To the Editor:

We read with great interest the comments addressed by Radermacher et al. (1) on our publication regarding the importance of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) for the prognosis and outcome of severe infection caused by the novel SARS-CoV-2 (also known as Covid-19) (2). Although serum H2S levels as high as 249 μM and 580 μM have been demonstrated in patients with septic shock (3) and severe asthma (4), we agree that the elevated serum H2S is an intriguing finding. We tried to deliver some answers that are based on: the performance of the used assay in healthy volunteers and in patients with other types of severe lung infection; and the reproducibility of the data by using another assay.

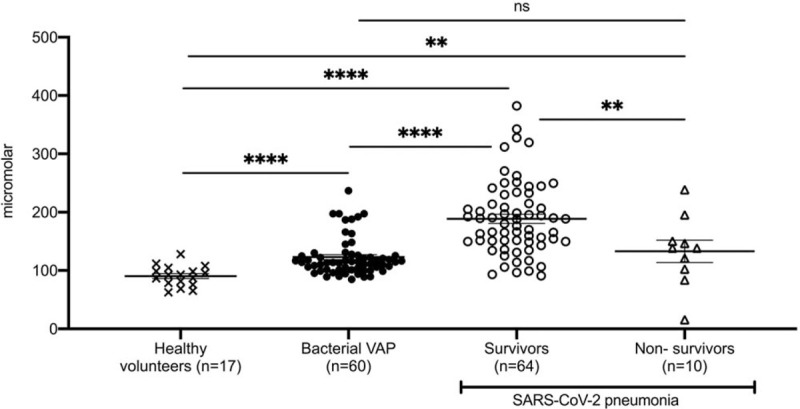

We measured levels of H2S in 17 healthy volunteers and in 60 patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP). VAP was diagnosed according to standard definitions (5) and all patients had microbiological confirmation with one Gram-negative pathogen isolated in counts greater than 105 colony-forming units/mL from the bronchoalveolar lavage by the culture technique already described (6). Isolated pathogens were Acinetobacter baumannii (n = 23), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n = 19), and Klebsiella pneumoniae (n = 18). Blood samples were collected within the first 24 h from diagnosis of VAP and H2S was measured by the monobromobimane derivatization assay followed by reverse phase HPLC separation (2). Results clearly showed that survivors from Covid-19 had H2S levels significantly greater than healthy population and patients with VAP (Fig. 1). This elaborates the hypothesis that it is not the assay that leads to false-positive increased H2S levels, but that H2S increase may well be an intrinsic characteristic of Covid-19 described for the first time herein. H2S of healthy was also within reported ranges (7).

Fig. 1.

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) levels in serum of (A) healthy volunteers; (B) patients with ventilator associated pneumonia (VAP) by P aeruginosa; K pneumoniae; A baumannii; and (C) patients with pneumonia by the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus on day 1 after hospital admission measured by monobromobimane derivatization assay followed by reverse phase HPLC separation. Comparison by the Mann–Whitney U test; ns indicates non-significant, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

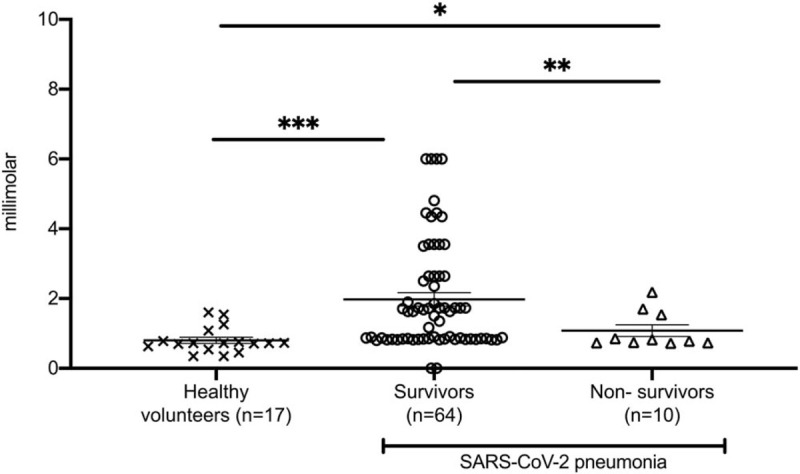

To strengthen the finding of increased H2S in Covid-19 survivors, H2S was measured in the same samples by a photometric methylene blue assay (8). Despite the lack of specificity of this assay leading to higher measurable levels, the interpretation of the findings was the same (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) levels in serum of (A) healthy volunteers; (B) survivors; and (C) non-survivors of pneumonia by the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus on day 1 after hospital admission measured by a photometric methylene blue assay. Comparison by the Mann–Whitney U test; ns indicates non-significant, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

We feel that Covid-19 is a new territory of research where modulation of H2S plays a major role and we wish to thank Rademacher et al. (1) for paving us the way to strengthen our data.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Calzia E, McCook O, Wachter U, Radermacher P, Csaba S. Letter to the Editor. Shock 2020; Epub Ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Renieris G, Katrini K, Damoulari C, Akinosoglou K, Psarrakis C, Kyriakopoulou M, Dimopoulos G, Lada M, Koufargyris P, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ. Serum hydrogen sulfide and outcome association in pneumonia by the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus. Shock 2020; doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saito J, Zhang Q, Hui C, Macedo P, Gibeon D, Menzies-Gow A, Bhavsar PK, Chung KF. Sputum hydrogen sulfide as a novel biomarker of obstructive neutrophilic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013; 131 (1): 232–234.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li L, Bhatia M, Zhu YZ, Zhu YC, Ramnath RD, Wang ZJ, Anuar FBM, Whiteman M, Salto-Tellez M, Moore PK. Hydrogen sulfide is a novel mediator of lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in the mouse. FASEB J 19 (9):1196–1198, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calandra T, Cohen J. The International Sepsis Forum Consensus Conference on definitions of infection in the intensive care unit: critical care medicine 33 (7):1538–1548, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baselski V, Baselski V, Klutts JS, Klutts JS. Point-counterpoint: quantitative cultures of bronchoscopically obtained specimens should be performed for optimal management of ventilator-associated. J Clin Microbiol 51 (3):740–744, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karunya R, Jayaprakash KS, Gaikwad R, Sajeesh P, Ramshad K, Muraleedharan KM, Dixit M, Thangaraj PR, Sen AK. Rapid measurement of hydrogen sulphide in human blood plasma using a microfluidic method. Sci Rep 9 (1):3258, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ang AD, Rivers-Auty J, Hegde A, Ishii I, Bhatia M. The effect of CSE gene deletion in caerulein-induced acute pancreatitis in the mouse. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 305 (10):G712–G721, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]