Abstract

Tempranillo is a grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) variety extensively used for world wine production which is expected to be affected by environmental parameters modified by ongoing global climate changes, i.e., increases in average air temperature and rise of atmospheric CO2 levels. Apart from determining their effects on grape development and biochemical characteristics, this paper considers the intravarietal diversity of the cultivar Tempranillo as a tool to develop future adaptive strategies to face the impact of climate change on grapevine. Fruit-bearing cuttings of five clones (RJ43, CL306, T3, VN31, and 1084) were grown in temperature gradient greenhouses (TGGs), from fruit set to maturity, under two temperature regimes (ambient temperature vs. ambient temperature plus 4°C) and two CO2 levels (ambient, ca. 400 ppm, vs. elevated, 700 ppm). Treatments were applied separately or in combination. The analyses carried out included berry phenological development, the evolution in the concentration of must compounds (organic acids, sugars, and amino acids), and total skin anthocyanins. Elevated temperature hastened berry ripening, sugar accumulation, and malic acid breakdown, especially when combined with high CO2. Climate change conditions reduced the amino acid content 2 weeks after mid-veraison and seemed to delay amino acidic maturity. Elevated CO2 reduced the decoupling effect of temperature on the anthocyanin to sugar ratio. The impact of these factors, taken individually or combined, was dependent on the clone analyzed, thus indicating certain intravarietal variability in the response of Tempranillo to these climate change-related factors.

Keywords: climate change, grapevine (Vitis vinifera), genetic variability, sugars, malic acid, amino acids, anthocyanins

Introduction

Grapevine is one of the most prominent crops in agriculture given the cultural and economic importance of grape and wine production. Among the grape varieties cultivated worldwide, Tempranillo ranked #3 in 2017 with 231,000 ha, behind Cabernet Sauvignon and Kyoho (OIV, 2017), and it is one of the most important red grape varieties grown in Spain. This cultivar is characterized by subtle aroma, producing wines with fruity and spicy flavors, low acidity, and low tannins. However, wine organoleptic characteristics are highly determined by the characteristics of the grapes used for its production. Therefore, changes in grapevine growing conditions that affect berry composition are also likely to impact the wine produced. Grape quality is a complex trait that mainly refers to berry composition, including sugars, organic acids (malic and tartaric acid), amino acids, and a wide range of secondary metabolites such as phenolic compounds, aromas, and aroma precursors (Conde et al., 2007). Among the factors that affect berry content at harvest, climate parameters, and notably temperature, play a prominent role.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has pointed out the ineluctable increase in the temperature worldwide and has identified climate change as an important threat to global food supply. Indeed, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions have increased greatly during the last decades, affecting the equilibrium of biogeochemical cycles and, hence, the composition of the atmosphere (IPCC, 2013). Some of the consequences of the rise in the atmospheric concentration of GHG are at global climate level, as high levels of GHG block heat loss of the planet, thus contributing to the so-called “greenhouse effect” and to global warming. Another effect of the anthropogenic GHG emissions is the increase in the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere (IPCC, 2014). The IPCC has carried out different reports from scientific knowledges on climate change to determine the magnitude of these changes according to different scenarios. Some of the predictions for global mean temperature in 2100 show an increment between 2.2 ± 0.5 and 3.7 ± 0.7°C, and the estimations for future atmospheric CO2 concentration are between 669.7 and 935.9 ppm (scenarios RCP 6.0 and RCP 8.5 of the IPCC) (IPCC, 2013).

Research on the response of grapevine to the abovementioned environmental factors has concluded that high temperature affects the phenology of grapevine, as well as grape berry development and ripening, hastening the latter (Jones and Davis, 2000; Duchêne and Schneider, 2005; Webb et al., 2007; Keller, 2010; Martínez-Lüscher et al., 2016a) and affecting both primary and secondary metabolisms. Berry sugar accumulation is altered under climate change conditions (Duchêne and Schneider, 2005; Kuhn et al., 2014), while malic acid degradation is enhanced by high temperatures (Orduña, 2010; Carbonell-Bejerano et al., 2013), and by its combination with elevated CO2 (Salazar Parra et al., 2010; Martínez-Lüscher et al., 2016b). Secondary metabolism is also sensitive to high temperatures, particularly the flavonoid and aroma precursor pathways, as evidenced by transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic approaches (Spayd et al., 2002; Tarara et al., 2008; Azuma et al., 2012; Rienth et al., 2014; Martínez-Lüscher et al., 2016a; Lecourieux et al., 2017, 2020; Arrizabalaga et al., 2018), thus affecting the balance of berry quality-related compounds at ripeness (Sadras and Moran, 2012; Kuhn et al., 2014). Whereas increased temperature has been consistently shown to reduce anthocyanin levels (Spayd et al., 2002; Mori et al., 2007; Tarara et al., 2008; Azuma et al., 2012), the effect of CO2 on these compounds is more controversial, with some authors reporting no effect (Gonçalves et al., 2009), while others reported an increase in anthocyanin levels (Kizildeniz et al., 2015). Finally, the decoupling in the accumulation of anthocyanins and sugars, thus leading to an imbalance between these two compounds at maturity, has been also described as a consequence of elevated temperature (Sadras and Moran, 2012; Kuhn et al., 2014).

The studies on the impact of multiple stress factors associated with climate change on grape development and composition remain limited due to their complexity. However, in the future, plants will be exposed to multiple elements of environmental change simultaneously, their combined effects being not always additive. Indeed, the impact of an increase in atmospheric CO2 concentration on plant carbon metabolism, notably on photosynthesis and respiration processes, has been previously reported (Dusenge et al., 2019). Zhao et al. (2019) also demonstrated that photosynthesis of in vitro grape plantlet was promoted by elevated CO2 concentration. These modifications may directly affect primary and secondary plant metabolism, thus leading to substantial changes in fruit composition. However, Dusenge et al. (2019) showed that some effects of increased CO2 concentration on carbon plant metabolism could be minimized by elevated temperatures and highlighted the interest to study these climatic parameters together, both separately and in combination.

Regarding grapevine, previous studies on the effect of elevated CO2 and elevated temperature indicated that the combination of these two factors can affect plant phenology, thus hastening grape ripening (Salazar-Parra, 2011; Martínez-Lüscher et al., 2016b) and decreasing malic acid concentration (Leibar et al., 2016). Nevertheless, the authors reported also a decrease in grape total anthocyanin concentration at maturity. Therefore, in order to avoid detrimental wine traits, it is important to determine how grape characteristics will be affected by the abovementioned climate change-related factors, acting not only individually but also combined, and to investigate approaches to mitigate the undesired effects, ensuring the sustainability of this crop. Among the strategies proposed to adapt viticulture to a changing environment, the genetic improvement and adaptation of elite and autochthonous varieties are very relevant to keep their intrinsic varietal values and typicity (Cunha et al., 2009; Keller, 2010; Carbonell-Bejerano et al., 2019). Accordingly, the selection of grapevine varieties and clones within the same variety with longer ripening periods has been suggested as a valuable tool to exploit in order to find accessions keeping current traits under future climate conditions (Duchêne et al., 2010).

Certain varieties used for wine production are tightly linked to specific production areas. This is the case of Tempranillo in Spain, Merlot in France, Sangiovese in Italy, or Fernão Pires in Portugal (Sefc et al., 2003). Tempranillo requires warm, sunny days to reach full maturity but also cool nights to keep its natural acidity. Maturity occurs fairly early in comparison with Grenache, the variety commonly blended with Tempranillo. Nevertheless, the constant increase in temperature and CO2 levels in the future could significantly shift the optimal maturation conditions in these areas, which would have a significant effect on berry quality. For these reasons, successfully exploiting the intravarietal diversity has the potential to face with the putative negative impacts of climate change, as it would allow to keep the culture of traditional varieties. The research done so far in Tempranillo includes the identification and characterization of a large number of clones (49 certified clones), which differ either in reproductive or vegetative traits (Ibáñez et al., 2015), making possible the research of clones better adapted to future climate conditions.

In previous studies, we have reported that Tempranillo clones differ in their response to elevated temperature in terms of sugar and anthocyanin accumulation (Arrizabalaga et al., 2018). We have also demonstrated that Tempranillo clones presented differences in their phenological development, notably in terms of vegetative production and carbon partitioning into organs, in response to elevated CO2 and increased temperature (Arrizabalaga-Arriazu et al., 2020). However, plants showed signs of photosynthetic acclimation to CO2, especially when they were exposed to elevated CO2 combined with high temperature conditions, joining the idea that effects of increasing CO2 concentration on plant carbon metabolism may be modulated by elevated temperatures as mentioned above. In this context, the objective of this work was to study the effects of increased temperature and rise in atmospheric CO2, alone or in combination, on berry development and composition of five different clones of Vitis vinifera cv. Tempranillo exhibiting different lengths of their reproductive cycle. The study was focused on the evolution of must composition (malic acid, sugars, and amino acids) and skin total anthocyanins throughout the ripening period, aiming to assess whether the impact of temperature and CO2 differs among different clones of Tempranillo. We hypothesized that clones within the same variety that show differences in phenological development may respond in a different manner to the abovementioned climate change-related factors, in terms of grape composition. Indeed, grape composition could be less affected by future climatic conditions in clones with longer reproductive cycle than in early ripening clones, since in the former the ripening would take place under cooler conditions. Few studies have assessed the performance of different clones of the same cultivar to climate conditions foreseen by the end of this century. The novelty of this work is the assessment of three-way interactions among Tempranillo clones, elevated temperature, and high atmospheric CO2. The information obtained can be useful to evaluate whether genetic diversity can be an appropriate tool to design adaption strategies for viticulture in the future.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material: Origin and Development

Dormant cuttings of five clones of grapevine (V. vinifera L.) cv. Tempranillo were obtained from the germplasm bank of three institutions: RJ43, CL306 (both clones widely cultivated in Spain), and T3 were obtained from Estación de Viticultura y Enología de Navarra (EVENA), located in Olite, Navarra (Spain); 1084 was obtained from the Institute of Sciences of Vine and Wine, located in “La Grajera,” La Rioja (Spain); and VN31 was facilitated by Vitis Navarra, located in Larraga, Navarra (Spain). The reproductive cycle length of these clones had been characterized previously, presenting differences among them: VN31 and 1084 have been described as long reproductive cycle accessions (Arrizabalaga et al., 2018; Vitis Navarra, 2019), CL306 and T3 have been defined as short cycle accessions (Rubio and Yuste, 2005; Vicente Castro, 2012; Cibriáin et al., 2018), and RJ43 is considered to have an intermediate reproductive cycle length (EVENA, 2009).

Fruit-bearing cuttings were obtained as described in Arrizabalaga et al. (2018) with minor modifications. They were manipulated to develop a single berry bunch and they were grown at the same conditions as described in Arrizabalaga et al. (2018) from March to May 2016, when the fruit set took place. Then, plants were transferred to 13 L pots with 2:1 peat:perlite mixture (v/v) and moved afterward to temperature gradient greenhouses (TGGs) located at the campus of the University of Navarra (42°48′N, 1°40′W; Pamplona, Navarra, Spain). The irrigation, both before fruit set and in the TGGs, was carried out using the nutritive solution described by Ollat et al. (1998).

Treatments and Plant Growth in Temperature Gradient Greenhouses

Treatment application was conducted in TGGs, a research-oriented structure for plant growth with semicontrolled conditions, taking into consideration natural environmental conditions. Each TGG is divided into three temperature modules which create a gradient of temperature (from module 1 of ambient temperature to module 3 of ambient temperature + 4°C), as the air heats up when passing through them (Morales et al., 2014). The temperature records during the experiment are included in Supplementary Figure 1. In addition, CO2 can be injected inside the TGGs, modifying the air CO2 concentration.

An equal number of plants of each clone were placed in the first and the third module of four TGGs, leaving the central module free of plants. Half of the plants (those located in modules 1) grew at ambient temperature (T), corresponding to the ambient temperature outdoors, while the other half of the plants (those located in modules 3) grew under ambient plus 4°C warmer temperature (T + 4). Besides, the air CO2 concentration was modified in two out of the four TGGs, resulting in half of the plants growing at current atmospheric CO2 concentration (ca. 400 ppm; ACO2) and the other half under increased air CO2 concentration (700 ppm; ECO2). Therefore, plants grew under four different CO2 and temperature conditions: (i) ambient temperature and ambient CO2 (T/ACO2), (ii) ambient temperature and elevated CO2 (T/ECO2), (iii) elevated temperature and ambient CO2 (T + 4/ACO2), and (iv) elevated temperature and elevated CO2 (T + 4/ECO2). The treatments were applied from fruit set (2016, May) to berry maturity (2016, September), which was considered to occur when the total soluble solid (TSS) content of the berries was ca. 22°Brix, each plant being measured individually (°Brix was determined on grape juice, after pressing entire grape berries, using a hand refractometer with temperature compensation). The number of plants per treatment and clone was 8.

Phenological Development and Berry Size

The length of the phenological development of grapes was determined for each plant by individually recording the dates corresponding to fruit set, mid-veraison (half of the berries in the bunch had started to change color), and maturity. The time intervals between fruit set and mid-veraison and between mid-veraison and maturity were calculated. Fruit set and mid-veraison were determined visually, and maturity was considered to be reached when the levels of TSS of two berries of each bunch were, at least, 22°Brix. This analysis was done periodically for each bunch every 2–3 days during the last weeks of development of the berries.

In order to carry out the different analyses of berries, five sampling points were determined: (i) onset of veraison, when berries had already softened and just began to color; (ii) mid-veraison (determined as described previously in this section), at this stage, berries with the same proportion of colored skin surface were sampled (ca. 50%); (iii) 1 week after mid-veraison; (iv) 2 weeks after mid-veraison; and (v) maturity, determined as described previously in this section. At the onset of veraison, three to four berries were sampled from each bunch, three berries at mid-veraison, 1 week after mid-veraison and 2 weeks after mid-veraison, and 10 berries at maturity. Each plant was sampled individually when reaching the desired stage. In order to avoid differences in berry composition due to their position in the bunch, all the berries were taken from the top and middle portion of the bunch, which allocate the highest number of berries. The diameter was measured with a caliper and berries were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until analyses.

Berry Analyses Preparation

Analyses were carried out by doing pools of berries (3–10 berries per bunch, see above, from two or three different plants per pool, four pools per treatment and clone). Berries were manually peeled and separated into skin, pulp, and seeds. Fresh skins, pulps, and seeds were weighed and the data obtained were used to determine the relative skin mass (relation between skin fresh weight and total berry fresh weight, expressed as a percentage). The pulp was crushed to obtain the must, which was centrifuged and used for sugar, malic acid, and amino acid analyses. The skin was freeze-dried in an Alph1-4, lyophilizer (CHRIST, Osterode, Germany), weighed to calculate the water content, and ground into powder using an MM200 ball grinder (Retsch, Haan, Germany) for carrying out the anthocyanin analyses.

Total Soluble Solids, Sugar, Malic Acid, and Amino Acid Profile Analyses

Total soluble solids content in the must was measured using a Handheld Digital Refractometer (RD110). Sugar (glucose and fructose) concentration was determined enzymatically using an automated absorbance microplate reader (Elx800UV, BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, United States) using the Glucose/Fructose kit from BIOSENTEC (Toulouse, France) according to the manufacturer. Malic acid was determined with a Bran and Luebbe TRAACS 800 autoanalyzer (Bran & Luebbe, Plaisir, France) as described in detail in Bobeica et al. (2015).

For the amino acid analysis, samples were derivatized with the AccQFluor Reagent (6-aminoquinolyl-N-hydroxy-succinimidyl-carbamate, Waters, Milford, MA, United States) (Cohen and Michaud, 1993) as described by Hilbert et al. (2015). The products of this reaction were analyzed with an UltiMate 3000 UHPLC system (Thermo Electron SAS, Waltham, MA, United States) equipped with an FLD-3000 Fluorescence Detector (Thermo Electron SAS, Waltham, MA, United States). Amino acids were separated using as eluents sodium acetate buffer (eluent A, 140 mM at pH 5.7), acetonitrile (eluent B), and water (eluent C) at 37°C and 0.5 ml min–1 through an AccQTag Ultra column, 2.1 mm × 100 mm, 1.7 μm (Waters, Milford, MA, United States) according to Habran et al. (2016). The concentration and identification of each compound was determined through a chromatographic analysis as described in Pereira et al. (2006), using an excitation wavelength of 250 nm and an emission wavelength of 395 nm. Samples were loaded alternated with control samples as in Torres et al. (2017).

Total Skin Anthocyanin Analyses

Anthocyanin analyses were carried out according to Torres et al. (2017) and described in detail by Acevedo de la Cruz et al. (2012) and Hilbert et al. (2015) with minor changes. In brief, ground dried skins were treated with methanol containing 0.1% HCl (v/v), in order to extract the pigments, and filtered using a polypropylene syringe filter of 0.45 μm (Pall Gelman Corp., Ann Arbor, MI, United States). The obtained extracts were separated using a Syncronis C18, 2.1 mm × 100 mm, 1.7 μm column (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) and analyzed with an UltiMate 3000 UHPLC system (Thermo Electron SAS, Waltham, MA, United States) equipped with DAD-3000 diode array detector (Thermo Electron SAS, Waltham, MA, United States). The wavelength used for recording the chromatographic profiles was 520 nm and the standard was malvidin-3-O-glucoside (Extrasynthese, Genay, France). The peak areas of chromatograms were calculated using the Chromeleon software (version 7.1) (Thermo Electron SAS, Waltham, MA, United States). The concentration of total anthocyanins was calculated as the sum of the concentration of individual anthocyanins. In order to evaluate the impact of environmental factors on the balance between anthocyanins and sugars, the ratio between the concentration of anthocyanins and the level of TSS was calculated at maturity.

Statistical Analysis

The data were statistically analyzed using R (3.5.1), carrying out a three-way ANOVA (clone, temperature, and CO2 concentration) and a Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) was carried out as a post hoc test when statistically significant differences were found (P < 0.05).

Results

Phenological Development

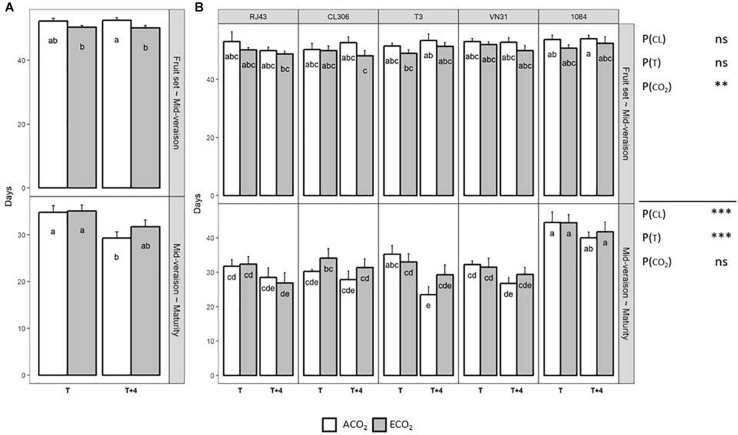

In general, elevated CO2 had a higher impact on grape phenology in the period comprised between fruit set to mid-veraison, whereas ripening (mid-veraison to maturity) was more affected by elevated temperature (Figure 1A). The number of days elapsed between fruit set and mid-veraison was slightly, but significantly, shortened by ECO2, and especially when it was combined with T + 4 (Figure 1A). However, this hastening effect of CO2 was nullified between mid-veraison and maturity, whereas the increase of temperature reduced significantly this period in up to 5 days. Also, the duration from mid-veraison to maturity was affected significantly by the clone identity, mainly because 1084 needed more time to reach maturity, regardless of the growing condition (Figure 1B). Although significant interactions among factors were not detected, it is worth pointing out the significant difference in the elapsed days between mid-veraison and maturity of T3 plants grown under T + 4/ACO2 compared with T/ACO2, as maturity was reached 12 days earlier when T + 4 was applied.

FIGURE 1.

Elapsed time between fruit set and mid-veraison and between mid-veraison and maturity of the five Tempranillo clones grown under four temperature/CO2 regimes: ambient temperature (T) or ambient temperature + 4°C (T + 4), combined with ambient CO2 (ca. 400 ppm, ACO2) or elevated CO2 (700 ppm, ECO2). Results (values are means ± SE) are presented according to the temperature (T or T + 4) and CO2 regime (ACO2 or ECO2), (A) considering all the clones as altogether (n = 20–40) and (B) considering each clone individually (n = 4–8). Means with letters in common within each chart (A,B) and period are not significantly different according to the least significant difference (LSD) test (P > 0.05). Probability values (P) for the main effects of clone, P(CL); temperature, P(T); and CO2, P(CO2). ∗∗∗P < 0.001; ∗∗P < 0.01; ns, not significant. All probability values for the interactions of factors [P(CL × T), P(CL × CO2), P(T × CO2), and P(CL × T × CO2)] were statistically not significant (P > 0.05).

Berry Characteristics

Berry diameter differed significantly among clones at the onset of veraison, mid-veraison, and maturity (Table 1). It was also modified by temperature, decreasing under T + 4 2 weeks after mid-veraison and at maturity. By contrast, the CO2 level did not markedly affect this berry characteristic. The only noteworthy interaction among the parameters was at mid-veraison, when the effect of ECO2 was different depending on the temperature regime and the clone (triple interaction).

TABLE 1.

Grape berry diameter of the five Tempranillo clones (RJ43, CL306, T3, VN31, and 1084) grown under four temperature/CO2 regimes: ambient temperature (T) or ambient temperature + 4°C (T + 4), combined with ambient CO2 (ca. 400 ppm, ACO2) or elevated CO2 (700 ppm, ECO2).

| Berry diameter (mm) | |||||||

| Onset of veraison | Mid-veraison | 1 week after mid-veraison | 2 weeks after mid-veraison | Maturity | |||

| RJ43 | 10.51 ± 0.18ab | 10.78 ± 0.23bc | 11.36 ± 0.21b | 13.19 ± 1.09a | 12.71 ± 0.17ab | ||

| CL306 | 10.11 ± 0.16b | 10.57 ± 0.13c | 11.36 ± 0.19b | 12.07 ± 0.19a | 12.33 ± 0.20b | ||

| T3 | 10.86 ± 0.20a | 11.11 ± 0.19b | 11.63 ± 0.23ab | 12.40 ± 0.22a | 13.11 ± 0.17a | ||

| VN31 | 10.77 ± 0.15a | 11.19 ± 0.13ab | 13.00 ± 1.25a | 13.81 ± 1.07a | 13.07 ± 0.16a | ||

| 1084 | 10.86 ± 0.23a | 11.60 ± 0.19a | 12.10 ± 0.20ab | 12.16 ± 0.30a | 12.88 ± 0.25a | ||

| T | 10.75 ± 0.12a | 11.18 ± 0.11a | 11.85 ± 0.13a | 13.39 ± 0.60a | 13.14 ± 0.13a | ||

| T + 4 | 10.49 ± 0.13a | 10.92 ± 0.13a | 11.93 ± 0.52a | 12.07 ± 0.15b | 12.50 ± 0.10b | ||

| ACO2 | 10.60 ± 0.10a | 11.07 ± 0.12a | 12.16 ± 0.51a | 12.42 ± 0.11a | 12.68 ± 0.13a | ||

| ECO2 | 10.64 ± 0.14a | 11.03 ± 0.13a | 11.62 ± 0.15a | 13.03 ± 0.63a | 12.96 ± 0.13a | ||

| RJ43 | T | ACO2 | 10.93 ± 0.49abc | 11.18 ± 0.47abcd | 11.55 ± 0.24b | 12.70 ± 0.15bc | 13.01 ± 0.52bcde |

| ECO2 | 10.39 ± 0.36bcd | 10.44 ± 0.43def | 11.45 ± 0.53b | 16.43 ± 4.35ab | 12.82 ± 0.13cdef | ||

| T + 4 | ACO2 | 10.50 ± 0.24bc | 10.18 ± 0.21ef | 10.73 ± 0.44b | 11.63 ± 0.18c | 12.56 ± 0.42defg | |

| ECO2 | 10.21 ± 0.33cd | 11.32 ± 0.53abcd | 11.70 ± 0.37b | 12.01 ± 0.11c | 12.46 ± 0.24defg | ||

| CL306 | T | ACO2 | 10.03 ± 0.18cd | 10.52 ± 0.20def | 11.35 ± 0.17b | 12.11 ± 0.25c | 11.84 ± 0.56g |

| ECO2 | 10.32 ± 0.34cd | 11.04 ± 0.07abcde | 11.93 ± 0.22b | 12.31 ± 0.37c | 12.95 ± 0.27bcdef | ||

| T + 4 | ACO2 | 10.68 ± 0.18abc | 10.71 ± 0.26cdef | 11.44 ± 0.54b | 12.69 ± 0.16bc | 12.52 ± 0.34defg | |

| ECO2 | 9.42 ± 0.20d | 10.02 ± 0.22f | 10.71 ± 0.31b | 11.18 ± 0.26c | 12.03 ± 0.19fg | ||

| T3 | T | ACO2 | 10.72 ± 0.33abc | 11.16 ± 0.04abcd | 12.09 ± 0.09b | 12.45 ± 0.19bc | 13.22 ± 0.14abcd |

| ECO2 | 11.59 ± 0.24a | 11.87 ± 0.09a | 12.46 ± 0.28b | 13.30 ± 0.23abc | 13.97 ± 0.23a | ||

| T + 4 | ACO2 | 10.29 ± 0.34cd | 10.74 ± 0.56cdef | 11.17 ± 0.47b | 11.95 ± 0.58c | 12.43 ± 0.14defg | |

| ECO2 | 10.83 ± 0.45abc | 10.68 ± 0.35cdef | 10.82 ± 0.44b | 11.91 ± 0.34c | 12.81 ± 0.20cdef | ||

| VN31 | T | ACO2 | 10.94 ± 0.31abc | 11.25 ± 0.19abcd | 11.97 ± 0.57b | 12.67 ± 0.08bc | 13.57 ± 0.13abc |

| ECO2 | 10.90 ± 0.35abc | 11.57 ± 0.23abc | 11.77 ± 0.75b | 16.79 ± 4.33a | 13.21 ± 0.25abcd | ||

| T + 4 | ACO2 | 10.68 ± 0.29abc | 11.16 ± 0.30abcd | 16.81 ± 4.86b | 13.04 ± 0.42abc | 12.54 ± 0.25defg | |

| ECO2 | 10.55 ± 0.32bc | 10.79 ± 0.21cdef | 11.47 ± 0.39b | 12.76 ± 0.29bc | 12.97 ± 0.44bcdef | ||

| 1084 | T | ACO2 | 10.87 ± 0.24abc | 11.93 ± 0.33a | 12.32 ± 0.54b | 12.63 ± 0.60bc | 13.02 ± 0.38bcde |

| ECO2 | 10.80 ± 0.53abc | 10.87 ± 0.41bcdef | 11.58 ± 0.50b | 12.47 ± 0.22bc | 13.84 ± 0.45ab | ||

| T + 4 | ACO2 | 10.38 ± 0.52bcd | 11.86 ± 0.18a | 12.15 ± 0.35a | 12.36 ± 0.15c | 12.12 ± 0.33efg | |

| ECO2 | 11.38 ± 0.54ab | 11.76 ± 0.41ab | 12.35 ± 0.18b | 11.19 ± 0.95c | 12.57 ± 0.52defg | ||

| P(CL) | * | *** | ns | ns | * | ||

| P(T) | ns | ns | ns | * | *** | ||

| P(CO2) | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ||

| P(CL × T) | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ||

| P(CL × CO2) | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ||

| P(T × CO2) | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ||

| P(CL × T × CO2) | ns | ** | ns | ns | ns | ||

Results (values are means ± SE) are shown according to clone identity (n = 16), temperature regime (n = 40), CO2 concentration (n = 40), and the combined factors (n = 4). Means with letters in common within the same stage and factor (clone, temperature, CO2, or their interactions) are not significantly different according to the least significant difference (LSD) test (P > 0.05). Probability values (P) for the main effects of clone, P(CL); temperature, P(T); CO2, P(CO2); and their interactions, P(CL ×T), P(CL × CO2), P(T× CO2), and P(CL ×T× CO2). ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; ns, not significant.

In general, berries from all the studied clones presented similar relative skin mass throughout the experiment except at maturity, when 1084 had significantly lower values than CL306, T3, and VN31 (Table 2). Relative skin masses were higher 1 and 2 weeks after mid-veraison in grapes developed under T + 4 compared with those grown at T. Grapes under ECO2 had a lower relative skin mass than ACO2 at the onset of veraison, but higher 1 and 2 weeks after mid-veraison. At maturity, the T3 clone was the most affected one by the increase in temperature of T + 4, especially when combined with ACO2.

TABLE 2.

Relative skin mass (%) in grape berries of the five Tempranillo clones (RJ43, CL306, T3, VN31, and 1084) grown under four temperature/CO2 regimes: ambient temperature (T) or ambient temperature + 4°C (T + 4), combined with ambient CO2 (ca. 400 ppm, ACO2) or elevated CO2 (700 ppm, ECO2).

| Relative skin mass (%) | |||||||

| Onset of veraison | Mid-veraison | 1 week after mid-veraison | 2 weeks after mid-veraison | Maturity | |||

| RJ43 | 16.76 ± 1.30a | 15.60 ± 0.89a | 14.02 ± 0.57a | 15.02 ± 0.76a | 16.50 ± 0.68ab | ||

| CL306 | 15.24 ± 0.66a | 14.27 ± 0.40ab | 14.73 ± 0.88a | 17.02 ± 1.57a | 17.51 ± 0.76a | ||

| T3 | 14.68 ± 0.64a | 13.76 ± 0.70ab | 14.20 ± 0.63a | 14.83 ± 1.03a | 16.88 ± 0.84a | ||

| VN31 | 15.43 ± 0.53a | 13.90 ± 0.75ab | 14.79 ± 0.55a | 15.62 ± 0.90a | 17.72 ± 0.87a | ||

| 1084 | 14.57 ± 0.58a | 13.24 ± 0.44b | 14.35 ± 0.60a | 14.81 ± 1.61a | 14.41 ± 0.78b | ||

| T | 15.48 ± 0.40a | 14.36 ± 0.37a | 13.85 ± 0.31b | 13.72 ± 0.32b | 16.03 ± 0.52a | ||

| T + 4 | 15.19 ± 0.59a | 13.94 ± 0.48a | 14.98 ± 0.47a | 17.31 ± 1.01a | 17.22 ± 0.51a | ||

| ACO2 | 16.56 ± 0.57a | 13.74 ± 0.46a | 13.67 ± 0.42b | 14.35 ± 0.77b | 16.81 ± 0.55a | ||

| ECO2 | 14.11 ± 0.33b | 14.57 ± 0.39a | 15.17 ± 0.37a | 16.56 ± 0.75a | 16.48 ± 0.5a | ||

| RJ43 | T | ACO2 | 17.79 ± 0.71ab | 15.33 ± 0.91abc | 12.24 ± 0.35c | 12.33 ± 0.57c | 15.80 ± 1.19bcdef |

| ECO2 | 13.75 ± 1.16bcd | 15.51 ± 2.80abc | 14.52 ± 0.79abc | 14.63 ± 0.86bc | 16.04 ± 1.72abcdef | ||

| T + 4 | ACO2 | 20.68 ± 4.63a | 16.15 ± 2.06a | 12.66 ± 0.18bc | 15.87 ± 1.39bc | 17.12 ± 1.93abcdef | |

| ECO2 | 14.81 ± 0.89bcd | 15.41 ± 1.64abc | 16.66 ± 1.27a | 17.26 ± 2.08abc | 17.02 ± 0.80abcdef | ||

| CL306 | T | ACO2 | 16.64 ± 1.35abc | 12.91 ± 0.41abc | 13.90 ± 0.29abc | 14.07 ± 1.08bc | 18.16 ± 2.76abcd |

| ECO2 | 14.48 ± 0.44bcd | 15.75 ± 0.86ab | 12.55 ± 0.74bc | 15.70 ± 0.98bc | 17.84 ± 1.15abcd | ||

| T + 4 | ACO2 | 15.04 ± 1.59bcd | 13.94 ± 0.74abc | 16.64 ± 3.13a | 15.30 ± 1.59bc | 18.60 ± 1.64abc | |

| ECO2 | 14.79 ± 1.80bcd | 14.46 ± 0.63abc | 15.84 ± 1.35ab | 22.58 ± 5.00a | 15.60 ± 0.71bcdef | ||

| T3 | T | ACO2 | 17.56 ± 1.15abc | 15.18 ± 1.05abc | 14.48 ± 1.75abc | 13.10 ± 0.82bc | 14.21 ± 1.50def |

| ECO2 | 12.05 ± 0.81d | 13.18 ± 0.74abc | 13.26 ± 0.65abc | 13.29 ± 1.53bc | 15.10 ± 0.29cdef | ||

| T + 4 | ACO2 | 15.17 ± 0.80bcd | 12.13 ± 2.36bc | 12.47 ± 0.60bc | 15.82 ± 3.01bc | 20.05 ± 0.91a | |

| ECO2 | 13.94 ± 0.52bcd | 14.54 ± 0.83abc | 16.58 ± 0.90a | 17.88 ± 2.06abc | 18.16 ± 1.95abcd | ||

| VN31 | T | ACO2 | 17.32 ± 1.59abc | 14.92 ± 1.19abc | 14.36 ± 0.85abc | 13.66 ± 0.93bc | 15.99 ± 1.79abcdef |

| ECO2 | 14.85 ± 0.75bcd | 13.44 ± 0.50abc | 14.78 ± 0.53abc | 15.82 ± 0.84bc | 19.61 ± 1.34ab | ||

| T + 4 | ACO2 | 15.43 ± 0.41bcd | 11.81 ± 2.22c | 13.36 ± 1.07abc | 14.09 ± 2.50bc | 17.34 ± 2.17abcde | |

| ECO2 | 14.10 ± 0.65bcd | 15.44 ± 1.42abc | 16.65 ± 1.42a | 19.57 ± 0.95ab | 17.94 ± 1.80abcd | ||

| 1084 | T | ACO2 | 15.59 ± 0.67bcd | 13.07 ± 0.38abc | 12.93 ± 1.14bc | 12.34 ± 0.35c | 14.10 ± 1.16def |

| ECO2 | 14.78 ± 1.10bcd | 14.35 ± 1.08abc | 15.50 ± 1.45abc | 12.75 ± 0.50bc | 12.03 ± 1.08f | ||

| T + 4 | ACO2 | 14.38 ± 0.92bcd | 11.97 ± 0.91bc | 13.66 ± 0.95abc | 17.12 ± 6.61abc | 17.07 ± 1.73abcdef | |

| ECO2 | 13.55 ± 1.85cd | 13.57 ± 0.82abc | 15.31 ± 1.14abc | 17.02 ± 0.96abc | 13.24 ± 0.94ef | ||

| P(CL) | ns | ns | ns | ns | * | ||

| P(T) | ns | ns | * | ** | ns | ||

| P(CO2) | *** | ns | ** | ns | ns | ||

Results (values are means ± SE) are shown according to the clone (n = 16), temperature (n = 40), CO2 concentration (n = 40), and the combined factors (n = 4). Means with letters in common within the same stage and factor (clone, temperature, CO2, or their interactions) are not significantly different according to the LSD test (P > 0.05). Probability values (P) for the main effects of clone, P(CL); temperature, P(T); and CO2, P(CO2). ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; ns, not significant. All probability values for the interactions of factors [P(CL ×T), P(CL × CO2), P(T× CO2), and P(CL ×T× CO2)] were statistically not significant (P > 0.05).

Malic Acid

The evolution of malic acid concentration throughout the ripening process was not affected by the clone identity, decreasing in a similar manner in all of them until maturity (Figure 2A). However, at maturity, the 1084 accession had the lowest malic acid levels and CL306 the highest (Figure 2B). Considering all the clones as a whole, T + 4 decreased significantly malic acid from mid-veraison onward with respect to T, while ECO2 raised acid malic significantly at the onset of veraison and reduced it at maturity compared with ACO2 (Figure 2A). For all the clones studied, grapes developed under current situation (T/ACO2) presented significantly higher levels of malic acid at maturity than those developed under climate change conditions (T + 4/ECO2) (Figure 2B). In the case of 1084, this difference was observed with plants grown at T + 4, regardless of the CO2 regime. Globally, there were no significant interactions among factors.

FIGURE 2.

Malic acid concentration of the five Tempranillo clones grown under four temperature/CO2 regimes: ambient temperature (T) or ambient temperature + 4°C (T + 4), combined with ambient CO2 (ca. 400 ppm, ACO2) or elevated CO2 (700 ppm, ECO2). Data (values are means ± SE, n = 4) are presented according to temperature (T or T + 4) and CO2 regime (ACO2 or ECO2) (A) throughout ripening and (B) at maturity. Data are presented according to the temperature (T or T + 4) and CO2 regime (ACO2 or ECO2) and considering each clone individually. Means with letters in common are not significantly different according to the LSD test (P > 0.05). Probability values (P) for the main effects of clone, P(CL); temperature, P(T); and CO2, P(CO2). ***P < 0.001; *P < 0.05; ns, not significant. All probability values for the interactions of factors [P(CL × T), P(CL × CO2), P(T × CO2), and P(CL × T × CO2)] were statistically not significant (P > 0.05).

Sugars and Total Soluble Solids

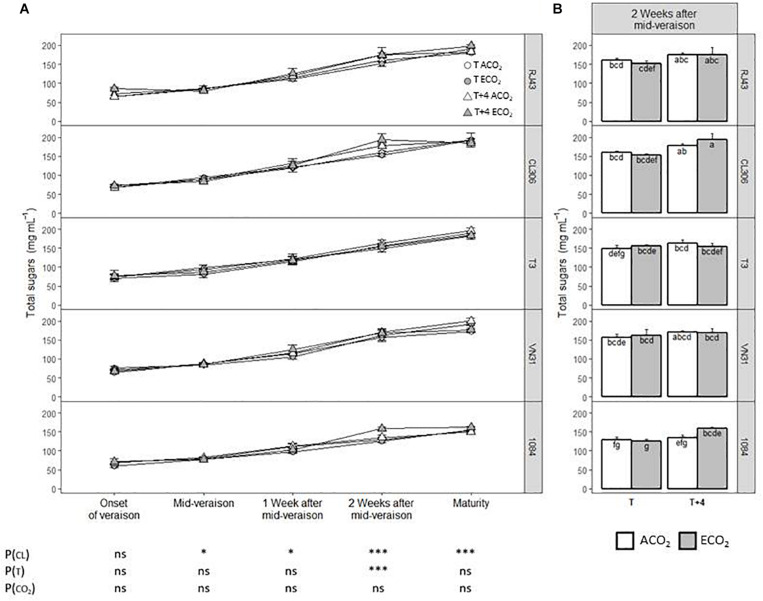

In general, the level of sugars (glucose and fructose) depended significantly on the clone from mid-veraison onward, being strongly affected by this factor 2 weeks after mid-veraison and at maturity (Figure 3A). Notably, 2 weeks after mid-veraison, the most contrasted clones were 1084 and CL306, with the lowest and highest sugar levels, respectively (Figure 3B). The T + 4 treatment increased significantly the sugar concentration 2 weeks after mid-veraison compared with T, whereas the atmospheric CO2 level did not have any effect on this parameter. Nonetheless, there were no significant interactions among the factors considered. The trends observed for total soluble solids at maturity (Supplementary Figure 2) were quite similar to those observed for the sum of glucose and fructose at this stage (Figure 3), clone 1084 being the one with the lowest TSS levels.

FIGURE 3.

Sugar concentration in berries of the five Tempranillo clones grown under four temperature/CO2 regimes: ambient temperature (T) or ambient temperature + 4°C (T + 4), combined with ambient CO2 (ca. 400 ppm, ACO2) or elevated CO2 (700 ppm, ECO2). Data are presented according to temperature (T or T + 4) and CO2 regime (ACO2 or ECO2) and considering each clone individually (values are means ± SE, n = 4): (A) throughout ripening and (B) 2 weeks after mid-veraison. Means with letters in common are not significantly different according to LSD test (P > 0.05). Probability values (P) for the main effects of clone, P(CL); temperature, P(T); and CO2, P(CO2). ***P < 0.001; *P < 0.05; ns, not significant. All probability values for the interactions of factors [P(CL × T), P(CL × CO2), P(T × CO2), and P(CL × T × CO2)] were statistically not significant (P > 0.05).

Amino Acids

In general, total amino acid concentration reached the highest values 2 weeks after mid-veraison in clones RJ43, CL306, and VN31, whereas the concentration of amino acid continued increasing until maturity in T3 and 1084 (Figure 4A and Supplementary Tables 1A–E). Amino acid levels were similar among clones throughout berry development, except 2 weeks after mid-veraison, when 1084 had lower levels in comparison with the other clones. At this stage, and considering all the clones, the T + 4 treatment reduced total amino acid concentration compared with the T treatment (from 15.9 ± 1.33 to 12.3 ± 1.18 μmol ml–1, respectively, Supplementary Table 1D). Also, ECO2 diminished the amino acid levels with respect to ACO2 (from 17.1 ± 1.48 to 11.2 ± 0.82 μmol ml–1, respectively) 2 weeks after mid-veraison (Supplementary Table 1D). At maturity, there were no significant effects of temperature and CO2 (neither individually nor combined). However, T + 4 tended to reduce the concentration of total amino acids (especially under ACO2) in all the clones and ECO2 tended to reduce the amino acid levels of CL306, T3, and VN31 at ambient temperature (Figure 4B and Supplementary Table 1E).

FIGURE 4.

Amino acid concentration in berries of the five Tempranillo clones grown under four temperature/CO2 regimes: ambient temperature (T) or ambient temperature + 4°C (T + 4), combined with ambient CO2 (ca. 400 ppm, ACO2) or elevated CO2 (700 ppm, ECO2). Data are presented according to temperature (T or T + 4) and CO2 regime (ACO2 or ECO2) and considering each clone individually (values are means ± SE, n = 3–4). (A) Throughout ripening and (B) at maturity. Relative abundance of amino acids (C) grouped by their precursor. Means with letters in common are not significantly different according to the LSD test (P > 0.05). Probability values (P) for the main effects of clone, P(CL); temperature, P(T); and CO2, P(CO2). ***P < 0.001; *P < 0.05; ns, not significant. All probability values for the interactions of factors [P(CL × T), P(CL × CO2), P(T × CO2), and P(CL × T × CO2)] were statistically not significant (P > 0.05).

The relative abundance of the different amino acids varied among clones. Specifically, 1 and 2 weeks after mid-veraison and at maturity, the pyruvate and aspartate derivatives were more abundant in 1084 at the expense of α-ketoglutarate derivatives (except GABA and arginine, which increased) (Figure 4C and Supplementary Tables 1D,E). Considering all the clones as a whole, ECO2 significantly reduced the proportion of α-ketoglutarate derivatives (although arginine and GABA tended to increase in the later stages of the ripening period at ECO2), increasing the abundance of those originated from aspartate and pyruvate (2 weeks after mid-veraison and at maturity, respectively). Even though there were no significant interactions, there were two exceptions to this effect at maturity, as ECO2 increased α-ketoglutarate derivatives in the grapes of clones RJ43 and 1084 exposed to T and T + 4, respectively. In addition, the rise in the relative abundance of pyruvate derivatives observed in the ECO2 treatment at maturity was globally stronger at T + 4 (Figure 4C and Supplementary Table 1E). Moreover, at the onset of veraison, ECO2 strongly increased the relative abundance of phenylalanine in all clones and more specifically in CL306 and 1084 when combined with elevated temperature.

Total Skin Anthocyanins

Anthocyanin levels did not differ significantly in the early ripening period among clones, but 2 weeks after mid-veraison and at maturity, the concentration of total anthocyanins was lower in 1084, whereas RJ43 showed the highest values (Figures 5A,B). T + 4 had a significant enhancing effect on anthocyanins at the onset of veraison and 2 weeks after mid-veraison, regardless of the clone and CO2 level, this effect disappearing at maturity. ECO2 increased anthocyanin concentration at the onset of veraison and mid-veraison but reduced the levels 2 weeks after mid-veraison (Figure 5A). At maturity, although there were no significant interactions between factors, the T + 4/ECO2 treatment seemed to have different effects depending on the clone. Whereas, in RJ43, the grapes exposed to T + 4/ECO2 (climate change conditions) had significantly lower anthocyanin levels than those exposed to T/ACO2 (current conditions), in CL306, the concentration of skin anthocyanins increased with climate change conditions (T + 4/ECO2) (Figure 5B).

FIGURE 5.

Total anthocyanin concentration in berries of the five Tempranillo clones grown under four temperature/CO2 regimes: ambient temperature (T) or ambient temperature + 4°C (T + 4), combined with ambient CO2 (ca. 400 ppm, ACO2) or elevated CO2 (700 ppm, ECO2). Data are presented according to temperature (T or T + 4) and CO2 regime (ACO2 or ECO2) and considering each clone individually (values are means ± SE, n = 4). (A) Throughout ripening and (B) at maturity. Means with letters in common are not significantly different (P > 0.05) according to the LSD test. Probability values (P) for the main effects of clone, P(CL); temperature, P(T); and CO2, P(CO2). ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; ns, not significant. All probability values for the interactions of factors [P(CL × T), P(CL × CO2), P(T × CO2), and P(CL × T × CO2)] were statistically not significant (P > 0.05).

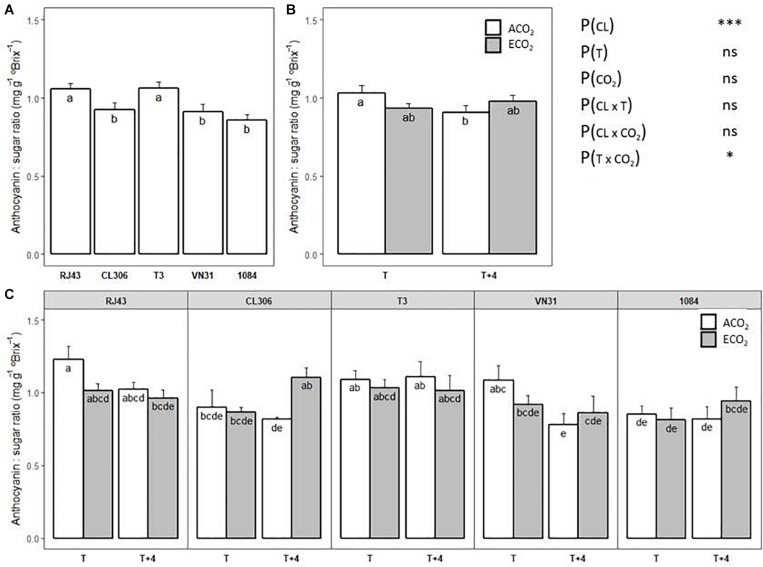

Total Anthocyanins to TSS Ratio

Clones showed different anthocyanin to TSS ratios at maturity regardless of the temperature and CO2 regime, RJ43 and T3 having the highest values (Figure 6A). Considering the clones altogether, a significant interaction between temperature and CO2 was observed (Figure 6B). Thus, the significant decrease of the ratio between anthocyanins and TSS under ACO2 induced by T + 4, with respect to T, disappeared under ECO2. When the temperature and CO2 effects were analyzed for each clone independently, the growing conditions showed slightly different effects on the anthocyanin to TSS ratio (Figure 6C). In RJ43 and VN31, the impact of T + 4 on the ratio was more evident under ACO2 conditions. ECO2 strongly increased the ratio in CL306 plants at T + 4, while it did not have any effect at T. Finally, neither temperature nor CO2 had a marked impact on the relationship between anthocyanins and TSS in T3 and 1084.

FIGURE 6.

Anthocyanin to TSS ratio at maturity of the five Tempranillo clones grown under four temperature/CO2 regimes: ambient temperature (T) or ambient temperature + 4°C (T + 4), combined with ambient CO2 (ca. 400 ppm, ACO2) or elevated CO2 (700 ppm, ECO2). Results (values are means ± SE) are presented according to: (A) clone identity (n = 15–16); (B) the temperature (T or T + 4) and CO2 regime (ACO2 or ECO2) (n = 19–20); and (C) clone identity, temperature, and CO2 regime (n = 3–4). Means with letters in common within each chart (A–C) are not significantly different according to the LSD test (P > 0.05). Probability values (P) for the main effects of clone, P(CL); temperature, P(T); and CO2, P(CO2). ***P < 0.001; *P < 0.05; ns, not significant. All probability values for the interactions of factors [P(CL × T), P(CL × CO2), P(T × CO2), and P(CL × T × CO2)] were statistically not significant (P > 0.05).

Discussion

Performance of Clones

Clones showed different characteristics in all the studied parameters. The accession that differed the most from the others studied was 1084. It had an extremely long berry ripening period associated with a lower sugar accumulation rate, not even reaching the optimum sugar levels for wine production. The 1084 accession also had berries with low relative skin mass and presented the lowest values of malic acid at maturity. Despite T3, VN31, and RJ43 having similar berry diameter to 1084 (indicating similar size), their malic acid values were higher than in 1084. This result suggests that the low concentration of malic acid in 1084 was not associated with a dilution effect due to high berry size. After veraison, malate is released from the vacuole and becomes available for catabolism through involvement in gluconeogenesis, respiration through the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, amino acid interconversions, and the production of secondary compounds such as anthocyanins and flavonols (Ruffner and Kliewer, 1975; Ruffner et al., 1976; Ruffner, 1982; Famiani et al., 2000; Ollat et al., 2002; Sweetman et al., 2009). Probably, the longer ripening period of the 1084 accession, already seen in previous experiments (Arrizabalaga et al., 2018), contributed to higher malate breakdown, thus reaching a lower malic acid concentration at maturity. Interestingly, clones differed in the moment to reach the amino acidic maturity, earlier in RJ43, CL306, and VN31 than in T3 and 1084. The amino acid profile at maturity was also different among clones, 1084 showing a reduced proportion of α-ketoglutarate and increased abundance of pyruvate and aspartate derivatives. The higher concentration of isoleucine, leucine, and valine (aromatic precursors) in 1084 might have a positive effect on the final wine aroma (Valdés et al., 2019).

The 1084 accession also presented a lower concentration of skin anthocyanins, compared with the other clones. The results are in agreement with our previous work (Arrizabalaga et al., 2018) and may be related to the slow sugar accumulation rate observed in 1084. Dai et al. (2014), using an experimental system allowing the long-term in vitro culture of grape berries, reported an induction in total anthocyanins by rising sugar concentrations in the culture medium, as well as a negative correlation between phenylalanine and total anthocyanin levels. In the present study, phenylalanine was similar in 1084, and even higher 2 weeks after mid-veraison, compared with the other clones. Therefore, the lower anthocyanin accumulation may be a consequence of a limitation in the biosynthetic enzymatic activity rather than to a limitation of its precursor, as suggested by Dai et al. (2014). Also, it is possible that α-ketoglutarate availability is lower in 1084; thus, biosynthetic steps that use α-ketoglutarate as reducing power for anthocyanin accumulation (i.e., hydroxylases) become limiting. Indeed, α-ketoglutarate level was reported to be one of the metabolic drivers of anthocyanin accumulation in grape cells (Soubeyrand et al., 2018). In opposition to the results obtained by Roby and Matthews (2008), the anthocyanin content in berries was not systematically positively correlated to the relative skin mass, except for 1084. These discrepancies may be related to the fact that in our case anthocyanins were measured in dry skin and Roby and Matthews (2008) did it in the whole berry. In addition, both 1084 and T3 had some of the largest diameters. However, the relative skin mass of this two clones differed significantly, T3 having a higher value and 1084 the lowest. These results indicate a lack of effect of berry size on the relative skin mass already observed by Barbagallo et al. (2011). These berry parameters are important as they are considered to determine the solutes extraction during the maceration process (Walker et al., 2005; Matthews and Nuzzo, 2007; Roby and Matthews, 2008; Barbagallo et al., 2011).

Global Response of Tempranillo Clones to Elevated Temperature

The increment of temperature shortened the elapsed time between mid-veraison and maturity and reduced the size of berries at the end of the ripening process. These results agree with previous studies, in which berries stopped increasing their volume after being heat-treated at mid-veraison and mid-ripening (Kliewer, 1977; Roby and Matthews, 2008; Keller, 2010; Orduña, 2010) and high temperature accelerated the ripening process (Jones and Davis, 2000; Duchêne and Schneider, 2005; Keller, 2010; Arrizabalaga et al., 2018). Given that maturity was determined by the level of TSS (ca. 22°Brix), the reduction of the time to reach this stage in the T + 4 treatment indicates a faster and more efficient accumulation of sugars under these conditions. In the present study, the lower berry size in the T + 4 may have contributed to the higher concentration of sugars observed. However, the effect of high temperatures on sugar accumulation varies among studies and conditions. Whereas elevated temperature has been reported to enhance sugar accumulation (Jones et al., 2005; Mosedale et al., 2016), in other cases, berry sugar content at harvest was not affected (Lecourieux et al., 2017), and sugar accumulation was stopped (Roby and Matthews, 2008; Greer and Weston, 2010), or even decreased (Carbonell-Bejerano et al., 2013; Greer and Weedon, 2013; Kuhn et al., 2014). These apparently contradictory results may be due to differences in the experimental procedures, which included more extreme temperatures than in the present one, thus reducing photosynthesis and limiting the supply of sugar to the berries (Greer and Weedon, 2013).

It is well established that warm temperatures promote the decrease of organic acid levels in grape berries after mid-veraison, by accelerating malate degradation (Orduña, 2010; Carbonell-Bejerano et al., 2013; Sweetman et al., 2014; Torres et al., 2016). Malic acid respiration is favored by heat, and the genes involved in its transmembrane transport display a marked regulation by temperature (Rienth et al., 2016). In addition, the enhancement of the anaplerotic capacity of the TCA cycle for amino acid biosynthesis by elevated temperatures has also been suggested (Sweetman et al., 2014; Lecourieux et al., 2017). In our work, although malic acid degradation was promoted by T + 4 from mid-veraison onward, the concentration of total amino acids tended to decrease in this treatment compared with T, and changes in the proportion α-ketoglutarate, pyruvate, or aspartate amino acid derivatives were not so obvious. These results may indicate that under the temperature conditions assayed, 4°C of difference between T and T + 4 vs. increases of 8 (Lecourieux et al., 2017) and 10°C (Sweetman et al., 2014) in the mentioned studies, the anaplerotic capacity of the TCA cycle for amino acid biosynthesis may not be markedly increased. Other pathways such as gluconeogenesis may have played a more important role in malate degradation, thus contributing to the differences in sugar accumulation observed between temperature regimes. Despite the limited changes in the amino acid profile, an increased proportion of proline and arginine was observed under high temperature, as previously reported by other authors (Lecourieux et al., 2017; Torres et al., 2017). Proline has a protective role in plants against abiotic stresses, including elevated temperature, whereas arginine is an important source of nitrogen during winemaking (Garde-Cerdán et al., 2011), despite being a precursor of putrescine, a compound with negative effects on human health (Guo et al., 2015).

Considering the clones altogether, high temperature significantly increased the concentration of anthocyanins 2 weeks after mid-veraison, but it did not affect the final anthocyanin levels at maturity. These results do not agree with previous studies that demonstrate that high temperature during ripening had a negative impact on anthocyanin biosynthesis in berries by acting on the correspondent enzymes and transcription factors (Yamane et al., 2006; Mori et al., 2007; Rienth et al., 2014, 2016; Lecourieux et al., 2017). In those experiments, the expression of genes related to flavonoid biosynthesis in grape skins was found to be repressed by high temperatures, especially genes coding for the key enzyme of the phenylpropanoid pathway, the phenylalanine-ammonia-lyase (PAL) or MYB transcription factors, which control anthocyanin biosynthesis. However, the repression of VvMYBA1 by high temperature described by Yamane et al. (2006) was not confirmed by other authors (Lijavetzky et al., 2012). Besides, in addition to a lower anthocyanin biosynthesis, some authors have reported increases in anthocyanin degradation due to high temperature (Mori et al., 2007). Accordingly, the increase in anthocyanin concentration induced by T + 4 observed 2 weeks after mid-veraison in our study was not detected at maturity (P(T) > 0.05), which might be caused by an earlier degradation of anthocyanins under elevated temperature.

Anthocyanin levels have also been reported to be differentially affected by temperature in different cultivars (Downey et al., 2006). Total anthocyanins decreased with high temperature in Merlot (Spayd et al., 2002; Tarara et al., 2008), Malbec (de Rosas et al., 2017), Pione (Azuma et al., 2012), Cabernet Sauvignon (Mori et al., 2007; Lecourieux et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2019), and Muscat Hamburg (Carbonell-Bejerano et al., 2013), while the final concentration of anthocyanins increased in Merlot by reducing the day temperature oscillations (Cohen et al., 2008). In the case of Tempranillo, Kizildeniz et al. (2018), in a 3-year experiment under similar conditions to this study, did not observe significant effects of high temperature on final anthocyanin levels. Also, differences in the response of anthocyanins to temperature were detected among different clones of Tempranillo, not all the clones being equally affected (Torres et al., 2017; Arrizabalaga et al., 2018). Furthermore, some authors also reported that the stage of berry growth at which heat treatment was applied could modulate the plant response in terms of anthocyanin content (Lecourieux et al., 2017; Gouot et al., 2019a, b).

Global Response of Tempranillo Clones to Elevated CO2

High atmospheric CO2 concentration slightly hastened grape phenology, but only from fruit set to mid-veraison, as reported by Martínez-Lüscher et al. (2016a) for red and white Tempranillo. Regarding fruit composition, the increase in malic acid concentration of grapes exposed to ECO2 at the onset of veraison may indicate an enhancement of the organic acid biosynthesis at early berry development stages. These differences disappeared in later stages, when the degradation of malic acid took place, and the grapes ripened under ECO2 conditions reaching even lower malic acid levels at maturity than those grown at ACO2, possibly because of an accelerated breakdown. Similarly, Bindi et al. (2001), in a field experiment using a free air CO2 enrichment (FACE) facility, observed that organic acid components were positively affected by increases in CO2 concentration at the middle of the ripening season, an effect that almost completely vanished at maturity. On the other hand, ECO2 significantly decreased the amino acid concentration at the onset of veraison and 2 weeks after mid-veraison. Elevated CO2 may induce a priority in the storage of nitrogen-free compounds (i.e., carbohydrates) compared with nitrogen-containing compounds, such as amino acids and proteins (Myers et al., 2014). In our case, the concentration of sugars in the berries was not significantly altered by ECO2 at these stages, so the decrease in amino acids could be a consequence of the inhibition of N assimilation as reported in different plant species (Serret et al., 2018). Similarly, in a previous study with the same clones and under similar growth conditions, berries exposed to ECO2 showed lower N concentration in the berries (Arrizabalaga-Arriazu et al., 2020). The differences observed up to 2 weeks after veraison in the present study decreased at maturity, when the ECO2 treatment showed only a slightly lower total amino acid concentration. At this stage, even though the relative abundance of some individual amino acids was significantly affected by ECO2 conditions, the proportions of amino acid families according to their precursor were little modified, except a slightly reduced proportion of α-ketoglutarate derivatives, at the expense of those originated from pyruvate. The significant decrease in the concentration of glutamine under ECO2 may involve a limitation for yeast growth during fermentation since glutamine, together with arginine, is one of the mayor sources of N for yeast (Zoecklein et al., 1999).

Taking into consideration the clones altogether, plants grown at ECO2 presented an increased concentration of total grape skin anthocyanins at the beginning of the ripening period, which may indicate a slight hastening in the synthesis of these compounds in this treatment. In contrast, 2 weeks after mid-veraison, ECO2 plants had lower anthocyanin concentration than ACO2, these differences disappearing at maturity. These results do not agree with the observations of other authors, who reported no effect (Gonçalves et al., 2009) or a rising effect of CO2 on anthocyanins at maturity (Kizildeniz et al., 2015). In the same way, studies on the effects of elevated CO2 on the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway in different plant species report contradictory results. For example, in strawberry and table grapes, elevated CO2 levels decreased anthocyanin content by decreasing the expression of genes involved in the phenylpropanoid metabolism, especially the one coding the PAL enzyme (Sanchez-Ballesta et al., 2007; Li et al., 2019). In contrast, increased anthocyanin content and stimulated enzyme activity have been observed in ginger and Labisia pumila under elevated CO2 (Ghasemzadeh et al., 2012; Jaafar et al., 2012).

Response of Clones to Combined Elevated Temperature and CO2

The analysis of the combined effects of high temperature and elevated CO2 on the parameters analyzed indicates low interactive effects of these environmental factors on sugar accumulation and, thus, in the length of the ripening period, as ECO2 did not modify the hastening effect induced by T + 4. Conversely, the increase in temperature and CO2 showed additive effects enhancing malic acid degradation, a phenomenon especially marked in the 1084 accession (probably due to its longer exposure to these conditions), but less evident in RJ43 and CL306. Such reduction of malic acid content and its impact on must acidity should certainly affect wine production, not only for its contribution to sourness and organoleptic properties but also because of its influence on wine microbiological stability. In addition, it might make the winemaking process more expensive in the future due to the need of acidifying the must for achieving a proper fermentation (Keller, 2010). The combined application of elevated temperature and high CO2 did not seem to have a marked impact on the total level of amino acids at maturity, although a tendency to decrease the amino acid concentrations was observed as reported by Martínez-Lüscher et al. (2016a). This effect was more evident 2 weeks after mid-veraison, T + 4 and ECO2 significantly reducing their concentration. These results suggest an impact of climate change delaying the amino acidic maturity of grapes, which seemed to be reached some weeks earlier in the T/ACO2 treatment. Amino acids (excluding proline and hydroxyproline) are very important components of the yeast assimilable nitrogen (YAN), thus having implication for must fermentation. A decrease of total amino acids level could involve a lower N availability during the fermentation process. In the same way, a reduction in the concentration of shikimate and phosphoglycerate derivatives may have implications in the organoleptic properties of the wine produced from these grapes, since the shikimate route is involved in the biosynthesis of aromatic amino acids (tyrosine and phenylalanine) and the phenylpropanoid pathway (phenylalanine).

As for amino acids, combined elevated temperature and CO2 did not significantly impact anthocyanin concentration at maturity when considering all the clones as a whole. However, the observed increase due to high temperature 2 weeks after veraison was offset by combination with elevated CO2. Interestingly, a significant interaction between temperature and CO2 was observed for the relationship between anthocyanin and sugar levels: the temperature-induced decrease in this ratio under ACO2 was not observed under ECO2. This result suggests that in a future climate change scenario, elevated CO2 may, at least partially, mitigate the negative impact of high temperature on the imbalance between sugars and anthocyanins in ripe berries.

In addition, regarding the anthocyanin content, there was a wide range of responses of the clones studied to climate change conditions. Total anthocyanin concentration at maturity was impacted by combined elevated temperature and CO2, showing a decrease in RJ43, T3, and VN31 (stronger in the former), despite their difference in the reproductive cycle length (defined as intermediate, short, and long, respectively). Conversely, combined elevated temperature and CO2 increased anthocyanin content in CL306 (characterized as a short reproductive cycle clone) and in 1084 (long reproductive cycle). Moreover, while in RJ43 and VN31 climate change conditions (T + 4/ECO2) markedly reduced the anthocyanin to sugar ratio with respect to the current conditions (T/ACO2) (differences statistically significant in RJ43), the balance between these two compounds was less affected in CL306, T3, and 1084. Grapevine is characterized by a pronounced sensitivity toward the environment, and the metabolic composition of the berries has been reported to show a broad phenotypic plasticity, offering advantages such as the range of different wines that can be produced from the same cultivar and the adaptation of existing cultivars to different growing regions (Keller, 2010). The present results suggest that clones of the same variety may perform differently under climate change conditions, some, such as RJ43, showing greater variation and others, such as 1084, offering more consistency. Unfortunately, we cannot directly associate these different performances with the length of their grape development period as we hypothesized originally, at least as far as anthocyanins and anthocyanin to sugar ratio are concerned. In this line, although 1084, with the longest length of the reproductive cycle, was one of the least affected in terms of anthocyanin and sugar balance, other clones that exhibited an early maturity (CL306 and T3) were not so affected either. A recent study has demonstrated differences in the berry phenotypic plasticity between grapevine varieties in response to changes in environmental conditions, Cabernet Sauvignon being less dependent on growth conditions, thus showing a limited transcriptomic plasticity associated with epigenetic regulation (Dal Santo et al., 2018). These authors also concluded that within-cultivar diversity may modulate gene expression in response to environmental cues. We suggest that clones within the same variety can also exhibit different degrees of phenotypic plasticity for grape composition and, consequently, different capacities of adaptation to climate change conditions. Recently, Tortosa et al. (2019) have reported that some clones of Tempranillo variety can perform better water use efficiency than others depending of the water availability conditions. Although the results obtained need to be considered in the light of the limitations of the study (i.e., 1 year experiment, potted plants, and controlled conditions), and they should be validated with studies in the field, the differences observed point toward the usefulness of the exploitation of the grapevine genotypic diversity in order to optimize the genotype–environment interaction and the adaptation of traditional varieties to the foreseen climate scenarios.

Conclusion

The projected increases in atmospheric CO2 concentration and in average air temperature advanced grape maturity, reducing the elapsed time between fruit set and mid-veraison and between mid-veraison and maturity, respectively. High temperature hastened berry ripening, sugar accumulation, and malic acid breakdown, especially when combined with elevated CO2. In contrast, climate change conditions seemed to delay amino acidic maturity. Even though the increase of temperature and high CO2 concentration (both individually and combined) did not affect anthocyanin concentration, the clones studied showed different values for this parameter. The reduction of the ratio between anthocyanins and TSS under T + 4 conditions was partially mitigated by ECO2. Additionally, the study reveals the existence of a differential response of Tempranillo clones to the projected future temperature and CO2 levels in terms of grape composition.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

FM, GH, IP, and JI: conceptualization. GH and IP: methodology. MA-A: investigation. JI: resources, project administration, and funding acquisition. GH, IP, and MA-A: data curation and writing – original draft preparation. EG, FM, GH, IP, JI, and MA-A: writing – review and editing. GH, IP, and JI: supervision. All authors approved the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to M. Oyarzun, A. Urdiain, H. Santesteban, C. Renaud, and C. Bonnet for their excellent technical assistance, and E. García-Escudero, J. M. Martínez-Zapater, E. Baroja (ICVV), J. F. Cibrain (EVENA), and R. García (Vitis Navarra) for the selection of clones and for providing the plant material to do the experiments.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad of Spain (AGL2014-56075-C2-1-R), Fundación Universitaria de Navarra (2018), European Union (Erasmus+ grant to MA-A), Aquitaine Regional Council (AquiMOb grant to MA-A), and Asociación de Amigos de la Universidad de Navarra (doctoral grant to MA-A). This work also supported by the metaprogramme Adaptation of Agriculture and Forests to Climate Change (AAFCC) of the French National Institute for Agriculture, Food and Environment (INRAE), in the frame of LACCAVE2-21 project.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2020.603687/full#supplementary-material

Daily minimum and maximum temperatures recorded in the modules of ambient temperature (T) and ambient temperature + 4°C (T + 4) of the TGGs during the experiment.

Total soluble solids concentration at maturity in berries of the five Tempranillo clones grown under four temperature/CO2 regimes: ambient temperature (T) or ambient temperature + 4°C (T + 4), combined with ambient CO2 (ca. 400 ppm, ACO2) or elevated CO2 (700 ppm, ECO2). Data are presented according to the temperature (T or T + 4) and CO2 regime (ACO2 or ECO2) and considering each clone individually (values are means ± SE, n = 4). Means with letters in common are not significantly different according to LSD test (P > 0.05).

References

- Acevedo de la Cruz A., Hilbert G., Rivière C., Mengin V., Ollat N., Bordenave L., et al. (2012). Anthocyanin identification and composition of wild Vitis spp. accessions by using LC-MS and LC-NMR. Analyt. Chim. Acta 732 145–152. 10.1016/j.aca.2011.11.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrizabalaga M., Morales F., Oyarzun M., Delrot S., Gomès E., Irigoyen J. J., et al. (2018). Tempranillo clones differ in the response of berry sugar and anthocyanin accumulation to elevated temperature. Plant Sci. 267 74–83. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2017.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrizabalaga-Arriazu M., Morales F., Irigoyen J. J., Hilbert G., Pascual I. (2020). Growth performance and carbon partitioning of grapevine Tempranillo clones under simulated climate change scenarios: elevated CO2 and temperature. J. Plant Physiol. 252:153226. 10.1016/j.jplph.2020.153226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azuma A., Yakushiji H., Koshita Y., Kobayashi S. (2012). Flavonoid biosynthesis-related genes in grape skin are differentially regulated by temperature and light conditions. Planta 236 1067–1080. 10.1007/s00425-012-1650-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbagallo M. G., Guidoni S., Hunter J. J. (2011). Berry size and qualitative characteristics of Vitis vinifera L. cv. Syrah. S. Afr. J. Enol. Viticult. 32 129–136. 10.21548/32-1-1372 10408659 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bindi M., Fibbi L., Miglietta F. (2001). Free Air CO2 Enrichment (FACE) of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.): II. Growth and quality of grape and wine in response to elevated CO2 concentrations. Eur. J. Agron. 14 145–155. 10.1016/S1161-0301(00)00093-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bobeica N., Poni S., Hilbert G., Renaud C., Gomès E., Delrot S., et al. (2015). Differential responses of sugar, organic acids and anthocyanins to source-sink modulation in Cabernet Sauvignon and Sangiovese grapevines. Front. Plant Sci. 6:382. 10.3389/fpls.2015.00382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonell-Bejerano P., Royo C., Mauri N., Ibáñez J., Zapater J. M. M. (2019). “Somatic variation and cultivar innovation in grapevine,” in Advances in Grape and Wine Biotechnology, eds Morata A., Loira I. (London: IntechOpen; ), 1–22. 10.5772/intechopen.86443 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonell-Bejerano P., Santa María E., Torres-Pérez R., Royo C., Lijavetzky D., Bravo G., et al. (2013). Thermotolerance responses in ripening berries of Vitis vinifera L. cv Muscat Hamburg. Plant Cell Physiol. 54 1200–1216. 10.1093/pcp/pct071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cibriáin F., Jimeno K., Sagüés A., Rodriguez M., Abad J., Martínez M. C., et al. (2018). TempraNA?: tempranillos con matrícula. Navarra Agraria 229 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. A., Michaud D. P. (1993). Synthesis of a fluorescent derivatizing reagent, 6-aminoquinolyl-N- hydroxysuccinimidyl carbamate, and its application for the analysis of hydrolysate amino acids via high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal. Biochem. 211 279–287. 10.1006/abio.1993.1270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. D., Tarara J. M., Kennedy J. A. (2008). Assessing the impact of temperature on grape phenolic metabolism. Analyt. Chim. Acta 621 57–67. 10.1016/j.aca.2007.11.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conde C., Silva P., Fontes N., Dias A., Tavares R., Sousa M., et al. (2007). Biochemical changes throughout grape berry development and fruit and wine quality. Food 1 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha J., Santos M. T., Carneiro L. C., Fevereiro P., Eiras-Dias J. E. (2009). Portuguese traditional grapevine cultivars and wild vines (Vitis vinifera L.) share morphological and genetic traits. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 56 975–989. 10.1007/s10722-009-9416-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Z. W., Meddar M., Renaud C., Merlin I., Hilbert G., Delrot S., et al. (2014). Long-term in vitro culture of grape berries and its application to assess the effects of sugar supply on anthocyanin accumulation. J. Exp. Bot. 65 4665–4677. 10.1093/jxb/ert489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Santo S., Zenoni S., Sandri M., De Lorenzis G., Magris G., De Paoli E., et al. (2018). Grapevine field experiments reveal the contribution of genotype, the influence of environment and the effect of their interaction (G × E) on the berry transcriptome. Plant J. 93 1143–1159. 10.1111/tpj.13834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Rosas I., Ponce M. T., Malovini E., Deis L., Cavagnaro B., Cavagnaro P. (2017). Loss of anthocyanins and modification of the anthocyanin profiles in grape berries of Malbec and Bonarda grown under high temperature conditions. Plant Sci. 258 137–145. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2017.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey M. O., Dokoozlian N. K., Krstic M. P. (2006). Cultural practice and environmental impacts on the flavonoid composition of grapes and wine: a review of recent research. Am. J. Enol. Viticult. 57 257–268. [Google Scholar]

- Duchêne E., Huard F., Dumas V., Schneider C., Merdinoglu D. (2010). The challenge of adapting grapevine varieties to climate change. Clim. Res. 41 193–204. 10.3354/cr00850 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duchêne E., Schneider C. (2005). Grapevine and climatic changes: a glance at the situation in Alsace. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 25 93–99. 10.1051/agro:2004057 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dusenge M. E., Duarte A. G., Way D. A. (2019). Plant carbon metabolism and climate change: elevated CO2 and temperature impacts on photosynthesis, photorespiration and respiration. New Phytol. 221 32–49. 10.1111/nph.15283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EVENA (2009). Evaluación de Clones Comerciales de seis Variedades de vid en Navarra. 1995-2005. Pamplona: Desarrollo Rural y Medio Ambiente Gobierno de Navarra. [Google Scholar]

- Famiani F., Walker R. P., Tecsi L., Chen Z., Proietti P., Leegood R. C. (2000). An immunohistochemical study of the compartmentation of metabolism during the development of grape (Vitis vinifera L.) berries. J. Exper. Bot. 51 675–683. 10.1093/jxb/51.345.675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garde-Cerdán T., Lorenzo C., Martínez-Gil A. M., Lara J. F., Pardo F., Salinas M. R. (2011). “Evolution of nitrogen compounds during grape ripening from organic and non-organic monastrell-nitrogen consumption and volatile formation in alcoholic fermentation,” in Research in Organic Farming, ed. Nokkoul R. (London: IntechOpen; ). [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemzadeh A., Jaafar H. Z. E., Karimi E., Ibrahim M. H. (2012). Combined effect of CO2 enrichment and foliar application of salicylic acid on the production and antioxidant activities of anthocyanin, flavonoids and isoflavonoids from ginger. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 12:229. 10.1186/1472-6882-12-229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves B., Falco V., Moutinho-Pereira J., Bacelar E., Peixoto F., Correia C. (2009). Effects of elevated CO2 on grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.): volatile composition, phenolic Content, and in Vitro antioxidant activity of red wine. J. Agric. Food Chem. 57 265–273. 10.1021/jf8020199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouot J. C., Smith J., Holzapfel B., Barril C. (2019a). Single and cumulative effects of whole-vine heat events on Shiraz berry composition. OENO One 53 171–187. 10.20870/oeno-one.2019.53.2.2392 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gouot J. C., Smith J. P., Holzapfel B. P., Walker A. R., Barril C. (2019b). Grape berry flavonoids: a review of their biochemical responses to high and extreme high temperatures. J. Exp. Bot. 70 397–423. 10.1093/jxb/ery392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer D. H., Weedon M. M. (2013). The impact of high temperatures on Vitis vinifera cv. Semillon grapevine performance and berry ripening. Front. Plant Sci. 4:491. 10.3389/fpls.2013.00491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer D. H., Weston C. (2010). Heat stress affects flowering, berry growth, sugar accumulation and photosynthesis of Vitis vinifera cv. Semillon grapevines grown in a controlled environment. Funct. Plant Biol. 37:206 10.1071/fp09209 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y. Y., Yang Y. P., Peng Q., Han Y. (2015). Biogenic amines in wine: a review. Intern. J. Food Sci. Technol. 50 1523–1532. 10.1111/ijfs.12833 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Habran A., Commisso M., Helwi P., Hilbert G., Negri S., Ollat N., et al. (2016). Roostocks/Scion/Nitrogen interactions affectsecondary metabolism in the grape berry. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1134. 10.3389/fpls.2016.01134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbert G., Temsamani H., Bordenave L., Pedrot E., Chaher N., Cluzet S., et al. (2015). Flavonol profiles in berries of wild Vitis accessions using liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometry. Food Chem. 169 49–58. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.07.079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibáñez J., Carreño J., Yuste J., Martínez-Zapater J. M. (2015). “Grapevine breeding and clonal selection programmes in Spain,” in Grapevine Breeding Programs for the Wine Industry, ed. Reynolds A. (Amsterdam: Elsevier Ltd; ), 183–209. 10.1016/B978-1-78242-075-0.00009-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- IPCC (2013). “Climate change 2013: the physical science basis,” in Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, eds Stocker T., Qin D., Plattner G., Tignor M., Allen S., Boschung J., et al. (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; ). [Google Scholar]

- IPCC (2014). “Climate change 2014: mitigation of climate change,” in Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, eds Edenhofer O., Pichs-Madruga Y., Sokona E., Farahani S., Kadner K., Seyboth I., et al. (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; ), 10.1017/CBO9781107415416 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaafar H. Z. E., Ibrahim M. H., Karimi E. (2012). Phenolics and flavonoids compounds, phenylanine ammonia lyase and antioxidant activity responses to elevated CO2 in Labisia pumila (Myrisinaceae). Molecules 17 6331–6347. 10.3390/molecules17066331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones G. V., Davis R. E. (2000). Climate influences on grapevine phenology grape composition, and wine productiona and quality for Bordeaux, France. Am. J. Enol. Viticult. 51 249–261. [Google Scholar]

- Jones G. V., White M. A., Cooper O. R., Storchmann K. (2005). Climate change and global wine quality. Clim. Chang. 73 319–343. 10.1007/s10584-005-4704-4702 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keller M. (2010). Managing grapevines to optimise fruit development in a challenging environment: a climate change primer for viticulturists. Austr. J. Grape Wine Res. 16 56–69. 10.1111/j.1755-0238.2009.00077.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kizildeniz T., Mekni I., Santesteban H., Pascual I., Morales F., Irigoyen J. J. (2015). Effects of climate change including elevated CO2 concentration, temperature and water deficit on growth, water status, and yield quality of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) cultivars. Agric. Water Manag. 159 155–164. 10.1016/J.AGWAT.2015.06.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]