Conspectus.

The functionalization of unactivated carbon–hydrogen (C–H) bonds is a transformative strategy for the rapid construction of molecular complexity given the ubiquitous presence of C–H bonds in organic molecules. It represents a powerful tool for accelerating the synthesis of natural products and bioactive compounds while reducing the environmental and economic costs of synthesis. At the same time, the ubiquity and strength of C–H bonds also present major challenges towards the realization of transformations which are both highly selective and efficient. The development of practical C–H functionalization reactions has thus remained a compelling yet elusive goal in organic chemistry for over a century.

Specifically, the capability to form useful new C–C, C–N, C–O, and C–X bonds via direct C–H functionalization would have wide-ranging impacts in organic synthesis. Palladium (Pd) is especially attractive as a catalyst for such C–H functionalizations owing to the diverse reactivity of intermediate palladium–carbon bonds. Early efforts using cyclopalladation with Pd(OAc)2 and related salts led to the development of many Pd-catalyzed C–H functionalization reactions. However, Pd(OAc)2 and other simple Pd salts only perform racemic transformations, which prompted a long search for effective chiral catalysts dating back to the 1970s. Pd salts also have low reactivity with synthetically useful substrates. To address these issues, effective and reliable ligands capable of accelerating and improving the selectivity of Pd-catalyzed C–H functionalizations are needed.

In this Account, we highlight the discovery and development of bifunctional mono-N-protected amino acid (MPAA) ligands, which make great strides towards addressing these two challenges. MPAAs enable numerous Pd(II)-catalyzed C(sp2)–H and C(sp3)–H functionalization reactions of synthetically relevant substrates under operationally practical conditions and with excellent stereoselectivity when applicable. Mechanistic studies indicate that MPAAs operate as a unique bifunctional ligand for C–H activation in which both the carboxylate and amide are coordinated to Pd. The N-acyl group plays an active role in the C–H cleavage step, greatly accelerating C–H activation. The rigid MPAA chelation also results in a predictable transfer of chiral information from a single chiral center on the ligand to the substrate and permits the development of a rational stereomodel to predict the stereochemical outcome of enantioselective reactions.

We also describe the application of MPAA-enabled C–H functionalization in total synthesis and provide an outlook for future development in this area. We anticipate that MPAAs and related next generation ligands will continue to stimulate development in the field of Pd-catalyzed C–H functionalization.

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

While transition metal-catalyzed carbon–hydrogen (C–H) bond functionalization has received a great deal of attention during the past few decades,1 developing effective strategies to transform the C–H bonds of complex substrates into useful functional groups (such as hydroxyl, amino, halide, and aryl or alkyl groups) remains a great challenge in catalysis.1f Palladium (Pd), among many transition metals, has proven to be versatile in C–H functionalization.2 However, core challenges remain, namely the activation of C–H bonds of synthetically useful substrates (i.e. the use of native functional groups or common protecting groups as directing groups), achieving high site selectivity, and most important, achieving enantioselectivity. Effective ligands capable of accelerating C–H cleavage3 and improving the selectivity of Pd-catalyzed C–H functionalization reactions could greatly facilitate the achievement of the aforementioned objectives.4

Ligands can play a major role in C–H functionalizations by modulating both the C–H bond cleavage (C–H activation) and C–C/C–heteroatom bond formation steps. Their coordination with palladium can change the reactivity and structure of the metal, and consequently lower the activation energy of elementary steps. By energetically favoring the pathways that lead to a desired product, ligands can improve the Pd catalyst’s site selectivity and stereoselectivity.5 Ligands also can improve the solubility of palladium catalysts in organic solvents and stabilize the catalyst, increasing the concentration of the active species throughout the reaction.

Mono-N-protected amino acids (MPAAs) as bidentate ligands for Pd-catalyzed C–H functionalizations were first introduced by our laboratory in 2008 (Figure 1).6 Mechanistic studies (vide infra) have indicated that the MPAA ligands bind to Pd(II) in a bidentate manner and actively participate in C–H cleavage,7 in contrast to most known ligands, which modulate a metal’s properties but do not participate in catalytic steps. One notable exception is the diamine ligand in Noyori’s asymmetric transfer hydrogenation, in which the ligand nitrogen both heterolytically cleaves H2 and transfers a hydrogen atom to the carbonyl oxygen.8 Milstein has also reported metal-ligand cooperation with pincer complexes.9 The concept of cooperative ligand-metal C–H bond activation, as exemplified by MPAAs, has become an important design concept in C–H functionalization catalysis.4

Figure 1.

General structures of MPAA ligand, binding mode, and involvement in C–H activation.

This account will focus on our development of MPAA ligands for a diversity of C–H functionalization reactions. First, we will review the pertinent historical background of stoichiometric cyclopalladations and mechanistic studies of Pd-mediated C–H cleavage with external carboxylates. Second, we will summarize the discovery of bifunctional MPAA ligands for catalytic Pd C–H functionalizations and our hypotheses on how MPAAs influence the mechanism of C–H activation. Third, we will present a review of recent literature reports on Pd(II)-catalyzed C(sp2)–H and C(sp3)–H functionalization with MPAA ligands and applications in total synthesis. Finally, we will cover the future outlook for ligand design and reaction development.

2. Historical background of chiral carboxylate chemistry

The critical elementary step of most Pd-catalyzed C–H functionalizations is the Pd-mediated cleavage of the substrate’s C–H bond and concurrent formation of a Pd–C bond. Early studies of such capabilities in transition metals, often used coordinating groups to anchor the substrate and promote C–H cleavage to form a metallocycle, a process termed cyclometallation.10 Cope’s groundbreaking studies in the mid-1960s established the ability of Pd(II) to undergo cyclometallation with a variety of compounds, including azobenzenes11 and benzylamines.12

The capability of substrates to undergo cyclopalladation showed an intriguing dependence on the nature of the palladium source – specifically the counteranion to Pd. The attempted cyclopalladation of (dimethylamino)methylferrocene with K2PdCl4 only resulted in amine ligation.13 Shaw found in 1974 that the addition of an equivalent of sodium acetate relative to Pd generates the desired cyclometallated product (Scheme 1a),14 an effect seen in his studies with other cyclometallations.15 Basic conditions (NaOH) without acetate resulted in only partial cyclopalladation, indicating that acetate was not merely neutralizing HCl.16 Notably, the acetate conditions were later applied by Shaw to achieve one of the earliest examples of C(sp3)–H cyclopalladation, using oxime substrates (Scheme 1b).17

Scheme 1.

Acetate anion-enabled cyclopalladation of (dimethylamino)methylferrocene.

The unique cyclopalladation reactivity enabled by acetate indicated that the anion could be playing a role in C–H cleavage. The predominant mechanistic hypothesis for cyclopalladation, proposed in Cope’s seminal studies12 and termed electrophilic palladation, involved the attack of an electron rich π-system at an electrophilic Pd center followed by deprotonation (Figure 2a). The extraordinary acetate anion effect prompted Sokolov to propose an alternate mechanism with the carboxylate deprotonating the C–H bond concurrently with Pd–C bond formation in a cyclic six-membered transition state (Figure 2b).16

Figure 2.

Mechanistic hypotheses for cyclopalladation C–H cleavage.

This prescient hypothesis was studied and elaborated by others. Based on Hammett studies and electronic trends favoring electron-rich dimethylbenzylamines, Ryabov proposed in 1985 the acetate mechanism proceeded via π-attack at an electrophile as in electrophilic palladation. However, the Hammett plot slope of −1.6 is considerably smaller than most electrophilic aromatic substitutions. A large negative entropy of activation did indicate a tightly ordered six-membered transition state involving simultaneous palladation and deprotonation by the carboxylate.18 In contrast, when using Pd(OAc)2 for the cyclopalladation of benzylimines, Martinez observed in 1997 almost no rate dependence on substrate electronics, inconsistent with electrophilic attack, and large negative entropy values.19 Notably, Shaw’s reported C(sp3)–H cyclopalladation of oximes offers the most convincing evidence in favor of concerted internal deprotonation instead of electrophilic attack, which cannot occur with C(sp3)–H bonds.17

Davies and MacGregor performed computational studies on the Ryabov system in 2005,20 which explained the electronic effect as the consequence of electrophilic formation of an agnostic complex followed by a virtually barrierless deprotonation-metalation via a six-membered transition state. The C–H cleavage step itself was found to have minimal charge buildup.20 In 2006, Fagnou21 and Echavarren22 postulated closely related mechanisms for the carboxylate-mediated Pd C–H activation of arenes. Fagnou termed the mechanism “concerted metalation-deprotonation” (CMD) for Pd(0)-catalyzed C–H cleavage,23 the now accepted nomenclature for the ordered, cyclic six-membered transition state involving carbon–metal bond formation with simultaneous deprotonation of the C–H bond by an internal base. The electronic nature of this mechanism24 ranges from partial Pd electrophilic attack to C–H deprotonation of a neutral or electron-deficient substrate with little charge buildup. Substrate identity, ligands on Pd, and the nature of the base likely all influence the mechanism electronics. However, the CMD mechanism is overall much less sensitive to Pd electronics compared to electrophilic palladation and thus permits the use of donating ligands to stabilize the catalyst and modulate its reactivity.4, 23–24

Contemporaneously with Shaw’s acetate studies, Sokolov initiated studies of the stereoselectivity of cyclopalladation. Treating a (dimethylamino)methylferrocene bearing a chiral center α to the amine with Na2PdCl4 and sodium acetate induced diasteroselective C–H cleavage (85:15 d.r.) to generate planar chirality on the ferrocene ring (Scheme 2).25

Scheme 2.

Diastereoselective cyclopalladation controlled by substrate chirality.

Sokolov reasoned that if the (now termed) CMD mechanism was operative in the acetate-mediated cyclopalladation reaction of (dimethylamino)methylferrocenes, then replacing acetate with chiral carboxylates could facilitate an asymmetric cyclopalladation.16 Initial evaluations of chiral sodium carboxylates found that N-acyl-α-amino acids provided higher asymmetric induction than α-hydroxy acids, but overall enantioselectivity was low. Further experiments showed that the pH of the reaction was critical. When using a 1:1 mixture of (S)-Ac-Val-OH and NaOH as the carboxylate source and a lower pH (~5.5 prior to carboxylate addition), minimal enantioselectivity (8.0% ee) was observed, but a higher pH (6.7) resulted in much higher yields (89%) and enantioselectivity (65.0% ee) (Scheme 3a). The enantioenriched palladacycles could undergo subsequent reaction with CO or methyl vinyl ketone to generate functionalized products with minimal erosion in enantioselectivity (Scheme 3b).

Scheme 3.

Asymmetric stoichiometric cyclopalladation with (S)-Ac-Val-OH as a chiral carboxylate.

Sokolov’s innovative early studies indicated that N-acyl-α-amino acids as chiral carboxylates could control the stereochemical outcome of stoichiometric cyclopalladations. However, the possibility of the amide nitrogen coordinating and actively participating in the C–H cleavage step was not considered. Similarly, Moiseev would later apply chiral aliphatic carboxylates to achieve an allylic selective C–H palladation of cyclohexenes.26 Critically, enantioselective C–H activation under catalytic conditions to construct a new chiral center had yet to be demonstrated.

3. Discovery, early developments, and establishment of MPAAs as bifunctional ligands

3.1. Discovery and early development of MPAA ligands

At the initiation of our research program in 2002, Pd-catalyzed asymmetric C(sp3)–H functionalization was an unsolved challenge. We first targeted diastereoselective C–H activation using chiral auxiliary directing groups to gain insight into the stereochemistry of metalation. Diastereoselective C–H cleavage, achieved via the steric hindrance from the auxiliary,27 generates a chiral center bound to Pd, which subsequently reacts with various coupling partners to yield diverse products. We utilized an oxazoline auxiliary to achieve the first Pd(II)-catalyzed diastereoselective C(sp3)–H iodination and acetoxylation reactions (Scheme 4).27–28 Tert-leucine derived oxazoline 7 yielded, under mild conditions, iodinated 8 and acetoxylated 9 with moderate to excellent levels of diastereoselectivity (up to 82% de).

Scheme 4.

Diastereoselective C(sp3)–H functionalization using a chiral oxazoline auxiliary.

We next questioned whether stereoselectivity could be achieved using catalyst control instead of chiral auxilaries.6 Using prochiral compound diphenyl-2-pyridylmethane 10 as a model substrate for enantioselective C–H functionalization, we first developed an efficient racemic C(sp2)–H cross-coupling reaction with butylboronic acid. We then used this system to test strategies for asymmetric induction. Our initial hypothesis, based on the premise that the racemic C–H activation was proceeding via CMD involving an achiral acetate internal base, was that enantioselective C–H activation could be achieved by replacing the acetates with chiral carboxylates on the Pd(II) center. After evaluating many commercially available chiral carboxylates and chiral phosphates, MPAA ligands were found to give the highest enantioselectivity. Extensive tuning of the amino acid backbone structure and the N-protecting group revealed ligand L2 ((–)-Men-Leu-OH) as optimal, providing product 11 in excellent yield and enantioselectivity (Scheme 5). Notably, unprotected or bis-N-protected amino acids, or carboxylate esters provided minimal enantioselectivity, signifying, for the first time, that both the N-acyl N–H group and the carboxylate were playing critical roles in the C–H activation step.

Scheme 5.

Enantioselective C(sp2)–H activation/cross coupling enabled by a MPAA ligand.

We also tested MPAAs for the asymmetric C(sp3)–H cross-coupling of compound 12 containing gem-dimethyl groups using cyclopropyl ligand L3 (Scheme 6).6 Under these conditions, product 13 was obtained in 38% yield and 37% ee. While the modest enantioselectivity and reactivity likely arises from the more challenging nature of C(sp3)–H vs. C(sp2)–H activation, this result was a promising proof of concept that the MPAA ligand can effectively promote stereoinduction in both C(sp2)–H and C(sp3)–H functionalizations.

Scheme 6.

Enantioselective C(sp3)–H activation/cross coupling enabled by a MPAA ligand.

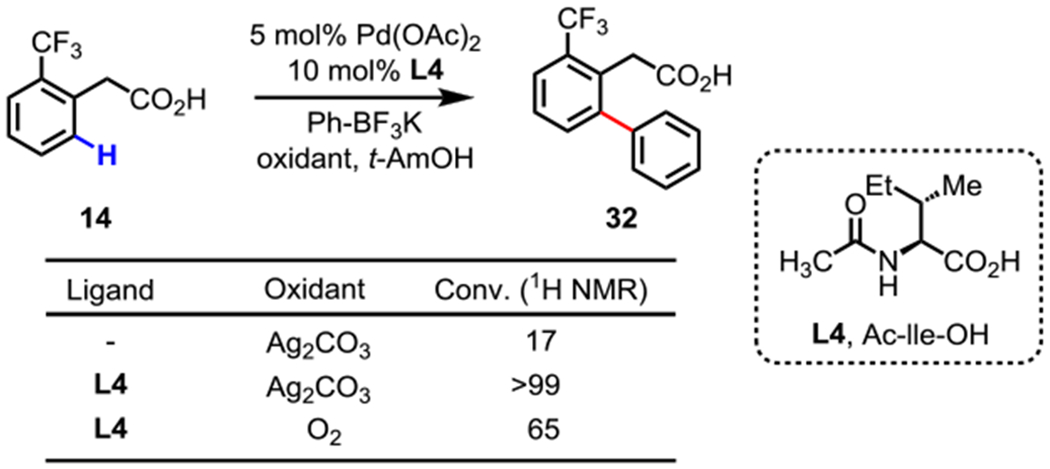

The effectiveness of MPAAs in enantioselective C–H functionalizations indicated that the ligand was playing a major role in the C–H activation step. This prompted our group to examine the potential of MPAAs to also to enable catalytic C–H functionalizations that were previously difficult or impossible. Specifically, we surmised MPAA ligands could promote the C–H olefination reactivity of unreactive electron-deficient phenylacetic acids. While only 7% conversion of 2–CF3 substituted 14 was observed without ligand, in the presence of acetyl-protected L4 72% conversion to 16 was observed in 20 minutes and >99% conversion after 2 h (Scheme 7a).29 The remarkable MPAA ligand effect was also observed with many other unreactive substrates, including 2-NO2, 3-CF3, 4-CF3, 2,5-difluoro, and 3-COPh phenylacetic acids.29–30

Scheme 7.

MPAA-enabled C–H olefination and reversal of reactivity in competition experiment.

The extraordinary boost in rate, selectivity, and reactivity afforded by MPAA ligands prompted us to investigate how they were altering and accelerating the C–H cleavage step.29 For the sake of completeness, subsequent studies that have refined our mechanistic understanding of MPAA ligands will also be discussed. A one-pot intermolecular competition experiment (Scheme 7b) revealed that 14 reacted faster than 15 with L4, (k14/k15 = 1.87), in sharp contrast to Pd(OAc)2 only (k14/k15 = 0.22). The striking inversion of electronic effects on reaction rate indicates that C–H activation using MPAA 14 is likely proceeding through a distinct mechanism from the electrophilic pathway operative with acetate.

3.2. Mechanistic studies reveal bifunctional MPAA involvement and ligand acceleration

As discussed above, our earliest hypothesis for MPAAs was as chiral carboxylates in the monodentate CMD mechanism (Figure 3a), similar to Sokolov’s stoichiometric asymmetric cyclopalladation studies. Others, including Richards,31 have continued to advance the chiral carboxylate proposal. Lewis has hypothesized that MPAAs can serve as bridging carboxylates not actively involved in C–H activation.32 While such mechanisms could be operative in certain cases, many of our observations in catalyst development and mechanistic studies are inconsistent with these proposals, especially for the synthetically relevant reactions developed in our group.

Figure 3.

Initial mechanistic hypotheses for C–H cleavage with MPAA ligands.

The free N-H bond of the N-acyl group has been critical to achieving desired stereoselectivity or reactivity in both the above reactions.6, 29–30 Alkylating or bisprotecting the nitrogen eliminates the activity of the amino acid ligands – an effect observed in many MPAA promoted reactions. Furthermore, a subtle steric and electronic balance at the N-acyl group itself is necessary for reactivity, since the electron-deficient trifloroacetyl group, excessively bulky N-acyl groups, or non-acyl protecting groups (benzyl) are all ineffective. All these observations argue against the MPAAs serving as simple carboxylates.

Our group then hypothesized whether the MPAA ligands were binding to Pd in a bidentate N,O fashion but with the C–H deprotonation performed by an external base (acetate) (Figure 3b). If the nitrogen bound to Pd were neutral (protonated),6 then it would follow that the N–H bond, acidified by Pd binding, would be preferentially deprotonated over the C–H bond. Thus a mechanism involving N–H deprotonation (activation) to yield anionic X–type nitrogen prior to acetate CMD was considered computationally in collaboration with Musaev in 2012.33 However, this mechanism would generate an anionic Pd after C–H cleavage and would not fully account for the steric and electronic sensitivity of the reaction to the N-acyl group. Any electron-deficient protecting group on nitrogen should be beneficial, but this is inconsistent with our experience in MPAA ligand development.

Musaev’s 2012 computational studies did elucidate a bidentate MPAA coordination mode, which was consistent with our experimental observations.33 In collaboration with the Wu and Houk laboratories in 2014, we proposed a new bidentate mechanism for MPAA C–H activation in which the N-acyl group participates as the internal base in the CMD (Figure 4).34 Mass spectrometry studies showed that MPAAs broke up trimeric [Pd(OAc)2]3 to yield monomeric [Pd(MPAA)(Solvent)2], the first experimental observation of such species. Computational studies showed the dianionic MPAA stabilizes a monomeric Pd pathway compared to acetate ligands. The internal amidate mechanism arising from the 1:1 Pd(MPAA) complex was found to be significantly favored (4 kcal/mol vs. closest alternative) over the external acetate or Pd(OAc)2 only pathways. The greater basicity of the amidate compared to acetate and the smaller net steric size of the MPAA relative to two acetates are proposed to be the primary factors for the energy difference. Furthermore, this model accounts for the reaction’s sensitivity to a subtle combination of N-acyl electronics and sterics,35 such as the greater reactivity of N-acetyl over Boc.

Figure 4.

Monomeric Pd promoted by MPAA binding and internal amidate MPAA mechanism.

With the internal amidate mechanism serving as our current model for MPAA ligand effects, there are several critical features of MPAA ligands that influence C–H activation (Figure 5): (1) the N-acyl group deprotonates the C–H bond; (2) R1 provides the subtle electronic and steric balance needed for appropriate N-acyl basicity, for facilitating N–H deprotonation and bidentate X,X binding, and for relay of stereochemistry; (3) R2 serves as the source of chirality and affects bite angle; (4) the bidentate MPAA promotes the formation of monomeric Pd(MPAA) catalysis. The relevance of these features are exemplified in catalytic transformations developed using MPAAs (vida infra).

Figure 5.

Important structural features of MPAA ligands.

3.3. Stereomodel for enantioselective C–H activation based on bidentate MPAA binding

The bidentate MPAA amidate mechanism also laid the foundation for the rational design of chiral ligands and enantioselective transformations.5 The chelating ligand creates a rigid framework ideal for the predictable transfer of chiral information to the substrate during C–H activation (Figure 6), in contrast to monodentate chiral carboxylates. Minimization of steric interactions between N–acyl substituent R1 and backbone group R2 serves to relay the stereochemistry and is a critical component of enantioinduction.36 Steric repulsion between the substrate and the ligand helps to differentiate the two diastereomeric transition states. Interactions with the directing group can also favor a particular enantiomer of product. Careful consideration of all interactions in the stereomodel can allow for accurate prediction of product stereochemistry.

Figure 6.

Stereomodel for bidentate internal amidate MPAA enantioselective C–H activation.

A specific model for the enantioselective C–H cross-coupling depicted in Scheme 5 can be developed from the general stereomodel. During our studies, we observed that the stereocenter α to the N-protected amino group was the primary factor in controlling the stereochemical course of the reaction. Two diastereomeric cyclopropane MPAAs with (S)- conformation of the α-stereocenter would deliver the same enantiomer of product with similar enantioselectivity, regardless of the other stereocenter’s configuration (Figure 7). The bifunctional stereomodel accurately accounts for the insensitivity of the reaction to the other chiral center. The primary interaction favoring the major enantiomer is the repulsion between the axial group of the substrate with the axial component of the ligand, the direction of which is determined by the α-stereocenter.

Figure 7.

Stereomodel for enantioselective C–H activation with MPAAs.

Prevailing design principles for bidentate chiral ligands utilize C2-symmetric scaffolds to limit possible faces of substrate approach.37 Surprisingly, C2-symmetric cyclopropane MPAA ligands were completely ineffective at asymmetric induction. Our bidentate stereomodel accurately explains why C2-symmetry is detrimental for MPAAs (Figure 8). The transition states leading to both enantiomers have equivalent and highly repulsive interactions between the ligand and substrate groups, so neither enantiomer is favored. Notably, C2-symmetry should not be problematic for chiral carboxylates, as evidenced by the success of analogous C2-symmetric phosphates38 – this further indicates that MPAAs are not serving as simple carboxylates.

Figure 8.

Rationale for the absence of enantioinduction with C2-symmetric MPAA ligands.

The concept of a bifunctional ligand with active N-acyl participation in C–H activation inspired us to develop next generation ligands (vide supra). In this scenario, ligands with two chiral centers on the backbone are possible. A rationale similar to Figure 8 can be applied to illustrate why pseudo C2-symmetry is undesirable for these ligands (Figure 9). The second large substituent on the ligand will create a strong steric repulsion with the directing group and render substrate approach from either face of the catalyst unfavorable. Such issues are not present when only one bulky substituent is on the backbone.

Figure 9.

Potential issues with pseudo C2-symmetric ligands.

4. Pd(II)-catalyzed C(sp2)–H functionalization promoted by MPAA ligands

Since our early studies with MPAAs, this ligand class has been applied by our group and others to enable challenging Pd-catalyzed C–H functionalizations and control enantioselectivity and site selectivity with a wide variety of different substrates. In addition to cross-coupling and arylation reactions, other developed C–H functionalizations include olefination, alkylation, iodination, and oxygenation reactions.

4.1. Pd(II)-catalyzed ortho-C–H olefination

Encouraged by our initial success with MPAA ligands, we then evaluated the scaffold’s potential for the enantioselective Pd-catalyzed C(sp2)–H olefination of diphenylacetic acids. High yield and enantioselectivity of olefination product 19 could be achieved using Boc-Ile-OH (L5) (Scheme 8). A unique combination of the sodium salt of diphenylacetic acid 18 and KHCO3 was required for high yield and enantioselectivity. The absolute configuration of product 19 was determined to be (R) by X-ray crystallography.

Scheme 8.

Desymmetrization of diphenylacetic acid substrates.

In addition to desymmetrization approaches, which are limited to substrates with two prochiral C–H bonds, we developed a kinetic resolution strategy for the Pd(II)-catalyzed enantioselective C–H olefination of racemic α-amino and α-hydroxy phenylacetic acids rac-20.39 Using (S)-MPAA L6 as the ligand affords enantioenriched product 21 (Scheme 9) with high s factors. The recovered starting material 20 can undergo C–H olefination using (R)-MPAA ligand L7 to give other product enantiomer 21′ with high yield and enantioselectivity.

Scheme 9.

Kinetic resolution of phenylacetic acid substrates by C–H olefination.

Other compounds can undergo Pd-catalyzed C–H olefinations using MPAAs. We reported a novel free alcohol-directed Pd(II)-catalyzed ortho-C–H olefination in 2010 (Scheme 10).40 Tertiary alcohol substrate 22a give 85% yield of the desired product 23a with (+)-Men-Leu-OH (L8). While secondary and primary alcohols also undergo olefination, they exhibit decreasing reactivity (23b, 23c). Tertiary alcohols benefit the most from conformational restrictions and the Thorpe-Ingold effect, thus accelerating their C–H activation.

Scheme 10.

C(sp2)–H olefination of phenethyl alcohols.

A range of other coordinating groups can also direct ortho-C(sp2)–H olefinations (Scheme 11) in the presence of MPAA ligands. We have employed sulfonamide pharmacophores to direct C(sp2)–H olefinations (Scheme 11a) using Ac-Leu-OH (L9).41 The sulfonamide group overrides the directing effect of many heterocycles, affording exclusive site-selectivity. We also developed an ortho-C–H olefination reaction using Ac-Gly-OH (L10) using an ether as a weak directing group (Scheme 11b).42 The ortho-C(sp2)–H olefination of other weakly directing substrates was achieved (Scheme 11c, d).43

Scheme 11.

ortho-C(sp2)–H olefinations directed by various other directing groups.

4.2. Pd(II)-catalyzed ortho-C–H cross-coupling

In 2006, our group reported the first Pd(II)-catalyzed C(sp2)–H and C(sp3)–H cross-coupling with organometallic reagents, which was then expanded to a wide range of substrates and coupling partners.44 The catalytic efficiency of this reaction has remained low, presenting an opportunity for new ligands to improve reactivity. Encouraged by the remarkable activity of MPAA ligands in C(sp2)–H olefinations, we hypothesized that MPAAs could also accelerate Pd(II)-catalyzed cross-couplings of organoboron reagents (Scheme 12).45 In the absence of ligand, only 17% conversion of 14 was observed. Using Ac-Ile-OH L4 as the ligand and Ag2CO3 as the oxidant, over 99% conversion to arylated product 32 occurred. Furthermore, molecular oxygen, a more practical and industry friendly oxidant compared to silver, was compatible with the MPAA ligand conditions.

Scheme 12.

C(sp2)–H cross-coupling with arylboron reagents.

In 2013, our group further showcased the capability of MPAA (L12) ligand-promoted C(sp2)–H cross-coupling with alkyl boron reagents (Scheme 13).46 Both alkylboronic acids and potassium alkyltrifluoroborates were compatible. A variety of primary alkyl boron reagents, bearing trifluoromethyl, ester, phenyl, Boc-amine, or ketone functional groups, were tolerated. Given the ineffective coupling of methylcyclopropyl/methylcyclobutyl boron reagents and the need for oxygen-free conditions, this reaction likely involves an alkyl radical intermediate.

Scheme 13.

C(sp2)–H cross-coupling with alkylboron reagents.

We also applied MPAA ligands to develop enantioselective Pd(II)-catalyzed C(sp2)–H cross-coupling reactions. In 2015, we reported a MPAA (L13)-enabled, highly enantioselective ortho-C–H cross-coupling of diarylmethylamines with arylboron reagents (Scheme 14a).47 Readily removable para-nitrobenzenesulfonyl (Ns) group was utilized as the directing group. The following year, we disclosed a kinetic resolution approach for the enantioselective C–H cross-coupling of racemic benzylamines 37 using MPAA L14 (Scheme 14b).48 The high s factor meant both product 38 and residual starting material could be obtained in high yield and enantioselectivity. Arylated product 38 was further transformed into chiral 6-substituted 5,6-dihydrophenanthridine 39 without loss of optical activity.

Scheme 14.

Desymmetrization and kinetic resolution of benzylamines.

4.3. Other Pd(II)-catalyzed ortho-C–H functionalizations

Since Heck and co-workers reported the first Pd-catalyzed carbonylation of aryl and vinyl halides in 1974, carbonylation reactions have become powerful tools in organic synthesis.49 In our efforts to use CO as coupling partner in Pd-catalyzed C–H functionalizations, we disclosed the hydroxyl-directed C–H carbonylation of substrate 40 enabled by MPAA ligand L8 (Scheme 15).50 Since both the substrate and CO are fully incorporated into product 41, this transformation is a highly atom- and step-economical route to the isochromanone motif. Phenethyl alcohol 40c underwent C–H carbonylation to achieve a single-step synthesis of N-protected histamine release inhibitor 41c in 62% yield.

Scheme 15.

C(sp2)–H carbonylation of phenethyl alcohols.

We developed a synthesis for α,α-disubstituted benzofuran-2-ones via a Pd(II)-catalyzed C–H activation/C–O bond formation sequence, functionalizing carboxylic acid 42 in excellent yield when using either Boc-Val-OH (L11) or Ac-Gly-OH (L10) ligands (Scheme 16).51 Moreover, the use of Boc-Ile-OH (L5), afforded the chiral benzofuranone product 45 of phenylacetic acid 44 in high enantioselectivity, the first example of enantioselective C–H functionalization via the Pd(II)/Pd(IV) catalytic cycle.

Scheme 16.

C–H activation/C–O bond formation.

Our group also developed the MPAA-enabled Pd(II)/Pd(IV) enantioselective C(sp2)–H iodination of diarylmethylamines.52 This reaction uses inexpensive molecular iodine as the sole oxidant and reagent and proceeds under air at ambient temperatures. Both the identity of MPAA L15 and the combination of Na2CO3 and CsOAc are critical to achieving high enantioselectivity and yield of iodinated products 47 (Scheme 17a). We then reported a kinetic resolution approach for Pd(II)-catalyzed enantioselective C–H iodination, expanding the substrate scope to arylalkylamines (Scheme 17b).53 A broad range of arylalkylamines 48a, β-amino acids 48b, and β-amino alcohols 48c undergo iodination in the presence of l-L15 and the Pd catalyst. The remaining material 48 was subsequently iodinated using Pd with d-L15 to yield the opposite enantiomer 49′ in high enantioselectivity. The You group concurrently reported an enantioselective C(sp2)–H iodination via the kinetic resolution of axially chiral compounds.54

Scheme 17.

Enantioselective C(sp2)–H iodination.

In 2015, we reported a rare example of Pd(II)-catalyzed ortho-alkylation with both terminal and internal epoxides (Scheme 18).55 Both the potassium counterion and Ac-Tle-OH (L16) were essential for increasing reactivity and broadening the coupling partner scope. The alkylation of benzoic acid 50 proceeded in high yield with a wide range of terminal and internal epoxides. When 1,2-disubstituted oxirane was used as a coupling partner, the trans-product 51f was obtained. A redox-neutral SN2 nucleophilic ring-opening process was proposed, as opposed to a Pd(II)/Pd(IV) mechanism, supported by the inversion of stereochemistry in the C–H alkylation.

Scheme 18.

C–H alkylation with epoxides.

4.4. Pd(II)-catalyzed meta-and other remote C–H functionalizations

The selective activation of remote C–H bonds, including meta-C–H bonds, has remained a challenge in the field of C–H functionalization. Chelating directing groups, which form a rigid six- or seven-membered cyclic intermediate prior to C–H activation (pretransition state), strongly favor ortho-selectivity. To achieve meta-selectivity, our lab has developed a class of U-shaped templates which form a macrocyclic cyclophane-like pretransition state to direct the Pd to the meta-C–H bond. We found that MPAA ligands are often essential to achieving high selectivity and reactivity with our meta-directing templates. This section discusses their use in template-directed remote C–H functionalizations.

In 2012, our group reported the meta-C–H olefination of tethered arene substrates in the presence of a class of nitrile-containing templates and MPAA ligands, achieving excellent selectivity (Scheme 19a).56 Uitilizing U-shaped templates T1 and T2, we realized the meta-C–H olefination of hydrocinnamic acids, unnatural amino acids, 2-biphenylcarboxylic acids, and other drug molecules which were difficult to access using traditional C–H functionalization methods. In 2013, we developed the meta-C–H arylation and methylation of 3-phenylpropanoic acid and phenolic derivatives (Scheme 19b).57 We later disclosed a meta-C–H olefination of phenol and phenylacetic acid derivatives.43b, 58 We also developed a uniquely flexible template T3 for the meta-olefination of benzoic acid derivatives (Scheme 19c).59

Scheme 19.

meta-C–H functionalizations directed by a U-shaped template.

The discovery of U-shaped templates T1 and T2 prompted us to investigate the directed activation of C–H bonds which are distal (more than six bonds away) to the functional groups, especially when the target bonds are geometrically inaccessible to directed metalation due to ring strain. We reported a novel template T4 to accommodate the highly strained intermediate with a tricyclic cyclophane structure (Scheme 20).60 MPAA L10 (Ac-Gly-OH) was capable of amplifying the pre-existing conformational biases induced by a single fluorine in the template to accomplish a highly selective remote meta-C–H olefination. Template T4 was broadly used in the meta-C–H functionalization of 2-phenylpiperidines, 2-phenylpyrrolidines and other aniline substrates. In addition to meta-C–H olefination via a Pd(II)/Pd(0) redox cycle, we were able to realize meta-C–H acetoxylations via Pd(II)/Pd(IV) catalysis with the same template.

Scheme 20.

meta-C–H functionalizations of amines.

However, the previously developed templates do not achieve meta-selectivity for indoline substrates. In 2014, we reported the first example of meta-C–H olefination, acetoxylation, and cross-coupling of indolines using template T5 attached to the indolinyl nitrogen via a removable sulfonamide linkage (Scheme 21).61 This reaction is a very useful tool for the preparation of a wide range of meta-substituted indolines, including biologically important drug molecules and natural products. We also investigated remote selective C–H olefinations of isoindoline and tetrahydroisoquinoline, acheiving good selectivity and modest yield.62

Scheme 21.

meta-C–H functionalizations of indolines.

Encouraged by the success of our U-shaped nitrile templates, we envisioned that templates containing a strongly coordinating pyridyl group could also direct remote meta-C–H activation. Following this strategy, we developed the meta-C–H functionalization of benzyl and phenyl ethyl alcohols using pyridine-based template T6 (Scheme 22).63 The 3-pyridyl motif could direct not only meta-C–H olefination, but also meta-iodination, which was not compatible with our previous nitrile-based templates. Using T6, we also developed meta-C–H iodination, olefination, and cross-coupling reactions of phenylacetic acids.64

Scheme 22.

meta-C–H functionalizations using pyridine-based templates.

While new templates have increased the efficiency and scope of meta-C–H functionalizations, this strategy is still limited by the covalent tether of the template to the substrate. We sought to replace the covalent linkage with reversible substrate-metal coordination (Scheme 23).65 In this system, the bis-amide backbone of bifunctional template T7 coordinates a metal center which in turn recruits the substrate via binding with heterocycle nitrogen. The side-arm of the template then directs the Pd(II) catalyst to specific remote C–H bonds, affording the olefination products with excellent yield and meta-selectivity. In exploring this bifunctional concept with different types of heterocycles, we also achieved a C5-selective C–H olefination of quinolines with template T8.

Scheme 23.

Remote site-selective C–H activation with a bifunctional coordinating template.

5. Pd(II)-catalyzed C(sp3)–H functionalization promoted by MPAA ligands

Our original report of MPAA ligand-enabled enantioselective C–H activation/cross-coupling showed that 2-isopropyl pyridine containing enantiotopic gem-dimethyl groups could undergo asymmetric C(sp3)–H functionalization (Scheme 6) using ligand L3, albeit in low yield and ee.6 As previously discussed (vide supra), enantioselective C(sp3)–H activations have a number of challenges, including increased activation energy for C–H bond cleavage relative to C(sp2)–H bonds and racemic background reaction in the presence of strong directing groups. To address these challenges, we designed a range of systematically tuned MPAA ligands not only to achieve high asymmetric induction but to also increase the reactivity of the Pd catalyst, thus accelerating the reaction3 and lowering the reaction temperature. Furthermore, we developed methods that use weakly coordinating directing groups, which ameliorate the issue of background reaction and can either be readily removed or are inherent in the substrate.

In 2011, our group reported the enantioselective C–H functionalization of cyclopropane carboxylic acid derivatives 69 (Scheme 24).66 A range of aryl, vinyl, and alkylboron reagents could be successfully coupled to afford cis-substituted chiral products 70 in good to excellent enantioselectivity. The newly developed MPAA ligand L18 presents three specific features. First, it showed high efficiency, permitting a reduction in reaction temperature to 40 °C, second, the 2,6-diflurophenyl group on the side chain provides a rigid steric environment while protecting the arene from metalation, and last, the TcBoc-based protecting group increases steric size while also tuning the carbamide’s electronics via the inductively withdrawing trichloromethyl motif.

Scheme 24.

Enantioselective C(sp3)–H cross-coupling of cyclopropane acid derivatives.

In 2014, enantioselective C–H cross-coupling of cyclobutane carboxylic acids derivatives 71 with arylboron reagents was reported by our group (Scheme 25).67 The key to achieving high enantioselectivity was replacing the carboxylate with a N-methoxy amide group (L19) – the parent MPAA ligand afforded low yield and poor ee. Presumably, the improved performance stemmed from tighter binding of the N-methoxy amide to the Pd catalyst. This new class of ligands was also effective for the enantioselective C(sp3)–H functionalization of acyclic amides with L20.

Scheme 25.

C(sp3)–H cross-coupling of cyclobutane carboxylic acid derivatives.

The above strategies utilize an amide directing group, which must be installed and removed in additional steps. In 2019, we disclosed a method for the enantioselective C(sp3)–H cross-coupling of free cyclopropane carboxylic acids with aryl and vinyl organoboron regents (Scheme 26) using MPAAs L21/L22.68 This transformation provides rapid access to enantioenriched cyclopropane acid derivatives, a common motif in medicinal and synthetic chemistry.

Scheme 26.

C(sp3)–H cross-coupling of free cyclopropane carboxylic acids using MPAA ligands.

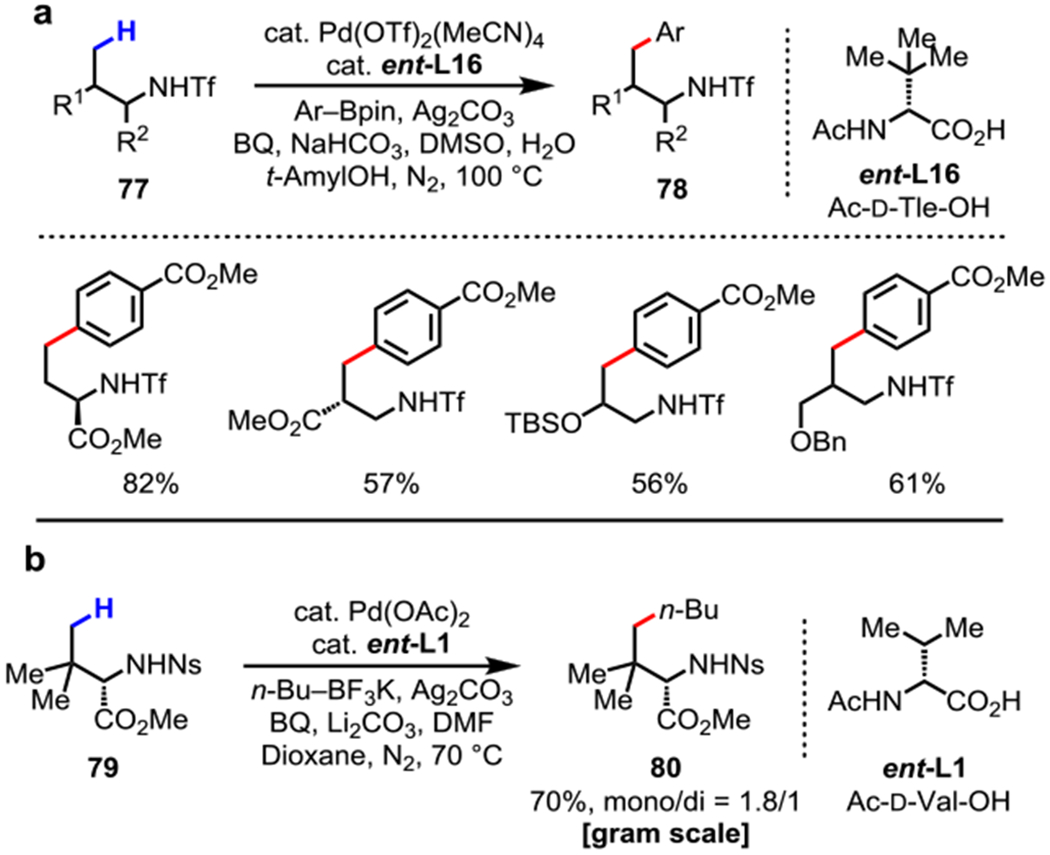

Amines are another major class of synthetically useful compounds. Our group in 2014 developed an MPAA-enabled Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling of γ-C(sp3)–H of triflamides (Tf) 77 with arylboron reagents using ent-L16 (Scheme 27a).69 The triflyl-protected amines can be readily deprotonated to form imidate-like moiety as a weakly coordinating σ donor. A variety of alkyl amines such as 1,2/1,3-amino alcohols and amino acids could be functionalized. However, this method is limited to arylboron reagents and the Tf protecting group is challenging to remove. In 2017, the first γ-C(sp3)–H cross-coupling of readily deprotectable nosyl (Ns)-protected alkyl amines 79 with alkylboron using ent-L1 was realized (Scheme 27b).70 This method was then applied in the gram scale stereoselective synthesis of γ-alkyl-α-amino acids.

Scheme 27.

C(sp3)–H cross-coupling of amine derivatives.

In 2015, we reported the Pd-catalyzed highly enantioselective arylation of cyclopropylmethylamine 81 C–H bonds with aryl iodides using L11 through a Pd(II)/Pd(IV) mechanism (Scheme 28).71 A wide range of electron-donating and electron-withdrawing substituents in para, meta, and ortho-positions on the aryl iodides are compatible, affording good to excellent yields. We later reported a related enantioselective γ-C(sp3)–H cross-coupling of acyclic alkyl amines with diverse aryl- and vinyl-boron reagents using chiral APAO ligands, derived amino acids.72

Scheme 28.

Enantioselective C(sp3)–H functionalization of amines.

6. Applications to complex molecule synthesis

Over the past ten years, the rapid development in MPAA ligand-promoted C–H functionalization has produced numerous site- and stereo-selective C–H functionalization technologies capable of operating with the predictability and precision required for complex molecule assembly. As a consequence, many of these methods have been applied in the synthesis of complex targets such as pharmaceutical agents and natural products.73

Lithospermic acid has been implicated as an active component in Danshen, one of the most popular traditional herbs used in the treatment of cardiovascular disorders, cerebrovascular diseases, hepatitis, chronic renal failure, and dysmenorrhea. In 2011, we disclosed a total synthesis of (+)-lithospermic acid greatly expedited by late-stage C(sp2)–H functionalization, a Pd-catalyzed intermolecular C–H olefination accelerated by L4 (Ac-Ile-OH). The dihydrobenzofuran core 83 and the olefin unit 84 are unified in a highly convergent fashion to yield hexamethyl lithospermate 85 (Scheme 29), which can be readily deprotected to the natural product.74

Scheme 29.

Application of a C–H olefination towards the synthesis of (+)-lithospermic acid.

(+)-Hongoquercin A is a sesquiterpenoid antibiotic of fungal origin. Its structure inspired the Baran lab, in collaboration with our group, to pursue a unique approach using novel C–H functionalizations as key retrosynthetic disconnections. Specifically, benzoic acid moiety 86 was proposed to direct two sequential site-selective C(sp2)–H functionalization reactions – methylation and oxidation (Scheme 30). Through extensive ligand development and reaction screening, Pd(OAc)2 and Boc-Phe-OH (L23) afforded the desired methylated carboxylic acid 87 in 45% yield, along with the bis-alkylated product 88 in 15% yield. Compound 87 was then oxidized using catalytic Pd(OAc)2 under O2 to the natural product.

Scheme 30.

Application of C–H alkylation in the synthesis of (+)-hongoquercin A.

(−)-Incarviatone A was first isolated as a unique natural product hybrid in 2012. Preliminary biological evaluation indicated its potential as a novel monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitor (IC50 29 nM). In their synthetic studies, the Lei group applied consecutive C–H functionalizations for the rapid assembly of the highly functionalized indane core (Scheme 31). The synthesis commenced with ortho-C–H alkylation of 89 using MPAA L12.73d Subsequent rhodium-catalyzed C–H insertion and Pd(II)-catalyzed C–H iodination formed indane 92.

Scheme 31.

Consecutive C–H functionalizations towards synthesis of (−)-incarvitone A.

MPAA ligand-promoted C–H functionalization was featured in a 2016 synthesis of the tricyclic core of the indoxamycin family of secondary metabolites. In the presence of L10, intramolecular ortho-olefination of 93 with a weakly coordinating ester was achieved (Scheme 32).75 Substituted variants of 93 were subjected to the aforementioned conditions and olefinated in moderate yields and excellent diastereomeric ratios.

Scheme 32.

Construction of benzo-fused indoxamycin cores via C–H olefination.

In the same year, Sarpong’s group completed formal syntheses of herbindole B and cis-trikentrin A via a novel Pd-catalyzed C(sp3)–H activation/indolization reaction using L4 (Scheme 33).76 Inspired by our Pd-catalyzed γ-C(sp3)–H cross-coupling of triflyl-protected amines,71 an intramolecular C(sp3)–H amination/indole formation of Tf-protected ethylanilines was designed and realized for both natural products.

Scheme 33.

C–H amination/indolization in the formal syntheses of herbindole B and cis-trikenterin A.

Delavatine A is a structurally unusual isoquinoline alkaloid isolated from Incarvillea delavayi. Zhang developed a C–H kinetic resolution approach for the asymmetric synthesis of the fused indane core.73e Using MPAA ligand L7, enantioselective C–H olefination of triflamide-protected phenylethylamine derivatives rac-99 provided enantioenriched 100 on five-gram scale (Scheme 34), which could be carried on to give delavatine A. The remaining enantiomer of 99 could be olefinated using ent-L7.

Scheme 34.

Kinetic resolution of triflamides via C–H olefination for the synthesis of delavatine A.

7. Future Outlook and Conclusion

The development and application of ligands for facilitating and controlling C–H activation has been the major goal of our research program in Pd(II)-catalyzed C–H functionalization. MPAA ligand acceleration via bifunctional C–H activation has enabled the development of many new Pd(II)-catalyzed C–H functionalization reactions. MPAAs have been instrumental in the development of ligand-accelerated reactions of unreactive substrates, enantioselective C–H activations of both prochiral bonds and symmetrical substrates, as well as site-selective C–H activation. These methods have been applied in a number of total syntheses, demonstrating their practicality and functional group compatibility.

Furthermore, mechanistic studies have identified the key structural elements of MPAAs that influence C–H activation, specifically the bidentate coordination of the carboxylate and amide and the active participation of the N-acyl group in C–H cleavage. Inspired by these insights, we have designed a new generation of ligands derived from amino acids (Figure 10), including N-acyl protected aminomethyl oxazoline (APAO) ligands capable of the highly enantioselective C–H desymmetrization of prochiral methyl groups in isobutyramides,77 mono-N-protected aminoethyl amine (MPAAM) ligands for the enantioselective C–H arylation of cyclopropanecarboxylic and 2-aminoisobutyric acids,78 and mono-N-protected aminoethyl thioether (MPAThio) ligands for enabling the C–H olefination of simple free acids.79 Our lab has also developed related APAQ ligands for the enantioselective arylation of methylene C(sp3)–H bonds, a long-standing challenge in Pd-catalyzed C–H functionalization.80

Figure 10.

Next generation ligand design based on MPAA mechanistic understanding.

Other research groups have applied MPAA ligands to enable difficult Pd-catalyzed C–H functionalizations, including Martin for the C(sp3)–H lactonization of benzoic acids,81 Gaunt for the C(sp3)–H functionalization of hindered secondary amines82 and C(sp3)–H cross-coupling of tertiary amines,83 You,54, 84 and others.85 In addition, MPAAs derived from β-amino acids, which bind in a six-membered chelate to Pd, have recently been reported as ligands for the arylation86 as well as the highly efficient C(sp3)–H lactonization87 and acetoxylation88 of free acid substrates. Finally, MPAAs have also emerged as promising ligands for achieving high reactivity and selectivity in C–H functionalization with other metals, including Rh(III)89 and Ru(II).90

We believe that MPAA ligands, as well as ligand classes inspired by their structure, could enable the discovery of many new and useful metal-catalyzed C–H functionalization reactions. The discovery and development of MPAAs as ligands for Pd-catalyzed C–H functionalizations is an illustrative example of the power of ligand development for realizing the untapped potential of C–H functionalization as synthetic strategy. As a central challenge in the field, it continues to stimulate and inspire us.

Acknowledgements.

We are indebted to all present and former group members for their invaluable contributions to the work described herein. We gratefully acknowledge TSRI, the NIH (NIGMS, 2R01 GM084019), and Bristol–Meyers Squibb for financial assistance.

Biographies

Biographies

Qian Shao received her B.Sc. in Pharmaceutics from Ocean University of China in 2009. In the same year, she moved to Peking University, where she received her Ph.D. in Organic Chemistry under the direction of Prof. Yong Huang. She is currently a postdoctoral fellow in the lab of Prof. Jin-Quan Yu at The Scripps Research Institute.

Kevin Wu received his B.Sc. in Chemistry from Boston College in 2011, working in Prof. Amir Hoveyda’s lab. He did his Ph.D. studies in Chemistry at Princeton University in Prof. Abigail Doyle’s lab, graduating in 2017. He is currently a postdoctoral scientist in Prof. Jin-Quan Yu’s lab.

Zhe Zhuang was born in Zhoushan, China. He received predoctoral training in Prof. Wei-Wei Liao’s lab (B.Sc., 2013, Jilin university) and Prof. Zhi-Xiang Yu’s lab (2014–2015, Peking University). He is now a fifth-year graduate student in Prof. Jin-Quan Yu’s lab.

Shaoqun Qian was born in Shanghai, China. He received predoctoral training in Prof. Renhua Fan’s lab (B.Sc., 2017, Fudan university). He is now a third-year graduate student in Prof. Jin-Quan Yu’s lab.

Jin-Quan Yu received his B.Sc. in Chemistry from East China Normal University and his M.Sc. from the Guangzhou Institute of Chemistry. In 2000, he obtained his Ph.D. at the University of Cambridge with Prof. Jonathan B. Spencer. After some time as a Junior Research Fellow at Cambridge, he joined the laboratory of Prof. E. J. Corey at Harvard University as a postdoctoral fellow. He then began his independent career at Cambridge (2003–2004), before moving to Brandeis University (2004–2007), and finally The Scripps Research Institute, where he is currently the Frank and Bertha Hupp Professor of Chemistry.

References

- 1.(a) Arndtsen BA; Bergman RG; Mobley TA; Peterson TH, Selective Intermolecular Carbon-Hydrogen Bond Activation by Synthetic Metal Complexes in Homogeneous Solution. Acc. Chem. Res 1995, 28, 154–162 [Google Scholar]; (b) Davies HML; Manning JR, Catalytic C–H functionalization by metal carbenoid and nitrenoid insertion. Nature 2008, 451, 417–424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Daugulis O; Do H-Q; Shabashov D, Palladium- and Copper-Catalyzed Arylation of Carbon–Hydrogen Bonds. Acc. Chem. Res 2009, 42, 1074–1086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Roizen JL; Harvey ME; Du Bois J, Metal-Catalyzed Nitrogen-Atom Transfer Methods for the Oxidation of Aliphatic C–H Bonds. Acc. Chem. Res 2012, 45, 911–922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Daugulis O; Roane J; Tran LD, Bidentate, Monoanionic Auxiliary-Directed Functionalization of Carbon–Hydrogen Bonds. Acc. Chem. Res 2015, 48, 1053–1064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Hartwig JF, Catalyst-Controlled Site-Selective Bond Activation. Acc. Chem. Res 2017, 50, 549–555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Davies HML; Morton D, Collective Approach to Advancing C–H Functionalization. ACS Central Science 2017, 3, 936–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Chen X; Engle KM; Wang D-H; Yu J-Q, Palladium(II)-Catalyzed C–H Activation/C–C Cross-Coupling Reactions: Versatility and Practicality. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2009, 48, 5094–5115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lyons TW; Sanford MS, Palladium-Catalyzed Ligand-Directed C–H Functionalization Reactions. Chem. Rev 2010, 110, 1147–1169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) He J; Wasa M; Chan KSL; Shao Q; Yu J-Q, Palladium-Catalyzed Transformations of Alkyl C–H Bonds. Chemical Reviews 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berrisford DJ; Bolm C; Sharpless KB, Ligand-Accelerated Catalysis. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 1995, 34, 1059–1070. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engle KM; Yu J-Q, Developing Ligands for Palladium(II)-Catalyzed C–H Functionalization: Intimate Dialogue between Ligand and Substrate. The Journal of Organic Chemistry 2013, 78, 8927–8955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saint-Denis TG; Zhu R-Y; Chen G; Wu Q-F; Yu J-Q, Enantioselective C(sp3)–H bond activation by chiral transition metal catalysts. Science 2018, 359, eaao4798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shi B-F; Maugel N; Zhang Y-H; Yu J-Q, PdII-Catalyzed Enantioselective Activation of C(sp2)–H and C(sp3)–H Bonds Using Monoprotected Amino Acids as Chiral Ligands. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2008, 47, 4882–4886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Engle KM, The mechanism of palladium(II)-mediated C–H cleavage with mono-N-protected amino acid (MPAA) ligands: origins of rate acceleration. In Pure Appl. Chem, 2016; Vol. 88, p 119. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noyori R; Koizumi M; Ishii D; Ohkuma T, Asymmetric hydrogenation via architectural and functional molecular engineering. In Pure Appl. Chem, 2001; Vol. 73, p 227. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gunanathan C; Milstein D, Metal–Ligand Cooperation by Aromatization–Dearomatization: A New Paradigm in Bond Activation and “Green” Catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res 2011, 44, 588–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Bruce MI, Cyclometalation Reactions. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 1977, 16, 73–86 [Google Scholar]; (b) Vicente J; Saura-Llamas I; Palin MG; Jones PG; Ramírez de Arellano MC, Orthometalation of Primary Amines. 4.1 Orthopalladation of Primary Benzylamines and (2-Phenylethyl)amine. Organometallics 1997, 16, 826–833. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cope AC; Siekman RW, Formation of Covalent Bonds from Platinum or Palladium to Carbon by Direct Substitution. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1965, 87, 3272–3273. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cope AC; Friedrich EC, Electrophilic aromatttic substitution reactions by platinum(II) and palladium(II) chlorides on N,N-dimethylbenzylamines. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1968, 90, 909–913. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moynahan EB; Popp FD; Werneke MF, Ferrocene studies III. Platinum and palladium complexes of [(dimethylamino)methyl]ferrocene. J. Organomet. Chem 1969, 19, 229–232. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaunt JC; Shaw BL, Transition metal · carbon bonds: XL. Palladium(II) complexes of [(dimethylamino)methyl]-ferrocene. J. Organomet. Chem 1975, 102, 511–516. [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Duff JM; Shaw BL, Complexes of iridium(III) and rhodium(III) with metallated and unmetallated dimethyl(1-naphthyl)- and methylphenyl(1-naphthyl)-phosphine. Journal of the Chemical Society, Dalton Transactions 1972, 2219–2225 [Google Scholar]; (b) Duff JM; Mann BE; Shaw BL; Turtle B, Transition metal–carbon bonds. Part XXXVI. Internal metallations of platinum–dimethyl(1-naphthyl)phosphine and –dimethyl(1-naphthyl)arsine complexes and attempts to effect similar reactions with palladium. Journal of the Chemical Society, Dalton Transactions 1974, 139–145. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sokolov VI; Troitskaya LL; Reutov OA, Asymmetric cyclopalladation of dimethylaminomethylferrocene. J. Organomet. Chem 1979, 182, 537–546. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Constable AG; McDonald WS; Sawkins LC; Shaw BL, Palladation of dimethylhydrazones, oximes, and oxime O-allyl ethers: crystal structure of [Pd3(ON = CPriPh)6]. Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications 1978, 1061–1062. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryabov AD; Sakodinskaya IK; Yatsimirsky AK, Kinetics and mechanism of orthopalladation of ring-substituted NN-dimethylbenzylamines. Journal of the Chemical Society, Dalton Transactions 1985, 2629–2638. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gómez M; Granell J; Martinez M, Variable-Temperature and -Pressure Kinetics and Mechanism of the Cyclopalladation Reaction of Imines in Aprotic Solvent. Organometallics 1997, 16, 2539–2546. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davies DL; Donald SMA; Macgregor SA, Computational Study of the Mechanism of Cyclometalation by Palladium Acetate. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 13754–13755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lafrance M; Rowley CN; Woo TK; Fagnou K, Catalytic Intermolecular Direct Arylation of Perfluorobenzenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 8754–8756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.García-Cuadrado D; Braga AAC; Maseras F; Echavarren AM, Proton Abstraction Mechanism for the Palladium-Catalyzed Intramolecular Arylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 1066–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lapointe D; Fagnou K, Overview of the Mechanistic Work on the Concerted Metallation–Deprotonation Pathway. Chemistry Letters 2010, 39, 1118–1126. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boutadla Y; Davies DL; Macgregor SA; Poblador-Bahamonde AI, Mechanisms of C–H bond activation: rich synergy between computation and experiment. Dalton Transactions 2009, 5820–5831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sokolov VI; Troitskaya LL; Reutov OA, Asymmetric induction in the course of internal palladation of enantiomeric 1-dimethylaminoethylferrocene. J. Organomet. Chem 1977, 133, C28–C30. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kozitsyna NY; Martens MV; Stolyarov IP; Gekhman AE; Vargaftik MN; Moiseev II, The effects of the solvent and the ligand chirality on the regioselectivity of alkene oxidative esterification by PdII carboxylates. Russian Chemical Bulletin 1999, 48, 1673–1681. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giri R; Chen X; Yu J-Q, Palladium-Catalyzed Asymmetric Iodination of Unactivated C–H Bonds under Mild Conditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2005, 44, 2112–2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giri R; Liang J; Lei J-G; Li J-J; Wang D-H; Chen X; Naggar IC; Guo C; Foxman BM; Yu J-Q, Pd-Catalyzed Stereoselective Oxidation of Methyl Groups by Inexpensive Oxidants under Mild Conditions: A Dual Role for Carboxylic Anhydrides in Catalytic C–H Bond Oxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2005, 44, 7420–7424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Engle KM; Wang D-H; Yu J-Q, Ligand-Accelerated C–H Activation Reactions: Evidence for a Switch of Mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 14137–14151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang D-H; Engle KM; Shi B-F; Yu J-Q, Ligand-Enabled Reactivity and Selectivity in a Synthetically Versatile Aryl C–H Olefination. Science 2010, 327, 315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Günay ME; Richards CJ, Synthesis of Planar Chiral Phosphapalladacycles by N-Acyl Amino Acid Mediated Enantioselective Palladation. Organometallics 2009, 28, 5833–5836. [Google Scholar]

- 32.(a) Gair JJ; Haines BE; Filatov AS; Musaev DG; Lewis JC, Mono-N-protected amino acid ligands stabilize dimeric palladium(II) complexes of importance to C–H functionalization. Chemical Science 2017, 8, 5746–5756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gair JJ; Haines BE; Filatov AS; Musaev DG; Lewis JC, Di-Palladium Complexes are Active Catalysts for Mono-N-Protected Amino Acid-Accelerated Enantioselective C–H Functionalization. ACS Catal 2019, 11386–11397. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Musaev DG; Kaledin A; Shi B-F; Yu J-Q, Key Mechanistic Features of Enantioselective C–H Bond Activation Reactions Catalyzed by [(Chiral Mono-N-Protected Amino Acid)–Pd(II)] Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 1690–1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheng G-J; Yang Y-F; Liu P; Chen P; Sun T-Y; Li G; Zhang X; Houk KN; Yu J-Q; Wu Y-D, Role of N-Acyl Amino Acid Ligands in Pd(II)-Catalyzed Remote C–H Activation of Tethered Arenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 894–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park Y; Niemeyer ZL; Yu J-Q; Sigman MS, Quantifying Structural Effects of Amino Acid Ligands in Pd(II)-Catalyzed Enantioselective C–H Functionalization Reactions. Organometallics 2018, 37, 203–210. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng G-J; Chen P; Sun T-Y; Zhang X; Yu J-Q; Wu Y-D, A Combined IM-MS/DFT Study on [Pd(MPAA)]-Catalyzed Enantioselective C–H Activation: Relay of Chirality through a Rigid Framework. Chemistry – A European Journal 2015, 21, 11180–11188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.(a) Whitesell JK, C2 symmetry and asymmetric induction. Chem. Rev 1989, 89, 1581–1590 [Google Scholar]; (b) Yoon TP; Jacobsen EN, Privileged Chiral Catalysts. Science 2003, 299, 1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jain P; Verma P; Xia G; Yu J-Q, Enantioselective amine α-functionalization via palladium-catalysed C–H arylation of thioamides. Nature Chemistry 2017, 9, 140–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xiao K-J; Chu L; Yu J-Q, Enantioselective C–H Olefination of α-Hydroxy and α-Amino Phenylacetic Acids by Kinetic Resolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55, 2856–2860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu Y; Wang D-H; Engle KM; Yu J-Q, Pd(II)-Catalyzed Hydroxyl-Directed C–H Olefination Enabled by Monoprotected Amino Acid Ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 5916–5921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dai H-X; Stepan AF; Plummer MS; Zhang Y-H; Yu J-Q, Divergent C–H Functionalizations Directed by Sulfonamide Pharmacophores: Late-Stage Diversification as a Tool for Drug Discovery. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 7222–7228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li G; Leow D; Wan L; Yu J-Q, Ether-Directed ortho-C–H Olefination with a Palladium(II)/Monoprotected Amino Acid Catalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2013, 52, 1245–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.(a) Li G; Wan L; Zhang G; Leow D; Spangler J; Yu J-Q, Pd(II)-Catalyzed C–H Functionalizations Directed by Distal Weakly Coordinating Functional Groups. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 4391–4397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dai H-X; Li G; Zhang X-G; Stepan AF; Yu J-Q, Pd(II)-Catalyzed ortho- or meta-C–H Olefination of Phenol Derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 7567–7571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.(a) Chen X; Li J-J; Hao X-S; Goodhue CE; Yu J-Q, Palladium-Catalyzed Alkylation of Aryl C–H Bonds with sp3 Organotin Reagents Using Benzoquinone as a Crucial Promoter. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 78–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chen X; Goodhue CE; Yu J-Q, Palladium-Catalyzed Alkylation of sp2 and sp3 C–H Bonds with Methylboroxine and Alkylboronic Acids: Two Distinct C–H Activation Pathways. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 12634–12635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Engle KM; Thuy-Boun PS; Dang M; Yu J-Q, Ligand-Accelerated Cross-Coupling of C(sp2)–H Bonds with Arylboron Reagents. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 18183–18193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thuy-Boun PS; Villa G; Dang D; Richardson P; Su S; Yu J-Q, Ligand-Accelerated ortho-C–H Alkylation of Arylcarboxylic Acids using Alkyl Boron Reagents. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 17508–17513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laforteza BN; Chan KSL; Yu J-Q, Enantioselective ortho-C–H Cross-Coupling of Diarylmethylamines with Organoborons. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2015, 54, 11143–11146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xiao K-J; Chu L; Chen G; Yu J-Q, Kinetic Resolution of Benzylamines via Palladium(II)-Catalyzed C–H Cross-Coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 7796–7800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.(a) Schoenberg A; Bartoletti I; Heck RF, Palladium-catalyzed carboalkoxylation of aryl, benzyl, and vinylic halides. The Journal of Organic Chemistry 1974, 39, 3318–3326 [Google Scholar]; (b) (b) Schoenberg A; Heck RF, Palladium-catalyzed amidation of aryl, heterocyclic, and vinylic halides. The Journal of Organic Chemistry 1974, 39, 3327–3331. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lu Y; Leow D; Wang X; Engle KM; Yu J-Q, Hydroxyl-directed C–H carbonylation enabled by mono-N-protected amino acid ligands: An expedient route to 1-isochromanones. Chemical Science 2011, 2, 967–971. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cheng X-F; Li Y; Su Y-M; Yin F; Wang J-Y; Sheng J; Vora HU; Wang X-S; Yu J-Q, Pd(II)-Catalyzed Enantioselective C–H Activation/C–O Bond Formation: Synthesis of Chiral Benzofuranones. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 1236–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chu L; Wang X-C; Moore CE; Rheingold AL; Yu J-Q, Pd-Catalyzed Enantioselective C–H Iodination: Asymmetric Synthesis of Chiral Diarylmethylamines. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 16344–16347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chu L; Xiao K-J; Yu J-Q, Room-temperature enantioselective C–H iodination via kinetic resolution. Science 2014, 346, 451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gao D-W; Gu Q; You S-L, Pd(II)-Catalyzed Intermolecular Direct C–H Bond Iodination: An Efficient Approach toward the Synthesis of Axially Chiral Compounds via Kinetic Resolution. ACS Catal 2014, 4, 2741–2745. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cheng G; Li T-J; Yu J-Q, Practical Pd(II)-Catalyzed C–H Alkylation with Epoxides: One-Step Syntheses of 3,4-Dihydroisocoumarins. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 10950–10953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leow D; Li G; Mei T-S; Yu J-Q, Activation of remote meta-C–H bonds assisted by an end-on template. Nature 2012, 486, 518–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wan L; Dastbaravardeh N; Li G; Yu J-Q, Cross-Coupling of Remote meta-C–H Bonds Directed by a U-Shaped Template. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 18056–18059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Deng Y; Yu J-Q, Remote meta-C–H Olefination of Phenylacetic Acids Directed by a Versatile U-Shaped Template. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2015, 54, 888–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fang L; Saint-Denis TG; Taylor BLH; Ahlquist S; Hong K; Liu S; Han L; Houk KN; Yu J-Q, Experimental and Computational Development of a Conformationally Flexible Template for the meta-C–H Functionalization of Benzoic Acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 10702–10714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tang R-Y; Li G; Yu J-Q, Conformation-induced remote meta-C–H activation of amines. Nature 2014, 507, 215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yang G; Lindovska P; Zhu D; Kim J; Wang P; Tang R-Y; Movassaghi M; Yu J-Q, Pd(II)-Catalyzed meta-C–H Olefination, Arylation, and Acetoxylation of Indolines Using a U-Shaped Template. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 10807–10813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang G; Zhu D; Wang P; Tang R-Y; Yu J-Q, Remote C–H Activation of Various N-Heterocycles Using a Single Template. Chemistry – A European Journal 2018, 24, 3434–3438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chu L; Shang M; Tanaka K; Chen Q; Pissarnitski N; Streckfuss E; Yu J-Q, Remote Meta-C–H Activation Using a Pyridine-Based Template: Achieving Site-Selectivity via the Recognition of Distance and Geometry. ACS Central Science 2015, 1, 394–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jin Z; Chu L; Chen Y-Q; Yu J-Q, Pd-Catalyzed Remote Meta-C–H Functionalization of Phenylacetic Acids Using a Pyridine Template. Org. Lett 2018, 20, 425–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang Z; Tanaka K; Yu J-Q, Remote site-selective C–H activation directed by a catalytic bifunctional template. Nature 2017, 543, 538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wasa M; Engle KM; Lin DW; Yoo EJ; Yu J-Q, Pd(II)-Catalyzed Enantioselective C–H Activation of Cyclopropanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 19598–19601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xiao K-J; Lin DW; Miura M; Zhu R-Y; Gong W; Wasa M; Yu J-Q, Palladium(II)-Catalyzed Enantioselective C(sp3)–H Activation Using a Chiral Hydroxamic Acid Ligand. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 8138–8142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hu L; Shen P-X; Shao Q; Hong K; Qiao JX; Yu J-Q, PdII-Catalyzed Enantioselective C(sp3)–H Activation/Cross-Coupling Reactions of Free Carboxylic Acids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58, 2134–2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chan KSL; Wasa M; Chu L; Laforteza BN; Miura M; Yu J-Q, Ligand-enabled cross-coupling of C(sp3)–H bonds with arylboron reagents via Pd(II)/Pd(0) catalysis. Nature Chemistry 2014, 6, 146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shao Q; He J; Wu Q-F; Yu J-Q, Ligand-Enabled γ-C(sp3)–H Cross-Coupling of Nosyl-Protected Amines with Aryl- and Alkylboron Reagents. ACS Catal 2017, 7, 7777–7782. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chan KSL; Fu H-Y; Yu J-Q, Palladium(II)-Catalyzed Highly Enantioselective C–H Arylation of Cyclopropylmethylamines. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 2042–2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shao Q; Wu Q-F; He J; Yu J-Q, Enantioselective γ-C(sp3)–H Activation of Alkyl Amines via Pd(II)/Pd(0) Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 5322–5325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.(a) Wang H; Li G; Engle KM; Yu J-Q; Davies HML, Sequential C–H Functionalization Reactions for the Enantioselective Synthesis of Highly Functionalized 2,3-Dihydrobenzofurans. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 6774–6777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Li Y; Ding Y-J; Wang J-Y; Su Y-M; Wang X-S, Pd-Catalyzed C–H Lactonization for Expedient Synthesis of Biaryl Lactones and Total Synthesis of Cannabinol. Org. Lett 2013, 15, 2574–2577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ito M; Namie R; Krishnamurthi J; Miyamae H; Takeda K; Nambu H; Hashimoto S, Asymmetric Total Synthesis of (−)-trans-Blechnic Acid via Rhodium(II)-Catalyzed C–H Insertion and Palladium(II)-Catalyzed C–H Olefination Reactions. Synlett 2014, 25, 288–292 [Google Scholar]; (d) Hong B; Li C; Wang Z; Chen J; Li H; Lei X, Enantioselective Total Synthesis of (−)-Incarviatone A. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 11946–11949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Zhang Z; Wang J; Li J; Yang F; Liu G; Tang W; He W; Fu J-J; Shen Y-H; Li A; Zhang W-D, Total Synthesis and Stereochemical Assignment of Delavatine A: Rh-Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Indene-Type Tetrasubstituted Olefins and Kinetic Resolution through Pd-Catalyzed Triflamide-Directed C–H Olefination. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 5558–5567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Qi C; Wang W; Reichl KD; McNeely J; Porco JA Jr., Total Synthesis of Aurofusarin: Studies on the Atropisomeric Stability of Bis-Naphthoquinones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57, 2101–2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang D-H; Yu J-Q, Highly Convergent Total Synthesis of (+)-Lithospermic Acid via a Late-Stage Intermolecular C–H Olefination. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 5767–5769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bedell TA; Hone GAB; Valette D; Yu J-Q; Davies HML; Sorensen EJ, Rapid Construction of a Benzo-Fused Indoxamycin Core Enabled by Site-Selective C–H Functionalizations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55, 8270–8274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Leal RA; Bischof C; Lee YV; Sawano S; McAtee CC; Latimer LN; Russ ZN; Dueber JE; Yu J-Q; Sarpong R, Application of a Palladium-Catalyzed C–H Functionalization/Indolization Method to Syntheses of cis-Trikentrin A and Herbindole B. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55, 11824–11828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wu Q-F; Shen P-X; He J; Wang X-B; Zhang F; Shao Q; Zhu R-Y; Mapelli C; Qiao JX; Poss MA; Yu J-Q, Formation of α-chiral centers by asymmetric β-C(sp3)–H arylation, alkenylation, and alkynylation. Science 2017, 355, 499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shen P-X; Hu L; Shao Q; Hong K; Yu J-Q, Pd(II)-Catalyzed Enantioselective C(sp3)–H Arylation of Free Carboxylic Acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 6545–6549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhuang Z; Yu C-B; Chen G; Wu Q-F; Hsiao Y; Joe CL; Qiao JX; Poss MA; Yu J-Q, Ligand-Enabled β-C(sp3)–H Olefination of Free Carboxylic Acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 10363–10367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chen G; Gong W; Zhuang Z; Andrä MS; Chen Y-Q; Hong X; Yang Y-F; Liu T; Houk KN; Yu J-Q, Ligand-accelerated enantioselective methylene C(sp3)–H bond activation. Science 2016, 353, 1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Novák P; Correa A; Gallardo-Donaire J; Martin R, Synergistic Palladium-Catalyzed C(sp3)–H Activation/C(sp3)–O Bond Formation: A Direct, Step-Economical Route to Benzolactones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2011, 50, 12236–12239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.(a) He C; Gaunt MJ, Ligand-Enabled Catalytic C–H Arylation of Aliphatic Amines by a Four-Membered-Ring Cyclopalladation Pathway. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2015, 54, 15840–15844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) He C; Gaunt MJ, Ligand-assisted palladium-catalyzed C–H alkenylation of aliphatic amines for the synthesis of functionalized pyrrolidines. Chemical Science 2017, 8, 3586–3592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rodrigalvarez J; Nappi M; Azuma H; Flodén NJ; Burns ME; Gaunt MJ, Catalytic C(sp3)–H bond activation in tertiary alkylamines. Nature Chemistry 2020, 12, 76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gao D-W; Shi Y-C; Gu Q; Zhao Z-L; You S-L, Enantioselective Synthesis of Planar Chiral Ferrocenes via Palladium-Catalyzed Direct Coupling with Arylboronic Acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 86–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bag S; Jayarajan R; Dutta U; Chowdhury R; Mondal R; Maiti D, Remote meta-C–H Cyanation of Arenes Enabled by a Pyrimidine-Based Auxiliary. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56, 12538–12542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ghosh KK; van Gemmeren M, Pd-Catalyzed β-C(sp3)–H Arylation of Propionic Acid and Related Aliphatic Acids. Chemistry – A European Journal 2017, 23, 17697–17700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhuang Z; Yu J-Q, Lactonization as a general route to β-C(sp3)–H functionalization. Nature 2020, 577, 656–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhuang Z; Herron AN; Fan Z; Yu J-Q, Ligand-Enabled Monoselective β-C(sp3)–H Acyloxylation of Free Carboxylic Acids Using a Practical Oxidant. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 6769–6776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.(a) Presset M; Oehlrich D; Rombouts F; Molander GA, Complementary Regioselectivity in Rh(III)-Catalyzed Insertions of Potassium Vinyltrifluoroborate via C–H Activation: Preparation and Use of 4-Trifluoroboratotetrahydroisoquinolones. Org. Lett 2013, 15, 1528–1531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lu Y; Wang H-W; Spangler JE; Chen K; Cui P-P; Zhao Y; Sun W-Y; Yu J-Q, Rh(III)-catalyzed C–H olefination of N-pentafluoroaryl benzamides using air as the sole oxidant. Chemical Science 2015, 6, 1923–1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Li J; Warratz S; Zell D; De Sarkar S; Ishikawa EE; Ackermann L, N-Acyl Amino Acid Ligands for Ruthenium(II)-Catalyzed meta-C–H tert-Alkylation with Removable Auxiliaries. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 13894–13901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]