Abstract

Background:

Maternal obesity has been consistently associated with offspring risk for ASD as well as lipid metabolism derangements. However, few ASD studies have examined maternal lipids in conjunction with maternal prepregnancy body mass index (BMI).

Methods:

This nested case-control study was based on the Boston Birth Cohort, a prospective cohort study of mother-child dyads recruited at the Boston Medical Center. Maternal blood samples were collected shortly after delivery and analyzed for total plasma cholesterol, HDL, and triglyceride (TG) concentrations. Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) was subsequently calculated by the Friedewald equation. Cases were identified using ASD diagnoses in children’s medical records. The odds of ASD were estimated with continuous lipid levels for a linear relationship, and we further explored the non-linear relationship using the tertile of each lipid analyte with the highest tertile as the reference group. Logistic regression was used to estimate the risk of ASD adjusting for potential confounders. The analyses were performed separately for mothers with normal weight and overweight/obese based on maternal prepregnancy BMI.

Results:

One standard deviation decrease in postpartum maternal LDL was associated with increased odds of ASD aOR 1.33 [1.03 – 1.75]. There were no association between postpartum maternal HDL and TG levels and ASD risk. Decreasing levels of LDL were not associated with ASD risk in normal weight mothers (aOR 1.18 [0.83 – 1.69]), but the ASD risk was more pronounced in overweight and obese mothers (aOR 1.54 [1.04 – 2.27]). Follow-up analysis of non-linear association models showed that, when compared to the highest tertile, lower maternal LDL concentrations were associated with approximately two times increased risk of ASD (first tertile: aOR 2.34 [1.22 – 4.49] and second tertile: aOR 2.63 [1.37 – 5.08]). A similar pattern was observed with overweight/obese mothers but not in normal weight mothers

Conclusion:

Lower maternal postpartum plasma LDL concentration was associated with increased odds of ASD in offspring among children born to overweight and obese mothers. Our findings suggest that both maternal BMI and lipids should be considered in assessing their role in offspring ASD risk; and additional longitudinal studies are needed to better understand maternal lipid dynamics during pregnancy among normal weight and overweight/obese mothers.

Keywords: Maternal prepregnancy BMI, lipid, autism

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a pervasive developmental disorder with a wide spectrum of disease severity. It is mainly characterized by impairments in social interaction, verbal and nonverbal communication, as well as restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior, interest, or activities (1). The etiology of ASD is not completely understood, but increasing evidence suggests that the development of ASD is influenced by both a genetic predisposition as well as environmental triggers during vulnerable periods of neurologic development (2). The exposure window that leads to an increased risk of developing ASD is hypothesized to extend well before birth. Several antenatal risk factors have been associated with ASD development, including diabetes, pre-eclampsia, and prepregnancy maternal obesity (3–5). The mechanistic pathway by which these conditions lead to ASD is still unclear. As a result, interventions and preventive strategies during the antenatal period are currently limited.

Maternal obesity may be one of the more common maternal risk factors associated with the development of ASD in the offspring (3,6). Nearly one-third of all reproductive-age women in the United States are obese (7,8). Given the high prevalence of obesity, a complete understanding of the pathophysiology in the obese gravida leading to ASD development is crucial in future endeavors aimed at reducing the risk of ASD. Existing data have shown that obesity leads to a chronic proinflammatory state (9,10). These inflammatory markers have been independently associated with higher ASD risk (11,12). However, maternal obesity may predispose to the development of ASD through other concurrent pathways that have yet to be explored.

Obesity is associated with deranged lipid metabolism. In non-pregnant adults, obesity is linked to higher levels of both low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL). During pregnancy, most maternal plasma lipid levels increase to meet the higher physiologic demands of rapid fetal growth (13,14). Lipid levels peak in the late third trimester, corresponding to the timing of a rapid increase in fetal growth and brain mass (15). Recent studies have shown that in obese women, the rate of LDL increase over pregnancy is reduced. In obese women, LDL and VLDL are higher in the first trimester but increase at a lower rate when compared to normal weight women (13,16,17).

An adequate supply of essential fatty acids and cholesterol is crucial for the development of the fetal nervous system (18). We hypothesize that the blunted lipid response to pregnancy in obese pregnant women results in abnormal brain development and thus, a higher risk of ASD in offspring. The purpose of this study is to determine the association between maternal postpartum lipid profile and child ASD risk using a nested case-control study design.

Materials and Methods

Study population

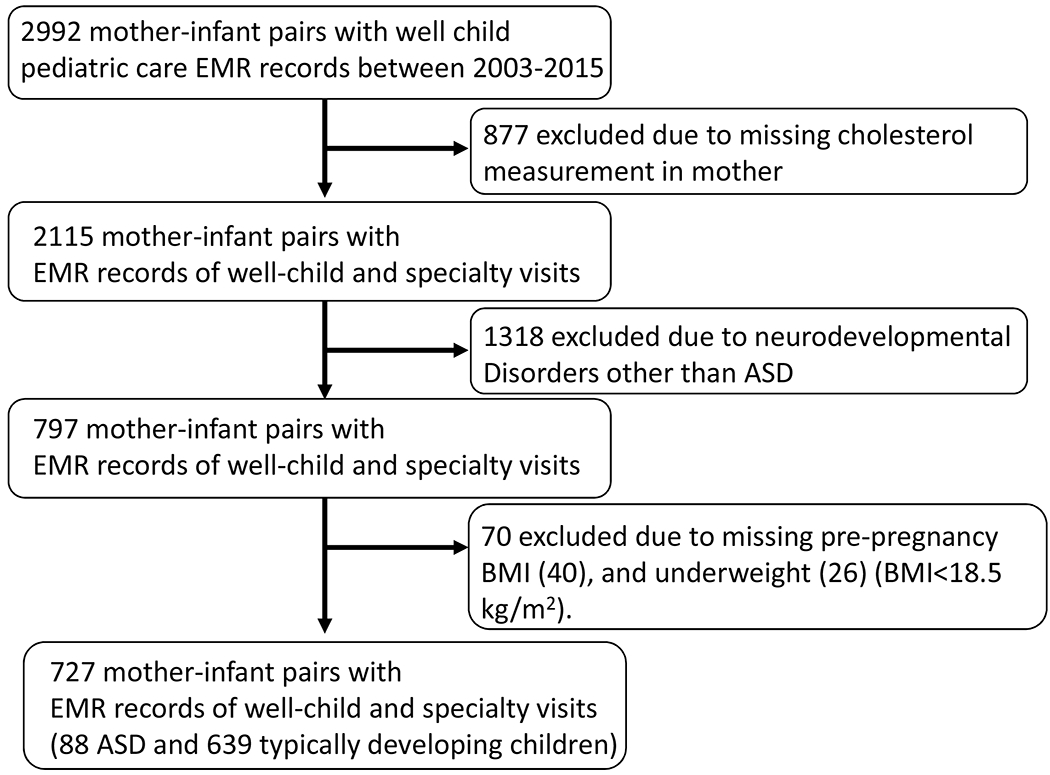

Study participants included mother-child dyads enrolled in the Boston Birth Cohort (BBC), at the Boston Medical Center (BMC). The BBC was established in 1998 to investigate the environmental and genetic determinants of preterm delivery with oversampling of preterm births. Given that preterm birth is a known risk factor for ASD, the BBC had a high prevalence of ASD within the cohort. A detailed study recruitment procedure for the BBC has been published previously (19,20). Briefly, women with a singleton live birth at the BMC were eligible for recruitment. Pregnancies as a result of in vitro fertilization or complicated by multiple gestations, chromosomal abnormalities, major birth defects and preterm deliveries due to maternal trauma were excluded. A total of 7,939 mother-child dyads were enrolled in the BBC from 1998 to 2013. Of the enrolled mother-infant dyads from 1998 to 2013, 3,098 pairs continued to receive pediatric care at the BMC and were included in the postnatal follow-up study (3,21). A previous study showed no major differences in baseline study participant demographics and clinical characteristics between those with postnatal follow-up data and those lost to follow-up (3). After obtaining informed consent, a face-to-face structured interview with the mother was conducted by trained study personnel to collect data on socio-demographic factors, lifestyle, diets, and home environment. Starting in 2003, the cohort received funding to follow developmental outcomes of the children enrolled in the study who continued to seek pediatric care at BMC. In the present study, 2992 mother-child dyads who had pediatric follow-up at the BMC through September 31, 2015 (the last date before transitioning from International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) to ICD-10-CM) with complete diagnosis lists were obtained from electronic medical records (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the sample included in the analyses.

Measurement of exposure and outcome

Maternal non-fasting blood samples were obtained between 24 hours to 72 hours after delivery. 877 mother-child dyads missing maternal cholesterol measurements were excluded. Those who did not provide the blood sample were more likely to be typically developing, White, a female child, have lower birthweight, and have smaller gestational. Maternal serum total cholesterol (CHOL), triglyceride (TG), and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) were measured from one lab using a standardized protocol. CHOL, TG, and HDL levels were used to calculate low-density lipoprotein (LDL) reported in mg/dL using the Friedewald equation as described in Zhang et al. (22). The ratio between LDL and HDL levels are frequently used to assess cardiovascular risk and was included in the analysis for comparison. Commonly used clinical cut-off levels for low HDL and high LDL are <50 mg/dL and >200mg/dL respectively (23). However, these clinical cut-offs are based on non-pregnant female values and were developed for cardiovascular risk assessment. We examined tertile cut-offs to explore the non-linear relationship between maternal lipid levels and ASD risk.

ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes were used for pediatric inpatient, outpatient, and emergency room visits to the BMC between October 11, 2003, and September 31, 2015(the last date before the transition from ICD-9-CM to ICD-10-CM) to identify ASD cases and neurotypical controls. 118,939 EMR records from 2,992 unique children were obtained to determine children with neurodevelopmental outcomes. A child was classified as an ASD case if the EMR contained one or more of the following ICD-9-CM codes: 299.00 (autism), 299.80 (Asperger syndrome), 299.81, 299.90/299.91 (pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified). Neurotypical controls were defined as not having any of the following conditions: ASD, attention deficit hyperactive disorder, intellectual disability, developmental delay, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, or congenital anomalies. The method of case-control identification used in this study has previously been established by clinical experts and has been applied by prior manuscripts (21,24). Children with physician-diagnosed neurodevelopmental disorders other than ASD (n=1318) using the ICD-9-CM were excluded from the analysis.

Maternal prepregnancy weight and height were collected in the maternal postpartum interview and were used to calculate prepregnancy BMI. Maternal prepregnancy BMI was further categorized into two BMI categories, including normal weight (BMI>18.5 and ≤24.9 kg/m2) and overweight/obese (BMI ≥25.0 kg/m2). The overweight and obese groups were combined based on literature that indicate distinctive pregnancy lipid profiles between normal and overweight/obese mothers (13,16,17). Subjects were excluded if prepregnancy BMI was missing (n=44) or underweight (BMI <18.5 kg/m2, n=26) because the primary objective of this study was to determine the effects of maternal obesity and lipid levels on ASD risk. Final study subjects included 88 ASD cases and 639 neurotypical controls (Figure 1). Sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the misclassification of ASD diagnosis using EMR data. In the sensitivity analysis, we applied a more stringent ASD case definition with at least two separate EMR diagnosis of 299 ICD-9-CM codes (62 ASD cases met the more stringent criteria).

Statistical Analysis

Study participant characteristics were compared between neurotypical controls and ASD cases using t-test for continuous variables and χ2 test for categorical variables. Lipid levels were compared across the two BMI categories (normal weight and overweight/obese) using t-tests. Maternal plasma lipids were all normally distributed and linear associations with risk of ASD were determined using multivariate logistic regression models. Multivariate models were adjusted for covariates (gestational age, breastfeeding status, maternal race, sex, maternal prepregnancy BMI, maternal age, birth weight, delivery type, pre-gestational diabetes, and gestational diabetes) determined a priori based on literature. Effect modification by the two BMI categories (normal and overweight/obese) was examined in the stratified analysis as well as multivariate logistic regression models with interaction models.

Abnormal maternal lipid thresholds have yet to be established with respect to ASD risk; therefore lipid measures were further categorized into three groups using the full sample (<33%, 33-66%, >66%) to examine non-linear associations. The following cut off points were used in the non-linear models: HDL (<54 mg/dL, 54-67 mg/dL, >67 mg/dL), TG (<149 mg/dL, 149-212 mg/dL, >212 mg/dL) and LDL (<107 mg/dL, 107-125 mg/dL, >125 mg/dL). The reference group was set as the highest tertile to reflect normal late pregnancy lipid levels based on prior literature (25). The interaction between each lipid tertile and BMI category was tested using an interaction term in separate logistic regression models. All analysis was performed with R-3.1.3. This study was approved by both Boston University Medical Center (BUMC) and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Internal Review Board (IRB) and informed consent was obtained from all participants in accordance with BUMC IRB approved protocol and consent forms.

Results

Compared to neurotypical children, ASD children were more likely to be male, have an older mother with higher BMI, more likely to be delivered through cesarean section (C-section), and have lower birth weight (Table 1). Maternal postpartum total cholesterol (P=0.03) and LDL (P=0.01) levels were significantly lower among mothers with ASD children compared to neurotypical controls. The mean maternal postpartum CHOL and LDL concentrations were also lower among overweight and obese mothers compared to the normal weight mothers (Table 2). The mean HDL was higher in normal weight mothers, and the TG level did not differ across BMI categories (Table 2).

Table 1.

Study participant characteristics among typical development (TD) and autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

| TD (n=639)¶ | ASD (n=88) | P† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Sex | |||

| Female | 370 (57%) | 20 (23%) | <0.001 |

| Male | 269 (42%) | 68 (77%) | |

| Race | |||

| White | 32 (5%) | <10 (7%) | |

| Black | 397 (62%) | 55 (62%) | 0.86 |

| Hispanic | 168 (26%) | 23 (26%) | |

| Others | 37 (6%) | <10 (5%) | |

| Education^ | |||

| High school or less | 398 (62%) | 52 (59%) | 0.52 |

| College or more | 237 (36%) | 36 (41%) | |

| Breastfeeding Status ≠ | |||

| Bottle-fed | 153 (24%) | 19 (22%) | 0.73 |

| Breastfed | 470 (74%) | 67 (76%) | |

| Delivery Type^ | |||

| Vaginal | 438 (69%) | 50 (57%) | 0.02 |

| C-section | 197 (31%) | 38 (43%) | |

| Gestational age, week‡ | |||

| Mean (SD) | 38.6 (2.5) | 37.6 (3.8) | 0.08 |

| Birthweight, g | |||

| Mean (SD) | 3096 (666.2) | 2915 (829.0) | 0.05 |

| Maternal age | |||

| Mean (SD) | 28.0 (6.4) | 30.5 (6.5) | 0.001 |

| Maternal BMI, kg/m3 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 26.7 (6.7) | 28.3 (7.2) | 0.05 |

| Maternal CHOL, mg/dL § | |||

| Mean (SD) | 226.2 (63.7) | 211.8 (57.1) | 0.03 |

| Maternal TG, mg/dL § | |||

| Mean (SD) | 193.1 (81.8) | 194.1 (78.0) | 0.9 |

| Maternal HDL, mg/dL^^ | |||

| Mean (SD) | 63.4 (18.6) | 60.2 (15.4) | 0.08 |

| Maternal LDL, mg/dL | |||

| Mean (SD) | 131.0 (42.9) | 119.6 (38.4) | 0.01 |

Chi square test was used for categorical variables (except for race where Fisher’s exact test was used) and t test was used for continuous variables (except for gestational age where Wilcoxon rank sum test was used).

n=635 for TD

n=623 for TD; n=86 for ASD

n=638 for TD; n=87 for ASD

n=638 for TD

n=637 for TD

Typically developing children: Neurotypical controls defined as those never diagnosed with ASD, attention deficit hyperactive disorder, intellectual disability, developmental delay, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder or congenital anomalies, based on ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes.

Table 2.

Maternal postpartum lipid levels by maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI).

| Normal weight (BMI>18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2) n=352 | Overweight/Obese† (BMI≥25 kg/m2) n=375 | t-test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ±SD | Mean ±SD | P | |

| CHOL (mg/dL) | 230±66 | 218±59 | 0.01 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 198 ± 84 | 188 ±78 | 0.09 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 65 ± 19 | 62 ±18 | 0.04 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 133 ± 45 | 126 ±40 | 0.03 |

| LDL/HDL ratio | 2.15 ± 0.73 | 2.12 ± 0.67 | 0.57 |

n=374 for CHOL and TG; n=373 for HDL

CHOL=cholesterol, LDL=low density lipoprotein, HDL=high density lipoprotein, TG=triglyceride

A decrease in maternal postpartum lipid LDL was associated with higher odds of ASD in the offspring. Specifically, one standard deviation decrease in maternal postpartum LDL level was associated with 1.35 times (95% CI [1.04 – 1.75]) the odds of ASD in the offspring (Table 3). No linear association was observed among maternal postpartum HDL level, TG level or LDL/HDL ratio, and odds of ASD in the child (Table 3). Stratifying by maternal prepregnancy BMI categories, normal and overweight/obese, showed an association between decreasing postpartum LDL level and ASD odds among children of overweight/obese mothers (aOR 1.54 [1.03 – 2.27]) but not normal mothers (aOR 1.2 [0.83 – 1.75]) (Table 3). Normal weight mothers showed decreased odds of ASD with decreasing TG level (aOR 0.65 [0.44 – 0.94]) but not in overweight/obese mothers. Interaction models examining interactions between each lipid measure (CHOL, LDL, HDL, TG, and LDL/HDL) and BMI category (normal and overweight/obese) did not show any statistical evidence of interactions (P=0.76, 0.54, 0.79, 0.19,0.52, respectively).

Table 3.

Adjusted odds ratio of ASD in child and continuous maternal postpartum lipid level.

| All subjects† | Normal (BMI≥24.9kg/m2)‡ | Overweight/Obese (BMI≥25 kg/m2)§ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR [95% CI] | OR [95% CI] | OR [95% CI] | ||

| CHOL (mg/dL) | 1 SD decrease | 1.25 [0.97 - 1.64] | 1.12 [0.78 - 1.64] | 1.35 [0.91 - 2.00] |

| TG (mg/dL) | 1 SD decrease | 0.91 [0.7 - 1.19] | 0.65 [0.44 - 0.94] | 1.18 [0.78 - 1.75] |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 1 SD decrease | 1.15 [0.89 - 1.47] | 1.15 [0.76 - 1.72] | 1.09 [0.78 - 1.54] |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 1 SD decrease | 1.35 [1.04 - 1.75] | 1.2 [0.83 - 1.75] | 1.54 [1.03 - 2.27] |

| LDL/HDL | 1 unit decrease in ratio | 1.37 [0.93 - 2.04] | 1.2 [0.67 - 2.04] | 1.64 [0.93 - 2.86] |

n=693 for CHOL and TG, n=692 for HDL; n=694 for LDL

n=329 for CHOL, TG, HDL and LDL

n=340 for CHOL and TG, n=339 for HDL; n=341 for LDL

Adjusted for gestational age, breastfeeding status, maternal race, sex, maternal pre-pregnancy BMI, maternal age, birthweight, delivery type, pre-gestational diabetes and gestational diabetes. CHOL=cholesterol, LDL=low density lipoprotein, HDL=high density lipoprotein, and TG=triglyceride

Non-linear associations between maternal lipid levels and offspring ASD risk were further examined by applying tertiles cut-offs to the lipid levels. Among all subjects, children born to mothers with postpartum LDL lower than 107 mg/dL (1st tertile) were associated with 2.49 times [1.27 – 4.87] the odds of ASD compared to those who were born to mothers with postpartum LDL level >125 mg/dL (3rd tertile) after adjusting for covariates (Table 4). Similarly, children born to mothers with postpartum LDL between 107 and 125 mg/dL (2nd tertile) were associated with 2.79 times [1.42 – 5.48] the odds of ASD compared to those who were born to mothers with postpartum LDL level >125 mg/dL (3rd tertile) after adjusting for covariates (Table 4). Further stratification by maternal prepregnancy BMI categories showed that the maternal postpartum LDL level was associated with increased risk of ASD in the children of overweight/obese mothers (1st tertile: aOR 4.61 [1.51-14.0], 2nd tertile: aOR 5.94 [1.96-18.0]) but not in normal weight mothers (1st tertile: aOR 1.64 [0.65-4.12], 2nd tertile: aOR 1.37 [0.52-3.65]) (Table 4). Interaction models examining interactions between each lipid tertiles (LDL, HDL, TG, and LDL/HDL) and BMI category (normal and overweight/obese) did show statistical evidence of interaction in LDL (1st tertile: P=0.07, 2nd tertile: P=0.04). It is important to note that the number of subjects in the 3rd tertile was limited in the overweight/obese group leading to increased variability in the estimate. Among normal weight mothers, maternal postpartum TG level lower than 149 mg/dL (1st tertile) was associated with decreased risk of ASD compared to mothers with TG level higher than 212 mg/dL (3rd tertile). No evidence of a non-linear association between maternal postpartum HDL and concentration and odds of ASD was observed in normal weight mothers or overweight/obese mothers. Sensitivity analysis of Table 4 using more stringent ASD diagnostic criteria attenuated the magnitude of the association slightly but did not impact the directionality or statistical significance (Table S1).

Table 4.

Examining non-linear relationship using adjusted odds ratio of ASD in child and maternal postpartum lipid tertiles.

| All subjects† | Normal (BMI≤24.9kg/m2)‡ | Overweight/Obese (BMI≥25 kg/m2)§ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR [95% CI] | OR [95% CI] | OR [95% CI] | ||

| HDL tertiles | <54 mg/dL | 1.42 [0.77 - 2.62] | 1.32 [0.51 - 3.38] | 1.44 [0.6 - 3.45] |

| 54 −67 mg/dL | 1.13 [0.61 - 2.11] | 1.0 [0.4 - 2.49] | 1.43 [0.58 - 3.53] | |

| 67+ mg/dL (REF) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| TG tertiles | <149 mg/dL | 0.78 [0.42 - 1.45] | 0.33 [0.12 - 0.92] | 1.35 [0.55 - 3.29] |

| 149 −212 mg/dL | 0.66 [0.35 - 1.24] | 0.44 [0.17 - 1.13] | 0.90 [0.36 - 2.28] | |

| 212+ mg/dL (REF) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| LDL tertiles | <107 mg/dL | 2.49 [1.27 - 4.87] | 1.64 [0.65 - 4.12] | 4.61 [1.51 - 14.0] |

| 107-125 mg/dL | 2.79 [1.42 - 5.48] | 1.37 [0.52 - 3.65] | 5.94 [1.96 - 18.0] | |

| 125+ mg/dL (REF) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

n=693 for TG, n=692 for HDL; n=694 for LDL

n=329 for TG, HDL and LDL

n=340 for TG, n=339 for HDL; n=341 for LDL

Adjusted for gestational age, breastfeeding status, maternal race, sex, maternal pre-pregnancy BMI, maternal age, birthweight, delivery type, pre-gestational diabetes and gestational diabetes. LDL=low density lipoprotein, HDL=high density lipoprotein, and TG=triglyceride

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated an inverse association between maternal postpartum plasma LDL and the risk of ASD. The increase of ASD risk with decreasing LDL was observed in overweight/obese mothers, but not in normal weight mothers. However, we found no interaction between LDL and prepregnancy obesity with ASD risk. Maternal late pregnancy lipid levels, as estimated by postpartum lipid levels in this study, may play a role in the complex etiology of ASD. This is the first study to observe an adverse effect of lower maternal postpartum LDL levels on ASD risk.

This observed inverse association between LDL concentration and ASD may be a result of abnormal maternal lipid regulation in obese gravidas. Under physiologic pregnancy conditions, the placental production of estrogen progressively increases with gestational age (26). The rise in estrogen suppresses peripheral lipoprotein lipase activities (15). There is a concurrent increase in lipolytic activity from adipose tissue due to the development of insulin resistance. This results in a gradual increase in LDL concentrations in maternal plasma as the pregnancy progresses (13,27,28). The increase in LDL concentration ensures the delivery of essential fatty acids, such as omega-3 fatty acids, to the fetus during critical periods of neurodevelopment. The association between omega-3 fatty acids and ASD risk has been inconclusive. A Nurse’s Health Study using a food frequency questionnaire observed increasing ASD risk with lower omega-3 fatty acid in the maternal prenatal diet (29). Another large population-based European study showed no association between omega-3 fatty acid measured in mid-pregnancy venous blood and autistic traits (30). The shunting of cholesterol and fatty acids from maternal to fetal compartment was demonstrated by studies showing increased production of apoB-100 lipoprotein in the placenta and a 7-12% increase in LDL, HDL and cholesterol concentrations in the umbilical vein compared to umbilical artery blood samples (31,32). Animal studies have shown that deficiencies in these essential nutrients can result in aberrant neuron morphology in the brain (33,34).

The pathologic plasma lipid response to pregnancy in women with increased BMI has been observed in several studies (13,14). However, the underlying mechanism is unclear. One study using rodent fetal growth restriction and maternal high fat diet model demonstrated an increase in maternal hepatic LDL receptor activity, leading to hepatic accumulation of cholesterol and lipids and a decrease in maternal serum lipid profile (35). The study created a fetal growth restriction model by uterine artery ligation to restrict placental development. The findings from this study suggest that healthy placental development is crucial in the regulation of maternal plasma lipid concentration.

The lack of association between LDL concentration and ASD in normal weight pregnancies indicates that in addition to plasma lipid regulation, other crucial steps in lipid metabolism processes are affected by maternal obesity. There is evidence of increased accumulation of oxidized LDL particles in the human placenta in the setting of oxidative stress as seen in pregnancies complicated by maternal obesity (36–38). Oxidized LDL particles are not recognized by LDL receptors and accumulate in the placenta. As a result, placental cholesterol and fatty acid transport capacity to the fetal compartment is reduced, and placental inflammatory response increased (38,39). This may result in the observed increase in ASD risk due to deficiencies in important substrates for fetal neurodevelopment. Additional studies should further evaluate this pathway and assess the potential benefits of cholesterol and essential fatty acid supplementation during this critical neurodevelopmental phase.

The results of this study were based on a predominantly urban, low-income minority cohort and provide a unique opportunity to examine the association between maternal lipids with ASD risk. However, our findings may not be generalizable to the overall population. Those who did not agree to blood sample collection were different in demographic and clinical characteristics and we cannot rule out the potential selection bias. Also, the study was limited to lipid levels from maternal plasma collected 24-72 hours after birth which are lower than late pregnancy levels but have been shown to correlate (25). Postpartum maternal plasma lipid levels could also be influenced by factors such as breastfeeding, however, our adjusted analysis showed that breastfeeding did not confound the association between maternal postpartum lipid levels and ASD. Further study of maternal lipid levels during late pregnancy is needed. Mothers were also not asked to fast prior to the blood draw during study recruitment, and thus data of our study reflects non-fasting lipid levels. Non-fasting samples primarily impact total cholesterol and TG levels, which may be higher in fasting state. However, recent studies illustrate that lipids level changes between the fasting and non-fasting state are moderate under habitual consumption and LDL and HDL are less affected (40).

Despite these limitations, this study raises new questions regarding the role of lipid regulation in fetal neurodevelopment. Previous studies have demonstrated the importance of cholesterol and essential fatty acids in fetal neurodevelopment. This study is the first to show an association between maternal plasma lipid concentration and offspring postnatal neurodevelopmental complications. Maternal lipids can be easily measured and are potentially modifiable. Our findings suggest lipids could play a role in the complex etiology of some cases of ASD, and further studies are needed to confirm our findings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement:

The Boston Birth Cohort, the parent study, is supported in part by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under grant number R40MC27443, Autism Field-initiated Innovative Research Studies Program; and grant number UJ2MC31074, Autism Single Investigator Innovation Program; and by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants (R01HD086013, 2R01HD041702, and R01HD098232). This information or content and conclusions are those of the authors and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS or the U.S. Government. The funding agencies had no involvement in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- 1.Am. Psychiatr. Assoc. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: Am. Psychiatr. Publ; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Risch N, Hoffmann TJ, Anderson M, Croen LA, Grether JK, Windham GC. Familial recurrence of autism spectrum disorder: evaluating genetic and environmental contributions. Am J Psychiatry. 2014/06/28. 2014;171(11):1206–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li M, Fallin MD, Riley A, Landa R, Walker SO, Silverstein M, et al. The Association of Maternal Obesity and Diabetes With Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. Pediatrics. 2016/01/31. 2016;137(2):e20152206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walker CK, Krakowiak P, Baker A, Hansen RL, Ozonoff S, Hertz-Picciotto I. Preeclampsia, placental insufficiency, and autism spectrum disorder or developmental delay. JAMA Pediatr. 2014/12/09. 2015;169(2):154–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guinchat V, Thorsen P, Laurent C, Cans C, Bodeau N, Cohen D. Pre-, peri- and neonatal risk factors for autism. Acta Obs Gynecol Scand. 2011/11/17. 2012;91(3):287–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lyall K, Croen L, Daniels J, Fallin MD, Ladd-Acosta C, Lee BK, et al. The Changing Epidemiology of Autism Spectrum Disorders. Annu Rev Public Health [Internet]. 2017. March 20;38(1):81–102. Available from: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA. 2014. February;311(8):806–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2015: With Special Feature on Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2015;107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faucett AM, Metz TD, DeWitt PE, Gibbs RS. Effect of Obesity on Neonatal Outcomes in Pregnancies with Preterm Premature Rupture of Membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;(November):1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fain JN. Release of inflammatory mediators by human adipose tissue is enhanced in obesity and primarily by the nonfat cells: A review. Mediators Inflamm. 2010;2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones KL, Croen LA, Yoshida CK, Heuer L, Hansen R, Zerbo O, et al. Autism with intellectual disability is associated with increased levels of maternal cytokines and chemokines during gestation. Mol Psychiatry. 2016/05/25. 2016; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goines PE, Croen LA, Braunschweig D, Yoshida CK, Grether J, Hansen R, et al. Increased midgestational IFN-gamma, IL-4 and IL-5 in women bearing a child with autism: A case-control study. Mol Autism. 2011/08/04. 2011;2:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farias DR, Franco-Sena AB, Vilela A, Lepsch J, Mendes RH, Kac G. Lipid changes throughout pregnancy according to prepregnancy BMI: results from a prospective cohort. BJOG. 2016. March;123(4):570–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bozkurt L, Göbl CS, Hörmayer A-T, Luger A, Pacini G, Kautzky-Willer A. The impact of preconceptional obesity on trajectories of maternal lipids during gestation. Sci Rep. 2016. July;6:29971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cetin I, Alvino G, Cardellicchio M. Long chain fatty acids and dietary fats in fetal nutrition. J Physiol. 2009. July;587(Pt 14):3441–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vahratian A, Misra VK, Trudeau S, Misra DP. Prepregnancy body mass index and gestational age-dependent changes in lipid levels during pregnancy. Obs Gynecol. 2010/06/23. 2010;116(1):107–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bozkurt L, Gobl CS, Hormayer AT, Luger A, Pacini G, Kautzky-Willer A. The impact of preconceptional obesity on trajectories of maternal lipids during gestation. Sci Rep. 2016/07/21. 2016;6:29971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang C-Y, Ke D-S, Chen J-Y. Essential fatty acids and human brain. Acta Neurol Taiwan. 2009. December;18(4):231–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X, Zuckerman B, Pearson C, Kaufman G, Chen C, Wang G, et al. Maternal cigarette smoking, metabolic gene polymorphism, and infant birth weight. Jama. 2002/01/12. 2002;287(2):195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang G, Divall S, Radovick S, Paige D, Ning Y, Chen Z, et al. Preterm Birth and Random Plasma Insulin Levels at Birth and in Early ChildhoodPreterm Birth and Random Plasma Insulin Levels at Birth and in Early ChildhoodPreterm Birth and Random Plasma Insulin Levels at Birth and in Early Childhood. JAMA [Internet]. 2014. February 12;311(6):587–96. Available from: 10.1001/jama.2014.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brucato M, Ladd-Acosta C, Li M, Caruso D, Hong X, Kaczaniuk J, et al. Prenatal exposure to fever is associated with autism spectrum disorder in the boston birth cohort. Autism Res. 2017. August; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang S, Liu X, Necheles J, Tsai H-J, Wang G, Wang B, et al. Genetic and environmental influences on serum lipid tracking: a population-based, longitudinal Chinese twin study. Pediatr Res. 2010;68(4):316–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Program NCE. (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blo. Circulation. 2002;106(25):3143–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ji Y, Riley AW, Lee L-C, Volk H, Hong X, Wang G, et al. A prospective birth cohort study on maternal cholesterol levels and offspring attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: New insight on sex differences. Brain Sci. 2018;8(1):3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montelongo A, Lasuncion MA, Pallardo LF, Herrera E. Longitudinal study of plasma lipoproteins and hormones during pregnancy in normal and diabetic women. Diabetes. 1992. December;41(12):1651–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levitz M, Young BK. Estrogens in pregnancy. Vitam Horm. 1977;35:109–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pusukuru R, Shenoi AS, Kyada PK, Ghodke B, Mehta V, Bhuta K, et al. Evaluation of Lipid Profile in Second and Third Trimester of Pregnancy. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016. March;10(3):QC12–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haque S, Muttalib MA, Rahman MM, Islam MA, Haque N, Haque N, et al. Comparison of Low Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Level in Second and Third Trimester of Pregnancy in Mymensingh Region of Bangladesh. Mymensingh Med J. 2016. October;25(4):717–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lyall K, Munger KL, O’Reilly ÉJ, Santangelo SL, Ascherio A. Maternal Dietary Fat Intake in Association With Autism Spectrum Disorders. Am J Epidemiol [Internet]. 2013. June 27;178(2):209–20. Available from: 10.1093/aje/kws433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steenweg-de Graaff J, Tiemeier H, Ghassabian A, Rijlaarsdam J, Jaddoe VW V, Verhulst FC, et al. Maternal Fatty Acid Status During Pregnancy and Child Autistic Traits: The Generation R Study. Am J Epidemiol [Internet]. 2016. April 6;183(9):792–9. Available from: 10.1093/aje/kwv263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Madsen EM, Lindegaard MLS, Andersen CB, Damm P, Nielsen LB. Human placenta secretes apolipoprotein B-100-containing lipoproteins. J Biol Chem. 2004. December;279(53):55271–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parker CR, Deahl T, Drewry P, Hankins G. Analysis of the potential for transfer of lipoprotein-cholesterol across the human placenta. Early Hum Dev. 1983. October;8(3–4):289–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahmad A, Moriguchi T, Salem N. Decrease in neuron size in docosahexaenoic acid-deficient brain. Pediatr Neurol. 2002. March;26(3):210–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jeffrey BG, Neuringer M. Age-related decline in rod phototransduction sensitivity in rhesus monkeys fed an n-3 fatty acid-deficient diet. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009. September;50(9):4360–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zinkhan EK, Zalla JM, Carpenter JR, Yu B, Yu X, Chan G, et al. Intrauterine growth restriction combined with a maternal high-fat diet increases hepatic cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein receptor activity in rats. Physiol Rep. 2016. July;4(13). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saben J, Lindsey F, Zhong Y, Thakali K, Badger TM, Andres A, et al. Maternal obesity is associated with a lipotoxic placental environment. Placenta. 2014. March;35(3):171–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malti N, Merzouk H, Merzouk SA, Loukidi B, Karaouzene N, Malti A, et al. Oxidative stress and maternal obesity: feto-placental unit interaction. Placenta. 2014. June;35(6):411–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pecks U, Rath W, Caspers R, Sosnowsky K, Ziems B, Thiesen H-J, et al. Oxidatively modified LDL particles in the human placenta in early and late onset intrauterine growth restriction. Placenta. 2013. December;34(12):1142–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levitan I, Volkov S, Subbaiah P V. Oxidized LDL: diversity, patterns of recognition, and pathophysiology. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010. July;13(1):39–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nordestgaard BG, Langsted A, Mora S, Kolovou G, Baum H, Bruckert E, et al. Fasting is not routinely required for determination of a lipid profile: clinical and laboratory implications including flagging at desirable concentration cut-points-a joint consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society and European Federa. Eur Hear J. 2016/04/29. 2016;37(25):1944–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.