This survey study presents nationally representative estimates of recent trends in adolescent nicotine vaping, perceived risk of harm from vaping, accessibility of vaping materials, as well as trends in use of specific vaping brands and flavors.

Key Points

Question

How has nicotine vaping prevalence trended among US adolescents from 2017 to 2020?

Findings

In this survey study of 8660 10th- and 12th-grade students, increases in teenage vaping from 2017 to 2019 halted in 2020. Significant declines in use of the JUUL brand were countered by significant increases in use of other vaping brands.

Meaning

Adolescent nicotine vaping remains highly prevalent, and this study found that 22% of teenagers vaped nicotine in the past 30 days in 2020.

Abstract

Importance

US adolescent nicotine vaping increased at a record pace from 2017 to 2019, prompting new national policies to reduce access to flavors of vaping products preferred by youth.

Objective

To estimate prevalence, perceived harm, and accessibility of nicotine vaping products among US adolescents from 2017 to 2020.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This survey study includes data from Monitoring the Future, which conducted annual, cross-sectional, school-based, nationally representative surveys from 2017 to 2020 of 10th- and 12th-grade students (results pooled grades, n = 94 320) about vaping and other topics.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Prevalence of self-reported nicotine vaping; vaping brand and flavor used most often; perceived risk of nicotine vaping; and perceived ease of getting vaping devices, nicotine solutions for vaping, and flavored solutions.

Results

In 2020, Monitoring the Future surveyed 8660 students in 10th and 12th grade, of whom 50.6% (95% CI, 47%-54%) were female, 13% (95% CI, 8%-21%) were non-Hispanic Black, 29% (95% CI, 21%-40%) were Hispanic, and 53% (95% CI, 42%-63%) were non-Hispanic White. Nicotine vaping prevalence in 2020 was 22% (95% CI, 19%-25%) for past 30-day use, 32% (95% CI, 28%-37%) for past 12-month use, and 41% (95% CI, 37%-46%) for lifetime use; these levels did not significantly change from 2019. Daily nicotine vaping (use on ≥20 days of the last 30 days) significantly declined from 9% (95% CI, 8%-10%) to 7% (95% CI, 6%-9%) over 2019 to 2020. JUUL brand prevalence in the past 30 days decreased from 20% (95% CI, 18%-22%) in 2019 to 13% (95% CI, 11%-15%) in 2020, while use of other brands increased. Among youth who vaped in the past 30 days in 2020, the most often used flavor was fruit at 59% (95% CI, 55%-63%), followed by mint at 27% (95% CI, 24%-30%) and menthol at 7% (95% CI, 5%-9%); significantly fewer reported easy access to vaping devices and nicotine solutions compared with 2019; and 80% (95% CI, 75%-84%) reported they could easily get a vaping flavor other than tobacco or menthol. Among all youth, perceived risk of both occasional and regular nicotine vaping increased from 2019 to 2020.

Conclusions and Relevance

Increasing US adolescent nicotine vaping trends from 2017 to 2019 halted in 2020, including a decline in daily vaping. Decreases in perceived accessibility of some vaping products, as well as increases in perceived risk of nicotine vaping, occurred from 2019 to 2020. Yet, adolescent nicotine vaping remains highly prevalent, flavors remain highly accessible, and declines in JUUL use were countered by increased use of other brands.

Introduction

Nicotine vaping among youth has increased at a rapid pace in recent years,1 a trend that has raised concerns because of the various adverse health effects associated with adolescent vaping.2,3 In 2019, past 30-day youth nicotine vaping was reported by 25% of US 12th graders and 20% of 10th graders.1

The rapid rise of youth vaping may have recently slowed or even reversed as a result of noteworthy events during late 2019 and early 2020. The e-cigarette and vaping–associated lung injury (EVALI) epidemic that received considerable media attention in the second half of 20194 may have deterred use by increasing adolescent perceptions of harm from vaping. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) began enforcement on February 7, 2020, against the sale of e-cigarette cartridges with flavors other than tobacco or menthol, an enforcement aimed at reducing adolescent nicotine vaping by restricting supply.5 This FDA action came after the decision by JUUL Labs, which marketed the most widely used e-cigarette product youth vaped in 2019,6 to voluntarily stop selling most of their flavored cartridges preferred by youth.7 In addition, the federal minimum age for legal e-cigarette purchase changed from 18 to 21 years on December 20, 2019, thereby potentially reducing youth access to vaping products.8

The sum influence of these events on prevalence of US adolescent vaping from 2019 to 2020 is currently unknown and important to document to aid ongoing policy and intervention efforts to counteract the youth nicotine vaping epidemic. To address this gap, this report presents nationally representative estimates of recent trends in adolescent nicotine vaping, perceived risk of harm from vaping, accessibility of vaping materials, as well as trends in use of specific vaping brands and flavors.

Methods

Data for this study come from Monitoring the Future’s (MTF) annual nationally representative, cross-sectional samples of US 10th and 12th graders surveyed between February and June from 2017 to 2020. For a detailed description of MTF, including the complex multistage sampling design, see Bachman et al.9 Personnel from the University of Michigan administered MTF surveys in classrooms, and students self-completed questionnaires during a normal class period. The University of Michigan institutional review board approved the study. Informed consent (either passive consent or active [ie, written] consent, per school policy) was obtained from parents for students younger than 18 years and from students 18 years or older.

eTable 1 in the Supplement details the question wording, response categories, and sample size for the study. The number of responses can vary across questions in the same year because some MTF questions appear on only a randomly selected subsample of questionnaires. This procedure increases the number of questions that the survey can include and therefore the scope of the issues covered. The questions that appear on a subsample of surveys are nationally representative because a random sample of a random sample is still representative of the target population. However, the smaller number of responses for the subsample questions results in larger standard errors of estimates and consequently less statistical power to detect statistically significant differences across time.

All statistical analyses pooled the 10th- and 12th-grade samples and used Stata MP version 15.1 software (StataCorp) with the svy: suite of commands to take into account the complex multistage sample design, including clustering of respondents in primary sampling units. All estimates were weighted so that they are nationally representative. The analyses used Wald χ2 analyses to test if prevalence levels significantly differed across years at the P < .05 level for a 2- tailed test. Prevalence estimates presented in all tables are not adjusted for covariates or missing data, which allows direct comparison with estimates from the past 4 decades of the project that are reported in the same manner.10 In addition, trend analyses using logistic regression modeled outcomes as a function of both year and also year2, with a statistically significant year2 term indicating a nonlinear time trend.

The analyses include 2 sensitivity analyses. The first considers the influence of curtailed data collection in 2020 by replicating analyses for all Tables and Figures after restricting data from all years to surveys collected on or before March 14, 2020, when 2020 data collection halted. The second considers the relative influence of the 12th- and 10th-grade samples on the results by testing multiplicative interaction terms of grade and year for each of the study’s 17 main outcomes.

Results

Descriptive Analyses of Sample

In 2020, MTF collected 8660 surveys from 10th- and 12th-grade students in 74 schools before MTF stopped data collection prematurely on March 14, 2020, due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) concerns. This was 30% the size of a typical annual MTF data collection, which averaged 28 649 students and 246 schools from 2017 to 2019.11 At the time of the 2020 halt, MTF had collected data from a wide geographic range and had surveyed schools in each of the 9 US Census geographic divisions (with weighting each division has influence on the analysis per its size nationally). The 2020 response rates within schools were 81% for 12th-grade students (3770 of 4627) and 84% for 10th-grade students (4890 of 5829).

Descriptive analyses indicate that the results of the curtailed MTF 2020 data collection did not differ from the nationally representative results from previous years in terms of sociodemographics and selected measures of drug use. In 2020, 51% of participants were female (range, 51%-51% in 2017-2019), 53% were non-Hispanic White (range, 51%-53% in 2017-2019), 29% were Hispanic (range, 26%-29% in 2017-2019), and 49% had a mother with a college degree (range, 46%-47% in 2017-2019). Levels of substance use in 2020 also matched closely for drugs with highly consistent prevalence levels from 2017 to 2019; these include 38% for lifetime marijuana use (range, 37%-38% in 2017-2019), 6% for lifetime hallucinogen use (range, 5%-6% in 2017-2019), 53% for lifetime alcohol use (range, 50%-51% in 2017-2019), and 32% for ever got drunk (range, 29%-30% in 2017-2019). The eFigure and eTables 2 and 3 in the Supplement present detailed estimates and 95% CIs for these demographic and substance use prevalence levels.

Primary Results

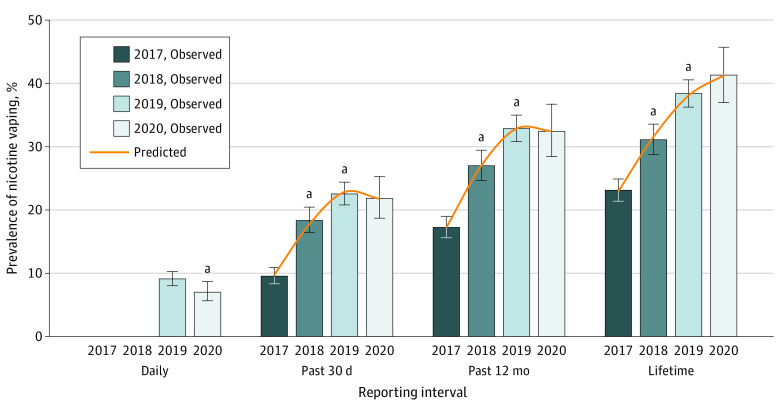

Figure 1 presents trends in adolescent nicotine vaping from 2017 to 2020, and eTable 4 in the Supplement presents the detailed estimates. Lifetime, past 12-month, and past 30-day nicotine vaping levels in 2020 did not significantly differ from 2019 levels. Daily vaping, defined as vaping on 20 or more days in the past 30 days, significantly declined from 9% in 2019 to 7% in 2020. All these outcomes showed nonlinear time trends in which the pace of increase decelerated from 2017 to 2020.

Figure 1. Prevalence of Nicotine Vaping Among US 10th- and 12th-Grade Students, by Year and Reporting Interval.

Error bars indicate 95% CIs. Daily use defined as nicotine vaping on 20 or more days in the last 30 days and was not measured before 2019. Exact observed and predicted estimates are in eTable 4 in the Supplement.

aThese years’ prevalence level significantly differs from previous year at P < .05 level for a 2-tailed test.

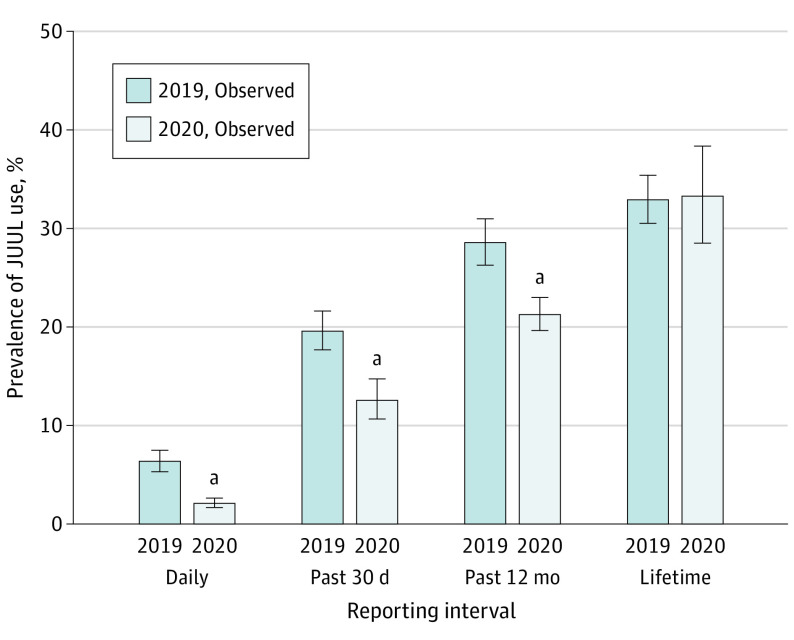

Figure 2 presents trends in adolescent use of the JUUL brand for nicotine vaping from 2019 to 2020, and eTable 5 in the Supplement presents the detailed estimates. Daily JUUL use, defined as use on 20 or more days in the last 30 days, dropped 3-fold from 6% in 2019 to 2% in 2020. Past 30-day use dropped from 20% in 2019 to 13% in 2020. Use in the past 12 months dropped from 29% in 2019 to 21% in 2020. Lifetime JUUL use held steady at 33% in both years.

Figure 2. Prevalence of JUUL Use Among US 10th- and 12th-Grade Students, by Year and Reporting Interval.

Error bars indicate 95% CIs. Daily use defined as JUUL use on 20 or more days in the last 30 days. Exact estimates are in eTable 5 in the Supplement.

aThese years’ prevalence level significantly differs from previous year at P < .05 level for a 2-tailed test.

Table 1 presents trends in the vaping brands adolescents report using most often, among those who have vaped nicotine in the last 30 days. The largest change was a decrease in use of the brand JUUL, which fell by an absolute 18 percentage points from 59% in 2019 to 41% in 2020 for a relative decrease of 43%. This change was offset by an increase of an absolute 17 percentage points in students who used a brand other than those listed in the response categories, a response that increased from 11% in 2019 to 28% in 2020. SMOK brand prevalence declined from 21% in 2019 to 13% in 2020, and Vuse brand prevalence increased from 1% to 7% over this time.

Table 1. Prevalence of Vaping Brands Reported Most Often Used Among 10th- and 12th-Grade Students Who Vaped Nicotine in the Past 30 Days, by Year.

| Variable | Prevalence, % (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JUUL | Othera | SMOK | Suorin | Vuse | Stig | |

| 2019 | 58.7 (53.3 to 63.8) | 11.3 (9.3 to 13.7) | 20.5 (16.6 to 25.1) | 8.3 (5.9 to 11.6) | 1.2 (0.7 to 2.1) | NA |

| 2020 | 41.1 (35.7 to 46.7) | 27.8 (23.1 to 33.0) | 13.1 (9.2 to 18.4) | 7.2 (4.4 to 11.7) | 7.3 (4.8 to 11.1) | 3.4 (1.9 to 6.1) |

| Absolute change in observed values from 2019-2020 | −17.6 (−24.9 to −10.3)b | 16.5 (11.0 to 21.9)b | −7.4 (−13.6 to −1.2)b | −1.0 (−5.3 to 3.2) | 6.1 (3.0 to 9.3)b | NA |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

In 2020, 30% of respondents in this category wrote in Puff Bar or a spelling variant thereof, which makes this brand’s prevalence the third highest, behind JUUL and SMOK, with a prevalence of 8% (8% = 30% of 28%, which is the size of the Other category).

Prevalence level significantly different across years at P < .05 for a 2-tailed test, as indicated by 95% CIs that do not include 0.

Students who indicated an Other response were asked to write in the name of the brand they used most often. In 2020, 89% (95% CI, 84%-92%) of youth who had vaped nicotine in the past 30 days and indicated use of another brand wrote in a response. Of these, 30% (95% CI, 23%-38%) wrote in Puff Bar or a spelling variant thereof. Therefore, this brand ranks in the top 3, behind JUUL and SMOK, with a prevalence of 8% (8% = 30% of 28%, which is the size of the Other category).

Table 2 presents trends in the perceived accessibility of vaping products; 2020 marks the first year-to-year decline in these measures since they were added to the survey in 2017, although accessibility remains high. The percentage of students who vaped in the past 30 days and reported it would be fairly easy or very easy to obtain a vaping device decreased from 92% in 2019 to 86% in 2020. The percentage who reported they could easily obtain a nicotine solution for vaping decreased from 92% in 2019 to 83% in 2020. Both of these outcomes follow a nonlinear time trend characterized by steady state from 2017 to 2019 and a decline in 2020. Eighty percent reported that they could easily obtain nicotine solutions in flavors other than tobacco or menthol.

Table 2. Percentage of 10th- and 12th-Grade Students Who Vaped Nicotine in the Past 30 Days and Reported Getting Selected Vaping Materials Would Be Fairly Easy or Very Easy, by Year.

| Variable | Students, % (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Vaping device | Nicotine solution for vaping | Flavored nicotine solution | |

| 2017 | 93.7 (91.2 to 95.4) | 94.6 (92.1 to 96.3) | NA |

| 2018 | 94.5 (92.6 to 95.9) | 93.7 (91.7 to 95.2) | NA |

| 2019 | 93.0 (91.1 to 94.5) | 92.1 (90.0 to 93.8) | NA |

| 2020 | 86.4 (82.7 to 89.3)a | 83.0 (78.5 to 86.7)a | 79.8 (74.9 to 83.9) |

| Logistic regression results for predicted valuesb | |||

| Year | 0.4 (−0.1 to 0.9) | 0.2 (−0.3 to 0.7) | NA |

| Year2 | −0.2 (−0.4 to −0.1) | −0.2 (−0.4 to −0.1) | NA |

| Constant | 2.7 (2.3 to 3.0) | 2.8 (2.4 to 3.2) | NA |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Prevalence level significantly different from previous year at P < .05 for a 2-tailed test.

Year is centered at 2017 and coefficients are unexponentiated. All curvature coefficients (Year2) are statistically significant at P < .05 for a 2-tailed test, as indicated by 95% CIs that do not include 0.

The survey also asked students what flavors they vape most often (results are not reported in the tables). Among students who had vaped nicotine in the last 30 days, students reported using a fruit flavor (eg, mango or strawberry) most frequently at 59.3% (95% CI, 55.2%-63.3%), followed by mint at 26.9% (95% CI, 23.8%-30.3%). Menthol prevalence was 7.2% (95% CI, 5.5%-9.3%), tobacco was 2.9% (95% CI, 2.0%-4.1%), sweet (eg, chocolate and crème) was 2.4% (95% CI, 1.6%-3.5%), and unflavored was 1.4% (95% CI, 0.9%-2.2%).

Table 3 presents trends in perceived risk of nicotine vaping. The percentage of students who perceived great harm from occasional nicotine vaping significantly increased from 21% in 2019 to 27% in 2020, which continues an increase that began in 2018. Perceived risk of regular nicotine vaping also significantly increased from 39% in 2019 to 49% in 2020, again continuing an increase that began in 2018. Both of these outcomes follow a nonlinear time trend of a steady state from 2017 to 2018 followed by an increase in 2019 to 2020.

Table 3. Percent of 10th- and 12th-Grade Students Who Report Perceived Risk of Great Harm From Occasional and Regular Nicotine Vaping, by Year.

| Variable | Students, % (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Occasional nicotine vaping | Regular nicotine vaping | |

| 2017 | 16.7 (15.6 to 17.8) | 28.6 (27.2 to 30.0) |

| 2018 | 16.9 (15.9 to 18.1) | 29.7 (28.3 to 31.1) |

| 2019 | 20.9 (19.6 to 22.3)a | 39.0 (37.4 to 40.7)a |

| 2020 | 27.2 (24.8 to 29.9)a | 49.3 (46.5 to 52.0)a |

| Logistic regression results for predicted valuesb | ||

| Year | −0.03 (−0.2 to 0.1) | 0.04 (−0.1 to 0.2) |

| Year2 | 0.1 (0.03 to 0.1) | 0.1 (0.04 to 0.1) |

| Constant | −1.6 (−1.7 to −1.5) | −0.9 (−1.0 to −0.9) |

Prevalence level significantly different from previous year at P < .05 for a 2-tailed test.

Year is centered at 2017 and coefficients are unexponentiated. All curvature coefficients (Year2) are statistically significant at P < .05 for a 2-tailed test, as indicated by 95% CIs that do not include 0.

Sensitivity Analyses

eTables 6 to 13 in the Supplement report results from sensitivity tests that reran analyses for all tables and figures restricting data in all years to data collected on or before March 14, 2020, when 2020 data collection halted. Prevalence levels in these analyses were markedly similar to those calculated with the full samples, which supports data collected early in the data collection cycle as a smaller, representative sample of the target population, at least for the outcomes of this study.

An additional sensitivity analysis (results not shown) tested multiplicative interaction terms of grade and year for each of the study’s 17 main outcomes. In only 1 case did the interaction term reach statistical significance at the .05 level. About 1 of 20 tests at the P < .05 level would be expected to reach statistical significance by chance alone. These results suggest that the results were similar for 12th- and 10th-grade students.

Discussion

A halt to the increases in adolescent nicotine vaping since 2017 took place in early 2020. Past 30-day, past 12-month, and lifetime nicotine vaping held steady in 2020 at 22%, 32%, and 41%, respectively, after record increases the previous 2 years. Daily nicotine use, defined as use on 20 or more days in the last 30 days, significantly declined from 9% to 7%.

One major candidate factor that may have contributed to this leveling are increases in perceived risk of nicotine vaping. Increases in the perceived risk of using a substance often precede that substance’s decline in population prevalence, as has been previously demonstrated for combustible cigarettes and marijuana use among youth.10 In this case, the increases in perceived risk from 2018 to 2019 may have played a role in slowing the increase of nicotine vaping in 2020, and the increase in perceived risk from 2019 to 2020 could provide a tailwind for decreases in population nicotine vaping next year. Potential drivers of the increase in perceived risk of nicotine vaping include the widely publicized depictions of adverse health effects associated with vaping in the EVALI epidemic4 during the summer of 2019, as well as ongoing national media campaigns warning adolescents of the potential dangers of nicotine vaping.12,13

Another factor that may have contributed to the leveling is decreased accessibility to vaping products. In 2020, the percentage of adolescents who reported they could fairly easily or very easily get vaping devices significantly declined from 92% to 86%. This percentage for vaping nicotine solutions also significantly fell from 92% to 83%. One potential driver of this decrease is the Tobacco 21 legislation that was designed to restrict adolescent access to all tobacco products, including e-cigarettes. Another potential driver may be industry and FDA efforts to restrict adolescent access to vaping flavors such as mint and fruit.

One question these results raise is why newly enacted industry self-regulation and FDA regulations aimed at restricting flavored vaping products did not have greater effect. Despite such regulations, in 2020, mint and fruit flavors, both of which were targeted by regulations, were by far the most common flavors used among students who vaped in the past 30 days. In addition, more than 80% of students who vaped in the past 30 days reported that they could easily get vaping flavors other than tobacco and menthol.

The study results on vaping brands provide insight into how efforts to restrict access to vaping flavors fared. On the one hand, efforts by some individual companies appear to have been successful in reducing adolescent use of their product. Of particular importance is JUUL Labs, which had the largest market share for vaping products in 2019. It announced in November 2019 that it would voluntarily self-regulate and stop selling all flavors other than tobacco and menthol in light of evidence that other flavors such as mint and mango that it had previously sold were the most commonly used flavors among adolescents.7 The results from this study show that adolescent use of JUUL subsequently dropped dramatically. In just 1 year, daily JUUL use, defined as using JUUL on 20 or more days in the past 30 days, dropped 3 fold from 6% to 2%, past 30-day JUUL use dropped by a relative 40% from 20% to 13%, and past 12-month JUUL use significantly declined from 29% to 21%. In all, the results for this individual company are consistent with the strategy that restrictions on flavors can help lead to reductions in adolescent vaping.

On the other hand, efforts to restrict adolescent access to vaping flavors across all brands were not as successful. The FDA imposed broad regulations on vaping flavors and issued a guidance stating that all companies that did not cease manufacture and sale of cartridge-based vaping devices with flavors other than tobacco or menthol would risk enforcement actions. This regulation went into effect on February 7, 2020, 4 days before MTF’s first school survey on February 11, 2020. Not covered by this policy were new, low-priced disposable vaping devices similar in appearance to JUUL, which in the summer of 2019 were just beginning to enter the market.14

Some adolescents were able to continue using vaping flavors in part because they switched away from the cartridge-based vaping devices such as JUUL, for which flavors were not readily available, and moved to newer, disposable vaping devices that come in a variety of vaping flavors and surged in sales15 after JUUL’s decision to discontinue selling flavors other than tobacco and menthol. While JUUL prevalence among youth who vaped in the past 30 days fell an absolute 18 points in 2020, this decline was offset in part by an absolute increase of 8 points in Puff Bars, a disposable brand that comes in wide variety of flavors other than tobacco and menthol. These results suggest that restricting access to vaping flavors among adolescents in the context of a rapidly shifting landscape of vaping products may require continual updates to associated regulations and/or their enforcement, such as the recent FDA action ordering Puff Bar and other manufacturers of disposable vaping devices to remove their flavored products from the market.16

In sum, the rapid acceleration of adolescent nicotine vaping stagnated in early 2020, with past 30-day and past 12-month vaping holding at steady levels and daily nicotine vaping declining. Major candidate drivers of this halt include changes in perceived risk of vaping, which significantly increased in 2019 and 2020, as well as changes in adolescent accessibility to vaping products, which significantly declined in 2020. That being said, perceived risk of nicotine vaping ranks near the bottom for all substances among adolescents,10 and more than 80% of adolescents reported they can easily get vaping products, including flavors other than tobacco and menthol. Substantial room for progress remains.

Limitations

One potential limitation of this study is that data collection stopped prematurely in 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Fortunately, the sample size of 8660 students from 74 schools is large enough to support detailed statistical analysis, the surveyed schools covered a wide geographic range that includes schools in each of the 9 US Census geographic divisions, and the 2020 sample matches closely the 2019 sample in terms of demographics and key levels of substance use (eTables 2 and 3 in the Supplement). In addition, sensitivity analyses that restricted MTF data in all years to surveys collected on or before March 14, the date when MTF data collection stopped in 2020, document prevalence levels markedly similar to results calculated with the full samples (eTables 7 to 13 in the Supplement). This finding supports data collected early in the data collection cycle as a smaller, representative sample of the target population, at least for the outcomes of this study.

A second, related limitation is that adolescent vaping behaviors and perception may have changed after data collection stopped on March 14, 2020, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, it is important to emphasize that the results of this study generalize to the prepandemic period of 2020 and not necessarily afterwards, which is an important focus for future research.

A third limitation is that the MTF sample does not include individuals who dropped out of high school. The study’s sensitivity analysis showing that the results did not significantly differ across 12th and 10th grade suggests that these individuals do not account for the main study findings, given that levels of high school dropout in 10th grade are small.17

Conclusions

Increasing US adolescent nicotine vaping trends from 2017 to 2019 halted in 2020, including a decline in daily vaping. Decreases in perceived accessibility of some vaping products, as well as increases in perceived risk of nicotine vaping, occurred from 2019 to 2020. Yet, adolescent nicotine vaping remains highly prevalent, flavors remain highly accessible, and declines in JUUL use were countered by increased use of other brands.

eFigure. Demographics and Use Levels of Selected Substances in 2020 and Previous Years among U.S. 10th and 12th Grade Students

eTable 1. Survey Question Wording, Response Categories, and Sample Sizes

eTable 2. Comparison of Demographics in 2020 with Previous Years among U.S. 10th and 12th Grade Students

eTable 3. Comparison of Lifetime Use Levels of Selected Drugs in 2020 with Previous Years among U.S. 10th and 12th Grade Students

eTable 4. Observed Prevalence of Nicotine Vaping by Year and Reporting Interval, and Coefficients for Predicted Values

eTable 5. Prevalence of JUUL Use by Year and Reporting Interval

eTable 6. Sample Sizes by Survey Question and Year for Surveys Collected on March 14th or Earlier in All Years

eTable 7. Comparison of 2020 Demographics with Previous Years among U.S. 10th and 12th Grade Students, Samples in All Years Limited to Surveys Collected on March 14 or Earlier

eTable 8. Comparison of Lifetime Use Levels of Selected Drugs in 2020 with Previous Years among U.S. 10th and 12th Grade Students, Samples in All Years Limited to Survey Collected on March 14 or Earlier

eTable 9. Observed Prevalence of Nicotine Vaping by Year and Reporting Interval for Surveys Collected on March 14th or Earlier in All Years

eTable 10. Prevalence of JUUL Use by Year and Reporting Interval for Surveys Collected on March 14th or Earlier in All Years

eTable 11. Prevalence of Vaping Brands Reported Most Often Used among 10th and 12th Grade Students Who Vaped Nicotine in the Past 30 Days for Surveys Collected on March 14th or Earlier in All Years, by Year

eTable 12. Percent 10th and 12th Grade Students Who Vaped Nicotine in the Past 30 Days and Reported Getting Selected Vaping Materials Would Be “Fairly Easy” or “Very Easy” for Surveys Collected on March 14th or Earlier in All Years, by Year

eTable 13. Percent of 10th and 12th Grade Students Who Report Perceived Risk of “Great Harm” from Occasional and Regular Nicotine Vaping for Surveys Collected on March 14th or Earlier in All Years, by Year

References

- 1.Miech R, Johnston L, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Patrick ME. Trends in adolescent vaping, 2017-2019. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(15):1490-1491. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1910739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarette Use. The National Academies Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krishnasamy VP, Hallowell BD, Ko JY, et al. ; Lung Injury Response Epidemiology/Surveillance Task Force . Update: characteristics of a nationwide outbreak of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury: United States, August 2019-January 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(3):90-94. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6903e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.FDA finalizes enforcement policy on unauthorized flavored cartridge-based e-cigarettes that appeal to children, including fruit and mint. Press release. US Food and Drug Administration; January 2, 2020. Accessed November 25, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-finalizes-enforcement-policy-unauthorized-flavored-cartridge-based-e-cigarettes-appeal-children

- 6.Cullen KA, Gentzke AS, Sawdey MD, et al. . E-cigarette use among youth in the United States, 2019. JAMA. 2019;322(21):2095-2103. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.18387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leventhal AM, Miech R, Barrington-Trimis J, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Patrick ME. Flavors of e-cigarettes used by youths in the United States. JAMA. 2019;322(21):2132-2134. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Newly signed legislation raises federal minimum age of sale of tobacco products to 21. Press release. US Food and Drug Administration; January 15, 2020. Accessed November 25, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/ctp-newsroom/newly-signed-legislation-raises-federal-minimum-age-sale-tobacco-products-21

- 9.Bachman JG, Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Miech RA. The Monitoring the Future Project after four decades: design and procedures. Institute for Social Research; 2015. Accessed November 17, 2019. http://monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/occpapers/mtf-occ82.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miech RA, Johnston L, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975-2018. Institute for Social Research; 2019. Accessed November 17, 2019. http://monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-vol1_2018.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miech RA, Johnston L, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975-2019. Institute for Social Research; 2020. Accessed November 17, 2019. http://monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-vol1_2019.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 12.FDA In Brief: FDA expands youth e-cigarette prevention campaign to include stories from teenagers addicted to nicotine. Press release. US Food and Drug Administration; January 21, 2020. Accessed November 25, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/fda-brief/fda-brief-fda-expands-youth-e-cigarette-prevention-campaign-include-stories-teenagers-addicted

- 13.Truth confronts JUUL and other e-cigarette manufacturers in new campaign, 'tested on humans'. Press release. Cision PR Newswire. August 26, 2019. Accessed November 25, 2020. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/truth-confronts-juul-and-other-e-cigarette-manufacturers-in-new-campaign-tested-on-humans-300906492.html

- 14.Williams R The rise of disposable JUUL-type e-cigarette devices. Tob Control. Published online December 5, 2019. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liber A, Cahn Z, Larsen A, Drope J. Flavored E-cigarette sales in the United States under self-regulation from January 2015 through October 2019. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(6):785-787. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.FDA notifies companies, including Puff Bar, to remove flavored disposable e-cigarettes and youth-appealing e-liquids from market for not having required authorization. Press release. US Food and Drug Administration; July 20, 2020. Accessed November 25, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-notifies-companies-including-puff-bar-remove-flavored-disposable-e-cigarettes-and-youth

- 17.United States Census Bureau. School enrollment in the United States: October 2018: detailed tables. Published December 3, 2019. Accessed November 25, 2020. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2018/demo/school-enrollment/2018-cps.html

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Demographics and Use Levels of Selected Substances in 2020 and Previous Years among U.S. 10th and 12th Grade Students

eTable 1. Survey Question Wording, Response Categories, and Sample Sizes

eTable 2. Comparison of Demographics in 2020 with Previous Years among U.S. 10th and 12th Grade Students

eTable 3. Comparison of Lifetime Use Levels of Selected Drugs in 2020 with Previous Years among U.S. 10th and 12th Grade Students

eTable 4. Observed Prevalence of Nicotine Vaping by Year and Reporting Interval, and Coefficients for Predicted Values

eTable 5. Prevalence of JUUL Use by Year and Reporting Interval

eTable 6. Sample Sizes by Survey Question and Year for Surveys Collected on March 14th or Earlier in All Years

eTable 7. Comparison of 2020 Demographics with Previous Years among U.S. 10th and 12th Grade Students, Samples in All Years Limited to Surveys Collected on March 14 or Earlier

eTable 8. Comparison of Lifetime Use Levels of Selected Drugs in 2020 with Previous Years among U.S. 10th and 12th Grade Students, Samples in All Years Limited to Survey Collected on March 14 or Earlier

eTable 9. Observed Prevalence of Nicotine Vaping by Year and Reporting Interval for Surveys Collected on March 14th or Earlier in All Years

eTable 10. Prevalence of JUUL Use by Year and Reporting Interval for Surveys Collected on March 14th or Earlier in All Years

eTable 11. Prevalence of Vaping Brands Reported Most Often Used among 10th and 12th Grade Students Who Vaped Nicotine in the Past 30 Days for Surveys Collected on March 14th or Earlier in All Years, by Year

eTable 12. Percent 10th and 12th Grade Students Who Vaped Nicotine in the Past 30 Days and Reported Getting Selected Vaping Materials Would Be “Fairly Easy” or “Very Easy” for Surveys Collected on March 14th or Earlier in All Years, by Year

eTable 13. Percent of 10th and 12th Grade Students Who Report Perceived Risk of “Great Harm” from Occasional and Regular Nicotine Vaping for Surveys Collected on March 14th or Earlier in All Years, by Year