracellular signalling, impact the shape of epithelial tissues [2,4]. The role of purely mechanical cell properties on tissue dynamics has been studied using mathematical and computational models [5–10]. Other models focus on intracellular signalling to examine how chemical signalling affects tissue dynamics [11–15]. We extend these studies by developing a model that couples mechanical cell properties to intracellular signalling. We refer to this as mechanobiological coupling. By including mechanobiological coupling in a discrete computational framework, new reaction–diffusion equations are derived to describe how cell-level mechanisms relate to tissue-level outcomes.

Epithelial tissues play important roles in cancer development, wound healing and morphogenesis [2,16,17]. Temporal changes in tumour size and wound width in epithelial monolayers can be thought of as the evolution of a free boundary [18,19]. Many free boundary models use a classical one-phase Stefan condition to describe the evolution of the free boundary [20,21]. In these models, the speed of the free boundary is proportional to the spatial gradient of the density at the moving boundary [20,21]. Other free boundary models, particularly those used to study biological development, pre-specify the rate of tissue elongation to match experimental observations [22–28]. In this study, we take a different approach by constructing the continuum limit description of a biologically motivated discrete model. In doing so, we derive a novel free boundary condition that arises from the underlying biological mechanisms included in the discrete model. While the discrete model is suitable for describing cell-level observations and phenomena [15,29], the continuum limit description is suitable to describe tissue-level dynamics and is more amenable to analysis [30–32].

To confirm the accuracy of the continuum limit description, including the new free boundary condition, we compare the solution of the discrete model with the solution of the continuum model for a homogeneous tissue with no mechanobiological coupling, and observe good correspondence. To investigate mechanobiological coupling within epithelial tissues, the modelling framework is applied in two different case studies. The first case study involves the Rac–Rho pathway where diffusible chemicals called Rho GTPases regulate mechanical cell properties [12,33–38]. We explicitly consider how the coupling between diffusible chemical signals and mechanical properties leads to different tissue-level outcomes, including oscillatory and non-oscillatory tissue dynamics. The second case study involves the diffusion and reaction of an activator–inhibitor system in the context of Turing patterns on a non-uniformly evolving cellular domain [26–28]. In both case studies, the numerical solution of the continuum model provides an accurate description of the underlying discrete mechanisms.

2. Model description

In this section, we first describe the cell-based model, referred to as the discrete model, where mechanical cellular properties are coupled with intracellular signalling. To provide mathematical insight into the discrete model, we then derive the corresponding coarse-grained approximation, which is referred to as the continuum model.

(a). Discrete model

To represent a one-dimensional cross section of epithelial tissue, a one-dimensional chain of cells is considered [8,9] (figure 1). The tissue length, L(t), evolves in time, while the number of cells, N, remains fixed. We define xi(t), i = 0, 1, …, N, to represent the cell boundaries, such that the left boundary of cell i is xi−1(t) and the right boundary of cell i is xi(t). Epithelial tissues often evolve in confined spaces [39]. Therefore, we fix the left tissue boundary at x0(t) = 0, while the right tissue boundary is a free boundary, xN(t) = L(t).

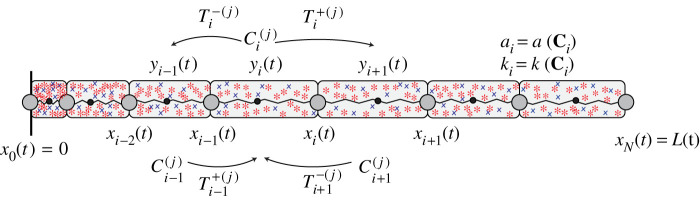

Figure 1.

Schematic of the discrete model where mechanical cell properties, ai and ki, are functions of the family of chemical signals, Ci(t). In this schematic, we consider two diffusing chemical species where the concentration in the ith cell is . The diffusive flux into cell i from cells i ± 1, and the diffusive flux out of cell i into cells i ± 1, is shown. Cell i, with boundaries at xi−1(t) and xi(t), is associated with a resident point, yi(t), which determines the diffusive transport rates, . (Online version in colour.)

Each cell, which we consider to be a mechanical spring [8,9], is assigned potentially distinct mechanical properties, ai and ki, such that the resulting tissue is heterogeneous (figure 1) [7]. Each cell i contains a family of well-mixed chemical species, , where represents the concentration of the jth chemical species in cell i at time t. As the cell boundaries evolve with time, tends to decrease as cell i expands. Conversely, tends to increase as cell i compresses. Furthermore, diffuses from cell i to cells i ± 1. The mechanical properties of individual cells, such as the cell resting length, ai = a (Ci), and the cell stiffness, ki = k(Ci), may depend on the local chemical concentration, Ci(t). We refer to this as mechanobiological coupling. The mechanobiological coupling is assumed to be instantaneous as ai and ki are functions of the current concentration, Ci(t).

The motion of each internal cell boundary is governed by Newton’s second law of motion,

| 2.1 |

where mi is the mass associated with cell boundary i, is the viscous force associated with cell boundary i, and fi is the cell-to-cell interaction force acting on cell boundary i from the left [5–8]. For simplicity, we choose a linear, Hookean force law given by

| 2.2 |

The viscous force is generated by cell–matrix interactions, and is modelled as , where η > 0 is the mobility coefficient [5–8]. As cells move in dissipative environments, the motion of each cell i is assumed to be overdamped, such that the left-hand side of equation (2.1) is zero [6,7,40]. Hence, the location of each cell boundary i evolves as

| 2.3 |

The fixed boundary at x0(t) = 0 has zero velocity, whereas the free boundary at xN(t) = L(t) moves solely due to the force acting from the left:

| 2.4 |

We now formulate a system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) that describe the rate of change of due to changes in cell length and diffusive transport. A position-jump process is used to describe the diffusive transport of . We use to denote the rate of diffusive transport of from cell i to cells i ± 1, respectively [41,42] (figure 1). For a standard unbiased position-jump process with a uniform spatial discretization, linear diffusion at the macroscopic scale is obtained by choosing constant [41]. As the cell boundaries evolve with time, one way to interpret is that it represents a time-dependent, non-uniform spatial discretization of the concentration profile over the chain of cells. Therefore, care must be taken to specify on the temporally evolving spatial discretization if we suppose the position-jump process corresponds to linear diffusion at the macroscopic level [42].

Yates et al. [42] show that in order for the position-jump process to lead to linear diffusion at the macroscopic level, the length- and time-dependent transport rates must be chosen as

| 2.5 |

and

| 2.6 |

where Dj > 0 is the diffusion coefficient of the jth chemical species at the macroscopic level, and yi(t) is the resident point associated with cell i (figure 1) [42]. The resident points are a Voronoi partition such that the left jump length for the transport of is yi(t) − yi−1(t), and the right jump length for the transport of is yi+1(t) − yi(t) [42]. Complete details of defining a Voronoi partition are outlined in the electronic supplementary material, S2ai.

At the tissue boundaries, we set so that the flux of and across x0(t) = 0 and xN(t) = L(t) is zero. We follow Yates et al. [42] and choose the inward jump length for the transport of and as 2(y1(t) − x0(t)) and 2(xN(t) − yN(t)), respectively, giving

| 2.7 |

and

| 2.8 |

Therefore, the ODEs which describe the evolution of are:

| 2.9 |

| 2.10 |

| 2.11 |

where li = xi(t) − xi−1(t) is the length of cell i. Chemical reactions among the chemical species residing in the ith cell are described by Z(j)(Ci). The form of Z(j)(Ci) is chosen to correspond to different signalling pathways.

In summary, the discrete model is given by equations (2.3)–(2.10), where equations (2.3) and (2.4) describe the mechanical interaction of cells, and equations (2.9)–(2.10) describe the underlying biological mechanisms. We solve this deterministic system of ODEs numerically using ode15s in MATLAB [43]. The numerical method is outlined in the electronic supplementary material, S2a, and key numerical algorithms to solve the discrete model are available on GitHub.

(b). Continuum model

Assuming that the tissue consists of a sufficiently large number of cells, N, we now derive an approximate continuum limit description of the discrete model. In the discrete model, i = 0, 1, …, N is a discrete variable which indexes cell positions and cell properties. The time evolution of the cell boundaries, xi(t), is a set of N + 1 discrete functions that depend continuously upon time. By contrast, the continuum model describes the spatially continuous evolution of cell boundary trajectories in terms of the cell density per unit length, q(x, t). In the continuum model, is the continuous analogue of i [5]. As N → ∞, becomes a continuous variable and defines a continuum of cells. The spatially and temporally continuous cell density is [5,8]

| 2.12 |

At any time t, is the inverse function of where x ∈ [0, L(t)] for . We use to represent the continuous spatial and temporal evolution of cell boundary trajectories [5].

The discrete quantity Ci(t) is represented by a multicomponent vector field in the continuum model, . We assume that the mechanical relaxation of cells is sufficiently fast such that the spatial distribution of cell lengths is slowly varying in space [6]. That is, when k is sufficiently large, the cells mechanically relax relatively quickly such that each cell in the tissue is approximately the same length. Under this assumption, the location of the resident points can be approximated as the midpoint of each cell,

| 2.13 |

This assumption is further discussed in the electronic supplementary material, S3. In equation (2.12), the subscript j denotes the jth chemical species in the continuum model, and the superscript (j) denotes the jth chemical species in the discrete analogue. Mechanobiological coupling is introduced by allowing the cell stiffness, , and the cell resting length, , to depend on the local chemical concentration.

We write the linear force law for the continuum of cells as

| 2.14 |

where is evaluated at . Thus, the equations of motion are:

| 2.15 |

| 2.16 |

| 2.17 |

The definition of in equation (2.13) contains arguments evaluated at , and . Substituting equation (2.13) into equations (2.14)–(2.16), and expanding all terms in a Taylor series about gives

| 2.18 |

| 2.19 |

| 2.20 |

To describe the continuous evolution of cell trajectories and cell properties, we write [6,7], and define the continuous linear force law corresponding to equation (2.13) as a one-dimensional stress field

| 2.21 |

We express equations (2.17)–(2.19) in terms of q(x, t) and f(x, t) through a change of variables from to (x, t) [5,8]. The change of variables gives

| 2.22 |

and

| 2.23 |

Complete details of the change of variables calculation are outlined in the electronic supplementary material, S1a.

The local cell velocity, u(x, t) = ∂x/∂t, is derived by substituting equations (2.21)–(2.22) into the right-hand side of equation (2.18). Factorizing in terms of f(x, t) gives

| 2.24 |

As u(x, t) = ∂x/∂t, we substitute equation (2.21) into the left-hand side of equation (2.23) to derive the governing equation for cell density. The resulting equation is differentiated with respect to x to give

| 2.25 |

The order of differentiation on the left-hand side of equation (2.24) is reversed, and equation (2.21) is used [5,8] to give

| 2.26 |

The boundary condition for the evolution of L(t) is obtained by substituting equations (2.21) and (2.22) into the right-hand side of equation (2.19), giving

| 2.27 |

As u(x, t) = ∂x/∂t, the left-hand side of equation (2.26) is equated to equation (2.23). Factorizing in terms of f(x, t) gives the free boundary condition

| 2.28 |

A similar transformation is applied to equation (2.17) to yield the left boundary condition as

| 2.29 |

Equations (2.23), (2.25), (2.27) and (2.28) form a continuum limit approximation of the discrete model. Equations (2.23), (2.25) and (2.28) were reported previously by Murphy et al. [6], who consider heterogeneous tissues of fixed length without mechanobiological coupling. A key contribution here is the derivation of equation (2.27), which describes how the free boundary evolves due to the underlying biological mechanisms and heterogeneity included in the discrete model. For a homogeneous tissue where the cell stiffness and cell resting length are constant and independent of , equation (2.22) is equivalent to equation (23) in Baker et al. [5]. The electronic supplementary material, S1b, shows that equations (2.23), (2.25) and (2.28) can be derived without expanding all components of equations (2.14) and (2.15). As the definition of in equation (2.13) contains arguments evaluated at , and , it is necessary to expand all components of equation (2.16) about to derive equation (2.27). For consistency, equations (2.23), (2.25) and (2.28) are derived in the same way.

We now consider a reaction–diffusion equation for the evolution of . The reaction–diffusion equation involves terms associated with the material derivative, diffusive transport, and source terms that reflect chemical reactions as well as the effects of changes in cell length

| 2.30 |

The material derivative arises from differentiating equation (2.12) with respect to time, and describes the propagation of cell properties along cell boundary characteristics [6,7]. The term describing the effects of changes in cell length arises directly from the discrete mechanisms described in equations (2.9)–(2.10). The linear diffusion term arises due to the choice of jump rates in equations (2.5)–(2.8) of the discrete model [42]. Chemical reactions are described by , and originate from equivalent terms in the discrete model, Z(j)(Ci).

Boundary conditions for are chosen to ensure mass is conserved at x = 0 and x = L(t). As the left tissue boundary is fixed, we set at x = 0. At x = L(t), we enforce that the total flux of in the frame of reference co-moving with the right tissue boundary is zero for all time

| 2.31 |

where u(L(t), t) = dL/dt. Thus, at x = L(t). Writing equation (2.29) in conservative form gives

| 2.32 |

| 2.33 |

| 2.34 |

| 2.35 |

| 2.36 |

where

| 2.37 |

and at x = 0 and x = L(t).

Equations (2.31)–(2.35) are solved numerically using a boundary fixing transformation [44]. In doing so, equations (2.31)–(2.35) are transformed from an evolving domain, x ∈ [0, L(t)], to a fixed domain, ξ ∈ [0, 1], by setting ξ = x/L(t) [44]. The transformed equations are discretized using a standard implicit finite difference method with initial conditions q(x, 0) and . The numerical method is outlined in the electronic supplementary material, S5a, and key numerical algorithms to solve the continuum model are available on GitHub.

3. Results

To examine the accuracy of the new free boundary model, we compare solutions from the discrete and continuum models for epithelial tissues consisting of m = 1 and m = 2 chemical species.

(a). Preliminary results: homogeneous tissue

In all simulations, an epithelial tissue with just N = 20 cells is considered. Fig. 2 in Baker et al. [5] shows that the accuracy of the continuum model increases with N. We present similar results in the electronic supplementary material, S3, for N > 20, to confirm this. Thus, choosing a relatively small value of N is a challenging scenario for the continuum model. In the discrete model, each cell i is initially the same length, li(0) = 0.5, such that L(0) = 10. The discrete cell density is qi(t) = 1/li(t), which corresponds to q(x, 0) = 2 for x ∈ [0, L(t)] in the continuum model.

The simplest application of the free boundary model is to consider cell populations without mechanobiological coupling. For a homogeneous tissue with one chemical species , the cell stiffness and cell resting length are constant and independent of . Thus, the governing equations for q(x, t) and are only coupled through the cell velocity, u(x, t). To investigate how non-uniform tissue evolution affects the chemical concentration of cells, we set for x ∈ [0, L(t)] and .

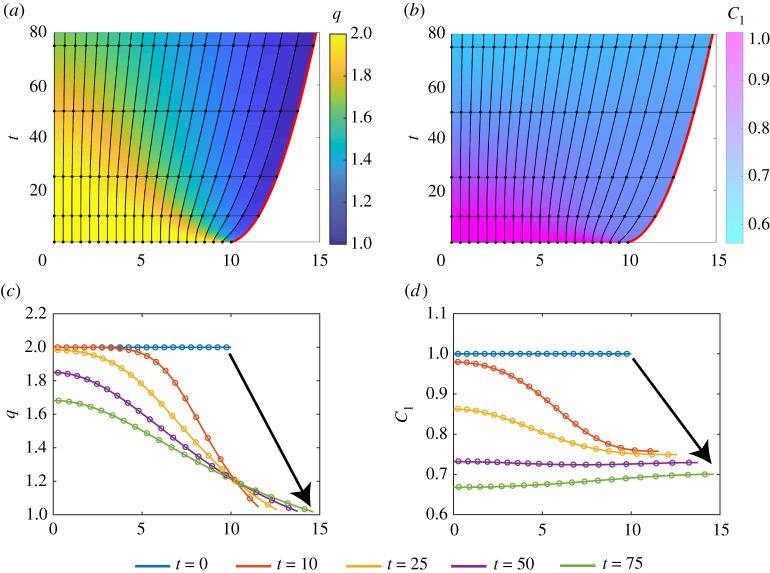

Figure 2a demonstrates a rapid decrease in the cell density at x = L(t) as the tissue relaxes and the cells elongate. This decreases the chemical concentration (figure 2b). As the tissue mechanically relaxes, the cell boundaries form a non-uniform spatial discretization on which is transported (figure 2a,b). Figure 2c,d demonstrates that the continuum model accurately reflects the biological mechanisms included in the discrete model, despite the use of truncated Taylor series expansions. Additional results in the electronic supplementary material, S4, show that and L(t) become constant as t → ∞.

Figure 2.

Homogeneous tissue with N = 20 cells and one chemical species where , and a = k = D1 = η = 1. Characteristicdiagrams in (a,b) illustrate the position of cell boundaries where the free boundary is highlighted in red. The colour in (a,b) represents q(x, t) and , respectively. In (a,b), the black horizontal lines indicate times at which q(x, t) and snapshots are shown in (c,d). In (c,d), the discrete and continuum solutions are compared as the dots and solid line, respectively, for t = 0, 10, 25, 50, 75 where the arrow represents the direction of time. (Online version in colour.)

(b). Case study 1: Rac–Rho pathway

We now apply the mechanobiological model to investigate the Rac–Rho pathway. Rho GTPases are a family of signalling molecules that consist of two key members: RhoA and Rac1. Rho GTPases cycle between an active and inactive state, and regulate cell size and cell motility [12,35,37,45,46]. Additionally, Rho GTPases play roles in wound healing [47] and cancer development [48,49]. New experimental methods [50,51] have discovered a connection between cellular mechanical tension and Rho GTPase activity [52]. Previous studies focus on using a discrete modelling framework to investigate this relationship, and conclude that epithelial tissue dynamics is dictated by the strength of the mechanobiological coupling [12,33]. Experimental evidence suggests that some GTPases can move between cells [53]. We extend previous mathematical models which consider mechanobiological coupling [12,33] by incorporating diffusive chemical transport and chemical variation associated with changes in cell length.

To investigate the impact of mechanobiological coupling on epithelial tissue dynamics, we let such that is the concentration of RhoA and is the concentration of Rac1. In the discrete and continuum models, cells are assumed to behave like linear springs [8,9]. Thus, cellular mechanical tension is defined as the difference between the length and resting length of cells. Mechanobiological coupling is proportional to cellular tension, and is included in . As Rho GTPase activity increases cell stiffness [54], we choose as an increasing function of either or . Furthermore, is chosen to reflect the fact that RhoA promotes cell contraction [12,33]. We first set D1 = D2 = 1, and then vary the diffusivity to explore how this affects the tissue-level dynamics.

The effect of RhoA is considered first, where . We include the same mechanobiological coupling as [12,33] and let

| 3.1 |

where b is the basal activation rate, GT is the total amount of active RhoA and δ is the deactivation rate [12,33]. The activation term describes a positive feedback loop, governed by γ, to reflect the fact that RhoA self-activates [12,33]. Mechanobiological coupling, governed by β, is proportional to mechanical tension.

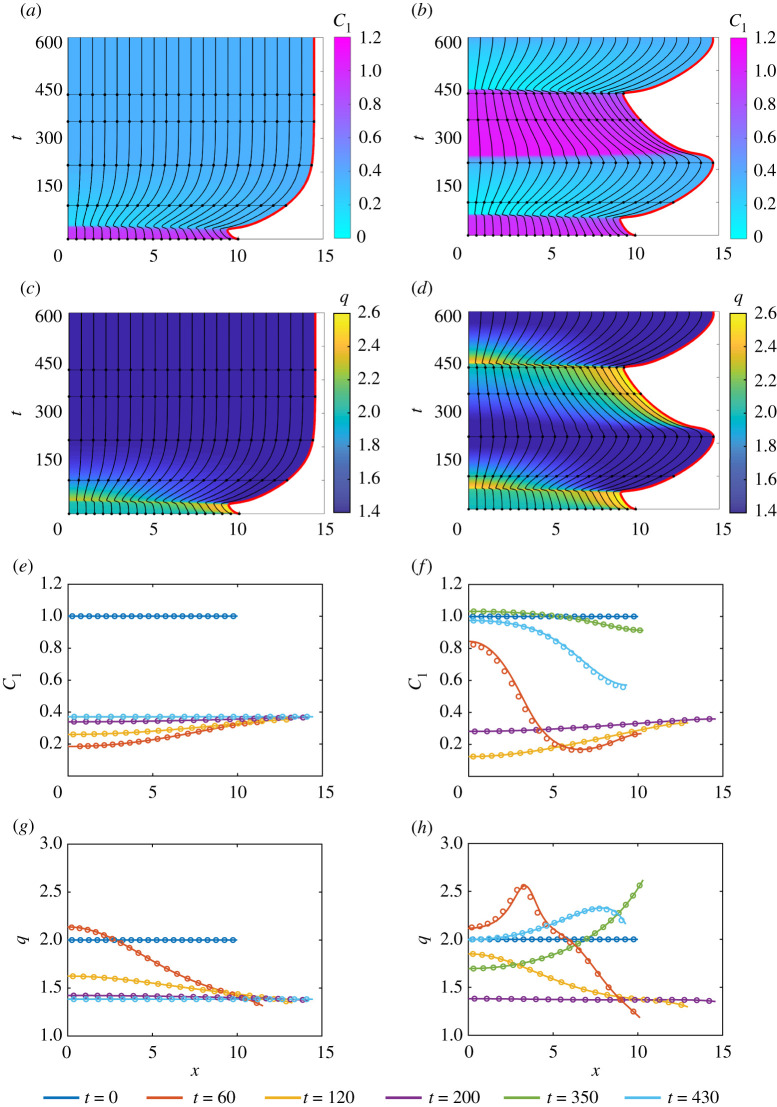

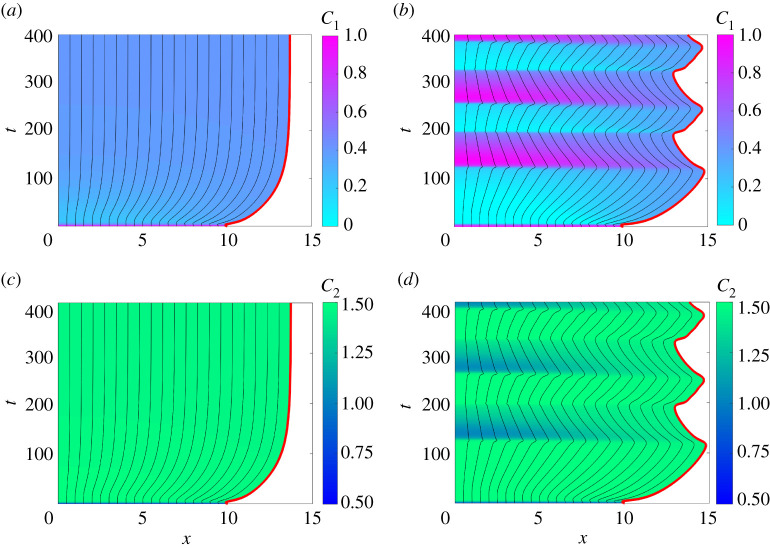

Similar to [12], we find that the tissue either mechanically relaxes or continuously oscillates depending on the choice of β (figure 3). Figure 3a,c illustrates non-oscillatory tissues for weak mechanobiological coupling, β = 0.2, whereas increasing the strength of the mechanobiological,β = 0.3, leads to temporal oscillations in the tissue length and sharp transitions between high and low levels of RhoA (figure 3b,d). Figure 3e–h illustrates that the continuum model accurately describes non-oscillatory and oscillatory tissue dynamics.

Figure 3.

One-dimensional tissue dynamics where RhoA is coupled to mechanical cell tension. (a,c,e,g) correspond to β = 0.2 and (b,d,f ,h) relate to β = 0.3. Characteristic diagrams in (a–d) illustrate the evolution of cell boundaries where the free boundary is highlighted inred. The colour in (a,b) represents and q(x, t) in (c,d). The black horizontal lines indicate times at which and q(x, t) snapshots are shown in (e,f ) and (g,h), respectively. In (e–h), the discrete and continuum solutions are compared as the dots and solid line, respectively, for t = 0, 100, 220, 350, 430. In both systems, , , D1 = 1, η = 1 and for x ∈ [0, L(t)]. Parameters: b = 0.2, γ = 1.5, n = 4, p = 4, GT = 2, l0 = 1, ϕ = 0.65, Gh = 0.4, δ = 1. (Online version in colour.)

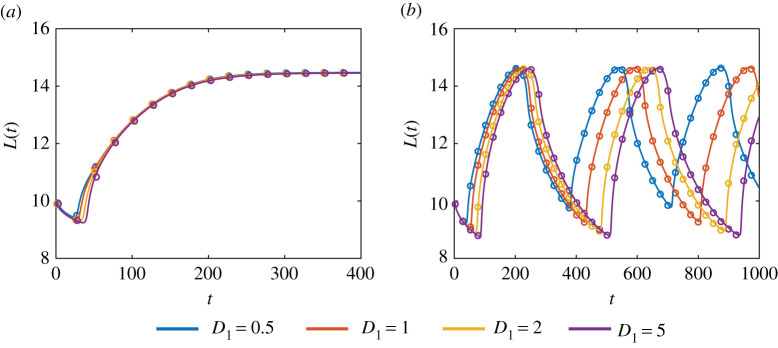

Diffusion is often considered to be stabilizing [55] so we hypothesize that increasing D1 could smooth the tissue oscillations. Surprisingly, figure 4 shows that as D1 increases we observe a phase shift but no change in the amplitude of oscillations. This test case provides further evidence of the ability of the new continuum model to accurately capture key biological mechanisms included in the discrete model, even when D1 is relatively small (figure 4). As with any numerical solution of a reaction–diffusion equation, a finer computational mesh is required to solve the continuum model when the diffusivity is small [56], meaning that the continuum model becomes computationally expensive as the diffusivity decreases. Under these conditions, we prefer to use the discrete model.

Figure 4.

The effect of diffusion on the dynamics of the free boundary for (a) a non-oscillatory system with β = 0.2 and (b) a oscillatory system with β = 0.3. The discrete solution is shown as the dots and the continuum solution as a solid line. Parameters are as in figure 3. (Online version in colour.)

To examine the combined effect of RhoA and Rac1 on epithelial tissue dynamics, we let and consider [12],

| 3.2 |

and

| 3.3 |

where is the concentration of RhoA and is the concentration of Rac1. In a weakly coupled system when , we observe the fast transition from the initial concentrations of RhoA and Rac1 to the steady state concentration (figure 5a,c). Analogous to figure 3a,c, temporal oscillations arise when the mechanobiological coupling is strong, (figure 5b,d).

Figure 5.

Characteristic diagrams for the interaction of RhoA and Rac1 where the free boundary is highlighted in red. Panels (a,c) correspond to a non-oscillatory system, where and (b,d)relate to an oscillatory system where . The colour in (a,b) denotes the concentration of RhoA and the concentration of Rac1 in (c,d). In both systems, , , D1 = D2 = 1 and η = 1. The initial conditions are and for x ∈ [0, L(t)]. Parameters: b1 = b2 = 1, δ1 = δ2 = 1, n = 3, p = 4, , , l0 = 1, ϕ = 0.65, Gh = 0.4. Discrete and continuum solutions are compared in the electronic supplementary material, S5. (Online version in colour.)

The mechanobiological coupling and intracellular signalling in figures 3–5 extend upon previous Rho GTPase models [12,33]. We note that the source terms in equations (3.1)–(3.3) can be applied to a single, spatially uniform cell to explore how the stability of the equilibria depend on model parameters [12]. This analysis, outlined in the electronic supplementary material, S5a, was used to inform our choices of β and .

(c). Case study 2: activator–inhibitor patterning

Case study 2 considers an activator–inhibitor system [55,57,58]. Previous studies of activator–inhibitor patterns on uniformly growing domains have characterized the pattern splitting and frequency doubling phenomena which occur naturally on the skin of angelfish [25–28,59]. To investigate how diffusion-driven instabilities arise on a non-uniformly evolving domain, we let with D1 ≠ D2, and use Schnakenberg kinetics

| 3.4 |

and

| 3.5 |

where is the activator and is the inhibitor [55]. The parameters, ni > 0 for i = 1, 2, 3, 4, govern activator–inhibitor interactions. Non-dimensionalization of equations (2.25) and (2.29) reveals that the linear stability analysis is analogous to the classical stability analysis of Turing patterns on fixed domains [55]. Thus, we define the relative diffusivity, d = D2/D1, with the expectation that there exists a critical value, dc, that depends upon the choice of ni, such that diffusion-driven instabilities arise for d > dc [55,57]. The linear stability analysis and computation of dc is outlined in the electronic supplementary material, S6a.

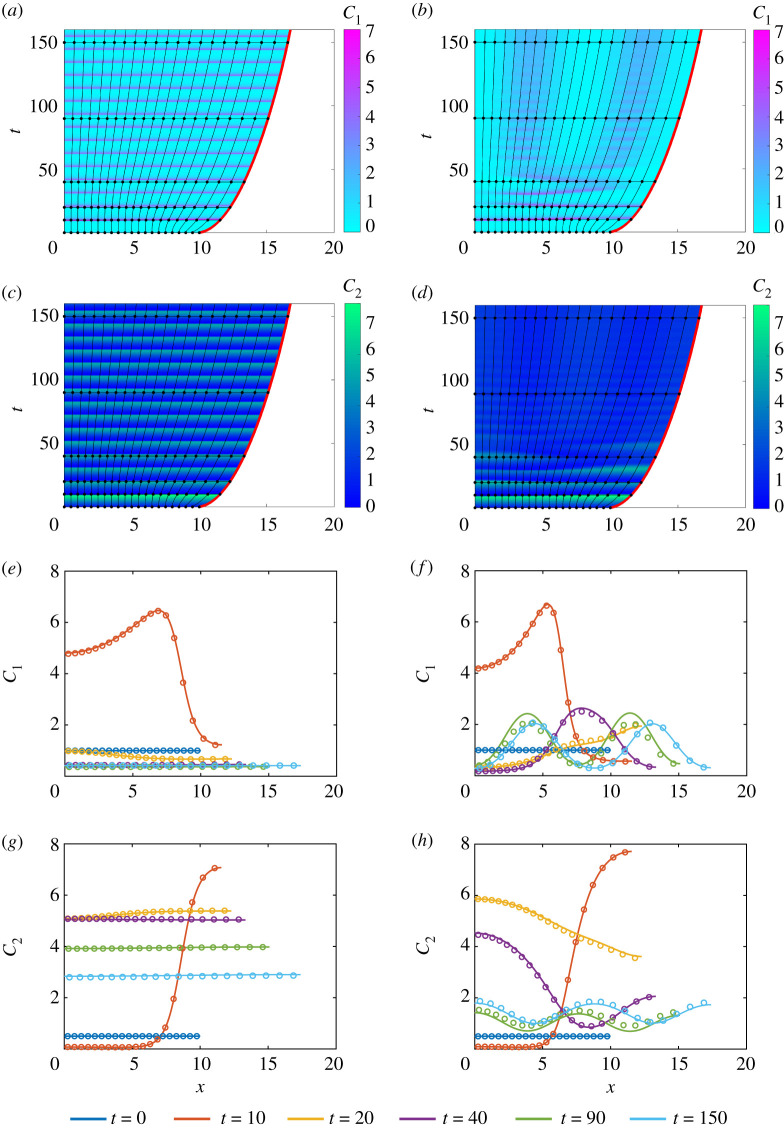

A homogeneous tissue is initialized to investigate the effect of d on the evolution of activator–inhibitor patterns. As the mechanical cell properties are chosen to be constant and independent of , the governing equations for q(x, t), and are only coupled through the cell velocity, u(x, t). Thus, the tissue evolves non-uniformly as a result of this coupling. For d < dc, the distribution of and varies in time but remains approximately spatially uniform throughout the tissue (figure 6a,c,e,g). Thus, only temporal patterning arises when d < dc. Figure 6b,d,f ,h demonstrates that spatial–temporal patterns develop when d > dc. Similar to [25–27], we observe splitting in activator peaks for d > dc where the concentration of is at a minimum. Figure 6b shows that two distinct activator peaks arise. The long time behaviour of the tissue is examined in the electronic supplementary material, S6. Figure 6e,g shows excellent agreement between the solutions of the discrete and continuum models when d < dc, whereas figure 6f ,h shows a small discrepancy between the solutions of the discrete and continuum models when d > dc.

Figure 6.

Activator–inhibitor patterns in a homogeneous tissue. In (a,c,e,g), D1 = 2 and D2 = 3 with d < dc. In (b,d,f ,h), D1 = 0.5 and D2 = 5 with d > dc. (a)–(d) shows the cellboundaries where the free boundary is highlighted in red. The colour in (a,b) represents and in (c,d). The black horizontal lines indicate times at which and snapshots are shown in (e,f ) and (g,h), respectively. In (e–h), the discrete (dots) and continuum (solid line) solutions are compared at t = 0, 10, 20, 40, 90, 150. In both systems, and for x ∈ [0, L(t)] and a = k = η = 1. Parameters: n1 = 0.1, n2 = 1, n3 = 0.5, n4 = 1 and dc = 4.9842. (Online version in colour.)

As the mechanical relaxation in figure 6f ,h is relatively fast, k = 1, the small discrepancy between the solutions of the discrete and continuum models decreases as the tissue mechanically relaxes. Additional results in figure 7 confirm that when the mechanical relaxation is slower, k = 0.5, the discrepancy between solutions of the discrete and continuum models is more pronounced, as expected. Thus, the continuum model accurately describes tissue-level behaviour when the mechanical relaxation of cells is sufficiently fast. In cases where the mechanical relaxation is slow, we advise use of the discrete model.

Figure 7.

The evolution of spatial–temporal patterns in a homogeneous tissue with Schnakenberg dynamics, where d > dc and k = 0.5. Characteristic diagrams in (a,b) illustrate the evolution of cell boundaries where the free boundary is highlighted in red. The colour in (a) represents and in (b). The black horizontal lines indicate times at which and snapshots are shown in (c) and (d), respectively. In (c,d), the discrete and continuum solutions are compared as the dots and solid line, respectively, for t = 0, 10, 20, 40, 90, 200. The initial conditions are and for x ∈ [0, L(t)], with a = η = 1, D1 = 0.5 and D2 = 5. Parameters: n1 = 0.1, n2 = 1, n3 = 0.5, n4 = 1 and dc = 4.9842. (Online version in colour.)

4. Conclusion

In this study, we present a novel free boundary mechanobiological model to describe epithelial tissue dynamics. A discrete modelling framework is used to include mechanobiological coupling at the cell level. Tissue-level outcomes are described by a system of coupled, nonlinear partial differential equations, where the evolution of the free boundary is governed by a novel boundary condition. The evolution of the free boundary is an emergent property rather than being pre-specified to match experimental observations [22–28]. By constructing the continuum limit of the biologically motivated discrete model, we arrive at a novel free boundary condition which describes how mechanobiological coupling dictates epithelial tissue dynamics. In deriving the continuum model, we make reasonable assumptions that N is sufficiently large, and that the time scale of mechanical relaxation is sufficiently fast [7]. Case studies involving a homogeneous cell population, the Rac–Rho pathway and activator–inhibitor patterning demonstrate that the continuum model reflects the biologically motivated discrete model even when N is relatively small. These case studies show how non-uniform tissue dynamics, including oscillatory and non-oscillatory tissue behaviour, arises due to mechanobiological coupling.

There are many potential avenues to generalize and extend the modelling framework presented in this study. We take the most fundamental approach and use a linear force law to describe mechanical relaxation. One avenue for extension would be to explore nonlinear force laws [5,9]. Another choice we make is to suppose that chemical transport is described by linear diffusion, whereas other choices, such as drift-diffusion, are also possible [60]. We also implement the most straightforward assumption that the mechanobiological coupling is instantaneous, and a further extension would be to include delays in the mechanobiological coupling. Incorporating delays could be useful to represent chemical processes which occur on different time scales to the mechanical relaxation [14,61]. We always consider the case where the evolution of the free boundary is driven by mechanical relaxation. However, it is also possible to consider a more general scenario where the evolution of the position of cell boundaries explicitly depends on the local chemical concentration [11,26]. Further extensions of the free boundary model would be to introduce cell proliferation and cell death [5,7,62]. These extensions are relatively straightforward to incorporate into the discrete model, and the tissue-level dynamics could be analysed by constructing a new continuum model [5,7].

The free boundary model presented in this study is tractable because we consider a one-dimensional cross section of epithelial tissue. This simplification is relevant when we consider slender tissues [63]. A significant extension of our work would be to consider a full two-dimensional discrete model by representing cells as polygons [11,15,29]. To derive a two-dimensional continuum model, we would need to invoke several simplifying assumptions about the cell-to-cell interactions and connectivity [1,64]. A two-dimensional free boundary continuum model would require more sophisticated numerical methods to solve as the boundary-fixing transformation used in this study would no longer be appropriate. Therefore, we leave the question of developing a two-dimensional model for future consideration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the computational resources provided by the High Performance Computing and Research Support Group. We thank the two anonymous referees for their helpful comments.

Data accessibility

This article does not contain any additional data. MATLAB implementations of key numerical algorithms are available on GitHub.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the design of the study. T.A.T. performed numerical simulations with the assistance of R.J.M. T.A.T. drafted the article and all authors gave approval for publication.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This work is supported by the Australian Research Council(grant nos. DP200100177 and DP180101797).

Reference

- 1.Fozard JA, Byrne HM, Jensen OE, King JR. 2010. Continuum approximations of individual-based models for epithelial monolayers. Math. Med. Biol. 27, 39–74. ( 10.1093/imammb/dqp015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guillot C, Lecuit T. 2013. Mechanics of epithelial tissue homeostasis and morphogenesis. Science 340, 1185–1189. ( 10.1126/science.1235249) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu GK, Liu Y, Li B. 2015. How do changes at the cell level affect the mechanical properties of epithelial monolayers? Soft Matter 11, 8782–8788. ( 10.1039/c5sm01966d) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dasbiswas K, Hannezo E, Gov NS. 2018. Theory of epithelial cell shape transitions induced by mechanoactive chemical gradients. Biophys. J. 114, 968–977. ( 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.12.022) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker RE, Parker A, Simpson MJ. 2019. A free boundary model of epithelial dynamics. J. Theor. Biol. 481, 61–74. ( 10.1016/j.jtbi.2018.12.025) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy RJ, Buenzli PR, Baker RE, Simpson MJ. 2019. An individual–based mechanical model of cell movement in heterogeneous tissues and its coarse–grained approximation. Proc. R. Soc. A 475, 20180838 ( 10.1098/rspa.2018.0838) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy RJ, Buenzli PR, Baker RE, Simpson MJ. 2020. Mechanical cell competition in heterogeneous epithelial tissues. Bull. Math. Biol. 82, 130 ( 10.1007/s11538-020-00807-x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murray PJ, Edwards CM, Tindall MJ, Maini PK. 2009. From a discrete to a continuum model of cell dynamics in one dimension. Phys. Rev. E 80, 031912 ( 10.1103/PhysRevE.80.031912) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murray PJ, Edwards CM, Tindall MJ, Maini PK. 2012. Classifying general non-linear force laws in cell–based models via the continuum limit. Phys. Rev. E 85, 021921 ( 10.1103/PhysRevE.85.021921) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lorenzi T, Murray PJ, Ptashnyk M. 2019 From individual–based mechanical models of multicellular systems to free–boundary problems. Preprint on. (http://arxiv.org/abs/1903.06590. )

- 11.Smith AM, Baker RE, Kay D, Maini PK. 2011. Incorporating chemical signalling factors into cell–based models of growing epithelial tissues. J. Math. Biol. 65, 441–463. ( 10.1007/s00285-011-0464-y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zmurchok C, Bhaskar D, Edelstein-Keshet L. 2018. Coupling mechanical tension and GTPase signalling to generate cell and tissue dynamics. Phys. Biol. 15, 046004 ( 10.1088/1478-3975/aab1c0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zmurchok C, Collette J, Rajagopal V, Holmes WR. 2020. Membrane tension can enhance adaptation to maintain polarity of migrating cells. Biophysical J. 119, 1617–1629. ( 10.1016/j.bpj.2020.08.035) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boocock D, Hino N, Ruzickova N, Hirashima T, Hannezo E. 2020. Theory of mechano–chemical patterning and optimal migration in cell monolayers. Nat Phys. ( 10.1038/s41567-020-01037-7) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osborne JM, Fletcher AG, Pitt-Francis JM, Maini PK, Gavaghan DJ. 2017. Comparing individual–based approaches to modelling the self–organization of multicellular tissues. PLoS Comput. Biol. 13, e1005387 ( 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005387) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans ND, Oreffo RO, Healy E, Thurner PJ, Man YH. 2013. Epithelial mechanobiology, skin wound healing, and the stem cell niche. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 28, 397–409. ( 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2013.04.023) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fletcher AG, Cooper F, Baker RE. 2017. Mechanocellular models of epithelial morphogenesis. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 372, 20150519 ( 10.1098/rstb.2015.0519) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedman A. 2015. Free boundary problems in biology. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 373, 20140368 ( 10.1098/rsta.2014.0368) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Serra-Picamal X, Conte V, Vincent R, Anon E, Tambe DT, Bazellieres E, Butler JP, Fredberg JJ, Trepat X. 2012. Mechanical waves during tissue expansion. Nat. Phys. 8, 628–634. ( 10.1038/NPHYS2355) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Hachem M, McCue SW, Wang J, Yihong D, Simpson MJ. 2019. Revisiting the Fisher–Kolmogorov–Petrovsky–Piskunov equation to interpret the spreading–extinction dichotomy. Proc. R. Soc. A 475, 20190378 ( 10.1098/rspa.2019.0378) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Du Y, Lin Z. 2010. Spreading-vanishing dichotomy in the diffusive logistic model with a free boundary. SIAM J. Math. Anal. 42, 377–405. ( 10.1137/090771089) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simpson MJ, Landman KA, Newgreen DF. 2006. Chemotactic and diffusive migration on a nonuniformly growing domain: numerical algorithm development and applications. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 192, 282–300. ( 10.1016/j.cam.2005.05.003) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simpson MJ, Sharp JA, Baker RE. 2015. Survival probability for a diffusive process on a growing domain. Phys. Rev. E 91, 042701 ( 10.1103/PhysRevE.91.042701) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simpson MJ, Baker RE. 2015. Exact calculations of survival probability for diffusion on growing lines, disks, and spheres: the role of dimension. J. Chem. Phys. 143, 094109 ( 10.1063/1.4929993) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maini PK, Woolley TE, Baker RE, Gaffney EA, Lee SS. 2012. Turing’s model for biological pattern formation and the robustness problem. Interface Focus 2, 487–496. ( 10.1098/rsfs.2011.0113) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crampin EJ, Hackborn WW, Maini PK. 2002. Pattern formation in reaction–diffusion models with non-uniform domain growth. Bull. Math. Biol. 64, 747–769. ( 10.1006/bulm.2002.0295) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crampin EJ, Gaffney EA, Maini PK. 1999. Reaction and diffusion on growing domains: scenarios for robust pattern formation. Bull. Math. Biol. 61, 1093–1120. ( 10.1006/bulm.1999.0131) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crampin EJ, Gaffney EA, Maini PK. 2002. Mode–doubling and tripling in reaction–diffusion patterns on growing domains: a piecewise linear model. J. Math. Biol. 44, 107–128. ( 10.1007/s002850100112) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pathmanathan P, Cooper J, Fletcher AG, Mirams G, Murray PJ, Osborne JM, Pitt-Francis J, Walter A, Chapman SJ. 2009. A computational study of discrete mechanical tissue models. Phys. Biol. 6, 036001 ( 10.1088/1478-3975/6/3/036001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Armstrong NJ, Painter KJ, Sherratt JA. 2006. A continuum approach to modelling cell–cell adhesion. J. Theor. Biol. 243, 98–113. ( 10.1016/j.jtbi.2006.05.030) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murphy RJ, Buenzli PR, Baker RE, Simpson MJ. 2021. Travelling waves in a free boundary mechanobiological model of an epithelial tissue. Appl. Math. Lett. 111, 106636 ( 10.1016/j.aml.2020.106636) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dalwadi MP, Waters SL, Byrne HM, Hewitt IJ. 2020. A mathematical framework for developing freezing protocols in the cryopreservation of cells. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 80, 657–689. ( 10.1137/19M1275875) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bui J, Conway DE, Heise RL, Weinberg SH. 2019. Mechanochemical coupling and junctional forces during collective cell migration. Biophys. J. 117, 170–183. ( 10.1016/j.bpj.2019.05.020) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holmes WR, Park J, Levchenko A, Edelstein-Keshet L. 2017. A mathematical model coupling polarity signalling to cell adhesion explains diverse cell migration patterns. PLoS Comput. Biol. 13, e1005524 ( 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005524) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Byrne KM. et al. 2016. Bistability in the Rac1, PAK, and RhoA signalling network drives actin cytoskeleton dynamics and cell motility switches. Cell Syst. 2, 38–48. ( 10.1016/j.cels.2016.01.003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ridley AJ. 2001. Rho family proteins: coordinating cell responses. Trends Cell Biol. 11, 471–477. ( 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02153-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guilluy C. 2011. Rho protein crosstalk: another social network? Trends Cell Biol. 21, 718–726. ( 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.08.002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Samuel MS. et al. 2011. Actomyosin-mediated cellular tension drives increased tissue stiffness and β-catenin activation to induce epidermal hyperplasia and tumour growth. Cancer Cell 19, 776–791. ( 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.05.008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mohammed D. et al. 2019. Substrate area confinement is a key determinant of cell velocity in collective migration. Nat. Phys. 15, 858–866. ( 10.1038/s41567-019-0543-3) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matsiaka OM, Penington CJ, Baker RE, Simpson MJ. 2017. Continuum approximations for lattice–free multi–species models of collective cell migration. J. Theor. Biol. 422, 1–11. ( 10.1016/j.jtbi.2017.04.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Painter KJ, Sherratt JA. 2003. Modelling the movement of interacting cell populations. J. Theor. Biol. 225, 327–339. ( 10.1016/S0022-5193(03)00258-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yates CA, Baker RE, Erban R, Maini PK. 2012. Going from microscopic to macroscopic on non-uniform growing domains. Phys. Rev. E 86, 21921 ( 10.1103/PhysRevE.86.021921) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.MathWorks ode15s. Retrieved from https://au.mathworks.com/help/matlab/ref/ode15s.html in June 2020.

- 44.Simpson MJ. 2020. Critical length for the spreading–vanishing dichotomy in higher dimensions. ANZIAM J. 62, 3–17. ( 10.1017/S1446181120000103) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holmes WR, Edelstein-Keshet L. 2016. Analysis of a minimal Rho–GTPase circuit regulating cell shape. Phys. Biol. 13, 046001 ( 10.1088/1478-3975/13/4/046001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zmurchok C, Holmes WR. 2020. Simple Rho GTPase dynamics generate a complex regulatory landscape associated with cell shape. Biophys. J. 118, 1438–1454. ( 10.1016/j.bpj.2020.01.035) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abreu-Blanco MT, Verboon JM, Parkhurst SM. 2014. Coordination of Rho family GTPase activities to orchestrate cytoskeleton responses during cell wound repair. Curr. Biol. 24, 144–155. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2013.11.048) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Clayton NS, Ridley AJ. 2020. Targeting Rho GTPase signalling networks in cancer. Front. Cell and Dev. Biol. 8, 222 ( 10.3389/fcell.2020.00222) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haga RB, Ridley AJ. 2016. Rho GTPases: regulation and roles in cancer cell biology. Small GTPases 7, 207–221. ( 10.1080/21541248.2016.1232583) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sabass B, Gardel ML, Waterman CM, Schwarz US. 2008. High resolution traction force microscopy based on experimental and computational advances. Biophys. J. 94, 207–220. ( 10.1529/biophysj.107.113670) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pertz O, Hahn KM. 2004. Designing biosensors for Rho family proteins–deciphering the dynamics of Rho family GTPase activation in living cells. J. Cell Sci. 117, 1313–1318. ( 10.1242/jcs.01117) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Houk A, Jilkine A, Mejean C, Boltyanskiy R, Dufresne E, Angenent S, Altschuler S, Wu F, Weiner O. 2012. Membrane tension maintains cell polarity by confining signals to the leading edge during neutrophil migration. Cell 148, 175–188. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.050) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Khuperkar D, Helen M, Magre I, Joseph J. 2015. Inter-cellular transport of Ran GTPase. PLoS ONE 10, e0125506 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0125506) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sharma S, Santiskulvong C, Rao J, Gimzewski JK, Dorigo O. 2014. The role of Rho GTPase in cell stiffness and cisplatin resistance in ovarian cancer cells. Integr. Biol. 6, 611–617. ( 10.1039/c3ib40246k) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murray J. 2002. Mathematical biology II: spatial models and biomedical applications, 3rd edn New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang H, Anderson M. 1982. Introduction to groundwater modeling finite difference and finite element methods. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wentz JM, Mendenhall AR, Bortz DM. 2018. Pattern formation in the longevity–related expression of heat shock protein-16.2 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Bull. Math. Biol. 80, 2669–2697. ( 10.1007/s11538-018-0482-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Turing A. 1952. The chemical basis of morphogenesis. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 237, 37–72. ( 10.1098/rstb.1952.0012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kondo S, Asai R. 1995. A reaction–diffusion wave on the skin of the marine angelfish Pomacanthus. Nature 376, 765–768. ( 10.1038/376765a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Codling EA, Plank MJ, Benhamou S. 2008. Random walk models in biology. J. R. Soc. Interface 5, 813–834. ( 10.1098/rsif.2008.0014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Inoue T, Heo W, Grimley J, Wandless TJ, Meyer T. 2005. An inducible translocation strategy to rapidly activate and inhibit small GTPase signaling pathways. Nat. Methods 2, 415–418. ( 10.1038/nmeth763) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.El-Hachem M, McCue SW, Simpson MJ. 2020. A sharp–front moving boundary model for malignant invasion. Physica D 412, 132639 ( 10.1016/j.physd.2020.132639) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Simpson MJ, Landman KA, Hughes BD. 2009. Multi-species simple exclusion processes. Physica A 388, 399–406. ( 10.1016/j.physa.2008.10.038) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chapman LAC. 2015. Mathematical modelling of cell growth in tissue engineering bioreactors [Doctoral dissertation, University of Oxford]. Oxford University Research Archive. See https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:7c9ee131-7d9b-4e5d-8534-04a059fbd039.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This article does not contain any additional data. MATLAB implementations of key numerical algorithms are available on GitHub.