Abstract

The limit of viability for premature newborns has changed in recent decades, but whether to initiate or withhold active care for periviable infants remains a subject of debate because the chances of survival and the extent of severe neurological impairment can be unclear. In our review, we analyzed large population-based studies of periviable infants from the past 2 decades. We compared survival rates and the incidence of early complications among survivors, including bronchopulmonary dysplasia, intraventricular hemorrhage, periventricular leukomalacia, retinopathy of prematurity, and necrotizing enterocolitis. Moreover, we assessed the perinatal factors that may affect the survival of preterm infants. We analyzed 15 studies reporting data on preterm infants born between 22 and 28 gestational weeks. None of these studies reported survival of an infant born before 22 gestational weeks. Survival rates of infants born at 24 weeks’ gestation were above 50% in most studies. The incidence of each complication was also higher among infants born at ≤24 weeks. Of the analyzed perinatal factors, antenatal corticosteroid therapy, birth weight, female sex, cesarean delivery, singleton pregnancy, and birth in a tertiary-level Neonatal Intensive Care Unit were found to be associated with improved survival in some studies. The different methodologies of the studies limited comparison of the results. Further investigations are needed to gain up-to-date information on the limit of viability, and standardized methods in future studies would enable more accurate comparisons of findings.

MeSH Keywords: Fetal Viability; Infant, Extremely Low Birth Weight; Infant, Extremely Premature; Premature Birth

Background

The legal definition of viability centers on the ability of the fetus to survive outside the uterus after birth when supported by the most advanced medical care. This definition does not consider the chances of survival or the individual’s quality of life; hence, it is essential to know the limit at which a preterm infant has a significant chance to survive without severe neurological impairment [1]. This second consideration, in contrast to the legal definition of viability, raises numerous questions. What does significant chance mean? Is there an exact percentage for it? What constitutes severe neurological impairment? Currently, these questions have no widely accepted answers.

A gray zone of viability lies between these 2 approaches. The care of neonates born within this gray zone represents a major moral and ethical dilemma for perinatal health care providers. The care of these infants is regulated differently depending on the culture and society. In some countries, the line between initiating or withholding intensive care is clear, while in other countries, parents are involved in the decisions [2,3].

Multiple population-based studies have been conducted to define the viability of extremely preterm infants, and the definition has changed over time. Since 1980, the limit of viability has shifted from 28 to 22–24 weeks of gestational age. Updated information on the possible outcomes for these infants is crucial to make the best therapeutic decisions for their care.

Our aim was to review studies of periviable infants published over the last 20 years that reported survival rates and the incidence of complications (Table 1). Most of these population-based studies had large samples, and we assessed the perinatal factors that can affect the survival of extremely preterm infants.

Table 1.

Selected large population-based studies on extremely preterm infants.

| Study | Country/State | Years of the study | Gestational age | The number of all infants | The number of actively treated infants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPIBEL [4] | Belgium | 1999–2000 | 22–26 | 525 | 303 |

| NEPS1 [16] | Norway | 1999–2000 | 22–27 | 638 | 464 |

| NEPS2 [17] | Norway | 2013–2014 | 22–26 | 275 | 251 |

| Kugelman [7] | Israel | 1995–2008 | 23–26 | 4408 | – |

| Agarwal [8] | Singapore | 2000–2009 | 23–28 | – | 887 |

| EPICURE [18] | UK | 2006 | 22–26 | 3133 | 1686 |

| EXPRESS [10] | Sweden | 2004–2007 | 22–26 | – | 707 |

| Ishii [11] | Japan | 2003–2005 | 22–25 | – | 1057 |

| Doyle [12] | Victoria State (Australia) | 2005 | 22–27 | – | 270 |

| Su [13] | Taiwan | 2007–2012 | 23–28 | – | 1718 |

| EPIPAGE-2 [5] | France | 2011 | 22–26 | – | 1054 |

| Stoll [14]* | USA | 2008–2012 | 22–28 | – | 8877 |

| Anderson [6] | California | 2007–2011 | 22–28 | 6009 | 5340 |

| EPI-SEN [15]* | Spain | 2007–2011 | 22–26 | 2937 | 2734 |

| Fischer [9] | Swiss | 2000–2004 | 22–25 | 516 | – |

These studies were divided to several periods.

Data were reviewed only from the last period (shown in the table) of these studies.

Survival Rate According to Gestational Age

The different designs of the studies limited the comparison of survival rates. Six studies reported the survival rate in the proportion of all preterm infants [4–9], while 6 other studies focused on the survival rate of infants receiving care in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) [10–15]. Three studies reported survival rates in both groups [16–18]. In the EPIBEL study [4], infants who were transported from lower-level care to a tertiary-level NICU after birth were excluded; in a Californian study [6] and the EPI-SEN study [15], neonates with major congenital malformations were excluded.

Data on preterm infants born at 22 weeks were not obtained in 3 studies [7,8,13], 4 publications reported no survivors among infants at 22 weeks’ gestation [4,5,9,16], and 4 studies found a survival rate lower than 10% [6,10,12,14]. Analyzing data on infants born at 23 weeks’ gestation, 9 studies reported survival rates lower than 30% [4–9,12,13,15]. Studies analyzing the survival rate of preterm infants among infants treated in the NICU found ≥10% survival rate at 22 weeks [11,15,17,18] and ≥30% survival rate at 23 weeks [10,11,14,16–18].

Among infants born at 24 weeks’ gestation, 9 studies found at least 50% survival [6,8,10–14,16,17], while in 6 reports, survival did not reach 50% [4,5,7,9,15,18]. All studies except for one [7] demonstrated a survival rate above 50% among neonates at 25 weeks’ gestational age, and 7 studies found a rate above 75% [6,8,10,11,14,16,17]. Data on infants at 26 weeks’ gestation showed more than 70% survival in all studies, and 8 studies revealed a proportion above 80% [6,8,10,12–14,16,17]. All 6 reports analyzing 27-week infants found ≥88% survival rate [6,8,12–14,16]. All 4 studies assessing infants at 28 weeks showed more than 90% survival [6,8,13,14]. In most studies, more than 90% of infants who were born >24 weeks received active medical treatment (Table 2).

Table 2.

Survival rates of extremely preterm infants by gestational age.

| Study | All infants/Infants who received intensive care | Survival rates (%) by gestational age (week) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22. | 23. | 24. | 25. | 26. | 27. | 28. | ||

| EPIBEL [4] | All | 0 | 5.5 | 29.2 | 55.5 | 71.4 | – | – |

| NEPS1 [16] | All | 0 | 16 | 44 | 66 | 72 | 82 | – |

| NEPS1 [16] | Intensive care | 0 | 39 | 60 | 80 | 84 | 93 | – |

| NEPS2 [17] | All | 18 | 29 | 56 | 84 | 90 | – | – |

| NEPS2 [17] | Intensive care | 60 | 35 | 58 | 86 | 92 | – | – |

| EPICURE [18] | All | 2 | 19 | 40 | 66 | 77 | – | – |

| EPICURE [18] | Intensive care | 15.8 | 30.4 | 46.4 | 69.4 | 78.4 | – | – |

| Kugelman [7] | All | – | 6.2 | 26.5 | 47.4 | 70.1 | – | – |

| Agarwal [8] | All | – | 19 | 57 | 79 | 86 | 91 | 93 |

| EXPRESS [10] | Intensive care | 9.8 | 53 | 67 | 82 | 85 | – | |

| Ishii [11] | Intensive care | 36 | 62.9 | 77.1 | 85.2 | – | – | – |

| Doyle [12] | Intensive care | 5 | 22 | 51 | 67 | 82 | 89 | – |

| Su [13] | Intensive care | – | 22 | 50 | 70 | 84 | 88 | 92 |

| EPIPAGE2 [5] | All | 0 | 1 | 31.2 | 59.1 | 75.3 | – | – |

| Stoll [14] | Intensive care | 7 | 32 | 62 | 77 | 85 | 90 | 94 |

| Anderson [6] | All | 6.4 | 26.9 | 59.8 | 78 | 85.9 | 90.8 | 94 |

| EPI-SEN [15] | Intensive care | 14.3 | 19.9 | 35.9 | 59.7 | 73.3 | – | – |

| Fischer [9] | All | 0 | 5 | 30 | 50 | – | – | – |

These studies were divided to several periods.

Data were reviewed only from the last period (shown in the table) of these studies.

The Role of Perinatal Factors

Many of the large population-based studies assessing neonates born at the threshold of viability analyzed the perinatal risk factors affecting survival [4,6–8,10,16–18]. These factors included antenatal corticosteroid therapy, birth weight, multiple pregnancy, cesarean delivery, and admission to a tertiary-level NICU after birth.

A link between antenatal steroid therapy and survival of preterm infants was demonstrated by 6 studies. Three studies analyzed the data of infants who received complete antenatal steroid treatment [8,17,18], while the other 3 studies reported on infants who were given only a partial course [7,10,16]. Four studies showed lower mortality in infants who received antenatal corticosteroid therapy [7,10,17,18]. Two studies did not find link between survival and antenatal corticosteroid therapy [8,16].

In addition to the analyzed 15 studies, 2 other studies with a large number of infants focused on the association of antenatal steroid corticosteroid use with mortality and complications among infants born at 22–25 weeks’ gestation. Both studies reported lower mortality and higher survival without severe neurological impairment among infants born at 23–25 weeks’ gestation whose mothers were exposed to only to a partial antenatal course. Ehret et al. [19] found lower mortality and higher survival without severe neurological impairment, while Carlo et al. [20] did not find a decrease in either mortality or late neurological impairment among infants at 22 weeks.

Three publications found an association between birth weight and survival [6–8], but 3 other studies did not find a link between these 2 factors [4,16,17]. Three publications noted a higher survival rate among female preterm infants [6,8,18], and 1 study showed higher survival among female infants at 25 to 26 weeks [7]. Four studies did not find a difference between the survival of female and male infants [4,10,16,17]. None of the studies found a significant link between multiple pregnancy and mortality. Tyson et al. [21] found that higher birth weight, female sex, and antenatal steroid therapy were all associated with improved survival, while multiple pregnancies were linked to lower survival.

The benefit of cesarean delivery is controversial [22,23]. Three studies found higher survival rate of infants born by cesarean delivery [4,8,16], and 1 study found a lower rate [18]. One study demonstrated lower mortality in infants at 22–24 weeks born by cesarean delivery and in infants at 25–28 weeks born by vaginal delivery [6]. Three studies did not find a difference in mortality among preterm infants based on method of delivery [10,17,18].

Two studies demonstrated higher survival rates of infants born in a regional- or tertiary-level NICU [6,10] and 1 study did not [4].

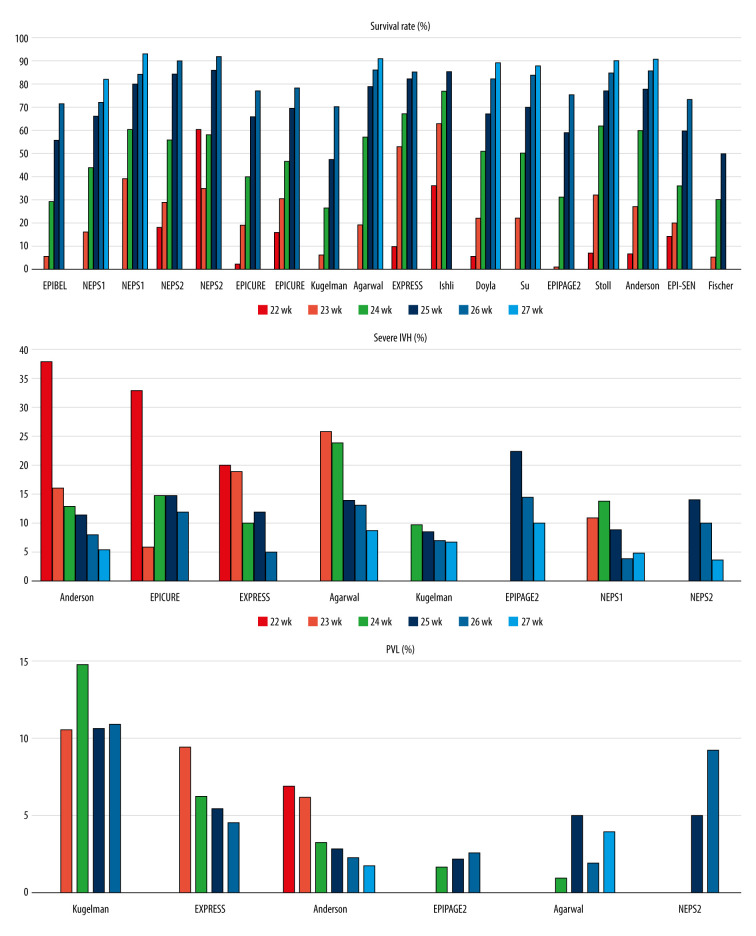

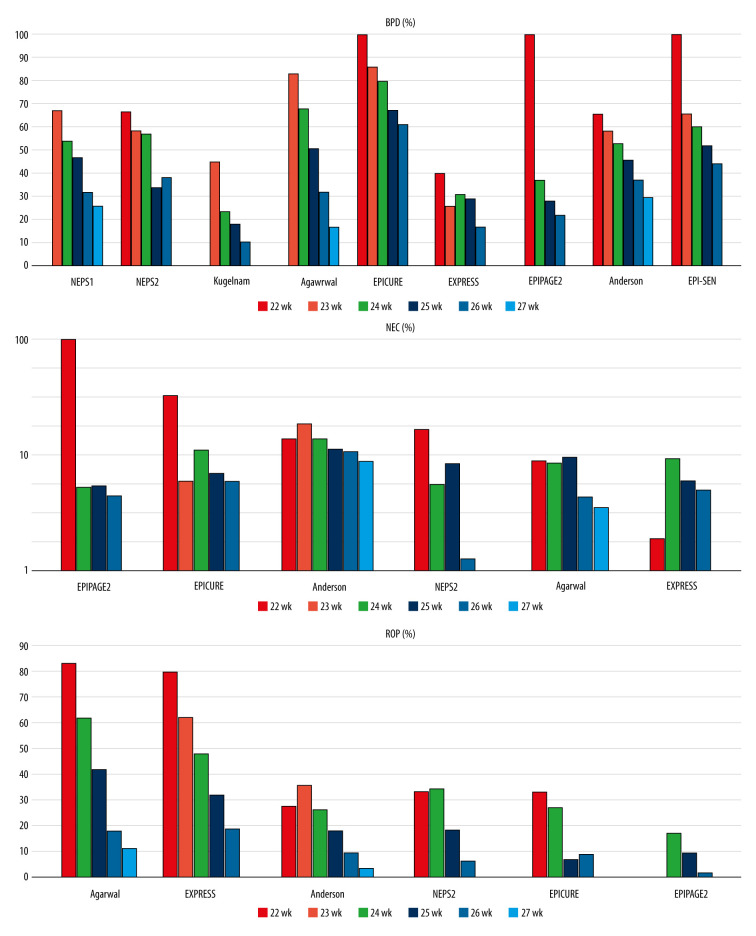

Morbidity According to Gestational Age (Figures 1, 2)

Figure 1.

Survival, severe intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), and periventricular leukomalacia (PVL) rates by gestational age in the reviewed studies.

Figure 2.

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), and retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) rates by gestational age in the reviewed studies.

Maturity at birth plays an essential role not only in survival, but also in neonatal complications. In some studies, morbidity was not reported based on gestational age, which limited the comparison of results between studies. In all publications except one, the incidence of complications was reported only for surviving infants. The exception was a Japanese study [11] that reported complications for all infants; therefore, we could not compare it to the other studies.

Nine studies reported the incidence of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) according to gestational age. Eight studies defined BPD as the use of supplemental oxygen at the postmenstrual age of 36 weeks [5,6,8,10,15–18]. In an Israeli study [7], BPD was defined as the need for oxygen supplementation at 40 weeks’ postmenstrual age. Seven publications reported a rate of BPD > 50% in infants born at <24 weeks [5,6,8,15–18], and 4 other studies found an incidence of >80% [5,8,15,18]. Assessing neonates at >24 weeks’ gestation, 2 studies found a BPD rate that was substantially higher than 50% [15, 18], while BPD rates in 3 studies were below 30% [5,7,10] (Supplementary Table 1).

Eight publications reported the incidence of intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) according to gestational age. Six publications demonstrated only grade 3–4 IVH [5,6,8,10,16,17]. The Israeli study analyzed the rate of grade 4 IVH [7], while the EPICURE study showed the rate of serious abnormalities on cerebral ultrasonography [18]. One study showed a 20% rate of severe IVH at 22 weeks’ gestation [10], and 2 studies reported a rate higher than 30% [6,18]. The proportion of infants born at 23 and 24 weeks’ gestation who had IVH was >15% in 4 studies [5,6,8,10] and ≤15% in 4 other studies [7,16–18]. Among infants at >24 weeks’ gestation, the incidence of severe IVH was not more than 15% in all 8 studies (Supplementary Table 2).

The incidence of periventricular leukomalacia (PVL) by gestational age was published in 6 studies [5–8,10,17]. Cystic PVL can be diagnosed by ultrasonography, while the noncystic form can only be seen on magnetic resonance imaging [24,25]. Four studies analyzed cystic PVL [5,8,10,17], and 2 studies did not specify the diagnostic method of PVL [6,7]. Except for the Israeli study [7], none of the studies reported higher than 10% incidence [5,6,8,10,17] (Supplementary Table 3).

The incidence of retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) by gestational age was reported in 6 publications [5,6,8,10,17,18]. Two studies reported the incidence of ROP treated with laser photocoagulation [6,18], and 4 studies reported stage ≥3 ROP [5,8,10,17]. The rate of ROP treated with laser photocoagulation reached or exceeded 30% in infants at <24 weeks’ gestation, and it was between 20% and 30% at 24 weeks of gestational age. It was <20% at 25 weeks and <10% at 26 weeks, and at 27 weeks of gestational age, it was under 5%. The rates of stage ≥3 ROP were above 60–83% among infants at <24 weeks in the EXPRESS study and a study in Singapore [8,10]. The rate of severe ROP was under 50% in infants at >24 weeks of gestation, and was lower than 20% in infants at >25 weeks of gestation [5,8,10,17] (Supplementary Table 4).

The incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) by gestational age was reported in 6 studies. The EPICURE study showed the rate of surgically treated NEC [18], and the other 5 studies reported stage ≥2 NEC (according to Bell criteria) [5,6,8,10,17]. Differentiating NEC from spontaneous intestinal perforation could be problematic [26,27]. Only 1 study analyzed the incidence of NEC without spontaneous intestinal perforation [8]. Most of the studies showed the rate of stage ≥2 NEC as below 10% and mainly about 5% [5,8,10,17] (Supplementary Table 5).

Discussion

Review limitations

Each study used a different calculation method for survival rates, which hindered comparison between studies [28]. Comparability could have been more accurate if the survival rates were based on the proportion of all preterm infants as well as the proportion of actively treated infants. It would also be important to know whether infants who received active care were only those admitted to NICU or whether this group also included infants who received active treatment in the delivery room but died before NICU admission. In addition, it would be helpful to know the survival rates for infants born in a tertiary center and those who underwent transportation to a tertiary-level NICU. Regarding the comparability of antenatal steroid therapy, it is important to define treatment precisely and differentiate between receiving a complete course of steroid treatment and receiving a partial course.

The incidence of each complication was shown based on the number of surviving infants in most studies; however, the complications themselves were described differently in each study. Most studies reported the complications as follows: BPD as the condition in which infants need oxygen supplementation at 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age, severe stages (≥2–3) of IVH, cystic form of PVL (diagnosed by cranial ultrasound), stage ≥3 ROP, and stage ≥2 NEC.

Future large population-based studies should use a unified methodology in every investigation, which would allow accurate comparisons between investigations [28]. The threshold of viability has changed over the past few decades, and future studies are necessary to observe further changes. Knowing the latest findings is crucial to make the best decisions on the care of preterm infants.

Possible paradox

Out of 15 large population-based studies, none of them reported any survivors among infants born before 22 weeks’ gestation. Most of the studies reported at least 50% survival rate among infants born at 24 weeks. The chance of developing complications was less in infants born after 24 weeks than among those born before 24 weeks. The survival rate without complications was also higher in babies born after 24 weeks.

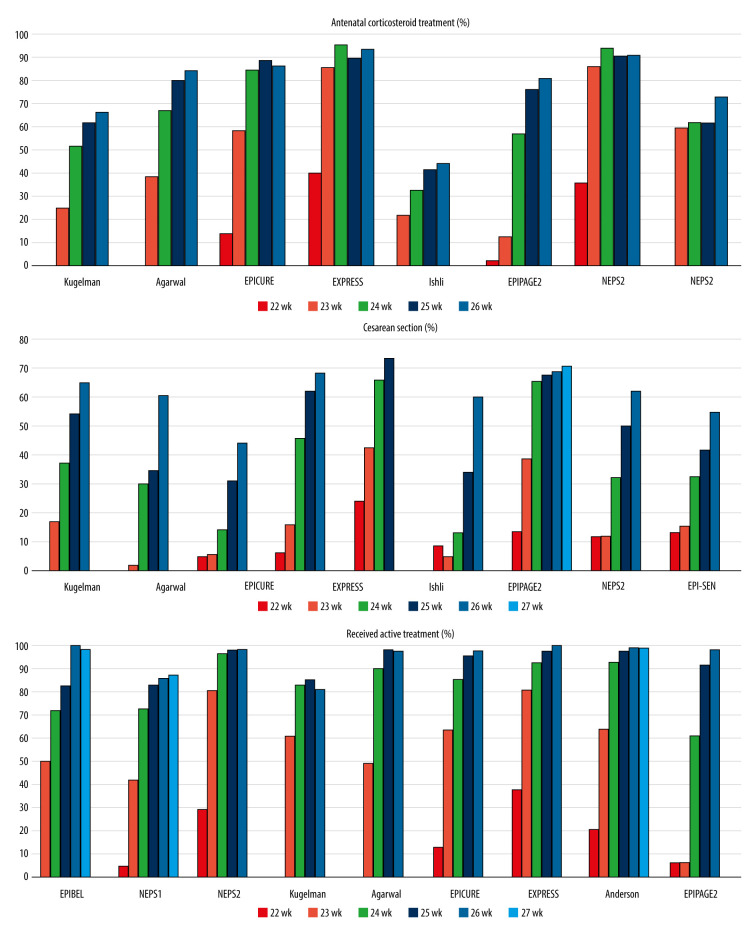

Infants born before 24 weeks’ gestation tended to receive less active care than infants born after 24 weeks’ gestation, which limited the ability to compare outcomes (Figure 3). Antenatal corticosteroid therapy was given to 1.8% to 40% of infants born at 22 weeks, as opposed to 66% to 93% of infants born at 26 weeks [5,7,8,10,11,16–18] (Supplementary Table 6). Infants at 22 weeks were delivered by cesarean delivery in 2% to 24% of cases, while the rate ranged from 44% to 68% for infants at 26 weeks [5–8,10,11,17,18] (Supplementary Table 7). Initiation of intensive care for infants born before 24 weeks varied broadly, with 6% to 81% of the infants receiving intensive care. At 24 weeks’ gestation, preterm babies received active medical care in 60.8% to 96.8% of cases and the rate was beyond 90% when the gestational age reached 25 weeks [4–7,10,16–18] (Supplementary Table 8). The lower survival and the development of complications in infants born before 24 weeks could be attributable to the lower rate of antenatal corticosteroid use, the lower rate of cesarean delivery, and less admission to NICU.

Figure 3.

The rate of antenatal corticosteroid treatment, cesarean delivery, and the rate of preterm infants who received active treatment in the reviewed studies; data are shown by gestational age.

In a recent study, Backes et al. [29] analyzed data from infants born at the 22 weeks of gestation in 2 different centers. One center provided proactive care, with all mothers received antenatal corticosteroid treatment, if it was possible, and all infants receiving active care in the delivery room. The other center provided selective care of preterm infants; the parents were involved in all therapeutic decisions including antenatal corticosteroid use, delivery room management, and initiation of intensive care. The proactive center achieved a higher survival rate of more than 50% among infants born at 22 weeks of gestation. Due to the modest sample size, the authors did not draw conclusions about morbidity rates.

Conclusions

In most studies the proportion of infants who received active care was substantially lower among those were born before 24 weeks’ gestation compared with those born after 24 weeks. Despite many large population-based studies having been conducted, accurate comparative data are still lacking regarding the prognosis of premature babies born before and after 24 weeks [30]. This situation creates a possible paradox in care for extremely preterm infants born at the threshold of viability. If we presume a poor outcome of these infants, why would we treat them? However, if we do not initiate intensive care for these infants, how can we know that they would have poor outcomes?

Supplementary Data

Supplementary Table 1.

BPD rates of survived extremely preterm infants by gestational age.

| Study | BPD O2 dependency |

BPD rates (%) by gestational age (week) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22. | 23. | 24. | 25. | 26. | 27. | ||

| NEPS1 [16] | 36. week | – | 67 | 54 | 47 | 32 | 26 |

| NEPS2 [17][ | 36. week | 66.7 | 58.3 | 57.1 | 33.9 | 38.2 | – |

| Kugelman [7] | 40. week | – | 45 | 23.6 | 18.22 | 10.5 | – |

| Agarwal [8] | 36. week | – | 83 | 68 | 50.5 | 32 | 17 |

| EPICURE [18] | 36. week | 100 | 86 | 80 | 67 | 61 | – |

| EXPRESS [10] | 36. week | 40 | 26 | 31 | 29 | 17 | – |

| EPIPAGE2 [5] | 36. week | – | 100 | 37.3 | 28 | 21.9 | – |

| Anderson [6] | 36. week | 65.5 | 58 | 53.1 | 45.7 | 37.3 | 29.6 |

| EPI-SEN [15] | 36. week | 100 | 65.6 | 60.2 | 52.0 | 44.4 | – |

Supplementary Table 2.

Severe IVH rates of survived extremely preterm infants by gestational age.

| Study | Cranial ultrasonography | Severe IVH rates (%) by gestational age (week) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22. | 23. | 24. | 25. | 26. | 27. | ||

| Kugelman [7] | Grade 4 IVH | – | 10 | 8.7 | 7.2 | 7.0 | – |

| EPICURE [18] | Serious abnormality | 33 | 6 | 15 | 15 | 12 | – |

| NEPS1 [16] | Grade 3–4 IVH | – | 11 | 14 | 9 | 4 | 5 |

| NEPS2 [17] | Grade 3–4 IVH | 0 | 0 | 14.3 | 10.2 | 3.9 | – |

| Agarwal [8] | Grade 3–4 IVH | – | 26 | 24 | 14 | 13.2 | 9 |

| EXPRESS [10] | Grade 3–4 IVH | 20 | 19 | 10 | 12 | 5.2 | – |

| EPIPAGE2 [5] | Grade 3–4 IVH | – | 0 | 22.4 | 14.4 | 10.3 | – |

| Anderson [6] | Grade 3–4 IVH | 37.9 | 16.1 | 13.1 | 11.6 | 8.1 | 5.4 |

Supplementary Table 3.

PVL rates of survived extremely preterm infants by gestational age.

| Study | Definition of PVL | PVL rates (%) by gestational age (week) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22. | 23. | 24. | 25. | 26. | 27. | ||

| Agarwal [8] | UH cystic | – | 0 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 4 |

| Kugelman [7] | Not defined | – | 10.5 | 14.7 | 10.6 | 10.9 | – |

| EXPRESS [10] | Cystic | 0 | 9.4 | 6.2 | 5.4 | 4.5 | – |

| EPIPAGE2 [5] | Cystic | – | 0 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 2.6 | – |

| Anderson [6] | Not defined | 6.9 | 6.2 | 3.3 | 2.9 | 2.3 | 1.8 |

| NEPS2 [17] | UH cystic | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.1 | 9.2 | – |

Supplementary Table 4.

ROP rates of survived extremely preterm infants by gestational age.

| Study | Severe ROP | ROP rates (%) by gestational age (week) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22. | 23. | 24. | 25. | 26. | 27. | ||

| EPIPAGE2 [5] | >2 stage | – | 0 | 17.2 | 9.4 | 1.9 | – |

| Agarwal [8] | >2 stage | – | 83.4 | 62 | 42 | 18 | 11 |

| EXPRESS [10] | >2 stage | 80 | 62 | 48 | 32 | 19 | – |

| NEPS2 [17] | >2 stage | 0 | 33.3 | 34.3 | 18.6 | 6.6 | – |

| EPICURE [18] | Surgically treated | 0 | 33 | 27 | 7 | 9 | – |

| Anderson [6] | Surgically treated | 27.6 | 35.8 | 26.4 | 18 | 9.6 | 3.5 |

Supplementary Table 5.

NEC rates of survived extremely preterm infants by gestational age.

| Study | Survived/ All infants | Surgically treated/Stage ≥2 by Bell’s criteria | NEC rates (%) by gestational age (week) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22. | 23. | 24. | 25. | 26. | 27. | 28. | |||

| EPICURE [18] | Survived | Surgically treated | 33 | 6 | 11 | 7 | 6 | – | – |

| EXPRESS [10] | Survived | Stage ≥2 | 0 | 1.9 | 9.4 | 6.0 | 5.1 | – | – |

| Agarwal [8] | Survived | Stage ≥2 SIP excluded | 0 | 9 | 8.6 | 9.6 | 4.4 | 3.6 | 5.8 |

| EPIPAGE2 [5] | Survived | Stage ≥2 | – | 100 | 5.3 | 5.5 | 4.5 | – | – |

| Anderson [6] | Survived | Stage ≥2 | 13.8 | 18.5 | 13.8 | 11.3 | 10.9 | 8.9 | 6.7 |

| NEPS2 [17] | Survived | Stage ≥2 | 0 | 16.7 | 5.7 | 8.5 | 1.3 | – | – |

Supplementary Table 6.

Rates of antenatal corticosteroid use among extremely preterm infants by gestational age.

| Study | Partial/Complete antenatal steroid therapy | Rates of antenatal corticosteroid use (%) by gestational age (week) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22. | 23. | 24. | 25. | 26. | ||

| Kugelman [7] | Partial | – | 25 | 51 | 61 | 66 |

| Agarwal [8] | Complete | – | 38 | 67 | 72 | 80 |

| EPICURE [18] | Complete | 14 | 58 | 84 | 88 | 86 |

| EXPRESS [10] | Partial | 40 | 85 | 95 | 89 | 93 |

| Ishii [11] | Partial | 21.3 | 32.2 | 41.3 | 43.7 | – |

| EPIPAGE2 [5] | Partial | 1.8 | 12.3 | 56.7 | 75.5 | 80.6 |

| NEPS1 [16] | Partial | 35.3 | 85.7 | 93.5 | 90 | 90.5 |

| NEPS2 [17] | Complete | 0 | 59.5 | 61.3 | 61.4 | 72.6 |

Supplementary Table 7.

Rates of extremely preterm infants delivered by Cesarean section by gestational age.

| Study | Rates of extremely preterm infants delivered by Cesarean section (%) by gestational age (week) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22. | 23. | 24. | 25. | 26. | 27. | 28. | |

| Kugelman [7] | – | 17 | 37 | 54 | 65 | – | – |

| Agarwal [8] | – | 2 | 30 | 35 | 60 | – | – |

| EPICURE [18] | 5 | 6 | 14 | 31 | 44 | – | – |

| EXPRESS [10] | 6 | 16 | 46 | 62 | 68 | ||

| Ishii [11] | 24 | 42.4 | 65.7 | 73.3 | – | – | – |

| EPIPAGE2 [5] | 8.8 | 4.6 | 13.5 | 34 | 59.9 | – | – |

| Anderson [6] | 13.6 | 38.4 | 65 | 67.2 | 68.4 | 70.2 | 72.9 |

| NEPS2 [17] | 11.8 | 11.9 | 32.3 | 50 | 61.9 | – | – |

| EPI-SEN [15] | 13.0 | 15.6 | 32.3 | 41.5 | 54.8 | – | – |

Supplementary Table 8.

Rates of extremely preterm infants who received neonatal intensive care.

| Study | Actively treated/Admitted to NICU | Rates of extremely preterm infants who received neonatal intensive care (%) by gestational age (week) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22. | 23. | 24. | 25. | 26. | 27. | 28. | ||

| EPIBEL [4] | NICU | 50 | 72.2 | 83 | 100 | 98.7 | – | – |

| NEPS1 [16] | NICU | 5 | 42 | 73 | 83 | 86 | 88 | – |

| NEPS2 [17] | NICU | 29.4 | 81 | 96.8 | 98.6 | 98.8 | – | – |

| Kugelman [7] | Active care | – | 61 | 83 | 85 | 81 | – | – |

| Agarwal [8] | Active care | – | 49 | 90 | 98.5 | 98 | – | – |

| EPICURE [18] | NICU | 13 | 64 | 86 | 96 | 98 | – | – |

| EXPRESS [10] | NICU | 38 | 81 | 93 | 98 | 100 | ||

| Anderson [6] | Active care | 20.7 | 64 | 92.8 | 97.4 | 99.5 | 99.3 | 99.5 |

| EPIPAGE2 [5] | NICU | 6.1 | 60.8 | 91.9 | 98.9 | – | – | |

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None.

Source of support: Self financing

References

- 1.Martin RJ, Fanaroff AA, Walsh MC. Fanaroff and Martin’s neonatal-perinatal medicine: diseases of the fetus and infant. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2011. p. 39. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guillen U, Weiss EM, Munson D, et al. Guidelines for the management of extremely premature deliveries: A systematic review. Pediatrics. 2015;136(2):343–50. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-0542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fanaroff JM, Hascoet JM, Hansen TW, et al. The ethics and practice of neonatal resuscitation at the limits of viability: An international perspective. Acta Paediatr. 2014;103(7):701–8. doi: 10.1111/apa.12633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vanhaesebrouck P, Allegaert K, Bottu J, et al. The EPIBEL study: Outcomes to discharge from hospital for extremely preterm infants in Belgium. Pediatrics. 2004;114(3):663–75. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-0903-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ancel PY, Goffinet F EPIPAGE 2 Writing Group. EPIPAGE 2: A preterm birth cohort in France in 2011. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:97. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-14-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson JG, Baer RJ, Partridge JC, et al. Survival and major morbidity of extremely preterm infants: A population-based study. Pediatrics. 2016;138(1):e20154434. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-4434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kugelman A, Bader D, Lerner-Geva L, et al. Poor outcomes at discharge among extremely premature infants: A national population-based study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(6):543–50. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agarwal P, Sriram B, Rajadurai VS. Neonatal outcome of extremely preterm Asian infants 28 weeks over a decade in the new millennium. J Perinatol. 2015;35(4):297–303. doi: 10.1038/jp.2014.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fischer N, Steurer MA, Adams M, Berger TM Swiss Neonatal Network. Survival rates of extremely preterm infants (gestational age <26 weeks) in Switzerland: Impact of the Swiss guidelines for the care of infants born at the limit of viability. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2009;94(6):F407–13. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.154567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.EXPRESS Group. Fellman V, Hellström-Westas L, Norman M, et al. One-year survival of extremely preterm infants after active perinatal care in Sweden. JAMA. 2009;301(21):2225–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishii N, Kono Y, Yonemoto N, et al. Outcomes of infants born at 22 and 23 weeks’ gestation. Pediatrics. 2013;132(1):62–71. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doyle LW, Roberts G, Anderson PJ Victorian Infant Collaborative Study Group. Outcomes at age 2 years of infants <28 weeks’ gestational age born in Victoria in 2005. J Pediatr. 2010;156(1):49–53.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Su BH, Hsieh WS, Hsu CH, et al. Neonatal outcomes of extremely preterm infants from taiwan: comparison with Canada, Japan, and the USA. Pediatr Neonatol. 2015;56(1):46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, et al. Trends in care practices, morbidity, and mortality of extremely preterm neonates, 1993–2012. JAMA. 2015;314(10):1039–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia-Munoz Rodrigo F, Diez Recinos AL, Garcia-Alix Perez A, et al. Changes in perinatal care and outcomes in newborns at the limit of viability in Spain: The EPI-SEN Study. Neonatology. 2015;107(2):120–29. doi: 10.1159/000368881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Markestad T, Kaaresen PI, Ronnestad A, et al. Early death, morbidity, and need of treatment among extremely premature infants. Pediatrics. 2005;115(5):1289–98. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stensvold HJ, Klingenberg C, Stoen R, et al. Neonatal morbidity and 1-year survival of extremely preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2017;139(3):e20161821. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Costeloe KL, Hennessy EM, Haider S, et al. Short term outcomes after extreme preterm birth in England: Comparison of two birth cohorts in 1995 and 2006 (the EPICure studies) BMJ. 2012;345:e7976. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ehret DEY, Edwards EM, Greenberg LT, et al. Association of antenatal steroid exposure with survival among infants receiving postnatal life support at 22 to 25 weeks’ gestation. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(6):e183235. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carlo WA, McDonald SA, Fanaroff AA, et al. Association of antenatal corticosteroids with mortality and neurodevelopmental outcomes among infants born at 22 to 25 weeks’ gestation. JAMA. 2011;306(21):2348–58. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tyson JE, Parikh NA, Langer J, et al. Intensive care for extreme prematurity – moving beyond gestational age. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(16):1672–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alfirevic Z, Milan SJ, Livio S. Caesarean section versus vaginal delivery for preterm birth in singletons. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(6):CD000078. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000078.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reddy UM, Zhang J, Sun L, et al. Neonatal mortality by attempted route of delivery in early preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(2):117.e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahya K, Suryawanshi P. Neonatal periventricular leukomalacia: Current perspectives. Research and Reports in Neonatology. 2018;8:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khwaja O, Volpe JJ. Pathogenesis of cerebral white matter injury of prematurity. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2008;93(2):F153–61. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.108837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gordon PV, Swanson JR, Attridge JT, Clark R. Emerging trends in acquired neonatal intestinal disease: Is it time to abandon Bell’s criteria? J Perinatol. 2007;27(11):661–71. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haque K. Necrotizing enterocolitis – some things old and some things new: A comprehensive review. J Clin Neonatol. 2016;5(2):79–90. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rysavy MA, Marlow N, Doyle LW, et al. Reporting outcomes of extremely preterm births. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3):e20160689. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Backes CH, Soderstrom F, Agren J, et al. Outcomes following a comprehensive versus a selective approach for infants born at 22 weeks of gestation. J Perinatol. 2019;39(1):39–47. doi: 10.1038/s41372-018-0248-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lantos JD. We know less than we think we know about perinatal outcomes. Pediatrics. 2018;2018:e20181223. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1.

BPD rates of survived extremely preterm infants by gestational age.

| Study | BPD O2 dependency |

BPD rates (%) by gestational age (week) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22. | 23. | 24. | 25. | 26. | 27. | ||

| NEPS1 [16] | 36. week | – | 67 | 54 | 47 | 32 | 26 |

| NEPS2 [17][ | 36. week | 66.7 | 58.3 | 57.1 | 33.9 | 38.2 | – |

| Kugelman [7] | 40. week | – | 45 | 23.6 | 18.22 | 10.5 | – |

| Agarwal [8] | 36. week | – | 83 | 68 | 50.5 | 32 | 17 |

| EPICURE [18] | 36. week | 100 | 86 | 80 | 67 | 61 | – |

| EXPRESS [10] | 36. week | 40 | 26 | 31 | 29 | 17 | – |

| EPIPAGE2 [5] | 36. week | – | 100 | 37.3 | 28 | 21.9 | – |

| Anderson [6] | 36. week | 65.5 | 58 | 53.1 | 45.7 | 37.3 | 29.6 |

| EPI-SEN [15] | 36. week | 100 | 65.6 | 60.2 | 52.0 | 44.4 | – |

Supplementary Table 2.

Severe IVH rates of survived extremely preterm infants by gestational age.

| Study | Cranial ultrasonography | Severe IVH rates (%) by gestational age (week) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22. | 23. | 24. | 25. | 26. | 27. | ||

| Kugelman [7] | Grade 4 IVH | – | 10 | 8.7 | 7.2 | 7.0 | – |

| EPICURE [18] | Serious abnormality | 33 | 6 | 15 | 15 | 12 | – |

| NEPS1 [16] | Grade 3–4 IVH | – | 11 | 14 | 9 | 4 | 5 |

| NEPS2 [17] | Grade 3–4 IVH | 0 | 0 | 14.3 | 10.2 | 3.9 | – |

| Agarwal [8] | Grade 3–4 IVH | – | 26 | 24 | 14 | 13.2 | 9 |

| EXPRESS [10] | Grade 3–4 IVH | 20 | 19 | 10 | 12 | 5.2 | – |

| EPIPAGE2 [5] | Grade 3–4 IVH | – | 0 | 22.4 | 14.4 | 10.3 | – |

| Anderson [6] | Grade 3–4 IVH | 37.9 | 16.1 | 13.1 | 11.6 | 8.1 | 5.4 |

Supplementary Table 3.

PVL rates of survived extremely preterm infants by gestational age.

| Study | Definition of PVL | PVL rates (%) by gestational age (week) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22. | 23. | 24. | 25. | 26. | 27. | ||

| Agarwal [8] | UH cystic | – | 0 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 4 |

| Kugelman [7] | Not defined | – | 10.5 | 14.7 | 10.6 | 10.9 | – |

| EXPRESS [10] | Cystic | 0 | 9.4 | 6.2 | 5.4 | 4.5 | – |

| EPIPAGE2 [5] | Cystic | – | 0 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 2.6 | – |

| Anderson [6] | Not defined | 6.9 | 6.2 | 3.3 | 2.9 | 2.3 | 1.8 |

| NEPS2 [17] | UH cystic | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.1 | 9.2 | – |

Supplementary Table 4.

ROP rates of survived extremely preterm infants by gestational age.

| Study | Severe ROP | ROP rates (%) by gestational age (week) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22. | 23. | 24. | 25. | 26. | 27. | ||

| EPIPAGE2 [5] | >2 stage | – | 0 | 17.2 | 9.4 | 1.9 | – |

| Agarwal [8] | >2 stage | – | 83.4 | 62 | 42 | 18 | 11 |

| EXPRESS [10] | >2 stage | 80 | 62 | 48 | 32 | 19 | – |

| NEPS2 [17] | >2 stage | 0 | 33.3 | 34.3 | 18.6 | 6.6 | – |

| EPICURE [18] | Surgically treated | 0 | 33 | 27 | 7 | 9 | – |

| Anderson [6] | Surgically treated | 27.6 | 35.8 | 26.4 | 18 | 9.6 | 3.5 |

Supplementary Table 5.

NEC rates of survived extremely preterm infants by gestational age.

| Study | Survived/ All infants | Surgically treated/Stage ≥2 by Bell’s criteria | NEC rates (%) by gestational age (week) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22. | 23. | 24. | 25. | 26. | 27. | 28. | |||

| EPICURE [18] | Survived | Surgically treated | 33 | 6 | 11 | 7 | 6 | – | – |

| EXPRESS [10] | Survived | Stage ≥2 | 0 | 1.9 | 9.4 | 6.0 | 5.1 | – | – |

| Agarwal [8] | Survived | Stage ≥2 SIP excluded | 0 | 9 | 8.6 | 9.6 | 4.4 | 3.6 | 5.8 |

| EPIPAGE2 [5] | Survived | Stage ≥2 | – | 100 | 5.3 | 5.5 | 4.5 | – | – |

| Anderson [6] | Survived | Stage ≥2 | 13.8 | 18.5 | 13.8 | 11.3 | 10.9 | 8.9 | 6.7 |

| NEPS2 [17] | Survived | Stage ≥2 | 0 | 16.7 | 5.7 | 8.5 | 1.3 | – | – |

Supplementary Table 6.

Rates of antenatal corticosteroid use among extremely preterm infants by gestational age.

| Study | Partial/Complete antenatal steroid therapy | Rates of antenatal corticosteroid use (%) by gestational age (week) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22. | 23. | 24. | 25. | 26. | ||

| Kugelman [7] | Partial | – | 25 | 51 | 61 | 66 |

| Agarwal [8] | Complete | – | 38 | 67 | 72 | 80 |

| EPICURE [18] | Complete | 14 | 58 | 84 | 88 | 86 |

| EXPRESS [10] | Partial | 40 | 85 | 95 | 89 | 93 |

| Ishii [11] | Partial | 21.3 | 32.2 | 41.3 | 43.7 | – |

| EPIPAGE2 [5] | Partial | 1.8 | 12.3 | 56.7 | 75.5 | 80.6 |

| NEPS1 [16] | Partial | 35.3 | 85.7 | 93.5 | 90 | 90.5 |

| NEPS2 [17] | Complete | 0 | 59.5 | 61.3 | 61.4 | 72.6 |

Supplementary Table 7.

Rates of extremely preterm infants delivered by Cesarean section by gestational age.

| Study | Rates of extremely preterm infants delivered by Cesarean section (%) by gestational age (week) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22. | 23. | 24. | 25. | 26. | 27. | 28. | |

| Kugelman [7] | – | 17 | 37 | 54 | 65 | – | – |

| Agarwal [8] | – | 2 | 30 | 35 | 60 | – | – |

| EPICURE [18] | 5 | 6 | 14 | 31 | 44 | – | – |

| EXPRESS [10] | 6 | 16 | 46 | 62 | 68 | ||

| Ishii [11] | 24 | 42.4 | 65.7 | 73.3 | – | – | – |

| EPIPAGE2 [5] | 8.8 | 4.6 | 13.5 | 34 | 59.9 | – | – |

| Anderson [6] | 13.6 | 38.4 | 65 | 67.2 | 68.4 | 70.2 | 72.9 |

| NEPS2 [17] | 11.8 | 11.9 | 32.3 | 50 | 61.9 | – | – |

| EPI-SEN [15] | 13.0 | 15.6 | 32.3 | 41.5 | 54.8 | – | – |

Supplementary Table 8.

Rates of extremely preterm infants who received neonatal intensive care.

| Study | Actively treated/Admitted to NICU | Rates of extremely preterm infants who received neonatal intensive care (%) by gestational age (week) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22. | 23. | 24. | 25. | 26. | 27. | 28. | ||

| EPIBEL [4] | NICU | 50 | 72.2 | 83 | 100 | 98.7 | – | – |

| NEPS1 [16] | NICU | 5 | 42 | 73 | 83 | 86 | 88 | – |

| NEPS2 [17] | NICU | 29.4 | 81 | 96.8 | 98.6 | 98.8 | – | – |

| Kugelman [7] | Active care | – | 61 | 83 | 85 | 81 | – | – |

| Agarwal [8] | Active care | – | 49 | 90 | 98.5 | 98 | – | – |

| EPICURE [18] | NICU | 13 | 64 | 86 | 96 | 98 | – | – |

| EXPRESS [10] | NICU | 38 | 81 | 93 | 98 | 100 | ||

| Anderson [6] | Active care | 20.7 | 64 | 92.8 | 97.4 | 99.5 | 99.3 | 99.5 |

| EPIPAGE2 [5] | NICU | 6.1 | 60.8 | 91.9 | 98.9 | – | – | |