Abstract

Objective:

This study considers three hypotheses regarding the impact of extended involuntary outpatient commitment orders on services utilization.

Method:

Service utilization of Victorian Psychiatric Case Register (VPCR) patients with extended (≥180 day) outpatient commitment orders was compared to that of a diagnostically-matched treatment compliant group with similarly extended (≥180 day) periods of outpatient care (N=1182)—the former receiving care during their extended episode on an involuntary basis while the latter participated in care voluntarily. Pre/post first extended episode mental health service utilization was compared via paired t tests with individuals as their own controls. Logistic and OLS regression as well as repeated measures ANOVA via the GLM SPSS program and post hoc t tests were used to evaluate between group and across time differences.

Results:

Extended episodes of care for both groups were associated with subsequent reduced use of hospitalization and increases in community treatment days. Extended orders did not promote voluntary participation in the period following their termination. Community treatment days during the extended episode for those on orders were raised to the level experienced by the treatment compliant comparison group during their extended episode and maintained at that level via subsequent renewal of orders throughout the patients’ careers. Approximately six community treatment days were required for those on orders to achieve a oneday reduction in hospital utilization following the extended episode.

Conclusion:

Outpatient commitment for those on extended orders in the Victorian context enabled a level of community-based treatment provision unexpected in the absence of this delivery system and provided an alternative to hospitalization.

Involuntary outpatient commitment provisions are explicitly written into mental health laws in Australia, the United Kingdom, New Zealand, and 42 states and the District of Columbia in the United States (Appelbaum, 2001; Preston, Kisely, & Xiao, 2002; Swartz et al., 1999, 2001; Torrey, & Kaplan, 1995). Though varying in their provisions, outpatient commitment orders require individuals (refusing care and believed potentially dangerous/gravely disabled due to a mental disorder) to accept community treatment or hospital release conditioned on treatment compliance (Allen & Smith, 2001). Such compliance may extend to requiring people to live in a particular apartment, take prescribed medications, attend counseling sessions, and abstain from substance utilization (Preston et al., 2002). Patients who do not comply with the treatment regimen in most jurisdictions may be admitted to a psychiatric hospital for involuntary care. In effect, the patient’s status becomes one of conditional discharge from a psychiatric hospital whether or not they have been in the hospital (in some jurisdictions, orders may be issued without taking the individual to the hospital). This study looks at almost a decade of experience with the use of outpatient commitment in Victoria, Australia (see: Legal Provisions in Textbox). It considers the claimed effectiveness of extended orders-outpatient commitments lasting 180 days or longer (Swartz et al., 1999, 2001; Torrey & Kaplan, 1995)-and moves beyond existing research by considering the complete patient careers of those put on orders and a matched treatment compliant comparison sample, i.e. a sample that participated voluntarily in community treatment for periods ≥180 days.

Outpatient commitment research has produced mixed results (Kisely, Campbell, & Preston, 2005; Ridgely, Petrila, & Borum, 2001; Swartz & Swanson 2004). Clinical trials in New York and North Carolina randomized small groups of patients (142 and 252 respectively) with multiple major mental disorder diagnoses (characterized as severe mental illness) at various points in their treatment careers to outpatient commitment and no outpatient commitment conditions and followed them for a year. Both studies failed to find significant differences between the randomized groups on any service utilization or behavioral outcomes in their initial reports (Policy Research Associates Final Report, 1998; Swartz et al., 1999, 2001; Steadman et al., 2001). In a secondary analysis, sacrificing the randomized component of the study, the North Carolina group found less hospital utilization among extended outpatient commitment patients (those with ≥180 days on orders during the follow-up year). A subsequent follow-up of the North Carolina group reported reduced victimization among patients placed on orders, whether or not the orders were extended (Hiday, Swartz, Swanson, Borum, & Wagner, 2002). Four other studies, without comparison samples, are often cited as evidence that outpatient commitment reduces hospital admissions and the duration of hospital stays (Fernandez & Nygard, 1990; Munetz et al., 1996; Rohland, Rohrer, & Richards, 2000; Zanni & de Veau, 1986). Appelbaum (2001), in an evaluation of the preponderance of evidence on such orders, indicates that “… the weight of the evidence and clinical experience now favor efforts to implement reasonable schemes of outpatient commitment…” (p.350). Following on the claims of the effectiveness of extended orders, advocates have come to see the extended period of such commitment as one such reasonable scheme (Torrey & Zdanowicz, 2000). Given a need to replicate such findings, and a concern about the generalizability of the North Carolina results, further investigation of outpatient commitment and particularly its most promising scheme–≥180 day extended orders-seems warranted (Torrey & Zdanowicz, 2001).

In Victoria, Australia, the public mental health system covers 4.7 million inhabitants mandating a prescribed strategy of care emphasizing the desirability of community over inpatient treatment and care in the “least restrictive environment” (Commonwealth of Australia, 1998, 1999; Mental Health Branch National Standard for Mental Health Services, 1997). Since 1986 Victoria has relied on the extensive use of outpatient commitment in their process of rapid deinstitutionalization so as to ensure participation in prescribed care by patients who most frequently are conditionally released from hospital and are believed unable to voluntarily accept needed treatment in the community. Patients placed on outpatient orders are offered aggressive and comprehensive treatment modeled on the Program In Assertive Community Treatment Model (PACT) (Commonwealth of Australia, 1999). Mental health workers are expected to be in contact with the patient with a frequency dictated by the patient’s condition and need for treatment. The objective of issuing orders appears to primarily be the facilitation of early release from care and secondarily the prevention of future hospitalization by enabling treatment contacts with the patient with a frequency the team believes is necessary to ensure compliance with prescribed treatment. Outpatient commitment can therefore be considered a successful alternative to hospitalization if it shortens episodes of hospitalization following its initiation and brings the level of service contact in the community to that indicative of compliance with prescribed treatment.

Given previous research and the Victorian treatment objectives, the following three hypotheses are evaluated herein:

Extended outpatient commitment orders in combination with community treatment will contribute to reduced inpatient utilization (Commonwealth of Australia, 1998, 1999; Mental Health Branch National Standards for Mental Health Services, 1997; Swartz et al., 1999).

Compliance post-orders will be demonstrated by increased voluntary care utilization. As outpatient commitment is a way of delivering services to a population that for one or another reason cannot or will not consistently accept such service voluntarily, the issue of compliance herein is defined as voluntary participation in care outside the hospital—i.e. care received without the accompanying legal status of being on orders. The hypothesis is that after an extended period on orders there will be an increase in the use of voluntary outpatient care. (Van Putten, Santiago, & Bergen, 1988)

Outpatient commitment will enable service contact to approximate that observed in a treatment compliant group.

1. Methods

1.1. Sample

This retrospective study compared patients with extended (≥180 day) outpatient commitment orders to a diagnostically matched treatment compliant group with similarly extended (≥180 day) periods of voluntary outpatient care in the community (N=1182). While the latter group experienced periods of involuntary hospitalization, they were not placed on orders during their mental health treatment career.

The Victorian Psychiatric Case Register (VPCR) provided a record of all clinical contacts and their character occurring within the State. With approval of their ethics committee, the Victorian Department of Human Services approved access to register data for the period 11/12/90 to 6/30/00—a period when inpatient and outpatient mental health service utilization and outpatient commitment could be reliably mapped using the VPCR. (Prior to this time only limited linkage could be made between inpatient and outpatient utilization and 6/30/00 was the last date of available data under the prevailing management information system at the time of study initiation.) Using a computer algorithm, matched samples were drawn from the study universe that included all individuals having ever experienced an outpatient commitment within the timeframe and those in the register severe enough to experience psychiatric hospitalization though never experiencing placement on orders. The initial match, based on diagnosis, gender and age (within 5 years) yielded 7826 pairs. In order to ensure adequate post-episode follow-up (2 years) pair selection was further constrained to those with mental health system end dates prior to 6/30/98. Of these pairs, 591 had both a patient with a ≥180-day order and an exact diagnostically matched comparison group member with a ≥180-day community care episode (other pairs had patients with orders of shorter duration or no matched comparison with an extended care episode). These 591 pairs (N=1182) became the evaluation sample.

While the computer algorithm matched pairs identically on the experience of a ≥180-day community care episode and diagnosis the match was not perfect on gender and age even though the computer algorithm exhausted all possibilities and yielded the “best” probabilistic match. Even random sampling does not insure fully comparable histories, it only provides the best probability of having comparable histories and group members often differ on significant variables—e.g. in both the New York and North Carolina randomized trials, between group differences obtained even after randomization (Swartz et al., 1999; Steadman et al., 2001). The appropriate response to such sampling differences is statistical adjustment. While the matching procedure employed herein reduced between group differences attributable to gender and age, these characteristics still distinguished the groups and along with other relevant patient career experiences their effects are statistically controlled in the multivariate analyses described below. Further, herein no claim is made to the level of causal inference usually accorded to a randomized trial, the attempt is to understand patient careers over the long-term and seek clues as to the possible utility of extended orders. As one of the major justifications for the use of such orders is a lack of treatment compliance, the careers of a treatment compliant comparison group are especially relevant to an assessment of the operational utility of such orders.

1.2. Units of Analysis

In documenting the treatment career experience, all treatment contacts were organized into episodes of care: each hospitalization (from day of admission to day of discharge) was considered a separate inpatient episode; each continuous period of community treatment provision without a break in service ≥90 days, a community care episode (Tansella et al., 1995). A service break ≥90 days followed by re-initiation of treatment was considered the start of a new community care episode. All occasions of community treatment are reported as community treatment days; multiple occasions of community treatment on the same day count as one community treatment day. In order to facilitate reading and understanding of the analyses a glossary of terms is provided at the end of this manuscript.

The legal conditions under which treatment contacts occurred are considered. Statistics are separately reported for voluntary, involuntary, and combined total service utilization. Thus, for example a voluntary community treatment day is a day when a patient received at least one occasion of community treatment and was not on an involuntary order. Similarly, an involuntary community treatment day involved the delivery of community-based service while the patient was on an outpatient order or involuntarily hospitalized. Comparisons are based on yearly numbers of inpatient hospitalizations, hospital days, and/or community treatment days, thus adjusting for the period that the patient is at known risk for hospitalization or community service. A patient’s career risk period is the date of first mental health system contact to 90 days following the last system contact. If a patient left the area or died, this information can only be known by a 90-day lapse in contact. Risk prior to the extended episode is measured from the patient’s first date of system contact to the start date of the extended episode. Rates per year never reflect more treatment experiences than the patient actually had.

Finally, as a patient may have had more than one ≥180-day episode, all pre/post comparisons and analyses refer to the first such episode. The pre-episode period, the period before the start of the first ≥180-day episode, begins with the patient’s first contact with the mental health system and extends through the date of the initiation of their first extended episode. The period during the first ≥180-day episode refers to the patient activities occurring from the date of the episode initiation to the termination of the episode, a period of at least 180 days duration. The after or post-episode period, by design a minimum of 2 years, refers to all mental health system involvement following the termination of the extended episode, a termination that either occurred with a re-hospitalization or a ≥90-day break in service.

1.3. Analyses (Employing the SPSS Statistical Package 13 (SPSS for Windows, 2006))

Hypothesis 1.

Extended outpatient commitment orders in combination with community treatment will contribute to reduced inpatient utilization.

This complex hypothesis is addressed with two analytic efforts. First, using paired t tests patients were considered within groups as their own comparisons. The number of inpatient and community treatment days before the start of the ≥180-day episode was compared to the number after the episodes’ end. It was hypothesized that the “before” experience would be significantly altered in the post-episode period in the form of fewer inpatient days due to shorter hospital stays and an increase in the number of community treatment days (Mental Health Branch National Standards for Mental Health Services, 1997).

Second, multivariate analyses of covariance via dummy variable regression were used to evaluate the independent effects on hospital utilization of the extended order, the receipt of community treatment days, and the interaction of these two factors after taking account of clinical, demographic, social, and mental health treatment career characteristics. Specifically, Logistic and OLS Multiple Regressions were completed, respectively addressing whether or not the patient was hospitalized in the post-period and how many inpatient days per year they experienced. The regressions included the two main effects and their interaction, and covariate controls for demographics (age, gender, never married, and “under 65 and living on pension”, previously demonstrated independent influences on hospital utilization), inpatient utilization per year prior to the ≥180-day episode, as a severity adjustment (Schinnar, Rothbard, & Kanter, 1991); and exposure controls (≥180-day episode duration, and the duration of the follow-up period).

Hypothesis 2.

Compliance post-orders will be demonstrated by increased voluntary care utilization. The hypothesis is that after an extended period on orders there will be an increase in the use of voluntary outpatient care. This hypothesis was evaluated with the use of paired t tests.

Hypothesis 3.

Outpatient commitment will enable service contact to approximate that observed in a treatment compliant group. In making between group and across time comparisons the GLM program is used to consider overall differences in utilization of community treatment services and to address two post hoc comparisons: community treatment utilization differences between groups during the extended episode and during vs. post-episode for the group on orders.

2. Results

Sample demographics are shown in Table 1. The sample’s ICD-9CM primary diagnoses are: schizophrenia (N=1050, 88.8%), major affective disorder (N=60, 5.1%), and other conditions (N=72, 6.1%). While, no statistical differences were found in the duration of the follow-up periods for the two groups, the time of their involvement with the system prior to their initial extended episode, the duration of that episode, their career hospitalizations, and the number of community treatment days experienced prior to each of their admissions, did differ. The first finding allows us to make post-period between group comparisons with greater confidence regarding intervention exposure effect comparability; the latter differences are taken into account in the statistical models and by making comparisons based on yearly utilization. Further, the treatment compliant status of the comparison group seems to be validated in that this group voluntarily participated in community treatment for an average period of 492 days. While it is difficult to define treatment compliance, such participation among those meeting hospitalization criteria seems a reasonable test.

Table 1.

Demographics and design relevant patient career statistics

| Characteristic | Comparison | Outpatient commitment | Total sample | Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%)/M±SD | N (%)/M±SD | N (%)/M±SD | t, df, p/Chi Sq, df, p | |

| Total sample | 591 (50%) | 591 (50%) | 1182 (100%) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 415 (70.2%) | 350 (59.2%) | 765 (64.7%) | Chi Sq= 15.66, df=1, p<.001 |

| Female | 176 (29.8%) | 241 (40.8%) | 417 (35.3%) | |

| Age at first date | 26.59 (11.10) | 34.01 (16.01) | 30.31 (14.26) | t=−9.50, df= 590, p< .001 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Divorced | 32 (5.4%) | 49 (8.3%) | 81 (6.9%) | Chi Sq=42.87, df=6, p<.001 |

| Defacto cohabiting partner | 28 (4.7%) | 27 (4.6%) | 55 (4.7%) | |

| Married (legally) | 60 (10.2%) | 73 (12.4%) | 133 (11.3%) | |

| Never married | 422 (71.4%) | 339 (57.4%) | 761 (64.4%) | |

| Separated | 33 (5.6%) | 59 (10.0%) | 92 (7.8%) | |

| Widowed | 5 (0.8%) | 34 (5.8%) | 39 (3.3%) | |

| Unknown | 11 (1.9%) | 10 (1.7%) | 21 (1.8%) | |

| Duration of 180+ day episode (in days) | 492±382 | 391±214 | 442±314 | t=5.56, df=590,p<.001 |

| Duration of follow-up period (in days) | 904±742 | 841 ±667 | 870±709 | t=−1.57, df= 590, p=.115 |

| Days from 1st system contact to 180+ day episode | 374±526 | 685±612 | 530±591 | t=−9.81, df= 590, p< .001 |

| Number of community treatment days prior to admission* | 2.52± 1.94 | 4.36±3.51 | 3.37±2.7 | t=−12.10, df=460, p < .001 |

| Number of inpatient admissions | 3.04±2.3 | 5.26±4.1 | 4.15 ±3.5 | t=−15.27, df=590,p<.001 |

Number of community treatment days preceding inpatient admission.

Findings indicate a reduced use of hospital and an increase in community treatment. Table 2 shows that patients on orders were hospitalized on average 56.4±82.5 days per year before the extended episode and only 19.6±40.4 days per year after. Their number of community treatment days increased from 27.5 days per year to 41.1 days per year in the respective periods. The comparison sample was hospitalized on average 37.2 days per year before and only 10.4 days per year after. Their number of community treatment days increased from 13.3 days per year to 18.8 days per year. The differences are significant at p<.001 (see, Table 2).

Table 2.

Service utilization before, during, and after 180+ day episode (N=1182)*

| Service type | Outpatient commitment group (N=591) | Comparison group (N=591)+ | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before start | During | After end | Before start | During | After end | |||||||

| Hospitalization | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| Inpatient days | ||||||||||||

| Involuntary | 47.3 | 55.4 | NA | NA | 17.0 | 32.0 | 25.8 | 33.0 | NA | NA | 5.9 | 14.4 |

| Voluntary | 9.1 | 27.1 | NA | NA | 2.6 | 8.4 | 11.4 | 25.6 | NA | NA | 4.5 | 18.1 |

| Total | 56.4 | 82.5 | NA | NA | 19.6 | 40.4 | 37.2 | 58.6 | NA | NA | 10.4 | 32.5 |

| Number of admissions | ||||||||||||

| Involuntary | 1.3 | 0.9 | NA | NA | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.7 | NA | NA | 0.4 | 0.7 |

| Voluntary | 0.3 | 0.6 | NA | NA | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.8 | NA | NA | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Total | 1.7 | 1.5 | NA | NA | 0.7 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.5 | NA | NA | 0.7 | 1.2 |

| Average length of stay in days | ||||||||||||

| Involuntary | 24.0 | 34.6 | NA | NA | 7.0 | 14.1 | 19.4 | 24.5 | NA | NA | 4.3 | 10.5 |

| Voluntary | 5.9 | 22.6 | NA | NA | 1.8 | 7.0 | 7.3 | 15.7 | NA | NA | 2.6 | 13.4 |

| Community treatment days | ||||||||||||

| Voluntary | 18.3 | 22.2 | 0.2 | 3.8 | 19.9 | 26.5 | 11.7 | 17.4 | 41.8 | 24.7 | 18.1 | 22.3 |

| Involuntary+ | 9.2 | 17.9 | 42.3 | 32.7 | 21.2 | 34.4 | 1.5 | 2.9 | .5 | 4.1 | 0.7 | 2.4 |

| Totals | 27.5 | 40.2 | 42.8 | 32.3 | 41.1 | 61.0 | 13.3 | 20.2 | 42.0 | 24.6 | 18.8 | 24.7 |

Expressed as mean average units per year capped at the maximum number of service units the individual received. Differences between the before and after periods are all significant, p<.001, df=591, with the exception of the observed differences in voluntary community treatment days between baseline and each after comparison period—the latter increases were not significant.

The few involuntary community treatment days of the comparison group reflect involvement of community-based staff during an involuntary hospitalization to ensure continuity of care.

Compliance post-orders was not demonstrated by increased voluntary community treatment day utilization. The only difference in pre/post-utilization failing to reach significance in Table 2 was the use of voluntary community treatment days among those patients on orders. For this group the increases were primarily in the involuntary community treatment day category. For the comparison group community treatment day increases were all in the voluntary category. (The few involuntary community contacts for the latter group reflect involvement of community-based staff during an involuntary hospitalization to ensure continuity of care; such involvements decreased across the periods due to actual reductions in involuntary hospitalizations.)

The combination of outpatient commitment (being on an extended order) and its accompanying community treatment contributed to reduced inpatient utilization. Table 3 shows the results of the Logistic and OLS regressions predicting respectively post-period hospitalization, and post-period utilization of inpatient days. The logistic model predicting post-period hospitalization is significant (Chi Sq. 425.70, df 12 p<.001) and demonstrates that when all factors are taken into account each day of community treatment on orders decreases the chance of hospitalization in the post-period for the outpatient commitment group by 3.2% over those in the comparison group. The OLS model predicting inpatient days per year is significant (Adj. R2 =.10, F=11.02, df=12,1077, p<.001). It also shows a significant outpatient commitment group by community treatment day interaction (b=−.16, SE=.06, p<.004) such that for the outpatient commitment group (with all other covariates and demographics controlled) one community treatment day on orders is associated with a .16 reduction in inpatient days per year during the period after the end of the extended ≥180-day episode; alternatively six community treatment days on orders would equal a one (.96) day reduction in inpatient utilization.

Table 3.

Hospitalization and inpatient days post period following 180+ day community episode

| Unstandardized coefficients | S.E. | P value | Exp. (B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Sig. | |||

| A. Hospitalization in the post-period logistic regression model* | ||||

| Predictor variables in the equation** | ||||

| •GROUP=outpatient commitment v comparison | .70 | .29 | .016 | 2.00 |

| •Community treatment days per year after the start of the 180+ day episode | .04 | .01 | .001 | 1.04 |

| •Interaction: outpatient commitment group by community treatment days after the start of the 180+ day episode | −.03 | .01 | .001 | 0.97 |

| Unstandardized coefficients | S.E. | Standardized coefficients | t | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. Inpatient days per year in the post-period OLS regression model^ | B | Beta | |||

| Variables in the equation** | |||||

| •Group: (outpatient commitment= 1, comparison=0) | 8.41 | 2.91 | .15 | 2.891 | .004 |

| •Community treatment days per year after the start of the 180+ day episode | .22 | .05 | .52 | 4.096 | .001 |

| •Interaction of outpatient commitment group by community treatment days after the start of 180+ day episode | −.16 | .06 | −.42 | −2.860 | .004 |

Dependent variable: hospitalized in the post period; (Chi Sq. 425.707, df 12, p<.001).

Predictor variables in the equation: group, interaction of group by treatment days after the start of the 180+ day episode, age, gender, never married, pension income, follow-up period duration, 180+ period duration, inpatient days per year prior to the 180+ day episode, treatment days following the start of the 180+ day episode. Only the main group and service effects, and the interaction effect are shown.

Dependent variable: total inpatient days per year after the end of the 180+ day episode; R=.331, R2=.109, Adj. R2=.099, F=11.02; df=12, 1077; p<.001.

Predictor variables in the equation: group, interaction of group by treatment days after the start of the 180+ day episode, age, gender, never married, pension income, follow-up period duration, 180+ day episode period duration, inpatient days per year prior to the 180+ day episode, treatment days following the start of the 180+ day episode, schizophrenia, major affective disorder. Only the main group and services effects, and the interaction effect are shown.

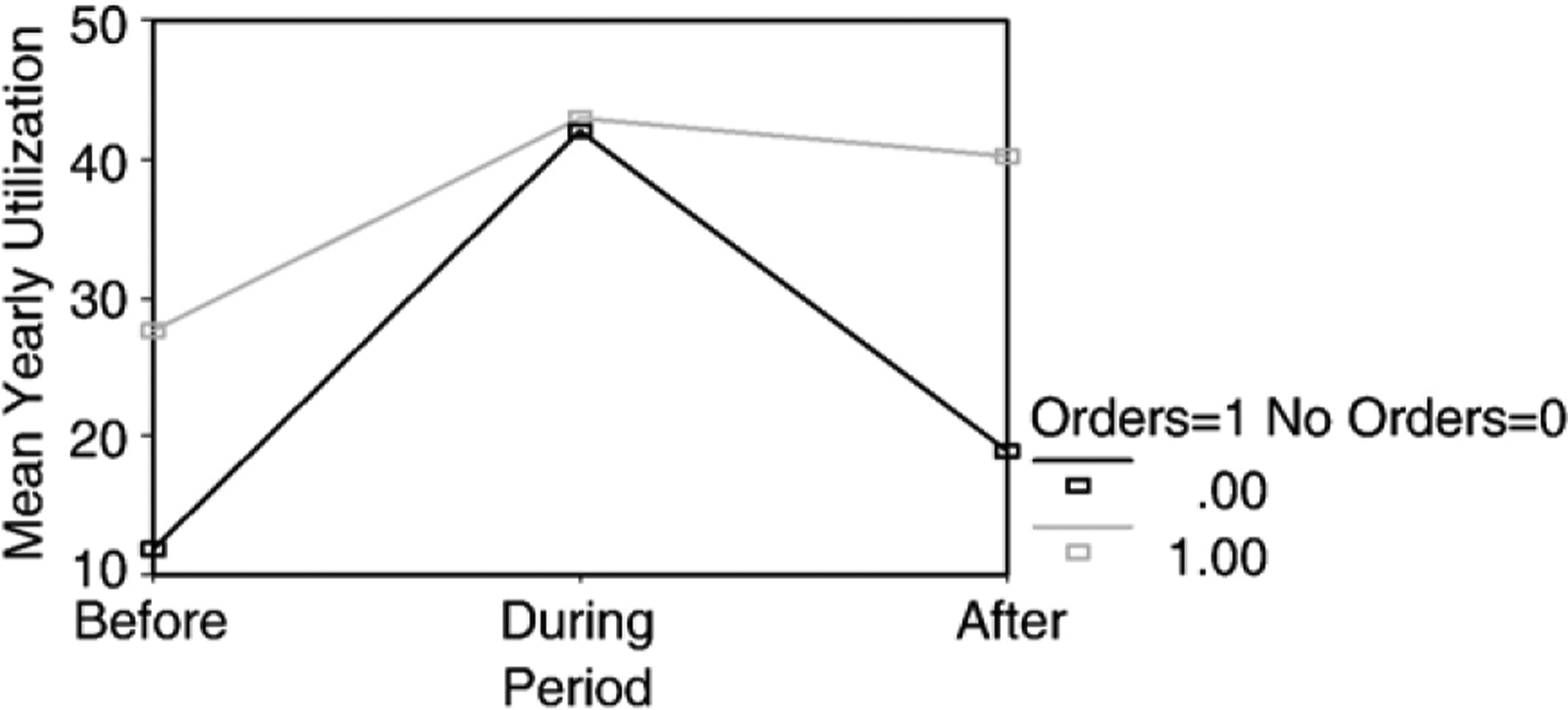

Outpatient commitment enabled the level of community treatment day provision to approximate that observed in the treatment compliant group. The groups differed in their community treatment day utilization across the three points in time (F=106.51, p<.001) as did the subjects within groups (F=297.22, p<.001). Of most importance, however, is the absence of significant differences between groups in their yearly community treatment day utilization during the extended episode and between the episode and post episode periods for the group on orders (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Yearly service utilization before during and after episode.

3. Discussion

Comparisons of the pre/post-extended community care episode utilization experiences of both groups show reduced use of hospitalization, more than a month per year per patient, and dramatic increases in community treatment day utilization, approximately a third more treatment utilization than in the pre-period. This is however only a partial support of the first hypothesis since proportionally the reductions and increases are similar for both groups and might be attributed to deinstitutionalization policy in Victoria or simple regression to the mean. Most important, however, with respect to evaluating the utility of extended outpatient commitment, is that the equivalent proportional increase in community treatment days for the group on orders, and perhaps the proportional reduction in hospitalization, only arises because of the existence of the outpatient order.

As noted above, outpatient commitment is a way of delivering services to a population that for one or another reason cannot or will not consistently accept such service voluntarily. Findings indicate that the emphasis should be on the fact that they do not consistently accept community treatment voluntarily. The group on orders clearly demonstrated a willingness to voluntarily participate in community treatment in the pre and post-period (18.3 and 19.9 days per year respectively) but apparently, at least in the opinion of mental health practitioners, not to the extent needed—thus the extra community treatment delivered under orders. It would appear that the role of the outpatient commitment during the extended episode was to raise the level of outpatient service to that provided to the treatment compliant comparison sample in their time of need (see Fig 1). No difference was observed in the total amount of community services used by both groups during the extended episode —the comparison group received them voluntarily, the committed group under orders. In reducing involuntary hospitalization and increasing involuntary community treatment days, extended orders from their initiation represented a change in the way of packaging services for a patient and the process was continued via order renewals following the initial episode’s end throughout the patient’s career. Long-term service participation under orders did not presage a shift to consistent voluntary participation in community treatment, at least to a level deemed necessary by mental health practitioners. Renewals of orders were used to keep the number of days per year received in the post period at the same level received in the extended episode period.

Outpatient commitment provided an alternative to hospitalization during the extended ≥180-day episode when no hospitalization occurred as well as in the post-period. In the post-period regression analyses demonstrated that it was the combination of community treatment days enabled by outpatient commitment that facilitated the reduction of hospital utilization in the population on extended orders. In the outpatient commitment group this resulted in the substitution of approximately six outpatient community treatment days for each reduced inpatient day per year in the period after the end of the extended episode. Given that most people in Victoria are primarily placed on orders as a conditional release from an inpatient episode, the mechanism supporting the reduced hospitalization in the post period may be one where the successful establishment of a treatment interaction with the patient on orders over their extended ≥180 episode allowed personnel to consider early release from subsequent hospitalizations to new orders in the post-period.

Outpatient commitment is perhaps best conceived as a delivery mechanism rather than a treatment in and of itself. It is probably only as good as the treatment that accompanies it. Given that the alternative to hospitalization effect is accomplished through the renewal of orders in the follow-up period, it is difficult for many to identify the involuntary commitment as a success. Yet, the patients on extended orders are complex cases, with higher service utilization both prior and following the extended episode than the treatment compliant comparison group. Their treatment needs outside of the extended episode were probably more extensive than the treatment compliant matched controls at the outset. Witness that prior to hospitalization the number of community treatment days associated with the events precipitating admission and needed for the patients on orders is almost twice that of the comparison group (see Table 2). Further, neither extended outpatient commitment alone nor community treatment days alone accounted for the reduced inpatient day use effect in the post-period, quite the opposite. Both are associated with increased inpatient utilization because such services are initiated around the crises preceding an inpatient care episode or accompany the transition from hospital back to community.

Our findings speak only to the use of extended ≥180-day episodes of care in combination with community services offered in Victoria Australia. They do not address demonstrable psychosocial outcomes experienced by individuals participating in such treatment regimens. They also apply to a group made up largely of people with schizophrenia, though this is the diagnosis of most individuals placed on orders in the Victorian system and given that the sample was drawn with a computer driven algorithm from the universe of patients it may be indicative of the character of the group who are more likely to require and adapt to voluntary or involuntary extended episodes of care. The results and conclusions reported herein might be considered stronger from an evidence standpoint had they been derived from comparisons of randomly assigned groups, yet the randomized clinical trial vehicle would not have offered a decade’s representation of a population’s real world experience. A matched comparison design was used with patients acting as their own controls in the within and between group analyses. Moreover, though the findings apply only to the Australian context, it is notable that outpatient commitment has become a major issue in western psychiatry and this study represents a report on the most extensive experience with its utilization.

This paper offers some new perspectives on outpatient commitment: It considers outpatient commitment as a delivery system. It focuses on the interaction of outpatient commitment with treatment in the reduction of inpatient utilization. In conclusion, outpatient commitment for those on extended orders in Victoria, Australia enables a level of community-based treatment provision unexpected in the absence of this delivery system that provides an alternative to hospitalization.

Glossary of Terms

- Compliance post orders

Voluntary service utilization following the termination of the patient’s first extended outpatient commitment episode.

- Community care episode

A continuous period of time during which patients had mental health service contacts of varying frequency but never without a break in service contact ≥90 days or the initiation of inpatient care.

- Community treatment day

A day in the course of a community care episode where the patient received one or more mental health service contacts. Extended episode: A community care episode ≥180 days.

- Extended episode period

The period during the first ≥180-day episode refers to the patient activities occurring from the date of the episode initiation to the termination of the episode, a period of at least 180 days duration.

- Involuntary care participation

Service received during a community care episode while on an involuntary outpatient commitment order or as an inpatient on an involuntary inpatient commitment.

- Post-period

The after or post episode period, by design a minimum of two years, refers to all mental health system involvement following the termination of the first extended episode, a termination that either occurred with a re-hospitalization or a ≥90-day break in service. It covers the day after the termination to 90 days following the last known system contact.

- Post-episode care

Service utilization following the termination of the patient’s first extended episode.

- Pre-period

The pre-episode period, the period before the start of the first ≥180-day episode, begins with the patient’s first contact with the mental health system and extends through the date of the initiation of their first extended episode.

- Pre-episode care

Service utilization prior to the initiation of the patient’s first extended episode of care.

- Treatment compliant group

The comparison group who at least at one point in their treatment career voluntarily participated in community care for a continuous period ≥180 days without a break in service ≥90 days or the initiation of inpatient care—i.e. had at least one voluntary extended episode.

- Voluntary community-care participation

Service received during a community care episode without the use of outpatient commitment orders.

- Within-episode care

Community treatment days during the patient’s first extended episode.

Appendix A

Victoria’s Outpatient Commitment: Community Treatment Orders+

Outpatient commitment orders require individuals to accept outpatient treatment or hospital release conditioned on treatment compliance.

Victoria’s Eligibility Criteria: All of the following must obtain,

the person appears to be mentally ill; and,

their illness requires immediate treatment that can be obtained…

for health or safety (whether to prevent a deterioration in physical or mental condition or otherwise) or for community protection; and,

the person has refused treatment or is unable to consent to necessary treatment; and,

no less restrictive option is available.

How is outpatient commitment implemented in Victoria?

An authorised psychiatrist makes the Order (s.14 (1)) and the authorised psychiatrist or their delegate must monitor the treatment (s.14 (2)(a)).

Patients may be placed on orders following hospital discharge or directly from the community.

The Order can be extended indefinitely (s.14 (7)).

The Order can be revoked by an authorised psychiatrist for non-compliance (s.14 (4)(b)).

Patients whose treatment orders are revoked may be apprehended by the police and taken to an inpatient facility(s.14 (4A)).

Entry to hospital occurs with somewhat less involved procedural safeguards than that of a direct admission. It is in effect a return from conditional leave.

Patient obligations?

Compliance with the order extends to requiring people to live in a particular apartment, take prescribed medications, and attend counseling sessions.

What type of oversight is required?

Mental Health Review Board hearing within 8 weeks.

Mental Health Review Board review within 12 months.

Review hearing on request by Mental Health Review Board (psychiatrist, attorney, mental health board staffers).

+ Victorian Legislation and Parliamentary Documents, Version No. 080

Mental Health Act 1986, Act No. 59/1986 Version incorporating 2004 amendments taking effect on 6 December 2004 http://www.health.vic.gov.au/mentalhealth/mh-act/index.htm and click “Legislation” or http://www.dms.dpc.vic.gov.au/.

References

- Allen M, & Smith VF (2001). Opening Pandora’s Box: The practical and legal dangers of involuntary outpatient commitment. Psychiatric Services, 52(3), 342–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum P (2001). Thinking carefully about outpatient commitment. Psychiatric Services, 52(3), 347–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth of Australia: National mental health report 1996. (1998).Canberra, ACT: Commonwealth Department of Health and Family Services.

- Commonwealth of Australia: National mental health report 1997. (1999).Canberra, ACT: Commonwealth Department of Health and Family Services.

- Fernandez GA, & Nygard S (1990). Impact of involuntary outpatient commitment on the revolving door syndrome in North Carolina. Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 41, 1001–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiday VA, Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Borum R, & Wagner HR (2002). Impact of outpatient commitment on victimization of people with severe mental illness. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159, 1403–1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisely S, Campbell LA, & Preston N (2005). Compulsory community and involuntary outpatient treatment for people with severe mental disorders. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews(3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mental health branch national standards for mental health services. (1997).Canberra, ACT: Commonwealth Department of Health and FamilyServices.

- Munetz MR, Grande T, Kleist J, & Peterson GA (1996). The effectiveness of outpatient civil commitment. Psychiatric Services, 47,1251–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Policy Research Associates Final Report: Research Study of the New York City Involuntary Outpatient Commitment Pilot Program, (at BellevueHospital: ). Policy Research Associates, (www.prainc.com/IOPT/opttoc.ht) 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Preston NJ, Kisely S, & Xiao J (2002). Assessing the outcome of compulsory psychiatric treatment in the community: Epidemiological study inWestern Australia. British Journal of Medicine, 524, 1244–1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridgely MS, Petrila J, & Borum R (2001). The Effectiveness of Involuntary Outpatient Treatment: Empirical Evidence and the Experience of Eight States. Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND. [Google Scholar]

- Rohland B, Rohrer JE, & Richards CC (2000). The long-term effect of outpatient commitment on service use. Administration and Policy inMental Health, 27(6), 383–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinnar AP, Rothbard AB, & Kanter R (1991). Adding state counts of the severely and persistently mentally ill. Administration and Policy inMental Health, 19(1), 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- SPSS for Windows, Release 13, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Steadman HJ, Gounts K, Dennis D, Hopper K, Roche B, Swartz M, et al. (2001). Assessing the New York City Involuntary Outpatient Commitment Pilot Program. Psychiatric Services, 52(3), 330–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Wagner HR, Burns BJ, Hiday VA, & Borum R (1999). Can involuntary commitment reduce hospital recidivism: Findings from a randomized trial with severely mentally ill individuals. American Journal of Psychiatry, 12, 1968–1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Hiday VA, Wagner HR, Burns BJ, & Borum R (2001). A randomized controlled trial of outpatient civil commitment in North Carolina. Psychiatric Services, 52(3), 325–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz MS, & Swanson JW (2004). Involuntary outpatient commitment, community treatment orders, and assisted outpatient treatment: What’s in the Data? Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 49, 585–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tansella M, Micciolo R, Biggeri A, Bisoffi G, & Balestrieri M (1995). Episodes of care for first-ever psychiatric patients: A long-term case-register evaluation in a mainly urban area. British Journal of Psychiatry, 167, 220–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrey EF, & Kaplan RJ (1995). A national survey of the use of outpatient commitment. Psychiatric Services, 46, 778–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrey EF, & Zdanowicz MT (2000). Study shows that long-term assisted treatment reduces violence and hospital utilization. Catalyst, 2(3),1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Torrey EF, & Zdanowicz MT (2001). Outpatient commitment: What, why, and for whom. Psychiatric Services, 52(3), 337–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Putten DA, Santiago JP, & Bergen MR (1988). Involuntary commitment in Arizona: A retrospective study. Hospital and CommunityPsychiatry, 39, 205–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanni G, & deVeau L (1986). Inpatient stays before and after outpatient commitment in Washington, D.C. Hospital and Community Psychiatry,37, 941–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]