Abstract

Background

In marine invertebrate life cycles, which often consist of planktonic larval and benthonic adult stages, settlement of the free-swimming larva to the sea floor in response to environmental cues is a key life cycle transition. Settlement is regulated by a specialized sensory–neurosecretory system, the larval apical organ. The neuroendocrine mechanisms through which the apical organ transduces environmental cues into behavioral responses during settlement are not fully understood yet.

Results

In this study, a total of 54 neuropeptide precursors (pNPs) were identified in the Urechis unicinctus larva and adult transcriptome databases using local BLAST and NpSearch prediction, of which 10 pNPs belonging to the ancient eumetazoa, 24 pNPs belonging to the ancient bilaterian, 3 pNPs belonging to the ancient protostome, 9 pNPs exclusive in lophotrochozoa, 3 pNPs exclusive in annelid, and 5 pNPs only found in U. unicinctus. Furthermore, four pNPs (MIP, FRWamide, FxFamide and FILamide) which may be associated with the settlement and metamorphosis of U. unicinctus larvae were analysed by qRT-PCR. Whole-mount in situ hybridization results showed that all the four pNPs were expressed in the region of the apical organ of the larva, and the positive signals were also detected in the ciliary band and abdomen chaetae. We speculated that these pNPs may regulate the movement of larval cilia and chaeta by sensing external attachment signals.

Conclusions

This study represents the first comprehensive identification of neuropeptides in Echiura, and would contribute to a complete understanding on the roles of various neuropeptides in larval settlement of most marine benthonic invertebrates.

Keywords: Urechis unicinctus, Echiura, Neuropeptide precursor, Larval settlement

Background

Most marine benthic invertebrates have planktonic larvae during their life cycle. After going through a pelagic period, these planktonic larvae settle to the bottom and metamorphose into benthonic individuals (crawling, attaching, fixing and burrowing) [1, 2]. The larval settlement is the key event for their development and survival, which commonly includes the cessation of swimming and the appearance of substrate exploratory behavior [3–6]. This is a complex process determined by the interaction of biotic and abiotic factors at different temporal and spatial scale [7, 8]. The apical organ, a cluster of sensory neurons at the anterior of the larva in diverse groups as phoronids, polychaetes and chitons, has been implicated to be the site of perception cues for settlement and metamorphosis [9, 10]. Researchers found that neuropeptides expressed in chemosensory–neurosecretory cells of the apical organ can innervate ciliary bands, and suggested that they may play a role in the regulation of larval locomotion [11–14], which contribute to the larval settlement behavior [9].

Neuropeptides are considered to be the oldest neuronal signaling molecules in metazoans [15], and participate in the control of neural circuits and physiology [16–18]. They are generated from inactive precursor proteins by proteolytic cleavage and further modification such as C-terminal alpha-amidation and N-terminal pyroglutamination [19, 20], and then released into the hemolymph as hormones or the synapses as nerotransmitters to regulate the physiological activities of target cells [21]. Studies on the marine invertebrate larval neuropeptide systems have mainly been focused on lophotrochozoan including Mollusca and Annelida. For example, in mollusca, they mainly focus on larval development, larval feeding behavior, larval muscle innervation and muscular contractions [22–25]. In annelid Platynereis, neuropeptides have been indicated to involve in the ciliary beating, some neuropeptides (RYa, FVMa, DLa, FMRFa, FVa, LYa, YFa SPY and L11) for the larval upward swimming and others (FLa and WLD) for the downward swimming [21]. Furthermore, MIPs (myoinhibitory peptide) have been experimentally verified to play a role in regulating the larval settlement of marine annelid [9]. So far, other neuropeptides related to the larval settlement remain to be explored.

Urechis unicinctus is a representative species in Echirua inhabiting the U-shaped burrows in the coastal mud flats, and is also a commercial echiuran worm in China, Japan and Korea. The worm has a typical free-swimming trochophore larva beginning with the early trochophore stage (ET, 2 days post-fertilization; dpf) and the planktonic larva settles to the bottom during the segmentation larva stage (SL, 35 dpf; also called competent larva, CL), and then burrows the sediment and metamorphoses into the benthic worm (worm-shaped larva, WL, 42 dpf). Previous studies indicated that the SL stage larvae will delay metamorphosis and their mortality rate will increase if they do not find the adaptive substrate [3, 26, 27]. In this study, to provide a basic profile of the neuropeptide precursors for investigating the role of neuropeptides in U. unicinctus larval settlement, we screened the neuropeptide precursors potentially involved in the larval settlement from the U. unicinctus larval and adult transcriptomes. Furthermore, expression characteristics of the candidate genes were validated by qRT-PCR and whole-mount in situ hybridization. To map the candidate genes to the nerve cells at the special sites, nervous system in U. unicinctus larvae was analyzed using the fluorescence immunohistochemistry. The aim of this study was to identify neuropeptide precursors potentially involved in the larval settlement in the U. unicinctus and to provide new insights in larval settlement of marine benthic invertebrates.

Results and discussion

Overview of the neuropeptide precursors in U. unicinctus

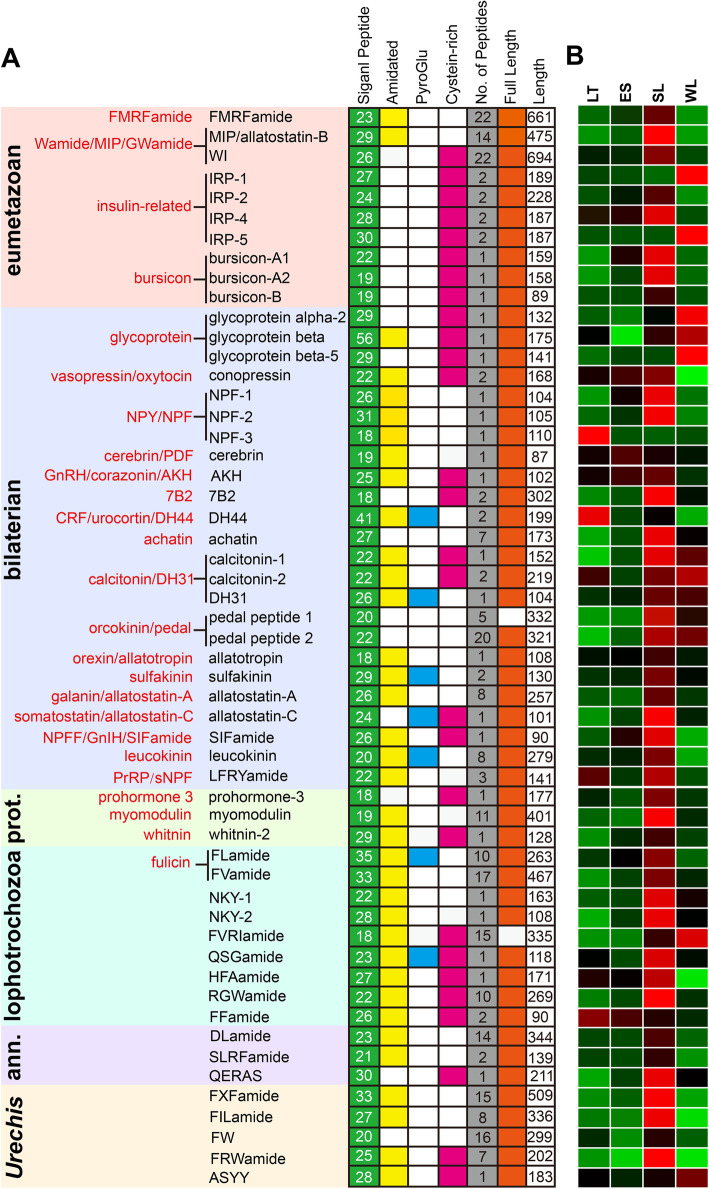

We performed BLAST search and NpSearch prediction to screen the neuropeptide precursors in the transcriptomes of U. unicinctus. A total of 54 neuropeptide precursors (pNPs) were identified, 7 from BLAST search, 5 from NpSearch prediction, and 42 from both methodologies (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table S2). Among them, 49 pNPs had been reported in other species, and the remaining 5 pNPs were first identified in U. unicinctus and we named them FxFamide, FILamide, FW, FRWamide and ASYY according to their conserved amino acid residues. In the U. unicinctus transcriptomes, most neuropeptide precursor sequences contained the full-length open reading frame (ORF) with a signal peptide (SP), except pedal peptide 1 and FVRIamide. The sequence characteristics of U. unicinctus neuropeptide precursors for the SP presence, the conserved peptide motifs and other hallmarks of bioactive peptides, e.g. amidation C-terminal Gly, Cys-containing stretches, mono- or dibasic cleavage sites were summarized in Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. S1.

Fig. 1.

Summary of the identified neuropeptide precursors from U. unicinctus larval and adult transcriptomes. a pNPs are classified based on their phylogenetic distribution into eumetazoan, bilaterian, protostome (prot.), lophotrochozoan, annelid (ann.) and Urechis-specific. Previously established metazoan neuropeptide families are indicated in red [28]. b Hierarchical clustering of the neuropeptide precursor genes in U. unicinctus larval transcriptomes [29]. LT, late-trochophore (25 dpf, pelagic larva); ES, early- segmented larva (32 dpf, pelagic larva); SL, segmented larva (35 dpf, competent larva); WL, worm-shaped larva (42 dpf, benthic larva). Colors represent the gene expression levels from green (low), black (middle) to red (high)

Due to the inherent difficulties of analyzing highly diverse and repetitive pNPs, the relationships among different families are often elusive. Therefore, Jékely [28] and Conzelmann [30], using similarity-based clustering and sensitive similarity searches, obtained a global view of metazoan pNP diversity and evolution based on a curated dataset of 6225 pNPs from 10 phyla. This approach was also useful for analyzing the phylogenetic distribution of U. unicinctus pNPs and we classified the pNP families using the same methodology. The results showed that ten pNPs in U. unicinctus were categorized as the ancient eumetazoan families (Fig. 1a), which are the repertoire neuropeptides with the short amidated peptides, such as R [F/Y] amide, Wamide, insulin-related peptide and the glycoprotein hormones [28, 31, 32]. Then, twenty-four pNPs in U. unicinctus were categorized as the ancient bilaterian families (Fig. 1a), which belong to 17 neuropeptide families [28]. Three members of the ancient protostome neuropeptide precursor families were present in U. unicinctus, including prohormone-3, myomodulin, and whitnin-2 (Fig. 1a). Moreover, we identified nine pNPs in U. unicinctus (Fig. 1a), which were proposed to be the lophotrochozoan-specific families [30]. Three pNPs in U. unicinctus had recognizable orthologs only in annelids, including DLamide, SLRFamide and QERAS (Fig. 1a). In addition, five pNPs did not have recognizable orthologs outside Urechis, and were temporarily classified as neuropeptides unique to U. unicinctus, including the FxFamide, FILamide, FW, FRWamide and ASYY (Fig. 1a).

Traditionally Echiura was ranked as a phylum, but recent studies, especially on molecular phylogenetic analysis [33] and morphological observation [34, 35], have generated an increasing body of evidence that they actually are derived annelids and provide strong support for a sister group relationship between Echiura and Capitellidae. This is consistent with our study in which we find three Annelid-specific pNPs were presented in U. unicinctus.

Screen of the neuropeptide precursors potentially involving in the larval settlement

We performed a hierarchical clustering of the neuropeptide precursors based on their stage-specific expression (FPKM values) from the U. unicinctus transcriptomes (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. S2). The results showed that most of the neuropeptide precursors were expressed at multiple stages, and the expression levels were significantly different. We found when the larvae developed from LT to ES, a process which the larvae initially transited from upper to middle layer in the water column, expression levels of NPF-3 and DH44 decreased significantly (p < 0.05), while that of bursicon-A2 and NPF-1 was significantly increased (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. S2). During the development progress from ES to SL, a period that the larvae move from the middle to the bottom of water layer, eleven pNP genes (MIP, bursicon-A2, NPF-2, RGWamide, 7B2, pedal peptide 1, myomodulin, FVRIamide, FxFamide, FILamide and FRWamide) were significantly up-regulated (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. S2). However, eight genes (except 7B2, pedal peptide 1 and FVRIamide) among the eleven pNPs above were again down-regulated (p < 0.05) when the larvae developed from SL to WL, which is the period that the larvae begin to explore the suitable substrate and finally became benthic larvae (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. S2). As MIP have been confirmed to regulate larvae settlement behavior [9], we speculated preliminarily the eight pNPs with similar expression pattern were considered to be most likely pNPs involved in the regulation of larval settlement and metamorphosis in U. unicinctus.

Sequence characteristics of the selected pNPs that may be involved in the regulation of larval settlement in U. unicinctus

Four interesting pNPs, including previously reported MIP [9] and three Uu-specific pNPs (FxFamide, FILamide and FRWamide), were selected for further analysis.

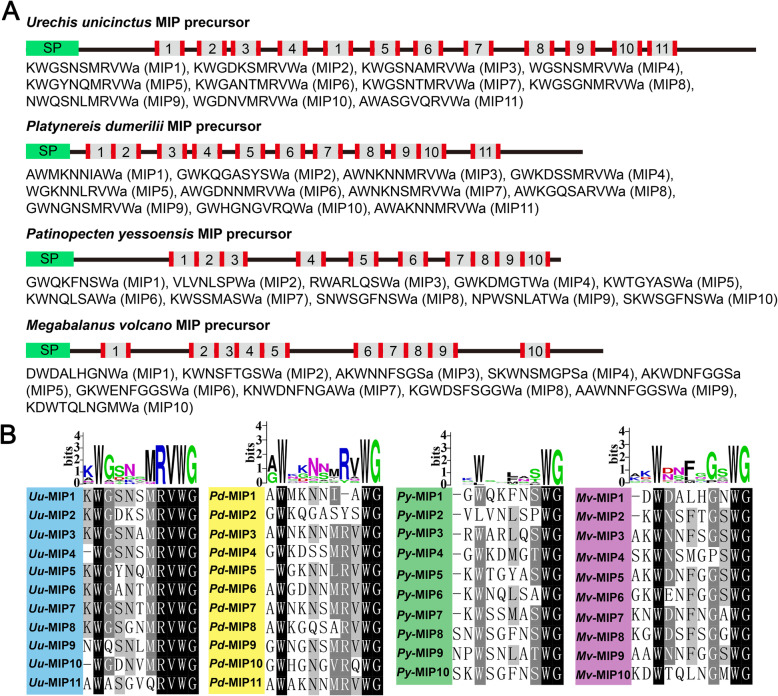

MIPs (Myoinhibitory peptides) are pleiotropic neuropeptides first described in insects as inhibitors of muscle contractions [18, 36, 37]. In some insect species, MIPs modulate juvenile hormone synthesis and reduce food intake, and they are also referred to as allatostatin-B or WWamide [38–41]. In Platynereis the MIPs have been confirmed to regulate larvae settlement behavior [9] and feeding behavior [42]. They are characterized by a conserved domain containing two Trp residues which are usually separated by five to eight amino acid residues in insects, molluscs and annelids [43–45]. In U. unicinctus transcriptomes, we identified a neuropeptide precursor which is an orthologue of arthropod MIP (Fig. 2). The Uu-MIP precursor contains 11 mature peptides, the number of mature peptides in U. unicinctus is the same as that of the annelid Platynereis dumerilii, while differs from the mollusc Patinopecten yessoensis and the arthropod Megabalanus volcano which have 10 mature peptides (Fig. 2a). Sequence alignment of the bioactive peptides revealed that the sequence similarity among the different mature MIPs in U. unicinctus was higher than that in P. dumerilii, P. yessoensis and M. volcano (Fig. 2b). Moreover, the MRVWamide motif in C-terminal of the mature MIPs is present in U. unicinctus and P. dumerilii, but not in P. yessoensis and M. volcano (Fig. 2b). The above results show that the characteristics of the MIP precursor sequence of U. unicinctus are closer to that of P. dumerilii, which is consistent with the classic species evolution.

Fig. 2.

Schematics of MIP precursors and alignment of potential bioactive peptides. a Schematics of MIP precursor proteins for the echiuran Urechis unicinctus (GenBank: MT162087), annelid Platynereis dumerilii (GenBank: JX513877), mollusc Patinopecten yessoensis (GenBank: MH045202) and arthropod Megabalanus volcano (GenBank: MF579246). N-terminal signal peptides are showed in green, the predicted peptides in gray and the basic cleavage sites on the flanked of the predicted peptides in red. The serial number in each MIP precursor represents the types of the predicted mature MIPs. b Multiple alignments and peptide logos of the predicted mature MIPs from U. unicinctus (Uu), P. dumerilii (Pd), P. yessoensis (Py) and M. volcano (Mv)

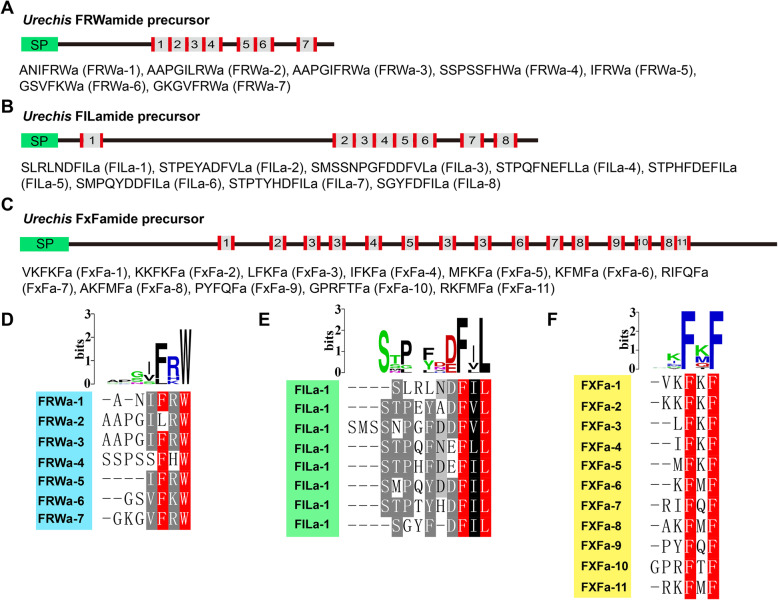

In this study, five potential neuropeptide precursors were for the first time identified in U. unicinctus (Fig. 1a), and three of them (FRWamide, FILamide and FxFamide) were predicted to play a role in regulating U. unicinctus larvae settlement based on the significant differences in mRNA level from the segmented larvae to worm-shaped larvae (Fig. 1b). FRWamide precursor is comprised of 202 amino acids which contains a 25-residue signal peptide and 7 copies of neuropeptides with FRWamide motif in the C-terminal (Fig. 3a and d). FILamide precursor is comprised of 336 amino acids which contains a 27-residue signal peptide and 8 copies of neuropeptides with FILamide motif in the C-terminal (Fig. 3b and e). FxFamide precursor is comprised of 509 amino acids which contains a 33-residue signal peptide and 15 copies of neuropeptides with FxFamide motif in the C-terminal (Fig. 3c and f). These newly discovered neuropeptide precursors enrich the intension of neuropeptide composition.

Fig. 3.

FRWamide, FILamide and FxFamide neuropeptide precursors. a, b and c Schematics of FRWamide, FILamide and FxFamide precursor proteins in U. unicinctus. N-terminal signal peptides (green) and the predicted peptides (gray) flanked by basic cleavage sites (red) are shown. The predicted mature FRWamide, FILamide and FxFamide sequences and their numbering as used in the text are listed. d, e and f Multiple alignments and peptide logos of the predicted mature FRWamide (GenBank: MT162138), FILamide (GenBank: MT162136) and FxFamide (GenBank: MT162135)

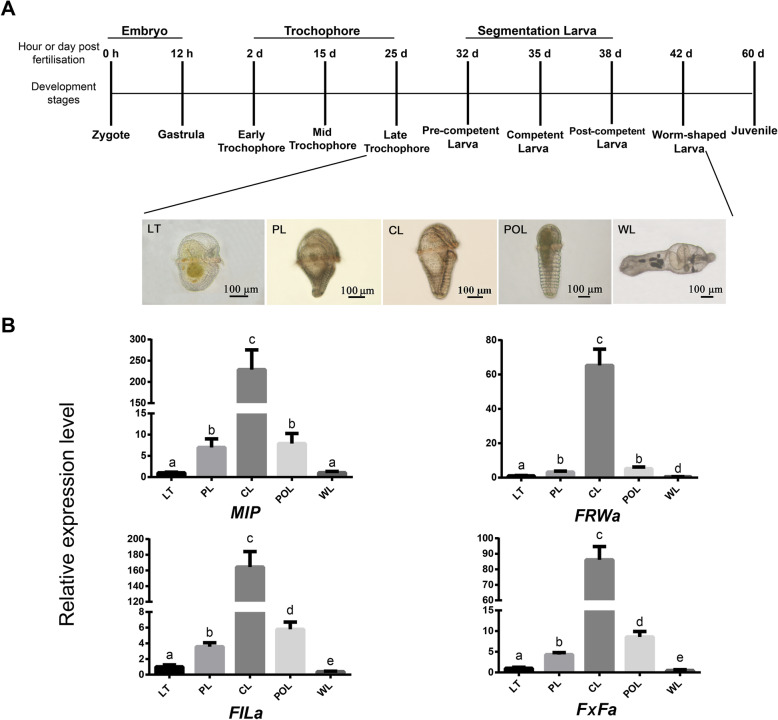

Spatio-temporal expression of the selected pNPs during the larval settlement

To verify the expression of the four pNP transcripts (MIP, FILamide, FxFamide and FRWamide), U. unicinctus larvae including late-trochophore (LT), pre-competent larva (PL), competent larva (CL), post-competent larva (POL) and worm-shaped larva (WL) were employed for qRT-PCR analysis (Fig. 4a). The results showed that the mRNA levels of the four pNP genes increased through larval development, with the highest expression in CL, and then significant decrease in POL and WL (Fig. 4b). These results are consistent with the transcriptome data (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. S2). During the developmental progression from LT to CL, the U. unicinctus larvae move from the upper to the middle layer in water, and gradually acquire the ability to explore a suitable substrate in CL, finally become benthic larvae in WL. Thus, we suggested that these four genes may be involved in the biological activities of the larvae exploring the substrate for settlement in U. unicinctus.

Fig. 4.

The relative expression levels of the pNP genes in U. unicinctus larvae during the settlement. a, A time course of U. unicinctus development indicating qRT-PCR sampling strategy employed in this study. b, the relative expression levels of the pNP genes. LT, late-trochophore (25 dpf, pelagic larva); PL, pre-competent larva (32 dpf, correspond to ES in transcriptome data); CL, competent larva (35 dpf, correspond to SL in transcriptome data); POL, post-competent larva (38 dpf); WL, worm-shaped larva (42 dpf, benthic larva). Data are indicated as mean ± SD from triplicate experiments and analyzed using One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD test. Different letters indicate significant difference between different developmental stages (p < 0.05)

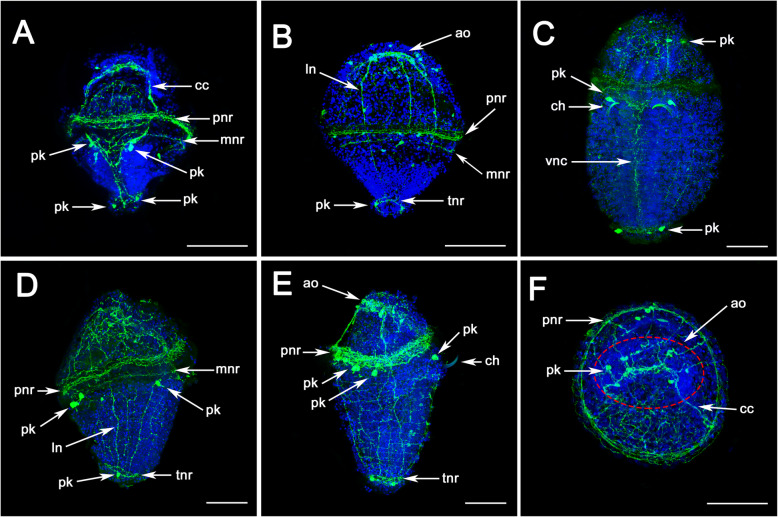

To map the expression of these pNPs (MIP, FxFamide, FILamide and FRWamide) to nerve cells at the special sites, nervous system in U. unicinctus larvae was analyzed using fluorescence immunohistochemistry with an anti-5HT antibody (Fig. 5). The results showed that, in trochophore up to an age of approximately 15 days, only a few structures of the nervous system are labeled with antibodies against 5-HT. In the episphere of the larvae, the circumoesophageal connectives (CC) and two nerve rings innervating the prototroch and metatroch are visible (Fig. 5a). In the hyposphere of the larva, two longitudinal nerves (LN) merge after a short distance forming a median nerve named ventral nerve cord (VNC). Two pairs of perikarya are discernible in the anterior region, directly behind the slit-shaped mouth opening (Fig. 5a, c) and on the telotroch nerve ring (Fig. 5a, b, c). In dorsal view of the larva, 3–4 LNs can be seen in the episphere which connect to the prototroch and metatroch nerve rings (Fig. 5b). As development proceeds up to the competent larva, in which the anterior chaetae have already been formed, the paired longitudinal nerve tracts of the VNC are fused in the ventral midline (Fig. 5c). In addition, the metatroch nerve ring is disappeared and two labeled perikaryas are visible on the dorsal side of the larva just under the prototroch nerve ring (Fig. 5d, e). The apical organ of the larva is shown in Fig. 5f. Fluorescence immunohistochemistry were also used to study the development of the nervous system in various other Echiuran species, such as Bonellia viridis [46, 47] and Urechis caupo [34]. Our results are consistent with those previous studies which have proven to be informative in the study of neurogenesis in neuronal structures of Echiurans. Besides, we revealed several previously unreported details — eight nerve fibers and six large labeled perikaryas are visible in the apical organ in Echiuran worm (Fig. 5f), which is similar to that reported in P. dumerilii [9, 21, 30, 48] and especially in Capitella teleta [48].

Fig. 5.

The nervous system in U. unicinctus larvae detected by Immunofluorescence technique with 5-HT antibody. a-b correspond to late-trochophore (LT) of U. unicinctus. c-f correspond to competent larva (CL); a and c, ventral view; b and e, dorsal view; d, lateral view; f, anterior view of CL. ao, apical organ; cc, circumoesophageal connectives; ch, chaeta; ln, longitudinal nerve fibre; mnr, metatroch nerve ring; pk, perikarya; pnr, prototroch nerve ring; tnr, telotroch nerve ring; vnc, ventral nerve cord. Scale bars: 200 μm

Next, location of four pNP mRNAs including MIP, FxFamide, FILamide and FRWamide were detected by Whole-mount mRNA in situ hybridization (WISH) (Fig. 6 and Figure S3). The results showed that a positive MIP signal was first observed in the central region of the episphere in the early-trochophore larva (Fig. 6a) which is similar to that of the apical organ in C. teleta and P. dumerilii [9, 48]. As the development proceeds, four positive cells are exclusively located in the apical organ of the late-trochophore larva (Fig. 6b). Until the competent larvae, the obvious positive signals were located in four regions, including the apical organ (the 4–6 cells), above the abdomen chaetae (the two cells), the prototroch in the dorsal side of the larvae (the two cells) and the both side of the telotroch (the two cells) (Fig. 6c). The expression patterns of FRWamide, FxFamide and FILamide were similar to that of MIP (Fig. 6), except no visible FRWamide positive signal was observed in U. unicinctus early-trochophore (Fig. 6d), in competent larvae FxFamide was detected only in apical organ (the six stained cells) and above the abdomen chaetae (the two stained cells) (Fig. 6i), while the positive signal of FILamide in the competent larva was only in the four positive cells of apical organ (Fig. 6l). Since the WISH experiment was observed after being sealed with resin, it was difficult to observe the apical view of the larva.

Fig. 6.

The expression patterns of MIP, FRWa, FxFa and FILa in U. unicinctus larvae detected by whole-mount in situ hybridization. a, d, g and j correspond to early-trochophore (2 dpf, pelagic larva); b, e, h and k correspond to late-trochophore (25 dpf, correspond to LT in transcriptome data, pelagic larva) and (c, f, i and l) correspond to competent larva (35 dpf, correspond to SL in transcriptome data). The asterisk indicates the location of the larvae mouth; b, dorsal view; e and k, ventral view; the remaining panels are all lateral views. Scale bars: 200 μm. Negative controls with sense probe can be found in Supplementary Figure S3

In many marine invertebrates the transition from free-swimming larvae to bottom-dwelling juveniles is regulated by neuroendocrine signals (including neuropeptides and hormones) [49–51]. In diverse ciliated marine larvae, the apical organ, has been implicated in the detection of cues for the initiation of larval settlement [9, 10, 52–55]. Previous studies suggest that several neuropeptides expressed in distinct sensory neurons (apical organ) innervate locomotor cilia, which contribute to the larvae swimming depth [9, 21]. The alternation of active upward swimming and passive sinking, together with swimming speed and sinking rate, is thought to determine vertical distribution in the water [56]. In Platynereis, neuropeptides including RYa, FVMa, DLa, FMRFa, FVa, LYa, YFa, FLa, MIP, GWa et al. can alter ciliary beat frequency and the rate of calcium-evoked ciliary arrests [9, 21], which eventually may be involved in regulating the larvae settlement. In our study, the MIP and FRWamide were detected in the dorsal side of the prototroch nerve ring and the both side of the telotroch nerve ring (Fig. 6c, f), indicating that they may play a role in U. unicinctus ciliary beating and eventually cause the larvae sinking to the bottom. MIP is the only neuropeptide that has been shown to be involved in larval settlement in Platynereis [9], which is expressed in chemosensory–neurosecretory cells in the annelid larval apical organ. The researchers found that synthetic MIPs can induce the settlement of P. dumerilii larvae, and they demonstrate by morpholino-mediated knockdown that MIP signals via a G protein-coupled receptor to trigger settlement [9]. These results reveal a role for a conserved MIP receptor–ligand pair in regulating marine annelid settlement. In this study, we revealed that MIP, FxFamide, FILamide and FRWamide all localized in the region of the apical organ (Fig. 6), like MIPs expression pattern in P. dumerilii, indicating that these neuropeptides may also be involved in triggering larval settlement. In addition, the expressions of the MIP, FRWamide and FxFamide were also detected at base of the abdomen chaetae (Fig. 6c, f and i). The chaetae are important in locomotion, stabilization during peristalsis, and sensing the environment in annelids [57], and have been implicated in assisting movement and stabilizing body segments within the tube for worms living in burrows or tubes [58, 59]. However, in sediment-dwellers they contact the inside walls of tubes or burrows. The cantilever nature of capillary chaetae and their astounding breadth of flexural stiffness suggest that they could be very effective at transmitting specific mechanical information about their surroundings to the body of the worm [34, 57]. Therefore, we propose that MIP, FRWamide and FxFamide located in base of the abdomen chaetae may help U. unicinctus larvae crawl on the sediment surface or explore the bottom and eventually contribute to larval settlement. Meanwhile, there are also some limitations to this study which need to be acknowledged. Firstly, this study only uses transcriptomic data to identify neuropeptides, therefore these predicted pNPs have not been confirmed by mass spectrometry to show that they are definitely released as signaling peptides in the worm. Secondly, we only used WISH technology to explore the location of the pNP genes at the mRNA level. Therefore, some issues including mass spectrometry, immunohistochemistry, western blot and other functional studies remained to be investigated in the future.

Conclusions

In this study, we identified 54 pNP genes in U. unicinctus larvae and adult transcriptome databases based on BLAST and NpSearch prediction, and suggested that the neuropeptide system of U. unicinctus is very close to that of annelids according to their phylogenetic distribution. Based on the expression data of pNP genes in the transcriptome of U. unicinctus larvae, four pNPs that may be associated with larval settlement were selected to further investigation. qRT-PCR results showed that the four pNPs were indeed highly expressed in competent larvae. WISH results indicated all the four pNPs were expressed in the region of the apical organ of the larva, and the positive signals were also detected in the ciliary bands and abdomen chaetae. These results imply that the four pNPs may be involved in sensing settlement signals and regulating larval ciliary locomotor and the movement of chaeta, and eventually may play an important role in the settlement of U. unicinctus larvae. Our findings provide some basic data for investigate the complex regulatory mechanisms in larval settlement of marine benthic invertebrates.

Methods

Animals and sampling

Adult U. unicinctus were obtained from Jiutian aquatic products market in Zhifu District of Yantai, China. Sperm and ova were obtained by dissecting the nephridia (gonaduct) of male and female, respectively. Artificial insemination was conducted through mixing the sperm and ova with a ratio of 10: 1 in filtered sea water (FSW). The fertilized eggs were reared in FSW (17 °C, pH 7.7, and salinity 30 PSU), and the hatched larvae were fed with single-cell algae (Isochrysis galbana, Chlorella vulgaris and Chaetoceros muelleri). The larvae at different stages were sampled and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 h at 4 °C, and then dehydrated with serial methanol (25, 50, 75 and 100%) and stored in 100% methanol at − 30 °C for immunofluorescent histochemistry and whole-mount in situ hybridization analysis. The larvae from five developmental stages, late-trochophore (LT, 25 dpf), pre-competent larva (PL, 32 dpf) correspond to early-segmented larva (ES), competent larva (CL, 35 dpf) correspond to segmented larva (SL) which is the fully developed larvae prior to settlement and metamorphosis [26], post-competent larva (POL, 38 dpf) correspond to late-segmented larva (LS), and worm-shaped larva (WL, 42 dpf) were collected (Fig. 4a), frozen with liquid nitrogen immediately and then stored at − 80 °C, respectively for total RNA extraction. Three biological replicates from each developmental stage were prepared.

Identification, classification and sequence alignment of neuropeptide precursors

Data from U. unicinctus larval transcriptomes [29, 60] and adult transcriptome [61] were used in this study. To search for transcripts encoding putative neuropeptides or peptide hormone precursor proteins in U. unicinctus, the homologous sequences previously identified in annelids (Platynereis dumerilii [30], Capitella capitate [44] and Helobdella robusta [44]), molluscs (Patinopecten yessoensis [45], Pinctata fucata [62], Lottia gigantea [63], Crassostrea gigas [62] and Deroceras reticulatum [64]) and echinoderms (Asterias rubens [65], Ophionotus Victoria [66], Strongylocentrotus purpuratus [67] and Apostichopus japonicus [68]) were downloaded from NCBI and used as queries in tBLASTn searches of the assembled U. unicinctus transcriptome database using BioEdit v7.0.9 with an E-value cutoff of 1e-5. Open reading frames (ORFs) in these mRNA sequences of potential neuropeptides were identified using DNASTAR v7.1. The resultant protein sequences were further evaluated based on (i) the presence of a putative N-terminal signal peptide identified by SignalP 4.1 and Signal-3 L 2.0 [69, 70]; (ii) the presence of putative monobasic or dibasic cleavage sites flanking the putative bioactive peptides according to the existing neuropeptide cleavage motifs [71]; (iii) the presence of a C-terminal glycine residue which is a putative amidation site, and (iv) the presence of cysteine residues which can form disulfide linkages.

Furthermore, we used a neuropeptide-prediction tool NpSearch (https://github.com/wurmlab/npsearch) to identify the putative neuropeptide precursors with low sequence similarity to known precursors based on various characteristics (signal peptide, cleavage sites, C-terminal glycine and cysteine residues). Functional annotation of the identified neuropeptide precursors was finally conducted by searching against NCBI non-redundant protein sequence (nr) database using BLASTx algorithm with the E-value of 1e-5.

The classification of U. unicinctus neuropeptides is mainly based on the researches of Jékely [28] and Conzelmann [30], and we have also updated the classification status of LFRYamide [72, 73], Cerebrin [28, 63, 74, 75] and RGWamide [30, 44, 45, 62–64, 76, 77] according to recent studies.

The neuropeptide precursor homologous sequences from other species were collected from GenBank. Multiple alignments were conducted using ClustalW [78], and the results were annotated with GeneDoc (https://genedoc.software.informer.com). The frequency of each amino acid in the alignment result was presented using the online tool WebLogo [79]. The hierarchical clustering of the pNP genes according to their FPKM values in the U. unicinctus larval transcriptome [29] was performed by an online tool (https://www.omicshare.com/tools/).

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA from each stored larval sample was isolated using MicroElute®Total RNA Kit (Omega, Norcross, USA) according to the manufacture’s instruction. The cDNA was synthesized for each sample using Prime-Script™ RT reagent Kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) with the gene specific primers (Supplementary Table S1) designed using Primer Premier 5.0 according to their predicted CDS sequences. The amplifications were performed with SYBR Premix Ex Taq kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) in LightCycler 480 Real-Time PCR system. The PCR mixture consisted of 10 μl SYBR Premix Ex Taq II, 1 μl template cDNA, 1 μl forward primer (10 μM), 1 μl reverse primer (10 μM) and 7 μl ddH2O. The qRT-PCR condition was: denature at 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 39 cycles of 5 s at 95 °C, and 60 °C for 30 s. Each sample was run in 3 technical replicates. The relative expression levels were normalized to the reference gene ATPase [80], and expression ratios were calculated using the 2–ΔΔCt method. The experimental data were presented as mean ± standard deviation from three samples with three parallel repetitions, and all RT-PCR assays were validated in compliance with “the MIQE guidelines” [81]. Significant differences between means were tested using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s HSD test with SPSS software 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH)

Specific fragments from cDNA of each neuropeptide genes were amplified using the primers with T7 or Sp6 promoter sequence at their 5′ ends (Supplementary Table S1). DIG-labeled RNA probes were prepared using the DIG RNA Labeling Kit SP6/T7 (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) with the PCR products as templates. WISH was carried out with the following protocols: the larvae were rehydrated with PBT (PBS + 0.1% Tween-20), and treated with 200 ng/μl proteinase K for 30 min to optimize hybridization; pre-hybridization was carried out for 6 h at 60 °C, then the probe was added and incubated at last 16 h at 60 °C; after the excess probe was removed by several rinses in hybridization buffer (50% formamide, 5 × SSC, 0.1% Tween, 9.2 mM citric acid for adjustment to pH 6.0, 50 μg/mL heparin, 500 μg/mL yeast RNA), the non-specific binding sites in the larval cells were blocked using the blocking buffer; the samples were incubated with the Anti-DIG-AP antibody (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) for 16 h at 4 °C; finally, the samples were stained in an NBT/BCIP staining solution (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and kept in the dark for 1 h, and then dehydrated. The results were observed and photographed using a Nikon E80i microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Drawings and final panels were designed using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe, San Jose, CA, USA).

Immunofluorescence histochemistry

The larva samples were rehydrated in a gradient methanol series (100, 75, 50 and 25%), and treated with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Shanghai biotechnology Technology, Shanghai, China) diluted by PBT (pH 7.4). Subsequently, the samples were transferred into primary antibody (Anti-5-hydroxytryptamine, an antibody produced in rabbit, Sigma, Jaffrey, USA) diluted 1: 200 in BSA and incubated overnight at 4 °C on a nutator. Afterwards, the samples were rinsed in PBT for 2 h and incubated subsequently with secondary fluorochrome conjugated antibodies (donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488, Invitrogen, CA, USA) diluted 1: 300 in PBT for 2 h. At last, the larvae were washed six times in PBT and incubated in PBT with 2.5% DAPI (Solarbio, Beijing, China) in the dark for 15 min to label cell nuclei. Negative controls were obtained by pre-immune serum in order to check for antibody specificity. All the samples were analyzed with the confocal laser-scanning microscope Nikon A1RSi (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Drawings and final panels were designed using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe, San Jose, CA, USA).

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Specific primers used in this research.

Additional file 2: Table S2. Detailed information of the identified neuropeptide precursors in U. unicinctus.

Additional file 3: Figure S1. Structures of U. unicinctus pNPs and identified repetitive peptide motifs.

Additional file 4: Figure S2. Expression trends of the neuropeptide precursor genes in U. unicinctus larval transcriptome.

Additional file 5: Figure S3. The negative controls of MIP, FRWa, FxFa and FILa in U. unicinctus larvae detected by whole-mount in situ hybridization.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their kind and helpful comments on the original manuscript.

Abbreviations

- pNPs

Neuropeptide precursors

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR

- ORF

Open reading frame

- SP

Signal peptide

- LT

Late-trochophore

- ES

Early- segmented larva

- SL

Segmented larva

- WL

Worm-shaped larva

- MIPs

Myoinhibitory peptides

- PL

Pre-competent larva

- CL

Competent larva

- POL

Post-competent larva

- 5HT

5-hydroxytryptamine

- CC

Circumoesophageal connectives

- LN

Longitudinal nerves

- VNC

Ventral nerve cord

- WISH

Whole-mount mRNA in situ hybridization

- FSW

Filtered sea water

- PSU

Practical salinity units

- LS

Late-segmented larva

- ANOVA

One-way analysis of variance

- PBS

Phosphate belanced solution

Authors’ contributions

Z.Z. and X.H. conceived the study, designed the experiment; X.H., Z.Q. and M.W. carried out the experiment; R.L. contributed technical assistance in drawing the Figures; Z.F., L.L. and S.B. contributed to animal treatment and sampling; X.H., Z.Z. and Y.M. wrote the article, and Z.Z. provided financial support for the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was support by Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (202064006), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31572601), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2020 M680095) and Shandong province science outstanding Youth Fund. The funding bodies played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analysed during the current study are available in the NCBI SRA repository (SRX397931, SRX398497, SRX4526076, SRX4526077, SRX4526078, SRX2999430, SRX4526079, SRX4526072, SRX4526073, SRX4526074, SRX4526075, SRX4526080, SRX2999431, SRX4526070, SRX4526071, SRX4526081).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The collection and handing of the U. unicinctus and experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the Guidelines for Experimental Animals of the Ministry of Science and Technology (Beijing, China) and approved by the Institutional Animal Welfare Committee of the College of Marine Life Sciences, Ocean University of China (Approval number: 2016016).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yubin Ma, Email: mayubin@ouc.edu.cn.

Zhifeng Zhang, Email: zzfp107@ouc.edu.cn.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12864-020-07312-4.

References

- 1.Hadfield MG. Why and how marine-invertebrate larvae metamorphose so fast. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2000;11:437–443. doi: 10.1006/scdb.2000.0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hodin J. Expanding networks: signaling components in and a hypothesis for the evolution of metamorphosis. Integr Comp Biol. 2006;46:719–742. doi: 10.1093/icb/icl038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feng D, Ke C, Lu C, Li S. The influence of temperature and light on larval pre-settlement metamorphosis: a study of the effects of environmental factors on pre-settlement metamorphosis of the solitary ascidian Styela canopus. Mar Freshw Behav Physiol. 2010;43:11–24. doi: 10.1080/10236240903523204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hadfield MG, Koehl MAR. Rapid behavioral responses of an invertebrate larva to dissolved settlement cue. Biol Bull. 2004;207:28–43. doi: 10.2307/1543626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qian PY. Larval settlement of polychaetes. Hydrobiologia. 1999;402:239–253. doi: 10.1023/A:1003704928668. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walters LJ, Miron G, Bourget E. Endoscopic observations of invertebrate larval substratum exploration and settlement. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1999;182:95–108. doi: 10.3354/meps182095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kornijów R, Pawlikowski K, Drgas A, Rolbiecki L, Rychter A. Mortality of post-settlement clams Rangia cuneata (Mactridae, Bivalvia) at an early stage of invasion in the Vistula Lagoon (South Baltic) due to biotic and abiotic factors. Hydrobiologia. 2018;811:207–219. doi: 10.1007/s10750-017-3489-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodriguez SR, Ojeda FP, Inestrosa NC. Settlement of benthic marine invertebrates. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1993;97:193–207. doi: 10.3354/meps097193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conzelmann M, Williams EA, Tunaru S, Randel N, Shahidi R, Asadulina A, et al. Conserved MIP receptor–ligand pair regulates Platynereis larval settlement. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:8224–8229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220285110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hadfield MG, Meleshkevitch EA, Boudko DY. The apical sensory organ of a gastropod veliger is a receptor for settlement cues. Biol Bull. 2000;198:67–76. doi: 10.2307/1542804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beer AJ, Moss M, Thorndyke M. Development of serotonin-like and SALMFamide-like Immunoreactivity in the nervous system of the sea urchin Psammechinus miliaris. Biol Bull. 2001;200:268–280. doi: 10.2307/1543509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dickinson AJG, Nason J, Croll RP. Histochemical localization of FMRFamide, serotonin and catecholamines in embryonic Crepidula fornicata (Gastropoda, Prosobranchia) Zoomorphology. 1999;119:49–62. doi: 10.1007/s004350050080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gruhl A. Serotonergic and FMRFamidergic nervous systems in gymnolaemate bryozoan larvae. Zoomorphology. 2009;128:135–156. doi: 10.1007/s00435-009-0084-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Voronezhskaya EE, Tsitrin EB, Nezlin LP. Neuronal development in larval polychaete Phyllodoce maculata (Phyllodocidae) J Comp Neurol. 2003;455:299–309. doi: 10.1002/cne.10488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watanabe H, Fujisawa T, Holstein TW. Cnidarians and the evolutionary origin of the nervous system. Develop Growth Differ. 2009;51:167–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2009.01103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bargmann CI. Beyond the connectome: how neuromodulators shape neural circuits. Bioessays. 2012;34:458–465. doi: 10.1002/bies.201100185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gruber CW. Physiology of invertebrate oxytocin and vasopressin neuropeptides. Exp Physiol. 2014;99:55–61. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2013.072561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nässel DR, Winther ÅME. Drosophila neuropeptides in regulation of physiology and behavior. Prog Neurobiol. 2010;92:42–104. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chun JY, Korner J, Kreiner T, Scheller RH, Axel R. The function and differential sorting of a family of aplysia prohormone processing enzymes. Neuron. 1994;12:831–844. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90336-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eipper BA, Stoffers DA, Mains RE. The biosynthesis of neuropeptides: peptide alpha-amidation. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1992;15:57–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.15.030192.000421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conzelmann M, Offenburger SL, Asadulina A, Keller T, Münch TA, Jékely G. Neuropeptides regulate swimming depth of Platynereis larvae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:1174–1183. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109085108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braubach OR, Dickinson AJ, Evans CC, Croll RP. Neural control of the velum in larvae of the gastropod, Ilyanassa obsoleta. J Exp Biol. 2006;209:4676–4689. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dickinson AJG, Croll RP. Development of the larval nervous system of the gastropod Ilyanassa obsoleta. J Comp Neurol. 2003;466:197–218. doi: 10.1002/cne.10863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dyachuk V, Odintsova N. Development of the larval muscle system in the mussel Mytilus trossulus (Mollusca, Bivalvia) Develop Growth Differ. 2009;51:69–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2008.01081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kempf SC, Masinovsky B, Willows AD. A simple neuronal system characterized by a monoclonal antibody to SCP neuropeptides in embryos and larvae of Tritonia diomedea (Gastropoda, Nudibranchia) J Neurobiol. 1987;18:217–236. doi: 10.1002/neu.480180207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hadfield MG, Carpizo-Ituarte EJ, Del Carmen K, Nedved BT. Metamorphic competence, a major adaptive convergence in marine invertebrate larvae. Am Zool. 2001;41:1123–1131. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huan P, Wang H, Liu B. A label-free proteomic analysis on competent larvae and juveniles of the pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0135008. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jékely G. Global view of the evolution and diversity of metazoan neuropeptide signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:8702–8707. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221833110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hou X, Wei M, Li Q, Zhang T, Zhou D, Kong D, et al. Transcriptome analysis of larval segment formation and secondary loss in the Echiuran worm Urechis unicinctus. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:1806. doi: 10.3390/ijms20081806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Conzelmann M, Williams EA, Krug K, Franz-Wachtel M, Macek B, Jékely G. The neuropeptide complement of the marine annelid Platynereis dumerilii. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:906. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watthanasurorot A, Söderhäll K, Jiravanichpaisal P, Söderhäll I. An ancient cytokine, astakine, mediates circadian regulation of invertebrate hematopoiesis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:315–323. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0458-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aravind L, Koonin EV. A colipase fold in the carboxy-terminal domain of the Wnt antagonists–the Dickkopfs. Curr Biol. 1998;8:477–478. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(98)70309-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Struck TH, Schult N, Kusen T, Hickman E, Bleidorn C, Mchugh D, et al. Annelid phylogeny and the status of Sipuncula and Echiura. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hessling R. Metameric organisation of the nervous system in developmental stages of Urechis caupo (Echiura) and its phylogenetic implications. Zoomorphology. 2002;121:221–234. doi: 10.1007/s00435-002-0059-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tilic E, Lehrke J, Bartolomaeus T. Homology and evolution of the chaetae in Echiura (Annelida) PLoS One. 2015;10:e0120002. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schoofs L, Holman GM, Hayes TK, Nachman RJ, De Loof A. Isolation, identification and synthesis of locustamyoinhibiting peptide (LOM-MIP), a novel biologically active neuropeptide from Locusta migratoria. Regul Pept. 1991;36:111–119. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(91)90199-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schoofs L, Veelaert D, Vanden Broeck J, De Loof A. Immunocytochemical distribution of Locustamyoinhibiting peptide (Lom-MIP) in the nervous system of Locusta migratoria. Regul Pept. 1996;63:171–179. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(96)00040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hua YJ, Tanaka Y, Nakamura K, Sakakibara M, Nagata S, Kataoka H. Identification of a prothoracicostatic peptide in the larval brain of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:31169–31173. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.44.31169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lorenz MW, Kellner R, Hoffmann KH. A family of neuropeptides that inhibit juvenile hormone biosynthesis in the cricket, Gryllus bimaculatus. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:21103–21108. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.36.21103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Minakata H, Ikeda T, Muneoka Y, Kobayashi M, Nomoto K. WWamide-1, −2 and −3: novel neuromodulatory peptides isolated from ganglia of the African giant snail, Achatina fulica. FEBS Lett. 1993;323:104–108. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81458-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Williamson M, Lenz C, Winther ME, Nässel DR, Grimmelikhuijzen CJ. Molecular cloning, genomic organization, and expression of a B-type (cricket-type) allatostatin preprohormone from Drosophila melanogaster. Biochem Bioph Res Co. 2001;281:544–550. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Williams EA, Conzelmann M, Jékely G. Myoinhibitory peptide regulates feeding in the marine annelid Platynereis. Front Zool. 2015;12:1. doi: 10.1186/s12983-014-0093-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huybrechts J, Bonhomme J, Minoli S, Prunier-Leterme N, Dombrovsky A, Abdel-Latief M, et al. Neuropeptide and neurohormone precursors in the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum. Insect Mol Biol. 2010;19:87–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2009.00951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Veenstra JA. Neuropeptide evolution: neurohormones and neuropeptides predicted from the genomes of Capitella teleta and Helobdella robusta. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2011;171:160–175. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang M, Wang Y, Li Y, Li W, Li R, Xie X, et al. Identification and characterization of neuropeptides by Transcriptome and proteome analyses in a bivalve Mollusc Patinopecten yessoensis. Front Genet. 2018;9:197. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hessling R. Novel aspects of the nervous system of Bonellia viridis (Echiura) revealed by the combination of immunohistochemistry, confocal laser-scanning microscopy and three-dimensional reconstruction. Hydrobiologia. 2003;496:225–239. doi: 10.1023/A:1026153016913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hessling R, Westheide W. Are Echiura derived from a segmented ancestor? Immunohistochemical analysis of the nervous system in developmental stages of Bonellia viridis. J Morphol. 2002;252:100–113. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Conzelmann M, Jékely G. Antibodies against conserved amidated neuropeptide epitopes enrich the comparative neurobiology toolbox. Evodevo. 2012;3:23. doi: 10.1186/2041-9139-3-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heyland A, Moroz LL. Signaling mechanisms underlying metamorphic transitions in animals. Integr Comp Biol. 2006;46:743–759. doi: 10.1093/icb/icl023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Laudet V. The origins and evolution of vertebrate metamorphosis. Curr Biol. 2011;21:726–737. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Truman JW, Riddiford LM. The origins of insect metamorphosis. Nature. 1999;401:447–452. doi: 10.1038/46737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kempf SC, Page LR, Pires A. Development of serotonin-like immunoreactivity in the embryos and larvae of nudibranch mollusks with emphasis on the structure and possible function of the apical sensory organ. J Comp Neurol. 1997;386:507–528. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19970929)386:3<507::AID-CNE12>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rentzsch F, Fritzenwankerv JH, Scholz CB, Technau U. FGF signalling controls formation of the apical sensory organ in the cnidarian Nematostella vectensis. Development. 2008;135:1761–1769. doi: 10.1242/dev.020784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Voronezhskaya EE, Khabarova MY. Function of the apical sensory organ in the development of invertebrates. Dokl Biol Sci. 2003;390:231–234. doi: 10.1023/A:1024453416281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Voronezhskaya EE, Khabarova MY, Nezlin LP. Apical sensory neurones mediate developmental retardation induced by conspecific environmental stimuli in freshwater pulmonate snails. Development. 2004;131:3671–3680. doi: 10.1242/dev.01237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chia FS, Buckland-Nicks J, Young CM. Locomotion of marine invertebrate larvae: a review. Can J Zool. 1984;62:1205–1222. doi: 10.1139/z84-176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Merz RA, Woodin SA. Polychaete chaetae: function, fossils, and phylogeny. Integr Comp Biol. 2006;46:481–496. doi: 10.1093/icb/icj057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Knight-Jones P, Fordy MR. Setal structure, functions and interrelationships in Spirorbidae (Polychaeta, Sedentaria) Zool Scr. 1979;8:119–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-6409.1979.tb00624.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sendall KA, Fontaine AR, O’Foighil D. Tube morphology and activity patterns related to feeding and tube building in the polychaete Mesochaetopterus taylori Potts. Can J Zool. 1995;73:509–517. doi: 10.1139/z95-058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Park C, Han YH, Lee SG, Ry KB, Oh J, Kern EMA, et al. The developmental transcriptome atlas of the spoon worm Urechis unicinctus (Echiurida: Annelida) GigaScience. 2018;7:1–7. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giy007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu X, Zhang L, Zhang Z, Ma X, Liu J. Transcriptional response to sulfide in the Echiuran worm Urechis unicinctus by digital gene expression analysis. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:829. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-2094-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stewart MJ, Favrel P, Rotgans BA, Wang T, Zhao M, Sohail M, et al. Neuropeptides encoded by the genomes of the Akoya pearl oyster Pinctata fucata and Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas: a bioinformatic and peptidomic survey. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:840. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Veenstra JA. Neurohormones and neuropeptides encoded by the genome of Lottia gigantea, with reference to other mollusks and insects. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2010;167:86–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ahn SJ, Martin R, Rao S, Choi MY. Neuropeptides predicted from the transcriptome analysis of the gray garden slug Deroceras reticulatum. Peptides. 2017;93:51–65. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Semmens DC, Mirabeau O, Moghul I, Pancholi MR, Wurm Y, Elphick MR. Transcriptomic identification of starfish neuropeptide precursors yields new insights into neuropeptide evolution. Open Biol. 2016;6:150224. doi: 10.1098/rsob.150224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zandawala M, Moghul I, Yañez Guerra LA, Delroisse J, Abylkassimova N, Hugall AF, et al. Discovery of novel representatives of bilaterian neuropeptide families and reconstruction of neuropeptide precursor evolution in ophiuroid echinoderms. Open Biol. 2017;7:170129. doi: 10.1098/rsob.170129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rowe ML, Elphick MR. The neuropeptide transcriptome of a model echinoderm, the sea urchin Strongylocentrotus purpuratus. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2012;179:331–344. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rowe ML, Achhala S, Elphick MR. Neuropeptides and polypeptide hormones in echinoderms: new insights from analysis of the transcriptome of the sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2014;197:43–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Petersen TN, Brunak S, Von Heijne G, Nielsen HH. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat Methods. 2011;8:785–786. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang YZ, Shen HB. Signal-3L 2.0: a hierarchical mixture model for enhancing protein signal peptide prediction by incorporating residue-domain cross-level features. J Chem Inf Model. 2017;57:988–999. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.6b00484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu F, Baggerman G, D'Hertog W, Verleyen P, Schoofs L, Wets G. In silico identification of new secretory peptide genes in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:510–522. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400114-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fadda M, Hasakiogullari I, Temmerman L, Beets I, Zels S, Schoofs L. Regulation of feeding and metabolism by neuropeptide F and short neuropeptide F in invertebrates. Front Endocrinol. 2019;10:64. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yañez-Guerra LA, Zhong X, Moghul I, Butts T, Zampronio CG, Jones AM, et al. Echinoderms provide missing link in the evolution of PrRP/sNPF-type neuropeptide signalling. Elife. 2020;9:e57640. doi: 10.7554/eLife.57640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nässel DR, Zandawala M. Recent advances in neuropeptide signaling in Drosophila, from genes to physiology and behavior. Prog Neurobiol. 2019;179:101607. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2019.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mirabeau O, Joly JS. Molecular evolution of peptidergic signaling systems in bilaterians. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:2028–2037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219956110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bauknecht P, Jékely G. Large-scale combinatorial deorphanization of Platynereis neuropeptide GPCRs. Cell Rep. 2015;12:684–693. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Thiel D, Franz-Wachtel M, Aguilera F, Hejnol A. Xenacoelomorph neuropeptidomes reveal a major expansion of neuropeptide systems during early bilaterian evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35:2528–2543. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14:1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wei M, Lu L, Wang Q, Kong D, Zhang T, Qin Z, et al. Evaluation of suitable reference genes for normalization of RT-qPCR in Echiura (Urechis unicinctus) during developmental process. Russ J Mar Biol. 2019;45:464–469. doi: 10.1134/S1063074019300023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, Hellemans J, Huggett J, Kubista M, et al. The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin Chem. 2009;55:611–622. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Specific primers used in this research.

Additional file 2: Table S2. Detailed information of the identified neuropeptide precursors in U. unicinctus.

Additional file 3: Figure S1. Structures of U. unicinctus pNPs and identified repetitive peptide motifs.

Additional file 4: Figure S2. Expression trends of the neuropeptide precursor genes in U. unicinctus larval transcriptome.

Additional file 5: Figure S3. The negative controls of MIP, FRWa, FxFa and FILa in U. unicinctus larvae detected by whole-mount in situ hybridization.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analysed during the current study are available in the NCBI SRA repository (SRX397931, SRX398497, SRX4526076, SRX4526077, SRX4526078, SRX2999430, SRX4526079, SRX4526072, SRX4526073, SRX4526074, SRX4526075, SRX4526080, SRX2999431, SRX4526070, SRX4526071, SRX4526081).