Abstract

Background

Disagreement between patient and caregiver about treatment benefits, care decisions, and patient’s health is associated with increased patient depression as well as increased caregiver anxiety, distress, depression, and burden. Understanding factors associated with disagreement may inform interventions to improve the aforementioned outcomes.

Methods

This analysis utilized baseline data from a cluster-randomized geriatric assessment trial that recruited patients aged ≥70 with incurable cancer from community oncology practices (URCC 13070; PI: Mohile). Patients and caregivers were asked to estimate the patient’s prognosis. Response options were 0–6 months, 7–12 months, 1–2 years, 2–5 years, and >5 years. The dependent variable was categorized into exact agreement (reference), patient reported a longer estimate, or caregiver reported a longer estimate. We used generalized estimating equations with multinomial distribution to examine factors associated with patient-caregiver prognostic estimates. We selected independent variables using purposeful selection method.

Results

Among 354 dyads (89% patients screened were enrolled), 26% and 22% of patients and caregivers, respectively, reported a longer estimate. Compared to dyads in agreement, patients were more likely to report a longer estimate when patients screened positive for polypharmacy (β=0.81, P=0.001) and caregivers reported greater distress (β=0.12, P=0.03). Compared to dyads in agreement, caregivers were more likely to report a longer estimate when patients screened positive for polypharmacy (β=0.82, P=0.005) and had lower perceived self-efficacy in interacting with physicians (β=−0.10, P=0.008).

Conclusion

Several patient and caregiver factors were associated with patient-caregiver disagreement about prognostic estimates. Future studies should examine the effects of prognostic disagreement on patient/caregiver outcomes.

Keywords: Prognostic estimates, disagreement, older patients, caregivers, geriatric oncology

Precis

We found that 48% of older patients and caregivers disagreed with each other about the patient’s prognosis; specifically, 26% and 22% of patients and caregivers, respectively, reported a longer estimate of the patient’s prognosis. Caregiver distress, patient communication self-efficacy, polypharmacy, and oncologist gender are associated with patient-caregiver agreement about prognostic estimates.

Introduction

Prognostic understanding in the setting of advanced cancer is important in treatment decision-making [1, 2]. Several studies have demonstrated that prognostic understanding affects healthcare utilization and advanced care planning [3–7]. Therefore, there is a need to improve prognostic understanding so that patients receive care that is concordant with their goals. Caregivers (generally family members or friends) play an integral role in the care of older adults [8], and many participate in prognostic discussions and assist patients with treatment decision-making [9, 10]. Therefore, there is a need to understand prognostic understanding among caregivers.

Effective communication between older patients and caregivers is associated with patient and caregiver satisfaction with care, treatment adherence, and improved health outcomes [11, 12]. In addition, clear communication between patients and caregivers can ensure that the needs of both are met [13]. Studies have shown that disagreements between patients and caregivers in the reporting of symptoms, description of treatment side effects and benefits, and estimates of prognosis are common [7, 14–16]. Disagreement between patient and caregiver about treatment benefits, care decisions, and patient’s health is associated with negative outcomes such as increased patient depression [14] as well increased caregiver anxiety, distress, depression, and burden (i.e., the latter refers to stress experienced by caregivers from providing care for patients) [16–19].

In a study of patients of all ages with advanced cancer and their caregivers, Trevino and colleagues reported that 50% of dyads disagreed on the chance of the patient living more than 2 years [7]. In a separate study of patients with any cancer diagnosis, Shin and colleagues reported that 24% of dyads disagreed on the chance of cure [20]. None of these studies, however, focused specifically on older patients, many of which receive significant help from a caregiver [21–23]. In addition, older patients may have lower prognostic understanding than their younger counterparts [24–26], as well as aging-related conditions (such as functional and cognitive impairment) which may affect how they communicate with their healthcare team and caregivers [27, 28] Therefore, it is important to understand how older patients and their caregivers come to terms with prognostic information. Unrealistic expectations or disagreements about prognosis estimates between older patients and their caregivers may hinder prognostic understanding, complicate communication with oncologists and other care providers, and lead to treatment decisions which are not concordant with patients’ stated goals of care [7, 29]. Understanding the factors associated with disagreement may also inform interventions to improve communication among older patients, their caregivers, and oncology care providers. For example, if patient communication self-efficacy is found to be associated with prognostic estimates, interventions that target patients or caregivers with low self-efficacy or those that focus on improving communication self-efficacy may be considered.

In this study including older adults with cancer and their caregivers, we examined the percentage of dyads disagreeing about prognostic estimates. If disagreement occurred, we assessed whether patients or their caregivers were more likely to report a longer estimate. We also evaluated whether patient aging-related conditions, caregiver health, and other factors were associated with patients and/or caregiver reporting a longer estimate.

Methods

Study design, participants, and setting

We conducted a secondary cross-sectional analysis of baseline data from a nationwide cluster-randomized controlled trial [University of Rochester Cancer Center (URCC) 13070, NCT02107443; Principal Investigator: Mohile]. The details of the study have been reported elsewhere [21, 30–32]. Briefly, patients aged ≥70 with incurable cancer (per the determination of the treating oncologist at the time of enrollment) who were considering and/or receiving any line of cancer treatment, had ≥1 impaired domain on geriatric assessment (other than polypharmacy; defined as ≥5 regularly scheduled medications or any high risk medication on Beers Criteria [33] or creatinine clearance<60), and who were able to provide informed consent were recruited. If the oncology physician determines the patient to not have decision-making capacity, a patient-designated health care proxy signed consent (regardless of decision-making capacity, those scoring ≥11 points on the BLESSED Orientation-Memory-Concentration cognitive screening tool were required to have a health care proxy signed consent). Patients were given the option to enroll one caregiver to the study. Caregiver was defined as “a family member, partner, friend, or caregiver (age 21 or older) with whom the patient discusses or who can be helpful in health-related matters.” Patients and caregivers were enrolled from 31 community oncology practices within the University of Rochester National Cancer Institute Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP) between October 2014 and April 2017. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Rochester and all the individual NCORP affiliate sites prior to enrollment of participants. This unplanned secondary analyses focus on data collected before randomization, and before patients were exposed to the interventions included in the parent trial.

Measures: Dependent variable - Patient-caregiver prognostic estimates

Patients were asked: “Considering your health, and your underlying medical conditions, what would you estimate your overall life expectancy to be?” Caregivers completed a similar assessment of their estimates of the patient’s prognosis. Response options were 0–6 months, 7–12 months, 1–2 years, 2–5 years, and >5 years. These options were converted into a 5-point ordinal scale that ranges from 0–6 months (1 point) to >5 years (5 points). This question was adapted from a previous study of seriously ill older patients (included those with cancer) and their caregivers [34].. The original study had <1 month, 1–6 months, 7–12 months, >12 months, and “uncertain” as options. Instead, we combined <1 month and 1–6 months, and created new options for 1–2 years, 2–5 years, and >5 years because while we included patients with incurable cancer, they may have indolent cancer (e.g., follicular lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia). Dyads where the patients or caregivers did not provide a response were excluded, because we were interested in examining the correlates of disagreement in prognostic estimates where both the patient and caregiver provided a quantitative response.

We categorized patient-caregiver prognostic estimates into three categories based on investigator consensus: Exact agreement (patient and caregiver selecting the same response; reference), patient prognostic estimate > caregiver prognostic estimate (patient reporting a longer estimate), and caregiver prognostic estimate > patient prognostic estimate (caregiver reporting a longer estimate). For example, if a patient selected 7–12 months (2 points) and a caregiver selected 7–12 months (2 points), they were considered to be in complete agreement. If a patient selected 7–12 months (2 points) and a caregiver selected 1–2 years (3 points), the caregiver reported a longer estimate.

Measures: Independent variables

We selected variables based on prior studies [7, 29, 31, 32] and investigator consensus.

Patient variables: Demographics, cancer type, aging-related conditions, communication

Patient demographics included age, gender, education, marital status, and annual household income. Cancer type was also included. Aging-related conditions were evaluated using standardized and validated geriatric assessment tools in eight domains: functional status, physical performance, comorbidity, cognition, instrumental social support, polypharmacy (independent of comorbidity), psychological health, and nutrition (Supplemental Table 1) [30, 35]. Communication variables included patient self-efficacy for communication and whether the patient recalled having a prognostic discussion. Self-efficacy was assessed using the 5-item Perceived Efficacy in Patient-Physician Interactions (PEPPI) (range from 0–45, higher score indicates better self-efficacy) [36]. For recalled prognostic discussion, patients were asked about the extent they had discussed their prognosis with the oncologist. Options were “completely”, “mostly”, “a little”, and “not at all” [37]. The options were collapsed into two categories (“completely” and “mostly” vs. “a little” or “not at all”).

Caregiver variables: Demographics, caregiver health, communication

Caregiver demographics included age, gender, education, marital status, and annual household income. Caregiver health was assessed using the Older Americans Resources and Services (OARS) Comorbidity questionnaire [38], 12-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) [39] for quality of life, distress thermometer [40], Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) screening tool for depression [41], and Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) (Supplemental Table 1) [42]. Communication variables included caregiver self-efficacy for communication and whether the caregiver recalled having a prognostic discussion. Self-efficacy was assessed using the 5-item Perceived Efficacy in Caregiver-Physician Interaction (PECPI) scales (range from 0–45, higher score indicates better self-efficacy) [36]. For recalled prognostic discussion, caregivers were asked about the extent they had discussed the patient’s prognosis with the oncologist. Options were “completely”, “mostly”, “a little”, or “not at all” [37]. The options were collapsed into two categories (“completely” and “mostly” vs. “a little” or “not at all”).

Other variables: Patient-caregiver relationship and oncologist variables

We included patient-caregiver relationship (spouse or cohabiting partner, son or daughter, and others). Oncologist variables included age, gender, race, and years since practice.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive analyses were used to summarize our data. We used bivariate analyses to assess demographic (patient, caregiver, oncologist), clinical, aging-related, and communication factors associated with patient-caregiver prognostic estimates. Patient-caregiver relationship was also assessed. All variables with a P-value of <0.25 on bivariate analyses were entered into our multivariate models [43]. We then used generalized estimating equations with multinomial distribution and glogit link function to examine factors associated with patient-caregiver prognostic estimates, adjusting for clustering at the practice oncology site. Using the purposeful selection method, the final model included variables with a P<0.10 [43]. To minimize collinearity, we created two multivariate models (patient and caregiver model). For the patient model, we pre-specified the inclusion of patient age, gender, race, and education, regardless of significance level based on prior literature showing their associations with prognostic estimates [32, 37, 44, 45]. For the caregiver model, we pre-specified the inclusion of caregiver age, gender, race, and education, regardless of significance level based on similar rationale as the patient model. We considered a two-sided P<0.05 to be statistically significant based on the exploratory nature of this study. We used the SAS v.9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) to perform all analyses.

Results

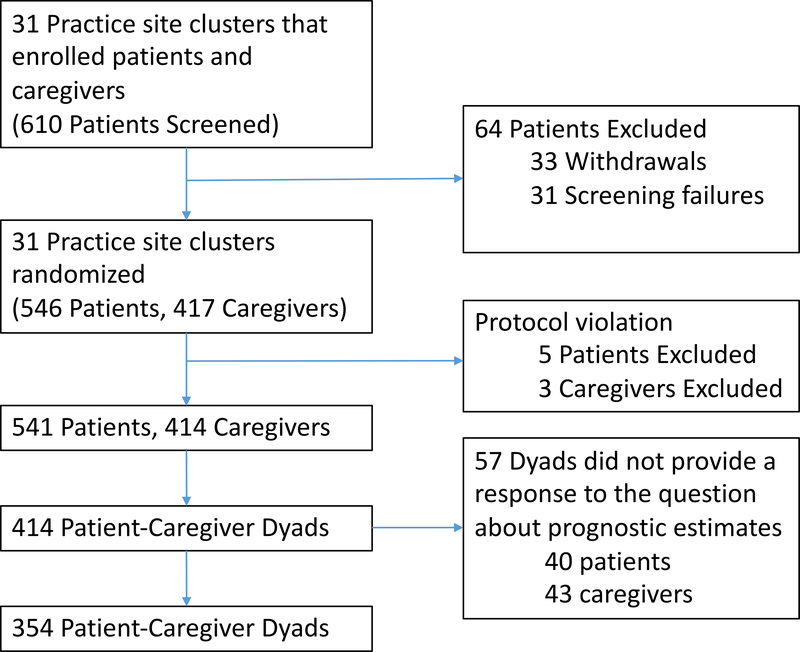

The primary study included 414 patient-caregiver dyads (out of 610 patients screened; Figure 1) [21]; we excluded 3 dyads who were missing all demographics for caregivers. Forty patients and 43 caregivers (57 dyads) did not provide a response to the question about prognostic estimates. Therefore, our final sample included 354 patient-caregiver dyads. Of these, 10 patients scored ≥11 points on the BLESSED Orientation-Memory-Concentration cognitive screening tool and were required to have a health care proxy signed consent.

Figure 1:

Flow diagram depicting the number of patients screened, enrolled, and included in our final sample

Mean age of the patients and caregivers was 76.6 (SD 5.4, range 70–96) and 66.7 (SD 12.3, range 26–92) years, respectively. Almost 60% of the patients were males, and 76% of the caregivers were females. Cancer type was heterogeneous, with a quarter having lung cancer (25%) and 22% having a gastrointestinal cancer. Approximately 68% of the caregivers were spouses or cohabitating partners, 22% were children, and 10% reported other relationships. Other patient and caregiver demographics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics of patients and caregivers

| Variables | Patients (N=354) | Caregivers (N=354) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD, range)a | 76.6 (5.4, 70–96) | 66.7 (12.3, 26–92) | |

| Gender, %a | Male | 211 (59.6) | 85 (24.1) |

| Female | 143 (40.4) | 268 (76.0) | |

| Marital Status, %a | Married | 260 (73.5) | 291 (82.4) |

| Other | 94 (26.6) | 62 (17.6) | |

| Race, %a | Non-Hispanic White | 322 (91.0) | 320 (90.7) |

| Non-White | 32 (9.0) | 33 (9.4) | |

| Education, %a | Some college or above | 186 (52.5) | 228 (64.6) |

| High school graduate | 117 (33.1) | 101 (28.6) | |

| <High school | 51 (14.4) | 24 (6.8) | |

| Annual household income, %b,c | >$50,000 | 124 (35.1) | 158 (44.9) |

| ≤$50,000 | 166 (47.0) | 133 (37.8) | |

| Decline to answer | 63 (17.9) | 61 (17.3) | |

| Cancer type, % | Breast | 37 (10.5) | - |

| Gastrointestinal | 79 (22.3) | - | |

| Genitourinary | 52 (14.7) | - | |

| Lung | 90 (25.4) | - | |

| Otherf | 96 (27.1) | - | |

| Comorbidity, % | Impaired | 223 (63.0) | 141 (39.9) |

| Physical performance, % | Impaired | 332 (93.8) | - |

| Functional status, % | Impaired | 213 (60.2) | - |

| Cognition, % | Impaired | 118 (33.3) | - |

| Nutrition, % | Impaired | 217 (61.3) | - |

| Social support, % | Impaired | 73 (20.6) | - |

| Polypharmacy, % | Impaired | 300 (84.8) | - |

| Psychological health, % | Impaired | 92 (26.0) | - |

| Patient-caregiver relationship | Spouse or cohabiting partner | 240 (68.0) | - |

| Son or daughter | 79 (22.4) | - | |

| Others | 34 (9.6) | - | |

| Anxiety (GAD-7), mean (SD)c | - | 3.1 (4.4) | |

| Depression (PHQ-2), mean (SD)a | - | 0.6 (1.1) | |

| Self-rated health (SF-12), mean (SD)c | - | 98.2 (14.1) | |

| Distress, mean (SD)d | - | 3.2 (2.9) | |

| Recalled prognosis, %e | Completely/Mostly | 256 (72.7) | 229 (64.7) |

| A little/Not at all | 96 (27.2) | 125 (35.3) | |

| PEPPI, mean (SD) | 21.5 (3.3) | - | |

| PECPI, mean (SD) | - | 21.7 (3.3) |

1 caregiver had missing data

1 patient had missing data

2 caregivers had missing data

5 caregiver had missing data

2 patients had missing data

27 had lymphoma, 25 had gynecologic cancer, 5 had head & neck cancer, 5 had leukemia (type not specified), 3 had melanoma, 2 had mesothelioma, 2 had brain cancer, and the remaining had other cancer

Abbreviations: GAD-7, General Anxiety Disorder 7; PECPI, Perceived Efficacy in Caregiver-Physician Interactions; PEPPI, Perceived Efficacy in Patient-Physician Interactions; PHQ-2, Patient Health Questionaire-2; SD, standard deviation; SF12, 12-Item Short Form Health Survey

Patient-caregiver prognostic estimates

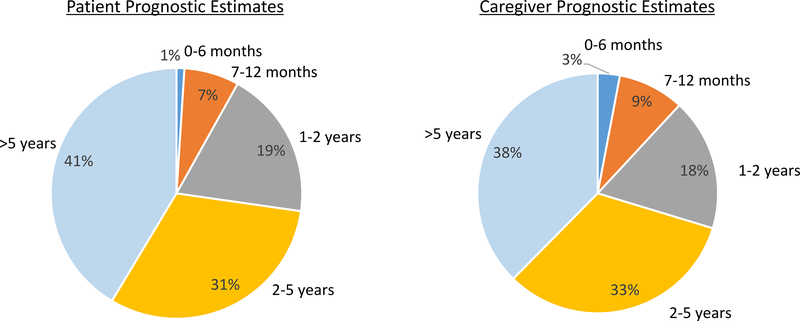

The majority of patients and caregivers responded that the patients would live ≥2 years (72% and 71%, respectively). Eight percent and 12% of patients and caregivers, respectively, responded that the patients would live ≤12 months. Figure 2 shows the distribution of prognostic estimates among both patients and caregivers.

Figure 2:

Patient and caregivers’ prognostic estimates for older adults with advanced cancer

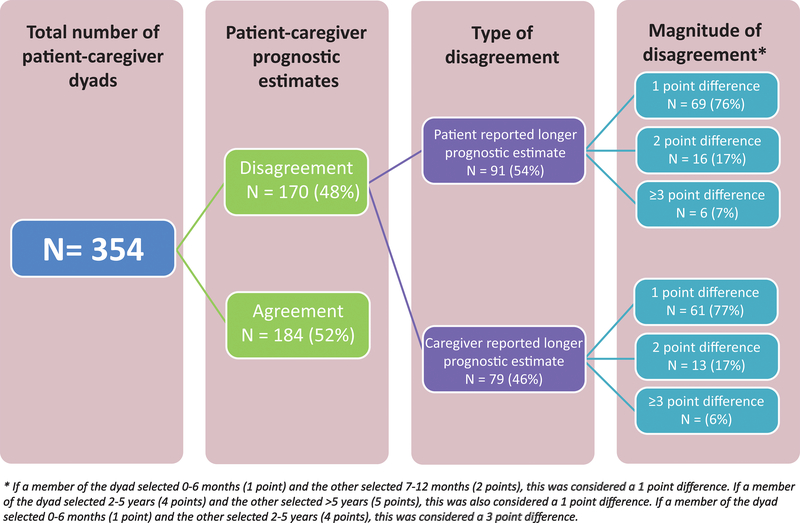

Fifty-two percent of the patient-caregiver dyads agreed in their estimates of the patient’s life expectancy (Figure 3). Disagreement occurred in 48% (170/354) of the dyads; patients reported a longer estimate in 26% (91/354) while caregivers reported a longer estimate in 22% (79/354) of dyads. Approximately 76% of the disagreement (130/170) consisted of a 1-point difference. Figure 3 shows the extent of patient and caregiver disagreement.

Figure 3.

Disagreement in prognostic estimates between patients and oncologists

Supplemental Table 2 shows the patient, caregiver, and other variables assessed on bivariate analyses. Cognition, polypharmacy, psychological health, PEPPI, caregiver age, caregiver anxiety, caregiver distress, physician age, and physician gender met the pre-specified cut-off on bivariate analyses (P<0.25) to be included in the multivariate models. Caregiver anxiety was not included due to significant correlation with caregiver distress (r=0.52, P<0.0001). In addition, when we created separate multivariate model for caregiver anxiety, it was not significant.

For the patient model, on adjusted analyses, compared to dyads in agreement, patients were more likely to report a longer estimate when patients screened positive for polypharmacy [β=0.81, 95% CI (Confidence Interval)=0.33 to 1.30, P=0.001] and when caregivers reported greater distress (β=0.12, 95% CI=0.01 to 0.23, P=0.03) (Table 2). Compared to dyads in agreement, caregivers were more likely to report a longer estimate when patients screened positive for polypharmacy (β=0.82, 95% CI=0.25 to 1.38, P=0.005) and had lower perceived self-efficacy in patient-physician interactions (β=−0.10, 95% CI=−0.18 to −0.03, P=0.008). Caregivers were less likely to report a longer estimate when the patient’s oncologist was female (β=−0.73, 95% CI=−1.38 to −0.07, P=0.03). For the caregiver model, results were similar (except that impaired psychological health were associated with caregivers reporting a longer estimate; Table 3).

Table 2:

Adjusted analyses showing the associations of factors with patient-caregiver prognostic estimates (Patient model)

| Variables | Patients reporting a longer estimate | Agreement | Caregivers reporting a longer estimate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient variables | β | 95% CI | P-value | β | 95% CI | P-value | ||

| Age | 0.03 | (−0.01, 0.06) | 0.11 | Ref | 0.01 | (−0.04, 0.07) | 0.66 | |

| Gender | Female vs Male | −0.30 | (−0.96, 0.35) | 0.36 | Ref | 0.19 | (−0.34, 0.73) | 0.48 |

| Race | Non-White vs. White | −0.13 | (−0.94, 0.69) | 0.74 | Ref | −0.38 | (−1.39, 0.64) | 0.47 |

| Education | <High school vs. Some college or above | −0.40 | (−1.10, 0.29) | 0.26 | Ref | −0.43 | (−1.34, 0.48) | 0.35 |

| High school grade vs. Some college or above | −0.37 | (−0.87, 0.13) | 0.14 | Ref | −0.41 | (−0.88, 0.06) | 0.09 | |

| Polypharmacy | Screened positive vs. Negative | 0.81 | (0.33, 1.30) | 0.001 | Ref | 0.82 | (0.25, 1.38) | 0.005 |

| Psychological Health | Impaired | 0.09 | (−0.37, 0.55) | 0.71 | Ref | 0.49 | (−0.06, 1.03) | 0.08 |

| PEPPI | −0.01 | (−0.10, 0.08) | 0.87 | Ref | −0.10 | (−0.18, −0.03) | 0.008 | |

| Caregiver variables | ||||||||

| Distress | 0.12 | (0.01,0.23) | 0.03 | Ref | 0.04 | (−0.02, 0.10) | 0.24 | |

| Oncologist variables | ||||||||

| Physician gender | Female vs Male | −0.35 | (−0.81, 0.12) | 0.14 | Ref | −0.73 | (−1.38, −0.07) | 0.03 |

Abbreviations: CI, Confidence Interval; PEPPI, Perceived Efficacy in Patient-Physician Interactions

Table 3:

Adjusted analyses showing the associations of factors with patient-caregiver prognostic estimates (Caregiver model)

| Variables | Patients reporting a longer estimate | Agreement | Caregivers reporting a longer estimate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient variables | β | 95% CI | P-value | β | 95% CI | P-value | ||

| Cognition | Impaired | 0.24 | (−0.42, 0.89) | 0.48 | Ref | −0.74 | (−1.53, 0.05) | 0.07 |

| Polypharmacy | Screened positive vs. negative | 0.78 | (0.28, 1.27) | 0.002 | Ref | 0.87 | (0.27, 1.46) | 0.004 |

| Psychological Health | Impaired | −0.05 | (−0.56, 0.45) | 0.83 | Ref | 0.67 | (0.12, 1.22) | 0.02 |

| PEPPI | −0.008 | (−0.10, 0.08) | 0.87 | Ref | −0.09 | (−0.17, −0.02) | 0.01 | |

| Caregiver variables | ||||||||

| Age | −0.01 | (−0.03, 0.01) | 0.38 | Ref | 0.02 | (−0.01, 0.04) | 0.14 | |

| Gender | Female vs Male | −0.36 | (−0.84, 0.13) | 0.15 | Ref | −0.80 | (−1.52, −0.08) | 0.03 |

| Race | Non-White vs. White | −0.17 | (−1.10, 0.75) | 0.71 | Ref | −0.09 | (−1.27, 1.10) | 0.88 |

| Education | <High school vs. Some college or above | −0.08 | (−1.03, 0.87) | 0.87 | Ref | −0.96 | (−2.22, 0.29) | 0.13 |

| <High school vs. high school graduate | 0.005 | (−0.54, 0.55) | 0.99 | Ref | 0.27 | (−0.35, 0.87) | 0.39 | |

| Distress | 0.11 | (0.02, 0.19) | 0.01 | Ref | 0.03 | (−0.03, 0.10) | 0.31 | |

| Oncologist variables | ||||||||

| Physician gender | Female vs Male | −0.36 | (−0.84, 0.13) | 0.15 | Ref | −0.80 | (−1.52, −0.08) | 0.03 |

Abbreviations: CI, Confidence Interval; PEPPI, Perceived Efficacy in Patient-Physician Interactions

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that almost half of dyads, consisting of older patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers, disagreed on estimates of the patient’s prognosis, though most disagreement consisted of a 1-point difference. Factor associated with patients reporting a longer estimate included patient polypharmacy and greater caregiver distress. Factors associated with caregivers reporting a longer estimate included patient polypharmacy and patient-perceived lower efficacy in interacting with their oncologists.

Few studies have examined patient-caregiver agreement about prognosis, and none focused on older adults. No standard definition of disagreement in prognostic estimates exists and studies have used varying methods to evaluate and define agreement [7, 29]. Two studies among patients with advanced cancer (where estimated patient prognosis was ≤6 and ≤12 months, respectively) categorized patient-caregiver prognostic estimates into those which agreed on long prognosis (>12 months), those which agreed on a short prognosis (≤12 months), and those which disagreed with each other [7, 29]. In these studies, disagreement occurred in 28% to 50% of the dyads. Completion of Do Not Resuscitate orders and hospice enrollment were higher when patients and caregivers agreed that the patient would have a short prognosis compared to the other two groups [7, 29]. These studies indicate that both disagreement and unrealistic agreement (dyads who agreed on >12 months prognosis) in prognostic estimates are associated with lower utilization of palliative and hospice services at the end of life. Our categorization of prognostic estimates differs and were not based on the aforementioned classification (agreement on >12 months vs. agreement on ≤12 months vs. disagreement), but rather based on agreement and disagreement; the latter was further divided into whether patients or caregivers reporting a longer estimate. Other studies have demonstrated that disagreement between patients and caregivers regarding the patient’s health, treatment, and care was associated with increased caregiver burden and both patient and caregiver depression [14, 16].

This study adds to the literature measuring disagreement between older patients and their caregivers about prognostic estimates; novel data include assessment of factors associated with patient and caregivers reporting a longer estimate, identifying some potentially reversible targets to reduce this disagreement. We found that disagreement (either patients or caregiver reporting s longer estimate, compared to agreement) was more common in dyads where the patient screened positive for polypharmacy (whereas comorbidity was not associated with patient-caregiver prognostic estimates). One possible explanation is that patients who are on many medications see many physicians, undergo more tests, strongly believe in the necessity of their medications and cancer treatments [46], and may perceive them as being able to cure them and make them feel better. These beliefs may also occur in their caregivers, which may explain the reason polypharmacy was the only variable to show an association with both patient and caregiver reporting longer estimate. These beliefs may be influenced by their relationships with the physicians [46]. In addition, being on multiple medications may also bring a sense of control [47]that they are actively helping to prevent negative outcomes which may perpetuate the notion that cancer therapies will have similar efficacy. Finally, polypharmacy may be marker of illness severity, and communication breakdown has been shown to be more likely among patients with higher illness severity [48]. While mitigating polypharmacy may not necessarily lead to an improvement in prognostic agreement between patients and caregivers, finding this geriatric syndrome should lead to a more detailed assessment of prognostic awareness and of the quality of patient-caregiver communication.

In this study, caregiver distress was more common when patients reported a longer estimate (compared to caregivers in dyads who were in agreement). Caregivers may find it challenging to convince their loved ones of a poor prognosis or may even collude with the patient’s optimism, inducing distress. This association has been shown in a prior study [17]. Caregivers may also have the added pressure of planning for end-of-life care in the midst of patient’s optimism. On the other hand, patient distress was not associated with patients or caregivers reporting longer estimate. Patient-oncologist discordance in prognostic understanding was previously shown to be associated with higher psychological distress [49, 50]. This suggests that patients may perceive their disagreement with their oncologists and caregivers differently, and perhaps they are less affected by what caregivers think of their prognosis, though this needs to be further explored. In addition, when patients perceived a lower efficacy in interacting with their oncologists, caregivers were more likely to report a longer estimate. As a consequence of their lower efficacy, these patients might not have understood the prognostic information provided by their oncologists and thereby were not able to communicate the information effectively to their caregivers. Alternatively, patients who had lower efficacy may also have lower feelings of control and more hopelessness [51].

It is interesting that caregivers were less likely to report a longer estimate (vs. agreement) when the patient’s oncologist was female. A prior study showed that patients had more accurate prognostic awareness if their oncologist was female, though this was not statistically significant [52] Two systematic reviews also showed that female physicians adopt a more partnership building style, positive talk, psychosocial counseling, psychosocial question asking, and emotionally focused talk, and they also spend a longer time with their patients [53]. It is possible that female physicians use the same skills to communicate with caregiver, but this needs to be further explored.

Caregivers face significant difficulties in communicating with patients about illness, prognosis, and death [54], and patients also face similar difficulties in communicating with caregivers [55, 56]. In addition, caregivers report not being told by physicians about the patient’s prognosis, which may contribute to patient-caregiver disagreement, although caregiver-recalled prognostic discussion did not meet the pre-specified criterion to be included in our multivariate model (negative association)[57]. It is possible that caregivers were not present at the clinical encounter, were not able to recall the discussion about prognosis, or were in denial [58]. Together with published studies, we demonstrate a need for interventions to improve prognostic understanding between patients, caregivers, and healthcare professionals. Our study identified characteristics of dyads who are more likely to disagree with each other on prognosis, and this information may help with tailoring of communication and supportive care interventions to dyads [59–61]. One such intervention includes palliative care which has been shown to improve caregiver communication as well as prognostic understanding by developing coping skills [50, 62–64]. None of these resources, however, focuses on older adults with cancer and their caregivers, who have different needs (e.g., higher prevalence of aging-related conditions) than their younger counterparts [65, 66]. Interventions to improve communication between older adults with cancer and their caregivers, and to enhance their prognostic understanding are clearly needed. Specifically, strategies to improve patient self-efficacy and caregiver distress as part of their cancer care may influence patient and caregiver understanding of prognosis.

Our study has several strengths. This is the first study, to our knowledge, that evaluated prognostic estimates of older patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers. Second, because we recruited a large number of participants from more than 30 community oncology practices, these results are widely generalizable to older adults with cancer in the US. Our study also has several limitations. First, this was a cross-sectional analysis and therefore causality cannot be determined. In other words, the associations may go either direction. Second, there is no standard definition of patient and caregiver agreement or disagreement in the context of prognostic understanding, our definition is based on prior literature of patients and oncologists, and the specific measures that were utilized are not validated in this population [31, 67]. Third, we did not compare prognostic estimates with actual survival data, and our categorization of prognostic estimates are relative rather than absolute. Fourth, caregiver consent rate was also not systematically collected and therefore was not available. We also excluded approximately 15% of patients or caregivers who did not provide a response to the prognostic estimates question, because we were unable to determine whether the patient or caregiver reported a longer estimate. Future studies should consider studying this particular group of patients and caregivers who are likely to be more uncertain of or unwilling to “commit” to a prognosis. Fifth, we only included patients who had incurable disease as determined by the oncologist at enrollment and were considering or receiving treatment. Therefore, our findings are not generalizable to those who were not considered for treatment due to underlying frailty or other reasons. We also did not collect other variables that may be associated with prognostic estimates including time since cancer diagnosis, time since diagnosis with incurable disease, whether or not the patients were informed of the incurable nature of their disease, and number and type of appointments attended. Finally, our results are mainly applicable to older non-Hispanic White patients living in the US and those who are relatively well-educated. Patient-caregiver agreement is influenced by social, cultural, or health system factors, which can vary according to racial/ethnic group and from country to country [7, 20]. Therefore, studies focusing on other populations are needed.

In conclusion, caregiver distress, patient communication self-efficacy, patient polypharmacy, and gender of oncologist are associated with older patient and caregiver disagreement about prognostic estimates. Future longitudinal studies are needed to examine the effects of prognostic disagreement on patient and caregiver outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

The work was supported by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Program contract (4634 to SGM), the National Cancer Institute at the National Institute of Health (UG1 CA189961); R01CA168387 to PRD; K99CA237744 to KPL), the National Institute of Aging at the National Institute of Health (K24 AG056589 to SGM; R21 AG059206 to SGM; K76 AG064394 to AM), and the Wilmot Research Fellowship Award (grant number is not applicable; to KPL). This work was made possible by the generous donors to the Wilmot Cancer Institute (WCI) geriatric oncology philanthropy fund. All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors, do not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies, and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors, or Methodology Committee. We wish to acknowledge Dr. Susan Rosenthal, MD for her editorial assistance, and Ms. Shuhan Yang for her assistance with figures creation.

Funding Statement:

Authors’ Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Mohile served as a consultant to Seattle Genetics and received research funding from Carevive for other projects. Dr. Loh serves as a consultant to Pfizer and Seattle Genetics.

Footnotes

Prior presentation: The study was selected for a Lightning Science Oral Presentation as well as a Presidential Poster Presentation at the 2019 American Geriatrics Society Annual Meeting

References

- 1.Tang ST, Chen CH, Wen FH et al. Accurate Prognostic Awareness Facilitates, Whereas Better Quality of Life and More Anxiety Symptoms Hinder End-of-Life Care Discussions: A Longitudinal Survey Study in Terminally Ill Cancer Patients’ Last Six Months of Life. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018; 55: 1068–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Epstein AS, Prigerson HG, O’Reilly EM, Maciejewski PK. Discussions of Life Expectancy and Changes in Illness Understanding in Patients With Advanced Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: 2398–2403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mack JW, Walling A, Dy S et al. Patient beliefs that chemotherapy may be curative and care received at the end of life among patients with metastatic lung and colorectal cancer. Cancer 2015; 121: 1891–1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mack JW, Weeks JC, Wright AA et al. End-of-life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 1203–1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang ST, Liu TW, Chow JM et al. Associations between accurate prognostic understanding and end-of-life care preferences and its correlates among Taiwanese terminally ill cancer patients surveyed in 2011–2012. Psychooncology 2014; 23: 780–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Enzinger AC, Zhang B, Schrag D, Prigerson HG. Outcomes of Prognostic Disclosure: Associations With Prognostic Understanding, Distress, and Relationship With Physician Among Patients With Advanced Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 3809–3816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trevino KM, Prigerson HG, Shen MJ et al. Association between advanced cancer patient-caregiver agreement regarding prognosis and hospice enrollment. Cancer 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Spouses, adult children, and children-in-law as caregivers of older adults: a meta-analytic comparison. Psychol Aging 2011; 26: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glajchen M The emerging role and needs of family caregivers in cancer care. J Support Oncol 2004; 2: 145–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dionne-Odom JN, Ejem D, Wells R et al. How family caregivers of persons with advanced cancer assist with upstream healthcare decision-making: A qualitative study. PLoS One 2019; 14: e0212967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wittenberg E, Borneman T, Koczywas M et al. Cancer Communication and Family Caregiver Quality of Life. Behav Sci (Basel) 2017; 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waldron EA, Janke EA, Bechtel CF et al. A systematic review of psychosocial interventions to improve cancer caregiver quality of life. Psychooncology 2013; 22: 1200–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wittenberg E, Buller H, Ferrell B et al. Understanding Family Caregiver Communication to Provide Family-Centered Cancer Care. Semin Oncol Nurs 2017; 33: 507–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang AY, Zyzanski SJ, Siminoff LA. Differential patient-caregiver opinions of treatment and care for advanced lung cancer patients. Soc Sci Med 2010; 70: 1155–1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McPherson CJ, Wilson KG, Lobchuk MM, Brajtman S. Family caregivers’ assessment of symptoms in patients with advanced cancer: concordance with patients and factors affecting accuracy. J Pain Symptom Manage 2008; 35: 70–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsu T, Loscalzo M, Ramani R et al. Are Disagreements in Caregiver and Patient Assessment of Patient Health Associated with Increased Caregiver Burden in Caregivers of Older Adults with Cancer? Oncologist 2017; 22: 1383–1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodenbach RA, Norton SA, Wittink MN et al. When chemotherapy fails: Emotionally charged experiences faced by family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer. Patient Educ Couns 2019; 102: 909–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sonnenblick M, Friedlander Y, Steinberg A. Dissociation between the wishes of terminally ill parents and decisions by their offspring. J Am Geriatr Soc 1993; 41: 599–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higginson IJ, Gao W. Caregiver assessment of patients with advanced cancer: concordance with patients, effect of burden and positivity. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2008; 6: 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shin DW, Cho J, Kim SY et al. Patients’ and family caregivers’ understanding of the cancer stage, treatment goal, and chance of cure: A study with patient-caregiver-physician triad. Psychooncology 2018; 27: 106–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kehoe LA, Xu H, Duberstein P et al. Quality of Life of Caregivers of Older Patients with Advanced Cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019; 67: 969–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duberstein PR, Maciejewski PK, Epstein RM et al. Effects of the Values and Options in Cancer Care Communication Intervention on Personal Caregiver Experiences of Cancer Care and Bereavement Outcomes. J Palliat Med 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giovannetti ER, Wolff JL. Cross-survey differences in national estimates of numbers of caregivers of disabled older adults. Milbank Q 2010; 88: 310–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Numico G, Anfossi M, Bertelli G et al. The process of truth disclosure: an assessment of the results of information during the diagnostic phase in patients with cancer. Ann Oncol 2009; 20: 941–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brokalaki EI, Sotiropoulos GC, Tsaras K, Brokalaki H. Awareness of diagnosis, and information-seeking behavior of hospitalized cancer patients in Greece. Support Care Cancer 2005; 13: 938–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caruso A, Di Francesco B, Pugliese P et al. Information and awareness of diagnosis and progression of cancer in adult and elderly cancer patients. Tumori 2000; 86: 199–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nussbaum JF, Baringer O, Kundrat A. Health, communication, and aging: cancer and older adults. Health Commun 2003; 15: 185–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yorkston KM, Bourgeois MS, Baylor CR. Communication and aging. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2010; 21: 309–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shen MJ, Trevino KM, Prigerson HG. The interactive effect of advanced cancer patient and caregiver prognostic understanding on patients’ completion of Do Not Resuscitate orders. Psychooncology 2018; 27: 1765–1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mohile SG, Epstein RM, Hurria A et al. Communication With Older Patients With Cancer Using Geriatric Assessment: A Cluster-Randomized Clinical Trial From the National Cancer Institute Community Oncology Research Program. JAMA Oncol 2019; 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loh KP, Mohile SG, Lund JL et al. Beliefs About Advanced Cancer Curability in Older Patients, Their Caregivers, and Oncologists. Oncologist 2019; 24: e292–e302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loh KP, Mohile SG, Epstein RM et al. Willingness to bear adversity and beliefs about the curability of advanced cancer in older adults. Cancer 2019; 125: 2506–2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012; 60: 616–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fried TR, Bradley EH, O’Leary J. Changes in prognostic awareness among seriously ill older persons and their caregivers. J Palliat Med 2006; 9: 61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mohile SG, Dale W, Somerfield MR et al. Practical Assessment and Management of Vulnerabilities in Older Patients Receiving Chemotherapy: ASCO Guideline for Geriatric Oncology. J Clin Oncol 2018; Jco2018788687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maly RC, Frank JC, Marshall GN et al. Perceived efficacy in patient-physician interactions (PEPPI): validation of an instrument in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 1998; 46: 889–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gramling R, Fiscella K, Xing G et al. Determinants of Patient-Oncologist Prognostic Discordance in Advanced Cancer. JAMA Oncol 2016; 2: 1421–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fillenbaum GG. Multidimensional functional assessment of older adults.: The Duke Older Americans Resources and Services procedures Hilldale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ware J Jr., Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996; 34: 220–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hurria A, Li D, Hansen K et al. Distress in older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 4346–4351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care 2003; 41: 1284–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166: 1092–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bursac Z, Gauss CH, Williams DK, Hosmer DW. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code Biol Med 2008; 3: 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loh KP, Xu H, Back A et al. Patient-hematologist discordance in perceived chance of cure in hematologic malignancies: A multicenter study. Cancer 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Applebaum AJ, Kolva EA, Kulikowski JR et al. Conceptualizing prognostic awareness in advanced cancer: a systematic review. J Health Psychol 2014; 19: 1103–1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clyne B, Cooper JA, Boland F et al. Beliefs about prescribed medication among older patients with polypharmacy: a mixed methods study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2017; 67: e507–e518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rossi MI, Young A, Maher R et al. Polypharmacy and health beliefs in older outpatients. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2007; 5: 317–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fried TR, Bradley EH, Towle VR. Valuing the outcomes of treatment: do patients and their caregivers agree? Arch Intern Med 2003; 163: 2073–2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.El-Jawahri A, Traeger L, Kuzmuk K et al. Prognostic understanding, quality of life and mood in patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2015; 50: 1119–1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nipp RD, Greer JA, El-Jawahri A et al. Coping and Prognostic Awareness in Patients With Advanced Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35: 2551–2557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rottmann N, Dalton SO, Christensen J et al. Self-efficacy, adjustment style and well-being in breast cancer patients: a longitudinal study. Qual Life Res 2010; 19: 827–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu PH, Landrum MB, Weeks JC et al. Physicians’ propensity to discuss prognosis is associated with patients’ awareness of prognosis for metastatic cancers. J Palliat Med 2014; 17: 673–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roter DL, Hall JA, Aoki Y. Physician gender effects in medical communication: a meta-analytic review. Jama 2002; 288: 756–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bachner YG, Carmel S. Open communication between caregivers and terminally ill cancer patients: the role of caregivers’ characteristics and situational variables. Health Commun 2009; 24: 524–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fried TR, Bradley EH, O’Leary JR, Byers AL. Unmet desire for caregiver-patient communication and increased caregiver burden. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005; 53: 59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Song L, Northouse LL, Zhang L et al. Study of dyadic communication in couples managing prostate cancer: a longitudinal perspective. Psychooncology 2012; 21: 72–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cherlin E, Fried T, Prigerson HG et al. Communication between physicians and family caregivers about care at the end of life: when do discussions occur and what is said? J Palliat Med 2005; 8: 1176–1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.LeSeure P, Chongkham-Ang S. The Experience of Caregivers Living with Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Synthesis. J Pers Med 2015; 5: 406–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Epstein RM, Duberstein PR, Fenton JJ et al. Effect of a Patient-Centered Communication Intervention on Oncologist-Patient Communication, Quality of Life, and Health Care Utilization in Advanced Cancer: The VOICE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol 2017; 3: 92–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zulman DM, Schafenacker A, Barr KL et al. Adapting an in-person patient-caregiver communication intervention to a tailored web-based format. Psychooncology 2012; 21: 336–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Titler MG, Visovatti MA, Shuman C et al. Effectiveness of implementing a dyadic psychoeducational intervention for cancer patients and family caregivers. Support Care Cancer 2017; 25: 3395–3406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.von Heymann-Horan A, Bidstrup PE, Johansen C et al. Dyadic coping in specialized palliative care intervention for patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers: Effects and mediation in a randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology 2019; 28: 264–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Temel JS, Greer JA, Admane S et al. Longitudinal perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a randomized study of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 2319–2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Greer JA, Jacobs JM, El-Jawahri A et al. Role of Patient Coping Strategies in Understanding the Effects of Early Palliative Care on Quality of Life and Mood. J Clin Oncol 2018; 36: 53–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mohile SG, Fan L, Reeve E et al. Association of cancer with geriatric syndromes in older Medicare beneficiaries. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 1458–1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Posma ER, van Weert JC, Jansen J, Bensing JM. Older cancer patients’ information and support needs surrounding treatment: An evaluation through the eyes of patients, relatives and professionals. BMC Nurs 2009; 8: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.El-Jawahri A, Nelson-Lowe M, VanDusen H et al. Patient-Clinician Discordance in Perceptions of Treatment Risks and Benefits in Older Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Oncologist 2019; 24: 247–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.