To the Editor:

We read with interest the article by Zou et al (1), published in the recent issue of Critical Care Medicine, detailing their experience using Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II scores in a cohort of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China and feel it deserves further discussion. The study by Zou et al (1) presented data where patients had an average APACHE II score of 15.05, which is very similar to the mean APACHE II score of 15.0 in the 10,492 critically unwell COVID-19 patients in the United Kingdom as reported by the Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre (ICNARC) (2). Both of these scores are surprisingly low considering the high mortality rates in patients with COVID-19–related critical illness; in the U.K. mortality rates reach 40% (2). We therefore felt it necessary to further investigate severity of illness scoring systems commonly used in critical care and their associations with patient outcomes in COVID-19.

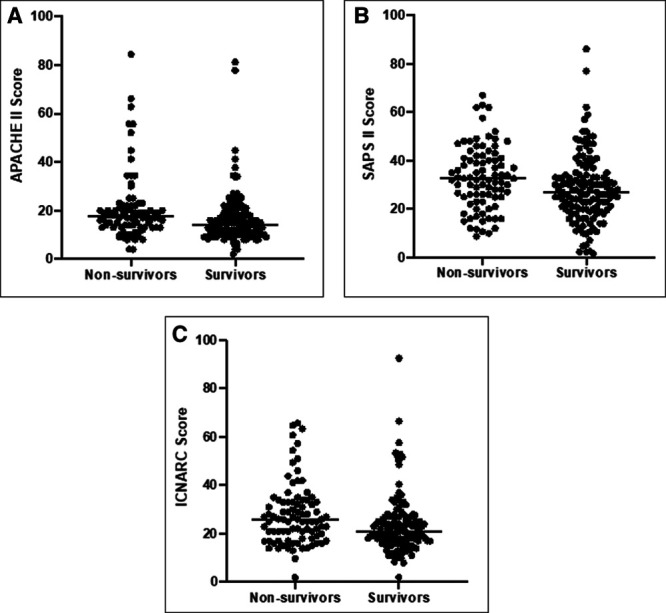

We performed a retrospective analysis of the APACHE II (2013), Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS) II, and ICNARC (2013) scores of all critically unwell patients with COVID-19 admitted to ICUs across three teaching hospitals in London from March 10, 2020, to May 22, 2020, paying particular interest to nonsurvivors to assess whether the index critical illness scores were indicative of disease severity. The results for our cohort of 242 patients are described in Table 1, including the severity of illness scores, demographic, and clinical data. We found that our patients also had relatively low median severity of illness scores (APACHE II 16.0, SAPS II 29, ICNARC 22.5), similar to Zou et al (1) and the ICNARC registry, despite an overall mortality of 37.6%. Furthermore, our results demonstrate that APACHE II, SAPS II, and ICNARC scores are also unusually low in nonsurvivors with COVID-19 (Fig. 1), and this is reflected in the modest predicted mortality calculated from these scores (Table 1). This contrasts with critically unwell patients suffering from acute kidney injury or sepsis, where ICU severity of illness scores are often considerably higher in those that do not survive (3).

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics for Study Cohort, Survivors, and Nonsurvivors

| Variables | All Patients | Survivors | Nonsurvivors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (%) | 242 | 151 (62.4) | 91 (37.6) |

| Age, yr, median (IQR) | 59 (51–65) | 56 (47–63) | 61 (57–67) |

| Males, n (% total patients) | 174 (71.9) | 105 (60.3) | 69 (39.7) |

| Females, n (% total patients) | 68 (28.1) | 46 (67.6) | 22 (32.4) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 27.6 (24.45–55.5) | 27.6 (24.7–32.7) | 27.34 (23.9–30.2) |

| ICU length of stay, d, median (IQR) | 14.0 (5.1–30.0) | 15.1 (4.9–34.7) | 12.0 (5.8–20.0) |

| Advanced respiratory support daysa, d, median (IQR) | 12.5 (4.0–25.0) | 12.0 (3.0–29.0) | 13.0 (6.0–19.0) |

| Advanced renal support daysb, d, median (IQR) | 0 (0.0–4.0) | 0 (0.0–6.0) | 0 (0.0–2.0) |

| APACHE II, median (IQR) | 16.0 (11.0–20.0) | 14.0 (10.0–19.0) | 17.5 (13.0–21.8) |

| Predicted mortality calculated from median APACHE II score, % | 23.5 | 18.6 | 29.1 |

| SAPS II, median (IQR) | 29 (21–38) | 27 (20–34) | 33 (25–41) |

| Predicted mortality calculated from median SAPS II score, % | 9.7 | 7.9 | 14.0 |

| Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre, median (IQR) | 22.5 (17.0–28.7) | 20.9 (17.0–27.0) | 26.0 (18.5–65.6) |

APACHE = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation, IQR = interquartile range, SAPS = Simplified Acute Physiology Score.

aAdvanced respiratory support: mechanical ventilatory support via endotracheal tube or extracorporeal respiratory support.

bAdvanced renal support: acute renal replacement therapy or provision of renal replacement therapy to a chronic renal failure patient who is requiring other acute organ support.

Figure 1.

Scatter plot showing severity of illness scores for survivors and nonsurvivors. A, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II; B, Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS) II; C, Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre (ICNARC) scores for study cohorts, survivors, and nonsurvivors. Median as indicated by horizontal line.

Zou et al (1) found that APACHE II scores significantly differed between survivors and nonsurvivors (10.87 ± 4.47 vs 23.23 ± 6.05, respectively; p < 0.001), concluding that it can be used to predict mortality in patients with COVID-19. However, we could not replicate these data, which is consistent with another study of critically ill patients in Wuhan, demonstrating mean APACHE II scores of 18 in patients that did not survive (4). It is worth considering that in the study by Zou et al (1), only 50% of patients were described as “critically unwell,” yet the APACHE II score is primarily validated for use in critically unwell patients. Furthermore, only 43% of patients received mechanical ventilation, which differs from the U.K. ICU population, where 69.4% (7,277/10,492) of COVID-19 patients required advanced respiratory support (2).

The APACHE II, SAPS II, and ICNARC critical care severity of illness scores are well validated and widely used across the world, quantifying disease severity, predicting mortality or prognosis, assessing ICU performance, and stratifying patients for clinical trials for non-COVID-19 patients. However, our data suggest that these scores in their current form may be unsuitable for these purposes in COVID-19 patients, grossly underestimating actual mortality risk and poorly stratifying disease severity. Since all three scores use data generated within the first 24 hours of ICU admission, it may therefore be postulated that in COVID-19, traditional markers of illness severity and biomarkers are not affected until later into the ICU stay, with patients initially presenting with respiratory compromise alone. Furthermore, neither scoring system considers the ethnicity of patients and it has been well documented that a disparity in outcome exists among different ethnicities with Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic groups being at higher risk of death compared with White ethnic groups (5). It may therefore be prudent to develop these ICU scoring systems specifically for COVID-19 to more reliably predict severity of illness and mortality.

To conclude, we suggest that the most commonly used ICU scoring systems in their current form grossly underestimate severity of illness and are not associated with mortality in critically unwell COVID-19 patients. We propose that further work is required to generate a COVID-19 specific severity of illness and mortality prediction model, which can better prepare healthcare services in this ongoing pandemic.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Maie Templeton, the Clinical Audit Team and the clinical staff at Hammersmith Hospital, St Mary’s Hospital, and Charing Cross Hospital for their assistance with collecting the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II, Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre, and Simplified Acute Physiology Score II data.

Footnotes

Drs. Stephens and Soni involved in study concept and design and drafting of article. Drs. Stümpfle, Patel, and Broomhead involved in data acquisition. Drs. Stephens, Brett, and Soni involved in data analysis and interpretation. Drs. Stümpfle, Patel, Brett, Broomhead, and Baharlo involved in critical revision and advice.

The authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

This service evaluation was registered locally with the Imperial College Ethics and Review board to enable access to the retrospective data used in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zou X, Li S, Fang M, et al. Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II Score As a Predictor of Hospital Mortality in Patients of Coronavirus Disease 2019. Crit Care Med. 2020; 48:e657–e665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre: ICNARC Report on COVID-19 in Critical Care 17 July 2020. 2020. Available at: https://www.icnarc.org/Our-Audit/Audits/Cmp/Reports. Accessed July 19, 2020

- 3.Gong Y, Ding F, Zhang F, et al. Investigate predictive capacity of in-hospital mortality of four severity score systems on critically ill patients with acute kidney injury. J Investig Med. 2019; 67:1103–1109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020; 8:475–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Public Health England: Disparities in the Risk and Outcomes of COVID-19. 2020. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/891116/disparities_review.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2020