Abstract

Pediatric trigger thumb is the new terminology for the so-called congenital trigger thumb. This change in appellation was suggested based on recent knowledge acquired through prospective studies of a large number of newborns for the presence of trigger thumb at birth across many centers. In this background, we came across a newborn with trigger thumb which was diagnosed right after birth, putting aside all theories of nonexistence of congenital trigger thumb. We report a case of congenital trigger thumb diagnosed at birth, which was managed surgically at 9 months of age, who has good clinical and functional outcomes at 1-year follow-up. Herewith, we would like to submit that congenital trigger thumb does exist, though might be a very rare occurrence.

Keywords: congenital, pediatric, trigger, thumb

Introduction

The term “congenital trigger thumb” is believed to be a misnomer and almost completely replaced by the term “pediatric trigger thumb” for the past two decades. 1 Some authors have recommended the term “developmental trigger thumb” for this condition. 2 In this background, we report a case of pediatric/congenital trigger thumb which was diagnosed right after birth and was managed by surgical release of the A1 pulley.

Case Report

A full-term, 3.2-kg male infant, second born child of nonconsanguineous parents, delivered by elective cesarean section was subjected to routine clinical examination by an attending pediatric orthopaedic surgeon immediately after birth. Though unusual for a pediatric orthopaedic surgeon to attend obstetric theaters for neonatal screening, this happened here as the infant was the son of the pediatric orthopaedic surgeon himself.

The infant was active and crying normally. General examination was unremarkable but for a small preauricular tag in the left ear. The hips and spine were normal. The right hand had flexion deformity at the interphalangeal joint of the thumb (80 degrees) ( Fig. 1 ). The deformity was fixed and could not be corrected, though a jog of 5 to 10 degrees movement was possible at the interphalangeal joint. A palpable firm nodule was present proximal to the thumb metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint crease similar to the classical description of Notta’s nodule. The rest of the examinations of the upper limbs and the hand were normal. A clinical diagnosis of locked congenital trigger thumb right hand was made and the infant was started on passive stretching from day 1 of birth. Differential diagnosis of congenital absence of the extensor of thumb or congenital flexion contracture of the thumb was also considered, but the presence of Notta’s nodule favored toward the diagnosis of trigger thumb.

Fig. 1.

Preoperative clinical photograph showing 90 degrees flexion at the interphalangeal joint of right thumb.

At 9 months of life, as there was no improvement in the deformity with regular stretching exercise and it was a locked triggering due to the nodule, it was planned for surgical intervention. Under general anesthesia, with add-on brachial block surgical release of the A1 pulley of the right thumb was done through an incision placed over the thumb MCP joint crease. The surgery was performed under loupe magnification and the radial and ulnar neurovascular bundles were identified and retracted on either side to expose the flexor pollicis tendon and its sheath. On exploration, the A1 pulley of the thumb was found to be thick and there was a thick nodular swelling of the flexor pollicis longus just proximal to the A1 pulley (Notta’s nodule). On releasing the A1 pulley, full correction of the thumb interphalangeal joint contracture could be achieved. We could get full extension intraoperatively and 10 degrees of hyperextension was possible. As the findings were compatible with the diagnosis of the trigger thumb, the extensor apparatus was not exposed. However, the tenodesis test (flexion of the MCP and carpometacarpal joint of the thumb causing passive extension of the interphalangeal joint) suggested intactness of the extensor apparatus. Wound was closed with absorbable sutures and a bulky dressing was provided for 1 week. Passive stretching of the thumb was advised. The postoperative period was uneventful and the child started using his thumb normally for all activities. At 1-year follow-up, the passive range of interphalangeal joint movement was normal with 10 degrees of hyperextension possible, and there was no evidence of retriggering ( Fig. 2A B ).

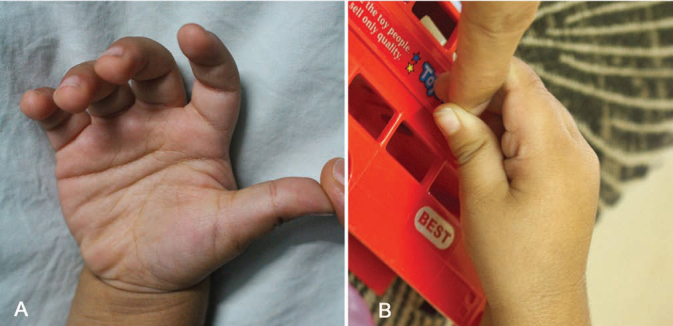

Fig. 2.

Postoperative clinical photograph at 1-year follow-up showing complete correction of deformity with 10 degrees passive hyperextension ( A ) and 10 degrees active hyperextension ( B ) at the interphalangeal joint of right thumb.

Discussion

The incidence of pediatric trigger thumb is ~3.3 per 1,000 live births. 3 The existence of true congenital trigger thumb has been questioned by many authors in the past. 4 5 6 7 Dinham and Meggit performed the study which reported 19 patients of congenital trigger thumb detected at birth among 105 patients in their series way back in 1974. However, none of these patients was seen at birth by the treating physician, and hence, the value of this information based on parent’s history was questioned. In 1983, Neu and Murray reported a case of twins with bilateral trigger digits which was noted by parents only when they were 6 months and they stated that one of the difficulty in identifying them early might be due to the tendency of the neonates and infants to hold the thumb in flexed position while at rest. 8 In 1991, Ger et al reported 11 infants with trigger thumb at birth in their series of 41 infants with 53 trigger thumbs. 9 In this series too, none of them was seen at birth.

To the best of our knowledge, till date, no single case of congenital trigger thumb which was noticed by a neonatologist or orthopaedic surgeon at birth is reported in the English literature. Many prospective studies have been done to prove the hypothesis that trigger thumb in the pediatric population is not congenital, but acquired. Hence, now it is very much accepted and believed that trigger thumb is not congenital, and hence, the terminology “pediatric trigger thumb” is widely used in the literature.

Rodgers and Waters in 1994 reported the results of their prospective study of 1,046 infants for trigger digits or Notta’s nodule and concluded that the incidence was zero in their study. 4

In 1996, Slakey and Hennrikus suggested that this condition be called as “acquired thumb flexion contracture in children” based on the results of screening of 4,719 consecutive newborn in which they failed to identify any triggering digit at birth. 5

In 2001, there was another report from Korea which again had zero incidence of trigger digit at birth after screening of 7,700 neonates. 5 The last study done in the same lines was from Japan in 2006 by Kikuchi and Ogino. 7 In this study, screening of 1,116 neonates did not reveal a single trigger thumb, but two children from the same group developed trigger thumb at 8 and 11 months. This study strongly proved the acquired nature of the condition in their population.

We report the first case of congenital trigger thumb which was diagnosed right after birth. Our case was a unique situation where the attending pediatric orthopaedic surgeon himself examined his own son immediately after delivery and diagnosed to have locked trigger thumb of right hand. We were skeptical about putting the diagnosis as congenital trigger thumb as the literature supports it be nonexisting. We also considered the differential diagnosis of congenital absence of thumb extensor tendons and congenital flexion contracture. However, the presence of Notta’s nodule and absence of skin contracture favored the diagnosis of trigger thumb. During surgery, just the release of the A1 pulley completely corrected the thumb flexion deformity and the tenodesis test (flexion of the MCP and carpometacarpal joint of the thumb causing passive extension of the interphalangeal joint) confirmed the intactness of the extensor apparatus and complete release of the trigger. At 1-year follow-up, the child is doing well with full flexion and 10 degrees of hyperextension with no evidence of retriggering. A systematic analysis published in 2014 has shown 82% successful outcomes after surgery, while that for nonoperative treatment, it was only 65%. 3 Since there was no single case of trigger thumb reported to be diagnosed at birth, we felt that this case is worth reporting.

In 2012, Shah and Bae in their review article on pediatric trigger thumb have inferred that no single case of congenital trigger thumb was identified on screening of 14,581 newborns and hence called it a misnomer. 1 The world is fairly convinced that trigger thumb in children is an acquired condition and the terminology of “pediatric trigger thumb” is well accepted. Herdem et al suggested the term “developmental trigger thumb” for this condition owing to the variation in presentation and existing controversy in terminology similar to change in terminology for congenital dislocation of hip. 2 We would like to stress the point that pediatric trigger thumb could either be congenital or developmental. Understandably, the congenital presentation of pediatric trigger thumb is an extremely rare occurrence. We feel that it is not reported so far as the neonatologists who routinely screen the newborn for congenital anomalies do not look for trigger digits specifically. If examination of trigger digits specifically becomes a part of the routine neonatal examination similar to Ortolani and Barlow’s test for hip dysplasia, we hope that there would be more cases similar to this report in future. Nevertheless, with this report, it becomes evident that the so-called pediatric trigger thumb could be present at birth and it would not be unreasonable to look for it specifically while screening a newborn for congenital musculoskeletal anomalies.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None declared.

References

- 1.Shah A S, Bae D S. Management of pediatric trigger thumb and trigger finger. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20(04):206–213. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-20-04-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herdem M, Bayram H, Toğrul E, Sarpel Y. Clinical analysis of the trigger thumb of childhood. Turk J Pediatr. 2003;45(03):237–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farr S, Grill F, Ganger R, Girsch W. Open surgery versus nonoperative treatments for paediatric trigger thumb: a systematic review. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2014;39(07):719–726. doi: 10.1177/1753193414523245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodgers W B, Waters P M. Incidence of trigger digits in newborns. J Hand Surg Am. 1994;19(03):364–368. doi: 10.1016/0363-5023(94)90046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slakey J B, Hennrikus W L. Acquired thumb flexion contracture in children: congenital trigger thumb. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78(03):481–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moon W N, Suh S W, Kim I C. Trigger digits in children. J Hand Surg [Br] 2001;26(01):11–12. doi: 10.1054/jhsb.2000.0417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kikuchi N, Ogino T. Incidence and development of trigger thumb in children. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31(04):541–543. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2005.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neu B R, Murray J F. Congenital bilateral trigger digits in twins. J Hand Surg Am. 1983;8(03):350–352. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(83)80180-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ger E, Kupcha P, Ger D. The management of trigger thumb in children. J Hand Surg Am. 1991;16(05):944–947. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(10)80165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]