Abstract

Today’s LGBTQ youth come of age at a time of dynamic social and political change with regard to LGBTQ rights and visibility, yet remain vulnerable to compromised mental health. Despite advances in individual-level treatment strategies, school-based programs, and state-level policies that address LGBTQ mental health, there remains a critical gap in large-scale evidence-based prevention and intervention programs designed to support the positive development and mental health of LGBTQ youth. To spur advances in research and translation, I pose six considerations for future scholarship and practice. I begin by framing LGBTQ (mental) health disparities in a life course perspective and discuss how research focused on the timing of events could offer insight into the optimum targets and timing of prevention and intervention strategies. Next, I argue the importance of expanding notions of “mental health” to include perspectives of wellbeing, positive youth development, and resilience. I then consider how research might attend to the complexity of LGBTQ youths’ lived experience within and across the various contexts they traverse in their day-to-day lives. Similarly, I discuss the importance of exploring heterogeneity in LGBTQ youth experiences and mental health. I also offer suggestions for how community partnerships may be a key resource for developing and evaluating evidence-informed programs and tools designed to foster the positive development and mental health of LGBTQ youth. Finally, I acknowledge the potentials of team science for advancing research and practice for LGBTQ youth health and wellbeing. Throughout, these future directions center the urgent needs of LGBTQ youth.

Research has established intractable and persistent disparities in mental health, substance use, and other indicators of wellness among lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning (LGBTQ)2 youth relative to their heterosexual and cisgender peers (Russell & Fish, 2016; Mereish, 2019). LGBTQ-related health inequities are linked to minority stressors (Meyer, 2003): Experiences of anti-LGBT stigma and discrimination elevate distress and limit effective coping strategies that interfere with positive development, health, and wellbeing (Goldbach & Gibbs, 2017; Russell & Fish, 2016). These stressors include policies and laws that limit the rights and protections of LGBTQ people (Hatzenbuehler, 2017), interpersonal experiences of rejection or harassment (Katz-Wise & Hyde, 2012; Toomey & Russell, 2016), and internalized feelings of self-directed stigma, such as internalized homophobia and transphobia (Puckett & Levitt, 2015).

At the same time, few societal attitudes and opinions have changed as quickly as those regarding sexual – and to a lesser extent, gender – minority people and rights. Large-scale social surveys indicate that attitudes towards LGB people and their relationships have steadily improved in the last 50 years (McCarthy, 2019). We have also witnessed the repeal of harmful policies (e.g., “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell”) and the enactment of laws that provide protections for LGBTQ people and their families (e.g., marriage equality). The visibility of LGBTQ people in mainstream culture, media, and politics also provides evidence of how much things have changed with regards to LGBTQ people and communities (GLAAD, 2020).

Given the link between stigma and health, many presumed that previously documented mental health vulnerabilities would dissolve for more recent cohorts of LGBTQ young people (McCormack, 2012)—that new legal and social acceptance might present new pathways towards health and wellness for today’s LGBTQ young people. However, emerging studies show that this hope is unmaterialized: With each new wave of data, LGBTQ youth continue to show elevated rates of mental distress, symptomology, and substance use relative to their heterosexual and cisgender peers (Johns et al., 2018, 2019).

These latest findings append a forceful body of science on LGBTQ mental health inequities and beg for practical strategies to address the positive development, mental health, and wellness of LGBTQ youth. In this article I argue that scholarship on LGBTQ youth mental health has reached a critical turning point for action. Framed in the context of translational research, I propose six distinct but interrelated considerations to advance future research and (ultimately) programs to address LGBTQ youth mental health: (1) framing LGBTQ health disparities in a life course perspective; (2) expanding notions of mental health; (3) attending to the complexity of youth contexts; (4) acknowledging heterogeneity, (5) leveraging community resources, and (6) fostering team science approaches for inquiry and application.

Why LGBTQ Youth Mental Health Remains Urgent

There has been remarkable progress in the lives and rights of LGBTQ people. In the context of growing acceptance and visibility, LGBTQ young people have the ability to understand their identities at younger ages and “come out” in the context of their families, schools, and communities. Indeed, research documents the declining age of coming out for sexual minority people across generations (Bishop, Fish, Hammack, & Russell, in press; Martos et al., 2017; Russell & Fish, 2016). The timing between initial awareness and disclosing one’s sexual minority identity occurs a decade earlier than sexual minorities who came of age in the 1970s (Bishop et al., in press). However, the declining age of coming out now overlaps with adolescence; a unique developmental period characterized by heightened conformity, self-consciousness, and social regulation, particularly around sexuality and gender (Brechwald & Prinstein, 2011; Pascoe, 2007; Payne & Smith, 2011). Despite the benefits of understanding, labeling, and disclosing an LGBTQ identity during a more developmentally appropriate stage of the life course (i.e., adolescence), these experiences now occur when youth are particularly vulnerable to peer attitudes, influence, and victimization (Robinson, Espelage, & Rivers, 2013; Russell & Fish, 2019).

Peers and peer approval matter so much to the self-esteem, wellbeing, and self-concept of young adolescence (Brechwald & Prinstein, 2011), and rates of peer victimization are highest during this point in the life course given that youth are still actively developing empathy and ethical/moral reasoning (Horn, 2006; Robinson et al., 2013). Adolescence is also a critical period for the onset and progression of mental health symptomology and substance use behaviors, the patterns of which set the stage for health and wellbeing across the life course (Kessler et al., 2012; Kim-Cohen et al., 2003). Adolescents are also required to attend school and are financially dependent on family, which eliminates opportunities to exit unsafe environments. Therefore, with improved social attitudes and increased visibility, sexual minority youth feel empowered to come out but are then uniquely vulnerable to peers and family who may not accept them (D’Augelli et al., 2008; Russell, Toomey, Ryan, & Diaz, 2014). Thus, the confluence of normative developmental susceptibilities with unique developmental tasks of LGBTQ youth (e.g., “coming out”) creates distinct vulnerabilities for LGBTQ young people today. That is, these broader sociohistorical processes now collide with normative developmental process in ways that make sexual minority and (arguably) gender minority youth susceptible to similar mental health concerns of the generations of LGBTQ people who came before them (see Russell & Fish, 2016, 2019).

In support of these ideas, several studies now document persistent trends in sexual orientation differences in mental health (Liu et al., 2020; Peter et al., 2017; Raifman et al., 2017), substance use (Fish, Watson, Porta, Russell, & Saewyc, 2017; Fish, Turner, Phillips, & Russell, 2019; Fish & Baams, 2018), and the factors implicated in sexual minority health inequities (e.g., victimizations, family support; Poteat, Birkett, Turner, Wang, & Phillips, 2019; Watson, Rose, Doull, Adjei, & Saewyc, 2019). At the same time, research on the developmental timing of sexual orientation and gender identity-related disparities in substance use (Fish & Russell, 2019a), mental health (Fish & Russell, 2019b; la Roi et al., 2016), and peer victimization (Fish & Russell, 2019b; Martin‐Storey & Fish, 2019; Mittleman, 2019) demonstrate that these disparities emerge at early ages. For example, data from the California Healthy Kids Survey document that sexual orientation and gender identity differences in mental health are present by age 10 (Fish & Russell, 2019b), and substance use disparities by age 12 (Fish & Russell, 2019b). Prospective panel data also show how youth who later report same-sex attraction or sexual minority identities indicate elevated rates of peer victimization relative to heterosexual peers starting at age nine and persisting through age 15 (Martin‐Storey & Fish, 2019; Mittleman, 2019). Taken together, findings underscore the persistence of LGBTQ-related disparities over time and their early emergence in the life course.

It is essential to pause and recognize that research on gender identity differences in sociohistorical and developmental trends are noticeably absent from the literature (cf., Fish & Russell, 2019a, 2019b). Research on the developmental perspectives of stress and mental health have centered the experiences of sexual minority youth; there are likely similar but also important distinctions in the developmental experiences of transgender youth that uniquely shapes their lived experience and mental health (Fish, Baams, & McGuire, 2020; Spivey & Edwards-Leeper, 2019). The exclusion of gender identity measures in youth data creates missed opportunities; particularly in large-scale longitudinal datasets. Although the number of data sources including measures of gender identity are growing (e.g., 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey; Adolescent Cognitive Brain Development Study; Calzo & Blashill, 2018), their omission continues to hamper research, particularly in clinical studies (Cahill & Makadon, 2017; Pachankis & Safren, 2019).—This is an area in desperate need of future research and could be invigorated through public and private funding entities requiring the collection of sexual orientation and gender identity data and the inclusion of gender identity measures in future cycles and waves of ongoing panel studies (e.g., Monitoring the Future, Fragile Families; see LGBTdata.com for data sources that include sexual orientation and gender identity measures).

Current Strategies for Supporting LGBTQ Youth Mental Health

Given the vulnerabilities of LGBTQ youth and the implications for health across the life course, adolescence reflects a critical period for prevention and intervention strategies. Yet, outside of sexual health (e.g., HIV/STI risk; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020), there remains limited research that systematically develops and tests LGBTQ-related or LGBTQ-specific youth mental health promotion strategies across contexts. I do, however, want to recognize the three main areas in which evidence-based strategies have been identified: individual-level treatment, school policies and programs, and state-level policies.

Individual-Level Treatment

Although the LGBTQ identities and issues have made their way into the ethical guidelines and standards of care for most mental health organizations (e.g., American Psychological Association, America Counseling Association, American Association of Marriage and Family Therapy) innovation in clinical interventions for LGBTQ young people remains nascent (Pachankis & Safren, 2019; Russell & Fish, 2016). Recent advancements in clinical strategies include Attachment-Based Family Therapy (ABFT; Diamond, Russon, & Leven, 2016), Relational-Focused Therapy (RFT-LGBTQ; Diamond, Boruchovitz-Zamir, Gay, Nir-Gottlieb, 2019), and ESTEEM (Pachankis, Hatzenbuehler, Rendina, Safren, & Parsons, 2015). These models of treatment offer preliminary efficacy for improving LGBTQ youth mental health but are still in the process of broader implementation and testing. These clinical approaches represent an essential step in developing and altering evidence-based treatment strategies (e.g., cognitive-behavioral therapy, attachment-based family therapy), but the limitations of individual treatment cannot be ignored (Kazdin, 2017). Of course, individual-level treatment is a necessary approach to bolstering mental health for LGBTQ youth. However, many who need mental health treatment never receive it: Less than half of adolescence with depression and only 1 in 8 people over the age 12 who need substance use treatment receive it (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2018). Therefore, along with developing empirically supported therapeutic strategies to support LGBTQ youth, there needs to be an effort to diversify delivery models of LGBTQ-sensitive mental health care to broader swaths of the population (Kazdin, 2017, 2019).

School Policies and Programs

Schools are perhaps the single most studied context for LGBTQ youth. Gay-straight alliance programs, more recently referred to gender and sexuality alliances (GSAs), are school-based extracurricular clubs that convene LGBTQ youth and allies. Supported by an adult advisor, GSAs act as a resource for support and socialization (Poteat, Yoshikawa, Calzo, Russell, & Horn, 2017). The presence of GSAs is associated with less school-based victimization for LGBTQ youth (Marx & Kettrey, 2016) and prospectively linked to reduced depression and anxiety for youth who participate in these programs (Poteat et al., in press). LGBTQ-inclusive school policies are also associated with student perceptions of school climate, experiences of victimization, and LGBTQ youth mental health (Day, Fish, Grossman, & Russell, 2020; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2014, 2015; Hatzenbuehler & Keyes, 2013; Kull et al., 2016). Research suggests that programs (e.g., GSAs) and policies (e.g., enumerated anti-bullying policies) represent distinct pathways to improving support for LGBTQ youth in schools—GSAs appear to influence LGBTQ youths’ perceptions of peer support, whereas policies are more strongly associated with perceptions of teacher support (Day et al., 2020). This suggests that policies and programs represent distinct and mutually beneficial strategies to help bolster a safe and supportive environment for LGBTQ youth.

State-Level Policies

Finally, state-level policy reflects large-scale health promotion strategies for LGBTQ youth. The field of structural stigma (see Hatzenbuehler, 2016, 2017) has provided compelling evidence that state social and policy environments shape the mental health of LGBTQ youth. Sexual minority youth who live in states and cities with more protective policies are less likely to experience victimization (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2015), substance use (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2014), and suicidal ideation (Hatzenbuehler, 2011; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2014; Hatzenbuehler & Keyes, 2013). Research also shows that sexual minority young adults who grew up in more stigma-laden contexts display blunted physiological response to stress than sexual minority youth who grew up in more affirming contexts (Hatzenbuehler & McLaughlin, 2014). Less robust, but emerging, are studies that highlight that structural stigma operates similarly for transgender populations (Goldenberg, Reisner, Harper, Gamarel, & Stephenson, 2020; Perez-Brumer, Hatzenbuehler, Oldenburg, & Bockting, 2015), which remains an important area for future research (Hatzenbuehler, 2017).

These strivings in individual, school, and policy-level interventions remain critical components for addressing the mental health of LGBTQ youth and deserve continued attention. Equally necessary and urgent, however, is the need to address the negative space in this body of science: The overwhelming dearth of research surrounding large-scale prevention, intervention, and health promotion programs that specifically address the mental health of LGBTQ youth. Despite initial progress (see Affirmative Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; Austin, Craig, & D’Souza, 2018; Craig, Austin, & Alessi, 2019), a recent review of LGBTQ youth interventions for mental health, substance use, and violence identified only nine evidence-supported interventions for SGM youth mental health, with the majority of reflecting individual-level psychological and pharmacological/medical treatment or policy (Coulter et al., 2019).

Future Directions: Considerations for Knowledge to Action

With the increased inclusion of sexual orientation and gender identity measures in population-based studies and the rise in federally funded studies that focus on the mental health of LGBTQ people (National Institute of Health, 2017), we now have a compelling and rapidly expanding body of science on the mental health of LGBTQ youth. In the last decade, in particular, studies have identified and examined a multitude of contributing factors and processes complicit in undermining the mental health of LGBTQ youth (Goldbach & Gibbs, 2017; Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Hatzenbuehler & Pachankis, 2016). This research guides modifiable factors that can and should be addressed to improve LGBTQ population health. For this reason, I situate my recommendations for future scholarship and practice in the context of translational research.

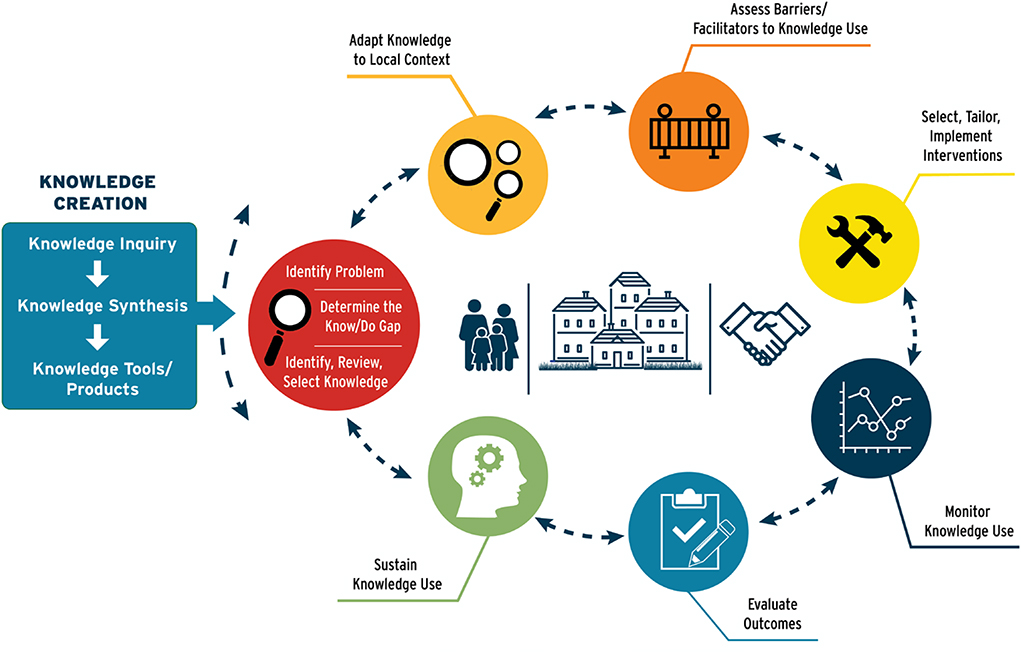

Translational science investigates how basic science is transformed into interventions that improve the health of people and populations (Austin, 2018). In the context of health disparities, translation follows a simple sequence: (1) detect disparities, (2) identify their causes, (3) develop interventions, and (4) implement, evaluate, and monitor outcomes related to the identified health disparities (Fleming et al., 2008). There are many translational research models, and the field of translational science, including dissemination and implementation, has grown exponentially in recent decades (Brownson, Colditz, & Proctor, 2018). One of the more widely used models, the Knowledge to Action Framework (Graham et al., 2006, 2018), consists of two distinct but interrelated and mutually informative feedback loops – knowledge creation and the action cycle (see Figure 1). I argue that scholarship on LGBTQ mental health research has primarily remained in the knowledge creation phase, with few venturing into the action cycle. Yet, translation of evidence into practice reflects a necessary next step in addressing mental health among LGBTQ youth on a broad scale.

Figure 1.

The Knowledge to Action Framework. Updated from Graham et al (2006)

My goal in this article is not to comprehensively review or traverse the Knowledge to Action Framework, but to instead raise six considerations that I believe will help to advance research and translation efforts that address LGBTQ youth mental health: (1) framing LGBTQ health disparities in a life course perspective; (2) expanding notions of mental health; (3) attending to the complexity of youth contexts; (4) acknowledging heterogeneity, (5) leveraging community resources, and (6) fostering team science approaches to inquiry and application.

Framing LGBTQ Health in a Life Course Perspective

Although not necessarily a new concept (Hammack, 2005; Hatzenbuehler, 2017), the application of life course theory to LGBTQ health remains novel. Adolescence is a critical developmental period for mental health symptomology and substance use onset, which have implications for mental health across the life course (Schulenberg, Maslowsky, & Jager, 2018; Schulenberg, Sameroff, & Cicchetti, 2004). Yet, studies exploring how the developmental timing, sequencing, and constancy of specific experiences (e.g., “coming out”, victimization, hormone therapy) shape LGBTQ lives and its association with (mental) health are limited.

Life course tenets require that scholars and practitioners consider both human developmental (ontogenetic) and sociohistorical (sociogenic) time: Two interrelated constructs that provide unique vantage points for understanding the mental health of not only LGBTQ youth, but the population more broadly (Hatzenbuehler, 2017). Although limited by a lack of longitudinal data, there is dire need to understand how experiences earlier in the life course contribute to later health and wellness among LGBTQ people. With rare exceptions (Coulter, Jun, et al., 2019; Pachankis, Hatzenbuehler, & Stark, 2014), these investigations are absent from the literature. It would be easy to call for more longitudinal studies; however, it is most important to consider the actual design of longitudinal studies so that they can identify modifiable mechanisms and critical periods for prevention and intervention. Research that seeks to identify (1) the degree to which earlier experiences shape mental health, (2) the differential impacts of these experiences, and (3) how the timing of these experiences shape mental health across the life course would significantly advance policies, programs, and prevention strategies aimed at address the mental health of LGBTQ people, but also the optimal time for implementing them.

Recent studies find that sexual orientation and gender identity-related mental health, substance use, and victimization disparities are already present in late childhood and early adolescence (ages 10 and 12, respectively; Fish & Russell, 2019a, 2019b; la Roi et al., 2016; Martin‐Storey & Fish, 2019; Mittleman, 2019), which suggests that current strategies to support LGBTQ youth (e.g., GSAs) are available after disparities have emerged. From a prevention standpoint, these findings imply that experiences in childhood are shaping LGBTQ-related disparities, and thus require creative strategies to assess how early interactions may be disproportionately represented or uniquely impactful for children who later understand themselves to be LGBTQ. Although there is much work to be done in this area, it would behoove researchers, practitioners, policy makers, and educators to consider how to capture and integrate issues of LGBTQ inclusivity at younger ages. Clark (2016), for example, found that including LGB-inclusive curriculum in elementary school classrooms improved children’s knowledge of same-sex relationships relative to children in a control conditions. Age-appropriate interventions that incorporate issues of diversity and gender expression could help to reduce bias in children and ultimately stave early exposures to stigma for LGBTQ youth.

Expanding Notions of Mental Health

It is undeniable that LGBTQ youth experience stark inequalities in major markers of mental health (Marshal et al., 2011; Perez-Brumer, Day, Russell, & Hatzenbuehler, 2017; Russell & Fish, 2016). Nevertheless, mental health is not specific to mental health conditions, and there is growing interest in the broader construct of “emotional wellbeing.” Emotional wellbeing reflects concepts of social and community connection, life satisfaction, positive affect, and finding meaning and purpose in life – factors that are readily influenced by stigma, discrimination, and marginalization (Feller et al., 2018). Importantly, emotional wellbeing is a population health issue and a robust predictor of health morbidity and all-cause mortality (Feller et al., 2018). The National Institutes of Health has several current calls for funding to assess and address emotional wellbeing and its components (e.g., isolation and social connectedness; see PAR-19–373 and RFA-AT-20–003). Rightfully, specific mental health conditions (e.g., depressive symptomology, suicidal ideation) are necessary targets of LGBTQ health initiatives. Still, research focused on the broader construct of wellbeing could offer unique prevention and health promotion strategies for LGBTQ youth.

Concepts of emotional wellbeing dovetail nicely with models of positive youth development (PYD; Benson, Leffert, Scales, & Blyth, 1998; Silbereisen & Lerner, 2007), which guide many of the nation’s youth policy and programming initiatives (Benson, Scales, & Syversten, 2011; Catalano, Berglund, Ryan, Lonczak, & Hawkins, 2004; Roth & Brooks-Gunn, 2016). Rooted in prevention (Catalano et al., 2004), PYD reflects an approach to youth engagement that seeks to leverage youths’ inherent strengths to promote positive functioning in the contexts in which youth develop – family, school, and community (Silbereisen & Lerner, 2007). PYD programs promote social connection, socioemotional competence, self-determination, self-efficacy, future orientation, and prosocial behavior, among other prosocial outcomes (Catalano et al., 2004). Although PYD is widely recognized, its application to LGBTQ youth has been slow (cf., Toomey, Syversten, & Flores, 2019). Preliminary work in this area has focused on the Developmental Assets Framework, which asserts 40 positive resources and strengths that youth need to thrive. Initial findings suggest that assets appear to operate similarly for heterosexual, cisgender, and LGBTQ youth in both their form and protective function (Syvertsen, Scales, & Toomey, 2019; Toomey et al., 2019). Not surprisingly, however, is that LGBTQ youth experience deficits in many internal (e.g., academic engagement, social competence) and external (e.g., support, belonging) developmental assets which likely leave them vulnerable to lower wellbeing, poor mental health, and substance use. There are many avenues to explore how PYD operates for LGBTQ youth, and these initial applications are promising: Many youth programs adhere to PYD models (e.g., 4-H, scouting). Therefore, minimal adaptation to existing programs could help make them more welcoming for LGBTQ youth and position them to better address the experiences of LGBTQ youth. Even outside of PYD programs, understanding how existing evidence-based youth programs could be adapted to accommodate LGBTQ youth reflect one major strategy to address the current dearth in LGBTQ youth prevention and intervention tools.

Finally, the LGBTQ youth mental health literature is lacking studies that assess resilience (Meyer, 2015). It is worth noting and emphasizing that LGBTQ youth demonstrate enormous strength in the face of adversity. This adversity, however, takes a toll on youth as they perpetually navigate environments that are stigmatizing and hostile towards their sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression. Studies have been slow to adopt strengths-based perspectives and to examine how youth foster and display resilience; the result of which could help develop strategies that support youths existing strengths in addition to cultivating internal and external resources to cope with sexual minority stressors and stigma. Much of the current research provide implications for how to mitigate stigma and harms directed towards LGBTQ youth (e.g., strategies to reduce bullying, victimization, and stigma), equally important but less often studied are identifying addressable intra- and interpersonal strategies that attenuate the negative impacts of stigma on LGBTQ youth mental health (e.g., coping strategies, empowerment; Craig, Austin, Alessi, McInroy, & Keane, 2017; Toomey, Ryan, Diaz, & Russell, 2018; Wagaman, 2016). Some emerging research suggests that LGBTQ-specific coping strategies and engagement in social justice activism is positive and protective for LGBTQ youth (Poteat et al., in press; Toomey et al., 2018; Wagaman, 2016). Research focused on identifying coping and resilience strategies will be instrumental to informing large-scale prevention and intervention programs designed to help LGBTQ youth combat the negative impact of stigma and discrimination (see Craig, Austin, Alessi, McInroy & Keane, 2017; Matsuno & Israel, 2018; Zeeman, Aranda, Sherriff, & Cocking, 2017).

LGBTQ Youth Experiences Are Multicontextual and Multifaceted

Among studies that assess the factors influencing LGBTQ youth mental health, the majority focus on experience within a single context: schools, families, peers, or communities. This focus has been, of course, necessary to better understand how stigma and support are associated with LGBTQ youths’ mental health. However, youth experience is multicontextual and multifaceted. For example, different contexts may be more or less accepting of youths’ LGBTQ identity. Therefore, on any given day, LGBTQ youth may transition from affirming home environments to hostile school environments, or vice versa. Youth may also work to manage their LGBTQ identities across contexts, choosing to be “out” in one context, but not another, or even out to one parent, but not the other. Research suggests that youth who are “out” at school and with family are more vulnerable to victimization (D’Augelli et al., 2008; Russell et al., 2014, Riggle, Rostosky, Black, & Rosenkrantz, 2017), but that concealment also has negative consequences for health (Pachankis, Mahon, Jackson, Fetzner, & Bränström, 2020, Riggle et al., 2017). More generally, identity management strategies – being out in some contexts but not all – have been shown to elevate distress and poor mental health among LGBTQ adults (Riggle et al., 2017), and impact academic achievement for youth (Watson, Wheldon, & Russell, 2015). Even with this knowledge, researchers have yet to comprehensively interrogate how navigating these various contexts impact LGBTQ youth mental health during adolescence and how these earlier experiences may shape perceptions of stigma, rejection sensitivity (see Feinstein, 2019), and mental health across the life course.

Even within a given context, LGBTQ youth experiences are multifaceted: school can include both supportive and unsupportive spaces, and families can simultaneously engage in accepting and rejecting behaviors. Nevertheless, researchers often characterize these contexts as either accepting or rejecting. There have been several recent studies that showcase that LGBTQ youth report the co-occurrence of accepting and rejecting experiences with family and that these constructs are uncorrelated with one another (Pollitt, Fish, & Watson, 2019; McGuire & Fish, 2018). More recent work finds that transgender people who experience simultaneous messages of support and rejection from family have poorer mental health than transgender people who experience either overwhelming support or outright rejection (Allen, 2020). Research that is intentional about operationalizing and measuring experiences both across and within various contexts will help to bring much-needed nuance to how LGBTQ youth experiences with school, peers, and families shape mental health and wellbeing and, more importantly, strategies to intervene in these spaces.

Future research should seek to assess how these multilevel and multicontextual influences work in tandem to influence LGBTQ youth’s mental health and related resources, given the reality that the strategies needed to eliminate LGBTQ mental health disparities must address each of the multiple contexts that LGBTQ youth traverse. There has been some work in this area, largely focused on how multiple sources of support may differentially explain mental health and wellbeing among LGBTQ youth (McConnell, Birkett, & Mustanski, 2015; Snapp, Watson, Russell, Diaz, & Ryan, 2015) and the degree to which parental support buffers the link between school victimization and poor mental health (Eisenberg & Resnick, 2006; Poteat, Mereish, DiGiovanni, & Koenig, 2011). More challenging, but perhaps more illuminating, would be investigations of how family, school, and community contexts intersect: For example, how parents shape school experiences for LGBTQ youth through advocacy, or whether and how schools can educate parents about better supporting their LGBTQ youth. Investigating the nexus of these environments will allow researchers and practitioners to better address how the environmental profiles of youth help to shape their positive development and mental health and the developmental of multisectorial strategies to support LGBTQ youth mental health.

Heterogeneity and Mental Health among LGBTQ Youth

Despite shared narratives among LGBTQ youth, these experiences do not occur independent of other social identities and contexts (e.g., minoritized racial or ethnic identities, sex/gender, disability status, religion, immigrant status, documentation status, and socioeconomic status). Intersectional perspectives of LGBTQ youth mental health and wellbeing are still woefully underrepresented in the mainstream scholarship (Santos & Toomey, 2018; Toomey, Huynh, Jones, Lee, Revels-Macalinao, 2017), yet have genuine implications for understanding and improving the lived experience and mental health of LGBTQ youth.

Although many studies acknowledge that experiences are likely unique for LGBTQ youth of color, there remains limited research that actually takes this on (c.f., Anhalt, Russell, & Shramko, 2020; Toomey, Shramko, Flores, & Anhalt, 2018). In their content analysis and critical review, Toomey et al. (2017) noted that studies are largely “focused on sexual risk, substance use, and mental health problems rather than on normative developmental processes or positive youth development” (pp. 18). Similarly, few studies in their review examined the process by which interlocking experiences of oppression related to both sexual orientation and race/ethnicity impacted sexual minority youths’ mental health. Although descriptive work is a necessary avenue to highlight differential risk, a focus on normative development and resilience processes are essential to understand the lived experience of LGBTQ youth of color, and (importantly) the development of multi-level strategies to support them. In one study focused on processes that influence mental health, Poteat and colleagues (2011) assessed whether parental support buffered the association between homophobic victimization and mental health, and found that the moderating effect was only present among LGBTQ youth of color—an effect that authors hypothesized was likely related to youths’ ability to adapt racial/ethnic socialization messages (see Hughes, Rodriguez, Smith, Johnson, Stevenson, & Spicer, 2006) and copings strategies to experiences of homophobic bullying. This examples helps illustrate the research and applied benefits of not only acknowledging racial/ethnic (and other social identity) differences in rates of poor mental health and resilience strategies, but the processes through which they occur. Despite some advancements in this area of research (Anhalt et al., 2020; Toomey, Shramko et al., 2018; Pollitt, Mallory, & Fish, 2018; Poteat et al., 2011), we need more concentrated efforts to assess these experiences in a way that acknowledges different potentials for development (Coll et al., 1996) among LGBTQ youth of color (and the vast cultural, ethnic, and experiential differences within the “LGBTQ youth of color” moniker, which deserve explicit attention).

Intersectional perspectives of youth development also encourage the exploration of other social identities and experiences that shape mental health and wellbeing. For example, there has been growing attention to the experiences of rural and southern LGBTQ youth, and how their community contexts shape their experiences, but also their access to critical resources and strategies of resilience linked to social justice (Gandy-Guedes & Paceley, 2019; Paceley, Sattler, Goffnett, & Jen, 2020). There is also growing recognition of the experiences of disabled and neurodiverse/autistic LGBTQ people3 (Strang et al., 2020; ; Kittari, Walls, & Speer, 2017), LGBTQ youth living in situations of economic and housing instability (Frost, Fine, Torre, & Cabana, 2019; Choi, Wilson, Shelton, & Gates, 2015), and LGBTQ youth who are or have been involved in systems of care and custody (e.g., foster care, juvenile punishment; Wilson & Kastanis, 2015; Wilson, Jordan, Meyer, Flores, Stemple & Herman, 2017). The list goes on, and also requires explicit attention to distinctness and overlapping experiences related to sexual orientation, gender identity, and expression. As a quantitative population health researcher myself, it is easy to fall into the trap of oversimplifying the experiences of LGBTQ youth and defaulting to reductionist perspectives when attempting to understand and communicate their experiences. Researchers (myself included) must be more aware of and acknowledge these diversities moving forward, as they have indisputable implications for how we address LGBTQ rights and mental health.

Community Context and Resources

Relative to schools and even family, there has been less research attention on the community factors that might thwart or promote health for LGBTQ youth (cf., Paceley, 2016; Paceley, Fish, Conrad & Schuetz, 2019; Watson, Park, Taylor, Fish, Corliss, Eisenberg, & Saewyc, 2020). Yet, community-level factors are implicated in LGBTQ mental health. For example, sexual minority youth who live in counties with greater representation of same-sex couples, registered democrats, GSAs, and non-discriminatory school policies are less likely to engage in suicidal behavior than sexual minority youth living in counties that lacked these characteristics (Hatzenbuehler, 2011). A more recent study showed that LGBTQ-specific support factors at the community level (i.e., LGBTQ community resources, number of LGBTQ-youth serving community centers, years of GSA presence in schools) were associated with lower substance use among sexual minority youth. The process by which these community factors support LGBTQ youth, however, is largely unknown. Is it that youth are living in policy environments that reflect more accepting communities? Or is wellbeing heighted through tangible resources (e.g., LGBTQ youth centers), events (e.g., Pride), and LGBTQ visibility (e.g. pride flags in businesses)? Notwithstanding the impacts of state-level policies on LGBTQ mental health (Hatzenbuehler, 2017), future research might want to consider how policies are enacted and reflected in community environments given that these more proximal factors likely mediate the impacts of policy on youth mental health. There also remain limited investigations of how these community supports operate for transgender youth (Hatzenbuehler, 2017). Understanding not just what, but how, community supports influence and shape LGBTQ youth mental health would assist with future implementation of these strategies. From a translational research perspective, knowledge about how community differences impact LGBTQ youth are critical for developing, adapting, and implementing programs designed to address LGBTQ mental health and wellbeing.

One area of future advancement lies in partnership with LGBTQ community centers. LGBTQ youth centers have been long-standing institutions in major cities, and their presence is growing in communities all over the country (Allen, Hammack, & Himes, 2012; CenterLink & Movement Advancement Project, 2018; Williams, Levine, & Fish, 2019). Preliminary research suggests that LGBTQ youth who attend these organizations report better self-esteem and lower substance use when compared to LGBTQ youth who do not engage with centers (Fish et al., 2019). These programs offer a safe space for LGBTQ youth to meet one another, seek social support, foster community, and engage in mental and medical health care services specifically designed to address the unique needs of LGBTQ young people. Importantly, the emerging literature in this area finds that youth of color, transgender youth, and youth who experience economic precarity are more likely to engage in LGBTQ community-based centers (CenterLink & Movement Advancement Project, 2018; Fish et al., 2019; Williams et al., 2019), suggesting their ability to reach youth who are often at the margins of other LGBTQ events and programs. Thus, LGBTQ youth centers may be a unique partner in advancing research and practice around supporting the mental health and positive development of LGBTQ youth.

Nevertheless, LGBTQ youth centers have not received much empirical attention (Allen et al., 2012; Fish et al., 2019). In the process of translating knowledge to action, LGBTQ youth centers may be a missing link given their history of developing, adapting, and delivering LGBTQ-specific, youth-based, community programs (Williams et al., 2019). Scholars interested in developing, implementing, evaluating, and disseminating strategies to support LGBTQ youth should consider authentic community-engaged partnerships with community-based centers and the value of including these experts in the process of translation. In the progression of advancing evidence-based practices for LGBTQ youth mental health, researchers should also recognize the value of practice-based evidence (Ammerman, Smith, & Calancie, 2014) and the institutional knowledge of these organizations in creating relevant, innovative, and effective tools and strategies to support LGBTQ young people.

Fostering Team Science Approaches to Inquiry and Application

Although not entirely intentional, I have had the great fortune of multi- and transdisciplinary training that melds couple and family therapy, human development and family studies, and population and public health. If not already apparent, I believe solutions that promote LGBTQ youth health require assimilated vantage points from human development, family science, education, psychology, public health, social work, public policy, law, and medicine, to name a few. It further necessitates the integration of frameworks, methodologies, data sources, and findings across these disciplines. As such, the degree to which we continue to see fruitful lines of work mature on these important topics, will hinge in large part on our commitment to and providing the next generation of (LGBTQ youth) researchers with training in team science.

Team science broadly reflects collaborative efforts that integrate expertise across different disciplines to address scientific and real-world challenges (Bennett & Gadlin, 2012; Stokols, Hall, Taylor & Moser, 2008). Many of us learn how to do interdisciplinary work “by accident” or through “trial and error.” For LGBTQ youth researchers, many of us were forced to read and integrate cross-disciplinary research and theory by necessity given the relatively few scholars who were doing this work across disciplines even just 10–15 years ago. In many ways, this historical cross-pollination, led to a growing field of study that has remained fairly interdisciplinary and dynamic as it developed knowledge on LGBTQ young people. As scholarship on LGBTQ youth continues to grow, we will – I believe – become more siloed within our respective disciplines. It is inevitable. Science on LGBTQ youth is growing exponentially, and it will soon be impossible for individual researchers to stay up-to-speed on all the relevant science on LGBTQ youth. The interdisciplinary strength that emanates from the roots of our science, however, could live on through training and education that integrates and privileges team science. What if training programs were structured and designed to facilitate training and education among early career researchers through interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary teams, in addition to strategies for developing, implementing, and sustaining these collaborative endeavors? Of course these approaches would benefit emerging scholars, regardless of discipline or focus, but particularly for those whose scholarship seeks to address pressing social problems—including those that complicate health for LGBTQ populations.

As the “science of team science” expands (Stokols et al., 2008), we are learning the ways in which team science can be leveraged to tackle complex social problems and the characteristics that make teams more effective in doing so. More generally, team science approaches to LGBTQ youth positive development and health will be necessary to aid in effective translation of science and to develop prevention and intervention strategies that address the unique contextual factors that support and thwart health for LGBTQ young people—this includes the integration of policy makers and community partners. As we consider the ways we can translate knowledge to action, researchers should evaluate the degree to which their work could be enhanced by multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, and transdisciplinary research teams.

Conclusions

It goes without saying that macro-level policy changes are necessary to improve the lives of LGBTQ youth (see Hatzenbuehler, 2017). In the presence of perpetual hetero- and cisnormativities, policies aid in the protection of LGBTQ people. However, the impact of these policies takes time (Hatzenbuehler, Bränström, & Pachankis, 2018). There remains urgent need to mobilize research for LGBTQ mental health promotion at a broader scale. The need for LGBTQ-specific programs remain a pressing issue given persistent mental health inequities for LGBTQ young people. Despite advances in individual-level treatment strategies, school-based programs, and state-level polices that address LGBTQ mental health, there remains a critical gap in large-scale evidence based prevention and intervention programs designed to support the positive development and mental health of LGBTQ youth. With the intention of stimulating research to cultivate action and progress translation, I offered six distinct but complementary perspectives for future work. Although translation is a necessary step for our field, translational research is a difficult endeavor that will present new and likely frustrating challenges to our science and scholarship. These challenges may be overcome in partnership with LGBTQ youth, community stakeholders, and interdisciplinary scholars. By working through the challenges of developing evidence-informed strategies we will ultimately provide another avenue for improving the positive development and wellbeing of LGBTQ young people.

Funding:

This work was supported by the University of Maryland Prevention Research Center cooperative agreement #U48DP006382 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Center for Child Health and Human Development grant P2CHD041041, Maryland Population Research Center. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or CDC.

Footnotes

1. Page 3, near end of page. Should “previously documenting” be “previously documented”?

Response: This has been addressed.

2. Page 5, near end of page. “susceptible to similar the same” [i.e., pick one]

Response: This has been addressed.

3. Page 6, line 19. The word “victimization,” would it be accurate to add “peer?” and/or “identity-related” to clarify the nature of the victimization?

Response: Thank you for this suggestion, I have changed this to “peer victimization”.

4. Page 6. “It is essential to pause and recognize that gender identity differences in sociohistorical and developmental trends are noticeably absent from the literature (c.f., Fish & Russell, 2019a, 2019b).” Would it be accurate here to insert “research on” in between “that” and “gender”?

Response: Yes, this would be more accurate. Thank you. This has been added.

5. Page 6. “The exclusion of gender identity measures in youth data creates missed opportunities.” Related to Comment #4, it would be useful here to unpack a couple of key observations you have made:

a. First, that much of the work in this area focuses on use of large-scale longitudinal, archival datasets that, by definition, require regular administration of gender identity measures. For much of the 20th century, many of the large-scale datasets available did not include the crucial gender-identity data to address questions germane to inquiries regarding sociohistorical and developmental differences in gender identity.

b. Second, I presume that in many respects, these omissions continue in many of the available, ongoing longitudinal studies focused on youth mental health. If so, it would be useful then to cite some recent work supporting such a statement.

Response: Thank you for this suggestion. I have made these arguments more explicit and have added some citations to support the emergence of data sources that include measures of gender identity, and citations supporting the need for greater inclusion moving forward.

6. Page 7. “—this is an area in desperate need of future research.”

a. I wonder, just a thought: Might this be a good time to mention specific, ongoing longitudinal studies on youth mental health that come to mind, where (a) gender identity data is lacking and thus (b) inclusion in future years would facilitate future research?

b. Alternatively, do any datasets come to mind that have these data? I think addressing either (or both!) would be great for readers of the Future Directions series, many of whom are early career researchers and thus would benefit from knowledge about available datasets.

c. In case it’s helpful, I think Lucina Uddin’s Future Directions paper from 2018 (see page 10 of attached PDF) did a nice job of providing readers with a description of available datasets in the area of work covered by her paper.

Response: Thanks for sharing this example! I’ve included reference to two such data sources in my edit to the above request (#5), and then expand upon this at the end of the same paragraph to suggest two data sources that would benefit from including gender identity measures. I also reference LGBTdata.com, which is a great resource to access large-scale data sources that include SOGI measures.

7. Page 7. “I do, however, want to recognize the three main areas in which evidence-based strategies have been identified: individual-level treatment, school policies and programs, and state-level policies.”

a. Another thought: Would a figure work for this section?

b. Relatedly, perhaps subheadings for the next few paragraphs to distinguish the different discussions of the strategies from each other?

Response: Although I love the idea of a figure here, I had already enlisted the help of our communications team to help mock up an image to address the Knowledge to Action framework given that it reflects a model that isn’t well-known in psychology (they weren’t able to get it completed in time for my original review, but have since been able to complete it). I have, however, added subheadings for these paragraphs to better guide the reader.

8. Page 8. “However, many who need mental health treatment never receive it.” Here, might be good to either report general research on mental health service use but perhaps also note whether particular health disparities exist in access to mental health treatment for LGBTQ youth, relative to heterosexual/cisgender youth.

Response: Great suggestion, I have added some states regarding general treatment engagement (SAMHSA). Regarding disparities in treatment access: This is a really interesting point, and I’m not aware of any literature on this. I did a search came up empty-handed—hard to believe there aren’t any studies on this.

9. Page 8. “Therefore, along with developing empirically supported therapeutic strategies to support LGBTQ youth, there needs to be an effort to diversify delivery models of mental health care to broader swaths of the population.” Here, it might be useful to cite research work outlining portfolios of delivery models for mental health care generally:

a. Kazdin, A. E. (2017). Addressing the treatment gap: A key challenge for extending evidence-based psychosocial interventions. Behaviour research and therapy, 88, 7–18.

b. Kazdin, A. E. (2019). Annual Research Review: Expanding mental health services through novel models of intervention delivery. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(4), 455–472.

Response: Yes, I should have cited Kazdin here. Thanks for the recommendation!

10. Page 9. “Although there are recent strivings in this area (see Affirmative Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; Austin et al., 2018; Craig et al., 2019), a recent review of LGBTQ youth interventions for mental health, substance use, and violence identified only nine evidence-supported interventions for SGM youth mental health, with the majority of reflecting individual-level psychological and pharmacological/medical treatment or policy.” Was the expectation with this sentence to include a citation of the “recent review”? Please clarify.

Response: Apologies for the oversight here, yes. I have added the citation.

11. Pages 9–11. I really appreciate your focus on translational research, and in particular the conceptual grounding of the recommendations within the Knowledge to Action Framework. Yet, I want to challenge you to include a sixth consideration to the five important ones you identified: leveraging team science approaches to inquiry (e.g., Stokols, Hall, Taylor, & Moser, 2008). One element of the work you cover that I very much admire and I would want readers to see a mention of is the idea that this work incorporates frameworks, methodologies, data structures, and findings across myriad disciplines (e.g., Family Science, Epidemiology, Psychology, Pediatrics, Human Development, Counseling, to name a few). The degree to which we continue to see fruitful lines of work mature on these important topics, I think, will hinge in large part on whether we dedicate considerable time and attention to providing the next generation of researchers with skills/training on the how-to’s of team science. Most of us learn how to do this kind of work “by accident” or “trial by error.” We need more structured programs designed to facilitate inspiring early career researchers to form multidisciplinary teams, as well as strategies for developing, implementing, and sustaining these collaborative endeavors. I don’t think you have to go into specifics but I also think this is a place where you can motivate readers who are excited about the prospect of thinking about these issues in a translational way, but struggle with the idea about how to do the work (e.g., does doing this work mean I have to become some superhero researcher like Jessica F. or Mark H. who received training in like 2–3 different disciplines?).

a. Stokols, D., Hall, K.L., Taylor, B.K., & Moser, R.P. (2008). The science of team science: overview of the field and introduction to the supplement. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 35, S77-S89. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9x5078wj

Response: I absolutely love this suggestion, thank you! I’ve now added a 6th consideration for the article to reflect these ideas. I hope you don’t mind, but you had some great phrases that I incorporated into this section. I would appreciate some scrutiny here, though. This is an idea I haven’t though deeply about (like the others), so I appreciate any critiques if you have them.

Also, I definitely can’t claim the superhero researcher label, and feel honored to be mentioned in the same sentence as Mark – I aspire. ☺

12. Page 11, line 31. “vantages” should read “vantage”?

Response: This has been addressed.

13. Page 14, line 17. “addresses” should read “address”?

Response: This has been addressed.

14. Page 14, line 22. “strategies” should read “strategy”?

Response: This has been addressed.

15. Page 14. “It is worth noting and emphasizing that LGBTQ youth demonstrate enormous strength in the face of adversity.” I have a sense of why you might have included this sentence, namely to not give the impression that addressing LGBTQ youth’s strengths is not an acknowledgement that all LGBTQ youth experience deficits in strengths-based domains, far from it. In fact, implied in your cogent discussions earlier in the paper is the idea that, because youth today tend to disclose their LGBTQ identities earlier on in development relative to youth from yesteryear, they are doing so in, for the most part, environments that vary considerably as to whether they affirm key elements of their identities. I think you can unpack this sentence a little more (e.g., 2–3 sentences), such that you can get to a place where I sense you want to go: We need strategies to facilitate supporting existing strengths and building new ones. Otherwise, I fear that the reader might get a false impression of this very important section of your paper, namely the idea that, if LGBTQ youth have enormous strengths at baseline, then why would they need more strengths.

Response: Thanks for this suggestion, I think it’s spot-on. I’ve added some additional sentences to make this more explicit (top of pg. 15).

16. Page 16, line 33, end of line. “must to” should read “must”?

Response: This has been addressed.

17. Page 18. In your brief mention of research on the intersectionality of LGBTQ identifies and neurodiversity/autism, you might benefit from this recent JCCAP article: Strang, J. F., Knauss, M., van der Miesen, A., McGuire, J. K., Kenworthy, L., Caplan, R., ... & Balleur, A. (2020). A clinical program for transgender and gender-diverse neurodiverse/autistic adolescents developed through community-based participatory design. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2020.1731817

Response: Great suggestion, thank you!

18. Page 21. “However, the impact of these policies take time.” Two things: (a) “take” should read “takes”? (b) Another thought: It might be useful here to cite a study that’s an example of this statement. Although not specifically focused on LGBTQ youth, one of Mark’s papers, I think, works really well here: Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Bränström, R., & Pachankis, J. E. (2018). Societal-level explanations for reductions in sexual orientation mental health disparities: Results from a ten-year, population-based study in Sweden. Stigma and Health, 3(1), 16–26. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000066

Response: Great reference for this point, thank you!

A quick note on language; I use “LGBTQ” and “sexual and gender minority” interchangeably, intentionally, and in variation (e.g., “sexual minority” or “LGB” and “gender minority”) to reflect differences across study samples and measurement.

I intentionally use identity-first language given our focus on intersectional perspectives with regards to disability status and LGBTQ status (Dunn & Andrews, 2015)

REFERENCES

- Allen KD, Hammack PL, & Himes HL (2012). Analysis of GLBTQ youth community-based programs in the United States. Journal of Homosexuality, 59(9), 1289–1306. 10.1080/00918369.2012.720529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen SH (2020). Redoing gender, redoing family: A mixed-methods examination of family complexity and gender heterogeneity among transgender families (Publication #27834394). [Doctoral Dissertation, University of Maryland]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman A, Smith TW, & Calancie L (2014). Practice-based evidence in public health: Improving reach, relevance, and results. Annual Review of Public Health, 35(1), 47–63. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anhalt K, Toomey RB, & Shramko M (2020). Latinx sexual minority youth adjustment in the context of discrimination and internalized homonegativity: The moderating role of cultural orientation processes. Journal of Latinx Psychology, 8(1), 41–57. 10.1037/lat0000134 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Austin A, Craig SL, & D’Souza SA (2018). An AFFIRMative cognitive behavioral intervention for transgender youth: Preliminary effectiveness. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 49(1), 1–8. 10.1037/pro0000154 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Austin CP (2018). Translating translation. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 17(7). 10.1038/nrd.2018.27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett LM, & Gadlin H (2012). Collaboration and team science: From theory to practice. Journal of Investigative Medicine, 60(5), 768–775. 10.231/JIM.0b013e318250871d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson PL, Leffert N, Scales PC, & Blyth DA (1998). Beyond the “village” rhetoric: Creating healthy communities for children and adolescents. Applied Developmental Science, 2, 138–159. 10.1080/10888691.2012.642771 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benson PL, Scales PC, & Syvertsen AK (2011). The contribution of the developmental assets framework to positive youth development theory and practice In Advances in Child Development and Behavior (Vol. 41, pp. 197–230). 10.1016/B978-0-12-386492-5.00008-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop MD, Fish JN, Hammack PL, & Russell ST (in press). Sexual identity development milestones in three generations of sexual minority people: A national probability sample. Developmental Psychology Advance online publication. 10.1037/dev0001105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brechwald WA, & Prinstein MJ (2011). Beyond homophily: A decade of advances in understanding peer influence processes. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(1), 166–179. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00721.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson RC, Colditz GA, & Proctor EK. (Eds.). (2018). Dissemination and implementation research in health: Translating science to practice (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cahill SR, & Makadon HJ (2017). If they don’t count us, we don’t count: Trump administration rolls back sexual orientation and gender identity data collection. LGBT Health, 4(3), 171–173. 10.1089/lgbt.2017.0073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzo JP, & Blashill AJ (2018). Child sexual orientation and gender identity in the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Cohort Study. JAMA Pediatrics, 172(11), 1090–1092. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Berglund ML, Ryan JAM, Lonczak HS, & Hawkins JD (2004). Positive youth development in the united states: Research findings on evaluations of positive youth development programs. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 591(1), 98–124. 10.1177/0002716203260102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- CenterLink, & Movement Advancement Project. (2018). 2018 LGBT Community Center Survey Report: Assessing the capacity and programs of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community centers. Retrieved from https://www.lgbtmap.org/file/2018-lgbt-community-center-survey-report.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Compendium of Evidence-Based Interventions and Best Practices for HIV Prevention. Retrieved from https:www.cdc.gov/hiv/research/interventionresearch/compendium/rr/complete.html [Google Scholar]

- Choi SK, Wilson B, Shelton J, & Gates G (2015). Serving Our Youth 2015: The Needs and Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Questioning Youth Experiencing Homelessness. The Williams Institute with True Colors Fund; Retrieved from https://escholarship-org.proxy-um.researchport.umd.edu/uc/item/1pd9886n [Google Scholar]

- Clark CM (2016). Reducing heterosexist attitudes toward relationships in young children [Doctoral Dissertation, University of Texas]. Retrieved from 10.15781/T2KD1QQ99 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coll CG, Crnic K, Lamberty G, Wasik BH, Jenkins R, García HV, & McAdoo HP (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development, 67(5), 1891–1914. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01834.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter RWS, Egan JE, Kinsky S, Friedman MR, Eckstrand KL, Frankeberger J, Folb BL,… & Miller E (2019). Mental health, drug, and violence interventions for sexual/gender minorities: A systematic review. Pediatrics, 144(3), e20183367 10.1542/peds.2018-3367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter RWS, Jun H-J, Truong N, Mair C, Markovic N, Friedman MR, Silvestre AJ, Stall R, & Corliss HL (2019). Effects of familial and non-familial warmth during childhood and adolescence on sexual-orientation disparities in alcohol use trajectories and disorder during emerging adulthood. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 205, 107643 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig SL, Austin A, & Alessi EJ (2019). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for sexual and gender minority youth mental health In Pachankis JE & Safren SA (Eds.), Handbook of Evidence-Based Mental Health Practice with Sexual and Gender Minorities (pp. 25–50). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Craig SL, Austin A, Alessi EJ, McInroy L, & Keane G (2017). Minority stress and HERoic coping among ethnoracial sexual minority girls: Intersections of resilience. Journal of Adolescent Research, 32(5), 614–641. 10.1177/0743558416653217 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Craig SL, McInroy L, McCready LT, & Alaggia R (2015). Media: A catalyst for resilience in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth. Journal of LGBT Youth, 12(3), 254–275. 10.1080/19361653.2015.1040193 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Grossman AH, & Starks MT (2008). Families of gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth: What do parents and siblings know and how do they react? Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 4(1), 95–115. 10.1080/15504280802084506 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Day JK, Fish JN, Grossman AH, & Russell ST (2020). Gay-straight alliances, inclusive policy, and school climate: LGBTQ youths’ experiences of social support and bullying. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 30(S2), 418–430. 10.1111/jora.12487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond GM, Boruchovitz-Zamir R, Gat I, & Nir-Gottlieb O (2019). Relationship-focused therapy for LGBTQ individuals and their parents In Pachankis JE & Safron SA (Eds.), Handbook of Evidence-Based Mental Health Practice with Sexual and Gender Minorities (pp. 430–456). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond G, Russon J, & Levy S (2016). Attachment-based family therapy: A review of the empirical support. Family Process, 55(3), 595–610. 10.1111/famp.12241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn DS, & Andrews EE (2015). Person-first and identity-first language: Developing psychologists’ cultural competence using disability language. The American Psychologist, 70(3), 255–264. 10.1037/a0038636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg ME, & Resnick MD (2006). Suicidality among gay, lesbian and bisexual youth: the role of protective factors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39(5), 662–668. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.04.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feller SC, Castillo EG, Greenberg JM, Abascal P, Van Horn R, & Wells KB (2018). Emotional well-being and public health: Proposal for a model national initiative. Public Health Reports, 133(2), 136–141. 10.1177/0033354918754540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein BA (2019). The rejection sensitivity model as a framework for understanding sexual minority mental health. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 10.1007/s10508-019-1428-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish JN, Baams L, & McGuire JK (2020). LGBTQ mental health issues among children and youth In Rothblum ED (Ed.), Oxford Handbook of LGBTQ Mental Health (pp. 229–244). [Google Scholar]

- Fish JN, & Baams L (2018). Trends in alcohol-related disparities between heterosexual and sexual minority youth from 2007 to 2015: Findings from the youth risk behavior survey. LGBT Health, 5(6), 359–367. 10.1089/lgbt.2017.0212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish JN, & Russell ST (2019a, April). Age differences in sexual-orientation-related substance use disparities among youth: Findings from population-based data. Society for the Research in Child Development Biennial Meeting, Baltimore, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Fish JN, & Russell ST (2019b, April). Age trends in sexual-orientation-related disparities in homophobic bullying and its association with depressive symptoms. Society for Research in Child Development Biennial Meeting. [Google Scholar]

- Fish JN, Moody RL, Grossman AH, & Russell ST (2019). LGBTQ youth-serving community-based organizations: Who participates and what difference does it make? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(12), 2418–2431. 10.1007/s10964-019-01129-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish JN, Turner B, Phillips G, & Russell ST (2019). Cigarette smoking disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth. Pediatrics, e20181671 10.1542/peds.2018-1671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish JN, Watson RJ, Porta CM, Russell ST, & Saewyc EM (2017). Are alcohol-related disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth decreasing? Addiction, 112(11), 1931–1941. 10.1111/add.13896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming ES, Perkins J, Easa D, Conde JG, Baker RS,… Norris KC (2008). The role of translational research in addressing health disparities: A conceptual framework. Ethnicity & Disease, 18(2 Suppl 2), S2–155–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost DM, Fine M, Torre ME, & Cabana A (2019). Minority stress, activism, and health in the context of economic precarity: Results from a national participatory action survey of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and gender non-conforming youth. American Journal of Community Psychology, 63(3–4), 511–526. 10.1002/ajcp.12326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandy-Guedes ME, & Paceley MS (2019). Activism in Southwestern queer and trans young adults after the marriage equality era. Affilia. 10.1177/0886109919857699 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- GLAAD. (2020). Where we are on TV 2019–2020. GLAAD; Retrieved from https://www.glaad.org/sites/default/files/GLAAD%20WHERE%20WE%20ARE%20ON%20TV%202019%202020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Goldbach JT, & Gibbs JJ (2017). A developmentally informed adaptation of minority stress for sexual minority adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 55, 36–50. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg T, Reisner SL, Harper GW, Gamarel KE, & Stephenson R (2020). State policies and healthcare use among transgender people in the U.S. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, S0749379720301008 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.01.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham ID, Kothari A, McCutcheon C, Angus D, Banner D, Bucknall T, …Nguyen T (2018). Moving knowledge into action for more effective practice, programmes and policy: Protocol for a research programme on integrated knowledge translation. Implementation Science, 13(1), 22 10.1186/s13012-017-0700-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, Straus SE, Tetroe J, Caswell W, & Robinson N (2006). Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map? Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 26(1), 13–24. 10.1002/chp.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammack PL (2005). The life course development of human sexual orientation: An integrative paradigm. Human Development, 48(5), 267–290. 10.1159/000086872 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML (2011). The social environment and suicide attempts in lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Pediatrics, 127(5), 896–903. 10.1542/peds.2010-3020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Bränström R, & Pachankis JE (2018). Societal-level explanations for reductions in sexual orientation mental health disparities: Results from a ten-year, population-based study in Sweden. Stigma and Health, 3(1), 16–26. 10.1037/sah0000066 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Jun H-J, Corliss HL, & Austin SB (2014). Structural stigma and cigarette smoking in a prospective cohort study of sexual minority and heterosexual youth. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 47(1), 48–56. 10.1007/s12160-013-9548-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler Mark L. (2009). How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin, 135(5), 707–730. 10.1037/a0016441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML (2016). Structural stigma and health inequalities: Research evidence and implications for psychological science. The American Psychologist, 71(8), 742–751. 10.1037/amp0000068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML (2017). Advancing research on structural stigma and sexual orientation disparities in mental health among Youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 46(3), 463–475. 10.1080/15374416.2016.1247360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, & Keyes KM (2013). Inclusive anti-bullying policies and reduced risk of suicide attempts in lesbian and gay youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(1, Supplement), S21–S26. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler Mark L., & McLaughlin KA (2014). Structural stigma and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenocortical axis reactivity in lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 47(1), 39–47. 10.1007/s12160-013-9556-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler Mark L., & Pachankis JE (2016). Stigma and minority stress as social determinants of health among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: Research evidence and clinical implications. Pediatric Clinics, 63(6), 985–997. 10.1016/j.pcl.2016.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler Mark L., Birkett M, Van Wagenen A, & Meyer IH (2014). Protective school climates and reduced risk for suicide ideation in sexual minority youths. American Journal of Public Health, 104(2), 279–286. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler Mark L., Schwab-Reese L, Ranapurwala SI, Hertz MF, & Ramirez MR (2015). Associations between antibullying policies and bullying in 25 states. JAMA Pediatrics, 169(10), e152411–e152411. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.2411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn SS (2006). Heterosexual adolescents’ and young adults’ beliefs and attitudes about homosexuality and gay and lesbian peers. Cognitive Development, 21(4), 420–440. 10.1016/j.cogdev.2006.06.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, & Spicer P (2006). Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology, 42(5), 747–770. 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns MM, Lowry R, Andrzejewski J, Barrios LC, Demissie Z, McManus T, Rasberry CN, Robin L, & Underwood JM (2019). Transgender identity and experiences of violence victimization, substance use, suicide risk, and sexual risk behaviors among high school students—19 states and large urban school districts, 2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(3), 67–71. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6803a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns MM, Lowry R, Rasberry CN, Dunville R, Robin L, Pampati S, Stone DM, & Mercer Kollar LM (2018). Violence victimization, substance use, and suicide risk among sexual minority high school students—United States, 2015–2017. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67 10.15585/mmwr.mm6743a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz-Wise SL, & Hyde JS (2012). Victimization experiences of lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals: A meta-analysis. Journal of Sex Research, 49(2–3), 142–167. 10.1080/00224499.2011.637247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE (2017). Addressing the treatment gap: A key challenge for extending evidence-based psychosocial interventions. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 88, 7–18. 10.1016/j.brat.2016.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE (2019). Annual Research Review: Expanding mental health services through novel models of intervention delivery. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(4), 455–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ, Georgiades K, Green JG, Gruber MJ, He J, …Merikangas KR (2012). Prevalence, persistence, and sociodemographic correlates of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. Archives of General Psychiatry, 69(4), 372–380. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Cohen J, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Milne BJ, & Poulton R (2003). Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: Developmental follow-back of a prospective-longitudinal cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60(7), 709–717. 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kull RM, Greytak EA, Kosciw JG, & Villenas C (2016). Effectiveness of school district antibullying policies in improving LGBT youths’ school climate. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 3(4), 407–415. 10.1037/sgd0000196 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- la Roi C, Kretschmer T, Dijkstra JK, Veenstra R, & Oldehinkel AJ (2016). Disparities in depressive symptoms between heterosexual and lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth in a Dutch cohort: The TRAILS study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(3), 440–456. 10.1007/s10964-015-0403-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu RT, Walsh RFL, Sheehan AE, Cheek SM, & Carter SM (2020). Suicidal ideation and behavior among sexual minority and heterosexual youth: 1995–2017. Pediatrics 10.1542/peds.2019-2221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Dietz LJ, Friedman MS, Stall R, Smith HA, McGinley J, Thoma BC, Murray PJ, D’Augelli AR, & Brent DA (2011). Suicidality and depression disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Adolescent Health, 49(2), 115–123. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin‐Storey A, & Fish J (2019). Victimization disparities between heterosexual and sexual minority youth from ages 9 to 15. Child Development, 90(1), 71–81. 10.1111/cdev.13107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martos AJ, Wilson PA, & Meyer IH (2017). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) health services in the United States: Origins, evolution, and contemporary landscape. PLOS ONE, 12(7), e0180544 10.1371/journal.pone.0180544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx RA, & Kettrey HH (2016). gay-straight alliances are associated with lower levels of school-based victimization of LGBTQ+ youth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(7), 1269–1282. 10.1007/s10964-016-0501-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]