Abstract

HIV-1 reverse transcriptase (RT) is an essential enzyme, targeting half of approved anti-AIDS drugs. While nucleoside RT inhibitors (NRTIs) are DNA chain terminators, the nucleotide-competing RT inhibitor (NcRTI) INDOPY-1 blocks dNTP binding to RT. Lack of structural information hindered INDOPY-1 improvement. Here we report the HIV-1 RT/DNA/INDOPY-1 crystal structure, revealing a unique mode of inhibitor binding at the polymerase active site without involving catalytic metal ions. The structure may enable new strategies for developing NcRTIs.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

HIV-1 RT is an asymmetric heterodimer consisting of p66 and p51 subunits. During HIV-1 replication, RT converts the single-stranded viral genomic RNA into double-stranded DNA. NRTIs and NNRTIs are key components in the antiretroviral therapy (ART) for treating HIV-1 infection; drug-resistance mutations are selected in response to both. With the inability to create an effective vaccine and the continuing spread of HIV, the World Health Organization recommends ART for infected individuals.1 There is a need to discover novel antiretrovirals, as long-term use of existing antivirals can lead to drug resistance; some of the existing drugs have been phased out.2

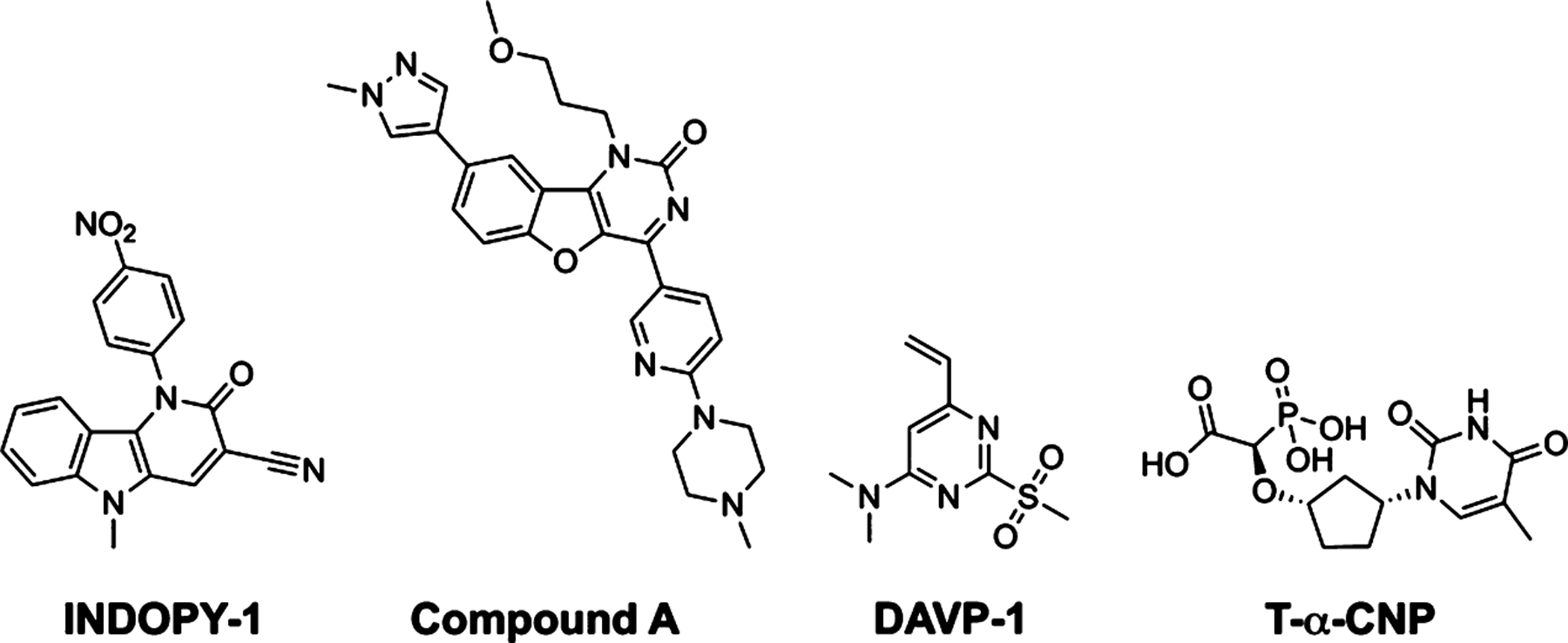

INDOPY-1 (Figure 1B) was the first NcRTI discovered, displaying reversible competitive inhibition of dNTP binding.3,4 Biochemical studies showed that INDOPY-1 arrests RT/DNA in a post-translocated (P site) complex. In addition, its potency was markedly increased when supplemented with a physiological concentration of ATP. Time-course experiments showed a “hot spot” for inhibition following the incorporation of pyrimidines [deoxythymidine (dT) > deoxycytidine (dC)] at the primer terminus.3 While the potency of INDOPY-1 is unaffected by NNRTI- or multidrug-NRTI resistance, NRTI-resistance mutations M184V and Y115F are associated with decreased INDOPY-1 susceptibility, while K65R, associated with tenofovir (see Chart S1 in Supporting Information for formula) resistance, confers increased susceptibility to INDOPY-1.5 Other NcRTIs (Chart 1) are DAVP-1, an allosteric inhibitor binding at a hinge between the palm and thumb subdomains that may distort the dNTP-binding site (N site),6 and T-α-CNP, a metal-chelating dNTP-mimic that inhibits several DNA polymerases.7,8 The benzofuropyridinone scaffold (e.g., compound A), with a different chemotype than INDOPY-1, exhibits the same mechanism of inhibition of stalling P complexes.8 Here we present the crystal structure of the HIV-1 RT/DNA/INDOPY-1 ternary complex at 2.4 Å resolution. The structure provides a detailed understanding of the INDOPY-1 mechanism of action, a rationale for its distinctive resistance mutation profile with respect to NRTIs, and a basis for rational design of this NcRTI class of inhibitors.

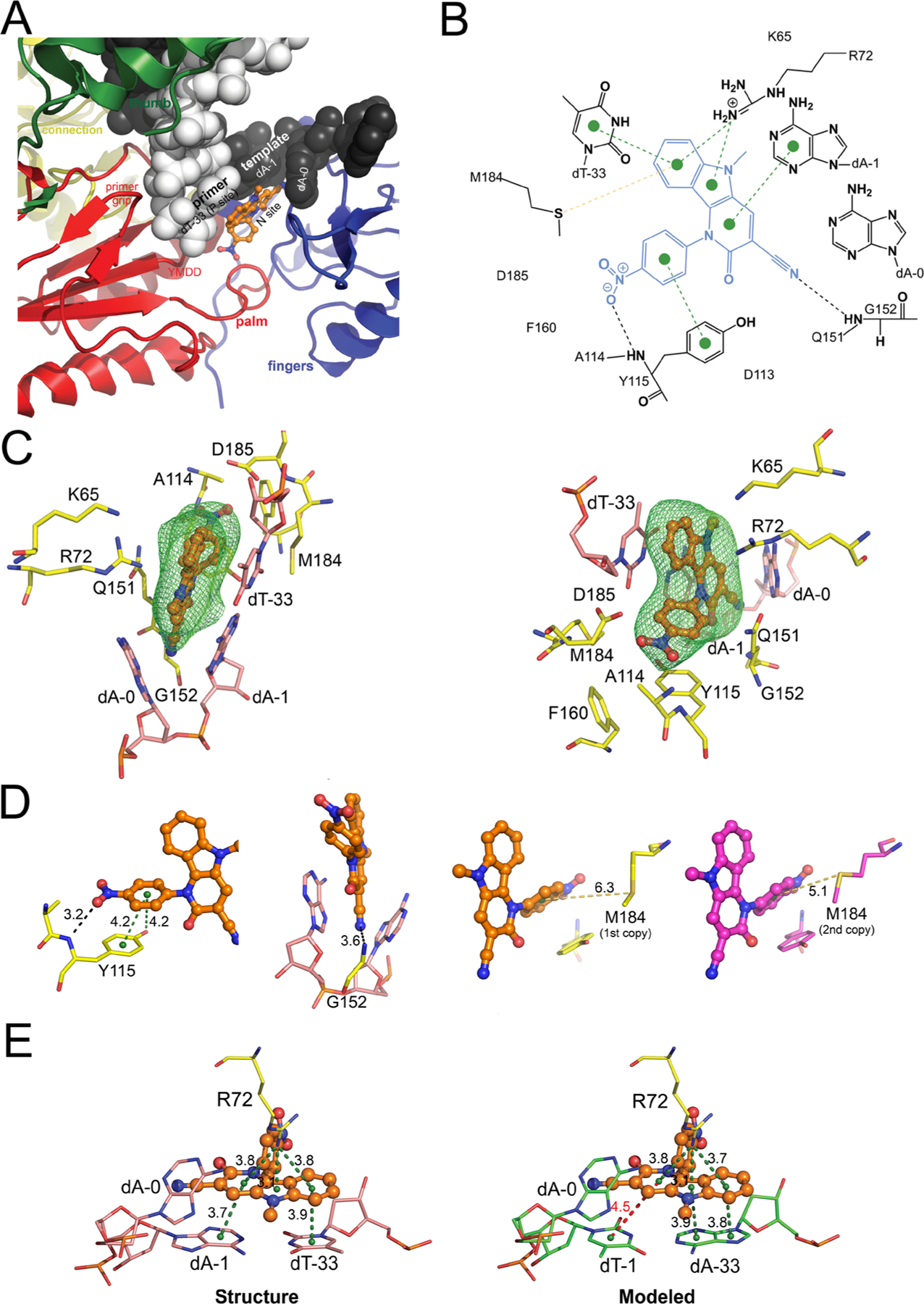

Figure 1.

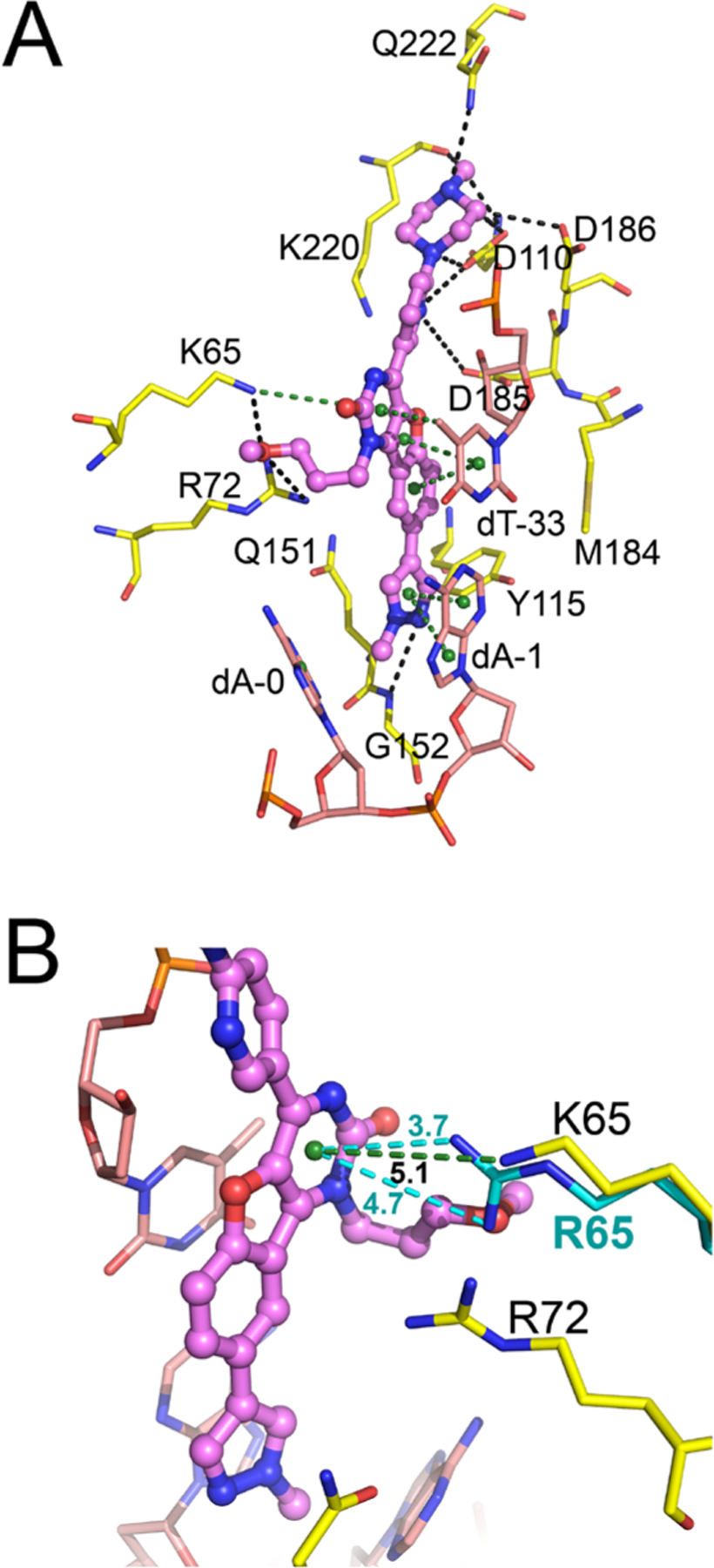

Binding of INDOPY-1 to the HIV-1 RT/DNA complex. (A) Close-up view of INDOPY-1 binding to HIV-1 RT/DNA, with subdomains, motifs, N (nucleotide-binding or pretranslocation) site and P (priming or post-translocation) site indicated. (B) 2D-interaction diagram of INDOPY-1 (blue) with HIV-1 RT/DNA [dashed lines color code: black, hydrogen bonds/polar contacts; green, π–π stacking (dotted lines) and cation-π; yellow, sulfur-π]. (C) Two views of the atomic model of INDOPY-1 (orange) bound to HIV-1 RT active site residues (yellow) and DNA (pink), with difference Polder Fo – Fc map (green mesh, 4.5σ). (D) Zoomed-in view of the Y115, G152, and M184 interactions with INDOPY-1. (E) Zoomed-in view of the stacking module in the structure and in a model where the A:T base pair is switched; interactions as in (B) except for the red dashed line indicating reduced π–π stacking.

Chart 1.

Chemical Structures of the Reported NcRTI Chemotypes

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The mechanism of HIV-1 RT inhibition by INDOPY-1 has been previously characterized biochemically, showing that its binding site overlaps with the N site.3,5,9 Given the highly flexible nature of RT/DNA complexes and uncertainty of binding location, we wanted to experimentally elucidate the interactions of INDOPY-1 in the complex at atomic detail. Attempts to soak or cocrystallize INDOPY-1 with RT/DNA cross-linked complexes were unsuccessful. Use of a 38-mer hairpin aptamer [Apt, which mimics a template-primer DNA (T–P)] provided a stable RT/DNA catalytic polymerase complex that enabled the structural study of foscarnet as a pyrophosphate mimic.10,11 In the current study, the Apt sequence was modified for the primer-terminal base pair as dA:dT (T–P), in order to introduce the aforementioned hot spot for INDOPY-1 binding (Chart S2).3

The determination of the ternary complex of RT/Apt/INDOPY-1 (hereafter called RT/DNA/INDOPY-1, Table 1) was enabled by an approach for enhancing solubility of INDOPY-1 in the crystal soaking process and combining data from multiple crystals (see Experimental Section), leading to improved electron density for INDOPY-1 (Figure S1A). A Polder omit map, calculated by excluding the bulk solvent around the omitted region, clearly showed the difference electron density for INDOPY-1 (Figure 1C).12 The RT/DNA/INDOPY-1 structure (Protein Data Bank, PDB code 6O9E) contains two copies of the complex in the asymmetric unit, and the overall structure of the two copies is almost identical (Cα rmsd = 0.54 Å). Slight differences exist in the active site region, described below. INDOPY-1 stacks with the T–P base pair at the 3′-end of the primer and intercalates between the template nucleotides of the first base pair and the first base overhang. INDOPY-1 also interacts with RT residues R72, Y115, G152, and M184 (Figure 1) and extensively overlaps with the nucleoside moiety of a dNTP substrate (Figures 1A, 2C, and 3C). INDOPY-1 binding to RT/DNA can be dissected into three modules. (i) Stacking module: the indolopyridone ring system has π−π stacking with the terminal T–P base pair and makes a cation-π interaction with the highly conserved R72 (Figure 1E). (ii) Intercalation module: the cyano group intercalates between template bases dA-0 and dA-1 and is hydrogen-bonded with G152 (Figure 1D). (iii) Ribose ring replacement module: the p-nitrophenyl moiety contacts RT residues Y115 (π stacking with the side chain and hydrogen bonding with the main chain, mimicking the sugar ring of a dNTP, Figures 1D and S1B) and M184 (sulfur-π interaction, Figure 1D).

Table 1.

Data Collection and Refinement Statisticsa

| HIV-1 RT/DNA/INDOPY-1 | |

|---|---|

| PDB code | 6O9E |

| wavelength (Å) | 0.98 |

| number of merged data sets | 3 |

| resolution range (Å) | 50.0—2.40 (2.44—2.40) |

| space group | P21 |

| unit cell (Å) | 89.76, 127.66, 131.61 |

| angle (deg) | 90, 101.5, 90 |

| unique reflections | 113 545 (5622) |

| redundancy | 19.0 (19.5) |

| completeness (%) | 100.0 (100.0) |

| mean I/σ(I) | 11.6 (0.8) |

| Wilson B-factor (Å2) | 73.60 |

| Rmerge | 0.162 (6.118) |

| Rmeas | 0.171 (6.45) |

| Rpim | 0.055 (2.035) |

| CC1/2 | 0.994 (0.311) |

| Rwork | 0.2030 (0.4004) |

| Rfree | 0.2416 (0.4325) |

| number of atoms | 17 591 |

| macromolecules | 17 297 |

| ligands | 183 |

| water molecules | 111 |

| protein residues | 1931 |

| rms bonds (Å) | 0.002 |

| rms angles (deg) | 0.489 |

| Ramachandran favored (%) | 96.8 |

| Ramachandran allowed (%) | 3.2 |

| Ramachandran outliers (%) | 0.05 |

| rotamer outliers (%) | 0.57 |

| clashscore | 10.90 |

| average B-factor (Å2) | 126.35 |

| macromolecules | 126.32 |

| ligands | 153.03 |

| water molecules | 87.38 |

| Nnumber of TLS groups | 25 |

Statistics for the highest-resolution shell are shown in parentheses.

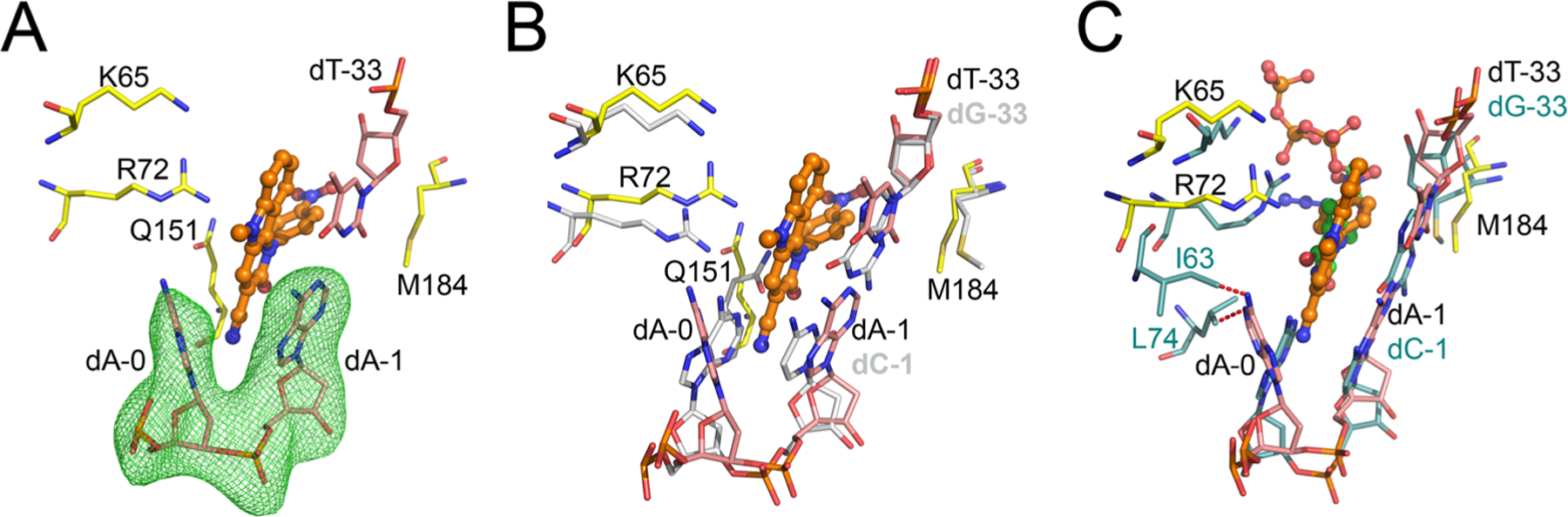

Figure 2.

Structural basis of INDOPY-1 preference for P-site complexes. (A) Atomic model of INDOPY-1 binding to HIV-1 RT/DNA, as in Figure 1C, except that the difference Polder Fo – Fc map (green mesh, 5σ) calculation omits nucleotides dA-0 and dA-1. (B) Superposition of HIV-1 RT/DNA/INDOPY-1 with the HIV-1 RT/DNA binary P complex (residues in silver, PDB code 5D3G). (C) Superposition of HIV-1 RT/DNA/INDOPY-1 onto the N-site HIV-1 RT/DNA/AZT triphosphate (AZT-TP) complex (protein and DNA in turquoise sticks, AZT-TP in green sticks, PDB code 5I42); predicted steric clashes (<2 Å) indicated with red dashed lines.

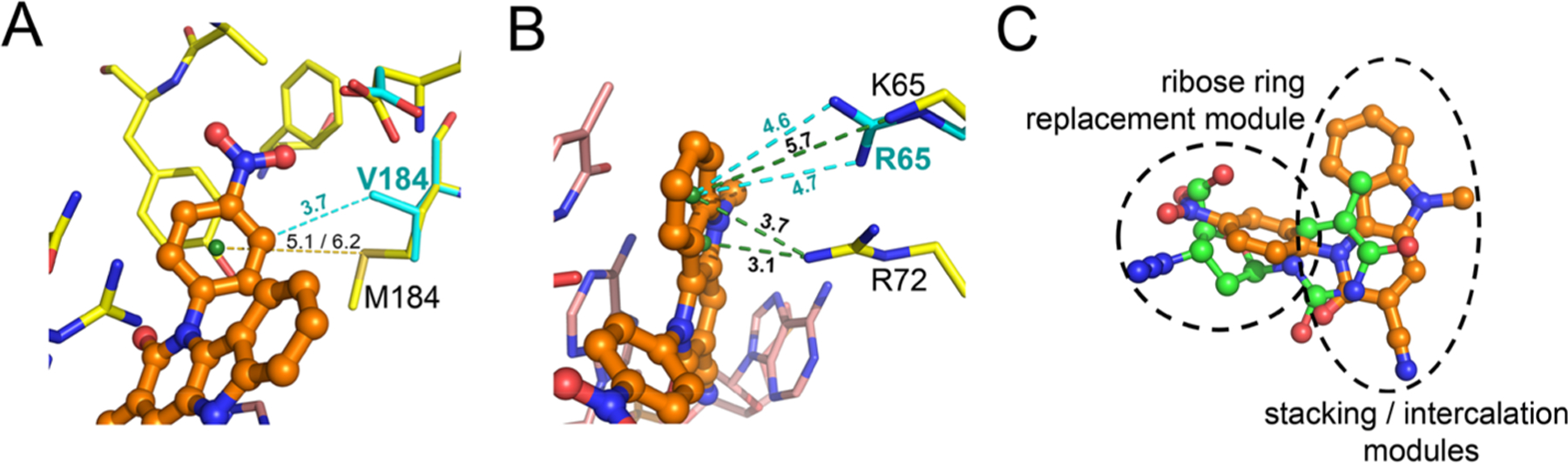

Figure 3.

Modeling of the effects of the most prevalent resistance mutations on INDOPY-1 binding. (A) M184 sulfur-π interaction with INDOPY-1 (yellow dashes, distances for both copies of the complex present in the asymmetric unit) and M184V hydrophobic contact (cyan dashes). (B) Wild-type and K65R RT cation-π interactions (distances in green and in cyan dashes, respectively). (C) Crystallographic overlay of the nucleoside moiety of AZT-TP (PDB code 5I42) and INDOPY-1 (present structure). INDOPY-1 moieties are highlighted.

Remarkably, the largest change associated with INDOPY-1 binding occurs in the DNA. The compound binding forces the base of the template overhang dA-0 to swivel ~50° toward the fingers subdomain, preventing closure of the fingers through steric hindrance. If the fingers subdomain were to remain closed [as in a pretranslocated (N) complex], I63 and L74 would have steric hindrance with the adenine moiety of the displaced dA-0 (Figure 2). In the structure, dA-0 interacts favorably with I63 and L74 (Figure S1B). However, this is not related to INDOPY-1 binding: biochemical studies showed that an abasic nucleotide in place of dA-0 does not affect INDOPY-1 binding.5 The dA-0 conformation varies between the two asymmetric unit copies (fully open and less open conformation, Figure S2C), with no apparent effect on compound binding. An abasic nucleotide at the dA-1 position, however, prevents INDOPY-1 binding.5 This shows the importance of the stacking between the cyanopyridone ring and the dA-1 base. Modeling alternative base pairs in the structure dA-1–dT-33 (see Experimental Section) suggests that the binding hot spot for purine (R)-pyrimidine (Y) is due to stacking of all three rings in the indolopyridone, whereas for Y–R the reduced stacking significantly impairs binding (see dT-1 in Figure 1E). The structure does not provide a direct explanation for the enhancing effect of ATP in INDOPY-1 inhibition of HIV-1 RT polymerization (IC50 from 76.3 to 10.7 nM). Evidence points to the existence of a quaternary complex with INDOPY-1 and ATP.9 The polymerase active site in the RT/DNA/INDOPY-1 complex has enough unoccupied volume to accommodate an ATP,9 as in pre-excision complexes.13 The triphosphate moiety of ATP could chelate metal ion B, compensating for the charges at the active site, and improve the binding affinity of INDOPY-1, which lacks a chelating group (Figure S3A).14

The RT/DNA/INDOPY-1 structure also provides a rationale for the distinctive resistance mutation profile of INDOPY-1: Y115F and M184V decrease INDOPY-1 susceptibility, and K65R increases it.5 We have used the structure to understand the effects of these mutations (see Supporting Information results). Y115F mutation increases dNTP binding affinity (~3-fold) presumably by improved π stacking (Figure S1B).5 For M184V (INDOPY-1 binding reduced 6-fold), the rationale is not very clear. In the structure, M184 exhibits a sulfur-π interaction with the p- nitrophenyl moiety, and this interaction is lost in the M184V mutant. Sulfur-aromatic interactions are very frequent in proteins for stabilizing internal motif structures,15,16 but their effects on ligand binding have not been thoroughly studied.17 The sulfur-π interactions seem to provide additional stabilization over purely hydrophobic interactions at longer distances (~5–6 Å).16 The loss of the sulfur-π interaction in M184V may account for the decrease in INDOPY-1 binding. In fact, there are several examples of known disease-related M to V mutations, where M is in proximity to an aromatic ring.16 However, our modeling shows that M184V RT may still have favorable hydrophobic interaction with INDOPY-1 (Figure 3A). Additionally, the M184V/I mutation can affect INDOPY-1 binding by repositioning of the T–P.18 This hypothesis is in agreement with the fact that INDOPY-1 binding is sensitive to any alteration to the base pair.5 Concerning the K65R hyper-susceptibility, the K65 amino group is ~5 Å from INDOPY-1. Modeling suggests that R65 may be able to establish a stronger cation-π interaction with INDOPY-1 than K65 of the wild type (Figure 3B). INDOPY-1 is active against several HIV-1 strains in clades M and O, against HIV-2 and SIV, but does not inhibit other polymerases,3,19,20 which suggests a common mode of INDOPY-1 binding to HIV-1, HIV-2, and SIV RTs. The present structure permits assessment of the pharmaco-phoric requirements for INDOPY-1 binding and its difference with NRTIs and other NcRTI classes (Table 2, Table S1, Figure S3B, and Supporting Information results). Extensive structure-activity relationships (SAR) with INDOPY-1 derivatives have been reported from industry and academia (Table S2). These SAR analyses showed the nitro group is indispensable for inhibition.

Table 2.

Residues Interacting with INDOPY-1 in HIV-1 RT and Other Polymerasesa

| enzyme | residues | polymerase type | inhibition by IND | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-1 RT | R72 | Y115 | G152 | M184 | RdDp | yes |

| HIV-2 RT | R | Y | G | M | RdDp | yes |

| simian immunodeficiency virus RT | R | Y | G | M | RdDp | yes |

| S. cerevisiae Ty3 RT | R | Y | G | L | RdDp | not tested |

| avian myeloblastosis virus RT | R | F | G | M | RdDp | not tested |

| hepatitis B virus RT | R | F | G | M | RdDp | not tested |

| prototype foamy virus RT | R | F | G | V | RdDp | not tested |

| Moloney murine leukemia virus RT | R | F | G | V | RdDp | no |

| herpes simplex virus type 1 POL | I | Y | L | T | DdDp | no |

| vaccinia virus POL | T | Y | K | T | DdDp | no |

| human DNA POL β | gap | gap | gap | gap | DdDp | no |

| human DNA POL α | E | Y | gap | T | DdDp | no |

| hepatitis C virus NS5B POL | R | D | G | G | RdRp | not tested |

| human poliovirus type 1 3D POL | R | D | G | G | RdRp | no |

| coxsackievirus B3 POL | R | D | G | G | RdRp | no |

| human rhinovirus 16 3D POL | R | D | G | G | RdRp | no |

| Zika virus NS5 POL | R | D | G | G | RdRp | not tested |

Abbreviations: RT, reverse transcriptase; POL, polymerase; RdDp, RNA-dependent DNA polymerase; DdDp, DNA-dependent DNA polymerase; RdRp, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase.

Given the known pharmacological liabilities of nitro-substituted benzene derivatives,21 replacement of the p-nitrophenyl group by a sugar moiety, e.g., a ribose ring with suitable linking stereochemistry, could be advantageous (Figures 2C and 3C) and could yield a chemical scaffold bearing a sugar-like moiety linked to a cyanoindolopyridone, which could be extended to other polymerases.22,23 The comparison of the residues that interact with INDOPY-1 in HIV-1 RT and other polymerases (Table 2, Table S1, and Supporting Information results) suggests that hepatitis B RT may also be inhibited by INDOPY-1 and that RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RdRp, e.g., hepatitis C NS5B polymerase, Zika virus NS5 polymerase) could be targeted with appropriately designed INDOPY-1 derived analogs. In RdRps, the equivalent residues to R72 and G152 in HIV-1 RT are conserved, which may point to the conservation of the necessary interactions for binding of the stacking and intercalation modules of INDOPY-1 (Figure 3C). Thus, appropriate replacement of the INDOPY-1 p-nitrophenyl moiety could yield an indolopyridone derivative able to inhibit RdRPs.

Boehringer Ingelheim screened for NcRTIs with novel chemotypes, using assay conditions to favor inhibition with a similar mechanism as INDOPY-1. They discovered a benzofuranopyrimidone scaffold, exemplified by the lead compound A (Chart 1).8 Its main features are (i) potency against Y115F and M184V RT, (ii) hypersusceptibility to K65R RT, and (iii) decrease in potency against W153L (see Supporting Information results). Additionally, compound A also has a hot spot for inhibition following a dT-terminated primer.24 To understand this distinct activity spectrum of compound A and probe the present structure, we performed a rigid molecular docking (see Supporting Information results) at the INDOPY-1 binding site of RT/DNA/INDOPY-1 structure. Notably, the best pose obtained (Figure 4A) displays INDOPY-1-like stacking of the benzofuranopyrimidone core with the nucleotide base pair at the primer 3′-end and intercalation between the template bases d-0 and dA-1. The methylpiperazinylpyridine moiety interacts with the catalytic residues D110, D185, and D186 (Figure 4A). The methoxypropyl group protrudes toward the fingers subdomain near R72 and K65, the latter displaying a hydrogen bond with the methoxy oxygen and a cation-π interaction with the pyrimidone moiety (Figure 4A). K65R hypersusceptibility may likely stem from a stronger cation-π interaction than in the wild type (Figure 4B), similar to that of INDOPY-1, suggesting a structurally and functionally favorable docked pose of compound A.

Figure 4.

Binding of compound A to HIV-1 RT/DNA. (A) Atomic model of compound A (violet) bound to HIV-1 RT (yellow) and DNA (pink), displaying the best pose from molecular docking (dashed lines color code as in Figure 1B). (B) Zoomed-in view of the cation-π interaction between K65 (and K65R, cyan) and the pyrimidone ring of compound A.

CONCLUSION

In summary, we have solved the structure of HIV-1 RT/DNA in complex with the NcRTI INDOPY-1 at 2.4 Å resolution by means of enhancing the solubility of INDOPY-1 in the crystal soaking process and combining the data from multiple crystals. The structure reveals a unique mode of inhibitor binding at the polymerase active site involving interactions with key conserved RT residues. Identification of modules in INDOPY-1 for stacking with the terminal DNA base pair, intercalation with the first overhang template base, and replacement of the ring of an incoming substrate suggests strategies extending NcRTI inhibition to other polymerases. The utility of the present structure as a receptor for in silico screening underlines its value for rational design of NcRTIs. Overall, this structure provides a foundation for designing and developing novel compounds to treat HIV/AIDS as well as other human diseases.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

RT Expression and Purification.

The HIV-1 RT plasmid RT152A codes for coexpression of p66Δ555 and p51Δ428 bearing the following mutations in p66: C280S, D498N; in p51, C280S. The protein was cloned, expressed, and purified as previously reported.11 Apt (Chart S2) was custom synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies.

Crystallography.

The complex of RT and Apt was set up by mixing RT at a concentration of 85 μM (10 mg mL−1) with a 1.2-fold excess of previously annealed Apt. Crystals of the binary RT/DNA were obtained as described previously.10,11 The RT/DNA complex was mixed in a 1:1 ratio with well solution: 10–12% (w/v) PEG 8000, 50 mM Bis-Tris propane, pH 7.2, 50 mM ammonium sulfate, 5% (v/v) glycerol, 5% (w/v) sucrose, and experimentally optimized microseeds from previously generated crystals (preseeding), in a ~4 μL hanging drop over a 1 mL well. Plates were incubated for at least 7–14 days at 4 °C. Cocrystallization and soaking using the previous conditions were unsuccessful.10,11 Failed attempts revealed that INDOPY-1 water insolubility and moderate DMSO solubility (25 mM, https://aidsreagent.org/pdfs/ds11720_001.pdf) may hamper complex formation. Different solubilization strategies were assayed to maximize the INDOPY-1 effective concentration (see Supporting Information). The determination of the ternary complex structure was made possible by a combination of improvements in postcrystallization treatments and data processing. An amount of ~0.3 mg of INDOPY-1 was directly dissolved in 50 μL of cryosolution composed of reservoir with 15% PEG8K and 15% PEG400 (v/v). After incubation overnight at 4 °C, aggregates were eliminated through centrifugation at 14 000g. The supernatant was used to soak a dozen RT/DNA crystals overnight. Data collection was done at APS beamline 23-ID-D. Three data sets were processed with iMOSFLM,25 scaled and merged with AIMLESS,26 and solved with Phaser,27 using the RT/Apt (PDB code 5D3G) as starting model. Merging yielded improved electron density of INDOPY-1 (Figure S1A). The structure was refined using Phenix,28 and TLS refinement was done as in ref 11. Coot29 was used for manual corrections. INDOPY-1 restraints were created with the grade Web Server.30 Polder map12 validation (see Supporting Information results) confirmed INDOPY-1 presence in the structure. The crystallographic data and refinement statistics are listed in Table 1. Figures were prepared with PyMol.31

Docking Simulations, Modeling, and Sequence Alignments.

AutoDock 4.232 was used to perform molecular docking. The RT/DNA/INDOPY-1 structure was stripped of INDOPY-1 and all solvent molecules. Redocking, i.e., docking of the receptor with the crystallized ligand, was done as control. The superposition of the redocked INDOPY-1 molecule was in very good agreement with the crystallographic INDOPY-1 molecule (Figure S4). Compound A coordinates were generated with the grade Web Server.30 For more detailed methods, see Supporting Information. To analyze the results, the AutoDock docking clustering, rmsd, and the literature biological data were considered. Figures were prepared with PyMol,31 and additional results are displayed in Table S3. For modeling alternative base pairs substituted for the template-primer (T-P) base pair at the 3′-end of the primer and the effect of INDOPY-1 resistance mutations, we mutated the corresponding nucleotides/amino acids in Coot,29 and MOE QuickPrep was used.33 Multiple sequence alignments were done with mTM-align34 and SuperPose35 of HIV-1 RT with other RTs and other relevant DNA and RNA polymerases, including those assayed with INDOPY-1 (Table 2, Tables S1 and S2, and alignments in Supporting Information).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to APS staff members for support and access to beamline 23-ID-D for data collection, to Dr. Sergio Martinez and Dr. Dirk Jochmans for helpful discussions, and to Natalie Losada for assistance with figures. INDOPY-1 was obtained through the NIH AIDS Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH (from Tibotec BVBA). This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health MERIT Award R37 AI027690 to E.A.

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- RT

reverse transcriptase

- NRTI

nucleoside RT inhibitor

- NcRTI

nucleotide-competing RT inhibitor

- NNRTI

non-nucleoside RT inhibitor

- T–P

template-primer

- Apt

38-mer hairpin DNA aptamer

- P complex

post-translocated complex

- N complex

pretranslocated complex

- RdRp

RNA-dependent RNA polymerases

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.jmed-chem.9b01289.

Molecular formula strings (XLSX)

Additional information supporting the main manuscript is provided: (i) tables summarizing the multiple sequence alignments, SAR of reported INDOPY-1 analogs, and molecular docking information; (ii) schemes displaying all the molecular formulas present in the text and the aptamer used; (iii) figures illustrating further detail of data processing, analysis of the present structure, and comparison with related structures and docking analysis; (iv) mass spectrum of the INDOPY-1 molecule soaked into the RT/DNA crystals; (v) multiple sequence alignments (PDF)

Accession Codes

RT/DNA/INDOPY-1 has been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB code 6O9E). Atomic coordinates and experimental data will be released upon article publication. The deposition validation file is also provided.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Piot P; Abdool Karim SS; Hecht R; Legido-Quigley H; Buse K; Stover J; Resch S; Ryckman T; Mogedal S; Dybul M; Goosby E; Watts C; Kilonzo N; McManus J; Sidibe M; UNAIDS—Lancet Commission.. Defeating AIDS—advancing global health. Lancet 2015, 386, 171–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Waheed AA; Tachedjian G Why Do We Need New Drug Classes for HIV Treatment and Prevention? Curr. Top. Med. Chem 2016, 16, 1343–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Jochmans D; Deval J; Kesteleyn B; Van Marck H; Bettens E; De Baere I; Dehertogh P; Ivens T; Van Ginderen M; Van Schoubroeck B; Ehteshami M; Wigerinck P; Gotte M; Hertogs K Indolopyridones inhibit human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase with a novel mechanism of action. J Virol 2006, 80, 12283–12292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Zhang Z; Walker M; Xu W; Shim JH; Girardet JL; Hamatake RK; Hong Z Novel nonnucleoside inhibitors that select nucleoside inhibitor resistance mutations in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2006, 50, 2772–2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Ehteshami M; Scarth BJ; Tchesnokov EP; Dash C; Le Grice SF; Hallenberger S; Jochmans D; Gotte M Mutations M184V and Y115F in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase discriminate against “nucleotide-competing reverse transcriptase inhibitors”. J. Biol. Chem 2008, 283, 29904–29911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Freisz S; Bec G; Radi M; Wolff P; Crespan E; Angeli L; Dumas P; Maga G; Botta M; Ennifar E Crystal structure of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase bound to a non-nucleoside inhibitor with a novel mechanism of action. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2010, 49, 1805–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Balzarini J; Das K; Bernatchez JA; Martinez SE; Ngure M; Keane S; Ford A; Maguire N; Mullins N; John J; Kim Y; Dehaen W; Vande Voorde J; Liekens S; Naesens L; Götte M; Maguire AR; Arnold E Alpha-carboxy nucleoside phosphonates as universal nucleoside triphosphate mimics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2015, 112, 3475–3480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Rajotte D; Tremblay S; Pelletier A; Salois P; Bourgon L; Coulombe R; Mason S; Lamorte L; Sturino CF; Bethell R Identification and characterization of a novel HIV-1 nucleotide-competing reverse transcriptase inhibitor series. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2013, 57, 2712–2718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Ehteshami M; Nijhuis M; Bernatchez JA; Ablenas CJ; McCormick S; de Jong D; Jochmans D; Gotte M Formation of a quaternary complex of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase with a nucleotide-competing inhibitor and its ATP enhancer. J. Biol. Chem 2013, 288, 17336–17346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Das K; Balzarini J; Miller MT; Maguire AR; DeStefano JJ; Arnold E Conformational states of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase for nucleotide incorporation vs pyrophosphorolysis-binding of foscarnet. ACS Chem. Biol 2016, 11, 2158–2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Miller MT; Tuske S; Das K; DeStefano J; Arnold E Structure of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase bound to a novel 38-mer hairpin template-primer DNA aptamer. Protein Sci. 2016, 25, 46–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Liebschner D; Afonine PV; Moriarty NW; Poon BK; Sobolev OV; Terwilliger TC; Adams PD Polder maps: improving OMIT maps by excluding bulk solvent. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 2017, 73, 148–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Tu X; Das K; Han Q; Bauman JD; Clark AD Jr.; Hou X; Frenkel YV; Gaffney BL; Jones RA; Boyer PL; Hughes SH; Sarafianos SG; Arnold E Structural basis of HIV-1 resistance to AZT by excision. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 2010, 17, 1202–1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Das K; Bauman JD; Clark AD; Frenkel YV; Lewi PJ; Shatkin AJ; Hughes SH; Arnold E High-resolution structures of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase/TMC278 complexes: Strategic flexibility explains potency against resistance mutations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2008, 105, 1466–1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Ringer AL; Senenko A; Sherrill CD Models of S/pi interactions in protein structures: comparison of the H2S benzene complex with PDB data. Protein Sci. 2007, 16, 2216–2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Valley CC; Cembran A; Perlmutter JD; Lewis AK; Labello NP; Gao J; Sachs JN The methionine-aromatic motif plays a unique role in stabilizing protein structure. J. Biol. Chem 2012, 287, 34979–34991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Beno BR; Yeung KS; Bartberger MD; Pennington LD; Meanwell NA A Survey of the role of noncovalent sulfur interactions in drug design. J. Med. Chem 2015, 58, 4383–4438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Sarafianos SG; Das K; Clark AD; Ding J; Boyer PL; Hughes SH; Arnold E Lamivudine (3TC) resistance in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase involves steric hindrance with β-branched amino acids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1999, 96, 10027–10032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Balzarini J; Menni M; Das K; van Berckelaer L; Ford A; Maguire NM; Liekens S; Boehmer PE; Arnold E; Gotte M; Maguire AR Guanine alpha-carboxy nucleoside phosphonate (G-alpha-CNP) shows a different inhibitory kinetic profile against the DNA polymerases of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and herpes viruses. Biochem. Pharmacol 2017, 136, 51–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Jegede O; Khodyakova A; Chernov M; Weber J; Menendez-Arias L; Gudkov A; Quinones-Mateu ME Identification of low-molecular weight inhibitors of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase using a cell-based high-throughput screening system. Antiviral Res. 2011, 91, 94–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Meanwell NA Synopsis of some recent tactical application of bioisosteres in drug design. J. Med. Chem 2011, 54, 2529–2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Mullins ND; Maguire NM; Ford A; Das K; Arnold E; Balzarini J; Maguire AR Exploring the role of the alpha-carboxyphosphonate moiety in the HIV-RT activity of alpha-carboxy nucleoside phosphonates. Org. Biomol. Chem 2016, 14, 2454–2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Zhang S; Zhang J; Gao P; Sun L; Song Y; Kang D; Liu X; Zhan P Efficient drug discovery by rational lead hybridization based on crystallographic overlay. Drug Discovery Today 2019, 24, 805–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Xu HT; Colby-Germinario SP; Quashie PK; Bethell R; Wainberg MA Subtype-specific analysis of the K65R substitution in HIV-1 that confers hypersusceptibility to a novel nucleotide-competing reverse transcriptase inhibitor. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2015, 59, 3189–3196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Battye TGG; Kontogiannis L; Johnson O; Powell HR; Leslie AGW iMOSFLM: a new graphical interface for diffraction-image processing with MOSFLM. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr 2011, 67, 271–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Evans PR; Murshudov GN How good are my data and what is the resolution? Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr 2013, 69, 1204–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).McCoy AJ; Grosse-Kunstleve RW; Adams PD; Winn MD; Storoni LC; Read RJ Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr 2007, 40, 658–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Adams PD; Afonine PV; Bunkoczi G; Chen VB; Davis IW; Echols N; Headd JJ; Hung L-W; Kapral GJ; Grosse-Kunstleve RW; McCoy AJ; Moriarty NW; Oeffner R; Read RJ; Richardson DC; Richardson JS; Terwilliger TC; Zwart PH PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macro-molecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr 2010, 66, 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Emsley P; Lohkamp B; Scott WG; Cowtan K Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr 2010, 66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Smart OS; Womack TO; Sharff A; Flensburg C; Keller P; Paciorek W; Vonrhein C; Bricogne G Grade, version 1.105; Global Phasing Ltd., Cambridge, U.K., 2018; http://www.globalphasing.com/. [Google Scholar]

- (31).DeLano WL The PyMol Molecular Graphics System; DeLano Scientific: San Carlos, CA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Morris GM; Huey R; Lindstrom W; Sanner MF; Belew RK; Goodsell DS; Olson AJ AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem 2009, 30, 2785–2791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).MOE, version 2013.08; Chemical Computing Group ULC (1010 Sherbrooke St. West, Suite No. 910, Montreal, QC, H3A 2R7, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Dong R; Peng Z; Zhang Y; Yang J mTM-align: an algorithm for fast and accurate multiple protein structure alignment. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 1719–1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Maiti R; Van Domselaar GH; Zhang H; Wishart DS SuperPose: a simple server for sophisticated structural superposition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, W590–W594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.