What physiologic monitors should we use in the operating room? Though it has been over 173 years since William T. G. Morton first successfully administered a general anesthetic, the question of how we should monitor patients under anesthesia care remains an area of passionate debate, and the subject of an article in this issue of Anesthesia & Analgesia.1 Before we delve into this debate and the article’s recommendations, it is worth reviewing several points about the use of monitoring in general and the evidence for improving outcomes.

Speedometers and Intraoperative Monitors: They do not act by themselves

First, the use of a monitor does not improve outcomes or prevent adverse events unless the actions taken by the anesthesiologist interpreting the monitors are therapeutic and timely. Though we lack firm data, we believe it is highly likely that nearly all high speed motor vehicle collisions in the United States in 2019 involved cars with functioning speedometers. That speedometers did not prevent these high speed accidents comes as no surprise. We know that speedometers don’t prevent cars from exceeding the speed limit, they simply provide information to drivers. How individual drivers use that information to decide whether to step on the gas or the brakes depends on a complex set of calculations: how much the driver believes in following laws, whether the driver is in a hurry, fears a speeding ticket, thinks that speeding will increase the chance an accident, etc. Similarly, we are unaware of any intraoperative monitor that itself improves outcomes without a proper response by an anesthesiologist “driver.” Just as drivers use the information from speedometers to make decisions that affect the risk of car accidents, anesthesiologists use information from intraoperative monitors to make decisions and take actions that affect patient outcomes.

Although obvious, this is a key point to remember when considering the literature on EEG monitoring and patient outcomes. The trials discussed by the POQI article1 used the BIS monitor in different ways, and in some studies, the BIS index was used with raw EEG waveform analysis to change care.2–4 Since EEG monitoring was used in different ways in these studies, it is difficult to conclude whether EEG monitoring in general or BIS monitoring in particular is associated with improved outcomes. Trying to determine whether intraoperative EEG monitoring alters outcomes is like asking whether speedometers reduce car accidents. Unless we know how individual anesthesiologist “drivers” respond to monitored information, we cannot answer this question.

The POQI article provides a series of forest plots that quantitatively measure the effects of (processed) EEG monitoring in recent studies. Yet, in each of these studies, the monitors simply provided data to anesthesia providers, who then acted on this information in different ways. For example, in the ENGAGES trial, clinicians acted upon EEG monitor data to reduce anesthetic administration from 0.80 to 0.69 MAC (a reduction of 0.11 MAC),2 while in the CODA trial, clinicians acted upon EEG monitor data to reduce anesthetic dosage from 0.93 to 0.57 MAC (a 0.36 MAC reduction),5 a >3 fold larger absolute reduction in anesthetic dosage than that seen in ENGAGES. In essence, the results of these two studies do not reflect opposing arguments on whether EEG usage prevents delirium; instead, they both support the idea that it is how anesthesiologists use the data from these monitors to alter patient care that changes outcomes.

Monitors and parachutes: They can be useful

Yet, even this discussion is overly simplistic, as the use of a device or monitor to prevent an adverse event will differ based on the clinical context and patient cohort in which it is used. Parachutes are widely believed to prevent death among people jumping out of airplanes, yet a recent randomized controlled trial showed that using parachutes didn’t prevent deaths among people jumping out of airplanes- when the planes were already on the ground!6 The extent to which a monitor can prevent an adverse event depends on the population and situation in which it is implemented. Just as parachutes don’t prevent mortality in individuals jumping out of airplanes on the ground (in whom the baseline mortality risk is virtually non-existent), EEG monitoring (and tight anesthetic titration) is unlikely to help anesthesiologists reduce complication rates (ranging from delirium to intraoperative awareness) in patients at low risk for these complications, such as a 20-year old ASA-I patient undergoing a laparoscopic appendectomy. Consistent with this idea, a recent study in healthy volunteers undergoing general anesthesia without surgery found no correlation between the duration of burst suppression, an indicator of a brain state far deeper than necessary to prevent awareness, and emergence times or other outcomes.7

The Four Questions of Intraoperative Monitoring

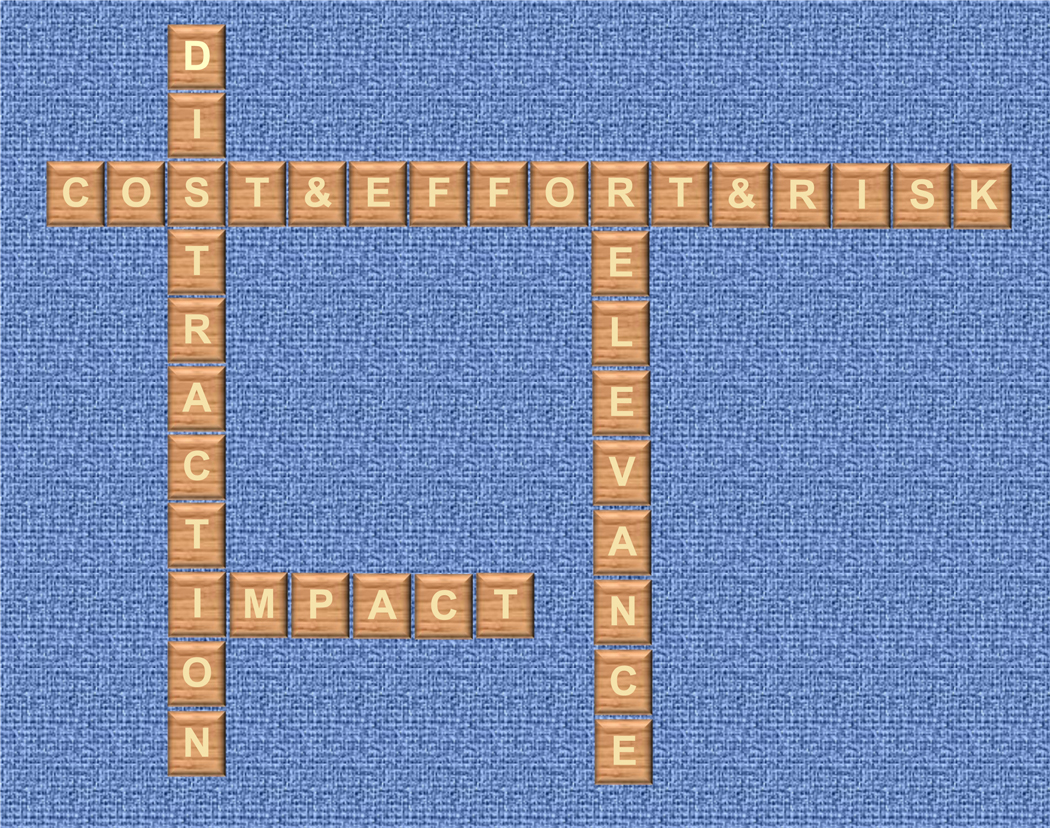

So, where does this leave us when deciding whether to use intraoperative EEG monitoring? We believe there are four general considerations that should drive the decision to use any monitor (including EEG) in the operating room (Fig. 1). First, how relevant is the information from the monitor for understanding how the patient’s physiology is being modulated by anesthetic drugs/techniques and surgical procedures? Second, to what extent are anesthesiologists likely to alter a patient’s care based on information from the monitor? Third, how much effort, cost, and risk is associated with use of the monitor? Fourth, how much does using the monitor detract from other urgent priorities or tasks in the operating room?

Figure 1.

The 4 questions for deciding whether to use an intraoperative monitor.

For the first question, the answer is mixed. On the one hand, the central nervous system (CNS) is the target organ for most if not all anesthetic drugs, which would argue that we should always monitor CNS activity to understand what our drugs are doing to the brain. Yet, there is no consensus on what the exact EEG correlates of amnesia or unconsciousness are,8 so it remains unclear what EEG monitors should be used, what aspects of the EEG raw waveform or spectrogram should be monitored, or what processed EEG measures should be utilized.

To help convey our limited knowledge here, it is useful to compare processed EEG to ECG monitoring. If an attending anesthesiologist asks a resident “how does the ECG look?” an answer of “Good, it is 70” is likely to be viewed as inadequate. A more informative response would be “the ECG shows a normal sinus rhythm at a rate of 70, with normal axes and intervals, narrow QRS complexes, and flat ST segments” which conveys a sophisticated understanding of the function of the cardiac conduction system and the extent to which the heart is receiving sufficient oxygen to meet metabolic requirements. Unfortunately, we are nowhere close to being able to describe the brain with this level of sophistication based on processed EEG information, even though there are some raw EEG patterns clearly visible on spectrogram plots that predict adverse patient outcomes.9 Since these raw EEG waveform patterns that predict adverse outcomes are not detectable by simple processed EEG index values, this suggest that anesthesiologists should learn how to read and interpret raw EEG waveforms and spectrograms.

Further, it makes little sense to avoid monitoring the target organ of our anesthetic drugs. Dosing anesthetics based on their side effects (such as hypotension) on other organ systems (such as the cardiovascular system) without monitoring their target organ (the central nervous system) makes about as much sense as if internists dosed antihypertensive drugs like ACE inhibitors based entirely on their side effects (such as dizziness) on other organs (i.e. the brain) without measuring their effects on their target organ (the cardiovascular system).10 That would be inappropriate for an internist, so why is this same logic acceptable for anesthesiologists? Further, one could argue that it is important to monitor the target organ of anesthetic drugs (the brain) just as we monitor patients’ oxygen saturation during surgery, even though pulse oximetry has not been shown to reduce overall complication rates,11 because both provide highly relevant physiologic information.

For the second question, “to what extent are anesthesiologists likely to alter a patient’s care based on information from the monitor?” the answer is again mixed. Prospective studies utilizing processed EEG monitoring in different ways have shown varying effects on anesthetic titration/administration,2,3,12 and observational studies have shown no decrease (and even a slight increase) in anesthetic dosage among patients who underwent BIS monitoring vs routine care.13 The different effects on anesthetic titration across these studies may partly reflect the fact that BIS index values are not simply a reflection of anesthetic dosage, but rather change as a function of both patient age and preoperative cognitive function.13,14 These results also likely suggest that anesthesiologists provided with the same processed EEG monitor data make different decisions about anesthetic titration and care. This variability in clinical decision making is not surprising- prior studies have also found substantial variability in treatment decisions made by different clinicians in response to the same data from pulmonary artery catheters.15

For the third question about effort, cost, and risk, frontal EEG monitoring involves little effort, minor cost (relative to other perioperative costs), and minimal risk. Unlike other intraoperative monitors such as pulmonary artery catheters whose placement can be associated with life threating adverse events such as pulmonary artery rupture, placing a frontal EEG monitor sticker has not been shown to produce significant risk of patient harm.

For the fourth question, “how much does using the monitor detract from other urgent priorities or tasks in the Operating Room?” the answer will likely differ depending on the surgical case, anesthetic technique, patient factors, and provider preference and familiarity with a given EEG monitor.

Thus, aside from the forest plots and statistical calculations provided by this thorough POQI article, we believe that the question of whether to use intraoperative EEG monitoring should be guided by the answers to these four questions by individual clinicians on a case-by-case basis. Different clinicians may even disagree about whether EEG monitoring should be used or will be helpful in improving outcomes. Such disagreements are reasonable based on current evidence. Monitors do not alter patient outcomes; it is the decisions made and the actions taken by anesthesiologists (sometimes in response to data from monitors) that affect patient outcomes. Beyond the current debate on whether current EEG monitors improve the care of today’s patients, attaining a deeper understanding of how anesthetic drugs modulate brain activity to produce general anesthesia (and how to detect such effects via EEG waveform analysis) are fundamentally important goals for our field, ones that may be relevant to understanding altered brain states associated with perioperative neurocognitive disorders,16 and which will likely lead to better EEG monitors and outcomes for future patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Dr. Berger acknowledges funding from National Institutes of Health K76 AG057022, additional support from National Institutes of Health P30AG028716 (to Dr. Berger), an Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation Program to Accelerate Clinical Trials (PACT) grant, a Jahnigen Scholars Fellowship award from the American Geriatrics Society/Foundation for Anesthesia Education and Research, and support from the Duke Anesthesiology Department.

Glossary of Terms

- POQI

Perioperative Quality Initiative

- EEG

Electroencephalogram

- BIS

Bispectral Index

- ENGAGES

Electroencephalography Guidance of Anesthesia to Alleviate Geriatric Syndromes

- MAC

Minimum Alveolar Concentration

- CODA

Cognitive Dysfunction after Anesthesia

- ASA

American Society of Anesthesiologists

- ECG

Electrocardiogram

- ACE

Angiotensin-Converting-Enzyme

Contributor Information

Miles Berger, Department of Anesthesiology, Duke University Medical Center.

Jonathan B. Mark, Department of Anesthesiology, Duke University Medical Center, and Durham Veterans Affairs Hospital.

Matthias Kreuzer, Technical University of Munich, School of Medicine, Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care, Klinikum rechts der Isar, Germany.

References:

- 1.Chan MTV, Hedrick TL, Egan TD, et al. American Society for Enhanced Recovery and Perioperative Quality Initiative Joint Consensus Statement on the Role of Neuromonitoring in Perioperative Outcomes: Electroencephalography. Anesth Analg. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wildes TS, Mickle AM, Ben Abdallah A, et al. Effect of Electroencephalography-Guided Anesthetic Administration on Postoperative Delirium Among Older Adults Undergoing Major Surgery: The ENGAGES Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2019;321(5):473–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan MT, Cheng BC, Lee TM, Gin T, Group CT. BIS-guided anesthesia decreases postoperative delirium and cognitive decline. Journal of neurosurgical anesthesiology. 2013;25(1):33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Radtke FM, Franck M, Lendner J, Kruger S, Wernecke KD, Spies CD. Monitoring depth of anaesthesia in a randomized trial decreases the rate of postoperative delirium but not postoperative cognitive dysfunction. Br J Anaesth. 2013;110 Suppl 1:i98–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan MT, Cheng BC, Lee TM, Gin T, Group CT. BIS-guided anesthesia decreases postoperative delirium and cognitive decline. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2013;25(1):33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yeh RW, Valsdottir LR, Yeh MW, et al. Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma when jumping from aircraft: randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2018;363:k5094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shortal BP, Hickman LB, Mak-McCully RA, et al. Duration of EEG suppression does not predict recovery time or degree of cognitive impairment after general anaesthesia in human volunteers. Br J Anaesth. 2019;123(2):206–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaskell AL, Hight DF, Winders J, et al. Frontal alpha-delta EEG does not preclude volitional response during anaesthesia: prospective cohort study of the isolated forearm technique. BJA: British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2017;119(4):664–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hesse S, Kreuzer M, Hight D, et al. Association of electroencephalogram trajectories during emergence from anaesthesia with delirium in the postanaesthesia care unit: an early sign of postoperative complications. British journal of anaesthesia. 2019;122(5):622–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mashour G Personal Communication, 3/12/2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moller JT, Johannessen NW, Espersen K, et al. Randomized evaluation of pulse oximetry in 20,802 patients: II. Perioperative events and postoperative complications. Anesthesiology. 1993;78(3):445–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Avidan MS, Zhang L, Burnside BA, et al. Anesthesia awareness and the bispectral index. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(11):1097–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ni K, Cooter M, Gupta DK, et al. Paradox of age: older patients receive higher age-adjusted minimum alveolar concentration fractions of volatile anaesthetics yet display higher bispectral index values. Br J Anaesth. 2019;123(3):288–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erdogan MA, Demirbilek S, Erdil F, et al. The effects of cognitive impairment on anaesthetic requirement in the elderly. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2012;29(7):326–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jain M, Canham M, Upadhyay D, Corbridge T. Variability in interventions with pulmonary artery catheter data. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29(11):2059–2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Browndyke JN, Berger M, Smith PJ, et al. Task-related changes in degree centrality and local coherence of the posterior cingulate cortex after major cardiac surgery in older adults. Hum Brain Mapp. 2018;39(2):985–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]