Abstract

Sexual aggression perpetration is a public health epidemic, and burgeoning research aims to delineate risk factors for individuals who perpetrate completed rape. The current study investigated physical and psychological intimate partner violence (IPV) history, coercive condom use resistance (CUR), and heavy episodic drinking (HED) as prospective risk factors for rape perpetration. Young adult men (N = 430) ages 21–30 completed background measures as well as follow-up assessments regarding rape events perpetrated over the course of three months. Negative binomial regression with log link function was utilized to examine whether these risk factors interacted to prospectively predict completed rape. There was a significant interaction between physical IPV and HED predicting completed rape; men with high HED and greater physical IPV histories perpetrated more completed rapes during follow-up than men with low HED at the same level of physical IPV. Moreover, psychological IPV and coercive CUR interacted to predict completed rape such that men with high coercive CUR and greater psychological IPV histories perpetrated more completed rapes throughout the follow-up period than men with low coercive CUR at the same level of psychological IPV. Findings suggest targets for intervention efforts and highlight the need to understand the topography of different forms of aggression perpetration.

Keywords: intimate partner violence, condom use resistance, heavy drinking, rape, alcohol

Sexual aggression is a public health epidemic; on average, there are approximately 322,000 victims of sexual aggression each year in the United States (Department of Justice, 2015). Sexual aggression is an inclusive term which refers to a range of sex acts that one individual may inflict on another, including nonconsensual sexual contact (i.e., kissing, touching), attempted rape, and completed rape (Koss, Heise, & Russo, 1994). Completed rape is defined in the U.S. as nonconsensual vaginal, oral, or anal penetration obtained through a variety of tactics including verbal coercion, force, threat of force, or when the victim is incapacitated or otherwise unable to give consent (Abbey & McAuslan, 2004). Victims of completed rape overwhelmingly identify as female; approximately 1 out of 6 American women report lifetime victimization through completed rape and most individuals who perpetrate are men (National Institute of Justice, 2006; RAINN, 2017). Consequences for survivors are myriad and may include post-traumatic stress disorder, substance abuse, anxiety, depression, emotional distress, and increased risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (National Institute of Justice, 2006). Whereas past studies have defined sexual aggression perpetration broadly to include sexual contact and/or attempted and completed rape (Abbey, Wegner, Woerner, Pegram, & Pierce, 2014; Jewkes, Nduna, Shai, & Dunkle, 2012; Voller & Long, 2010), few have assessed predictors of completed rape perpetration specifically (Loh, Gidycz, Lobo, & Luthra, 2005). Not only do individuals who experience completed rape demonstrate more severe psychological outcomes (Ullman, Townsend, Filipas, & Starzynski, 2007), individuals who perpetrate completed rape are also more likely to be sexually aggressive in the future (Loh et al., 2005). Thus, the present study sought to prospectively examine risk factors for completed rape events including intimate partner violence (IPV) history, coercive condom use resistance (CUR) history, and heavy drinking.

IPV History and Completed Rape

Physical IPV includes any action of physical violence against a partner, such as hitting, kicking, or throwing objects (Murphy & O’Leary, 1989), whereas psychological IPV refers to any non-physical act intended to harm a partner, and typically involves manipulation or verbal insults (Jenkins & Aubé, 2002; White & Koss, 1991). Individuals who perpetrate IPV are likely to perpetrate other forms of aggression and many types of IPV are intercorrelated (Grych & Swan, 2012; Hamby & Grych, 2013). However, aggression research often occurs in silos (Hamby, 2014; Hamby & Grych, 2013); thus, most studies have examined physical and psychological IPV perpetration separately from sexual aggression perpetration, including completed rape. The implications of siloed research are vast, resulting in restricted progress in understanding why some individuals are at greater risk for perpetrating sexual aggression and constraining integrated interventions for people who perpetrate violence (Grych & Swan, 2012). Moreover, most research investigating IPV history and rape has been cross-sectional or retrospective, limiting conclusions about the predictive nature of these forms of aggression.

One investigation by Raj and colleagues (2006) found that men who perpetrated IPV in the past year were significantly more likely to report forcing sexual intercourse without a condom. However, a cross-sectional design and a composite measure of physical and sexual IPV perpetration limited conclusions about the influence of either form of IPV. Other studies (Basile & Hall, 2011; Tjaden & Thoennes, 2000) have noted strong correlations between physical IPV and psychological IPV as well as physical IPV and sexual aggression more broadly, though none have examined completed rape specifically. Indeed, physical and psychological IPV have rarely been examined as predictors of subsequent sexual aggression. However, given that individuals may escalate the severity of IPV acts over time (Barnham, Barnes, & Sherman, 2017; Walker, 2006), these behaviors are important to assess as risk factors. Thus, the present study aims to provide a more comprehensive understanding of predictors of completed rape events by prospectively examining the effects of prior physical and psychological IPV.

Coercive CUR and Completed Rape

Men higher in sexual risk behavior are also more likely to be aggressive (for a review, see Davis, Neilson, Wegner, & Danube, 2018b). Sexual risk behavior refers to any sexual behavior that increases one’s risk of a negative health outcome, such as contracting or transmitting an infection or experiencing unwanted pregnancy (Davis et al., 2018b). One behavior that represents the nexus of sexual risk and violence is coercive condom use resistance (CUR). CUR – successful attempts to avoid using a condom with a partner who wants to use one (Davis et al., 2014a) – includes both non-coercive and coercive tactics (Davis et al., 2014a; 2014b). Coercive CUR involves the use of aggressive or manipulative tactics to avoid using a condom and is intended to constrain the partner’s agency and ability to make an informed and consensual decision (Davis et al., 2014a). Examples of coercive CUR tactics include emotional manipulation (e.g., telling a woman how angry one would be if a condom was used during intercourse), deception (e.g., pretending to have been tested and not having any STIs), and stealthing (e.g., secretly removing a condom before or during intercourse). Past research has demonstrated that 42% of non-problem drinking men have utilized at least one coercive CUR tactic since adolescence (Davis, 2018). Due to its conceptual and behavioral overlap with sexual aggression (Davis et al., 2018b), coercive CUR is the focus of the present study.

Men typically exercise more control than their female partners over whether a condom is used during intercourse (Bowleg, Lucas, & Tschann, 2004; Kennedy, Nolen, Applewhite, & Waiter, 2007). As such, CUR may occur in situations that begin as consensual; however, these circumstances may become non-consensual over issues of condom negotiation. Sexual aggression and completed rape specifically may or may not involve CUR. Nonetheless, there is a well-documented and robust association between men’s sexual risk behavior, such as CUR, and sexual aggression (Davis et al., 2018b; Peterson, Janssen, & Heiman, 2010). Research indicates that completed rape often does not involve condom use (Davis et al., 2012), and men with sexual aggression histories felt more justified utilizing coercion to obtain condomless sex than men without such histories (Abbey, Parkhill, Jacques-Tiura, & Saenz, 2009). Men’s sexual aggression severity also indirectly predicted coercive CUR intentions through feelings of power and control (Davis, Gulati, Neilson, & Stappenbeck, 2018a).

Despite this knowledge, no research to date has examined coercive CUR history as a prospective predictor of completed rape. It is possible that men with histories of using aggression and manipulation to forgo condom use may continue to engage in sexually aggressive behavior or increase the severity of their aggressive behavior over time (Thompson, Swartout, & Koss, 2013). Additionally, men with physical or psychological IPV histories who also engage in coercive CUR may be at increased risk for perpetrating completed rape. Coercive CUR tactics are conceptually similar to the strategies individuals use to perpetrate psychological and physical IPV as well as sexual aggression (e.g., physical force, emotional manipulation, deception), and aggression perpetration broadly is often characterized by difficulty inhibiting or regulating one’s actions (DeWall, Baumeister, Stillman, & Gailliot, 2007; Finkel, 2007). Consequently, an individual who has perpetrated psychological or physical IPV, as well as coercive CUR, may be more likely to perpetrate completed rape.

Heavy Drinking and Completed Rape

Alcohol has long been recognized as a risk factor for sexual aggression perpetration, particularly at higher consumption levels (Abbey, 2002; Abbey et al., 2014). Heavy episodic drinking (HED) among men involves consuming five or more alcoholic beverages in two hours (NIAAA, 2003). There are pharmacological and psychological explanations for the association between alcohol use and sexual aggression (for a review, see Abbey et al., 2014). Alcohol serves as a disinhibiting force (Giancola, Josephs, Parrott, & Duke, 2010); not only does it pharmacologically impair one’s attentional capacity (Steele & Josephs, 1990), it also compromises one’s ability to regulate behavior. Thus, an individual who engages in HED more frequently may at times be less inhibited, increasing their likelihood of perpetrating rape.

Research has found that individuals who perpetrate sexual aggression consume high levels of alcohol in general and in sexual situations (Abby et al., 2001; Abbey & McAuslan, 2004) and a large number of cross-sectional studies have found a direct, positive association between proximal and distal measures of alcohol use including HED, and sexual aggression perpetration, including composite outcomes comprising completed rape (Abbey et al., 2014). Daily diary studies have found that sexual aggression was more likely on days in which HED occurred than on days when alcohol was not consumed (Shorey, Stuart, McNulty, & Moore, 2014). Moreover, approximately two-thirds of women who reported being raped as adults stated that the perpetrator was utilizing alcohol at the time of the rape (CDC, 2018). Very few studies have examined alcohol consumption as a prospective predictor of sexual aggression perpetration; those that have produced conflicting results and did not focus specifically on completed rape. Problem drinking has been longitudinally associated with sexual aggression (Gidycz, Warkentin, & Orchowski, 2007) and heavy drinking also indirectly predicted subsequent sexual aggression (Thompson, Koss, Kingree, Foree, & Rice, 2011). In Testa & Cleveland’s (2017) longitudinal examination of college men, individuals with higher frequency HED were more likely to perpetrate sexual aggression over the first five semesters of college. However, this between-persons effect was completely explained by personality variables. More prospective research on the association between HED and completed rape is certainly warranted.

While the disinhibiting effects of alcohol are well-documented (Giancola et al., 2010), there is a dearth of research examining how IPV history and HED may influence future rape perpetration. Because men with histories of IPV are likely to also have difficulty regulating their behavior, when they also demonstrate a pattern of heavy drinking, their disinhibition may be amplified thereby increasing their likelihood of perpetrating rape. However, this has yet to be examined prospectively.

Present Study

The purpose of the present study was to extend previous research and examine physical IPV, psychological IPV, coercive CUR, and HED as prospective predictors of completed rape during a 3-month follow-up period in a community sample of non-problem drinking men. In addition, we aimed to investigate coercive CUR and HED as potential moderators of the associations between physical and psychological IPV and completed rape. We hypothesized that physical IPV, psychological IPV, coercive CUR, and HED would be significantly positively associated with completed rape during follow-up. Moreover, we expected that coercive CUR and HED would each moderate the associations between physical IPV and completed rape and psychological IPV and completed rape. Thus, we expected that men with a) greater coercive CUR and greater physical IPV histories, b) greater coercive CUR and greater psychological IPV histories, c) greater HED and greater physical IPV histories, and d) greater HED and greater psychological IPV histories would perpetrate more completed rape during follow-up. Additionally, we hypothesized that coercive CUR would interact with HED such that men with greater coercive CUR and greater HED would perpetrate more completed rape during follow-up. Furthermore, due to the risk nexus that exists between IPV, coercive CUR, and HED, we conducted exploratory analyses investigating a three-way interaction between physical IPV, coercive CUR, and HED predicting completed rape, as well as a three-way interaction between psychological IPV, coercive CUR, and HED predicting completed rape. Physical and psychological IPV were examined in separate three-way interactions because each form of IPV is distinct and may interact differentially with coercive CUR and HED to predict completed rape. This is the first known prospective investigation of these four risk factors for completed rape, given the need for comprehensive violence research that is inclusive of various types of aggressive behavior (Grych & Swan, 2012).

Method

Participants

Six hundred and thirty-six men (Mage = 24.7, SDage = 2.7) were recruited from a metropolitan community in the Pacific Northwest. Participants were recruited via online and print advertisements for a research study on male-female social interactions and called the laboratory for an eligibility screener. Eligibility criteria included men who were: a) aged 21–30, b) single, c) non-problem drinker, d) interested in sexual relationships with women, and e) reported vaginal or anal intercourse without a condom at least once in the past year. Participants who met criteria for problematic drinking (i.e., had symptoms of or were at risk for alcohol dependence) and/or those who reported medical conditions, medications that contraindicated alcohol consumption, or an adverse reaction to alcohol in the past were excluded due to the alcohol administration procedure included in the full study protocol. Eighty-eight percent of the sample, or 562 participants, provided data during the 3-month follow-up assessment period. Of this, 430 men reported engaging in sexual intercourse at least once during the follow-up period and were included in the present analyses. Approximately 67% of the sample was Caucasian, 16% Multiracial (or “other”), 9% African American/Black, 7% Asian American/Pacific Islander, 1% Native American, and 9% Hispanic/Latino of any race. A large majority (83.4%) had at least some college-level education, approximately 52.7% were employed, and 30.0% stated that they were current full- or part-time students.

Procedure

Participants arrived at the laboratory, provided informed consent, and completed a battery of background questionnaires online in a private room. Participants completed measures regarding their demographics, physical and psychological IPV histories, alcohol use, and coercive CUR history. Next, participants completed an alcohol administration procedure and sexual risk vignette as part of a larger study, though this experimental portion is not included in the present investigation. Participants were debriefed after the laboratory session and compensated $15/hour for their time. Following the laboratory session, participants completed two online follow-up surveys that occurred six weeks and three months post-experiment. Participants were emailed a link to each follow-up survey, which instructed them to report on their sexual activity in the previous six-week period. Participants were compensated $30 per follow-up survey, with a $15 bonus for completing both follow-up surveys. Moreover, participants who completed both follow-up surveys were entered into prize drawings. All study procedures were approved by the University’s Human Subjects Division.

Background Survey Measures

IPV history.

The Dating Relationship Violence Questionnaire (Swahn, Simon, Arias, & Bossarte, 2008) was utilized to assess how often participants perpetrated physical and psychological IPV in the past year. Men completed nine items regarding acts of physical IPV (e.g., “hit or slapped a partner”; α = .74) and eight items regarding acts of psychological IPV (e.g., “said things to hurt a partner’s feelings on purpose”; α = .70). Participants selected one of seven responses (0 = This has never happened; 1 = Once in the past year; 2 = Twice in the past year; 3 = 3–5 times in the past year; 4 = 6–10 times in the past year; 5 = 11–20 times in the past year; 6 = More than 20 times in the past year) and items were scored according to recommendations by Straus and colleagues (1996). Response options were recoded to the midpoint of the range (e.g., option 3 was recoded to 4) and option 6 was recoded to 25. Physical and psychological IPV frequency subscales were created by summing participants’ scores on the nine and eight items, respectively.

Coercive CUR.

The Condom Use Resistance Survey (Davis et al., 2014b) was utilized to assess how often participants successfully avoided using condoms since age 14 with a woman who wanted to use one. Thirteen items asked men how many times (0 = 0 times through 20 = 20 times and 25 = 20+ times) they utilized coercive tactics to obtain condomless sex with a woman. Tactics included emotional manipulation (3 items; e.g., “Telling her how angry you would be if she insisted on using a condom”), deception (4 items; e.g., “Pretending that you had been tested and did not have any STDs”), stealthing (1 item; e.g., “Agreeing to use a condom, but removing it before or during sex without telling her”), intentional condom breakage (2 items; e.g., “Agreeing to use a condom but intentionally breaking the condom when putting it on”), and force (3 items; e.g., “Preventing her from getting a condom by staying on top of her”). A coercive CUR history score was computed by summing responses to all thirteen items (α = .79).

Alcohol use.

HED frequency was assessed according to National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Recommended Alcohol Questions (NIAAA, 2003) with the item, “During the last 12 months, how often did you have 5+ drinks containing any kind of alcohol within a two-hour period?” Participants selected one of ten responses (0 = Not at all; 1 = 1 to 2 times in the past year; 2 = 3 to 11 times in the past year; 3 = Once a month; 4 = 2 to 3 times a month; 5 = Once a week; 6 = Twice a week; 7 = 3 to 4 times a week; 8 = 5 to 6 times a week; 9 = Every day).

Follow-up Survey Measures

Completed rape.

A modified Timeline Followback (Sobell & Sobell, 1992) was utilized to assess days in which participants reported having sexual intercourse. Participants were shown a calendar of the past six-week period and selected the dates in which they engaged in sexual intercourse (vaginal, oral, or anal) with a partner. A day was defined as beginning at 6:00 am and finishing at 5:59 am the following morning. The Timeline Followback has demonstrated reliability and validity for assessing sexual behavior (Carey, Carey, Maisto, Gordon, & Weinhardt, 2001; Weinhardt et al., 1998).

For each day participants reported having sex, they were asked follow-up questions about their sexual encounters modified from the Sexual Aggression Survey (Abbey, Parkhill, & Koss, 2005). Men indicated whether they utilized verbal coercion (3 items; “Overwhelmed her with continual arguments or pressure”; “Made promises or told her things you knew were untrue”; and “Showed her your displeasure by swearing, sulking, getting angry, or making her feel guilty”), incapacitation (1 item; “Engaged in sexual activity with her when she was passed out or too intoxicated to give consent or stop what was happening”), and force (1 item; “Used or threatened to use some degree of physical force”) to make their partner have sex when she did not want to. If any of these tactics were used, the event was considered completed rape. These events were summed over the 90-day follow-up period to create a total score representing the number of completed rape events perpetrated per participant over the course of three months.

Data Analytic Strategy

We utilized generalized linear models (GzLM) in SPSS version 19 to examine physical and psychological IPV, HED, and coercive CUR as risk factors for completed rape. The outcome variable, completed rape, refers to the number of rape events perpetrated per participant during the three-month follow-up period. This variable represents count data that was positively skewed and distributed non-normally. Rather than use transformations to reduce skew or dichotomize the outcome variable which reduced statistical power (Cohen, 1983), we followed recommendations outlined by Atkins & Gallop (2007) and utilized a negative binomial distribution and log link function to account for the nonnormality in the completed rape outcome variable. GzLMs with negative binomial distributions provide incidence rate ratios (IRRs), which are exponentiated regression coefficients and represent a standardized effect size.

Because we were interested in examining the effects of all four risk factors on completed rape during follow-up, in Model 1, we entered main effects of physical IPV, psychological IPV, HED, and coercive CUR. In Model 2, we included main effects as well as all five, two-way interactions between the four predictor variables. Prior to creating interaction terms, all predictor variables were standardized to reduce potential heteroscedasticity. Furthermore, we conducted a third exploratory model in which we included the above main effects and interactions as well as two, three-way interactions between physical IPV, coercive CUR, and HED as well as psychological IPV, coercive CUR, and HED predicting completed rape during follow-up.

Results

Of the 430 men who reported engaging in sexual intercourse at least once during this time period, 183 (42.6%) reported perpetrating coercive CUR since age 14. A majority of participants (83.0%) indicated engaging in HED at least once per month. In addition, 244 men (56.7%) reported past year psychological IPV perpetration and 62 men (14.4%) reported past year physical IPV perpetration. Furthermore, 35 men (8.2%) reported perpetrating 81 completed rapes throughout the three-month follow-up period. The number of completed rapes per participant ranged from one to nine. Descriptive statistics and correlations for primary study variables are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Correlations and descriptive characteristics of study variables (N = 430)

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Physical IPV frequency, past year | -- | ||||

| 2. Psychological IPV frequency, past year | .46** | -- | |||

| 3. Coercive CUR frequency, since age 14 | .04 | .26** | -- | ||

| 4. HED frequency, past year | −.01 | −.02 | .01 | -- | |

| 5. Completed rape | .10* | .12* | .18** | .12* | -- |

| M | 0.7 | 4.7 | 4.4 | 3.4 | 0.2 |

| (SD) | (3.4) | (9.1) | (10.9) | (1.9) | (0.9) |

Note. IPV = intimate partner violence; CUR = condom use resistance; HED = heavy episodic drinking.

p < .05.

p < .01.

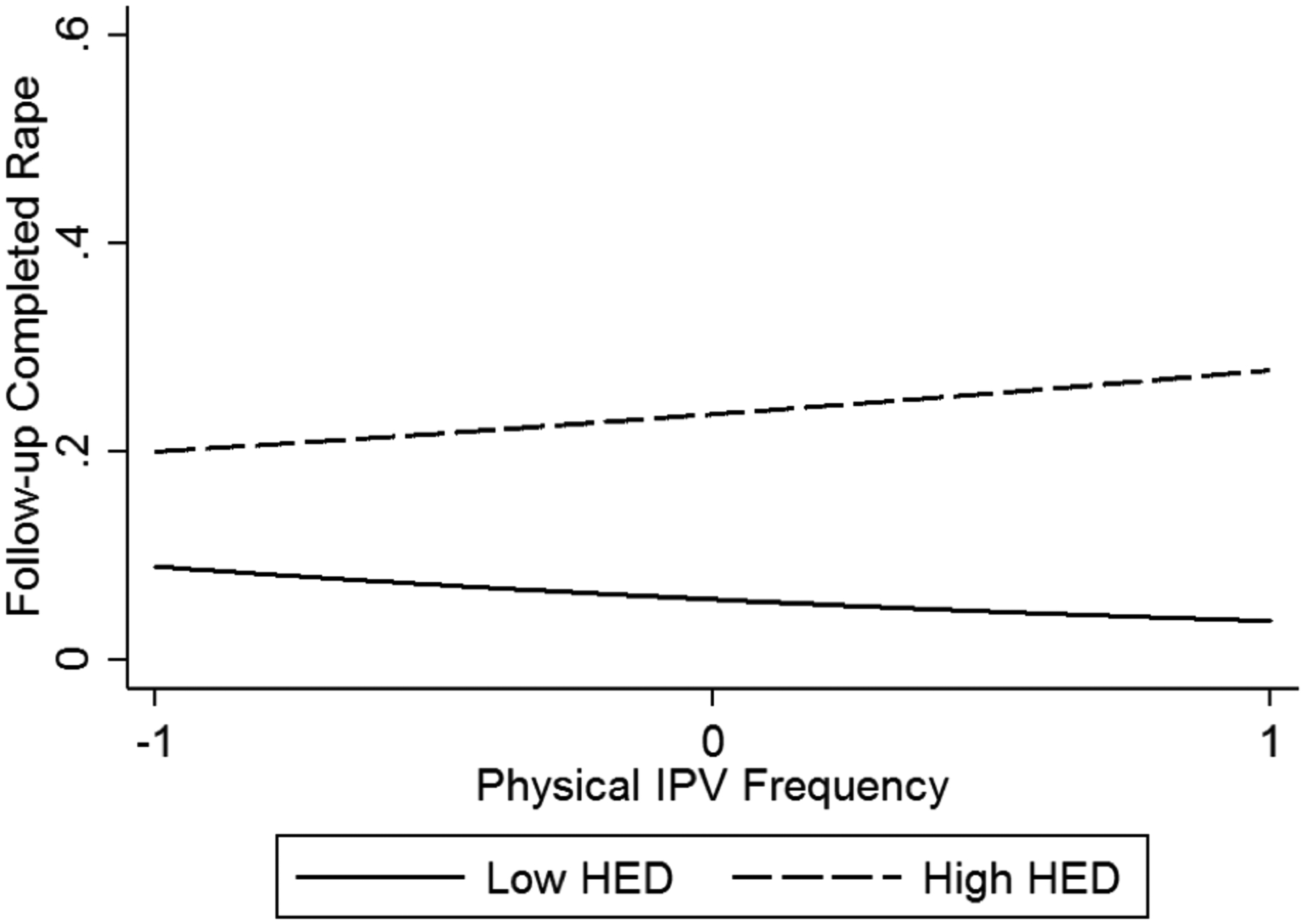

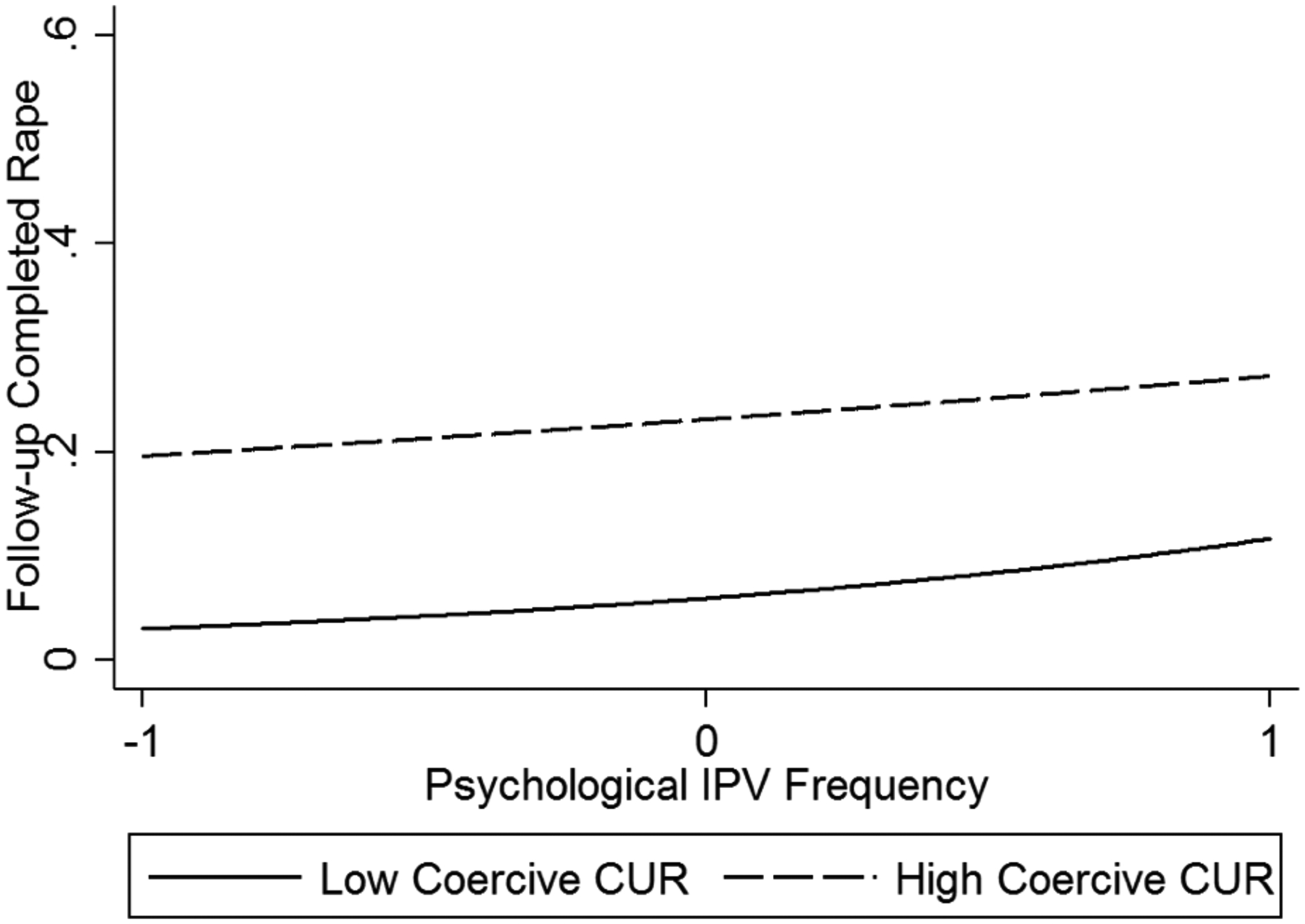

In Model 1 (see Table 2), psychological IPV, coercive CUR, and HED emerged as significant predictors of completed rape. Greater psychological IPV, coercive CUR and HED were associated with more completed rapes during follow-up. Physical IPV did not significantly predict completed rape. When the two-way interactions were added in Model 2 (see Table 2), there was a significant interaction between physical IPV and HED; individuals with high HED and greater physical IPV histories perpetrated more completed rapes during follow-up than men with low HED at the same level of physical IPV (see Figure 1). Furthermore, there was a significant interaction between psychological IPV and coercive CUR; as can be seen in Figure 2, individuals with high coercive CUR and greater psychological IPV histories perpetrated more completed rapes throughout the follow-up period than men with low coercive CUR at the same level of psychological IPV. However, we note that the interaction term is negative; at extremely high levels of psychological IPV not depicted in the figure (2-3 SDs above the mean), men with low coercive CUR surpass those with high coercive CUR with respect to follow-up completed rapes. There were no other significant two-way interactions in Model 2.

Table 2.

Results of the GzLM model examining the influence of physical IPV, psychological IPV, coercive CUR, and HED on completed rape during the 3-month follow-up assessment period.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | IRR (95% CI) | b | IRR (95% CI) | b | IRR (95% CI) | |

| Physical IPV | 0.10 | 1.10 (0.86, 1.41) | −0.13 | 0.88 (0.56, 1.38) | −0.21 | 0.81 (0.52, 1.27) |

| Psychological IPV | 0.28*** | 1.32 (1.09, 1.61) | 0.42*** | 1.52 (1.21, 1.90) | 0.41*** | 1.50 (1.19, 1.89) |

| Coercive CUR | 0.50*** | 1.64 (1.29, 2.08) | 0.68*** | 1.97 (1.37, 2.82) | 0.64*** | 1.89 (1.31, 2.75) |

| HED | 0.70*** | 2.02 (1.51, 2.71) | 0.70*** | 2.01 (1.48, 2.72) | 0.69*** | 2.00 (1.47, 2.73) |

| Physical IPV x Coercive CUR | -- | 0.22 | 1.24 (0.95, 1.62) | 0.02 | 1.02 (0.65, 1.59) | |

| Physical IPV x HED | -- | 0.30* | 1.35 (1.01, 1.79) | 0.46* | 1.58 (1.04, 2.40) | |

| Psychological IPV x Coercive CUR | -- | −0.25* | 0.78 (0.61, 0.98) | −0.18 | 0.84 (0.65, 1.08) | |

| Psychological IPV x HED | -- | −0.03 | 0.97 (0.71, 1.32) | −0.10 | 0.91 (0.65, 1.27) | |

| Coercive CUR x HED | -- | −0.16 | 0.85 (0.61, 1.18) | −0.21 | 0.81 (0.55, 1.21) | |

| Physical IPV x Coercive CUR x HED | -- | -- | -- | 0.53 | 1.70 (0.62, 4.67) | |

| Psychological IPV x Coercive CUR x HED | -- | -- | -- | 0.11 | 1.12 (0.85, 1.47) | |

Note. IRR = incidence rate ratio; CI = confidence interval; IPV = intimate partner violence; CUR = condom use resistance; HED = heavy episodic drinking.

p < .05.

p < .001.

Figure 1.

Physical IPV frequency and HED interact to predict completed rape during follow-up. Estimated values of HED are plotted at +/− 1 standard deviation from the mean. Physical IPV frequency is standardized such that it has a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1.

Figure 2.

Psychological IPV frequency and coercive CUR interact to predict completed rape during follow-up. Estimated values of coercive CUR are plotted at +/− 1 standard deviation from the mean. Psychological IPV frequency is standardized such that it has a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1.

Model 3 (see Table 2) included all variables in Model 2 as well as two exploratory three-way interactions predicting completed rape. Psychological IPV and coercive CUR significantly predicted completed rape, and the interaction between physical IPV and HED remained significant. However, the interaction between psychological IPV and coercive CUR was no longer significant; this is likely due to a reduction in variance when including the three-way interactions. Neither of the exploratory three-way interactions were significant.

Discussion

The results of this investigation add to a limited body of research examining physical and psychological IPV histories in combination with coercive CUR and HED to prospectively predict completed rape. Eighty-one completed rapes occurred during the 90-day follow-up period by 8% of men included in the sample. Though an alarming statistic, this is consistent with past research suggesting that a minority of men perpetrate the majority of completed rapes (Gidycz, Orchowski, & Berkowitz, 2011; Lisak & Miller, 2002). Results demonstrate that psychological IPV, coercive CUR, and HED were more pervasive in this sample than physical IPV. Notably, four times as many men perpetrated past year psychological IPV than past year physical IPV, which is also consistent with prior findings (WHO, 2012). Psychological IPV, coercive CUR, and HED also significantly predicted completed rape during the follow-up period. Moreover, physical IPV and HED interacted such that men with high HED and greater physical IPV histories perpetrated more completed rape during the three-month follow-up period than men with low HED at the same level of physical IPV. Furthermore, men with high coercive CUR and greater psychological IPV histories perpetrated more completed rape during follow-up than men with low coercive CUR at the same level of psychological IPV. This was the first prospective investigation that analyzed the risk nexus for completed rape by including a novel risk factor, coercive CUR, alongside IPV and alcohol use.

The present study aimed to attain a more comprehensive understanding of the topography of different forms of aggression by identifying the types of men most likely to perpetrate rape based on their aggression histories. These findings highlight how different forms of aggression are connected and interrelated, and they serve as a preliminary step to answer calls to action from violence researchers who espouse integration among IPV, sexual aggression, and sexual risk research (Hamby, 2014; Hamby & Grych, 2013). Thus, the outcome variable in this study, completed rape, should be examined with due consideration of other types of violence perpetrated in the past or currently being perpetrated. The results from this research point to one potential profile for men at greater risk for perpetrating completed rape—those with greater physical IPV histories who are heavier drinkers. This adds to a body of prospective evidence that heavy alcohol use may influence sexual aggression perpetration and specifically, completed rape. Though this may not seem entirely surprising given the correlated nature of physical IPV and sexual aggression, the prospective design of the present study highlights the importance of assessing both forms of violence in future research. Additionally, it is notable that HED only interacted with physical IPV history, and not psychological IPV history, to predict completed rape. It is possible that physical IPV represents a more severe aggressive behavior compared to psychological IPV, which typically encapsulates more minor aggressive acts. While the current study did not examine underlying mechanisms that may explain this interaction effect, it is possible that men who engage in high HED and physical IPV demonstrate greater self-regulatory problems and impulse control difficulties (Finkel, 2008), resulting in more frequent perpetration of completed rape. Future research should employ prospective designs to investigate the role of mechanisms such as self-regulation in the links among HED, physical IPV, and completed rape.

Novel to this study was the inclusion of coercive CUR, emphasizing an additional profile for men at higher risk for perpetrating completed rape—those with greater psychological IPV histories and greater coercive CUR histories. Notable in this interaction is the jointly manipulative nature of psychological IPV and utilizing coercive tactics, such as deception or emotional manipulation, to resist condoms during sexual intercourse. Though these calculating acts may appear less severe than overt physical IPV, which is more commonly associated with sexual aggression (Basile & Hall, 2011), our results suggest that they in no way mitigate risk for completed rape. On the contrary, these findings demonstrate that sexual coercion and sexual risk do not necessarily occur in isolation (Davis et al., 2018b). Condomless sex also implies greater risk for STIs and pregnancy (CDC, 2017), which should be taken into consideration when examining sexual aggression perpetration and completed rape specifically. However, it is important to note that the interaction between psychological IPV and coercive CUR was negative in Model 2; men with low coercive CUR surpassed men with high coercive CUR on follow-up completed rape at extremely high levels of psychological IPV, suggesting that the negative interaction term observed is influenced by a few individuals at the extreme end of the distribution. Additionally, this interaction disappeared in Model 3 when exploratory interactions were included. While it is possible that this is due to the variance accounted for by other factors included in the model, this finding should nevertheless be interpreted cautiously and future research should seek to replicate these results. Moreover, future research would benefit from utilizing latent profile analysis to delineate aggression profiles for individuals based on their aggression histories, including IPV perpetration, coercive CUR, and other forms of violence not included in the present analysis such as bullying or peer aggression.

Integrated violence research can inform intervention and prevention programming. For interventions to be effective, we must consider that individuals who perpetrate rape may have also perpetrated violence in other contexts, utilizing different forms of aggression. Most intervention programs, for example, focus on a single form of violence, even though it is likely that the effectiveness of an intervention program should take into account other types of aggression the individual has perpetrated (Grych & Swan, 2012; Hamby & Grych, 2013). Questions remain about what these interventions could look like and how targeted they need to be. The results of this study point to integrated programs targeting multiple forms of violence including physical, psychological, and sexual aggression as well as sexual health, condom use, and alcohol use. Interventions focusing on shared, underlying mechanisms of these high risk behaviors may be most fruitful. For example, an intervention addressing both HED and physical IPV may emphasize regulatory skills (e.g., emotion regulation, distress tolerance) in addition to traditional harm-reduction approaches for reducing alcohol use (i.e., normative feedback). All of the variables identified in the present investigation have the potential to be useful; however, our aggression research remains siloed and, consequently, our interventions remain so as well.

There are limitations to the present study. This sample included men who engage in heavy, but otherwise non-problematic drinking, men who are willing to drink alcohol in a laboratory setting (as part of the main study protocol), and only men who have sex with women; thus, generalizability is limited. Additional research exploring more diverse samples, including completed rape perpetrated by men who have sex with men, women who have sex with women, and women who have sex with men is important to advance understanding of this behavior. Moreover, completed rape was assessed via self-report which introduces the possibility that men may have responded in socially desirable ways (i.e., overreporting sexual activity and/or underreporting sexually aggressive acts). Additionally, the assessment required retrospective recall of up to six weeks which may have influenced participants’ memory for and reporting of events. Future research could employ a daily diary approach to mitigate this concern. Nevertheless, the present research attempted to address these limitations by utilizing behaviorally-oriented questions to examine completed rape after men already stated that they had had sexual intercourse, and by utilizing online surveys to encourage more honest responding. While it is vital to understand the topography of different types of violence, we were not able to assess developmental trajectories of aggressive behavior in this study.

In conclusion, the current study provides support for a limited body of research examining how IPV history, coercive CUR, and alcohol use prospectively predict completed rape. Of particular importance is the nexus that exists between various forms of violence and sexual risk. Future research should seek to understand the genesis of different forms of aggression and how they coalesce or differentiate over time. Are there common historical patterns of violence among individuals who perpetrate completed rape? A developmental lens is key to moving forward in this arena of research that has remained relatively stagnant. Also vital is a comprehensive understanding of underlying mechanisms contributing to sexual aggression perpetration; we envision combining mechanistic research with a systemic exploration of types of violence and how they interact. At the very least, future research should continue to pursue an integrative and inclusive topographic landscape of various forms of aggressive behavior.

Acknowledgments:

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism awarded to Natasha K. Gulati (F31AA028144), Kelly Cue Davis (R01AA017608), Cynthia Stappenbeck (K08AA021745), and Mary Larimer (T32AA007455). Authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Footnotes

Data availability statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Contributor Information

Natasha K. Gulati, Department of Psychology, University of Washington;

Cynthia A. Stappenbeck, Department of Psychology, Georgia State University;

William H. George, Department of Psychology, University of Washington;

Kelly Cue Davis, Edson College of Nursing and Health Innovation, Arizona State University..

References

- Abbey A (2002). Alcohol-related sexual assault: A common problem among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, s14, 118–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A & McAuslan P (2004). A longitudinal examination of male college students’ perpetration of sexual assault. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 747–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, McAuslan P, Zawacki T, Clinton AM, Buck PO (2001). Attitudinal, experiential, and situational predictors of sexual assault perpetration. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 16, 784–807. doi: 10.1177/088626001016008004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, Parkhill MR, & Koss MP (2005). The effects of frame of reference on responses to questions about sexual assault victimization and perpetration. Psychology of Women, 29, 364–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, Wegner R, Woerner J, Pegram SE, & Pierce J (2014). Review of survey and experimental research that examines the relationship between alcohol consumption and men’s sexual aggression perpetration. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, 15, 265–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins DC, & Gallop RJ (2007). Rethinking how family researchers model infrequent outcomes: A tutorial on count regression and zero-inflated models. Journal of Family Psychology, 21, 726–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnham L, Barnes GC, & Sherman LW (2017). Targeting escalation of intimate partner violence: Evidence from 52,000 offenders. Cambridge Journal of Evidence-Based Policing, 1, 116–142. [Google Scholar]

- Basile KC, & Hall JE (2011). Intimate partner violence perpetration by court-ordered men: Distinctions and intersections among physical violence, sexual violence, psychological abuse, and stalking. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26, 230–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L, Lucas KJ, & Tschann JM (2004). “The ball was always in his court”: An exploratory analysis of relationship scripts, sexual scripts, and condom use among African American women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 28, 70–82. [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, Carey KB, Maisto SA, Gordon CM, & Weinhardt LS (2001). Assessing sexual risk behavior with the Timeline Followback (TLFB) approach: Continued development and psychometric evaluation with psychiatric outpatients. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 12, 365–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2017). Condom effectiveness. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/condomeffectiveness/index.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2018). Sexual violence. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/sexualviolence/index.html.

- Cohen J (1983). The cost of dichotomization. Applied Psychological Measurement, 7, 249–253. [Google Scholar]

- Davis KC (2018). Men’s Coercive Condom Use Resistance: The Roles of Alcohol Intoxication, Sexual Aggression History, and Emotional Factors Invited talk at Recent Advances in Understanding and Preventing Alcohol-Related Sexual Assault, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Bethesda, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Davis KC, Danube CL, Neilson EC, Stappenbeck CA, Norris J, George WH, & Kajumulo KF (2016a). Distal and proximal influences on men’s intentions to resist condoms: alcohol, sexual aggression history, impulsivity, and social-cognitive factors. AIDS and Behavior, 20, 147–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KC, Jacques-Tiura AJ, Stappenbeck CA, Danube CL, Morrison DM, Norris J, & George WH (2016b). Men’s condom use resistance: Alcohol effects on theory of planned behavior constructs. Health Psychology, 35, 178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KC, Kiekel PA, Schraufnagel TJ, Norris J, George WH, & Kajumulo K (2012). Men’s alcohol intoxication and condom use during sexual assault perpetration. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27, 2790–2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KC, Gulati NK, Neilson EC, & Stappenbeck CA (2018a). Men’s coercive condom use resistance: The roles of sexual aggression history, alcohol intoxication, and partner condom negotiation. Violence Against Women, 24, 1349–1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KC, Neilson EC, Wegner R, & Danube CL (2018b). The intersection of men’s sexual violence and sexual risk behavior: A literature review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 40, 83–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KC, Schraufnagel TJ, Kajumulo KF, Gilmore AK, Norris J, & George WH (2014a). A qualitative examination of men’s condom use attitudes and resistance: “It’s just part of the game”. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43(3), 631–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KC, Stappenbeck CA, Norris J, George WH, Jacques-Tiura AJ, Schraufnagel TJ, & Kajumulo KF (2014b). Young men’s condom use resistance tactics: A latent profile analysis. The Journal of Sex Research, 51, 454–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Justice (2015). Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Crime Victimization Survey, 2010–2014.

- Dewall CN, Baumeister RF, Stillman TF, & Gailliot MT (2007). Violence restrained: Effects of self-regulation and its depletion on aggression. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43, 62–76. [Google Scholar]

- Finkel EJ (2007). Impelling and inhibiting forces in the perpetration of intimate partner violence. Review of General Psychology, 11, 193–207. [Google Scholar]

- Finkel EJ (2008). Intimate partner violence perpetration: Insights from the science of self-regulation In Forgas JP & Fitness J (Eds.) Social relationships: Cognitive, affective, and motivational processes (pp. 271–288). New York: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR, Josephs RA, Parrott DJ, & Duke AA (2010). Alcohol myopia revisited: Clarifying aggression and other acts of disinhibition through a distorted lens. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5, 265–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidycz CA, Orchowski LM, & Berkowitz AD (2011). Preventing sexual aggression among college men: An evaluation of a social norms and bystander intervention program. Violence Against Women, 17, 720–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidycz CA, Warkentin JB, & Orchowski LM (2007). Predictors of perpetration of verbal, physical, and sexual violence: A prospective analysis of college men. Psychology of Men and Masculinity, 8, 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Grych J & Swan S (2012). Toward a more comprehensive understanding of interpersonal violence: Introduction to the special issue on interconnections among different types of violence. Psychology of Violence, 2, 105–110. [Google Scholar]

- Hamby S (2014). Intimate partner and sexual violence research: Scientific progress, scientific challenges, and gender. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, 15, 149–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamby S & Grych J (2013). The web of violence: Exploring connections among different forms of interpersonal violence and abuse. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins S, & Aubé J (2002). Gender differences and gender-related constructs in dating aggression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 1106–1118. [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Nduna M, Shai NJ, & Dunkle K (2012). Prospective study of rape perpetration by young South African men: Incidence and risk factors. PLOS one. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy SB, Nolen S, Applewhite J, & Waiter E (2007). Urban African-American males’ perceptions of condom use, gender and power, and HIV-STD prevention program. Journal of the National Medical Association, 99, 1395–1401. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Heise L, & Russo NF (1994). The global health burden of rape. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 18, 509–537. [Google Scholar]

- Lisak D, & Miller PM (2002). Repeat rape and multiple offending among undetected rapists. Violence and Victims, 17, 73–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh C, Gidycz CA, Lobo TR, & Luthra R (2005). A prospective analysis of sexual assault perpetration: Risk factors related to perpetrator characteristics. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20, 1325–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CM, & O’Leary KD (1989). Psychological aggression predicts physical aggression in early marriage. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 57, 579–582. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.57.5.579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). (2003). Task force on recommended questions of the National Council on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Available at: http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/Resources/ResearchResources/TaskForce.htm.

- National Institute of Justice (2006). Extent, nature, and consequences of rape victimization: findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. Retrieved from https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/21950

- Peterson ZD, Janssen E, & Heiman JR (2010). The association between sexual aggression and HIV risk behavior in heterosexual men. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25, 538–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj A, Santana C, Marche A, Amaro H, Cranston K, & Silverman JG (2006). Perpetration of intimate partner violence associated with sexual risk behaviors among young adult men. American Journal of Public Health, 96, 1873–1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network (RAINN) (2017). Victims of Sexual Violence: Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.rainn.org/statistics/victims-sexual-violence

- Rothman EF, Reyes LM, Johnson RM, & LaValley M (2012). Does alcohol make them do it? Dating violence perpetration and drinking among youth. Epidemiologic Reviews, 34, 103–119. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxr027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey R, Stuart G, McNulty J, & Moore T (2014). Acute alcohol use temporally increases the odds of male perpetrated dating violence: A 90-day diary analysis. Addictive Behaviors, 39, 365–368. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.10.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC & Sobell MB (1992). Timeline Followback: A technique for assessing self-reported ethanol consumption In Allen JP & Litten RZ (Eds.), Measuring Alcohol Consumption: Psychosocial and Biological Methods (pp. 41–72). Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4612-0357-5_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stappenbeck CA, Gulati NK, & Fromme K (2016). Daily Associations Between Alcohol Consumption and Dating Violence Perpetration Among Men and Women: Effects of Self-Regulation. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 77, 150–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM & Josephs RA (1990). Alcohol myopia: Its prized and dangerous effects. American Psychologist, 45, 921–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swahn MH, Simon TR, Arias I, & Bossarte RM (2008). Measuring sex difference in violence victimization and perpetration within date and same-sex peer relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23, 1120–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, & Cleveland MJ (2017). Does alcohol contribute to college men’s sexual assault perpetration? Between- and within- person effects over five semesters. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 78. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2017.78.TK [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MP, Koss MP, Kingree JB, Goree J, & Rice J (2011). A prospective mediation model of sexual aggression among college men. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26, 2716–2734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MP, Swartout KM, & Koss MP (2013). Trajectories and predictors of sexually aggressive behaviors in emerging adulthood. Psychology of Violence, 3, 247–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden P, & Thoennes N (2000). Full report of the prevalence, incidence, and consequences of violence against women (National Institute of Justice, Research Report, NCJ No. 183781) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Townsend SM, Filipas HH, & Starzynski LL (2007). Structural models of the relations of assault severity, social support, avoidance coping, self-blame, and PTSD among sexual assault survivors. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31, 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Voller E & Long PL (2010). Sexual assault and rape perpetration by college men: The role of the big five personality traits. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25, 457–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker LEA (2006). Battered woman syndrome: empirical findings. Annals New York Academy of Sciences, 1087, 142–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinhardt LS, Carey MP, Maisto SA, Carey KB, Cohen MM, & Wickramasinghe SM (1998). Reliability of the Timeline Followback Sexual Behavior Interview. Annals of Behavior Medicine, 20, 25–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2012). Understanding and addressing violence against women. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/77432/WHO_RHR_12.36_eng.pdf;jsessionid=8130409EA9F8EDF7DC5C4A79F0EAA212?sequence=1