Abstract

We describe a neonate with severe respiratory failure due to acinar dysplasia found by rapid exome sequencing, to have a deletion containing the TBX4 gene. Rapid exome sequencing can affect patient management in the ICU and should be considered in concert with lung biopsy in neonates with undifferentiated respiratory failure.

INTRODUCTION:

The differential diagnosis for neonates with respiratory failure is broad and includes pathologies with different management options and prognoses. Infants with reversible, treatable hypoxic respiratory failure can have identical presentations to those with irreversible and lethal respiratory failure, including primary disorders of lung development such as acinar dysplasia (AD). Expedient diagnosis of lethal genetic causes of pulmonary failure can provide diagnostic certainty for the medical team and families that is essential when planning goals of care.

The diagnosis of disorders of lung development has traditionally rested on lung biopsy, and this remains the gold standard. However, advances in DNA sequencing over the past 5 years have led to increasing understanding of the genetics of these disorders. Exome sequencing, which is a method for examining the majority of all ~20,000 protein-coding genes within the human genome at once, has revolutionized clinical diagnosis of pediatric rare disorders[1 2]. Until recently, exome sequencing, with a turnaround time (TAT) of several months, has not been able to provide information with the speed required in the NICU. Now, several clinical laboratories offer rapid exome sequencing (rES), with TAT as short as one week. This is increasingly becoming a critical tool in management of critically ill neonates[3 4].

Here we describe an infant with cardiopulmonary collapse necessitating veno-arterial extra-corporeal life support (VA ECLS) who was diagnosed with acinar dysplasia via lung biopsy. This diagnosis was supported by rapid exome sequencing, which identified a deletion involving the TBX4 gene- a gene that has been implicated in AD. These results supported the family and medical teams decision to redirect goals of care. In addition to providing a description of an infant with AD and a deletion of TBX4, this report supports the increasing use of rES, in concert with lung biopsy, in neonates with undifferentiated respiratory failure.

CASE REPORT:

A preterm male infant was born via emergency cesarean section at 33 6/7 weeks to a 40 year old G3P2 mother after presentation for decreased fetal movement with recurrent fetal heart rate decelerations. The prenatal course was notable for intrauterine growth restriction and maternal history of thrombophilia and treated thyroid cancer; medications included enoxaparin, levothyroxine and calcitriol. Cell free fetal DNA testing was reported as low risk.

The infant was depressed at birth with Apgars of 5, 5 and 8 at 1, 5 and 10 min, respectively. He was intubated shortly after birth and given surfactant. Initial venous blood gas showed a pH of 7.25, PCO2 59, base deficit of 3. His birth weight was the 13th percentile, birth height 57th percentile, and birth head circumference at the 6th percentile. His initial exam was notable for dysmorphic features including bilateral clenched fists, mild low-set, posteriorly rotated ears with underdeveloped helices, widely spaced and underdeveloped nipples, broad first toes, hypoplastic toenails, and bilateral 2nd toe clinodactyly. He had persistent, worsening hypoxia with pre and post-ductal saturation discrepancy consistent with pulmonary hypertension for which he was escalated to high frequency oscillator support and inhaled nitric oxide. Chest tubes were placed for bilateral pneumothoraces. He became hypotensive requiring fluid boluses, hydrocortisone and pressor support. Antibiotics and acyclovir were initiated following collection of blood cultures. He was transferred to a level IV NICU for ECLS (ExtraCorporeal Life Support) evaluation.

Initial echocardiogram revealed normal anatomy with moderately dilated and hypertrophied right ventricle, moderate pulmonary hypertension (estimated right ventricular pressure 24 mmHg above right atrial pressure) and good left ventricular function. Cranial ultrasound was normal. He was cannulated onto veno-arterial ECLS for persistent hypoxic respiratory failure.

His overall ECLS course was unremarkable with resolution of air leak, minimal pressor needs and requirement of only moderate ventilator support. However, he failed trial off ECLS repeatedly due to hypoxia. A cord-blood based karyotype was normal (46 XY). Rapid trio exome sequencing was sent on day of life 4. On day of life 8 a diagnostic lung biopsy showed marked arrest in lung maturation consistent with the spectrum of acinar dysplasia (Figure 1). Exome sequencing results showed a de novo deletion of at least 2.06 Mb extending from 17q23.2 to 17q23.2 (chr17: 59290909_61353248×1 in hg19 coordinates), involving 14 genes including TBX4 (Table 1). This large deletion has not been identified in large databases of normal controls, and was interpreted as being pathogenic. Following discussions with lung transplant centers, he was determined not to be a candidate for transplantation due to small size, gestational age and severity of illness. Given irreversible pathology, following discussions with family, he was compassionately extubated and passed away on day of life 10.

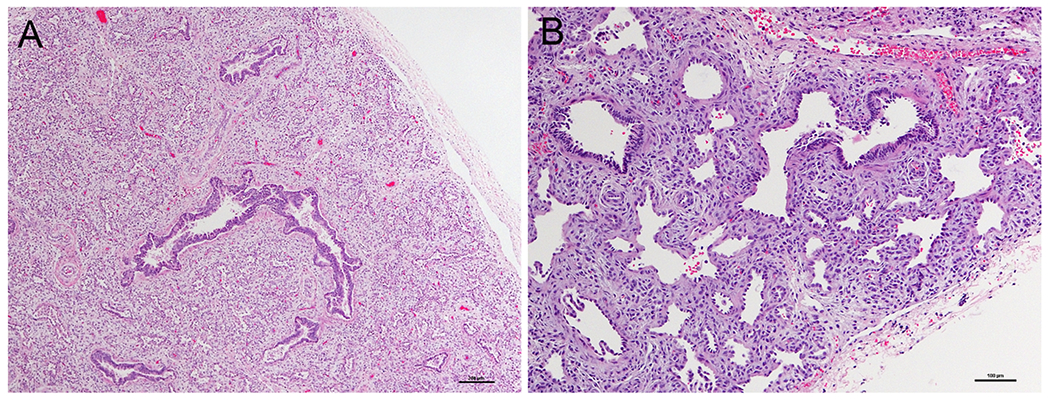

Figure 1: Lung histopathology of patient with acinar dysplasia.

A) Lung from the infant’s autopsy, showing an immature appearance for gestational age with no saccular structures or alveoli. B) Higher power demonstrating abnormal alcinar structures with abundant intervening mesenchyme (Hematoxylin and eosin).

Table 1:

Genes within deletion interval (Chr17: 59290909-61353248)

| Gene Symbol | Gene Name | Disease Association (OMIM phenotype number) |

|---|---|---|

| BCAS3 | Breast carcinoma amplified sequence 3 | None |

| TBX2 | T-box 2 | None |

| C17orf82 | Chromosome 17 open reading frame 82 | None |

| TBX4 | T-box 4 | Short Patella Syndrome (#147891), Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension |

| NACA2 | Nascent polypeptide-associated complex alpha subunit 2 | None |

| BRIP1 | BRCA1 interacting protein C-terminal helicase 1 | Breast cancer, early onset (#114480), Fanconi anemia complementation group J (#609054) |

| INTS2 | Integrator complex subunit 2 | None |

| MED13 | Mediator complex subunit 13 | None |

| EFCAB3 | EF-hand calcium binding domain 3 | None |

| METTL2A | Methyltransferase like 2A | None |

| TLK2 | Tousled-like kinase 2 | Mental retardation, autosomal dominant 57 (#618050) |

| MRC2 | Mannose receptor, C type 2 | None |

| MARCH10 | Membrane-associated ring-CH finger protein 10 | None |

| TANC2 | Tetratricopeptide repeat, ankyrin repeat and coiled-coil containing 2 | None |

Coordinates are hg19-based. Note that this is the minimally deleted interval. The exact breakpoints are unknown.

A complete autopsy was performed and identified arrested lung development at the canalicular stage, consistent with acinar dysplasia. Other post-mortem findings noted include hepatosplenomegaly, patent ductus arteriosus and right ventricular hypertrophy, mild central nervous system gliosis, stress involution of the thymus and hepatic canalicular cholestasis due to hyperalimentation. No other major congenital anomalies were noted. No abnormalities were noted on post-mortem skeletal survey.

DISCUSSION:

Acinar dysplasia (AD) is a diffuse developmental disorder of the lung whereby lung maturation is arrested in the pseudoglandular to canalicular stage of development[5–9]. As with this patient, mature alveolar structures are absent and septae are thickened, limiting gas exchange. AD demonstrates more severe developmental arrest than that seen in the disorder congenital alveolar dysplasia (CAD), although a spectrum of histologic maturation may exist within the same lung (Chow et al). Newborns with lung maldevelopment along the spectrum of acinar and congenital alveolar dysplasia classically present with early respiratory failure requiring maximum support. With rare exceptions these disorders are fatal within the neonatal period [10].

TBX4 belongs to the T-box family of transcription factors, which govern multiple processes in early embryonic development[11–13]. Tbx4 is expressed in early lung mesenchyme as well as the limbs (primarily hindlimb), mandible, heart and body wall [12]. Mouse models demonstrate an important role for Tbx4 and Tbx5 in lung branching [14 15]. TBX4 mutations are reported in small patella syndrome (SPS, aka ischiocoxopodopatellar syndrome), an autosomal dominant skeletal dysplasia characterized by patellar aplasia or hypoplasia and by anomalies of the pelvis and feet [16]. Mutations in TBX4 have also been reported in childhood-onset pulmonary artery hypertension (PAH) [17]. Interestingly, close examination of pelvic x-rays and feet of all 6 individuals in this study who had childhood onset PAH and TBX4 mutations identified features of SPS [17]. Thus, it is likely that loss of function of TBX4 contributes to both abnormalities of lung and skeletal development, and individuals with SPS may be at risk of developing PAH. Since the skeletal features of SPS are not detectable prior to ossification of the patella and ischiopubic junction, we cannot rule out the possibility that our patient might also have developed signs of this skeletal dysplasia. It is possible that the hypoplastic toenails seen in our patient could represent the mildest manifestation of a lower limb skeletal dysplasia, although hypoplastic toenails are relatively common and have not been reported in SPS, so this remains speculation.

Together, our patient’s results with the previous reports suggests that the loss of function of TBX4 in our patient is the primary etiology of his lung dysplasia, although we cannot rule out a role for the other 13 genes within the deletion, particularly TBX2 which is also within this interval (Table 1). However, supporting a more primary role for TBX4 is a very recent report [18], that identified a de novo TBX4 missense mutation (NM_018488.2:c.256G>C, pGlu86Gln) in a deceased newborn with acinar dysplasia, very similar to the infant we present here. This infant died on day of life 1, so again SPS could not be excluded. We can offer no molecular explanation, at the present, for why some patients with TBX4 mutations develop a mild skeletal dysplasia (SPS), some develop SPS with childhood-onset PAH, and some develop neonatal lethal acinar dysplasia.

In this case, lung biopsy and whole exome sequencing worked synergistically to provide a definitive diagnosis. Knowledge of the irreversible nature of this disease allowed the family to feel confident in their decision to redirect support, and provided the family with the psychological benefit of knowing the cause of their child’s lung disease. This information also allowed for accurate recurrence risk counseling, and decreased the number of days this child was in the intensive care unit receiving ECLS Conservatively assuming that this infant would have remained on ECLS for at least 5 more days, and a cost per hospital day of ECLS of $15,000, [19] we estimate this diagnosis saved approximately $46,000. This estimate is based on costs of rES ($10,000) and the surgical lung biopsy (~$19,000) [20]. We believe that rapid genetic diagnosis should be considered in all children with severe, unexplained respiratory failure requiring ECLS, particularly when there is at least one other congenital anomaly.

CONCLUSIONS:

Irreversible lung pathology, such as acinar dysplasia, should be considered in patients with persistent, severe hypoxic respiratory failure and dysmorphology. Early diagnosis of irreversible disease via lung biopsy and/or rapid exome sequencing can provide a definitive diagnosis and lead to major changes in medical management in the ICU. We believe rapid exome sequencing is currently underutilized in the NICU and will decrease overall medical costs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

ASF was supported by postdoctoral training grant 5T32GM007454 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health

Funding Sources: ASF was supported by postdoctoral training grant 5T32GM007454 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, otherwise no funding was provided

Footnotes

Disclosures: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Bamshad MJ, Ng SB, Bigham AW, et al. Exome sequencing as a tool for Mendelian disease gene discovery. Nat Rev Genet 2011;12(11):745–55 doi: 10.1038/nrg3031[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chong JX, Buckingham KJ, Jhangiani SN, et al. The Genetic Basis of Mendelian Phenotypes: Discoveries, Challenges, and Opportunities. Am J Hum Genet 2015;97(2):199–215 doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.06.009[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stark Z, Lunke S, Brett GR, et al. Meeting the challenges of implementing rapid genomic testing in acute pediatric care. Genet Med 2018. doi: 10.1038/gim.2018.37[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stark Z, Schofield D, Martyn M, et al. Does genomic sequencing early in the diagnostic trajectory make a difference? A follow-up study of clinical outcomes and cost-effectiveness. Genet Med 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0006-8[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chambers HM. Congenital acinar aplasia: an extreme form of pulmonary maldevelopment. Pathology 1991;23(1):69–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deutsch GH, Young LR, Deterding RR, et al. Diffuse lung disease in young children: application of a novel classification scheme. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176(11):1120–8 doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-393OC[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Langenstroer M, Carlan SJ, Fanaian N, et al. Congenital acinar dysplasia: report of a case and review of literature. AJP Rep 2013;3(1):9–12 doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1329126[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nogee LM. Interstitial lung disease in newborns. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2017;22(4):227–33 doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2017.03.003[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rutledge JC, Jensen P. Acinar dysplasia: a new form of pulmonary maldevelopment. Hum Pathol 1986;17(12):1290–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chow CW, Massie J, Ng J, et al. Acinar dysplasia of the lungs: variation in the extent of involvement and clinical features. Pathology 2013;45(1):38–43 doi: 10.1097/PAT.0b013e32835b3a9d[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bertolessi M, Linta L, Seufferlein T, et al. A Fresh Look on T-Box Factor Action in Early Embryogenesis (T-Box Factors in Early Development). Stem Cells Dev 2015;24(16):1833–51 doi: 10.1089/scd.2015.0102[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghosh TK, Brook JD, Wilsdon A. T-Box Genes in Human Development and Disease. Curr Top Dev Biol 2017;122:383–415 doi: 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2016.08.006[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jain D, Nemec S, Luxey M, et al. Regulatory integration of Hox factor activity with T-box factors in limb development. Development 2018;145(6) doi: 10.1242/dev.159830[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arora R, Metzger RJ, Papaioannou VE. Multiple roles and interactions of Tbx4 and Tbx5 in development of the respiratory system. PLoS Genet 2012;8(8):e1002866 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002866[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cebra-Thomas JA, Bromer J, Gardner R, et al. T-box gene products are required for mesenchymal induction of epithelial branching in the embryonic mouse lung. Dev Dyn 2003;226(1):82–90 doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10208[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vanlerberghe C, Jourdain AS, Dieux A, et al. Small patella syndrome: New clinical and molecular insights into a consistent phenotype. Clin Genet 2017;92(6):676–78 doi: 10.1111/cge.13103[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kerstjens-Frederikse WS, Bongers EM, Roofthooft MT, et al. TBX4 mutations (small patella syndrome) are associated with childhood-onset pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Med Genet 2013;50(8):500–6 doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101152[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szafranski P, Coban-Akdemir ZH, Rupps R, et al. Phenotypic expansion of TBX4 mutations to include acinar dysplasia of the lungs. Am J Med Genet A 2016;170(9):2440–4 doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37822[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhatt P, Lekshminarayanan A, Donda K, et al. National trends in neonatal extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in the United States. J Perinatol 2018;38(8):1106–13 doi: 10.1038/s41372-018-0129-4[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lokhandwala T, Bittoni MA, Dann RA, et al. Costs of Diagnostic Assessment for Lung Cancer: A Medicare Claims Analysis. Clin Lung Cancer 2017;18(1):e27–e34 doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2016.07.006[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]