Abstract

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) remains one of the most effective biomedical interventions for the prevention of HIV transmission. However, uptake among populations most impacted by the HIV epidemic remains low. Large-scale awareness and mobilization campaigns have sought to address gaps in knowledge and motivation in order to improve PrEP diffusion. Such campaigns must be cognizant of the historical, physical, and structural contexts in which they exist. In urban contexts, neighborhood segregation has the potential to impact health outcomes and amplify disparities. Therefore, we present novel geospatial approaches to the evaluation of a Chicago-based PrEP messaging campaign (PrEP4Love) in a 2018 cohort of men who have sex with men and transgender women, contextualizing results within the localized infrastructure and public health landscape, and examining associations between geographic location and campaign efficacy. Results revealed notable variance in rates of PrEP uptake associated with campaign exposure by Chicago planning area, which are likely explained by the historical and contemporary impacts of racist structures on physical environment and city infrastructure. Findings have important implications for the evaluation and implementation of future messaging campaigns, which should take the unique historical, structural, and geospatial factors of their particular settings into account in order to achieve maximum impact.

Keywords: Geospatial, PrEP, structural analysis, community context, HIV prevention, advocacy

Introduction

Despite significant progress in HIV prevention and treatment, an estimated 38,739 individuals in the U.S. received an HIV diagnosis in 2017, contributing to the 1.1 million people in the U.S. currently living with HIV.1 Gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM), as well as transgender women (TW), are most heavily impacted by HIV. In 2017, MSM accounted for 70% of new HIV diagnoses overall and for 83% of new diagnoses among men in the same year1,2; similarly, an estimated 14.1% of all TW in the United States are living with HIV.3 Moreover, racial/ethnic intersectional disparities are highly pertinent - Black MSM (BMSM) and Latinx MSM (LMSM) demonstrate disproportionate rates of HIV acquisition, comprising 38% and 29% of new infections among MSM in 2017.1,2,4–6 Even more notably, up to 44% of Black TW are estimated to be living with HIV.7

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is a once-a-day pill effective at preventing HIV when taken adherently, and is one of the most effective biomedical HIV prevention tools available.8–11 However, there have been numerous challenges to widespread uptake of PrEP,12 particularly among marginalized minority groups most impacted by HIV.13 Such disparities point towards a need for interventions which not only account for the full scope of factors influencing HIV prevention and care outcomes, but are appropriately tailored to cultural and community context in order to achieve health equity goals.14,15

Moreover, primary care providers’ awareness, familiarity with prescribing (including having conversations about sexual behavior), and actual experience with prescribing PrEP fall far below that of HIV specialists.16 A 90-site examination of PrEP medical records found that 94% of PrEP conversations are initiated by the patient17, indicating that provider knowledge gaps regarding PrEP place a burden on the patient to be aware of and advocate for their own PrEP eligibility. Thus, improving PrEP uptake requires both provider awareness and training, as well as programming that supports patient self-efficacy. However, these are not the only concerns related to PrEP uptake; there are a host of other multi-level barriers that persist which require ongoing study and intervention to ensure optimal PrEP uptake nationwide.

The impact of structural stigma (racism, homophobia, transphobia, and other forms of discrimination) on health outcomes must be a cornerstone of health equity discussions, particularly within HIV-related health promotion. Often manifested in ways such as resource access inequity, social deprivation, psychosocial trauma, political exclusion, and inadequate access to health services, structural stigma has tangible impacts on health outcomes.18–23 In urban contexts, neighborhood segregation is a form of structural racism with the potential to impact health outcomes through “neighborhood effects”24–28 such as proximity and access to public transit, residential racial segregation, and health service proximity/access by neighborhood.29–33 This pattern holds true in Chicago, where HIV outcomes and other health indicators vary substantially by neighborhood, overwhelmingly and disproportionately impacting predominantly Black, Latinx, and low-SES areas of the city.34–37

In the context of these challenges, we examined the PrEP4Love campaign,38 a PrEP messaging and prevention-advocacy initiative led by the AIDS Foundation of Chicago (AFC) and the Illinois PrEP Working Group (IPWG). PrEP4Love combined educational marketing and community mobilization to promote PrEP in a variety of paid and unpaid locations from bars and healthcare providers to social media, utilizing re-appropriated language common to disease transmission discourse and applied it to sex-positive messages (e.g., “spread tingle” or “transmit love”). PrEP promotional approaches include an informational website, social media, PrEP4Love branded and personalized photographs for sharing, posters, palm cards, coasters, digital and paper advertisements, educational programming, and community mobilization live events with local and national partners designed to facilitate community dialogues and motivate PrEP uptake. Though the PrEP4Love campaign is ongoing in the form of grassroots community outreach and mobilization, including social media, the focus of the current analysis surrounds paid advertisements (Chicago Transit Authority [CTA] advertisements, bar advertisements, and PrEP4Love live events) that occurred before December 2017.

Prior evaluations of the PrEP4Love campaign have provided promising evidence in favor of its efficacy in reducing stigma surrounding PrEP and increasing likelihood of uptake among Chicago young MSM (YMSM) and young TW.38 However, PrEP4Love also represents a novel opportunity to assess a health campaign’s impact through a geospatially-informed health equity lens. Due to PrEP4Love’s focus on reaching priority populations in historically marginalized, segregated, and underserved areas of the city, this study applied a geospatially-informed approach to assessing campaign efficacy. Using an existing Chicago-based cohort of diverse YMSM and TW, we explored associations between exposure to PrEP4Love messaging, health-promoting behaviors related to PrEP, Chicago demographics, and geospatial campaign location. Our findings are discussed with respect to Chicago’s unique structural and historical context and the complex barriers which impede health equity at the city level. In doing so, we leverage social and health system data and present the groundwork for an ecologically-informed approach to evaluating health promotion campaigns.

Methods

Data for this study were collected within RADAR, a longitudinal cohort study in Chicago focused on the individual, dyadic, network, social, and biologic factors that are associated with HIV infection among youth assigned male at birth. Study participants complete an initial assessment that includes a network survey, an individual-level psychosocial survey, and collection of biological samples for HIV/STI testing. Follow-up visits occur every six months for the duration of the study. Data for this manuscript came from study participants who attended a visit between June 6, 2017 and April 27, 2018 (after the conclusion of the PrEP4Love paid advertising phase), were HIV-negative, and were administered the PrEP4Love items, resulting in an analytic sample of 700. For participants who completed the survey at multiple visits, only their first survey was included.

Campaign implementation

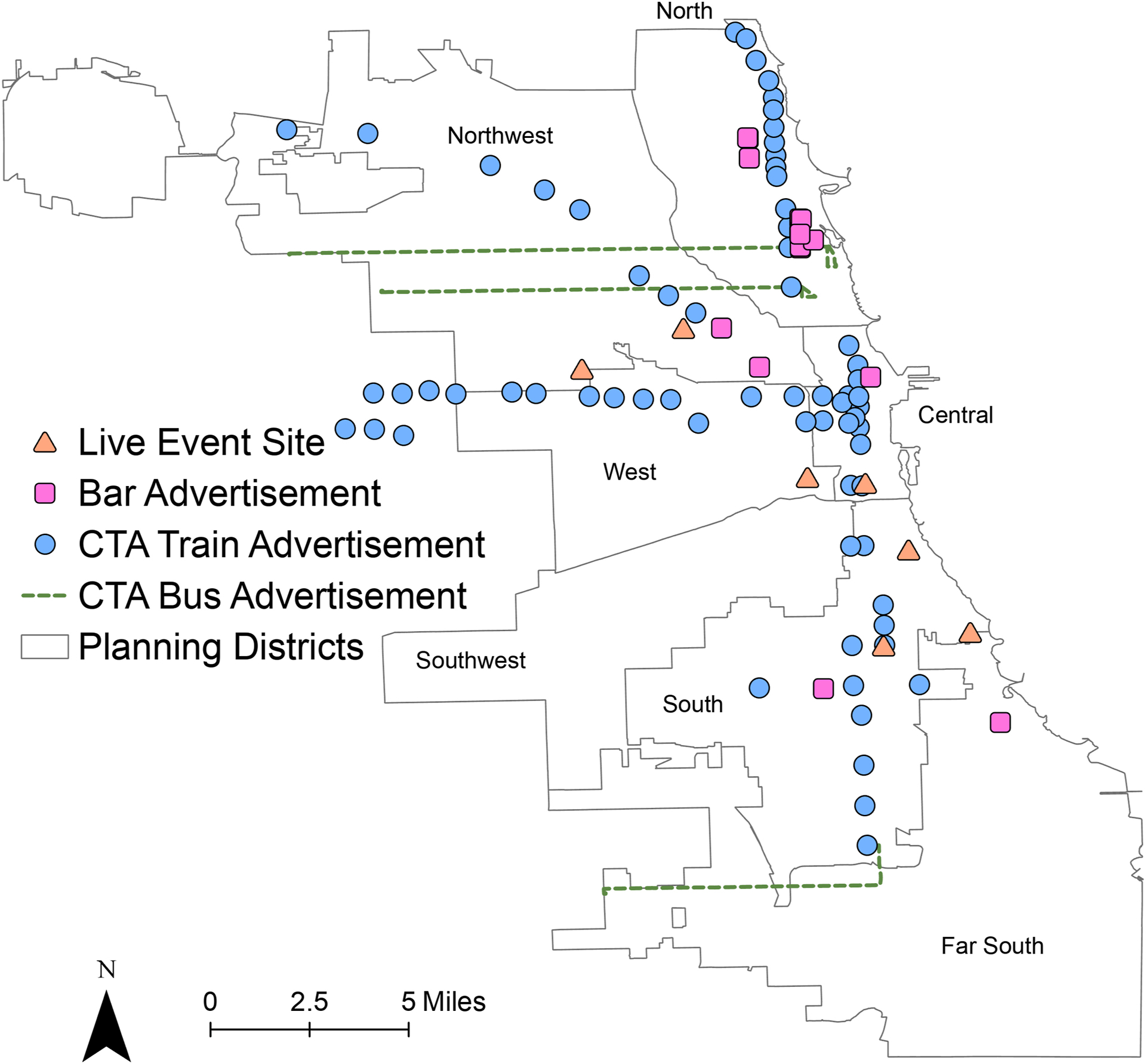

PrEP4Love was developed by AFC and IPWG in partnership with local advertising professionals, and with the input of priority population stakeholders including Black MSM and TW. A detailed description of the iterative development process is provided elsewhere.38 PrEP4Love materials were distributed citywide with a focus on city planning districts known to house MSM, as well as predominantly Black and Latinx residents (i.e., Chicago’s South and West Sides). Three separate advertisement deployments occurred in February 2016, September 2016, and February 2017 in a limited number of CTA Red, Blue, and Green Line train cars and at Red, Blue, and Green Line stations in Chicago (Figure 1). In addition, advertisements were deployed on three CTA bus lines. Advertisements in the form of drink coasters were also placed in gay bars located in city areas with elevated HIV prevalence. Black gay bars on Chicago’s South Side were an advertising priority; North Side gay bars were selected for advertisement if they reported racially diverse clientele, or hosted specific themed nights designed to appeal to Black MSM and/or TW. In addition to traditional marketing materials, there were seven live events held across Chicago to promote PrEP.

Fig. 1.

Locations of PrEP4Love Events and Advertisements by Chicago Planning District.

Participants

In order to be enrolled, participants had to meet the following criteria: between 16 and 29 years of age, assigned a male sex at birth, English-speaking, and reported a sexual encounter with a man in the previous year or identified as gay or bisexual.

Participants were recruited in three ways: 1) involvement in a cohort of YMSM and/or sexual and gender minority youth (Project Q2,39 Crew 450,40 and a new 2015 cohort) all of which enrolled individuals when they were between 16 and 20 years old; 2) through being a serious partner of an existing RADAR cohort member (i.e., being in a current serious relationship with a RADAR cohort member); or 3) through peer recruitment by an existing RADAR cohort member. Details about the previous cohorts can be found elsewhere,39,40 while the new 2015 cohort was recruited using venue-based, peer-referral, and online recruitment methods. Although all serious partners were eligible for a one-time visit, they were required to meet the above criteria for enrollment in the cohort. Similarly, peer recruits needed to meet the same criteria, plus they needed to be between 16 and 29 years of age. Age was restricted for peer recruits to match the recruitment design of the previous cohorts (i.e., Project Q2 and Crew 450), which at the time of the current study also had older participants (i.e., ages 20–29) and the overall RADAR sample needed to represent a full range of ages to achieve the multiple cohort, accelerated longitudinal design.41

Measures

Demographics.

At baseline, participants were asked to report their racial identity, and whether they identified as Hispanic or Latino. Following the 2007 United States Department of Education (USED) guidelines for combining ethnicity and race data, anyone who identified as Hispanic/Latino regardless of race was classified as Hispanic/Latino.42 All non-Hispanic/Latino individuals who identify as a single race were classified as that race; anyone who identified as two or more races were classified as multiracial. For sample size purposes, Asian, American Indian or Alaska Native, Multi-Racial, and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander individuals were recoded as “Other.” Other demographic information collected includes age, gender identity, educational attainment, and sexual orientation. The age variable was recoded based on quartiles: 16 to 20, 21 to 22, 23 to 24, and 25 to 31 years.

PrEP4Love awareness.

Awareness of the PrEP4Love campaign was assessed by the question “Have you seen or heard any advertisement(s) about PrEP (such as the PrEP4Love campaign) in Chicago?” All participants who responded “Yes” were asked the follow-up question “Where did you see or hear the PrEP4Love campaign?” Response options were presented as a “choose all that apply” list that included “Internet,” “At pride events,” “At local bars and clubs,” “From friends,” “From family,” “From healthcare provider,” and “Somewhere else.” All who selected “Somewhere else” were given the opportunity to provide an open ended response; due to a high frequency of reports of public transportation, a new category of “CTA (Chicago Transit Authority)” was added.

Provider Conversations and Healthcare.

All participants were asked “Has a medical provider, such as a doctor or nurse, ever talked to you about PrEP?” All participants who answered “Yes” were asked “Who initiated this conversation about PrEP?” and were given the options “I did” or “My medical provider did.”

A new analysis variable was developed to look at PrEP4Love’s influence on participants initiating conversations with their providers. This variable was derived from the questions “Have you seen or heard any advertisement(s) about PrEP (such as the PrEP4Love campaign) in Chicago?” and “Who initiated this conversation about PrEP?” The variable had four options for analysis:

Did see or hear a PrEP advertisement and initiated a conversation with their provider

Did see or hear a PrEP advertisement and did not initiate a conversation with their provider

Did not see or hear a PrEP advertisement and initiated a conversation with their provider

Did not see or hear a PrEP advertisement and did not initiate a conversation with their provider.

Statistical analysis

All data cleaning and statistical analyses were performed in R Version 3.5.1. Univariate statistics were used to describe the demographics of participants as well as proportions of individuals who had seen ads for PrEP4Love. With respect to PrEP4Love, three domains were of interest: awareness of the marketing campaign, perceptions of PrEP, and interactions with medical providers. Geographical information system (GIS) analyses were performed to explore spatial patterns of the PrEP4Love reach, and the three domains of interest. Participants reported their current residential address at each study visit, and the addresses at the visit corresponding to data for this report were geocoded using a local composite geocoder. Community area boundaries, planning districts, and CTA routes were plotted using shapefiles obtained from the City of Chicago and 2014–2015 HIV incidence data by community area were obtained from the Chicago Department of Public Health 2016 STI/HIV Surveillance Report.43,44 PrEP4Love ad placements and live event locations were obtained directly from AFC. To test the potential impact of time of survey administration (i.e., time between end of PrEP4Love campaign and completion of survey may have affected responses) on results, we examined two potential associations to verify whether survey date should be included as a covariate. There was no significant association between month of survey administration and awareness of the PrEP4Love campaign (χ2 = 11.40; df = 11; p = 0.41), indicating no evidence for time influence on awareness. Further, a Breslow-Day Test for Homogeneity was conducted to assess whether the association between awareness of PrEP4Love advertisements and speaking with a doctor about using PrEP differed over time, resulting in a non-significant association (χ2 = 16.34; df = 11; p = 0.13). Therefore, since results were not associated with time of survey completion, this variable was not included in any analyses.

GIS analyses were conducted using ArcGIS Pro 2.3.0. Only participants who were geocoded using the StreetAddress or AddressPoint locator and were within the city of Chicago’s geographical boundaries were included in geospatial analyses (n = 499). To allow for sufficient power in statistical analyses, Chicago planning districts were utilized to group participants into seven distinct areas of the city: North, Northwest, West, Southwest, Central, South, and Far South. These groupings effectively capture city areas which have demonstrated unique patterns of HIV risk per Chicago Department of Public Health surveillance.35,43,45

Results

Demographics and awareness

A complete demographic breakdown of participants is provided in Table 1. Approximately one-fifth of participants (18.9%) reported using PrEP in the last 6 months, and more than three-quarters of these participants (67.4%) were taking PrEP at the time of the interview. The majority of participants indicated that they had seen a PrEP4Love ad in Chicago (75.9%) (Table 1). The highest percentage indicated that they had seen ads on the internet (57.8%), followed by ads at pride events (50.7%). Fewer participants reported seeing or hearing about ads for PrEP from friends (35.0%), from healthcare providers (32.0%), at local bars or clubs (27.8%), or on Chicago public transportation (CTA; 25.6%).

Table 1.

Demographics and PrEP Characteristics of RADAR Participants (N = 700).

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 212 | 30.30 |

| Black or African American | 189 | 27.00 |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 222 | 31.70 |

| Other | 77 | 11.00 |

| Age, years | ||

| 16 to 20 | 217 | 31.00 |

| 21 to 22 | 218 | 31.10 |

| 23 to 24 | 101 | 14.40 |

| 25 to 31 | 164 | 23.40 |

| Sexual Identity | ||

| Gay | 487 | 69.60 |

| Bisexual | 124 | 17.70 |

| Queer | 49 | 7.00 |

| Straight/Heterosexual | 19 | 2.70 |

| Unsure/Questioning | 8 | 1.10 |

| Other | 13 | 1.90 |

| Gender Identity | ||

| Cisgender Male | 641 | 91.60 |

| Transgender Female | 30 | 4.30 |

| Other | 29 | 4.10 |

| Used PrEP, Last 6 Months | ||

| Yes | 132 | 18.90 |

| No | 567 | 81.10 |

| Heard/seen any ads about PrEP (PrEP4Love) in Chicago Location: | 531 | 75.90 |

| Internet | 307 | 57.80 |

| At pride events | 269 | 50.70 |

| At local bars/clubs | 148 | 27.80 |

| From friends | 186 | 35.00 |

| From family | 27 | 5.10 |

| From healthcare provider | 170 | 32.00 |

| CTA | 136 | 25.60 |

| Somewhere else | 39 | 7.30 |

Geospatial advertisement distribution and awareness

PrEP4Love ads were fairly widely distributed throughout the city of Chicago (Figure 1). Bars selected for PrEP4Love advertisements were primarily located on the North Side (75.0% in North and Northwest Districts), although it should be noted that advertisements were displayed in 100% of Black gay bars accepting paid advertising on the South Side (n = 2). Contrastingly, the majority of PrEP4Love live events occurred on the South Side (42.9% in South District).

PrEP4Love ads on CTA train lines and at CTA stations were located in all planning districts except Far South (which does not have CTA train access); train station ads were primarily located on the North Side (38.1% in North and Northwest Districts). Finally, as an attempt to ameliorate the structural barriers to advertisement placement in Chicago’s Far South, one of the three bus lines used for ads (103 – 103rd) was selected due to primarily serving locations in that planning area. The other two bus lines used for PrEP4Love ads run from the North to the West (77 – Belmont and 74 – Fullerton).

The percentage of individuals who saw PrEP4love advertisements varied considerably by community area. Surprisingly, West Chicago saw the highest percentage of individuals who had seen advertisements (87%), followed by North (84%), Far South (81.3%), and South (80.68%). The lowest 3 areas were Northwest (69%), Central (67%), and Southwest (62%).

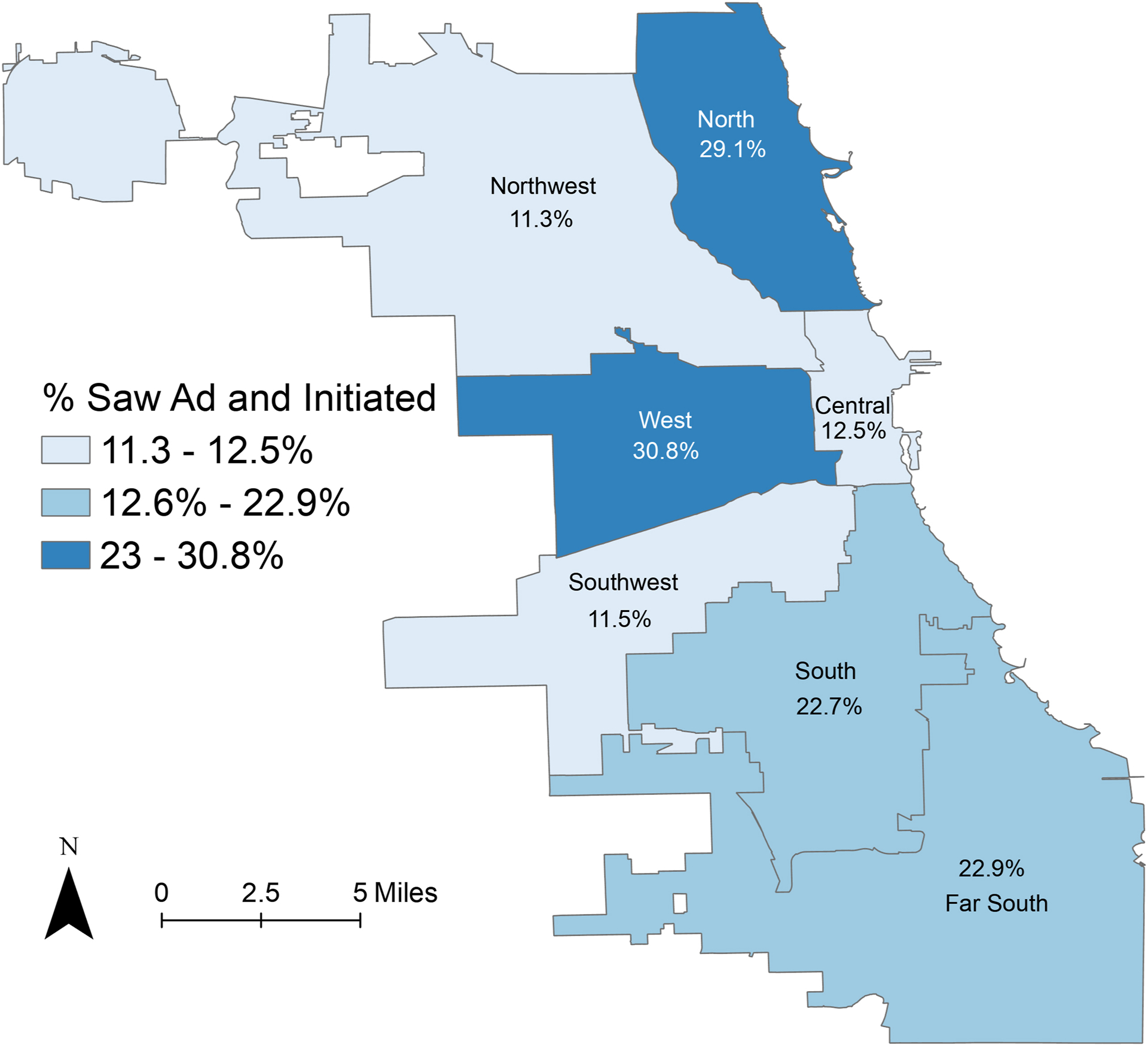

Geospatial patterns with PrEP4Love and participant behaviors

To explore potential geospatial patterns, participants’ PrEP4Love engagement and health behaviors were analyzed by participant planning district of residence in Chicago (Table 2; Figure 2). Across districts, the percentage of individuals who saw ads for PrEP but did not initiate use remained relatively constant between 50% and 60% and consistently comprised the majority of observations (ranging from 58.6% in Far South Chicago to 50% in Southwest Chicago; Table 2). Similarly, one outcome consistent across geographic planning districts was that a very small number of individuals did not see ads for PrEP but initiated use anyway. Across districts, the percentage of observations for which this is true never exceeds 5%.

Table 2.

PrEP4Love Ad Exposure and PrEP Initiation by Chicago Planning District (N = 499).

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Central Chicago | ||

| Saw ad and initiated | 3 | 12.50 |

| Saw ad and did not initiate | 13 | 54.17 |

| Did not see ad and initiated | 1 | 4.17 |

| Did not see ad and did not initiate | 7 | 29.17 |

| Far South Chicago | ||

| Saw ad and initiated | 16 | 22.86 |

| Saw ad and did not initiate | 41 | 58.57 |

| Did not see ad and initiated | 0 | 0.00 |

| Did not see ad and did not initiate | 13 | 18.57 |

| North Chicago | ||

| Saw ad and initiated | 45 | 29.03 |

| Saw ad and did not initiate | 85 | 54.84 |

| Did not see ad and initiated | 2 | 1.29 |

| Did not see ad and did not initiate | 23 | 14.84 |

| Northwest Chicago | ||

| Saw ad and initiated | 11 | 11.34 |

| Saw ad and did not initiate | 56 | 57.73 |

| Did not see ad and initiated | 4 | 4.12 |

| Did not see ad and did not initiate | 26 | 26.80 |

| South Chicago | ||

| Saw ad and initiated | 20 | 22.73 |

| Saw ad and did not initiate | 51 | 57.95 |

| Did not see ad and initiated | 3 | 3.41 |

| Did not see ad and did not initiate | 14 | 15.91 |

| Southwest Chicago | ||

| Saw ad and initiated | 3 | 11.54 |

| Saw ad and did not initiate | 13 | 50.00 |

| Did not see ad and initiated | 1 | 3.85 |

| Did not see ad and did not initiate | 9 | 34.62 |

| West Chicago | ||

| Saw ad and initiated | 12 | 30.77 |

| Saw ad and did not initiate | 22 | 56.41 |

| Did not see ad and initiated | 0 | 0.00 |

| Did not see ad and did not initiate | 5 | 12.82 |

Fig. 2.

RADAR Participants’ Awareness of PrEP4Love Ads and Participant Initiation of PrEP Conversation with Provider by Chicago Planning District.

In contrast, the percentage of individuals who saw ads for PrEP and initiated use varied considerably by planning area. In West Chicago, 30.8% of surveyed individuals saw ads and initiated use (the highest across districts), followed by North Chicago (29.1%), Far South Chicago (22.9%), South Chicago (22.7%), and Central Chicago (12.5%). Southwest Chicago and Northwest Chicago show the lowest potential conversion rates, with a respective 11.5% and 11.3% of participants who had seen ads initiating PrEP use.

The proportions of individuals who did not see an ad and did not initiate PrEP use varied geographically as well. In Southwest Chicago, almost 35% of individuals reported not seeing an ad and not initiating use. Only about 13% of individuals reported this outcome in West Chicago. Both Central and Northwest Chicago had similar proportions of individuals who had neither seen ads nor initiated PrEP use (29.2% and 26.8%, respectively). The remaining districts reported between 14% and 18% of individuals neither seeing ads nor initiating use.

Discussion

The PrEP4Love campaign and its effect on PrEP uptake can be examined on multiple levels of the socio-ecological framework,46 from individual self-efficacy to how health system interaction is a function of structural context. Prior work has assessed the successes of the campaign at the individual and network level, noting promising associations between seeing ads and outness to providers, patient-initiated PrEP discussions, perceived stigma, and PrEP use.38 These new results provide evidence that PrEP4Love’s efficacy is potentially mediated by the structural and neighborhood context of Chicago. When analyzed by planning area, key geographical differences emerged which may have limited the campaign’s ability to reach and connect Black and Latinx MSM and TW with PrEP services. If, as the data suggest, PrEP publicity campaigns play a role in patient empowerment and facilitating patient-provider interactions that lead to PrEP prescription, this is a critical consideration.

While the low and unequal sample size in each of the planning districts prevents more rigorous geospatial comparisons, basic frequencies highlight trends suggesting future research. In particular, there are two areas that suggest the enduring effects of redlining and disproportionate community investment on the amount of available infrastructure for sustained campaign programming. The first is the availability of infrastructure for social marketing opportunities (e.g., gay bars, clinics, and public transit) and the potential reach of the campaign (the percent of participants who saw advertisements). The second is a potential relationship between access to PrEP services, proximity to PrEP clinics, and actionability of PrEP4Love advertisements (the percent of participants who saw ads and initiated a discussion with their provider about PrEP).

For example, the percentage of participants who had seen PrEP4Love ads and the rate at which participants initiated conversations with their providers after seeing an ad varied similarly by planning district. The West and North districts noted the highest rates of participants who had seen advertisements (87% and 84%, respectively), a potential result of increased infrastructure to support advertisement distribution due to greater availability of public transit in both areas and more gay bars, clinics, and other infrastructure for unpaid advertisements in the North (Figure 1). Unfortunately, no data were collected regarding unpaid advertisements, thus we are unable to test this possibility.

In addition, over one-third of individuals who saw ads and who lived in the North and West districts initiated conversations with their doctor about PrEP - approximately double the rate of individuals living in the Central, Northwest, and Southwest districts. It is important to consider how factors such as transportation or the availability of LGBT-affirming care in a given community area may impact the success of campaigns. The largest concentrations of PrEP providers are in the North and Central districts of Chicago;47 not only does this provide more opportunities for advertisement engagement, but upon seeing the ad, individuals could make an appointment to talk to a provider about initiating PrEP more easily than individuals in the Southwest or Northwest, which are known to be underserved by both public transit and health services.46,48 Higher initiation rates in the West could thus be explained by increased access to public transit in that area, despite similarly low density of PrEP care providers.46 Recent literature on “PrEP deserts,” or areas in which no PrEP clinics are available, supports this interpretation. Research has demonstrated that a lack of PrEP clinics can exacerbate HIV disparities through limiting access to medication.49 While most research into PrEP deserts has taken place in rural communities, distance to clinic has been shown in the local Chicago context to be a barrier to PrEP - the location of providers, in separate analyses of the same cohort, has been shown to impact the awareness and motivations of MSM and TW in seeking sexual health services.37 Taken together, such evidence indicates that the success of PrEP promotional campaigns is contingent on investment in making PrEP providers more accessible through training local providers, improving dispersion of health services throughout the city, and increasing public transit access.

Central to any discussion of these findings is the history of racist and segregationist city planning in Chicago, which produces stark differences in racial makeup by community area.50–52 Chicago’s residential segregation has stark impacts on both health care access and health outcomes, making it a vital consideration for any geospatial analysis of the city.53–56 An example of such in our data is the case of public transit. Prior evaluation of PrEP4Love has established that Black and Latinx individuals were less likely to report seeing the campaign on Chicago public transportation;38 research has previously noted that the racial and socioeconomic fragmentation of Chicago neighborhoods severely impacts public transit for racial/ethnic minority residents.51,52 Thus, it is unsurprising that PrEP4Love advertisements on CTA, as well as the percentage of those who saw advertisements, were more concentrated on the Northeast Side of Chicago - comprised of predominantly White, affluent neighborhoods. While some Northeast Chicago neighborhoods are heavily impacted by HIV,57 there is also a higher availability of CTA transit stations and HIV service providers there than in other areas of the city due to Chicago’s city planning history, which de-prioritized predominantly Black, low-income neighborhoods.

Taken together, our findings point to the enduring legacy of structural racism in creating barriers to ending the HIV epidemic today. Results suggest that future PrEP campaigns must intentionally tailor the distribution of advertisements to structural/community context to ensure exposure in underserved populations that may benefit the most from PrEP. Some limitations in campaign reach may be reduced with increased marketing via alternative avenues such as the internet or pride events, or through supplemental intervention components including increased linkage to care services for individuals engaged by advertising. While prevention campaigns alone cannot be expected to solve the legacies of discrimination, they can work to contextualize approaches within localized social and geographic contexts. Failure to do so may perpetuate ongoing health inequities in contexts including but not limited to HIV prevention and care.

Even in the context of the most impactful health messaging campaign imaginable, structural approaches to supporting service connectivity and adherence are required to further alleviate disparities in HIV outcomes. Campaign funders, developers, and evaluators should thus intentionally seek opportunities to advocate for the removal of structural barriers to care in service of health equity. Therefore, as health equity researchers and evaluators ourselves, we call on the City of Chicago and on Chicago-based care providers and health centers to prioritize expanding transit and healthcare infrastructure in underserved areas of the city to allow for improved penetration of healthcare education and resources for marginalized communities. The time is long overdue to meaningfully reckon with historical and contemporary structural harms; doing so is vital to ensure a healthy, just, and equitable Chicago for all.

Finally, our findings demonstrate a valuable role for geospatial analysis in evaluating prevention messaging campaigns. Integration of geospatial analysis within historical context has the potential to illuminate evidence of structural discrimination, and point to potential responses for stakeholders in addressing such. In the future, geospatial analysis could be applied to nearly any program that exists across a large enough geographic range wherein neighborhood and spatial effects should be considered. This could be effectively applied at the intra-community, city-wide, or regional levels. Both the successes and limitations of the current study can serve as a framework for the incorporation of such analyses into future campaigns.

Limitations

The primary limitation to our study is that we are unable to fully measure the impact of PrEP4Love because the survey was cross-sectional and data were limited. The non-longitudinal nature of the available data limits causal inferences, although the gap in time between the conclusion of the active PrEP4Love campaign and this assessment (the campaign’s paid CTA advertising phase ended more than 6 months before the survey, which asked about PrEP use in the prior 6 months) lends some credence to the interpretation that PrEP4Love helped facilitate service connectivity. To gain a better view of PrEP marketing, future research should evaluate impacts at multiple time points. There is additional evidence in favor of a temporal relationship between seeing PrEP4Love materials and uptake, as those who had seen ads for PrEP were more likely to have taken PrEP in the last six months.38 However, it is also possible that those already on PrEP were more likely to notice ads due to self-relevance, therefore, directionality cannot be confirmed. Moreover, as our limited data prevented more rigorous geospatial analysis, future evaluations of campaigns such as PrEP4Love should plan for geospatial analyses in advance and cultivate a sample size and data pool which are sufficient to perform more in-depth statistical tests, as our results have demonstrated that this is an important and potentially fruitful area of investigation. Secondly, the network sampling approach was limited in that only existing RADAR cohort members were eligible to recruit peers into their study, so true snowball sampling was not reflected in that recruitment chains did not drive the sample. However, it is possible that people with larger networks recruited more people into the study, and this may have biased the sample. In addition, we were unable to assess potential confounding factors, such as the ability to afford PrEP, which limits the inferences we can confidently make regarding our results. Finally, there remain important neighborhood factors known to elevate risk and resource connectivity which we were unable to directly assess within the study.58–61 More rigorous geospatial analyses incorporating study of similar factors should be considered for future PrEP campaign evaluation.

Conclusions

This study presents novel geospatial data in the city of Chicago, noting the PrEP4Love campaign’s associations with empowered HIV prevention behaviors and their variance by geographic region of the city. Our data suggest that, given the city’s current health and transportation infrastructure, PrEP promotional campaigns and their effectiveness are potentially mediated by the accessibility of PrEP-related services in the area, transportation infrastructure, and structural racism and segregation. Such interventions must take into account the community context and resource availability of neighborhoods, as the act of promoting awareness and removing stigma must coincide with other structural approaches that ensure the next action steps for an individual along the PrEP continuum can be taken. As such, this study shows the viability for an ecologically informed approach to evaluating health campaigns with the use of geospatial data. Recognizing historical, structural impacts on the viability of campaigns, geospatial analysis provides the opportunity to more accurately and contextually assess the reach to underrepresented groups, better serving the population as a whole.

Highlights:

Health messaging campaigns should consider geospatial contexts.

City infrastructure and services may influence the distribution of advertisements.

Historical, structural discrimination results in inequitable message diffusion.

It is vital to consider how these structures will impact campaign efficacy.

Service and transportation access are key components in PrEP messaging strategies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnoses of HIV Infection in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2017. In: Services DoHaH, ed. Vol 29 Atlanta, GA: Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Fact Sheet: HIV among Gay and Bisexual Men. In: Services DoHaH, ed. Atlanta, Georgia: Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becasen JS, Denard CL, Mullins MM, Higa DH, Sipe TA. Estimating the Prevalence of HIV and Sexual Behaviors Among the US Transgender Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, 2006–2017. American Journal of Public Health. 2019;109(1):E1–E8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Among African Americans. CDC Fact Sheet. 2015:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Among African American Gay and Bisexual Men. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/msm/bmsm.html. Published 2018. Accessed 02/15/2018.

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Among Latinos. In: Services DoHaH, ed. Atlanta, Georgia: Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV and Transgender People. 2019.

- 8.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Antiretroviral Prophylaxis for HIV Prevention in Heterosexual Men and Women. New Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):399–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Philbin MM, Parker CM, Parker RG, Wilson PA, Garcia J, Hirsch JS. The Promise of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis for Black Men Who Have Sex with Men: An Ecological Approach to Attitudes, Beliefs, and Barriers. AIDS Patient Care St. 2016;30(6):282–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Volk JE, Marcus JL, Phengrasamy T, et al. No New HIV Infections With Increasing Use of HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis in a Clinical Practice Setting. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2015;61(10):1601–1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoots BE, Finlayson T, Nerlander L, Paz-Bailey G, National HIVBSSG. Willingness to Take, Use of, and Indications for Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Among Men Who Have Sex With Men-20 US Cities, 2014. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(5):672–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eaton LA, Driffin DD, Bauermeister J, Smith H, Conway-Washington C. Minimal Awareness and Stalled Uptake of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Among at Risk, HIV-Negative, Black Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2015;29(8):423–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Airhihenbuwa CO, Ford CL, Iwelunmor JI. Why culture matters in health interventions: lessons from HIV/AIDS stigma and NCDs. Health Educ Behav. 2014;41(1):78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Airhihenbuwa CO. Health promotion and the discourse on culture: implications for empowerment. Health Educ Q. 1994;21(3):345–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petroll AE, Walsh JL, Owczarzak JL, McAuliffe TL, Bogart LM, Kelly JA. PrEP Awareness, Familiarity, Comfort, and Prescribing Experience among US Primary Care Providers and HIV Specialists. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(5):1256–1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skolnik AA, Bokhour BG, Gifford AL, Wilson BM, Van Epps P. Roadblocks to PrEP: What Medical Records Reveal About Access to HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(3):832–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agenor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Racism and Health I: Pathways and Scientific Evidence. Am Behav Sci. 2013;57(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, Link BG. Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):813–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poteat T, German D, Kerrigan D. Managing uncertainty: a grounded theory of stigma in transgender health care encounters. Soc Sci Med. 2013;84:22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denson DJ, Padgett PM, Pitts N, et al. Health Care Use and HIV-Related Behaviors of Black and Latina Transgender Women in 3 US Metropolitan Areas: Results From the Transgender HIV Behavioral Survey. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;75 Suppl 3:S268–S275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palazzolo SL, Yamanis TJ, De Jesus M, Maguire-Marshall M, Barker SL. Documentation Status as a Contextual Determinant of HIV Risk Among Young Transgender Latinas. LGBT Health. 2016;3(2):132–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leviton LC, Snell E, McGinnis M. Urban issues in health promotion strategies. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(6):863–866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ko JE, Jang Y, Park NS, Rhew SH, Chiriboga DA. Neighborhood effects on the self-rated health of older adults from four racial/ethnic groups. Soc Work Public Health. 2014;29(2):89–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ellen IG, Mijanovich T, Dillman KN. Neighborhood effects on health: Exploring the links and assessing the evidence. J Urban Aff. 2001;23(3–4):391–408. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roux AVD. Investigating neighborhood and area effects on health. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(11):1783–1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Latkin CA, German D, Vlahov D, Galea S. Neighborhoods and HIV: a social ecological approach to prevention and care. Am Psychol. 2013;68(4):210–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eberhart MG, Yehia BR, Hillier A, et al. Behind the Cascade: Analyzing Spatial Patterns Along the HIV Care Continuum. JAIDS-J Acq Imm Def. 2013;64:S42–S51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dasgupta SKM, Rosenberg ES, Sanchez TH, Reed L, Sullivan PS. The Effect of Commuting Patterns on HIV Care Attendance Among Men Who Have Sex With Men (MSM) in Atlanta, Georgia. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2015;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krieger N Methods for the scientific study of discrimination and health: an ecosocial approach. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):936–944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ransome Y, Kawachi I, Braunstein S, Nash D. Structural inequalities drive late HIV diagnosis: The role of black racial concentration, income inequality, socioeconomic deprivation, and HIV testing. Health & Place. 2016;42:148–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eberhart MG, Yehia BR, Hillier A, et al. Individual and community factors associated with geographic clusters of poor HIV care retention and poor viral suppression. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69 Suppl 1:S37–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beach LB, Greene GJ, Lindeman P, et al. Barriers and Facilitators to Seeking HIV Services in Chicago Among Young Men Who Have Sex with Men: Perspectives of HIV Service Providers. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2018;32(11):468–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chicago Department of Public Health. HIV/STI Surveillance Report. In: Health CDoP, ed. Chicago, IL2018. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Phillips G 2nd, Birkett M, Kuhns L, Hatchel T, Garofalo R, Mustanski B. Neighborhood-level associations with HIV infection among young men who have sex with men in Chicago. Arch Sex Behav. 2015;44(7):1773–1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Phillips G, Neray B, Janulis P, Felt D, Mustanski B, Birkett M. Utilization and avoidance of sexual health services and providers by YMSM and transgender youth assigned male at birth in Chicago. AIDS Care. 2019:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Phillips G 2nd, Raman AB, Felt D, et al. PrEP4Love: The Role of Messaging and Prevention Advocacy in PrEP Attitudes, Perceptions, and Uptake Among YMSM and Transgender Women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mustanski B, Garofalo R, Emerson EM. Mental health disorders, psychological distress, and suicidality in a diverse sample of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youths. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(12):2426–2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mustanski B, Johnson AK, Garofalo R, Ryan D, Birkett M. Perceived likelihood of using HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis medications among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(6):2173–2179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miyazaki Y, Raudenbush SW. Tests for linkage of multiple cohorts in an accelerated longitudinal design. Psychological Methods. 2000;5(1):44–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.U.S. Department of Education. Final Guidance on Maintaining, Collecting, and Reporting Racial and Ethnic Data to the U.S. Department of Education. In: Education USDo, ed. Vol 72 FR 59266 Federal Register: U.S. Department of Education; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chicago Department of Public Health. HIV/STI Surveillance Report. In: Health CDoP, ed. Chicago, IL2016. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chicago Department of Public Health. Chicago Data Portal. In:2017.

- 45.Chicago Department of Public Health. HIV/STI Surveillance Report. In: Health CDoP, ed. Chicago, IL2017. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bronfenbrenner U The ecology of human development : experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pierce SJ, Miller RL, Morales MM, Forney J. Identifying HIV prevention service needs of African American men who have sex with men: An application of spatial analysis techniques to service planning. J Public Health Man. 2007:S72–S79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Farmer S Uneven public transportation development in neoliberalizing Chicago, USA. Environ Plann A. 2011;43(5):1154–1172. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Siegler AJ, Bratcher A, Weiss KM, Mouhanna F, Ahlschlager L, Sullivan PS. Location location location: an exploration of disparities in access to publicly listed pre-exposure prophylaxis clinics in the United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2018;28(12):858–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Novara M, Khare A. Two Extremes of Residential Segregation: Chicago’s Separate Worlds & Policy Strategies for Integration. President and Fellows of Harvard College. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Farmer S Uneven Public Transportation Development in Neoliberalizing Chicago, USA. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space. 2011;43(5):1154–1172. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Delmelle EC. The Increasing Sociospatial Fragmentation of Urban America. Urban Science. 2019;3(1):9. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tung EL, Boyd K, Lindau ST, Peek ME. Neighborhood crime and access to health-enabling resources in Chicago. Prev Med Rep. 2018;9:153–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krieger N Embodying inequality: A review of concepts, measures, and methods for studying health consequences of discrimination. Int J Health Serv. 1999;29(2):295–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Park YM, Kwan M-P. Multi-Contextual Segregation and Environmental Justice Research: Toward Fine-Scale Spatiotemporal Approaches. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2017;14(10):1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Duncan DT, Hickson DA, Goedel WC, et al. The Social Context of HIV Prevention and Care among Black Men Who Have Sex with Men in Three U.S. Cities: The Neighborhoods and Networks (N2) Cohort Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019;16(11):1922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Health CDoP. HIV/STI Surveillance Report 2019. 2019.

- 58.Johns MM, Bauermeister JA, Zimmerman MA. Individual and Neighborhood Correlates of Hiv Testing among African American Youth Transitioning from Adolescence into Young Adulthood. AIDS Educ Prev. 2010;22(6):509–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kerrigan D, Witt S, Glass B, Chung SE, Ellen J. Perceived neighborhood social cohesion and condom use among adolescents vulnerable to HIV/STI. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;10(6):723–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Surratt HL, Kurtz SP, Levi-Minzi MA, Chen MX. Environmental Influences on HIV Medication Adherence: The Role of Neighborhood Disorder. American Journal of Public Health. 2015;105(8):1660–1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Joy R, Druyts EF, Brandson EK. Impact of Neighborhood-Level Socioeconomic Status on HIV Disease Progression in a Universal Health Care Setting (vol 47, pg 500, 2008). JAIDS-J Acq Imm Def. 2010;53(3):424–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]