Abstract

Background:

Burn injury (BI) pain consists of inflammatory and neuropathic components and activates microglia. Nicotinic α7acetylcholine receptors (α7AChRs) expressed in microglia exhibit immuno-modulatory activity during agonist stimulation. Efficacy of selective α7AChR agonist, GTS-21 to mitigate BI pain and spinal pain-mediators was tested.

Methods:

Anesthetized rats after hind-paw BI received intraperitoneal GTS-21 or saline daily. Allodynia and hyperalgesia were tested on BI and contralateral paw for 21 days. Another group, after BI receiving GTS-21 or saline had lumbar spinal cord segments harvested (day 7 or 14) to quantify spinal inflammatory-pain transducers or microglia activation using fluorescent marker, Iba1.

Results:

BI significantly decreased allodynia withdrawal threshold from baseline of ~9–10g to ~0.5–1g, and hyperalgesia-latency from ~16–17secs to ~5–6secs by day 1. Both doses of GTS-21 (4 or 8 mg/kg) mitigated burn-induced allodynia from ~0.5–1g to ~2–3g threshold (p = 0.089 and p = 0.010), and hyperalgesia from ~5–6 secs to 8–9 secs (p < 0.001 and p < 0.001) by day 1. GTS-21 group recovered to baseline pain threshold by day 15–17 compared to saline-treated, where the exaggerated nociception persisted beyond 15–17 days. BI significantly (p<0.01) increased spinal cord microgliosis (identified by fluorescent Iba1 staining), microglia activation (evidenced by the increased inflammatory cytokine and pain-transducer (protein and/or mRNA) expression (tumor necrosis factor - α [TNF- α], interleukin-1β [IL-1β], nuclear factor-k beta [NF-kB], interleukin-6 [IL-6], Janus associated kinase signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 [JAK-STAT3] and/or N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor [NMDAR]). GTS-21 mitigated pain-transducer changes. α7AChR antagonist, methyllycaconitine, nullified the beneficial effects of GTS-21 on both increased nociception and pain-biomarker expression.

Conclusions:

Non-opioid, α7AChR agonist, GTS-21 elicits anti-nociceptive effects at least in part by decreased activation spinal-cord pain-inducers. The α7AChR agonist, GTS-21 holds promise as potential therapeutic adjunct to decrease BI pain by attenuating both microglia changes and expression of exaggerated pain transducers.

Keywords: α7AChR agonist, allodynia, burn injury, GTS-21, hyperalgesia, injury-pain, microglia, nociception, pain-related molecules, pain transducers, pain relief

Introduction

Approximately 11 million globally and ~500,000 humans in the US are affected annually by burn injury (BI); majority are males and ~30% <16 years old. 1 * Exaggerated pain is a concomitant feature of BI. Pharmacotherapy of BI pain has posed continuing challenges for caregivers because of poor response to opioids, particularly in children. 2,3 Untreated pain can cause post-traumatic-stress disorder, 4–6 and/or chronic pain.7 Repetitive opioid administration can lead to opioid dependence, opioid withdrawal during weaning and/or opioid-induced hyperalgesia. 8 Thus, it is paramount to define the molecular mechanisms underlying BI pain, and discover new, non-opioid drugs to mitigate BI pain.

Partial nerve injury and complete Freud’s adjuvant-injection to rodents have been used to study contributions of neuropathy- and inflammation-related exaggerated nociception, respectively. 9–12 BI is associated with both local and/or systemic inflammatory responses. 13–15 BI damages nerves of both skin and often deeper tissues.15 Thus, BI pain has both inflammatory and neuropathic components. Markers of inflammation include increased tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF- α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and nuclear factor-kappa-B (NF-kB) expression. 16 Interleukin-6 (IL-6) release and/or increased N-methyl D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) expression are considered putative markers of chronic neuropathic pain.17,18

Microgliosis and/or activation of microglia with cytokine release is seen in both inflammatory and neuropathic pain conditions. 14,15,19 Even a small BI to hind-paw leads to exaggerated nociception in association with microglia proliferation (microgliosis), as evidenced by the fluorescent ionized calcium-binding adaptor protein (Iba1) staining. 14,15,20 Microglia, the macrophage-like cells of the central nervous system (CNS), when activated release inflammatory cytokines/chemokines, which sensitize neurons. 11,19

*http://ameriburn.org/who-we-are/media/burn-incidence-fact-sheet/

Thus, immune signals can cause elevated neuronal sensitization and heightened pain state. 11,12,14,15,19

Nicotinic α7 acetylcholine receptors (α7AChRs) are constitutively expressed in microglia and de novo in muscle during pathologic muscle-wasting. 21–23 Agonist stimulation of the leucocyte α7AChRs has anti-inflammatory properties, evidenced as decreased cytokine release. 22–24 GTS-21 is a highly selective α7AChR agonist, 25 and its administration elicits anti-inflammatory effects. 22,24,26 In a neuropathic pain model, α7AChR stimulation abated pain behaviors. 27 BI pain, consists of both inflammatory and neuropathic components but efects of α7AChRs stimulation on BI pain remains unknown. Since mitigation of BI pain in pediatric patients is a serious issue for caregivers, 2,3 this study used the young rat model. 20 The hypothesis tested was that GTS-21 stimulation of microglia α7AChRs mitigates exaggerated BI pain in association with suppression of putative neuropathic and inflammatory pain-mediators expressed in spinal cord.

Methods

Experimental Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) weighing 60 ± 5 g and 3-weeks old were used. Their individual housing had 12-hour light/dark cycles with access to water and food pellets. The experimental protocol (2016N0007) was approved by MGH IACUC.

Hind Paw Burn Injury

The BI procedure in rats has been described. 20,28 Briefly, under isoflurane anesthesia (1.5 to 2%), the right hind-paw dorsal area was immersed into a 85°C hot-water bath for 12s. BI area was limited by exposing the paw firmly against a plastic template. This causes a third-degree BI producing exaggerated nociception. 20,28 Silver-sulfadiazine ointment was applied b.i.d. to the injured surface. After BI, food, water intake and movements were normal with no signs of distress.

Drugs and Treatments

BI rats were randomly assigned to receive intraperitoneal saline (Control) or GTS-21 (4 or 8 mg/kg), b.i.d. for one week. Two other groups of BI rats received methyllcaconitine (MLA, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, 3 mg/ kg) alone or with GTS-21 (4mg/kg). MLA is a specific α7AChR blocker (Figure 1). 24 Preliminary evaluation at the end of one week after BI revealed that mitigation of hyperalgesia was not different between 4 and 8 mg/kg doses (See Supplemental Table S1B and Figure S2B). Hence, experiments beyond day 7 were performed using twice-daily GTS-21 (4 mg/kg) or saline injections for 14 days but behavioral studies continued for 21 days.

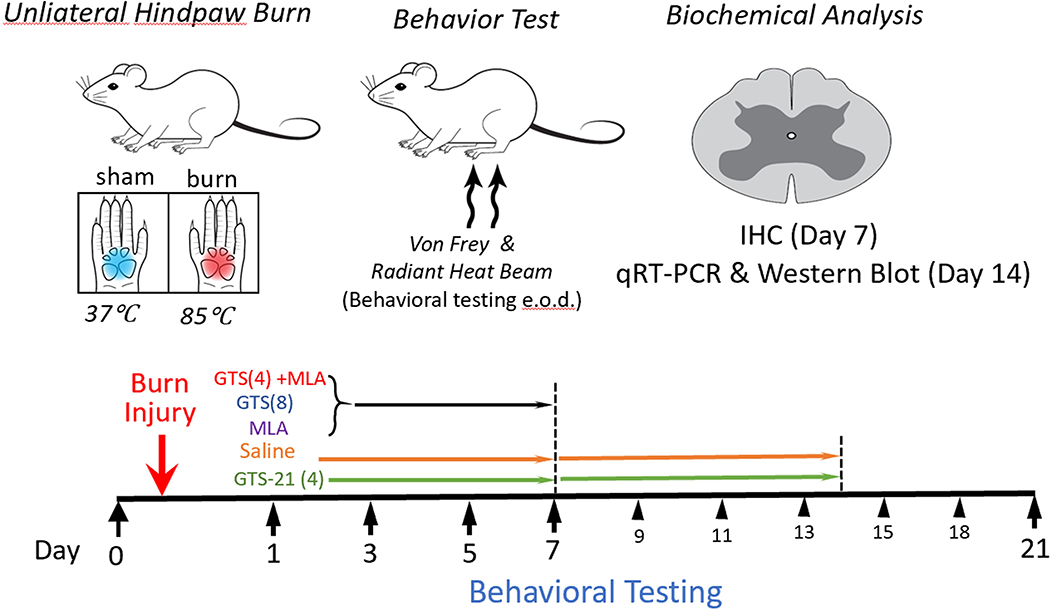

Figure 1. Schematic (flow chart) of the different studies.

Rats were given burn injury (BI) to the ipsilateral lateral and sham burn (SB) to the contralateral side on day 0. Behavioral studies (Von-Frey fiber testing for allodynia and radiant heat testing for hyperalgesia) were performed at baseline and at 1, 3, 5 and 7days initially. The rats (n=6 per group) were randomly assigned to receive intraperitoneal saline (Control) or GTS-21 (4 or 8 mg/kg), b.i.d. for one week. Two other groups of BI rats received methyllcaconitine (MLA, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, 3 mg/ kg) alone or with GTS-21 (4mg/kg). MLA is a specific α7AChR blocker for 1 week. Preliminary evaluation at the end of one week after BI revealed that mitigation of hyperalgesia was not different between 4 and 8 mg/kg doses. Hence, the drug administration was continued only in two groups (saline and GTS-21 4 mg/kg) for 14 days but the behavioral studies were continued till day 21. In a new set of animals BI was given above and Saline or 4 mg/kg was administered for 14 day after which dorsal spinal segements (L4–5) were removed for analyses of spinal inflammatory and neuropathic pain biomarkers. In another set of animals (n=3), after BI injury or SB and Saline or 4 mg/kg GTS-21, the lumbar dorsal segments were excised at day 7 for immunohistochemistry of microglia.

Behavioral assessments

Animals (n=6 per group, 5 groups) were habituated to the testing environment for 3 days before the first behavioral test day. Habituation consisted of exposing rats to the testing room and apparatus for 30min. Behavioral assessments (allodynia and hyperalgesia) were carried out pre-burn (Day 0) and at days 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 18 and 21 post-BI. Withdrawal latency (seconds) to radiant heat and Von- Frey mechanical filaments bending threshold (grams) were examined on both ipsilateral and contralateral (Control) sides before drug administration on each test day. Rats were euthanized after the final behavioral test at day 7 or 21, day 7 or 14 for assessing spinal cord microglia or pain biomarkers changes.

Mechanical allodynia

Von-Frey filament thresholds (allodynia) were determined on ipsilateral and contralateral sides as previously described. 20,28,29 Each rat was placed in a plexiglass enclosure on a metal mesh floor. Von-Frey mechanical stimulation was applied to the plantar surface of each paw. Each trial consisted of five applications of the same filament every 4 seconds, and the cutoff force was 10g. Brisk foot withdrawals (at least three times of five applications) to Von-Frey stimulation were considered positive. Depending on the initial response, subsequent filaments were applied in the order of either descending or ascending force to determine the thresholds.

Thermal hyperalgesia

Withdrawal latencies to radiant heat (hyperalgesia) were determined in the same animals using a 390 Analgesia Meter (IITC Inc., Woodland Hills, CA), as described.20,28,29 Rats were individually placed on a transparent glass surface in plexiglass enclosures. The light beam was directed at the plantar surface of each paw. Paw withdrawal latency was defined as time from onset of radiant heat to withdrawal. Heat intensity was adjusted to a baseline latency ~15–16s and a cut-off time of 20s. Two trials five minutes apart were made for each paw and latencies averaged.

Assessment of spinal cord pain biomarkers

To study mechanisms by which GTS-21 improved nociception, separate rats were used (n = 4 per group). Spinal cord samples were collected at post-burn day 14 after receiving the following treatments b.id.: (i) GTS-21 (4 mg/kg), (ii) saline, (iii) GTS-21 with MLA (3 mg/kg) and (iv) MLA alone (Figure 1). The spinal (L4–5) segments were divided into dorsal and ventral segments, the dorsal segments separated into ipsilateral and contralateral sides and rapidly frozen on dry ice and stored at −80°C; samples were later used for biomarker assessment. The saline-treated contralateral side was “Control”. Changes in neuropathic pain-biomarkers (e.g., IL-6, NR1 subunit of NMDA receptor [NMDAR1], and phosphorylated STAT3 = pSTAT3) and inflammation-related markers (e.g., NF-kB, IL-1β and TNF-α) were measured by Western blots or quantitative RT-PCR.

Western blots

Dorsal spinal-cord ipsilateral and contralateral sides were used. The tissues (n=4 per group) were homogenized in homogenization buffer and centrifuged at 4°C for 10min at 7,000×g. Protein concentration were measured using microplate reader (Bio-TeK Instrument, Winooski, VT). Protein (30μg) were denatured for 10min at 100°C, loaded onto SDS-polyacrylamide gels for protein separation, transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Burlington, MA); membrane was blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk solution and subsequently incubated at 4°C overnight with a primary antibody. Primary antibodies, their dilutions and molecular weights were: rabbit anti-rat NR1 of NMDAR, 1:2000; 106kDa (Sigma-Aldrich), rabbit anti-rat NF-κB-p65, 1:1000; 65kDa and rabbit anti-phospho-Stat3, 1:1000, 88kDa (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA). A corresponding horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Donkey anti-rabbit, 1:7,000; Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL) and chemiluminescent solution (NEN® Life-Science, Boston, MA) were used to visualize the blots, by exposing them hyper-film (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL) for 5min, later incubation in a stripping buffer for 30min at room temperature and re-probed with a polyclonal rabbit anti-rat β-actin antibody (1:10,000; Alpha Diagnostic, San Antonio, TX) as a loading control. Tissues from each treatment group were probed in triplicate and band density measured with Adobe Photoshop (normalized to β-actin loading-control).

Quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR).

For these (n = 3/group), the dorsal ipsilateral and contralateral sides of BI rats treated only with saline or GTS-21 were used. Total tissue RNA was extracted with RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) per manufacturer’s instruction. The cDNA was synthesized by RT2 Easy First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) per manufacturer’s instruction. Quantitative RT-PCR was carried out in duplicate using preoptimized TaqMan primer/probe mixture and TaqMan universal PCR master-mix (Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Cambridge, MA ) on a 7500 real-time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The cDNA quantities between different reactions were normalized using housekeeping gene GAPDH (cat. No. 4331182; Thermo-Fisher-Scientific, Cambridge, MA) as a reference. The values represent X-fold differences from contralateral side sample (Control, given a designated value of 1) within each experiment. The gene assay identification are as follows: IL-1β (Rn00580432_m1); IL-6 (Rn01410330_m1), TNFα (Rn99999017_m1), and NF-κB (Rn01399572_m1).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) of the spinal Cord

After BI, GTS-21 or saline-treatment (n = 3), IHC to detect microglia changes was performed using anti-Iba1. 20,30 Rats were anesthetized as described, chest opened, a needle was inserted through the heart and ascending aorta perfused via infusion pump with 200ml of 0.01m phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.35) followed by 300ml paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M in PBS. Then, spinal segments were excised, post fixed (4% formaldehyde) and kept in sucrose (10%) for 4h, sucrose(20%) for 8h and then sucrose(30%) overnight. After tissue dehydration, spinal segments were paraffin embedded, sectioned with a cryostat (8μm thick), mounted on Shandon™ Polysine slides (Fisher-Scientific, Waltham, MA) and stored at −20oC. All IHC sections were treated under the same conditions on the same day to minimize the between-group variability. Sections were blocked (1.5% goat serum and 0.04% Saponin in 1% bovine serum albumin) for 1h, incubated overnight at 4oC with primary antibody, rabbit anti Iba1(1:150, Wako-Pure Industries, Richmond, VA) and incubated for 90min with anti-rabbit Alexa 568 (1:300; Invitrogen, Grand Island). Randomly-selected IHC images were scanned using a confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 800; Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Thornwood, NY). Photoshop program (Volocity 6.3, Perkin Elmer, Inc) was used for quantitation of expression of Iba1.

Power Analysis

There was no a priori power analysis conducted for sample size estimation. In our previous conducted experiments, we used 6–12 animals per study group for behavioral testing, and 3–6 subjects for western blots and/or immunochemistry measurements. 20,28,29,31 These sample size estimations would yield approximately effect size of Cohen’s D ranged from 1.2 to 1.8 for behavioral tests and 1.8 to 3.1 for biochemical assessments based on two independent sample t-tests setting alpha = 0.05 and power = 0.8. These effect sizes were considered to be quite large. But these large between-group differences are expected based on domain-specific medical theories, when clinical/scientific significance also had been observed in our prior studies.20,28,29,31

Statistical Analyses

Numeric data were summarized as mean/standard deviation (SD) or median/quantiles (Q1, Q3) based on data distribution. We utilized a Linear Mixed Effects model (LMM) approach for analyzing behavioral assessment data. Considering our study involved two phases (day 1–7 and 1–21) with different study purposes, we first ran a full-factorial LMM including study groups, paw-side (ipsilateral, contralateral), phase of injury, along with all interactions as fixed terms to decide whether subjects perform differently under different paw-sides and phases (significant interaction terms). If so, study data would be analyzed using sub-models by phase of injury and paw-side, respectively. Specifically, the first type of model is “injury phase” model constructed, which contains all study data of 5 study groups collected from day 1 to day 7 describing the responses in the acute burn-injury phase. The second type of model, defined as the “full trajectory” model, contains all study data of only 4 mg/kg GTS-21 and saline-treated group from day 1–21. This model describes the “full trajectory” of the study groups in both acute-injury and recovery-phases.

Both these two types of models shared a linear mixed effects modeling structure, which is commonly described as the Growth Curve Modeling (GCM) approach. We applied animal IDs as random intercepts with/without time points (or its polynomial forms) as random slopes. Using baseline outcome value at time-point 0 as the covariate, the 5 study groups for injury models, and 2 for full trajectory models, timepoints (continuous variable in days from day 1–7, or day 1–21) and potentially polynomial terms of time or group-by-time interaction terms depending on different data distributions, data were analyzed. Dependent variables are in forms of either raw outcome values (i.e., mechanical or withdrawal latency thresholds) or their log-transformations to achieve the best model goodness of fit. Model comparisons were performed using Likelihood ratio tests, and analyses at exact timepoints were conducted using two-sided t-tests, assuming good fitness of our mixed-effect model. More details regarding our modeling approach are included in the Supplemental Content.

Western blot data were first normalized using β-actin levels and then analyzed using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to detect differences of protein levels among each study groups. Quantitative RT-PCR data were first normalized using GAPDH data and then were converted to gene expression fold changes to analyze using ANOVA. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted and adjusted using Tukey method. Statistical analyses were conducted using R V3.3.2 (R foundation, Vienna, Austria) and Rstudio V1.0 (Rstudio, PBC, Boston, MA). All statistical tests were two-sided and alpha was set to 0.05.

Results

BI-induced nociception changes with time

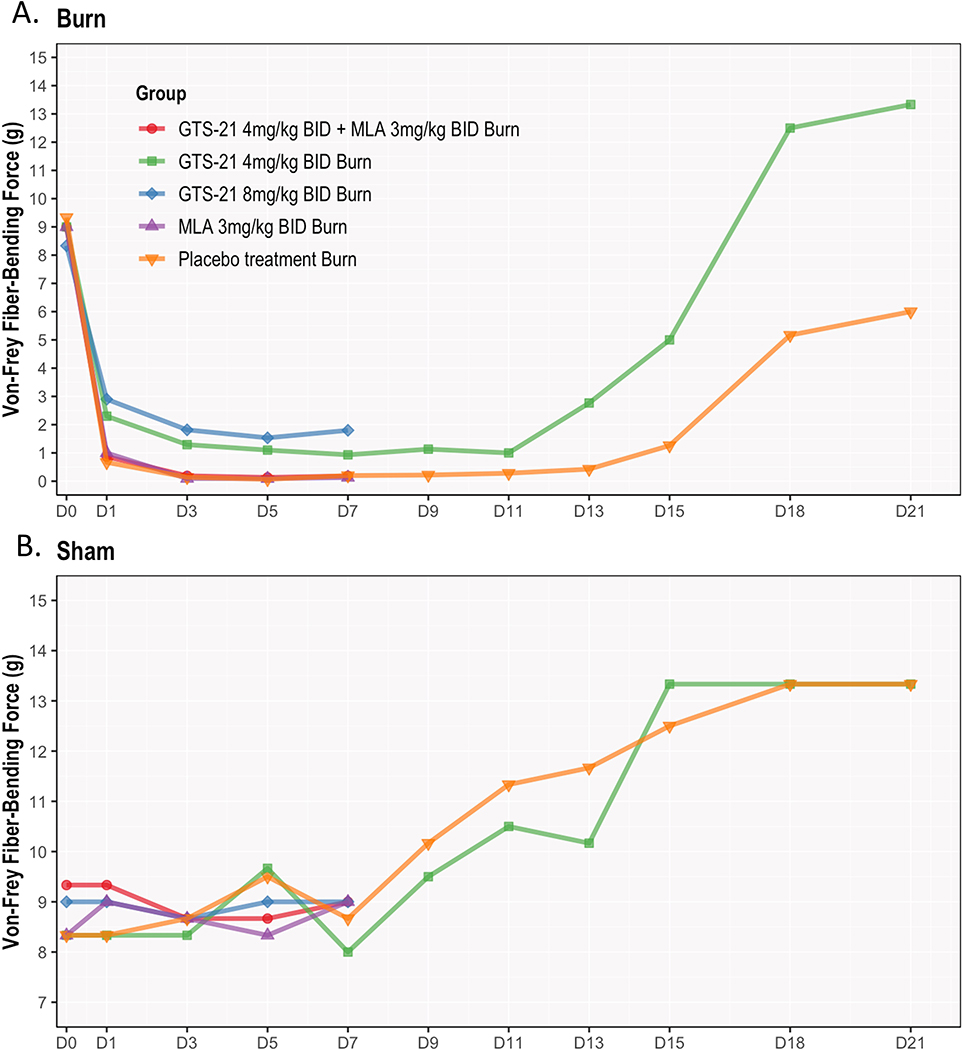

Natural development of BI-induced allodynia

On BI ipsilateral-side, the Von-Frey threshold decreased significantly for saline-treated group starting from day 1 after BI (p< 0.001). This lowest plateau lasted ~13–15 days and did not recover to baseline even at day 21 (Figure 2A). On the contralateral-side, the Von-Frey threshold steadily increased from day 1 onwards (Figure 2B). That is, BI to right-side did affect nociception on the distant left-side (p>0.999).

Figure 2. (A & B). GTS-21 attenuates post-burn mechanical allodynia in young rats.

Following burn injury (BI) to rats (n = 6 per group), mechanical threshold (allodynia) using Von-Frey filaments was tested on the ipsilateral (right) side of BI after the following 5 groups of treatments: (i) saline only, (ii) GTS-21(4 or 8 mg/kg), (iii) GTS-21 (4 mg/kg) with methyllycaconitine (MLA 3 mg/kg), an α7nAChR antagonist for 7 days only and (v) MLA alone 7 day. Allodynia was tested pre-burn (baseline), and then every other day from day 1–21 days post-burn. Ipsilateral responses were compared to baseline and contralateral (left) side of BI animals receiving saline (Control). Of note, study animals grew older as being treated from day 0 (at 3 weeks of age) to at day 21 after BI (6–7 weeks old rats).

Figure 2A describes the behavioral responses of mechanical allodynia from day 0–21 for all 5 study groups on the ipsilateral side. BI resulted in significant decrease in allodynia threshold as early as day 1 compared to baseline and remained at that lowest plateau for around 7 days and then started to recover, but the recovery did not reach baseline even at day 21 in the saline-treated animals. Allodynia responses between MLA, GTS-21 plus MLA and saline-treated BI group did not differ. GTS-21 at both 4 and 8 mg/kg doses significantly improved threshold compared with other three groups at days 1–7. No significant differences between these two doses were found.

Figure 2B depicts mechanical threshold-changes with time on the contralateral side with 5 regimens described the same as in figure 2A. No differences were observed between groups on the contralateral side throughout the 7 days. This figure demonstrates the mechanical threshold on the contralateral side of BI injured rats treated with all 5 groups did not differ, but steadily increased starting from day 9l. The mechanical thresholds at day 21 in both saline- and GTS-21-treated subjects were higher than that of baseline.

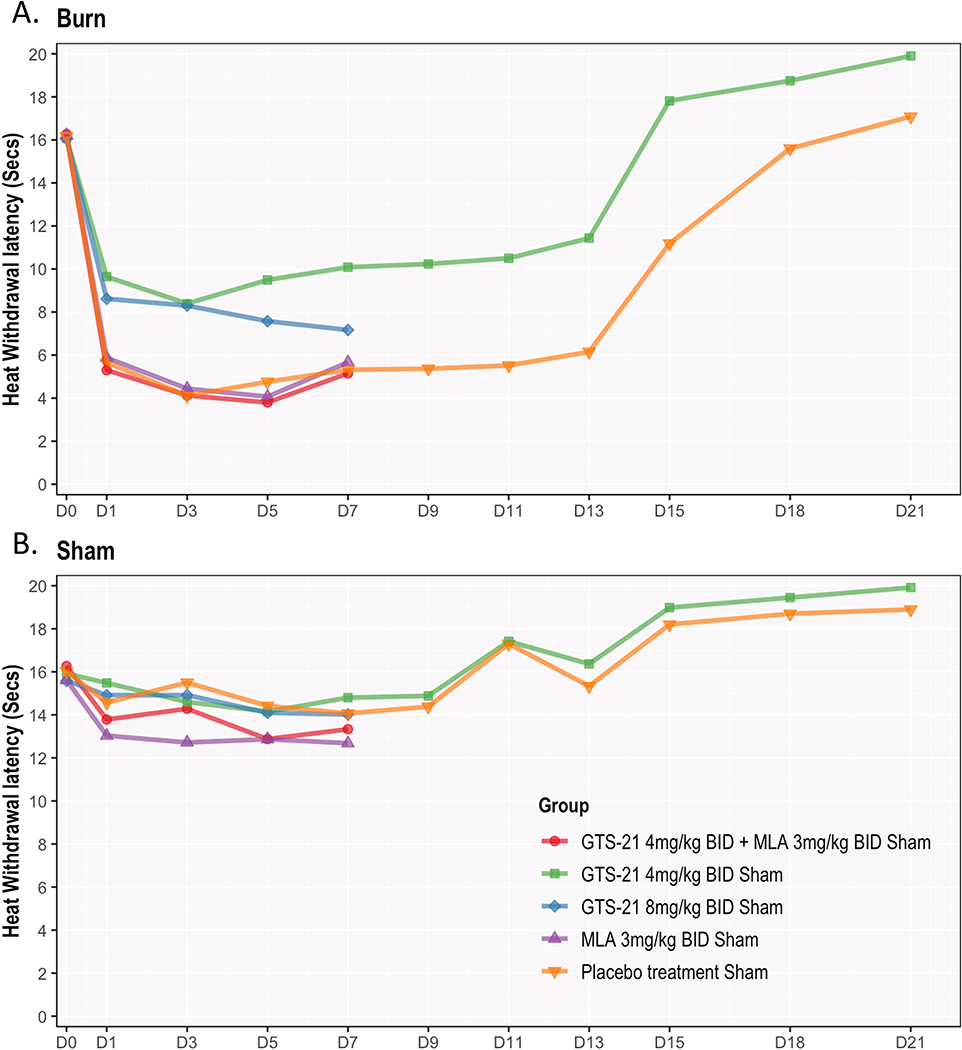

Natural development of BI-induced hyperalgesia.

BI caused a significant decrease in withdrawal-latencies to radiant heat on the ipsilateral-side starting from day 1 in saline-treated animals (p<0,001, Figure 3A). This peak effect (lowest plateau) lasted ~13–15 days and recovered to baseline by day 21. On contralateral-side, withdrawal-latencies remained steady till day 9 and then increased without a clear plateau (p=0.087, Figure 3B).

Figure 3. (A & B). GTS-21 attenuated post-burn heat hyperalgesia in young rats.

Figure 2A depicts the behavioral response of heat hyperalgesia after BI to radiant heat in all five treatment groups. BI rats had a significant onset of radiant heat hyperalgesia by day 1 compared to baseline. Their levels remained at that lowest plateau for around 12 days and then started to recover. Treatment of GTS-21 for 21 days reversed the hyperalgesia to baseline by day 15. In contrast, the saline-treated BI showed recovery much slower till at day 19.

Figure 3A showed that both doses of GTS-21 significantly increased the withdrawal latency to heat on the ipsilateral side. Withdrawal latencies in GTS-21 4 mg/kg group was slightly higher than those receiving 8 mg/kg, although not statistically significant. This preliminary result justified our choice to continue only 4 mg/kg for periods beyond day 7 for 14 days). The co-administration of α7AChR antagonist, MLA with GTS-21 reversed the beneficial effects of 4 mg/kg GTS-21 to level of BI rats receiving saline. MLA alone had no effect on the ipsilateral side.

Figure 3B depicts the contralateral side responses to hyperalgesia tests. No differences in hyperalgesia were observed between GTS-21 (4 or 8 mg/kg, and GTS-21 with MLA for 7 days. MLA alone for 7 days, interestingly, caused increased hyperalgesia on the contralateral side at days 4–7 but this effect was not statistically significant. An observation not expected in the study, was that, similar to allodynia, the hyperalgesia latency at day 21 (6–7 weeks old rats) of saline- and GTS-21-treated rats were higher than that at baseline (3 weeks old rats).

GTS-21 and/or MLA effects on BI-nociception (acute injury phase: day 1–7)

Treatment responses on allodynia.

The allodynia threshold after BI in both GTS-21 (4 and 8 mg/kg) groups significantly improved compared with other three non-GTS-21 groups (days 1–7). For instance, Von-Frey measures increased 2.23 units (95% CI=0.43–4.03, p=0.01) with 8 mg/kg GTS-21 and 1.63 units (95% CI= −0.17–3.43, p=0.089 after Tukey adjustments) with 4 mg/kg GTS-21 compared to saline group at day 1. Efficacy of the two doses did not differ (Figure 2A and Supplemental Figure S2A). Ipsilateral-side allodynia responses between GTS-21 + MLA-group, MLA alone and saline-treated BI group were not different. On the contralateral-side, Von-Frey testing showed no differences among GTS-21 (4 or 8 mg/kg), GTS-21 plus MLA, MLA and saline-treated BI groups (Likelihood ratio test p=0.976, Figure 2B and Supplemental Figure S2A).

Treatment responses on Hyperalgesia.

Similar to Von-Frey, both GTS-21-treated groups showed higher ipsilateral-side thermal withdrawal latencies compared to the three non-GTS-21 groups (Figure 3A and Supplemental Figure S3A). For instance, withdrawal latency measures increased 2.74 units (95% CI = 1.68–3.80, p < 0.001) with 8 mg/kg GTS-21and 3.98 units (95% CI = 2.93–5.04, p < 0.001 after Tukey adjustment) with 4 mg/kg GTS-21 compared to saline-treated BI group at day 1. Latency between GTS-21 plus MLA group, and saline-treated BI groups did not differ, indicating that MLA counteracted the beneficial GTS-21 effects on hyperalgesia. MLA had no effects on hyperalgesia. The contralateral-side hyperalgesia testing showed that MLA slightly decreased threshold compared to other groups from day 4–7.

Behavioral changes with GTS-21 4 mg/kg vs. saline-treatment at full trajectory, Day 1–21)

There were five treatment groups at day 1–7. Preliminary results showed that both doses of GTS-21 significantly attenuated nociception and had equipotent effects mitigating BI hyperalgesia versus saline-treatment. Therefore, studies beyond day 7 were made in two groups (4 mg/kg and saline-treated rats) and differences determined. (For details, see Figure 2 & 3 and Supplemental Tables S1A and S1B).

Treatment responses on Allodynia.

For ipsilateral-side from day 1–21, Von-Frey testing showed that thresholds with GTS-21 4 mg/kg were significantly higher than saline-treated rats (p < 0.001). The contralateral-side showed no differences between the groups (p = 0.585). Detailed mean predictions and their 95% CIs are presented in the Supplemental Tables S2A to S3B).

Treatment responses on Hyperalgesia.

Ipsilateral-side hyperalgesia from day 1–21 showed that withdrawal latency was consistently significantly improved with GTS-21 versus saline-treated rats (p < 0.001). The contralateral-side nociception did not differ between the two groups (p = 0.152). A finding (not part of planned study) was that both the allodynia and hyperalgesia behaviors at day 21 after BI (at 6–7 weeks of age) on the contralateral-side of both groups were slightly higher than that at baseline.

Spinal cord biomarker-changes

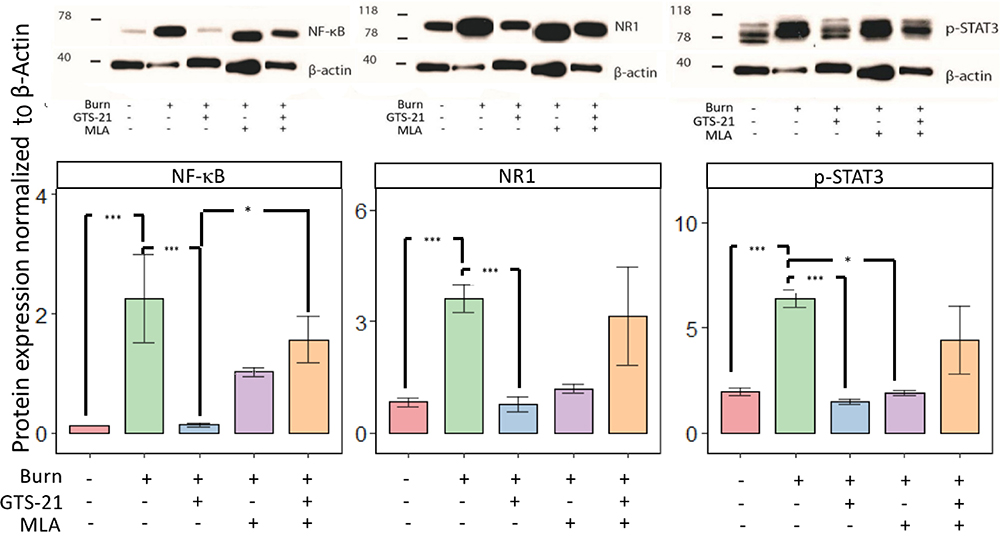

1. Western Blot.

Western Blots were performed on protein extracts to quantify NF-κB, NMDAR1, and pSTAT3 expression, normalized using β-actin levels as a covariate. ANOVA showed group-differences for expression of all three proteins (all p<0.001). When post-hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted, saline-treated BI animals had significantly increased expressions of the NF-κB, NMDAR1 and p-STAT3 (all p<0.001, Figure 4A). GTS-21 treatment significantly (all p<0.001) decreased the expression of these proteins to levels that are seen on the contralateral side that received saline. There were no differences in the values of NF-κB (p=0.108) and NR1 (p=1.000) but not for pSTAT3 (0.012) on ipsilateral side receiving saline and BI with MLA treatment. The combined administration of GTS-21 with MLA to BI injured animals significantly (p=0.020) counteracted the beneficial effects of GTS-21 on NF-kB expression but did not significantly counteract GTS-21 effects on NMDAR1 and p-STAT3 expression (p =1.000 and p=1.000). Thus: (i) BI increases the protein expression of NF-κB, NMDAR1, and p-STAT-3; (ii) GTS-21 attenuates the effect of BI on these biomarkers; (iii) MLA countered beneficial effects of GTS-21 on some (NF-κB) but not other biomarkers (NMDAR1, p-STAT3).

Figure 4. (A & B). GTS-21 abrogated increased spinal cord protein and transcriptional expression of pain biomarkers.

Fiugre 4 A. Protein expression of NF-κB, NDMA-NR1 subunit and phosphorylated STAT3 (p-STAT3) in the spinal cord dorsal horn of ipsilateral (right) side of burn injury (BI) was assessed by Western blots after 14 days of the following treatment regimen: (i) saline alone, (ii) GTS-21 alone, (iii) GTS-21 and methyllycaconitine (MLA), an α7AChR antagonist, and (iv) MLA alone (n=4 per group). The contralateral (left) side of BI saline-treated rats was used as Control (indicated in figure as Burn-). BI rats treated with saline had significantly upregulated expression of all three proteins on the ipsilateral side compared to Control. Administration of GTS-21 reversed the increased expression. Co-administration of MLA with GTS-21 significantly reversed GTS-21 effects on NF-kB but not on p-STAT3 or NR1 of NMDA. The protein expression of NF-kB and NMDAR1-NR1 on the ipsilateral side of BI receiving MLA alone did not differ from that ipsilateral side of BI receiving saline but not for p-STAT3 expression. Expression of the proteins is depicted after normalization of expression to β-actin. Data are mean and (SD). The *** indicates p< 0.001 and * indicates p<0.05.

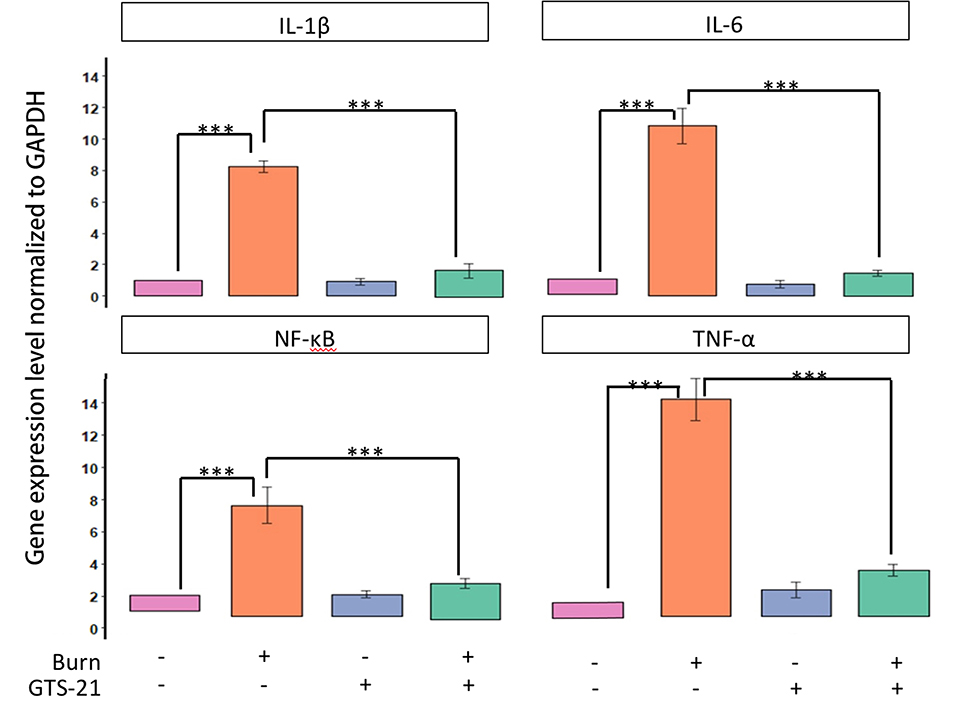

Figure 4B. After BI, spinal cord dorsal horn ipsilateral (right) and contralateral (left) sides were excised after saline or GTS-21 treatment for 14 days. The spinal segment was divided into dorsal and ventral sections and only dorsal sections were used for analyses. The contralateral side of BI rats treated with saline was used as Control (n=3 for each group). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed, as described in Methods, on the mRNA expression of inflammatory proteins, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α and NF-kB. Gene expression (qPCR) of all inflammatory markers, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α and NF-kB in the spinal cord dorsal horn ipsilateral to the BI was upregulated at 14 days after BI. Administration of GTS-21 reversed the upregulated expression to control levels. Data are presented as mean fold change (SD) in gene expression, relative to expression on the saline-treated contralateral side. The *** indicates p< 0.001.

2. Quantitative RT-PCR

The transcripts of IL-1β, IL-6, NF-κB and TNF-α were quantified after BI and treatment with saline or GTS-21. The ipsilateral- and contralateral-sides of both groups were used after dividing the dorsal spinal cord into right and left sides. Gene expressions, normalized to the contralateral-side of the saline-treated BI animals, were expressed as fold change. By ANOVA, between-group gene differences were observed for all expressions (p<0.05); IL-1β, IL-6, NF-κB and TNF-α expression significantly (p< 0.001) increased on BI side receiving saline versus saline-treated contralateral-side. No differences in expressions (all P >0.05) were observed on the saline- and GTS-1-treated contralateral-side. GTS-21 significantly decreased IL-1β, IL-6, NF-κB and TNF-α expression (p<0.001) on the ipsilateral-side to the level of saline-treated contralateral-side (Figure 4B).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

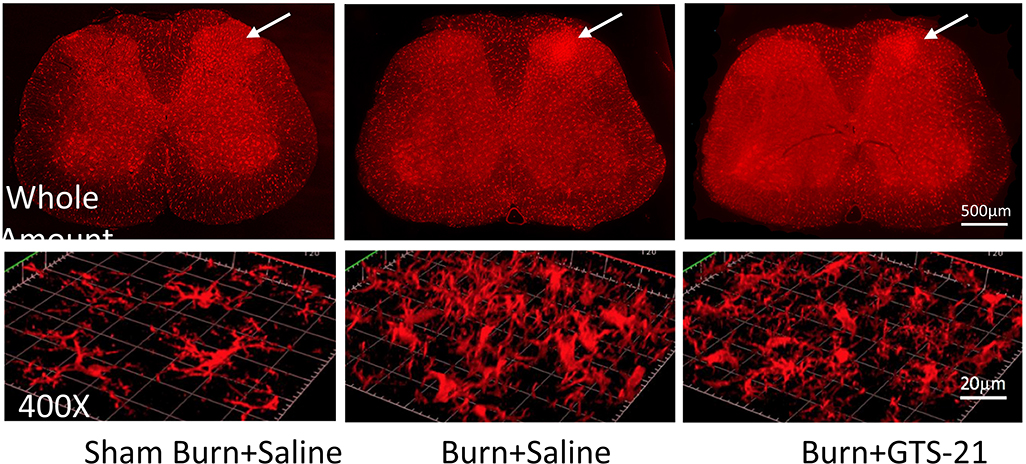

IHC studies were performed at day 7 after BI. The Iba1 immunoreactivities of ipsilateral-side of BI animals treated with saline or GTS-21 were compared. Representative fluorescent images of the spinal cord whole mount (25X) on the ipsilateral-side demonstrated microgliosis versus contralateral-side (figure 5, upper panel). The white arrow shows microgliosis or lack thereof on the dorsal-horn lamina 1–2 areas on contralateral- and BI-sidess. The confocal images in lower panel show the highly magnified images (400X) of the white-arrow area from upper panel of sham-burn and BI-rats with and without GTS-21. The BI-rats showed ~200% (n=3) increase of numbers compared to sham-BI. GTS-21 to the BI group reduced the numbers of microglia to ~120% (n=3).

Figure 5. Confocal images Immunohistochemistry (IHC) of spinal microglia dorsal horn after burn injury with and without GTS-21.

Rats received sham or burn injury and then received saline or GTS-21 (n=3 per group). Lumbar spinal cord (L4–5) segments were harvested at day 7. After preparation of tissues with paraformaldehyde and staining with Iba1, a specific marker for microglia, tissue slices were observed via confocal microscopy (Zeiss LSM 800) at 25X magnification (upper panel, whole picture mount of spinal cord) and at 400X magnification (lower panel). Optically-sectioned serial images captured as whole mount pictures of spinal cord were processed by ZEN 2.3 system. The white arrow area indicated in the upper panel was magnified to 400X and processed for 3D contour by ZEN 2.3 system. The IHC staining of microglia on the ipsilateral side dorsal horn (indicated) by white arrow on upper panel) were compared between groups in the 400-fold magnified confocal images (lower panel). As compared to sham-burn injury, the burn-injured rats showed ~200-fold increase of microglia activity (p<.05). Treatment of burn-injured mice with GTS-21 reduced the microglia activity to ~120% in the burn-injured (BI +G) group compared to BI saline-treatment group (p<0.05). White bar in upper panel = 500 μm. White bar on the lower (400X) panel = 20 μm.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that (i) BI to young rats caused ipsilateral-side hyperalgesia and allodynia; (ii) GTS-21 (4 or 8 mg/kg) treatment for 7 days attenuated the exaggerated nociception by day one; the effectiveness of both doses did not differ; (iii) The continued administration of GTS-21 for 14 days mitigated BI pain behaviors and caused recovery to baseline sooner. Saline-treated BI rats had longer recovery of hyperalgesia; the allodynia did not recover by day 21; (iv) co-administration of MLA with GTS-21 reversed the beneficial effects of GTS-21 on nociception; (v) BI increased spinal inflammatory cytokine expression (TNF-α, IL-1β and NF-kB) and neuropathy pain-biomarkers (IL-6, NMDAR, and p-STAT-3); (vi) BI-induced microgliosis was observed at day 7 (vii) GTS-21 normalized the increased protein and transcriptional expression of pain-biomarkers. These findings indicate that BI pain has both inflammatory and neuropathic components and GTS-21 attenuates exaggerated nociceptive behaviors, at least in part, by inhibiting pain-inducing biomarkers expression.

As in our previous studies, 20,28,29 BI on the dorsum induced nociceptive behaviors on the ventral (plantar) aspect of the paw. The current study documents that exaggerated nociception even after a small burn can last beyond day 14 and sometimes persisting to day 21 in saline-treated animals. In a previous study by us, although microgliosis in the dorsal horn of the ipsilateral side of BI was observed, the relationship of biomarker changes to nociception was not evaluated.20 The current study confirms that BI results in activation of microglia evidenced the increased expression of spinal pain-biomarkers, a phenomenon observed by others also in BI models 14,15, and in other states of exaggerated pain behaviors.11,12

The BI-related release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPS) possibly causes CNS inflammasome activation, microglia activation, inflammatory cytokine release and neuroinflammatory priming. 19,32,33 Consistently, there is indeed evidence for neuro-inflammation following body BI to humans.34 DAMPS- and Inflammasome-mediated activated microglia are of the inflammatory MI-phenotype capable of releasing inflammatory cytokines and sensitizing sensory neurons that lead to the injury-induced exaggerated pain perception. 19,30 Microglia constitutively express α7AChRs. 2,6,22,27 Previously, we have demonstrated the specificity of GTS-21 by using small inhibitory RNA (SiRNA) to prevent the expression of α7NachRs in leucocytes; the anti-inflammatory properties of GTS-21 were abrogated when the α7nAChRs expression was prevented by the SiRNA. 22 In the current study, the in vivo specificity of GTS-21 was tested by the co-administration of MLA, an α7AChRs blocker. When MLA was co-administered, the beneficial effects of GTS-21 were abrogated both on nociception and on spinal pain biomarker expression. Although, BI of this magnitude did not seem to affect pain behaviors on the contralateral (distant) side in our study, there is evidence for major body burn to cause increased nociception at sites distant from burn, at later times than studied by us. 15,35

Saline-treated BI animals had increased mRNA expression of inflammatory markers (TNF-α, IL-1β, and NF-κB) in the ipsilateral dorsal segment, in concert with NF-kB protein expression. NF-kB is a key transcription factor that controls the expression of pain mediators.19,36 GTS-21 treatment of BI animals reversed all inflammatory markers and was also associated with normalization of the exaggerated nociceptive behaviors earlier than saline-treated BI animals. This normalization of spinal cord biomarkers at day 14 seem to be associated with the steeper trajectory for recovery at day 13–15 with GTS-21 compared to saline treatment. There is indeed a lag-period (hysteresis) between changes in spinal cord and pain responses. This is consistent with the onset of pain as early as day 1 with minimal microglia changes and onset of significant microglia changes at a later period. Immunohistochemistry data confirmed that GTS-21 treatment decreases BI-induced microgliosis (Figure 5). The modest decrease in microgliosis with GTS-21 is consistent with the modest change in nociceptive behavior at day 7.

Activation and up-regulation of NMDAR has also been implicated in neuropathic pain conditions. Our previous studies have provided evidence for upregulation of NMDAR following paw BI. In this study, protein expression of NR1 subunit of NMDAR was upregulated on the ipsilateral side of BI. Inflammation also possibly upregulates NR1 expression. The increased IL-6 expression after BI reflects the neuropathic component of BI pain. 17,18 The downstream effector of IL-6 is signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), a member of the Janus kinase (JAK)/STAT signaling. A recent study demonstrated the important role of activation of STAT3 in chronic surgical (neuropathic) pain. 37 Other studies have shown that nerve injury is associated with increased p-STAT3 and pain: inhibition or genetic knock out of the IL-6-STAT3 attenuated mechanically induced allodynia. 37–39 The normalization of IL-6 and STAT-3 with GTS-21 is consistent with another study of the utility of GTS-21 to modulate IL-6 and STAT-3 pathway. 23,37 Therefore, GTS-21 treatment reversal of the upregulated NMDAR, IL-6 and STAT-3 levels probably contributed to the improvement of the neuropathic component of exaggerated BI.

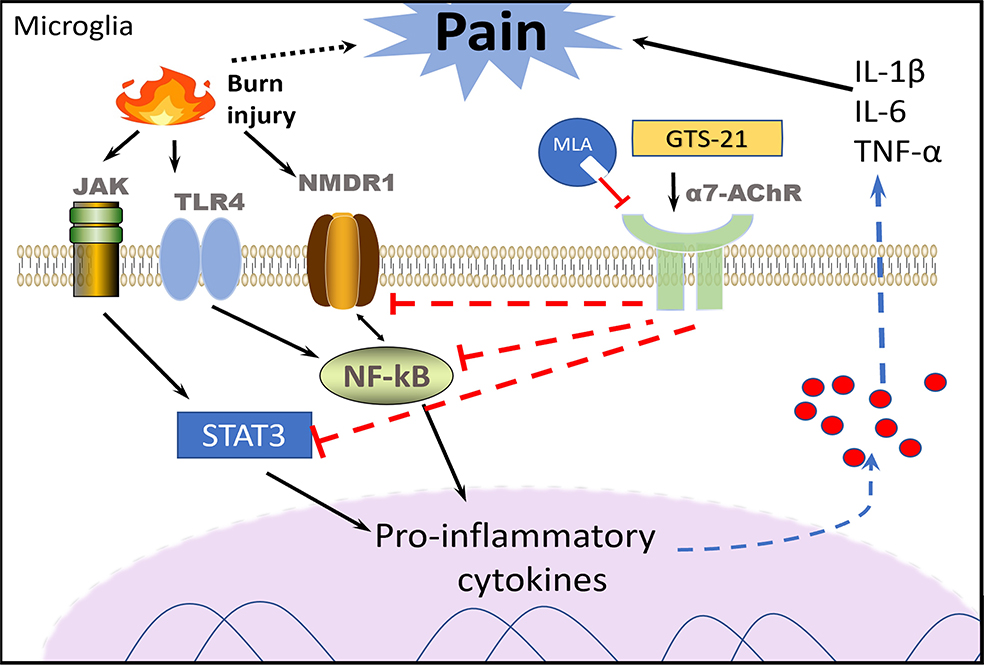

Figure 6 provides a summary of the interactions between BI, pain-biomarkers, microglia, GTS-21 and α7AChRs to modulate BI pain. Our results indicate that non-opioid, α7AChR agonist, GTS-21 elicits anti-nociceptive effects and improves BI pain at least in part by normalization of pain biomarkers and possibly effects on microglia. Several α7AChR agonists are undergoing clinical trials to rectify different pathologic states (NCT01716975, NCT01003379, NCT00687141). These clinical trials are very encouraging and provides an impetus to validate our observations using these clinical-trial drugs in humans since our studies demonstrate that α7AChR agonists as potential therapeutic adjunct to decrease BI pain.

Figure 6. Proposed mechanisms of GTS-21-responsive, α7AChR-mediated alleviation of burn-induced mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia (nociceptive behaviors).

Burn injury induces spinal cord microgliosis microglia activation evidenced by the upregulation of inflammatory and pain biomarkers. Activated microglia respond to the injury by releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-1β, TNF-α and NF-κB. Neuropathic pain biomarkers, NMDR1, IL-6 and p-STAT-3 were also increased. These biomarker upregulation can sensitize the sensory neurons resulting lower threshold for pain, detected as mechanical allodynia to Von-Frey filaments and thermal hyperalgesia to radiant heat testing (development of burn injury exaggerated nociceptive behaviors).Stimulation of microglia that constitutively express α7AChRs with selective agonist, GTS-21, alleviates burn injury pain via inhibition of the afformentioned biomarker expression. Selective α7AChR anagonist, MLA, reverses the beneficial effects of GTS-21 including mitigation of burn injury pain.

Abbreviations: Interleukin-1β (IL1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), N-methyl D-aspartate receptor N1 subunit (NMDAR1), janus activated kinase phosphorylated-STAT-3 (p-STAT-3). Nicotinic α7 acetylcholine receptors (α7AChRs). Methyllycaconitine (MLA) a specific antagonist of α7AChRs reversing effects of GTS-21.

Supplementary Material

Key Points:

Question: What is molecular mechanism of burn injury-induced pain?

Findings: Burn injury-induced exaggerated nociceptive behaviors are associated with microgliosis and increased expression of pain biomarkers in spinal cord and these changes are mitigated by the administration of α7AChR agonist, GTS-21.

Meaning: Non-opioid, GTS-21 holds promise as potential therapeutic adjunct to decrease BI pain by attenuating both microglia changes and expression of exaggerated pain transducers.

Acknowledgments

Funding The work was partially supported by grants from NIH RO1 GM118947 and from Shriners Hospitals Philanthropy (to JAJM), NIH RO1 GM128692 (to SS) and NIH RO1 DA 36564 (to JM).

Dr. Zhou performed this work during her Research Fellowship in Boston, MA, and was the recipient of Resident Research Contest Award (Basic Science) given at the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Anesthesiology, October 2018. Dr. Yiuka Leung-Pitt importantly contributed to the work as part of her Clinical Anesthesia Research Rotation in Year 3.

Glossary of Abbreviations:

- α7AChR

alpha 7 acetylcholine receptor

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- CNS

central nervous system

- Iba1

ionized calcium-binding adaptor protein

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GCM

growth curve modeling

- IL-1β

interleukin-1β

- IL-6

Interleukin-6

- JAK-STAT3

Janus associated kinase signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

- MLA

methyllcaconitine

- NF-kB

nuclear factor-k beta

- NMDAR

N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- qRT-PCR

quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- TNF- α

tumor necrosis factor-α

References

- 1.Greenhalgh DG. Management of Burns. The New England journal of medicine. 2019;380(24):2349–2359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stoddard FJ, Sheridan RL, Saxe GN, et al. Treatment of pain in acutely burned children. The Journal of burn care & rehabilitation. 2002;23(2):135–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fagin A, Palmieri TL. Considerations for pediatric burn sedation and analgesia. Burns Trauma. 2017;5:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hannibal KE, Bishop MD. Chronic stress, cortisol dysfunction, and pain: a psychoneuroendocrine rationale for stress management in pain rehabilitation. Phys Ther. 2014;94(12):1816–1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McWilliams LA, Cox BJ, Enns MW. Mood and anxiety disorders associated with chronic pain: an examination in a nationally representative sample. Pain. 2003;106(1–2):127–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holbrook TL, Galarneau MR, Dye JL, Quinn K, Dougherty AL. Morphine use after combat injury in Iraq and post-traumatic stress disorder. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;362(2):110–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang X, Orton M, Feng R, et al. Chronic Opioid Usage in Surgical Patients in a Large Academic Center. Ann Surg. 2017;265(4):722–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Puntillo KA, Naidu R. Chronic pain disorders after critical illness and ICU-acquired opioid dependence: two clinical conundra. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2016;22(5):506–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chacur M, Milligan ED, Gazda LS, et al. A new model of sciatic inflammatory neuritis (SIN): induction of unilateral and bilateral mechanical allodynia following acute unilateral peri-sciatic immune activation in rats. Pain. 2001;94(3):231–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lyness WH, Smith FL, Heavner JE, Iacono CU, Garvin RD. Morphine self-administration in the rat during adjuvant-induced arthritis. Life sciences. 1989;45(23):2217–2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tran M, Kuhn JA, Braz JM, Basbaum AI. Neuronal aromatase expression in pain processing regions of the medullary and spinal cord dorsal horn. J Comp Neurol. 2017;525(16):3414–3428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basbaum AI, Bautista DM, Scherrer G, Julius D. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of pain. Cell. 2009;139(2):267–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bittner EA, Shank E, Woodson L, Martyn JA. Acute and perioperative care of the burn-injured patient. Anesthesiology. 2015;122(2):448–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang YW, Waxman SG. Minocycline attenuates mechanical allodynia and central sensitization following peripheral second-degree burn injury. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2010;11(11):1146–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang YW, Tan A, Saab C, Waxman S. Unilateral focal burn injury is followed by long-lasting bilateral allodynia and neuronal hyperexcitability in spinal cord dorsal horn. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2010;11(2):119–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finnerty CC, Przkora R, Herndon DN, Jeschke MG. Cytokine expression profile over time in burned mice. Cytokine. 2009;45(1):20–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsuda M, Kohro Y, Yano T, et al. JAK-STAT3 pathway regulates spinal astrocyte proliferation and neuropathic pain maintenance in rats. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 4):1127–1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou YQ, Liu Z, Liu ZH, et al. Interleukin-6: an emerging regulator of pathological pain. Journal of neuroinflammation. 2016;13(1):141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martyn JAJ, Mao J, Bittner EA. Opioid Tolerance in Critical Illness. The New England journal of medicine. 2019;380(4):365–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ueda M, Iwasaki H, Wang S, et al. Cannabinoid receptor type 1 antagonist, AM251, attenuates mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia after burn injury. Anesthesiology. 2014;121(6):1311–1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee S, Yang HS, Sasakawa T, et al. Immobilization with atrophy induces de novo expression of neuronal nicotinic alpha7 acetylcholine receptors in muscle contributing to neurotransmission. Anesthesiology. 2014;120(1):76–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khan MA, Farkhondeh M, Crombie J, Jacobson L, Kaneki M, Martyn JA. Lipopolysaccharide upregulates alpha7 acetylcholine receptors: stimulation with GTS-21 mitigates growth arrest of macrophages and improves survival in burned mice. Shock (Augusta, Ga). 2012;38(2):213–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bagdas D, Targowska-Duda KM, Lopez JJ, Perez EG, Arias HR, Damaj MI. The Antinociceptive and Antiinflammatory Properties of 3-furan-2-yl-N-p-tolyl-acrylamide, a Positive Allosteric Modulator of alpha7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors in Mice. Anesth Analg. 2015;121(5):1369–1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schaller SJ, Nagashima M, Schonfelder M, et al. GTS-21 attenuates loss of body mass, muscle mass, and function in rats having systemic inflammation with and without disuse atrophy. Pflugers Arch. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kem WR, Mahnir VM, Prokai L, et al. Hydroxy metabolites of the Alzheimer’s drug candidate 3-[(2,4-dimethoxy)benzylidene]-anabaseine dihydrochloride (GTS-21): their molecular properties, interactions with brain nicotinic receptors, and brain penetration. Molecular pharmacology. 2004;65(1):56–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kashiwagi S, Khan MA, Yasuhara S, et al. Prevention of Burn-Induced Inflammatory Responses and Muscle Wasting by GTS-21, a Specific Agonist for alpha7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. Shock. 2017;47(1):61–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Simone R, Ajmone-Cat MA, Carnevale D, Minghetti L. Activation of alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor by nicotine selectively up-regulates cyclooxygenase-2 and prostaglandin E2 in rat microglial cultures. J Neuroinflammation. 2005;2(1):4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang S, Zhang L, Ma Y, et al. Nociceptive behavior following hindpaw burn injury in young rats: response to systemic morphine. Pain Med. 2011;12(1):87–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang S, Lim G, Yang L, et al. A rat model of unilateral hindpaw burn injury: slowly developing rightwards shift of the morphine dose-response curve. Pain. 2005;116(1–2):87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li K, Tan YH, Light AR, Fu KY. Different peripheral tissue injury induces differential phenotypic changes of spinal activated microglia. Clin Dev Immunol. 2013;2013:901420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song L, Wang S, Zuo Y, Chen L, Martyn JA, Mao J. Midazolam exacerbates morphine tolerance and morphine-induced hyperactive behaviors in young rats with burn injury. Brain Res. 2014;1564:52–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson BJ, Mikkelsen ME. Stressing the Brain: The Immune System, Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis, and Psychiatric Symptoms in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Survivors. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(6):839–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fonken LK, Weber MD, Daut RA, et al. Stress-induced neuroinflammatory priming is time of day dependent. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;66:82–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gatson JW, Liu MM, Rivera-Chavez FA, Minei JP, Wolf SE. Serum Levels of Neurofilament-H are Elevated in Patients Suffering From Severe Burns. J Burn Care Res. 2015;36(5):545–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ueda M, Hirose M, Takei N, et al. Nerve growth factor induces systemic hyperalgesia after thoracic burn injury in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 2002;328(2):97–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rossaint J, Zarbock A. Perioperative Inflammation and Its Modulation by Anesthetics. Anesth Analg. 2018;126(3):1058–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shen Y, Li D, Li B, et al. Up-Regulation of CX3CL1 via STAT3 Contributes to SMIR-Induced Chronic Postsurgical Pain. Neurochem Res. 2018;43(3):556–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klein MA, Moller JC, Jones LL, Bluethmann H, Kreutzberg GW, Raivich G. Impaired neuroglial activation in interleukin-6 deficient mice. Glia. 1997;19(3):227–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramer MS, Murphy PG, Richardson PM, Bisby MA. Spinal nerve lesion-induced mechanoallodynia and adrenergic sprouting in sensory ganglia are attenuated in interleukin-6 knockout mice. Pain. 1998;78(2):115–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.