Abstract

Survival and adaptation to oxidative stress is important for many organisms, and these occur through the activation of many different signaling pathways. In this report, we showed that Caenorhabditis (C.) elegans G protein–coupled receptor kinases modified the ability of the organism to resist oxidative stress. In acute oxidative stress studies using juglone, loss-of-function grk-2 mutants were more resistant to oxidative stress compared with loss-of-function grk-1 mutants and the wild-type N2 animals. This effect was Ce-AKT-1 dependent, suggesting that Ce-GRK2 adjusted C. elegans oxidative stress resistance through the IGF/insulin-like signaling (IIS) pathway. Treating C. elegans with a GRK2 inhibitor, the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor paroxetine, resulted in increased acute oxidative stress resistance compared with another selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, fluoxetine. In chronic oxidative stress studies with paraquat, both grk-1 and grk-2 mutants had longer lifespan compared with the wild-type N2 animals in stress. In summary, this research showed the importance of both GRKs, especially GRK2, in modifying oxidative stress resistance.

Keywords: Aging, Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans), G protein coupled receptor kinase (GRK), Oxidative stress, Resistance, Stress response

Introduction

Oxidative stress is the result of the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can cause damage to tissues and cells. The abilities of the organism to deal with this stress, by minimizing the free oxygen radical effects and repairing its damage, are important, for not only its survival but also the development of a variety of different diseases (Sies 2015). Some research in oxidative stress, for instance, focuses on its role in heart disease, where oxidative stress is key in ischemia-reperfusion–related injuries (Sinning et al. 2017). Others analyze its role in neurodegenerative diseases (Uttara et al. 2009), like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, as well as other ailments in which oxidative stress can play a role in its development, like rheumatoid arthritis and cancer (Pham-Huy et al. 2008).

The model organism, Caenorhabditis (C.) elegans, has proven valuable in understanding stress responses elicited by toxicological agents (Dengg and van Meel 2004; Leung et al. 2008). This model organism has also been used to determine oxidative stress responses (Vanfleteren 1993), antioxidant effects (Gems and Doonan 2009), and elucidating processes that control oxidative stress resistance (Miranda-Vizuete and Veal 2017). These underlying molecular mechanisms and pathways that moderate oxidative stress resistance in C. elegans are of interest to study because of their potential applicability to human diseases. Typically, in C. elegans, oxidative responses are controlled by detoxifying proteins like superoxide dismutase (Doonan et al. 2008; Miranda-Vizuete and Veal 2017) and a number of different cell survival pathways—the most notable of which is the insulin growth factor (IGF)/insulin-like signaling (IIS) pathway (Rodriguez et al. 2013). When the IIS pathway is inactivated, such as when the animal is exposed to oxidative stress, the transcription factor DAF-16 is retained in the nucleus to increase the transcription of stress response genes (Murphy and Hu 2013). This inactivation of the IIS pathway also mediates increased nuclear localization of the transcription factor SKN-1 as well (Miranda-Vizuete and Veal 2017). Combined, these gene transcription events lead to increased stress resistance (Miranda-Vizuete and Veal 2017). The human ortholog of DAF-16, FOXO, is associated with human aging, cancer, and cardiovascular diseases (Imae et al. 2003).

One family of protein kinases, which could be involved in the IIS pathway, is the G protein–coupled receptor kinases (GRKs). Originally, these kinases were only thought to phosphorylate activated forms of G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs), leading to receptor desensitization and internalization (Moore et al. 2007). However, GRKs can also phosphorylate a number of non-GPCR proteins involved in a variety of different processes such as synucleins (Pronin et al. 2000), tubulin (Carman et al. 1998), β-Arrestin 1 (Barthet et al. 2009), Hip (Barker and Benovic 2011), p53 (Chen et al. 2010), phosducin (Ruiz-Gomez et al. 2000), DREAM (Ruiz-Gomez et al. 2007), p38 (Peregrin et al. 2006), IKBα (Patial et al. 2009), ezrin (Cant and Pitcher 2005), NFκβ1 (Parameswaran et al. 2006), MST-2 (So et al. 2013), moesin (Chakraborty et al. 2014), and histone deacetylases-5 (Martini et al. 2008) and -6 (Lagman et al. 2019). GRKs also control non-GPCR signaling pathways (Gao et al. 2005; Peppel et al. 2000; Steury et al. 2017) like those linked to insulin growth factor-1 (IGF1) receptors (Wei et al. 2012; Wei et al. 2013; Zheng et al. 2012). Since this latter pathway is conserved in C. elegans as the non-GPCR-related IIS pathway, this suggests that C. elegans GRKs can also modify this signaling pathway. Furthermore, mammalian GRKs have been shown to interact with mammalian orthologs within this non-GPCR pathway, such as AKT (Liu et al. 2005) and IGF1 receptors (Ma et al. 2016). Overexpression of GRK2 inhibits IGF1 receptor signaling in mammals, suggesting this kinase plays a restrictive role in insulin receptor signaling (Abubaker et al. 2014).

Since GRKs may have a wider array of cellular functions than originally expected and that they can potentially control the IIS pathway in C. elegans, it is of interest to explore non-GPCR-associated functions of GRKs in this model organism. There are two GRK homologs in the organism, representing 2 of the 3 major subclasses of GRKs found in humans—C. elegans (Ce-) GRK1 and Ce-GRK2—representing the human GRK4–6 and GRK2–3 subclasses, respectively. Ce-GRKs are involved in certain processes in C. elegans, such as egg laying (Wang et al. 2017), the detection of certain chemotactic agents (Fukuto et al. 2004), dopamine receptor signaling (Wani et al. 2012), NaCl avoidance (Hukema et al. 2006), and circadium rhythm control (Olmedo et al. 2012). However, their ability to modify stress responses in this animal has not been reported. This may be important since GRK protein expression levels do vary in a variety of human diseases (Iaccarino et al. 2005; Nogues et al. 2016; Obrenovich et al. 2009) and, at least in cancer cells, this protein expression level may dictate chemotherapeutic sensitivity (Lagman et al. 2019; So et al. 2012). This observation in cancer cells suggests that GRK may be able to modify cell stress behaviors.

In this report, the reactions of C. elegans without functioning Ce-GRK1 or Ce-GRK2 to oxidative stress are examined. In these experiments, C. elegans were exposed to acute oxidative stress from the oxidant juglone, querying for survival, and chronic low oxidative stress from the more stable oxidant, paraquat, testing for its effects on longevity. We observed loss-of-function grk-2 animals are more resistant to acute oxidative stress compared with grk-1 and wild-type N2 animals. These effects are potentially through the IIS pathway, with Ce-GRK2 interacting with Ce-AKT-1. Furthermore, the GRK2 inhibitor, the anti-depressant paroxetine, significantly improved acute oxidative stress resistance compared with the anti-depressant, non-GRK2 inhibitor, fluoxetine when the wild-type N2 animal was pre-treated with either drug prior to exposure to acute oxidative stress. In longevity studies, both loss of function grk-1 and grk-2 animals lived longer in chronic oxidative stress.

Methods

General methods and strains

All animals were cultivated using standard methods (Stiernagle 2006). The grk-1 + grk-2 loss-of-function animal was a generous gift from Drs. Jianjun Wang and Jeffrey Benovic (Thomas Jefferson University). All other strains were received from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC), which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure programs (P40 OD010440).

Acute oxidative stress experiments

For all acute oxidative stress experiments, worm populations were first synchronized by the alkaline hypochlorite method (Stiernagle 2006). Approximately 60-100 L4-staged animals were then plated on NGM plates made with 0–300 μM juglone with freshly seeded OP50 lawns, as performed previously (Senchuk et al. 2017). Survival was then assessed every hour up to 4 h. A worm responding to touch would be recorded as responsive. Percent responsive was calculated as the number of animals responding to touch over total number of animals on each plate. For paroxetine or fluoxetine treatment experiments, 60–100 L2-staged animals were placed on NGM plates treated with fluoxetine or paroxetine with a freshly seeded OP50 lawn. The animals were then allowed to grow for 24 h to reach L4/young adult stage. The animals were then pipetted onto NGM plates with varying concentrations of juglone, as performed previously (Senchuk et al. 2017) and responsiveness assayed every hour up to 3 h.

Lifespan analysis

All lifespan assays were performed at 22 °C. A total of 150–200 unstressed or stressed L4-staged animals were collected and placed onto a new NGM plate supplemented with 40 μM 5-Fluoro-2′ deoxyuridine (FUDR), with or without either 4- or 20 mM paraquat, and seeded with a fresh OP50 lawn. The animals were then examined every day for touch-provoked movement for the remainder of their lifespan.

Western blotting

Western blotting procedures were similar to that used previously (Wang et al. 2017). Anti-GRK2–3 (for detection of Ce- GRK2) and anti-GRK4–6 (for detection of Ce- GRK1) antibodies were purchased from EMD-Millipore (Temecula, CA). Antibodies were able to detect Ce-GRKs because they were developed against human GRK antigens that were homologous to their C. elegans counterparts.

RNAi clones

Ce-GRK1 and Ce-GRK2 RNAi, part of the Ahringer C. elegans RNAi collection, were obtained from Source Bioscience (Nottingham, UK). They were handled according to suggested feeding directions (Kamath et al. 2001) and grown on NGM feeding plates supplemented with 25 μg/ml carbenicillin and 1 μM IPTG. L1/L2-staged transgenic animals were grown on these NGM/carbenicillin/IPTG feeding plates with dsRNA-expressing HT115 bacteria for 24 h prior to the experiment. Specific knockdown of Ce-GRKs was detected by immunoblotting.

DAF-16 GFP translocation assays

After 24-h dsRNA exposure, 30–50 dsRNA-treated, L4-staged animals were treated with 100 mM paraquat up to 6 h. After 8 h, the animals were collected by rinsing with water and pipetting, anesthetized with sodium azide, mounted on agar pads, and DAF-16-GFP was visualized by fluorescent microscopy with an AE31 elite inverted phase contrast microscope from Motic (Xiamen, China). DAF-16-GFP translocation from the cytoplasm to the nucleus within individual transgenic animals was categorized as either cytoplasmic or intermediate (cytoplasmic with some nuclear localization) DAF-16 distribution. The data was presented as % animals in each category, as done previously (Schafer et al. 2006; Zou et al. 2013).

Statistical analysis

One-way ANOVA, using Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test, and student t tests were used to calculate significance utilizing GraphPad Prism. Survival analysis of lifespan assays was calculated by Kaplan Meier analysis using both GraphPad Prism and the Online Application for Survival Analysis (OASIS) (Yang et al. 2011).

Results

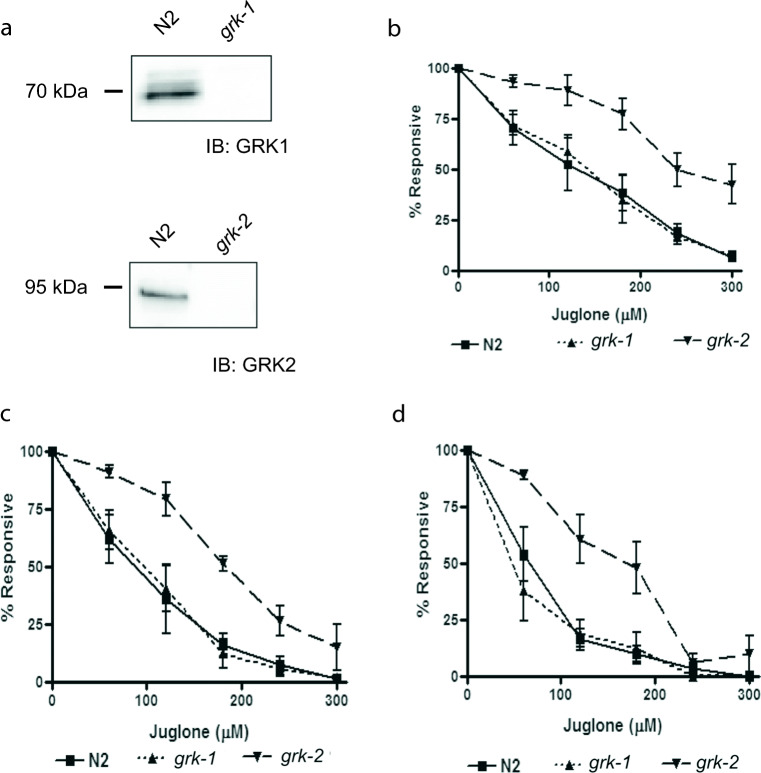

To determine the roles of GRKs in C. elegans, wild-type N2 and loss-of-function grk-1 and grk-2 animals (Fig. 1a) were treated to 0–300 μM juglone from 0 to 4 h (Fig. 1). At 1.2 or 4 h, grk-2 loss-of-function animals survived best at all concentrations of juglone tested (Fig. 1b–d). At 120 μM and 240 μM juglone for 0–4 h (Fig. 2 a and b), grk-2 loss-of-function animals showed increased survival at both concentrations of juglone compared with N2 and loss-of-function grk-1 animals.

Fig. 1.

Loss-of-function grk-2 animals show increased resistance to increasing oxidative stress exposure. a Protein expression of Ce-GRK1 and Ce-GRK2 in N2, loss-of-function grk-1 or grk-2 animals. b–d Responsiveness of N2, grk-1 or grk-2 animals after 1 (b, n = 6), 2 (c, n = 5) or 4-h exposure (d, n = 5) to 0–300 μM juglone

Fig. 2.

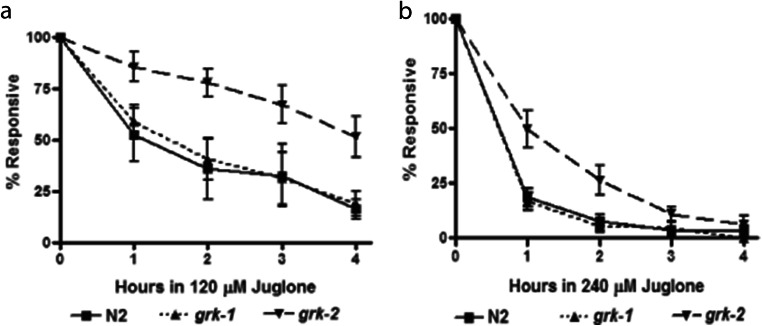

Loss of function grk-2 animals show increased resistance to oxidative stress exposure over time. a, b Responsiveness of N2, grk-1 or grk-2 animals after either 120 μM (a, n = 5) or 240 μM juglone (b, n = 5) exposure from 0 to 4 h

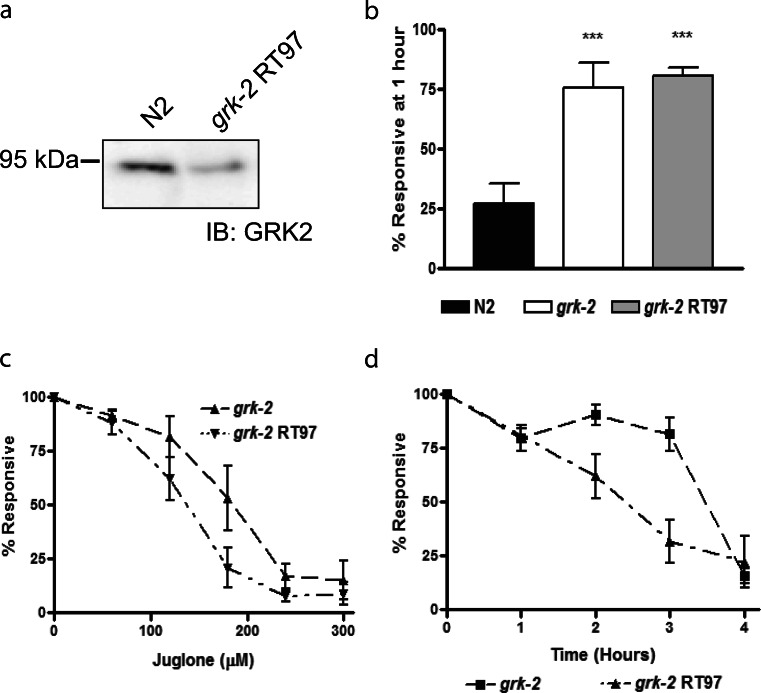

To evaluate if the effect of the loss of Ce- GRK2 is still consistent in a partial loss of function grk-2 animal, oxidative stress resistance was assessed in the partial Ce-GRK2 knockout animal, grk-2 RT97 (Fukuto et al. 2004) (Fig. 3). This animal showed 30% of the GRK2 expression compared with that of N2 wild-type animal (Fig. 3a). At the 1-h time point, grk-2 RT97 survived comparably to the full grk-2 loss-of-function animal at the 120 μM juglone concentration (Fig. 3b). However, this comparable resistance between the two does not continue for grk-2 RT97 at higher juglone concentrations and longer exposure times. Observing survival at 0–300 μM juglone at 2 h, we see that grk-2 RT97 animals did show resistance but not as well compared with grk-2 loss-of-function animal at the higher 180 μM juglone concentration (Fig. 3c). At 120 μM juglone from 0 to 4 h, even though we see equivalent oxidative stress resistance for both grk-2 animals tested at 1 h, also seen previously in Fig. 3b, we see that grk-2 loss-of-function animals survived better than the grk-2 RT97 animals at the longer 2- and 3-h time points (Fig. 3d). This difference in survival between the grk-2 RT97 animals and the complete loss-of-function grk-2 animals is because of the higher amount of Ce-GRK2 in the grk-2 RT97 animals, which makes these animals more sensitive to oxidative stress but still more resistant than that of the wild-type N2 animals.

Fig. 3.

Partial grk-2 knockout RT97 animals also show increased resistance to oxidative stress. a Protein expression of Ce-GRK2 in N2 and grk-2 RT97 animals. b Responsiveness of N2, grk-2 and grk-2 RT97 animals after 1-h exposure to 120 μM juglone (n = 5). ***p < 0.01 in using one-way ANOVA. c Responsiveness of grk-2 and grk-2 RT97 animals after 2-h exposure to 0–300 μM juglone (n = 5). d Responsiveness of grk-2 and grk-2 RT97 animals after 0–4 h treatment with 120 μM juglone (n = 4)

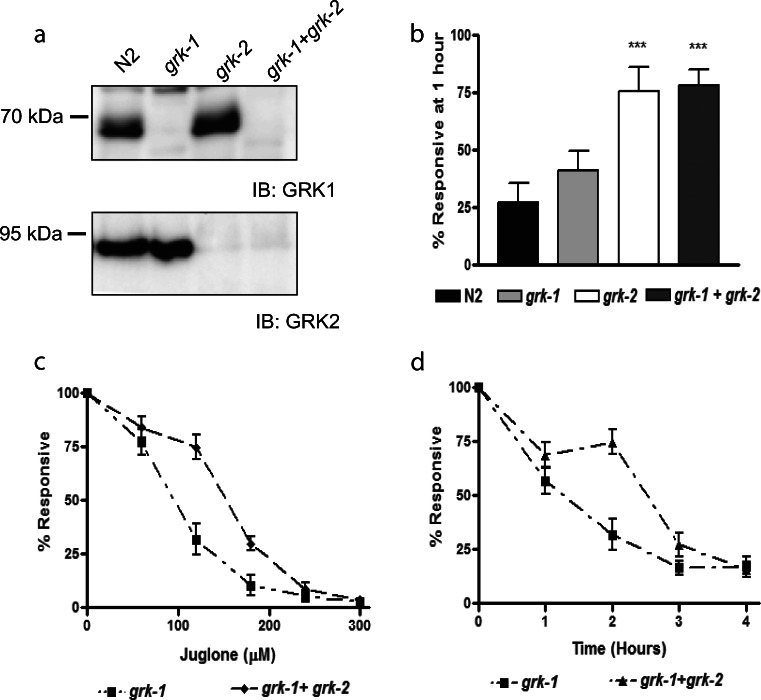

We wanted to next see if the effect of the loss of Ce-GRK2 protein expression in grk-2 animals can supersede that of Ce-GRK1. We tested the effect of losing the function of both Ce-GRK1 and Ce-GRK2 in a dual grk-1 + grk-2 loss-of-function animal (Fig. 4). The dual grk-1-grk-2 loss of function animal did not have Ce-GRK1 and Ce-GRK2 expressed (Fig. 4a). At the 1-h time point, dual grk-1 + grk-2 loss-of-function animal survived comparably with the full grk-2 loss-of-function animal at the 120 μM juglone concentration (Fig. 4b). Similar to the loss-of-function grk-2 animal, we observed that this animal also showed increased oxidative stress resistance when we queried oxidative stress survival in increasing juglone concentrations at 2 h (Fig. 4c) and in 0–4 h at 120 μM juglone (Fig. 4d) compared with the loss of function grk-1 animals.

Fig. 4.

Dual grk-1 and grk-2 loss-of-function animals show increased resistance to oxidative stress. a Expression of Ce-GRK1 and Ce-GRK2 in loss-of-function animals. b Responsiveness of N2, grk-1, grk-2, and grk-1+ grk-2 animals after 1-h exposure to 120 μM juglone (n = 4). ***p < 0.01 in using one-way ANOVA. c Responsiveness of grk-1 and grk-1 + grk-2 animals after 2-h exposure to 0–300 μM juglone (n = 5). d Responsiveness of grk-1 and grk-1 + grk-2 animals after 0–4 h treatment with 120 μM juglone (n = 5)

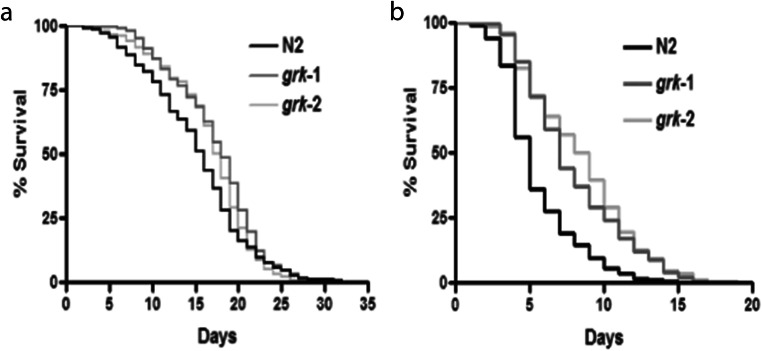

Next, we wanted to observe the effect of oxidative stress on C. elegans longevity (Fig. 5). We exposed wild-type N2 or the grk loss-of-function animals to either 0.5 mM (Fig. 5a; Table 1) or 4 mM paraquat (Fig. 5b; Table 1). We observed that at the lower 0.5 mM paraquat concentration, both the loss-of-function grk-1 and grk-2 animals showed increased survival compared with the wild-type N2 animals (Fig. 5a; Table 1). We also observed this at the higher 4 mM concentration of paraquat as well (Fig. 5b; Table 1). This suggests that both loss-of-function grk animals survived better in oxidative stress compared with the wild-type N2 animals.

Fig. 5.

Loss-of-function grk-2 animals show increased resistance to chronic oxidative stress exposure. Longevity of wild type N2 or loss of function grk-1 or grk-2 animals in 0.5 mM paraquat (a, n = 5) or 4 mM paraquat (b, n = 5)

Table 1.

Effect of oxidative stress on lifespan: experiments were performed at least 4 independent times (50–200 animals each experiment). Experiments were performed at 22 °C.

| Population | Median lifespan | Log rank (compared with untreated animals. p < 0.05 was considered significant) | Log rank (compared with N2-treated animals within treatment) | Maximum lifespan |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days | Days | |||

| N2 (n = 734) | 19.9 ± 0.24 | 34 | ||

|

N2 0.5 mM paraquat (n = 1384) |

15.21 ± 0.16 | p < 1.0 × 10−10 | 33 | |

|

N2 4 mM paraquat (n = 1320) |

5.52 ± 0.07 | p < 1.0 × 10−10 | 15 | |

| grk-1 (n = 654) | 19.04 ± 0.2 | 29 | ||

| grk-1 0.5 mM paraquat (n = 1120) | 17.35 ± 0.15 | p < 1.0 × 10−10 | p < 1.0 × 10−10 | 32 |

| grk-1 4 mM paraquat (n = 1334) | 7.9 ± 0.1 | p < 1.0 × 10−10 | p < 1.0 × 10−10 | 18 |

| grk-2 (n = 845) | 19.64 ± 0.18 | p < 1.0 × 10−10 | 33 | |

| grk-2 0.5 mM paraquat (n = 946) | 16.68 ± 0.16 | p < 1.0 × 10−10 | 0.0002 | 27 |

| grk-2 4 mM paraquat (n = 1044) | 8.4 ± 0.11 | p < 1.0 × 10−10 | p < 1.0 × 10−10 | 20 |

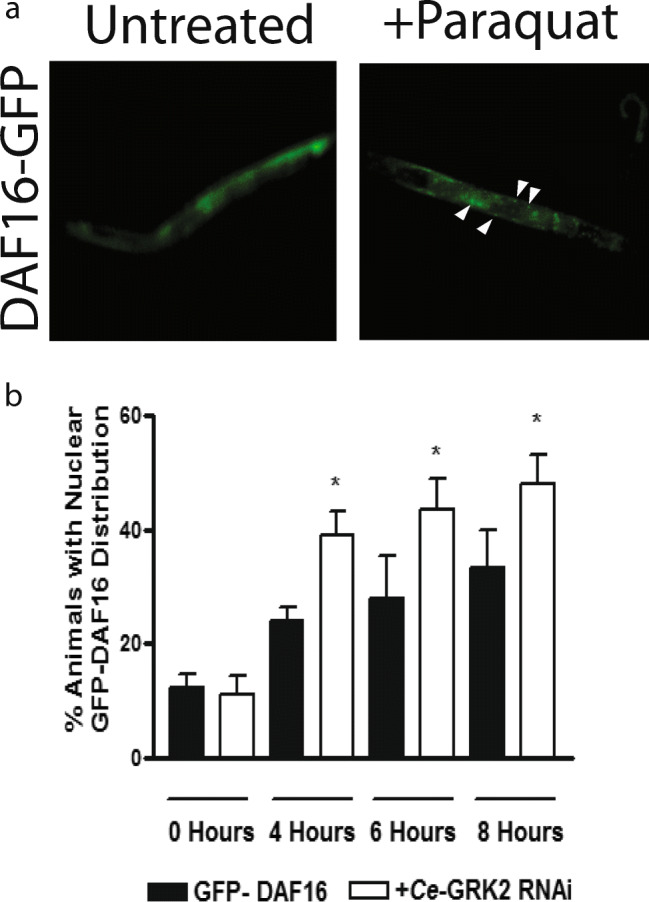

We next wanted to determine if the IIS pathway is inactivated, as indicated by increased nuclear localization of DAF-16, during oxidative stress and if this varies when the animal is treated with RNAi against Ce-GRK2 (Fig. 6). We chose 100 mM paraquat as the oxidant because it is more stable than juglone. With paraquat treatment for 8 h, we only saw some partial translocation of GFP-DAF-16 between the cytosol and the nucleus (Fig. 6a). We assessed GFP-DAF16 translocation as partial if both smooth (cytoplasmic) and punctate (nuclear) GFP-DAF16 distributions are observed. In GFP-DAF-16 animals without Ce-GRK2, because they were treated with Ce-GRK2 RNAi, we saw an increase in partial cytosolic-nuclear translocation of GFP-DAF-16 at the different time points tested up to 8 h compared with unfed GFP-DAF-16 animals (Fig. 6b). This suggests that IIS pathway is involved in this process.

Fig. 6.

Increased DAF-16 translocation from cytoplasm to nuclei in Ce-GRK2 RNAi fed GFP-DAF16 animals upon oxidative stress exposure. a Distribution of GFP-DAF-16, either in cytosol (left) or partially between cytosol and nuclei (right). Arrows indicate nucleus-localized GFP-DAF-16. b % animals showing partial cytosol/nuclei GFP-DAF-16 distribution after 0–8 h 100 mM paraquat exposure, n = 6. *p < 0.05 significant difference by Student t test between untreated and Ce-GRK2 RNAi treated GFP-DAF-16 animals at each time point

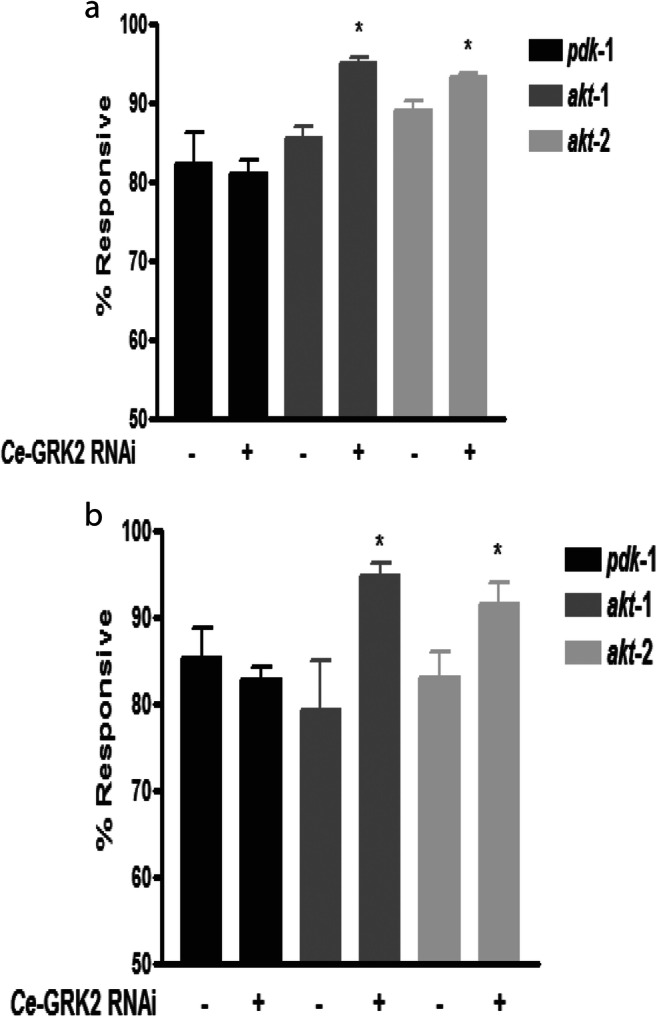

To determine which protein Ce-GRK2 interacts with within this pathway, we performed epistatic analysis using Ce-GRK2 RNAi on loss-of-function akt-1, akt-2, and pdk-1 animals (Fig. 7). At 120 μM at 2 h (Fig. 7a) and 240 μM juglone at 1 h (Fig. 7b), we observed increased survival of pdk-1 and akt-2 loss-of-function animals fed with Ce-GRK2 RNAi except for the akt-1 loss-of-function animals, whose survival was blunted by RNAi treatment. This suggests that Ce-AKT-1 is a key interactor of Ce-GRK2 to mediate oxidative stress resistance.

Fig. 7.

Ce-AKT-1 is a key mediator of the ability of Ce-GRK2 to modify oxidative stress resistance. a, b Oxidative stress responsiveness of loss-of-function akt-1, akt-2, or pdk-1 loss-of-function animals fed with Ce-GRK2 RNAi to 120 μM juglone at 2 h (a, n = 4) or 240 μM juglone for 1 h (b, n = 4). *p < 0.05 significant difference by Student t test between untreated and Ce-GRK2 RNAi treated transgenic (pdk-1, akt-1, or akt-2) animals

Since paroxetine is a weak GRK2 inhibitor (Thal et al. 2012), we wished to determine if paroxetine can mimic some of the effects of ablation of Ce-GRK2 protein expression in acute oxidative stress (Fig. 8). From 0 to 240 μM juglone at 1 or 2 h (Fig. 8 a and b), pre-treating wild-type N2 animals with 100 nM paroxetine, and not 100 nM fluoxetine, leads to increased oxidative stress resistance at the 120 μM juglone concentration at the 1- and 2-h marks (Fig. 8 a and b). When looking at hours treated with 120 (Fig. 8c) or 240 μM juglone (Fig. 8d), we also observed improved survival upon paroxetine pre-treatment, up to 3 h in 120 μM juglone (Fig. 8c) and only at 1 h in 240 μM juglone (Fig. 8d). Of note, similar results were observed in acute oxidative stress resistance comparing the effects of fluoxetine and paroxetine when the L2/L3 staged animals were pre-treated with the higher 10 μM concentrations of both drugs (data not shown), suggesting that fluoxetine may either mimic the effects of paroxetine at higher concentrations at GRK2 or may elicit other antioxidant effects, which has been reported previously (Bharti et al. 2020; Zafir and Banu 2007).

Fig. 8.

The GRK2 inhibitor paroxetine increased the oxidative stress resistance of C. elegans. L2/3-staged wild-type N2 C. elegans were pre-treated with either 100 nM fluoxetine or paroxetine for 24 h and then exposed to either increasing concentrations of juglone, with their responsiveness queried after 1- (a, n = 7) or 2-h 0–240 μM juglone (b, n = 7) treatment or either at a single concentration, either 120 μM (c, n = 7) or 240 μM (d, n = 7) of juglone, from 0 to 3 h

Discussion

In this report, we show Ce-GRKs modify oxidative stress resistance in C. elegans. In acute oxidative stress using juglone, loss-of-function grk-2 animals are more resistant to oxidative stress compared with wild-type N2 and loss-of-function grk-1 animals. In chronic oxidative stress studies, both grk-1 and grk-2 loss-of-function animals survived better at both paraquat concentrations tested. Ce-GRK2 may function through the IIS pathway, with the interaction between Ce-GRK2 and Ce-AKT-1 playing an integral role in modulating this oxidative stress activity. The GRK2 inhibitor paroxetine improves oxidative stress resistance compared with fluoxetine, which is not a GRK2 inhibitor, but, like paroxetine, is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, suggesting that inhibition of GRK2 helps in modifying oxidative stress responses in C. elegans.

Ce-GRK2 functions within the IIS pathway to modulate oxidative stress resistance. This pathway has been shown previously to mediate oxidative responses in this organism (Rodriguez et al. 2013). Ce-GRK2 seems to modify the IIS pathway activity by interacting with Ce-AKT-1 (Fig. 7), and this interaction makes the IIS pathway less likely to inactivate during the oxidative stress response. Without Ce-GRK2, however, Ce- AKT-1 may be more sensitive to inactivation, leading to DAF-16 nuclear translocation and improved survival to stress. In humans, GRK2-AKT-1 interactions have been identified to modify the insulin receptor pathway in humans (Kleibeuker et al. 2008; Zheng et al. 2012), and this signaling pathway has been shown to also mediate oxidative stress responses in humans (Dolado and Nebreda 2008). In addition to the IIS pathway, other GRK2 interactions in C. elegans may help oxidative resistance. For instance, this protein kinase in C. elegans may also modify other mechanisms that control oxidative responses (Miranda-Vizuete and Veal 2017). Furthermore, mammalian GRK2 is found in the mitochondria (Franco et al. 2018; Manfredi et al. 2019; Sato et al. 2018; Theccanat et al. 2016). In cardiomyocytes, elevated GRK2 protein expression increases superoxide levels (Sato et al. 2015). Whether C. elegans GRK2 also has this function is unclear.

Loss-of-function grk-2 animals are more resistant to oxidative stress as shown in Fig. 1. This may imply that in mammalian cells with lower or no GRK2 subclass protein expression, either GRK2 or GRK3 may display increased resistance to oxidative stress. This could be of interest to diseases associated with increased mammalian GRK2 expression, such as heart failure, where GRK2 expression levels are increased (Iaccarino et al. 2005) and Alzheimer’s disease (Obrenovich et al. 2009; Obrenovich et al. 2006), where GRK2 overexpression is associated with mitochondrial lesions. Combined with our observation in C. elegans, this increased GRK2 protein expression may prone these systems to damage from this type of stress. In heart failure, for instance, when increased ROS are abundant, increased GRK2 protein expression may lead to both increased susceptibility to tissue damage as well as decreased β adrenergic receptor signaling, unrelated to ROS, due to increased receptor phosphorylation by GRK2 (Iaccarino et al. 2005). Combined, this may contribute to the further pathophysiology of heart failure, where the heart is both continually damaged by ROS and cannot respond to norepinephrine, which is part of the sympathetic drive. Therefore, some degree of GRK2 inhibition may play a dual role in preserving heart function by both allowing adrenergic receptor signaling as well as helping initiate mechanisms to increase oxidative stress resistance. The GRK2 inhibitor, paroxetine, may mediate this since this drug is shown in our study to increase oxidative stress resistance compared with fluoxetine, which is not a GRK2 inhibitor but has SSRI activity. Some studies have shown that paroxetine can improve cardiovascular function within heart failure (Gottlieb et al. 2007; Powell et al. 2017; Schumacher et al. 2015; Sorriento et al. 2016).

Conclusions

In summary, Ce-GRK2 modifies oxidative resistance in C. elegans. Without Ce- GRK2, this animal becomes more resistant to oxidative damage, allowing for improved survival and longevity under stressful conditions. This result suggests the importance of GRK2 in oxidative stress responses, therefore proposing this protein kinase as a biomarker for diseases associated with oxidative stress as well as the utility of a GRK2 inhibitor, like paroxetine, to increase resistance of organs to oxidative stress damage. Since this effect is controlled by the IIS pathway, a non-GPCR signaling cascade, this advocates for the importance of the non-canonical GRK functions in overall cell communications and survival. Therefore, continued identification of new pathways associated with GRKs may be critical to fully understand the function of this protein kinase family in cells and diseases beyond just regulating GPCR signaling.

Acknowledgments

We like to thank David Rawlins for his help on the data analysis and Christian Heine, Deniz Alp, and Murat Alp for the critical review of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- GRK

G protein–coupled receptor kinases

- GPCR

G protein–coupled receptors

- Ce

Caenorhabditis Elegans

- IGF

insulin-like growth factor

- IIS

IGF/insulin-like signaling

Footnotes

Stacy A. Henry, Tina M. Nguyen and Selina Crivello shared 1st authorship

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abubaker K, et al. Targeted disruption of the JAK2/STAT3 pathway in combination with systemic administration of paclitaxel inhibits the priming of ovarian cancer stem cells leading to a reduced tumor burden front. Oncol. 2014;4:75. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker BL, Benovic JL. G protein-coupled receptor kinase 5 phosphorylation of hip regulates internalization of the chemokine receptor CXCR4. Biochemistry. 2011;50:6933–6941. doi: 10.1021/bi2005202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barthet G, et al. Beta-arrestin1 phosphorylation by GRK5 regulates G protein-independent 5-HT4 receptor signalling. EMBO J. 2009;28:2706–2718. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharti V, Tan H, Deol J, Wu Z, Wang J-F (2020) Upregulation of antioxidant thioredoxin by antidepressants fluoxetine and venlafaxine Psychopharmacology 237:127–136 doi:10.1007/s00213-019-05350-9 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cant SH, Pitcher JA. G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2-mediated phosphorylation of ezrin is required for G protein-coupled receptor-dependent reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:3088–3099. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-10-0877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carman CV, Som T, Kim CM, Benovic JL. Binding and phosphorylation of tubulin by G protein-coupled receptor kinases. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:20308–20316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty PK, et al. G protein-coupled receptor kinase GRK5 phosphorylates moesin and regulates metastasis in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2014;74:3489–3500. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Zhu H, Yuan M, Fu J, Zhou Y, Ma L. G-protein-coupled receptor kinase 5 phosphorylates p53 and inhibits DNA damage-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:12823–12830. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.094243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dengg M, van Meel JC. Caenorhabditis elegans as model system for rapid toxicity assessment of pharmaceutical compounds. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2004;50:209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolado I, Nebreda AR. AKT and oxidative stress team up to kill cancer cells. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:427–429. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doonan R, et al. Against the oxidative damage theory of aging: superoxide dismutases protect against oxidative stress but have little or no effect on life span in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Dev. 2008;22:3236–3241. doi: 10.1101/gad.504808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco A, et al. GRK2 moderates the acute mitochondrial damage to ionizing radiation exposure by promoting mitochondrial fission/fusion. Cell Death Dis. 2018;4:25. doi: 10.1038/s41420-018-0028-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuto HS et al. (2004) G protein-coupled receptor kinase function is essential for chemosensation in C. elegans Neuron 42:581-593 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gao J, Li J, Chen Y, Ma L. Activation of tyrosine kinase of EGFR induces Gbetagamma-dependent GRK-EGFR complex formation. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:122–126. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gems D, Doonan R. Antioxidant defense and aging in C. elegans: is the oxidative damage theory of aging wrong? Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1681–1687. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.11.8595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb SS, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study of controlled-release paroxetine on depression and quality of life in chronic heart failure. Am Heart J. 2007;153:868–873. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hukema RK, Rademakers S, Dekkers MP, Burghoorn J, Jansen G (2006) Antagonistic sensory cues generate gustatory plasticity in Caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO J 25:312–322. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Iaccarino G, et al. Elevated myocardial and lymphocyte GRK2 expression and activity in human heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:1752–1758. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imae M, Fu Z, Yoshida A, Noguchi T, Kato H. Nutritional and hormonal factors control the gene expression of FoxOs, the mammalian homologues of DAF-16. J Mol Endocrinol. 2003;30:253–262. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0300253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath RS, Martinez-Campos M, Zipperlen P, Fraser AG, Ahringer J. Effectiveness of specific RNA-mediated interference through ingested double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genome Biol. 2001;2:Research0002. doi: 10.1186/gb-2000-2-1-research0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleibeuker W, Jurado-Pueyo M, Murga C, Eijkelkamp N, Mayor F, Jr, Heijnen CJ, Kavelaars A. Physiological changes in GRK2 regulate CCL2-induced signaling to ERK1/2 and Akt but not to MEK1/2 and calcium. J Neurochem. 2008;104:979–992. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagman J, et al. G protein-coupled receptor kinase 5 modifies cancer cell resistance to paclitaxel. Mol Cell Biochem. 2019;461:103–118. doi: 10.1007/s11010-019-03594-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung MC, Williams PL, Benedetto A, Au C, Helmcke KJ, Aschner M, Meyer JN. Caenorhabditis elegans: an emerging model in biomedical and environmental toxicology. Toxicol Sci. 2008;106:5–28. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Premont RT, Kontos CD, Zhu S, Rockey DC. A crucial role for GRK2 in regulation of endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase function in portal hypertension. Nat Med. 2005;11:952–958. doi: 10.1038/nm1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Han CC, Huang Q, Sun WY, Wei W. GRK2 overexpression inhibits IGF1-induced proliferation and migration of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells by downregulating EGR1. Oncol Rep. 2016;35:3068–3074. doi: 10.3892/or.2016.4641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manfredi LH, Ang J, Peker N, Dagda RK, McFarlane C. G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 regulates mitochondrial bioenergetics and impairs myostatin-mediated autophagy in muscle cells. Am J Phys Cell Phys. 2019;317:C674–c686. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00516.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martini JS, et al. Uncovering G protein-coupled receptor kinase-5 as a histone deacetylase kinase in the nucleus of cardiomyocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:12457–12462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803153105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda-Vizuete A, Veal EA. Caenorhabditis elegans as a model for understanding ROS function in physiology and disease. Redox Biol. 2017;11:708–714. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2016.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore CA, Milano SK, Benovic JL. Regulation of receptor trafficking by GRKs and arrestins. Annu Rev Physiol. 2007;69:451–482. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.022405.154712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CT, Hu PJ. WormBook : the online review of C elegans biology. 2013. Insulin/insulin-like growth factor signaling in C. elegans; pp. 1–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogues L, et al. G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2) promotes breast tumorigenesis through a HDAC6-Pin1 axis. EBioMedicine. 2016;13:132–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obrenovich ME, Smith MA, Siedlak SL, Chen SG, De La Torre JC, Perry G, Aliev G. Overexpression of GRK2 in alzheimer disease and in a chronic hypoperfusion rat model is an early marker of brain mitochondrial lesions. Neurotox Res. 2006;10:43–56. doi: 10.1007/BF03033333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obrenovich ME, Palacios HH, Gasimov E, Leszek J, Aliev G. The GRK2 overexpression is a primary Hallmark of mitochondrial lesions during early Alzheimer disease. Cardiovasc Psychiatry Neurol. 2009;2009:327360. doi: 10.1155/2009/327360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmedo M, O'Neill JS, Edgar RS, Valekunja UK, Reddy AB, Merrow M. Circadian regulation of olfaction and an evolutionarily conserved, nontranscriptional marker in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:20479–20484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211705109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parameswaran N, Pao CS, Leonhard KS, Kang DS, Kratz M, Ley SC, Benovic JL. Arrestin-2 and G protein-coupled receptor kinase 5 interact with NFkappaB1 p105 and negatively regulate lipopolysaccharide-stimulated ERK1/2 activation in macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:34159–34170. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605376200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patial S, Luo J, Porter KJ, Benovic JL, Parameswaran N. G-protein-coupled-receptor kinases mediate TNFalpha-induced NFkappaB signalling via direct interaction with and phosphorylation of IkappaBalpha. Biochem J. 2009;425:169–178. doi: 10.1042/bj20090908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peppel K, Jacobson A, Huang X, Murray JP, Oppermann M, Freedman NJ. Overexpression of G protein-coupled receptor kinase-2 in smooth muscle cells attenuates mitogenic signaling via G protein-coupled and platelet-derived growth factor receptors. Circulation. 2000;102:793–799. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.102.7.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peregrin S, et al. Phosphorylation of p38 by GRK2 at the docking groove unveils a novel mechanism for inactivating p38MAPK. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2042–2047. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham-Huy LA, He H, Pham-Huy C. Free radicals, antioxidants in disease and health. Int J Biomed Sci. 2008;4:89–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell JM, Ebin E, Borzak S, Lymperopoulos A, Hennekens CH. Hypothesis: paroxetine, a G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2) inhibitor reduces morbidity and mortality in patients with heart failure. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2017;22:51–53. doi: 10.1177/1074248416644350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pronin AN, Morris AJ, Surguchov A, Benovic JL. Synucleins are a novel class of substrates for G protein-coupled receptor kinases. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26515–26522. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003542200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez M, Snoek LB, De Bono M, Kammenga JE. Worms under stress: C. elegans stress response and its relevance to complex human disease and aging. Trends Genet. 2013;29:367–374. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Gomez A, Humrich J, Murga C, Quitterer U, Lohse MJ, Mayor F., Jr Phosphorylation of phosducin and phosducin-like protein by G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:29724–29730. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001864200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Gomez A, et al. G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2-mediated phosphorylation of downstream regulatory element antagonist modulator regulates membrane trafficking of Kv4.2 potassium channel. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:1205–1215. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607166200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato PY, Chuprun JK, Ibetti J, Cannavo A, Drosatos K, Elrod JW, Koch WJ. GRK2 compromises cardiomyocyte mitochondrial function by diminishing fatty acid-mediated oxygen consumption and increasing superoxide levels. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015;89:360–364. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato PY, et al. Restricting mitochondrial GRK2 post-ischemia confers cardioprotection by reducing myocyte death and maintaining glucose oxidation. Sci Signal. 2018;11:eaau0144. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aau0144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JC, Winkelbauer ME, Williams CL, Haycraft CJ, Desmond RA, Yoder BK. IFTA-2 is a conserved cilia protein involved in pathways regulating longevity and dauer formation in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:4088–4100. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher SM, et al. Paroxetine-mediated GRK2 inhibition reverses cardiac dysfunction and remodeling after myocardial infarction. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:277ra231. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa0154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senchuk MM, Dues DJ, Van Raamsdonk JM. Measuring oxidative stress in Caenorhabditis elegans: paraquat and juglone sensitivity assays. Bio Protoc. 2017;7:e2086. doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sies H. Oxidative stress: a concept in redox biology and medicine. Redox Biol. 2015;4:180–183. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinning C, Westermann D, Clemmensen P. Oxidative stress in ischemia and reperfusion: current concepts, novel ideas and future perspectives. Biomark Med. 2017;11:11031–11040. doi: 10.2217/bmm-2017-0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So CH, Michal AM, Mashayekhi R, Benovic JL. G protein-coupled receptor kinase 5 phosphorylates nucleophosmin and regulates cell sensitivity to polo-like kinase 1 inhibition. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:17088–17099. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.353854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So CH, Michal A, Komolov KE, Luo J, Benovic JL. G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2) is localized to centrosomes and mediates epidermal growth factor-promoted centrosomal separation. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24:2795–2806. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-01-0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorriento D, Ciccarelli M, Cipolletta E, Trimarco B, Iaccarino G. “Freeze, don’t move”: how to arrest a suspect in heart failure - a review on available GRK2 inhibitors. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2016;3:48. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2016.00048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steury MD, Lucas PC, McCabe LR, Parameswaran N. G-protein-coupled receptor kinase-2 is a critical regulator of TNFalpha signaling in colon epithelial cells. Biochem J. 2017;474:2301–2313. doi: 10.1042/bcj20170093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiernagle T. WormBook : the online review of C elegans biology. 2006. Maintenance of C. elegans; pp. 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thal DM, et al. Paroxetine is a direct inhibitor of g protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 and increases myocardial contractility. ACS Chem Biol. 2012;7:1830–1839. doi: 10.1021/cb3003013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theccanat T, Philip JL, Razzaque AM, Ludmer N, Li J, Xu X, Akhter SA. Regulation of cellular oxidative stress and apoptosis by G protein-coupled receptor kinase-2; the role of NADPH oxidase 4. Cell Signal. 2016;28:190–203. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2015.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uttara B, Singh AV, Zamboni P, Mahajan RT. Oxidative stress and neurodegenerative diseases: a review of upstream and downstream antioxidant therapeutic options. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2009;7:65–74. doi: 10.2174/157015909787602823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanfleteren JR. Oxidative stress and ageing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Biochem J. 1993;292(Pt 2):605–608. doi: 10.1042/bj2920605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Luo J, Aryal DK, Wetsel WC, Nass R, Benovic JL. G protein-coupled receptor kinase-2 (GRK-2) regulates serotonin metabolism through the monoamine oxidase AMX-2 in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:5943–5956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.760850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wani KA, Catanese M, Normantowicz R, Herd M, Maher KN, Chase DL. D1 dopamine receptor signaling is modulated by the R7 RGS protein EAT-16 and the R7 binding protein RSBP-1 in Caenoerhabditis elegans motor neurons. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37831. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Z, Hurtt R, Ciccarelli M, Koch WJ, Doria C. Growth inhibition of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells by overexpression of G-protein-coupled receptor kinase 2. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227:2371–2377. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Z, Hurtt R, Gu T, Bodzin AS, Koch WJ, Doria C. GRK2 negatively regulates IGF-1R signaling pathway and cyclins' expression in HepG2 cells. J Cell Physiol. 2013;228:1897–1901. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JS, Nam HJ, Seo M, Han SK, Choi Y, Nam HG, Lee SJ, Kim S. OASIS: online application for the survival analysis of lifespan assays performed in aging research. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23525. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zafir A, Banu N. Antioxidant potential of fluoxetine in comparison to Curcuma longa in restraint-stressed rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;572:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H, Worrall C, Shen H, Issad T, Seregard S, Girnita A, Girnita L. Selective recruitment of G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) controls signaling of the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:7055–7060. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118359109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou CG, Tu Q, Niu J, Ji XL, Zhang KQ. The DAF-16/FOXO transcription factor functions as a regulator of epidermal innate immunity. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003660. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]