Abstract

Background:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) treat an expanding range of cancers. Consistent basic data suggest that these same checkpoints are critical negative regulators of atherosclerosis. Therefore, our objectives were to test whether ICIs were associated with accelerated atherosclerosis and a higher risk of atherosclerosis-related cardiovascular events.

Methods:

The study was situated in a single academic medical center. The primary analysis evaluated whether exposure to an ICI was associated with atherosclerotic cardiovascular events in 2842 patients and 2842 controls, matched by age, a history of cardiovascular events and cancer type. In a second design, a case-crossover analysis was performed with an “at-risk period” defined as the two-year period after and the “control period” as the two-year prior to treatment. The primary outcome was a composite of atherosclerotic cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization and ischemic stroke). Secondary outcomes included the individual components of the primary outcome. Additionally, in an imaging sub-study (n=40), the rate of atherosclerotic plaque progression was compared from before and after starting an ICI. All study measures and outcomes were blindly adjudicated.

Results:

In the matched cohort study, there was a 3-fold higher risk for cardiovascular events after starting an ICI (HR, 3.3 [95% CI, 2.0–5.5]; P<0.001). There was a similar increase in each of the individual components of the primary outcome. In the case-crossover, there was also an increase in cardiovascular events from 1.37 to 6.55 per 100 person-years at two years (adjusted HR, 4.8 [95% CI, 3.5–6.5]; P<0.001). In the imaging study, the rate of progression of total aortic plaque volume was >3-fold higher with ICIs (from 2.1%/year pre-to 6.7%/year post). This association between ICI use and increased atherosclerotic plaque progression was attenuated with concomitant use of statins or corticosteroids.

Conclusions:

Cardiovascular events were higher after initiation of ICIs, potentially mediated by accelerated progression of atherosclerosis. Optimization of cardiovascular risk factors and increased awareness of cardiovascular risk, prior to, during and after treatment, should be considered among patients on an ICI.

Keywords: Immune checkpoint inhibitors, immune therapy, atherosclerotic cardiovascular events, atherosclerotic plaque progression

Introduction

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) represent a paradigm shift in cancer care, leveraging the immune system to identify and target cancer cells.1 The use of ICIs is rapidly expanding. For example, in 2014, ICIs were approved for three cancer indications.2 By 2020, this number had increased to more than 50, and the percentage of patients with cancer eligible for an ICI has increased from 1.5% in 2011 to greater than 43.6%.3 The benefit of ICIs has expanded to the adjuvant setting in some malignancies,4, 5 and will continue to expand to patients with a much longer anticipated survival.4

Consistent animal and cellular studies have demonstrated that these immune checkpoints, currently targeted in approved indications: programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), are critical negative regulators of atherosclerosis.6–8 However, there are conflicting clinical and imaging data testing whether ICIs, by inhibiting these key pathways in atherosclerosis, lead to an increase in atherosclerotic plaque and atherosclerosis-related cardiovascular events.9–12 Given the potentially significant impact on public health, we performed both a matched cohort and a case-crossover study to determine whether the use of ICIs leads to an increase in cardiovascular events. To provide further insights, we also tested whether ICIs were associated with accelerated atherosclerotic plaque in a subsample.

Methods

The data, analytic methods, and study materials will be made available from the corresponding author on reasonable request after institutional approval and following institutional process.

Study design, setting and population

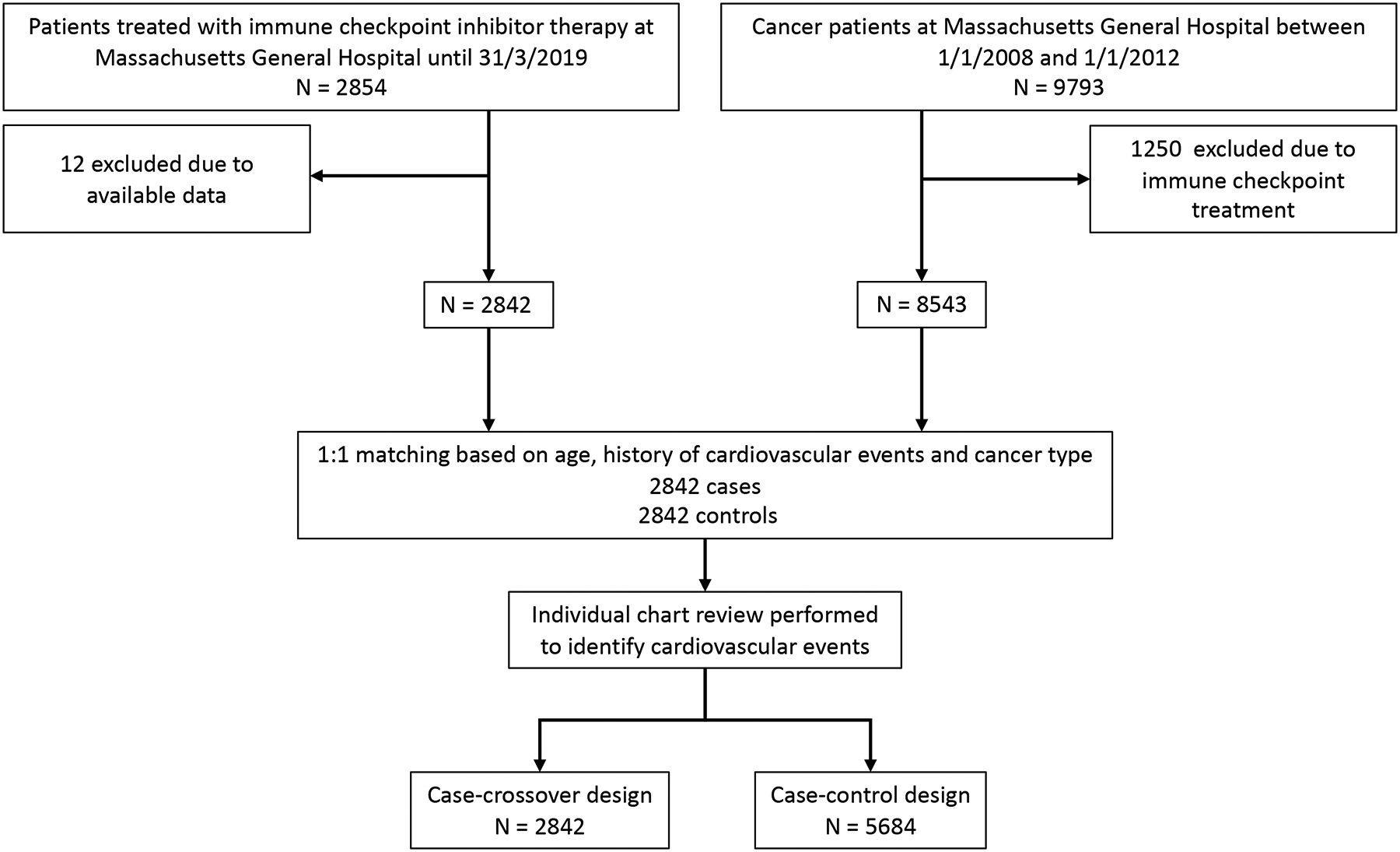

We chose two study designs to examine the association between ICIs and cardiovascular events, a matched cohort study and a case-crossover study. All individuals treated with an ICI through the end of March 2019 at a single academic institution (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA) were included. The use of an ICI was derived from a pharmacy database. The study entry date for the cases was defined as the first date an ICI was administered. For the matched cohort study, controls were selected from all patients treated for cancer at our center between January 1st 2008 and December 31st 2012. For the control group, the use of an ICI at any time point was an exclusion criteria. There were 9793 individual patients with cancer treated at our institution during that period. Of these, 1250 were excluded as they were treated with an ICI subsequently. This resulted in a cohort of 8543 patients. From these, we randomly selected controls in a 1:1 ratio to match cases for age, a history of cardiovascular events, and cancer type (Figure 1). The study entry for the controls was their first visit after Jan 1st, 2008. For the case-crossover design, we defined the observation period as the interval from two-year before to the start of the ICI. We defined the at-risk period as the two-year interval after the start of the ICI (Figure I in the Supplement). Covariates were derived from the Research Patient Data Registry. The study was approved by the Partners Human Research Committee and no informed consent was required. The authors vouch for the completeness and accuracy of the data and all analyses.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram.

Procedures

Covariates of interest obtained included patient demographics, medications, and standard cardiovascular risk factors (e.g., diabetes mellitus, hypertension, smoking). Data relevant to cancer included the cancer type, prior potentially cardiotoxic cancer therapies (radiation therapy, 5-fluorouracil, anthracyclines and tyrosine kinase inhibitors), and the specific ICI treatments, including the use of combined immune checkpoint therapy. Data specific to the ICI cohort also included the number of ICI cycles, the occurrence of any immune-related adverse event, and the use of corticosteroids.

Clinical outcomes

The primary outcome was the occurrence of a cardiovascular event, defined as a composite of myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization and ischemic stroke. The individual components of these were prespecified as key separate secondary outcomes. Events were initially identified from individual chart review of all records using a broad key word search and then all potential clinical events were independently adjudicated by a study team blinded to all other data and using standard definitions (Document I in the Supplement; Key words and definitions used for each of the adjudicated clinical events).13–15

Imaging study

We performed an imaging sub-study in which we measured the thoracic atherosclerotic plaque burden over time among patients with melanoma that were treated with an ICI. Melanoma was chosen as the population for the sub-study as it was one of the most common cancer seen in our study, ICIs are frequently used,16 and these therapies have had a marked impact on cancer outcomes.4, 16 Studies were performed as part of their routine clinical care for cancer staging. Thoracic aortic plaque volume was measured from these studies in a standardized fashion in a core laboratory blinded to all other study variables, including treatment status and sequence of imaging studies. The plaque volume was assessed on a limited field of view which excluded the surrounding non-vascular structures. The full analysis protocol, accuracy and reproducibility of these methods have been reported by our group previously (Figure II and III and Document II in the Supplement).13, 14, 17 This volumetric plaque assessment technique has demonstrated excellent intra- and inter-observer, as well as interscan reproducibility.18–20 In brief, total and non-calcified thoracic aortic plaque volume were measured on all 3 contrast computed tomography scans using dedicated software (QAngioCT, version 3.1.4.2, Medis Medical Imaging Systems, Leiden, the Netherlands).21 Relative plaque volume measures were assessed as percent of total segment volume. Plaque change was calculated as the difference in plaque volume measured on two consecutive scans (i.e., scan 2 – scan 1 and scan 1 – scan 0). Annualized plaque progression rate was computed as plaque change per year given in absolute and relative rates (mm3 and %).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to assess the distribution of variables; continuous variables were summarized as mean with (standard deviation) or medians with interquartile ranges (IQR), and categorical variables were summarized as counts and percentages. In the matched cohort study controls were matched 1:1 based on age, a history of cardiovascular events, and cancer type. In the matched cohort and case-crossover designs, Cox proportional hazard regression analysis was performed to calculate hazard ratios (HR) with 95% CIs, counting only the first cardiovascular event. Two approaches were applied. In the first, a parsimonious multivariable Cox proportional hazard model was performed, including known cardiovascular risk factors (model 1). In a second approach, a forward stepwise selection was used; clinically relevant unique predictor variables with a value of P < .10 in univariable analysis were entered into the final multivariable model (model 2). The incremental value between steps were measured by the likelihood-ratio test. The proportional hazard assumption was tested with the use of log-log plots and examination of Schoenfeld residuals. We performed sub-group analyses of hazard ratios by sex, age (<65 years vs. ≥65 years), body mass index (<30 kg/m2 vs. ≥30 kg/m2), a history of cardiovascular events, hypertension, diabetes, statin use, melanoma and lung cancer. We evaluated the presence of interactions in these sub-groups and hazard ratios stratified by these sub-groups were compared using the chi-squared test. In the case-crossover analysis,22, 23 Cox proportional hazard regression analyses were performed with calculation of 100-person years and a hazard ratio, adjusted for age. We compared atherosclerotic cardiovascular events in the two-year period before and the two-year period after the start of the ICI. We used Poisson regression during the two-year period pre- and post-ICI and calculated incidence rate ratio (IRR) with the outcome variable as a count variable including all events (first event and the ones occurred subsequently after the first event during the follow up period). In addition, we also tested a narrower risk period (one-year pre-and one-year post) and performed sensitivity analyses excluding patients who died within 60 days of the cardiovascular event. In the imaging sub-study, the primary outcome of interest was the change in total plaque volume over time in patients from pre- to post-ICI. The secondary imaging outcome was the change in non-calcified plaque volume. The annualized rate of change in plaque volume was compared from pre- to post-ICI using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. We performed analyses of plaque progression in pre-specified sub-groups defined by statin use, and the use of corticosteroids during ICI therapy. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and P values of less than .05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. Analyses were performed with SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute) and STATA software, version 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

Results

Patient demographics, comorbidities, and cancer data

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Baseline laboratory values are summarized in Table I in the Supplement. Overall cases and controls were not different with respect age, type of cancer, and a history of any cardiovascular event. Non-small cell lung cancer (28.8%) and melanoma (27.9%) were the most common type of cancer. Controls had higher rates of hypertension (53.5 vs. 49.2%, P=0.001) and diabetes mellitus (18.2 vs. 15.7%, P=0.014). Controls were more likely female (46.9 vs. 42.6%, P=0.001). The use of statins was not different between cases and controls (26.0 vs. 27.7%, P=0.17). Among the cases, PD-1 inhibitor therapy was the most commonly prescribed (75.3%) and cases had a median of five cycles of the ICI administered. Overall, 43.2% of the cases had an immune-related adverse event and 26.9% were treated with corticosteroids, 62.2% of those with immune-related adverse events.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor and control Patients

| Cases | Controls | P Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | |||||||

| Number of Patients | 2842 | 2842 | |||||

| Sex – no. (%) | |||||||

| Male | 1631 | (57.4) | 1509 | (53.1) | 0.001 | ||

| Female | 1211 | (42.6) | 1333 | (46.9) | 0.001 | ||

| Age – yr mean. (SD) | 64 | (13) | 64 | (13) | 0.14 | ||

| Age – yr, median. (IQR) | 66 | (57–74) | 65 | (55–74) | 0.11 | ||

| Race or ethnic group – no. (%) | <0.001 | ||||||

| White | 2479/2704 | (91.7) | 2851/2748 | (93.9) | |||

| Asian | 96/2704 | (3.6) | 43/2748 | (1.6) | |||

| Black or African American | 57/2704 | (2.1) | 64/2748 | (2.3) | |||

| Hispanic | 29/2704 | (1.1) | 40/2748 | (1.5) | |||

| Other | 43/2704 | (1.6) | 20/2748 | (0.7) | |||

| Clinical variables – mean. (SD) | |||||||

| Body mass index - (kg/m2) | 27.0 | (6.4) | 27.6 | (5.7) | <0.001 | ||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 127.6 | (18.6) | 127.6 | (16.9) | 0.93 | ||

| Cardiovascular risk factors – no (%) | |||||||

| Hypertension | 1356/2756 | (49.2) | 1518/2837 | (53.5) | 0.001 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 433/2756 | (15.7) | 517/2837 | (18.2) | 0.014 | ||

| Smoking current or prior | 429/2756 | (15.6) | 405/2837 | (14.3) | 0.19 | ||

| Hyperlipidemia | 840/2756 | (30.5) | 1048/2837 | (36.9) | <0.001 | ||

| Cardiovascular diagnoses – no (%) | |||||||

| History of any cardiovascular event | 322/2842 | (11.3) | 357/2842 | (12.6) | 0.16 | ||

| History of myocardial infarction | 136/2842 | (4.8) | 167/2842 | (5.9) | 0.077 | ||

| History of coronary revascularization | 195/2842 | (6.9) | 230/2842 | (8.1) | 0.078 | ||

| History of ischemic stroke | 82/2842 | (2.9) | 101/2842 | (3.6) | 0.18 | ||

| Cardiovascular medications – no. (%) | |||||||

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin II receptor blocker | 612/2704 | (22.6) | 647/2423 | (26.7) | <0.001 | ||

| Beta-blockers | 628/2704 | (23.2) | 798/2423 | (32.9) | <0.001 | ||

| Calcium channel blockers | 396/2704 | (14.6) | 360/2423 | (14.9) | 0.86 | ||

| Statins | 704/2704 | (26.0) | 672/2423 | (27.7) | 0.17 | ||

| Non-statin dyslipidemia therapies | 65/2704 | (2.4) | 122/2423 | (5.0) | <0.001 | ||

| Aspirin | 578/2704 | (21.4) | 603/2423 | (24.9) | 0.003 | ||

| Other anti-platelet therapies | 66/2704 | (2.4) | 98/2423 | (4.0) | 0.001 | ||

| Other medical comorbidities – no (%) | |||||||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 285/2756 | (10.3) | 169/2837 | (6.0) | <0.001 | ||

| Chronic kidney disease | 327/2756 | (11.9) | 326/2837 | (11.5) | 0.69 | ||

| Cancer types – no. (%) | |||||||

| Non-small cell lung | 819/2842 | (28.8) | 819/2842 | (28.8) | |||

| Melanoma | 794/2842 | (27.9) | 794/2842 | (27.9) | |||

| Head and neck | 344/2842 | (12.1) | 344/2842 | (12.1) | |||

| Renal and genitourinary | 182/2842 | (6.4) | 182/2842 | (6.4) | |||

| Breast | 119/2842 | (4.2) | 119/2842 | (4.2) | |||

| Gastrointestinal | 116/2842 | (4.1) | 1162842 | (4.1) | |||

| Gynecologic | 110/2842 | (3.9) | 110/2842 | (3.9) | |||

| Lymphoma | 82/2842 | (2.9) | 82/2842 | (2.9) | |||

| Hepatobiliary | 101/2842 | (3.6) | 101/2842 | (3.6) | |||

| Pancreatic | 37/2842 | (1.3) | 37/2842 | (1.3) | |||

| Other | 138/2842 | (4.9) | 138/2842 | (4.9) | |||

| Prior potentially cardiotoxic cancer therapies – no. (%) | |||||||

| Radiation therapy | 572/2756 | (20.8) | 287/2837 | (10.1) | <0.001 | ||

| 5-fluorouracil | 284/2723 | (10.4) | 151/2710 | (5.6) | <0.001 | ||

| Anthracyclines | 151/2723 | (5.5) | 153/2710 | (5.6) | 0.92 | ||

| Tyrosine kinase inhibitors | 61/2723 | (2.2) | 59/2710 | (2.2) | 0.95 | ||

| Immune checkpoint inhibitor type – no. (%) | |||||||

| Monotherapy | |||||||

| Programmed death-ligand-1 | 283/2842 | (10.0) | |||||

| Cytotoxic-T-Lymphocyte associated protein 4 | 221/2842 | (7.8) | |||||

| Programmed death-protein 1 | 2141/2842 | (75.3) | |||||

| Cytotoxic-T-Lymphocyte associated protein 4 or programmed death protein 1 | 2/2842 | (0.1) | |||||

| Combination therapy | |||||||

| Cytotoxic-T-Lymphocyte associated protein 4/Programmed death protein 1 | 195/2842 | (6.9) | |||||

| Number of cycles of ICI – no, (IQR) | 5 | (2–11) | |||||

| Immune mediated adverse events after immune checkpoint inhibitor start | |||||||

| Gastrointestinal | 500/2748 | (18.2) | |||||

| Skin | 429/2748 | (15.6) | |||||

| Pulmonary | 189/2748 | (6.9) | |||||

| Hepatic | 179/2748 | (6.5) | |||||

| Endocrine | 175/2748 | (6.4) | |||||

| Renal | 120/2748 | (4.4) | |||||

| Neuromuscular | 98/2748 | (3.6) | |||||

| Pancreas | 61/2748 | (2.2) | |||||

| Any of the above adverse events | 1186/2748 | (43.2) | |||||

| Immune mediated adverse events treated with steroids – no. (%) | |||||||

| Among the entire cohort | 738/2748 | (26.9) | |||||

| Among those with immune mediated adverse events | 738/1186 | (62.2) | |||||

Primary and secondary outcomes

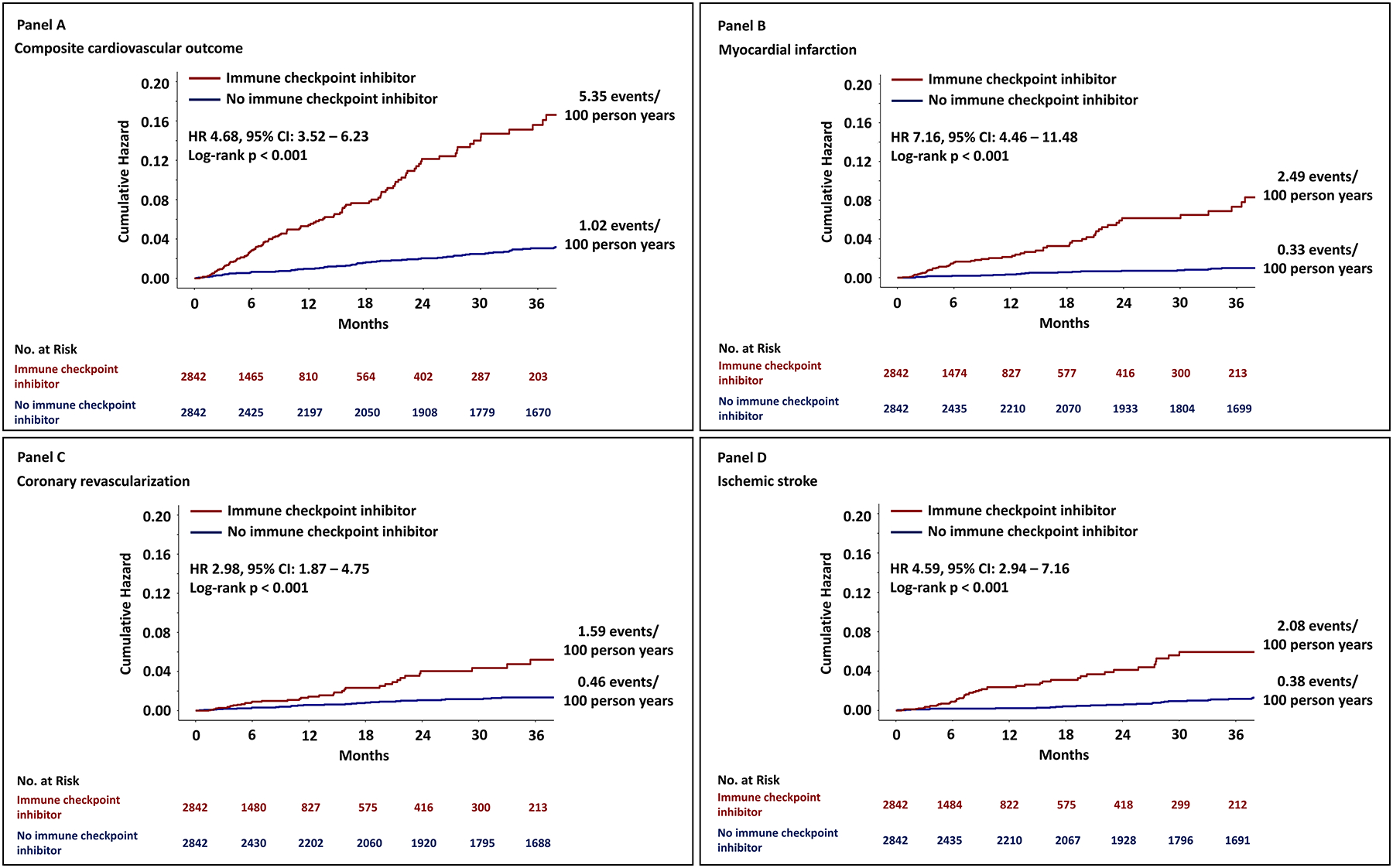

Demographic, clinical and cancer related variables were included in a univariable Cox proportional hazard model (Table II in the Supplement). The use of an ICI was associated with a >4-fold increase in the risk for a composite cardiovascular event (univariable HR, 4.7 [95% CI, 3.5–6.2]; P<0.001). For the individual outcomes, similar results were found (Figure 2) where the use of an ICI was associated with a higher risk for myocardial infarction (univariable HR, 7.2 [95% CI, 4.5–11.5;] P<0.001), a 3-fold increase in the risk for coronary revascularization (univariable HR, 3.0 [95% CI, 1.9–4.8]; P<0.001), and a 4-fold increase in the risk for ischemic stroke (univariable HR, 4.6 [95% CI, 2.9–7.2]; P<0.001). Kaplan Meier curves of the cumulative hazard in cases and controls of the composite and individual component outcomes and the event rates at 3 years are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Kaplan Meier curves of the cumulative hazard for atherosclerotic cardiovascular events.

Panel A shows the cumulative hazard for the composite cardiovascular outcome. The individual components of the primary outcome are also shown in Panel B, C and D. Cases (those treated with an ICI) are marked with red, and controls (not treated with an ICI) are marked with blue.

In a parsimonious multivariable model, which included known cardiovascular risk factors (male sex, age, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, smoking, prior history of a CV event, statin use, aspirin use, hemoglobin and low-density lipoprotein), the use of an ICI was associated with a 3-fold increase in the risk for a composite cardiovascular event (multivariable HR, 3.3 [95% CI 2.0–5.5]; P<0.001, Table 2, Model 1). In a second approach, the variables, identified as P<0.1 in the univariable Cox model, were entered into a multivariable model. In this model, the use of an ICI was associated with a 4-fold increase in the risk for a composite cardiovascular event (multivariable HR, 4.5 [95% CI, 3.3–6.1]; P<0.001, Table 2, Model 2).

Table 2.

Multivariable Cox proportional hazard model results of the composite cardiovascular outcome (myocardial infarction, revascularization, ischemic stroke)

| Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | Wald test P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multivariable model 1. | ||||

| Immune checkpoint inhibitors | 3.31 | 1.99 | 5.51 | <0.001 |

| Male sex | 1.71 | 1.14 | 2.54 | 0.009 |

| Age | 1.04 | 1.02 | 1.06 | <0.001 |

| Body mass index | 1.03 | 1.00 | 1.06 | 0.076 |

| Hypertension | 0.89 | 0.53 | 1.51 | 0.67 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.41 | 0.96 | 2.07 | 0.082 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 0.93 | 0.60 | 1.44 | 0.75 |

| Smoking current or prior | 1.27 | 0.83 | 1.95 | 0.27 |

| History of any cardiovascular event | 2.14 | 1.39 | 3.29 | 0.001 |

| Statins | 0.72 | 0.48 | 1.09 | 0.12 |

| Aspirin | 1.14 | 0.76 | 1.69 | 0.53 |

| Hemoglobin | 0.88 | 0.79 | 0.98 | 0.023 |

| Low-density lipoprotein | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.68 |

| Multivariable model 2. | ||||

| Immune checkpoint inhibitors | 4.50 | 3.30 | 6.13 | <0.001 |

| Age | 1.03 | 1.02 | 1.04 | <0.001 |

| History of any cardiovascular event | 2.19 | 1.63 | 2.94 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.42 | 1.07 | 1.87 | 0.01 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 0.01 |

| Non-small cell lung cancer | 1.54 | 1.19 | 2.01 | <0.001 |

| Prior radiation therapy | 1.54 | 1.13 | 2.09 | 0.01 |

| Male sex | 1.29 | 1.00 | 1.66 | 0.05 |

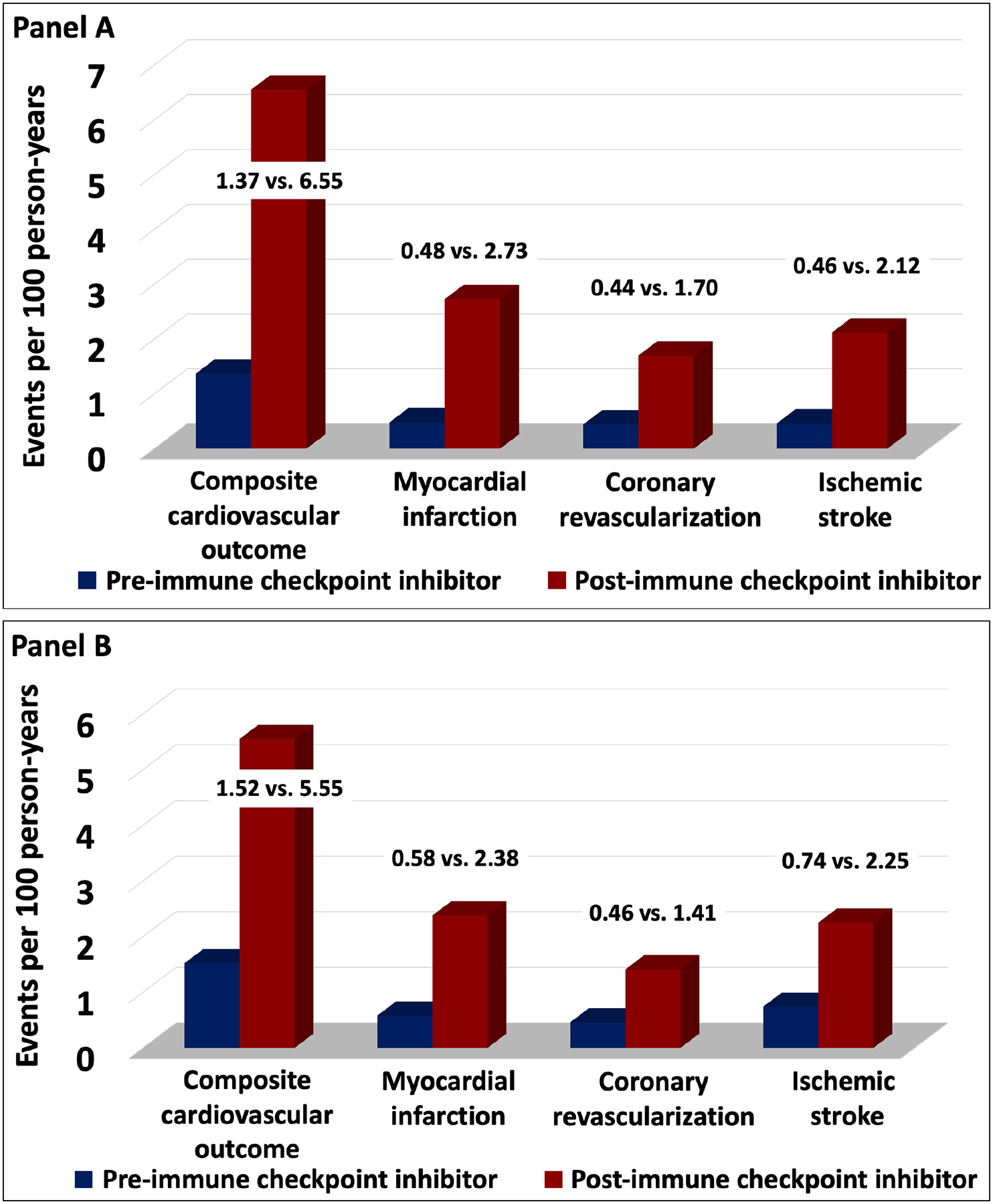

In the case-crossover study, the number of patients who had an event and the cumulative number of cardiovascular events were compared only among the 2842 patients that were treated with an ICI. Overall, among the 2842 patients that were treated with an ICI, 119 patients had a cardiovascular event during the two-year period after starting an ICI as compared with 66 patients in the two-year period before starting an ICI, a 4-fold increase from 1.37 to 6.55 per 100 person-years (adjusted HR, 4.8 [95% CI, 3.5–6.5]; P<0.001, Table 3). In the case-crossover study, there was also an increase in each of the individual component of the primary outcome (Figure 3, Table 3). The total numbers of events in the risk and control periods in the case-crossover study were also compared. Among the 2842 patients treated with an ICI, there were 139 events among the 119 patients during the two-year period post-ICI. In comparison, in the same cohort of 2842 patients, who subsequently were treated with an ICI, there were 78 events among the 66 patients during the two-year period pre-ICI (IRR, 1.8 [95% CI, 1.4–2.4]; P<0.001). Similar findings were also noted when the risk period and control period was restricted to one-year pre- and one-year post-ICI (Figure 3 and Table III in the Supplement), and findings of a higher risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular event with an ICI persisted after excluding individuals who died within 60 days of the event (Table IV in the Supplement).

Table 3.

The number of patients with an event and number of events, the rate per 100-person years from our cohort of 2842 cases and the hazard ratio for cardiovascular events. Cardiovascular events are compared for the two-year period pre-immune checkpoint inhibitor and two-year period post-immune checkpoint.

| Pre-treatment | Post-treatment | Hazard Ratio* (95% CI) | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome, n (%) | No. of patients with events % | Rate per 100 person-yr | No. of patients with events % | Rate per 100 person-yr | ||

| Cardiovascular events | 66 (2.32%) | 1.37 | 119 (4.2%) | 6.55 | 4.78 (3.50–6.53) | <0.001 |

| Outcome, n (%) | No. of events % | Rate per 100 person-yr | No. of events % | Rate per 100 person-yr | ||

| Myocardial infarction | 27 (0.95%) | 0.48 | 58 (2.04%) | 2.73 | 4.84 (2.76–8.09) | <0.001 |

| Coronary revascularization | 25 (0.87%) | 0.44 | 36 (1.26%) | 1.70 | 3.18 (1.46–6.10) | <0.001 |

| Ischemic stroke | 26 (0.91%) | 0.46 | 45 (1.58%) | 2.12 | 2.97 (1.41–5.53) | <0.001 |

Cox proportional hazard model

Figure 3. Cardiovascular events in the case-crossover study.

Panel A shows the composite cardiovascular outcomes in the two-year period pre-and post-immune checkpoint inhibitor.

Panel A includes the cardiovascular event rates per 100 person years from two-year prior to the start of an immune checkpoint inhibitor to two-year after starting an immune checkpoint inhibitor. The individual components of the primary outcome are also shown. Panel B shows the composite cardiovascular outcomes in the one-year period pre-and post-immune checkpoint inhibitor.

Sub-group analyses

In the sub-group analyses, a significant interaction was noted between baseline hypertension and ICI use (P=0.003, Figure IV in the Supplement), where the relative risk for a cardiovascular event was higher among patients without hypertension as compared with patients with hypertension (HR, 10.7 [95% CI, 6.1–18.8], vs. HR, 3.4 [95% CI, 2.4–4.9]). There was no relative difference in the risk for a cardiovascular event between males and females, those aged < 65 years vs. ≥ 65 years old, a body mass index < 30 kg/m2 vs. ≥ 30 kg/m2, a history of cardiovascular events, baseline diabetes, statin use, or a diagnosis of melanoma or lung cancer.

Imaging sub-study

The imaging study cohort included 40 patients with melanoma with computed tomography performed at three time points (Figure III in the Supplement). The clinical characteristics of the patients in the imaging sub-study, apart from cancer type, were not different to the main study cohort (Table V in the Supplement). The presence of cardiovascular risk factors, except for age, clinical variables, and the use of cardiac medications remained relatively constant throughout the study period (Table VI in the Supplement). There was an increase in the total and non-calcified plaque volume over the duration of the three scans (Table VII in the Supplement). The progression rate, adjusted for the study interval, was greater in the period after ICI as compared with prior, for both total (P=0.02) and non-calcified plaque (P=0.02, Table 4). Specifically, the rate of total plaque volume progression increased 3-fold from 2.1% per year pre- to 6.7% per year post-ICI. The rate of non-calcified plaque also increased after ICIs (Table VII in the Supplement). In stratified analysis, as compared with non-statin users, those on statins (n=18) showed a 3.1% absolute lower rate of plaque progression each year of total aortic plaque volume (5.2% vs. 8.3%, P=0.04) and a 3.9% absolute lower yearly rate of non-calcified plaque progression (3.1% vs 7.0%, P=0.04, Table 5). Similarly, among patients who were prescribed corticosteroids during checkpoint therapy there was a lower rate of plaque progression among those on corticosteroids (Table 5); specifically, the rate of non-calcified plaque progression was 3.5% per year among those prescribed a corticosteroid as compared with a rate of progression of 6.9% per year among those not prescribed a corticosteroid (total plaque volume, P=0.04).

Table 4.

Absolute and relative change in thoracic atherosclerotic plaque volume from before starting an immune checkpoint inhibitor (Scan 0-Scan 1) to after starting an immune checkpoint inhibitor (Scan 1 to Scan 2).

| Scan 0 - Scan 1 | Scan 1 – Scan 2 | * P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute change | Indexed change per year, mm3/year | Total plaque volume | 13.8 (−240, 122) | 103 (0, 511) | 0.02 |

| Non-calcified plaque volume | −18.2 (−274, 57) | 53 (0, 382) | 0.02 | ||

| Relative change | Indexed change per year, %/year | Total plaque volume | 2.1% (−13.0%, 18.6%) | 6.7% (2.2%, 28.1%) | 0.17 |

| Non-calcified plaque volume | −2.3% (−14.0%, 12.7%) | 5.3% (1.4%, 40.1%) | 0.14 |

Values are median (interquartile range).

P: Wilcoxon signed-rank test comparing annual rate of progression in plaque volume from scan 0 to scan 1 and from scan 1 to scan 2. The relative change is the change in the plaque volume per year.

Table 5.

Sub-group analysis of the change in plaque volume after starting an immune checkpoint inhibitor by statin and corticosteroid use.

| Statin – Yes | Statin – No | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plaque Measure - Values are median (IQR). | |||

| Total Aortic Plaque Volume | |||

| • Prior to checkpoint inhibitor (mm3) | 1903 (1038, 2661) | 1281 (358, 2691) | 0.38 |

| • Post checkpoint inhibitor (mm3) | 2214 (1730, 4090) | 1644 (588, 4211) | 0.32 |

| • Absolute change in total plaque (mm3/year) | 79.2 (0, 524) | 115 (0, 509) | 0.001 |

| • Relative change in total plaque volume (%/year) | 5.2% (0.6%, 23.7%) | 8.3% (4.7%, 42.5%) | 0.04 |

| Non-calcified Aortic Plaque Volume | |||

| • Prior to checkpoint inhibitor (mm3) | 1233 (956, 1835) | 998 (353, 2663) | 0.68 |

| • Post checkpoint inhibitor (mm3) | 1781 (1180, 3517) | 1631 (576, 3652) | 0.62 |

| • Absolute change in non-calcified plaque (mm3/year) | 45.3 (−38, 387) | 69.5 (0, 377) | 0.002 |

| • Relative change in non-calcified plaque volume (%/year) | 3.1% (−2.3%, 30.4%) | 7.0% (2.6%, 43.6%) | 0.04 |

| Corticosteroid - Yes | Corticosteroid - No | P Value | |

| Total Aortic Plaque Volume | |||

| • Prior to checkpoint inhibitor (mm3) | 1687 (751, 2661) | 1281 (655, 2691) | 0.65 |

| • Post checkpoint inhibitor (mm3) | 2161 (690, 4090) | 2214 (1193, 6165) | 0.77 |

| • Absolute change in plaque (mm3/year) | 61.8 (−52.8, 451) | 278 (38.0, 524) | 0.02 |

| • Relative change in total plaque volume (%/year) | 5.9% (−2.2%, 30.2%) | 7·4% (4.7%, 21.0%) | 0.04 |

| Non-calcified Aortic Plaque Volume | |||

| • Prior to checkpoint inhibitor (mm3) | 998 (530, 1835) | 1278 (654, 2663) | 0.71 |

| • Post checkpoint inhibitor (mm3) | 1548 (576, 2750) | 1968 (1180, 5029) | 0.28 |

| • Absolute change in non-calcified plaque volume (mm3/year) | 42.9 (−84.0, 290) | 80.3 (37.5, 494) | 0.02 |

| • Relative change in non-calcified plaque volume (%/year) | 3.5% (−11.3%, 43.4%) | 6·8% (3.1%, 22.3%) | 0.04 |

Discussion

The rate of atherosclerotic cardiovascular events was higher after starting an ICI. In a matched cohort study, ICI treatment was associated with a 3-fold higher risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular events as compared with cancer patients who did not have ICI. Similar findings of a higher risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular events were noted in a case-crossover study. In an imaging sub-study, there was a >3-fold increase in the rate of atherosclerotic plaque progression after initiation of ICI therapy. The association with increased atherosclerotic plaque was attenuated in patients with concomitant use of statins or corticosteroids, who had an approximate 50% reduction in plaque progression as compared with those not on statins or corticosteroids. Overall, these data suggest that patients treated with an ICI are at a higher risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular events, and that this risk is potentially mediated through accelerated atherosclerosis progression but may be modifiable. Our findings are important both for patients for whom ICIs are currently indicated but perhaps more so for the expanding pool of patients who are candidates for adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapy.

Data on the cardiac toxicities of ICIs have principally related to the development of myocarditis,24–26 where small cohort studies have suggested that myocarditis is an uncommon but potentially fatal complication.27–31 There are a limited number of prior studies testing the association between ICIs and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. In a single center case-control studies with 135 subjects, a single cancer type (non-small cell lung cancer) and a 6-month period of follow-up, there was no increase in cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, and hospitalization for heart failure with ICIs (HR, 1.2 [95% CI 0.6–2.4]; P=0.66).12 Similarly, in a study of 92 patients with non-small cell lung cancer, there was no increase in venous and arterial vascular events (pulmonary emboli, deep vein thrombosis, cerebrovascular accident, transient ischemic attack, and acute coronary syndrome) as compared with patients being treated with cytotoxic chemotherapy.10 In contrast, in a pooled analysis of 59 oncological trials submitted to the FDA for approval (sample size: 21,664), in comparison to traditional cytotoxic chemotherapies, there was a 35% (95% CI: 0.76–2.4) increase in coronary ischemia (defined using Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities Terminology), over 6 months of follow-up among patients on an ICI.11 Similarly, in a large retrospective meta-analysis including >20,000 immune checkpoint-treated patients, 9.8% of treatment-related deaths were from cardiovascular events, including heart failure, myocardial infarction, and the development of a cardiomyopathy.32 Consistent with prior studies in patients with cancer,33 we also found that older age, diabetes mellitus, ICI use, higher blood pressure, male sex, prior radiation treatment and a history of a cardiovascular event all increased the risk for a composite cardiovascular event. Combined with our data, these studies suggest a higher rate of atherosclerotic cardiovascular events with ICIs. For comparison, the event rate noted in this study (5% per year) is higher than the event rate noted in patients presenting with chest pain (~0.7% per year),13 in patients at risk of cardiovascular events (~0.3% per year),34 and in other at risk populations where immune activation and inflammation play a key role (e.g. persons with HIV, ~0.5% per year).35

Progression of atherosclerotic plaque is a robust predictor of atherosclerotic cardiovascular events and an established outcome measure for randomized clinical trials.36–38 Our imaging sub-study supports the biological plausibility of our clinical observations by demonstrating an association between ICI use with accelerated progression of atherosclerosis. The rate of plaque progression in our study (annually 6.7%) is nearly 3-times higher than reported in patients with subclinical (2.4% per year),39 and clinical cardiovascular disease (0.5–1.3% per year).40 Thus, the acceleration in atherosclerosis is substantial after an ICI and may be one mechanism by which there is an increase in incident cardiovascular events. However, there are other potential mechanisms by which ICIs can accelerate atherosclerosis. These other mechanisms particularly include vasculitis and focal myocarditis misdiagnosed as acute myocardial infarction.41 All diagnosed myocarditis cases were not included in the analysis but myocarditis remains a difficult diagnosis,42, 43 and not all patients underwent a coronary angiogram so vasculitis remains a possibility; however, the potential for immune checkpoint inhibition to accelerate atherosclerosis is strongly supported by animal and cellular models, where the same immune checkpoints being targeted for cancer are established negative regulators of atherosclerosis.6, 8, 44, 45 For example, the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway downregulates the proatherogenic T-cell response, and mice lacking PD-L1 had a 3-fold increase in atherosclerotic plaque with an associated increase in T-cells and macrophages.8, 44 Additionally, PD-1–deficient myeloid progenitors upregulate genes involved in cholesterol synthesis and uptake and downregulate genes promoting cholesterol metabolism, cumulatively leading to markedly increased cellular cholesterol levels.7 This latter finding is of particular relevance as statin use in our study was associated with reduced progression of atherosclerotic plaque after ICIs (annual progression rate of total plaque volume: 5.2% on statin vs. 8.3% not on statin; P=0.04). However, we did not find an association between statin use and cardiovascular events in our clinical study. This analysis testing the association with statin therapy on clinical outcomes may have been confounded by indication, with patients on a statin being at a higher baseline risk for events. We observed a similar trend for reduced atherosclerotic plaque in patients receiving corticosteroids. However, these latter findings should be interpreted with caution as the mechanisms involved are less clear as corticosteroids may increase blood sugar and blood pressure, and lead to lipid abnormalities and the association with corticosteroids on overall cancer outcomes is unclear.46 Moreover, while this observation may be related to the potential anti-inflammatory association with corticosteroids, it may also be cofounded by the indication for corticosteroids (immune mediated adverse events) where an ICI may be held or stopped if the adverse event is severe.

The primary limitation of our study is the retrospective nature of the study at a single center and the presence of missing data. However, our cohort of patients on ICI is over 20 times larger than any prior publication, the number of events was substantial, and the directionality of our findings is supported by prior smaller studies, overall providing much improved statistical power and thus confidence in our findings. Advantages and limitations relate to the use of the matched cohort and case-crossover designs,47, 48 and using these two designs together may remove the potential fixed and time-varying confounding effects of specific cardiovascular risk factors or age. Additionally, the risk of a cardiovascular event would not be expected to change three-fold over a period of two to four years and our results were consistent regardless of the analytical strategy. This was a retrospective study and it is possible that there remain several unmeasured residual confounders which may have influenced the association between ICI use and vascular events. These include physical activity, family history, and other active inflammatory ICI-related diseases such as a thyroid disease. An important limitation is that it is difficult to control for other variables which may change over time in a patient with cancer and which may also impact cardiovascular risk; however, we did not find significant changes over the study period in clinical variables (e.g. blood pressure) or cardiovascular medication use in either the clinical or the imaging cohort. A limitation of this study design would be whether the exposure to an ICI were altered by a previous cardiovascular event. However, prior cardiovascular disease is not a contraindication to ICI use,49 is not an exclusion from most of clinical trials testing the efficacy of ICI,4, 16, 50, 51 and until, this publication, the potential for an association between cardiovascular events and ICIs were not established. Additionally, it should be noted that the median number of cycles of ICIs was between four and five cycles and cycles are administered every two to three weeks while the risk period was longer at two years for the primary analysis and one year for the secondary analysis. Combination ICI therapy has been associated with a higher risk for myocarditis. In this study, there was no association between combination ICI use and atherosclerotic cardiovascular event; however, only 6.9% of the patients were treated with combination ICIs thus limiting the interpretation of this negative finding. Immune checkpoint inhibitors are associated with an increase in inflammation. However, routine measures of inflammation such as measures of cytokines and C-Reactive Protein were not performed, would be affected by the presence and cancer trajectory, and thus we are unable to test the association between inflammation secondary to ICIs and atherosclerosis or atherosclerosis-related events. We did measure other related markers such as the white blood cell count, neutrophil count, and lymphocyte count and found no difference between those with and without events and no change over time. We also considered whether the increase in the event rate may have reflected a change in the goals of treatment after a major vascular event among patients with predominately late stage cancer. Specifically, whether late stage cancer influenced the treatment decisions after a major vascular event and led to a shorter follow-up period and a higher rate of events. For example, there was a significantly higher rate of myocardial infarction in comparison to the modest increase in coronary revascularization. Whether the relative risk of an event would be as high in patients with early stage cancer with a longer cancer-related survival is less clear and will need to be studied in future cohorts.

In conclusion, in this study, there was a higher rate of cardiovascular events after starting an ICI. The study provides additional biological plausibility of the clinical findings by finding greater atherosclerotic plaque progression after starting an ICI and we provide initial data suggesting that this effect can be modified. Taken together, these data provide a rationale to consider an approach treating immune checkpoint therapy as a modifier of cardiovascular risk and suggest that candidates for ICI therapy should undergo a comprehensive cardiovascular risk evaluation and optimization of preventive medical therapy with close monitoring thereafter.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspective.

What is New?

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are associated with a 3-fold higher risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular events including myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization and ischemic stroke.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are associated with a >3-fold higher rate of aortic plaque progression.

The increase in aortic atherosclerotic plaque was modified by concomitant statin and corticosteroid use.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Optimization of cardiovascular risk factors prior to, during and after treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors is warranted.

There needs to be an increased awareness of atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk during and after treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Acknowledgments:

We gratefully acknowledge the Cardiovascular Imaging Research Center (CIRC) research team for providing feedback on the study design and interpretation; The CIRC is a combined effort from the Division of Cardiology and the Department of Radiology at Massachusetts General Hospital. TN and UH had full access to the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. ZD, TN, UH, LZ, RA, RS, KR and JT drafted the study protocol and analysis plan. ZD, JT, AZ, SM, PR, RM, CL, DZ, VR, SH, HG, JG, LZ, TM, UH and TN helped with the data acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data. All authors contributed to the data collection, and the design, analysis, interpretation drafting of the manuscript.

Funding/Support: Dr. Neilan is supported by a gift from A. Curt Greer and Pamela Kohlberg, and grants from the National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants R01HL130539, R01HL137562, K24HL150238, and National Institutes of Health/Harvard Center for AIDS Research grant P30 AI060354; Dr. Alvi, Dr. Zafar and Dr. Raghu are supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant T32HL076136. Dr Taron is funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation, TA 1438/1-2). Dr. Hoffmann is receiving grants on behalf of Massachusetts General Hospital from KOWA, MedImmune, HeartFlow, Duke University (Abbott), Oregon Health & Science University (American Heart Association, 13FTF16450001), Columbia University (National Institutes of Health, R01HL109711), National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute K24HL113128, T32HL076136, and U01HL123339.

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms:

- CI

Confidence interval

- CTLA-4

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4

- HR

Hazard ratio

- ICI

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

- IRR

Incidence rate ratio

- PD-1

Programmed cell death protein 1

- PD-L1

Programmed death-ligand 1

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr. Neilan has been a consultant to and received fees from Parexel Imaging, Intrinsic Imaging, H3-Biomedicine, AbbVie, and Syros Pharmaceuticals, outside of the current work. Dr. Neilan also reports consultant fees from Bristol Myers Squibb for a Scientific Advisory Board focused on myocarditis related to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Dr. Hoffmann reports consulting fees from: Abbott, Duke University (NIH), Recor Medical; outside the submitted work. Dr. Sullivan has been a consultant to Asana, Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck, Replimune; and received research funding from Amgen and Merck, all outside of the current work. Other authors have no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures.

Supplemental Material:

Supplemental Methods; Documents I - II

Supplemental Tables I – VII

Supplemental Figures and Figure Legends I - IV

References

- 1.Ribas A and Wolchok JD. Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade. Science. 2018;359:1350–1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang J, Shalabi A and Hubbard-Lucey VM. Comprehensive analysis of the clinical immuno-oncology landscape. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haslam A and Prasad V. Estimation of the Percentage of US Patients With Cancer Who Are Eligible for and Respond to Checkpoint Inhibitor Immunotherapy Drugs. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(5);e192535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eggermont AMM, Blank CU, Mandala M, Long GV, Atkinson V, Dalle S, Haydon A, Lichinitser M, Khattak A, Carlino MS et al. Adjuvant Pembrolizumab versus Placebo in Resected Stage III Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1789–1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antonia SJ, Villegas A, Daniel D, Vicente D, Murakami S, Hui R, Yokoi T, Chiappori A, Lee KH, de Wit M et al. Durvalumab after Chemoradiotherapy in Stage III Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1919–1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernandez DM, Rahman AH, Fernandez NF, Chudnovskiy A, Amir ED, Amadori L, Khan NS, Wong CK, Shamailova R, Hill CA et al. Single-cell immune landscape of human atherosclerotic plaques. Nat Med. 2019;25:1576–1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strauss L, Mahmoud MAA, Weaver JD, Tijaro-Ovalle NM, Christofides A, Wang Q, Pal R, Yuan M, Asara J, Patsoukis N et al. Targeted deletion of PD-1 in myeloid cells induces antitumor immunity. Sci Immunol. 2020;5(43);eaay1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gotsman I, Grabie N, Dacosta R, Sukhova G, Sharpe A and Lichtman AH. Proatherogenic immune responses are regulated by the PD-1/PD-L pathway in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2007;117:2974–2982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gelsomino F, Fiorentino M, Zompatori M, Poerio A, Melotti B, Sperandi F, Gargiulo M, Borghi C and Ardizzoni A. Programmed death-1 inhibition and atherosclerosis: can nivolumab vanish complicated atheromatous plaques? Ann Oncol. 2018;29:284–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bar J, Markel G, Gottfried T, Percik R, Leibowitz-Amit R, Berger R, Golan T, Daher S, Taliansky A, Dudnik E et al. Acute vascular events as a possibly related adverse event of immunotherapy: a single-institute retrospective study. Eur J Cancer. 2019;120:122–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amiri-Kordestani L, Moslehi J, Cheng C, Tang S, Schroeder R, Sridhara R, Karg K, Connolly J, Beaver JA, Blumenthal GM et al. Cardiovascular adverse events in immune checkpoint inhibitor clinical trials: A U.S. Food and Drug Administration pooled analysis. Journal of Clinical Oncology, no 15_suppl 2018;36:3009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chitturi KR, Xu J, Araujo-Gutierrez R, Bhimaraj A, Guha A, Hussain I, Kassi M, Bernicker EH and Trachtenberg BH. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Related Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Patients With Lung Cancer. JACC: CardioOncology. 2019;1:182–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Douglas PS, Hoffmann U, Patel MR, Mark DB, Al-Khalidi HR, Cavanaugh B, Cole J, Dolor RJ, Fordyce CB, Huang M et al. Outcomes of anatomical versus functional testing for coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1291–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffmann U, Truong QA, Schoenfeld DA, Chou ET, Woodard PK, Nagurney JT, Pope JH, Hauser TH, White CS, Weiner SG et al. Coronary CT angiography versus standard evaluation in acute chest pain. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:299–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hicks KA, Mahaffey KW, Mehran R, Nissen SE, Wiviott SD, Dunn B, Solomon SD, Marler JR, Teerlink JR, Farb A et al. Standardized Data Collection for Cardiovascular Trials I. 2017 Cardiovascular and Stroke Endpoint Definitions for Clinical Trials. Circulation. 2018;137:961–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolchok JD, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, Rutkowski P, Grob JJ, Cowey CL, Lao CD, Wagstaff J, Schadendorf D, Ferrucci PF et al. Overall Survival with Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1345–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rogers IS, Massaro JM, Truong QA, Mahabadi AA, Kriegel MF, Fox CS, Thanassoulis G, Isselbacher EM, Hoffmann U and O’Donnell CJ. Distribution, determinants, and normal reference values of thoracic and abdominal aortic diameters by computed tomography (from the Framingham Heart Study). Am J Cardiol. 2013;111:1510–1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamirani YS, Kadakia J, Pagali SR, Zeb I, Isma’eel H, Ahmadi N, Sarraf G, Choi T, Patel A and Budoff MJ. Assessment of progression of coronary atherosclerosis using multidetector computed tomography angiography (MDCT). Int J Cardiol. 2011;149:270–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schuhbaeck A, Dey D, Otaki Y, Slomka P, Kral BG, Achenbach S, Berman DS, Fishman EK, Lai S and Lai H. Interscan reproducibility of quantitative coronary plaque volume and composition from CT coronary angiography using an automated method. Eur Radiol. 2014;24:2300–2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Versteylen MO, Kietselaer BL, Dagnelie PC, Joosen IA, Dedic A, Raaijmakers RH, Wildberger JE, Nieman K, Crijns HJ, Niessen WJ et al. Additive value of semiautomated quantification of coronary artery disease using cardiac computed tomographic angiography to predict future acute coronary syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:2296–2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lo J, Lu MT, Ihenachor EJ, Wei J, Looby SE, Fitch KV, Oh J, Zimmerman CO, Hwang J, Abbara S et al. Effects of statin therapy on coronary artery plaque volume and high-risk plaque morphology in HIV-infected patients with subclinical atherosclerosis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet HIV. 2015;2:e52–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baker MA, Lieu TA, Li L, Hua W, Qiang Y, Kawai AT, Fireman BH, Martin DB and Nguyen MD. A vaccine study design selection framework for the postlicensure rapid immunization safety monitoring program. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;181:608–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glanz JM, McClure DL, Xu S, Hambidge SJ, Lee M, Kolczak MS, Kleinman K, Mullooly JP and France EK. Four different study designs to evaluate vaccine safety were equally validated with contrasting limitations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59:808–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson DB, Balko JM, Compton ML, Chalkias S, Gorham J, Xu Y, Hicks M, Puzanov I, Alexander MR, Bloomer TL et al. Fulminant Myocarditis with Combination Immune Checkpoint Blockade. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1749–1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moslehi JJ, Salem JE, Sosman JA, Lebrun-Vignes B and Johnson DB. Increased reporting of fatal immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated myocarditis. Lancet. 2018;391:933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michel L, Rassaf T and Totzeck M. Cardiotoxicity from immune checkpoint inhibitors. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2019;25:100420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahmood SS, Fradley MG, Cohen JV, Nohria A, Reynolds KL, Heinzerling LM, Sullivan RJ, Damrongwatanasuk R, Chen CL, Gupta D et al. Myocarditis in Patients Treated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:1755–1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang L, Awadalla M, Mahmood SS, Nohria A, Hassan MZO, Thuny F, Zlotoff DA, Murphy SP, Stone JR, Golden DLA et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated myocarditis. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(18):1733–1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Awadalla M, Mahmood SS, Groarke JD, Hassan MZO, Nohria A, Rokicki A, Murphy SP, Mercaldo ND, Zhang L, Zlotoff DA et al. Global Longitudinal Strain and Cardiac Events in Patients With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Related Myocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:467–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang L, Zlotoff DA, Awadalla M, Mahmood SS, Nohria A, Hassan MZO, Thuny F, Zubiri L, Chen CL, Sullivan RJ et al. Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events and the Timing and Dose of Corticosteroids in Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Associated Myocarditis. Circulation. 2020;141:2031–2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Awadalla M, Golden DLA, Mahmood SS, Alvi RM, Mercaldo ND, Hassan MZO, Banerji D, Rokicki A, Mulligan C, Murphy SPT et al. Influenza vaccination and myocarditis among patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Y, Zhou S, Yang F, Qi X, Wang X, Guan X, Shen C, Duma N, Vera Aguilera J, Chintakuntlawar A et al. Treatment-Related Adverse Events of PD-1 and PD-L1 Inhibitors in Clinical Trials: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:1008–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koene RJ, Prizment AE, Blaes A and Konety SH. Shared Risk Factors in Cardiovascular Disease and Cancer. Circulation. 2016;133:1104–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rana JS, Tabada GH, Solomon MD, Lo JC, Jaffe MG, Sung SH, Ballantyne CM and Go AS. Accuracy of the Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Risk Equation in a Large Contemporary, Multiethnic Population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:2118–2130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosenson RS, Hubbard D, Monda KL, Reading SR, Chen L, Dluzniewski PJ, Burkholder GA, Muntner P and Colantonio LD. Excess Risk for Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Outcomes Among US Adults With HIV in the Current Era. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e013744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Azen SP, Mack WJ, Cashin-Hemphill L, LaBree L, Shircore AM, Selzer RH, Blankenhorn DH and Hodis HN. Progression of coronary artery disease predicts clinical coronary events. Long-term follow-up from the Cholesterol Lowering Atherosclerosis Study. Circulation. 1996;93:34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nissen SE, Tuzcu EM, Schoenhagen P, Brown BG, Ganz P, Vogel RA, Crowe T, Howard G, Cooper CJ, Brodie B et al. Effect of intensive compared with moderate lipid-lowering therapy on progression of coronary atherosclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1071–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nicholls SJ, Ballantyne CM, Barter PJ, Chapman MJ, Erbel RM, Libby P, Raichlen JS, Uno K, Borgman M, Wolski K et al. Effect of two intensive statin regimens on progression of coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2078–2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee SE, Chang HJ, Sung JM, Park HB, Heo R, Rizvi A, Lin FY, Kumar A, Hadamitzky M, Kim YJ et al. Effects of Statins on Coronary Atherosclerotic Plaques: The PARADIGM Study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11:1475–1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nissen SE, Tuzcu EM, Libby P, Thompson PD, Ghali M, Garza D, Berman L, Shi H, Buebendorf E, Topol EJ et al. Effect of antihypertensive agents on cardiovascular events in patients with coronary disease and normal blood pressure: the CAMELOT study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292:2217–2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lyon AR, Yousaf N, Battisti NML, Moslehi J and Larkin J. Immune checkpoint inhibitors and cardiovascular toxicity. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:e447–e458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neilan TG, Rothenberg ML, Amiri-Kordestani L, Sullivan RJ, Steingart RM, Gregory W, Hariharan S, Hammad TA, Lindenfeld J, Murphy MJ et al. Myocarditis Associated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: An Expert Consensus on Data Gaps and a Call to Action. Oncologist. 2018;23:874–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bonaca MP, Olenchock BA, Salem JE, Wiviott SD, Ederhy S, Cohen A, Stewart GC, Choueiri TK, Di Carli M, Allenbach Y et al. Myocarditis in the Setting of Cancer Therapeutics: Proposed Case Definitions for Emerging Clinical Syndromes in Cardio-Oncology. Circulation. 2019;140:80–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bu DX, Tarrio M, Maganto-Garcia E, Stavrakis G, Tajima G, Lederer J, Jarolim P, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH and Lichtman AH. Impairment of the programmed cell death-1 pathway increases atherosclerotic lesion development and inflammation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:1100–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsumoto T, Sasaki N, Yamashita T, Emoto T, Kasahara K, Mizoguchi T, Hayashi T, Yodoi K, Kitano N, Saito T et al. Overexpression of Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte-Associated Antigen-4 Prevents Atherosclerosis in Mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36:1141–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Faje AT, Lawrence D, Flaherty K, Freedman C, Fadden R, Rubin K, Cohen J and Sullivan RJ. High-dose glucocorticoids for the treatment of ipilimumab-induced hypophysitis is associated with reduced survival in patients with melanoma. Cancer. 2018;124:3706–3714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kwong JC, Schwartz KL, Campitelli MA, Chung H, Crowcroft NS, Karnauchow T, Katz K, Ko DT, McGeer AJ, McNally D et al. Acute Myocardial Infarction after Laboratory-Confirmed Influenza Infection. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:345–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smeeth L, Thomas SL, Hall AJ, Hubbard R, Farrington P and Vallance P. Risk of myocardial infarction and stroke after acute infection or vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2611–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johnson DB, Sullivan RJ and Menzies AM. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in challenging populations. Cancer. 2017;123:1904–1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hellmann MD, Ciuleanu TE, Pluzanski A, Lee JS, Otterson GA, Audigier-Valette C, Minenza E, Linardou H, Burgers S, Salman P et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in Lung Cancer with a High Tumor Mutational Burden. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2093–2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Forde PM, Chaft JE, Smith KN, Anagnostou V, Cottrell TR, Hellmann MD, Zahurak M, Yang SC, Jones DR, Broderick S et al. Neoadjuvant PD-1 Blockade in Resectable Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1976–1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.