Abstract

Elastic and muscular arteries differ in structure, function, and mechanical properties, and may adapt differently to aging. We compared the descending thoracic aortas (TA) and the superficial femoral arteries (SFA) of 27 tissue donors (average 41±18 years, range 13–73 years) using planar biaxial testing, constitutive modeling, and bidirectional histology. Both TAs and SFAs increased in size with age, with the outer radius increasing more than the inner radius, but the TAs thickened 6-fold and widened 3-fold faster than the SFAs. The circumferential opening angle did not change in the TA, but increased 2.4-fold in the SFA. Young TAs were relatively isotropic, but the anisotropy increased with age due to longitudinal stiffening. SFAs were 51% more compliant longitudinally irrespective of age. Older TAs and SFAs were stiffer, but the SFA stiffened 5.6-fold faster circumferentially than the TA. Physiologic stresses decreased with age in both arteries, with greater changes occurring longitudinally. TAs had larger circumferential, but smaller longitudinal stresses than the SFAs, larger cardiac cycle stretch, 36% lower circumferential stiffness, and 8-fold more elastic energy available for pulsation. TAs contained elastin sheets separated by smooth muscle cells (SMCs), collagen, and glycosaminoglycans, while the SFAs had SMCs, collagen, and longitudinal elastic fibers. With age, densities of elastin and SMCs decreased, collagen remained constant due to medial thickening, and the glycosaminoglycans increased. Elastic and muscular arteries demonstrate different morphological, mechanical, physiologic, and structural characteristics and adapt differently to aging. While the aortas remodel to preserve the Windkessel function, the SFAs maintain higher longitudinal compliance.

Keywords: elastic artery, muscular artery, mechanical properties, constitutive modeling, aging

1. INTRODUCTION

Arterial mechanical and structural characteristics play important roles in physiology and pathophysiology, and profoundly influence the design of devices for open and endovascular repair[1–4]. Arteries can be broadly divided into elastic and muscular types. Elastic arteries are larger and are located closer to the heart. They contain a substantial amount of elastin organized primarily in the form of circumferential elastic lamellae sheets[5–7]. These sheets allow the elastic arteries to act as a buffering chamber behind the heart, storing the elastic energy during peak systole and returning it during diastole when the heart rests[6,8,9]. This buffering feature (also known as the Windkessel effect) protects the left ventricle from pressure injury[10], perfuses the coronary bed, and provides nearly continuous peripheral flow. Muscular arteries serve a different purpose. They distribute blood from the elastic arteries to the downstream tissues and organs and regulate the amount of that delivery by relaxing and contracting the concentric layers of smooth muscle cells that populate most of their tunica media[11]. In muscular arteries, the internal elastic lamina (IEL) sheet separates tunica intima from the tunica media, but most elastin is organized as longitudinally-oriented elastic fibers in the external elastic lamina (EEL) at the border of tunica media and adventitia[12,13]. These elastic fibers play important roles in facilitating longitudinal pre-stretch[14] and storing the elastic energy that aids end-organ motions, such as flexion of the limbs or movement of the kidneys during respiration, thereby promoting better hemodynamics[15,16], reducing arterial bending and kinking[17], and ensuring energy-efficient function[18].

Structural and functional differences in elastic and muscular arteries expectedly result in their mechanical differences[19–21], but most studies comparing the stiffness and morphometry of human elastic and muscular arteries were performed in vivo[19,20,22–29] and have used either pulse wave velocity or distensibility as surrogate measures for arterial stiffness. While useful for in vivo evaluation, these techniques are limited to the narrow physiologic load range, and cannot reliably assess intrinsic material properties, residual stresses, or true physiologic intramural stresses[30,31] that are a function of pre-stretch and the opening angles. Detailed ex vivo mechanical and structural analyses of human elastic and muscular arteries that allow this comparison have previously been reported [32–38], but the arteries were not obtained from the same human subjects. Few studies have performed this comparison in animals [20,39,40], but human data remain limited[12]. The goal of our study was to compare the mechanical and structural characteristics of human elastic and muscular arteries of different ages, and determine how they affect arterial physiologic characteristics and remodeling due to aging. To achieve this, we compared human descending thoracic aortas (TA) and superficial femoral arteries (SFA) from the same human donors using multi-ratio planar biaxial mechanical testing, bidirectional structural analysis, and constitutive modeling.

2. METHODS

2.1. Arterial specimens

Descending TAs 1 cm distal to the left subclavian artery, and SFAs 1 cm distal to the profunda femoris artery were obtained from 27 tissue donors 13–73 years old (average age 41±18 years, 78% male, please refer to Appendix 5.1 for detailed demographics and risk factor data) within 24 hours of death after obtaining consent from next of kin. Tissues were transported in 0.9% phosphate-buffered saline at 4°C, and tested fresh within 4 hours of procurement. Prior to the excision of the SFAs, their longitudinal pre-stretch was measured using an umbilical tape[14]. Pre-stretch of the TAs was not measured but was estimated using previously published data[33,41] and subject’s age according to .

Arterial rings (2mm in length) were photographed in the load-free and stress-free configurations to measure the circumferences of the intimal and adventitial surfaces (lint, ladv, Lint, Ladv) and the circumferential and longitudinal opening angles (α, β) after allowing the artery to equilibrate for at least 25 minutes in saline (Figure 1, representative images are provided in the Supplement). Wall thicknesses were measured in at least 10 different locations across the circumference of the stress-free cut ring (H) and load-free ring (h), and the average values for each specimen were calculated. All measurements were performed by the same operator, and the variability in thickness measurements was <10%. Measurements of the circumference and opening angle allowed calculations of the load-free and stress-free radii ρint, ρadv, Rint, Radv as[11,42,43]:

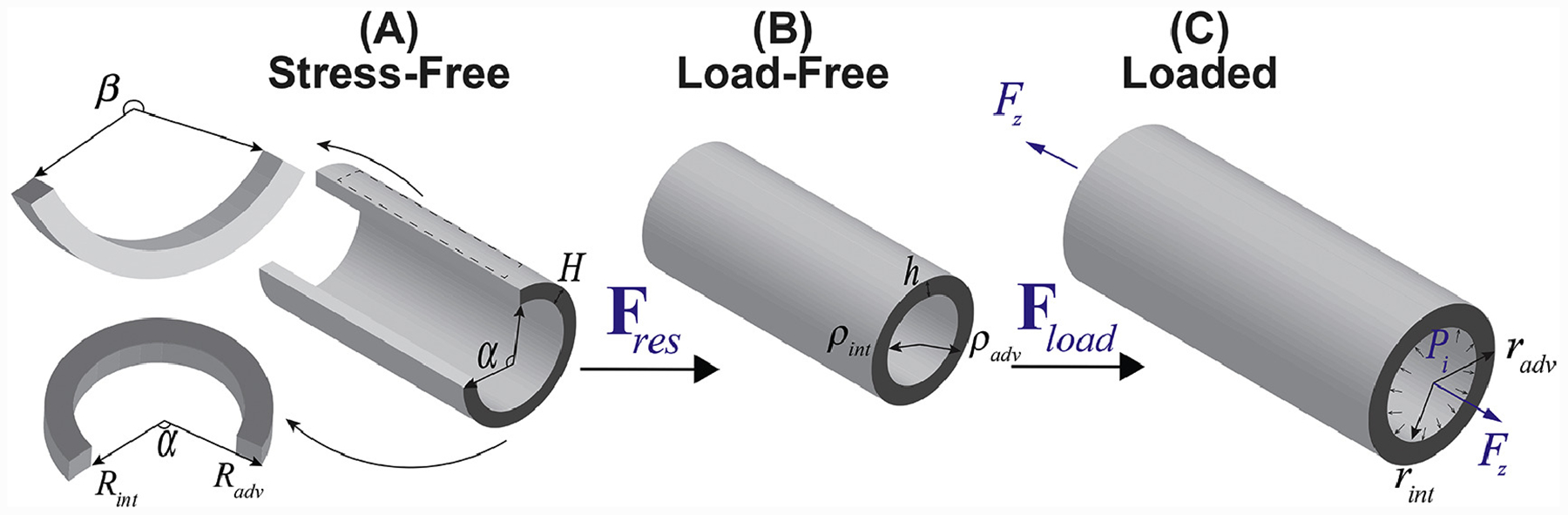

Figure 1:

Arterial kinematics demonstrating (A) stress-free configuration obtained by radially opening the artery and cutting out a longitudinal strip, (B) load-free configuration with no internal pressure or longitudinal pre-stretch, and (C) the in vivo loaded state.

2.2. Planar Biaxial Testing

Planar biaxial tests were performed on 13 × 13 mm stress-free arterial specimens submerged into 0.9% phosphate-buffered saline at 37°C to determine the intrinsic mechanical behavior of the tissue[32,44]. Details of these tests can be found in our previous works[32,33,44,45], but will briefly be summarized here for completeness. Test axes were aligned with the longitudinal and circumferential directions of the artery, and specimens were attached using rakes as previous studies demonstrated negligible shear in both TA and SFA specimens[12,46]. All samples were sprinkled with graphite markers to allow measurement of the deformation gradient in the center of the sample, preloaded with 0.02–0.1N force, and subjected to 20 equibiaxial cycles of preconditioning until the force-stretch curves became repeatable. After that, a total of 21 stretch-controlled multi-ratio protocols were applied to obtain sufficient data density for constitutive modeling. These protocols covered circumferential to longitudinal stretch ratios of 1:0.1 to 1:0.9 and 0.9:1 to 0.1:1 with 0.1 step, intermixed with three 1:1 equibiaxial protocols in the beginning, middle, and the end of the test sequence to ensure the absence of tissue damage. Maximum stretch levels were selected for each specimen to ensure non-linearity in the force-stretch curves while avoiding excessive stretch that can cause tissue damage. This was achieved by equibiaxially stretching the samples up to 1–1.5N prior to preconditioning and estimating the maximum stretch for each direction[44,47]. These stretches ranged from 1.08 to 1.63 depending on tissue compliance, and for most specimens corresponded to 1N force. All specimens were tested at 0.01 s−1 strain rate, and Cauchy stresses averaged through the thickness of the specimen were calculated as a function of the applied stretches in both the longitudinal () and the circumferential () directions as:

| Eq 1 |

where hexp is the deformed thickness of the specimen in the current configuration during the biaxial test, pz and pθ are the applied forces in the longitudinal and circumferential directions, and lz and lθ are the deformed lengths over which these forces act. Assuming tissue incompressibility during the biaxial test (hexplzlθ = H LzLθ), the above equation can be simplified to

where λz and λθ are the experimental biaxial stretches, H is the stress-free specimen thickness (Figure 1), and Lθ and Lz are the initial dimensions of the specimen over which the biaxial forces (pz and pθ) are applied. For all specimens Lz and Lθ were 7.5mm. Note that λz and λθ are the diagonal components of the deformation gradient determined in the center of the specimen by tracking the graphite particles[45].

2.3. Constitutive Modeling

Experimental data were used to determine the constitutive parameters for the four-fiber family invariant-based model[44] previously shown to accurately portray the passive behavior of both elastic and muscular human arteries of different ages[32,33,44]. The four-fiber family strain energy function W for this model is given by:

| Eq 2 |

Here Ic = tr(C) is the first and is the fourth invariant of the right Cauchy-Green stretch tensor C = FTF and the structural tensor Mi ⊗ Mi, that measures square of the stretch along the fiber direction Mi in the reference configuration and is equal to

where γi is the angle of fiber family i with the longitudinal direction. Further, γi = 0 phenomenologically accounts for the longitudinal fibers that have material parameters , , and γi = 90° accounts for the circumferential fibers that have material parameters , . The two families of helical fibers have the same mechanical properties , , and are oriented at γi = γ to the longitudinal direction. Macaulay brackets are used to filter positive values, so fibers only contribute to stress during tension.

The total Cauchy stress can then be calculated as follows:

| Eq 3 |

where, contains the deformation dependence[48], mi = FMi is the push-forward of the unit vector Mi, p is the Lagrange multiplier (it does not represent the hydrostatic pressure[48]), and B = FFT is the left Cauchy-Green stretch tensor. Constitutive parameters were determined by minimizing the difference between the experimental stress determined using Eq 1 (after adjustment for the flattening of the stress-free specimens[32,49]), and the theoretical stress calculated using Eq 3. To ensure parameter uniqueness, we have performed a non-parametric bootstrap as described previously[34,44], and have determined the global minimum for each constitutive parameter. The quality of fits was assessed using the coefficient of determination R2 calculated as

Here i represents each experimental data point and and are the coefficients of determination in the circumferential and longitudinal directions, respectively.

To compare the intrinsic stiffness of the specimens, we have determined stretches corresponding to different levels of equibiaxial stress by solving the stress equation (Eq 3) for the stretches using the least square nonlinear method[44].

2.4. Assessment of the residual and physiologic stress-stretch states

Arterial morphometry measurements and constitutive parameters determined from the experimental data were used to determine residual and physiologic stresses and stretches. Details of this kinematic framework can be found elsewhere[32,33]. Briefly, deformation gradients associated with transitions from the stress-free to the load-free and to the in vivo loaded states can be written as[11,50–52] , and , where R, ρ and r represent the stress-free cut ring, load-free and loaded ring radii, respectively, is a measure of the opening angle, and λζ and are the residual and in situ longitudinal stretches, respectively. Note that the deformation Fphys includes both the residual deformations (i.e., deformations from the stress-free to the load-free state), and the loading (i.e., deforamtions from the load-free to the loaded states).

Assuming incompressibility, one can find the stress-free and the loaded radii, R and r respectively, as a function of the load-free radius ρ:

| Eq 4 |

| Eq 5 |

where λζ is assumed to be equal to 1[11]. The adventitial radius Radv and the measure of the opening angle K in Eq 4, radv in Eq 5, and the Lagrange multiplier p in Eq 3 can be determined using the equilibrium equations derived from the balance of linear momentum, the boundary conditions of zero pressure on the adventitial surface and zero axial force in the load-free state, and the assumption of zero pressure on the adventitial surface (i.e., no perivascular tethering) in the loaded state[11,32,33,50–52].

The linearized physiologic circumferential stiffness was calculated as the change in the average circumferential physiologic stress between systole (120 mmHg) and diastole (80 mmHg) divided by the change in the average circumferential stretch[32]:

| Eq 6 |

Here and are the through-thickness average circumferential physiologic Cauchy stress and stretch calculated by integrating them over the current volume and dividing by the total current volume[32]:

The strain energy W (Eq 2) was calculated at diastole and systole to assess elastic potential available for pulsation, and the change in the average circumferential physiologic stretch during the cardiac cycle was calculated as:

| Eq 7 |

Please note that to determine stresses and radii in Eq 6 and Eq 7, was used as arterial stretch in the longitudinal direction.

2.5. Structural Analysis

Structural analysis was done using bidirectional histology and arterial sections immediately adjacent to the mechanically tested specimens. Due to previously reported directional differences in elastic fiber and lamellae architecture[53,54], and to characterize the tissue both across the circumference and along a short segment of the artery length (~1cm), we have performed the structural analysis using both transverse and longitudinal sections. All tissues were fixed in methacarn, dehydrated in 70% ethanol, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned serially using a microtome. Verhoeff-Van Gieson (VVG), Masson’s Trichrome (MTC), α-smooth muscle cell actin (α-SMA), and Movat’s Pentachrome stains of the consecutive sections were used to quantify elastin, collagen, smooth muscle actin, and glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), respectively.

Histological images were analyzed using a semi-automated custom-made software (Figure 2) written in Visual Studio C# with .Net 4.6.2 framework and OpenCV libraries. This software allowed selection of the boundaries corresponding to different arterial structures, such as tunica intima, media, EEL (in the SFA), and adventitia, and color thresholding to assess constituent density in each arterial layer. Color selection was performed in the Red, Green, Blue (RGB) color space rather than in the Hue, Saturation, Value/Lightness (HSV/HSL)[55,56] model because the RGB was more sensitive to subtle changes in lightness and contrast and offered higher accuracy of color selection. The constituent density within the layer was calculated by dividing the number of pixels associated with that constituent by the total number of pixels bound by the layer. All analyses were performed by a single operator to reduce variability.

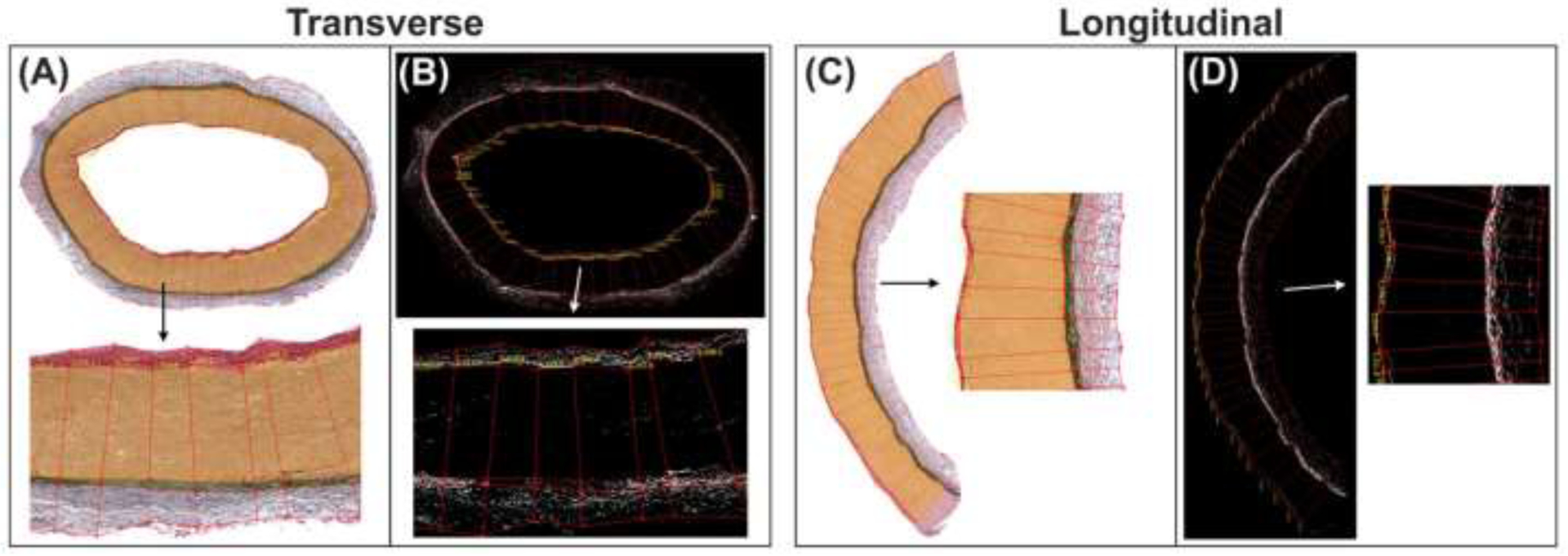

Figure 2:

The custom-written software used to measure the thicknesses of each arterial layer and the density of various intramural constituents in them using transverse (A,B) and longitudinal (C,D) arterial sections. Panels (B) and (D) illustrate the assessment of elastin density on VVG-stained SFA sections (A,C).

2.6. Statistical analysis

Pearson correlation coefficient r was used to assess the strength of the linear relationship between continuous variables, with values closer to ±1 demonstrating stronger relations. Statistical significance of the observed correlations was assessed by testing the hypothesis of no correlation (i.e., the null hypothesis) against the alternative hypothesis of nonzero correlation using an independent sample t-test, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Where appropriate, results are presented as mean±standard deviation. When discussing young and old specimens, those are defined as <20 and >60 years old.

3. RESULTS

Wall thickness, opening angles, and radii of all analyzed TAs and SFAs are presented in Figure 3. Young (<20 years old) TAs were 32% thicker than the SFAs, but older (>60 years old) TAs were twice thicker. In young subjects, the thickness of the load-free ring was somewhat larger than the thickness of the stress-free ring (by 5% in the TAs and by 1% in the SFAs), but in the older subjects, the results were reversed, and the stress-free thickness was 30% (TA) and 14% (SFA) larger than the load-free thickness. In the TA, the stress-free thickness increased with age faster than the load-free thickness (r = 0.74 and r = 0.52, p < 0.01), while in the SFA, the stress-free thickness also increased with age (r = 0.45, p = 0.02), but the load-free thickness did not (r = 0.14, p = 0.49). Collectively, these results indicate an accumulation of compressive residual radial strains in both the TAs and the SFAs with age.

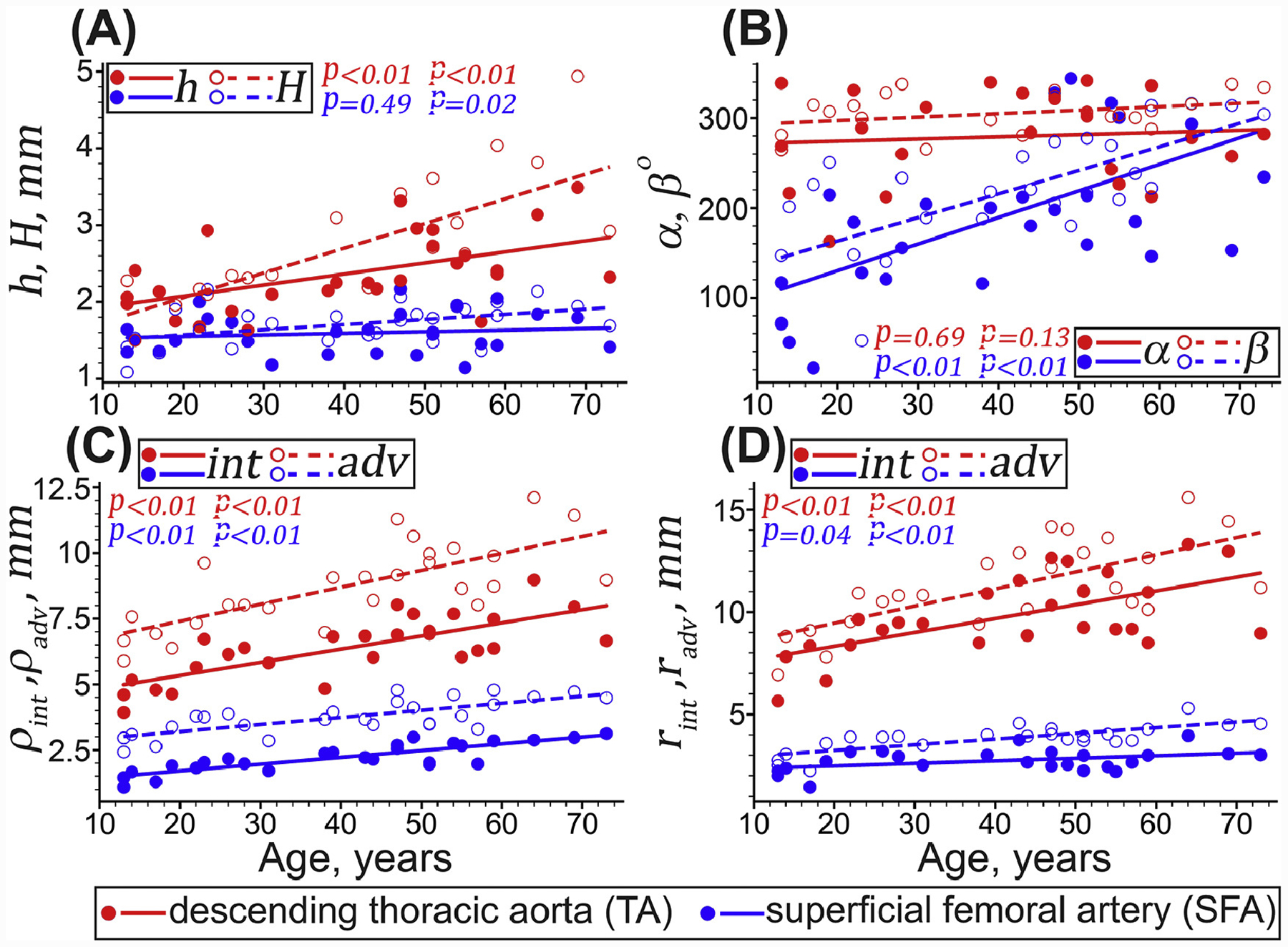

Figure 3:

Changes with age in the TA (red) and the SFA (blue) morphometric characteristics. (A) load-free (h, filled circles and lines) and stress-free (H, hollow circles and dashed lines) thicknesses of the arterial ring, (B) circumferential (α, filled circles and lines) and longitudinal (β hollow circles and dashed lines) opening angles, (C) load-free, and (D) loaded in vivo radii (ρ) measured at the inner (i.e., intimal [int], filled circles and lines) and outer (i.e., adventitial [adv], hollow circles and dashed lines) surfaces. Circles and lines represent the experimental values and linear regression fits, respectively. P-values indicate the statistical significance of the Pearson correlation between age and each morphometric variable.

The circumferential (α) and longitudinal (β) opening angles changed similarly with age in both arteries. In the TAs, α and β stayed relatively constant with age (α = 279 ± 50°, r = 0.1, p = 0.69 and β = 305 ± 20°, r = 0.33, p = 0.13), but in the SFAs, these angles increased (r = 0.62, p < 0.01 for α and r = 0.7, p < 0.01 for β).

Radii in the load-free and loaded in vivo states increased with age in both arteries (p < 0.01). In the TA the load-free through-thickness-average radii increased with age by 63%, while in the SFA they increased by 73%. In the SFA the inner and outer radii increased similarly with aging, but in the TA the outer radius increased 1.29-fold faster than the inner radius. In the loaded in vivo state, through-thickness-average radii increased with age 61–64% in both arteries, with the outer radii increasing faster than the inner radii. Overall, these results suggest that arterial thickening occurred primarily through an outward remodeling mechanism, i.e., with the larger increases in the outer radius compared with the inner radius (the proportion of slopes was 1.24-fold for the TA and 2.4-fold for the SFA).

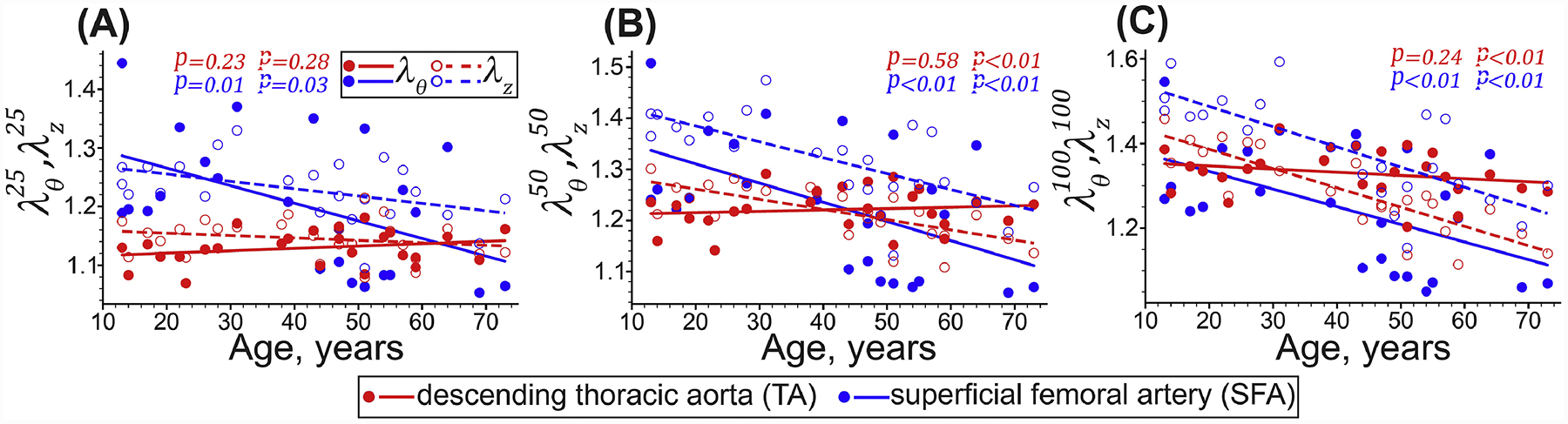

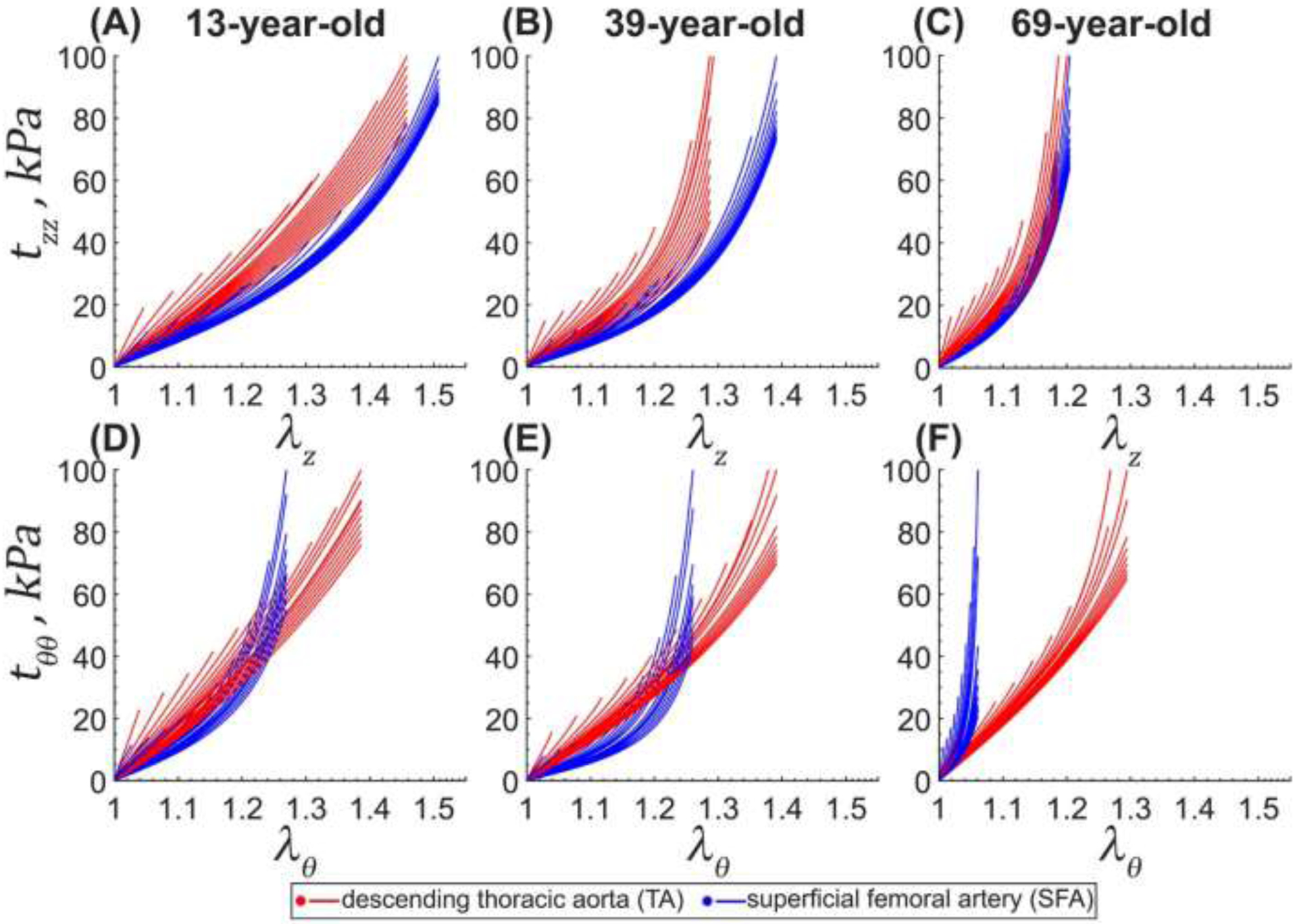

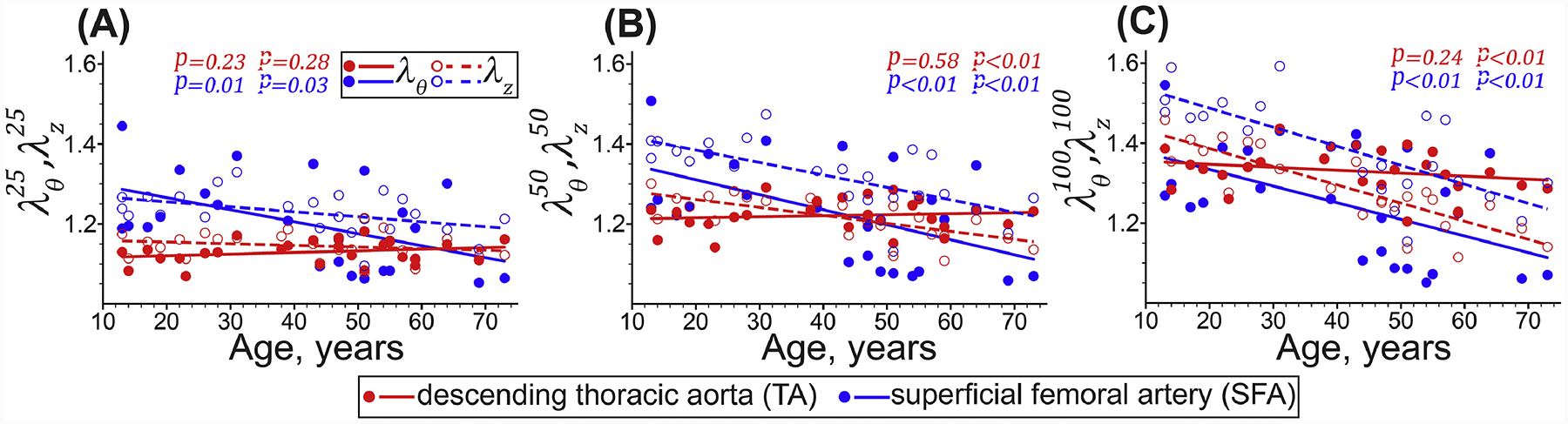

Young TAs were relatively isotropic, but after 40 years of age, the anisotropy increased, and the tissues became stiffer longitudinally than circumferentially, while the biaxial stress-stretch response became more nonlinear. Figure 4 and Figure 5 illustrate this by showing similar biaxial stretches at low stresses, but lower longitudinal than circumferential stretches at high stresses in older TAs. Longitudinal stretches corresponding to 100kPa equibiaxial stress () decreased significantly with age (r = −0.85, p < 0.01), but the change in circumferential stretches () was not significant (r = −0.24, p = 0.24). Young SFAs were more compliant longitudinally than circumferentially, and this effect persisted across all ages (Figure 4 and Figure 5). The SFAs stiffened with age significantly in both longitudinal (r = −0.74, p < 0.01) and circumferential (r = −0.55, p < 0.01) directions, but remained approximately 51% larger than . Constitutive model parameters and the quality of fit for all specimens are summarized in Appendix 5.2. Representative experimental Cauchy stress-stretch responses for several TAs and SFAs are provided in the Supplement.

Figure 4:

Equibiaxial stretches corresponding to the (A) 25 kPa, (B) 50 kPa, and (C) 100 kPa Cauchy stresses in the circumferential (θ, solid circles and lines) and longitudinal (z, hollow circles and dashed lines) directions determined by solving the stress equations using the least square nonlinear method. Circles and lines represent the experimental values and linear regression fits, respectively. P-values indicate the statistical significance of the Pearson correlation between age and each variable.

Figure 5:

Cauchy stress-stretch responses for the descending thoracic aorta (TA, red) and the superficial femoral artery (SFA, blue) of a representative 13-year-old (A,D), 39-year-old (B,E), and 69-year-old (C,F) subjects obtained using the four-fiber family constitutive model. For each specimen, the circumferential and longitudinal stretches corresponding to 100kPa equibiaxial stress were determined first, and then the multi-ratio stress-stretch responses were generated as described in section 2.3. Multiple curves represent different loading protocols. Here θ is circumferential, and z is the longitudinal direction. Constitutive model parameters for all evaluated specimens are summarized in Appendix 5.2.

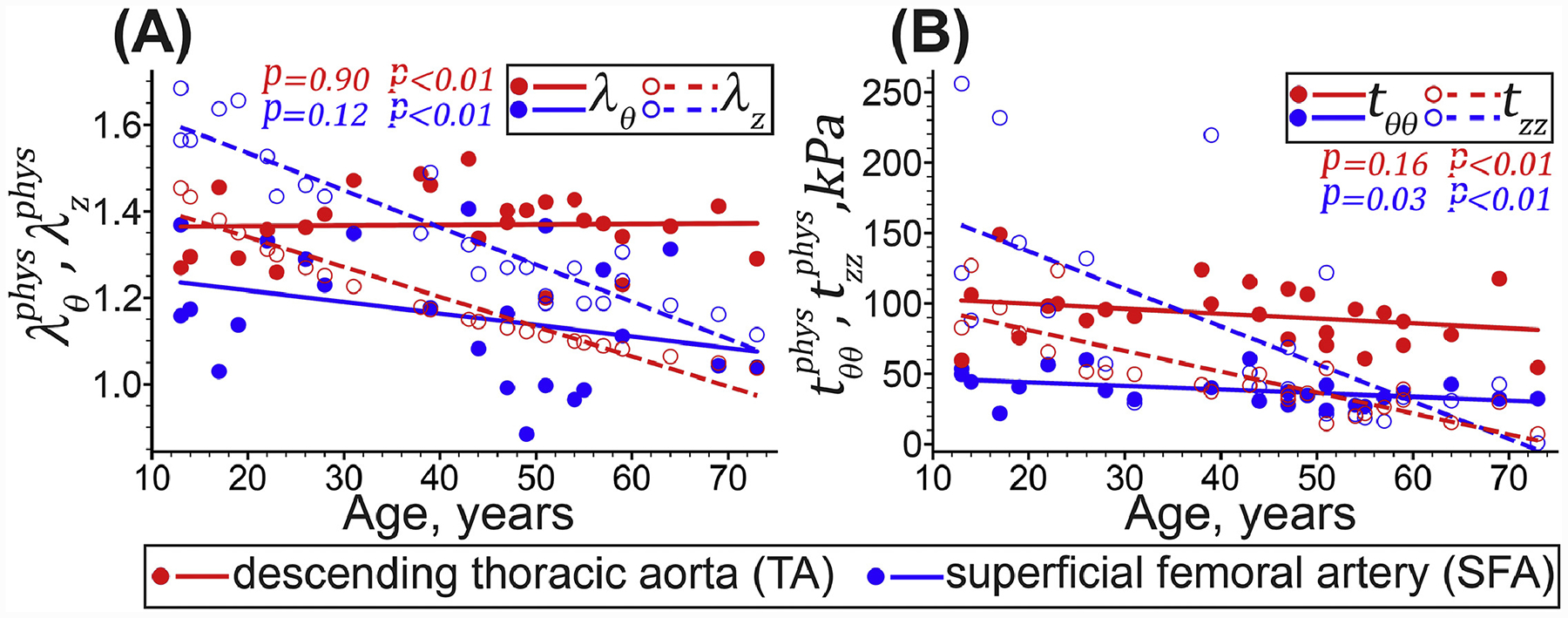

In the longitudinal direction, physiologic stretch (r = −0.96 in the TA and r = −0.93 in the SFA, both p < 0.01) and stress (r = −0.84 in the TA and r = −0.68 in the SFA, both p < 0.01) decreased with age in both arteries (Figure 6). In the circumferential direction, physiologic stretches and stresses stayed relatively constant with age in the TA (1.37 ± 0.08 and 92 ± kPa, p = 0.90 and p = 0.16, respectively). In the SFA, the physiologic circumferential stretch changed insignificantly with age (p = 0.12) and was on average 1.16 ± 0.15, but the stress decreased from 42 ± 10 kPa to 36 ± 6 kPa (r = −0.43, p = 0.03). In young SFAs, was 4-fold larger than the , but in young TAs, both stresses were similar and around 97 ± 30 kPa. In old SFAs and TAs, the result was reversed, and was smaller than . Young SFAs had higher longitudinal stresses than the TAs (168 ± 70 vs 97 ± 20 kPa), but in old specimens, the stresses were similar and around 21 ± 20 kPa.

Figure 6:

Physiologic stress-stretch behavior of the descending thoracic aorta (TA, red) and the superficial femoral artery (SFA, blue) in the circumferential (θ, solid circles and lines), and longitudinal (z, hollow circles and dashed lines) directions. Circles and lines represent the experimental values and linear regression fits, respectively. P-values indicate the statistical significance of the Pearson correlation between age and each variable.

During the cardiac cycle (Figure 7), young TAs experienced 1.14 ± 0.03 circumferential stretch while old aortas stretched only 1.06 ± 0.02 (r = −0.80, p < 0.01). In contrast, young SFAs changed their diameter only 3% over the cardiac cycle, and this value dropped to 2% in older SFAs (r = −0.56, p < 0.01). The elastic energy density available for pulsation (Wsys − Wdias) was much higher in young TAs (13 ± 3 kPa) than in the SFAs (1.4 ± 0.3 kPa), and as both arteries stiffened with age, the elastic reserve diminished but remained larger in the TA (5 ± 3 kPa) than in the SFA (0.7 ± 0.5 kPa). Physiologic circumferential stiffness (Eθ) increased with age in both arteries (r = 0.42 in the TA and r = 0.45 in the SFA, both p = 0.03), but the SFA stiffened 20% more, from 565 ± 200 kPa to 918 ± 400 kPa, while the stiffness of the TA changed from 396 ± 200 to 566 ± 70 kPa.

Figure 7:

Physiologic characteristics for the TAs and SFAs including (A) the circumferential stretch experienced by the artery during the cardiac cycle, (B) the stored elastic energy due to pulsation at diastolic ([dias] 80mmHg, solid circles and lines) and systolic ([sys] 120mmHg, hollow circles and dashed lines) pressures, and (C) the circumferential stiffness Eθ defined as the change in circumferential physiologic stresses divided by the change in the corresponding stretches during the cardiac cycle. Circles and lines represent the experimental values and linear regression fits, respectively. P-values indicate the statistical significance of the Pearson correlation between age and each physiologic variable.

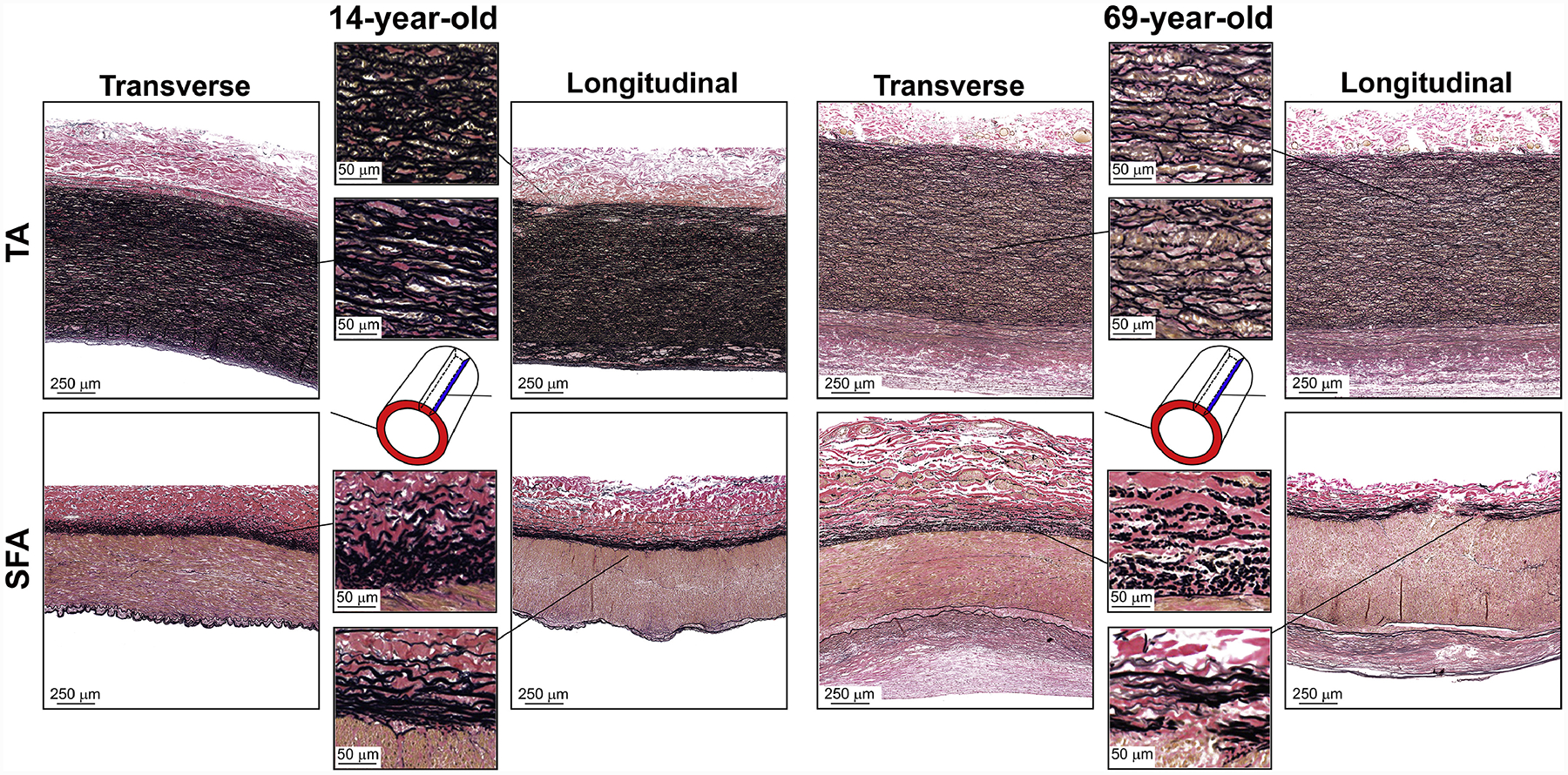

Representative bidirectional histology images of young (14-year-old) and old (69-year-old) specimens showing elastin (VVG), collagen (MTC), smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), and GAGs (Movat) are presented in Figure 8Figure 9,Figure 10, and Figure 11, respectively. Quantitative assessments of each constituent in the transverse and longitudinal directions are plotted in Figure 12. The graphs demonstrate similar trends for both directions, but several important differences in the rate of change. Please note, that the summation of all densities was not necessarily equal to 100%[57] because in addition to the elastin, collagen, smooth muscle, and GAGs, the arterial wall may also contain other constituents (i.e., lipids and calcification) that were not included in the current analysis.

Figure 8:

Representative transverse and longitudinal VVG-stained images of the descending thoracic aorta (TA, top) and the superficial femoral artery (SFA, bottom) of a 14-year-old and 69-year-old subjects, demonstrating differences in the elastin (black) content. In the TA, the elastin is concentrated primarily in the tunica media and is organized in lamellae sheets, while in the SFA the elastin is primarily in the form of longitudinal fibers in the EEL, the IEL sheet, and small isolated fragments scattered throughout the tunica media. Older arteries have more degraded, fragmented, and less dense elastin.

Figure 9:

Representative transverse and longitudinal MTC-stained images of the descending thoracic aorta (TA, top) and the superficial femoral artery (SFA, bottom) of a 14-year-old and 69-year-old subjects, demonstrating the differences in collagen (blue) structure. Collagen is present throughout the arterial wall of both arteries, and its density in the tunica media is higher in the older SFA specimens. The tunica media of the old TA has more net collagen than the young, but its density is not different. Collagen fibers follow the same path as the elastic lamellae and are circumferentially-oriented. In the tunica media of the SFA, collagen is filling the gaps between the SMCs that appear circumferentially-oriented. In the tunica adventitia, collagen is fibrillar and is present in both transverse and longitudinal planes, suggesting its diagonal distribution. In the SFA near the EEL, collagen fibers follow the longitudinal elastic fibers, and the breaks in the EEL are densely populated with them.

Figure 10:

Representative transverse and longitudinal α-SMA-stained images of the descending thoracic aorta (TA, top) and the superficial femoral artery (SFA, bottom) of a 14-year-old and 69-year-old subjects, demonstrating the differences in smooth muscle actin (brown) structure. Smooth muscle cells (SMCs) are homogeneously distributed through the medial layer of the TA and the SFA, and appear elongated circumferentially. In the older artery, medial SMCs are smaller and more circular, especially closer to the adventitia. Young arteries lack cells expressing α-SMA in their tunica adventitia, while the older specimens contain a substantial amount of these cells. Note the extensive vasa vasorum in the adventitial layer of both arteries and their higher prevalence in older specimens. Also note that cells in the thickened intima of the older specimen express smooth muscle actin, and these cells appear longitudinally-oriented.

Figure 11:

Representative transverse and longitudinal Movat-stained images of the descending thoracic aorta (TA, top) and the superficial femoral artery (SFA, bottom) of a 14-year-old and 69-year-old subjects, demonstrating the differences in glycosaminoglycans (GAGs, greenish-gray). In the TA, GAGs are located between the elastic lamellae and in the thickened intima. In the SFA, GAGs are almost absent in the young artery and are located between the medial SMCs and in the vicinity of the internal elastic lamina in the old specimen. Note that the adventitia of old TAs and SFAs also contains GAGs, although in smaller quantities than the other two arterial layers.

Figure 12:

Thicknesses of the tunica intima (A) and media (B), and densities of elastin (C, D), collagen (E, F), SMCs (G,H), and GAGs (I) in the descending thoracic aorta (TA, red) and the superficial femoral artery (SFA, blue) specimens. Panels (C, E, G, I) plot densities for the entire arterial wall, while (D, F, H) are for the media and the EEL separately. Circles and lines represent experimental data and linear regression fits, respectively, and p-values indicate the statistical significance of the Pearson correlation between age and each variable. Solid circles are measurements on the transverse sections, while hollow circles are data from the longitudinal view.

Tunica intima of both TAs and SFAs thickened faster than their tunica media (Figure 12, A–B). In the TA, intimal layer thickness measured on the transverse sections increased with age 7.6-fold (r = 0.67, p < 0.01), while the medial layer thickened only 1.5-fold (r = 0.58, p < 0.01). When assessed using the longitudinal sections, these thicknesses increased 23.9-fold (r = 0.68, p < 0.01) for the intima, and 1.1-fold (p = 0.05) for the media. In the SFA, intimal layer thickness measured on transverse sections increased with age 9.2-fold (r = 0.67, p < 0.01), while change in the medial layer thickness (526 ± 80μm in young, and 625 ± 200μm in old SFAs) was not statistically significant (p = 0.8). When assessed using the longitudinal sections, both intimal and medial SFA thicknesses increased significantly with age (p < 0.01): 8-fold (r = 061) for the intima, and 1.5-fold (r = 0.57) for the media.

In the TA, elastin formed 3-dimensional sheets throughout the tunica media, while in the SFA it was organized in the form of longitudinal elastic fibers in the EEL, an IEL sheet, and small isolated fragments scattered throughout the tunica media (Figure 8 and supplemental figures 3–6). Elastic fibers were also present in the adventitia of both TAs and SFAs, and they appeared to be oriented diagonally. With aging, the elastic fibers and lamellae degraded and fragmented in both TAs and SFAs, but the TA continued to contain significantly more elastin than the SFA across all ages (Figure 12, C). Transverse sections of the TA and SFA showed 10 ± 30% and 42 ± 50% higher elastin density than the longitudinal sections. The overall density of elastin in the TA decreased with age from 31 – 34% to 13 – 15% (r = −0.63 transverse, r = −0.66 longitudinal, both p < 0.01). In the SFA, it decreased from 9 – 11% to 4% (r = − 0.61 transverse, r = −0.58 longitudinal, both p < 0.01). Interestingly, the EEL of the SFA had similar elastin density as the tunica media of the TA (Figure 12, D) when evaluated using both transverse (SFA: 45 → 19, TA: 45 → 23% with age) and longitudinal (SFA: 49 → 27%, TA: 41 → 21% with age) sections.

Collagen (Figure 9) was present throughout the TA and the SFA wall. Transverse sections of the TA and SFA showed 21 ± 50% and 18 ± 50% higher collagen density than their longitudinal sections. Overall, collagen density (Figure 12, E) remained constant with age in both arteries when assessed using both transverse (p ≥ 0.70) and longitudinal images (p ≥ 0.11) and occupied 14 – 16% of the TA and 22 – 24% of the SFA sections. In the tunica media, older SFAs had significantly more collagen than young arteries (transverse: 22% vs 11%, r = 0.48, and longitudinal: 31% vs 13%, r = 0.39, both p ≤ 0.04), and this collagen was concentrated around the smooth muscle cells (SMCs). In the TA, medial collagen was primarily between the elastic lamellae, and its density stayed relatively constant with age at 13 – 14% (p = 0.48 transverse and p = 0.79 longitudinal, Figure 12, F). In the EEL of the SFA, collagen fibers appeared to follow the same path and pattern as the elastic fibers. Some SFA specimens had breaks in the EEL (Figure 8, a zoomed-in view of the longitudinal strip), which appeared to be filled with the fibrillar collagen that followed the direction of the elastic fibers (Figure 9, zoomed-in view of the longitudinal strip). In the adventitia of both TAs and SFAs, collagen appeared in the form of fibers that were observed in both transverse and longitudinal views, suggesting their diagonal orientation. Collagen was also present in the thickened intima of both TAs and SFAs at ~14% density.

Smooth muscle actin-positive cells (Figure 10) were present in the medial layer of both TAs and SFAs, and were primarily circumferentially-oriented. Further in the text we will refer to these medial cells as SMCs, although fibroblasts and myofibroblasts (that are often found in the adventitia and thickened intima) may also stain positive for α-SMA[58–61]. In young subjects, medial SMCs were more elongated and homogenously distributed, while in older arteries, SMCs appeared smaller and had a more circular shape, particularly closer to the adventitial layer in the SFA (Figure 10, zoomed-in view of the SFA transverse section). In the adventitia of young TAs and SFAs, α-SMA staining was sparse, but older arteries contained substantial vasa vasorum with α-SMA positive cells, and the size of these vessels appeared larger in the TA specimens. Thickened intima of older arteries also appeared to contain α-SMA positive cells that were longitudinally-oriented. The density of SMCs in young TAs was 58 ± 20% higher on the transverse sections than on the longitudinal sections, but this proportion dropped to 19 ± 20% in old TAs. SFAs of all ages had a similar density of SMCs in both transverse and longitudinal views. The density of SMCs in the entire TA wall (Figure 12, G) decreased with age from 20 ± 5% to 16 ± 6% (r = −0.48, p = 0.02) when measured on the transverse sections, and stayed relatively constant at 13 ± 3% (p = 0.27) when assessed using the longitudinal view. In the SFA, the overall SMC density decreased with age from 24 – 25% to 19 – 20% (transverse: r = −0.48, p = 0.01, longitudinal: r = −0.38, p = 0.05). In the TA, medial SMCs were located between the elastic lamellae, and their density remained mainly unchanged with age at 18 – 20% (transverse p = 0.24, longitudinal p = 0.56, Figure 12, H). In the SFA, medial SMC density decreased with age from 36 – 37% to 25 – 28% (transverse: r = −0.52, longitudinal r = −0.46, both p ≤ 0.02).

GAGs (Figure 11) in the TA were present between the elastic lamellae and in the thickened intima. Their amount increased with age, and the distribution became more nonuniform. The overall density of GAGs remained mostly unchanged at 6 ± 3% (p = 0.46) when assessed using the transverse sections, but increased from 4 ± 2% to 11 ± 4% (r = 0.66, p < 0.01) when using the longitudinal view. In young SFAs, GAGs were almost absent (~1%), but their amount increased sharply in older arteries reaching 5 – 6% (transverse: r = 0.66, longitudinal: r = 0.52, both p < 0.01). In older SFAs, GAGs were primarily located between the SMCs in the tunica media, along the collagen fibers in the adventitia, in the thickened intima, and in the immediate vicinity of the IEL.

4. DISCUSSION

Elastic and muscular arteries operate in different biomechanical environments and have a different structure, mechanical properties, and the ability to adapt to aging[30,62–68]. While it is practical to assess human artery behavior using the in vivo techniques[19,22–27], these measurements rely on surrogates of arterial stiffness assessed using pulse wave velocity or distensibility, that are limited to the physiologic range, dependent on the residual stresses, and therefore cannot reliably estimate the intrinsic mechanical properties and physiologic intramural stresses, stretches, and the elastic strain energy[32–38]. This brings into question some of the in vivo reported results, such as lack of stiffening (or even increase in compliance) of muscular arteries, or a drastic reduction in elastic artery compliance with aging[19,22,24,26–28]. The ex vivo evaluation allows to circumvent these issues and study the intrinsic arterial characteristics, but very few studies were done using tissues from the same human subjects[12], and none that we are aware of compared the two major types of arteries across a wide range of ages. The focus of the current work was to perform this analysis using biaxial mechanical testing, constitutive modeling, and structural evaluation of the two commonly repaired human arteries: the elastic descending thoracic aorta, and the muscular superficial femoral artery. Contrasting their intrinsic mechanical behavior with the characteristics that are typically measured in vivo[19,22–24], allowed gaining additional insight into their differing physiology[30,31], which may help develop artery-specific repair materials and devices.

The main physiologic function of the elastic TA is to act as a buffering chamber behind the heart, storing elastic energy during systole, and returning it during diastole, which ensures a nearly continuous blood flow[6,8,9]. The muscular SFA distributes blood from the aorta to the tissues of the lower limb, while reducing arterial kinking and bending during locomotion[17,69,70]. To accommodate these functional differences, the TA and SFA have distinctly different structures [48] and mechanical properties, and they adapt differently to aging.

Our study demonstrates that structurally, both young TAs and SFAs had a thin intimal layer, but the tunica media of the TA was 2.2-fold thicker than the SFA. In the TA, the medial layer consisted of 3-dimensional elastic lamellae with the sandwiched collagen, primarily circumferential SMCs, GAGs, and radial elastic fibers that formed interlamellar units[7,71–74]. Conversely, tunica media of the SFA lacked GAGs, and contained mainly circumferentially-oriented SMCs surrounded by collagen, while the elastin was sparse and organized primarily in the form of longitudinal fibers in the EEL and a single (or sometimes double) 3-dimensional IEL sheet. While the SFA had significantly less elastin than the TA overall, its density in the EEL was similar to that of the TA tunica media, and subjects typically had consistently high and low elastin contents in both arteries. The adventitial layer of the TA and SFA contained diagonally-oriented collagen fibers, intermixed with scarce elastic fibers. The structural differences between young TAs and SFAs were accompanied by their morphometric differences, with TA being 37% thicker, 2.8-fold wider, and producing larger circumferential and longitudinal opening angles compared with the SFA. Mechanically, young TAs were intrinsically isotropic and had similar physiologic stresses in both circumferential and longitudinal directions, while the SFAs were more compliant longitudinally during the biaxial test, and had a higher longitudinal physiologic stress. Over the cardiac cycle, larger TAs stretched 4.7-fold more than the smaller SFAs and stored 8-times more elastic energy, which is consistent with their Windkessel function.

Aging affected the microstructure, morphometry, and the mechanical and physiologic behaviors of both arteries in all directions. The elastic fibers and lamellae degraded and fragmented[75], which along with the thickening of the wall (likely due to the accumulation of GAGs), resulted in the decrease in elastin density. TAs that initially had 3-fold more elastin than the SFAs, were affected to a lesser degree, with older TAs having 5-fold more elastin than the older SFAs. Similar to the previous reports [76,77], degradation of elastin was followed by the accumulation of collagen, but despite the increase in the total amount, its density remained relatively constant with age and was 78% higher in the SFA than in the TA. The overall density of the SMCs decreased in both arteries but remained 11% higher in the SFA across all ages. Similar to the overall SMC and collagen density, the medial densities of SMC and collagen stayed relatively constant in the TA. In the SFA they decreased and increased, respectively, suggesting a decrease in collagen density and an increase in smooth muscle actin density in other layers of the SFA wall. Specifically, the adventitia of older arteries contained a significantly higher amount of α-SMA positive cells than younger specimens, although those can also include fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in addition to SMCs that may also stain positive for α-SMA. At the border of media and adventitia, these cells had a more round shape, potentially suggesting a more synthetic phenotype associated with migration, growth, and proteosynthesis[78,79] that may contribute to vascular disease in older arteries. The adventitial layer of these vessels also contained a significant amount of vasa vasorum that stained positive for α-SMA, and this agrees well with prior studies[80]. Vasa vasorum is a network of smaller blood vessels that supply the arterial wall and is known to play an important role in arterial pathophysiology[81] through the “outside-in” mechanism of arterial inflammation[81,82]. Though commonly attributed to larger arteries with thicker walls[83], vasa vasorum has previously been described in smaller coronary arteries[84], so its presence in the SFA is not surprising. Likewise, older arteries contained a significant amount of longitudinally-oriented α-SMA positive cells in the thickened intima, possibly suggesting the presence of myofibroblasts involved in tissue repair[58,59,61,82,85] or the development of atherosclerosis[86,87].

In addition to changes in elastin, collagen, and SMCs with age, we have also observed a two-fold increase in GAG density in the TA, and almost a 4-fold GAG increase in the SFA. GAGs sequester water and are thought to contribute to the residual stresses in the arterial wall[88–91]. Their accumulation in the aorta is thought to increase the Donnan swelling pressure between the elastic lamellae, thereby contributing to aortic dissection[90,92]. In the older SFAs, GAGs were observed in the tunica media between the SMCs and at the IEL border (especially in between the doubling IEL, Figure 11), potentially contributing to commonly observed arterial dissections during angioplasty. Latter also agrees with a previous study investigating the inelastic characteristics of human femoropopliteal arteries[47] under supraphysiologic loads that showed damage propagation between the medial SMCs and along the IEL border.

Structural adaptations to aging resulted in changes to the intrinsic mechanical properties and the arterial morphometry, which in turn affected the physiologic arterial characteristics. The intrinsic stress-stretch responses of both TAs and SFAs became more nonlinear, likely due to the degradation of elastin and deposition of collagen[4]. However, despite collagen and GAG accumulation in the TA interlamellar space, TA specimens preserved their circumferential compliance but stiffened longitudinally. Conversely, the SFA stiffened in both directions, but the older arteries were still 1.5-fold more compliant longitudinally than circumferentially, which is in agreement with prior results[32,44].

Morphometrically, both the TAs and the SFAs thickened and widened with age. In line with the previous in vivo data[19,23], we have also observed that the physiologic radii increased faster with age in elastic TAs compared with the muscular SFAs, and the proportion of the inner radii (TA/SFA) increased from 3-fold in the young to 4-fold in the old subjects. Interestingly, the reverse was observed for the load-free radii. Specifically, in young subjects, the inner unloaded radius of the TA was 3.5-fold larger than that of the SFA, but in older subjects, this value decreased to 2.5-fold. This discrepancy demonstrates the importance of ex vivo analysis that can glean additional insights into the arterial physiology. Indeed, since the elastic TA maintained its intrinsic circumferential compliance, while the SFA stiffened, the aorta was able to stretch more under the physiologic load, creating an impression of faster widening compared with the muscular SFA[23]. In both arteries, the remodeling occurred outward, with the outer in vivo radius increasing faster than the inner radius. This result is consistent with previous studies of compensatory remodeling[30,64,93–98], and may illustrate the attempts of the artery to maintain shear stress and intramural circumferential mechanical stresses near the homeostatic targets as the arteries intrinsically stiffen with age and compensate by increasing thickness and outer radius.

In terms of the residual stresses[99,100], both the circumferential and the longitudinal opening angles of the TA stayed constant with age, suggesting that growth and remodeling did not result in additional circumferential or longitudinal residual stresses in the aorta. Nevertheless, the faster increase in the thickness of the opened TA ring compared with that of the load-free ring, suggests an increase in residual radial compressive stresses, which may, in turn, contribute to the increase in interlamellar swelling pressure[88,90,101] due to the accumulation of collagen and GAGs. In the SFA, the residual stresses changed in all three principal directions. The longitudinal and the circumferential opening angles increased with age, and so did the radial compression. Changes in the longitudinal opening angle were primarily related to degradation and fragmentation of longitudinal elastic fibers in the EEL. In healthy young SFAs, these elastic fibers are under significant tension[102–104], which causes the axial strip to bend intima outward[32,44]. Degradation and fragmentation of these elastic fibers with age resulted in flatter axial strips with larger longitudinal opening angles, which agrees with previous observations[32]. The increase in the circumferential opening angle may be a consequence of SFA diameter remodeling to a new configuration, a change in SMC tone[105] and phenotype, or the accumulation of collagen and GAGs that also contribute to the residual radial compression.

Perhaps the most significant insight into TA and SFA physiology was provided by the analysis of physiologic stress-stretch state that accounted for the intrinsic mechanical properties, changes in arterial morphometry, and residual stresses with age. Our data demonstrate that the longitudinal physiologic stresses decreased with age in both arteries, dropping 5.4-fold in the TA and 6.7-fold in the SFA. The reduction in the circumferential physiologic stress was much less pronounced and was not statistically significant for the TA. Our previous study[33] demonstrated a similar trend but was able to reach statistical significance, perhaps due to the larger sample size (n=76). On average, TAs experienced 2.3-fold higher circumferential physiologic stresses than the SFAs, and the values (98–83 kPa for the TA and 42–36 kPa for the SFA) agree well with the previous reports (90–72 kPa for the TA[33] and 48–32 kPa for the SFA[32]). Longitudinally, young SFAs experienced 1.7-fold higher physiologic stresses than the TAs, and this value decreased to 1.4-fold in older subjects. These results are also in line with the previous observations[32,33], and are likely stemming from the reduction of longitudinal pre-stretch with age[14,41].

Over the cardiac cycle, TAs experienced higher stretches compared with the SFAs. Cardiac cycle stretch in the TA decreased with age from 14% to 6%, but in the SFA it decreased by only 1%. Both of these results agree well with the in vivo observations[19–24,26,27,106–108] reporting a drop in elastic artery distensibility but a relatively constant muscular artery distensibility with age. The higher cardiac cycle stretch in the TA was associated with the higher stored elastic energy available for pulsation, supporting the aortic Windkessel function as an elastic chamber behind the heart[8,9]. Finally, the analysis of linearized circumferential stiffness demonstrated that the SFAs were 36% stiffer than the TAs, and that the physiologic stiffness increased with age in both arteries, confirming previous observations[32,33,38]. Importantly, these results demonstrate that the observed drop in aortic distensibility with age (Figure 7A and the in vivo studies[19,22,24,26–28]) is not due to the loss of intrinsic tissue compliance. And likewise, a near-constant circumferential physiologic SFA distensibility that is often reported by the in vivo studies[19,22,24,26–28] does not imply that the SFA preserves its intrinsic compliance with age. Instead, both results are the product of complex interactions between the intrinsic tissue mechanical behavior (i.e., Figure 4 and Figure 5), morphometry, and the residual stresses.

While these are the important distinctions between elastic and muscular arteries that can be learned from the ex vivo arterial analysis to clarify sometimes puzzling in vivo findings[24,26,109], our study needs to be considered in the context of its limitations. First, while we compared our results with the in vivo analyses, we have performed our experiments ex vivo and have determined the in vivo physiologic stress-stretch variables through constitutive modeling. Second, though TA and SFA represent the typical elastic and muscular arteries, the results could be different for other arterial beds or arteries of mixed type. Third, we have not accounted for the effects of perivascular tethering[110], but the good agreement of our results with the in vivo diameter and cardiac stretch measurements[23,108] indirectly indicates that this effect may be relatively small, although it can affect the calculated physiologic stresses. Fourth, we have measured the SFA longitudinal pre-stretch, but have used TA longitudinal pre-stretch that was obtained for the abdominal aorta by a different study[41]. In the absence of measured longitudinal pre-stretch, one approach is to determine it as the decoupling pre-stretch at which the axial force is independent of the internal pressure[33,111–114]. Though this is tempting, our previous studies[32,33] demonstrated that the decoupling pre-stretch is 11% higher than the measured pre-stretch for both the SFA and the TA. The use of the decoupling pre-stretch instead of the values utilized in this study would have produced consistent differences in TA and SFA physiologic calculations, and therefore would not have significantly influenced the conclusions. Fifth, we have used the same blood pressure values to calculate physiologic variables in all arteries, while many older subjects could have been hypertensive. Though this is unlikely to affect the comparison of the TA to the SFA, it may have influenced the calculation of intramural stresses. Unfortunately, blood pressure measurements were not available for our donors. Sixth, all arteries were tested as a whole, without separating layers. Layer separation can be done for older arteries that contain increased amounts of GAGs that contribute to easier tissue delamination, but this process is extremely challenging for younger and healthier tissues. Furthermore, layer separation disturbs tissue integrity, so the sum of the parts may not necessarily equal the behavior of the whole. Lastly, our current sample size did not allow us to consider the effects of gender and cardiovascular risk factors (although they are provided for all specimens in Appendix 5.1). Though age has a dominant effect of arterial mechanics[46,115–117], other risk factors may also play significant roles[118–123], and need to be considered in future analyses. While these limitations are being addressed, the presented data allow a better understanding of the morphometric, mechanical, structural, and physiologic differences between human elastic and muscular arteries in the context of aging. These data can guide growth and remodeling frameworks describing vascular aging, and help develop artery-specific repair materials and devices.

Supplementary Material

6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported in part by the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers HL125736 and HL147128, and by the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command (USAMRMC) under award number W81XWH-16-2-0034, Log 14361001. The authors also wish to acknowledge Live On Nebraska for their help and support, and thank donors and their families for making this study possible.

5. APPENDIX

5.1. Subject demographics and risk factors.

| Subject number | Age | Gender Male / Female | BMI | Never/Current/Former smoker | HTN | DM | Dyslipidemia | CAD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 13 | F | 19.7 | Never | No | No | No | No |

| 2 | 13 | F | 22.5 | Never | No | No | No | No |

| 3 | 14 | M | 22.1 | Never | No | No | No | No |

| 4 | 17 | F | 17.3 | Never | Yes | No | No | No |

| 5 | 19 | M | 40.6 | Never | No | No | No | No |

| 6 | 22 | M | 29.5 | Never | No | No | No | No |

| 7 | 23 | M | 24.6 | Current | No | No | No | No |

| 8 | 26 | M | 22.9 | Never | No | No | No | No |

| 9 | 28 | M | 28.2 | Never | No | No | No | No |

| 10 | 31 | M | 28.3 | Current | No | No | No | No |

| 11 | 38 | F | 53.8 | Never | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| 12 | 39 | M | 32.1 | Current | No | No | No | No |

| 13 | 43 | M | 21.9 | Never | No | No | No | No |

| 14 | 44 | M | 33.2 | Never | Yes | No | No | No |

| 15 | 47 | F | 46.6 | Current | No | No | No | Yes |

| 16 | 47 | M | 24.7 | Never | No | No | No | No |

| 17 | 49 | M | 50.7 | Never | Yes | No | No | No |

| 18 | 51 | M | 26.9 | Current | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| 19 | 51 | M | 29.1 | Current | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| 20 | 54 | M | 40.2 | Never | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| 21 | 55 | M | 40.1 | Current | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| 22 | 57 | F | 44.4 | Current | No | No | No | No |

| 23 | 59 | M | 38.5 | Former | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| 24 | 59 | M | 25.4 | Never | Yes | No | No | No |

| 25 | 64 | M | 19.5 | Never | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| 26 | 69 | M | 31.3 | Former | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| 27 | 73 | M | 28.1 | Current | Yes | Yes | No | No |

BMI = body mass index, HTN = hypertension, DM = diabetes mellitus, CAD = coronary artery disease.

5.2. Constitutive model parameters describing the intrinsic mechanical behavior of the descending thoracic aortas (TA) and the superficial femoral arteries (SFA). The R2 shows the goodness of fit in the longitudinal (z) and circumferential (θ) directions.

| Subject Number | TA | SFA | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cgr, kPa | ,kPa | ,kPa | ,kPa | γ° | Cgr, kPa | ,kPa | ,kPa | ,kPa | γ° | |||||||||||

| 1 | 19.50 | 0.33 | 1.93 | 30.66 | 0.00 | 17.77 | 0.29 | 38.59 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.55 | 30.18 | 0.00 | 1.57 | 0.98 | 2.73 | 0.90 | 59.20 | 1.00 | 0.97 |

| 2 | 15.05 | 2.24 | 0.00 | 26.01 | 0.00 | 17.51 | 0.19 | 34.68 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 12.83 | 11.32 | 0.38 | 0.69 | 6.30 | 7.98 | 3.33 | 70.13 | 0.98 | 0.91 |

| 3 | 28.08 | 7.17 | 0.00 | 36.71 | 0.00 | 21.23 | 0.35 | 37.07 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 17.82 | 2.67 | 0.00 | 8.71 | 4.12 | 7.98 | 0.00 | 21.97 | 0.94 | 0.94 |

| 4 | 10.91 | 24.93 | 0.01 | 19.26 | 0.04 | 18.97 | 0.44 | 53.60 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 6.15 | 14.54 | 0.40 | 3.45 | 9.52 | 7.16 | 2.81 | 56.52 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 5 | 13.13 | 14.25 | 0.08 | 32.58 | 0.00 | 24.36 | 0.17 | 40.21 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 10.41 | 20.40 | 0.00 | 1.69 | 6.68 | 3.57 | 5.15 | 61.59 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 6 | 9.26 | 17.30 | 0.00 | 28.67 | 0.00 | 26.74 | 0.18 | 47.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 9.57 | 14.28 | 0.19 | 1.16 | 2.15 | 0.85 | 3.28 | 60.49 | 0.98 | 0.95 |

| 7 | 42.65 | 0.75 | 7.29 | 32.42 | 0.00 | 5.18 | 4.28 | 37.06 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 11.88 | 4.14 | 3.02 | 4.46 | 10.90 | 0.90 | 11.53 | 59.41 | 0.81 | 0.98 |

| 8 | 6.87 | 11.08 | 0.16 | 32.72 | 0.00 | 23.78 | 0.35 | 40.61 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 14.52 | 16.00 | 0.33 | 3.36 | 1.97 | 1.49 | 2.78 | 55.08 | 0.99 | 0.98 |

| 9 | 8.17 | 13.05 | 0.08 | 32.22 | 0.00 | 23.71 | 0.23 | 39.62 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 3.88 | 12.03 | 0.33 | 0.77 | 7.01 | 4.35 | 3.36 | 58.72 | 1.00 | 0.99 |

| 10 | 14.24 | 0.00 | 13.35 | 15.44 | 0.17 | 16.43 | 0.99 | 31.59 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.01 | 17.01 | 0.08 | 0.17 | 4.36 | 4.46 | 0.92 | 62.30 | 0.99 | 0.96 |

| 11 | 11.74 | 11.52 | 0.63 | 26.71 | 0.03 | 15.92 | 0.84 | 40.37 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 34.00 | 0.00 | 37.21 | 11.99 | 11.66 | 19.56 | 55.44 | 0.79 | 0.95 |

| 12 | 18.23 | 0.05 | 11.56 | 18.49 | 0.21 | 7.49 | 3.02 | 31.92 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 7.80 | 13.03 | 1.06 | 0.78 | 9.12 | 6.37 | 4.35 | 60.90 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| 13 | 11.68 | 17.01 | 0.12 | 18.80 | 0.00 | 16.72 | 0.75 | 41.98 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 3.19 | 13.41 | 0.84 | 0.73 | 2.80 | 4.18 | 1.91 | 50.91 | 0.97 | 0.96 |

| 14 | 37.70 | 8.00 | 5.28 | 14.95 | 0.73 | 5.55 | 5.75 | 37.35 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.02 | 40.76 | 0.00 | 38.38 | 18.23 | 7.90 | 17.84 | 56.89 | 0.97 | 0.96 |

| 15 | 18.20 | 16.85 | 1.91 | 14.82 | 0.31 | 6.48 | 3.42 | 38.87 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 13.37 | 3.58 | 5.67 | 6.53 | 7.98 | 3.07 | 10.21 | 51.76 | 0.99 | 1.00 |

| 16 | 14.25 | 11.22 | 2.29 | 23.05 | 0.79 | 6.36 | 5.76 | 38.86 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 9.76 | 5.20 | 1.79 | 19.99 | 18.08 | 1.40 | 17.21 | 50.41 | 0.96 | 0.94 |

| 17 | 4.52 | 0.98 | 10.99 | 43.47 | 0.00 | 36.80 | 1.09 | 32.02 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 14.30 | 6.23 | 7.74 | 29.16 | 36.45 | 4.25 | 39.80 | 53.23 | 0.99 | 1.00 |

| 18 | 5.78 | 0.79 | 10.78 | 21.78 | 0.29 | 9.46 | 2.50 | 37.50 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.93 | 19.44 | 1.31 | 2.36 | 2.80 | 1.26 | 5.36 | 41.37 | 0.99 | 0.98 |

| 19 | 49.69 | 7.51 | 17.44 | 8.42 | 6.15 | 2.32 | 29.27 | 38.64 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.00 | 86.55 | 2.01 | 86.79 | 36.51 | 13.64 | 34.72 | 43.19 | 0.96 | 0.97 |

| 20 | 16.55 | 3.63 | 4.47 | 20.39 | 0.35 | 4.33 | 4.53 | 37.88 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 6.26 | 14.86 | 0.00 | 13.11 | 38.58 | 1.42 | 41.15 | 61.88 | 0.96 | 0.99 |

| 21 | 14.10 | 6.49 | 3.75 | 17.65 | 0.00 | 12.87 | 2.48 | 38.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.01 | 38.01 | 0.00 | 12.27 | 38.38 | 10.74 | 30.96 | 61.17 | 0.98 | 0.99 |

| 22 | 24.78 | 1.26 | 16.59 | 22.12 | 0.54 | 7.21 | 7.89 | 31.56 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.72 | 18.67 | 0.00 | 3.93 | 3.91 | 9.74 | 2.43 | 54.26 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| 23 | 12.26 | 17.83 | 1.94 | 34.63 | 0.11 | 29.96 | 2.18 | 38.07 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 7.41 | 10.78 | 2.42 | 3.67 | 11.34 | 1.43 | 9.89 | 45.94 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| 24 | 30.76 | 12.19 | 25.11 | 29.29 | 1.44 | 5.31 | 27.95 | 35.08 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 16.09 | 6.53 | 9.50 | 27.92 | 18.55 | 29.56 | 55.53 | 0.86 | 0.88 |

| 25 | 12.68 | 3.64 | 5.51 | 20.91 | 0.66 | 12.39 | 3.82 | 35.96 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 4.85 | 17.56 | 3.55 | 2.30 | 2.54 | 3.04 | 3.93 | 52.45 | 0.99 | 0.98 |

| 26 | 27.46 | 9.35 | 8.62 | 24.96 | 0.24 | 4.82 | 9.53 | 37.09 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 8.70 | 31.81 | 4.62 | 49.79 | 45.61 | 12.52 | 63.52 | 58.54 | 0.96 | 0.99 |

| 27 | 20.27 | 4.36 | 19.93 | 10.29 | 2.58 | 1.68 | 24.12 | 34.01 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 23.35 | 0.87 | 52.70 | 27.86 | 8.47 | 29.23 | 55.61 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

7 REFERENCES

- [1].Humphrey JD, Harrison DG, Figueroa CA, Lacolley P, Laurent S, Central Artery stiffness in hypertension and aging a problem with cause and consequence, Circ. Res (2016). 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.307722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Shirwany NA, Zou M, Arterial stiffness: a brief review, Acta Pharmacol. Sin 31 (2010) 1267–1276. 10.1038/aps.2010.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Fung YC, Liu SQ, Change of residual strains in arteries due to hypertrophy caused by aortic constriction., Circ. Res 65 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zieman SJ, Melenovsky V, Kass DA, Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and therapy of arterial stiffness., Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 25 (2005) 932–43. 10.1161/01.ATV.0000160548.78317.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Cocciolone AJ, Hawes JZ, Staiculescu MC, Johnson EO, Murshed M, Wagenseil JE, Elastin, arterial mechanics, and cardiovascular disease, Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol 315 (2018) ajpheart.00087.2018. 10.1152/ajpheart.00087.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Gasser TC, Aorta, Biomech. Living Organs (2017) 169–191. 10.1016/B978-0-12-804009-6.00008-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [7].O’Connell MK, Murthy S, Phan S, Xu C, Buchanan J, Spilker R, Dalman RL, Zarins CK, Denk W, Taylor CA, The three-dimensional micro- and nanostructure of the aortic medial lamellar unit measured using 3D confocal and electron microscopy imaging, Matrix Biol. 27 (2008) 171–181. 10.1016/J.MATBIO.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Belz GG, Elastic properties and Windkessel function of the human aorta, Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther 9 (1995) 73–83. 10.1007/BF00877747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Westerhof N, Lankhaar J-WW, Westerhof BE, The arterial windkessel, Med. Biol. Eng. Comput 47 (2009) 131–141. 10.1007/s11517-008-0359-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kamenskiy A, Aylward P, Desyatova A, DeVries M, Wichman C, MacTaggart J, Endovascular Repair of Blunt Thoracic Aortic Trauma is Associated With Increased Left Ventricular Mass, Hypertension, and Off-target Aortic Remodeling, Ann. Surg XX (2020) 1 10.1097/sla.0000000000003768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Humphrey JD, Cardiovascular Solid Mechanics, Springer; New York, New York, NY, 2002. 10.1007/978-0-387-21576-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [12].V Kamenskiy A, Dzenis YA, Kazmi SAJ, Pemberton MA, Pipinos III, Phillips NY, Herber K, Woodford T, Bowen RE, Lomneth CS, MacTaggart JN, Biaxial mechanical properties of the human thoracic and abdominal aorta, common carotid, subclavian, renal and common iliac arteries., Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol 13 (2014) 1341–59. 10.1007/s10237-014-0576-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Sokolis DP, A passive strain-energy function for elastic and muscular arteries: correlation of material parameters with histological data., Med. Biol. Eng. Comput 48 (2010) 507–518. 10.1007/s11517-010-0598-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kamenskiy A, Seas A, Bowen G, Deegan P, Desyatova A, Bohlim N, Poulson W, Mactaggart J, In situ longitudinal pre-stretch in the human femoropopliteal artery, Acta Biomater. 32 (2016) 231–237. 10.1016/j.actbio.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Palatini P, Casiglia E, Gasowski J, Głuszek J, Jankowski P, Narkiewicz K, Saladini F, Stolarz-Skrzypek K, Tikhonoff V, Van Bortel L, Wojciechowska W, Kawecka-Jaszcz K, Arterial stiffness, central hemodynamics, and cardiovascular risk in hypertension, Vasc. Health Risk Manag 7 (2011) 725–739. 10.2147/VHRM.S25270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Desyatova A, Mactaggart J, Romarowski R, Poulson W, Conti M, Kamenskiy A, Effect of aging on mechanical stresses, deformations, and hemodynamics in human femoropopliteal artery due to limb flexion, Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol 17 (2017). 10.1007/s10237-017-0953-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].MacTaggart JN, Phillips NY, Lomneth CS, Pipinos III, Bowen R, Timothy Baxter B, Johanning J, Matthew Longo G, Desyatova AS, Moulton MJ, Dzenis YA, Kamenskiy AV, Three-dimensional bending, torsion and axial compression of the femoropopliteal artery during limb flexion, J. Biomech 47 (2014) 2249–2256. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Humphrey JD, Eberth JF, Dye WW, Gleason RL, Fundamental role of axial stress in compensatory adaptations by arteries, J. Biomech 42 (2009) 1–8. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bortolotto LA, Hanon O, Franconi G, Boutouyrie P, Legrain S, Girerd X, The aging process modifies the distensibility of elastic but not muscular arteries, Hypertension. 34 (1999) 889–892. 10.1161/01.hyp.34.4.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Leloup AJA, Van Hove CE, Heykers A, Schrijvers DM, De Meyer GRY, Fransen P, Elastic and muscular arteries differ in structure, basal NO production and voltage-gated Ca2+-channels, Front. Physiol 6 (2015). 10.3389/fphys.2015.00375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Cameron JD, Bulpitt CJ, Pinto ES, Rajkumar C, The aging of elastic and muscular arteries: A comparison of diabetic and nondiabetic subjects, Diabetes Care. 26 (2003) 2133–2138. 10.2337/diacare.26.7.2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Boutouyrie P, Laurent S, Benetos A, Girerd XJ, Hoekst APG, Safar ME, Opposing effects of ageing on distal and proximal large arteries in hypertensives, J. Hypertens 10 (1992) S87–S92. 10.1097/00004872-199208001-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kamenskiy A, Miserlis D, Adamson P, Adamson M, Knowles T, Neme J, Koutakis P, Phillips N, Pipinos I, MacTaggart J, Patient demographics and cardiovascular risk factors differentially influence geometric remodeling of the aorta compared with the peripheral arteries, Surgery. (2015). 10.1016/j.surg.2015.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Van Der Heijden-Spek JJ, Staessen JA, Fagard RH, Hoeks AP, Struijker Boudier HA, Van Bortel LM, Effect of age on brachial artery wall properties differs from the aorta and is gender dependent: A population study, Hypertension. 35 (2000) 637–642. 10.1161/01.HYP.35.2.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Mourad J-J, Girerd X, Boutouyrie P, Safar M, Laurent S, Opposite Effects of Remodeling and Hypertrophy on Arterial Compliance in Hypertension, Hypertension. 31 (1998) 529–533. 10.1161/01.HYP.31.1.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ruitenbeek AG, Van Der Cammen TJM, Van Den Meiracker AH, Mattace-Raso FUS, Age and blood pressure levels modify the functional properties of central but not peripheral arteries, Angiology. 59 (2008) 290–295. 10.1177/0003319707305692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Zhang Y, Agnoletti D, Protogerou AD, Topouchian J, Wang J-G, Xu Y, Blacher J, Safar ME, Characteristics of pulse wave velocity in elastic and muscular arteries, J. Hypertens 31 (2013) 554–559. 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32835d4aec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Mitchell GF, Parise H, Benjamin EJ, Larson MG, Keyes MJ, Vita JA, Vasan RS, Levy D, Changes in arterial stiffness and wave reflection with advancing age in healthy men and women: The Framingham Heart Study, Hypertension. 43 (2004) 1239–1245. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000128420.01881.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Mitchell GF, Effects of central arterial aging on the structure and function of the peripheral vasculature: implications for end-organ damage, J. Appl. Physiol 105 (2008) 1652–1660. 10.1152/japplphysiol.90549.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Humphrey JD, Dufresne ER, Schwartz MA, Mechanotransduction and extracellular matrix homeostasis, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 15 (2014) 802–812. 10.1038/nrm3896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Humphrey JD, Vascular adaptation and mechanical homeostasis at tissue, cellular, and sub-cellular levels., Cell Biochem. Biophys 50 (2008) 53–78. 10.1007/s12013-007-9002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Jadidi M, Desyatova A, MacTaggart J, Kamenskiy A, Mechanical stresses associated with flattening of human femoropopliteal artery specimens during planar biaxial testing and their effects on the calculated physiologic stress-stretch state., Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol 18 (2019) 1591–1605. 10.1007/s10237-019-01162-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Jadidi M, Habibnezhad M, Anttila E, Maleckis K, Desyatova A, MacTaggart J, Kamenskiy A, Mechanical and structural changes in human thoracic aortas with age, Acta Biomater. 103 (2020) 172–188. 10.1016/j.actbio.2019.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ferruzzi J, Vorp DA, Humphrey JD, On constitutive descriptors of the biaxial mechanical behaviour of human abdominal aorta and aneurysms, (n.d.). 10.1098/rsif.2010.0299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [35].Sommer G, Regitnig P, Koltringer L, Holzapfel GA, Biaxial mechanical properties of intact and layer-dissected human carotid arteries at physiological and supraphysiological loadings, AJP Hear. Circ. Physiol 298 (2010) H898–H912. 10.1152/ajpheart.00378.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Vande Geest JJP, Sacks MMS, Vorp DA, Age Dependency of the Biaxial Biomechanical Behavior of Human Abdominal Aorta, J. Biomech. Eng 126 (2004) 815 10.1115/1.1824121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Kural MH, Cai M, Tang D, Gwyther T, Zheng J, Billiar KL, Planar biaxial characterization of diseased human coronary and carotid arteries for computational modeling., J. Biomech 45 (2012) 790–8. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Roccabianca S, Figueroa CA, Tellides G, Humphrey JD, Quantification of regional differences in aortic stiffness in the aging human, J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater 29 (2014) 618–634. 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2013.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Wagner HP, Humphrey JD, Differential Passive and Active Biaxial Mechanical Behaviors of Muscular and Elastic Arteries: Basilar Versus Common Carotid, J. Biomech. Eng 133 (2011) 051009 10.1115/1.4003873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Megens RTA, Reitsma S, Schiffers PHM, Hilgers RHP, De Mey JGR, Slaaf DW, Oude Egbrink MGA, Van Zandvoort MAMJ, Two-Photon Microscopy of Vital Murine Elastic and Muscular Arteries Combined Structural and Functional Imaging with Subcellular Resolution, J Vasc Res. 44 (2007) 87–98. 10.1159/000098259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Horný L, Netušil M, Voňavková T, Axial prestretch and circumferential distensibility in biomechanics of abdominal aorta., Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol 13 (2013) 783–799. 10.1007/s10237-013-0534-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Chuong CJ, Fung YC, Residual Stress in Arteries, in: Front. Biomech, Springer; New York, New York, NY, 1986: pp. 117–129. 10.1007/978-1-4612-4866-8_9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Vaishnav RN, Vossoughi J, Estimation of Residual Strains in Aortic Segments, in: Biomed. Eng. II, Elsevier, 1983: pp. 330–333. 10.1016/B978-0-08-030145-7.50078-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Kamenskiy A, Seas A, Deegan P, Poulson W, Anttila E, Sim S, Desyatova A, MacTaggart J, Constitutive description of human femoropopliteal artery aging, Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol 16 (2017) 681–692. 10.1007/s10237-016-0845-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Kamenskiy AV, Pipinos II, Dzenis YA, Lomneth CS, Kazmi S. a J.. Phillips NY, MacTaggart JN, Passive biaxial mechanical properties and in vivo axial pre-stretch of the diseased human femoropopliteal and tibial arteries., Acta Biomater. 10 (2014) 1301–13. 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].V Kamenskiy A, Pipinos II, Dzenis YA, Phillips NY, Desyatova AS, Kitson J, Bowen R, MacTaggart JN, Effects of age on the physiological and mechanical characteristics of human femoropopliteal arteries., Acta Biomater. 11 (2015) 304–13. 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Anttila E, Balzani D, Desyatova A, Deegan P, MacTaggart J, Kamenskiy A, Mechanical damage characterization in human femoropopliteal arteries of different ages, Acta Biomater. 90 (2019) 225–240. 10.1016/J.ACTBIO.2019.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Humphrey JD, Cardiovascular Solid Mechanics: Cells, Tissues, and Organs, Springer, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Keyes JT, Lockwood DR, Utzinger U, Montilla LG, Witte RS, Vande Geest JP, Comparisons of planar and tubular biaxial tensile testing protocols of the same porcine coronary arteries., Ann. Biomed. Eng 41 (2013) 1579–91. 10.1007/s10439-012-0679-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Sommer G, a Holzapfel G, 3D constitutive modeling of the biaxial mechanical response of intact and layer-dissected human carotid arteries., J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater 5 (2012) 116–28. 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Holzapfel GA, Gasser TC, Ogden RW, W OR, A New Constitutive Framework For Arterial Wall Mechanics And A Comparative Study of Material Models, J Elast. 61 (2000) 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Holzapfel GA, Ogden RW, Constitutive modelling of arteries, Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci 466 (2010) 1551–1597. 10.1098/rspa.2010.0058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Tsamis A, Phillippi JA, Koch RG, Pasta S, D’Amore A, Watkins SC, Wagner WR, Gleason TG, Vorp DA, Fiber micro-architecture in the longitudinal-radial and circumferential-radial planes of ascending thoracic aortic aneurysm media, J. Biomech 46 (2013) 2787–2794. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Deplano V, Boufi M, Gariboldi V, Loundou AD, D’Journo XB, Cautela J, Djemli A, Alimi YS, Mechanical characterisation of human ascending aorta dissection, J. Biomech (2019). 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2019.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Bersi MR, Collins MJ, Wilson E, Humphrey JD, Disparate changes in the mechanical properties of murine carotid arteries and aorta in response to chronic infusion of angiotensin-II, Int. J. Adv. Eng. Sci. Appl. Math 4 (2012) 228–240. 10.1007/s12572-012-0052-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Ferruzzi J, Bersi MR, Uman S, Yanagisawa H, Humphrey JD, Decreased elastic energy storage, not increased material stiffness, characterizes central artery dysfunction in fibulin-5 deficiency independent of sex., J. Biomech. Eng 137 (2015) 0310071 10.1115/1.4029431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Ferruzzi J, · Madziva D, · Caulk AW, · Tellides G, Humphrey JD, Compromised mechanical homeostasis in arterial aging and associated cardiovascular consequences, Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol 17 (2018) 1281–1295. 10.1007/s10237-018-1026-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Hinz B, Formation and function of the myofibroblast during tissue repair, J. Invest. Dermatol 127 (2007) 526–537. 10.1038/sj.jid.5700613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Zalewski A, Shi Y, Vascular Myofibroblasts, Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 17 (1997) 417–422. 10.1161/01.ATV.17.3.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Lehman W, Morgan KG, Structure and dynamics of the actin-based smooth muscle contractile and cytoskeletal apparatus, J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil 33 (2012) 461–469. 10.1007/s10974-012-9283-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].and Darby GG, Skalli I,O, Alpha-smooth muscle actin is transiently expressed by myofibroblasts during experimental wound healing - PubMed, Lab Invest. 63 (1990) 21–29. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2197503/ (accessed July 30, 2020). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Bhagavan D, Di Achille P, Humphrey JD, Strongly coupled morphological features of aortic aneurysms drive intraluminal thrombus, Sci. Rep 8 (2018). 10.1038/s41598-018-31637-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Humphrey JD, Stress, strain, and mechanotransduction in cells, J. Biomech. Eng 123 (2001) 638–641. 10.1115/1.1406131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Humphrey JD, Mechanisms of Arterial Remodeling in Hypertension: Coupled Roles of Wall Shear and Intramural Stress, Hypertension. 52 (2008) 195–200. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.103440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Li C, Xu Q, Mechanical stress-initiated signal transduction in vascular smooth muscle cells in vitro and in vivo, Cell. Signal 19 (2007) 881–891. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Chiquet M, Gelman L, Lutz R, Maier S, From mechanotransduction to extracellular matrix gene expression in fibroblasts, Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Cell Res 1793 (2009) 911–920. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Humphrey JD, Milewicz DM, Tellides G, Schwartz MA, Edu MS, Dysfunctional Mechanosensing in Aneurysms: Cellular sensing of a compliant extracellular matrix may be critical in maintaining structural integrity of the aorta, (n.d.). 10.1126/science.1253026. [DOI]

- [68].Caulk AW, Tellides G, Humphrey JD, Vascular mechanobiology, immunobiology, and arterial growth and remodeling, in: Mechanobiol. Heal. Dis, Elsevier, 2018: pp. 215–248. 10.1016/b978-0-12-812952-4.00007-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Poulson W, Kamenskiy A, Seas A, Deegan P, Lomneth C, MacTaggart J, Limb flexion-induced axial compression and bending in human femoropopliteal artery segments., J. Vasc. Surg 67 (2018) 607–613. 10.1016/j.jvs.2017.01.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]