Abstract

Background:

Although several researchers have analyzed the dental identity of patients experience with corrective methods using fixed and removable appliances, the consequences stay debatable. This meta-analysis intended to verify whether the periodontal status of removable appliances is similar to that of the conventional fixed appliances.

Methods:

Relevant literature was retrieved from the database of Cochrane library, PubMed, EMBASE, and CNKI until December 2019, without time or language restrictions. Comparative clinical studies assessing periodontal conditions between removable appliances and fixed appliances were included for analysis. The data was analyzed using the Stata 12.0 software.

Results:

A total of 13 articles involving 598 subjects were selected for this meta-analysis. We found that the plaque index (PLI) identity of the removable appliances group was significantly lower compared to the fixed appliances group at 3 months (OR = −0.57, 95% CI: −0.98 to −0.16, P = .006) and 6 months (OR = −1.10, 95% CI: −1.60 to −0.61, P = .000). The gingival index (GI) of the removable appliances group was lower at 6 months (OR = −1.14, 95% CI: −1.95 to −0.34, P = .005), but the difference was not statistically significant at 3 months (OR = −0.20, 95% CI: −0.50 to 0.10, P = .185) when compared with that of the fixed appliances group. The sulcus probing depth (SPD) of the removable appliances group was lower compared to the fixed appliances group at 3 months (OR = −0.26, 95% CI: −0.52 to −0.01, P = .047) and 6 months (OR = −0.42, 95% CI: −0.83 to −0.01, P = .045). The shape of the funnel plot was symmetrical, indicating no obvious publication bias in the Begg test (P = .174); the Egger test also indicated no obvious publication bias (P = .1).

Conclusion:

Our meta-analysis demonstrated that malocclusion patients treated with the removable appliances demonstrated a better periodontal status as compared with those treated with fixed orthodontic appliances. However, the analyses of more numbers of clinical trials are warranted to confirm this conclusion.

Keywords: fixed appliances, meta-analysis, orthodontic, periodontal health status, removable thermoplastic appliances

1. Introduction

In the present age, the advancements in the design and manufacturing of dental motion materials using computer has encouraged the demand for optimized requirements in orthodontic treatment technology. In 1946, Kesling first proposed the concept of moving orthodontic appliances to move misplaced teeth.[1] However, in the last decade, the concentrated cell method has also been a preferred treatment as it covers a range of malocclusion types.[2] However, several researchers have successfully demonstrated how the present appliances can correct and treat almost all diseases, ranging from mild to severe malocclusion, with better periodontal status.[3–5] Despite the known effectiveness of conventional methods practiced across the world, the shortcomings associated with these methods cannot be overlooked. For instance, the conventional methods in dentistry are inconvenient and even painful, often posing difficulty in cleaning. Patients are required to be cautious with the stent and are required to regularly clean the plaque collected around the wire to improve the oxidation-reduction potential. Previous studies have reported that the use of fixed orthotics can stimulate the growth of subgingival plaques, which trigger adverse reactions and increase the discomfort of patients.[6–8] Therefore, the use of an alternate removable orthodontic device is expected to facilitate convenience and better healing for patients requiring urgent interventions.[8–10]

In the recent years, a large number of studies have been reported on times health identity of patients treated with concentrating and removable appliances.[11–23] However, the inference derived from these papers remains controversial. Therefore, clinicians can only rely on their clinical experience and the low-quality evidence reported in the literature when formulating treatment plans. Accordingly, considering the situation, we hypothesized that the periodontal status of patients treated with removable appliance was better than that of patients treated with fixed appliances, and employed a meta-analysis to confirm our hypothesis.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy

For this meta-analysis, articles were sourced from the databases of EMBASE, Cochrane library, Medline, PubMed, CNKI, and Wanfang without time or language restrictions. All relevant studies published through to December 2019 were included. In addition, we conducted manual retrieval in the research process, mainly using the research results in the references. Relevant studies were identified using the following key terms: “removable aligners”, “removable thermoplastic aligners”, “clear appliances”, “invisalign”, “periodontal index”, “periodontics”, and “periodontium”. Because this analyses was based on previously published studies, so there was no require for ethical approval and patient consent.

2.2. Inclusion criteria

This review included prospective cohort studies or randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared the periodontal status in patients treated with fixed appliances versus removable appliances. The subjects were patients diagnosed with malocclusion and who received orthodontic treatment for the same, who showed good oral health, no obvious periodontal disease, no systemic disease, no long-term history of taking antibiotics, among others. We focused on removable or fixed orthopedic appliances as the means of intervention.

2.3. Exclusion criteria

Case reports, review articles, and animal studies were excluded. Moreover, original articles whose reference literature could not be used after contact with the author were excluded.

2.4. Observation index

Plaque index (PLI), gingival index (GI), and the sulcus probing depth (SPD) were recorded in this study. The outcomes for the PLI, GI, and SPD at 3 and 6 months were assessed in this meta-analysis.

2.5. Data collection and analysis

Two investigators formed the data research object. In case of a conflict between the reports of the 2 investigators, further inspection of the measurements was made until finalization of the results. In case no agreement could be reached, a professional scholar was invited to resolve the issue. The data extracted from the references included the following: publication date, author name, country of the study, method of treatment, number of 2 methods, age, gender, patient recruitment time, the measurement period, and result measurements of different literatures.

2.6. Quality assessments

The quality of all research was assessed with reference to the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS). The research evaluation criteria were mainly divided into 3 aspects: measurement results, comparability, and queue selectivity. These aspects were further categorized into the number of stars, in a descending order, with grade A = 7–10 stars, grade B = 4–6 stars, and grade C = <3 stars.[24] During this process, in case of a conflict, negotiation was made to resolve the dispute. As per the description given in Table 1, all references in the meta-analysis belonged to grade A. Therefore, it can be concluded that this study involved the analysis of high-quality literature.

Table 1.

Quality evaluation of the included studies.

| Study | Queue selection | Comparability | Result measurement | Level of quality |

| Levrini 2013 | ★★★ | ★ | ★★★ | A |

| Miethke 2005 | ★★★★ | ★ | ★★★ | A |

| Azaripour 2015 | ★★★ | ★ | ★★★ | A |

| Eroglu AK 2019 | ★★★★ | ★ | ★★ | A |

| Zhou Q 2014 | ★★★ | ★ | ★★★ | A |

| Li YR 2017 | ★★★ | ★ | ★★★ | A |

| Li YZ 2015 | ★★★ | ★ | ★★★ | A |

| Huang GW 2015 | ★★★ | ★ | ★★★ | A |

| Chu KJ 2016 | ★★★★ | ★ | ★★★ | A |

| Zhou SL 2013 | ★★★ | ★ | ★★★ | A |

| Liu J 2017 | ★★★ | ★ | ★★★ | A |

| Li W 2017 | ★★★ | ★ | ★★★ | A |

| Sun MY 2018 | ★★★ | ★ | ★★★ | A |

2.7. Statistical analysis

The data from the individual studies were pooled and analyzed using the Stata 12.0 software (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas). I2 test and Chi-Squared-based test were applied to analyze the heterogeneity among the included articles. The range of heterogeneity was as follows: extreme = 75% to 100%; large = 50% to 75%; moderate = 25% to 50%; and low = < 25%. The fixed-effects model was generally used to evaluate the research content because I2 was <50%. A random effect model was used whenever the value was >50%. After obtaining the results of combined odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI), the Z test was employed for data analysis, with P < .05 considered as statistically significant. Any publication bias was assessed by using the Begg test and the Egger test. Sensitivity analysis was applied to analyze large heterogeneity studies and to find the source of heterogeneity.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of studies

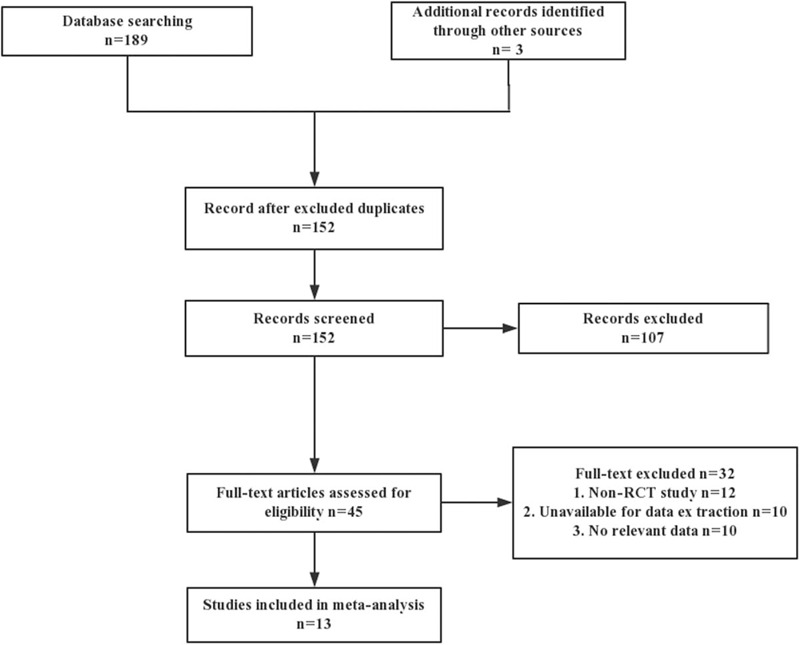

According to the above-mentioned retrieval methods, 192 relevant studies were selected for the analysis. After skimming the titles, abstracts, and reviewing the full-text content, 179 studies were excluded due to the lack of available data or the non-RCT nature of the study, among other reasons. Finally, 13 studies involving 598 patients met the inclusion criteria.[11–23] Among which, 297 patients were treated with removable appliances and 301 patients with fixed appliances. The flow diagram of the study selection procedure is presented in Fig. 1. The basic information of each included literature is shown in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Flow chart illustrating the study selection procedure.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the eligible studies in this meta-analysis.

| Removable appliances | Fixed appliances | |||||||

| Study | Female/male | Country | Time measures | Sample size | Average age | Sample size | Average age | Outcome measures |

| Levrini 2013 | 8/12 | Italy | 3 months | 10 | 25.1 ± 4.6 | 10 | 25.1 ± 4.6 | PLI, SPD, SBI |

| Miethke 2005 | 17/43 | Germany | 3 months | 30 | 30.1 | 30 | 30.1 | PLI, GI, SBI, SPD |

| Azaripour 2015 | 27/73 | Germany | 6 months | 50 | 31.9 ± 13.6 | 50 | 16.3 ± 6.9 | GI, SPI, SBI |

| Eroglu AK 2019 | 11/34 | Turkey | 3 months | 15 | 15.2 ± 2.1 | 15 | 15.2 ± 2.1 | PLI, GI, SBI, SPD |

| Zhou Q 2014 | 47/23 | China | 6 months | 40 | 28.4 | 40 | 24.6 | GI, PLI, SBI |

| Li YR 2017 | 12/28 | China | 6 months | 20 | 29.1 | 20 | 28.2 | PLI,GI, SPD |

| Li YZ 2015 | 30/16 | China | 6 months | 26 | 27.4 | 20 | 28.3 | PLI, SPD, SBI |

| Huang GW 2015 | 29/11 | China | 6 months | 20 | 26 | 20 | 26 | GI, PLI, SBI |

| Chu KJ 2016 | 17/13 | China | 6 months | 15 | 25.5 | 15 | 25.5 | GI, PLI, SPD |

| Zhou SL 2013 | 35/10 | China | 6 months | 20 | 25.1 | 25 | 26.3 | GI, PLI, SPD, SBI |

| Liu J 2017 | 9/13 | China | 6 months | 11 | NR | 11 | NR | PLI, GI, SPD |

| Li W 2017 | 15/45 | China | 6 months | 30 | 27.8 | 30 | 24.6 | GI, PLI, SBI, SPD |

| Sun MY 2018 | 5/15 | China | 6 months | 10 | 26.0 ± 5.6 | 10 | 24.0 ± 4.2 | GI, SBI, PLI, SPD |

GI = gingival index, NR = not report, PLI = plaque index, SBI = sulcus bleeding index, SPD = sulcus probing depth.

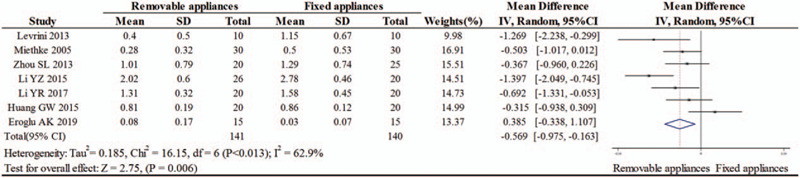

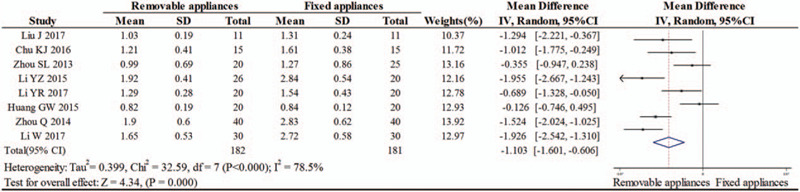

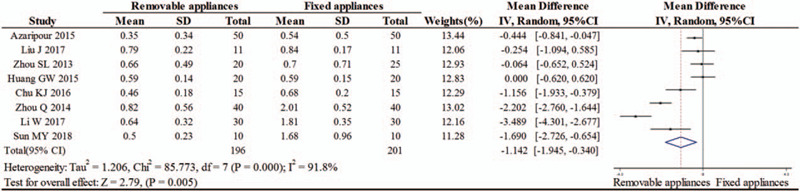

3.2. The status of PLI

Seven researches evaluated the PLI of 2 appliances after 3 months of treatment, and 8 researches evaluated the PLI of 2 appliances after 6 months of treatment. The heterogeneity test results were as follows: PPLI3 = .013, I2 = 62.9% and PPLI6 = .000, I2 = 78.5%, respectively. The results indicated an obvious statistical significance in PLI between the removable and fixed appliances groups at 3 months (OR = −0.57, 95% CI: −0.98 to −0.16, P = .006) and 6 months (OR = −1.10, 95% CI: −1.60 to −0.61, P = .000), as shown in Figs. 2 and 3.

Figure 2.

The status of PLI index at 3 months between the removable and fixed appliances groups.

Figure 3.

The status of PLI index at 6 months between the removable and fixed appliances groups.

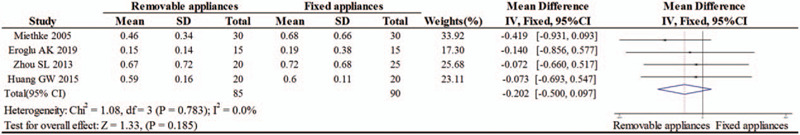

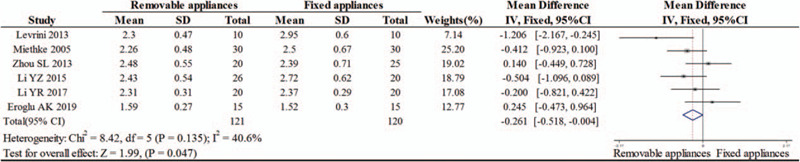

3.3. The status of GI

A total of 4 studies evaluated the GI of 2 appliances after 3 months of treatment, and 8 studies evaluated the GI of 2 appliances after 6 months of treatment. The results of heterogeneity test were as follows: PGI3 = .783, I2 = .0% and PGI6 = .000, I2 = 91.8%, respectively. These results demonstrated no statistical significance in GI between the removable and fixed appliances groups at 3 months (OR = −0.20, 95% CI: −0.50 to 0.10, P = .185). However, patients treated with removable appliances showed significantly lower GI status at 6 months (random effects model OR = −1.14, 95% CI: −1.95 to −0.34, P = .005), as shown in Figs. 4 and 5.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of meta-analysis of 2 appliances GI after 3 months of treatment.

Figure 5.

Forest plot of meta-analysis of the GI of 2 appliances after 6 months of treatment.

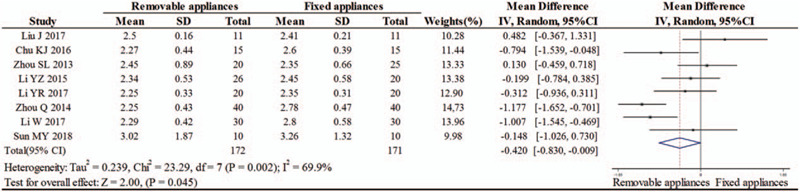

3.4. The status of SPD

Six researches evaluated the SPD of 2 appliances after 3 months of treatment, and 8 researches evaluated the SPD of 2 appliances after 6 months of treatment. The results of heterogeneity test were as follows: PSPD3 = .135, I2 = 40.6% and PSPD6 = .002, I2 = 69.9%, respectively. The significant difference in SPD between the removable and fixed appliances groups was detected at 3 months (OR = −0.26, 95% CI: −0.52 to −0.01, P = .047) and 6 months (OR = −0.42, 95% CI: −0.83 to −0.01, P = .045), as shown in Figs. 6 and 7.

Figure 6.

Forest plot of meta-analysis of SPD of 2 appliances after 3 months of treatment.

Figure 7.

Forest plot of meta-analysis of SPD of 2 appliances after 6 months of treatment.

3.5. Sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity analysis was conducted after removing each of the included articles one by one. However, the results demonstrated no significant change in the results of the combined effect, which implied that the result of the meta-analysis was stable.

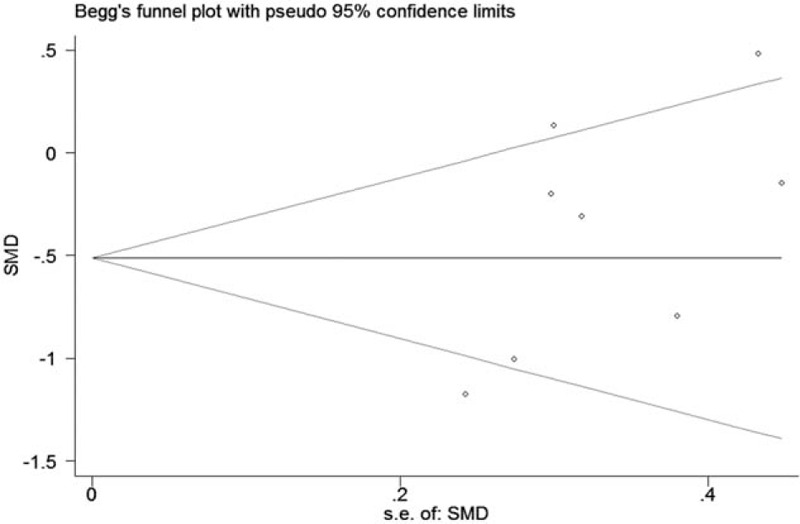

3.6. Publication bias

Begg test and Egger test were conducted to assess the publication bias (Fig. 8). Symmetry of the funnel plots implied no obvious publication bias (P = .174), and the results of Egger test also demonstrated no publication bias (P = .1).

Figure 8.

Begg's funnel plot for publication bias.

4. Discussion

The removable appliances appeared as creative orthopedic appliances in the late 1990 s.[25] The conventional orthodontic appliances were based on brackets and wires for orthodontic tooth movements. These are aesthetically pleasing, comfortable, simple, predictable, and portable devices. Because of the influence about times disease, Ristic et al[26] put forward the GI cell slowly upgrade at 4 weeks and 3 months when taking the concentrate tool, then reached its peak at 6 months. Meanwhile, some scholars have demonstrated the the progress of gravity could reach its highest value after 5 to 6 months of use.[23,26,27] From now on, gravity is regularly remained in the rank during the treatment period. Therefore, we partly researched the times situation in the first 6 months. Our results revealed that the GI, PLI, and SPD indexes were significantly reduced with removable orthotic devices as compared with that with conventional fixed orthotic devices (P < .05). These statistics thus signify that removable appliances are more beneficial for a healthy periodontal status.

The probable reasons supporting the superiority of removable appliances are as follows: patients with removable appliances can take the appliance out of their mouth and clean it. In addition, patients can remove the appliance at the time of cleaning their teeth, which is convenient. A removable appliance helps in better flossing and hence in maintaining better oral hygiene. Removable appliances covering most of the crown area can control the force exerted on that area. Removable appliances help make the teeth move closer as an overall movement while preventing the destruction of the periodontal tissues due to the migration of the supragingival plaque to the subgingival tissues.

Several studies have evaluated the influences of orthodontic appliances on the periodontal health. For instance, Miethke and Vogt[17] reported that, at the baseline level and at 3 distinguishing development time steps, patients arranged with fixed appliances were at significantly greater PLI risks than those arranged with removable appliances. However, they discovered no statistically significant difference in the SPD between the groups of patients treated with fixed appliances versus those fixed with removable appliances. Abbate et al[27] performed a similar initial orthodontic treatment on 50 adolescents aged 10 to 18 years and found that the adolescents wearing removable appliances had a higher periodontal status than adults using fixed appliances after the same treatment course. However, Alstad and Zachrisson[28] found no significant difference in the PLI or GI between these 2 treatment approaches. Despite the extensive use of fixed and removable appliances, there seems to be a lack of evidence supporting any specific appliance as being more beneficial for the periodontal health. Bollen et al[29] and Van et al[30] reviewed the literature and inferred that orthodontic measurement by itself does not upgrade the risk of periodontal pathologies. However, several studies have reported that the choice of oral hygiene procedures have a profound effect on the periodontal health of orthodontic patients.[31]

Notably, as per a recent observation, morbidity due to periodontitis increases with the age of the patient. Many adult patients realize the importance of dental health and begin to apply orthodontic treatment for straightening their teeth.[32] Orthodontic therapy may often lead to periodontal diseases, because the use of orthodontic appliances during the treatment may affect the oral hygiene procedures and lead to the accumulation of microbes in the mouth. However, some researchers argue that periodontal diseases are only partially related to orthodontic treatment. They state that orthodontic appliances can interfere with oral hygiene procedures to produce bacteria and induce their proliferation.[26,33–37] Some clinical and experimental trials have demonstrated that, despite maintaining good oral hygiene in patients, the use of orthodontic appliances can cause inflammation and lead to periodontal damage if the inflammation is not completely controlled, and that the attachment disappears with the accelerated development of periodontal damage.[38,39] Several previous studies have reported that fixed orthodontics serve as a greenhouse for plaque to build, which can lead to the development of inflammatory manifestations, such as gingival swelling or bleeding.[40–42] Currently, several studies have compared different orthodontic appliances with removable appliances and found the performance of removable appliances much superior. This is because removable appliances have been found to contribute significantly in building up oral hygiene by inhibiting the accumulation of dental plaque.[17,42,43] In terms of clinical presentation, the therapy of removable appliances is more secure for periodontium when compared with the therapy of fixed appliances.[44] Notably, removable appliances can help maintain the oral hygiene and thereby reduce the amount of plaque retentive surfaces. Considering these points, it can be concluded that removable appliances are a great orthodontic treatment appliance for patients with poor periodontal health.

However, some scholars believe that because patients must wore removable appliances for more than 20 hours a day, if patients failed to clean their mouth in time, food residue may stay in the gap between appliances and gingival mucosa, and prevent the self-cleaning of saliva in the patient's mouth. And because the appliance is an integrated appliance, covering the gingiva in a large area may caused gingival compression and injury, or some patients may not mastered the correct method to remove and wear the appliance during the correction period which may leaded to injury to the gingival tissue too. Therefore, they believe that the removable appliances is more harmful to the periodontal health of patients than the fixed appliances.[13,45] Thus, strong evidence is still needed to support our hypothesis.

This meta-analysis has some limitations. First, the available research data were limited to those from China, Germany, and Italy only, and hence the conclusion may not be applicable to other countries. Second, without analyzing a large number of studies, it is difficult to conduct a comprehensive and detailed study, and some studies with a small sample size could not provide sufficient statistical power to identify the actual association. Third, the index measurements of the position and the quantity of teeth were coincidental. Some study assessed the full mouth teeth, while others measured only certain teeth, which may have resulted in a bias during the implementation. Moreover, the types of malocclusion included were not corresponding, which may have enhanced the presence of confounding factors.

5. Conclusion

This meta-analysis demonstrated that the periodontal status of patients treated with removable appliance was much superior to that with the conventional fixed appliances. Owing to the limitation in terms of both quality and quantity of the involved studies, we suggest that the inference of this review be verified further using more number of RCTs.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Yuan Wu, Lei Cao, Jingke Cong.

Data curation: Yuan Wu, Lei Cao, Jingke Cong.

Formal analysis: Yuan Wu, Lei Cao, Jingke Cong.

Funding acquisition: Yuan Wu, Lei Cao, Jingke Cong.

Investigation: Yuan Wu, Lei Cao, Jingke Cong.

Methodology: Yuan Wu, Lei Cao, Jingke Cong.

Project administration: Yuan Wu, Lei Cao, Jingke Cong.

Resources: Yuan Wu, Lei Cao, Jingke Cong.

Software: Yuan Wu, Lei Cao, Jingke Cong.

Supervision: Yuan Wu, Lei Cao, Jingke Cong.

Validation: Yuan Wu, Lei Cao, Jingke Cong.

Visualization: Yuan Wu, Lei Cao, Jingke Cong.

Writing – original draft: Yuan Wu, Lei Cao, Jingke Cong.

Writing – review & editing: Yuan Wu, Lei Cao, Jingke Cong.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: 95% CI = 95% confidence interval, GI = gingival index, NOS = Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, OR = odds ratio, PLI = plaque index, RCT = randomized controlled trial, SBI = sulcus bleeding index, SPD = sulcus probing depth.

How to cite this article: Wu Y, Cao L, Cong J. The periodontal status of removable appliances vs fixed appliances: a comparative meta-analysis. Medicine. 2020;99:50(e23165).

This work was supported by Qingdao Key Health Discipline Development Fund (2020–2022).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- [1].Kesling HD. Coordinating the predetermined pattern and tooth positioner with conventional treatment. Am J Orthod Oral Surg 1946;32:285–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Liu H, Sun J, Dong Y, et al. Periodontal health and relative quantity of subgingival Porphyromonas gingivalis during orthodontic treatment. Angle Orthod 2011;81:609–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Khosravi R, Cohanim B, Hujoel P, et al. Management of overbite with the Invisalign appliance. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 2017;151:691–9 e692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Frongia G, Castroflorio T. Correction of severe tooth rotations using clear aligners: a case report. Aust Orthod J 2012;28:245–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bräscher AK, Zuran D, Feldmann RE, et al. Patient survey on Invisalign (®) treatment comparen the SmartTrack(®) material to the previous aligner material. J Orofac Orthop 2016;77:1–7.26753550 [Google Scholar]

- [6].Gomes SC, Varela CC, Da VS, et al. Periodontal conditions in subjects following orthodontic therapy. A preliminary study. Eur J Orthod 2007;29:477–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Socransky SS, Haffajee AD. The bacterial etiology of destructive periodontal disease: current concepts. J Periodontol 1992;63:322–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Petti S, Barbato E, Simonetti DAA. Effect of orthodontic therapy with fixed and removable appliances on oral microbiota: a six-month longitudinal study. New Microbiol 1997;20:55–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Friedman M, Harari D, Raz H, et al. Plaque inhibition by sustained release of chlorhexidine from removable appliances. J Dent Res 1985;64:1319–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Pender N. Aspects of oral health in orthodontic patients. Br J Orthod 1986;13:95–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zhou Q, Wang H. Comparative study on the effect of fixed appliances and removable aligners. Stomatology 2014;34:784–6. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Li YZ, Tan JL. Effects on periodontal health in the use of the invisalign and fixed appliance: a longitudinal comparative study in clinic. J Clin Stomatol 2015;DOI: 1010.3969/j.issn.1003-1634.2015.08.013. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Huang GW, Li J. Influence of invisalign system and fixed appliance oil periodontal health. Chin J Orthod 2015;22:32–4. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Chu KJ, Wang HH, Zhen ZJ, et al. Changes of AST and ALP in gingival crevicular fluid during orthodontic treatment with invisible aligner. J Oral Sci Res 2016;32:399–401. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Levrini L, Mangano A, Montanari P, et al. Periodontal health status in patients treated with the Invisalign(®) system and fixed orthodontic appliances: a 3 months clinical and microbiological evaluation. Eur J Dent 2015;9:404–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Zhou SL, Guo J. A comparison of the periodontal health of patients during treatment with the invisalign system and with fixed orthodontic appliance. Int J Oral Sci 2013;66:172–5. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Miethke RR, Vogt S. A comparison of the periodontal health of patients during treatment with the Invisalign system and with fixed orthodontic appliances. J Orofac Orthop 2005;66:219–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Azaripour A, Weusmann J, Mahmoodi B, et al. Braces versus Invisalign R: gingival parameters and patients’ satisfaction during treatment: a cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 2015;15:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Eroglu AK, Baka ZM, Arslan U, et al. Comparative evaluation of salivary microbial levels and periodontal status of patients wearing fixed and removable orthodontic retainers. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2019;156:186–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Li YR, Yuan JJ, Li JQ, et al. Comparison of the effects of two kinds of aesthetic appliances on periodontal health of adult orthodontic patients. Henan Med Res 2015;26:1757–9. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Liu J. A comparative study on the effects of non-bracket invisible orthodontic technique and traditional fixed orthodontic technique on periodontal health of patients. World Clin Med 2017;11:161–4. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Li W, Huang YT. Comparison of periodontal health of patients treated by the invisalign system with those treated by fixed orthodontic appliance. J Pract Stomatol 2017;33:270–2. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Sun MY, Huang QB, Wang KH, et al. Impact of invisalign and fixed appliance on the periodontal health of orthodontic patients. Stomatology 2018;38:149–53. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of non-randomized studies in meta-analysis. Appl Eng Agric 2014;18:727–34. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Boyd RL, Waskalic V. Three-dimensional diagnosis andorthodontic treatment of complex malocclusions with the invisalign appliance. Seminars Orthodontics 2001;7:274–93. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ristic M, Vlahovic SM, Sasic M, et al. Clinical and microbiological effects of fixed orthodontic appliances on periodontal tissues in adolescents. Orthod Craniofac Res 2007;10:187–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Abbate GM, Caria MP, Montanari P, et al. Periodontal health in teenagers treated with removable aligners and fixed orthodontic appliances. J Orofac Orthop 2015;76:240–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Alstad S, Zachrisson BU. Longitudinal study of periodontal condition associated with orthodontic treatment in adolescents. Am J Orthod 1979;76:277–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Bollen AM, Cunha-Cruz J, Bakko DW, et al. The effects of orthodontic therapy on periodontal health: a systematic review of controlled evidence. J Am Dent Assoc 2008;139:413–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Van GJ, Quirynen M, Teughels W, et al. The relationships between malocclusion, fixed orthodontic appliances and periodontal disease. A review of the literature. Aust Orthod J 2007;23:121–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Talic NF. Adverse effects of orthodontic treatment: a clinical perspective. Saudi Dent J 2011;23:55–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Gkantidis N, Christou P, Topouzelis N. The orthodontic-periodontic interrelationship in integrated treatment challenges: a systematic review. J Oral Rehabil 2010;37:377–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Alexander SA. Effects of orthodontic attachments on the gingival health of permanent second molars. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1991;100:337–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Paolantonio M, Festa F, Di PG, et al. Site-specific subgingival colonization by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in orthodontic patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1999;115:423–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Sallum EJ, Nouer DF, Klein MI, et al. Clinical and microbiologic changes after removal of orthodontic appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2004;126:363–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Türkkahraman H, Sayin MO, Bozkurt FY, et al. Archwire ligation techniques, microbial colonization, and periodontal status in orthodontically treated patients. Angle Orthod 2005;75:231–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Gastel JV, Quirynen M, Teughels W, et al. Longitudinal changes in microbiology and clinical periodontal parameters after removal of fixed orthodontic appliances. Eur J Orthod 2011;33:15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Årtun J, Urbye KS. The effect of orthodontic treatment on periodontal bone support in patients with advanced loss of marginal periodontium. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1988;93:143–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Wennström JL, Stokland BL, Nyman S, et al. Periodontal tissue response to orthodontic movement of teeth with infrabony pockets. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1993;103:313–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Krishnan V, Ambili R, Davidovitch ZE, et al. Gingiva and orthodontic treatment. Semin Orthod 2007;13:257–71. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Cantekin K, Celikoglu M, Karadas M, et al. Effects of orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances on oral health status: a comprehensive study. J Dent Sci 2011;6:235–8. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Clerehugh V, Williams P, Shaw WC, et al. A practice-based randomised controlled trial of the efficacy of an electric and a manual toothbrush on gingival health in patients with fixed orthodontic appliances. J Dent 1998;26:633–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Marzieh K, Denise C, Jennifer S, et al. Periodontal status of adult patients treated with fixed buccal appliances and removable aligners over one year of active orthodontic therapy. Angle Orthod 2013;83:146–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Rossini G, Parrini S, Castroflorio T, et al. Periodontal health during clear aligners treatment: a systematic review. Eur J Orthod 2015;37:539–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Birdsall J, Robinson S. A case of severe caries and demineralisation in a patient wearing an essix-type retainer. Prim Dent Care 2008;15:59–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]