Abstract

Reactor neutrino experiments have seen major improvements in precision in recent years. With the experimental uncertainties becoming lower than those from theory, carefully considering all sources of is important when making theoretical predictions. One source of that is often neglected arises from the irradiation of the nonfuel materials in reactors. The rates and energies from these sources vary widely based on the reactor type, configuration, and sampling stage during the reactor cycle and have to be carefully considered for each experiment independently. In this article, we present a formalism for selecting the possible sources arising from the neutron captures on reactor and target materials. We apply this formalism to the High Flux Isotope Reactor (HFIR) at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, the source for the the Precision Reactor Oscillation and Spectrum Measurement (PROSPECT) experiment. Overall, we observe that the nonfuel contributions from HFIR to PROSPECT amount to 1% above the inverse beta decay threshold with a maximum contribution of 9% in the 1.8–2.0 MeV range. Nonfuel contributions can be particularly high for research reactors like HFIR because of the choice of structural and reflector material in addition to the intentional irradiation of target material for isotope production. We show that typical commercial pressurized water reactors fueled with low-enriched uranium will have significantly smaller nonfuel contribution.

I. INTRODUCTION

Many experiments have been performed to measure the electron antineutrino flux and spectrum from nuclear reactors over the past several decades to advance our knowledge of the standard model. Nuclear reactors are intense sources of ; approximately six per fission are produced, resulting in the emission of ≈ 1020 s−1 by a 1 gigawatt electric (GWe) commercial light water reactor. Typically, detectors are placed near nuclear reactors to detect via the inverse beta decay (IBD) reaction. Many experiments have been conducted at commercial nuclear reactors with baselines ranging from tens of meters to hundreds of kilometers. Recent interest in the search for sterile neutrino oscillations has motivated a new series of short-baseline experiments. The need for close proximity to a compact source and the desire to measure the production from individual fissile isotopes make research reactors an excellent choice for these experiments [1]. An outline of major neutrino experiments can be found in Ref. [2].

The detection of at a nuclear reactor is dependent on many parameters of the reactor and detector systems [3]:

| (1) |

where is the number of neutrinos detected in the active volume, Nprot is the number of target protons in the detector, σIBD is the energy-dependent IBD cross section, η is a detector efficiency parameter, P is the oscillation survival probability, and L is the distance from fission site to IBD interaction position. The last differential term accounts for the magnitude and relative change in the emitted spectrum from the source:

| (2) |

where f is the fission rate of isotope i and the is the spectrum of that isotope.

If the focus turns to the reactor as the source with the fission rate of Equation 2 analogous to power, Equation 1 reduces to a simple calculation of the detected [4]:

| (3) |

where γ takes into account all detector properties, Pth is the thermal power of the reactor, and k(t) takes into account the change in flux due to isotopic evolution. The Daya Bay [3, 5] and RENO [6] collaborations have investigated and quantified this k(t) term for commercial reactors. The detected rate is proportional to reactor power. There exists variation in the signal due to the evolution of isotope fission fractions with fuel burnup, depending on the reactor.

The proportionality of detected rate to reactor power has been observed in many reactor experiments, most recently Daya Bay [3, 5], Double Chooz [7], and RENO [6], all of which focused on measuring disappearance. However, re-evaluation of theoretical predictions [8-10] in preparation for these experiments lead to a 6% deficit of the observed flux, the “reactor antineutrino anomaly.” Additionally, the shape of the overall spectrum does not agree with predictions with an excess in the 5–7 MeV range, known as the “bump,” as the most prominent feature. Causes of these phenomena could be new physics in the form of sterile neutrinos [8] or incomplete treatment of the complex nature of nuclear reactions and decays in the predictions or both [11-14].

Previous work has addressed some aspects of reactor design and operation as they affect the reactor spectrum. The effect of “nonequilibrium” isotopes, i.e., fission products that have not reached equilibrium contributions, factored in irradiation time as a variable in reactor operation, impacting comparisons with the aggregate beta spectra measured at the Institut Laue-Langevin (ILL) reactor [15-17]. Another observation is the contribution from neutron capture on fission products [17, 18]. Similarly, the contributions from stored spent fuel have been studied [19, 20]. However, the exact contribution of from nonfission products, primarily via thermal neutron capture on reactor materials, has yet to be addressed. Huber and Jaffke discussed the contributions on nonequilibrium isotopes, but this effect was examined for neutron capture on fission products only [18]. These contributions can be additional terms in Equation 2:

| (4) |

where the contribution from nonequilibrium isotopes, cine, is a correction factor to the isotope spectra. The contribution from spent nuclear fuel, sSNF, and the nonfuel activations, aN F, are additional terms. Note that all these additional contributions are highly reactor-specific and time dependent. Most modern reactor experiments account for the time dependent cine and sSNF but do not account for aNF because it has been underexplored or considered to be a trivial contribution [12].

The goal of this paper is to develop a formalism for determining the nonfuel candidates that produce above the IBD threshold. The Precision Reactor Oscillation and Spectrum Measurement (PROSPECT) experiment at the High Flux Isotope Reactor (HFIR) at Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) is used as a case study to apply this formalism. The unique configuration of this research reactor provides an opportunity to highlight materials and processes that can make non-negligible contributions to the total emitted spectrum. Research reactors typically have very different design and missions compared to commercial nuclear reactors, which results in significantly different nonfuel contributions. The formalism defined here can be used by all the reactor experiments, but it is particularly important for the experiments using research reactors like PROSPECT [21], STEREO [22], and SoLid [23] to account for the nonfuel contributions in their predictions.

There has been increased interest in measuring the coherent elastic neutrino-nucleus scattering (CEνNS) reaction using reactors as a source after a first measurement of this reaction by the COHERENT experiment [24]. Using reactors as the source measuring the CEνNS requires an update in the predicted spectrum below the IBD threshold, which has not been given much attention so far [25]. Because nonfuel sources of primarily contribute at low energies, including these contributions in the predictions is critical. The methodology provided here can be individually used by each experiment to predict the spectrum provided by the reactor.

Section II outlines the methodology for selection of candidates for nonfuel emissions in a nuclear reactor, and this methodology can be applied to any reactor. Section III presents HFIR as a case study for the selection process. A list of candidate isotopes are considered for HFIR, and the details of those isotopes in the reactor are discussed with the materials grouped into three general categories: structural, reflector, and target. Section IV discusses the reactor modeling methodology and its uncertainty considerations. In Section V, reactor modeling to obtain reaction rates and conversion to spectrum are performed. Section VI discusses the extension of this work to commercial nuclear power plants, and Section VII contains the conclusions. Finally, Section VIII contains a list of relevant acronyms.

II. NONFUEL PRODUCTION OF ANTINEUTRINOS

This section discusses a procedure for selection of nonfuel sources in a reactor. One feature of reactor sources that has sometimes been neglected is the emission from nonfuel materials. The design and operation of certain reactors require specific considerations for nonfuel materials. Nonfission reactions, such as neutron capture, can generate beta-decaying products that are accompanied by . These from fission sources are an additional contribution that must be considered for precision measurements at certain classes of reactors. The contribution of these nonfuel sources needs to be taken into account in predictions.

The isotopes of most concern for predicting an accurate fission spectrum would be those that contribute to the flux coming from the core materials, which alters the fission spectrum. Neutron capture reactions—such as (n,γ), (n,2n), or (n,p)—release significantly less energy than fission reactions; therefore they contribute negligibly to the core power. production that is not tracked via the power level disrupts the predicted linear relationship between detected and power level [26]. The isotope content of all nonfuel materials in or near the reactor core must be evaluated for their ability to produce . The isotopes with significant contributions will be referred to as “antineutrino candidates.” Here, reaction rates greater than 0.1% of the fission rate are considered significant.

To contribute significantly to the spectrum, the combination of parent and daughter isotopes of the neutron capture reaction must fulfill certain criteria. These criteria serve to identify potential contributors to the antineutrino flux. Each isotope needs to fulfill all criteria, but in some cases unmet criterion are balanced by enhancements in other criteria.

First, an antineutrino candidate must have a relatively high concentration in the core. It cannot be contained in trace amounts or be infrequently irradiated in the core. This criterion ensures a sufficient number of target atoms for neutron capture. In addition, a high abundance in the core relative to other isotopes is ideal to maximize the number of target atoms. No quantitative criteria is given here. Although commercial reactors have a smaller number of isotopes present in the core, many isotopes can be considered for research reactors.

Second, the neutron-induced reaction of interest must have a non-negligible neutron cross section to produce the daughter. The reaction of interest is almost always neutron capture (i.e., X followed by γ emission), but reactions that result in the ejection of other particles (e.g, α, 3H, etc.) also can result in daughter isotopes prone to β− decay. Because the neutron-induced reaction rate of an isotope i (Ri) is a product of the parent isotope concentration (Np) and energy-dependent neutron cross section (σi) and neutron flux (ϕ), the second criteria seeks to have a maximum of this product:

| (5) |

For example, a structural material has a relatively high atomic concentration in the core but a relatively low cross section, whereas neutron poisons for reactivity control have the inverse characteristic. Both of these can still be considered as candidates due to the product of concentration and cross sections. In this work, a non-negligible cross section is defined to be greater than 0.1 barns, although some exceptions are made because of the combination of criteria one and two. Because most experiments have occurred at thermal reactors, thermal neutron-induced reaction are primarily considered here. The mean energy of thermal neutrons in a nuclear reactor is 0.0253 eV, for which ENDF/V-VII.1 cross sections can be readily obtained [27]. Fast neutron-induced reactions can be important in certain areas of the core or for fast neutron spectrum reactors, which is beyond the scope of this work.

Third, the daughter product must β− decay with a short half-life relative to the cycle of the reactor so that it is generated with a sufficient activity. If the half-life is too long relative to the reactor cycle length, it will not decay with a high enough frequency. The relative magnitude of half-life to cycle length will determine how quickly, if at all, the activity will reach secular equilibrium with its production rate. Half-lives of up to a certain length relative to the cycle length may be considered depending on the application. For example, isotopes with a half-life two orders of magnitude lower than the cycle length will have their activity saturated for 95% of the cycle. This value will be used for this criterion, although most activated products have half-lives much shorter than this. A short time until an isotope reaches its saturated activity increases the value and decreases the time variation of the contribution.

Fourth, the β− transition of the daughter must release enough energy to be above the IBD threshold of 1.8 MeV . The energy released and final state energy can be retrieved from the Evaluated Nuclear Structure File (ENSDF) database [28] maintained by the National Nuclear Data Center. The IBD threshold requirement is applied to all beta branches of each isotope taking into account the individual abundances. This paper focuses on contributions above the 1.8 MeV IBD threshold; evaluation of nonfuel contributions for detectors sensitive to other reactions should take into account a lower energy threshold, as in Ref. [29].

An isotope that fulfills all of these criteria is considered as an antineutrino candidate. In a reactor, the concentration of the candidate, Ni, from its parent, Np, assumed to be stable and not appreciably burnt out, is equivalent to:

| (6) |

where λi is the decay constant of the daughter isotope (λ = ln2/t1/2). If the decay constant of the product is large (meaning a short half-life) relative to the irradiation period, the decay term quickly declines and the candidate concentration becomes proportional to the time-dependent neutron flux and parent isotope concentration.

For any reactor experiment, the above criteria can be applied to its reactor materials to select non-fissionable isotopes that may contribute significantly to the reactor spectrum. The selection process will result in isotopes that should be considered for reactor analysis and modeling to quantify nonfuel rates. Each reactor can be analyzed based on the materials under consideration.

III. CASE STUDY: HFIR

For this paper, HFIR is used as a case study. As a research reactor, HFIR is smaller than traditional commercial reactors and is not used to generate electricity. It also is fueled with highly enriched uranium, whereas typical commercial reactors are fueled with low-enriched uranium. HFIR currently hosts the PROSPECT detector, which is measuring the flux from HFIR. HFIR is similar in design to other research reactors, such as the National Bureau of Standards Reactor [30, 31], the ILL reactor [32] which hosts the STEREO experiment [22], and the BR2 reactor in Belgium [33] which hosts the SoLid experiment [23]. The study of the nonfuel could be applicable to these other highly enriched uranium reactors.

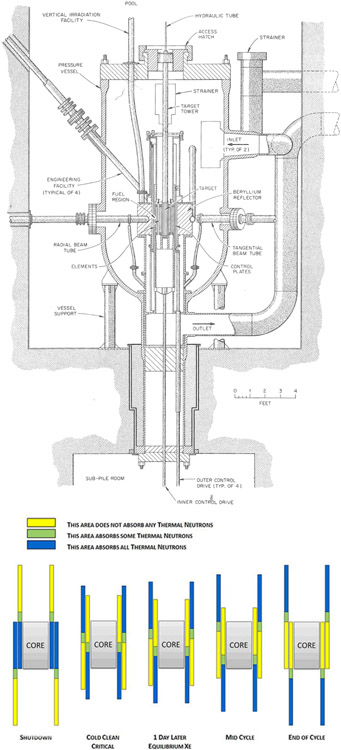

HFIR is a major U.S. research reactor with missions of neutron scattering, isotope production, materials irradiation, and neutron activation analysis [34]. It is one of the few highly enriched uranium–fueled research reactors in the United States and has been operating since 1965. HFIR is a compact reactor that can attain high thermal neutron fluxes—greater than 2 × 1015 cm−2 s−1—in its central region. It nominally operates at a power of 85 megawatts thermal (MWt) for a cycle length of 23–26 days, i.e., 1955–2210 megawatt days (MWd) of operation with seven cycles annually. Figure 1 shows the side view of HFIR.

FIG. 1:

Side view of HFIR with core regions (top) and movement of inner and outer CEs throughout the cycle (bottom).

The central region of the core is the flux trap target (FTT) region. The FTT region contains a total of 37 target positions, which includes 30 interior positions, 6 peripheral target positions, and one hydraulic tube. The contents of the FTT vary from cycle to cycle depending on experimental demand for isotope production and materials irradiation. A model with a representative loading, for example, contains target materials composed of V, Ni (62Ni), Mo, W, Se, Ni, Fe, and Cm [35]. The curium targets are used to produce 252Cf [36], which results in its spontaneous fissions and other neutron-induced fission of higher actinides. In more recent cycles since that report, experiments have included previously mentioned isotopes as well as silicon carbide, steels, and other ferritic alloys. These isotopes are important for PROSPECT, which was deployed in early 2018.

Radially outward of the FTT are the two fuel element regions, the inner and outer fuel elements (IFE/OFE). The fuel is a U3O8-Al dispersion fuel (uranium dispersed in an aluminum matrix) enriched to 93% by mass 235U (5–6% 238U and 1% 236U) and manufactured in the form of involute plates [37]. The fuel region is contoured along the arc of the involute to allow for sufficient thermal safety margin. The IFE contains a burnable poison, 10B, to flatten the power distribution and ensure a longer cycle. The IFE and OFE contain 171 and 369 fuel plates, respectively, and have separate fissile loadings. Fresh IFE and OFE fuel assemblies are loaded into the core for each cycle, unlike most commercial reactors that operate with some previously irradiated fuel elements containing plutonium.

The fuel regions are surrounded by two concentric control elements (CEs). Both control elements are partially inserted at the beginning of cycle (BOC) and are gradually withdrawn in opposite directions throughout the cycle. The inner control element (ICE) is the control cylinder that descends throughout the cycle; the outer control element (OCE) is a set of four safety plates, each of which can individually scram the reactor, move upward throughout the cycle. The CE positions at various points in the cycle are shown in Figure 1. Both control elements contain Eu, Ta, and Al in their absorbing regions [35]. The end of cycle (EOC) occurs when both elements are fully withdrawn and the reactor can no longer maintain criticality. Both the ICE and OCE are replaced approximately every 50 cycles.

The beryllium reflector occupies the outermost radial region and serves to moderate neutrons for reflection back into the active core or transport them down the beam tubes. The reflector region is split up into three regions: the removable (RB), semi-permanent (SPB), and permanent (PB) beryllium regions. The RB is replaced every several years, and the SPB and PB are replaced every few decades. The PB contains 22 vertical experimental facilities (VXFs), including inner small, outer small, and large VXFs. The four horizontal beam tubes (HBs) penetrate the outer radial areas in order to support cold and thermal scattering experiments. Recent cycles have included neptunium oxide (NpO2) targets to produce 238Pu for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) [38-40]. All materials in the various components of the reflector regions are included in the analysis. Because reflector regions are exposed to neutron flux, they build up substantial neutron poisons, primarily 6Li and 3He, over multiple irradiation cycles. Several reactions that produce these poisons and candidates rely on fast neutrons, whereas captures in the structural and target materials occur mostly from thermal neutrons.

The candidate selection process of Section II is applied to the nonfuel materials in HFIR. The reactor is first divided into different regions according to primary function. Then, a mix of publicly available and internal data at HFIR is used to determine average quantities of materials in the core during a typical cycle. The composition of the fuel elements is well documented and outlined in Ref. [35]. The control element (CE) and reflector materials change in composition with increasing irradiation time in the reactor. The target materials have the potential to change each cycle according to user demand; a representative loading of targets in recent cycles is outlined in Ref. [35]. Isotopic constituents of these materials are analyzed according to the four step selection process to generate candidates to be analyzed with reactor modeling. Candidates with contributions of greater than 0.1% are considered because this is the typical statistical uncertainty in reaction rate calculations.

Antineutrino candidate selection process results can be seen in Table I. The β− decays of antineutrino candidates that are to be considered include three main groups. The first is structural materials, which includes 28Al, 55Cr, 66Cu, and 56Mn. The second is the beryllium reflector, which includes 6He and 8Li. The last is the target materials, which include 52V in the FTT and two actinide targets, curium in the FTT, and neptunium in the VXFs. The next step for the antineutrino candidates is to quantify their activities in the reactor, discussed in Section IV, and convert the activities to spectra to compare with the nominal reactor spectrum in Sections V-VII.

TABLE I:

A summary list of the antineutrino candidates in HFIR. The isotopes are grouped in coarse categories according to function or region in the reactor. The requirements for candidate selection previously described are in bold in the second row of the table. The failed criteria for each isotope, if any, is listed in the right-most column.

| El. | A | Abundance (%) |

ENDF/B-VII.1 σ (barns) |

Daughter | t1/2 (s) |

Q (MeV) |

Efinal (MeV) |

Eβ,max (MeV) [Mutliple] |

Criteria Failed |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Requirement | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||||

| High | High | β− decay | Low | High | > 1.8 MeV | |||||

| Structural | Al | 27 | 100.0 | 0.23 | 28Al | 1.34 ×102 | 4.64 | 1.78 | 2.86 | None |

| Fe | 54 | 2.8 | 2.25 | 55Fe | 3 | |||||

| 56 | 91.8 | 2.59 | 56Fe | 3 | ||||||

| 57 | 2.1 | 2.43 | 58Fe | 3 | ||||||

| 58 | 0.3 | 1.00 | 59Fe | 3.84 × 106 | 1.57 | 4 | ||||

| Cr | 50 | 4.3 | 15.40 | 51Cr | 3 | |||||

| 52 | 83.8 | 0.86 | 53Cr | 3 | ||||||

| 53 | 9.5 | 18.09 | 54Cr | 3 | ||||||

| 54 | 2.4 | 0.41 | 55Cr | 2.10 × 102 | 2.60 | 0.00 | 2.60 | None | ||

| Cu | 63 | 69.2 | 4.47 | 64Cu | 3 | |||||

| 65 | 30.8 | 2.15 | 66Cu | 3.07 × 102 | 2.64 | 0.00 | 2.64 | None | ||

| Mg | 24 | 79.0 | 0.05 | 25Mg | 3 | |||||

| 25 | 10.0 | 0.19 | 26Mg | 3 | ||||||

| 26 | 11.0 | 0.19 | 27Mg | 5.73 × 102 | 2.61 | 0.84 | 1.77 | 4 | ||

| Mn | 55 | 100.0 | 13.27 | 56Mn | 9.28 × 103 | 3.70 | Various | [0.250,2.849] | None | |

| Reflector | Be | 9 | 100.0 | 0.04a | 6He | 8.07 × 10−1 | 3.50 | 0.00 | 3.50 | None |

| 10 | trace | 11B | 4.75 × 1013 | 0.55 | 1,2 | |||||

| Li | 7 | 92.41b | 0.04 | 8Li | 8.40 × 10−1 | 16.00 | 3.03 | 12.97 | None | |

| Poisons and CEs | B | 10 | 80.1 | 3842.56 | 7Li | 3 | ||||

| 11 | 19.9 | 0.01 | 3 | |||||||

| Eu | 151 | 47.8 | 9200.73 | 152Eu | 4.22 × 108 | 3 | ||||

| 153 | 52.2 | 358.00 | 154Eu | 2.71 × 108 | 3 | |||||

| Nb | 93 | 7.59 | 1.16 | 94Nb | 6.41 × 1011 | 2.04 | 3 | |||

| Ta | 181 | 99.99 | 8250.44 | 182Ta | 9.89 × 106 | 1.81 | Various | 4 | ||

| Targets (FTT + VXFs) | V | 51 | 99.75 | 4.92 | 52V | 2.25 × 102 | 3.97 | 1.434 | 2.54 | None |

| Mo | 98 | 24.4 | 0.13 | 99Mo | 2.38 × 105 | 1.36 | 4 | |||

| Se | 78 | 23.8 | 0.43 | 79Se | 3 | |||||

| 80 | 49.6 | 0.61 | 81Se | 1.11 × 103 | 1.59 | 4 | ||||

| Ni | 58 | 68.1 | 4.22 | 59Ni | 3 | |||||

| Np | Various | Variousc | None | Variousc | ||||||

| Cm | Various | Variousc | None | Variousc | ||||||

The cross-section listed is in the fast region due to the high energy threshold 9Be(n,α) reaction

With a fresh beryllium reflector, no 7Li is present but it is produced gradually in its lifetime

Np, Cm, and products to which they transmute are fissile and produce fission spectra that have been relatively unexplored

IV. REACTOR MODELING AND SIMULATION

After identifying antineutrino candidates for HFIR, the next step is to quantify the neutron-induced reaction rates in a typical cycle of the reactor. The modeling methodology is to build on a HFIR computer model developed by ORNL staff [35] using the Monte Carlo particle transport code MCNP [41, 42]. This model includes information and advancements from a HFIR Cycle 400 model [43, 44], including explicit modeling of the fuel plates and a representative target loading, and is the basis for neutronic safety and performance calculations at HFIR. Models exist for BOC and EOC as well as in single day time steps for each day of the cycle; the isotopics for each day are calculated from the VESTA depletion code [45].

Reaction rate calculations are added in MCNP to obtain the energy-dependent neutron flux and reaction rates in user-defined, discrete cells containing the isotope of interest, and phantom materials (described in Ref [42]) are added to obtain isotope-dependent reaction rates. The lack of phantom materials in a tally results in total reaction rates in a cell (e.g. for fission rates in a fuel cell summed over those for 235U, 238U, 239Pu, 241Pu). MCNP cells are user-defined according to regions bound by surface descriptions (e.g., planes, spheres, cylinders). Volumes of these cells range from less than 1 cm3 for fuel and some flux trap cells to hundreds of cubic centimeters for reflector regions. Tally results in MCNP are reported per unit source particle (e.g., neutron). To normalize to absolute rates for comparison with fission rates, the power normalization factor (PNF), expressed in terms of a neutron rate in units seconds−1, sometimes called the source term S, [46, 47] is used:

| (7) |

where P is the thermal power of the reactor, ν is the number of neutrons generated per fission, keff is the criticality eigenvalue reported in MCNP, and Qfiss is the energy released per fission. Typical values for ν are 2.4 for 235U and 2.9 for 239Pu. keff is unity for a critical reactor. The Qfiss is close to 200 MeV for uranium and plutonium isotopes [48, 49]. The PNF in HFIR MCNP simulations is assumed to be accurate because the models result in eigenvalues close to unity (with small statistical error) and the energy dependence of ν and Qfiss are negligible for each fissile isotope [50]. Owing to the constant power and little fuel evolution, the PNF changes by 0.1% throughout a cycle and is therefore considered to be constant.

The goal is to calculate the core reaction rate Rcore for each candidate for each isotope i for each cell j in the model, combining Equation 5 in discretized form and Equation 7:

| (8) |

so the atomic concentration of the isotope Ni in the cell Mi is multiplied by the integral, i.e., the output of the MCNP reaction rate tally. Given a low half-life of the product and low time variation of the reaction, the core production rate is approximately equal to its activity early into the cycle, i.e.,

| (9) |

If not replaced every cycle, some of the candidates evolve in concentration throughout several cycles. When necessary, the COUPLE and ORIGEN (Oak Ridge Isotope Generation) modules in the SCALE modeling and simulation suite [51] are used for production, depletion, and decay of these isotopes. The COUPLE and ORIGEN sequences are also used for other isotopes as a cross-check to verify constant concentration (dNi/dt ≈ 0) within the duration of the cycle. For COUPLE/ORIGEN, an energy group-dependent neutron flux, total flux, and BOC cell isotope concentrations are required inputs. These inputs are obtained from the MCNP outputs, which are generated for each day in the cycle. The MCNP cases provide the group-spectra using a 44-group energy structure, a collapsed version of the commonly used 238-group structure used in neutron activation problems [51]. Therefore, the MCNP stand-alone and MCNP combined with ORIGEN inputs are not expected to differ substantially unless the parent isotope has undergone significant transmutation. Note that MCNP uses continuous energy cross sections based on ENDF whereas the multi-group COUPLE/ORIGEN approach was based on using the MCNP binned flux spectrum and JEFF for generating one-group cross sections.

The missions, design, and operation of HFIR allow for a large number of materials to be present and irradiated during a given cycle. In searching for candidate isotopes that could contribute to the spectrum, all areas of the reactor discussed previously were considered. This includes isotopes in the materials that make up the structural, control element, and reflector regions in addition to the large variety of target materials that can be in the FTT positions or VXFs in the reflector region.

The modeling and simulation provide high-precision calculations of the isotope-dependent fission rates in the core. The fission rate changes negligibly from 2.64 × 1018 to 2.65 × 1018 s−1 from BOC to EOC due to the evolution of the power distribution and gamma radiation. The fission fraction of 235U remains above 99.5% throughout the cycle. The fission rate is important in determining the production from fission versus candidates.

The uncertainty in such reactor model predictions arises from a variety of components. These include, but are not limited to, the uncertainty in (1) model creation such as the precision to which geometry and material compositions are known, (2) nuclear data, and (3) the modeling methodology itself. In the first case, HFIR has a consistent loading except for target and reflector compositions, which change from cycle to cycle. The variation is expected to be small becasue of consistent fuel loading and power distribution within the core. Previous analysis specific to HFIR have found that geometries and isotope concentrations of reactor components agree well with engineering drawings and material specifications, but note that the impurity levels among fabrications may vary which can result in changes in isotope concentrations in components in reality compared to those modeled [34, 52]. Note, the model detail level is higher in the fuel and near experiments of interest as these calculations served to provide precise neutron flux values. Therefore the uncertainty associated with model isotope concentrations is assumed to be ≤ 1%. Regarding nuclear data, for most reactions induced by thermal neutrons, the uncertainties in cross sections vary from 0.1% to 0.5% for well-known isotopes and several percent for isotopes with more uncertain cross sections. Isotope concentration uncertainties, and thereby reaction rates, in time-dependent calculations can be low for actinides but tens of percent for some fission products [53]. Most of the candidate isotopes in this study have uncertainties on the lower side of that range. The third type is the uncertainty from the methodology itself. In the past two decades, Monte Carlo codes have been increasingly used for neutron transport calculations, and the uncertainty associated with the methodology itself is largely statistical. With recent improvements in computational power during the past decade, statistical uncertainties can be obtained at the subpercent level for flux and reaction rates. In codes predominantly used for reactor analysis, such as MCNP and SCALE, isotope concentration uncertainties have been validated to several percent or better for many benchmarking problems [54, 55]. In short, the propagation of uncertainty in reactor simulations is not straightforward and has several considerations. However, the uncertainty associated with reactor calculations is expected to be tenths of a percent to several percent depending on the isotope. In addition, larger uncertainties exist outside the scope of reactor simulation uncertainties, such as the precision of the reactor power level [56, 57].

V. CALCULATION OF NONFUEL EXCESS IN SPECTRUM

The goal of this section is to take the reaction rates calculated from the previous section and convert to spectra for candidates of interest. The Oklo nuclide tool kit [58] is used to generate for 235U and the candidates. Oklo uses transition and energy level data from ENSDF-6 [28] and cumulative fission yield data from the and Evaluated Nuclear Data File (ENDF) [27]. Both of these are combined to calculate spectra from fissile isotopes. The Oklo calculation for spectra includes terms and corrections from several sources [9, 59, 60]. The ENSDF data alone can be used to generate spectra for individual β− decays. Summation predictions of spectra, such as those produced by Oklo, can have uncertainties as high as 10% [61].

The most commonly used reference reactor spectrum is that generated by Huber via conversion of experimentally measured a reactor electron spectrum [9]. The 235U spectra generated by Oklo from Huber have small differences. The most notable differences are in the lower energies (below the IBD threshold) and therefore not of primary interest for this work. The theoretical predictions from Oklo return the fission spectra in 10 keV bins.

The end product is a prediction of the excess that are produced from candidates with respect to those from fuel fissions. The excess from candidates is calculated by taking the ratio of reaction rate of candidate X to the 235U fission rate and multiplying by the ratio of produced per reaction above the IBD threshold :

| (10) |

In this equation, is the number of produced above the IBD threshold per reaction. Because the fission rate is the most frequent neutron-induced transmutation in a reactor and the fact that fission always produces more than a single β− decay, both ratios will always be less than unity. The result will be a fraction, or excess, of above threshold produced by the candidate versus those from the fission process.

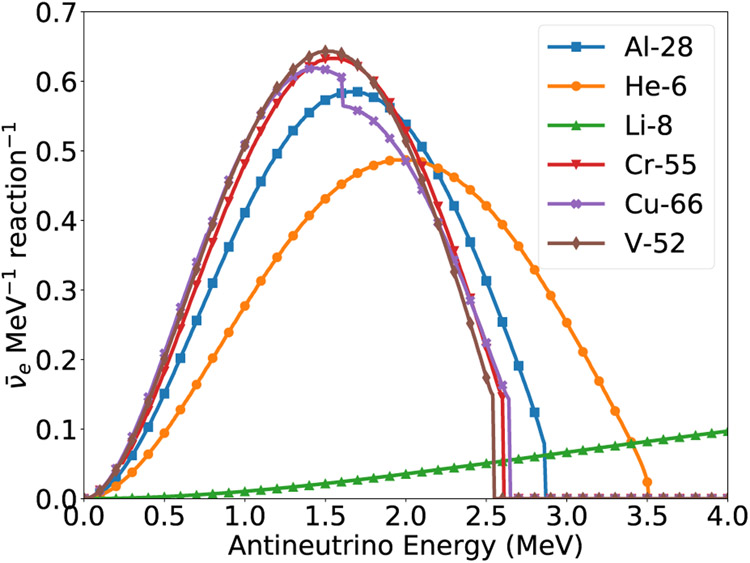

Figure 2 shows the spectra for the nonfissile candidates (i.e., not including NpO2 and curium oxide [CmO] targets) from a single β− decay, i.e., the spectra in Equation 10. Lithium-8 is the only candidate with a endpoint above 3.5 MeV. The 66Cu distribution experiences a dip because there is a 9% branch that ends at 1.6 MeV. Most distributions have an average energy lower than the IBD threshold. The two exceptions are 6He and 8Li, the two products produced in the beryllium reflector.

FIG. 2:

Probability density function of for nonfission candidates. Note that 66Cu (purple x) has an additional 9% β− branch not mentioned in Table I, and the 8Li (green triangle) endpoint is approximately 13 MeV.

The next several sections discuss each of the relevant candidates in detail, quantify their decay rates in the reactor as a function of time, and calculate the antineutrino spectrum. Some candidates will then be eliminated from consideration. The elements are grouped into three sections according to purpose listed in Table I: structural (Section V A), reflector (Section VB), and targets (Section V C). Reaction rates and activites are calculated in these sections. The conversion to spectrum and contributions of these isotopes relative to the fission spectrum is discussed in Section V D.

A. Structural

The most prominent structural materials in HFIR include Al, Cu, Cr, and Mn. Aluminum is included in the form of Al-6061, Al-1100, and several others. When HFIR was designed, aluminum was selected because of its low fabrication and reprocessing costs [34]. It also has a lower reactivity penalty than other structural materials; the only exception is zirconium, which is typically more expensive but more often used in commercial reactors as cladding. Copper, chromium, and manganese are present in much lower quantities in the core than aluminum.

1. Aluminum

Aluminum is the most prominent structural material in HFIR. The natural abundance of aluminum is 100% 27Al. In the FTT region, aluminum makes up dummy targets, target rod rabbit holders in the target positions, and capsule bodies. In the IFE and OFE, it is the largest atomic contributor in the U3O8-Al fuel and constitutes most of the filler material, which is the nonfuelled region located within the aluminum cladding [44]. The unfueled regions of the fuel plates and side walls of the IFE/OFE are also predominately composed of aluminum. It exists in all regions of the control elements, although absorption is dominated by neutron poisons. Some of the reflector support and HB tube cells are also of relevance.

The reaction of interest for aluminum is 27Al(n,γ)28Al with a β− transition to 28Si [62]. The transition releases 4.642 MeV and results in an excited state of 28Si at 1.779 MeV; therefore the β− endpoint energy is 2.864 MeV. The half-life of 28Al is 2.245 minutes; therefore, it is assumed the 28Al activity reaches equilibrium quickly into the cycle.

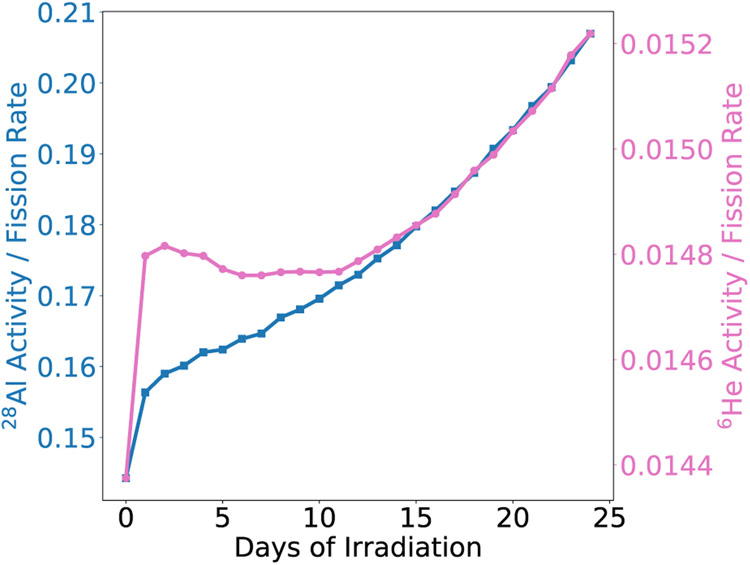

In the explicit representative HFIR MCNP model, aluminum is contained in 1,967 cells and the mass is approximately 250 kg. The 27Al(n,γ) core activity is calculated according to Equation 8 and ranges from 4.0 to 5.4 × 1017 s−1 from BOC to EOC. These values equate to approximately 15–20% of the fuel fission rate, as shown in Figure 3. The increase throughout the cycle is mostly due to the flux increase in many regions of the core and withdrawal of the CEs; the shape mirrors the CE withdrawal curves in Ref. [35]. The regions that contribute the most to the 28Al activity include the IFE/OFE sidewalls, structures in the FTT, reflector container, and the white (minimally absorbing) regions of the control elements [63].

FIG. 3:

28Al (blue square) and 6He (pink circle) activities to fuel fission rate ratio for each day in the cycle

A COUPLE-ORIGEN model of each of the aluminum cells is created to compare to MCNP and to evaluate the depletion of aluminum throughout a cycle. The 44-group neutron flux from MCNP for each cell for each day in the cycle is input into COUPLE-ORIGEN to generate time-dependent activities. There were some differences between the MCNP and COUPLE-ORIGEN models, but the cycle average difference was 2% between the two models. The choice of neutron energy-group structure had little impact on the 28Al activities because nearly all captures occur in the thermal range. Most cells deplete less than 0.01% from BOC to EOC. The main exception is fuel structural materials, which deplete in aluminum by more than 1% per cycle, yet the fuel assemblies are replaced every cycle.

2. Chromium, Copper, and Manganese

Chromium, copper, and manganese are also structural material candidates. Most of these include the steel of the target rod rabbit holder–bearing capsules, the stainless steel ends, and trace amounts in Al-6061 materials in HB tubes and IFE/OFE sidewalls. For these particular elements, only the EOC reaction rates are calculated in MCNP. Because flux in most core regions is higher at EOC than BOC and because most nonfuel materials are not depleted significantly from BOC to EOC, these calculations are considered to be a conservative overestimate of their average emissions.

Chromium-55 is produced from the (n,γ) reaction on 54Cr, which has the lowest abundance and cross section of the four naturally occurring isotopes. The half-life of 55Cr is 3.497 minutes. The β− transition releases 2.603 MeV. Although 55Cr decays to several excited states of 55Mn, the most probable (> 99.5%) is the ground state [64]. The β− endpoint energy is thus assumed to be 2.603 MeV. Chromium is contained in 221 cells of the model, totalling 16 g. The EOC 55Cr activity is found to be 1.6 × 1013 s−1, which is lower than the fission rate by a factor of 105 and therefore rules out 55Cr as a candidate.

Copper-66 is produced from the (n,γ) reaction on 65Cu, which has the lower abundance and cross section of the two naturally occurring isotopes. The half-life of 66Cu is 5.120 minutes. The β− transition releases 2.640 MeV. The only transition to the ground state of 66Zn that has a β− endpoint energy above the IBD threshold occurs approximately 90.77% of the time [65]. Copper is contained in 869 cells of the model, totalling 161 g. The EOC 66Cu activity is 1.13 × 1015 s−1. This is approximately 0.04% of the fission rate. This results in an excess of no more than 0.02% in 10 keV bins; this value is small enough to rule out 66Cu as a candidate.

Manganese-56 is produced from the (n,γ) reaction on 55Mn, which is the sole naturally occurring isotope. The half-life of 56Mn is 2.578 hours. The β− transition releases 3.695 MeV. The main transition of interest from 56Mn to 56Fe is to the 0.846 MeV excited state, which occurs 56.6% of the time [66]. The β− endpoint energy for this transition is therefore 2.849 MeV. Manganese is present in 226 cells of the model, totalling 109 g. The EOC 56Mn activity is 5.16 × 1015 s−1. Because the endpoint energy is low compared to other candidates and the reaction rate ratio is comparable to that of 66Cu, 56Mn is also ruled out as a candidate.

B. Beryllium Reflector

The beryllium reflector region is the outermost radial region of the core. A fresh RB, SPB, or PB contains almost exclusively beryllium (>99% atomically). The beryllium builds up reaction products, including neutron poisons 3He and 6Li, throughout the many irradiation cycles. The transmutation chain also involves the production of the antineutrino candidates 6He and 8Li. Owing to the multicycle nature of the poison buildup and the beryllium replacement scheme, MCNP and ORIGEN are both used to generate cycle-dependent isotopics and decay rates from a fresh reflector.

Helium-6 is produced directly from the (n,α) reaction on beryllium-9 with a neutron threshold of 0.67 MeV. It is the precursor reaction to the production of both neutron poisons. The half-life of 6He is 0.806 seconds. The released and β− endpoint energy are both 3.507 MeV because all 6He decays to the ground state of 6Li [67]. The 9Be(n,α) rate during the cycle in the entire reflector ranges from 3.80 to 4.05 × 1015 s−1, which is shown in Figure 3. The 6He increase is sharper than that for 28Al because of the higher dependence of neutron flux on the CE position, and this behavior follows the CE withdrawal curves [35]. The increase is largely caused by the CE withdrawal because there is a harder neutron spectrum at the axial ends of the reflector which increases the (n,α) reaction rate. Helium-6 activity decreases by no more than 1% between cycles due to the buildup and neutron absorption on 6Li; therefore, it is relatively independent of cycle and age of reflector regions.

Unlike the cycle-independent activity of 6He, the lithium isotopes rely heavily on the number of cycles irradiated. The 6Li increases in concentration until it reaches equilibrium after five cycles. Because of the overwhelming (n,α) cross section of 6Li, the higher isotopes 7Li and 8Li increase slowly and linearly with irradiation time from the lower-probability neutron capture. The 8Li activity linearly increases to approximately 1012 Bq after 50 cycles which is six orders of magnitude less than the fission rate. The RB, which is the most frequently replaced and has the largest proportion of 6He activity, is replaced around this cycle limit.

In summary, 6He does produce significant activity relative to the fission rate. Although the 8Li has a large β− endpoint energy, it pales in comparison to the fission reaction rate by a factor of 106. Thus, the 8Li is not considered as a candidate. Further studies can be performed to quantify intentional production of 8Li from lithium-filled target regions for high-energy spectrum [56].

C. Target Materials

The three main target material candidates are vanadium and the two actinide-containing targets recently irradiated in HFIR, CmO and NpO2. Vanadium is a common material irradiated in the flux trap. The two actinide targets are used for isotope production. Table II shows the loadings of the two types of actinide targets for the four most recent HFIR cycles. The actinide targets are usually irradiated for multiple cycles to produce the isotopes desired.

TABLE II:

Loading of materials in cycles of HFIR for CmO and NpO2 (number of target positions filled) with previous number of cycles irradiated in parentheses and vanadium (total grams in FTT).

| Cycle | Dates (MM/DD/2018) | CmO (#) | NpO2 (#) | V (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 479 | 05/01 to 05/25 | 4 (0) | 9 (0) | 274 |

| 480 | 06/17 to 07/06 | 4 (1) | 9 (1) | 260 |

| 481 | 07/24 to 08/17 | 4 (2) | 0 | 228 |

| 482 | 09/04 to 09/28 | 4 (3) | 9 (2) | 248 |

1. Vanadium

Vanadium is a target material that is primarily irradiated in the FTT region. The representative model [35] contains many vanadium-bearing targets. Many of these targets are not solely composed of vanadium as a target material; the representative model contains many generic homogeneous targets to obtain representative loading of elements. The FTT region also has some vanadium capsules in the PTPs and target rod rabbit holders that make up part of its composition. Since PROSPECT has begun taking data, the loading of vanadium in the FTT region has not changed drastically.

Vanadium-52 is produced from the (n,γ) reaction on 51V, which is the main naturally occurring isotope. The only other naturally occurring isotope is 50V, which constitutes 0.25% of vanadium in nature and is not a candidate. The cross section for neutron capture on 50V is approximately an order of magnitude higher than that of 51V. Capture tallies in vanadium materials showed that the ratio of captures in 50V to 51V roughly follows this product of abundance and cross section, i.e., 50V(n,γ)/51V(n,γ) is approximately 2.5%. Therefore, assuming natural abundance, most of the neutron captures still occur in 51V despite the higher cross section of 50V.

The half-life of 52V is 3.743 minutes. The β− transition releases 3.974 MeV. The main transition is to a 1.434 MeV excited state of 52Cr, the only transition that has a β− endpoint energy above the IBD threshold, occurs approximately 99.2% of the time [68]. The endpoint energy is 2.540 MeV.

To calculate approximate rates from 52V, several simulated loadings of vanadium-bearing generic targets are modeled in several positions in the flux trap; these targets contain vanadium in a similar concentration to that in the V+Ni targets in the representative model [35]. Several cases are created at BOC and EOC with full-axial vanadium targets loaded into up to 10 FTT positions. Table II shows the approximate loading in grams of vanadium (total) in the FTT region for the past four cycles, which has typically been in the range of 200–300 g. The loading in the simulation cases created here have vanadium masses between 150 and 370 g, which covers the entire spread of vanadium loading over the previous five cycles.

The capture rates of 51V (and 50V) are calculated on a per-gram basis for the various cases at both BOC and EOC. Linear regression is performed for the capture rate of 51V as a function of mass in the FTT region for both BOC and EOC with a correlation coefficient > 0.99. The number of grams from the four cycles can be used to calculate approximate 52V activities at BOC and EOC from the linear regression. The rates range from 1.58 to 1.82 × 1016 s−1 for the minimum loading and from 1.70 to 1.95 × 1016 s−1 for the maximum loading of the previous four cycles.

2. Curium

Targets made of CmO have been irradiated in the FTT region to produce 252Cf in many recent cycles. The CmO targets take up the full length of the active fuel region. Although the primary actinide composition in the targets is Cm, they also contain smaller concentrations of Pu and Am [35].

Calculations of CmO fission and heat generation rates have been performed at HFIR for safety analysis. The cycle-dependent fission rates of the CmO targets are obtained and analyzed. The fission rates in the targets are dominated by the fission of 245Cm and 247Cm, which account for more than two-thirds of the CmO fission rates. Plutonium-241 and californium-251 each contribute at the 5–12% level. The fission yield data are not available for 247Cm in ENDF or other databases.

The representative model contains five CmO targets, all near the center of the flux trap [35]. The average fission rates among the five targets is between 5.11 × 1014 (BOC) and 3.55 × 1014 (EOC) s−1. This is roughly 0.01–0.02% of the total core fission rate. Even with five such targets in the flux trap, which is considered typical for a production campaign, the fraction relative to the 235U fission rate would be approximately 0.1%. The isotopes that contribute most to this fission rate are 245Cm and 247Cm. It is assumed that the change to the 235U spectrum would be relatively unaffected by curium fissions. The fission yield differences for the rest of the known isotopes is not significant enough to consider the curium target isotopes as candidates. Note, these targets were analyzed for one cycle but are typically irradiated for many. The total target fission rates decrease with each subsequent cycle so this is deemed to be a conservative estimate of multicycle CmO target irradiations.

3. Neptunium

Neptunium oxide (NpO2) targets have been irradiated in several past cycles to produce 238Pu for NASA. The targets are irradiated in the VXFs for nominally three cycles. The fission rates in the NpO2 targets are dominated by two isotopes: 239Pu and 238Np. The 238Np dominates for the first two cycles, and 239Pu becomes the dominant contributor at the beginning of the third cycle.

The PROSPECT experiment collected data during three NpO2 irradiation cycles. Nine VXFs were filled with NpO2 targets starting in Cycle 479 and continued into Cycle 480. Cycle 481 contained zero targets with Np and Pu. Cycle 482 continued with the targets’ third and final irradiation cycle to date, which is shown in Table II.

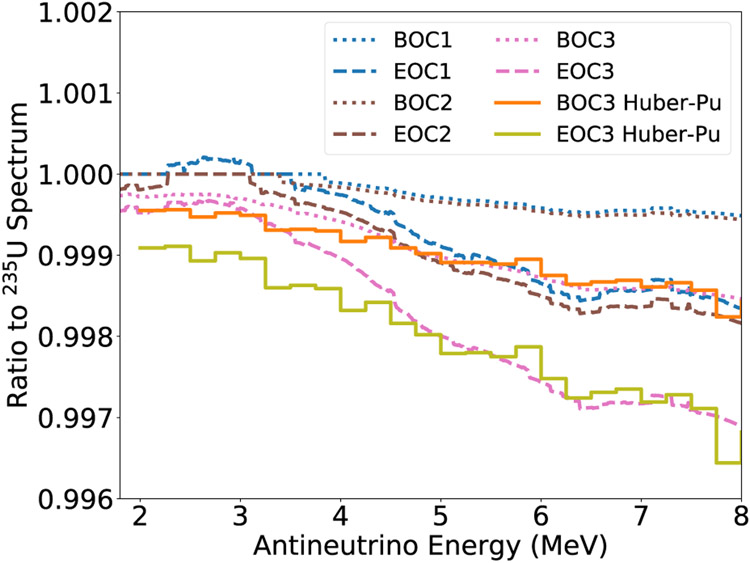

The Np and Pu fission rates are converted to spectra using the ENSDF and fission yield data and compared with the 235U nominal spectrum of HFIR. The 238Np spectrum was calculated using Oklo, and its resulting spectrum is comparable to that of 235U but higher by 4–8% in the 2–6 MeV energy range. The reaction rate ratio of target to fuel fission rate is converted to relative production rate in a way that is similar to that used in Equation 10. Heat power in the reactor is maintained at 85 MW by decreasing the fission rate of 235U to offset the target (Np and Pu) fission rate; this is assumed to be valid because the fission energy release is comparable for the actinides. Note, the core power at HFIR has uncertainties of 2% due to instrument uncertainty [56]. Figure 4 shows the relative change to the nominal 235U spectrum for the three cycles of irradiation at BOC/EOC.

FIG. 4:

spectrum changes from 235U based on Oklo for beginning and end of a typical three-cycle irradiation of the NpO2 targets using the summation method. BOC3 and EOC3 Huber-Pu (orange solid and yellow solid, respectively) include differences in the third irradiation cycle between the inclusion of 239Pu only (no 238Np) using Huber predictions.

To only examine the impact of widely used 239Pu spectra, only the 239Pu fission rates in the targets are compared to that for 235U in the fuel using the Huber–Mueller data. The ratio of 239Pu fissions is highest in the their third cycle of irradiation, so this case is considered for the maximum difference from the nominal 235U spectrum. With the inclusion of the nine NpO2 VXFs, each containing seven targets in their third cycle of irradiation, when the 239Pu contribution is the highest, the spectrum decreases by no more than 0.35% in any energy bin according to the Huber data. This difference is shown in Figure 4. The decrease in the spectrum below the bump region is largely a result of the fission rate and lower yield of 239Pu.

D. Cycle Average Nonfuel Contribution to Spectrum

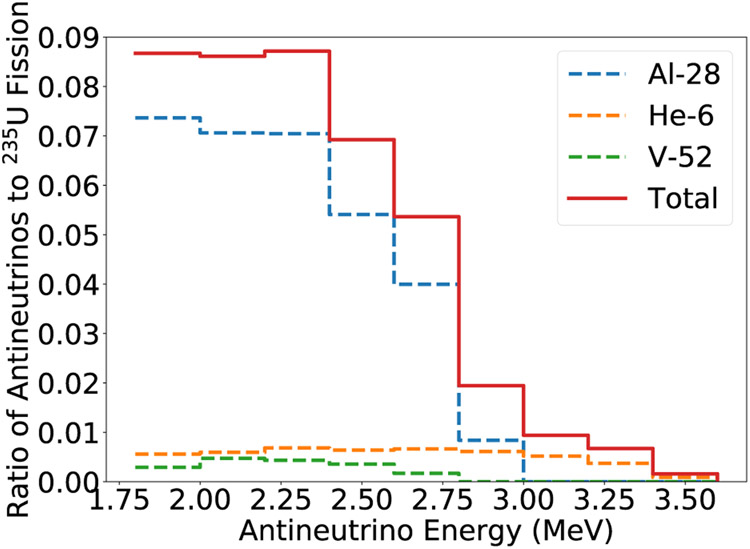

The results presented so far show that 28Al, 6He, and 52V are the most significant candidates of nonfissile in HFIR. The ratio of spectrum, according to Equation 10, is used to calculate cycle-average excess from the selected candidates. For aluminum and helium, the cycle-average reaction rate is used. For vanadium, an activity corresponding to an average loading in the flux trap is used.

Figure 5 shows the excess contributions in 200 keV bins for the three largest contributions. Aluminum-28 contributes over 8% in the low-energy range and all three isotopes combine to more than 9%. The 28Al had by far the largest contribution between 1.8 and 2.86 MeV, its β− endpoint. The 6He has a peak contribution of 0.5–0.75% effect around 2.5 MeV but drops toward its endpoint 3.5 MeV. The 52V contribution peaks at about 0.5%, and its endpoint is comparable to 28Al. In total, these three isotopes increase the expected magnitude of detected reactor spectra by 1%.

FIG. 5:

Average excess of 28Al (blue dashed), 6He (orange dashed), and 52V (green dashed) contributions to the spectrum. The sum of these contributions is also shown (red solid)

VI. NOTE ON COMMERCIAL REACTOR COMPARISONS

Most reactor measurements have been collected at commercial nuclear power plants, mainly light water reactors (LWRs). The natural question arises of how nonfuel may affect the spectrum for a commercial LWR compared to HFIR. A full analysis was not performed, but some insight can be provided based on this analysis. The larger core size and lack of significant experimental facilities at commercial reactors results in less neutron activation of nonfuel materials on a perfission basis. Commercial LWRs also have a small variety of materials that are contained in the core. The primary nonfuel materials that exist in commercial LWRs include Zircaloy as a cladding material and variations of stainless steels in support structures such as the reactor pressure vessel.

Almost all of the main LWR isotopes of iron and zirconium would be ruled out by the candidate selection process (Section II); the only exception is 96Zr, the isotope of zirconium with the lowest natural abundance. The 96Zr(n,γ)97Zr transition has only one, albeit dominant, transition that results in a β− endpoint (1.915 MeV) slightly higher than the IBD threshold [69]. This transition has a half-life of 16.749 hours, which is not negligible but longer that that of most isotopes considered in this work.

Chromium has one neutron capture reaction that results in a above the IBD threshold, 55Cr. Its precursor, 54Cr, is the isotope with the lowest abundance and cross section of chromium isotopes, shown in Table I. Chromium can be contained in 300 series stainless steels, most commonly 304, 308, and 309 in the core structural and pressure vessel [70]. These forms of steel can have between 15% and 20% chromium by mass [71]. Case studies for individual reactors and their chromium content can be performed should precise predictions be needed.

In summary, contributions from the minor isotopes of zirconium and chromium in LWRs are estimated to be at least three orders of magnitude lower than that of aluminum in HFIR. Further studies can be done to examine the activation of zirconium or other isotopes (e.g., the chromium composition in steels for specific commercial reactors). This effect is estimated to be small due to the lower ratio of absorption rate to fission rate and the lack of large quantities of chromium in the higher flux regions of the core (i.e., near the center). The non-fuel contributions to the spectrum should not be a cause for concern for experiments at commercial reactors, such as Daya Bay, Double Chooz, and RENO.

VII. CONCLUSIONS

HFIR’s missions allow for a wide variety of different materials to be deliberately or indirectly transmuted to β− decaying products during operation. Potential candidates are examined to find the largest emitters of that need to be accounted for in the 235U spectrum from HFIR.

A methodology was created to select candidates from nonfuel materials in HFIR that would contribute nominally to the spectrum. Several candidates are identified as potentially problematic for the measurement based on their abundance in the core, cross section, and β− endpoint energy. Reactor simulations were performed to calculate reaction rates and spectra from the nonfuel materials.

The most dominant nonfuel contributors to the spectrum are the 28Al from structural materials and 6 He from interactions in the beryllium reflector. Both of these contributions were found to be relatively cycle independent and to increase with cycle time because of the flux increase in many regions of the reactor. The contribution to the energy spectrum was calculated. Averaged over a cycle, the 28Al dominates with a maximum 7% contribution near threshold to about 1% at its β− endpoint. The 6He has a nearly uniform 0.5–0.75% contribution up until its endpoint. Based on typical loadings in the flux trap, the 52V has a 0.25–0.5% contribution. For all energy ranges, these contributions combine for 1% effect in the total detected . Such contributions should be calculated for reactors with comparable amounts of aluminum or similar reflector design to support future neutrino experiments.

The contributions of target materials have a high dependence on the amount and location of loading in the core. Vanadium is identified as the target material that was calculated to have as high as a 0.26–0.51% in the low-energy range. The irradiation of NpO2 targets has a small but non-negligible impact on the spectrum. The effect of the recent loading of nine VXF positions with multicycle irradiations of NpO2 yield a maximum of 0.35% relative change to the nominal 235U spectrum at high energy. Should HFIR irradiate more targets or irradiate them more than three cycles, it would be necessary to analyze further the contribution of 238Np and 239Pu because the 235U fuel fission rate will decrease as a result of heat power conservation. The multicycle NpO2 targets contribution to the spectrum would be exacerbated with subsequent cycles irradiated because of the increase in 239Pu fission rate and its low yield compared to 235U. The CmO targets generally would not contribute significantly unless large discrepancies between Cm or Cf and 235U spectra were discovered.

In summary, this analysis shows that nonfuel reactions make significant contributions to the spectrum at HFIR. In particular, 28Al, 6He, and 52V contributions should be included in the analysis for a PROSPECT-like experiment at HFIR. We suggest that reactor modeling for research reactors may be necessary in the development and analysis of short-baseline antineutrino experiments to account for variations in research reactor design. Although we only examined HFIR in detail, other nonfuel emission candidates may need to be considered depending on reactor composition and missions.

The findings for these isotopes in HFIR are factored into the PROSPECT detector response matrix. Integrated over the whole spectrum, the contributions of 28Al and 6He combined are found to have 1% effect on the total flux [72]. For HFIR specifically, nonfuel contributions are not in the energy range high enough to contribute to the bump in the measured spectra.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

David Chandler at HFIR was instrumental in helping with reactor modeling efforts. Dan Dwyer is acknowledged for his help using the Oklo code. Additionally, discussions with Greg Hirtz at HFIR were useful in identifying candidates. The fission rates in the CmO targets were provided by Susan Hogle from ORNL.

This material is based upon work supported by the following sources: US Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science, Office of High Energy Physics under Award No. DE-SC0016357 and DE-SC0017660 to Yale University, under Award No. DE-SC0017815 to Drexel University, under Award No. DE-SC0008347 to Illinois Institute of Technology, under Award No. DE-SC0016060 to Temple University, under Contract No. DE-SC0012704 to Brookhaven National Laboratory, and under Work Proposal Number SCW1504 to Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. This work was performed under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract DE-AC52-07NA27344 and by Oak Ridge National Laboratory under Contract DE-AC05-00OR22725. Additional funding for the experiment was provided by the Heising-Simons Foundation under Award No. #2016-117 to Yale University.

J.G. is supported through the NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Program and A.C. performed work under appointment to the Nuclear Nonproliferation International Safeguards Fellowship Program sponsored by the National Nuclear Security Administration’s Office of International Nuclear Safeguards (NA-241). This work was also supported by the Canada First Research Excellence Fund (CFREF), and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery program under grant #RGPIN-418579, and Province of Ontario.

We further acknowledge support from Yale University, the Illinois Institute of Technology, Temple University, Brookhaven National Laboratory, the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory LDRD program, the National Institute of Standards and Technology, and Oak Ridge National Laboratory. We gratefully acknowledge the support and hospitality of the High Flux Isotope Reactor and Oak Ridge National Laboratory, managed by UT-Battelle for the U.S. Department of Energy.

VIII. ACRONYMS

- BOC

beginning of cycle

- CE

control element

- ENDF

Evaluated Nuclear Data File

- ENSDF

Evaluated Nuclear Structure Data File

- EOC

end of cycle

- FTT

flux trap target region

- HFIR

High Flux Isotope Reactor

- IBD

inverse beta decay

- IFE/OFE

inner/outer fuel element

- ILL

Institut Laue-Langevin

- MCNP

Monte Carlo N-Particle

- ORNL

Oak Ridge National Laboratory

- ORIGEN

Oak Ridge Isotope Generation

- PB

permanent beryllium

- PNF

power normalization factor

- PROSPECT

Precision Reactor Oscillation and Spectrum

- RB

removable beryllium

- SPB

semi-permanent beryllium

- VXF

vertical experiment facility

References

- [1].Heeger KM, Littlejohn BR, Mumm HP, and Tobin MN, Phys. Rev. D 87, 073008 (2013), arXiv:1212.2182 [hep-ex]. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kim Y, Nucl. Eng. Technol 48, 285 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- [3].An F et al. (Daya Bay Collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett 118, 251801 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Klimov YV, Kopeikin VI, Mikaélyan LA, Ozerov KV, and Sinev VV, At. Energy 76, 123 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- [5].An F et al. , Phys. Rev. Lett 115 (2015), 10.1103/PhysRevLett.115.111802, arXiv:1505.03456. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Choi J et al. , Phys. Rev. Lett 116 (2016), 10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.211801, arXiv:1511.05849. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Abe Y and others J High Energy Phys. 2014, 86 (2014), arXiv:1406.7763. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Mention G, Fechner M, Lasserre T, Mueller TA, Lhuillier D, Cribier M, and Letourneau A, Phys. Rev. D - Part. Fields, Gravit. Cosmol 83 (2011), 10.1103/PhysRevD.83.073006, arXiv:1101.2755. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Huber P, Phys. Rev. C 84, 024617 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- [10].Fallot M et al. , Phys. Rev. Lett 109, 202504 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hayes AC, Friar JL, Garvey GT, Jungman G, and Jonkmans G, Phys. Rev. Lett 112, 202501 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hayes AC, Friar JL, Garvey GT, Ibeling D, Jungman G, Kawano T, and Mills RW, Phys. Rev. D - Part. Fields, Gravit. Cosmol 92 (2015), 10.1103/PhysRevD.92.033015, arXiv:1506.00583. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Dwyer DA and Langford TJ, Phys. Rev. Lett 114, 012502 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Littlejohn BR, Conant A, Dwyer DA, Erickson A, Gustafson I, and Hermanek K, Phys. Rev. D 97, 073007 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- [15].Schreckenbach K, Colvin G, Gelletly W, and Von Feilitzsch F, Phys. Lett. B 160, 325 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kopeikin VI, Phys. of At. Nuclei 66, 472 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mueller TA, Lhuillier D, Fallot M, Letourneau A, Cormon S, Fechner M, Giot L, Lasserre T, Martino J, Mention G, Porta A, and Yermia F, Phys. Rev. C 83, 054615 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- [18].Huber P and Jaffke D, Phys. Rev. Lett 116, 122503 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Zhou B, Ruan X-C, Nie Y-B, Zhou Z-Y, An F-P, and Cao J, Chinese Physics C 36, 1 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- [20].Brdar V, Huber P, and Kopp J, Phys. Rev. Applied 8, 054050 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ashenfelter J et al. , J. Instrum 13, P06023 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- [22].Allemandou N et al. , J. Instrum 13, P07009 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- [23].Abreu Y et al. , J. Instrum 13, P05005 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- [24].Akimov D et al. , Science 357, 1123 (2017), https://science.sciencemag.org/content/357/6356/1123.full.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Angloher G et al. , Europ. Phys. Jour. C 79, 1018 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- [26].Bowden NS, Bernstein A, Dazeley S, Svoboda R, Misner A, and Palmer T, Jour. of Appl. Phys (2009), 10.1063/1.3080251, arXiv:0808.0698. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Chadwick M et al. , Nuclear Data Sheets 112, 2887 (2011), Special Issue on ENDF/B-VII.1 Library. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Tepel J, Comput. Phys. Commun 33, 129 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- [29].Deniz M et al. (TEXONO Collaboration), Phys. Rev. D 81, 072001 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- [30].Cheng L et al. , Physic and Safety Analysis for the NIST Research Reactor, Tech. Rep. (National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- [31].Diamond D, Baek J, Hanson A, Cheng L-Y, Brown N, and Cuadra A, Conversion Preliminary Safety Analysis Report for the NIST Research Reactor, Tech. Rep. (National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2014) BNL-107265-2015-IR. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Stevens J, Tentner A, and Bergeron A, Feasibility Analyses for HEU to LEU Fuel Cnversion of the LAUE Langivin Institute (ILL) High Flux Reactor (RHF), Tech. Rep. (Argonne National Laboratory, 2010) aNL/RERTR/TM-10-21. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Koonen E, Neutronic Modelling in Support of BR2 Irradiation Programmes, Tech. Rep. (Studiecentrum voor Kernenergie Centre d’tude de l’nergie Nuclaire (SCK CEN), 2004). [Google Scholar]

- [34].Cheverton R and Sims T, HFIR Core Nuclear Design, Tech. Rep. (Oak Ridge National Laboratory, 1971). [Google Scholar]

- [35].Chandler D, Betzler B, Hirtz G, Ilas G, and Sunny E, Modeling and Depletion Simulations for a High Flux Isotope Reactor Cycle with a Representative Experiment Loading, Tech. Rep. (Oak Ridge National Laboratory, 2016) ORNL/TM-2016/23. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Hogle S, Optimization of Transcurium Isotope Production in the High Flux Isotope Reactor, Ph.D. thesis, University of Tennessee, Knoxville: (2012). [Google Scholar]

- [37].Knight R, Binns J, and Adamson GJ, Fabrication Procedures for Manufacturing High Flux Isotope Reactor Fuel Elements, Tech. Rep. (Oak Ridge National Laboratory, 1968) oRNL-4242. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Chandler D and Ellis R, Proceedings of the Nuclear and Emerging Technologies for Space (NETS) Conference (2015). [Google Scholar]

- [39].Chandler D, PHYSOR Conference (2016). [Google Scholar]

- [40].Hurt C, Freels J, Hobbs R, Jain P, and Maldonado G, Thermal Safety Analysis for the Production of Plutonium-238 at the High Flux Isotope Reactor, Tech. Rep. (Oak Ridge National Laboratory, 2016) ORNL/TM-2016/234. [Google Scholar]

- [41].X-5 Monte Carlo Team, MCNP—A General Monte Carlo N-Particle Transport Code, Version 5, Tech. Rep. (Los Alamos National Laboratory, 2005) LA-UR-03-1987. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Werner C, MCNP User’s Manual—Code Version 6.2, Los Alamos National Laboratory; (2017). [Google Scholar]

- [43].Xoubi N, Primm T III, et al. , Modeling of the High Flux Isotope Reactor Cycle 400, Tech. Rep. (Oak Ridge National Laboratory, 2004) ORNL/TM-2004/251. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Ilas G, Chandler D, et al. , Modeling and Simulations for the High Flux Isotope Reactor Cycle 400, Tech. Rep. (Oak Ridge National Laboratory, 2015) oRNL/TM-2015/36. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Haeck W, VESTA User’s Manual—Version 2.1.0, Institut de Radioprotection et de Surete Nucleaire, France: (2012). [Google Scholar]

- [46].Snoj L and Ravnik M, Proceedings of the International Conference Nuclear Energy for New Europe 2006 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- [47].Sterbentz J, Q-value (MeV/fission) Determination for the Advanced Test Reactor, Tech. Rep. (Idaho National Laboratory, 2013) iNL/EXT-13-29256. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Kopeikin V, Phys. of At. Nuclei 75 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- [49].Ma XB, Zhong WL, Wang LZ, Chen YX, and Cao J, Phys. Rev. C 88, 014605 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- [50].Zerovnik G et al. , Ann. of Nucl. Energy 63, 126 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- [51].Rearden B, Jessee M, et al. , SCALE: A Comprehensive Modeling and Simulation Suite for Nuclear Safety Analysis and Design, Tech. Rep. (Oak Ridge National Laboratory, 2011) ORNL/TM-2005/39. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Peplow D, A Computational Model of the High Flux Isotope Reactor for the Calculation of Cold Source, Beam Tube, and Guide Hall Nuclear Parameters, Tech. Rep. (Oak Ridge National Laboratory, 2004) ORNL/TM-2004/237. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Dez C, Buss O, Hoefer A, Porsch D, and Cabellos O, Ann. of Nucl. Energy 77, 101 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- [54].Mosteller R, An Expanded Criticality Validation Suite for MCNP, Tech. Rep. (Los Alamos National Laboratory, 2010) LA-UR-10-06230. [Google Scholar]

- [55].Ilas G, Gauld I, Difilippo F, and Emmett M, Analysis of Experimental Data for High Burnup PWR Spent Fuel Isotopic Validation: Calvert Cliffs, Takahama, and Three Mile Island Reactors, Tech. Rep. (Oak Ridge National Laboratory, 2010) ORNL/TM-2008/071. [Google Scholar]

- [56].Conant A, Antineutrino Spectrum Characterization of the High Flux Isotope Reactor Using Neutronic Simulations, Ph.D. thesis, Georgia Institute of Technology; (2019). [Google Scholar]

- [57].Radaideh M, Price D, and Kozlowski T, Proceedings of The Fourth International Conference on Physics and Technology of Reactors and Applications (PHYTRA4) (2018). [Google Scholar]

- [58].Dwyer D, “OKLO: A toolkit for Modeling Nuclides and Nuclear Reactions,” https://github.com/dadwyer/oklo. [Google Scholar]

- [59].Wilkinson D, Nucl. Instrum. and Methods in Phys. Res. Sect. A 275, 378 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- [60].Schenter GK and Vogel P, Nucl. Sci. and Eng 83, 393 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- [61].Huber P, Nucl. Phys. B 908, 268 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- [62].Schmidt H et al. , Phys. Rev. C 25 (1982), 10.1103/PhysRevC.25.2888. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Conant A, Mumm H, and Erickson A, PHYSOR Conference (2018). [Google Scholar]

- [64].Junde H, Nuclear Data Sheets 109, 787 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- [65].Browne E and Tuli J, Nuclear Data Sheets 111, 1093 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- [66].Junde H, Su H, and Dong Y, Nuclear Data Sheets 112, 1513 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- [67].Tilley D, Cheves C, Godwin J, Hale G, Hofmann H, Kelley J, Sheu C, and Weller H, Nucl. Phys. A 708, 3 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- [68].Dong Y and Junde H, Nuclear Data Sheets 128, 185 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- [69].Nica N, Nuclear Data Sheets 111, 525 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- [70].Zinkle SJ and Busby JT, Mater. Today 12, 12 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- [71].McConn R Jr. et al. , Compendium of Material Composition Data for Radiation Transport Modeling, Tech. Rep. (Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, 2011) pIET-43741-TM-963. [Google Scholar]

- [72].Ashenfelter J et al. (PROSPECT Collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett 122, 251801 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]