Abstract

Purpose of review:

Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD) is a neuromuscular disorder that is caused by incomplete repression of the transcription factor DUX4 in skeletal muscle. To date, there is no DUX4-targeting treatment to prevent or delay disease progression. In this review, we summarize developments in therapeutic strategies with the focus on inhibiting DUX4 and DUX4 target gene expression.

Recent findings:

Different studies show that DUX4 and its target genes can be repressed with genetic therapies using diverse strategies. Additionally, different small compounds can reduce DUX4 and its target genes in vitro and in vivo.

Summary:

Most studies that show DUX4 repression by genetic therapies have only been tested in vitro. More efforts should be made to test them in vivo for clinical translation. Several compounds have been shown to prevent DUX4 and target gene expression in vitro and in vivo. However, their efficiency and specificity has not yet been shown. With emerging clinical trials, the clinical benefit from DUX4 repression in FSHD will likely soon become apparent.

Keywords: Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy, DUX4, therapeutics, gene therapy

Introduction

Double homeobox 4 (DUX4) is a transcription factor implicated in zygotic genome activation (ZGA) during the 4-cell stage in human embryos where it acts as an activator of repetitive elements and cleavage-specific genes [1, 2]. DUX4 is considered to be epigenetically repressed in most somatic tissues, including in skeletal muscles. In patients with facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD; MIM 158900), a progressive neuromuscular disorder characterized by asymmetric weakness and wasting of the facial, scapular, and humeral muscles [3], epigenetic repression of the D4Z4 macrosatellite repeat is lost. This results in transcriptional activity from the DUX4 locus that is encoded within each D4Z4 repeat unit [4, 5]. DUX4 activates genes that are generally not expressed in non-affected skeletal muscles, including genes that are activated during ZGA and genes of the immune system [6, 7]. DUX4 overexpression in myogenic cells induces different toxic cascades including an increase in oxidative stress, nonsense-mediated decay inhibition, and inhibition of myogenesis. These changes ultimately lead to the death of myogenic cells [8–11]. In most patients (FSHD1), the disease is caused by a contraction of the D4Z4 repeat to 1–10 units while non-affected individuals carry 8–100 units [12]. FSHD can only occur when the contracted repeat is located on a permissive 4qA allele that contains a DUX4 polyadenylation signal (PAS) adjacent to the most distal D4Z4 unit. Non-permissive 4qB alleles lack this PAS, consequently DUX4 is not stably expressed [5]. Approximately 5% of patients (FSHD2) carry a permissive 4qA allele of 8–20 D4Z4 units together with a mutation in an epigenetic repressor of DUX4, namely SMCHD1, DNMT3B, or LRIF1 [13–15]. FSHD2 disease genes also act as modifiers in FSHD1, suggesting that FSHD1 and FSHD2 form a disease continuum resulting from the loss of epigenetic repression of DUX4 in skeletal muscle with shared clinical phenotypes [16–18].

Despite our increased understanding of the different genetic and epigenetic factors that contribute to FSHD development, there is no treatment that prevents or delays disease progression; only moderate exercise and cognitive behavioral therapy have shown some clinical benefit [19, 20]. Thus far, most clinical trials focused on blocking one of the downstream pathways of DUX4. Short-term treatment with the corticosteroid immunosuppressant prednisone did not significantly improve muscle strength or mass [21]. Treating patients with different antioxidants to reduce oxidative stress in the muscles only slightly improved physical performance [22]. As DUX4 activates many pathways, blocking one of them may not be sufficient. In this review, we will highlight recent progress made in developing new therapeutic strategies for FSHD, with a focus on approaches that prevent DUX4 expression, thereby affecting all downstream pathways.

Targeting the DUX4 transcript or the D4Z4 repeat with genetic therapies

FSHD is caused by a gain of function mechanism. DUX4 suppression is therefore a promising treatment strategy that should block all effects consequent to DUX4 activity in skeletal muscle. However, numerous highly homologous copies of DUX4 can be found in the human genome, and the D4Z4 repeat is extremely GC-rich, making it difficult to target. So far, most studies focused on blocking the DUX4 transcript as genomic editing has only recently become an exploitable alternative (Fig. 1, Table 1). Marsollier et al. and Chen et al. tested the efficiency of different antisense phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomers (PMOs) to target the DUX4 transcript [23, 24]. Both studies identified two PMOs that efficiently repressed DUX4 and target gene expression in FSHD myotube cultures. Chen et al. also tested the efficiency of a PMO that targets the DUX4 PAS in a xenograft mouse model containing an engrafted muscle biopsy of a FSHD patient and confirmed the reduction of DUX4 and target gene expression [24, 25]. Another study tested different antisense oligonucleotides (AONs) designed to interfere with DUX4 splicing or to target the DUX4 PAS [26]. All six AONs reduced the percentage of DUX4-positive nuclei and atrophic myotubes. As an alternative for PMOs and AONs, DNA aptamers with specific secondary structural elements that target the DUX4 protein can be designed that may improve specificity and affinity [27*]. Their efficiency in reducing DUX4 and target genes in myogenic cells has not yet been shown. Wallace et al. tested the use of RNA interference to inhibit the DUX4 transcript [28]. MicroRNA miDUX4.405 that targets one of the homeodomain-encoding sequences in the DUX4 open reading frame (ORF) reduced DUX4 expression and DUX4-induced muscle pathology in mice intramuscularly injected with AAV6.DUX4 and AAV6.miDUX4.405. The safety and toxicity of miDUX4.405 was assessed by injecting different concentrations intramuscularly or intravenously in wild-type mice. While miDUX4.405 was well tolerated, another DUX4 microRNA showed high toxicity in skeletal muscles [29*]. Finally, another study tested novel designed siRNAs and siRNAs that mimic the endogenously generated small RNAs targeting the DUX4 coding region and regions upstream of the coding region [30]. Both siRNAs targeting the coding and non-coding region reduced DUX4 and target gene expression in FSHD myotubes, indicating that the endogenous RNAi pathway is involved in maintaining the repressive state of D4Z4 and could be exploited to restore epigenetic repression.

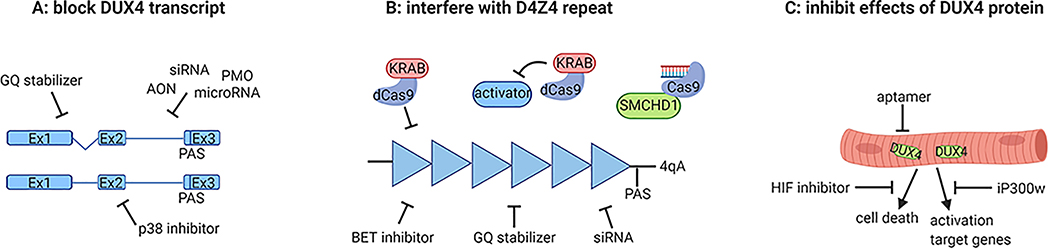

Figure 1.

Overview of described therapeutics and where they target. (A) Therapies that repress the DUX4 transcript. (B) Therapies that restore epigenetic repression of the D4Z4 repeat. Each triangle represents a D4Z4 repeat unit in euchromatic state. (C) Therapeutics that block the DUX4 protein or prevent muscle damage caused by the DUX4 protein.

Table 1.

Overview of studies and their main outcomes using different therapeutic strategies to repress DUX4

| Reference | Treatment | Model | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic therapies | |||

| Marsollier et al. [23] | PMO targeting DUX4 | Immortalized FSHD myotubes | ↓DUX4 transcript, ↓target genes |

| Chen et al. [24] | PMO targeting DUX4 | Primary FSHD muscle cells FSHD xenograft mouse model |

In vitro: ↓DUX4 protein, ↓target genes In vivo: ↓DUX4 transcript, ↓target genes |

| Ansseau et al. [26] | AON targeting DUX4 | Primary FSHD myoblast and myotubes | ↓DUX4 protein, ↓atrophic myotubes |

| Klingler et al. [27*] | Aptamers targeting DUX4 | - | Aptamers can bind to DUX4 protein |

| Wallace et al. [28,29*] | miDUX4.405 | Mice overexpressing DUX4 by AAV | ↓skeletal muscle pathology, ↓DUX4 transcript, ↑grip strength, low toxicity |

| Lim et al. [30] | siRNAs targeting coding and non-coding regions | Primary FSHD muscle cells | ↓DUX4 transcript, ↓target genes, |

| Himeda et al. [31] | CRISPR/dCas9 targeting D4Z4 locus | Primary FSHD myocytes | ↓DUX4 transcript, ↓target genes |

| Himeda et al. [32*] | CRISPR/dCas9 targeting D4Z4 activators | Primary FSHD myocytes | ↓DUX4 transcript |

| Goossens et al. [33**] | Restoring SMCHD1 with CRISPR/Cas9 | Gene edited FSHD monoclonal myotubes | ↓DUX4 transcript, ↓target genes, ↑wild-type SMCHD1 transcript |

| Small compounds | |||

| Bosnakovski et al. [35*] | iP300w | Myotubes from FSHD myoblast clonal cell lines iDUX4pA mice |

In vitro: ↓target genes In vivo: ↓target genes, ↓fibrosis genes |

| Campbell et al. [38] | BET inhibitors | Immortalized FSHD myogenic cells | ↓DUX4 transcript, ↓target genes |

| Ciszewski et al. [39*] | Berberine | Immortalized FSHD myoblasts/myotubes Mice overexpressing DUX4 by AAV |

In vitro: ↓DUX4 transcript, ↓target genes, ↑fusion index In vivo: ↓DUX4 protein, ↑muscle specific force |

| Oliva et al. [41**] | p38 inhibitors | Immortalized FSHD myotubes/myoblasts FSHD xenograft mouse model |

In vitro: ↓DUX4 transcript, ↓target genes In vivo: ↓DUX4 transcript, ↓target genes |

| Lek et al. [43**] | Hypoxia signalling inhibitors | Immortalized myoblasts FSHD primary myotubes |

Immortalized myoblasts: ↓DUX4-induced cell death, ↓DUX4 protein FSHD primary myotubes: ↓target genes |

Several studies used different approaches to re-establish epigenetic repression at the FSHD locus by targeting D4Z4 modifiers (Fig. 1B). Himeda et al. tested the recruitment of the transcriptional repressor KRAB to the D4Z4 repeat using catalytically inactive dCas9 in FSHD myocytes [31]. As dCas9 is unable to make double strand breaks in the genome, it should not induce permanent DNA damage at other sites, avoiding one of the main concerns for CRISPR-based therapeutics. The recruitment of KRAB promoted the repressive regulators KAP1, HP1α and HP1β at the D4Z4 repeat and as a result the expression of DUX4 and target genes was reduced. The same approach was used to repress the DUX4 activators BAZ1A, BRD2, KDM4C and SMARCA5 that were identified in a targeted knockdown screen in FSHD myocytes [32*]. By using the CRISPR/dCas9-KRAB approach, they confirmed that recruitment of KRAB to D4Z4 activators reduced DUX4 expression in FSHD myocytes. Another strategy is to genetically manipulate D4Z4 modifiers which most often have a single copy locus. Goossens et al. identified a SMCHD1 variant in a FSHD2 family leading to the inclusion of a pseudo-exon that disrupts the SMCHD1 ORF [33**]. Removal of the pseudo-exon by genome editing increased wild-type SMCHD1 transcript levels and reduced DUX4 and target gene expression in myotubes derived from the affected family. Furthermore, it has been shown that moderate SMCHD1 overexpression in FSHD1 and FSHD2 myotubes results in reduced DUX4 and target gene levels [34]. Thus, restoring SMCHD1 by gene editing could treat FSHD2 patients with a loss-of-function mutation in SMCHD1. For other FSHD patients, increasing SMCHD1-mediated repression of DUX4 could be an alternative strategy.

Blocking the DUX4 transcript or restoring epigenetic repression at the FSHD locus may prevent muscle damage in FSHD patients. However, most DUX4 therapeutics have only been tested in myocytes and are not yet designed to target skeletal muscles in vivo. To accelerate the availability of a therapy for patients, more efforts should be made to test novel therapeutics in animal models.

Therapeutic strategies using small compounds

As an alternative approach, compounds can be used to suppress DUX4 in a direct or indirect manner (Fig. 1, Table 1). An advantage is that some of these compounds are already tested for other diseases, therefore more is known about their safety. One study used a histone acetyltransferase p300 inhibitor (iP300w) to inhibit the DUX4 protein from activating its target genes as DUX4 utilizes p300 for this [35*, 36]. As expected, iP300w barely affected DUX4 expression in FSHD myotubes, but target gene expression was severely reduced. In vivo, iP300w administration prevented muscle mass loss and reduced the expression of target and fibrosis genes in iDUX4pA mice carrying a doxycycline-inducible DUX4 transgene [35*, 37]. Campbell et al. performed a screen in FSHD myogenic cells to identify novel compounds that reduce DUX4 expression [38]. Different BET bromodomain inhibitors that have already been tested in clinical trials for other diseases reduced DUX4 and target gene expression by inhibiting the BET protein BRD4. BET proteins enhance gene transcription by recruiting transcriptionally elements to acetylated chromatin. Another study tested berberine, a compound that binds and stabilizes certain secondary nucleic acid structures including G-quadruplexes (GQs) [39*]. Multiple GQs were identified within the enhancer and promoter regions of DUX4 and in the DUX4 transcript itself. In FSHD myoblasts, berberine treatment reduced DUX4 and target gene expression. To test the effect of berberine in vivo, mice injected intramuscularly with DUX4 AAVs received an intraperitoneally injection with berberine. Berberine reduced DUX4 protein expression and some DUX4-mediated muscle pathology, but overall the effect was mild [39*].

Two studies reported that DUX4 can be repressed by enhancing cyclic adenosine monophosphate levels using β2 adrenergic receptor agonists or phosphodiesterase inhibitors [38, 40]. Recently, both Fulcrum Therapeutics and Oliva et al. reported DUX4 suppression by p38α/β mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) inhibition [41**, 42*]. p38 MAPK is activated by β2 adrenergic signaling and responds to different stress stimuli. Several commercially available p38 inhibitors reduced DUX4 and target gene expression in FSHD myotubes and myoblasts [41**]. To study the effect of p38 inhibitors in vivo, losmapimod and PH-797804 were tested in a FSHD xenograft mouse model containing transplanted FSHD myoblasts after barium chloride-induced muscle damage. Both inhibitors reduced DUX4 and target gene expression in the xenografted tibialis anterior muscle, however the exact mechanism of DUX4 suppression by p38 inhibitors is unknown. Fulcrum Therapeutics is currently performing a clinical trial testing losmapimod in FSHD patients. The first results are expected mid-2020. Finally, a genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 screening approach was recently performed in a myoblast cell line containing a doxycycline-inducible DUX4 transgene with the aim to identify new pathways involved in DUX4-induced cell death [43**]. Doxycycline-induced myoblasts usually die within 48 hours, therefore edited cells that survive were hypothesized to carry loss-off-function mutations in genes required for DUX4-induced cell death. In DUX4-resistant cells, loss-off-function mutations were identified in multiple hypoxia signaling pathway genes including in HIF1A and ARNT, subunits of the transcription factor HIF-1. Treatment with HIF signaling inhibitors reduced the amount of DUX4 protein, target gene expression and cell death (Fig. 1C). Different FDA-approved hypoxia signaling inhibitors are available, which could lead to a rapid clinical translation. Also, the other unexplored genes that were identified in this screen may reveal new pathways involved in DUX4-induced cell death.

The above described therapeutics can be tested in the short term in clinical trials as most compounds have already been studied in FSHD mouse models or tested in clinical trials for other diseases. However, some of these therapeutics target factors, like p300 and p38 that are involved in many other pathways, may give significant side effects in patients [44, 45].

Conclusion

At present, there is no therapy that prevents or delays disease progression in FSHD patients. Most studies targeting DUX4 have only performed experiments in myoblast and myotube cultures derived from patients. Because of the complex disease mechanism, the restriction of the D4Z4 repeat to primates, the heterogeneity of DUX4 expression, and the toxicity of DUX4 during development, animal models to test new therapeutic strategies were scarce [7, 46, 47]. Recently, different mouse models with controllable DUX4 expression in skeletal muscles have been developed [37, 48–50]. These models open a new window for the development and safety assessment of new therapeutics.

As skeletal muscles compromise a large part of the body, the delivery of the therapeutics may not be efficient and administration of high doses can be toxic. For example, the life time of AONs are short and PMOs show difficulties in penetrating the cell membrane. Adjustments in their backbone can be made to increase their stability and delivery to the skeletal muscles [51]. As not all skeletal muscles are equally affected in FSHD patients, local delivery to a limited number of muscles that are the most affected or the most important for maintaining independence may be considered. Also, it is unknown to what level DUX4 needs to be suppressed in skeletal muscles. DUX4 expression has been reported in myogenic cells and skeletal muscle biopsies in unaffected individuals, suggesting that low levels of DUX4 may be tolerated [52]. Finally, DUX4 was considered to be silenced in all somatic tissues, but recently DUX4 has been detected in the thymus and epidermis of healthy controls [53, 54]. More research is needed to determine whether DUX4 has a function in somatic tissues and what the consequences of DUX4 suppression are.

Key points.

As there is no molecular therapy that prevents or delays disease progression in FSHD patients, there is a high clinical need for new therapeutic strategies.

Inappropriate expression of DUX4 in skeletal muscles causes FSHD, therefore preventing DUX4 or target gene expression should block all toxic downstream pathways.

Using AONs and PMOs could be a promising therapeutic strategy for FSHD as they only target the disease gene.

Different small compounds that have been tested for other diseases show promising results in vitro and in vivo, and can be tested in clinical trials in the short term.

Acknowledgements

We apologize to the many investigators whose work we could not cite because of space limitations and we thank all patients and family members for their participation in our studies. The authors are members of the European Reference Network for Rare Neuromuscular Diseases [ERN EURO-NMD].

Financial support and sponsorship

Our FSHD research is supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke P01NS069539), the Prinses Beatrix Spierfonds (W.OP14-01; W.OR15-26; W.OR17-04; W.OR19-06), the FSHD Society (Sylvia & Leonard Marx Foundation Fellowship FSHS-82017-02), the European Union Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program (Marie Skłodowska-Curie Individual Fellowship 795655), and Spieren voor Spieren.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

Silvère M. van der Maarel is co-inventor on several FSHD-related patent applications and consultant for Fulcrum Therapeutics.

References

- 1.De Iaco A, Planet E, Coluccio A, et al. DUX-family transcription factors regulate zygotic genome activation in placental mammals. Nature genetics. 2017;49(6):941–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hendrickson PG, Dorais JA, Grow EJ, et al. Conserved roles of mouse DUX and human DUX4 in activating cleavage-stage genes and MERVL/HERVL retrotransposons. Nature genetics. 2017;49(6):925–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deenen JC, Arnts H, van der Maarel SM, et al. Population-based incidence and prevalence of facioscapulohumeral dystrophy. Neurology. 2014;83(12):1056–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daxinger L, Tapscott SJ, van der Maarel SM. Genetic and epigenetic contributors to FSHD. Current opinion in genetics & development. 2015;33:56–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lemmers RJ, van der Vliet PJ, Klooster R, et al. A unifying genetic model for facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Science (New York, NY). 2010;329(5999):1650–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geng LN, Yao Z, Snider L, et al. DUX4 activates germline genes, retroelements, and immune mediators: implications for facioscapulohumeral dystrophy. Developmental cell. 2012;22(1):38–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong CJ, Wang LH, Friedman SD, et al. Longitudinal measures of RNA expression and disease activity in FSHD muscle biopsies. Human molecular genetics. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feng Q, Snider L, Jagannathan S, et al. A feedback loop between nonsense-mediated decay and the retrogene DUX4 in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. eLife. 2015;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turki A, Hayot M, Carnac G, et al. Functional muscle impairment in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy is correlated with oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction. Free radical biology & medicine. 2012;53(5):1068–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banerji CRS, Panamarova M, Hebaishi H, et al. PAX7 target genes are globally repressed in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy skeletal muscle. Nature communications. 2017;8(1):2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bosnakovski D, Toso EA, Hartweck LM, et al. The DUX4 homeodomains mediate inhibition of myogenesis and are functionally exchangeable with the Pax7 homeodomain. Journal of cell science. 2017;130(21):3685–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tawil R, van der Maarel SM, Tapscott SJ. Facioscapulohumeral dystrophy: the path to consensus on pathophysiology. Skeletal muscle. 2014;4:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lemmers RJ, Tawil R, Petek LM, et al. Digenic inheritance of an SMCHD1 mutation and an FSHD-permissive D4Z4 allele causes facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy type 2. Nature genetics. 2012;44(12):1370–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van den Boogaard ML, Lemmers R, Balog J, et al. Mutations in DNMT3B Modify Epigenetic Repression of the D4Z4 Repeat and the Penetrance of Facioscapulohumeral Dystrophy. American journal of human genetics. 2016;98(5):1020–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamanaka K, Šikrová D, Mitsuhashi S, et al. A homozygous non-sense variant in LRIF1 associated with facioscapulohumeral muscu-lar dystrophy. Neurology. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Greef JC, Lemmers RJ, Camano P, et al. Clinical features of facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy 2. Neurology. 2010;75(17):1548–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Greef JC, Lemmers RJ, van Engelen BG, et al. Common epigenetic changes of D4Z4 in contraction-dependent and contraction-independent FSHD. Human mutation. 2009;30(10):1449–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sacconi S, Briand-Suleau A, Gros M, et al. FSHD1 and FSHD2 form a disease continuum. Neurology. 2019;92(19):e2273–e85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Voet N, Bleijenberg G, Hendriks J, et al. Both aerobic exercise and cognitive-behavioral therapy reduce chronic fatigue in FSHD: an RCT. Neurology. 2014;83(21):1914–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andersen G, Prahm KP, Dahlqvist JR, et al. Aerobic training and postexercise protein in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy: RCT study. Neurology. 2015;85(5):396–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tawil R, McDermott MP, Pandya S, et al. A pilot trial of prednisone in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. FSH-DY Group. Neurology. 1997;48(1):46–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Passerieux E, Hayot M, Jaussent A, et al. Effects of vitamin C, vitamin E, zinc gluconate, and selenomethionine supplementation on muscle function and oxidative stress biomarkers in patients with facioscapulohumeral dystrophy: a double-blind randomized controlled clinical trial. Free radical biology & medicine. 2015;81:158–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marsollier AC, Ciszewski L, Mariot V, et al. Antisense targeting of 3’ end elements involved in DUX4 mRNA processing is an efficient therapeutic strategy for facioscapulohumeral dystrophy: a new gene-silencing approach. Human molecular genetics. 2016;25(8):1468–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen JC, King OD, Zhang Y, et al. Morpholino-mediated Knockdown of DUX4 Toward Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy Therapeutics. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2016;24(8):1405–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y, King OD, Rahimov F, et al. Human skeletal muscle xenograft as a new preclinical model for muscle disorders. Human molecular genetics. 2014;23(12):3180–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ansseau E, Vanderplanck C, Wauters A, et al. Antisense Oligonucleotides Used to Target the DUX4 mRNA as Therapeutic Approaches in FaciosScapuloHumeral Muscular Dystrophy (FSHD). Genes. 2017;8(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klingler C, Ashley J, Shi K, et al. DNA aptamers against the DUX4 protein reveal novel therapeutic implications for FSHD. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2020;34(3):4573–90.* This study provides a new therapeutic strategy to block the DUX4 protein instead of the DUX4 transcript, however its efficiency has not been shown in FSHD myogenic cells or mice.

- 28.Wallace LM, Liu J, Domire JS, et al. RNA interference inhibits DUX4-induced muscle toxicity in vivo: implications for a targeted FSHD therapy. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2012;20(7):1417–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wallace LM, Saad NY, Pyne NK, et al. Pre-clinical Safety and Off-Target Studies to Support Translation of AAV-Mediated RNAi Therapy for FSHD. Molecular therapy Methods & clinical development. 2018;8:121–30.* This study emphasizes the importance of testing the safety of therapeutics in animal models as one of the two tested microRNA’s induced skeletal muscle damage in wild type mice.

- 30.Lim JW, Snider L, Yao Z, et al. DICER/AGO-dependent epigenetic silencing of D4Z4 repeats enhanced by exogenous siRNA suggests mechanisms and therapies for FSHD. Human molecular genetics. 2015;24(17):4817–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Himeda CL, Jones TI, Jones PL. CRISPR/dCas9-mediated Transcriptional Inhibition Ameliorates the Epigenetic Dysregulation at D4Z4 and Represses DUX4-fl in FSH Muscular Dystrophy. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2016;24(3):527–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Himeda CL, Jones TI, Virbasius CM, et al. Identification of Epigenetic Regulators of DUX4-fl for Targeted Therapy of Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2018;26(7):1797–807.* This research group shows that the dCas9 system can be used to repress DUX4 by recruiting KRAB to the D4Z4 repeat or to DUX4 enhancers. dCas9 is catalytically inactive and should not be able to induce permanent DNA damage.

- 33.Goossens R, van den Boogaard ML, Lemmers R, et al. Intronic SMCHD1 variants in FSHD: testing the potential for CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing. Journal of medical genetics. 2019;56(12):828–37.** This is the first study that shows that restoring SMCHD1 by gene editing can repress DUX4 in FSHD2 myotubes.

- 34.Balog J, Thijssen PE, Shadle S, et al. Increased DUX4 expression during muscle differentiation correlates with decreased SMCHD1 protein levels at D4Z4. Epigenetics. 2015;10(12):1133–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bosnakovski D, da Silva MT, Sunny ST, et al. A novel P300 inhibitor reverses DUX4-mediated global histone H3 hyperacetylation, target gene expression, and cell death. Science advances. 2019;5(9):eaaw7781.* This study shows that preventing DUX4 from activating its target genes can reduce skeletal muscle damage in FSHD mice.

- 36.Choi SH, Gearhart MD, Cui Z, et al. DUX4 recruits p300/CBP through its C-terminus and induces global H3K27 acetylation changes. Nucleic acids research. 2016;44(11):5161–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bosnakovski D, Chan SSK, Recht OO, et al. Muscle pathology from stochastic low level DUX4 expression in an FSHD mouse model. Nature communications. 2017;8(1):550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Campbell AE, Oliva J, Yates MP, et al. BET bromodomain inhibitors and agonists of the beta-2 adrenergic receptor identified in screens for compounds that inhibit DUX4 expression in FSHD muscle cells. Skeletal muscle. 2017;7(1):16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ciszewski L, Lu-Nguyen N, Slater A, et al. G-quadruplex ligands mediate downregulation of DUX4 expression. Nucleic acids research. 2020.* This study identified G-quadruplex secondary structures in the DUX4 transcript and enhancer and promoter regions of DUX4. Stabilizing these secondary structures reduced DUX4 and target gene expression.

- 40.Cruz JM, Hupper N, Wilson LS, et al. Protein kinase A activation inhibits DUX4 gene expression in myotubes from patients with facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2018;293(30):11837–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oliva J, Galasinski S, Richey A, et al. Clinically Advanced p38 Inhibitors Suppress DUX4 Expression in Cellular and Animal Models of Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2019;370(2):219–30.** Both Oliva et al. and Fulcrum Therapeutics identified p38 inhibitors as a new treatment for FSHD.

- 42.Alejandro Rojas EV L, Accorsi Anthony, Maglio Joseph, Shen Ning, Robertson Alan, Kazmirski Steven, Rahl Peter, Tawil Rabi, Cadavid Diego, Thompson Lorin A., Ronco Lucienne, Chang Aaron N., Cacace Angela M., Wallace Owen. P38α Regulates Expression of DUX4 in Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy. BioRxiv. 2019.* Both Fulcrum Therapeutics and Oliva et al. identified losmapimod as a compound to prevent DUX4 expression. Fulcrum Therapeutics is currently testing losmapimod in FSHD patients.

- 43.Lek A, Zhang Y, Woodman KG, et al. Applying genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 screens for therapeutic discovery in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Science translational medicine. 2020;12(536).** This is the first published CRISPR-Cas9 based screen that identifies new compounds that may be used to treat FSHD. In contrast to other screens, it is aimed to find compounds that prevent DUX4-induced cell death instead of inhibiting DUX4 and target gene expression.

- 44.Goodman RH, Smolik S. CBP/p300 in cell growth, transformation, and development. Genes & development. 2000;14(13):1553–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cuenda A, Rousseau S. p38 MAP-kinases pathway regulation, function and role in human diseases. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2007;1773(8):1358–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leidenroth A, Hewitt JE. A family history of DUX4: phylogenetic analysis of DUXA, B, C and Duxbl reveals the ancestral DUX gene. BMC Evol Biol. 2010;10:364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van den Heuvel A, Mahfouz A, Kloet SL, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy disease etiology and development. Human molecular genetics. 2019;28(7):1064–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Giesige CR, Wallace LM, Heller KN, et al. AAV-mediated follistatin gene therapy improves functional outcomes in the TIC-DUX4 mouse model of FSHD. JCI insight. 2018;3(22). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jones T, Jones PL. A cre-inducible DUX4 transgenic mouse model for investigating facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. PloS one. 2018;13(2):e0192657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bosnakovski D, Shams AS, Yuan C, et al. Transcriptional and cytopathological hallmarks of FSHD in chronic DUX4-expressing mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nguyen Q, Yokota T. Antisense oligonucleotides for the treatment of cardiomyopathy in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. American journal of translational research. 2019;11(3):1202–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jones TI, Chen JC, Rahimov F, et al. Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy family studies of DUX4 expression: evidence for disease modifiers and a quantitative model of pathogenesis. Human molecular genetics. 2012;21(20):4419–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Das S, Chadwick BP. Influence of Repressive Histone and DNA Methylation upon D4Z4 Transcription in Non-Myogenic Cells. PloS one. 2016;11(7):e0160022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gannon OM, Merida de Long L, Saunders NA. DUX4 Is Derepressed in Late-Differentiating Keratinocytes in Conjunction with Loss of H3K9me3 Epigenetic Repression. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2016;136(6):1299–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]