Abstract

Background:

Organochlorine pesticides are detectable in serum from most adults. Animal studies provide evidence of pesticide effects on sex hormones, suggesting that exposures may impact human reproductive function. Mounting evidence of sex differences in chronic diseases suggest that perturbations in endogenous sex hormones may influence disease risk. However, the association between organochlorine pesticide exposure and sex hormone levels in males across the lifespan is not well understood.

Methods:

We evaluated cross-sectional associations of lipid-adjusted serum concentrations of β-hexachlorocyclohexane, hexachlorobenzene, heptachlor epoxide, oxychlordane, dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (DDE), p,p’-dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), trans-nonachlor, and mirex in relation to sex steroid hormone levels [testostosterone (ng/dL), sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG; nmol/L), estradiol (pg/mL), and androstanediol glucuronide (ng/dL)] in a sample of 748 males aged 20 years and older from the 1999–2004 cycles of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Survey-weighted linear regression models were performed to estimate geometric means (GM) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for quartiles of lipid-adjusted pesticide concentrations, adjusting for age, race, body mass index, serum lipids, smoking, education, and survey cycle.

Results:

Hexachlorobenzene concentration was positively associated with total estradiol (GM Q4= 43.2 pg/mL (95% CI 36.5–51.1) vs. Q1 GM=25.6 pg/mL (24.1–27.3), p-trend <0.0001) and free estradiol (GM Q4= 0.77 pg/mL (95% CI 0.64–0.93) vs. Q1 GM=0.47 pg/mL (0.44–0.51), p-trend =0.002). Serum DDT concentration was positively associated with total estradiol (GM Q4=31.6 pg/mL (95% CI 25.9–38.5) vs. Q1 GM=27.3 pg/mL (25.9–28.7), p-trend= 0.05) and free estradiol (GM Q4= 0.60 pg/mL (95% CI 0.48–0.76) vs. Q1 GM=0.50 pg/mL (0.47–0.53), p-trend 0.02). There was a suggestive inverse association of DDT and SHBG (GM Q4= 29.2 nmol/L (95% CI 23.8–35.9) vs. Q1 GM=33.9 nmol/L (32.3–35.5), p-trend 0.07). A positive association of β-hexachlorocyclohexane with total estradiol (GM Q4=30.3 pg/mL (95% CI 26.5–34.6) vs. Q1 GM=26.7 pg/mL (24.5–29.0), p-trend=0.09) was also suggestive but did not reach statistical significance. No distinct associations were observed for other hormone levels or other organochlorine pesticides.

Conclusions:

Our findings suggest that select organochlorine pesticides may alter male estradiol levels. The positive associations with estradiol may implicate sex hormones as a possible mechanism for disease risk among those with organochlorine pesticide exposure.

Keywords: Endocrine disruptors, Estrogenic compounds, Organochlorine pesticides, Sex hormones, Estradiol, NHANES

Introduction

Organochlorine pesticides are contaminants that persist in the environment and act as endocrine disruptors in the human body by mimicking, blocking, or interfering with the actions of endogenous hormones (Gore, Chappell et al. 2015). Prior to being banned from use, organochlorines were heavily used internationally to interrupt malaria transmission and for agricultural purposes. Extended use of organochlorines such as p,p’-dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), its metabolite dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (DDE), heptachlor epoxide, hexachlorobenzene (HCB), β-hexachlorocyclohexane, oxychlordane, and trans-nonachlor is particularly relevant to human health due to the persistence of these organochlorines in the environment, bioaccumulation in the food chain, and their ability to accumulate in human adipose and other tissues. Organochlorine pesticides have been detected in serum from a majority of persons in the United States and globally and are especially high among adults aged 60 and older (Jaga and Dharmani 2003, Patterson, Wong et al. 2009, Martinez, Trejo-Acevedo et al. 2012, Porta, Pumarega et al. 2012, Sjödin, Jones et al. 2014).

Evidence of sex differences in chronic diseases such as diabetes and kidney disease (Okada, Yanai et al. 2014, Shen, Cai et al. 2017, Madrigal, Ricardo et al. 2019) suggest that perturbations in sex hormone levels may influence disease risk. However, studies of associations between organochlorine pesticide exposures and sex hormone levels in adult males from the general population are limited. Among 178 males living near the United States Great Lakes with measurements of DDE, testosterone, and sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG), no correlation of exposure with hormone levels was observed (Persky, Turyk et al. 2001). However, in a subsample of 56 male participants from the Great Lakes cohort, DDE levels were inversely associated with estrone sulfate (Turyk, Anderson et al. 2006). In a pooled study of males living in Greenland, Poland, Sweden, and Ukraine, DDE was positively associated with SHBG only among the Ukrainians (Giwercman, Rignell-Hydbom et al. 2006), but HCB was positively associated with SHBG among males from Ukraine and Poland (Specht, Bonde et al. 2015). In a sample of 341 males in the United States, no association was observed between HCB nor DDE with SHBG, testosterone, or estradiol (Ferguson, Hauser et al. 2012). There are several studies that have examined the association of organochlorine pesticides with sex hormones among males who have been occupationally exposed or live in highly contaminated areas. Some have reported null findings (Martin, Harlow et al. 2002, Cocco, Loviselli et al. 2004), but others have observed conflicting associations. For example, among 304 males from a rural area of Brazil that was highly contaminated with organochlorine pesticides, heptachlor and DDT concentrations were inversely associated with testosterone levels (Freire, Koifman et al. 2014). However, among 97 males in Thailand, of whom 63.9% had used DDT for farming, neither p,p’-DDE nor p,p’-DDT were associated with testosterone levels but p,p’-DDE levels were inversely associated with plasma estradiol levels after adjustment for age and body mass index (BMI) (Asawasinsopon, Prapamontol et al. 2006).

To the best of our knowledge, the association between organochlorine pesticides and concentrations of sex hormones has not been investigated using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). The purpose of this study is to investigate the associations between multiple organochlorine pesticide exposures and sex hormones including testosterone, free testosterone, estradiol, free estradiol, androstanediol glucuronide, and SHBG in a nationally representative sample of adult males in the United States. We explored age, BMI, and prevalent diabetes as effect modifiers of these associations to evaluate if associations might be stronger among certain subgroups. We expected that older participants would have higher levels of organochlorine pesticides and that age would be inversely associated with hormone levels, suggesting that pooled associations might mask age-specific associations. BMI was considered as a potential effect modifier since it is a proxy for fat mass and organochlorine pesticides are stored in fat, which could potentially impact sex hormone metabolism in this tissue compartment. Some organochlorine pesticides have been associated with diabetes prevalence in prior studies, therefore we hypothesized that associations might differ due to different etiologic mechanisms among those with and without diabetes (i.e., that we might only observe associations of organochlorines and hormones among males with diabetes).

Methods

Study population

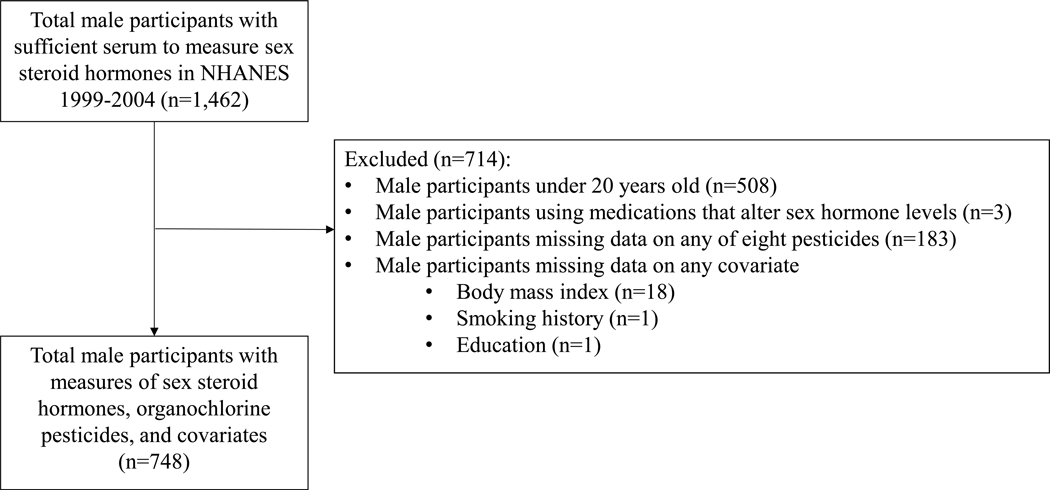

The NHANES utilizes interviews and physical examinations to provide a nationally representative sample of non-institutionalized people living in the United States. The NHANES study protocols are approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Center for Health Statistics, and participants provided written informed consent (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). 2018). This study combined the 1999–2004 cycles of NHANES to form the analytic data set. Persistent chlorinated pesticides and pesticide metabolites were measured in serum from male participants aged 12 years and older on a one-third subsample in each cycle. Concentrations of sex steroid hormones were additionally measured from male participants in the one-third pesticide subsample for whom sufficient stored serum specimens were available in the repository. We excluded males under 20 years old, using hormone-modifying medications (e.g., antiandrogens, 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors, hormone modifiers, adrenal cortical steroids) or with missing data for any pesticide or covariate (body mass index, education, and smoking history). We substituted the value of the limit of detection divided by the square root of two for any recorded hormone value that was negative (n=10). The final analytic sample consisted of 748 observations (Supplemental Figure 1).

Exposure measurements

A one-third subsample of participants aged 12 years and older was selected for organochlorine pesticide measurements. Serum concentrations of eight persistent chlorinated pesticides and metabolites measured by high-resolution gas chromatography/isotope-dilution high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRGC/ID-HRMS) at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Environmental Health were detectable in ≥40% of the samples. This included lipid-adjusted concentrations (ng/g lipid) of β-hexachlorocyclohexane, HCB, heptachlor epoxide, oxychlordane, p,p’-DDE, p,p’-DDT, trans-nonachlor, and mirex. A correction factor of 0.644 was applied to the β-hexachlorocyclohexane concentrations for the 1999–2000 cycle as advised by NHANES. We used the value of the limit of detection divided by the square root of two, as substituted by NHANES, for any sample below the limit of detection. We categorized each lipid-adjusted pesticide as quartiles based on the distribution in the sample and the first exposure category included the proportion of participants with pesticide concentrations below the limit of detection. There were zero non-detects for DDE. The first exposure quartile was considered the referent group in all categorical analyses.

Outcome measurements

Males selected for the one-third subsample that measured organochlorine pesticide levels were also selected to have sex steroid hormones measured if serum was available in the repository. Measurements of serum concentrations of testosterone (ng/mL), sex hormone binding globulin (nmol/L), estradiol (pg/mL), and androstanediol glucuronide (ng/mL) were completed. Concentrations of testosterone (ng/dL), SHBG (nmol/L), serum albumin (g/dL), and estradiol (pg/mL) were used to calculate concentrations of unbound (free) testosterone and estradiol according to the method supplied by Vermeulen (Belgorosky, Escobar et al. 1987, Vermeulen, Verdonck et al. 1999). The ratio of testosterone to estradiol was derived by dividing testosterone concentration in picogram per milliliter by estradiol concentration in picogram per milliliter.

Covariates

Interviews were conducted to collect participant information on age (continuous; years), education level (less than high school, high school graduate, some college, or college graduate/additional education beyond college), and race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, or other). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing measured weight in kilograms by measured height in meters squared. BMI was used as a continuous variable and categorized into normal (BMI <25), overweight (BMI 25–29.9), or obese (BMI ≥30) for descriptive purposes. Total cholesterol (mg/dL) and triglycerides (mg/dL) were analyzed with a Hitachi Model 704 multichannel analyzer (Boehringer Mannheim Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). We used the formula: total lipid = [total cholesterol (mg/dL) × 2.27] + triglycerides (mg/dL) + 62.3 mg/dL to calculate total serum lipids, which was used as a covariate in the models and to lipid standardize organochlorine pesticide measurements (Phillips, Pirkle et al. 1989, Bernert, Turner et al. 2007). Participants reported current and past use of cigarettes during the interview. This was captured as never, former, infrequent, or daily smoking. For former smokers, we dichotomized time elapsed since quitting as less than/equal to or greater than five years. We determined diabetes disease status (non-diabetic or diabetic) using a combination of self-reported questionnaire items and antidiabetic medication use (i.e., antidiabetic agents). We supplemented this information with measured concentrations of glycohemoglobin from blood samples taken during the study visit. Glycohemoglobin was measured using the A1c G7 HPLC Glycohemoglobin Analyzer. Participants were classified as having diabetes if they reported a prior diagnosis by their physician, were using antidiabetic medication, or had glycohemoglobin values of 6.5% or greater.

Statistical analysis

All analyses utilized the special subsample weights, strata, and primary sampling units to account for the complex NHANES sampling design and nonresponse using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and STATA 13 (StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP) survey procedures. The sex steroid hormone and lipid adjusted pesticide distributions were skewed, and the natural log transformation was applied. Weighted geometric means and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated for the continuous skewed hormone (age-adjusted) and pesticide concentrations, by covariates. T-tests were used to evaluate if levels of each hormone or pesticide differed by levels of covariate categories.

Linear regression models were built for continuous log transformed sex steroid hormones (dependent variables) using a forward approach beginning with individual models of each lipid standardized pesticide concentration. We modeled each pesticide concentration using quartiles to allow for non-linear dose responses, and as an ordinal variable to test for linear trend. Models were adjusted for age (continuous), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic African-American, Hispanic, or other), body mass index (continuous), self-reported smoking history (never, 5+ years since last cigarette, <5 years since last cigarette, infrequent current smoker, daily smoker), education level (less than high school, high school grad, some college or more), total serum lipids (continuous) (O’Brien, Upson et al. 2016), and survey year. Estimates did not substantively change when age and body mass index were adjusted for using continuous cubic splines (age with four knots at 21, 39, 56, and 81 years; body mass index with four knots at 20, 25, 29, and 37). Due to log transformation being applied to all the outcomes, we present results as geometric means with 95% CIs to aid in interpretation.

To assess if effect modification was present, we added a cross-product term between each categorized pesticide concentration and the effect modifier of interest (diabetes (yes/no), age (continuous), and BMI (continuous)) to the adjusted linear regression model one at a time and in combination. A post-estimation adjusted Wald test was used to jointly evaluate all coefficients associated with each cross-product term. We considered a p-value less than 0.05 statistically significant when interpreting cross-product terms. For statistically significant interactions, we used stratified linear regression models and assessed whether or not stratum-specific estimates of associations were meaningful.

To address statistical analytical issues for correlated exposures and the need for data reduction among the eight organochlorine pesticides to explore the impact of exposure mixtures, we used principal component analysis (PCA) to create combinations of exposure variables to use in linear regression models. After assessing the correlation among log transformed lipid-adjusted pesticide concentrations using Pearson correlation coefficients, we used PCA methods to estimate eigenvalues for each component using log transformed pesticide concentrations. The scree plot was examined to assess the explained variance of each principal component. We used the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure to evaluate the adequacy of the sample. Principal components with eigenvalues greater than 0.90 were retained in the analysis, and an orthogonal rotation was applied to each component. New variables were created using the predicted scores of the selected components, which were then categorized into quartiles and used in adjusted linear regression models for each hormone outcome.

Results

Sample description

Among the 748 males in the study sample, the average age was 44.8 (SD 0.72) years and 73% were non-Hispanic white. A majority (84%) reported being born in the United States. As shown in Table 1, geometric mean hormone concentrations varied by age and by body mass index. The geometric mean exposure concentrations for the measured organochlorine pesticides across various demographic characteristics of the study sample are shown in Table 2 and in the online Supplemental Table 1. As expected, pesticide concentrations were highest among the oldest participants. Levels of β-hexachlorocyclohexane, p,p’-DDE, and p,p’-DDT were higher among those who reported being born outside of the United States relative to those who were born in the United States. Relative to those without, males with diabetes had higher levels of most of the pesticides except for HCB.

Table 1.

Overall weighted characteristics and age-adjusted geometric mean hormone levels by levels of covariates among NHANES 1999–2004 male participants (n=748).

| Overall | Testosterone (ng/dL) | Estradiol (pg/mL) | Sex hormone binding glubulin (nmol/L) | Androstanediol glucuronide (ng/mL) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | GM (95% CI) | p-value | GM (95% CI) | p-value | GM (95% CI) | p-value | GM (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Overall | 464 (444, 484) | 30.0 (28.6, 31.4) | 32.1 (30.5, 33.6) | 7.3 (7.0, 7.7) | |||||

| Age in years, 20–39 | 266 (40.9) | 528 (499, 559) | <0.0001 | 31.1 (28.8, 33.5) | 0.003 | 26.4 (24.3, 28.6) | <0.0001 | 7.7 (7.2, 8.2) | 0.0002 |

| 40–59 | 242 (40.3) | 444 (409, 482) | 0.004 | 31.0 (28.6, 33.6) | 0.002 | 32.7 (30.1, 35.5) | <0.0001 | 7.3 (6.7, 8.0) | 0.05 |

| 60+ | 240 (18.8) | 382 (356, 411) | ref | 25.7 (23.5, 28.0) | ref | 47.4 (44.4, 50.5) | ref | 6.5 (6.0, 7.2) | ref |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||

| African-American, nH | 133 (9.6) | 547 (505, 592) | 0.006 | 37.3 (32.9, 42.3) | <0.0001 | 37.7 (33.9, 41.9) | 0.03 | 7.1 (6.6, 7.6) | 0.47 |

| White, nH | 392 (73.4) | 451 (426, 478) | 0.22 | 29.7 (27.8, 31.7) | 0.06 | 31.4 (29.6, 33.3) | 0.50 | 7.4 (7.0, 7.9) | 0.92 |

| Hispanic | 197 (12.1) | 475 (447, 505) | ref | 26.4 (24.2, 28.9) | ref | 32.3 (30.1, 34.7) | ref | 7.4 (6.7, 8.1) | ref |

| Other | 26 (4.9) | 477 (426, 534) | 0.89 | 30.4 (24.4, 37.8) | 0.26 | 31.3 (27.6, 35.4) | 0.63 | 6.1 (4.5, 8.3) | 0.26 |

| Education,< High school | 234 (18.8) | 497 (468, 527) | 0.12 | 29.2 (27.2, 31.3) | 0.81 | 36.3 (33.7, 39.1) | 0.0007 | 7.2 (6.7, 7.8) | 0.89 |

| High school graduate | 167 (26.2) | 468 (438, 499) | 0.98 | 32.1 (29.0, 35.6) | 0.32 | 31.7 (28.8, 34.8) | 0.34 | 7.2 (6.5, 7.9) | 0.98 |

| Some college | 207 (30.9) | 447 (418, 478) | 0.77 | 29.0 (26.5, 31.6) | 0.78 | 31.8 (29.4, 34.4) | 0.30 | 7.6 (7.1, 8.2) | 0.41 |

| ≥ College graduate | 140 (24.1) | 457 (409, 511) | ref | 29.6 (26.4, 33.2) | ref | 29.7 (27.1, 32.6) | ref | 7.2 (6.3, 8.1) | ref |

| Born in the United States, Yes | 571 (84.5) | 463 (442, 486) | 0.66 | 30.2 (28.7, 31.8) | 0.54 | 32.5 (30.9, 34.3) | 0.19 | 9.3 (8.9, 9.7) | 0.10 |

| No | 177 (15.5) | 467 (442, 494) | 28.6 (24.4, 33.7) | 29.5 (25.9, 33.7) | 9.8 (9.2, 10.5) | ||||

| Body mass index, kg/m2, <25 | 224 (29.2) | 590 (563, 617) | <0.0001 | 29.1 (27.1, 31.3) | 0.01 | 44.0 (41.1, 47.1) | <0.0001 | 6.4 (6.0, 6.9) | 0.0005 |

| 25 to <30 | 310 (40.8) | 460 (434, 487) | 0.004 | 28.0 (26.3, 29.8) | 0.002 | 31.2 (29.4, 33.2) | 0.0001 | 7.4 (7.0, 7.8) | 0.02 |

| ≥30 | 214 (30.0) | 373 (335, 415) | ref | 33.8 (30.7, 37.1) | ref | 24.5 (22.5, 26.6) | ref | 8.2 (7.4, 9.1) | ref |

| High triglycerides ≥ 200 mg/dL | 148 (22.8) | 412 (370, 460) | 0.01 | 30.2 (26.4, 34.4) | 0.91 | 25.5 (23.3, 27.9) | <0.0001 | 8.2 (7.3, 9.3) | 0.02 |

| <200 mg/dL | 600 (77.2) | 480 (461, 501) | 29.9 (28.4, 31.4) | 34.3 (32.6, 36.1) | 7.1 (6.7, 7.4) | ||||

| High total cholesterol ≥ 200 mg/dL | 361 (49.6) | 441 (419, 465) | 0.03 | 27.4 (25.8, 29.2) | 0.002 | 30.3 (28.8, 32.0) | 0.02 | 7.5 (7.0, 8.1) | 0.34 |

| <200 mg/dL | 387 (50.4) | 487 (455, 521) | 32.7 (30.3, 35.3) | 33.8 (31.2, 36.6) | 7.1 (6.7, 7.6) | ||||

| Diabetes | 85 (8.0) | 405 (366, 447) | 0.01 | 33.9 (28.7, 40.0) | 0.14 | 24.0 (20.0, 28.8) | 0.001 | 6.9 (5.7, 8.4) | 0.54 |

| Non-diabetic | 663 (92.0) | 469 (449, 491) | 29.6 (28.2, 31.2) | 32.9 (31.4, 34.4) | 7.4 (7.0, 7.7) | ||||

| Smoking status, Never | 323 (43.7) | 439 (407, 474) | ref | 30.0 (28.3, 31.8) | ref | 29.3 (27.6, 31.1) | ref | 7.9 (7.3, 8.6) | ref |

| Former (5+ years) | 189 (21.7) | 423 (392, 457) | 0.48 | 24.3 (21.8, 27.1) | 0.002 | 31.6 (28.6, 34.9) | 0.21 | 7.1 (6.4, 7.9) | 0.13 |

| Former (<5 years) | 33 (4.9) | 423 (349, 512) | 0.71 | 27.4 (23.2, 32.2) | 0.31 | 33.0 (26.1, 41.6) | 0.33 | 7.7 (6.6, 8.9) | 0.72 |

| Current (infrequent) | 42 (5.2) | 531 (429, 657) | 0.09 | 36.7 (29.3, 45.9) | 0.08 | 34.2 (27.5, 42.5) | 0.16 | 7.4 (6.3, 8.7) | 0.46 |

| Current (daily) | 161 (24.5) | 548 (517, 581) | 0.0001 | 35.0 (32.1, 38.3) | 0.003 | 37.3 (33.0, 42.1) | 0.007 | 6.5 (5.7, 7.4) | 0.02 |

| β-hexachlorocyclohexane (range) Q1 (<LOD) | 199 (32.3) | 477 (448, 508) | ref | 28.0 (25.7, 30.4) | ref | 35.1 (32.4, 38.0) | ref | 7.1 (6.5, 7.7) | ref |

| Q2 (0.90–6.60 ng/g lipid) | 135 (22.3) | 459 (420, 501) | 0.84 | 29.8 (26.8, 33.3) | 0.30 | 31.8 (28.6, 35.4) | 0.14 | 7.7 (7.1, 8.5) | 0.12 |

| Q3 (6.70–22.50 ng/g lipid) | 277 (32.9) | 471 (433, 513) | 0.99 | 31.8 (29.2, 34.8) | 0.07 | 30.8 (28.1, 33.7) | 0.03 | 7.5 (6.8, 8.3) | 0.41 |

| Q4 (22.56–1200.0 ng/g lipid) | 137 (12.5) | 422 (360, 494) | 0.16 | 30.8 (26.3, 36.1) | 0.30 | 28.5 (24.7, 33.0) | 0.02 | 6.7 (6.1, 7.4) | 0.43 |

| p,p’-DDT (range), Q1 (<LOD) | 345 (52.9) | 468 (441, 497) | ref | 27.4 (25.8, 29.0) | ref | 34.4 (32.6, 36.3) | ref | 7.3 (6.8, 7.9) | ref |

| Q2 (0.9–5.3 ng/g lipid) | 99 (15.1) | 481 (435, 533) | 0.62 | 36.6 (33.5, 40.0) | <0.0001 | 31.5 (28.4, 35.0) | 0.15 | 7.5 (6.6, 8.5) | 0.79 |

| Q3 (5.4–14.9 ng/g lipid) | 202 (24.8) | 450 (410, 493) | 0.47 | 31.5 (28.2, 35.2) | 0.03 | 28.6 (25.4, 32.1) | 0.004 | 7.2 (6.4, 8.0) | 0.75 |

| Q4 (15.0–2280.0 ng/g lipid) | 102 (7.2) | 443 (407, 482) | 0.23 | 32.1 (25.5, 40.5) | 0.19 | 29.3 (24.0, 35.9) | 0.12 | 7.3 (6.5, 8.3) | 0.98 |

| p,p’-DDE (range), Q1 (7.6–168.0 ng/g lipid) | 186 (31.9) | 451 (418, 486) | ref | 29.7 (26.8, 32.9) | ref | 33.4 (31.1, 35.7) | ref | 7.5 (6.9, 8.2) | ref |

| Q2 (169.0–366.0 ng/g lipid) | 188 (29.7) | 472 (440, 507) | 0.33 | 30.3 (28.1, 32.7) | 0.79 | 32.4 (29.7, 35.3) | 0.55 | 7.4 (6.9, 8.0) | 0.89 |

| Q3 (368.0–848.0) ng/g lipid) | 187 (23.9) | 483 (441, 528) | 0.27 | 29.4 (26.7, 32.3) | 0.87 | 30.3 (28.3, 32.3) | 0.07 | 7.5 (6.7, 8.5) | 0.98 |

| Q4 (860–22900 ng/g lipid) | 187 (14.5) | 447 (396, 504) | 0.91 | 30.8 (26.6, 35.5) | 0.71 | 31.6 (27.1, 36.8) | 0.53 | 6.4 (5.8, 7.2) | 0.04 |

| Heptachlor epoxide (range), Q1 (<LOD) | 282 (37.2) | 496 (467, 527) | ref | 28.7 (26.4, 31.2) | ref | 36.2 (34.0, 38.6) | ref | 7.0 (6.6, 7.5) | ref |

| Q2 (1.1–6.0 ng/g lipid) | 117 (17.3) | 481 (441, 524) | 0.50 | 29.6 (26.7, 32.8) | 0.64 | 32.7 (30.0, 35.6) | 0.06 | 7.0 (6.3, 7.7) | 0.93 |

| Q3 (6.1–12.9 ng/g lipid) | 233 (31.9) | 441 (407, 478) | 0.02 | 30.6 (28.2, 33.1) | 0.30 | 29.1 (26.8, 31.5) | <0.0001 | 7.5 (6.9, 8.3) | 0.64 |

| Q4 (13.0–154.0 ng/g lipid) | 116 (13.6) | 415 (367, 468) | 0.01 | 32.7 (30.0, 35.7) | 0.03 | 28.2 (25.2, 31.5) | <0.0001 | 8.1 (6.9, 9.4) | 0.44 |

| Oxychlordane (range), Q1 (<LOD) | 102 (13.3) | 493 (442, 549) | ref | 30.1 (27.1, 33.4) | ref | 37.1 (33.5, 41.2) | ref | 7.7 (6.8, 8.7) | ref |

| Q2 (2.2–9.8 ng/g lipid) | 160 (24.6) | 476 (440, 515) | 0.45 | 28.6 (25.7, 32.0) | 0.48 | 31.9 (29.0, 35.0) | 0.02 | 7.3 (6.6, 8.0) | 0.42 |

| Q3 (9.9–27.4 ng/g lipid) | 323 (47.1) | 450 (424, 477) | 0.11 | 30.1 (28.4, 31.9) | 0.98 | 31.5 (29.6, 33.6) | 0.01 | 7.3 (6.8, 7.7) | 0.41 |

| Q4 (27.5–159.0 ng/g lipid) | 163 (15.0) | 465 (396, 545) | 0.59 | 31.7 (27.5, 36.6) | 0.57 | 30.0 (26.8, 33.5) | 0.008 | 7.2 (5.8, 8.8) | 0.60 |

| trans-nonachlor (range), Q1 (<LOD) | 57 (8.4) | 513 (446, 591) | ref | 31.4 (27.0, 36.4) | ref | 36.9 (32.7, 41.6) | ref | 7.3 (6.2, 8.6) | ref |

| Q2 (3.0–12.8 ng/g lipid) | 171 (24.6) | 462 (426, 501) | 0.13 | 29.3 (25.9, 33.2) | 0.47 | 32.4 (28.9, 36.3) | 0.07 | 7.0 (6.5, 7.6) | 0.64 |

| Q3 (13.0–43.6 ng/g lipid) | 345 (50.9) | 451 (423, 481) | 0.11 | 30.0 (28.3, 31.7) | 0.56 | 31.5 (29.7, 33.5) | 0.04 | 7.5 (7.0, 8.0) | 0.81 |

| Q4 (43.8–460.0 ng/g lipid) | 175 (16.1) | 484 (420, 557) | 0.56 | 30.3 (25.9, 35.3) | 0.76 | 30.9 (27.5, 34.6) | 0.04 | 7.3 (6.1, 8.7) | 0.97 |

| Mirex (range), Q1 (<LOD) | 431 (58.0) | 456 (436, 477) | ref | 28.5 (26.6, 30.5) | ref | 32.7 (30.5, 34.9) | ref | 7.5 (7.1, 8.0) | ref |

| Q2 (1.2–4.30 ng/g lipid) | 76 (11.9) | 430 (357, 518) | 0.54 | 34.4 (29.7, 39.9) | 0.04 | 27.8 (23.7, 32.7) | 0.08 | 7.4 (6.1, 8.9) | 0.85 |

| Q3 (4.40–12.50 ng/g lipid) | 162 (20.9) | 490 (454, 530) | 0.09 | 31.4 (28.8, 34.3) | 0.08 | 31.8 (28.9, 34.9) | 0.59 | 7.2 (6.5, 8.0) | 0.47 |

| Q4 (12.60–2320 ng/g lipid) | 79 (9.2) | 499 (448, 557) | 0.11 | 31.0 (26.0, 37.1) | 0.39 | 34.9 (31.1, 39.1) | 0.32 | 6.2 (5.4, 7.1) | 0.01 |

| Hexachlorobenzene (range), Q1 (<LOD) | 445 (59.9) | 464 (440, 488) | ref | 26.4 (24.9, 28.0) | ref | 32.9 (31.3, 34.5) | ref | 7.4 (7.0, 7.8) | ref |

| Q2 (4.6–11.7 ng/g lipid) | 73 (11.1) | 465 (403, 536) | 0.97 | 38.2 (33.4, 43.8) | <0.0001 | 29.7 (25.5, 34.5) | 0.20 | 8.0 (6.9, 9.1) | 0.32 |

| Q3 (11.8–19.1 ng/g lipid) | 152 (19.2) | 439 (408, 473) | 0.24 | 32.3 (29.3, 35.6) | 0.0008 | 31.0 (27.6, 34.9) | 0.37 | 6.5 (5.8, 7.3) | 0.06 |

| Q4 (19.3–241.0 ng/g lipid) | 78 (9.8) | 515 (419, 633) | 0.32 | 42.3 (36.4, 49.2) | <0.0001 | 32.1 (26.7, 38.6) | 0.80 | 7.9 (6.6, 9.5) | 0.47 |

| Survey year, 1999–2000 | 140 (16.5) | 471 (439, 506) | 0.77 | 26.6 (23.4, 30.3) | 0.0002 | 33.3 (29.9, 37.0) | 0.31 | 7.4 (6.6, 8.3) | 0.71 |

| 2001–2002 | 317 (44.6) | 461 (431, 493) | 0.87 | 26.4 (24.9, 28.1) | <0.0001 | 32.6 (30.9, 34.5) | 0.35 | 7.4 (6.9, 7.9) | 0.68 |

| 2003–2004 | 291 (38.9) | 464 (431, 500) | ref | 36.3 (33.3, 39.6) | ref | 30.9 (28.0, 34.2) | ref | 7.2 (6.6, 7.8) | ref |

GM=geometric mean; CI=confidence interval; nH=non-Hispanic; LOD: limit of detection; Q1: Quartile 1; Q2: Quartile 2; Q3: Quartile 3; Q4: Quartile 4; p-values presented are from 2-sided t-tests from linear models regressing the log transformed hormone concentration on the covariate with adjustment for age.

Table 2.

Weighted geometric mean lipid adjusted pesticide concentration levels among NHANES 1999–2004 male participants, overall and by covariates (n=748).

| β-hexachlorocyclohexane (ng/g lipid) | Hexachlorobenzene (ng/g lipid) | p,p’-DDE (ng/g lipid) | p,p’-DDT (ng/g lipid) | Mirex (ng/g lipid) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GM (95% CI) | p-value | GM (95% CI) | p-value | GM (95% CI) | p-value | GM (95% CI) | p-value | GM (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Overall | 7.1 (6.4, 7.9) | 14.8 (14.0, 15.7) | 287 (252, 326) | 6.6 (5.9, 7.3) | 4.8 (4.3, 5.4) | |||||

| Age in years, 20–39 | 4.4 (3.9, 5.0) | <0.0001 | 14.1 (13.0, 15.3) | 0.002 | 174 (150, 202) | <0.0001 | 5.9 (5.3, 6.6) | 0.0001 | 3.9 (3.5, 4.3) | <0.0001 |

| 40–59 | 8.0 (6.8, 9.4) | <0.0001 | 14.6 (13.2, 16.0) | 0.02 | 342 (285, 409) | <0.0001 | 6.6 (5.4, 8.1) | 0.06 | 5.2 (4.5, 5.9) | 0.005 |

| 60+ | 16.4 (13.8, 19.5) | ref | 17.2 (15.6, 18.9) | ref | 589 (494, 701) | ref | 8.1 (7.2, 9.2) | ref | 6.7 (5.4, 8.5) | ref |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||

| African-American, nH | 5.5 (4.5, 6.6) | 0.0001 | 14.6 (12.8, 16.6) | 0.32 | 273 (204, 366) | 0.001 | 7.2 (6.1, 8.6) | 0.12 | 7.5 (5.2, 10.8) | 0.002 |

| White, nH | 6.6 (5.9, 7.5) | 0.01 | 14.7 (13.7, 15.8) | 0.23 | 250 (218, 287) | <0.0001 | 6.0 (5.3, 6.8) | 0.002 | 4.7 (4.1, 5.3) | 0.15 |

| Hispanic | 9.5 (7.3, 12.3) | ref | 16.6 (13.9, 19.7) | ref | 582 (460, 737) | ref | 9.4 (7.4, 12.0) | ref | 4.1 (3.6, 4.6) | ref |

| Other | 18.1 (10.0, 32.9) | 0.05 | 13.4 (10.3, 17.3) | 0.20 | 428 (262, 701) | 0.25 | 8.5 (5.7, 12.9) | 0.68 | 4.4 (3.2, 6.0) | 0.68 |

| Education, < High school | 8.5 (6.9, 10.4) | 0.28 | 15.6 (13.8, 17.5) | 0.05 | 386 (315, 474) | 0.05 | 7.7 (6.5, 9.1) | 0.04 | 5.9 (4.7, 7.4) | 0.02 |

| High school graduate | 7.0 (5.8, 8.4) | 0.29 | 15.3 (13.6, 17.2) | 0.15 | 262 (216, 319) | 0.49 | 6.2 (5.2, 7.5) | 0.96 | 5.0 (4.0, 6.3) | 0.43 |

| Some college | 5.9 (5.1, 6.9) | 0.01 | 14.9 (13.1, 16.8) | 0.32 | 254 (213, 304) | 0.34 | 6.5 (5.7, 7.4) | 0.60 | 4.3 (3.9, 4.8) | 0.55 |

| ≥ College graduate | 8.2 (6.7, 10.0) | ref | 13.8 (12.8, 14.9) | ref | 292 (230, 370) | ref | 6.2 (5.3, 7.2) | ref | 4.5 (4.0, 5.2) | ref |

| Born in the United States, Yes | 6.2 (5.6, 6.8) | <0.0001 | 14.6 (13.7, 15.6) | 0.28 | 247 (219, 279) | <0.0001 | 5.9 (5.4, 6.3) | <0.0001 | 5.0 (4.4, 5.8) | 0.03 |

| No | 15.5 (11.5, 20.9) | 16.2 (13.7, 19.2) | 636 (494, 819) | 12.2 (9.0, 16.6) | 3.9 (3.3, 4.6) | |||||

| BMI, kg/m2, <25 | 6.5 (5.5, 7.7) | 0.002 | 15.4 (14.2, 16.7) | 0.66 | 300 (252, 357) | 0.62 | 6.7 (5.8, 7.8) | 0.67 | 5.5 (4.8, 6.3) | 0.01 |

| 25 to <30 | 6.4 (5.6, 7.3) | 0.002 | 14.3 (13.3, 15.5) | 0.49 | 259 (222, 302) | 0.11 | 6.2 (5.8, 6.7) | 0.21 | 4.9 (4.3, 5.5) | 0.11 |

| ≥30 | 9.1 (7.5, 11.0) | ref | 15.0 (13.5, 16.7) | ref | 315 (257, 386) | ref | 6.9 (5.7, 8.4) | ref | 4.2 (3.4, 5.1) | ref |

| Triglycerides ≥ 200 mg/dL, Yes | 7.5 (6.0, 9.4) | 0.62 | 12.5 (11.2, 14.0) | 0.0002 | 278 (219, 353) | 0.73 | 6.3 (5.3, 7.4) | 0.38 | 4.2 (3.5, 4.9) | 0.04 |

| No | 7.0 (6.2, 8.0) | 15.6 (14.7, 16.6) | 289 (254, 330) | 6.7 (6.0, 7.4) | 5.0 (4.4, 5.7) | |||||

| Total cholesterol ≥ 200 mg/dL, Yes | 6.7 (6.0, 7.5) | 0.25 | 13.3 (12.2, 14.5) | 0.0002 | 275 (239, 315) | 0.34 | 5.9 (5.4, 6.4) | 0.002 | 4.6 (4.1, 5.1) | 0.06 |

| No | 7.6 (6.4, 9.0) | 16.5 (15.3, 17.7) | 299 (252, 354) | 7.3 (6.3, 8.6) | 5.1 (4.4, 5.8) | |||||

| Diabetes | 15.5 (11.2, 21.5) | <0.0001 | 15.4 (13.7, 17.4) | 0.47 | 537 (396, 728) | <0.0001 | 8.7 (7.2, 10.5) | 0.002 | 7.1 (5.0, 10.0) | 0.01 |

| Non-diabetic | 6.7 (6.0, 7.4) | 14.8 (13.9, 15.7) | 271 (238, 309) | 6.4 (5.8, 7.1) | 4.7 (4.2, 5.2) | |||||

| Smoking status, Never | 6.4 (5.6, 7.3) | ref | 14.4 (13.3, 15.5) | ref | 265 (227, 310) | ref | 6.6 (5.9, 7.4) | ref | 4.3 (3.9, 4.7) | ref |

| Former (5+ years) | 10.3 (8.2, 12.9) | 0.0005 | 16.2 (14.4, 18.2) | 0.09 | 382 (311, 468) | 0.005 | 6.7 (6.0, 7.5) | 0.82 | 5.8 (4.7, 7.2) | 0.003 |

| Former (<5 years) | 6.5 (4.7, 8.8) | 0.94 | 17.1 (13.5, 21.6) | 0.17 | 240 (162, 355) | 0.61 | 6.9 (5.5, 8.7) | 0.67 | 4.7 (3.9, 5.6) | 0.33 |

| Current (infrequent) | 6.4 (5.3, 7.8) | 0.95 | 13.4 (11.0, 16.3) | 0.46 | 254 (194, 332) | 0.78 | 6.5 (4.9, 8.6) | 0.90 | 4.2 (3.3, 5.2) | 0.81 |

| Current (daily) | 6.6 (5.4, 8.0) | 0.77 | 14.4 (13.1, 15.8) | 0.99 | 273 (213, 348) | 0.82 | 6.4 (5.0, 8.1) | 0.74 | 5.2 (4.1, 6.6) | 0.08 |

| Survey year, 1999–2000 | 6.8 (5.4, 8.6) | 0.78 | 39.0 (37.2, 40.9) | <0.0001 | 350 (250, 489) | 0.09 | 9.5 (8.2, 11.1) | <0.0001 | 5.5 (5.0, 6.0) | <0.0001 |

| 2001–2002 | 8.2 (7.1, 9.6) | 0.04 | 10.3 (9.9, 10.8) | <0.0001 | 303 (258, 356) | 0.13 | 7.3 (6.8, 7.7) | 0.005 | 5.9 (4.8, 7.4) | 0.0003 |

| 2003–2004 | 6.2 (5.2, 7.3) | ref | 14.9 (14.1, 15.7) | ref | 247 (200, 306) | ref | 5.0 (4.0, 6.2) | ref | 3.6 (3.2, 4.1) | ref |

GM=geometric mean; CI=confidence interval; nH=non-Hispanic; Q1: Quartile 1; Q2: Quartile 2; Q3: Quartile 3; Q4: Quartile 4; p-values presented are from 2-sided t-tests from linear models regressing the log transformed lipid adjusted pesticide concentration on the covariate

Estradiol

Table 3 presents the adjusted estimates for the association of serum quartiles of pesticides with sex steroid hormone levels. Although differences did not reach the level of statistical significance, the estimated geometric mean estradiol level for participants in the highest β-hexachlorocyclohexane exposure quartile was Q4 GM=30.3 pg/mL (95% CI 26.5, 34.6) compared with 26.7 pg/mL ((95% CI 24.5, 29.0) p=0.14) for those in the lowest exposure quartile. The estimated geometric mean estradiol level for participants in the highest HCB exposure quartile was 43.2 pg/mL (95% CI 36.5, 51.1) compared with 25.6 pg/mL ((95% CI 24.1, 27.3) p<0.0001) for those in the lowest exposure quartile. We observed a positive association with p-p’-DDT and estradiol levels (p for trend 0.05). Similar associations were observed for β-hexachlorocyclohexane, HCB, and p-p’-DDT with free estradiol. We did not observe effect modification for any measure of estradiol.

Table 3.

Multivariable adjusteda associations between categorized levels of lipid adjusted pesticide exposures and hormones levels in male NHANES 1999–2004 participants (n=748).

| Serum pesticide concentrations (ng/g lipid) | Testosterone (ng/dL) | Estradiol (pg/mL) | Free estradiol (pg/mL) | Testosterone: Estradiol Ratio (pg/mL) |

Androstanediol glucuronide (ng/mL) |

SHBG (nmol/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GM (95% CI) | GM (95% CI) | GM (95% CI) | GM (95% CI) | GM (95% CI) | GM (95% CI) | |

| β-hexachlorocyclohexane | ||||||

| Q1 (ref) | 444 (415, 475) | 26.7 (24.5, 29.0) | 0.49 (0.44, 0.53) | 166.3 (154.1, 179.5) | 7.2 (6.5, 7.8) | 33.9 (31.5, 36.5) |

| Q2 | 445 (412, 481) | 28.3 (25.9, 31.0) | 0.52 (0.47, 0.58) | 157.1 (143.5, 171.9) | 7.5 (6.9, 8.2) | 33.2 (30.0, 36.6) |

| Q3 | 477 (440, 517) | 29.7 (27.5, 32.0) | 0.54 (0.50, 0.58) | 160.7 (148.2, 174.1) | 7.4 (6.8, 8.1) | 32.9 (30.7, 35.3) |

| Q4 | 447 (394, 507) | 30.3 (26.5, 34.6) | 0.57 (0.48, 0.66) | 147.5 (128.7, 169.0) | 6.7 (6.1, 7.4) | 31.0 (27.1, 35.6) |

| p for trend | 0.53 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.23 | 0.81 | 0.37 |

| Hexachlorobenzene | ||||||

| Q1 (ref) | 440 (417, 466) | 25.6 (24.1, 27.3) | 0.47 (0.44, 0.51) | 172.0 (161.4, 183.3) | 7.3 (6.8, 7.8) | 33.1 (31.2, 35.0) |

| Q2 | 484 (423, 554) | 39.8 (33.4, 47.4)b | 0.72 (0.60, 0.88)b | 121.6 (101.3, 145.9)b | 7.7 (6.6, 9.1) | 31.3 (27.0, 36.2) |

| Q3 | 462 (419, 509) | 33.0 (28.8, 37.8)b | 0.60 (0.51, 0.70)b | 139.9 (121.6, 160.9)b | 6.5 (5.7, 7.5) | 32.4 (28.5, 36.8) |

| Q4 | 557 (452, 688)b | 43.2 (36.5, 51.1)b | 0.77 (0.64, 0.93)b | 129.2 (110.8, 150.6)b | 8.0 (6.6, 9.7) | 33.9 (28.7, 40.1) |

| p for trend | 0.11 | <0.0001 | 0.002 | 0.03 | 0.93 | 0.69 |

| Heptachlor epoxide | ||||||

| Q1 (ref) | 446 (420, 474) | 28.6 (26.4, 30.9) | 0.52 (0.48, 0.57) | 156.1 (144.4, 168.9) | 7.3 (6.8, 7.8) | 33.1 (30.9, 35.5) |

| Q2 | 464 (418, 514) | 26.7 (23.5, 30.3) | 0.48 (0.42, 0.55) | 173.9 (155.0, 195.0) | 6.7 (6.0, 7.5) | 35.1 (32.3, 38.2) |

| Q3 | 447 (416, 480) | 29.7 (27.9, 31.6) | 0.55 (0.52, 0.59) | 150.6 (142.1, 159.5) | 7.3 (6.8, 8.0) | 31.1 (29.3, 33.0) |

| Q4 | 476 (420, 540) | 31.4 (28.8, 34.2) | 0.58 (0.52, 0.64) | 151.9 (136.8, 168.6) | 7.8 (6.7, 9.0) | 33.3 (29.7, 37.3) |

| p for trend | 0.55 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.33 | 0.41 | 0.40 |

| Oxychlordane | ||||||

| Q1 (ref) | 446 (404, 493) | 30.1 (27.5, 33.0) | 0.54 (0.49, 0.60) | 148.2 (137.3, 160.0) | 7.7 (6.9, 8.7) | 34.8 (32.1, 37.6) |

| Q2 | 453 (416, 493) | 26.9 (24.2, 29.8) | 0.49 (0.44, 0.55) | 168.4 (153.1, 185.1)b | 7.3 (6.7, 8.1) | 32.1 (29.1, 35.4) |

| Q3 | 445 (423, 468) | 28.9 (27.4, 30.4) | 0.53 (0.50, 0.57) | 154.0 (143.4, 165.4) | 7.2 (6.8, 7.6) | 32.9 (31.1, 34.9) |

| Q4 | 485 (411, 572) | 31.3 (27.5, 35.7) | 0.58 (0.51, 0.68) | 154.8 (137.1, 174.7) | 7.1 (5.8, 8.6) | 31.7 (29.2, 34.5) |

| p for trend | 0.64 | 0.48 | 0.32 | 0.94 | 0.47 | 0.36 |

| p,p’-DDT | ||||||

| Q1 (ref) | 439 (416, 462) | 27.3 (25.9, 28.7) | 0.50 (0.47, 0.53) | 160.7 (151.4, 170.5) | 7.3 (6.9, 7.8) | 33.9 (32.3, 35.5) |

| Q2 | 501 (454, 552)b | 32.2 (28.3, 36.7)b | 0.59 (0.50, 0.68) | 155.3 (137.0, 176.1) | 7.3 (6.2, 8.5) | 34.3 (29.6, 39.7) |

| Q3 | 472 (433, 515) | 30.3 (27.5, 33.4) | 0.56 (0.51, 0.62)b | 155.9 (142.1, 170.9) | 7.1 (6.4, 7.8) | 30.9 (28.1, 34.0) |

| Q4 | 429 (391, 471) | 31.6 (25.9, 38.5) | 0.60 (0.48, 0.76) | 135.9 (116.3, 158.7) | 7.3 (6.4, 8.4) | 29.2 (23.8, 35.9) |

| p for trend | 0.46 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.68 | 0.07 |

| p,p’-DDE | ||||||

| Q1 (ref) | 434 (403, 468) | 27.2 (24.8, 29.8) | 0.49 (0.44, 0.54) | 159.7 (145.9, 174.8) | 7.5 (6.9, 8.3) | 34.4 (32.4, 36.6) |

| Q2 | 464 (434, 496) | 28.6 (26.5, 31.0) | 0.52 (0.47, 0.56) | 162.0 (150.0, 174.9) | 7.3 (6.8, 7.9) | 34.0 (31.6, 36.7) |

| Q3 | 478 (433, 529) | 28.9 (26.3, 31.6) | 0.54 (0.49, 0.60) | 165.8 (152.7, 180.0) | 7.4 (6.5, 8.3) | 31.0 (29.3, 32.9)b |

| Q4 | 443 (397, 494) | 29.9 (26.1, 34.1) | 0.55 (0.47, 0.65) | 148.3 (129.7, 169.4) | 6.5 (5.9, 7.3) | 31.9 (27.7, 36.8) |

| p for trend | 0.53 | 0.28 | 0.18 | 0.64 | 0.21 | 0.19 |

| trans-nonachlor | ||||||

| Q1 (ref) | 465 (413, 523) | 32.0 (27.9, 36.6) | 0.59 (0.51, 0.67) | 145.2 (132.0, 159.7) | 7.5 (6.5, 8.6) | 34.5 (31.5, 37.8) |

| Q2 | 449 (410, 492) | 26.5 (23.7, 29.6)b | 0.48 (0.42, 0.54)b | 169.4 (154.9, 185.4)b | 6.9 (6.4, 7.4) | 33.6 (30.3, 37.2) |

| Q3 | 451 (427, 476) | 28.7 (27.4, 30.0) | 0.52 (0.50, 0.56) | 157.2 (147.0, 168.1) | 7.3 (6.9, 7.8) | 33.2 (31.4, 35.1) |

| Q4 | 472 (408, 547) | 28.6 (25.1, 32.6) | 0.53 (0.46, 0.62) | 165.1 (146.8, 185.7) | 7.4 (6.3, 8.7) | 31.2 (28.8, 33.8) |

| p for trend | 0.84 | 0.75 | 0.98 | 0.54 | 0.75 | 0.25 |

| Mirex | ||||||

| Q1 (ref) | 448 (431, 466) | 28.1 (26.5, 29.8) | 0.51 (0.47, 0.55) | 159.4 (150.2, 169.2) | 7.5 (7.1, 7.9) | 33.6 (31.7, 35.6) |

| Q2 | 476 (396, 572) | 30.5 (25.6, 36.3) | 0.55 (0.45, 0.67) | 156.0 (127.5, 190.8) | 6.8 (5.8, 8.1) | 32.8 (27.4, 39.3) |

| Q3 | 460 (423, 501) | 28.7 (26.1, 31.6) | 0.54 (0.49, 0.60) | 160.3 (147.5, 174.2) | 7.2 (6.4, 8.0) | 31.3 (28.5, 34.3) |

| Q4 | 471 (423, 524) | 29.1 (24.8, 34.1) | 0.53 (0.44, 0.64) | 161.9 (131.0, 200.0) | 6.4 (5.7, 7.2)b | 33.0 (29.9, 36.3) |

| p for trend | 0.42 | 0.66 | 0.44 | 0.86 | 0.07 | 0.32 |

Model adjusts for age (continuous), body mass index (continuous), race (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic African-American, Hispanic, or other), education level (less than high school, high school grad, some college or more), serum lipids (continuous), self-reported smoking history (never, 5+ years since last cigarette, <5 years since last cigarette, infrequent current smoker, daily smoker), and survey cycle

Statistically significant (p<0.05); Q1: Quartile 1; Q2: Quartile 2; Q3: Quartile 3; Q4: Quartile 4;

Testosterone

Few associations were observed between pesticide exposures and testosterone measures. The estimated geometric mean testosterone level for participants in the highest HCB exposure quartile was 557 ng/dL (95% CI 452, 688) compared with 440 ng/dL ((95% CI 417, 466) p=0.04) for those in the lowest exposure quartile. Males with detectable p,p’-DDT levels had higher average free testosterone levels compared to those with undetectable p,p’-DDT levels (Q1 (non-detects) GM=8.6 ng/dL (95% CI 8.1, 9.0); Q2 GM=9.7 ng/dL (95% CI 8.6, 11.0); Q3 GM=8.6 ng/dL (95% CI 8.9, 10.6); Q4 GM=9.0 ng/dL (95% CI 7.8, 10.4); data not shown). We did not observe associations between any of the other measured pesticides and testosterone or free testosterone, nor did we observe interactions with age, BMI, or diabetes status.

Ratio of testosterone to estradiol

When the ratio of testosterone to estradiol was modeled, we observed an inverse association with HCB (p for trend=0.03). Though we did not observe a significant trend when assessing the association between concentration of p-p’-DDT with the ratio of testosterone to estradiol (p for trend =0.16), the geometric mean ratio for Q4 was lower compared to Q1 (Q4 GM= 135.9 (95% CI 116.3, 158.7) versus Q1 GM= 160.7 (95% CI 151.4, 170.5), p=0.06). There were no significant interactions with age, BMI, or diabetes status.

Androstanediol glucuronide

The estimated geometric mean androstanediol glucuronide level for participants in the highest mirex exposure quartile was 6.4 ng/mL (95% CI 5.7, 7.2) which was lower than the estimated geometric mean level among those in the lowest (non-detect) quartile (7.5 ng/mL (95% CI 7.1, 7.9) p=0.02). No other overall associations were observed when modeling log transformed androstanediol glucuronide, nor were significant interactions with age, BMI, or diabetes status.

Sex hormone binding globulin

In full models, the only pesticide that was associated with SHBG was p,p’-DDT (inverse association; p for trend 0.07). When cross-product terms were added to the SHBG models, there were significant interactions among heptachlor epoxide and BMI (p-interaction =0.03) and among p,p’-DDE and diabetes status (p-interaction=0.02). Results from stratified models are shown in Supplemental Table 2. There was an inverse trend among males in the lowest BMI category (p for trend=0.01), suggesting that among males with BMI < 25 those with higher concentrations of heptachlor epoxide had lower levels of SHBG relative to those in the lower exposure categories. Despite the significant interaction term between p,p’-DDE and diabetes, no associations of p,p’-DDE and SHBG were observed in either group. No other associations or interactions were observed.

Principal component analysis

When we examined the associations among the pesticide concentrations, the correlations (Table 4) appeared to be sufficient to apply PCA methods. Many of the pesticides were highly correlated, with the highest correlation coefficient of 0.88 observed between serum trans-nonachlor and its metabolite oxychlordane. During the PCA, eight components were estimated, and we retained three principal components with eigenvalues greater than 0.90. These three components cumulatively explained 75% of the total variance. After applying an orthogonal varimax rotation, the first principal component was comprised of oxychlordane,trans-nonachlor, heptachlor epoxide, and mirex. The second component consisted of β-hexachlorocyclohexane, p,p’-DDE, and p,p’-DDT. The third component only contained HCB. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was 0.77. Results from linear regression models using the principal component scores are shown in Table 5. Co-exposures to oxychlordane, trans-nonachlor, heptachlor epoxide, and mirex (factor 1) were not associated with any hormone parameters. The β-hexachlorocyclohexane, DDT, and DDE factor was inversely associated with the ratio of testosterone to estradiol (p for trend=0.10) and SHBG (p for trend= 0.08). Exposure to HCB was positively associated with total and free estradiol (p for trend <0.0001 and <0.0001, respectively) and inversely associated with the ratio of testosterone to estradiol (p for trend=0.001), independent of the other co-exposures.

Table 4.

Pearson correlation coefficients of lipid-adjusted log transformed pesticide concentrations (ng/g lipid)

| β-hexachlorocyclohexane | Hexachlorobenzene | Heptachlor epoxide | Oxychlordane | p,p’-DDT | p,p’-DDE | trans-nonachlor | Mirex | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

β-hexachlorocyclohexane |

1 | |||||||

|

Hexachlorobenzene |

0.12c | 1 | ||||||

|

Heptachlor epoxide |

0.49a | 0.18a | 1 | |||||

|

Oxychlordane |

0.52a | 0.14a | 0.65a | 1 | ||||

|

p,p’-DDT |

0.52a | 0.28a | 0.28a | 0.22c | 1 | |||

|

p,p’-DDE |

0.67a | 0.20a | 0.36a | 0.48a | 0.64a | 1 | ||

|

trans-nonachlor |

0.48a | 0.11c | 0.64a | 0.88a | 0.18c | 0.48a | 1 | |

|

Mirex |

0.22a | 0.07 | 0.23a | 0.35a | 0.18c | 0.20a | 0.36a | 1 |

Statistically significant (p<0.0001);

Statistically significant (p≤0.001);

Statistically significant (p≤0.05);

Table 5.

Multivariable adjusteda associations between categorized levels of lipid adjusted pesticide (ng/g lipid) exposure factors and hormone levels in male NHANES 1999–2004 participants (n=748).

| Factor score combinations of serum pesticide concentrations | Testosterone (ng/dL) | Free testosterone (ng/dL) | Estradiol (pg/mL) | Free estradiol (pg/mL) | Testosterone: Estradiol Ratio (pg/mL) | SHBG (nmol/L) | Androstanediol glucuronide (ng/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GM (95% CI) | GM (95% CI) | GM (95% CI) | GM (95% CI) | GM (95% CI) | GM (95% CI) | GM (95% CI) | |

| Factor 1: Oxychlordane, trans-nonachlor, Heptachlor epoxide, Mirex | |||||||

| Q1 (ref) | 446 (403, 492) | 9.0 (8.1, 9.9) | 30.3 (27.3, 33.7) | 0.56 (0.50, 0.63) | 146.9 (136.5, 158.1) | 31.4 (28.7, 34.3) | 7.03 (6.36, 7.76) |

| Q2 | 465 (432, 502) | 9.4 (8.7, 10.1) | 29.8 (27.2, 32.7) | 0.55 (0.50, 0.61) | 156.0 (142.0, 171.3) | 32.0 (29.2, 35.1) | 7.08 (6.55, 7.64) |

| Q3 | 456 (426, 489) | 9.1 (8.5, 9.7) | 29.2 (26.9, 31.7) | 0.54 (0.49, 0.59) | 156.3 (143.5, 170.1) | 32.8 (30.3, 35.6) | 7.71 (7.24, 8.21) |

| Q4 | 466 (417, 521) | 9.5 (8.4, 10.7) | 29.3 (26.2, 32.7) | 0.54 (0.48, 0.62) | 159.1 (142.2, 178.0) | 32.3 (29.9, 34.9) | 7.33 (6.48, 8.28) |

| p for trend | 0.62 | 0.56 | 0.69 | 0.78 | 0.35 | 0.67 | 0.57 |

| Factor 2: β-HCH, DDT, & DDE | |||||||

| Q1 (ref) | 454 (418, 493) | 8.8 (8.1, 9.5) | 28.3 (25.3, 31.6) | 0.51 (0.46, 0.57) | 160.7 (146.9, 175.8) | 34.8 (32.3, 37.4) | 7.67 (6.95, 8.47) |

| Q2 | 464 (429, 501) | 9.4 (8.7, 10.1) | 29.2 (26.6, 32.1) | 0.54 (0.49, 0.60) | 158.7 (146.7, 171.7) | 32.2 (29.7, 34.8) | 7.31 (6.69, 8.00) |

| Q3 | 468 (425, 515) | 9.4 (8.5, 10.3) | 29.9 (27.4, 32.6) | 0.55 (0.50, 0.60) | 156.5 (144.5, 169.5) | 32.3 (29.8, 34.9) | 6.96 (6.37, 7.61) |

| Q4 | 448 (415, 483) | 9.4 (8.6, 10.2) | 31.4 (28.5, 34.7) | 0.60 (0.53, 0.67) | 142.5 (130.5, 155.6) | 29.4 (25.7, 33.6) | 7.19 (6.53, 7.91) |

| p for trend | 0.86 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.24 |

| Factor 3: Hexachlorobenzene | |||||||

| Q1 (ref) | 439 (408, 472) | 8.9 (8.2, 9.7) | 26.6 (24.6, 28.7) | 0.50 (0.45, 0.54) | 165.3 (153.9, 177.5) | 31.9 (30.1, 33.7) | 7.36 (6.72, 8.06) |

| Q2 | 456 (428, 486) | 8.9 (8.5, 9.3) | 27.2 (25.2, 29.4) | 0.49 (0.45, 0.54) | 167.5 (153.2, 183.1) | 33.9 (31.0, 37.0) | 7.35 (6.80, 7.95) |

| Q3 | 450 (415, 487) | 9.4 (8.7, 10.1) | 30.4 (28.3, 32.7)b | 0.57 (0.53, 0.62)b | 147.8 (134.8, 162.0) | 30.5 (28.2, 33.1) | 6.89 (6.26, 7.58) |

| Q4 | 490 (429, 560) | 9.8 (8.5, 11.3) | 35.3 (31.7, 39.4)b | 0.65 (0.57, 0.73)b | 138.9 (126.5, 152.5)b | 32.3 (29.7, 35.2) | 7.54 (6.68, 8.50) |

| p for trend | 0.17 | 0.18 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.001 | 0.60 | 0.98 |

All principal components included in the same model, plus adjustment for age (continuous), body mass index (continuous), race (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic African-American, Hispanic, or other), education level (less than high school, high school grad, some college or more), serum lipids (continuous), self-reported smoking history (never, 5+ years since last cigarette, <5 years since last cigarette, infrequent current smoker, daily smoker), and survey cycle

Statistically significant (p<0.05); Q1: Quartile 1; Q2: Quartile 2; Q3: Quartile 3; Q4: Quartile 4; β-HCH: β-hexachlorocyclohexane

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the associations between organochlorine pesticides measured in serum and sex hormone levels in adult males. Organochlorine pesticides were detectable in most males in our sample, many of whom had high exposure levels to multiple organochlorine pesticides. We observed associations primarily among HCB and measures of estrogen not only in individual models, but in models adjusted for other pesticide exposures. High concentrations of serum HCB were positively associated with total and free estradiol and inversely associated with the ratio of testosterone to estradiol, independent of the other pesticide co-exposures. In individual models, we observed positive associations among DDT and measures of estrogen, and an inverse association between DDT and SHBG. We observed a suggestive positive association between β-hexachlorocyclohexane levels and estradiol. After adjusting for other co-exposures using principal components analysis methods, the β-hexachlorocyclohexane, DDT, and DDE factor was not strongly associated with any outcome.

Reports that evaluate the association between organochlorine pesticide levels and objectively measured hormones levels in males in the general population are limited. In contrast with our study, HCB was not significantly related to SHBG or estradiol in a sample of males presenting to an infertility clinic (Ferguson, Hauser et al. 2012), but was positively associated with SHBG and free androgen index in males of reproductive age (mean age 29 years) using data from multiple combined cohorts (Specht, Bonde et al. 2015). Consistent with the findings in the current study, most other studies in males have not found HCB to be related to testosterone (Hagmar, Bjork et al. 2001, Goncharov, Rej et al. 2009, Ferguson, Hauser et al. 2012, Freire, Koifman et al. 2014). In non-human studies, effects of HCB on endogenous hormones vary by sex, dose, and species under study. In male rats, there is evidence that at low levels HCB enhances androgen action, but that at high levels it decreases androgenicity (Ralph, Orgebin-Crist et al. 2003).

Interference with normal physiological hormone actions could take place via interaction with the hormone receptor or serum binding proteins, inhibition of enzymes that synthesize hormones, and/or induction of enzymes that metabolize hormones. The mechanism by which HCB could increase estradiol levels is largely unknown. Based on the steroidogenic cascade, the increased serum estradiol levels observed among males with the highest measured HCB concentrations should be coupled with reduced testosterone levels if the substance acting to increase estradiol is up-regulating aromatase, which converts androgens to estrogens. However, the aromatase-driven conversion of androgen to estrogen may utilize a quantitatively small amount of androgen relative to the resulting amount of estrogen (Blakemore and Naftolin 2016). This may explain why we did not observe an association with testosterone despite the observed positive associations with estrogen. The effects of HCB exposure have been compared to those of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD), in that HCB binds to the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) with an affinity approximately 10,000 times lower than that of TCDD (Hahn, Goldstein et al. 1989, Kafafi, Afeefy et al. 1993), in the same range as mono-ortho-PCBs 105, 118, and 156 (Hahn, Goldstein et al. 1989, van Birgelen 1998). Binding of HCB to the AhR could interfere with steroid hormone regulated responses, which could be relevant to the associations we observed. The increased levels of estradiol observed with increasing HCB concentration could also be the result of inhibition of the enzymes that metabolize estradiol through conjugation. This would be consistent with prior studies showing that different types of persistent pollutants may inhibit estradiol sulfation (Kester, Bulduk et al. 2000, Kester, Bulduk et al. 2002, Parker, Squirewell et al. 2018).

Relationships of DDT and its metabolite DDE with endogenous hormones in males have been variable. Consistent with the current study, previous studies have, in general, not found that DDE is significantly related to testosterone (Hagmar, Bjork et al. 2001, Persky, Turyk et al. 2001, Martin, Harlow et al. 2002, Cocco, Loviselli et al. 2004, Asawasinsopon, Prapamontol et al. 2006, Turyk, Anderson et al. 2006, Goncharov, Rej et al. 2009, Langer, Kocan et al. 2010, Haugen, Tefre et al. 2011, Blanco-Munoz, Lacasana et al. 2012, Ferguson, Hauser et al. 2012, Emeville, Giton et al. 2013, Freire, Koifman et al. 2014). One study of males living in a highly contaminated rural area observed an inverse association of testosterone with o,p’ DDT (Freire, Koifman et al. 2014). A cross-sectional study of 50 South African malaria control workers observed positive associations of p,p’-DDT with both estradiol and testosterone, but no association with p,p’-DDE (Dalvie, Myers et al. 2004). In a study of Inuit and three European cohorts, p,p’ DDE was positively associated with SHBG among males from Kharkiv, Ukraine, but not in the other sites and positive associations of DDE with free testosterone were seen in Kharkiv and Greenland but not in the other sites (Giwercman, Rignell-Hydbom et al. 2006). In a South African population with high DDE exposure, positive associations were found with testosterone and free testosterone, as well as with estradiol (Bornman, Delport et al. 2018). In contrast, no associations of DDE with estradiol were seen in populations of Mexican flower growers (Blanco-Munoz, Lacasana et al. 2012) nor in a heavily exposed population in South Africa (Bornman, Delport et al. 2018). In a cohort of Great Lakes anglers, DDE was not associated with SHBG, nor with SHBG bound testosterone (Persky, Turyk et al. 2001, Turyk, Anderson et al. 2006). In a subgroup of males from the Great Lakes cohort, DDE was inversely associated with estrone sulfate (Turyk, Anderson et al. 2006) but the association was not observed in the larger cohort (Persky, Turyk et al. 2001); estradiol was not measured in these studies.

There is limited data on the effects of other persistent organochlorine pesticides on endogenous hormones. Testosterone was inversely associated with β-hexachlorocyclohexane in two studies, but the relationship was not significant among those occupationally exposed (Tomczak, Baumann et al. 1981) and was only of marginal significance among males living in a contaminated rural area with high levels of exposure (Freire, Koifman et al. 2014). Neither serum concentrations of trans-nonachlor nor mirex were found to be related to testosterone in a previous studies of adult males from a highly exposed rural area in Brazil (Freire, Koifman et al. 2014).

In our study, we did not observe strong evidence of effect modification by age, BMI, or diabetes status for any of the associations that we evaluated. Of all the associations we evaluated, we observed one inverse association of heptachlor epoxide and SHBG among males with the lowest BMI (<25 kg/m2), and no associations among males in the 25–29.9 or ≥30 BMI categories. Although the cross-product term for p,p’-DDE and diabetes was significant in the model for SHBG, stratum-specific estimates were not substantively different and trends were null. It is possible that the statistically significant cross-product terms observed were due to chance, and that our ability to detect effect modification was underpowered. To our knowledge, subgroup analyses to identify effect modification for the associations of organochlorine pesticides with sex hormones have not been conducted in other studies with which we can make comparisons.

The associations observed may be relevant to understanding the pathogenesis of selected chronic diseases. Steroid hormones may play a role in the disease pathway connecting persistent pollutants to health outcomes such as diabetes, kidney disease, and cancer. In our study, we found particular organochlorine pesticide concentrations to be positively associated with estradiol and inversely associated with SHBG. Estrogen actions are involved in insulin sensitivity and glucose homeostasis (Mauvais-Jarvis, Clegg et al. 2013). In studies of males estradiol has been related positively and SHBG negatively to diabetes (Kim and Halter 2014, Mather, Kim et al. 2015) and higher levels of SHBG have been associated with reduced risk for low estimated glomerular filtration rate (Kim, Ricardo et al. 2019).

Although many of the organochlorine pesticides studied are now banned from use, recent studies have objectively measured organochlorine pesticide concentrations among adults and observed detectable exposure levels (Jakszyn, Goni et al. 2009, Azandjeme, Delisle et al. 2014, Freire, Koifman et al. 2014, Saoudi, Frery et al. 2014). Our findings may be especially relevant in areas where high concentrations of these pesticides were used, in addition to present-day occupational settings such as those where HCB is produced as a byproduct during the manufacture of solvents and pesticides, pulp and paper production, and metal smelting.

There are several limitations in our study. The NHANES provides cross-sectional data, and only one serum sample was taken to measure both the pesticide and hormone levels. We are unable to determine when the body burden of the measured pesticides was acquired, limiting our ability to tailor intervention strategies to limit or prevent exposure. Only 40.1% of males in our study sample had detectable levels of HCB, suggesting that the observed associations with this pesticide should be interpreted with caution and attempts should be made to replicate these findings in other available datasets. Despite an overall large sample size, we may have had limited power to detect effect modification and precisely estimate stratum specific measures of association. It is possible that exposure to other unmeasured pollutants correlated to the pesticides under study could explain the associations we observed in this study. Residual confounding may also be present due to imperfect methods for adjusting for serum lipids. Although our sample is representative of the U.S. population, subpopulations who are highly exposed, such as those with high occupational exposures or that live in areas of high previous exposure, may be underrepresented. Despite these limitations this study is strengthened by the relatively large, nationally representative sample with a variety of potential confounders and objectively measured organochlorine pesticide (exposure) and hormone (outcomes) levels.

Conclusion

In summary, our findings indicate that exposure to organochlorine pesticides, particularly HCB and DDT, may be positively associated with estradiol levels among adult males in the United States. If substantiated, these findings may provide insights into the mechanism and pathology of chronic diseases known or suspected to be associated with organochlorine pesticide exposure.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Participant flow diagram showing sample exclusions and final numbers for statistical analysis.

Acknowledgements

Funding from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, grant P30ES027792 Chicago Center for Health and Environment (CACHET). Jessica Madrigal is a trainee supported by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) fellowship under grant number T42OH008672. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or NIOSH. The authors do not have any competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Asawasinsopon R, Prapamontol T, Prakobvitayakit O, Vaneesorn Y, Mangklabruks A and Hock B. (2006). “Plasma levels of DDT and their association with reproductive hormones in adult men from northern Thailand.” Sci Total Environ 355(1–3): 98–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azandjeme CS, Delisle H, Fayomi B, Ayotte P, Djrolo F, Houinato D and Bouchard M. (2014). “High serum organochlorine pesticide concentrations in diabetics of a cotton producing area of the Benin Republic (West Africa).” Environ Int 69: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belgorosky A, Escobar ME and Rivarola MA (1987). “Validity of the calculation of non-sex hormone-binding globulin-bound estradiol from total testosterone, total estradiol and sex hormone-binding globulin concentrations in human serum.” J Steroid Biochem 28(4): 429–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernert JT, Turner WE, Patterson DG Jr. and Needham LL (2007). “Calculation of serum “total lipid” concentrations for the adjustment of persistent organohalogen toxicant measurements in human samples.” Chemosphere 68(5): 824–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore J and Naftolin F. (2016). “Aromatase: Contributions to Physiology and Disease in Women and Men.” Physiology (Bethesda) 31(4): 258–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Munoz J, Lacasana M, Aguilar-Garduno C, Rodriguez-Barranco M, Bassol S, Cebrian ME, Lopez-Flores I and Ruiz-Perez I. (2012). “Effect of exposure to p,p’-DDE on male hormone profile in Mexican flower growers.” Occup Environ Med 69(1): 5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornman M, Delport R, Farias P, Aneck-Hahn N, Patrick S, Millar RP and de Jager C. (2018). “Alterations in male reproductive hormones in relation to environmental DDT exposure.” Environ Int 113: 281–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). (2018). “National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Questionnaire.”, 2019, from https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/ContinuousNhanes/documents.aspx?BeginYear=1999.

- Cocco P, Loviselli A, Fadda D, Ibba A, Melis M, Oppo A, Serra S, Taberlet A, Tocco M and Flore C. (2004). “Serum sex hormones in men occupationally exposed to dichloro-diphenyl-trichloro ethane (DDT) as young adults.” 182(3): 391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocco P, Loviselli A, Fadda D, Ibba A, Melis M, Oppo A, Serra S, Taberlet A, Tocco MG and Flore C. (2004). “Serum sex hormones in men occupationally exposed to dichloro-diphenyl-trichloro ethane (DDT) as young adults.” J Endocrinol 182(3): 391–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalvie MA, Myers JE, Thompson M. Lou, Dyer S, Robins TG, Omar S, Riebow J, Molekwa J, Kruger P and Millar R. (2004). “The hormonal effects of long-term DDT exposure on malaria vector-control workers in Limpopo Province, South Africa.” Environ Res 96(1): 9–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emeville E, Giton F, Giusti A, Oliva A, Fiet J, Thome JP, Blanchet P and Multigner L. (2013). “Persistent organochlorine pollutants with endocrine activity and blood steroid hormone levels in middle-aged men.” PLoS One 8(6): e66460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson KK, Hauser R, Altshul L and Meeker JD (2012). “Serum concentrations of p, p’-DDE, HCB, PCBs and reproductive hormones among men of reproductive age.” Reprod Toxicol 34(3): 429–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire C, Koifman RJ, Sarcinelli PN, Rosa AC, Clapauch R and Koifman S. (2014). “Association between serum levels of organochlorine pesticides and sex hormones in adults living in a heavily contaminated area in Brazil.” Int J Hyg Environ Health 217(2–3): 370–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giwercman AH, Rignell-Hydbom A, Toft G, Rylander L, Hagmar L, Lindh C, Pedersen HS, Ludwicki JK, Lesovoy V, Shvets M, Spano M, Manicardi GC, Bizzaro D, Bonefeld-Jorgensen EC and Bonde JP (2006). “Reproductive hormone levels in men exposed to persistent organohalogen pollutants: a study of inuit and three European cohorts.” Environ Health Perspect 114(9): 1348–1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncharov A, Rej R, Negoita S, Schymura M, Santiago-Rivera A, Morse G and Carpenter DO (2009). “Lower serum testosterone associated with elevated polychlorinated biphenyl concentrations in Native American men.” Environ Health Perspect 117(9): 1454–1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gore AC, Chappell VA, Fenton SE, Flaws JA, Nadal A, Prins GS, Toppari J and Zoeller RT (2015). “EDC-2: The Endocrine Society’s Second Scientific Statement on Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals.” Endocr Rev 36(6): E1–e150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagmar L, Bjork J, Sjodin A, Bergman A and Erfurth EM (2001). “Plasma levels of persistent organohalogens and hormone levels in adult male humans.” Arch Environ Health 56(2): 138–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn ME, Goldstein JA, Linko P and Gasiewicz TA (1989). “Interaction of hexachlorobenzene with the receptor for 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin in vitro and in vivo. Evidence that hexachlorobenzene is a weak Ah receptor agonist.” Arch Biochem Biophys 270(1): 344–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugen TB, Tefre T, Malm G, Jonsson BA, Rylander L, Hagmar L, Bjorsvik C, Henrichsen T, Saether T, Figenschau Y and Giwercman A. (2011). “Differences in serum levels of CB-153 and p,p’-DDE, and reproductive parameters between men living south and north in Norway.” Reprod Toxicol 32(3): 261–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaga K and Dharmani C. (2003). “Global surveillance of DDT and DDE levels in human tissues.” Int JOccup Med Environ Health 16(1): 7–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakszyn P, Goni F, Etxeandia A, Vives A, Millan E, Lopez R, Amiano P, Ardanaz E, Barricarte A, Chirlaque MD, Dorronsoro M, Larranaga N, Martinez C, Navarro C, Rodriguez L, Sanchez MJ, Tormo MJ, Gonzalez CA and Agudo A. (2009). “Serum levels of organochlorine pesticides in healthy adults from five regions of Spain.” Chemosphere 76(11): 1518–1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kafafi SA, Afeefy HY, Ali AH, Said HK, Abd-Elazem IS and Kafafi AG (1993). “Affinities for the aryl hydrocarbon receptor, potencies as aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase inducers and relative toxicities of polychlorinated biphenyls. A congener specific approach.” Carcinogenesis 14(10): 2063–2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kester MH, Bulduk S, Tibboel D, Meinl W, Glatt H, Falany CN, Coughtrie MW, Bergman A, Safe SH, Kuiper GG, Schuur AG, Brouwer A and Visser TJ (2000). “Potent inhibition of estrogen sulfotransferase by hydroxylated PCB metabolites: a novel pathway explaining the estrogenic activity of PCBs.” Endocrinology 141(5): 1897–1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kester MH, Bulduk S, van Toor H, Tibboel D, Meinl W, Glatt H, Falany CN, Coughtrie MW, Schuur AG, Brouwer A and Visser TJ (2002). “Potent inhibition of estrogen sulfotransferase by hydroxylated metabolites of polyhalogenated aromatic hydrocarbons reveals alternative mechanism for estrogenic activity of endocrine disrupters.” J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87(3): 1142–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C and Halter JB (2014). “Endogenous sex hormones, metabolic syndrome, and diabetes in men and women.” Curr Cardiol Rep 16(4): 467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C, Ricardo AC, Boyko EJ, Christophi CA, Temprosa M, Watson KE, Pi-Sunyer X and Kalyani RR (2019). “Sex Hormones and Measures of Kidney Function in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study.” J Clin Endocrinol Metab 104(4): 1171–1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer P, Kocan A, Drobna B, Susienkova K, Radikova Z, Huckova M, Imrich R, Ksinantova L and Klimes I. (2010). “Polychlorinated biphenyls and testosterone: age and congener related correlation approach in heavily exposed males.” Endocr Regul 44(3): 109–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madrigal JM, Ricardo AC, Persky V and Turyk M. (2019). “Associations between blood cadmium concentration and kidney function in the U.S. population: Impact of sex, diabetes and hypertension.” Environ Res 169: 180–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SA Jr., Harlow SD, Sowers MF, Longnecker MP, Garabrant D, Shore DL and Sandler DP (2002). “DDT metabolite and androgens in African-American farmers.” Epidemiology 13(4): 454–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez FD, Trejo-Acevedo A, Betanzos AF, Espinosa-Reyes G, Alegria-Torres JA and Maldonado IN (2012). “Assessment of DDT and DDE levels in soil, dust, and blood samples from Chihuahua, Mexico.” Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 62(2): 351–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather KJ, Kim C, Christophi CA, Aroda VR, Knowler WC, Edelstein SE, Florez JC, Labrie F, Kahn SE, Goldberg RB and Barrett-Connor E. (2015). “Steroid Sex Hormones, Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin, and Diabetes Incidence in the Diabetes Prevention Program.” J Clin Endocrinol Metab 100(10): 3778–3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauvais-Jarvis F, Clegg DJ and Hevener AL (2013). “The role of estrogens in control of energy balance and glucose homeostasis.” Endocr Rev 34(3): 309–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien KM, Upson K, Cook NR and Weinberg CR (2016). “Environmental Chemicals in Urine and Blood: Improving Methods for Creatinine and Lipid Adjustment.” Environ Health Perspect 124(2): 220–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada K, Yanai M, Takeuchi K, Matsuyama K, Nitta K, Hayashi K and Takahashi S. (2014). “Sex differences in the prevalence, progression, and improvement of chronic kidney disease.” Kidney Blood Press Res 39(4): 279–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker VS, Squirewell EJ, Lehmler HJ, Robertson LW and Duffel MW (2018). “Hydroxylated and sulfated metabolites of commonly occurring airborne polychlorinated biphenyls inhibit human steroid sulfotransferases SULT1E1 and SULT2A1.” Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 58: 196–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson DG Jr., Wong LY, Turner WE, Caudill SP, Dipietro ES, McClure PC, Cash TP, Osterloh JD, Pirkle JL, Sampson EJ and Needham LL (2009). “Levels in the U.S. population of those persistent organic pollutants (2003–2004) included in the Stockholm Convention or in other long range transboundary air pollution agreements.” Environ Sci Technol 43(4): 1211–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persky V, Turyk M, Anderson HA, Hanrahan LP, Falk C, Steenport DN, Chatterton R Jr. and Freels S. (2001). “The effects of PCB exposure and fish consumption on endogenous hormones.” Environ Health Perspect 109(12): 1275–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips DL, Pirkle JL, Burse VW, Bernert JT Jr., Henderson LO and Needham LL (1989). “Chlorinated hydrocarbon levels in human serum: effects of fasting and feeding.” Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 18(4): 495–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porta M, Pumarega J and Gasull M. (2012). “Number of persistent organic pollutants detected at high concentrations in a general population.” Environ Int 44: 106–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralph JL, Orgebin-Crist MC, Lareyre JJ and Nelson CC (2003). “Disruption of androgen regulation in the prostate by the environmental contaminant hexachlorobenzene.” Environ Health Perspect 111(4): 461–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saoudi A, Frery N, Zeghnoun A, Bidondo ML, Deschamps V, Goen T, Garnier R and Guldner L. (2014). “Serum levels of organochlorine pesticides in the French adult population: the French National Nutrition and Health Study (ENNS), 2006–2007.” Sci Total Environ 472: 1089–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Cai R, Sun J, Dong X, Huang R, Tian S and Wang S. (2017). “Diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for incident chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease in women compared with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Endocrine 55(1): 66–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjödin A, Jones RS, Caudill SP, Wong LY, Turner WE and Calafat AM (2014). “Polybrominated diphenyl ethers, polychlorinated biphenyls, and persistent pesticides in serum from the national health and nutrition examination survey: 2003–2008.” Environ Sci Technol 48(1): 753–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Specht IO, Bonde JP, Toft G, Giwercman A, Spano M, Bizzaro D, Manicardi GC, Jonsson BA and Robbins WA (2015). “Environmental hexachlorobenzene exposure and human male reproductive function.” Reprod Toxicol 58: 8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomczak S, Baumann K and Lehnert G. (1981). “Occupational exposure to hexachlorocyclohexane. IV. Sex hormone alterations in HCH-exposed workers.” Int Arch Occup Environ Health 48(3): 283–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turyk M, Anderson HA, Hanrahan LP, Falk C, Steenport DN, Needham LL, Patterson DG Jr., Freels S and Persky V. (2006). “Relationship of serum levels of individual PCB, dioxin, and furan congeners and DDE with Great Lakes sport-caught fish consumption.” Environ Res 100(2): 173–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turyk ME, Anderson HA, Freels S, Chatterton R Jr., Needham LL, Patterson DG Jr., Steenport DN, Knobeloch L, Imm P and Persky VW (2006). “Associations of organochlorines with endogenous hormones in male Great Lakes fish consumers and nonconsumers.” Environ Res 102(3): 299–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Birgelen AP (1998). “Hexachlorobenzene as a possible major contributor to the dioxin activity of human milk.” Environ Health Perspect 106(11): 683–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen A, Verdonck L and Kaufman JM (1999). “A critical evaluation of simple methods for the estimation of free testosterone in serum.” J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84(10): 3666–3672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.