Abstract

Objective:

This study examined changes in pelvic floor support structure and function after urogynecological surgery.

Methods:

This multisite clinical study was designed to explore changes in tissue elasticity, pelvic support, and certain functions (contractive strength, muscle relaxation speed, muscle motility) after pelvic organ prolapse (POP) surgery. A biomechanical mapping of the pelvic floor was performed before and 4 to 6 months after the surgery. The biomechanical data for 52 parameters were acquired by vaginal tactile imaging for manually applied deflection pressures to vaginal walls and pelvic muscle contractions. The two-sample t-test (p<0.05) was employed to test the null hypothesis that the data in Group 1 (positive parameter change after surgery) and Group 2 (negative parameter change after surgery) belonged to the same distribution.

Results:

78 subjects with 255 surgical procedures were analyzed across five participating clinical sites. All 52 t-tests for Group 1 versus Group 2 had p-value in the range form 4.0*10−10 to 4.3*10−2 associating all of the 52 parameter changes after surgery with the pre-surgical conditions. The p-value of before and after surgery correlation ranged from 3.7*10−18 to 1.6*10−2 for 50 of 52 tests; with Pearson correlation coefficient ranging from−0.79 to−-0.27. Thus, vaginal tactile imaging parameters strongly correlated weak pelvic floor pre-surgery with the positive POP surgery outcome of improved biomechanical properties.

Conclusions:

POP surgery, in general, improves the biomechanical conditions and integrity of the weak pelvic floor. The proposed biomechanical parameters can predict changes resulting from POP surgery.

Keywords: Pelvic organ prolapse surgery outcome, biomechanical mapping

Introduction

A Recent survey by the American Urogynecologic Society identified the research questions with the highest priority pertaining to pathophysiology and treatment of pelvic organ prolapse (POP) [1]. According to the survey, mechanistic research on pelvic supportive structures, clinical trials to optimize outcomes after POP surgery and evidence-based quality measures for POP outcomes are among the main focus areas. These research questions are relevant due to the overall recurrence rate of 20% in vaginal prolapse surgery [2]. The surgical failure rate is as high as 61.5% in the uterosacral ligament suspension group and 70.3% in the sacrospinous ligament fixation group in the representative randomized clinical study with the 5-year outcomes [3].

Many pelvic floor disorders, including POP, are manifested by concurring changes in the mechanical properties of pelvic organs. Therefore, the biomechanical mapping of response to applied pressure or load within the pelvic floor and muscle contractive patterns opens new possibilities in the biomechanical assessment and monitoring of the female pelvic floor conditions. The newly developed vaginal tactile imaging approach allows the biomechanical mapping of the female pelvic floor, including the assessment of tissue elasticity, pelvic support, and pelvic muscle functions in high definition [4–7]. The intra- and inter-observer reproducibility of the vaginal tactile imaging has been reported earlier [8]. The interpretation of biomechanical mapping of the female pelvic floor was proposed [9]. A set of 52 new mechanistic parameters for assessment of the vaginal and pelvic floor conditions was introduced [10, 11].

POP surgery aims to restore the anatomy, biomechanical integrity, and functions of the female pelvic floor [12, 13]. The rationale behind this research was to assess the predictive value of the biomechanical mapping for POP surgery. The objective of this research was to explore the changes in the biomechanical parameters of the pelvic floor after urogynecological surgery.

Materials and Methods

Biomechanical Mapping

The Vaginal Tactile Imager (VTI), model 2S (Advanced Tactile Imaging, New Jersey), was used for the biomechanical mapping of the pelvic floor before and after surgery. The VTI probe is equipped with a pressure sensor array which measures the dynamic pressure response to applied deformation, integrates and visualizes in real time the biomechanical map of the examined area [7–9].

The VTI examination procedure consists of eight Tests: 1) probe insertion, 2) elevation, 3) rotation, 4) Valsalva maneuver, 5) voluntary muscle contraction, 6) voluntary muscle contraction (left versus right side), 7) involuntary relaxation, and 8) reflex muscle contraction (cough). Tests 1– and 7–8 provide data for anterior/posterior compartments; test 6 provides data for left/right sides [9, 11]. This VTI probe allows 3–15 mm tissue deformation at the probe insertion (Test 1), 20–45 mm tissue deformation at the probe elevation (Test 2), 5–7 mm deformation at the probe rotation (Test 3) and recording of dynamic responses at pelvic muscle contractions (Tests 4–8). The probe maneuvers in Tests 1–3 are used to accumulate multiple pressure patterns from the tissue surface and create an integrated tactile image for the investigated area employing the image composition algorithms described earlier [6].

The VTI reproducibility was studied with 1920 VTI measurements (12 subjects × 10 parameters × 4 locations × 4 VTI examinations). Specifically, intra-observer Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICC) were found in the range from 0.80 for Test 8 to 0.92 for Test 3 with average value of 0.87 for all 10 parameters. Inter-observer ICCs were found in the range from 0.73 for Test 2 and Test 8 to 0.92 for Test 3 with average value of 0.82. Furthermore, Intra-observer 95% limits of agreement were in the range from ±11.3% for Test 1 to ±19.0%% for Test 8 with the average value of ±15.1%. Inter-observer 95% limits of agreement were in the range from ±12.0% for Test 5 to ±26.7% for Test 2 with the average value of ±18.4% [8]. These correspond to moderate VTI intra- and inter-observer reproducibility. The anticipated average error in VTI parameters was 14% for intra-observer and 18% for inter-observer measurements.

Outcome Measures

The 52 biomechanical parameters listed in Table 1, were calculated for each of the subjects before and after pelvic surgery. The anatomical assignment of the targeting/contributing pelvic structures into the specified parameters is based on the functional anatomy of the pelvis [9, 14–18].

Table 1.

VTI Biomechanical Parameters

| No. | VTI Test | Parameters Abbreviation | Units | Parameter Description | Parameter Interpretation | Parameter Class | Targeting/Contributing Pelvic Structures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | Fmax | N | Maximum value of force measured during the VTI probe insertion [9] | Maximum resistance of anterior vs posterior widening; tissue elasticity at specified location (capability to resist to applied deformation) | Maximum vaginal tissue elasticity at specified location | Tissues behind the anterior and posterior vaginal walls at 3–15 mm depth |

| 2 | 1 | Work | mJ | Work completed during the probe insertion (Work = Force × Displacement) [10] | Integral resistance of vaginal tissue (anterior and posterior) along the probe insertion | Average vaginal tissue elasticity | Tissues behind the anterior and posterior vaginal walls at 3–15 mm depth |

| 3 | 1 | Gmax_a | kPa/ mm |

Maximum value of anterior gradient (change of pressure per anterior wall displacement in orthogonal direction to the vaginal channel) | Maximum value of tissue elasticity in anterior compartment behind the vaginal at specified location | Maximum value of anterior tissue elasticity | Tissues/structures in anterior compartment at 10–15 mm depth |

| 4 | 1 | Gmax_p | kPa/ mm |

Maximum value of posterior gradient (change of pressure per posterior wall displacement in orthogonal direction to the vaginal channel) | Maximum value of tissue elasticity in posterior compartment behind the vaginal at specified location | Maximum value of posterior tissue elasticity | Tissues/structures in anterior compartment at 10–15 mm depth |

| 5 | 1 | Pmax_a | kPa | Maximum value of pressure per anterior wall along the vagina | Maximum resistance of anterior tissue to vaginal wall deformation | Anterior tissue elasticity | Tissues/structures in anterior compartment |

| 6 | 1 | Pmax_p | kPa | Maximum value of pressure per posterior wall along the vagina | Maximum resistance of posterior tissue to vaginal wall deformation | Posterior tissue elasticity | Tissues/structures in posterior compartment |

| 7 | 2 | P1max_a | kPa | Maximum pressure at the area of pubic bone (anterior compartment) | Proximity of pubic bone to vaginal wall and perineal body strength | Anatomic aspects and tissue elasticity | Tissues between vagina and pubic bone; perineal body |

| 8 | 2 | P2max_a | kPa | Maximum pressure at the area of urethra (anterior compartment) | Elasticity/mobility of urethra | Anatomic aspects and tissue elasticity | Urethra and surrounding tissues |

| 9 | 2 | P3max_a | kPa | Maximum pressure at the cervix area (anterior compartment) | Mobility of uterus and conditions of uterosacral and cardinal ligaments | Pelvic floor support | Uterosacral and cardinal ligaments |

| 10 | 2 | P1max_p | kPa | Maximum pressure at the perineal body (posterior compartment) | Pressure feedback of Level III support | Pelvic floor support | Puboperineal, puborectal muscles |

| 11 | 2 | P2max_p | kPa | Maximum pressure at middle third of vagina (posterior compartment) | Pressure feedback of Level II support | Pelvic floor support | Pubovaginal, puboanal muscles |

| 12 | 2 | P3max_p | kPa | Maximum pressure at upper third of vagina (posterior compartment) | Pressure feedback of Level I support | Pelvic floor support | Iliococcygeal muscle, levator plate |

| 13 | 2 | G1max_a | kPa/ mm |

Maximum gradient at the area of pubic bone (anterior compartment) | Vaginal elasticity at pubic bone area | Anterior tissue elasticity | Tissues between vagina and pubic bone; perineal body |

| 14 | 2 | G2max_a | kPa/ mm |

Maximum gradient at the area of urethra (anterior compartment) | Mobility and elasticity of urethra | Urethral tissue elasticity | Urethra and surrounding tissues |

| 15 | 2 | G3max_a | kPa/ mm |

Maximum gradient at the cervix area (anterior compartment) | Conditions of uterosacral and cardinal ligaments | Pelvic floor support | Uterosacral and cardinal ligaments |

| 16 | 2 | G1max_p | kPa/ mm |

Maximum gradient at the perineal body (posterior compartment) | Strength of Level III support (tissue deformation up to 25 mm) | Pelvic floor support | Puboperineal, puborectal muscles |

| 17 | 2 | G2max_p | kPa/ mm |

Maximum gradient at middle third of vagina (posterior compartment) | Strength of Level II support (tissue deformation up to 35 mm) | Pelvic floor support | Pubovaginal, puboanal muscles |

| 18 | 2 | G3max_p | kPa/ mm |

Maximum gradient at upper third of vagina (posterior compartment) | Strength of Level I support (tissue deformation up to 45 mm) | Pelvic floor support | Iliococcygeal muscle, levator plate |

| 19 | 3 | Pmax | kPa | Maximum pressure at vaginal walls deformation by 7 mm [10] | Hard tissue or tight vagina | Vaginal tissue elasticity | Tissues behind the vaginal walls at 5–7 mm depth |

| 20 | 3 | Fap | N | Force applied by anterior and posterior compartments to the probe [10]. | Integral strength of anterior and posterior compartments | Vaginal tightening | Tissues behind anterior/ posterior vaginal walls. |

| 21 | 3 | Fs | N | Force applied by entire left and right sides of vagina to the probe [10]. | Integral strength of left and right sides of vagina | Vaginal tightening | Vaginal right/left walls and tissues behind them. |

| 22 | 3 | P1_l | kPa | Pressure response from a selected location (irregularity 1) at left side | Hard tissue on left vaginal wall | Irregularity on vaginal wall | Tissue/muscle behind the vaginal walls on left side. |

| 23 | 3 | P2_l | kPa | Pressure response from a selected location (irregularity 2) at left side | Hard tissue on left vaginal wall | Irregularity on vaginal wall | Tissue/muscle behind the vaginal walls on left side. |

| 24 | 3 | P3_r | kPa | Pressure response from a selected location (irregularity 3) at right side | Hard tissue on right vaginal wall | Irregularity on vaginal wall | Tissue/muscle behind the vaginal walls on right side. |

| 25 | 4 | dF_a | N | Integral force change in anterior compartment at Valsalva maneuver | Pelvic function* at Valsalva maneuver | Pelvic function | Multiple pelvic muscle* |

| 26 | 4 | dPmax_a | kPa | Maximum pressure change in anterior compartment at Valsalva maneuver. | Pelvic function* at Valsalva maneuver | Pelvic function | Multiple pelvic muscle* |

| 27 | 4 | dL_a | mm | Displacement of the maximum pressure peak in anterior compartment | Mobility of anterior structures* Valsalva maneuver | Pelvic function | Urethra, pubovaginal muscle; ligaments* |

| 28 | 4 | dF_p | N | Integral force change in posterior compartment at Valsalva maneuver | Pelvic function* at Valsalva maneuver | Pelvic function | Multiple pelvic muscle* |

| 29 | 4 | dPmax_p | kPa | Maximum pressure change in posterior compartment at Valsalva maneuver. | Pelvic function* at Valsalva maneuver | Pelvic function | Multiple pelvic muscle* |

| 30 | 4 | dL_p | mm | Displacement of the maximum pressure peak in posterior compartment | Mobility of posterior structures* Valsalva maneuver | Pelvic function | Anorectal, puborectal, pubovaginal muscles; ligaments* |

| 31 | 5 | dF_a | N | Integral force change in anterior compartment at voluntary muscle contraction | Integral contraction strength of pelvic muscles along the vagina | Pelvic function | Puboperineal, puborectal, pubovaginal and ilicoccygeal muscles; urethra |

| 32 | 5 | dPmax_a | kPa | Maximum pressure change in anterior compartment at voluntary muscle contraction | Contraction strength of specified pelvic muscles | Pelvic function | Puboperineal, puborectal and pubovaginal muscles |

| 33 | 5 | Pmax_a | kPa | Maximum pressure value in anterior compartment at voluntary muscle contraction. | Static and dynamic peak support of the pelvic floor | Pelvic function | Puboperineal and puborectal muscles* |

| 34 | 5 | dF_p | N | Integral force change in posterior compartment at voluntary muscle contraction | Integral contraction strength of pelvic muscles along the vagina | Pelvic function | Puboperineal, puborectal, pubovaginal and ilicoccygeal muscles |

| 35 | 5 | dPmax_p | kPa | Maximum pressure change in posterior compartment at voluntary muscle contraction | Contraction strength of pelvic muscles at specified location | Pelvic function | Puboperineal, puborectal and pubovaginal muscles |

| 36 | 5 | Pmax_p | kPa | Maximum pressure value in posterior compartment at voluntary muscle contraction. | Static and dynamic peak support of the pelvic floor | Pelvic function | Puboperineal and puborectal muscles* |

| 37 | 6 | dF_r | N | Integral force change in right side at voluntary muscle contraction | Integral contraction strength of pelvic muscles along the vagina | Pelvic function | Puboperineal, puborectal, and pubovaginal muscles |

| 38 | 6 | dPmax_r | kPa | Maximum pressure change in right side at voluntary muscle contraction | Contraction strength of specific pelvic muscle | Pelvic function | Puboperineal or puborectal or pubovaginal muscles |

| 39 | 6 | Pmax_r | kPa | Maximum pressure value in right side at voluntary muscle contraction | Specified pelvic muscle contractive capability and integrity | Pelvic function | Puboperineal or puborectal muscles |

| 40 | 6 | dF_l | N | Integral force change in left side at voluntary muscle contraction | Integral contraction strength of pelvic muscles along the vagina | Pelvic function | Puboperineal, puborectal, and pubovaginal muscles |

| 41 | 6 | dPmax_l | kPa | Maximum pressure change in left side at voluntary muscle contraction | Contraction strength of specific pelvic muscle | Pelvic function | Puboperineal or puborectal or pubovaginal muscles |

| 42 | 6 | Pmax_l | kPa | Maximum pressure value in left side at voluntary muscle contraction | Specified pelvic muscle contractive capability and integrity | Pelvic function | Puboperineal or puborectal muscles |

| 43 | 7 | dPdt_a | kPa/s | Anterior absolute pressure change per second for maximum pressure at involuntary relaxation | Innervation status of specified pelvic muscles | Innervations status | Levator ani muscles |

| 44 | 7 | dpcdt_a | %/s | Anterior relative pressure change per second for maximum pressure at involuntary relaxation | Innervation status of specified pelvic muscles | Innervations status | Levator ani muscles |

| 45 | 7 | dPdt_p | kPa/s | Posterior absolute pressure change per second for maximum pressure at involuntary relaxation | Innervation status of specified pelvic muscles | Innervations status | Levator ani muscles |

| 46 | 7 | dpcdt_p | %/s | Posterior relative pressure change per second for maximum pressure at involuntary relaxation | Innervation status of specified pelvic muscles | Innervations status | Levator ani muscles |

| 47 | 8 | dF_a | N | Integral force change in anterior compartment at reflex pelvic muscle contraction (cough) | Integral pelvic function* at reflex muscle contraction | Pelvic function | Multiple pelvic muscle* |

| 48 | 8 | dPmax_a | kPa | Maximum pressure change in anterior compartment at reflex pelvic muscle contraction (cough). | Contraction strength of specified pelvic muscles | Pelvic function | Multiple pelvic muscle* |

| 49 | 8 | dL_a | mm | Displacement of the maximum pressure peak in anterior compartment | Urethral mobility at reflex muscle contraction | Pelvic function | Urethra |

| 50 | 8 | dF_p | N | Integral force change in posterior compartment at reflex pelvic muscle contraction (cough) | Integral pelvic function* at reflex muscle contraction | Pelvic function | Multiple pelvic muscle* |

| 51 | 8 | dPmax_p | kPa | Maximum pressure change in posterior compartment at reflex pelvic muscle contraction (cough). | Contraction strength of specified pelvic muscles | Pelvic function | Multiple pelvic muscle* |

| 52 | 8 | dL_p | mm | Displacement of the maximum pressure peak in posterior compartment | Mobility of anterior structures* at reflex muscle contraction | Pelvic function | Anorectal, puborectal and pubovaginal muscles; ligaments* |

requires further interpretation

Study Population Description

Initially, 119 subjects were enrolled into the study at five clinical sites in the period from January 2017 to September 2018. The study inclusion criteria were (1) subjects scheduled for pelvic floor surgery, (2) 21 years or older, (3) no prior pelvic floor surgery, and (4) one of the following: normal pelvic floor conditions or POP Stage I-IV affecting one or more vaginal compartments. The definition of “prior pelvic surgery” included women who had not undergone any POP surgery. Women who had prior hysterectomy were also excluded from this reported data analysis as prior hysterectomy requires a separate consideration. The study exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) active skin infection or ulceration within the vagina, (2) presence of a vaginal septum, (3) active cancer of the colon, rectum wall, cervix, vaginal, uterus or bladder, (4) ongoing radiation therapy for pelvic cancer, (5) impacted stool, (6) significant pre-existing pelvic pain including levator ani syndrome, severe vaginismus or vulvodynia, (7) severe hemorrhoids, (8) significant circulatory or cardiac conditions that could cause excessive risk from the examination as determined by attending physician, and (9) current pregnancy. For each of the subjects, an appropriate evaluation was performed by their urogynecologists with the treatment plan prescribed independently from this study and as the best fit for their specific pelvic conditions. Ten cases were excluded due to prior pelvic surgery (hysterectomy); 29 cases were excluded due to the absence of one or two VTI examinations; 2 cases were excluded due to the absence of pre-surgical POP (hysterectomy and/or sling insertion only were completed). Seventy-eight cases/subjects with 255 surgical procedures were included in reported data analysis. Procedures the 78 subjects had undergone were: 26 sacral colpopexies, 27 sacrospinous ligament suspensions, 15 uterosacral ligament suspensions, 1 illiococcygeal suspension, 38 anterior and 48 posterior colporrhaphies, 11 enterocele repairs, 5 perineorrhaphies, 1 Burch procedure, 17 total and 22 supracervical hysterectomies, and 44 mid-urethral sling procedures. The analyzed dataset of 78 subjects was characterized by the following metrics: average patient age was 58.9±10.1 years; parity of 2.4±1.0; 55 subjects had anterior POP, 50 subjects had posterior POP, and 59 had uterine POP; 4 subjects had stage I POP, 37 subjects had stage II, and 37 subjects had stage III POP.

The clinical protocol (clinical trial identifier NCT02925585) was approved by the appropriate Institutional Review Board (Western IRB and local IRB as required) and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects enrolled in the study. This clinical research was conducted in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. The VTI examination data for eight Tests were obtained and recorded at the time of the scheduled urogynecologic visits.

Total study workflow comprised of the following steps: (1) Recruiting women who had previously did not have a pelvic surgery and were scheduled for a POP surgery; (2) Acquisition of clinical diagnostic information related to the inclusion/exclusion criteria (age, POP stage, co-morbidities) by standard clinical means; (3) Subject enrollment; (4) Performing a pre-operative VTI examination in lithotomic position; (5) Performing a post-operative VTI examination (4 to 6 months after pelvic surgery); and (6) Analyzing changes in VTI parameters after the surgeries. Prior to the VTI examination, a standard physical examination was performed, including a bimanual pelvic examination and Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) [19]. The pelvic floor conditions were categorized by the stage of the prolapse based on the maximum stage from anterior, posterior, and uterine prolapse.

Statistical Analysis

The 52 biomechanical parameters were calculated automatically by VTI software version 2018.54.4.0 for each of the 156 analyzed VTI examinations (78 cases; two VTI examinations per subject). In two cases, the parameter calculation required manual correction of the anatomical location at which the parameters were required to be calculated. Specifically, the VTI software was not able to define location of the pubic bone area for parameter 7 (see Table 1) for both cases. The need in such anatomical correction (a click in VTI touchscreen) was determined by a visual review of parameter 7 location in Test 2 tactile image (e.g., see location for urethral pressure in [11], Figure 4). The two-sample t-test (p<0.05) was employed to test the null hypothesis that the data in Group 1 (positive parameter change after surgery) and Group 2 (negative parameter change after surgery) have equal means and equal variances. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated for VTI parameter change after surgery versus its pre-surgery value. The p-values for testing hypothesis to determine that there is no relationship (correlation) between the VTI parameter changes after surgery versus its pre-surgery values (null hypothesis) were calculated. No power analysis was performed.

Figure 4.

Posterior Level I pelvic support (parameter 18) change after surgery versus its pre-surgery value.

Improvement in VTI parameters after a surgical procedure signifies: (a) an increase in pressure value (kPa) at the same tissue deformation, (b) an increase in pressure gradient value (stress-to-strain ratio, kPa/mm), which relates to tissue elasticity, (c) an increase of contractive pressure or force value (kPa or N) from a pelvic muscles, (d) a decrease of muscle relaxation speed (kPa/s), or an increase in mobility of a pelvic muscle along the vagina (mm).

For visual evaluation of the analyzed data distributions, we used notched boxplots [20] showing a confidence interval for the median value (central vertical line), 25% and 75% quartiles. The spacing between the different parts of the box helps to compare variance. The boxplot also determines skewness (asymmetry) and outlier (cross). The statistical functions of MATLAB version R2018a (MathWorks, MA) were used for the data analysis.

Results

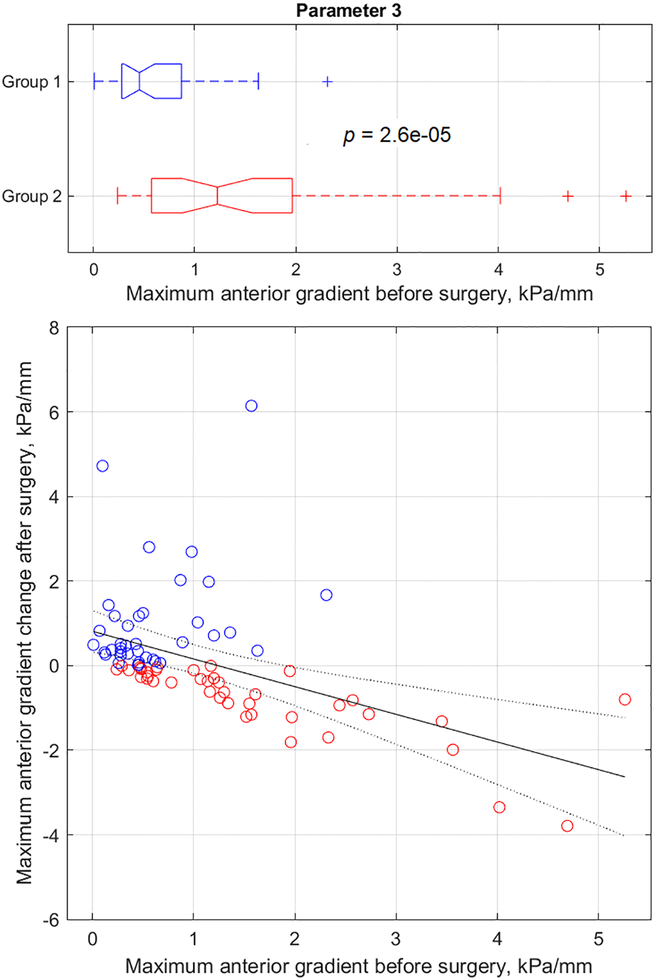

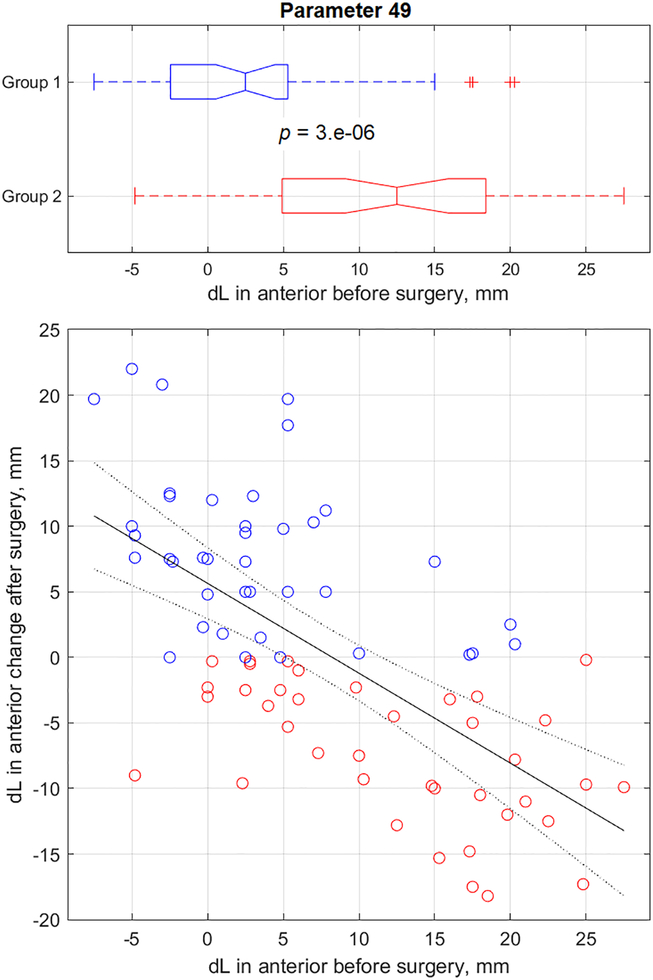

The VTI parameter change after the surgery was plotted against the same pre-surgery parameter; some of these dependencies have been presented in Figures 1–8. Positive parameter changes after surgery (Group 1) have been indicated by a blue circle, and negative parameter changes after surgery (Group 2) have been indicated by a red circle (see Figures 1–8). Group 1 and Group 2 selections are dictated only by the sign of specific parameter change after surgery (vertical axis in Figure 1–8). It is important to note that Group 1 and Group 2 were composed of the pre-surgery parameter values (horizontal axis in Figures 1–8); Group 1 and Group 2 were not composed of the after surgery parameter changes values. The boxplots in upper part in Figures 1–8 demonstrates the distribution along the horizontal axes for both groups. The two-sample t-tests were conducted for these boxplot samples, not for vertical values. These groups are different for different parameters (see Figures 1–8). The fitting bounds in Figures 1–8 represent 95% confidence intervals - the chance that a new observation will fall within these bounds.

Figure 1.

Anterior tissue elasticity change (parameter 3) after surgery versus its pre-surgery value.

Figure 8.

Urethral mobility (parameter 49) change after surgery versus its pre-surgery value (reflex contraction, cough).

The results for all 52 parameters have been presented in columns 3 to 8 of Table 2. Specifically, column 3 shows Group 1 average parameter values before surgery, column 7 shows Group 2 average parameter values before surgery, column 5 shows relative parameter change (%) in Group 1 versus Group 2, and column 6 shows p-value (t-test results) for Group1 versus Group 2 data distributions. It must be noted that all 52 t-test outcomes (column 6) have p-values in the range 4.0*10−10 to 4.3*10−2. This implies that all 52 VTI parameter changes after surgery depend on pre-surgical conditions. Column 7 in Table 2 presents correlation coefficients for VTI parameter changes after surgery versus their pre-surgery value; column 8 represents the p-value for correlation hypothesis testing. Please note that 50 of 52 testing outcomes of correlation hypothesis (column 8) have the p-value in the range 3.7*10−18 to 1.6*10−2. This signifies that after surgery changes of 50 VTI parameters correlate with pre-surgical values of these parameters. Only parameters 35 and 36 have p-value exceeding 0.05 (0.14 and 0.11) for correlation hypothesis testing with correlation coefficients−0.17 and −0.18 respectively (see columns 7 and 8 in Table 2). Parameters 35 and 36 had p-values 0.005 and 0.002 respectively for t-test of Group 1 versus Group 2 (see column 6 in Table 2).

Table 2.

VTI parameter changes after surgery and comparison of Group 1 (positive parameter change after surgery) with Group 2 (negative parameter change after surgery).

| Column 1: VTI Parameter No. |

Column 2: Parameter units |

Column 3: Group 1 average parameter value |

Column 4: Group 2 average parameter value |

Column 5: Group 1 versus Group 2 change, % |

Column 6: P-value t-test, Group1 versus Group 2 |

Column 7: Correlation coefficient for parameter change after surgery versus its pre-surgery value |

Column 8: P-value for correlation hypothesis testing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | N | 0.56 | 0.92 | −49.5 | 7.0E-05 | −0.62 | 1.4E-09 |

| 2 | mJ | 25.2 | 35.5 | −33.6 | 1.0E-03 | −0.42 | 1.2E-04 |

| 3 | kPa/mm | 0.59 | 1.55 | −88.3 | 2.0E-05 | −0.50 | 3.2E-06 |

| 4 | kPa/mm | 0.61 | 1.13 | −64.1 | 9.0E-04 | −0.38 | 6.4E-04 |

| 5 | kPa | 12.32 | 22.2 | −56.8 | 1.0E-03 | −0.46 | 2.5E-05 |

| 6 | kPa | 10.4 | 14.13 | −31.4 | 4.3E-02 | −0.32 | 4.5E-03 |

| 7 | kPa | 12.17 | 24.6 | −67.3 | 3.0E-05 | −0.62 | 1.9E-09 |

| 8 | kPa | 5.23 | 7.89 | −42.9 | 2.0E-03 | −0.54 | 3.0E-07 |

| 9 | kPa | 4.48 | 8.22 | −62.1 | 4.0E-03 | −0.56 | 1.0E-07 |

| 10 | kPa | 5.82 | 9.42 | −49.0 | 1.0E-04 | −0.43 | 8.3E-05 |

| 11 | kPa | 4.33 | 6.78 | −44.8 | 4.0E-04 | −0.46 | 2.1E-05 |

| 12 | kPa | 4.56 | 8.41 | −60.3 | 1.0E-04 | −0.69 | 2.3E-12 |

| 13 | kPa/mm | 0.84 | 2.01 | −78.2 | 3.0E-05 | −0.64 | 3.3E-10 |

| 14 | kPa/mm | 0.22 | 0.59 | −98.2 | 7.0E-07 | −0.68 | 6.7E-12 |

| 15 | kPa/mm | 0.15 | 0.48 | −119 | 4.0E-04 | −0.71 | 2.2E-13 |

| 16 | kPa/mm | 0.19 | 0.45 | −80.8 | 3.0E-04 | −0.59 | 1.6E-08 |

| 17 | kPa/mm | 0.14 | 0.35 | −85.3 | 1.0E-05 | −0.65 | 1.3E-10 |

| 18 | kPa/mm | 0.18 | 0.41 | −76.3 | 1.0E-03 | −0.68 | 6.1E-12 |

| 19 | kPa | 12.5 | 23.51 | −62.7 | 3.0E-04 | −0.55 | 2.0E-07 |

| 20 | N | 2.11 | 3.09 | −36.5 | 8.0E-04 | −0.38 | 6.2E-04 |

| 21 | N | 0.97 | 1.53 | −44.3 | 9.0E-05 | −0.51 | 2.0E-06 |

| 22 | kPa | 3.65 | 6.04 | −50.4 | 1.0E-03 | −0.62 | 1.2E-09 |

| 23 | kPa | 2.66 | 3.73 | −32.7 | 3.0E-03 | −0.57 | 3.8E-08 |

| 24 | kPa | 3.63 | 6.17 | −52.2 | 4.0E-05 | −0.48 | 7.3E-06 |

| 25 | N | 1.00 | 1.65 | −46.1 | 1.0E-03 | −0.59 | 9.5E-09 |

| 26 | kPa | 2.71 | 9.15 | −110 | 1.0E-04 | −0.45 | 4.0E-05 |

| 27 | mm | 1.46 | 9.57 | −177 | 1.0E-05 | −0.62 | 1.7E-09 |

| 28 | N | 0.90 | 1.66 | −53.5 | 1.0E-04 | −0.64 | 2.8E-10 |

| 29 | kPa | 3.95 | 6.60 | −49.3 | 1.0E-03 | −0.55 | 1.4E-07 |

| 30 | mm | −0.45 | 8.80 | −258 | 4.0E-10 | −0.72 | 1.3E-13 |

| 31 | N | 0.79 | 1.25 | −46.0 | 2.0E-03 | −0.37 | 8.3E-04 |

| 32 | kPa | 9.43 | 20.89 | −80.3 | 1.0E-04 | −0.50 | 2.8E-06 |

| 33 | kPa | 15.9 | 31.04 | −65.8 | 6.0E-05 | −0.54 | 4.3E-07 |

| 34 | N | 0.89 | 1.24 | −33.1 | 2.5E-02 | −0.31 | 6.4E-03 |

| 35 | kPa | 5.77 | 8.72 | −41.6 | 5.0E-03 | −0.17 | 1.4E-01 |

| 36 | kPa | 10.5 | 14.72 | −35.5 | 2.0E-03 | −0.18 | 1.1E-01 |

| 37 | N | 0.40 | 0.76 | −60.9 | 1.0E-03 | −0.74 | 7.4E-15 |

| 38 | kPa | 2.64 | 4.86 | −59.3 | 3.0E-03 | −0.55 | 2.3E-07 |

| 39 | kPa | 5.06 | 8.19 | −49.2 | 1.0E-03 | −0.60 | 8.3E-09 |

| 40 | N | 0.33 | 0.75 | −70.8 | 5.0E-04 | −0.79 | 3.7E-18 |

| 41 | kPa | 2.23 | 4.81 | −73.5 | 3.0E-04 | −0.52 | 9.1E-07 |

| 42 | kPa | 4.79 | 7.95 | −50.9 | 5.0E-04 | −0.53 | 5.8E-07 |

| 43 | kPa/s | −2.15 | −0.62 | 99.3 | 2.0E-03 | −0.66 | 4.5E-11 |

| 44 | %/s | −7.56 | −4.22 | 53.2 | 5.0E-03 | −0.50 | 2.7E-06 |

| 45 | kPa/s | −1.06 | −0.49 | 72.9 | 3.0E-03 | −0.58 | 1.9E-08 |

| 46 | %/s | −7.15 | −4.55 | 43.1 | 8.0E-03 | −0.36 | 1.3E-03 |

| 47 | N | 1.68 | 2.38 | −32.6 | 9.0E-04 | −0.45 | 3.6E-05 |

| 48 | kPa | 5.62 | 11.04 | −66.2 | 8.0E-04 | −0.49 | 4.2E-06 |

| 49 | mm | 3.29 | 12.19 | −114 | 3.0E-06 | −0.65 | 1.2E-10 |

| 50 | N | 1.69 | 2.58 | −39.2 | 2.0E-04 | −0.47 | 1.2E-05 |

| 51 | kPa | 7.96 | 10.01 | −22.7 | 3.9E-02 | −0.27 | 1.6E-02 |

| 52 | mm | 1.81 | 8.60 | −151 | 8.0E-06 | −0.49 | 6.3E-06 |

Discussion

The key finding of this study is that, in general, the changes in the proposed biomechanical parameters after POP surgery depend on their pre-surgical values. In other words, the biomechanical conditions of the pelvic floor prior POP surgery can predict the post-surgical changes of the parameters characterizing these biomechanical conditions. The entire analyzed set of 52 biomechanical parameters demonstrated such possibility with a high level of confidence. These parameters characterize the tissue elasticity (parameters 1–8 and 19–24), pelvic support (parameters 9–18) and pelvic functions (parameters 25–52). It is clear that soft tissue elasticity, as an intrinsic tissue property, does not change at micro-level after the pelvic surgery. What change is the measured stress-to-strain ratio, which depends on (1) possible changes in tissue stress at rest, and (b) anatomical changes involving that tissue. The changes in pelvic support parameters characterize the pressure feedback under relatively high (up to 45 mm) deformation of the pelvic support structures. These were the results of direct VTI measurements.

The pelvic function parameters require separate interpretations because they include contractive strength of multiple pelvic muscles, their involuntary relaxation, and mobility along the vagina. The interpretation of these parameters has been proposed in earlier research [9–11, 21–23]. In this study, the new findings for the pelvic function parameters are important. The first function parameter group, the muscle contraction, is straightforward. The greater the muscles’ contractive capability, measured as pressure maximum, or pressure or force change at Valsalva or during voluntary or reflex contraction, the better is the biomechanical condition of the female pelvic floor. The second function parameter group is involuntary muscle relaxation. The lower the speed of the relaxation, the better would be the pelvic muscle innervation and biomechanical condition of the female pelvic floor. The third function parameter group includes the pelvic muscle/structure motilities along the vagina. Analysis of the changes in the parameters 27 (displacement of the maximum pressure peak in anterior compartment at Valsalva maneuver), 30 (displacement of the maximum pressure peak in posterior compartment at Valsalva maneuver) and parameters 49 (displacement of the maximum pressure peak in anterior compartment at reflex contraction at cough), 52 (displacement of the maximum pressure peak in posterior compartment at reflex contraction at cough) allows one to conclude the greater the motility/mobility (directed towards the apex), the better will be the biomechanical conditions of the female pelvic floor. With this interpretation, all the analyzed data demonstrate that weak pelvic floor conditions allow greater scope for improvement in these biomechanical parameters as an outcome of POP surgery. In cases where the pelvic floor had higher/better VTI parameters, any further pelvic improvement due to POP surgery may not be significant or possible.

Based on the finding reported here, it could be concluded that patients with decreased tissue elasticity, weakened pelvic support and reduced muscle contractive strength experienced greater benefit from POP surgery. A possible explanation of the mechanism of action or “cause” of the demonstrated dependence on pre-surgery conditions is the normalization of the 3-D anatomy of the vagina, as it relates to the levator ani group below it (pelvic floor), as surgical correction of apical and lateral attachment enables the pelvic floor to have an enhanced effect “to” the vagina and pelvis. The clinical implications of these findings are that the VTI parameters may (1) predict positive biomechanical changes before POP surgery and (2) act as a warning for certain cases to be considered before POP surgery.

The strength of this study is that though the pelvic surgeries were performed by eight urogynecologists with different surgical approaches and preferences, this strong dependence on pre-surgery conditions was observed for practically all VTI parameters. The multiple measures analysis does not imply any limitations and cannot lead to the possibility of spurious statistical findings. On the contrary, in spite of the multiple surgical procedures and their combinations per subject, as well as variations in subject age and parity, the statistically significant dependences of after-surgery biomechanical changes versus pre-surgery biomechanical conditions were established.

The limitation of this study was its scope: the multivariate analysis, which considers a variety of surgical procedures or their classes, was deemed beyond the scope of this article, as it may require significant space to describe and distract from the reported finding.

In conclusion, our data indicated that POP surgery, in general, improves the biomechanical conditions and integrity of the weak pelvic floor. The VTI parameters can predict biomechanical improvements as resulting from the POP surgery. At the same time, the pre-surgery VTI parameters may serve as a “red flag” for some patients to pay more attention to pelvic floor conditions at pre- and in-surgery.

Figure 2.

Posterior tissue elasticity change (parameter 4) after surgery versus its pre-surgery value.

Figure 3.

Posterior Level II pelvic support (parameter 17) change after surgery versus its pre-surgery value.

Figure 5.

Muscle contractive strength (parameter 28) change after surgery versus its pre-surgery value (Valsalva maneuver).

Figure 6.

Muscle contractive strength (parameter 50) change after surgery versus its pre-surgery value (reflex contraction, cough).

Figure 7.

Involuntary muscle relaxation (parameter 45) change after surgery versus its pre-surgery value.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute On Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Awards Number SB1AG034714. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Siddiqui NY, Gregory WT, Handa VL, et al. American Urogynecologic Society Prolapse Consensus Conference Summary Report. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2018;24(4):260–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jeffery S, Roovers JP, Quo Vadis. Vaginal Mesh in Pelvic Organ Prolapse? Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29(8):1073–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jelovsek JE, Barber MD, Brubaker L, et al. NICHD Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Effect of Uterosacral Ligament Suspension vs Sacrospinous Ligament Fixation With or Without Perioperative Behavioral Therapy for Pelvic Organ Vaginal Prolapse on Surgical Outcomes and Prolapse Symptoms at 5 Years in the OPTIMAL Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2018;319(15):1554–1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Egorov V, van Raalte H, Sarvazyan A. Vaginal Tactile Imaging. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2010;57(7):1736–1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Egorov V, van Raalte H, Lucente V. Quantifying Vaginal Tissue Elasticity under Normal and Prolapse Conditions by Tactile Imaging. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23(4):459–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Egorov V, van Raalte H, Lucente V, et al. Biomechanical Characterization of the Pelvic Floor Using Tactile Imaging In: Hoyte L, Damaser MS, eds. Biomechanics of the Female Pelvic Floor. London, UK: Elsevier; 2016:317–348. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim K, Egorov V, Shobeiri SA. Emerging Imaging Technologies and Techniques In: Shobeiri A, ed. Practical Pelvic Floor Ultrasonography. Springer International Publishing AG: 2017;327–336. [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Raalte H, Lucente V, Ephrain S, et al. Intra- and Inter-Observer Reproducibility of Vaginal Tactile Imaging. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2016;22:S130–131. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lucente V, van Raalte H, Murphy M, et al. Biomechanical Paradigm and Interpretation of Female Pelvic Floor Conditions before a Treatment. Int J Women Health 2017;9:521–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Egorov V, Murphy M, Lucente V, et al. Quantitative Assessment and Interpretation of Vaginal Conditions. Sex Med. 2018;6(1):39–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Egorov V, Shobeiri AS, Takacs P, et al. Biomechanical mapping of the female pelvic floor: prolapse versus normal conditions. Open J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;8(10):900–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, et al. Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(4):CD004014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Easley DC, Abramowitch SD, Moalli PA. Female pelvic floor biomechanics: bridging the gap. Curr Opin Urol. 2017;27(3):262–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shobeiri SA. Practical Pelvic Floor Ultrasonography. A Multicompartmental Approach to 2D/3D/4D Ultrasonography of the Pelvic Floor. Springer International Publishing AG; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeLancey JO. Pelvic floor anatomy and pathology In: Hoyte L, Damaser MS, eds. Biomechanics of the Female Pelvic Floor. London, UK: Elsevier; 2016:13–51. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dietz HP. Pelvic Floor Ultrasound.Atlas and Text Book. Creative Commons Attribution License, Springwood Australia; 2016: 1–127. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoyte L, Ye W, Brubaker L, Fielding JR, et al. Segmentations of MRI images of the female pelvic floor: a study of inter- and intra-reader reliability. J Magn Reson Imaging 2011; 33(3): 684–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petros P The Female Pelvic Floor: Function, Dysfunction and Management According to the Integral Theory. Berlin, Germany; Springer: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bo K, et al. The Standardization of Terminology of Female Pelvic Organ Prolapse and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGill R, Tukey JW, Larsen WA. Variations of Box Plots. Am Statistician 1978;32:12–16. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Egorov V, Lucente V, van Raalte H, et al. Biomechanical mapping of the female pelvic floor: changes with age, parity and weight. Pelviperineology 2019; 38: 3–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoyte L, Egorov V. Preoperative biomechanical mapping of the female pelvic floor. Global Imaging Insights 2018; 3(5): 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Egorov V, Lucente V, Shobeiri AS, et al. Biomechanical mapping of the female pelvic floor: uterine prolapse versus normal conditions. EC Gynaecol. 2018;7(11):431–446. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]