Elevated lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] is an independent risk factor for coronary heart disease, ischemic stroke, and calcific aortic valve stenosis. Mediated by the LPA gene, elevated Lp(a) is the most common inherited dyslipidemia affecting ~20% of individuals.1 Lp(a) levels ≥50 mg/dL (≈125 nmol/L) correspond to the 80th percentile and represent the threshold at which its impact on atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) becomes clinically meaningful.2 Given its genetic underpinnings, levels of Lp(a) are relatively stable throughout an individual’s lifetime and likely contribute to an accumulating risk starting from a young age.3

Current American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines view a family history of premature ASCVD as a relative indication for measuring Lp(a).4 When measured, elevated levels may be considered a “risk-enhancing” factor, thereby favoring statin discussion and/or initiation in individuals with borderline (5% to <7.5%) and intermediate (≥7.5% to <20%) calculated ASCVD scores, respectively.4 However, there are limited data to support these recommendations. Accordingly, understanding the concordance between the calculated ASCVD risk, Lp(a) levels, and future ASCVD events – specifically, in individuals who have had a myocardial infarction (MI) at a young age – can provide important insights.

We evaluated the prevalence of elevated Lp(a) among adults who experienced an MI at a young age (≤50 years) within the Partners YOUNG-MI Registry. Briefly, this is a retrospective cohort study conducted between 2000 and 2016 within two academic medical centers in Boston, MA (Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital) and includes patients with a first MI at age ≤50 years. Records were adjudicated by study physicians as previously described using the Third Universal Definition of MI.5 This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Partners HealthCare.

Over the study period, two distinct Lp(a) assays were used as part of routine medical care. The first was the standard immunochemical-based assay with reference ranges <30 mg/dL or <75 nmol/L. Lp(a) values measured via the immunochemical assay reported in nmol/L were divided by 2.5 to obtain uniform units of mg/dL. The second assay was a clinically validated electrophoretic assay measuring the cholesterol content of Lp(a) particles with a reference range <3 mg/dL.6,7 Prior analytic work has demonstrated that this electrophoretic cholesterol assay has a strong correlation with the standard immunochemical-based assay, with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.89 to 0.96.6,7 We calculated each patient’s 10-year ASCVD risk prior to their MI using the Pooled Cohort Equations8 based on data available within their medical record.

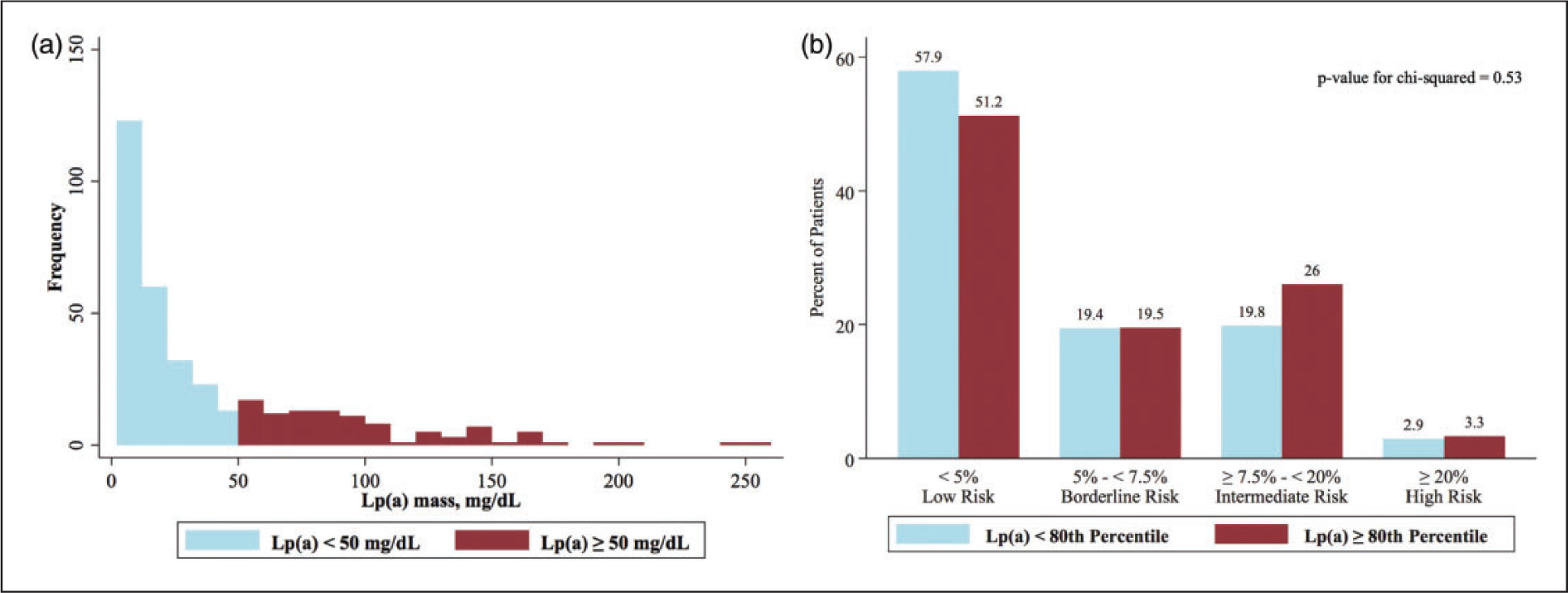

Of 2097 patients (median age 45±3; 19% female) who experienced an MI at a young age, Lp(a) was measured in 441 (21%). Individuals who had their Lp(a) tested were younger (median age difference of two years, p < 0.001) and more likely to have a family history of premature ASCVD (33% vs 25%, p < 0.001). Only 20 patients had their Lp(a) tested prior to their MI. Among the 352 adults whose Lp(a) was assessed using the immunochemical assay, 101 (29%) had levels ≥50 mg/dL, corresponding to the 80th percentile in the general population (Figure 1). Of the remaining 89 individuals whose Lp(a) was measured with the electrophoretic cholesterol assay, 31 (35%) had levels ≥6.9 mg/dL, representing the ~85th percentile.6 Notably, 71% of patients with Lp(a) levels ≥80th percentile had ASCVD risk scores <7.5% prior to their MI (Figure 1). Moreover, even when the ASCVD risk was recalculated by assigning an age of 50 for all patients to account for the impact of young age on ASCVD estimates, 55% of patients with elevated Lp(a) still had ASCVD scores <7.5%. Finally, among the 132 patients with elevated Lp(a), 84 (64%) had no family history of premature ASCVD.

Figure 1.

Distribution of Lp(a) and ASCVD risk scores in adults who experience an MI at a young age (≤50 years). (a) Distribution of Lp(a) assay: 101 out of 352 (29%) patients who underwent the standard immunochemical-based assay had Lp(a) levels ≥50 mg/dL, corresponding to the 80th percentile in the general population. (b) ASCVD risk and Lp(a) level: 71% of patients with Lp(a) levels ≥80th percentile had ASCVD risk scores < 7.5% prior to their MI, thereby demonstrating that there is no association between the calculated ASCVD risk and levels of Lp(a).

In summary, Lp(a) was assessed in only 20% of patients experiencing an MI at a young age. Notably, when Lp(a) was measured, nearly one in three patients had levels ≥80th percentile, yet 71% of these individuals were categorized as low (<5%) or borderline risk (5% to <7.5%) by the ASCVD calculator. Unlike the European Society of Cardiology guidelines which recommend Lp(a) measurement at least once in each person’s lifetime,9 US guidelines suggest measuring Lp(a) only in select patients, categorizing elevated levels as a “risk enhancer.”4 Given that elevated Lp(a) confers a lifetime risk of ASCVD and that 71% of patients in our cohort with elevated levels had ASCVD risk scores <7.5% prior to their MI, our data suggest that the calculated ASCVD risk should not factor into whether a patient – especially those under 50 – is screened for elevated Lp(a). This is especially important given the need for precise ASCVD risk prediction and targeted interventions in both primary and secondary prevention for younger patient populations.10–13

There are two notable limitations of our study. First, we found differences between individuals who had their Lp(a) tested (n = 441) and those who did not (n = 1656), with those who were tested having a younger age and a higher likelihood of having a family history of premature ASCVD. However, these differences were clinically small and are unlikely to meaningfully bias our results. Second, there were two distinct assays used to measure Lp(a) over the study period, which could, in theory, decrease the internal and external validity of our work. However, both assays have been clinically validated in population-based studies and are strongly correlated with one another.6,7

In addition to highlighting that the calculated ASCVD risk should not be used to determine the need for Lp(a) screening, our data further demonstrate that there is a significant deficiency in Lp(a) testing among those who experience an MI at a young age. Addressing this deficiency in Lp(a) testing in high-risk individuals will be particularly important if treatments in current trials14 demonstrate efficacy in secondary prevention. Additional investigation is needed to identify individuals who would benefit most from Lp(a) assessment – and, ultimately, treatment – prior to the development of ASCVD events. While awaiting these landmark trials, our findings support the more expansive view of Lp(a) screening espoused by the European Society of Cardiology guidelines to better identify those at increased cardiovascular risk.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr Berman was supported by a T32 postdoctoral training grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grant number T32 HL094301). Dr Divakaran was supported by a T32 postdoctoral training grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grant number T32 HL094301).

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr Deepak L Bhatt discloses the following relationships – Advisory Board: Cardax, Cereno Scientific, Elsevier Practice Update Cardiology, Medscape Cardiology, PhaseBio, PLx Pharma, Regado Biosciences; Board of Directors: Boston VA Research Institute, Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care, TobeSoft; Chair: American Heart Association Quality Oversight Committee; Data Monitoring Committees: Baim Institute for Clinical Research (formerly Harvard Clinical Research Institute, for the PORTICO trial, funded by St Jude Medical, now Abbott), Cleveland Clinic (including for the ExCEED trial, funded by Edwards), Duke Clinical Research Institute, Mayo Clinic, Mount Sinai School of Medicine (for the ENVISAGE trial, funded by Daiichi Sankyo), Population Health Research Institute; Honoraria: American College of Cardiology (Senior Associate Editor, Clinical Trials and News, ACC.org; Vice-Chair, ACC Accreditation Committee), Baim Institute for Clinical Research (formerly Harvard Clinical Research Institute; RE-DUAL PCI clinical trial steering committee funded by Boehringer Ingelheim; AEGIS-II executive committee funded by CSL Behring), Belvoir Publications (Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter), Duke Clinical Research Institute (clinical trial steering committees, including for the PRONOUNCE trial, funded by Ferring Pharmaceuticals), HMP Global (Editor in Chief, Journal of Invasive Cardiology), Journal of the American College of Cardiology (Guest Editor; Associate Editor), Medtelligence/ReachMD (CME steering committees), Population Health Research Institute (for the COMPASS operations committee, publications committee, steering committee, and USA national co-leader, funded by Bayer), Slack Publications (Chief Medical Editor, Cardiology Today’s Intervention), Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care (Secretary/Treasurer), WebMD (CME steering committees); other: Clinical Cardiology (Deputy Editor), NCDR-ACTION Registry Steering Committee (Chair), VA CART Research and Publications Committee (Chair); research funding: Abbott, Afimmune, Amarin, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cardax, Chiesi, CSL Behring, Eisai, Ethicon, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Forest Laboratories, Fractyl, Idorsia, Ironwood, Ischemix, Lexicon, Lilly, Medtronic, Pfizer, PhaseBio, PLx Pharma, Regeneron, Roche, Sanofi Aventis, Synaptic, The Medicines Company; royalties: Elsevier (Editor, Cardiovascular Intervention: A Companion to Braunwald’s Heart Disease); Site Co-Investigator: Biotronik, Boston Scientific, CSI, St Jude Medical (now Abbott), Svelte; Trustee: American College of Cardiology; unfunded research: FlowCo, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Takeda. Dr Ron Blankstein receives research support from Amgen Inc. and Astellas Inc. The remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Thanassoulis G Screening for high lipoprotein(a). Circulation 2019; 139: 1493–1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nordestgaard BG, Chapman MJ, Ray K, et al. Lipoprotein(a) as a cardiovascular risk factor: current status. Eur Heart J 2010; 31: 2844–2853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clarke R, Peden JF, Hopewell JC, et al. Genetic variants associated with Lp(a) lipoprotein level and coronary disease. N Engl J Med 2009; 361: 2518–2528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019; 73: e285–e350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh A, Collins BL, Gupta A, et al. Cardiovascular risk and statin eligibility of young adults after an MI: Partners YOUNG-MI Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018; 71: 292–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao J, Steffen BT, Guan W, et al. Evaluation of lipoprotein(a) electrophoretic and immunoassay methods in discriminating risk of calcific aortic valve disease and incident coronary heart disease: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Clin Chem 2017; 63: 1705–1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baudhuin LM, Hartman SJ, O’Brien JF, et al. Electrophoretic measurement of lipoprotein(a) cholesterol in plasma with and without ultracentrifugation: comparison with an immunoturbidimetric lipoprotein(a) method. Clin Biochem 2004; 37: 481–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goff DC Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 63: 2935–2959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, et al. 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J 2020; 41: 111–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernandez-Labandera C, Calvo-Bonacho E, Valdivielso P, et al. Prediction of fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events in young and middle-aged healthy workers: the IberScore model. Eur J Prev Cardiol. Epub ahead of print 18 December 2019. DOI: 10.1177/2047487319894880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meirhaeghe A, Montaye M, Biasch K, et al. Coronary heart disease incidence still decreased between 2006 and 2014 in France, except in young age groups: results from the French MONICA registries. Eur J Prev Cardiol. Epub ahead of print 26 February 2020. DOI: 10.1177/2047487319899193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh A, Gupta A, Collins BL, et al. Familial hypercholesterolemia among young adults with myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019; 73: 2439–2450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang J, Biery DW, Singh A, et al. Risk factors and outcomes of very young adults who experience myocardial infarction: the Partners YOUNG-MI Registry. Am J Med. Epub ahead of print 13 November 2019. DOI: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsimikas S, Karwatowska-Prokopczuk E, Gouni-Berthold I, et al. Lipoprotein(a) reduction in persons with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 244–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]