Abstract

Objectives:

The deleterious health effects of long working hours have been previously investigated, but there is a dearth of studies on mortality resulting from accidents or suicide. This prospective study aims to examine the association between working hours and external-cause mortality (accidents and suicide) in Korea, a country with some of the longest working hours in the world.

Methods:

Employed workers (N=14 484) participating in the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) were matched with the Korea National Statistical Office’s death registry from 2007–2016 (person-years = 81 927.5 years, mean weighted follow-up duration = 5.7 years). Hazard ratios (HR) for accident (N=25) and suicide (N=27) mortality were estimated according to weekly working hours, with 35–44 hours per week as the reference.

Results:

Individuals working 45–52 hours per week had higher risk of total external cause mortality compared to those working 35–44 hours per week [HR 2.79, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.22–6.40], adjusting for sex, age, household income, education, occupation, and depressive symptoms. Among the external causes of death, suicide risk was higher (HR 3.89, 95% CI 1.06–14.29) for working 45–52 hours per week compared to working 35–44 hours per week. Working >52 hours per week also showed increased risk for suicide (HR 3.74, 95% CI 1.03–13.64). No statistically significant associations were found for accident mortality.

Conclusions:

Long working hours are associated with higher suicide mortality rates in Korea.

Keywords: depression, injury, karoshi, KNHANES, Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, mental health, occupational, overwork, work hour, working time, work time

Among the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, Korea ranked as one of the top nations for longest working hours between 2008 and 2018 (1). In 2018, the annual working hour average in Korea was 1993 hours, while the working hour average for the OECD countries collectively was 1734 hours per year (1). Previous studies have established an association between long working hours and adverse outcomes, including coronary heart disease (2), stroke (3), mental health disorders (4, 5), reproductive health problems (6), and accidents (7). As working hours in East Asian countries (Japan, Korea, and Taiwan) are generally longer than those of western countries, deaths related to overwork (called karoshi), usually from cardiovascular disease, represent a growing social concern (8). Recently, suicide among overworked employees has drawn urgent attention in both Japan and Korea (9, 10). However, studies on working hours and suicide are limited to descriptive case series (11, 12), with one notable exception of a longitudinal study in the UK (13). Although the mechanism linking long working hours and suicide is not yet fully understood, a number of studies have examined the association between long working hours and depressive symptoms or suicide ideation (4, 5, 14). The deleterious impact of long working hours on mental health status is an obvious pathway connecting long working hours and suicide.

Besides cardiovascular disease and suicide, accidents are another potentially fatal outcome associated with long working hours. Fatigue and sleep loss potentially mediate the association between long working hours and accidents both in and out of the workplace (15, 16). However, the majority of studies on working hours and accidents have remained cross-sectional and/or used self-reported accidents as the outcome (7). On the contrary, a recent prospective study using national registers to assess accidents concluded there was no association between long working hours and accidents (17).

Thus, although some previous studies support an adverse impact of long working hours on suicide and accident mortality, this association is not well established by longitudinal data. In addition, to our knowledge, the association between long working hours and suicide or accident-related deaths has not been previously reported in the East Asian context.

Accordingly, the aim of this prospective study was to investigate the relationship between long working hours and accident mortality/suicide in a Korean working population based on nationwide longitudinal data.

Methods

Study population

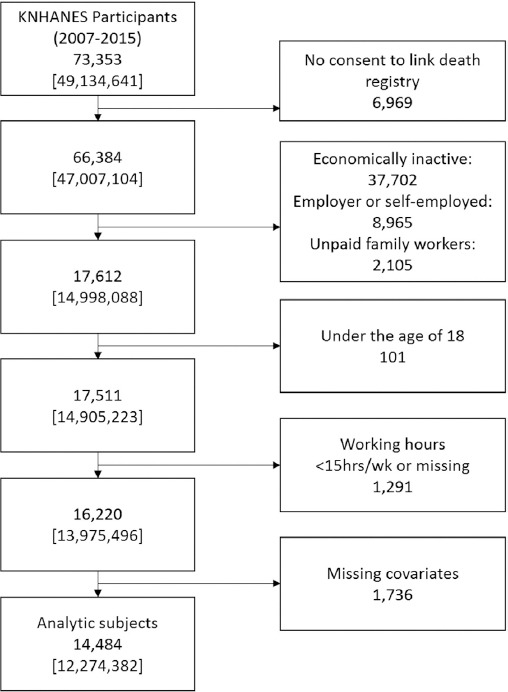

Our data were derived from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) conducted by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) between 2007–2015. These data were then matched with death registry data compiled by the Korea National Statistical Office (KNSO) from 2007–2016. The survey used a multi-stage, cluster-sampling design based on the National Census Registry; hence, statistical analyses of this survey were based on sample weights assigned to sample participants. Among the 73 353 participants in KNHANES, 66 384 participants provided consent to link their data to the death registry. We restricted the subjects to employed workers by excluding the economically inactive population (37 702), employers and self-employed workers (8965), and unpaid family workers (2105). Employers and self-employed workers were excluded due to their ability to control their working hours; despite their working hours being even longer than employed workers, they are not subject to working hour regulations (18). Additionally, we excluded the following individuals: those <18 years, individuals with <15 work hours per week or missing information on working hours, and covariates. After these exclusions, our analytic cohort comprised 14 484 men and women. The selection process of the study population is presented in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart illustrating the process of creating the cohort. Weighted frequencies showed in [ ]. [KNHANES=Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.]

Ascertainment of outcomes

The cohort dataset was matched with the death registry of the KNSO from 2007–2016 with the use of a unique identification number. As all deaths in Korea are reported to the KNSO by law, coverage of the death registry can be considered complete. Information on the specific cause of death according to the Korean Classification of Disease (KCD) and date of death was provided by KNSO. The KCD is compatible with the International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD-10). Deaths from total external cause (V01–Y98), subsets including accidents (V01–V99; transport accidents, and W00–X59; other external causes of accidental injury), and intentional self-harm (X60–X84) were used as our outcomes. During an average 5.2 person-years of follow-up, 56 participants died from total external causes. Among them, 25 individuals died from accidents (13 from transport accidents and 12 from the other accidents) and 27 died from suicide.

Assessment of working hours

Working hours were measured by responses to a question on the KNHANES asking: “How many hours do you usually work per week, including overtime?” Working hours were classified into four groups: (i) 15–34, (ii) 35–44, (iii) 45–52, and (iv) >52 hours per week. The top code of >52 hours per week was based on the maximum permitted working hours according to the Labor Standard Act in Korea (19). This Act has defined standard working hours as 40 hours per week, with extensions up to 52 hours per week permitted with the worker’s consent. However, working on weekends was not subject to regulation until 2018, therefore enabling workers to work >52 hours per week legally if they worked on a Saturday or Sunday.

Covariates

Age, sex, household income, education, occupation, and depressive symptoms were included in our regression models as possible confounders. Socioeconomic status (SES), including occupation, is associated with both accident and suicide mortality (20). Depressive symptoms are a well-established risk factor for suicide and could be related to accidents as well (21). These covariates were collected during interviews in the KNHANES.

Monthly household income was equalized for household size (gross monthly household income divided by the square root of household size) and participants were divided into four groups according to quartile of standardized household income by survey year. Occupation was coded into nine categories according to the Korean Standard Classification of Occupation (22), and we collapsed these into six groups (managers and professionals; office workers; service and sales workers; agricultural, forestry, and fishery workers; plant and machine operators and assemblers; and elementary occupations). The response to the question, “Have you experienced serious sadness or hopelessness that restricts your daily life continuously for >2 weeks in the last year?” was used to define depressive symptoms, with an affirmative response indicating a positive for depressive symptoms.

Statistical analysis

Cox proportional hazards models were developed to estimate hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the association between working hours and deaths from accidents and suicide. In the Cox models, person-days were calculated from the initial date of participation in the KNHANES until either the date of death (including deaths from non-accidental causes) or 31 December 2016, whichever occurred first. The analytic model included age, sex, education, occupation, household income, and depressive symptoms as covariates. We applied the integrated survey weights, calculated by averaging weights over sampled years, because we used data from multiple waves of the survey. The sampling weights for each wave of the survey was calculated and provided by the KCDC to ensure the survey data could be inflated to the population level from which the sample was derived. More KNHANES sampling weight details can be found elsewhere (23).

Ethical approval

The Institutional Review Board of the Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention reviewed and approved the pilot study of the KNHANES-linked cause of death data (IRB No. 2018-07-01-P-A).

Results

The distribution of working hours according to sample characteristics is presented in table 1. Of these participants, 35.6% worked 35–44 hours per week, 24.7% worked 45–52 hours per week, and 24.9% worked >52 hours per week. Working for >52 hours per week was prevalent among men (30.9%), those with middle lower household income (29.1%), those with middle school education (30.5%), and plant and machine operators and assemblers (39.1%).

Table 1.

Distribution of working hours by participants’ characteristics.

| Working hour (hours/week) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <35 | 35–44 | 45–52 | >52 | |||||||||

| Frequency | Weighted frequency | % | Frequency | Weighted frequency | % | Frequency | Weighted frequency | % | Frequency | Weighted frequency | % | |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 700 | 643 292 | 8.7 | 2560 | 2 407 664 | 32.4 | 2120 | 2 081 378 | 28.0 | 2417 | 2 300 438 | 30.9 |

| Female | 1658 | 1 176 870 | 24.3 | 2703 | 1 960 773 | 40.5 | 1280 | 951 084 | 19.6 | 1046 | 752 882 | 15.6 |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||

| <30 | 308 | 336 460 | 25.7 | 345 | 412 326 | 31.5 | 233 | 289 634 | 22.1 | 202 | 270 383 | 20.7 |

| 30–39 | 325 | 309 596 | 9.3 | 1235 | 1 224 546 | 36.7 | 892 | 955 240 | 28.6 | 742 | 848 280 | 25.4 |

| 40–49 | 496 | 380 507 | 11.1 | 1593 | 1 253 001 | 36.6 | 1102 | 916 887 | 26.7 | 1018 | 877 490 | 25.6 |

| 50–59 | 521 | 410 580 | 15.4 | 1272 | 1 010 361 | 37.9 | 741 | 606 713 | 22.8 | 762 | 635 506 | 23.9 |

| ≥60 | 708 | 383 019 | 24.9 | 818 | 468 204 | 30.5 | 432 | 263 989 | 17.2 | 739 | 421 662 | 27.4 |

| Household income | ||||||||||||

| Lowest | 441 | 306 118 | 31.9 | 333 | 259 144 | 27.0 | 203 | 158 863 | 16.6 | 292 | 234 535 | 24.5 |

| Middle lower | 696 | 560 595 | 18.0 | 1103 | 935 014 | 30.1 | 787 | 708 762 | 22.8 | 1056 | 906 891 | 29.1 |

| Middle higher | 677 | 541 500 | 13.0 | 1719 | 1 495 082 | 35.8 | 1153 | 1 070 957 | 25.6 | 1168 | 1 069 844 | 25.6 |

| Highest | 544 | 411 948 | 10.2 | 2108 | 1 679 197 | 41.7 | 1257 | 1 093 880 | 27.2 | 947 | 842 050 | 20.9 |

| Education | ||||||||||||

| Elementary school | 483 | 281 609 | 27.8 | 447 | 273 103 | 26.9 | 252 | 155 429 | 15.3 | 468 | 304 506 | 30.0 |

| Middle school | 292 | 220 770 | 22.0 | 370 | 282 408 | 28.2 | 245 | 192 832 | 19.3 | 392 | 305 364 | 30.5 |

| High school | 932 | 816 664 | 16.8 | 1835 | 1 604 593 | 33.0 | 1153 | 1 096 765 | 22.6 | 1407 | 1 339 308 | 27.6 |

| ≥College | 651 | 501 119 | 9.3 | 2611 | 2 208 333 | 40.9 | 1750 | 1 587 436 | 29.4 | 1196 | 1 104 142 | 20.4 |

| Occupation | ||||||||||||

| Managers, professionals | 499 | 396 325 | 13.3 | 1463 | 1 213 594 | 40.8 | 924 | 810 068 | 27.2 | 599 | 555 315 | 18.7 |

| Office workers | 191 | 162 675 | 6.2 | 1508 | 1 263 301 | 48.2 | 866 | 772 384 | 29.5 | 466 | 422 802 | 16.1 |

| Service & sales workers | 649 | 543 268 | 24.7 | 779 | 657 864 | 30.0 | 463 | 419 953 | 19.1 | 651 | 575 142 | 26.2 |

| Agricultural, forestry & fishery workers | 12 | 6113 | 10.3 | 28 | 20 729 | 35.0 | 16 | 14 544 | 24.5 | 21 | 17 921 | 30.2 |

| Plant & machine operators and assemblers | 208 | 179 670 | 7.2 | 710 | 661 038 | 26.5 | 696 | 676 172 | 27.1 | 985 | 974 518 | 39.1 |

| Elementary occupations | 799 | 532 111 | 27.6 | 775 | 551 912 | 28.6 | 435 | 339 341 | 17.6 | 741 | 507 622 | 26.3 |

| Depressive symptom | ||||||||||||

| No | 2013 | 1 564 971 | 14.2 | 4761 | 3 972 522 | 36.0 | 3099 | 2 780 318 | 25.2 | 3060 | 2 731 800 | 24.7 |

| Yes | 345 | 255 191 | 20.8 | 502 | 395 916 | 32.3 | 301 | 252 144 | 20.6 | 403 | 321 520 | 26.3 |

| Total | 2358 | 1 820 162 | 14.8 | 5263 | 4 368 438 | 35.6 | 3400 | 3 032 462 | 24.7 | 3463 | 3 053 320 | 24.9 |

The number of cases and participant mortality rates are shown in table 2. The accident mortality rates were 16.4, 21.1, 46.7, and 36.3 per 100 000 in the <35, 35–44, 45–52, and >52 hours/week groups, respectively. Suicide rates of 12.5, 12.0, 51.2, and 52.8 per 100 000 were observed in the <35, 35–44, 45–52, and >52 hours/week groups, respectively. The majority of deaths from accidents (24 cases) were among men; there was only one case among women. Suicide rates were also higher among men (46.8 per 100 000) than women (10.2 per 100 000).

Table 2.

Accident and suicide mortality rates by characteristics of study population.

| Person-years | Person-years (weighted) | Deaths (frequency) | Deaths (weighted frequency) | Mortality rate per 100 000 (weighted) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total external cause | Accidents | Suicide | Total external cause | Accidents | Suicide | Total external cause | Accidents | Suicide | |||

| Total | 81 927.5 | 66 991 485 | 56 | 25 | 27 | 44 285 | 20 529 | 21 665 | 66.5 | 30.8 | 32.5 |

| Weekly working hours | |||||||||||

| <35 | 12 532.6 | 9 269 924 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 2981 | 1507 | 1150 | 32.4 | 16.4 | 12.5 |

| 35–44 | 29 509.3 | 23 456 408 | 11 | 7 | 4 | 7699 | 4910 | 2790 | 33.0 | 21.1 | 12.0 |

| 45–52 | 19 389.3 | 16 801 464 | 19 | 7 | 11 | 17 491 | 7818 | 8567 | 104.6 | 46.7 | 51.2 |

| >52 | 20 496.3 | 17 463 689 | 20 | 8 | 10 | 16 114 | 6294 | 9158 | 93.0 | 36.3 | 52.8 |

| Sex | |||||||||||

| Male | 44 284.6 | 40 854 353 | 48 | 24 | 22 | 40 001 | 19 752 | 19 004 | 98.5 | 48.7 | 46.8 |

| Female | 37 642.8 | 26 137 132 | 8 | 1 | 5 | 4284 | 777 | 2660 | 16.5 | 3.0 | 10.2 |

| Age (years) | |||||||||||

| <30 | 4919.8 | 5 690 569 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 489 | 489 | 0 | 8.8 | 8.8 | 0.0 |

| 30-39 | 18 028.1 | 18 331 998 | 11 | 4 | 7 | 10 921 | 3780 | 7141 | 59.9 | 20.7 | 39.2 |

| 40-49 | 24 553.7 | 19 206 355 | 18 | 9 | 9 | 17 636 | 8854 | 8781 | 92.2 | 46.3 | 45.9 |

| 50-59 | 18 837.2 | 14 909 515 | 10 | 3 | 5 | 8799 | 3460 | 3709 | 59.2 | 23.3 | 25.0 |

| ≥60 | 15 588.7 | 8 853 048 | 16 | 8 | 6 | 6440 | 3946 | 2033 | 73.0 | 44.7 | 23.0 |

| Household income | |||||||||||

| Lowest | 7511.6 | 5 444 165 | 10 | 1 | 8 | 6426 | 777 | 5326 | 118.1 | 14.3 | 97.9 |

| Middle lower | 20 820.5 | 17 351 384 | 16 | 9 | 5 | 11 464 | 7103 | 3698 | 66.8 | 41.4 | 21.5 |

| Middle higher | 26 475.1 | 22 518 180 | 15 | 10 | 5 | 12 485 | 7978 | 4508 | 55.8 | 35.6 | 20.1 |

| Highest | 27 120.2 | 21 677 755 | 15 | 5 | 9 | 13 910 | 4671 | 8133 | 64.5 | 21.7 | 37.7 |

| Education | |||||||||||

| Elementary school | 9592.7 | 5 739 575 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 3195 | 989 | 1359 | 55.8 | 17.3 | 23.7 |

| Middle school | 7345.3 | 5 555 209 | 10 | 6 | 4 | 6575 | 4201 | 2375 | 120.2 | 76.8 | 43.4 |

| High school | 30 523.0 | 27 077 154 | 18 | 11 | 6 | 17 208 | 10 050 | 7020 | 64.0 | 37.4 | 26.1 |

| ≥College | 34 466.5 | 28 619 547 | 20 | 6 | 13 | 17 307 | 5290 | 10 911 | 60.8 | 18.6 | 38.3 |

| Occupation | |||||||||||

| Managers, professionals | 19 474.0 | 16 016 850 | 7 | 1 | 6 | 6365 | 848 | 5517 | 39.9 | 5.3 | 34.6 |

| Office workers | 16 922.9 | 14 027 171 | 9 | 3 | 5 | 7372 | 2058 | 4208 | 52.7 | 14.7 | 30.1 |

| Service & sales workers | 14 442.0 | 12 112 973 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 7279 | 4504 | 2775 | 60.7 | 37.6 | 23.2 |

| Agricultural, forestry & fishery workers | 453.0 | 320 893 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Plant & machine operators and assemblers | 14 965.3 | 13 869 286 | 14 | 10 | 4 | 10 627 | 7579 | 3047 | 77.1 | 55.0 | 22.1 |

| Elementary occupations | 15 670.4 | 10 644 311 | 20 | 7 | 10 | 12 643 | 5541 | 6117 | 119.8 | 52.5 | 57.9 |

| Depressive symptom | |||||||||||

| No | 72 817.6 | 60 113 630 | 50 | 22 | 25 | 39 674 | 18 424 | 19 682 | 66.4 | 30.8 | 33.0 |

| Yes | 9109.9 | 6 877 854 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 4612 | 2106 | 1982 | 67.4 | 30.8 | 29.0 |

Table 3 shows the results from the Cox regressions examining the association between working hours and mortality due to accidents and suicide. Proportional hazards assumptions were met. In the model adjusting for sex, age, household income, education, occupation, and depressive symptoms, participants working 45–52 hours/week showed elevated total external cause mortality risk (HR 2.79, 95% CI 1.22–6.40) compared to the reference group reporting 35–44 hours/ week. Men and women working >45 hours/week showed higher suicide mortality risk (45–52 hours: HR 3.89, 95% CI 1.06–14.29; >52 hours: HR 3.74, 95% CI 1.03–13.64) compared to the reference group. No statistically significant associations were found for accident mortality.

Table 3.

Accident and suicide mortality risk according to working hours. Cox proportional hazard model. [HR=hazard ratio; CI=confidence interval.]

| Working hours | Adjusted HR a | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total external cause | |||

| <35 | 0.94 | 0.29–3.04 | |

| 35–44 | Reference | ||

| 45–52 | 2.79 | 1.22–6.40 | |

| >52 | 2.04 | 0.88–4.72 | |

| Accidents | |||

| <35 | 0.82 | 0.22–3.14 | |

| 35–44 | Reference | ||

| 45–52 | 1.78 | 0.57–5.52 | |

| >52 | 0.98 | 0.32–2.98 | |

| Suicide | |||

| <35 | 0.95 | 0.11–8.39 | |

| 35–44 | Reference | ||

| 45–52 | 3.89 | 1.06–14.29 | |

| >52 | 3.74 | 1.03–13.64 |

Adjusted by age, sex, household income, education, occupation and depressive symptom.

Discussion

Total external causes

We found that individuals working 45–52 hours per week have a higher statistically significant risk of external cause mortality compared to those working 35–44 hours per week. Those working >52 hours showed a higher HR, but the result was not statistically significant. The risk of total external cause mortality is mainly driven by the excess risk of suicide because suicide showed a significantly elevated HR in the groups working 45–52 and >52 hours. On the contrary, those working >52 hours showed a lower risk of accidents compared to the standard working hour group. This opposite direction of association between accidents and suicide among the >52 hours group suggests that mortality from these causes might have different pathways.

Accidents

In previous studies (24, 25), an adverse impact of long working hours among hospital workers (including young doctors) on traffic accidents have been reported [odds ratio 2.3 for extended shift (>24 hours), 95% CI 1.6–3.3]. In one case-crossover study (16), there was a strong trend in increased rate ratios (RR) for traffic accidents and shift duration (RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.52–1.62 for >8 hours/day, RR 4.00, 95% CI 0.45–35.8 for >12 hours/day). For work-related accidents, several studies have also revealed the association between long working hours and increased self-reported or objectively confirmed work-related injury (26, 27). One case-crossover study showed that the risk for work-related injury in workers who worked >64 hours per week was 1.88 times greater than among those who worked ≤40 hours (28). A probable explanation for the association between long working hours and accidents is fatigue due to lack of sleep (24, 29).

The current study’s results were not consistent with these previous findings. The HR for accident mortality was lower among the >52 working hour group than the standard working hour group, although the differences were not statistically significant, and the CI was wide. A number of reasons could underlie this discrepancy. First, in the current study, there was a wide time gap between the assessment of working hours and accidents, while previous works measured working hours at the time of accidents (16, 24, 25). Sleep loss and fatigue can be more related to long working hours immediately preceding the accidents. Second, the outcome of the current study was mortality from accidents, while most previous studies used experiences of accidents as an outcome. As we used an extreme end of an accident outcome, the results could not be compared directly. In fact, a previous study using a similar design to ours (census-based longitudinal study in UK) found lower or similar risk of all accidental mortality for men working >55 compared to 35–40 hours/week among professional/managers, self-employed, and routine occupations (13).

Suicide

Although extensive research has been conducted on the association between long working hours and mental health (including depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation), very few studies have focused specifically on completed suicide. In Korea and Japan, where overwork-related suicide is a growing social concern, descriptive characteristics of suicide cases (compensated as work-related mortality) have been reported (11, 12). The daily working hours of 22 work-related suicide cases in Japan ranged from 10–16 hours (11). In a Korean report, “chronic long working hours” was the second most prevalent reason, following “acute stressful events”, for approved cases of compensable work-related mental disease, which included suicide (12). One UK-based longitudinal study examining the association of long working hours and completed suicide showed a 1.23–1.24 times higher risk in the >55 hour/week group compared to the 35–40 hour/week group among professionals/managers, but the results were not statistically significant (13).

Elevated risk of suicide might be due to the well-established association between long working hours and poor mental health (4, 5). However, suicide rate was not associated with depressive symptoms at our data baseline. This could be caused by the time gap between the survey and the events of suicide or depression. Indeed, a longitudinal study in the UK, which reported no depressive symptoms at baseline, showed a higher risk of incident depression among participants with long working hours after a 5-year follow-up (4).

A second explanation for the association between long working hours and suicide could be the deleterious effects these long hours have on relationships with family and friends. Social isolation and family conflict are widely reported risk factors for suicide (30), and long working hours have been shown to increase work–life conflict (31, 32).

According to a 2018 psychological autopsy report of the Korean Psychological Autopsy Center, among the 103 suicide cases, occupational stress was second only to mental health issues as a primary stressor. (33). In this report, qualitative analysis of 52 employed workers’ pathways to suicide revealed that their main occupational stressors included change of work, work demands, and relationships in the workplace (33). Long working hours are closely related to work demands, and work demands could affect the relationships between supervisors and coworkers.

Low SES is also a risk factor for suicide. A previous study in Korea revealed that suicide risk is 2.28 times higher in Medicaid recipients than in 10th-decile highest income individuals (34). In the current study, the lowest household income group showed markedly higher suicide rates (97.9 per 100 000) than other groups (20.1–37.7 per 100 000). Since working hours could be confounded by SES, we built analytic models adjusting for SES. However, we found that the association persisted in the adjusted model, suggesting that long working hours are associated with suicide risk, regardless of SES.

Strengths and limitations

The present study has significant strengths and limitations. Its strengths are that the subjects were drawn from a nationwide sample rather than from selected subgroups. Additionally, cause of death was determined from validated records. To our knowledge, this is the first study investigating the impact of long working hours on accident and suicide mortality in Korea.

Limitations of our study must be mentioned as well: the number of cases was relatively small; therefore, the CI for HR remained wide. Especially for women, accident mortality was extremely rare. Due to the small number of the cases, caution is warranted in generalizing the results of the current study. Working hours were measured based on self-report and collected only once at baseline. Since working hours are time-dependent variables, we cannot rule out the misclassification of exposure during follow-up. This possibility of non-differential working hour misclassification could have biased the results toward the null. Other time-varying covariates such as depressive symptoms could have changed during follow-up as well. However, due to the scarcity of repeated assessments of mental health status, we were unable to conduct a mediation analysis (ie, to check whether changes in depressive symptoms mediated the association between long working hours and suicide). Nevertheless, the lack of mediation analysis does not affect overall risk estimates of working hours for outcomes. Further analysis of working hour effects on mortality from accidents and suicide with a sufficient number of cases with longer follow-up periods, larger cohorts, and additional measures of working hours and covariates may follow in the future.

Concluding remarks

In conclusion, our study shows that workers who work long hours (>44 hours per week) have a higher risk of suicide in Korea.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the pilot study of the KNHANES-linked cause of death data, conducted by the KCDC, and the research fund of Hanyang University (HY-2015).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.OECD. Average annual hours actually worked. 2014. Available from: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/data/data-00303-en .

- 2.Virtanen M, Heikkila K, Jokela M, Ferrie JE, Batty GD, Vahtera J, et al. Long working hours and coronary heart disease:a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2012 Oct 1;176(7):586–96. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws139. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kws139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kivimaki M, Jokela M, Nyberg ST, Singh-Manoux A, Fransson EI, Alfredsson L, et al. Long working hours and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke:a systematic review and meta-analysis of published and unpublished data for 603,838 individuals. Lancet. 2015 Oct 31;386(10005):1739–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60295-1. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60295-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Virtanen M, Ferrie JE, Singh-Manoux A, Shipley MJ, Stansfeld SA, Marmot MG, et al. Long working hours and symptoms of anxiety and depression:a 5-year follow-up of the Whitehall II study. Psychol Med. 2011 Dec;41(12):2485–94. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711000171. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291711000171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim I, Kim H, Lim S, Lee M, Bahk J, June KJ, et al. Working hours and depressive symptomatology among full-time employees:Results from the fourth Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2007-2009) Scand J Work Env Health. 2013 Sep 1;39(5):515–20. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3356. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takeuchi M, Rahman M, Ishiguro A, Nomura K. Long working hours and pregnancy complications:women physicians survey in Japan. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:245. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-245. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-14-245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wagstaff AS, Sigstad Lie JA. Shift and night work and long working hours--a systematic review of safety implications. Scand J Work Env Health. 2011 May;37(3):173–85. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3146. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng Y, Park J, Kim Y, Kawakami N. The recognition of occupational diseases attributed to heavy workloads:experiences in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2012 Oct;85(7):791–9. doi: 10.1007/s00420-011-0722-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-011-0722-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takahashi M. Sociomedical problems of overwork-related deaths and disorders in Japan. J Occup Health. 2019 Jul;61(4):269–77. doi: 10.1002/1348-9585.12016. https://doi.org/10.1002/1348-9585.12016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim I, Koo MJ, Lee H-E, Won YL, Song J. Overwork-related disorders and recent improvement of national policy in South Korea. J Occup Health. 2019 Jul;61(4):288–96. doi: 10.1002/1348-9585.12060. https://doi.org/10.1002/1348-9585.12060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amagasa T, Nakayama T, Takahashi Y. Karojisatsu in Japan:characteristics of 22 cases of work-related suicide. J Occup Health. 2005 Mar;47(2):157–64. doi: 10.1539/joh.47.157. https://doi.org/10.1539/joh.47.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee J, Kim I, Roh S. Descriptive study of claims for occupational mental disorders or suicide. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2016;28:61. doi: 10.1186/s40557-016-0147-7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40557-016-0147-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Reilly D, Rosato M. Worked to death?A census-based longitudinal study of the relationship between the numbers of hours spent working and mortality risk. Int J Epidemiol. 2013 Dec;42(6):1820–30. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt211. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyt211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoon JH, Jung PK, Roh J, Seok H, Won JU. Relationship between Long Working Hours and Suicidal Thoughts:Nationwide Data from the 4th and 5th Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0129142. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129142. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0129142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dembe AE, Erickson JB, Delbos RG, Banks SM. The impact of overtime and long work hours on occupational injuries and illnesses:new evidence from the United States. Occup Env Med. 2005 Sep;62(9):588–97. doi: 10.1136/oem.2004.016667. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.2004.016667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valent F, Di Bartolomeo S, Marchetti R, Sbrojavacca R, Barbone F. A case-crossover study of sleep and work hours and the risk of road traffic accidents. Sleep. 2010 Mar;33(3):349–54. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.3.349. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/33.3.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larsen AD, Hannerz H, Møller SV, Dyreborg J, Bonde JP, Hansen J, et al. Night work, long work weeks, and risk of accidental injuries. A register-based study. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2017 Nov 1;43(6):578–86. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3668. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park J, Kwon OJ, Kim Y. Long Working Hours in Korea. Ind Health. 2012;50(5):458–62. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.ms1353. https://doi.org/10.2486/indhealth.MS1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Labor Standard Act [Internet] Sect. 2012 Feb 1;50 Available from: https://elaw.klri.re.kr/eng_service/lawView.do?hseq=25437&lang=ENG . [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee H-E, Kim H-R, Chung YK, Kang S-K, Kim E-A. Mortality rates by occupation in Korea:a nationwide, 13-year follow-up study. Occup Environ Med. 2016;73(5):329–35. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2015-103192. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2015-103192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laursen TM, Musliner KL, Benros ME, Vestergaard M, Munk-Olsen T. Mortality and life expectancy in persons with severe unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2016 Mar 15;193:203–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.tatistics Korea. The Korean Standard Classification of Occupations [Internet] Korean Standard Statistical Classification. [cited. 2020. Jan 3, Available from: http://kssc.kostat.go.kr/ksscNew_web/ekssc/main/main.do# .

- 23.Kim Y. The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES):current status and challenges. Epidemiol Health. 2014 Apr 30;36:e2014002. doi: 10.4178/epih/e2014002. https://doi.org/10.4178/epih/e2014002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barger LK, Cade BE, Ayas NT, Cronin JW, Rosner B, Speizer FE, et al. Extended work shifts and the risk of motor vehicle crashes among interns. N Engl J Med. 2005 Jan 13;352(2):125–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041401. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa041401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirkcaldy B, Trimpop R, Cooper C. Working hours, job stress, work satisfaction, and accident rates among medical practitioners and allied personnel. Int J Stress Manag. 1997 Apr 1;4(2):79–87. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dong X. Long workhours, work scheduling and work-related injuries among construction workers in the United States. Scand J Work Env Health. 2005 Oct;31(5):329–35. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.915. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lombardi DA, Folkard S, Willetts JL, Smith GS. Daily sleep, weekly working hours, and risk of work-related injury:US National Health Interview Survey (2004-2008) Chronobiol Int. 2010 Jul;27(5):1013–30. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2010.489466. https://doi.org/10.3109/07420528.2010.489466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vegso S, Cantley L, Slade M, Taiwo O, Sircar K, Rabinowitz P, et al. Extended work hours and risk of acute occupational injury:A case-crossover study of workers in manufacturing. Am J Ind Med. 2007 Aug;50(8):597–603. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20486. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.20486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Folkard S, Lombardi DA. Modeling the impact of the components of long work hours on injuries and “accidents. ”Am J Ind Med. 2006 Nov;49(11):953–63. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20307. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.20307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, Joiner TE. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol Rev. 2010 Apr;117(2):575–600. doi: 10.1037/a0018697. https://doi. org/10.1037/a0018697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eurofound. Sixth European Working Conditions Survey - Overview report (2017 update) [Internet] Publications Office of the European Union. 2017. Available from: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/sites/default/files/ef_publication/field_ef_document/ef1634en.pdf .

- 32.Karhula K, Puttonen S, Ropponen A, Koskinen A, Ojajärvi A, Kivimäki M, et al. Objective working hour characteristics and work-life conflict among hospital employees in the Finnish public sector study. Chronobiol Int. 2017;34(7):876–85. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2017.1329206. https://doi.org/10.1080/07420528.2017.1329206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Korean psychological autopsy center. 2018 psychological autopsy report [Internet] Seoul: 2019. Aug, [cited 2019 Oct 23] Available from: http://www.psyauto.or.kr/sub/notice_view.asp?mode=&page=1&direction=&idx=&bbsid=biNotice&editIdx=730&SearchKey=ALL&SearchStr= [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee S-U, Oh I-H, Jeon HJ, Roh S. Suicide rates across income levels:Retrospective cohort data on 1 million participants collected between 2003 and 2013 in South Korea. J Epidemiol. 2017 Jun;27(6):258–64. doi: 10.1016/j.je.2016.06.008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.je.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]