Abstract

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) harboring BRAFV600E mutation exhibits low response to conventional therapy and poorest prognosis. Due to the emerging correlation between gut microbiota and CRC carcinogenesis, we investigated in serrated BRAFV600E cases the existence of a peculiar fecal microbial fingerprint and specific bacterial markers, which might represent a tool for the development of more effective clinical strategies.

Methods

By injecting human CRC stem-like cells isolated from BRAFV600E patients in immunocompromised mice, we described a new xenogeneic model of this subtype of CRC. By performing bacterial 16S rRNA sequencing, the fecal microbiota profile was then investigated either in CRC-carrying mice or in a cohort of human CRC subjects. The microbial communities’ functional profile was also predicted. Data were compared with Mann-Whitney U, Welch’s t-test for unequal variances and Kruskal-Wallis test with Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) correction, extracted as potential BRAF class biomarkers and selected as model features. The obtained mean test prediction scores were subjected to Receiver Operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. To discriminate the BRAF status, a Random Forest classifier (RF) was employed.

Results

A specific microbial signature distinctive for BRAF status emerged, being the BRAF-mutated cases closer to healthy controls than BRAF wild-type counterpart. In agreement, a considerable score of correlation was also pointed out between bacteria abundance from BRAF-mutated cases and the level of markers distinctive of BRAFV600E pathway, including those involved in inflammation, innate immune response and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. We provide evidence that two candidate bacterial markers, Prevotella enoeca and Ruthenibacterium lactatiformans, more abundant in BRAFV600E and BRAF wild-type subjects respectively, emerged as single factors with the best performance in distinguishing BRAF status (AUROC = 0.72 and 0.74, respectively, 95% confidence interval). Furthermore, the combination of the 10 differentially represented microorganisms between the two groups improved performance in discriminating serrated CRC driven by BRAF mutation from BRAF wild-type CRC cases (AUROC = 0.85, 95% confidence interval, 0.69–1.01).

Conclusion

Overall, our results suggest that BRAFV600E mutation itself drives a distinctive gut microbiota signature and provide predictive CRC-associated bacterial biomarkers able to discriminate BRAF status in CRC patients and, thus, useful to devise non-invasive patient-selective diagnostic strategies and patient-tailored optimized therapies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13046-020-01801-w.

Keywords: Serrated human BRAFV600E colorectal carcinoma (CRC), Gut microbiota, CRC biology and biomarkers, BRAFV600E CRC non-invasive diagnosis, Anti-BRAFV600E CRC patient-tailored strategies

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in developed countries [1]. Although some risk factors are well outlined [2] and many comprehensive studies have established the molecular criteria for CRC’s classification [1, 3, 4], the regulatory mechanisms of this tumor remain largely unrevealed.

The inherent extensive heterogeneity of CRC encompasses as many different histological and molecular bases associated with diverse clinical-pathological features. The adenoma-carcinoma sequence proposed by Vogelstein, in which the pre-neoplastic lesions accumulate stepwise molecular and morphological changes leading to cancer [5], has been long considered a unique model of CRC cancerogenesis until the description of the “serrated pathway” [6, 7]. This pathway arises from serrated polyps, once considered benign, including hyperplastic polyps (HPs), sessile serrated adenomas/polyps (SSAs/Ps) and traditional serrated adenomas (TSAs) [8, 9]. Among these, HPs are the most frequent (80–90%) and usually display a low malignant potential, while TSAs account for less than 1% of serrated CRCs [10]. SSAs/SSPs, which account for the 5–20% of all the serrated lesions, display peculiar molecular features, including CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP-H) and BRAF mutation [9, 11]. CIMP-H results in transcriptional repression of p16INK4a and MLH1 genes, whereas BRAF mutations, often consisting in the activating V600E substitution, causes aberrant activation of the MAPK signaling [12, 13].

From a clinical point of view, BRAF-mutated CRC behave as a distinct subset compared to conventional adenomas, typically exhibiting lower response to conventional therapy, elevated invasiveness and the poorest clinical outcome, suggesting that initiation through this pathway might predict the aggressiveness of CRC [6, 13].

It is nowadays recognized that a small subpopulation of self-renewing CRC cancer stem cells (CCSCs) drive the initiation and progression of CRC, the metastatic colonization and the disease relapse after therapy [14, 15]. We have also very recently reported in our human CCSCs-based in vivo model that stemness underpins all the stages of CRC development, identifying CCSCs as a constitutive component in the establishment and dissemination of this tumor [16].

Disruption of the gut microbial community’s homeostasis, i.e. dysbiosis, also plays an important role in the initiation and maintenance of CRC as well as in the response to therapies [17–21]. In recent years a plethora of studies revealed the existence of a human CRC-specific microbial signature, underlining the pathogenetic role of some microorganisms, such as Streptococcus gallolyticus, Bacteroides fragilis, Enterococcus faecalis, Fusobacterium spp., Fusobacterium nucleatum and Escherichia coli. Yet, the expansion of these “bad” bacterial species with the ensuing depletion of “good microbes” has been shown to be implicated in DNA damage, uncontrolled cell growth, inflammatory signaling pathways and, thus, in CRC promotion and progression [22–24]. Additionally, it has been speculated that gut microbiota shift might be related to different early precursors of CRC, but whether specific microbial profiles could discriminate between conventional and BRAF-mutated CRC still remains under-investigated [25–27].

Here, we report either in our CCSCs-based in vivo model or in CRC patients that BRAFV600E mutation can itself sustain a typical microbiota profile, thus identifying new putative tumor-associated bacterial markers for patient-tailored diagnostic and therapeutic purposes.

Methods

Primary CCSCs culture and analysis, immunochemistry, reagents, targeted and sanger sequencing, qPCR and methylation-specific PCR, bacterial DNA extraction are described in detail in the Supplementary Methods.

In vivo studies

All the animal experimental procedures were performed in compliance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Animal protocols have been approved by the Ministry of Health (PR/15–297/2019-PR). In order to minimize any suffering of the animals, anesthesia and analgesics were used when appropriate. Orthotopical PDX was determined by injecting CCSCs into the wall submucosa of the ascending colon of Scid/bg mice (Charles River Lab) [16]. Quantification of tumor growth was performed from ventral and dorsal views by In vivo Lumina (Xenogen, PerkinElmer Inc) [16, 28]. Upon sacrifice at different time points according to the cell line originally injected, tissue samples from CCSCs-derived primary colon tumors and from mesenteric lymph nodes as well as lung, liver, spleen and brain metastases were collected and processed as previously reported [16, 28–30]. Spontaneous metastatic pulmonary lesions formation was performed by injecting 3 × 105 luc-CCSCs cells into the lateral tail-vein of Scid/bg mice [16]. For the gut microbiota analysis, fresh fecal samples were collected from the cages at early-stage (7 days post-transplantation; DPT) and next to the median end-stage of the disease (late and end-stages, 37–43 DPT). Samples were immediately frozen and stored at − 80 °C until DNA extraction.

Clinical patient’s features

Patients with a confirmed diagnosis of CRC (33 cases) and healthy subjects (13 subjects) included in the control group were enrolled in this study at IRCCS “Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza” Hospital, under the Ethical committee approvals number N.175/CE and N.94/CE. All the subjects agreed to participate according to the ethical guidelines of the 2013 Declaration of Helsinki and signed an informed consent. Eligible subjects were 45–90 years old who did not undergo radio/chemotherapy or pharmacological/long-term antibiotic treatments. All the fecal samples were collected at the moment of diagnosis before any surgery or adjuvant treatment. Human CRC tissues were classified according to established staging system (AJCC and TNM) and diagnosis was confirmed by the pathologist. Histological data together with localization of colonic lesions are reported in Table 1. Fresh stool samples were collected by each participant in containers with DNA stabilization buffer (Canvax Biotech) and stored at RT for few days until DNA extraction. Information regarding subject’s variables (i.e. age, gender and BMI) as well as dietary, lifestyle and smoking habits were assessed the same day of the stool sample collection.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients involved in the study

| Sample name | Age | Sex | Location of cancer | AJCC Stage | BRAFV600E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MI4KC | 63 | M | Left colon | IIIA | wild type |

| MI6KC | 62 | M | Rectum | IIIB | wild type |

| MI7KC | 73 | M | Right colon | IIA | wild ttype |

| MI11KC | 50 | M | Rectum | IV | wild type |

| MI12KC | 74 | F | Left colon | IIIA | wild type |

| MI15KC | 74 | M | Right colon | IV | mutated |

| MI16KC | 49 | M | Rectum | IV | mutated |

| MI17KC | 49 | F | Left colon | IIA | wild type |

| MI23KC | 53 | F | Right colon | IV | mutated |

| MI22KC | 67 | M | Rectum | IV | mutated |

| MI27KC | 80 | F | Right colon | IIIA | wild type |

| MI31KC | 81 | M | Rectum | IIIB | wild type |

| MI32KC | 80 | M | Right colon | II | wild type |

| MI34KC | 80 | M | Right colon | IIA | mutated |

| MI36KC | 51 | F | Rectum | IIA | wild type |

| MI39KC | 49 | M | Rectum | IV | wild type |

| MI41KC | 77 | M | Right colon | IV | mutated |

| MI40KC | 55 | M | Left colon | IV | mutated |

| MI9KC | 76 | M | Rectum | I | wild type |

| MI10KC | 87 | F | Left colon | I | wild type |

| MI19KC | 68 | M | Right colon | I | wild type |

| MI20KC | 85 | F | Right colon | I | wild type |

| MI21KC | 87 | F | Left colon | I | wild type |

| MI25KC | 70 | M | Left colon | I | wild type |

| MI26KC | 65 | M | Rectum | I | wild type |

| MI35KC | 72 | F | Left colon | I | wild type |

| MI42KC | 87 | M | Right colon | I | wild type |

| MI43KC | 67 | M | Rectum | IV | mutated |

| MI38KC | 59 | F | Rectum | III | wild type |

| MI28KC | 72 | M | Rectum | IIA | wild type |

| MI14KC | 59 | F | Rectum | IIA | wild type |

| MI13KC | 72 | M | Right colon | IV | wild type |

| MI30KC | 60 | M | Right colon | I | wild type |

Sequencing and analysis of 16S rRNA

Library preparation and sequencing was performed with Illumina 16S Metagenomic Sequencing Library Preparation kit (Illumina Inc) accordingly to manufacture’s instruction. Briefly, the V3–V4 hypervariable region of the bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA was amplified with primers selected from [31], containing appropriate Illumina overhang adapter sequences. Amplicons were further amplified to attach dual Illumina indices (Nextera XT Index Kit, Illumina Inc) and PCR products again purified. The pooled libraries were paired-end sequenced (2 × 300 cycles) in Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina Inc). Sequences were demultiplexed and FASTQ files were generated. Raw sequencing data were then trimmed for quality and Illumina adapters were removed. After excluding host reads, reads were aligned and mapped to the NCBI taxonomy database of bacterial and archaeal 16S rRNA sequences, using Kraken2 software [32]. Rarefaction curves were generated by randomly subsampling the OTU tables to a depth of 61,888 and 12,609 sequences (for mouse and human samples, respectively) per sample 10 times before computing the observed species. Several a-diversity metrics, including Chao1 and Shannon index, the Simpson reciprocal and the observed genus and species, were computed. To assess b-diversity in xenogeneic CRCs, jackknifed Bray–Curtis distances (10 sub-samplings at a depth of 61,888 sequences per sample) was computed and the matrices visualized in PCoA plot. Core diversity analysis was performed on the OTU tables, including a- and b-diversity as well as taxonomic summary, as implemented in QIIME software [33]. To account for library size, OTU profiles were converted to relative abundances and then filtered for species confidently detectable. Specifically, microbial species that did not exceed a maximum abundance of 1 × 10− 3 in at least one sample were excluded, together with the fraction of unmapped metagenomic reads. Hierarchical cluster analysis and visualization of the relative abundances were performed with Partek Genomics Suite v.6.6 software (Partek Inc.).

Functional profile prediction

Based on the 16S rRNA sequences, microbial communities’ functional composition was predicted using PICRUSt software [34]. All sequences from each sample were searched against the Greengenes (gg_13_5) at the 97% identity (closed OTU picking method). OTU tables were normalized by dividing each OTU by the known/predicted 16S rRNA gene copy number abundance and the prediction of the metagenome functional content was classified according to the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Orthology. The predicted metagenome BIOM table was analyzed and visualized using the Statistical Analysis of Taxonomic and Functional Profiles (STAMP) v. 2.1.3 software [35].

Statistical analyses

For in vitro studies, statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism v7.0 software and ANOVA tests according to the variance and distribution of data. Differential gene expression was assessed by the implementation of the ANOVA test available in Partek Genomic Suite 6.6 with FDR < 0.05. P-values< 0.05 were considered significant. Results from 16S rRNA gene sequences between or among groups were compared with nonparametric Mann-Whitney U, Student’s t-test (or Welch’s t-test for unequal variances) and Kruskal-Wallis test with Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) correction for multiple comparisons at each level separately. FDR (q-value) < 0.10 was considered significant. Pearson correlation coefficient was used to assess association between gene expression and bacterial abundance at genus level in BRAFV600E vs healthy and BRAF wt mice (43DPT) (q-values < 0.1). P < 0.05 was visualized. To discriminate the BRAF status in CRC patients, a Random Forest classifier (RF) was used [36]. The number of decision trees was set to 500. Significantly different bacterial species’ abundance between BRAFV600E and BRAF wt CRC cases, as emerged from Mann-Whitney test (P < 0.05), was extracted as potential BRAF class biomarkers and selected as model features. From 8-fold cross-validation, mean test prediction scores were obtained and subjected to Receiver Operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. ROC curve was used to evaluate the diagnostic value of bacterial candidates in distinguishing BRAF-mutated from BRAF wt cases. A Fisher’s exact test was also performed. RF was firstly applied on the whole set of selected features and then on each one of them to identify the most important ones, ranked by areas under ROC (AUROC) metric. The best cut-off values were determined by ROC analyses that maximized the Youden index (J = Sensitivity + Specificity - 1 [31]. All statistical analyses were conducted using R software.

Results

Molecular and pathophysiological features of BRAF-mutated and BRAF wild-type CRC stem-like cells

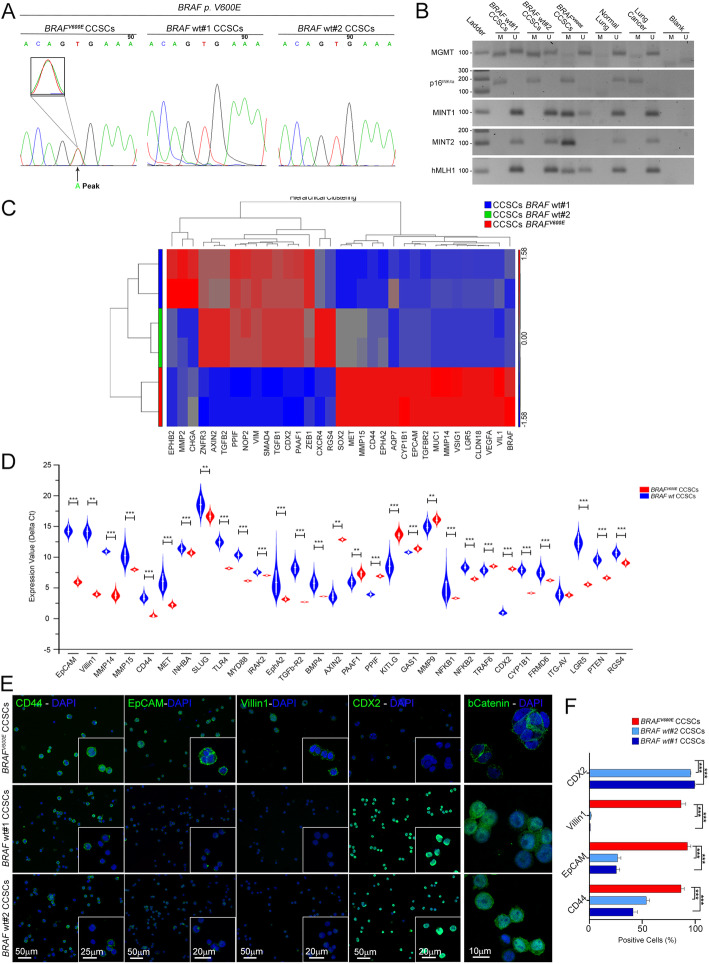

By orthotopical injections of CRC stem-like cells (CCSCs) we have previously reported an in vivo model, which faithfully recapitulates human CRC features [16]. Here we characterized and confirmed in vitro and in vivo the phenotypic hallmarks of the three CCSCs lines isolated from CRC patient’s tissue, either associated to serrated pathway (BRAFV600E CCSCs) or conventional CRC (BRAF wt CCSCs) [16]. To verify as to whether BRAFV600E CCSCs reflects the key characteristics of serrated CRC, we delineated the presence of BRAF mutation and the unchanged form of KRAS and NRAS and the CIMP-H phenotype [37]. As shown in Fig. 1a, BRAFV600E CCSCs are characterized by the presence of BRAF point mutation T1796A in exon 15 codon 599, reflecting a valine to a glutamic acid amino acid shift (V600E). Consistently, a methylated status of the promoter regions of p16INK4a, MutL homolog1 (hMLH1), MGMT, MINT1 and MINT2 genes was shown (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Phenotypic fingerprint of BRAFV600E and BRAF wt CCSCs. a Automatic sequencing electrogram showing a minor “A” peak at T1796 denoting a CCSCs’ population retaining such a “T1796A” mutation with a T to A mutation in codon 599 (BRAFV600E CCSCs; arrowhead). b MGMT, p16INK4a, MINT1, MINT2 and hMLH1 methylation was evaluated in BRAFV600E and BRAF wt CCSCs by using primers for methylated (M) and unmethylated (U) alleles of bisulfite-treated DNA. Normal and cancer lung tissues as positive controls. c Heat map of one-way hierarchical clustering of 33 differentially expressed genes in BRAF-mutated vs. BRAF wt CCSCs revealing a typical CRC serrated signature for the former as compared to the latter. A dual-color code represents genes up- (red) and down-regulated (blue), respectively. d Differentially enriched genes associated with cellular migration and invasiveness, matrix degradation and epithelial phenotype in BRAFV600E vs BRAF wt CCSCs, as confirmed by qPCR. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, Mann-Whitney test. e By means of confocal imaging, widespread positivity for CD44, EpCAM and Villin1 markers and weak signal for CDX2 in BRAFV600E CCSCs was shown. Positive nuclear b-catenin staining was retrieved exclusively in BRAF wt CCSCs. Insets: higher magnifications. Scale bars, 50um, 25um, 20um and 10um. Quantification of each marker is shown in f. ***P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Data are mean ± SEM

To pinpoint the inherent “serrated” signature of BRAFV600E CCSCs, we next compared the transcriptional profile of CCSC lines to each other (Fig. 1c-e). As expected, hierarchical clustering analysis based on the global gene expression clearly segregated the serrated BRAFV600E CCSCs from the other two CCSCs lines, which are quite similar (Fig. 1c). Consistently, among the genes preferentially expressed in BRAFV600E CCSCs, many are reported to be up-regulated in the BRAFV600E CRC pathway as well as to control matrix remodeling and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, inflammation and innate immunity, cell migration and invasion and transforming growth factor-b (Fig. 1d) [6, 38]. Meanwhile, transcriptomic fingerprint of BRAFV600E CCSCs was identified by low levels of CDX2 and Wnt target genes [39]. The epithelial cell adhesion molecule EpCAM, CD44 and VIL1 protein expression was confirmed to be a hallmark feature of CCSCs with a “serrated” phenotype, as compared to the BRAF wt counterpart, whereas CDX2 marker was highlighted exclusively in the latter (Fig. 1e-f). B-catenin protein was mainly localized in the plasma membrane in BRAFV600E CCSCs cells (Fig. 1e) [16].

Strikingly, following orthotopical delivery of BRAFV600E CCSCs, tumors with histological architectures, that closely resemble the human serrated pathway, were detected, whereas the typical CRC morphology was identified in lesions from BRAF wt CCSCs-bearing mice (Fig. 2a-b). Though all CCSCs gave rise to distant spontaneous metastatic lesions [16], only mice infused intravenously with BRAFV600E CCSCs exhibited pulmonary metastasis within 60 days after injection (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2.

In vivo behavior of xenogeneic BRAF-mutated and BRAF wt CRC. a Quantitative time-course analysis of mice injected with luciferase-tagged BRAFV600E (top) and BRAF wt CCSCs (middle and bottom). The progression of human CRCs was monitored from 3DPT (left) next to the end-stage disease typical of each CCSCs injected. b Histologic analysis, as expressed by H&E staining, revealing features of human serrated CRC with villiform architecture, micropapillary clusters and signet ring cells in BRAFV600E lesions (top) while marked nuclear atypia and hemorrhagic necrosis (middle and bottom) were detected in BRAF wt CRCs. c OCT-embedded lung sections (left) marked with H&E (middle) depicting pulmonary lesions (arrowhead) in mice infused with BRAFV600E CCSCs into the lateral tail-vein (n = 3 mice per groups). Widespread immunoreactivity for the human nuclei marker in BRAFV600E lesions is shown (right). Scale bars, 1000um, 100um and 50um

These findings lent to the conclusion that BRAFV600E CCSCs recapitulates the main features of serrated CRC, being a faithful model for in vivo studies of serrated tumorigenesis.

Microbiota profiles and functional composition of BRAF-mutated and BRAF wt xenogeneic CRCs

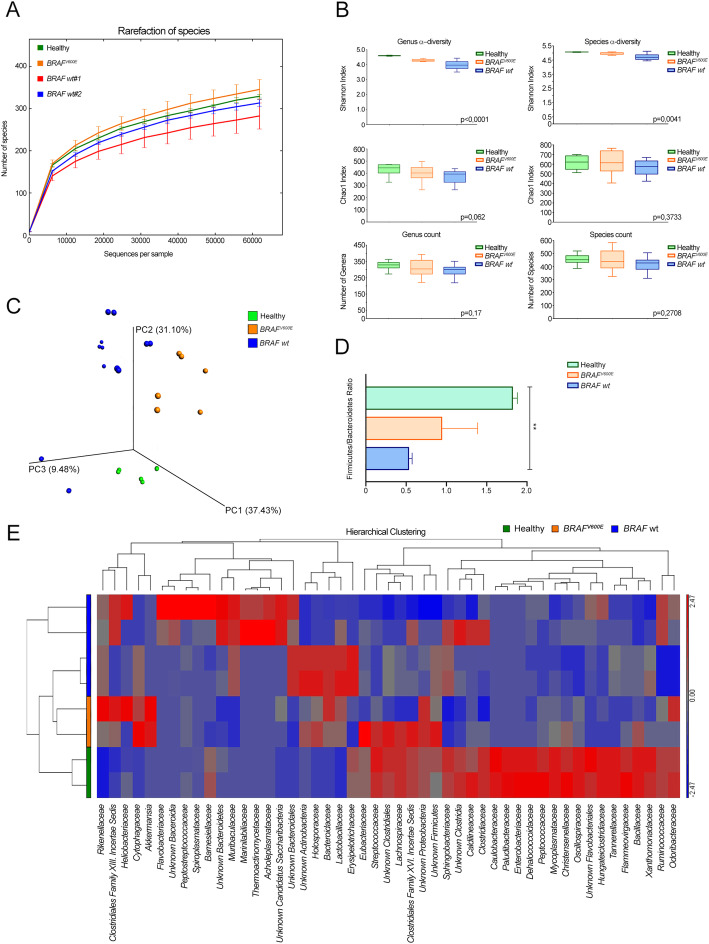

To explore associations between gut microbiota composition and BRAFV600E CRC, we first exploited our xenogeneic CRC model, in terms of global alteration in the microbiota profiles of BRAFV600E and BRAF wt CRC-bearing mice vs control. Bacterial flora was analyzed either at early stage or next to the median end-stage of the disease (Figs. 3 and 4, Supplementary Table S1-S2). Species richness was found higher in controls and BRAFV600E xenogeneic CRCs than in BRAF wt tumors (Fig. 3a). As indicated by the a-diversity Shannon index, xenogeneic BRAF-mutated CRC and controls displayed a higher microbial community diversity than BRAF wt CRC-carrier group, both at genus and species level (P < 0.0001 and P = 0.004, respectively, Kruskal-Wallis test) (Fig. 3b, top), whereas genus and species richness did not reach significance among the groups (Fig. 3b, middle and bottom). Next, we explored the signature of the gut microbiota in the CRC-carrier groups vs control observing in the former a remarkable clustering within the progression of the disease over time (Fig. 3c). Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes were found the most represented phyla in all groups, together with Proteobacteria, Tenericutes and Verrucomicrobia (Supplementary Table S1-S2). Yet, the key marker of gut dysbiosis [40] Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio, tended to be comparable between xenogeneic BRAFV600E CRCs and control, whereas was significantly lower in mice bearing BRAF wt tumors (Fig. 3d). Unsupervised hierarchical analysis at the family level (Fig. 3e) revealed a characteristic “healthy” microbial signature in controls segregated from that one of CRC-bearing mice, being BRAFV600E CRCs closer to tumor-free mice than BRAF wt tumors. Notably, an enrichment in several butyrate-producing bacteria such as Clostridiales, Eubacteriaceae, Lachnospiraceae, Proteobacteria, Firmicutes and Streptococcaceae was observed in mice carrying BRAFV600E CRC as well as in control.

Fig. 3.

Microbial communities associated to BRAFV600E and BRAF wt lesions. a Rarefaction curves for the analysis of microbial species content in the three groups of mice. b Microbial community a-diversity (top) and richness (middle and bottom) of the same groups at the genus (left) and species (right) level are shown. P values are from Kruskal-Wallis test are shown. c PCoA plot at the operational taxonomic unit (OTU) level showing the clustering pattern over time. d Ratio between Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes at 43DPT. **P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Data are mean ± SEM. e Unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis based on microbial communities’ presence at the family level showing an “healthy” profile in controls and a typical signature for each of the two CRC-carrier group. A dual-color code represents microbial families over-(red) and under-represented (blue)

Fig. 4.

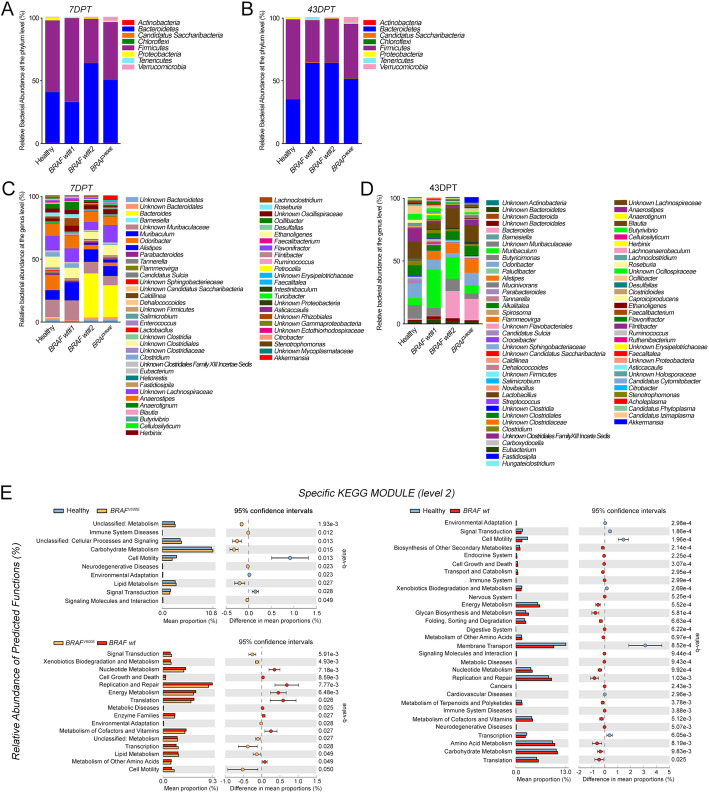

BRAFV600E CRC exhibits specific bacterial markers and a typical functional microbiota composition. Gut microbiota relative abundance (% similarity) at the phylum (a-b) and genus level (c-d) in gut microbiota of mice carrying BRAFV600E and BRAF wt CRC and controls at 7 DPT (a-c) and 43 DPT (b-d). e Significative relative abundance of predicted function (mean proportions %) and different abundance of predicted function (difference in mean proportion %) for specific KEGG modules level 2 in pairwise comparisons between controls, BRAFV600E (left; top) and BRAF wt CRCs (right) or between the two CRC groups (left; bottom). FDR-adjusted p value (q value) from Mann-Whitney test are shown

Analyzing at the phylum level the bacterial flora of xenogeneic BRAFV600E CRC versus control at 7 DPT (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Table S1), Verrucomicrobia (2.9% vs 0.2%, FDR = 0.005) and Bacteroidetes (47% vs 38%, FDR = 0.04) emerged more represented. Conversely, a significant lower presence of Firmicutes (43% vs 54%, FDR = 0.04), Proteobacteria (1% vs 2%, FDR = 0.04), Tenericutes (0.1% vs 0.2%, FDR = 0.04) and Chloroflexi (0.1% vs 0.3%, FDR = 0.04) was observed. Strikingly, these differences were abolished at 43 DPT (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Table S2). Yet, among the mostly represented bacterial genera in samples from BRAFV600E CRC at 7 DPT (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Table S1), the highest abundance was found in Bacteroides (23.6% vs 0.5%, FDR = 0.05), Akkermansia (2.9% vs 0.3%, FDR = 0.007), Butyrivibrio (1.4% vs 0.3%, FDR = 0.004) and Lactobacillus (0.17% vs 0.07%, FDR = 0.03), whereas Odoribacter (2.6% vs 11.3%, FDR = 0.04), Clostridum (0.8% vs 3.1%, FDR = 0.009), Roseburia (0.5% vs 2.7%, FDR = 0.03) and Ruminococcus (0.4% vs 1.1%, FDR = 0.01) were among the most poorly represented. Conversely, at 43DPT all the identified genera were poorly present in BRAFV600E CRC-bearing mice with respect to control (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Table S2). Consistently, all the differences detected down at the species level in BRAFV600E CRC-carrying mice vs controls at 7 DPT were abolished at 43DPT (Supplementary Table S1-S2).

Concerning the shifts in the microbiota profile shared by the two BRAF wt CRC-carrier groups vs controls at 7 DPT, lower abundances of few genera either belonging to Firmicutes or to Bacteroidetes were detected (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Table S1). Unlike xenogeneic BRAFV600E CRC, at 43DPT, the relative bacterial abundance at the phylum and genus level seemed to be clearly different from that one of control (Fig. 4b, d and Supplementary Table S2). Proteobacteria (0.03 and 1% vs 1.5%, FDR = 0.035, FDR = 0.01) and Bacteroidetes (61.3 and 61.1% vs 33%, FDR = 0.03, FDR = 0.002) were shown to be phyla overrepresented in BRAF wt CRC-carrier groups, while Firmicutes were more abundant in controls (31.8 and 33.4% vs 60.1%, FDR = 0.035, FDR = 0.002). Further, consistently with Fig. 3e, Roseburia and Lachnoanaerobaculum genera, together with Asticcacaulis and Ethanoligenens declined in BRAF wt CRCs at 43 DPT, as compared to control.

When the microbial communities’ functional composition was compared between CRC-bearing mice and control (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Table S3), according to the level 2 KEGG module the relative abundance of immune system diseases (FDR = 0.012) category together with carbohydrate metabolism (FDR = 0.015) [41] emerged significantly higher in xenogeneic BRAF-mutated CRCs, whereas a remarkable enrichment of general metabolic functions was observed in BRAF wt CRCs. Consistently, when comparing the two CRC-carrier groups, cell motility (FDR = 0.05) and transcription (FDR = 0.03) categories were significantly enriched in BRAFV600E CRCs, whereas metabolic functions were overrepresented in BRAF wt counterpart.

All of these data delineate a microbial signature associated to xenogeneic BRAFV600E CRC, reminiscent of that one of control.

Microbial taxa’s abundance correlates with gene expression in BRAFV600E xenogeneic CRC

We then looked for a potential association between microbiota composition and the transcriptomic hallmarks of the BRAFV600E serrated pathway [6]. For this purpose, the relative abundance of bacterial genera associated with xenogeneic BRAFV600E CRC and the expression level of markers distinctive of BRAFV600E CCSCs (Fig. 1e) were correlated with each other. A considerable score of positive correlation was identified between genera along with Firmicutes phylum, i.e. Oscillibacter, Desulfallas, Anaerostipes and Ethanoligenens, together with Akkermansia, and genes involved in the BRAFV600E pathway, inflammation and innate immunity and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (Fig. 5a). Yet, a negative correlation trend was shown with almost all the Wnt target genes, CDX2 and genes involved in the TGFb pathway. Remarkably, a specular correlation trend was shown for genera along with Bacteroidetes phylum, such as Muribaculum and genera belonging to Bacteriodales, Muribaculaceae and Sphingobacteriaceae.

Fig. 5.

Correlation between BRAFV600E CRC microbial composition and the level of serrated markers. a Pearson’s correlation coefficient computed between the relative abundance of microbial communities’ presence at the genus level in BRAFV600E CRCs vs either the BRAF wt counterpart or control (q < 0.10) and the level of markers distinctive for serrated BRAFV600E CCSCs. Significant correlation coefficients were visualized (P < 0.05). Red and blue, positive and negative correlation, respectively. Color intensity represents the increase/decrease of value

Data here suggest the existence of a bidirectional communication, involving inflammation, invasion and innate immune signaling, between the BRAFV600E lesion and the gut microbiota.

Gut microbiota fingerprint in serrated BRAFV600E and BRAF wt CRC patients

We next investigated the microbiota composition in a cohort of CRC patients who did not undergo any type of treatment (8 BRAFV600E and 25 BRAF wt CRC) and healthy controls [13]. Early-stage stage I BRAF wt CRCs were excluded (Fig. 6a and Table 1) [41]. As shown in Fig. 6b, no significant differences were observed between CRC cases and controls in terms of age or the body mass index (BMI). Variants in BRAF were confirmed c. 1799 T > A mutation (p.V600E) (Table 1) and, as expected, a mutually exclusive missense mutation in KRAS and NRAS genes was found. When bacterial community properties were analyzed, the highest level of species richness was reported in BRAF-mutated and control groups vs BRAF wt cases (Fig. 6c). A-diversity and community richness were significantly different among the groups at genus level (P = 0.02 and P = 0.016, respectively, Kruskal-Wallis test) and, down at species level, displayed the lowest expression in BRAF wt cases (P = 0.031) (Fig. 6d).

Fig. 6.

Microbial communities specific for BRAF-mutated and BRAF wt CRC patients. a Representative histologic analysis of patient’s tissues revealing a serrated architecture and the presence of dysplasia in BRAFV600E CRCs (top) and traditional adenocarcinoma features in BRAF wt cases (bottom). Bar, 100um and 50um. b Age (top) and BMI (bottom) distribution in CRC and healthy subjects (n = 15 BRAF wt, 8 BRAFV600E CRC, 13 healthy subjects), Mann-Whitney test. c Rarefaction curve for the analysis of microbial species content in healthy, BRAFV600E and BRAF wt CRC cases. d A-diversity (Shannon index; left) and richness (right) of the three groups of subjects at the genus (top) and species (bottom) level. P values are from Kruskal-Wallis tests. e Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes ratio in the three groups of subjects. ** P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Data are mean ± SEM

Strikingly, when comparing the gut microbiota’s signatures between CRC groups and healthy subjects, typical CRC-associated taxa emerged, being samples from BRAFV600E patients closer to controls than BRAF wt (Fig. 7a-b and Supplementary Table S4). Significant differences among the three cohorts were found as for the relative abundance of Firmicutes phylum, highly represented in controls (54.6%) as compared to BRAFV600E (45%) and BRAF wt (41.5%) cases (FDR = 0.01, Kruskal-Wallis test), and Bacteroidetes, whose abundance was higher in BRAF wt (45%) vs BRAFV600E (40%) and controls subjects (34%) (FDR = 0.02). In line with Fig. 3d, the ratio between Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes phyla was comparable between BRAFV600E and healthy subjects, while in BRAF wt cases was significantly lower (Fig. 6e). Yet, BRAF-mutated patients displayed the highest presence of Fusobacteria (1.2% vs 0.65 and 0.01%, BRAFV600E, BRAF wt and healthy, respectively; FDR = 0.01) and Tenericutes (0.61% vs 0.27 and 0.53%; FDR = 0.03). This finding was confirmed at the genus level (Fig. 7b and Supplementary Table S4). Yet, BRAFV600E CRCs exhibited significant richness in Fusobacterium (1.2% vs 0.6 and 0.003%, BRAFV600E, BRAF wt and healthy, respectively; FDR = 0.05), reported to inhibit T cell-mediated immune response and to promote serrated carcinogenesis [27], and the lowest contribution in Bacteroides and Proteus (0.165% vs 0.002 and 0.016%; FDR = 0.03). Down at the species level (Fig. 7c and Supplementary Table S4), the highest presence of Hungateiclostridium saccincola was peculiar of BRAF-mutated samples (FDR = 0.04), while Bacteroides ovatus and Clostridium hiranois were characteristic of BRAF wt cases (FDR = 0.02 and FDR = 0.05).

Fig. 7.

Identification of bacterial markers discriminating BRAF status in CRC patients. a-b Relative abundance of bacterial phyla (a) and genera (b) in fecal microbiota of healthy, BRAFV600E and BRAF wt subjects. c Heatmap of one-way hierarchical clustering of differentially represented species among the three cohorts (q-values < 0.10 from Mann-Whitney test). A dual-color code counts for species up- (red) and down-represented (blue), respectively. d Differences in the relative abundances of Hungateiclostridium saccincola (Hs), Prevotella enoeca (Pe), Sutterella megalospaeroides (Sum), Victivallales bacterium CCUG44730 (Vb), Prevotella dentalis (Pd) and Stenotrophomonas maltophila (Stm) (top) and Bacteroides dorei (Bd), Bacteroides ovatus (Bo), Lachnoclostridium phocaeense (Lp) and Ruthenibacterium lactatiformans (Rl) (bottom) markers in BRAF-mutated vs. BRAF wt CRC counterpart. P values from Mann-Whitney test are shown. e Differences in the relative abundance of predicted function for specific KEGG modules (level 2) in pairwise comparisons between healthy and BRAFV600E (top) or BRAF wt subjects (middle) and between BRAFV600E and BRAF wt CRC cases (bottom). q values are from Mann-Whitney test. f-g Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for the single metagenomic classifiers Pe or Rl (f) and for the combination of the 10 markers Hs, Pe, Sum, Vb, Pd, Stm, Bd, Bo, Lp and Rl (g) in discriminating BRAF-mutated from BRAF wt CRC cases

Moreover, gut microbiota analysis in pairwise comparisons between healthy and CRC subjects, revealed that Prevotella intermedia (2.15% vs 0.005%) and Sutterella megalosphaeroides (0.13% vs 0.03%) were enriched in BRAF-mutated cases (FDR = 0.2 and FDR = 0.2, Mann-Whitney test), whereas higher abundance of Clostridium hiranois was retrieved in BRAF wt CRCs (0.4% vs 0.0004%; FDR = 0.01).

Yet, when BRAFV600E and BRAF wt cases were compared to each other, two Bacteroides species, along with Prevotella enoeca (Pe) (0.158% vs 0.006%, BRAFV600E vs BRAF wt, respectively) and Prevotella dentalis (Pd) (0.75% vs 0.01%), together with Hungateiclostridium saccincola (Hs) (0.2% vs 0.017%), Sutterella megalosphaeroides (Sum) (0.13% vs 0.07%), Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (Stm) (0.175% vs 0.07%) and Victivallales bacterium CCUG44730 (Vb) (0.22% vs 0.06%) emerged overrepresented in BRAFV600E CRC, whereas Bacteroides dorei (Bd) (1.17% vs 7%, BRAFV600E vs BRAF wt, P = 0.007, FDR = 0.2, Mann-Whitney test), Bacteroides ovatus (Bo) (0.4% vs 2.2%), Ruthenibacterium lactatiformans (Rl) (0.6% vs 1.25%, P = 0.02, FDR = 0.4) and Lachnoclostridium phocaeense (Lp) (0.1% vs 0.3%), were enriched in BRAF wt cases.

When the relative abundance of functional category of CRC cases was compared to healthy subjects, according to the level 2 and 3 KEGG modules, samples from BRAFV600E CRC were confirmed to be closer to controls than BRAF wt CRC ones (Fig. 7e and Supplementary Table S5), perfectly matching data in Fig. 4e. When comparing the abundance of predictive function between BRAFV600E and BRAF wt CRCs, translation (P = 0.02, FDR = 0.13) and cell growth and death (P = 0.03, FDR = 0.13) categories were significantly enriched in the former, whereas metabolic functions were overrepresented in the latter (Fig. 7e). Several functions of the genetic information processing category, including mismatch repair, ribosome and aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis were significantly highly expressed in BRAFV600E vs BRAF wt cases, in which several functions of the metabolism, transport and catabolism categories were found, such as starch and sucrose, amino and nucleotide sugar metabolism and pentose phosphate pathway (Supplementary Table S5).

All of these data confirm that a distinctive microbiota’s fingerprint can be distinguished between serrated BRAFV600E and BRAF wt CRC’s patients, with the former strongly resembling healthy subjects.

Potential predictive biomarkers of BRAF status in CRC patients

We finally tested the predictive potential of the bacterial markers differentially represented in the two CRC groups to discriminate between BRAF-mutated and BRAF wt patients [22, 41, 42]. Among the 10 candidate species detected (Fig. 7d), Rl and Pe emerged as single factor with the best performance in discriminating BRAF status, as quantified by the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) of 0.74 and 0.72 (95% confidence interval, 0.53–0.95 and 0.51–0.93, respectively) (Fig. 7e). Performing ROC analysis at the best cut-off value that maximized the sum of sensitivity and specificity, Pe discriminated CRC patients based on their BRAF status with a sensitivity of 73%, specificity of 87.5%, negative predictive value (NPV) of 64% and positive predictive value (PPV) of 92% (P-value = 0.66, Fisher’s Exact Test, 95% confidence interval), while Rl showed a sensitivity of 47%, specificity of 100%, negative predictive value (NPV) of 50% and positive predictive value (PPV) of 100% (P-value = 0.62, Fisher’s Exact Test, 95% confidence interval). Strikingly, as depicted by the AUROC of 0.85 (95% confidence interval, 0.69–1.01) in Fig. 7f, the combination of all the 10 fecal markers reached a better performance in distinguish BRAFV600E subjects, with a sensitivity of 73.3%, specificity of 87.5%, NPV of 63.6% and PPV of 91.7% (P-value = 0.026, Fisher’s Exact Test, 95% confidence interval).

Findings so far demonstrate that 10 candidate bacterial markers can discriminate BRAF status in CRC’s patients, representing new opportunities for the improvement of non-invasive identification and diagnosis of BRAFV600E cases.

Discussion

In this work, we provided the unprecedent findings that BRAFV600E CRC subjects, who did not undergo any type of treatment, might be discriminated from the other CRC’s cases in terms of their microbial composition, being closer to healthy condition than BRAF wild-type cases. These findings were observed in BRAFV600E CRC-bearing mice (Figs. 3 and 4 and Supplementary Table S2-S3), and, most important, confirmed in BRAFV600E CRC patients (Figs. 6 and 7 and Supplementary Table S4-S5), pointing out that our in vivo model of serrated CRC recapitulates the main features of human disease.

We first analyzed gut microbial profile in terms of diversity and richness in CRC cases versus healthy controls and, in agreement with previous studies [43, 44], we found that BRAF wt cases, whether they were mice or patients, displayed lower a-diversity and richness (Fig. 3 and 6 a-b and c-d). Otherwise, these differences were not observed in BRAF-mutated subjects, which almost behave the same way as controls also in terms of Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio, whose deviation is considered a hallmark of gut dysbiosis (Fig. 3 and 6d and e) [40]. Indeed, the down-representation of Firmicutes phylum observed in mice carrying BRAF wt CRCs, might also reflect the depletion of many “good” butyrate-producing bacterial families, such as Clostridiales, Eubacteriaceae, Lachnospiraceae, and Streptococcaceae, characterized by anti-inflammatory, immunoregulatory and metabolic functions [45, 46]. Importantly, as regards the molecular and functional microbiota composition over time, although numerous differences were detected at the beginning of the disease in both of the two groups of CRC-carrying mice versus control, only BRAFV600E CRCs resembled healthy mice at the end-stage of the disease (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table S2). Although the healthy status mirrored by BRAFV600E is yet to be elucidated, our hypothesis is that the microbiota shift of BRAF-mutant CRC might be strongly related to the peculiar molecular profile of this tumor [6, 11, 38, 39]. Yet, one of the most relevant aspect emerging from the delineation of BRAFV600E CRC’s microbiota profile, is likely found in the intriguing demonstration that several correlations do exist between bacterial genera abundance ad genes typically involved in the BRAFV600E pathway (Fig. 5a). As expected, a positive trend of correlation for genes driving inflammation, innate immunity and invasion processes, mostly up-regulated in the BRAF-mutated pathway, was shown, whereas the typically down-regulated CDX2 and Wnt target genes, displayed a negative trend [6, 11, 38, 39]. Furthermore, when comparing microbiota functional composition of BRAF-mutated versus wild-type counterpart a decrease in microbiota-associated metabolic functions was predicted (Figs. 4 and 7), thus confirming the capability of gut microbes to affect tumor through their metabolic functions, beside their impact on host immune and inflammatory responses [44]. These data not only suggested the existence of a bidirectional crosstalk whereby tumor impinge on gut microbiota and the microbiota influence tumor progression but also that a distinctive microbial fingerprint might be sustained by BRAFV600E mutation itself. It is increasingly evident that microbial equilibrium plays a fundamental role in human health, since dysbiosis can contribute to or even initiate CRC development, through several mechanisms including triggering of a chronic inflammatory state, production of reactive oxygen species, genotoxins and carcinogenic compounds, interference with host immunity and metabolism [47, 48]. It should be noted, however, that the vast majority of investigation, addressed so far, concerned the role of gut microbiota in conventional CRC, whereas the few reports about the serrated-CRC mainly focused on the presence of F. nucleatum.

We demonstrated that, both in mice and in humans, BRAF-mutated CRC is characterized by a gut microbiota which, compared to conventional CRC, is more resembling to but still remains different from that of healthy subjects. This result was supported by previous findings by Peters et al., [26] in which conventional adenomas (precursor lesions of conventional CRC) but not SSAs (precursor lesions of the serrated pathway) were reported to display lower bacterial communities’ richness and diversity and a drop in butyrate-producing bacteria as compared to controls [26]. The reason why serrated BRAF mut CRC is associated to a more eubiotic condition is still to be clarified. One hypothesis is that gut dysbiosis may play a role only in the development of conventional CRC [25, 26], but not in the BRAF-mutated serrated one), which is also genetically, epigenetically, and molecularly different from the former. Nevertheless, we observed a positive correlation between bacterial genera found in BRAF mut microbiota and genes involved in inflammation, immunity and invasion processes typically expressed in the BRAF-mutated pathway. Another possible speculation is that, despite a microbiota composition generally resembling to that of healthy status, few or even single microorganisms (e.g. F. nucleatum) in the gut of BRAF mut CRC carriers might be sufficient to drive that specific carcinogenetic pathway.

Focusing on the microbiota composition of CRC patients enrolled in our study, an increased abundance of Fusobacteria in either BRAF-mutated or wild-type cases compared with controls emerged [27, 49]. Likewise, among the bacteria distinctive of each CRC group down at the species level, Prevotella enoeca and Prevotella dentalis were significantly enriched in patients harboring BRAFV600E mutation (Fig. 7c-d), likely reflecting their massive presence in the biofilm lining the colonic mucosa [50]. Strikingly, as single factor, Prevotella enoeca together with Ruthenibacterium lactatiforman, overrepresented in BRAF wt cases, emerged as the species best discriminating BRAF status in CRC patients, therefore putative candidate non-invasive biomarkers (Fig. 7f). Furthermore, when considering the combination of all the 10 bacterial species differentially represented between the two CRC groups a best performance as a biomarker signature distinguishing BRAFV600E from BRAF wt cases was reached, thus identifying potential diagnostic fecal biomarkers for CRC patients (Fig. 7g).

Thus, our work opens new and exciting possibilities for studying the biological underpinnings of the serrated BRAFV600E CRCs and, most important, for the development of innovative diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for the cure of this deadly tumor.

Conclusions

In the present study, we provide the unprecedented findings, observed in xenogeneic BRAFV600E CRC and, most important, confirmed in patients harbouring BRAF mutation, that a distinctive microbiota profile could distinguish BRAF-mutated cases among CRCs. BRAFV600E mutation drives itself a distinctive gut microbiota fingerprint in CRC, suggesting the existence of a bidirectional Tumor-Microbiota-Tumor connection. We identify a bacterial marker signature discriminating BRAF status in CRC patients, thus acting as reliable novel non-invasive clinical biomarkers for patient-tailored diagnostic and therapeutic applications.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:. Supplementary methods

Additional file 2: Supplementary Table S1. Relative bacterial abundance at the phylum, genus and species level in fecal microbiota of mice at 7 DPT.

Additional file 3: Supplementary Table S2. Relative bacterial abundance at the phylum, genus and species level in fecal microbiota of mice at 43 DPT.

Additional file 4: Supplementary Table S3. Relative abundance of predicted function for specific KEGG modules (level 1–3) in fecal microbiota of mice at 43 DPT.

Additional file 5: Supplementary Table S4. Relative bacterial abundance at the phylum, genus and species level in fecal microbiota of human subjects.

Additional file 6: Supplementary Table S5. Relative abundance of predicted function for specific KEGG modules (level 1–3) in fecal microbiota of human subjects.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Lucia Sergisergi for kindly providing the luciferase lentivirus and to Maria Teresa Pellico for performing NGS analyses on patient’s samples.

Abbreviations

- CRC

Colorectal carcinoma

- CCSCs

Colorectal carcinoma stem-like cells

- BRAF wt

BRAF wild-type

- PDX

Patient derived xenograft

- DPT

Days post transplantation

- PCoA

Principle coordinates analysis

- FDR

False discovery rate

- KEGG

Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genome

- NPV

Negative predictive value

- PPV

Positive predictive value

- AUROC

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

- Pe

Prevotella enoeca

- Pd

Prevotella dentalis

- Hs

Hungateiclostridium saccincola

- Sum

Sutterella megalosphaeroides

- Stm

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia

- Vb

Victivallales bacterium CCUG44730

- Bd

Bacteroides dorei

- Bo

Bacteroides ovatus

- Rl

Ruthenibacterium lactatiformans

- Lp

Lachnoclostridium phocaeense

Authors’ contributions

EB designed experiments and supervised the study. EB, VP conceived the study, interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. ALV, CP contributed to the original draft. EB, NT, MGC, PC, PP, AAS, CB, AV, FG collected mice fecal and performed data collection. EB, RP, VP performed bioinformatics and statistical analyses. GC, TL, FB, DC, LD, PP collected patient fecal and provided the clinical information. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by grants from “Ministero della Salute Italiano” (GR-2011-02351534 and Progetto Ricerca Corrente 2018–20) to EB. The research leading to these results has received also funding from AIRC under IG 2019-ID. 23006 project - P.I. Pazienza Valerio and under IG 2018-ID. 22027 project – P.I. Vescovi Angelo.

Availability of data and materials

Raw 16S rRNA sequencing data of all samples and raw Transcriptome array sequencing data were deposited in the Arrayexpress repository under accession code n. E-MTAB-9130 and n. E-MTAB-6940, respectively.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Patients with a confirmed diagnosis of CRC and healthy subjects included in the control group were enrolled in this study at IRCCS “Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza” Hospital, under the Ethical committee approvals number N.175/CE and N.94/CE. All the subjects agreed to participate according to the ethical guidelines of the 2013 Declaration of Helsinki and signed an informed consent for samples and anonymized information to be used. All the experimental procedures for the in vivo mice studies have been approved by the Ministry of Health (PR/15–297/2019-PR).

Consent for publication

All authors have seen and approved the manuscript and consent publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests. ALV has ownership interest in Stemgen Spa.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Valerio Pazienza and Elena Binda these authors are share senior authorship.

Nadia Trivieri and Riccardo Pracella contributed equally.

References

- 1.Brenner H, Kloor M, Pox CP. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2014;383(9927):1490–1502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61649-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Song M, Garrett WS, Chan AT. Nutrients, foods, and colorectal cancer prevention. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(6):1244–1260. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Network CGA. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487(7407):330–337. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guinney J, Dienstmann R, Wang X, de Reynies A, Schlicker A, Soneson C, et al. The consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Nat Med. 2015;21(11):1350–1356. doi: 10.1038/nm.3967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Cancer genes and the pathways they control. Nat Med. 2004;10(8):789–799. doi: 10.1038/nm1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Sousa EMF, Wang X, Jansen M, Fessler E, Trinh A, de Rooij LP, et al. Poor-prognosis colon cancer is defined by a molecularly distinct subtype and develops from serrated precursor lesions. Nat Med. 2013;19(5):614–618. doi: 10.1038/nm.3174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patai AV, Molnar B, Tulassay Z, Sipos F. Serrated pathway: alternative route to colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(5):607–615. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i5.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ensari A, Bosman FT, Offerhaus GJ. The serrated polyp: getting it right! J Clin Pathol. 2010;63:665–668. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2010.077222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leggett B, Whitehall V. Role of the serrated pathway in colorectal cancer pathogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(6):2088–2100. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noffsinger AE. Serrated polyps and colorectal cancer: new pathway to malignancy. Annu Rev Pathol. 2009;4:343–364. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sakamoto N, Feng Y, Stolfi C, Kurosu Y, Green M, Lin J, et al. BRAF(V600E) cooperates with CDX2 inactivation to promote serrated colorectal tumorigenesis. Elife. 2017;6:1–25. doi: 10.7554/eLife.20331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakanishi Y, Diaz-Meco MT, Moscat J. Serrated colorectal Cancer: the road less travelled? Trends Cancer. 2019;5(11):742–754. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2019.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ursem C, Atreya CE, Van Loon K. Emerging treatment options for BRAF-mutant colorectal cancer. Gastrointest Cancer. 2018;8:13–23. doi: 10.2147/GICTT.S125940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Sousae Melo F, Kurtova AV, Harnoss JM, Kljavin N, Hoeck JD, Hung J, et al. A distinct role for Lgr5(+) stem cells in primary and metastatic colon cancer. Nature. 2017;543(7647):676–680. doi: 10.1038/nature21713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ricci-Vitiani L, Lombardi DG, Pilozzi E, Biffoni M, Todaro M, Peschle C, et al. Identification and expansion of human colon-cancer-initiating cells. Nature. 2007;445(7123):111–115. doi: 10.1038/nature05384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Visioli A, Giani F, Trivieri N, Pracella R, Miccinilli E, Cariglia MG, et al. Stemness underpinning all steps of human colorectal cancer defines the core of effective therapeutic strategies. EBioMedicine. 2019;44:346–360. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dai Z, Coker OO, Nakatsu G, Wu WKK, Zhao L, Chen Z, et al. Multi-cohort analysis of colorectal cancer metagenome identified altered bacteria across populations and universal bacterial markers. Microbiome. 2018;6(1):70. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0451-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iida N, Dzutsev A, Stewart CA, Smith L, Bouladoux N, Weingarten RA, et al. Commensal bacteria control cancer response to therapy by modulating the tumor microenvironment. Science. 2013;342(6161):967–970. doi: 10.1126/science.1240527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng Q, Liang S, Jia H, Stadlmayr A, Tang L, Lan Z, et al. Gut microbiome development along the colorectal adenoma-carcinoma sequence. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6528. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tilg H, Adolph TE, Gerner RR, Moschen AR. The intestinal microbiota in colorectal Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2018;33(6):954–964. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Panebianco C, Andriulli A, Pazienza V. Pharmacomicrobiomics: exploiting the drug-microbiota interactions in anticancer therapies. Microbiome. 2018;6(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0483-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wirbel J, Pyl PT, Kartal E, Zych K, Kashani A, Milanese A, et al. Meta-analysis of fecal metagenomes reveals global microbial signatures that are specific for colorectal cancer. Nat Med. 2019;25(4):679–689. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0406-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arthur JC, Gharaibeh RZ, Mühlbauer M, Perez-Chanona E, Uronis JM, McCafferty J, et al. Microbial genomic analysis reveals the essential role of inflammation in bacteria-induced colorectal cancer. Nat Commun. 2014;5(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allen J, Sears CL. Impact of the gut microbiome on the genome and epigenome of colon epithelial cells: contributions to colorectal cancer development. Genome Med 2019;11(1):1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Yoon H, Kim N, Park JH, Kim YS, Lee J, Kim HW, et al. Comparisons of gut microbiota among healthy control, patients with conventional adenoma, sessile serrated adenoma, and colorectal Cancer. J Cancer Prev. 2017;22(2):108–114. doi: 10.15430/JCP.2017.22.2.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peters BA, Dominianni C, Shapiro JA, Church TR, Wu J, Miller G, et al. The gut microbiota in conventional and serrated precursors of colorectal cancer. Microbiome. 2016;4(1):69. doi: 10.1186/s40168-016-0218-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park CH, Han DS, Oh YH, Lee AR, Lee YR, Eun CS. Role of Fusobacteria in the serrated pathway of colorectal carcinogenesis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25271. doi: 10.1038/srep25271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Binda E, Visioli A, Giani F, Trivieri N, Palumbo O, Restelli S, et al. Wnt5a drives an invasive phenotype in human Glioblastoma stem-like cells. Cancer Res. 2017;77(4):996–1007. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Binda E, Visioli A, Giani F, Lamorte G, Copetti M, Pitter KL, et al. The EphA2 receptor drives self-renewal and tumorigenicity in stem-like tumor-propagating cells from human glioblastomas. Cancer Cell. 2012;22(6):765–780. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galli R, Binda E, Orfanelli U, Cipelletti B, Gritti A, De Vitis S, et al. Isolation and characterization of tumorigenic, stem-like neural precursors from human glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2004;64(19):7011–7021. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Youden WJ. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer. 1950;3(1):32–35. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1950)3:1<32::AID-CNCR2820030106>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wood DE, Lu J, Langmead B. Improved metagenomic analysis with kraken 2. Genome Biol. 2019;20(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1891-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7(5):335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Langille MGI, Zaneveld J, Caporaso JG, McDonald D, Knights D, Reyes JA, et al. Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(9):814–821. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parks DH, Tyson GW, Hugenholtz P, Beiko RG. STAMP: statistical analysis of taxonomic and functional profiles. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(21):3123–3124. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pasolli E, Truong DT, Malik F, Waldron L, Segata N. Machine learning meta-analysis of large metagenomic datasets: tools and biological insights. PLoS Comput Biol. 2016;12(7):e1004977. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jass JR. Classification of colorectal cancer based on correlation of clinical, morphological and molecular features. Histopathology. 2007;50(1):113–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fessler E, Drost J, van Hooff SR, Linnekamp JF, Wang X, Jansen M, et al. TGFbeta signaling directs serrated adenomas to the mesenchymal colorectal cancer subtype. EMBO Mol Med. 2016;8(7):745–760. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201606184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murakami T, Mitomi H, Saito T, Takahashi M, Sakamoto N, Fukui N, et al. Distinct WNT/ β -catenin signaling activation in the serrated neoplasia pathway and the adenoma-carcinoma sequence of the colorectum. Mod Pathol. 2014;28(1):146–158. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2014.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mori G, Rampelli S, Orena BS, Rengucci C, Maio GD, Barbieri G, et al. Shifts of Faecal microbiota during sporadic colorectal carcinogenesis. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17765-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zeller G, Tap J, Voigt AY, Sunagawa S, Kultima JR, Costea PI, et al. Potential of fecal microbiota for early-stage detection of colorectal cancer. Mol Syst Biol. 2014;10:766. doi: 10.15252/msb.20145645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liang Q, Ma D, Zhu X, Wang Z, Sun TT, Shen C, et al. RING-finger protein 6 amplification activates JAK/STAT3 pathway by modifying SHP-1 Ubiquitylation and associates with poor outcome in colorectal Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(6):1473–1485. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ahn J, Sinha R, Pei Z, Dominianni C, Wu J, Shi J, et al. Human gut microbiome and risk for colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(24):1907–1911. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bhatt AP, Redinbo MR, Bultman SJ. The role of the microbiome in cancer development and therapy. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(4):326–344. doi: 10.3322/caac.21398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ryu SH, Kaiko GE, Stappenbeck TS. Cellular differentiation: Potential insight into butyrate paradox? Mol Cell Oncol. 52018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Canani RB, Costanzo MD, Leone L, Bedogni G, Brambilla P, Cianfarani S, et al. Epigenetic mechanisms elicited by nutrition in early life. Nutr Res Rev. 2011;24(2):198–205. doi: 10.1017/S0954422411000102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mangifesta M, Mancabelli L, Milani C, Gaiani F, de Angelis N, de Angelis GL, et al. Mucosal microbiota of intestinal polyps reveals putative biomarkers of colorectal cancer. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):13974. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-32413-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gagnière J, Raisch J, Veziant J, Barnich N, Bonnet R, Buc E, et al. Gut microbiota imbalance and colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(2):501–518. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i2.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ito M, Kanno S, Nosho K, Sukawa Y, Mitsuhashi K, Kurihara H, et al. Association of Fusobacterium nucleatum with clinical and molecular features in colorectal serrated pathway. Int J Cancer. 2015;137(6):1258–1268. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sideris M, Adams K, Moorhead J, Diaz-Cano S, Bjarnason I, Papagrigoriadis S. BRAF V600E mutation in colorectal cancer is associated with right-sided tumours and iron deficiency anaemia. Anticancer Res. 2015;35(4):2345–2350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1:. Supplementary methods

Additional file 2: Supplementary Table S1. Relative bacterial abundance at the phylum, genus and species level in fecal microbiota of mice at 7 DPT.

Additional file 3: Supplementary Table S2. Relative bacterial abundance at the phylum, genus and species level in fecal microbiota of mice at 43 DPT.

Additional file 4: Supplementary Table S3. Relative abundance of predicted function for specific KEGG modules (level 1–3) in fecal microbiota of mice at 43 DPT.

Additional file 5: Supplementary Table S4. Relative bacterial abundance at the phylum, genus and species level in fecal microbiota of human subjects.

Additional file 6: Supplementary Table S5. Relative abundance of predicted function for specific KEGG modules (level 1–3) in fecal microbiota of human subjects.

Data Availability Statement

Raw 16S rRNA sequencing data of all samples and raw Transcriptome array sequencing data were deposited in the Arrayexpress repository under accession code n. E-MTAB-9130 and n. E-MTAB-6940, respectively.