Abstract

Background

After the 2002/2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak, 30% of survivors exhibited persisting structural pulmonary abnormalities. The long-term pulmonary sequelae of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) are yet unknown, and comprehensive clinical follow-up data are lacking.

Methods

In this prospective, multicentre, observational study, we systematically evaluated the cardiopulmonary damage in subjects recovering from COVID-19 at 60 and 100 days after confirmed diagnosis. We conducted a detailed questionnaire, clinical examination, laboratory testing, lung function analysis, echocardiography and thoracic low-dose computed tomography (CT).

Results

Data from 145 COVID-19 patients were evaluated, and 41% of all subjects exhibited persistent symptoms 100 days after COVID-19 onset, with dyspnoea being most frequent (36%). Accordingly, patients still displayed an impaired lung function, with a reduced diffusing capacity in 21% of the cohort being the most prominent finding. Cardiac impairment, including a reduced left ventricular function or signs of pulmonary hypertension, was only present in a minority of subjects. CT scans unveiled persisting lung pathologies in 63% of patients, mainly consisting of bilateral ground-glass opacities and/or reticulation in the lower lung lobes, without radiological signs of pulmonary fibrosis. Sequential follow-up evaluations at 60 and 100 days after COVID-19 onset demonstrated a vast improvement of symptoms and CT abnormalities over time.

Conclusion

A relevant percentage of post-COVID-19 patients presented with persisting symptoms and lung function impairment along with radiological pulmonary abnormalities >100 days after the diagnosis of COVID-19. However, our results indicate a significant improvement in symptoms and cardiopulmonary status over time.

Short abstract

100 days after COVID-19 onset, a high portion of patients exhibit persisting symptoms and cardiopulmonary impairment. Still, a marked improvement of symptoms, pulmonary function and CT pathologies was found at follow-up. https://bit.ly/35YP13g

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) shares clinical and mechanistic characteristics with the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak of 2002/2003, including angiotensin-converting enzyme-2-dependent cellular entry and interleukin (IL)-6-driven hyperinflammation, potentially leading to imbalanced immune responses and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [1–13]. In different studies evaluating SARS survivors months after infection, fibrotic features, including abnormal scoring of airspace opacity and reticular shadowing, were observed in up to 36% of the patients [2, 14, 15]. A 1-year follow-up study on 97 recovering SARS patients in Hong Kong showed that 27.8% of survivors presented with decreased lung function and signs of pulmonary fibrosis compared to a normal population, which was confirmed by another follow-up study [2, 14, 16]. Moreover, the phylogenetically related Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus (CoV) was shown to induce pulmonary fibrosis in up to 33% of patients [17]. As SARS-CoV-2 shares high homology with SARS-CoV-1, and to a lesser extent with MERS-CoV, it is thus conceivable that survivors of COVID-19 may also develop pulmonary fibrosis [7]. With worldwide >74 million confirmed cases at the time of writing, and an average 20% of patients with a moderate-to-severe course of infection often needing hospitalisation, the development of fibrosing lung disease after clearance of infection could become an enormous health concern [1].

We thus designed a prospective, multicentre, observational study, the Development of Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD) in Patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection (CovILD) study, aimed at systematically evaluating the persisting cardiopulmonary damage of COVID-19 patients 60 days and 100 days after COVID-19 onset.

Methods

Study design

Enrolment of the CovILD study began on April 29, 2020 (supplementary figure S1). The trial site is located at the Department of Internal Medicine II, Medical University of Innsbruck (Innsbruck, Austria), with two additional participating medical centres in Zams and Münster (Austria), which are tertiary care centres (Innsbruck, Zams) and an acute rehabilitation facility (Münster) all located in Tyrol, the first major COVID-19 hotspot in Austria. Diagnosis of COVID-19 was confirmed if a typical clinical presentation (according to current World Health Organization guidelines) along with a positive reverse transcriptase PCR SARS-CoV-2 test obtained from a nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal swab were present [18]. Eligibility included the necessity of hospitalisation (either on a normal ward or intensive care unit (ICU)) or outpatient care with persisting symptoms. A total of 190 patients were screened for study participation and 145 individuals were included in the final study. Reasons for nonparticipation were mainly logistic (e.g. tourists who left the country, and individuals who lived too far away from the study centre in Innsbruck to attend regular follow-up; n=27) or rejection of study participation (n=18).

We present a follow-up evaluation performed 60 days (mean±sd 63±23 days; visit 1) and 100 days (103±21 days; visit 2) after diagnosis of COVID-19. Of note, in Tyrol the healthcare system was never overloaded at the local peak of the pandemic, thus, all patients received supportive care according to the standard of care at the trial site hospitals and no selection bias due to triage methods was apparent. The trial protocol was approved by the institutional review board at Innsbruck Medical University (EK Nr: 1103/2020) and was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (registration number NCT04416100). Informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Procedures

During the follow-up visits, the following examinations were performed: clinical examination; medical history; a questionnaire about typical COVID-19 symptoms including cardiorespiratory, gastrointestinal and neurological symptoms during the disease and at follow-up, the modified British Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnoea score, a standardised performance status score, lung function testing including spirometry, body plethysmography and diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) adjusted for haemoglobin, capillary blood gas analysis, transthoracic echocardiography, standard laboratory examinations and a low-dose computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest.

All serological markers were determined on fully automated random access instruments: C-reactive protein (CRP), IL-6, procalcitonin (PCT), N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and serum ferritin were determined on a Roche Cobas 8000 analyser (Basel, Switzerland) and D-dimer on a Siemens BCS-XP instrument using the Siemens D-Dimer Innovance reagent (Erlangen, Germany).

CT scans were acquired without ECG gating on a 1280slice multidetector CT with a 128×0.6 mm collimation and spiral pitch factor of 1.1 (SOMATOM Definition Flash, Siemens Healthineers). Scans were obtained in the craniocaudal direction without iodine contrast agent and in a low-dose setting (100 kVp tube potential). If patients had a clinical suspicion for pulmonary embolism (PE), additional contrast CTs were conducted. Axial reconstructions were performed with a slice thickness of 1 mm. CT images were evaluated for the presence of ground-glass opacities (GGOs), consolidations, bronchiectasis and reticulations as defined by the glossary of terms of the Fleischner Society [19]. When present, the distribution of the findings was graded according to their distribution (unilateral/bilateral, involved lobes). Overall, pulmonary findings were graded for every lobe using the following CT severity score: 0: none; 1: minimal (subtle GGOs); 2: mild (several GGOs, subtle reticulation); 3: moderate (multiple GGOs, reticulation, small consolidation); 4: severe (extensive GGOs, consolidation, reticulation with distortion); and 5: massive (massive findings, parenchymal destructions). The maximum score was 25 (i.e. maximum score 5 per lobe). This score was used because the British Society of Thoracic Imaging (BSTI) definition of COVID-19 classifies only the extent of abnormality (<25%, 26–50%, 51–75%, >75%), and the BSTI post-COVID-19 CT report codes do not discriminate between “improving” (PCVCT1: no significant fibrosis or concerning features) and “fibrosis” (PCVCT3: fibrosis±inflammatory change present (inflammation>fibrosis/fibrosis>inflammation/fibrosis without inflammation)). In addition, we did not have a pre-COVID-19 baseline and an acute phase COVID-19 CT scan in most patients.

The Syngo.via CT Pneumonia Analysis (Siemens Healthineers) research prototype for the detection and quantification of abnormalities consistent with pneumonia was used to calculate the percentage of opacity and percentage of high opacity, indicating percentages of GGOs and consolidation, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using statistical analysis software package (IBM SPSS Statistics version 24.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). According to descriptive statistical analysis including tests for homoscedasticity and data distribution (Levene test, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, Shapiro–Wilk test and density blot/histogram analysis) two-sided parametric or nonparametric tests were applied as appropriate. For group comparisons of continuous data, the Mann–Whitney U-test, Kruskal–Wallis or Wilcoxon signed-rank test were applied. Binary and categorical data were analysed with Fisher's exact test, Chi-squared test or McNemar test. Multiple testing was adjusted by the Sidak formula. Correlations were assessed with Spearman rank (nonparametric data) or Pearson's (parametric data) test. To identify demographic and clinical factors impacting on the persistence of symptoms and radiological lung findings at follow-up, a series of fixed-effect ordinary and generalised linear models were created using R programming suite version 3.6.3 (www.r-project.org). Details of the statistical analysis and the software packages used are reported in the supplementary methods. Independently of the testing technique, effects were termed significant for p<0.05.

Results

Characteristics of the cohort

In total, 145 patients with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 participated in the CovILD study, and 133 subjects were also available for the second follow-up. The mean±sd time from the diagnosis of COVID-19, as defined by positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR testing, to follow-up was 63±23 days for visit 1 and 103±21 days for visit 2. The study cohort consisted of 55% male individuals, aged 19–87 years (table 1). 61% of COVID-19 patients were overweight or obese (body mass index >25 kg·m−2 or >30 kg·m−2, respectively). Most individuals had pre-existing comorbidities (77%) with cardiovascular and metabolic diseases being the most frequent (table 1). The majority of study participants (75%) were hospitalised during the acute phase of COVID-19, half of the hospitalised patients required oxygen supply, and 22% of all subjects were admitted to the ICU due to the necessity of noninvasive or invasive mechanical ventilation as determined by the treating physicians. Patients who were admitted to the ICU had more comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease, arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolaemia, chronic kidney disease or immune deficiency as compared to subjects without the necessity of ICU treatment (supplementary table S1). Additionally, higher age and male sex were related to a more severe course of acute COVID-19.

TABLE 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of patients enrolled in the Development of Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD) in Patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection (CovILD) study

| Subjects | 145 |

| Age years | 57±14 |

| Female | 63 (43) |

| BMI kg·m−2 | 26±5 |

| Smoking history | 57 (39) |

| Current smokers | 4 (3) |

| Pack-years | 8±16 |

| Comorbidities | |

| None | 33 (23) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 58 (40) |

| Hypertension | 44 (30) |

| Pulmonary disease | 27 (19) |

| COPD | 8 (6) |

| Asthma | 10 (7) |

| ILD# | 1 (1) |

| Metabolic disease | 63 (43) |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 27 (19) |

| Diabetes mellitus, type 2 | 24 (17) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 10 (7) |

| Chronic liver disease | 8 (6) |

| Malignancy | 17 (12) |

| Immunodeficiency¶ | 9 (6) |

| Hospitalised | 109 (75) |

| In-hospital treatment+ | |

| Oxygen supply | 72 (66) |

| Noninvasive ventilation | 3 (3) |

| Invasive ventilation | 29 (27) |

Data are presented as n, mean±sd or n (%). BMI: body mass index. #: n=1 with a history of radiation-induced pneumonitis; ¶: due to disease or ongoing immunosuppressive treatment: renal transplantation (n=1), psoriasis vulgaris (n=1), morbus Hashimoto (n=1), leukaemia (n=1), lymphoma (n=1), gout (n=1), polyarthritis (n=1). +: all patients needing noninvasive or invasive ventilation were supplied with oxygen before intensive care unit admission; relative numbers depict the treatment of in-hospital patients.

Clinical evaluation at follow-up

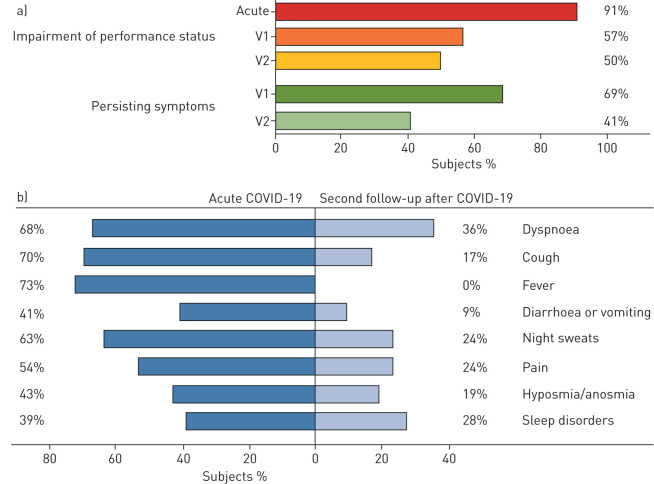

At the second follow-up visit, a relevant number of patients still reported an impaired performance status and persisting symptoms including dyspnoea (36%), night sweats (24%), sleep disorders (22%) or hyposmia/anosmia (19%), but with decreasing frequency compared to the acute phase of COVID-19 and the first follow-up visit (figure 1). Notably, severe symptoms, such as a severely impaired performance status (as assessed by a standardised questionnaire) or severe dyspnoea (mMRC score 3–4) were only found in 2% and 4%, respectively, of all study participants at second follow-up. Overall, a marked and continuous improvement of all assessed symptoms (namely impairment of performance status, dyspnoea, cough, fever, diarrhoea or vomiting, night sweats, hyposmia/anosmia and sleep disorders) from disease onset to follow-up at visits 1 and 2 was observed (figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Symptom burden in the Development of Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD) in Patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection (CovILD) study cohort during acute coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and at follow-up. a) Using a standardised questionnaire, performance status and overall burden of symptoms were assessed for the time-point of disease onset, 60 days (V1), and 100 days (V2) after diagnosis of COVID-19. b) Symptom burden was assessed using a standardised questionnaire at COVID-19 onset and at 100 days post-COVID-19 diagnosis. All symptoms significantly improved over time (p<0.001 for all read-outs). nacute=145, nfollow-up=135.

Cardiopulmonary evaluation at follow-up

At follow-up visit 1 and visit 2, trans-thoracic echocardiography unveiled a high rate of diastolic dysfunction (60% and 55% of all subjects, respectively). Signs of pulmonary hypertension as well as a pericardial effusion were detected only in a smaller portion of the cohort (supplementary table S2). Only four participants presented with a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). Whereas the frequency of diastolic dysfunction, signs of pulmonary hypertension and LVEF impairment did not significantly change from follow-up visit 1 to visit 2, the number of patients with pericardial effusion diminished over time (p=0.039).

An impaired lung function, reflected by reduced static and/or dynamic lung volumes, or impaired DLCO, was present in 42% and 36% of individuals at visit 1 and visit 2, respectively (table 2). In detail, 100 days after diagnosis of COVID-19, a reduction in forced vital capacity (FVC) and/or forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) was found in 22%, a reduced TLC in 11% and an impaired DLCO in 21% of all individuals. Additionally, hypoxia, as reflected by a reduced oxygen tension (PO2) assessed with capillary blood gas analysis (PO2 <75 mmHg), was still present in 37% of all subjects, and these patients demonstrated mild (80%, PO2 <75–65 mmHg) or moderate (20%, PO2 <65–55 mmHg) hypoxia at rest. Notably, dynamic lung volumes and DLCO significantly increased over time. As compared to follow-up visit 1 there was a moderate but significant improvement of most of these parameters over time (table 2).

TABLE 2.

Pulmonary function of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients at follow-up

| First follow-up# | Second follow-up¶ | p-value time change | |

| Subjects | 126 | 133 | |

| Lung function impaired+ | 53 (42) | 48 (36) | 0.388 |

| FVC L | 3.6±1.0 | 3.7±0.9 | <0.001 |

| FVC <80% predicted | 34 (27) | 29 (22) | 0.049 |

| FEV1 L | 2.9±0.8 | 3.0±0.8 | 0.001 |

| FEV1 <80% predicted | 28 (22) | 30 (22) | 1.000 |

| FEV1/FVC % | 84±11 | 80±11 | <0.001 |

| FEV1/FVC <70% | 5 (4) | 11 (8) | 0.063 |

| TLC L | 6.2±1.3 | 6.2±1.3 | 0.881 |

| TLC <80% predicted | 14 (11) | 15 (11) | 0.791 |

| DLCO mmol·min−1·kPa−1 | 7.7±2.4 | 7.9±2.3 | <0.001 |

| DLCO <80% predicted | 39 (31) | 28 (21) | 0.022 |

| PO2 mmHg | 79±10 | 78±9 | 0.864 |

| PO2 <75 mmHg | 40 (32) | 45 (37) | 0.871 |

Data are presented as n, n (%) or mean±sd, unless otherwise stated. Bold type represents statistical significance. Wilcoxon signed-rank test and McNemar test were used to assess time-related differences. FVC: forced vital capacity; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; TLC: total lung capacity; DLCO: diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; PO2: partial pressure of oxygen assessed with blood gas analysis (without oxygen supplementation). #: 60 days after COVID-19 diagnosis; ¶: 100 days after COVID-19 diagnosis; +: lung function was considered impaired if FVC, FEV1, FEV1/FVC ratio, TLC or DLCO were below the predicted normal.

Serological markers

At visit 2, mild elevations in inflammatory markers such as CRP (12%), IL-6 (6%) or PCT (9%) were still present in a smaller portion of the cohort (supplementary table S3). Accordingly, biomarkers associated with COVID-19 disease severity, such as D-dimer, NT-proBNP and serum ferritin were still elevated in 27%, 23% and 17% of COVID-19 patients, respectively, at second follow-up.

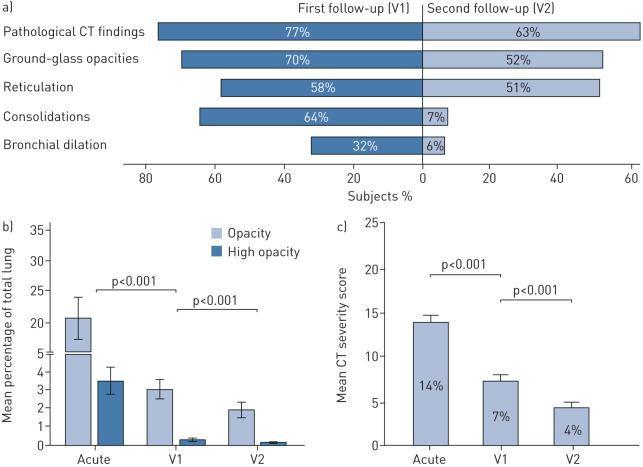

Pulmonary imaging

CT imaging revealed radiological lung abnormalities typical for COVID-19 in 77% of patients at visit 1 and in 63% of individuals at visit 2 (figure 2a). The main findings were GGOs, consolidation and reticulation. Bronchial dilation was found in a small portion of the cohort (representative CT scans are depicted in figure 3). In 75% of patients, pulmonary involvement was found bilaterally, with the lower lobes most prominently affected (supplementary table S4). Notably, by the time of visit 2, consolidations and bronchial dilations almost completely resolved, and the mean extent of GGOs significantly decreased. In contrast, reticulations only gradually improved from visit 1 to visit 2 (figure 2a). In eight patients, who presented with a clinical suspicion of an incidental PE (e.g. deteriorating dyspnoea despite resolution of radiological lung findings, tachycardia, significant hypoxia or lack of D-dimer decrease/D-dimer increase), additional contrast agent CT was performed, and one incidental PE was detected.

FIGURE 2.

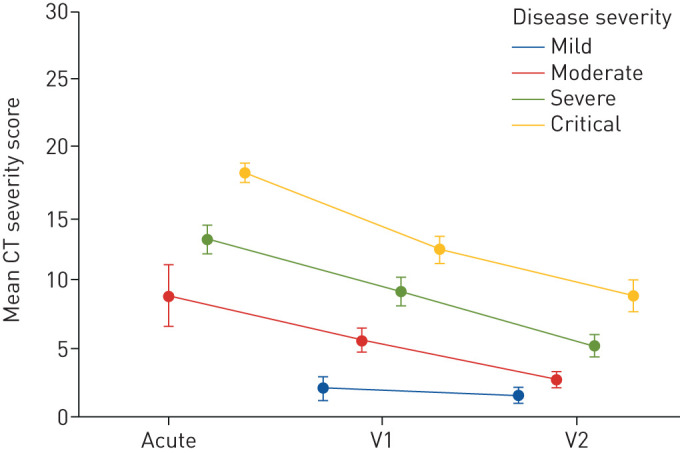

Chest computed tomography (CT) lung analysis at coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) onset and follow-up. a) The pattern of pathological findings assessed with CT at 60 (V1) and 100 days (V2) after diagnosis of COVID-19. b) Automated analysis of lung opacities assessed on CT scans from the acute disease phase, 60 days and 100 days after COVID-19 diagnosis employing Syngo.via CT Pneumonia Analysis software (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany). c) CT severity scoring by radiologists at COVID-19 onset, 60 days and 100 days after COVID-19 diagnosis. The severity score was calculated via CT evaluation by three independent radiologists who qualitatively graded lung impairment for each lobe separately (grade 0–5, with 0 for no involvement and 5 for massive involvement). A total score was achieved by summation of grades for all five lobes (maximum 25 points). Data are presented as mean±se. nacute=23, nV1=145, nV2=135.

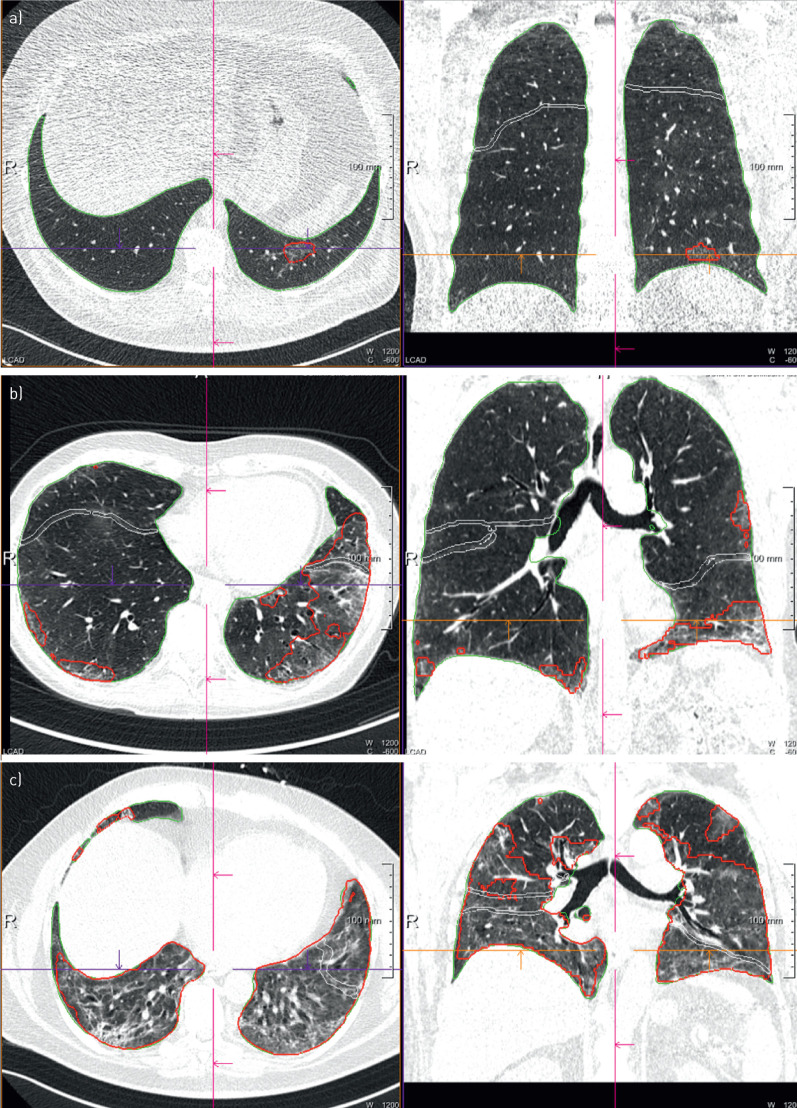

FIGURE 3.

Representative computed tomography scans of coronavirus disease 2019 patients with a) minimal, b) moderate and c) severe radiological findings at first follow-up. Percentage of opacity/high opacity a) 0.07/0.00; b) 10.29/0.69; c) 56.87/5.92.

Radiological assessment of the severity of COVID-19-related lung pathologies was performed on CT scans using both an automated software-based analysis with Syngo.via CT Pneumonia Analysis Software as well as an evaluation by three independent radiologists. Importantly, the software-based pneumonia quantification and the severity scoring by radiologists demonstrated a high correlation (correlation coefficient ρ=0.893, p<0.001). The pulmonary CT severity score unveiled a moderate structural involvement in most patients at the first follow-up, which significantly improved over time (figures 2b, c and 4). The majority of participants (81%) demonstrated an improvement in the CT severity score. Interestingly, we found only weak-to-moderate correlations of FVC (ρ=0.322, p<0.001) and FEV1 (ρ=0.237, p<0.001) measurements and moderate correlations of TLC (ρ=0.455, p<0.001) and DLCO (ρ=0.543, p<0.001) assessment with the CT severity score. The CT severity score (ρ=0.200, p<0.001) and lung function parameters including FVC (ρ=0.206, p<0.001), FEV1 (ρ=0.212, p<0.001), TLC (ρ=0.145, p<0.05) and DLCO (ρ=0.204, p<0.001) demonstrated a weak correlation to the severity of dyspnoea.

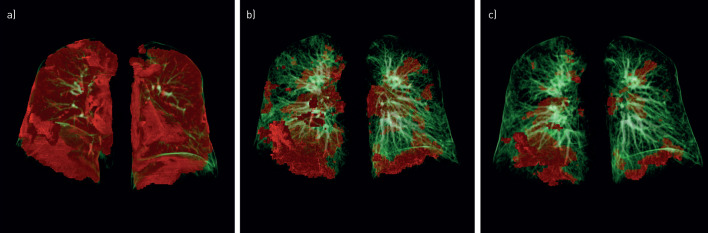

FIGURE 4.

Representative sequential computed tomography (CT) scans of a 56-year-old male coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patient during acute disease and follow-up. Pulmonary three-dimensional modelling assessed with CT is shown a) during acute COVID-19, b) at 60 days follow-up and c) at 100 days follow-up. Pulmonary opacities, mainly reflecting ground-glass opacities and/or consolidation, were quantified with Syngo.via CT Pneumonia Analysis software (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany). Areas with increased opacity are marked in red, whereas normal lung areas are indicated in green.

Finally, we analysed the impact of demographic and clinical factors on the persistence of symptoms, patient performance status and CT findings at follow-up with a series of fixed-effect ordinary and generalised linear models (supplementary figures S2, S3 and S4). These analyses revealed that the severity of acute COVID-19 (as reflected by the need for medical treatment), age, sex and pre-existing diseases such as cardiovascular diseases, pulmonary diseases, diabetes mellitus type 2 and malignancy were related to patient recovery. Despite that, a striking improvement of the CT severity score was found in patients of all COVID-19 severity groups, including subjects who needed mechanical ventilation at an ICU (figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Changes in pulmonary impairment according to computed tomography (CT) analysis in patients of different acute coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) disease severities. Time-dependent changes of CT severity score in patients with mild to critical COVID-19. Disease severity was graded by the need for acute medical treatment, as follows. Mild: outpatient care; moderate: hospitalisation without respiratory support; severe: hospitalisation with the need for oxygen supply; critical: patients treated at the intensive care unit with the need for noninvasive or invasive ventilation. Except for patients with mild COVID-19, who demonstrated only minor pulmonary CT abnormalities, all other patient groups demonstrated a significant improvement of lung abnormalities in CT scans (p=0.042 to p<0.001 for time-dependent changes). CT severity scoring ranges from 0 to 25 and was applied as detailed in the methods section. Visit 1 (V1) and visit 2 (V2) were performed 60 and 100 days after the diagnosis of COVID-19, respectively. Data are presented as mean±se.

Discussion

The ongoing pandemic considerably increases the demand for healthcare and raises concerns on physiological and radiological disease outcome in COVID-19 patients needing hospitalisation or even treatment in the ICU [20]. Accordingly, early lung function analysis of patients with COVID-19 at the time of discharge from hospital revealed a high rate of abnormalities indicative of potential interstitial lung disease. Moreover, a retrospective study 30 days after discharge had shown a reduced diffusing capacity as the central finding in 26% of post-acute COVID-19 patients [21, 22]. To our knowledge, this prospective study represents the first 3-month cardiopulmonary follow-up analysis of patients with confirmed COVID-19 including critical cases. The majority of patients enrolled in the CovILD study were previously hospitalised, male and displayed comorbidities, which have been identified as risk factors for a severe course of COVID-19 [23–26]. Importantly, 21% of patients were admitted to the ICU, comparable to the ICU admission rates of 26–33% previously published for COVID-19 patients [1, 25].

During post-acute care, patients reported a high rate of persisting dyspnoea, and one-third of COVID-19 patients displayed an impaired lung function, with a reduced diffusing capacity being the most prominent finding even >100 days after COVID-19 diagnosis. This is in accordance with observations in 110 SARS survivors 3 and 6 months after infection [14]. Long-term SARS studies revealed disturbed gas exchange as the most relevant residual finding, ranging from 15.5% to 57.2% of patients [2, 14, 27]. Furthermore, several studies on ARDS survivors have shown that their pulmonary function generally returns to normal or near to normal within 6–12 months, and predominantly DLCO may remain abnormal in patients 1 year after recovery [28, 29]. Although a relevant portion of our cohort presented with persisting cardiopulmonary impairment at follow-up, as evidenced by echocardiography or lung function testing, we observed a gradual improvement over time.

The major CT findings of patients affected by COVID-19 were previously shown to include GGO and consolidation with bilateral involvement and peripheral and diffuse distribution [30]. Importantly, this study reveals that >100 days after disease onset, two-thirds of patients had residual radiological changes, predominantly including residual GGO combined with reticulation. Since most patients had no CT scan before or during hospitalisation, pre-existing lung injury cannot be completely ruled out for the subgroup of patients with moderate-to-severe findings present at follow-up.

In line with our findings, CT abnormalities with low mean severity were detected in 75.4% of SARS survivors 6 months after admission to the hospital [15]. From a clinical perspective, it is important to note that the high prevalence of persisting radiological abnormalities in our cohort was not well reflected by pulmonary function testing. Data on the inferiority of pulmonary function testing in the screening for ILD in a population at high risk for progressive disease support these findings [31]. To date, it remains unclear whether such subclinical structural changes justify the routine repetitive use of CT imaging in follow-up care after COVID-19 pneumonia. For example, follow up-studies in ARDS survivors including chest CT have shown that persistent radiographic abnormalities were of little clinical relevance [32]. In addition, a 15-years follow-up study of 71 patients with moderate-to-severe SARS showed that the rate of interstitial abnormalities declined remarkably within the first 2 years of recovery to only 4.6% residual lung injury [27]. In line with this, our imaging findings demonstrate high reversibility of COVID-19-associated cardiopulmonary damage, and no clear signs of progressive ILD have been identified so far.

Finally, we have to acknowledge limitations of the study presented. First, the CovILD trial was initiated during the onset of the COVID-19 epidemic in Austria; thus, pre-existing comorbidities were assessed retrospectively, and cardiopulmonary evaluation prior to COVID-19 was only available in a small portion of the cohort. Thus, we cannot fully evaluate the impact of potentially pre-existing cardiopulmonary impairment on the findings presented herein. Secondly, according to the ethics approval we used low-dose CT without contrast agent to assess radiological pulmonary impairment. Whereas this strategy reduces the cumulative radiation dose and precludes contrast agent related complications, it is also associated with limitations. Although the image quality of low-dose CT was found to be sufficient, some very subtle fibrotic changes may be recognised as (nonfibrotic) reticulations due to the lower image quality. However, even in regular-dose CT, clear discrimination between residual inflammation and early fibrosis is extremely difficult, especially in patients with a clear overall improvement. Additionally, as we did not routinely use contrast agent, we did not screen the cohort for occult PE, and additional contrast CTs were only indicated in case of clinical suspicion of PE.

Conclusion

In summary, we describe significant residual clinical, functional and CT-morphological changes in the majority of COVID-19 patients, which dramatically improved within the observation period of 3 months. We conclude that follow-up care should be considered for patients with persisting clinical symptoms after COVID-19, which may include serial measures of lung function, echocardiography and CT scans of the chest.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material ERJ-03481-2020.Supplement (528.4KB, pdf)

Patient questionnaire: English version ERJ-03481-2020.Questionnaire_English (229.4KB, pdf)

Patient questionnaire: German version ERJ-03481-2020.Questionnaire_German (145.5KB, pdf)

Shareable PDF

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the dedication, commitment and sacrifice of the staff, providers and personnel in our institutions through the COVID-19 crisis and the suffering and loss of our patients as well as in their families and our community.

Footnotes

This article has an editorial commentary: https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.04423-2020

This article has supplementary material available from erj.ersjournals.com

This study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov with identifier number NCT04416100. Study protocol will be available immediately following publication for anyone who wishes to access. Individual data will not be made publicly available.

Author contributions: T. Sonnweber, J. Löffler-Ragg, S. Sahanic and I. Tancevski designed the study. T. Sonnweber, S. Sahanic, A. Pizzini, G. Weiss, A. Luger, C. Schwabl, K. Kurz, S. Koppelstätter, D. Haschka, V. Petzer, B. Sonnweber, A. Boehm, M. Aichner, D. Lener, M. Theurl, A. Lorsbach-Köhler, A. Tancevski, A. Schapfl, M. Schaber, R. Hilbe, M. Nairz, B. Puchner, D. Hüttenberger, C. Tschurtschenthaler, M. Aßhoff, A. Peer, F. Hartig, R. Bellmann, M. Joannidis, C. Gollmann-Tepeköylü, J. Holfeld, G. Feuchtner, A. Egger, G. Hoermann, A. Schroll, G. Fritsche, S. Wildner, R. Bellmann-Weiler, R. Kirchmair, R. Helbok, E. Wöll, G. Widmann, J. Löffler-Ragg and I. Tancevski performed the clinical investigations and collected the data. T. Sonnweber, G. Widmann, A. Luger, C. Schwabl, P. Tymoszuk, G. Feuchtner, H. Prosch, D. Rieder, Z. Trajanoski and F. Kronenberg performed data analysis. T. Sonnweber, S. Sahanic, A. Pizzini, G. Widmann, A. Luger, C. Schwabl, P. Tymoszuk, D. Rieder, Z. Trajanoski, F. Kronenberg, G. Weiss, J. Löffler-Ragg and I. Tancevski interpreted data. T. Sonnweber, G. Weiss, H. Prosch, F. Kronenberg, R. Kirchmair, G. Widmann, J. Löffler-Ragg and I. Tancevski wrote the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest: T. Sonnweber has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: S. Sahanic has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: A. Pizzini has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: A. Luger has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: C. Schwabl has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: B. Sonnweber has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: K. Kurz has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: S. Koppelstätter has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: D. Haschka has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: V. Petzer has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: A. Boehm has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: M. Aichner has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: P. Tymoszuk has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: D. Lener has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: M. Theurl has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: A. Lorsbach-Köhler has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: A. Tancevski has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: A. Schapfl has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: M. Schaber has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: R. Hilbe has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: M. Nairz has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: B. Puchner has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: D. Hüttenberger has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: C. Tschurtschenthaler has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: M. Aßhoff has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: A. Peer has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: F. Hartig has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: R. Bellmann has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: M. Joannidis has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: C. Gollmann-Tepeköylü has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: J. Holfeld has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: G. Feuchtner has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: A. Egger has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: G. Hoermann has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: A. Schroll has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: G. Fritsche has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: S. Wildner has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: R. Bellmann-Weiler has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: R. Kirchmair has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: R. Helbok has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: H. Prosch has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: D. Rieder has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: Z. Trajanoski has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: F. Kronenberg has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: E. Wöll has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: G. Weiss has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: G. Widmann has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: J. Löffler-Ragg has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: I. Tancevski reports an Investigator Initiated Study (IIS) grant from Boehringer Ingelheim (IIS 1199-0424).

Support statement: This study was supported by the Austrian National Bank Fund (Project 17271, J. Löffler-Ragg), and the “Verein zur Förderung von Forschung und Weiterbildung in Infektiologie und Immunologie, Innsbruck” (G. Widmann). Additionally, this study was supported by Boehringer Ingelheim RCV GmbH & Co KG (BI). BI had no role in the design, analysis or interpretation of the results in this study. BI was given the opportunity to review the manuscript for medical and scientific accuracy as it relates to BIPI substances, as well as intellectual property considerations. Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

References

- 1.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020; 395: 497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hui DS, Joynt GM, Wong KT, et al. Impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) on pulmonary function, functional capacity and quality of life in a cohort of survivors. Thorax 2005; 60: 401–409. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.030205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blanco-Melo D, Nilsson-Payant BE, Liu WC, et al. Imbalanced host response to SARS-CoV-2 drives development of COVID-19. Cell 2020; 181: 1036–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore JB, June CH. Cytokine release syndrome in severe COVID-19. Science 2020; 368: 473–474. doi: 10.1126/science.abb8925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGonagle D, Sharif K, O'Regan A, et al. The role of cytokines including interleukin-6 in COVID-19 induced pneumonia and macrophage activation syndrome-like disease. Autoimmun Rev 2020; 19: 102537. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peiris JS, Chu CM, Cheng VC, et al. Clinical progression and viral load in a community outbreak of coronavirus-associated SARS pneumonia: a prospective study. Lancet 2003; 361: 1767–1772. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13412-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walls AC, Park YJ, Tortorici MA, et al. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell 2020; 181: 281–292. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaimes JA, André NM, Chappie JS, et al. Phylogenetic analysis and structural modeling of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein reveals an evolutionary distinct and proteolytically sensitive activation loop. J Mol Biol 2020; 432: 3309–3325. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2020.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monteil V, Kwon H, Prado P, et al. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 infections in engineered human tissues using clinical-grade soluble human ACE2. Cell 2020; 181: 905–913. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imai Y, Kuba K, Penninger JM. The discovery of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and its role in acute lung injury in mice. Exp Physiol 2008; 93: 543–548. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.040048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Imai Y, Kuba K, Rao S, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 protects from severe acute lung failure. Nature 2005; 436: 112–116. doi: 10.1038/nature03712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fu Y, Cheng Y, Wu Y. Understanding SARS-CoV-2-mediated inflammatory responses: from mechanisms to potential therapeutic tools. Virol Sin 2020; 35: 266–271. doi: 10.1007/s12250-020-00207-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuba K, Imai Y, Rao S, et al. A crucial role of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in SARS coronavirus-induced lung injury. Nat Med 2005; 11: 875–879. doi: 10.1038/nm1267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hui DS, Wong KT, Ko FW, et al. The 1-year impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on pulmonary function, exercise capacity, and quality of life in a cohort of survivors. Chest 2005; 128: 2247–2261. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ng CK, Chan JW, Kwan TL, et al. Six month radiological and physiological outcomes in severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) survivors. Thorax 2004; 59: 889–891. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.023762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ngai JC, Ko FW, Ng SS, et al. The long-term impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on pulmonary function, exercise capacity and health status. Respirology 2010; 15: 543–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2010.01720.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Das KM, Lee EY, Singh R, et al. Follow-up chest radiographic findings in patients with MERS-CoV after recovery. Indian J Radiol Imaging 2017; 27: 342–349. doi: 10.4103/ijri.IJRI_469_16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization (WHO). Coronavirus. 2020. www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus#tab=tab_3 Date last accessed: October 20, 2020.

- 19.Hansell DM, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, et al. Fleischner Society: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging. Radiology 2008; 246: 697–722. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2462070712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rees EM, Nightingale ES, Jafari Y, et al. COVID-19 length of hospital stay: a systematic review and data synthesis. BMC Med 2020; 18: 270. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01726-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mo X, Jian W, Su Z, et al. Abnormal pulmonary function in COVID-19 patients at time of hospital discharge. Eur Respir J 2020; 55: 2001217. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01217-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frija-Masson J, Debray MP, Gilbert M, et al. Functional characteristics of patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia at 30 days post-infection. Eur Respir J 2020; 56: 2001754. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01754-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City Area. JAMA 2020; 323: 2052–2059. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy region, Italy. JAMA 2020; 323: 1574–1581. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020; 395: 1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klein SJ, Fries D, Kaser S, et al. Unrecognized diabetes in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Crit Care 2020; 24: 406. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03139-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang P, Li J, Liu H, et al. Long-term bone and lung consequences associated with hospital-acquired severe acute respiratory syndrome: a 15-year follow-up from a prospective cohort study. Bone Res 2020; 8: 8. doi: 10.1038/s41413-020-0084-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herridge MS, Cheung AM, Tansey CM, et al. One-year outcomes in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 683–693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheung AM, Tansey CM, Tomlinson G, et al. Two-year outcomes, health care use, and costs of survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 174: 538–544. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200505-693OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y, Dong C, Hu Y, et al. Temporal changes of CT findings in 90 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia: a longitudinal study. Radiology 2020; 296: E55–E64. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suliman YA, Dobrota R, Huscher D, et al. Brief report: pulmonary function tests: high rate of false-negative results in the early detection and screening of scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015; 67: 3256–3261. doi: 10.1002/art.39405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burnham EL, Janssen WJ, Riches DW, et al. The fibroproliferative response in acute respiratory distress syndrome: mechanisms and clinical significance. Eur Respir J 2014; 43: 276–285. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00196412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material ERJ-03481-2020.Supplement (528.4KB, pdf)

Patient questionnaire: English version ERJ-03481-2020.Questionnaire_English (229.4KB, pdf)

Patient questionnaire: German version ERJ-03481-2020.Questionnaire_German (145.5KB, pdf)

This one-page PDF can be shared freely online.

Shareable PDF ERJ-03481-2020.Shareable (830.8KB, pdf)