Abstract

Previous research has revealed that the gut microbiome has a marked impact on acute liver failure (ALF). Here, we evaluated the impact of betaine on the gut microbiota composition in an ALF animal model. The potential protective effect of betaine by regulating Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) responses was explored as well. Both mouse and cell experiments included normal, model, and betaine groups. The rat small intestinal cell line IEC-18 was used for in vitro experiments. Betaine ameliorated the small intestine tissue and IEC-18 cell damage in the model group by reducing the high expression of TLR4 and MyD88. Furthermore, the intestinal permeability in the model group was improved by enhancing the expression of the (ZO)-1 and occludin tight junction proteins. There were 509 operational taxonomic units (OTUs) that were identified in mouse fecal samples, including 156 core microbiome taxa. Betaine significantly improved the microbial communities, depleted the gut microbiota constituents Coriobacteriaceae, Lachnospiraceae, Enterorhabdus and Coriobacteriales and markedly enriched the taxa Bacteroidaceae, Bacteroides, Parabacteroides and Prevotella in the model group. Betaine effectively improved intestinal injury in ALF by inhibiting the TLR4/MyD88 signaling pathway, improving the intestinal mucosal barrier and maintaining the gut microbiota composition.

Subject terms: Applied microbiology, Medical research

Acute liver failure (ALF), characterized by massive liver necrosis associated with severe impairment of hepatic function, is an intractable and high-mortality disease in clinical practice1. Regarding the pathogenesis of liver failure, the majority of scholars support the theory of the ‘two-hit hypothesis’. Hepatitis virus, ethanol, and hepatotoxicants always lead to liver injury directly, which is regarded as the primary hit. Intestinal endotoxemia, as the secondary cause of liver injury, also plays an important role in the occurrence and development of ALF2. In addition, liver failure patients are susceptible to mixed endotoxemia. This phenomenon is due mainly to the damaged intestinal mucosal barrier, which leads to a significant quantity of endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide, LPS) produced by the overgrowth of gram-negative bacteria3.

The integrated intestinal wall barrier consists mainly of the intestinal mucosal epithelium, tight junctions and intrinsic membrane under the epithelium4. The tight junction between epithelial cells contains the transmembrane proteins occludin, claudins, junctional adhesion molecules, and cytoplasm protein (ZO)-1. They are the most imperative part of the intestinal wall barrier5. Intestinal mucosal permeability is increased when these junctions are altered6. There is a close relationship between weakened intestinal mucosal immune function and mucosal mechanical barrier damage by bacteria. Both contribute to translocation of endotoxin and excessive intestinal pathogens7. Endotoxin is an LPS component that is recognized as an outer membrane component in gram-negative bacteria. Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). They play a valuable role in the intestinal mucosal immune system by mediating signal transduction. In particular, TLR4-mediated recognition of LPS occurs via the formation of two copies of the TLR4–MD2–LPS complex as a receptor multimer. Then, the complex recruits MyD88 (MyD88-dependent pathway) and TIR domain–containing adaptors (TIRAP, Mal). Once the MyD88-dependent pathway is activated, downstream signaling molecules are further activated, which leads to the release of many inflammatory mediators, including TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-188–10. A previous study indicated that the transcription of TLR4 is enhanced in ALF mice11.

Increasing evidence has shown a close correlation between the gut microbiome and liver diseases12. The liver conducts immune surveillance for multifarious pathogens from the gut, as well as influences intestinal mucosal immunity. The intestinal microbiome also affects liver function13. The mutual effect between the gut and liver is regarded as the “gut-liver axis”. The integrity of the intestinal epithelial barrier has been demonstrated to be regulated by the gut microbiota14. A compromised intestinal mucosal barrier contributes to bacterial translocation into the portal vein and then dissemination to the liver. This process leads to additional inflammation, liver cell apoptosis, and rapid progression to multiple organ failure15. The abundance of the pathogenic genus Proteus is increased in ALF rats, and Coriobacteriaceae, Bacteroidales and Allobaculum are markedly depleted in ALF rats16. Accumulating evidence suggests that the gut microbiota is involved in this process. Moreover, the abundances of Bacteroidetes, Ruminococcaceae, Porphyromonadaceae and Lachnospiraceae are decreased in fecal microbial communities in acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) patients compared to their levels before disease onset17. In addition, the levels of Firmicutes are increased in ACLF patient feces. The regulation of the intestinal microecology by microbial ecological agents has also been proposed as an emerging therapeutic strategy for liver failure18.

Betaine, as a vital human nutrient, exists in many tissues and organs and is especially abundant in the liver and kidney. It participates in the methyl cycle. It is often used as a feed additive to replace the biological function of methionine to reduce the cost of feedstuffs19. Many studies have shown that betaine has many pharmacological functions, such as antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects20,21. A retrospective study suggested that higher betaine intake may be related to a lower risk of primary liver cancer22. There is a favorable relationship between the blood betaine concentration and the severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in community-based participants23. Our previous studies have also indicated that betaine inhibited TLR4 expression to effectively improve alcoholic liver disease and NAFLD24,25. However, the effects of betaine on ALF and related mechanisms are still unknown. In particular, the influence of betaine on the gut microbial ecosystem needs further study.

At present, high-throughput next-generation sequencing techniques have been applied. They assist us in identifying the overall structure of the complex gut microbial ecosystem at the OTU level. In this study, we employed D-Gal/LPS in vivo and LPS in vitro to establish internal and external intestinal epithelial barrier disruption models of ALF, respectively. Betaine was employed as an intervention agent. The relationship between the expression of key molecules in the intestinal TLR4-mediated signaling pathway and intestinal tight junction proteins was examined. The gut microbial ecosystem was also studied to explore the potential therapeutic effect of betaine in acute liver failure.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Fetal bovine serum (FBS) and DMEM basic were purchased from Gibco (NY, USA). Betaine hydrochloride (purity of 99%) was purchased from Juhua Group Co. (Zhejiang, China). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS, purity of 99%) and D-galactosamine (D-Gal, purity of 98%) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, USA). Antibodies against TLR4, (ZO)-1 and GAPDH were purchased from Proteintech (Hubei, China). Rabbit anti-rat/mice occludin and MyD88 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Boston, USA). The Goat anti-rabbit fluorescent secondary antibody (IRDye800) was purchased from LI-COR Biosciences, Inc. (Lincoln, USA).

Cell culture

The rat small intestinal cell line IEC-18 was grown in DMEM medium with 10% FBS in an incubator at 37 °C, 5% CO2, and saturated humidity. LPS (1 μg/ml) was applied to cells in the model group, and low dose (3.4 mM), medium dose (5.1 mM) and high dose (6.8 mM) betaine groups were established. IEC-18 cells were seeded in 6-well plates. After 12 h, betaine (3.4 mM, 5.1 mM or 6.8 mM) was added to the different dose betaine groups. In addition, betaine (3.4 mM, 5.1 mM or 6.8 mM) only group was also set. All cells were harvested after models were incubated for 24 h.

Transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) measurement

IEC-18 cells were seeded at a 2.5 × 105 cells/ml single-cell suspension. Then, 1.5 ml of DMEM complete medium was added to the lower cell chambers, and 1 ml of the cell suspension was sequentially added to the upper cell chambers. The media in the upper and lower chambers in the betaine group were replaced by complete medium containing betaine. After 2 h, LPS (1 μg/ml) was added to the model group and betaine group. After administrating LPS, they were incubated for 24 h. The next experimental steps were performed as described in our previous report26. And then the calibrated Millipore Millicell ERS-2 cell resistance meter was used to detect resistance value. The measured resistance value was multiplied by the area of the filter to obtain an absolute value of TEER, expressed as Ωcm2. And the TEER values were measured as follows: TEER = (measured resistance value − blank value) × single cell layer surface area (cm2).

Animal groups

Eighteen male specific pathogen-free (SPF) mice weighing 20 ± 2 g were purchased from the Experimental Animal Center of Wuhan University. Animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University. The protocol was in accordance with the Guide for the Care of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH publication no. 85-23, revised 1996). Experimental animals were kept at an appropriate temperature (22 ± 2 °C) with a 12 h light/dark cycle and were allowed free access to food and water. After acclimation for 1 week, they were randomly divided into three groups: the normal, model, and betaine groups. D-Gal (400 mg/kg) and LPS (100 μg/kg) were administered by intraperitoneal injection in ALF model animals. Betaine (800 mg/kg per day) was administered intragastrically in the betaine groups one week before the ALF model was established. The other mice were administrated intragastrically the same amount of saline. Experimental animals were sacrificed 24 h after model and betaine group mice were given D-Gal/LPS.

Assessment of liver function and inflammatory mediators

Blood samples were collected after mouse euthanasia. A Hitachi Automatic Analyzer (Hitachi, Inc., Japan) was applied to detect serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and total bilirubin (TBIL) levels in mice. The levels of the serum inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and IL-18 were determined by ELISA kits (eBioscience, CA, USA). The level of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-18 in liver and small tissue were detected by Quantitative real-time PCR.

Histological examinations

Liver and small intestine specimens were fixed with 10% formaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and cut into sections with 5 μm thickness. Then, they were stained with hematoxylin–eosin (HE) for pathological studies under a BX 51 light microscope (Olympus, Japan).

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from small intestine tissue and IEC-18 cells using TRIzol reagent based on the manufacturer’s procedure. qRT-PCR was conducted with a SYBR Green PCR Kit (Takara Bio, Inc., Otsu, Japan). All primers (sequences in Table 1) were constructed by Tsingke (Wuhan, China). In this study, β-actin was selected as the housekeeping gene.

Table 1.

The primer sequences for RT-PCR.

| Genes | Forward (5′–3′) | Reverse (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| TNF-α (mouse) | CGTCAGCCGATTTGCTATCT | CGGACTCCGCAAAGTCTAAG |

| IL-1β (mouse) | TCAGGCAGGCAGTATCACTC | AGCTCATATGGGTCCGACAG |

| IL-18 (mouse) | GACAGCCTGTGTTCGAGGATATG | TGTTCTTACAGGAGAGGGTAGAC |

| TLR4 (rat) | TACAGTTCGTCATGCTTTCTC | ATTAGGAAGTACCTCTATGCAG |

| TLR4 (mouse) | AGCTTCTCCAATTTTTCAGAACTTC | TGAGAGGTGGTGTAAGCCATGC |

| MyD88 (rat) | AGGACAAACGAAGGAACTTTT | GCCGATAGTCTGTCTGTTCTAGT |

| MyD88 (mouse) | ACCTGTGTCTGGTCCATTGCCA | GCTGAGTGCAAACTTGGTCTGG |

| (ZO)-1 (rat) | GCTCACCAGGGTCAAAATGT | GGCTTAAAGCTGGCAGTGTC |

| (ZO)-1 (mouse) | GTTGGTACGGTGCCCTGAAAGA | GCTGACAGGTAGGACAGACGAT |

| Occludin (rat) | TTACGGCTATGGAGGGTACAC | GACGCTGGTAACAAAGATCAC |

| Occludin (mouse) | TGGCAAGCGATCATACCCAGAG | CTGCCTGAAGTCATCCACACTC |

| β-Actin (rat) | GTCGTACCACTGGCATTGTG | CTCTCAGCTGTGTGTGTGAA |

| β-Actin (mouse) | CTCTCAGCTGTGTGTGTGAA | TGCTGGAAGGTGGACAGTGAGG |

Western blotting

The IEC-18 cells and small intestine specimen extracts were subjected to 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Then, they were transferred to a Protran nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was sequentially incubated with a primary antibody at 4 °C overnight and secondary antibody for 1 h. Finally, an Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR Co.) was utilized to detect the protein levels. The protein levels of TLR4, MyD88, (ZO)-1, and occludin were normalized to that of GAPDH for each sample. The dilution ratio of all primary antibodies was 1:1000, and the dilution of secondary antibodies was 1:10,000. Incubating different primary antibodies after cutting on a whole membrane results in the absence of images of adequate length. But this experiment ensures that the gray value determination of each group of proteins on the same band is detected within the same size range.

Intestinal permeability

The everted sac method was employed to evaluate the small intestinal mucosal barrier function as previously described27. Segments were everted in Krebs buffer which was ice-cold and pH was 7.4, gently distended by injecting 1.5 ml Krebs. They were suspended in the organ bath for 30 min and maintained at 37 °C. The organ bath consisted of 500-ml Krebs with added FITC labeled dextran 4000 (FD4, 10 mg/ml), continuously bubbled with a gas mixture containing 95% O2 and 5% CO2. And then centrifuged at 1000g at 4 °C for 5 min. FD4 concentration was measured at an excitation wavelength of 492 nm and an emission wavelength of 515 nm with PerkinElmer LS-50 fluorescence spectrophotometer (PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, MA). Intestinal permeability was presented as FD4 concentration divided by the area of gut sac.

DNA extraction and 16S rRNA gene sequencing

Within 1 h before all animals were sacrificed, fecal samples were collected. They were frozen at − 80 °C immediately. DNA was extracted using a QIAGEN extraction kit (Universal Biotech Company, Shanghai, China). Total DNA quality was assessed by using a Thermo Qubit.

Sequencing library construction

The V3-4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified using custom barcoded primers and sequenced as described previously using an Illumina MiSeq sequencer28. Briefly, the V3-4 domain of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified using the primers F (5′-CTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3′) and R (5′-GACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′). Employing diluted genomic DNA as a template, PCR was performed utilizing Taq DNA Polymerase (Vazyme Biotech Company, Nanjing, China) to ensure the accuracy and efficiency of the amplification. Then, the PCR product library was examined by a Fragment Analyzer. After the library quality was deemed eligible, the corresponding ratios were mixed according to the volume required in each sample. The mixed library was subjected to gel purification (cutting range: 500–750 bp) using a QIAquick gel recovery kit (Universal Biotech Company, Shanghai, China). After purification, the Fragment Analyzer and an Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 6 real-time PCR instrument were used to examine and quantify the library. Sequencing was performed using an Illumina MiSeq PE300.

After performing quality control of the original data, Usearch software was applied to de-chimerize and cluster the data. For Usearch clustering, reads were first sorted according to the abundance from large to small, and the standard clustering of 97% similarity was obtained. Each operational taxonomic unit (OTU) was considered to represent a species. Next, the reads of each sample were randomly leveled, and the corresponding OTU sequence was extracted. Then, we used QIIME software to generate a dilution curve of the alpha diversity index, selected reasonable sampling parameters according to the dilution curve, and analyzed the obtained OTUs. A read was extracted as a representative sequence from the OTU. Next, according to the 16S rRNA database, the representative sequence was applied to classify each OTU by using the RDP method. After categorization, an OTU abundance table was obtained in line with the number of sequences belonging to each OTU. Finally, subsequent analysis was performed according to the OTU abundance table29.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical significance was determined using the analysis of variance (ANOVA) method, followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Calculations were performed with SPSS 16.0. Alpha diversity was used to analyze the complexity of species diversity for a single sample. Beta diversity analysis was applied to assess differences in species complexity among samples. LEfSe was used by linear discriminant analysis (LDA) to evaluate the influence of each species abundance to determine significant communities or species in sample partitioning.

Results

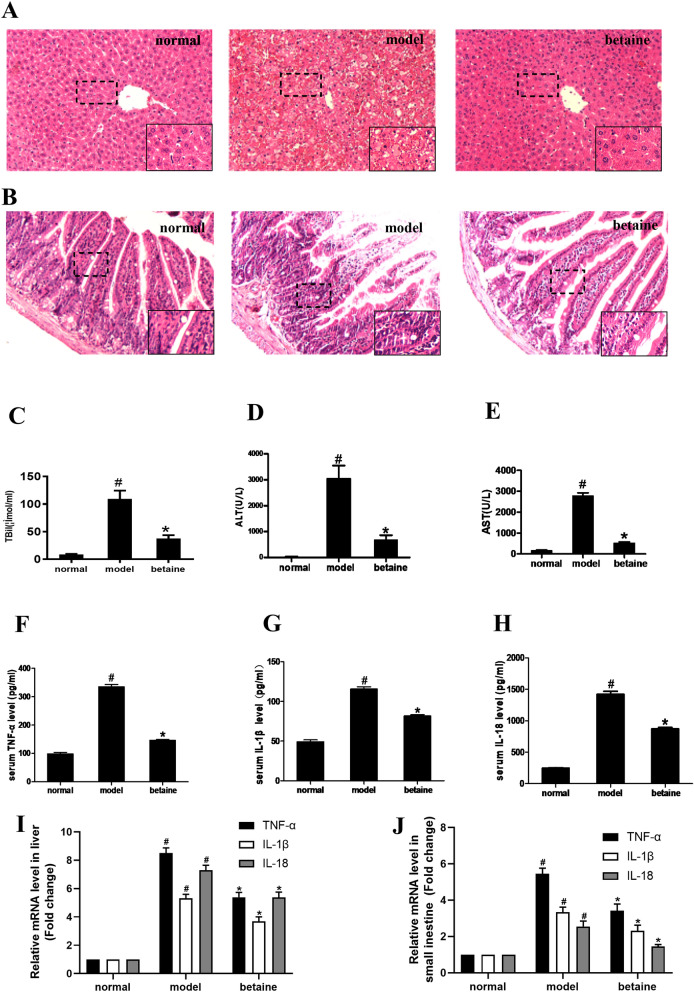

Betaine ameliorated liver and small intestine injury in ALF mice

Pathological changes in mouse liver tissue and serum biochemical markers were assessed. The structure of liver lobules and the arrangement of liver cells were clear and orderly in the normal group. There was also no necrosis of hepatocytes or infiltration of inflammatory cells in the normal group. However, in the model group, the liver lobular structure was destroyed, and a larger amount of hepatocyte necrosis was observed. Compared with model group, the degrees of hepatocyte necrosis were lessened in the betaine group (Fig. 1A). Serum ALT, AST and TBIL levels in the model animals were significantly increased compared with those in the normal group animals (P < 0.05). Nevertheless, the ALT, AST and TBIL levels were much lower in the betaine groups than in the model group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1C–E). As shown in Fig. 1B, histological analysis indicated that the lamina propria and villi of the model group were denuded, the epithelial layer of the small intestine was exfoliated, the height of the small intestine was reduced. In contrast, betaine conserved almost normal architecture in the small intestine. Compared with those in the normal group, the serum levels and liver and small intestine mRNA levels of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-18 were greatly increased in the model group. Betaine significantly decreased the levels of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-18 in the model group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1F–J). Moreover, the intestinal permeability remarkably increased in the model group compared with that in the normal group (P < 0.05). Betaine dramatically improved intestinal permeability in the model animals (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2A).

Figure 1.

Effect of betaine on liver and small intestine tissue pathological changes and serum biochemical indicators in ALF mice. (A) The liver tissues were stained with HE (× 200). (B) The small intestine tissues were stained with HE (× 200). (C–E) The serum levels of ALT, AST, and TBIL in different animal groups. #P < 0.05, compared with the normal group; *P < 0.05, compared with the model group. (F–H) The serum levels of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-18 in each group. (I,J) The relative mRNA levels of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-18 in liver and small intestine tissue. #P < 0.05, compared with the normal group; *P < 0.05, compared with the model group.

Figure 2.

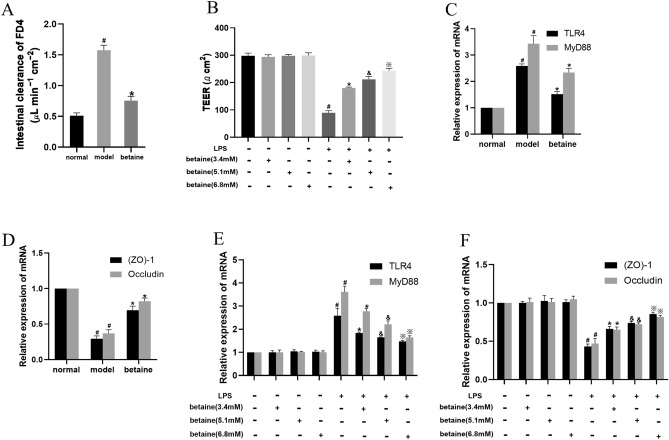

Effect of betaine on the TLR4/MyD88 pathway, (ZO)-1 and occludin mRNA levels and intestinal permeability in ALF mice and LPS-stimulated IEC-18 cells. (A) Intestinal permeability in each animal group. (B) The TEER value in different cell groups. (C,D) The mRNA levels of TLR4, MyD88, (ZO)-1 and occludin in different animal groups. (E,F) The mRNA levels of TLR4, MyD88, (ZO)-1 and occludin in different cell groups. #P < 0.05, compared with the normal group; *P < 0.05, compared with the model group; &P < 0.05, compared with the low-dose betaine group; ※P < 0.05, compared with the medium-dose betaine group.

Betaine inhibited the TLR4/MyD88 pathway and improved the mRNA and protein expression of (ZO)-1 and occludin in ALF mice

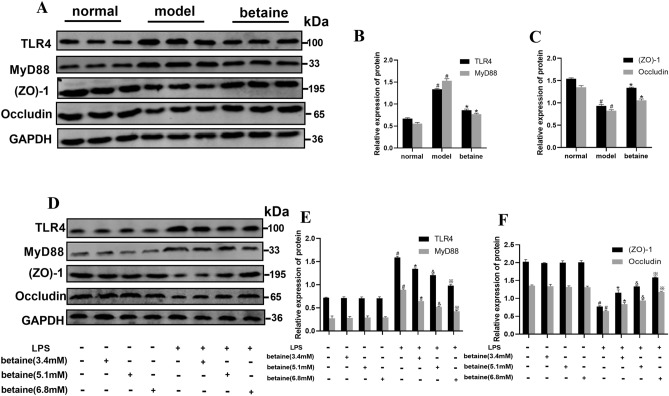

The effect of betaine by regulating the TLR4/MyD88 pathway in ALF model mice was assessed. Compared with those in the normal group, the mRNA and protein level of the TLR4 and MyD88 were obviously increased in the model group (P < 0.05). The mRNA and protein level of TLR4 and MyD88 were significantly decreased in the betaine group compared with those in the model group (Figs. 2C, 3A, B). Furthermore, the results showed that the mRNA levels of (ZO)-1 and occludin were both distinctly decreased in the model group compared with those in the normal group (P < 0.05). Betaine significantly elevated the expression of (ZO)-1 and occludin in the model animals (P < 0.05) (Figs. 2D, 3A,C).

Figure 3.

Effect of betaine on the TLR4/MyD88 pathway, (ZO)-1 and occludin protein levels in ALF mice and IEC-18 cell induced with LPS. (A–C) The protein levels of TLR4, MyD88, (ZO)-1 and occludin in different animal groups. (D–F) The protein levels of TLR4, MyD88, (ZO)-1 and occludin in different cell groups. #P < 0.05, compared with the normal group; *P < 0.05, compared with the model group; &P < 0.05, compared with the low-dose betaine group; ※P < 0.05, compared with the medium-dose betaine group.

Betaine suppressed the TLR4/MyD88 pathway and enhanced the levels of (ZO)-1 and occludin in IEC-18 cells stimulated by LPS

Cell experiments were performed to verify the protective effect of betaine in LPS-stimulated IEC-18 intestinal epithelial cells. The results showed that the mRNA levels of TLR4 and MyD88 were prominently increased in the model group compared with those in the normal group (P < 0.05). Compared with those for the model treatment, the mRNA and protein level of TLR4 and MyD88 were dramatically suppressed by betaine administration (P < 0.05). The TLR4 and MyD88 mRNA and protein level were also significantly different among the high-, medium- and low-dose betaine groups (Figs. 2E, Fig. 3D,E, P < 0.05). As shown in Figs. 2F, 3D,F, compared with those in the normal group, the mRNA and protein expression level of (ZO)-1 and occludin were markedly reduced in the model group (P < 0.05). The mRNA and protein expression of (ZO)-1 and occludin were significantly improved in the betaine group compared with those in the model group (P < 0.05). Moreover, the mRNA and protein level of (ZO)-1 and occludin in the medium-dose betaine group were elevated compared with those in the low-dose betaine group and were the highest in the high-dose betaine group (P < 0.05). This increased expression also showed dose dependence. But there was no statistical significance between normal group and only betaine group (high-, medium- and low-dose) in protein and mRNA level of TLR4, MyD88, (ZO)-1 and occludin.

Betaine elevated the TEER value in LPS-stimulated IEC-18 cells

As shown in Fig. 2B, the TEER value was greatly decreased in the model group compared with that in the normal group (P < 0.05). The TEER value was significantly elevated after betaine treatment in the model group (P < 0.05). In addition, there were significant differences among the high-, medium- and low-dose betaine groups (P < 0.05). And there was no statistical significance between normal group and only betaine group (high, medium and low-dose) in TEER value.

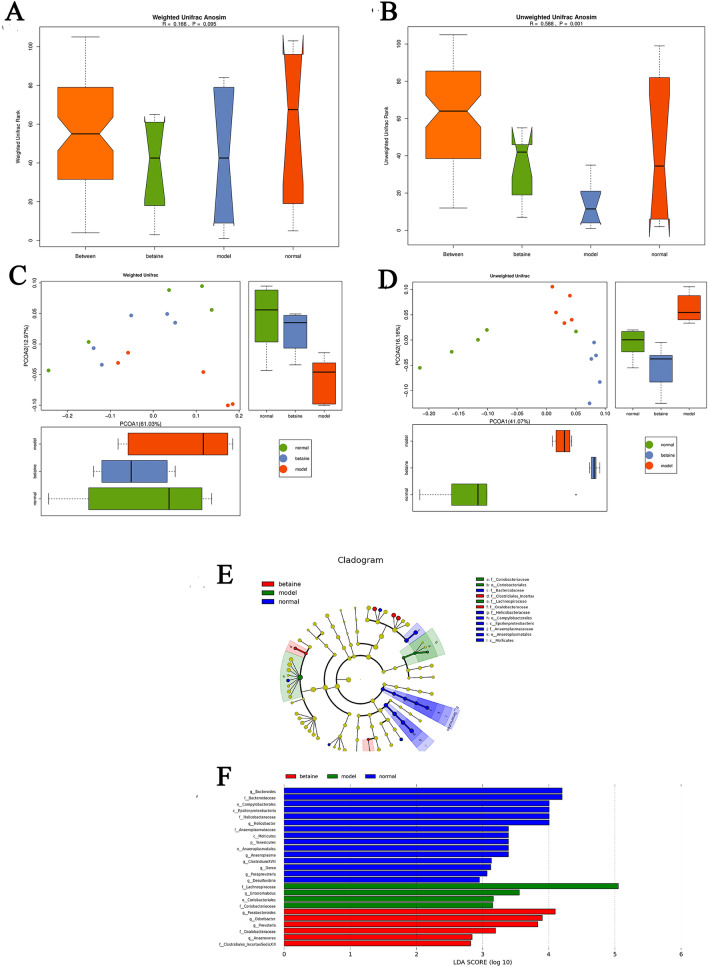

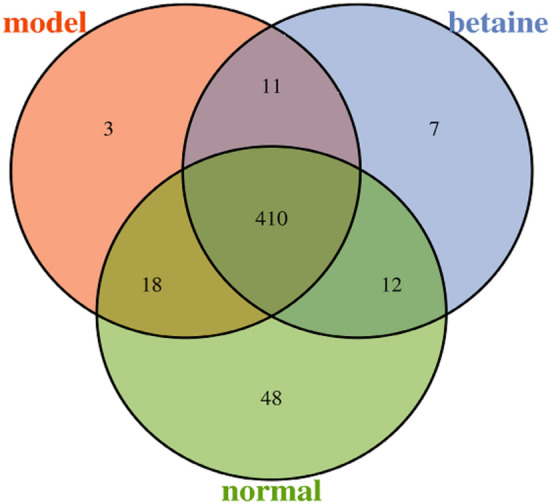

OTU analysis

In our experiments, 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis was used to explore the potential therapeutic microecological mechanisms of betaine in ALF mice. The OTU network analysis for fecal samples of mice provided certain core OTUs and a universal microbial composition among each group. A total of 509 OTUs were identified from 15 fecal samples (Supplementary files Table S1). As shown in Fig. 4, the normal group contained the maximum OTUs, but the betaine and model groups possessed a similar number of OTUs. The core microbiome that was present in each fecal sample could be found based on the shared OTUs of each sample and the species represented by the OTUs. There were 156 core microbiome constituents in fecal samples (Supplementary files Table S2).

Figure 4.

OTU analysis. OTU Venn diagram showing different color patterns representing different groups, and the number of overlaps between different color patterns was the number of OTUs shared between the two groups.

Alpha diversity analysis

Alpha diversity contains the observed species index, the Chao1 index, the Shannon index and the Simpson index. The observed species index indicates the actual number of OTUs observed, and the Chao1 index is performed to calculate the total number of OTUs contained in a sample. Both of them indicate the species richness of the sample. The Simpson index and Shannon index are applied to evaluate species diversity. As shown in Table 2, the species richness and diversity of the microbiota among the three groups did not have notable differences. However, the fecal bacteria in the normal group had relatively higher levels of species richness and diversity than those in the other groups.

Table 2.

Alpha diversity analysis.

| Sample name | Observed species | Chao1 | Shannon | Simpson |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p value | 0.1 | 0.22 | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| Mean (normal) | 383 | 411.79 | 6.64 | 0.98 |

| Mean (model) | 364.2 | 397.32 | 6.38 | 0.97 |

| Mean (betaine) | 337.8 | 378.8 | 6.32 | 0.98 |

Beta diversity analysis

Different from alpha diversity analysis, beta diversity analysis is appropriate to distinguish the differences in species diversity among a pair of samples. UniFrac compares species community differences using phylogenetic evolution information. The results can serve as an index to detect beta diversity, which has taken into account the evolutionary distance between species. UniFrac results are classified into weighted UniFrac and unweighted UniFrac. Weighted UniFrac considers the abundance of sequences, and unweighted UniFrac does not. Beta diversity analyses include ANOSIM and principal coordinates analysis (PCoA). ANOSIM is a nonparametric test used to detect whether the difference between two or more groups is significantly greater than the intragroup difference to judge whether the grouping is reasonable. As shown in Fig. 5A,B, ANOSIM using weighted UniFrac distances and unweighted UniFrac clustered samples. The data revealed that intermouse variations in the fecal microbiota were lower than the intragroup variations, which showed that the fecal microbiota of each group had better individual similarity. PCoA showed that the distances between two samples were close, which indicated that the species compositions of the two samples were similar. The results of PCoA showed that the microbial composition between the normal group and betaine group was more similar than that between the normal and model groups (Fig. 5C,D).

Figure 5.

Beta diversity, including ANOSIM and PCoA. (A,B) Weighted UniFrac ANOSIM and unweighted UniFrac ANOSIM; (C,D) weighted UniFrac PCoA and unweighted PCoA. (E,F) LEfSe showed a cluster tree (E), and a histogram (F) representing the gut bacteria, which were of important biological significance in each group.

LDA effect size (LEfSe)

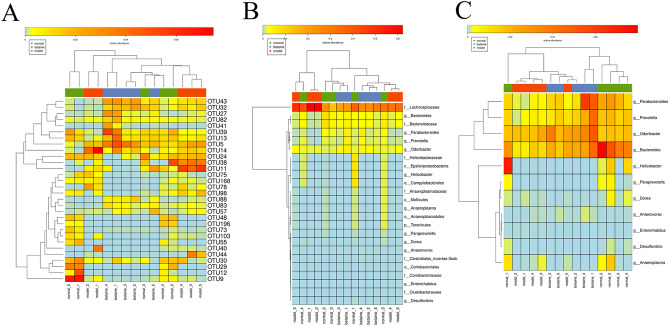

LEfSe emphasizes statistical significance and biological relevance. As shown in Fig. 5E,F, a cluster tree displayed different colors representing different groups, and nodes of different colors represented corresponding important microorganisms in each group. However, the yellow node represents nonsignificant microbes. The 11 bacterial species in fecal samples, such as g-Bacteroide, f-Bacteroidaceae, o-Campylobacterales and c-Epsilonproteobacteria, had a significant effect on the normal group. F-Lachnospiraceae, g-Enterorhabdus, o-Coriobacteriales and f-Coriobacteriaceae contributed greatly in the model group. G-Parabacteroides, g-Odoribacter, g-Prevotella, f-Oxalobacteraceae, g-Anaerovorax and f-Clostridiales-IncertaeSedisXIII were of crucial importance in the betaine group. As shown in Fig. 6A and Supplementary files Table S3, there were a total of 143 OTUs that had a significant difference between groups (P < 0.05). As shown in Fig. 6B,C and Supplementary files Table S4, a total of 24 species, which represented 11 genera, were significantly different between groups (P < 0.05). At the genus level, they are g-Anaeroplasma, g-Anaerovorax, g-Bacteroides, g-Desulfovibrio, g-Dorea, g-Enterorhabdus, g-Helicobacter, g-Odoribacter, g-Parabacteroides, g-Paraprevotella and g-Prevotella. Among them, an increased relative abundance of g-Enterorhabdus was detected in the model group compared with that in the normal group (P < 0.05). Betaine downregulated the relative abundance of g-Enterorhabdus (P < 0.05). The relative abundance of g-Bacteroides was the highest in the normal group and the lowest in the model group (P < 0.05). The relative abundance of g-Prevotella was almost the same in the normal and betaine groups and was reduced in the betaine group (P < 0.05).

Figure 6.

LEfSe showed three heatmaps. (A) The OTUs with a significant difference between different groups. (B) A total of 24 species with significant differences between groups. (C) There were 11 genera that were significantly different between groups.

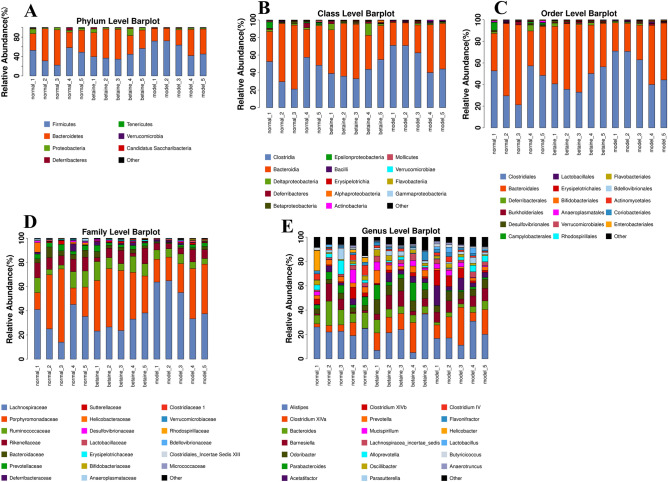

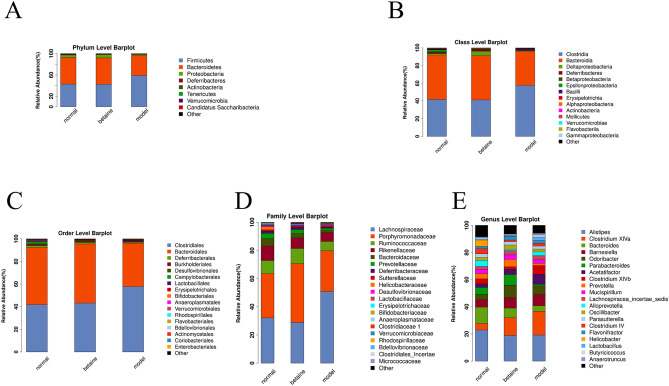

Species classification and abundance analysis

A sequence with the highest abundance was selected from each OTU as a representative sequence of the OTU. Using the RDP method, the representative sequence was aligned with the 16S database to classify each OTU to a corresponding species. Forming a relative abundance histogram of species, we visually observed the proportion of different species abundances in each sample and group. As shown in Figs. 7A–E, 8A–E, at the classification level of phylum, class, order, family, and genus, the corresponding histograms of microbiome species profiling were produced for each sample and group. The majority of the microbiome at the phylum level among each group belonged to Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, Deferribacteres, Actinobacteria, Tenericutes, Verrucomicrobia and Candidatus Saccharibacteria. Surprisingly, the majority of the microbiome phyla occupied similar proportions between the normal group and the model group. In addition, Firmicutes was the most abundant phylum in each group. The relative abundance of Firmicutes in model mouse feces (58.8%) was significantly higher than that in the normal (42.5%) and betaine group mouse feces (42.3%) (P < 0.05). A previous study confirmed that the levels of Firmicutes were positively correlated with ACLF severity and that the abundance of Bacteroidetes was inversely correlated. It has been suggested that betaine plays a role in potentially modifying the gut bacterial community. The relative abundance of Bacteroidetes in model mouse feces (37.8%) was apparently lower than that in the normal (50.2%) and betaine group mouse feces (49.5%) (P < 0.05) (Fig. 8A and Supplementary files Table S5). The relative abundance of Alistipes (belonging to Bacteroidetes) was enriched in the normal group (22.9%) and decreased in the betaine (18.8%) and model groups (19.1%) (P < 0.05). Moreover, compared with that in the normal group, the relative abundance of Clostridium XlVa (belonging to Bacteroidetes) was significantly higher in the model group. Betaine pretreatment reduced the relative abundance of Clostridium XlVa in the model group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 8E and Supplementary files Table S6). In general, the abundances of the gut microbiota taxa Coriobacteriaceae, Lachnospiraceae, Enterorhabdus and Coriobacteriales were remarkably increased in the model group, contrary to those of the gut microbiota taxa Bacteroidaceae, Bacteroides, Parabacteroides and Prevotella. Betaine significantly altered the microbial communities, depleted the gut microbiota constituents Coriobacteriaceae, Lachnospiraceae, Enterorhabdus and Coriobacteriales and markedly enriched the taxa Bacteroidaceae, Bacteroides, Parabacteroides and Prevotella (P < 0.05) (Fig. 8A–E). These results indicated that alteration of the gut microbiome might be a crucial therapeutic target in ALF.

Figure 7.

Species classification and abundance analysis. (A–E) The corresponding histograms of species profiling were produced for each sample at the classification level of phylum, class, order, family, and genus.

Figure 8.

Species classification and abundance analysis. (A–E) The corresponding histograms of species profiling were produced for each group at the classification level of phylum, class, order, family, and genus.

Discussion

Since 1998, when Marshall proposed the gut-liver axis, much attention has been paid to the role of the gut in liver disease30. Systemic endotoxemia, characterized by increased plasma LPS concentrations, increased intestinal permeability by altering tight junctions and thus resulted in more endotoxins entering the portal vein and activating Kupffer cells in the liver. This effect results in the production of proinflammatory cytokines and acute inflammatory response proteins, which persistently aggravate hepatic insufficiency and/or failure2. In addition, our previous study indicated that intestinal injury plays a vital role in ALF progression27. All these results support that if intestinal injury was reduced, liver lesions would be alleviated in ALF. The gut-liver axis plays an essential role in the pathogenesis of ALF.

Epithelial cells are held together by the apical junctional complex, which includes transmembrane proteins (claudins and occludin) and the cytosolic scaffold proteins (ZO)-(1–3) and cingulin. Research has proven that inflammatory conditions contribute to significant disturbance of mucosal barrier function, with decreased expression and redistribution of claudin, (ZO)-1, and occludin, which lead to increased permeability31. LPS, which can trigger a powerful inflammatory response, is recognized as a causal or complicating factor of multiple serious diseases. One of the mechanisms that prevents LPS from transiting from the intestine into the systemic circulation is through TLRs, which can activate the immune system32. However, the continuous stimulation of TLR signaling does not always exert positive impacts on the host, and it can enhance hepatic injury in chronic viral hepatitis, NASH, and alcoholic liver disease33–35. In addition, the reorganization of (ZO)-1 in tight junctions is activated by TLRs. There are 11 TLRs that have been identified in mammals, whereas LPS binds mainly TLR4. The MyD88-dependent pathway, as one of the downstream signaling events mediated by TLR4, leads to the recruitment of numerous molecules that activate tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) and other proinflammatory factors8. TNF-α can downregulate the transmembrane tight junction protein expression of occludin, paralleling the barrier disturbance detected electrophysiologically, which leads to an increase in intestinal permeability36. In our animal and cell experiments, the results indicated that mRNA and protein level of TLR4 and MyD88 were increased in intestine induced by LPS. And the levels of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-18 in serum, liver and small intestine were greatly increased in the ALF model group. However, the protein and mRNA level of (ZO)-1 and occludin were decreased in intestine stimulated by LPS. The intestinal permeability is increased in ALF model. Our data also proved that TLR4/MyD88 signaling pathway played a vital role in intestine injury in ALF which was consistent with previous findings37.

The intestinal epithelial barrier is not a static physical barrier but rather strongly interacts with immune system cells and the gut microbiome. Under physiological conditions, there is a dynamic regulation of tight junction components in the intestine. However, sustaining infections or inflammation can result in dysregulation in the expression of adhesion molecules, bringing about barrier breach and disturbance of gut microbes38. Studies have demonstrated that TLRs are innate pattern recognition receptors involved in host defense, preference for normal over commensal bacteria and the maintenance of tissue integrity39. An experiment was performed with MyD88-negative mice with a certain microbial consortium representing bacterial phyla normally existing in the human gut40. It was found that B. adolescentis exhibited antiinflammatory properties in D-Gal-treated rats. The gut microbiota is involved in this process. A study showed that S. boulardii notably reduced the relative abundance of the phylum Bacteroidetes by enhancing the relative abundances of Firmicutes and Proteobacteria in ALF mice41.

Betaine, an oxidative metabolite of choline, can protect rats from induction of LPS hepatotoxicity42. Betaine can be used as a methyl donor, catalyzed by betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase, to re-methylate homocysteine to produce methionine, thereby reducing homocysteine level. At present, betaine is not used clinically. But betaine widely exists in nature, such as in spinach. Moreover, significant amount of data from animal models of liver disease indicates that administration of betaine can halt and even reverse progression of the disruption of liver function43. The present study showed that betaine exerts positive effects on the gut-liver axis, including inhibition of potent inflammatory responses and maintenance of gut integrity. Moreover, in cell experiments, the dose of betaine was positively correlated with its protective effect in the model group. In our study, 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis was used to explore the potential therapeutic microecological mechanisms of betaine in ALF mice. There were 156 core microbiome constituents in fecal samples. The abundances of the gut microbiota taxa Coriobacteriaceae, Lachnospiraceae, Enterorhabdus and Coriobacteriales were remarkably increased in the model group, contrary to those of the gut microbiota taxa Bacteroidaceae, Bacteroides, Parabacteroides and Prevotella. Betaine significantly increased the microbial communities, depleted the gut microbiota constituents Coriobacteriaceae, Lachnospiraceae, Enterorhabdus and Coriobacteriales and markedly enriched the taxa Bacteroidaceae, Bacteroides, Parabacteroides and Prevotella. What’s more, the previous study has also demonstrated that Bacteroides and Prevotella were depleted in D-Gal-induced liver injury44. Based on available research, Prevotella is beneficial to glucose metabolism and improve hepatic glycogen storage45. Prevotella is suggested to exert protective effects against the development of NAFLD and to be more abundant in healthy subjects than that in NAFLD patients46. Bacteroides can ferment undigested polysaccharides and is the most predominant anaerobe in the gut47. The inflammatory cytokines level of TNF-α was negatively correlated with Bacteroidetes in ACLF patients17. And our results showed that Bacteroidetes was significantly decreased and the level of TNF-α was markedly increased in ALF mouse. Besides, Enterorhabdus, a member of the family Coriobacteriaceae, is isolated from a mouse model of spontaneous colitis48. Several reports found that the Lachnospiraceae is enhanced in NALFD patients and it contributes to the development of obesity and diabetes in ob/ob mice49. In short, administration of betaine modifies the gut bacterial community, enriching beneficial microbial taxa and inhibiting opportunistic pathogens, and this effect may help ameliorate liver failure.

Conclusion

Betaine improved liver function, liver and small intestine histology, and intestinal permeability and consolidated the tight junction between small intestine epithelial cells. The present study not only proved that betaine had hepatoprotective effects in ALF mice but also further demonstrated its protective effects on the structure and function of the small intestine. One of the protective effects of betaine on the small intestine in ALF occurs via inhibition of the LPS/TLR4/MyD88 pathway, improving intestinal permeability and ultimately dramatically shaping the gut microbiota in mice. This work revealed a new role for betaine in improving hepatic lesions. These findings thus suggested that the compounds targeted in the gut-liver axis should be further investigated as novel adjunctive therapies for ALF. Additional clinical studies are needed to verify an effective strategy to prevent and manage ALF by altering the gut bacterial community.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

Z.G. designed the study and revised the manuscript. Q.C. and Y.W. carried out experiments and performed the bioinformatic and statistical analysis. Q.C. and L.W. wrote the manuscript. F.J., M.P. and C.S. helped to perform experiments. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-020-78935-6.

References

- 1.Lee WM. Recent developments in acute liver failure. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2012;26:3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han DW. Intestinal endotoxemia as a pathogenetic mechanism in liver failure. World J. Gastroenterol. 2002;8:961–965. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v8.i6.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jalan R, Williams R. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: pathophysiological basis of therapeutic options. Blood Purif. 2002;20:252–261. doi: 10.1159/000047017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patterson AM, Watson AJM. Deciphering the complex signaling systems that regulate intestinal epithelial cell death processes and shedding. Front. Immunol. 2017;8:841. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han X, et al. Increased iNOS activity is essential for intestinal epithelial tight junction dysfunction in endotoxemic mice. Shock. 2004;21:261–270. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000112346.38599.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scaldaferri F, et al. The gut barrier: new acquisitions and therapeutic approaches. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2012;46(Suppl):S12–S17. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31826ae849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Istvan ES, Deisenhofer J. Structural mechanism for statin inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase. Science. 2001;292:1160–1164. doi: 10.1126/science.1059344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawai T, Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat. Immunol. 2010;11:373–384. doi: 10.1038/ni.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doyle SL, O'Neill LA. Toll-like receptors: from the discovery of NFkappaB to new insights into transcriptional regulations in innate immunity. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2006;72:1102–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arancibia SA, et al. Toll-like receptors are key participants in innate immune responses. Biol. Res. 2007;40:97–112. doi: 10.4067/S0716-97602007000200001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang H, Li Y. Protective effect of bicyclol on acute hepatic failure induced by lipopolysaccharide and d-galactosamine in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2006;534:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.12.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tranah TH, et al. Systemic inflammation and ammonia in hepatic encephalopathy. Metab. Brain Dis. 2013;28:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s11011-012-9370-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang W, et al. Dysbiosis gut microbiota associated with inflammation and impaired mucosal immune function in intestine of humans with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:8096. doi: 10.1038/srep08096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarin SK, Choudhury A. Acute-on-chronic liver failure. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2016;18:61. doi: 10.1007/s11894-016-0535-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verbeke L, et al. Bench-to-beside review: acute-on-chronic liver failure—linking the gut, liver and systemic circulation. Crit. Care. 2011;15:233. doi: 10.1186/cc10424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y, et al. Bifidobacterium adolescentis CGMCC 15058 alleviates liver injury, enhances the intestinal barrier and modifies the gut microbiota in d-galactosamine-treated rats. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019;103:375–393. doi: 10.1007/s00253-018-9454-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Y, et al. Gut dysbiosis in acute-on-chronic liver failure and its predictive value for mortality. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015;30:1429–1437. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bischoff SC, et al. Intestinal permeability—a new target for disease prevention and therapy. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:189. doi: 10.1186/s12876-014-0189-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Day CR, Kempson SA. Betaine chemistry, roles, and potential use in liver disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1860:1098–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ganesan B, Anandan R. Protective effect of betaine on changes in the levels of lysosomal enzyme activities in heart tissue in isoprenaline-induced myocardial infarction in Wistar rats. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2009;14:661–667. doi: 10.1007/s12192-009-0111-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bingul I, et al. Betaine treatment decreased oxidative stress, inflammation, and stellate cell activation in rats with alcoholic liver fibrosis. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2016;45:170–178. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2016.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou RF, et al. Higher dietary intakes of choline and betaine are associated with a lower risk of primary liver cancer: a case–control study. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:679. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00773-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen YM, et al. Associations of gut-flora-dependent metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide, betaine and choline with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in adults. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:19076. doi: 10.1038/srep19076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi QZ, et al. Betaine inhibits toll-like receptor 4 expression in rats with ethanol-induced liver injury. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010;16:897–903. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i7.897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang W, et al. Betaine protects against high-fat-diet-induced liver injury by inhibition of high-mobility group box 1 and Toll-like receptor 4 expression in rats. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2013;58:3198–3206. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2775-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Y, et al. The protective mechanism of CAY10683 on intestinal mucosal barrier in acute liver failure through LPS/TLR4/MyD88 pathway. Mediat. Inflamm. 2018;2018:7859601. doi: 10.1155/2018/7859601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Q, et al. Trichostatin A protects against intestinal injury in rats with acute liver failure. J. Surg. Res. 2016;205:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kozich JJ, et al. Development of a dual-index sequencing strategy and curation pipeline for analyzing amplicon sequence data on the MiSeq Illumina sequencing platform. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013;79:5112–5120. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01043-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Langille MG, et al. Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:814–821. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marshall JC. The gut as a potential trigger of exercise-induced inflammatory responses. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1998;76:479–484. doi: 10.1139/y98-049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanchez de Medina F. Intestinal inflammation and mucosal barrier function. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2014;20:2394–2404. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guerville M, Boudry G. Gastrointestinal and hepatic mechanisms limiting entry and dissemination of lipopolysaccharide into the systemic circulation. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2016;311:G1–G15. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00098.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dhillon N, et al. A single nucleotide polymorphism of Toll-like receptor 4 identifies the risk of developing graft failure after liver transplantation. J. Hepatol. 2010;53:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miura K, et al. Toll-like receptor 9 promotes steatohepatitis by induction of interleukin-1beta in mice. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:323–334 e7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.03.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Inokuchi S, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates alcohol-induced steatohepatitis through bone marrow-derived and endogenous liver cells in mice. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2011;35:1509–1518. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01487.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mankertz J, et al. Expression from the human occludin promoter is affected by tumor necrosis factor alpha and interferon gamma. J. Cell Sci. 2000;113:2085–2090. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.11.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spruss A, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 is involved in the development of fructose-induced hepatic steatosis in mice. Hepatology. 2009;50:1094–1104. doi: 10.1002/hep.23122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takiishi T, et al. Intestinal barrier and gut microbiota: Shaping our immune responses throughout life. Tissue Barriers. 2017;5:e1373208. doi: 10.1080/21688370.2017.1373208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rakoff-Nahoum S. Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell. 2004;118:229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wen L, et al. Innate immunity and intestinal microbiota in the development of Type 1 diabetes. Nature. 2008;455:1109–1113. doi: 10.1038/nature07336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu L, et al. Saccharomycesboulardii administration changes gut microbiota and attenuates d-galactosamine-induced liver injury. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1359. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01271-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim SK, Kim YC. Attenuation of bacterial lipopolysaccharide-induced hepatotoxicity by betaine or taurine in rats. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2002;40:545–549. doi: 10.1016/S0278-6915(01)00102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Christopher RD, Stephen AK. Betaine chemistry, roles, and potential use in liver disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1860:1098–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Q, et al. Lactobacillushelveticus R0052 alleviates liver injury by modulating gut microbiome and metabolome in d-galactosamine-treated rats. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019;103:9673–9686. doi: 10.1007/s00253-019-10211-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kovatcheva-Datchary P, et al. Dietary fiber-induced improvement in glucose metabolism is associated with increased abundance of Prevotella. Cell Metab. 2015;22:971–982. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shen F, et al. Gut microbiota dysbiosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2017;16:375–381. doi: 10.1016/S1499-3872(17)60019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wexler HM. Bacteroides: the good, the bad, and the nitty-gritty. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2007;20:593–621. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00008-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Clavel T, et al. Enterorhabduscaecimuris sp. nov, a member of the family Coriobacteriaceae isolated from a mouse model of spontaneous colitis, and emended description of the genus Enterorhabdus. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2009;60:1527–1531. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.015016-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kameyama K, Itoh K. Intestinal colonization by a Lachnospiraceae bacterium contributes to the development of diabetes in obese mice. Microbes Environ. 2014;29:427–430. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME14054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.