Abstract

The central nervous system controls feeding behavior and energy expenditure in response to various internal and external stimuli to maintain energy balance. Here we report that the newly identified transcription factor zinc finger and BTB domain containing 16 (Zbtb16) is induced by energy deficit in the paraventricular (PVH) and arcuate (ARC) nuclei of the hypothalamus via glucocorticoid (GC) signaling. In the PVH, Zbtb16 is expressed in the anterior half of the PVH and co-expressed with many neuronal markers such as corticotropin-releasing hormone (Crh), thyrotropin-releasing hormone (Trh), oxytocin (Oxt), arginine vasopressin (Avp), and nitric oxide synthase 1 (Nos1). Knockdown (KD) of Zbtb16 in the PVH results in attenuated cold-induced thermogenesis and improved glucose tolerance without affecting food intake. In the meantime, Zbtb16 is predominantly expressed in agouti-related neuropeptide/neuropeptide Y (Agrp/Npy) neurons in the ARC and its KD in the ARC leads to reduced food intake. We further reveal that chemogenetic stimulation of PVH Zbtb16 neurons increases energy expenditure while that of ARC Zbtb16 neurons increases food intake. Taken together, we conclude that Zbtb16 is an important mediator that coordinates responses to energy deficit downstream of GCs by contributing to glycemic control through the PVH and feeding behavior regulation through the ARC, and additionally reveal its function in controlling energy expenditure during cold-evoked thermogenesis via the PVH. As a result, we hypothesize that Zbtb16 may be involved in promoting weight regain after weight loss.

Keywords: PLZF, food intake, energy expenditure, energy balance, energy deficit, glucocorticoid

Introduction

The brain constantly monitors the energy status of the body through various neuronal, hormonal, and metabolic signals to maintain energy balance (Gao and Horvath, 2007). The brain achieves this goal by regulating effector pathways controlling feeding behavior and energy expenditure and in doing so, integrates various environmental signals to mount coordinated responses to optimize the survival of an organism. The hypothalamus is an essential brain structure for this critical homeostatic mechanism and involved in multiple aspects of hormonal, behavioral, and autonomic responses that control feeding and energy consumption (Coll and Yeo, 2013). The ARC is the primary sensory region that receives neuronal and humoral signals related to energy balance and probably the most studied site regarding feeding regulation. The ARC contains two intermingled and counteracting neuronal populations that express Agrp/Npy and proopiomelanocortin (Pomc), respectively, and while Agrp/Npy neurons promote feeding, Pomc neurons promote satiety (Andermann and Lowell, 2017). These neurons project to the PVH to exert their function, among other areas (Gao and Horvath, 2007). In addition to feeding behavior control, the PVH regulates various neuroendocrine functions, energy expenditure, and glucose metabolism through multiple functionally distinct neuronal populations (Swanson and Sawchenko, 1980; Sutton et al., 2014; Roh et al., 2016).

We previously identified zinc finger and BTB domain containing 16 (Zbtb16) to be highly upregulated by acute cold exposure in the mouse hypothalamus (unpublished data). Zbtb16, also known as promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger (Plzf), causes human acute promyelocytic leukemia as a fusion protein with retinoic acid receptor α (Borrow et al., 1990; de The et al., 1990). During development, Zbtb16 plays a specific role of balancing the self-renewal and differentiation of stem cells in multiple organs (see (Liu et al., 2016) and references therein) but carries out diverse tissue-specific functions in adult. Nonetheless, the function of Zbtb16 has never been studied in adult brains while its expression and function have been described in developing central nervous system (Avantaggiato et al., 1995; Cook et al., 1995; Gaber et al., 2013; Lin et al., 2019). More careful expression analysis in the brain revealed Zbtb16 expression in two hypothalamic nuclei, the PVH and the ARC, that are critical for the control of energy balance. Therefore, we set out to uncover the function of hypothalamic Zbtb16 in metabolic regulation in these two nuclei by genetically targeting its expression and modulating neuronal activity.

In the current study, we describe the expression of Zbtb16 in the mouse brain and the induction of its expression by various energy deficit conditions via GC signaling in the PVH and the ARC. We demonstrate that Zbtb16 in the PVH (Zbtb16PVH) is important for cold-induced thermogenic response and glycemic control while Zbtb16 in the ARC (Zbtb16ARC) modulates feeding behavior. Therefore, this newly identified transcription factor Zbtb16 may be an important component for responses to energy deficit and contribute to overall energy homeostasis.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Pennington Biomedical Research Center (protocol # 1043). Mice were housed at 22–24°C with a 12:12 light:dark cycle. Laboratory rodent diet (5001, LabDiet) and water were available ad libitum unless stated otherwise. For investigation of Zbtb16 induction by cold, overnight fasting, and 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2DG), and Zbtb16 KD in the PVH or the ARC, C57BL/6J mice (000664, The Jackson Laboratory, RRID: IMSR_JAX:000664) were used at 2–4 months of age. Zbtb16-Cre mice were originally generated by Dr. Albert Bendelac at University of Chicago and obtained through the Jackson Laboratory (024529, The Jackson Laboratory, RRID: IMSR_JAX:024529) (Constantinides et al., 2014). Npy-GFP mice (006417, The Jackson Laboratory, RRID: IMSR_JAX:006417) and single-minded 1 (Sim1)-Cre mice (006395, The Jackson Laboratory, RRID: IMSR_JAX:006395) were created by Dr. Bradford Lowell at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard University and obtained through the Jackson Laboratory (Balthasar et al., 2005; van den Pol et al., 2009). L10-GFP mice were created by Dr. Andrew McMahon at University of Southern California and obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (024750, The Jackson Laboratory, RRID: IMSR_JAX:024750) (Liu et al., 2014). Both male and female mice were used in all experiments and no sex difference was observed in any measurement.

Zbtb16 mRNA Expression Analysis

RNA from the whole mouse hypothalamus or microdissected PVH or ARC was purified with TRIzol Reagent (#15596, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and cDNA was synthesized with SuperScript VILO cDNA synthesis kit (#11754050, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Zbtb16 mRNA expression was analyzed with the TaqMan assay method (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using the 7900HT real-time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). β-actin was used as a reference gene for relative quantification.

For investigation of hypothalamic Zbtb16 expression at different temperature, C57BL/6J mice were exposed to cold (4°C), room temperature (RT, 22°C), and warm (35°C) for 3 h. Brains were harvested and the whole hypothalami were isolated on ice and snap-frozen with liquid nitrogen. For acute cold exposure, C57Bl/6J mice were exposed to 4°C for 4 h before brains were taken out and different brain areas were isolated on ice using the mouse matrix (#RBM-2000C, ASI Instruments). Microdissected brain areas were immediately frozen with liquid nitrogen and kept at −80°C until further analysis.

For overnight fasting, C57BL/6J mice were fasted overnight for ∼16 h by removing food pellets from the food hoppers and changing the cage bottoms to clean ones. For the fed condition, cage bottoms were changed without removing food pellets. Water was freely available in both conditions. In the next morning, brains were harvested and different areas were isolated as described above.

For 2DG injection, C57BL/6J mice were injected with 600 mg/kg 2DG in saline (IP) and brains were harvested 4 h later and different areas were isolated as described above. Control mice were injected with saline (IP).

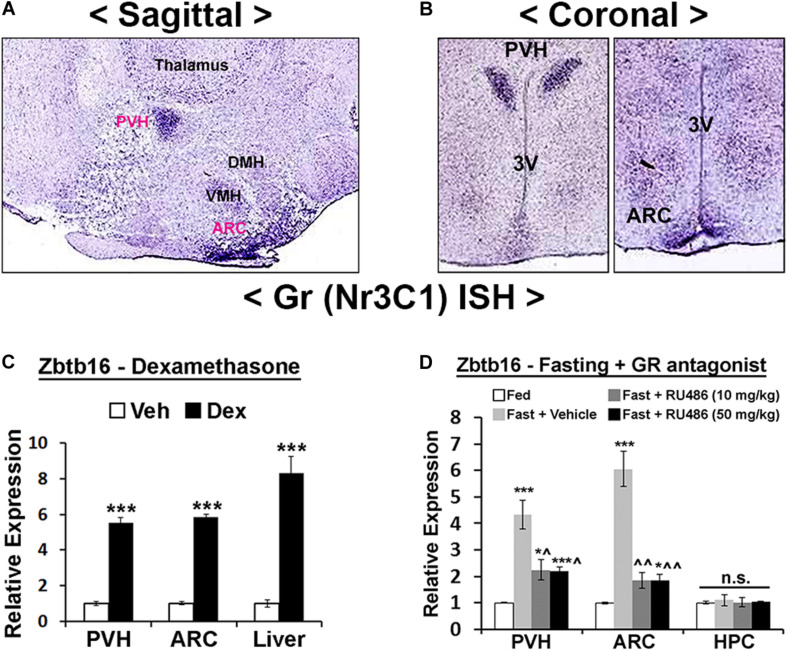

For the testing of glucocorticoid receptor (GR)-mediated Zbtb16 induction, C57BL/6J mice were injected with 10 mg/kg dexamethasone (Dex, #1126, Tocris) in 1% ethanol in PBS (IP) for 4 h before brains were harvested and different areas were isolated as described above. Control mice were injected with 1% ethanol in PBS (IP). To test how the inhibition of GR affects Zbtb16 induction by fasting, C57BL/6J mice were fasted overnight and vehicle (DMSO), 10 mg/kg or 50 mg/kg RU486/mifepristone (#1479, Tocris) in DMSO (IP) was injected. Brains were harvested 5 h later and different areas were isolated as described above.

Immunohistochemistry and Histological Analysis

Mice were deeply anesthetized by isoflurane and brains were harvested by transcardial perfusion with 10% formalin. Brains were postfixed in 10% formalin at 4°C overnight and cryoprotected in 30% sucrose. Brains were sliced at 30 μm thickness into 4 series with a sliding microtome and processed to free-floating immunohistochemistry (IHC). Primary antibodies used in this study are chicken anti-GFP (ab13970, Abcam; 1:1000, RRID: AB_300798), rabbit anti-Trh (Dr. Eduardo A. Nillni, Brown University; 1:1000, EAN: pYE26), rabbit anti-Crh (T-4414.0050, Peninsula Laboratories, 1:1000, RRID: AB_518268), rabbit anti-Oxt (20068, Immunostar, 1:2000, RRID: AB_572258), rabbit anti-Avp (20069, Immunostar, 1:2000, RRID: AB_572219), rabbit anti-Nos1 (61–7000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, 1:500, RRID: AB_2313734), rabbit anti-Pomc (G-029-30, Phoenix Pharmaceuticals Inc., 1:500, RRID: AB_2617186), and rabbit anti-Zbtb16 (HPA-001499, Millipore Sigma, 1:500, RRID: AB_1079640). Secondary antibodies used in this study are donkey anti-chicken IgY Alexa Fluor 488 (703-546-155, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories; 1:200, RRID: AB_2340376) and donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 594 (A-21207, Thermo Fisher Scientific; 1:200, RRID: AB_141637).

Viruses and Stereotaxic Surgeries

Stereotaxic injection of adeno-associated virus (AAV) was performed as previously described (Rezai-Zadeh et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2018). Briefly, mice were placed on a stereotaxic alignment system (#1900, David Kopf Instruments) and maintained anesthetized by 1–2% isoflurane during surgeries. For Zbtb16 KD in the PVH or the ARC, AAV9-U6/H1-Zbtb16 siRNA-GFP (AAV-Zbtb16 siRNA, 1.0 × 1012 vg/ml, Applied Biological Materials Inc., Richmond, BC, Canada) or AAV9-U6/H1-scrambled siRNA-GFP (AAV-Scrambled siRNA, 1.0 × 1012 vg/ml, Applied Biological Materials Inc., Richmond, BC, Canada) was injected bilaterally at 200 nl per site (400 nl total per animal). Virus was injected with a guide cannula and injection set (Plastics One) at 20 nl/30 s and the injection assembly was left in place for 5 min after the injection before removal and the skull and incision were closed with bone wax (Lukens, #901, Medline Industries) and wound clip (#203–1000, CellPoint Scientific). The coordinate for the PVH injection was AP: −0.6 mm, ML: ±0.4 mm, DV: −4.8 mm from the bregma, and for the ARC injection was AP: −1.45 mm, ML: ±0.3 mm, DV: −5.8 mm from the bregma.

For chemogenetic stimulation of Zbtb16 neurons in the PVH or the ARC, we injected AAV5-hSyn-DIO-hM3Dq-mCherry (AAV-DREADD-Gq, 3.8 × 1012 vg/ml, University of North Carolina Vector Core) or AAV5-hSyn-DIO-mCherry (AAV-Control, 5.2 × 1012 vg/ml, University of North Carolina Vector Core) bilaterally at 150 nl per site (300 nl total per animal) in Zbtb16-Cre mice with the same coordinates described above for Zbtb16 KD.

Knockdown of Zbtb16 in the PVH and the ARC

C57BL/6J mice were injected with either AAV-Scrambled siRNA or AAV-Zbtb16 siRNA in the PVH or the ARC at 2–4 months of age. The DNA sequence for scrambled siRNA is 5′-GGG TGA ACT CAC GTC AGA A-3′. For Zbtb16 KD, 4 pooled siRNAs were expressed and their sequences are 5′-TGA GAT CCT CTT CCA CCG AAA CAG CCA GC-3′, 5′-CAT CTT TAT CTC GAA GCA TTC CAG CGA GG-3′, 5′-GTG GAC AGC TTG ATG AGT ATA GGA CAG TC-3′, 5′-AGT GCC AGA GAG CTG CAT TAT GGG AGA GA-3′. Approximately 3 weeks after virus injection, mice were housed in the PhenoMaster indirect calorimetry system (TSE systems) to measure energy expenditure, food intake, locomotor activity, and respiratory exchange ratio. Body composition was measured at the beginning of indirect calorimetry with a Minispec LF110 NMR analyzer (Bruker Biospin) and energy expenditure was normalized with lean body mass because we did not observe body composition difference between groups. Mice were housed at 23°C and acclimated for 3 days before being subject to manipulations. For acute cold exposure, chamber temperature was lowered to 10°C at 9 am and raised back to 23°C at 4 pm (total 7 h). For overnight fasting, food was removed and cage bottoms were replaced with clean ones at 5 pm, and food was provided back at 9 am the next morning (total 16 h).

Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT) was conducted by fasting mice overnight, injecting glucose in the next morning (2 mg/g, IP), and measuring blood glucose level at 0 min and every 30 min for 2 h. A small amount of blood was taken from the tail vein and blood glucose was measured with glucose strips and a glucometer (OneTouch Ultra Strips and OneTouch Ultra glucometer, LifeScan Inc).

Validation of Zbtb16 siRNA in Mouse Brown Adipocytes

An immortalized brown preadipocyte cell line (Uldry et al., 2006) was cultured and induced for differentiation as described previously (Chang et al., 2010). Briefly, preadipocytes were grown to confluence in DMEM culture medium supplemented with 20 nM insulin and 1 nM T3 (differentiation medium) on a 48-well plate. Differentiation was then induced by incubating the cells in differentiation medium supplemented with 0.5 mM isobutylmethylxanthine, 0.5 μM Dex, and 0.125 mM indomethacin for 48 h. Thereafter, the cells were maintained in differentiation medium until day 7. For AAV-mediated silencing of Zbtb16 expression, differentiated brown adipocytes were infected with AAV expressing scrambled (control) or Zbtb16 siRNA for 16 h and Zbtb16 mRNA expression was analyzed 72 h after infection. AAVs were infected at two different titers, 104 MOI and 105 MOI. For the induction of Zbtb16 gene expression, differentiated brown adipocytes were serum-starved for 8 h and treated with vehicle or dexamethasone (10 μM) for 5 h (from hour 3 to hour 8) before the collection of mRNA.

Chemogenetic Stimulation of Zbtb16 Neurons in the PVH and the ARC

We injected either AAV-DREADD-Gq or AAV-Control into the PVH or the ARC of Zbtb16-Cre mice (Constantinides et al., 2014) at 2–4 months of age as described above. Mice were used for experiments 3 weeks after the virus injection. Mice with the PVH virus injection were injected with clozapine-N-oxide (CNO, C0832, Millipore Sigma) at 1 mg/kg, IP and rectal temperature was measure every 20 min for 2 h with a micro thermometer (227-193, ThermoWorks). Mice with the ARC virus injection were injected with either PBS or CNO (1 mg/kg, IP) in the morning and food weight was measured at time 0, 2, and 4 h to calculate 2 and 4 h food intake. 10 days later, the injection was reversed and the food intake was measured again in the same mice to compare PBS vs. CNO. 4 h food intake after CNO injection was compared to the amount of food consumed for 4 h after overnight fasting in the same mice. Both PVH- and ARC-injected mice were housed in Comprehensive Laboratory Animal Monitoring System (CLAMS; Columbus Instruments) to measure energy expenditure, locomotor activity, and RER upon chemogenetic stimulation of Zbtb16 neurons in the PVH or the ARC. CNO was injected at 1.0 mg/kg, IP in the morning and 2 h data were averaged for each parameter. Each mouse was administered with PBS and CNO, and the injection order was randomly assigned and counterbalanced.

Statistical Analysis

Data are represented as mean ± SEM. All statistical analyses were done with SPSS 24 (IBM) and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. In all graphs, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001. Some bar graphs used letters to indicate statistical significance between comparisons. For more detailed information, see section “Results” and Figures 1–6.

FIGURE 1.

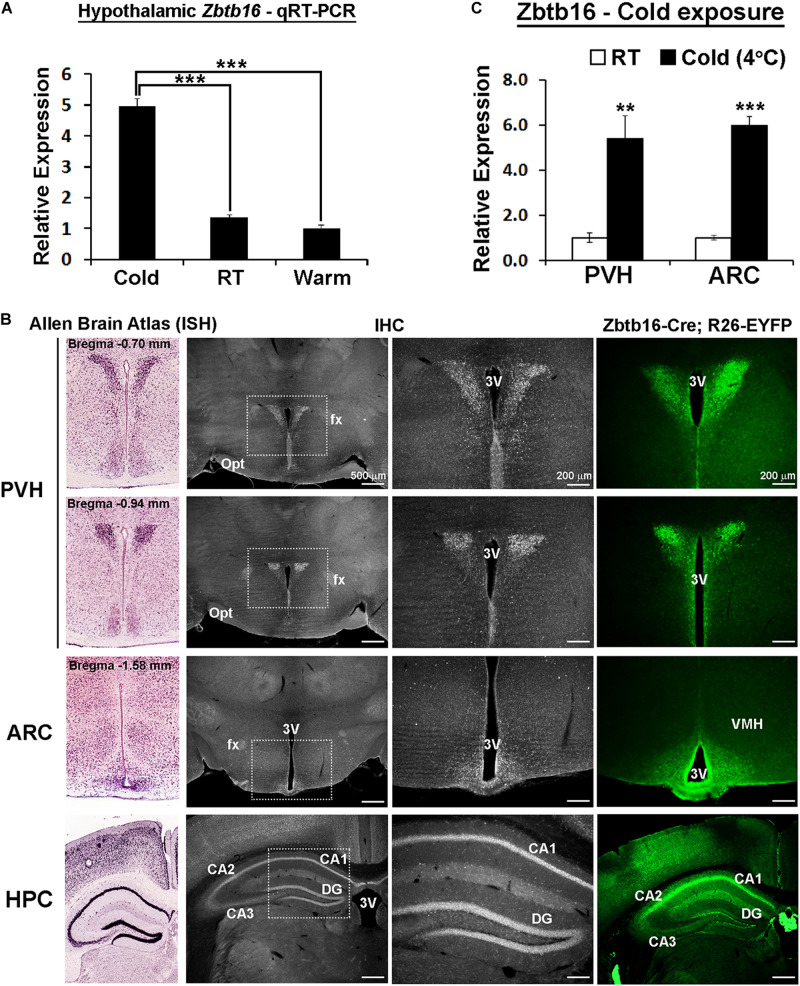

Zbtb16 expression is induced by cold exposure in the hypothalamic paraventricular and arcuate nuclei. (A) Zbtb16 mRNA expression is induced in the mouse hypothalamus by 3 h of cold exposure (Cold at 4°C, n = 4; RT at 22°C, n = 4; Warm at 35°C, n = 4; one-way ANOVA). (B) mRNA expression (from Allen Brain Atlas, far left column, experiment #71717125), protein expression (IHC, two middle columns), and reporter expression (EYFP expression driven by Zbtb16-Cre, far right column) show consistent expression in the PVH, ARC, and hippocampus (HPC). (C) Zbtb16 mRNA expression is increased by 4 h of cold exposure in both the PVH and the ARC (4°C, n = 5; RT, n = 5; independent t-test in each area). Data were represented by mean ± SEM. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. 3V, 3rd ventricle; CA1, field CA1 hippocampus; CA2, field CA2 hippocampus; CA3, field CA3 hippocampus; DG, dentate gyrus; fx, fornix; Opt, optic tract; VMH, ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus.

FIGURE 6.

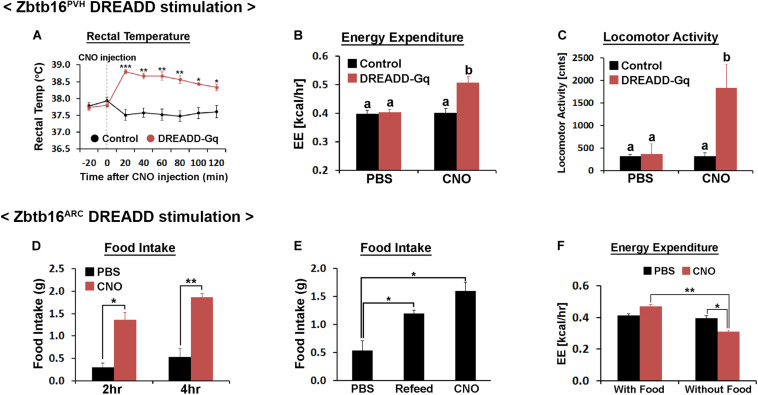

Chemogenetic stimulation of Zbtb16PVH or Zbtb16ARC neurons. (A) Chemogenetic stimulation of Zbtb16PVH neurons increased rectal temperature in mice (control, n = 9; DREADD-Gq, n = 3; repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni pairwise comparisons). (B) Chemogenetic stimulation of Zbtb16PVH neurons increased 2 h energy expenditure in mice after CNO injection (control, n = 9; DREADD-Gq, n = 3; repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni pairwise comparisons). Bars with different letters denote statistical significance at p < 0.01. (C) Chemogenetic stimulation of Zbtb16PVH neurons increased 2 h locomotor activity in mice after injection (control, n = 9; DREADD-Gq, n = 3; repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni pairwise comparisons). Bars with different letters denote statistical significance at p < 0.01. (D) Chemogenetic stimulation of Zbtb16ARC neurons increased daytime food intake measured at 2 and 4 h after injection (n = 4; repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni pairwise comparisons). (E) Chemogenetic stimulation of Zbtb16ARC neurons increased 4 h food intake during daytime which is comparable to the amount of food eaten after overnight fasting in the same mice (n = 4; repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni pairwise comparisons). (F) Chemogenetic stimulation of Zbtb16ARC neurons decreased 2 h energy expenditure only when food was absent (n = 4, repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni pairwise comparisons). CNO was injected at 1 mg/kg, IP in all experiments. Data are represented by mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Results

Zbtb16 Expression Is Induced by Cold Exposure in the Hypothalamic Paraventricular and Arcuate Nuclei

Zbtb16 was first identified from our previous genetic screen in the mouse hypothalamus as a gene upregulated by 3 h of cold exposure (Figure 1A and unpublished data). More detailed expression analysis revealed that Zbtb16 is expressed in the PVH and the ARC in the hypothalamus even though it shows the strongest expression in the hippocampus in the brain (Figure 1B). We did not detect any significant Zbtb16 expression in other hypothalamic areas. Zbtb16 mRNA expression was induced by acute cold exposure in both the PVH and the ARC to a similar degree when its expression was analyzed with microdissected brain tissues (Figure 1C).

Zbbtb16 in the PVH Contributes to Cold-Induced Thermogenesis and Glycemic Control

Because of the expression of Zbtb16 in two nuclei that play critical roles in energy homeostasis and its induction by cold exposure, we carried out a series of experiments to figure out its role in each nucleus. Sim1 is a transcription factor that marks PVH neurons (Balthasar et al., 2005), and the majority of Zbtb16 neurons in the PVH co-expressed Sim1-Cre-driven GFP reporter even though Zbtb16 expression is restricted to the anterior half of the PVH (Figure 2A). The PVH harbors heterogeneous neuronal populations that are involved in numerous homeostatic functions and marked by different gene expressions. Double IHC of Zbtb16 with several of these markers (i.e., Crh, Trh, Avp, Oxt, and Nos1) revealed significant co-expression of Zbtb16 with all marker genes tested (Figure 2B, 95.3 ± 0.01% of Crh, 93.0 ± 0.02 % of Trh, 92.3 ± 0.01% of Avp, 94.7 ± 0.01% of Oxt, and 88.0 ± 0.02% of Nos1 neurons co-express Zbtb16; n = 3 for each marker).

FIGURE 2.

Zbtb16 in the PVH contributes to cold-induced thermogenesis and glycemic control. (A) Zbtb16 protein expression (IHC, red) was compared to Sim1 expression (Sim1-Cre; L10-GFP reporter, green) in the PVH. (B) Zbtb16 is expressed in multiple cell types in the PVH including neurons expressing Crh, Trh, Avp, Oxt, and Nos1. Scale bar is 200 μm. (C) Schematic diagram showing bilateral injection of AAV expressing siRNA against Zbtb16 in the PVH and a representative histological image showing correct targeting of the virus, shown by GFP expression. Scale bar is 200 μm. (D) Zbtb16PVH KD mice (red, n = 6) exhibited attenuated cold (10°C)-induced thermogenic response compared to mice injected with AAV expressing scrambled siRNA (black, n = 4). 24 h energy expenditure data were analyzed by repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni pairwise comparisons. (E) Average energy expenditure during cold exposure (7 h from 9 am to 4 pm) was significantly lower in Zbtb16PVH KD mice (red, n = 6) compared to control mice (black, n = 4). Data were analyzed by independent t-test. (F) Food intake during cold exposure was not different between groups (scrambled siRNA, n = 4; Zbtb16 siRNA, n = 6; independent t-test). (G) Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT) revealed slightly improved glucose tolerance in Zbtb16PVH KD mice (red, n = 6) compared to control mice (black, n = 4). Data were analyzed by repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni pairwise comparisons. (H) Area under the curve comparison for the IPGTT data shown in (G) (scrambled siRNA, n = 4; Zbtb16 siRNA, n = 6; independent t-test). Data were represented by mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

To test the relevance of Zbtb16 in whole body physiology, we injected AAV expressing a pool of siRNAs against Zbtb16 (AAV-Zbtb16 siRNA) bilaterally into the PVH in mice (Figure 2C). Zbtb16 expression was shown to be induced in brown adipocytes by the GR agonist Dex (Chen et al., 2014), and AAV-Zbtb16 siRNA attenuated this induction by around 50% (Supplementary Figures 1A,B). We first tested how Zbtb16 KD in the PVH (Zbtb16PVH KD) affected physiological responses to cold exposure. While there was no change in energy expenditure between mice injected with AAV-Zbtb16 siRNA and mice injected with AAV-scrambled siRNA at room temperature (RT, 22°C; Supplementary Figure 2A), Zbtb16PVH KD mice showed reduced capacity to increase their energy expenditure during cold exposure (Figures 2D,E). Because multiple neuronal populations in the PVH contribute to the regulation of feeding behavior (Balthasar et al., 2005; Krashes et al., 2014; Pei et al., 2014; Sutton et al., 2014), we also tested whether Zbtb16PVH plays a role in controlling feeding behavior. However, hyperphagic response during cold exposure and diurnal food intake were not affected by Zbtb16PVH KD (Figure 2F and Supplementary Figures 2A,B). IPGTT showed a slightly improved glycemic control in Zbtb16PVH KD mice (Figure 2G) even though the area under the curve comparison did not reach statistical significance (Figure 2H).

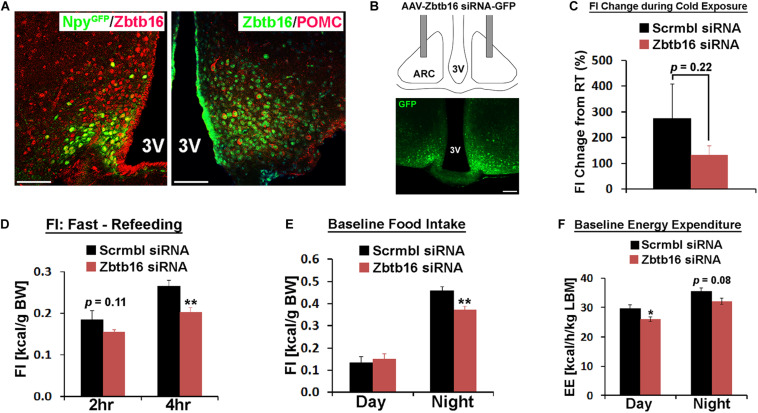

Zbtb16 in the ARC Contributes to Food Intake Control

In the ARC, two counteracting neuronal populations play a critical role in food intake regulation and overall energy homeostasis. Consistent with previous single-cell transcriptome analyses (Henry et al., 2015; Campbell et al., 2017), Zbtb16 is expressed in both orexigenic Agrp/Npy neurons and anorexigenic Pomc neurons even though not all Pomc neurons co-expressed Zbtb16 while all Agrp/Npy neurons co-expressed Zbtb16 (Figure 3A, cell counting not shown). Similar to the PVH, we bilaterally injected AAV-Zbtb16 siRNA into the ARC in mice and investigated the role of Zbtb16 in this nucleus (Figure 3B). While thermogenic response to cold was not affected in Zbtb16ARC KD mice (Supplementary Figure 3A), the amount of food consumed during cold exposure was reduced in these mice even though it did not reach the statistical significance (Figure 3C). Furthermore, Zbtb16ARC KD mice ate less during the refeeding after overnight fasting and the dark cycle (Figures 3D,E). Interestingly, baseline energy expenditure was slightly lower in Zbtb16ARC KD mice compared to control mice (Figure 3F) even though hypometabolic response to fasting was not different between groups (Supplementary Figure 3B). The lower metabolic rate in Zbtb16ARC KD mice could be an adaptive response to reduced feeding as the body weight of these mice was not different from control mice (data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

Zbtb16 in the ARC contributes to food intake control. (A) Representative histological images showing co-expression of Zbtb16 with Npy-GFP or Pomc in the ARC. Scale bar is 50 μm. (B) Schematic diagram showing bilateral injection of AAV expressing siRNA against Zbtb16 in the ARC and a representative histological image showing correct targeting of the virus, shown by GFP expression. (C) Zbtb16ARC KD mice (red, n = 7) showed reduced food intake during cold exposure (10°C for 7 h from 9 am to 4 pm) compared to mice injected with AAV expressing scrambled siRNA (black, n = 4). Data were analyzed by independent t-test. (D) Zbtb16ARC KD mice exhibited reduced food intake after overnight fasting (scrambled siRNA, n = 4; Zbtb16 siRNA, n = 7; repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni pairwise comparisons). (E) Zbtb16ARC KD mice showed decreased nighttime food intake at baseline (scrambled siRNA, n = 4; Zbtb16 siRNA, n = 7; repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni pairwise comparisons). (F) Zbtb16ARC KD mice (red, n = 7) showed decreased baseline energy expenditure compared to control mice (black, n = 4). Data were analyzed by repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni pairwise comparisons. Data were represented by mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

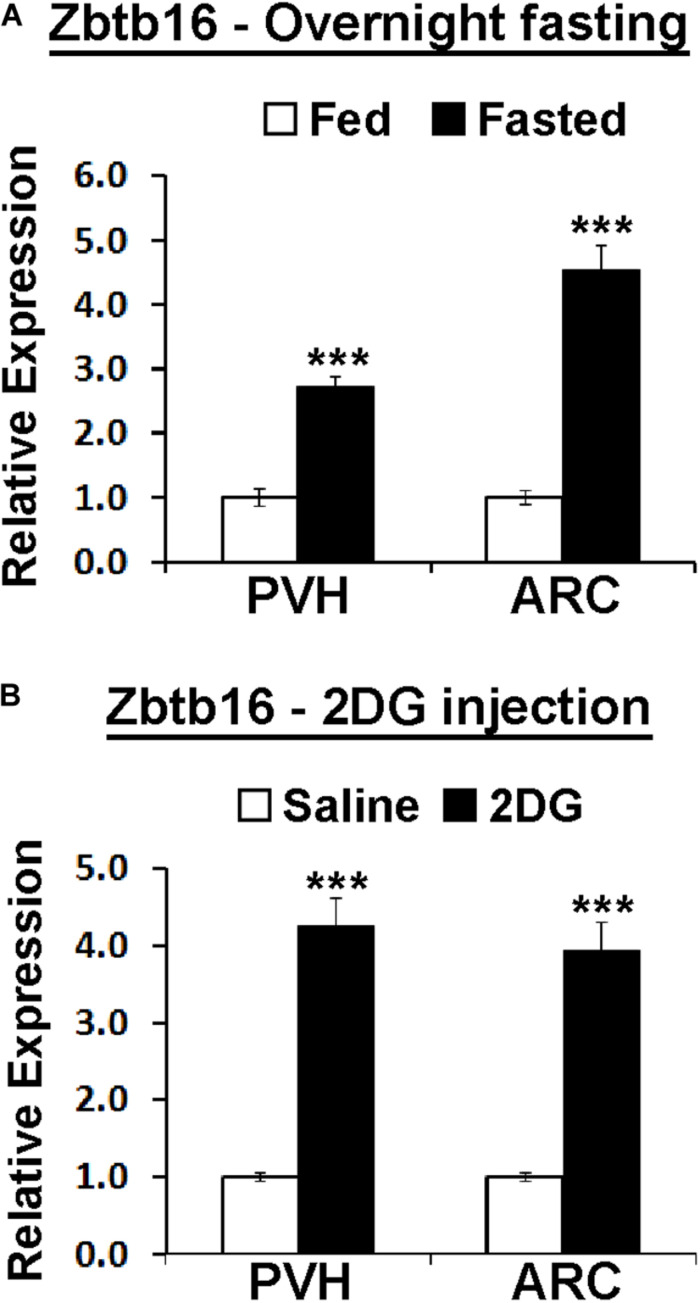

Zbtb16 Expression Is Induced by Energy Deficit in the PVH and the ARC via Glucocorticoid Receptor Signaling

Because of the effect of Zbtb16ARC KD on food intake, we investigated whether the negative energy balance created by overnight fasting can induce Zbtb16 expression similarly to cold exposure. Indeed, overnight fasting in mice induced Zbtb16 expression in both the PVH and the ARC (Figure 4A). Zbtb16 induction by overnight fasting prompted us to test whether a different energy deficit signal can induce Zbtb16 expression. 2DG is a glucoprivic agent that blocks glycolysis and triggers strong counter-regulatory responses to elevate blood glucose levels (Ritter et al., 2001). The injection of 2DG (600 mg/kg, IP) robustly induced Zbtb16 expression in both the PVH and the ARC (Figure 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Hypothalamic Zbtb16 is induced by energy deficit. (A) Zbtb16 is induced by overnight fasting in both the PVH and the ARC (fed, n = 5; fasted, n = 6; independent t-test in each area). (B) Glucopenia induced by IP injection of 2DG (600 mg/kg) induced Zbtb16 in both the PVH and the ARC (saline, n = 5; 2DG, n = 5; independent t-test in each area). Tissues were harvested 4 h after the 2DG injection. Data were represented by mean ± SEM, ***p < 0.001.

We next probed the upstream mechanisms responsible for Zbtb16 induction. Cold exposure, overnight fasting, and 2DG injection all induce an energy deficit state that triggers the release of GCs from the adrenal gland (Wilkerson et al., 1974; Yi and Baram, 1994; Makimura et al., 2003; Magomedova and Cummins, 2016). Furthermore, previous studies showed induction of Zbtb16 in several non-neuronal cells by GCs (Fahnenstich et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2014; Naito et al., 2015). In the hypothalamus, GR shows a similarly enriched expression pattern in the PVH and the ARC as Zbtb16 (Figures 5A,B), and the injection of the GR agonist Dex in mice robustly induced Zbtb16 in the PVH and the ARC (Figure 5C). The induction of Zbtb16 by overnight fasting was strongly inhibited by the injection of the GR antagonist RU486/Mifepristone (Figure 5D). Interestingly, Zbtb16 was neither induced by overnight fasting nor suppressed by RU486 in the hippocampus, implying a different transcriptional regulation of Zbtb16 in this area (Figure 5D).

FIGURE 5.

Hypothalamic Zbtb16 is induced by glucocorticoid receptor signaling. (A,B) GR mRNA expression in the mouse hypothalamus shows its enrichment in the PVH and ARC (Allen Brain Atlas, experiment #727 and #728). (C) IP injection of GR agonist Dex (10 mg/kg) induced Zbtb16 in the PVH, ARC, and liver (vehicle, n = 6; Dex, n = 6; independent t-test). (D) Zbtb16 induction by overnight fasting was significantly attenuated by GR antagonist RU486/Mifepristone (IP at 10 mg/kg or 50 mg/kg for 5 h) in the PVH and ARC. Neither fasting nor RU486 affected Zbtb16 expression in the hippocampus (HPC) (n = 5 for each condition; one-way ANOVA in each area). Data are represented by mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. ^p < 0.05, ^^p < 0.01 compared to the “Fast + Vehicle” condition in (D).

Chemogenetic Stimulation of Zbtb16 Neurons

While the intracellular mechanisms downstream of Zbtb16 is currently elusive, we reasoned that they are likely to involve the modulation of neuronal activity. Therefore, we hypothesized that chemogenetic stimulation of Zbtb16PVH neurons would result in a change in energy expenditure while that of Zbtb16ARC neurons would affect food intake. We injected AAV-DREADD-Gq bilaterally into Zbtb16-Cre mice in the PVH or the ARC for a chemogenetic stimulation of Zbtb16 neurons in each area (Supplementary Figure 4).

Injection of CNO (1 mg/kg, IP) in Zbtb16PVH DREADD-Gq mice increased core temperature, which lasted at least for 2 h (Figure 6A). Consistent with this phenotype, energy expenditure during the same period increased about 25% in Zbtb16PVH DREADD-Gq mice with CNO injections (Figure 6B). Locomotor activity during the same span also increased in Zbtb16PVH DREADD-Gq mice with CNO (Figure 6C), consistent with the fact that Zbtb16 is expressed in Crh neurons in the PVH (Fuzesi et al., 2016). Food intake was not affected by chemogenetic stimulation of Zbtb16PVH neurons (data not shown), corroborating findings from the Zbtb16PVH KD study.

Chemogenetic stimulation of Zbtb16ARC neurons increased daytime food intake in fed mice, which was comparable to the amount of food consumed after overnight fasting in the same mice (Figures 6D,E). Accordingly, locomotor activity in Zbtb16ARC DREADD-Gq mice increased sharply with CNO injection in the absence of food, reflecting food-seeking behavior. These phenotypes are reminiscent of the stimulation of Agrp/Npy neurons (Aponte et al., 2011; Krashes et al., 2011). Energy expenditure after CNO injection decreased in Zbtb16ARC DREADD-Gq mice when food was not provided (Figure 6F), again consistent with what was observed with chemogenetic stimulation of Agrp/Npy neurons (Krashes et al., 2011). Rectal temperature was not affected when Zbtb16ARC neurons were stimulated (data not shown).

Discussion

In this study, we describe for the first time the expression and potential role of the newly identified transcription factor Zbtb16 in the hypothalamus. We uncovers that Zbtb16 expression is induced by various conditions of energy deficit in the PVH and the ARC through GC signaling. This induction contributes to modulating energy expenditure, food intake, and glycemic control to properly respond to the energy deficit state. Chemogenetic stimulation of Zbtb16 neurons in the PVH and the ARC modulates energy expenditure and food intake, respectively, consistent with results from Zbtb16 KD in each nucleus, suggesting that Zbtb16 induction is likely to affect neuronal activity. However, many unanswered questions remain.

The most important unanswered question would be how Zbtb16 affects physiology and behavior. As a transcription factor, Zbtb16 could regulate the expression of neuropeptides, ion channels, or various receptors to influence the response to incoming signals and/or the signaling to downstream neurons. Zbtb16 is expressed in various tissues and carries out diverse biological functions through regulation of tissue-specific target genes (Barna et al., 2000; Kovalovsky et al., 2008; Savage et al., 2008; Hobbs et al., 2010; Plaisier et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2014; Liska et al., 2017), making it difficult to postulate its mechanism in the hypothalamus. The fact that Zbtb16 is expressed in heterogeneous neuronal populations makes the issue more complicated because it is currently not clear whether Zbtb16 is equally induced by energy deficit in all neurons it is expressed or in a specific subpopulation, and whether it regulates the same genes in different neurons. Studies with selective ablation of Zbtb16 in different neuronal populations would greatly enhance our understanding of where and how Zbtb16 functions. Nevertheless, our findings provide important clues on how Zbtb16 functions in the hypothalamus. For example in the PVH, several neuronal populations (e.g., Mc4r, Pdyn, Trh, Pacap, and Nos1 neurons) have been shown to control feeding behavior (Krashes et al., 2014; Sutton et al., 2014; Li et al., 2019) but neither Zbtb16PVH KD nor Zbtb16PVH DREADD-Gq affected food intake, implying that Zbtb16 probably does not affect functions of these neurons. On the other hand, PVH Oxt neurons were shown to increase energy expenditure without affecting food intake through their projection to the spinal cord (Sutton et al., 2014), indicating a potential role of Zbtb16 in these neurons. Zbtb16 may also affects energy expenditure secondarily through the release of Trh as Trh was shown to increase energy expenditure (Mullur et al., 2014). Interestingly, Zbtb16PVH KD only affects cold-induced thermogenesis but not fasting-evoked hypometabolism even though the Zbtb16 levels elevate in both circumstances. This result indicates that Zbtb16 functions in a context-dependent manner and the Zbtb16 induction by energy deficit in the PVH is not related to energy expenditure. We reason that the major function of Zbtb16PVH during energy deficit is to control blood glucose levels even though Zbtb16PVH KD only mildly improved glucose tolerance.

In the ARC, Zbtb16ARC KD decreases food intake while chemogenetic stimulation of Zbtb16ARC neurons increases food intake, in line with Zbtb16 expression in AgRP/Npy neurons. Although Zbtb16 is also expressed in POMC neurons, previous single cell analyses showed that Zbtb16 is expressed at a higher level and induced more robustly by fasting in AgRP/Npy neurons (Henry et al., 2015; Campbell et al., 2017). Therefore, we speculate that the main function of Zbtb16 in the ARC is to promote feeding in the face of energy deficit downstream of GC signaling in Agrp/Npy neurons. This idea is congruent with previous studies that showed increased food intake by central GR stimulation (Debons et al., 1986; Zakrzewska et al., 1999; Cusin et al., 2001; Veyrat-Durebex et al., 2012). Slightly reduced energy expenditure in Zbtb16ARC KD mice may be an adaptive response to reduced food intake as we did not observe altered energy expenditure during cold exposure or fasting in the same mice. Nevertheless, the effect of Zbtb16ARC on energy expenditure will have to be investigated more carefully in future studies.

The fact that Zbtb16 expression is induced by GC signaling bears significant implications in Zbtb16’s involvement in energy homeostasis. In addition to their function in the periphery, GCs centrally control feeding behavior, energy expenditure, and autonomic output to peripheral organs (Zakrzewska et al., 1999; Cusin et al., 2001; Kellendonk et al., 2002; Bernal-Mizrachi et al., 2007; Veyrat-Durebex et al., 2012; Yi et al., 2012; Laryea et al., 2013; Solomon et al., 2015; Perry et al., 2019). More importantly, GCs are required for the development of both genetic and diet-induced obesity and interact with leptin signaling (Yukimura and Bray, 1978; Saito and Bray, 1984; Bray et al., 1992; Makimura et al., 2000; Perry et al., 2019). Therefore, central Zbtb16 may contribute to the control of energy balance and ultimately body weight downstream of GC signaling. However, we cannot rule out the regulation of Zbtb16 expression by other hormones or signaling molecules, as RU486 incompletely blocks the Zbtb16 induction by fasting. Factors released during energy deficit (e.g., ghrelin) or surplus (e.g., leptin, insulin) might very well be involved in the induction or suppression of Zbtb16 in the hypothalamus, respectively.

Several rare single nucleotide polymorphisms in the Zbtb16 locus have been associated with higher body mass index, waist to hip ratio, and LDL cholesterol levels in humans (Bendlova et al., 2017), and losing one copy of Zbtb16 caused reduced body weight and adiposity in rats (Liska et al., 2017) and mice (our own unpublished data). It is particularly interesting to investigate if Zbtb16 plays a role in weight regain after weight loss because the weight regain driven by enhanced appetite and reduced metabolic rate is a critical barrier for the long-term success of weight loss (Rosenbaum and Leibel, 2014).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Pennington Biomedical Research Center.

Author Contributions

SY conceptualized and planned the study. SY, HC, SP, and JL executed the experiments and analyzed the data. SY and JC wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by NIH P20GM103528 (SY), NIH 2P30-DK072476 (SY), and NIH R01DK104748 (JC). This work utilized the facilities of the Cell Biology and Bioimaging Core and Genomics Core supported in part by COBRE (NIH P30GM118430) and NORC (NIH P30DK072476) center grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins.2020.592947/full#supplementary-material

Zbtb16 knockdown validation by AAV-mediated expression of Zbtb16 siRNA. (A) In cultured brown adipocytes, Zbtb16 expression was highly induced by Dex treatment. Cells were serum-starved for 8 h and Dex was treated for 5 h (3 h into starvation). n = 4 for each condition (one-way ANOVA). (B) Dex (10 μM)-mediated Zbtb16 induction in cultured brown adipocytes was significantly attenuated by AAV-mediated expression of Zbtb16 siRNA. Scrambled siRNA was transduced at 105 MOI, Zbtb16 siRNA-Lo at 104 MOI, and Zbtb16 siRNA-Hi at 105 MOI (n = 2 for each condition; one-way ANOVA). Data are represented by mean ± SEM, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Zbtb16 knockdown in the PVH. (A,B) Zbtb16PVH KD affected neither energy expenditure nor food intake at baseline (scrambled siRNA, n = 4; Zbtb16 siRNA, n = 6; repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni pairwise comparisons). (C) Zbtb16PVH KD did not affect hypometabolic response during fasting (scrambled siRNA, n = 4; Zbtb16 siRNA, n = 6; independent t-test). Data are represented by mean ± SEM.

Zbtb16 knockdown in the ARC. (A,B) Zbtb16ARC KD affected neither cold-adaptive thermogenesis nor fasting-induced hypometabolism (scrambled siRNA, n = 4; Zbtb16 siRNA, n = 7; independent t-test). (C) Zbtb16ARC KD did not affect glucose tolerance (scrambled siRNA, n = 4; Zbtb16 siRNA, n = 7; repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni pairwise comparisons). Data are represented by mean ± SEM.

Chemogenetic Stimulation of Zbtb16 neurons. (A) Representative histological images showing the expression of cFos (neuronal activation) and mCherry (virus) in the PVH in Zbtb16PVH Control and DREADD-Gq mice. The brains were harvested 1 h after CNO injection at 1.0 mg/kg, IP. (B) Representative histological image showing the expression of cFos and mCherry in the ARC in Zbtb16PVH DREADD-Gq mice. The brains were harvested 1 h after CNO injection at 1.0 mg/kg, IP.

References

- Andermann M. L., Lowell B. B. (2017). Toward a wiring diagram understanding of appetite control. Neuron 95 757–778. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aponte Y., Atasoy D., Sternson S. M. (2011). AGRP neurons are sufficient to orchestrate feeding behavior rapidly and without training. Nat. Neurosci. 14 351–355. 10.1038/nn.2739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avantaggiato V., Pandolfi P. P., Ruthardt M., Hawe N., Acampora D., Pelicci P. G., et al. (1995). Developmental analysis of murine Promyelocyte Leukemia Zinc Finger (PLZF) gene expression: implications for the neuromeric model of the forebrain organization. J. Neurosci. 15 4927–4942. 10.1523/jneurosci.15-07-04927.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balthasar N., Dalgaard L. T., Lee C. E., Yu J., Funahashi H., Williams T., et al. (2005). Divergence of melanocortin pathways in the control of food intake and energy expenditure. Cell 123 493–505. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barna M., Hawe N., Niswander L., Pandolfi P. P. (2000). Plzf regulates limb and axial skeletal patterning. Nat. Genet. 25 166–172. 10.1038/76014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendlova B., Vankova M., Hill M., Vacinova G., Lukasova P., VejraZkova D., et al. (2017). ZBTB16 gene variability influences obesity-related parameters and serum lipid levels in Czech adults. Physiol. Res. 66 S425–S431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal-Mizrachi C., Xiaozhong L., Yin L., Knutsen R. H., Howard M. J., Arends J. J., et al. (2007). An afferent vagal nerve pathway links hepatic PPARalpha activation to glucocorticoid-induced insulin resistance and hypertension. Cell Metab. 5 91–102. 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrow J., Goddard A. D., Sheer D., Solomon E. (1990). Molecular analysis of acute promyelocytic leukemia breakpoint cluster region on chromosome 17. Science 249 1577–1580. 10.1126/science.2218500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray G. A., Stern J. S., Castonguay T. W. (1992). Effect of adrenalectomy and high-fat diet on the fatty Zucker rat. Am. J. Physiol. 262 E32–E39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J. N., Macosko E. Z., Fenselau H., Pers T. H., Lyubetskaya A., Tenen D., et al. (2017). A molecular census of arcuate hypothalamus and median eminence cell types. Nat. Neurosci. 20 484–496. 10.1038/nn.4495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J. S., Huypens P., Zhang Y., Black C., Kralli A., Gettys T. W. (2010). Regulation of NT-PGC-1alpha subcellular localization and function by protein kinase A-dependent modulation of nuclear export by CRM1. J. Biol. Chem. 285 18039–18050. 10.1074/jbc.m109.083121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Qian J., Shi X., Gao T., Liang T., Liu C. (2014). Control of hepatic gluconeogenesis by the promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger protein. Mol. Endocrinol. 28 1987–1998. 10.1210/me.2014-1164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coll A. P., Yeo G. S. (2013). The hypothalamus and metabolism: integrating signals to control energy and glucose homeostasis. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 13 970–976. 10.1016/j.coph.2013.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantinides M. G., McDonald B. D., Verhoef P. A., Bendelac A. (2014). A committed precursor to innate lymphoid cells. Nature 508 397–401. 10.1038/nature13047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook M., Gould A., Brand N., Davies J., Strutt P., Shaknovich R., et al. (1995). Expression of the zinc-finger gene PLZF at rhombomere boundaries in the vertebrate hindbrain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92 2249–2253. 10.1073/pnas.92.6.2249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusin I., Rouru J., Rohner-Jeanrenaud F. (2001). Intracerebroventricular glucocorticoid infusion in normal rats: induction of parasympathetic-mediated obesity and insulin resistance. Obes. Res. 9 401–406. 10.1038/oby.2001.52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de The H., Chomienne C., Lanotte M., Degos L., Dejean A. (1990). The t(15;17) translocation of acute promyelocytic leukaemia fuses the retinoic acid receptor alpha gene to a novel transcribed locus. Nature 347 558–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debons A. F., Zurek L. D., Tse C. S., Abrahamsen S. (1986). Central nervous system control of hyperphagia in hypothalamic obesity: dependence on adrenal glucocorticoids. Endocrinology 118 1678–1681. 10.1210/endo-118-4-1678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahnenstich J., Nandy A., Milde-Langosch K., Schneider-Merck T., Walther N., Gellersen B. (2003). Promyelocytic leukaemia zinc finger protein (PLZF) is a glucocorticoid- and progesterone-induced transcription factor in human endometrial stromal cells and myometrial smooth muscle cells. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 9 611–623. 10.1093/molehr/gag080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuzesi T., Daviu N., Wamsteeker Cusulin J. I., Bonin R. P., Bains J. S. (2016). Hypothalamic CRH neurons orchestrate complex behaviours after stress. Nat. Commun. 7:11937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaber Z. B., Butler S. J., Novitch B. G. (2013). PLZF regulates fibroblast growth factor responsiveness and maintenance of neural progenitors. PLoS Biol. 11:e1001676. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Q., Horvath T. L. (2007). Neurobiology of feeding and energy expenditure. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 30 367–398. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry F. E., Sugino K., Tozer A., Branco T., Sternson S. M. (2015). Cell type-specific transcriptomics of hypothalamic energy-sensing neuron responses to weight-loss. eLife 4:e09800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs R. M., Seandel M., Falciatori I., Rafii S., Pandolfi P. P. (2010). Plzf regulates germline progenitor self-renewal by opposing mTORC1. Cell 142 468–479. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellendonk C., Eiden S., Kretz O., Schutz G., Schmidt I., Tronche F., et al. (2002). Inactivation of the GR in the nervous system affects energy accumulation. Endocrinology 143 2333–2340. 10.1210/endo.143.6.8853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalovsky D., Uche O. U., Eladad S., Hobbs R. M., Yi W., Alonzo E., et al. (2008). The BTB-zinc finger transcriptional regulator PLZF controls the development of invariant natural killer T cell effector functions. Nat. Immunol. 9 1055–1064. 10.1038/ni.1641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krashes M. J., Koda S., Ye C., Rogan S. C., Adams A. C., Cusher D. S., et al. (2011). Rapid, reversible activation of AgRP neurons drives feeding behavior in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 121 1424–1428. 10.1172/jci46229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krashes M. J., Shah B. P., Madara J. C., Olson D. P., Strochlic D. E., Garfield A. S., et al. (2014). An excitatory paraventricular nucleus to AgRP neuron circuit that drives hunger. Nature 507 238–242. 10.1038/nature12956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laryea G., Schutz G., Muglia L. J. (2013). Disrupting hypothalamic glucocorticoid receptors causes HPA axis hyperactivity and excess adiposity. Mol. Endocrinol. 27 1655–1665. 10.1210/me.2013-1187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M. M., Madara J. C., Steger J. S., Krashes M. J., Balthasar N., Campbell J. N., et al. (2019). The paraventricular hypothalamus regulates satiety and prevents obesity via two genetically distinct circuits. Neuron 102 653–667.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H. C., Ching Y. H., Huang C. C., Pao P. C., Lee Y. H., Chang W. C., et al. (2019). Promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger is involved in the formation of deep layer cortical neurons. J. Biomed. Sci. 26:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liska F., Landa V., Zidek V., Mlejnek P., Silhavy J., Simakova M., et al. (2017). Downregulation of Plzf gene ameliorates metabolic and cardiac traits in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Hypertension 69 1084–1091. 10.1161/hypertensionaha.116.08798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Krautzberger A. M., Sui S. H., Hofmann O. M., Chen Y., Baetscher M., et al. (2014). Cell-specific translational profiling in acute kidney injury. J. Clin. Invest. 124 1242–1254. 10.1172/jci72126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T. M., Lee E. H., Lim B., Shyh-Chang N. (2016). Concise review: balancing stem cell self-renewal and differentiation with PLZF. Stem Cells 34 277–287. 10.1002/stem.2270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magomedova L., Cummins C. L. (2016). Glucocorticoids and metabolic control. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 233 73–93. 10.1007/164_2015_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makimura H., Mizuno T. M., Isoda F., Beasley J., Silverstein J. H., Mobbs C. V. (2003). Role of glucocorticoids in mediating effects of fasting and diabetes on hypothalamic gene expression. BMC Physiol. 3:5. 10.1186/1472-6793-3-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makimura H., Mizuno T. M., Roberts J., Silverstein J., Beasley J., Mobbs C. V. (2000). Adrenalectomy reverses obese phenotype and restores hypothalamic melanocortin tone in leptin-deficient ob/ob mice. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 49 1917–1923. 10.2337/diabetes.49.11.1917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullur R., Liu Y. Y., Brent G. A. (2014). Thyroid hormone regulation of metabolism. Physiol. Rev. 94 355–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naito M., Vongsa S., Tsukune N., Ohashi A., Takahashi T. (2015). Promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger mediates glucocorticoid-induced cell cycle arrest in the chondroprogenitor cell line ATDC5. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 417 114–123. 10.1016/j.mce.2015.09.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei H., Sutton A. K., Burnett K. H., Fuller P. M., Olson D. P. (2014). AVP neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus regulate feeding. Mol. Metab. 3 209–215. 10.1016/j.molmet.2013.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry R. J., Resch J. M., Douglass A. M., Madara J. C., Rabin-Court A., Kucukdereli H., et al. (2019). Leptin’s hunger-suppressing effects are mediated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis in rodents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116 13670–13679. 10.1073/pnas.1901795116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaisier C. L., Bennett B. J., He A., Guan B., Lusis A. J., Reue K., et al. (2012). Zbtb16 has a role in brown adipocyte bioenergetics. Nutr. Diabetes 2:e46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezai-Zadeh K., Yu S., Jiang Y., Laque A., Schwartzenburg C., Morrison C. D., et al. (2014). Leptin receptor neurons in the dorsomedial hypothalamus are key regulators of energy expenditure and body weight, but not food intake. Mol. Metab. 3 681–693. 10.1016/j.molmet.2014.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter S., Bugarith K., Dinh T. T. (2001). Immunotoxic destruction of distinct catecholamine subgroups produces selective impairment of glucoregulatory responses and neuronal activation. J. Comp. Neurol. 432 197–216. 10.1002/cne.1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roh E., Song D. K., Kim M. S. (2016). Emerging role of the brain in the homeostatic regulation of energy and glucose metabolism. Exp. Mol. Med. 48:e216. 10.1038/emm.2016.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum M., Leibel R. L. (2014). “Adaptive responses to weight loss,” in Treatment of the Obese Patient, 2nd Edn, eds Kushner R. F., Bessesen D. H. (New York, NY: Springer; ), 97–111. 10.1007/978-1-4939-2311-3_7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saito M., Bray G. A. (1984). Adrenalectomy and food restriction in the genetically obese (ob/ob) mouse. Am. J. Physiol. 246 R20–R25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage A. K., Constantinides M. G., Han J., Picard D., Martin E., Li B., et al. (2008). The transcription factor PLZF directs the effector program of the NKT cell lineage. Immunity 29 391–403. 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.07.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon M. B., Loftspring M., de Kloet A. D., Ghosal S., Jankord R., Flak J. N., et al. (2015). Neuroendocrine function after hypothalamic depletion of glucocorticoid receptors in male and female mice. Endocrinology 156 2843–2853. 10.1210/en.2015-1276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton A. K., Pei H., Burnett K. H., Myers M. G., Jr., Rhodes C. J., Olson D. P. (2014). Control of food intake and energy expenditure by Nos1 neurons of the paraventricular hypothalamus. J. Neurosci. 34 15306–15318. 10.1523/jneurosci.0226-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson L. W., Sawchenko P. E. (1980). Paraventricular nucleus: a site for the integration of neuroendocrine and autonomic mechanisms. Neuroendocrinology 31 410–417. 10.1159/000123111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uldry M., Yang W., St-Pierre J., Lin J., Seale P., Spiegelman B. M. (2006). Complementary action of the PGC-1 coactivators in mitochondrial biogenesis and brown fat differentiation. Cell Metab. 3 333–341. 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Pol A. N., Yao Y., Fu L. Y., Foo K., Huang H., Coppari R., et al. (2009). Neuromedin B and gastrin-releasing peptide excite arcuate nucleus neuropeptide Y neurons in a novel transgenic mouse expressing strong Renilla green fluorescent protein in NPY neurons. J. Neurosci. 29 4622–4639. 10.1523/jneurosci.3249-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veyrat-Durebex C., Deblon N., Caillon A., Andrew R., Altirriba J., Odermatt A., et al. (2012). Central glucocorticoid administration promotes weight gain and increased 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 expression in white adipose tissue. PLoS One 7:e34002. 10.1371/journal.pone.0034002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkerson J. E., Raven P. B., Bolduan N. W., Horvath S. M. (1974). Adaptations in man’s adrenal function in response to acute cold stress. J. Appl. Physiol. 36 183–189. 10.1152/jappl.1974.36.2.183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi C. X., Foppen E., Abplanalp W., Gao Y., Alkemade A., la Fleur S. E., et al. (2012). Glucocorticoid signaling in the arcuate nucleus modulates hepatic insulin sensitivity. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 61 339–345. 10.2337/db11-1239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi S. J., Baram T. Z. (1994). Corticotropin-releasing hormone mediates the response to cold stress in the neonatal rat without compensatory enhancement of the peptide’s gene expression. Endocrinology 135 2364–2368. 10.1210/endo.135.6.7988418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S., Cheng H., François M., Qualls-Creekmore E., Huesing C., He Y., et al. (2018). Preoptic leptin signaling modulates energy balance independent of body temperature regulation. eLife 7:e33505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yukimura Y., Bray G. A. (1978). Effects of adrenalectomy on body weight and the size and number of fat cells in the Zucker (fatty) rat. Endocr. Res. Commun. 5 189–198. 10.1080/07435807809083752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakrzewska K. E., Cusin I., Stricker-Krongrad A., Boss O., Ricquier D., Jeanrenaud B., et al. (1999). Induction of obesity and hyperleptinemia by central glucocorticoid infusion in the rat. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 48 365–370. 10.2337/diabetes.48.2.365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Zbtb16 knockdown validation by AAV-mediated expression of Zbtb16 siRNA. (A) In cultured brown adipocytes, Zbtb16 expression was highly induced by Dex treatment. Cells were serum-starved for 8 h and Dex was treated for 5 h (3 h into starvation). n = 4 for each condition (one-way ANOVA). (B) Dex (10 μM)-mediated Zbtb16 induction in cultured brown adipocytes was significantly attenuated by AAV-mediated expression of Zbtb16 siRNA. Scrambled siRNA was transduced at 105 MOI, Zbtb16 siRNA-Lo at 104 MOI, and Zbtb16 siRNA-Hi at 105 MOI (n = 2 for each condition; one-way ANOVA). Data are represented by mean ± SEM, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Zbtb16 knockdown in the PVH. (A,B) Zbtb16PVH KD affected neither energy expenditure nor food intake at baseline (scrambled siRNA, n = 4; Zbtb16 siRNA, n = 6; repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni pairwise comparisons). (C) Zbtb16PVH KD did not affect hypometabolic response during fasting (scrambled siRNA, n = 4; Zbtb16 siRNA, n = 6; independent t-test). Data are represented by mean ± SEM.

Zbtb16 knockdown in the ARC. (A,B) Zbtb16ARC KD affected neither cold-adaptive thermogenesis nor fasting-induced hypometabolism (scrambled siRNA, n = 4; Zbtb16 siRNA, n = 7; independent t-test). (C) Zbtb16ARC KD did not affect glucose tolerance (scrambled siRNA, n = 4; Zbtb16 siRNA, n = 7; repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni pairwise comparisons). Data are represented by mean ± SEM.

Chemogenetic Stimulation of Zbtb16 neurons. (A) Representative histological images showing the expression of cFos (neuronal activation) and mCherry (virus) in the PVH in Zbtb16PVH Control and DREADD-Gq mice. The brains were harvested 1 h after CNO injection at 1.0 mg/kg, IP. (B) Representative histological image showing the expression of cFos and mCherry in the ARC in Zbtb16PVH DREADD-Gq mice. The brains were harvested 1 h after CNO injection at 1.0 mg/kg, IP.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.