ABSTRACT

Our study analyzed the economicimpact of a telegeriatrics programme on care of nursing homeresidents, from the healthcare system provider’s perspective. Thisis a retrospective, archival data analysis of multiple data sourcesin 4 nursing homes of Singapore from 2010 to 2015. Individualsadmitted to nursing homes and have undergone telemedicineconsultations (N=859) from 2010 to 2015 were recruited. Weconducted a cost analysis of the programme by reviewing pasthospital admissions’ and specialist outpatient clinic (SOC) visits’billing records, nurse training records, and key performanceindicators’ reports. A significant relationship was observed betweenteleconsultations and SOC visit cost (β1 = -83.366, p-value<0.01) and between teleconsultations and inpatient cost (β1 =-470.971, p-value <0.05). Remote video consultations could reduceunnecessary SOC visits and hospital admissions, and thereforelead to cost savings. Training of nursing home nurses couldtranslate to cost savings as a result of decreased ED transfers.

KEYWORDS: Telehealth, health IT quality and evaluation, health IT economics

1. Introduction

The world’s population is rapidly ageing (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2015, p. 1–164). Some of the fastest ageing societies are located in the Asia Pacific region and Singapore stands at the forefront of this unprecedented demographic change (Population SG, 2016). An ageing population exerts a heavy burden on the healthcare services of a country through increased utilisation and consumption of limited and finite resources. The cost of healthcare and the proportion of the GDP spent on healthcare are increasing at an alarming rate (World Health Organization, 2012). Acute hospitals in Singapore are experiencing high bed occupancy rates in the region of 80–90%, and increased patient workloads at the Emergency Departments (The Straits Times, 2017). A significant proportion of hospital admissions originates from long term care facilities such as nursing homes and assisted living facilities (Asiaone, 2012). There is an urgent need to improve on the efficiency and productivity of healthcare services for the older person. Several studies have been conducted to look at the cost-effectiveness of applying information technology in healthcare, including the use of telemedicine (Dixon et al., 2016; Henderson et al., 2013; Richter et al., 2015).

When telemedicine was first introduced about 20 years ago, main barriers were high cost, technical issues, and low acceptance (Binstock & Spector, 1997; Lyketsos, Roques, Hovanec, & Jones, 2001; Thrall & Boland, 1998). Over time, potential benefits for telemedicine were more extensively studied, especially in its promise to avert unnecessary hospitalisation. Reduction in unnecessary hospitalisations could lead to cost savings and increased quality of life in nursing home residents. A systematic review conducted to identify studies reporting cost-effectiveness of telemedicine interventions over 20 years found limited evidence of telemedicine being a cost-effective mode of delivering healthcare compared to conventional care (Mistry, 2012). However, this conclusion was derived from economic evaluations based on mostly small-scale studies that were monitored for a short period of less than 2 years. Moreover, the studies assumed equivalent outcomes without providing any substantial scientific evidence.

Use of videoconferencing in nursing homes is not new. A recent review conducted on clinical use of videoconferencing in nursing homes found that the videoconferencing was more commonly used for clinical assessments than for management and diagnosis (Hofmeyer et al., 2016). The frequently reported outcome was staff acceptability, and few sought to look into patient outcomes or feasibility of videoconferencing in terms of cost. Where acceptability was concerned, nursing home providers indicated high potential in telemedicine to improve timeliness of care and fill existing service gaps, to reduce unnecessary hospitalisations, and avoidance of travel for patient and provider (Driessen et al., 2016). In a scoping review of telemedicine in nursing homes, most studies were found to be conducted in countries with large, sparsely populated areas, where remoteness and increased travel time make conventional services more difficult to provide. The review identified limited generalisability to other countries and a need for better understanding of how telemedicine for older adults would work in other contexts (Newbould, Mountain, Hawley, & Ariss, 2017). Research is needed to examine cost of using telemedicine in nursing homes of a small, densely-populated country, Singapore.

1.1. Gericare@North

The Geriatrics Department of a 500-bedded district general hospital located in Singapore, piloted a programme (GeriCare@North) which partnered nursing homes. The programme’s goal was to reduce hospital transfers and therefore hospital utilisation rates among the residents of nursing homes. Concomitantly, this programme sought to create an integrated and coordinated ecosystem to enhance quality of care in these nursing homes in a cost-effective manner. A videoconferencing system (telegeriatrics) was used to conduct teleconsultations, multidisciplinary team meetings, mortality audits and continuous nursing education with the staff of the participating nursing homes. Structured protocols, guidelines and pathways were developed by the programme team to conduct these activities and as part of the implementation strategy, a 6-month intensive Telegeriatrics Nurse Training Course (TNTC) was conducted to train and upskill the nurses who were to take on the role of remote physician assistants to the doctor working from the acute hospital.

On average, the participating nursing homes lodged 200 residents who were cared for by 15–17 registered nurses and 30–40 nursing aides. These nursing homes were run independently by voluntary welfare organisations and religious groups. As such they lacked adequate medical expertise and nursing resources and were highly dependent on acute hospitals for geriatric care. This lack of convenient, timely and cost-effective access to geriatric care often resulted in unnecessary hospital transfers and admissions. There was a perceived gap in this area of healthcare that could worsen as the population continued to age, which could however be potentially ameliorated with the adoption of technology.

1.2. Telemedicine equipment

The telegeriatrics system incorporated a hub and spoke model implemented across four nursing homes in Singapore. Telemedicine consultations were conducted using Polycom videoconferencing set. A high-resolution camera and high-definition video monitor were installed in the acute hospital and each nursing home. Both sites used encrypted high-speed internet.

1.3. Telemedicine consultations

Telemedicine consultations lasted about 20 min on average. In a telemedicine consultation, a trained nurse describes the presenting symptom(s) while the geriatrician identifies the root cause of the problem and prescribes the appropriate treatment. The consultation is documented in a form. This form is used to document elements of the resident’s visit such as the name of consulting geriatrician, any assessments completed by the nurse and any information received from other healthcare facilities. After consultation, the form and other relevant documents such as prescriptions are emailed to the nursing home for the nurses to follow up with the management plan.

This paper reports a cost analysis of the programme from the healthcare system provider’s perspective. This is the first ever report that looks at cost analysis of a telemedicine programme in the long-term care setting in Singapore.

2. Methods

A panel data set was constructed by collecting archival data from multiple sources from June 2010 to December 2015 for the four nursing homes. The unit of analysis for the study was each nursing home on a per month basis. Hence, for each month, we collated data on each nursing home’s telegeriatrics use and its incurred costs.

2.1. Independent and control variables

A critical independent variable is the number of patients seen via telegeriatrics per month. This was collected from the monthly key performance indicator (KPI) reports prepared by the operations personnel from the acute hospital. These operations personnel visited the nursing homes each month to collect and compile the KPI data. The operations personnel then submitted the KPI reports to MOHS on a quarterly basis. As each nursing home entered the GeriCare@North at different time points, a month variable was added as a control for the duration of the telegeriatric system’s use.

The other main independent variable is the percentage of nursing staff trained each month per nursing home, as the TNTC was necessary for the effective conduct of the teleconsultations. The acute hospital kept a record of the nurses who attended and completed the training program. The number of nursing staff trained and the total number of nursing staff in each nursing homes were obtained from the nurse training records of the acute hospital to calculate the percentage of trained staff in each nursing home per month.

We also collected data on control variables such as the number of residents, total staff and beds from the published annual reports of each nursing home. Furthermore, we obtained data on unplanned hospital admissions, general physician (GP) physical visits and residents seen during the physical visits from the KPI reports provided by the acute hospital.

2.2. Cost variables

The impact of teleconsultations was measured on three cost variables: specialist outpatient costs, inpatient costs and ED costs. The operations team at the acute hospital downloaded all nursing home patient bills from the central billing system to calculate the specialist outpatient cost. Specifically, from these nursing home patient bills (each nursing home per month), we categorised the visits where patients were admitted and discharged on the same day as specialist outpatient clinic (SOC) visits. Given that a large number of the patients were subsidised by the government, actual billed amounts accrued by outpatient visits were not taken as direct measure of specialist outpatient cost as they do not reflect the full cost for the provision of outpatient medical services. Instead the operations team at the acute hospital calculated an estimated net cost of $286 for each SOC visit. This estimate was based on the costs of providing the following: a nursing aide to accompany the patient for the duration of a return trip to the hospital (estimated to be 5 h), ambulance transport, an SOC nurse to attend to the patient’s needs, the actual consultation with the geriatrician (estimated to be 30 min) and clerical staff required to attend to administrative matters at the SOC. These estimates were concordant with the estimation of MOHS and a project study by the Imperial College of London, whose findings were presented at an International Symposium on Health Care Policy 2016 (Commonwealth Fund, 2015). The total specialist outpatient cost was then calculated by multiplying the number of SOC visits by the estimated cost per visit ($286).

For inpatient cost, we obtained the data on the number of unplanned admissions per month and average length of stay per admission for each nursing home from the KPI reports. The total inpatient days were calculated by multiplying the number of unplanned admissions and average length of stay per admission. For cost per inpatient day, we referred to MOHS website calculation – it estimated that the cost for an uncomplicated patient condition admitted in an acute hospital to be $503 per inpatient day (Commonwealth Fund, 2015). Although the cost of an inpatient stay depends on whether the condition is complicated by other comorbidities and severity of the illness, we used this conservative estimated cost of $503 as the minimum cost per inpatient day at an acute hospital. The total inpatient cost was then calculated by multiplying the total inpatient days by this estimated cost of per inpatient day ($503).

To calculate the costs incurred at the emergency department, we took the number of visits to the ED (extracted from the KPI reports) and multiplied that by the cost incurred for each visit. Each ED visit on average lasts 6 h and the estimated cost amounted to $182 per hour. The operations team arrived at this figure by taking into account the cost and time of nurses and doctors involved in managing a patient in the ED during each visit. This estimate concurred with the same Imperial College study. The total emergency department cost was therefore calculated by multiplying the number of visits with average duration (6 h) and the cost per hour ($182).

We established baseline data for all variables by collecting data six-month prior to the use of telegeriatrics for each nursing home. The month variable was coded as 0 for all months before telegeriatrics use and (1,2,3…n) for each month after the start of teleconsultation.

2.3. Estimation using fixed effects regression

To test the relationships, we specify cost as a function of instances of teleconsultations (Teleconsultations) and percentage of trained staff (Trained_staff) while controlling for various exogenous variables, X, as listed in Table 1. The regression equation is shown as follows:

Table 1.

Fixed effects estimation for healthcare costs

| DV: Specialist Outpatient_cost |

DV: Inpatient_cost |

DV: ED_cost |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Description of variable | Variable | Coefficient | Std. error | Coefficient | Std. error | Coefficient | Std. error |

| No. of teleconsultation session per month per nursing home (NH); | Tele_consults | −83.366*** | 22.378 | −470.971** | 235.259 | −66.362 | 54.519 |

| % of nursing staff trained per NH per month | Trained_Staff | −4.257 | 3.760 | 64.818 | 44.859 | −39.546*** | 10.462 |

| No. of physical visits by specialists per NH per month | Phyvisits | −155.723 | 195.241 | −137.24 | 1917.77 | 662.090 | 448.395 |

| No. of physical visits by specialists per NH per month | Visits_pat | 32.125 | 21.674 | −22.933 | 253.131 | −53.006 | 59.184 |

| No. of beds per NH per month | NH_beds | −1.460 | 4.776 | 75.104 | 62.362 | 9.247 | 14.575 |

| No. of staff per NH per month | NH_staff | −13.024** | 6.518 | −125.743 | 76.480 | −87.408*** | 17.798 |

| No. of Residents per NH per month | NH_residents | 10.673 | 5.711 | 116.790 | 71.789 | 57.386*** | 16.781 |

| No. of calls to general practitioner per NH per month | GP_calls | −147.452 | 175.342 | 1384.949 | 1380.872 | −154.190 | 322.759 |

| % of unplanned admissions per NH resident per month | Unplanned_adm | 18,178.72*** | 4240.96 | 513,547.9*** | 42,619.18 | 145,765.4*** | 9951.624 |

| No. of months since the use of telemedicine within NH | Month | −9.335 | 8.721 | −62.446 | 66.813 | −93.013*** | 15.560 |

| Constant | 352.482 | 372.789 | 9756.508*** | 3139.59 | 5921.531*** | 733.832 | |

| R-square (within) | 0.3260 | 0.5364 | 0.6616 | ||||

| R-square (total) | 0.3959 | 0.6873 | 0.7094 | ||||

*** Represents p-value < 0.01; ** represents p-value < 0.05; * represents p-value < 0.1.

Each of the three costs variables (specialist outpatient, inpatient and ED: Emergency Department) were regressed on the number of tele-consultations, trained staff controlling for exogenous variables.

where β represents the parameters, and εit measures random errors across nursing home and time. In order to partial out any unmeasurable differences across different nursing homes, we specify µi to represent the idiosyncratic error across nursing homes. Costit is operationalised separately as Specialist Outpatient Costs, Inpatient Costs and Emergency Department Costs. We performed a separate regression estimation for each cost type. Specifically, we regressed each of the costs variable (specialist outpatient, inpatient and emergency department) on the number of sessions of telegeriatrics (teleconsultations), the level of training received by the nurses (trained_staff) and other control variables described earlier and in Table 1. The regression technique used was fixed effects econometric estimation and this method is commonly applied to examine economic impact of interventions with panel data (Greene, 2011). The fixed effects estimator controls for any potential difference across nursing homes beyond the controls that were included in the model.

3. Results

A total of 859 teleconsultations were conducted across four nursing homes over the 4-year period. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the residents consulted are shown in Table 2. The residents were mostly female (60.1%) and Chinese (82.3%), and the average age was 76 years. Resident outcomes at 1-month post teleconsultation are also shown in Table 2. Majority of the residents consulted (83.5%) remained in the nursing home for continued monitoring by the nurses and/or a follow-up visit by a GP. The rest were sent to the emergency department (5.5%), died in the nursing home (5.5%), or visited a SOC (5.4%).Hospital admission rate was 159 per 100,000 resident days in Year 1 and 51 in Year 5. Emergency department transfers per 100,000 resident days decreased from 158 in Year 1 to 37 in Year 5.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of nursing home residents seen via videoconferencing. The demographic and clinical characteristics of nursing home residents seen via teleconsultation were collected from teleconsultation forms. Most cases referred for teleconsultation were residents with behavioural problems

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (± SD) | 76.2 (± 13.2) |

| Length of stay in nursing home (no. of years) | 4.8 (IQR 0.4–4.8) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 537 (60.1) |

| Male | 346 (39.1) |

| Race | |

| Chinese | 727 (82.3) |

| Indian | 85 (4.3) |

| Malay | 38 (9.6) |

| Others | 33 (3.7) |

| Resident Assessment Form (RAF) | |

| Cat 1 | 2 (0.2) |

| Cat 2 | 39 (4.4) |

| Cat 3 | 423 (47.9) |

| Cat 4 | 419 (47.5) |

| Has next-of-kin | 710 (80.4) |

| Common comorbidities | |

| Hypertension | 560 (63.4) |

| Dementia | 330 (37.3) |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 384 (43.5) |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 364 (41.2) |

| Previous stroke | 171 (19.4) |

| Depression | 162 (18.4) |

| Osteoarthritis | 130 (14.7) |

| Ischaemic Heart Disease | 107 (12.1) |

| Osteoporosis | 62 (7.0) |

| Previous fracture | 54 (6.1) |

| Admission within last 6 months | 279 (31.6) |

| Polypharmacy (≥ 9 medications) | 379 (43.0) |

| Main presenting complaint | |

| Behavioural | 290 (32.8) |

| Medication review | 151 (17.1) |

| Pain | 61 (6.9) |

| Skin rash/lesion | 55 (6.2) |

| Fever | 38 (4.3) |

| Investigation review | 32 (3.6) |

| Shortness of breath | 27 (3.1) |

| Poor appetite | 26 (2.9) |

| Swelling | 20 (2.3) |

| Change in mental status | 15 (1.7) |

| Others | 168 (19.0) |

| Primary diagnosis | |

| Dementia | 211 (23.9) |

| Infection | 82 (9.3) |

| Cancer | 52 (5.9) |

| Depression | 51 (5.8) |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 36 (4.1) |

| Psychological disorder | 36 (4.1) |

| Pneumonia | 35 (4.0) |

| Cellulitis | 30 (3.4) |

| Neurological disorder | 27 (3.1) |

| Urinary tract infection | 22 (2.5) |

| Others | 331 (37.5) |

| Resident outcome at 1 month post consult | |

| Remained in nursing home | 737 (83.5) |

| Sent to emergency department | 49 (5.5) |

| Died in nursing home | 49 (5.5) |

| Visited a specialist outpatient clinic | 48 (5.4) |

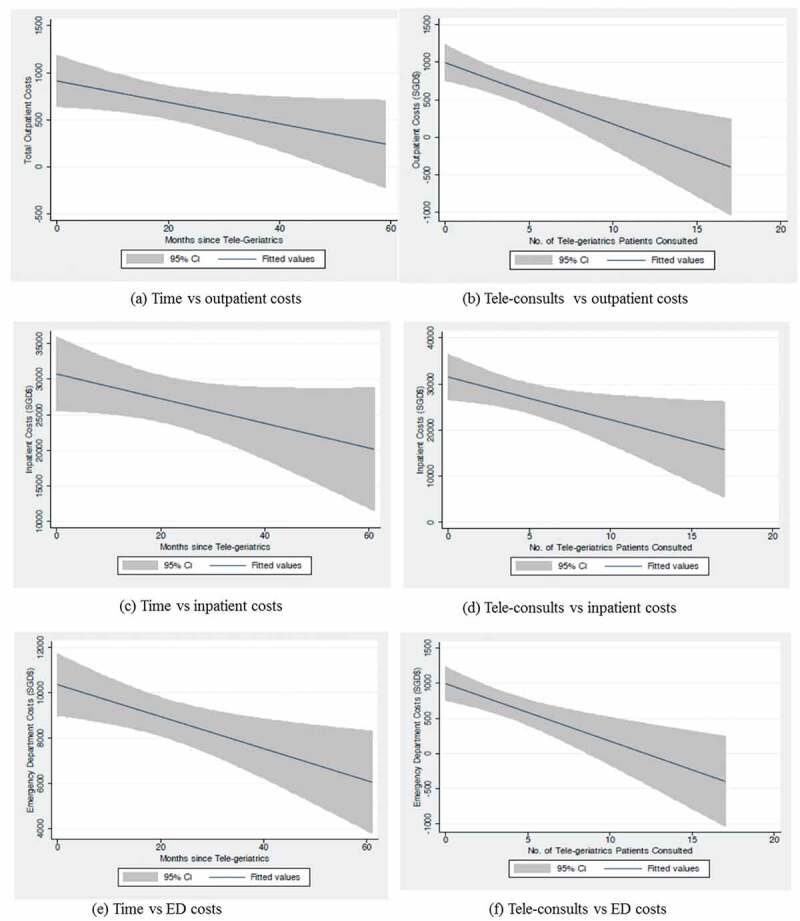

Before examining the results of the regressions, we plot the different cost categories against the number of teleconsultation sessions over time to visualise any changes in costs associated with the use of telemedicine. Figure 1 shows the relationship between the three cost variables, time and the number of teleconsultations. The graphs (a), (c), and (e) show that after introduction of teleconsultations, all the three costs – specialist outpatient, inpatient and ED – reduced over time. It is important to note that the line represent the simple correlation between the cost categories and number of months since telemedicine implementation and does not control for any other factors specified in the regression. The shaded area surrounding the line represents the vertical 95% confidence interval around each point on the line. Ranges are naturally larger if the standard deviation around that particular point on the line is larger. A similar downward trend was observed in graphs (b), (d), and (f), showing that with every unit increase in the number of teleconsultation sessions, the specialist outpatient, inpatient and emergency department costs declined.

Figure 1.

Simple correlation between cost, time and teleconsultations

Graphs (a)–(f) show a visual representation of simple correlation between time, tele-consults and costs without controlling for other factors. A downward trend is observed showing that with every unit increase in teleconsultation both inpatient and emergency department (ED) costs declined. A similar trend is observed between time and the two types of costs.

Beyond the descriptive statistics presented above, we also considered the results of panel data analyses for the three different costs, as shown in Table 1. These regressions allow us to control for other factors that may influence the various costs. Our results show that on a monthly and per nursing home basis, the use of telegeriatrics was associated with cost reductions in all the three types of cost. The results showed a significant relationship between teleconsultations and specialist outpatient cost (β1 = −83.366, p-value <0.01) and between teleconsultations and inpatient cost (β1 = −470.971, p-value <0.05). Based on the estimates, every teleconsultation session was associated with a cost reduction of S$83.366 on specialist outpatient costs incurred and simultaneously associated with a cost reduction of S$470.971 for inpatient costs per month after controlling for other exogenous factors. The number of teleconsultation sessions however was not associated with any significant change in emergency department cost. Emergency department cost however is negatively associated with the percentage of staff trained for TNTC; for every percentage increase in staff trained for the month there is a corresponding decline of S$39.546 in emergency department costs (i.e. β2 = −39.546, p-value <0.01). Finally, the percentage of trained staff was not significantly associated with any change in outpatient and hospitalisation costs.

4. Discussion

Singapore, a small city state of 5 million residents, comprises a multicultural population, which is ageing so rapidly that by the year 2030, 1 in 4 persons residing there will be 65-years-old or older (Population SG, 2016). This demographic change is attributable to a falling total fertility rate and rising life expectancy (The Straits Times, 2017), the latter being partly the result of Singapore having one of the best healthcare systems in the world (Pacific Prime Insurance Brokers Singapore, 2016). The shrinking family and rising old age dependency ratio are expected to exert pressure on the country’s economy and healthcare resources. More frail and dependent elderly will spend their last years in institutions such as assisted living and long term care facilities. Nursing homes in Singapore currently only accept very frail elderly patients who are dependent on others for at least two of their basic activities of daily living (Ministry of Health, 2017a). Despite these stringent criteria for admission, there is an acute shortage of subsidised nursing home beds in Singapore where the waiting time for admission can be up to six months.

GeriCare@North sought to reduce acute healthcare cost utilisation by providing access to geriatric care in an efficient, timely and effective way. It also sought to upskill the competency of long-term care nurses by providing an intensive and rigorous training course that empowered these nurses to act as remote physician assistants.

Teleconsultations provided a quick means for the nursing homes to consult the geriatric services in the acute hospital. It also saved travelling time for the busy hospital physician who was able to, at a click of a mouse, toggle between several nursing homes in one afternoon. This would not have been possible if the physician had to make onsite physical visits to the nursing homes.

Timely interventions by the telegeriatrics service allow for effective triaging and pre-empting of unnecessary SOC and ED visits. The savings from preventing just one avoidable or unnecessary ED visit or hospital admission are not insignificant (Ministry of Health, 2017b). Avoiding overly aggressive and futile investigations and treatment, especially at the end of life, can save the healthcare system a tremendous amount of money. The logistics and administrative resources required to transfer a bedridden and totally dependent patient from the nursing home to hospital, for routine SOC or ED visits are immense.

The Singapore government has adopted a philosophy of allowing the older person to ‘age-in-place’, marking a shift in emphasis from hospital-centric care to community care (Channel NewsAsia, 2016). Since much of the aged care expertise currently resides in the hospital setting, the use of telemedicine could potentially allow an efficient and effective way of reaching out remotely to the community. It also is a safe means of providing care if conducted with due diligence and safeguards in place.

This paper is the first ever report on a nursing home telemedicine project where costing is assessed using a health economics model. It shows cost savings to the healthcare provider (MOHS), which highly subsidises public healthcare in Singapore based on means testing and a hospital class-based system. We postulate that cost savings observed accrue for the following reasons:

Averting unnecessary transfers (to the SOC and ED) and hence admissions to hospital, which in turn, reduces costs by avoiding futile investigations, interventions, and procedures in frail older patients.

The administrative and logistics cost of transporting a dependent frail elderly between locations is high. For such patients, it may be more cost effective to bring care to them at their place of domicile (aging in place); but even more compelling would be to bring care to them via telemedicine as this would obviate the cost of transporting the physician and nurse to the patients’ domicile.

Nursing home care invariably costs less than acute hospital care. Whenever possible, patients who reside in nursing homes should be cared for in the long-term care facilities. The TNTC allows the nurses to practice at the top of their license, obviating or minimising the need for more costly on-site physician coverage.

The telegeriatrics service allows for earlier discharge from hospital as patients are given an earlier follow up appointment with the service. This potentially shortens the length of hospital stay and avoids the need for subsequent follow-up visits to the SOC.

Timely and quick medication review by the telegeriatrics service allows for rapid titration and where necessary, the removal of unnecessary medications in the patients’ medication list. This reconciliation of medications reduces cost further and is a form of anticipatory care that pre-empts acute exacerbations of chronic diseases, which would otherwise lead to further hospitalisations.

One of the limitations of this study is that there was no control group for the cohort notwithstanding the fact that it was an observational study where the latter acted as its own control. Hence, we could not compare outcomes of the residents who enrolled in telegeriatrics with those who did not. Further research could include a qualitative component to get a more in-depth understanding of the user experience, particularly around resident outcomes and to look at the reliability and feasibility of videoconferencing in nursing homes in the local context.

5. Conclusion

The world is witnessing a demographic sea change where large segments of the population are ageing rapidly. This phenomenon exerts pressure on healthcare infrastructure and drain the economy of its resources. We are of the opinion that technology, if harnessed carefully, may be able to increase the efficiency and productivity of the healthcare industry. Findings of this study show that telemedicine consultations could reduce SOC visits and hospital admissions in the nursing home setting, and therefore lead to cost savings. Training of nursing home nurses could translate to cost savings as a result of decreased ED transfers. Future research should assess impact of GeriCare@North on quality of care for nursing home residents.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Asiaone . (2012). Nursing home crunch means longer wait [Online]. Retrieved from http://www.asiaone.com/print/News/Latest%2BNews/Health/Story/A1Story20121211-388866.html

- Binstock, R. H., & Spector, W. D. (1997). Five priority areas for research on long-term care. Health Services Research, 32, 715. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Channel NewsAsia . (2016). A ‘paradigm shift’ needed in approach to ageing and health: Gan Kim Yong. [Online]. Retrieved from www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/a-paradigm-shift-needed-in-approach-to-ageing-and-health-gan-kim-8110692

- Commonwealth Fund . (2015). Frugal innovations: global case studies [Online]. Retrieved from www.commonwealthfund.org/grants-and-fellowships/grants/2015/jan/translating-frugal-innovations-into-the-us-health-system

- Dixon, P., Hollinghurst, S., Edwards, L., Thomas, L., Foster, A., Davies, B., … Salisbury, C. (2016). Cost-effectiveness of telehealth for patients with depression: Evidence from the Healthlines randomized controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry Open, 2, 262–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driessen, J., Bonhomme, A., Chang, W., Nace, D. A., Kavalieratos, D., Perera, S., & Handler, S. M. (2016). Nursing home provider perceptions of telemedicine for reducing potentially avoidable hospitalizations. Journal of American Medical Directors Association, 17(6), 519–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene, W. (2011). Econometric analysis (7th ed.). London, UK: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, C., Knapp, M., Fernandez, J. L., Beecham, J., Hirani, S. P., Cartwright, M., … Newman, S. P. (2013). Cost effectiveness of telehealth for patients with long term conditions (whole systems demonstrator telehealth questionnaire study): Nested economic evaluation in a pragmatic, cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ, 346, f1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmeyer, J., Leider, J. P., Satorius, J., Tanenbaum, E., Basel, D., & Knudson, A. (2016). Implementation of telemedicine consultation to assess unplanned transfers in rural long-term care facilities, 2012–2015: A pilot study. Journal of American Medical Directors Association, 17, 1006–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyketsos, C. G., Roques, C., Hovanec, L., & Jones, B. N. (2001). Telemedicine use and the reduction of psychiatric admissions from a long-term care facility. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 14, 76e79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health . (2017a, August 1). Nursing homes [Online]. Retrieved from https://www.moh.gov.sg/content/moh_web/home/our_healthcare_system/Healthcare_Services/Intermediate_And_Long-Term_Care_Services/Nursing_Homes.html

- Ministry of Health . (2017b, August 1). Pneumonia. [Online]. Retrieved from www.moh.gov.sg/content/moh_web/home/costs_and_financing/hospital-charges/Total-Hospital-Bills-By-condition-procedure/pneumonia.html

- Mistry, H. (2012). Systematic review of studies of the cost-effectiveness of telemedicine and telecare. Changes in the economic evidence over twenty years. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 18(1), 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbould, L., Mountain, G., Hawley, M. S., & Ariss, S. (2017). Videoconferencing for health care provision for older adults in care homes: A review of the research evidence. International Journal of Telemedicine and Applications, 2017, 5785613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacific Prime Insurance Brokers Singapore . (2016). Singapore healthcare ranks as 2nd most efficient worldwide [Online]. Retrieved from www.pacificprime.sg/blog/2016/10/20/singapore-healthcare-efficiency/

- Population SG . (2016). Older Singaporeans to double by 2030 [Online]. Retrieved from www.population.sg/articles/older-singaporeans-to-double-by-2030/

- Richter, K. P., Shireman, T. I., Ellberbeck, E. F., Cupertino, A. P., Catley, D., Cox, L. S., … Lambart, L. (2015). Comparative and cost effectiveness of telemedicine versus telephone counseling for smoking cessation. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17, e113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Straits Times . (2017, August 1). Long waits at A&Es despite more beds [Online]. Retrieved from www.straitstimes.com/singapore/health/long-waits-at-aes-despite-more-beds/

- Thrall, J. H., & Boland, G. (1998). Telemedicine in practice. Seminar in Nuclear Medicine, 28, 145e157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division . (2015). World population ageing 2015 (ST/ESA/SER.A/390).

- World Health Organization . (2012). Spending on health: A global overview fact sheet [Online]. Retrieved from www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs319/en/