Abstract

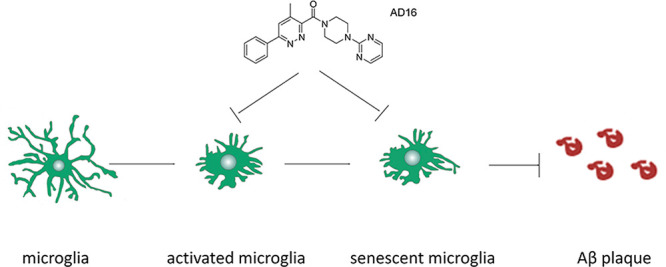

Microglial dysfunction is involved in the pathological cascade of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The regulation of microglial function may be a novel strategy for AD therapy. We previously reported the discovery of AD16, an antineuroinflammatory molecule that could improve learning and memory in the AD model. Here, we studied its properties of microglial modification in the AD mice model. In this study, AD16 reduced interleukin-1β (IL-1β) expression in the lipopolysaccharide-induced IL-1β-Luc transgenic mice model. Compared with mice receiving placebo, the group treated with AD16 manifested a significant reduction of microglial activation, plaque deposition, and peri-plaques microgliosis, but without alteration of the number of microglia surrounding the plaque. We also found that AD16 decreased senescent microglial cells marked with SA-β-gal staining. Furthermore, altered lysosomal positioning, enhanced Lysosomal Associated Membrane Protein 1 (LAMP1) expression, and elevated adenosine triphosphate (ATP) concentration were found with AD16 treatment in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated BV2 microglial cells. The underlying mechanisms of AD16 might include regulating the microglial activation/senescence and recovery of its physiological function via the improvement of lysosomal function. Our findings provide new insights into the AD therapeutic approach through the regulation of microglial function and a promising lead compound for further study.

Keywords: AD16, Alzheimer’s disease, lysosome, microglia, senescent cell

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is an age-associated neurodegenerative disorder associated with irreversible neural death and progressive cognitive decline.1 Although great efforts toward drug discovery have been made in recent years, there is no new drug for AD therapy that has been approved since 2004 and more than 400 failed clinical trials were performed in the last 15 years.2 The majority of efforts to develop new therapeutics have thus far focused on targeting aggregated amyloid-β (Aβ) and neurofibrillary tangles, which are two hallmarks for AD.1 Unfortunately, these approaches have failed in several phase III trials during the last three years.3−5 For this reason, it is extremely important to identify new targets that could potentially offer novel disease-modifying therapies.

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have recently identified complement component [3b/4b] receptor 1, Clusterin,6 Cluster of Differentiation 33 (CD33), adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-binding cassette transporter A7,7 and triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 28 as the risk genes for late-onset AD. This implies that dysregulation of the immune system may be involved in the pathological cascade of AD. Neuroinflammation is an innate immune response in the central nervous system (CNS) by which the brain and spinal cord react to danger signals, such as diverse pathogens or endogenous host-derived signals released during cellular damage.9 Inflammation is necessary for eliminating invading agents, clearing damaged cells, and promoting tissue repair, but excessive inflammatory response causes or contributes to tissue damage and has negative effects on the pathogenesis of degenerative diseases, such as AD, Parkinson’s disease (PD), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.9−11 As resident macrophage-like cells of the CNS, microglia are the main cell type involved in innate immune response in the brain. Activated microglia produce a wide range of proinflammatory cytokines and neurotoxic mediators, including interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and nitric oxide (NO).12 Chronic inflammatory response plays an essential role in cellular senescence, which may exacerbate age-related phenotypes and promote aging-associated disorders.13,14 The clearance of senescent glial cells prevents tau-dependent pathology and cognitive decline in the AD model.15 Therefore, suppression of microglial activation and senescence could be a strategy to treat AD.11

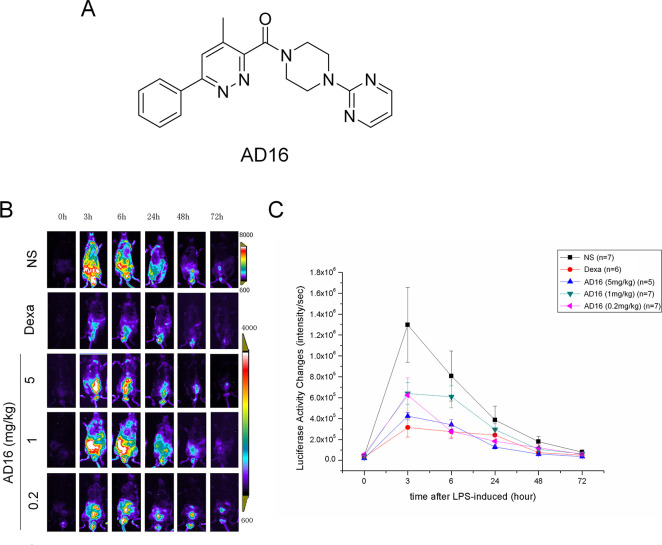

Previously, we identified a synthetic compound called AD16 (also named GIBH130, PubChem CID: 50938773) (Figure 1A) which significantly decreased IL-1β expression in N9 cells and IL-6 expression in AD animals.16 The possible molecular mechanisms that underlie the anti-inflammatory effects of AD16 may link to the inhibition of kinase activity, indicted by the similar chemical structure of AD16 to a p38α MAPK inhibitor.17 Behaviorally, it restored cognition in Aβ-injected mice and APPswe/PS1ΔE9 (APP/PS1) mice.16 These events raise the possibility that AD16 alters microglial function in the brain of AD. In this study, first we confirmed the in vivo anti-inflammatory effect of AD16 using the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induced IL-1β-Luc transgenic mice model. Then, we studied whether AD16 altered microglial function in APP/PS1 mice as well as the underlying mechanisms.

Figure 1.

AD16 administration reduces IL-1β expression in cHS4I-hIL-1βP-Luc transgenic mice. Male cHS4I-hIL-1βP-Luc transgenic mice were randomized to receive vehicle or AD116 for 6 days, and LPS was injected into the intraperitoneal cavity on day 3. In vivo bioluminescent imaging was performed using an IVIS imaging system. The structures of AD16 (A). Representative photomicrographs display IL-1β production in cHS4I-hIL-1βP-Luc transgenic mice using luciferase expression detection (B). Quantification of the luciferase expression at 3, 6, 48, and 72 h after LPS injection (n = 5 per group) with or without AD16 treatment (C). Statistical comparisons were performed by one-way ANOVA. Post hoc group-wise comparisons were conducted using the Tukey test. Data are represented as mean ± SD.

Results and Discussion

AD16 Administration Reduces IL-1β Expression and Microglial Activation

AD16 (Figure 1A) was identified by phenotype screening with the capacity to decrease IL-1β expression in N9 microglial cells.16 IL-1β is an important pro-cytokine which is mainly produced by microglia in the brain. High concentrations of IL-1β can be detected in the brains of patients with AD.11 To further elucidate the in vivo effects of AD16 on IL-1β production, we conducted a detailed analysis in cHS4I-hIL-1βP-Luc transgenic mice using a luciferase expression detection. High dose AD16 administration could decrease LPS-induced luciferase expression at 3 h (p = 0.03549), 6 h (p = 0.035612) and 48 h (p = 0.047503) after LPS injection, and low dose AD16 also decreased IL-1β expression but only at 6 h (p = 0.027806) (Figure 1B,C).

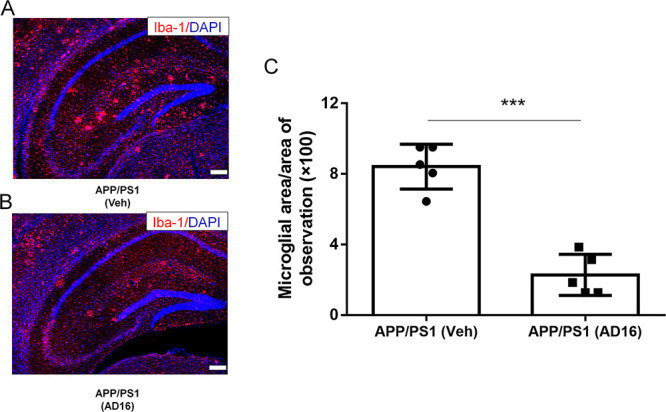

Then, we investigated the effects of AD16 on microglial activation in APP/PS1 mice. Microgliosis was evident in APP/PS1 mice, as previously observed by others.18,19 In the hippocampus, we observed the area of ionized calcium binding adapter molecule 1 (Iba-1) positive microglia in AD16-administered AD mice was decreased by 71.0% compared to that of the control group (p = 0.0007, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

AD16 Reduces Microglial Area in the Brain of APP/PS1 Mice. Nine-month-old male APP/PS1 mice were either orally dosed with vehicle or AD16 for 3 months. Representative immunostaining of Iba-1 in the hippocampus of APP/PS1 group (A) and AD16 treated group (B). Quantification of the area of Iba-1 positive microglia in the brain of AD mice (n = 5 per group) receiving AD16 or vehicle (C). Scale bar: 200 μm. Statistical comparisons were performed by unpaired Student’s t test. Data are presented as means ± SD; ***p < 0.001.

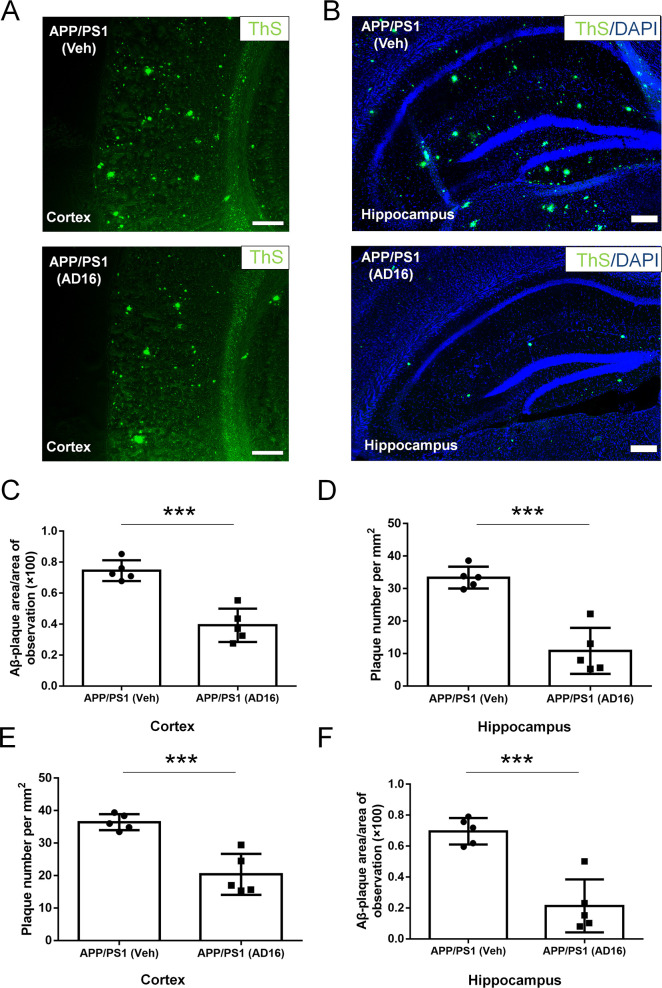

AD16 Treatment Reduces Amyloid Plaque Deposition in AD Mice

Aβ aggregates into insoluble clusters, or plaques, in the AD brain as the disease progresses.20 The formation of such plaques in the cortical and hippocampal regions is directly related to learning and memory deficits in AD.20 In the cortex and hippocampus of AD mice, we observed numerous plaques at 12 months of age. Total numbers and areas of plaques in whole brains of AD16-administered AD mice were notably decreased compared to those with the vehicle administration. This trend was consistent in both the cortical (number, decreased by 44.1%, p = 0.0007; area, decreased by 47.3%, p = 0.00025) and hippocampal (number, decreased by 67.6%, p = 0.0002; area, decreased by 69.3%, p = 0.00049) regions (Figure 3). These findings demonstrate that AD16 treatment alleviated the Aβ burden.

Figure 3.

AD16 treatment reduces amyloid plaque deposition in AD mice. Nine-month-old male APP/PS1 mice were either orally dosed with vehicle or AD16 for 3 months. Representative staining of ThS positive amyloid plaque in the cortex (A) and hippocampus (B) of the APP/PS1 group and AD16 treated group. Quantification of total areas (C,D) and numbers (E,F) of plaques in whole brains of AD mice receiving AD16 or vehicle in the hippocampus and cortex (n = 5 per group). Scale bar: 200 μm. Statistical comparisons were performed by unpaired Student’s t test. Data are presented as means ± SD; ***p < 0.001.

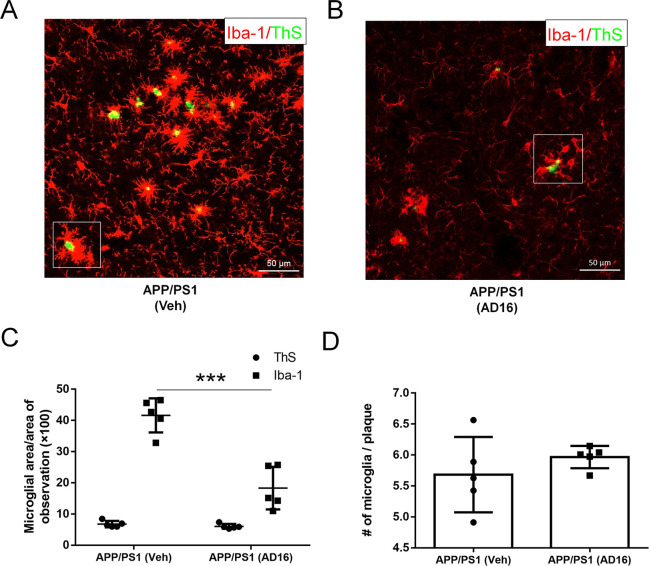

AD16 Alleviates Microglial Activation Close to Amyloid Deposition but Does Not Alter Microglia Number

A striking feature of the microglia in the AD brain is marked clustering around Aβ deposition.21 Plaque-associated microglia display an activated and polarized morphology which has a close interaction with Aβ.21 We analyzed the area of microglia close to amyloid deposition (the area of amyloid deposition as control). AD16 treatment down-regulated the area of Iba-1 positive microglia by 56.0% (p = 0.00033) (Figure 4A–C; Supporting Information, Figures S1,S2). However, the number of microglia around amyloid deposition was not affected by AD16 treatment (Figure 4D). Recently, Pluvinage and colleagues identified that blocking microglial CD22 restores homeostasis in the aging brain and promotes the clearance of Aβ in vivo.22 In our study, with the treatment of AD16, CD22-positive cells were significantly decreased by 64.4% (p = 0.026) in the hippocampus of APP/PS1 mice (Figure S3). The finding implies that AD16 may promote Aβ clearance by microglia.

Figure 4.

AD16 alleviates microglial activation close to amyloid deposition but does not alter microglia number. Nine-month-old male APP/PS1 mice were either orally dosed with vehicle or AD16 for 3 months. Representative costaining of Iba-1 and ThS positive amyloid plaque in the hippocampus of APP/PS1 group (A) and AD16 treated group (B). Quantification of area (C) and number (D) of Iba-1 positive microglia close to amyloid deposition (n = 5 per group). Scale bar: 50 μm. Statistical comparisons were performed by unpaired Student’s t test. Data are presented as means ± SD; ***p < 0.001.

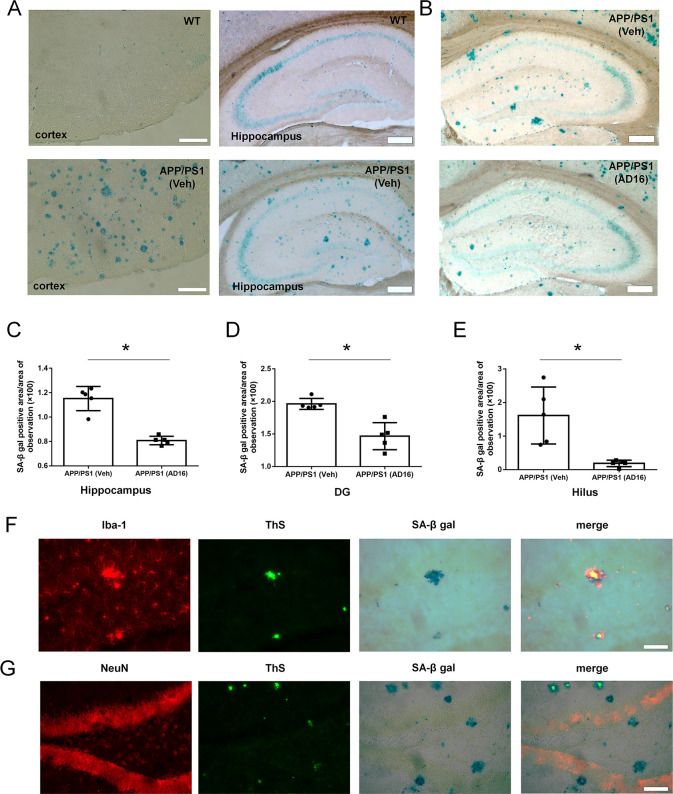

AD16 Administration Reduces Cell Aging in the Dentate Gyrus

Cellular senescence is accelerated in the brain of AD compared to normal aging.23 Senescent cells lose/alter their physiological function, release proinflammatory mediators, and impair adjacent tissue.24,25 The ability of Aβ clearance in senescent microglial cells is markedly decreased.26 To assess whether AD16 influences cell aging, we performed SA-β-gal staining, which is a classic marker for cellular senescence. The SA-β-gal activity was increased in the brain tissue of APP/PS1 mice compared to WT mice both in the cortex and hippocampus (Figure 5A). Compared to the vehicle treatment group, AD16 treatment reduced the area of SA-β-gal positive cells by 27.5% in the hippocampus (p = 0.037), 28.0% in dentate gyrus (DG) (p = 0.017) and 84.9% (p = 0.033) in the hilus of the DG part (Figure 5B–E). SA-β-gal positive cells were mainly distributed in dentate hilus and molecular layers of the hippocampus (Figure 5B) and were identified as microglia that were immunoreactive for Iba-1 (a marker for microglia) but not for NeuN (a marker for neuron) (Figure 5F,G).

Figure 5.

AD16 administration reduces cell aging in the dentate gyrus. Nine-month-old male APP/PS1 mice were either orally dosed with vehicle or AD16 for 3 months. The SA-β-gal activity was increased in the brain tissue of APP/PS1 mice compared to WT mice both in the cortex and hippocampus (A). Representative staining of SA-β-gal in the hippocampus of the APP/PS1 group and AD16 treated group (B). Quantification of the area of SA-β-gal positive cells in the total hippocampus (C), dentate gyrus (DG) of the hippocampus (D), and hilus of the DG part (E) in the brain of AD mice receiving AD16 or vehicle (n = 5 per group). SA-β-gal positive cells were identified through immunostaining with the Iba-1 antibody (F) or NeuN antibody (G). Scale bar: 200 μm. Statistical comparisons were performed by unpaired Student’s t test. Data are presented as means ± SD; *p < 0.05.

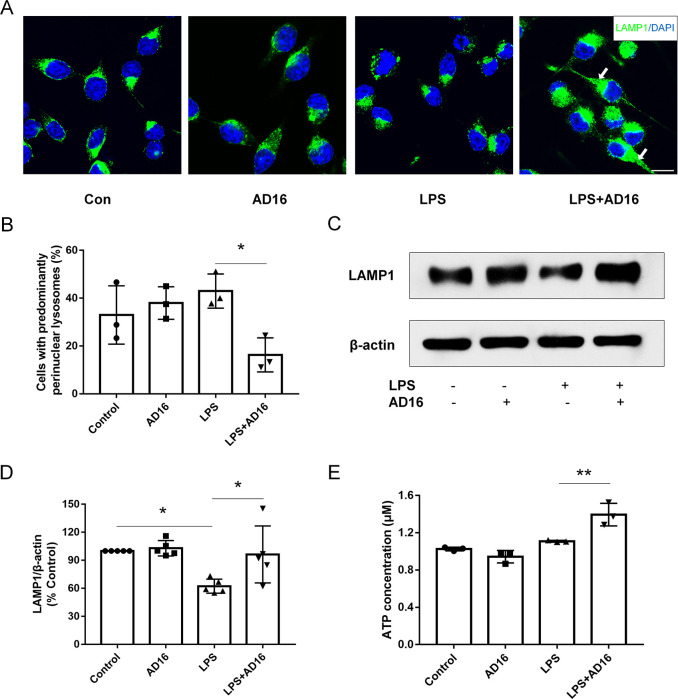

AD16 Alters Lysosomal Distribution in BV2 Microglial Cells

Lysosomes play a central role in cellular homeostasis by regulating the cellular degradative machinery.27 Multiple cell functions are affected by different lysosomal positioning, such as autophagosome formation.28 The abnormal lysosomes are often clustered in the juxtanuclear area, as documented in PD,29 neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 3,30 and mucolipidosis type IV.31 LPS treatment induced lysosomal clustering, which inhibited phagolysosome fusion in dendritic cells but not macrophages.32 Similar to macrophages, LPS did not induce lysosomal clustering in BV2 microglial cells. However, with AD16 treatment Lysosomal Associated Membrane Protein 1 (LAMP-1)-positive organelles showed less peri-nuclear distribution in BV2 microglial cells (Figure 6A,B). These were also confirmed with lysotracker staining (Figure S4). Furthermore, the Western blot study suggested that LPS treatment reduced the expression of LAMP1, and AD16 enhanced its expression with LPS stimulation (Figure 6C, D; Figure S5). Previous studies suggest that the lysosomal position coordinates cellular nutrient responses,33 so we detected the ATP level in BV2 cells. In our study, the intracellular ATP level in LPS-activated BV2 cells was increased by 25.7% with AD16 treatment (Figure 6E). These results taken together indicate that AD16 may improve lysosomal function by altering their position.

Figure 6.

AD16 alters lysosomal distribution in BV2 microglial cells. BV2 cells were treated with or without AD16 for 24 h in serum-free Opti-MEM medium incubated with LPS (100 ng/mL). Lysosomal distributions were detected through the staining of LAMP1 in BV2 microglial cells treated with AD16 or vehicle (A). Quantification of LAMP1 distribution in BV2 microglial cells (n = 3) (B). Immunoblot assays against LAMP1 protein are shown (C). Statistical data of the expressions of LAMP1 from three independent experiments are shown (n = 3). Protein blots were analyzed using ImageJ and bands were normalized to their respective β-actin loading controls. Data are representative of the average fold change with respect to control for three independent experiments. (D). ATP levels were detected in LPS-activated BV2 cells with AD16 or vehicle (n = 3) (E). Scale bar: 20 μm. Statistical comparisons were performed by two-way ANOVA. Post hoc group-wise comparisons were conducted using the Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. Data are presented as means ± SD; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Here, we report that (a) AD16 treatment decreases IL-1β expression in cHS4I-hIL-1βP-Luc transgenic mice induced by LPS and reduces microglial activation in the hippocampus of AD mouse; (b) AD16 reduces amyloid plaques and microglia area in proximity to amyloid deposition, but does not alter the microglia number per plaque; (c) AD16 reduces the number of senescent cells in the hippocampus of AD mice, further identified as microglia; (d) AD16 treatment alters lysosomal positioning, enhances LAMP1 expression, and elevates ATP concentration in LPS-stimulated BV2 cells.

In our study, we observed that AD16 inhibited the accumulation of Aβ deposits in AD mice. Microglia, the first responder to Aβ accumulation, can uptake extracellular Aβ, which are then degraded via the autophagic/lysosomal system.24,34 Activated microglia contributes to the formation and growth of Aβ plaques. Inflammatory milieu is known to impair the ability of microglia to properly internalize and degrade Aβ during AD progression.35 As a neuroinflammation inhibitor, the mechanism of AD16 in reducing plaques may be due to the altered microglia function. Several groups discovered that anti-inflammatory therapy enhanced microglial Aβ clearance directly. The anti-inflammatory drugs Cromolyn and Rutin reduce levels of Aβ by promoting microglial phagocytosis.36,37N,N′-diacetyl-p-phenylenediamine restores microglial phagocytosis and attenuates cognitive deficits in AD transgenic mouse model through its suppression of neuroinflammation.38 Hickman et al. found that proinflammatory cytokines treatment could decrease gene expressions involved in Aβ clearance (such as Aβ-binding scavenger receptors scavenger receptor A and CD36) and reduce Aβ uptake.39 It may be the underlying mechanism of anti-inflammatory therapy resulted in the lower number of plaques in AD mice. In our study, AD16 reduced the area of plaque-associated microglia but did not affect their numbers, suggesting microglial hypertrophy and activation was decreased. Activated microglia marker, such as F4/F80, was not used in this study, which should be considered as a limitation of this study. It will be used in future mechanism studies. Consistent with the observations above, our results showed that AD16 might attenuate the Aβ burden in APP/PS1 mice by promoting microglial phagocytosis. The reduction of Aβ plaque may also be due to the lower level of Aβ production with the treatment of AD16. To exclude this possibility, the BACE activity or APP levels should be detected in animals and cell culture in the future.

The administration of AD16 reduced the number of senescent cells in the DG and molecular layer of the hippocampus of AD mice, especially in the dentate hilus. The senescent cells in these regions mainly are microglia confirmed by stained with Iba-1 antibody. Cellular senescence is an elaborate stress response among cell types within different types of tissues, promoting a variety of age-related diseases.40 Multiple cell types seem to demonstrate senescent-like alterations in AD.26 For example, microglia from AD patients possess shorter telomeres compared with age-matched controls.41 With aging, microglial cells exhibit dystrophic changes, which are thought to be distinct from their typical reactive morphology.23 Senescent microglial cells show functional impairments, such as reduced engulfment of Aβ,42 increased activation and enhanced release of inflammatory cytokines,43 as well as the loss of neuroprotective potential.44 In a recent study it was found that, in response to repeated lipopolysaccharide administration (mimicking chronic inflammation), cultured BV2 microglial cells displayed several signs of senescence, including growth arrest, enhanced SA-β gal activity, and senescence-associated heterochromatin foci.45 Furthermore, senescent astrocytes and oligodendrocyte progenitor cells could also be found surrounding the amyloid plaques.46,47 Xia et al. proposed that inhibition of astrocyte senescence could be a therapeutic strategy for the treatment of age-associated neurodegenerative diseases.48 More experiments should be performed in the future to determine whether AD16 could inhibit astrocyte and oligodendrocyte progenitor cell senescence.

Lysosomal defects, influencing degradative capacity and leading to the accumulation of dysfunctional proteins, have been associated with the pathogenesis of a neurodegenerative disorder such as AD.49 Enhancing lysosomal function leads to increased lysosomal degradation of Aβ, decreased microglial inflammation and alleviated cellular senescence.50−52 Erie et al. found that the peri-nuclear accumulation of lysosomes was increased in a cellular model of Huntington’s disease, leading to premature fusion of lysosomes with autophagosomes.29 LPS treatment induces lysosomal clustering and inhibits phagolysosome fusion in dendritic cells.32 However, no clustering of lysosomes was evident after 16 h of LPS treatment in macrophages. As the resident macrophages of the CNS, microglia also did not display the increase of lysosomal clustering with LPS treatment in our study. AD16 treatment reduced lysosomal peri-nuclear distribution and enhanced LAMP1 expression in BV2 microglial cells, suggesting AD16 may improve lysosomal function, such as promotion of phagolysosome fusion. This may be the reason why AD16 treatment decreases plaque number and microglial activation/senescence in the brain of APP/PS1 mice. However, the link between lysosomal position and Aβ phagocytosis was not established in this study. In the future, to elucidate whether AD16 enhances microglial phagocytosis, the markers of phagocytosis (e.g., CD68) and receptors involved in Aβ clearance (e.g., Aβ-binding scavenger receptors scavenger receptor A and CD36) in treated cells and/or APP/PS1 mice should be stained. Furthermore, Aβ stimulated BV2 cells were not used in our in vitro study, which should be considered as a limitation of this study. The direct mechanism of AD16 will be studied future work, and the direct target in Aβ stimulated BV2 cells or primary microglial cells will be explored.

In conclusion, our results demonstrated that AD16 could reduce amyloid plaques and modify microglia in the hippocampus of APP/PS1 mice. However, the underlying mechanisms of the antiamyloidogenic effects of AD16 still need to be further clarified. Our findings provide new insights into the AD therapeutic approach through the regulation of microglial function and a promising lead compound for further study.

Materials and Methods

IL-1β Expression in cHS4I-hIL-1βP-Luc Transgenic Mice

All the animal studies complied with the ARRIVE guidelines. The experimental procedures for the use and care of the animals were approved by the Ethics Committee of Guangzhou Medical University. Male cHS4I-hIL-1βP-Luc transgenic mice were purchased from Shanghai Biomodel Organism Science & Technology Development Company (Shanghai, China) and randomized to five groups (n = 5 per group), group 1 = AD16 high dose group (5 mg/kg), group 2 = AD16 middle dose group (1 mg/kg), group 3 = AD16 low dose group (0.2 mg/kg), group 4 = dexamethasone group (3 mg/kg), and group 5 = saline group. All of the drugs were administered intragastrically daily for 6 days. LPS was injected into the intraperitoneal cavity at a dose of 3 mg/kg on day 3. In vivo bioluminescent imaging was performed using an IVIS imaging system (Xenogen, CA, USA) as previously described.53 Potassium luciferin (GoldBio, MO, USA) was intraperitoneally injected into mice at a dose of 150 mg/kg. Then, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane/oxygen and maintained in the imaging chamber. Twelve min after luciferin injection, mice were imaged. Photons emitted were quantified using LivingImage software (Xenogen, CA, USA) and results were presented in photons emitted per second. Imaging analysis was performed on hour 0, 3, 6, 24, 48, and 72 after LPS injection.

AD Animals

The transgenic mice which carry two transgenes, the mouse/human chimeric APPswe and human PS1ΔE9 were purchased from Nanjing Biomedical Research Institute of Nanjing University. Animals were kept on standardized food pellets and water ad libitum. Heterozygous females were bred with wild-type C57BL/6 males bought locally. As sex differences were observed in the pathologic features of APP/PS1 mice,54 offspring male heterozygous mice were used within all animal experiments to avoid the influence of gender. Nine-month-old male mice were randomized to two groups (n = 5 per group), one receiving AD16 (0.25 mg/kg; dissolved in 0.5% CMC-Na as the vehicle) and the control group receiving vehicle via gavage until 12 months of age.

Fixation and Tissue Processing

After the mice were sacrificed, the brains were dissected and fixed by immersion in freshly prepared 4% PFA dissolved in PBS (pH 7.5) for 72 h (with changes of the fixative every 24 h). Fixed brains were transferred to 10 and 20% sucrose in PBS, subsequently. Brains were frozen in precooled isopentane and stored at −80 °C. Serial coronal sections of one hemisphere were cut at 50 μm on a freezing microtome (Leica, Germany) and placed in 24-well plates, each well being filled with 1×PBS. For long-term storage, brain sections were placed into cryoprotectant solution (30 mL of ethylene glycol, 25 mL of glycerin, and 45 mL of PBS) and could be stored at −20 °C until further processing.

Thioflavins S (ThS) Staining, SA-β-gal Staining, and Immunohistochemistry

The sliced brains were stained for 7 min with 500 μM of ThS (Sigma, MO, USA) dissolved in 50% ethanol. The sections were then rinsed with 100, 95, and 70% ethanol and PBS, successively. Finally, the slices were photographed using a BX71 microscope from Olympus (Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a motorized stage controller, and pictures were captured with the program “Cell” (Olympus). To detect microglia in the presence of plaques, after being stained with ThS, the slices were incubated with 1% Triton X-100 for 20 min at room temperature (RT), and then incubated in 10% blocking solution (0.1 M TBS with 10% normal goat serum, 0.25% Triton X-100) for 1.5 h at RT. After being blocked, sections were incubated with a rabbit monoclonal primary antibody against Iba-1 (cat. no. 019-19741, Wako, Japan; 1:1000) in 10% blocking solution for 48 h at 4 °C. Subsequently, sections were incubated with goat antirabbit conjugated with Alexa 568 (cat. no. A-11011, Invitrogen, CA, USA; 1:2000) as the secondary antibodies in 10% blocking solution at RT for 2 h. DAPI (Sigma, MO, USA; 1:2000) was used for the visualization of nuclei. Images of microglia staining were captured with an LSM 800 microscope (Zeiss, Germany).

Brain sections were then immersed in a fixation solution for 15 min and subsequently rinsed with PBS 3 times. Then 1 mL per well of working solution of β-galactosidase with X-Gal was placed, and the plate was maintained at 37 °C overnight (senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining kit from Beyotime, China). SA-β-gal positive areas were quantified by counting stained and unstained areas and expressed as the percent of SA-β-gal-positive area over the total area. After being stained with a working solution of β-galactosidase with X-Gal, the sections were incubated with a mouse monoclonal primary antibody against NeuN (cat. no. Mab377, Chemicon, CA, USA; 1:1000) or Iba-1 to determine the cell type of SA-beta-gal positive cells. Subsequently, sections were incubated with goat antirabbit or mouse IgG (cat. no. A-11004, Invitrogen, CA, USA; 1:2000) conjugated with Alexa 568 together with DAPI. The images were captured using the BX71 microscope.

For quantification, the area and/or number of amyloid plaques, Iba-1 positive microglia, and senescent cells were measured using ImageJ software (NIH, MD, USA). The area for quantification of amyloid plaques was the cortex and whole hippocampal formation (without distinguishing between areas of CA1, CA2, CA3, and DG). The Aβ staining area was calculated relative to the total area of the analyzed region. The area for quantification of Iba-1 positive microglia was the whole hippocampus. The plaque-associated area was identified, and the average percentage of plaque area in each plaque-associated area (plaque area/plaque-associated area) was similar both in vehicle and AD16 treated group. Then, we analyzed the average area and number of the Iba-1 positive cells around each plaque (Iba-1 positive area/plaque-associated area) for each mouse. The senescent cells were counted in the whole hippocampus, and in the DG/dentate hilus of the hippocampus specifically. The SA-β-gal staining area was calculated relative to the total area of the analyzed region. Quantitative analysis of positive cells was calculated in at least five random microscopic fields of each section. Three sections per mouse and five mice per group were chosen for analysis. Three coronal sections were taken from the anterior, middle, and posterior hippocampus of the animal, respectively. All of the counting was performed in a blinded fashion.

Cell Culture

BV2 cells were brought from Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China), and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen, CA, USA) and antibiotics [100 U/mL penicillin (Invitrogen, CA, USA), 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen, CA, USA)]. Cells from passages 3–5 were used for all assays. The cells were activated by 0.1 μg/mL LPS (Sigma, MO, USA) with or without AD16 (1 μM) for 24 h in serum-free Opti-MEM medium (Invitrogen, CA, USA). Appropriate controls included vehicle control and LPS, but only stimulated cells were included in the analysis. For immunofluorescence, cells were stained with lysosomes with primary antibodies detecting LAMP1 (cat. no. ab208943, Abcam, MA, USA; 1:200) and then were incubated with goat antirabbit IgG conjugated with Alexa 488 (cat. no. A-11034, Invitrogen, CA, USA; 1:2000) together with DAPI.

Quantification of the Lysosomal Distribution

To score lysosomal distribution, a method described by Erie et al.29 with modifications was used. The nuclear region of a cell was first outlined based on DAPI staining using ImageJ. The perinuclear outline was defined as 2 μm away from the nuclear. The LAMP1 signal was adjusted to saturation to outline the whole cell. The cells with the perinuclear-dominant lysosomal pattern were defined as more than 70% of LAMP1-positive vesicles localized in the perinuclear region. The data are expressed as a proportion of cells with predominantly perinuclear lysosomes.

Detection of Cellular ATP Levels

The level of ATP in BV2 cells was determined using the ATP Bioluminescence Assay Kit (Beyotime, China). The cells were lysed and centrifuged at 12 000g for 5 min. A 50 μL aliquot of the supernatant was mixed with the same volume of luciferase reagent. Luminance which represents the level of ATP was measured by a microplate reader (Biotek, VT, USA).

Western Blot

Western blotting was conducted as described previously.55 Briefly, BV2 cells were prepared, and 40–60 μg of total protein was loaded on a 12% (w/v) sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel. The separated proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane, and then hybridized with an anti-LAMP1 monoclonal antibody (cat. no. ab208943, Abcam, MA, USA; 1:2000) or anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody (cat. no. ab8226, Abcam, MA, USA; 1:5000) at 4 °C overnight. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were used (cat. no. W4011 or W4021, Promega, CA, USA; 1:5000) for 2 h at RT. Then, the membranes were examined using an ECL detection reagent (Bio-Rad, CA, USA).

Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± standard error (SD). Statistical comparisons were performed by unpaired Student’s t-test, one-way ANOVA, or two-way ANOVA (SPSS 16.0 software or GraphPad Prism 7.00). Post hoc group-wise comparisons were conducted using the Tukey or Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. p-Values of <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. The group size in this study represents independent values. To obtain statistical power above 95% (α = 0.05, power = 0.95) to determine existence of statistically significant differences (P < 0.05), we used a sample size of 5 measurements for the animal experimental group and 3 or 5 measurements for the in vitro experimental group.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (Grant Nos. 2017A030310171, 2016A030313167); National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81872743); Guangzhou Science and Technology Program General project (Grant No. 20180304001); Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province (Grant No. 2017B030314056); and start-up grant from Guangzhou Medical University (Grant No. G2016013).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- Aβ

amyloid-β

- APP/PS1

APPswe/PS1ΔE9

- CD33

Cluster of Differentiation 33

- CNS

central nervous system

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- GWAS

genome-wide association studies

- IL-1β

interleukin-1β

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- NO

nitric oxide

- RT

room temperature

- SD

standard error

- ThS

Thioflavins S

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-α

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsptsci.0c00073.

Co-staining of Iba-1 and ThS positive amyloid plaque; representative costaining of Iba-1, ThS, and DAPI in the hippocampus; AD16 reduces CD22 expression in the brain of APP/PS1 mice and alters lysosomal distribution in BV2 microglial cells; immunoblot assays against LAMP1 protein (PDF)

Author Contributions

W.H., X.Z., and P.S. designed the research studies. P.S., H.Y., Q.X., W., and Y.O. performed the experiments. G.P. contributed essential reagents and instruments. P.S. and X.Z. drafted the manuscript with the assistance of the other authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Ballard C.; Gauthier S.; Corbett A.; Brayne C.; Aarsland D.; Jones E. (2011) Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 377 (9770), 1019–1031. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61349-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings J.; Lee G.; Ritter A.; Zhong K. (2018) Alzheimer’s disease drug development pipeline: 2018. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions 4, 195–214. 10.1016/j.trci.2018.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier S.; Feldman H. H.; Schneider L. S.; Wilcock G. K.; Frisoni G. B.; Hardlund J. H.; Moebius H. J.; Bentham P.; Kook K. A.; Wischik D. J.; Schelter B. O.; Davis C. S.; Bracoud L.; Shamsi K.; Storey J. M.; Harrington C. R.; Wischik C. M. (2016) Efficacy and safety of tau-aggregation inhibitor therapy in patients with mild or moderate Alzheimer’s disease: a randomised, controlled, double-blind, parallel-arm, phase 3 trial. Lancet 388 (10062), 2873–2884. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31275-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honig L. S.; Vellas B.; Woodward M.; Boada M.; Bullock R.; Borrie M.; Hager K.; Andreasen N.; Scarpini E.; Liu-Seifert H.; Case M.; Dean R. A.; Hake A.; Sundell K.; Poole Hoffmann V.; Carlson C.; Khanna R.; Mintun M.; DeMattos R.; Selzler K. J.; Siemers E. (2018) Trial of Solanezumab for Mild Dementia Due to Alzheimer’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 378 (4), 321–330. 10.1056/NEJMoa1705971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Lancet N. (2017) Solanezumab: too late in mild Alzheimer’s disease?. Lancet Neurol. 16 (2), 97. 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30395-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert J.-C.; Heath S.; Even G.; Campion D.; Sleegers K.; Hiltunen M.; Combarros O.; Zelenika D.; Bullido M. J; Tavernier B.; Letenneur L.; Bettens K.; Berr C.; Pasquier F.; Fievet N.; Barberger-Gateau P.; Engelborghs S.; De Deyn P.; Mateo I.; Franck A.; Helisalmi S.; Porcellini E.; Hanon O.; de Pancorbo M. M; Lendon C.; Dufouil C.; Jaillard C.; Leveillard T.; Alvarez V.; Bosco P.; Mancuso M.; Panza F.; Nacmias B.; Bossu P.; Piccardi P.; Annoni G.; Seripa D.; Galimberti D.; Hannequin D.; Licastro F.; Soininen H.; Ritchie K.; Blanche H.; Dartigues J.-F.; Tzourio C.; Gut I.; Van Broeckhoven C.; Alperovitch A.; Lathrop M.; Amouyel P. (2009) Genome-wide association study identifies variants at CLU and CR1 associated with Alzheimer's disease.. Nat. Genet. 41, 1094. 10.1038/ng.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y.-C.; Lee W.-J.; Hwang J.-P.; Wang Y.-F.; Tsai C.-F.; Wang P.-N.; Wang S.-J.; Fuh J.-L. (2014) ABCA7 gene and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in Han Chinese in Taiwan. Neurobiol. Aging 35 (10), 2423.e7–2423.e13. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerreiro R.; Wojtas A.; Bras J.; Carrasquillo M.; Rogaeva E.; Majounie E.; Cruchaga C.; Sassi C.; Kauwe J. S. K.; Younkin S.; Hazrati L.; Collinge J.; Pocock J.; Lashley T.; Williams J.; Lambert J.-C.; Amouyel P.; Goate A.; Rademakers R.; Morgan K.; Powell J.; St. George-Hyslop P.; Singleton A.; Hardy J. (2013) TREM2 Variants in Alzheimer’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 368 (2), 117–127. 10.1056/NEJMoa1211851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calsolaro V.; Edison P. (2016) Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease: Current evidence and future directions. Alzheimer's Dementia 12 (6), 719–732. 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyss-Coray T.; Mucke L. (2002) Inflammation in neurodegenerative disease--a double-edged sword. Neuron 35 (3), 419–32. 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00794-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneka M. T.; Carson M. J.; El Khoury J.; Landreth G. E.; Brosseron F.; Feinstein D. L.; Jacobs A. H.; Wyss-Coray T.; Vitorica J.; Ransohoff R. M.; Herrup K.; Frautschy S. A.; Finsen B.; Brown G. C.; Verkhratsky A.; Yamanaka K.; Koistinaho J.; Latz E.; Halle A.; Petzold G. C.; Town T.; Morgan D.; Shinohara M. L.; Perry V. H.; Holmes C.; Bazan N. G.; Brooks D. J.; Hunot S.; Joseph B.; Deigendesch N.; Garaschuk O.; Boddeke E.; Dinarello C. A.; Breitner J. C.; Cole G. M.; Golenbock D. T.; Kummer M. P. (2015) Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 14 (4), 388–405. 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)70016-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu R.; Shen Q.; Xu P.; Luo J. J.; Tang Y. (2014) Phagocytosis of microglia in the central nervous system diseases. Mol. Neurobiol. 49 (3), 1422–1434. 10.1007/s12035-013-8620-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren J.-L.; Pan J.-S.; Lu Y.-P.; Sun P.; Han J. (2009) Inflammatory signaling and cellular senescence. Cell. Signalling 21 (3), 378–383. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker D. J.; Wijshake T.; Tchkonia T.; LeBrasseur N. K.; Childs B. G.; van de Sluis B.; Kirkland J. L.; van Deursen J. M. (2011) Clearance of p16Ink4a-positive senescent cells delays ageing-associated disorders. Nature 479 (7372), 232–236. 10.1038/nature10600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussian T. J.; Aziz A.; Meyer C. F.; Swenson B. L.; van Deursen J. M.; Baker D. J. (2018) Clearance of senescent glial cells prevents tau-dependent pathology and cognitive decline. Nature 562 (7728), 578–582. 10.1038/s41586-018-0543-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W.; Zhong G.; Fu S.; Xie H.; Chi T.; Li L.; Rao X.; Zeng S.; Xu D.; Wang H.; Sheng G.; Ji X.; Liu X.; Ji X.; Wu D.; Zou L.; Tortorella M.; Zhang K.; Hu W. (2016) Microglia-Based Phenotypic Screening Identifies a Novel Inhibitor of Neuroinflammation Effective in Alzheimer’s Disease Models. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 7 (11), 1499–1507. 10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz L.; Ranaivo H. R.; Roy S. M.; Hu W.; Craft J. M.; McNamara L. K.; Chico L. W.; Van Eldik L. J.; Watterson D. M. (2007) A novel p38α MAPK inhibitor suppresses brain proinflammatory cytokine up-regulation and attenuates synaptic dysfunction and behavioral deficits in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. J. Neuroinflammation 4 (1), 21. 10.1186/1742-2094-4-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou Z.; Kong X.; Sun X.; He X.; Zhang L.; Gong Z.; Huang J.; Xu B.; Long D.; Li J.; Li Q.; Xu L.; Xuan A. (2018) Metformin treatment prevents amyloid plaque deposition and memory impairment in APP/PS1 mice. Brain, Behav., Immun. 69, 351–363. 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Z.; Huang J.; Xu B.; Ou Z.; Zhang L.; Lin X.; Ye X.; Kong X.; Long D.; Sun X.; He X.; Xu L.; Li Q.; Xuan A. (2019) Urolithin A attenuates memory impairment and neuroinflammation in APP/PS1 mice. J. Neuroinflammation 16 (1), 62. 10.1186/s12974-019-1450-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe D. J.; Hardy J. (2016) The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol. Med. 8 (6), 595–608. 10.15252/emmm.201606210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condello C.; Yuan P.; Schain A.; Grutzendler J. (2015) Microglia constitute a barrier that prevents neurotoxic protofibrillar Aβ42 hotspots around plaques. Nat. Commun. 6, 6176–6176. 10.1038/ncomms7176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluvinage J. V.; Haney M. S.; Smith B. A. H.; Sun J.; Iram T.; Bonanno L.; Li L.; Lee D. P.; Morgens D. W.; Yang A. C.; Shuken S. R.; Gate D.; Scott M.; Khatri P.; Luo J.; Bertozzi C. R.; Bassik M. C.; Wyss-Coray T. (2019) CD22 blockade restores homeostatic microglial phagocytosis in ageing brains. Nature 568 (7751), 187–192. 10.1038/s41586-019-1088-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kritsilis M.; V. Rizou S.; Koutsoudaki P.; Evangelou K.; Gorgoulis V.; Papadopoulos D. (2018) Ageing, Cellular Senescence and Neurodegenerative Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19 (10), 2937. 10.3390/ijms19102937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho M. H.; Cho K.; Kang H. J.; Jeon E. Y.; Kim H. S.; Kwon H. J.; Kim H. M.; Kim D. H.; Yoon S. Y. (2014) Autophagy in microglia degrades extracellular beta-amyloid fibrils and regulates the NLRP3 inflammasome. Autophagy 10 (10), 1761–75. 10.4161/auto.29647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baar M. P.; Brandt R. M.C.; Putavet D. A.; Klein J. D.D.; Derks K. W.J.; Bourgeois B. R.M.; Stryeck S.; Rijksen Y.; van Willigenburg H.; Feijtel D. A.; van der Pluijm I.; Essers J.; van Cappellen W. A.; van IJcken W. F.; Houtsmuller A. B.; Pothof J.; de Bruin R. W.F.; Madl T.; Hoeijmakers J. H.J.; Campisi J.; de Keizer P. L.J. (2017) Targeted Apoptosis of Senescent Cells Restores Tissue Homeostasis in Response to Chemotoxicity and Aging. Cell 169 (1), 132–147. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker D. J.; Petersen R. C. (2018) Cellular senescence in brain aging and neurodegenerative diseases: evidence and perspectives. J. Clin. Invest. 128 (4), 1208–1216. 10.1172/JCI95145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong Y. C.; Kim S.; Peng W.; Krainc D. (2019) Regulation and Function of Mitochondria–Lysosome Membrane Contact Sites in Cellular Homeostasis. Trends Cell Biol. 29 (6), 500–513. 10.1016/j.tcb.2019.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pu J.; Guardia C. M.; Keren-Kaplan T.; Bonifacino J. S. (2016) Mechanisms and functions of lysosome positioning. J. Cell Sci. 129 (23), 4329–4339. 10.1242/jcs.196287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erie C.; Sacino M.; Houle L.; Lu M. L.; Wei J. (2015) Altered lysosomal positioning affects lysosomal functions in a cellular model of Huntington’s disease. European journal of neuroscience 42 (3), 1941–1951. 10.1111/ejn.12957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uusi-Rauva K.; Kyttälä A.; van der Kant R.; Vesa J.; Tanhuanpää K.; Neefjes J.; Olkkonen V. M.; Jalanko A. (2012) Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis protein CLN3 interacts with motor proteins and modifies location of late endosomal compartments. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 69 (12), 2075–2089. 10.1007/s00018-011-0913-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.; Rydzewski N.; Hider A.; Zhang X.; Yang J.; Wang W.; Gao Q.; Cheng X.; Xu H. (2016) A molecular mechanism to regulate lysosome motility for lysosome positioning and tubulation. Nat. Cell Biol. 18 (4), 404–417. 10.1038/ncb3324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloatti A.; Kotsias F.; Pauwels A.-M.; Carpier J.-M.; Jouve M.; Timmerman E.; Pace L.; Vargas P.; Maurin M.; Gehrmann U.; Joannas L.; Vivar O. I.; Lennon-Dumenil A.-M.; Savina A.; Gevaert K.; Beyaert R.; Hoffmann E.; Amigorena S. (2015) Toll-like Receptor 4 Engagement on Dendritic Cells Restrains Phago-Lysosome Fusion and Promotes Cross-Presentation of Antigens. Immunity 43 (6), 1087–1100. 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korolchuk V. I.; Saiki S.; Lichtenberg M.; Siddiqi F. H.; Roberts E. A.; Imarisio S.; Jahreiss L.; Sarkar S.; Futter M.; Menzies F. M.; O’Kane C. J.; Deretic V.; Rubinsztein D. C. (2011) Lysosomal positioning coordinates cellular nutrient responses. Nat. Cell Biol. 13 (4), 453–460. 10.1038/ncb2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. Y. D.; Landreth G. E. (2010) The role of microglia in amyloid clearance from the AD brain. Journal of neural transmission (Vienna, Austria: 1996) 117 (8), 949–960. 10.1007/s00702-010-0433-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baik S. H.; Kang S.; Son S. M.; Mook-Jung I. (2016) Microglia contributes to plaque growth by cell death due to uptake of amyloid beta in the brain of Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Glia 64 (12), 2274–2290. 10.1002/glia.23074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.; Griciuc A.; Hudry E.; Wan Y.; Quinti L.; Ward J.; Forte A. M.; Shen X.; Ran C.; Elmaleh D. R.; Tanzi R. E. (2018) Cromolyn Reduces Levels of the Alzheimer’s Disease-Associated Amyloid β-Protein by Promoting Microglial Phagocytosis. Sci. Rep. 8 (1), 1144. 10.1038/s41598-018-19641-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan R.-Y.; Ma J.; Kong X.-X.; Wang X.-F.; Li S.-S.; Qi X.-L.; Yan Y.-H.; Cheng J.; Liu Q.; Jin W.; Tan C.-H.; Yuan Z. (2019) Sodium rutin ameliorates Alzheimer’s disease–like pathology by enhancing microglial amyloid-β clearance. Science Advances 5 (2), eaau6328. 10.1126/sciadv.aau6328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park M. H.; Lee M.; Nam G.; Kim M.; Kang J.; Choi B. J.; Jeong M. S.; Park K. H.; Han W. H.; Tak E.; Kim M. S.; Lee J.; Lin Y.; Lee Y.-H.; Song I.-S.; Choi M.-K.; Lee J.-Y.; Jin H. K.; Bae J.-s.; Lim M. H. (2019) N,N′-Diacetyl-p-phenylenediamine restores microglial phagocytosis and improves cognitive defects in Alzheimer’s disease transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 116 (47), 23426. 10.1073/pnas.1916318116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman S. E.; Allison E. K.; El Khoury J. (2008) Microglial dysfunction and defective beta-amyloid clearance pathways in aging Alzheimer’s disease mice. J. Neurosci. 28 (33), 8354–60. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0616-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musi N.; Valentine J. M.; Sickora K. R.; Baeuerle E.; Thompson C. S.; Shen Q.; Orr M. E. (2018) Tau protein aggregation is associated with cellular senescence in the brain. Aging Cell 17 (6), e12840. 10.1111/acel.12840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanary B. E.; Sammons N. W.; Nguyen C.; Walker D.; Streit W. J. (2007) Evidence That Aging And Amyloid Promote Microglial Cell Senescence. Rejuvenation Res. 10 (1), 61–74. 10.1089/rej.2006.9096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njie E. G.; Boelen E.; Stassen F. R.; Steinbusch H. W.; Borchelt D. R.; Streit W. J. (2012) Ex vivo cultures of microglia from young and aged rodent brain reveal age-related changes in microglial function. Neurobiol. Aging 33 (1), 195 e1–12. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra A.; Gottfried-Blackmore A. C.; McEwen B. S.; Bulloch K. (2007) Microglia derived from aging mice exhibit an altered inflammatory profile. Glia 55 (4), 412–424. 10.1002/glia.20468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada M.; Sawada H.; Nagatsu T. (2008) Neurodegener. Dis. 5, 254–6. 10.1159/000113717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X.; Feng G.; Xing J.; Shen B.; Tan W.; Huang D.; Lu X.; Tao T.; Zhang J.; Li L.; Gu Z. (2014) Repeated lipopolysaccharide stimulation promotes cellular senescence in human dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs). Cell Tissue Res. 356 (2), 369–380. 10.1007/s00441-014-1799-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P.; Kishimoto Y.; Grammatikakis I.; Gottimukkala K.; Cutler R. G.; Zhang S.; Abdelmohsen K.; Bohr V. A.; Misra Sen J.; Gorospe M.; Mattson M. P. (2019) Senolytic therapy alleviates Aβ-associated oligodendrocyte progenitor cell senescence and cognitive deficits in an Alzheimer’s disease model. Nat. Neurosci. 22 (5), 719–728. 10.1038/s41593-019-0372-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X.; Zhang T.; Liu H.; Mi Y.; Gou X. (2020) Astrocyte Senescence and Alzheimer’s Disease: A Review. Front. Aging Neurosci. 12, 148. 10.3389/fnagi.2020.00148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia M.-L.; Xie X.-H.; Ding J.-H.; Du R.-H.; Hu G. (2020) Astragaloside IV inhibits astrocyte senescence: implication in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neuroinflammation 17 (1), 105. 10.1186/s12974-020-01791-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe D. M.; Lee J.-H.; Kumar A.; Lee S.; Orenstein S. J.; Nixon R. A. (2013) Autophagy failure in Alzheimer’s disease and the role of defective lysosomal acidification. European journal of neuroscience 37 (12), 1949–1961. 10.1111/ejn.12169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Q.; Yan P.; Ma X.; Liu H.; Perez R.; Zhu A.; Gonzales E.; Burchett J. M.; Schuler D. R.; Cirrito J. R.; Diwan A.; Lee J.-M. (2014) Enhancing astrocytic lysosome biogenesis facilitates Aβ clearance and attenuates amyloid plaque pathogenesis. J. Neurosci. 34 (29), 9607–9620. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3788-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H. T.; Park J. T.; Choi K.; Kim Y.; Choi H. J. C.; Jung C. W.; Lee Y. S.; Park S. C. (2017) Chemical screening identifies ATM as a target for alleviating senescence. Nat. Chem. Biol. 13 (6), 616–623. 10.1038/nchembio.2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y.; Zheng D.; Peng S.; Lin D.; Jing X.; Zeng Z.; Chen Y.; Huang K.; Xie Y.; Zhou T.; Tao E. (2020) Rifampicin attenuates rotenone-treated microglia inflammation via improving lysosomal function. Toxicol. In Vitro 63, 104690. 10.1016/j.tiv.2019.104690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.; Fei Z.; Ren J.; Sun R.; Liu Z.; Sheng Z.; Wang L.; Sun X.; Yu J.; Wang Z.; Fei J. (2008) Functional imaging of interleukin 1 beta expression in inflammatory process using bioluminescence imaging in transgenic mice. BMC Immunol. 9, 49–49. 10.1186/1471-2172-9-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onos K. D.; Uyar A.; Keezer K. J.; Jackson H. M.; Preuss C.; Acklin C. J.; O’Rourke R.; Buchanan R.; Cossette T. L.; Sukoff Rizzo S. J.; Soto I.; Carter G. W.; Howell G. R. (2019) Enhancing face validity of mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease with natural genetic variation. PLoS Genet. 15 (5), e1008155. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun P.; Chen J.-y.; Li J.; Sun M.-r.; Mo W.-c.; Liu K.-l.; Meng Y.-y.; Liu Y.; Wang F.; He R.-q.; Hua Q. (2013) The protective effect of geniposide on human neuroblastoma cells in the presence of formaldehyde. BMC Complementary Altern. Med. 13 (1), 152. 10.1186/1472-6882-13-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.