Abstract

Little is known about regulated glucagon secretion by human islet α cells compared to insulin secretion from β cells, despite conclusive evidence of dysfunction in both cell types in diabetes mellitus. Distinct insulins in humans and mice permit in vivo studies of human β cell regulation after human islet transplantation in immunocompromised mice, whereas identical glucagon sequences prevent analogous in vivo measures of glucagon output from human α cells. Here we use CRISPR/Cas9 editing to remove glucagon codons 2–29 in immunocompromised NSG mice, preserving production of other proglucagon-derived hormones. Glucagon knockout-NSG (GKO-NSG) mice have metabolic, liver and pancreatic phenotypes associated with glucagon signaling deficits that revert after transplantation of human islets from non-diabetic donors. Glucagon hypersecretion by transplanted islets from donors with type 2 diabetes revealed islet-intrinsic defects. We suggest that GKO-NSG mice provide an unprecedented resource to investigate human α cell regulation in vivo.

Keywords: diabetes mellitus, insulin, hormone, liver, pancreas, Slc38a5, GLP-1, incretin, proglucagon, genetics, disease

Pancreatic islet α and β cells play an important role in maintaining euglycemia by secreting peptide hormones in response to glucose and other blood metabolites. In healthy β cells, an increase in blood glucose triggers insulin secretion, which promotes glucose uptake and glycogenesis or adipogenesis in ‘insulin-target’ organs. In contrast, α cell glucagon secretion, stimulated by hypoglycemia, amino acids, adrenal and neuronal inputs, leads to glucose mobilization by promoting glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis in ‘glucagon-target’ organs, like liver1. Impaired regulation or output of insulin and glucagon by human β cells and α cells underlies development and progression of diabetes mellitus. Thus, intensive efforts are focused on determining the physiological and pathological mechanisms governing human islet α cell and β cell function.

Recent studies reveal that human and mouse islet cells have differences in cellular composition, molecular regulation, physiological control, intra-islet cell interactions and other crucial properties2–5, motivating increased research focus and resource generation in human islet biology. Transplantation of human islets in immunocompromised mice, like the NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1WjlSz mice (NSG) strain6,7, has emerged as an important strategy for assessing human islet β cell function in vivo8–10. Unlike distinct human and mouse insulins, the mature glucagon sequence in these species is identical, precluding accurate quantification of circulating human islet-derived glucagon secretion in mice and limiting studies of human α cells in transplantation-based models. Thus, development of immunocompromised mouse strains that permit detection of human glucagon in mice and in vivo studies of transplanted human islet α cell function could be transformative by enabling mechanistic analysis in physiological and pathophysiological conditions.

Genetic targeting to eliminate endogenous glucagon production in mice could permit in vivo quantification of glucagon output by transplanted human islets. The Gcg gene encodes proglucagon, a prohormone expressed and differentially processed in islet α cells, gut enteroendocrine cells, and the central nervous system to produce multiple distinct peptide hormone products, including glucagon, oxyntomodulin, glicentin, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucagon-like peptide 2 (GLP-2)11. Differential proglucagon processing depends on co-expression of the prohormone convertase (PC) enzymes. In pancreatic islet α cells, PC2 enables cleavage of proglucagon into the 29 amino acid mature glucagon protein, which is entirely encoded12 by Gcg exon 3. PC1/3 expression in enteroendocrine cells permits cleavage of proglucagon into other products, including GLP-1, a secreted incretin hormone that enhances postprandial insulin output by islet β cells13–17.

Glucagon production in mice has been eliminated by targeted mutation of the Gcg gene to generate the Gcggfp allele; adult homozygous Gcggfp/gfp mice were normoglycemic and exhibited α cell hyperplasia and hypoinsulinemia18. Earlier studies in mice of glucagon signaling loss from glucagon receptor (Gcgr) deletion, Gcgr antibody inactivation19–22, or elimination of PC223, 24 reported extensive metabolic phenotypes reflecting impaired gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis, including elevated circulating amino acid levels and basal hypoglycemia. Despite this progress, none of the mice from these prior studies afforded the possibility of investigating glucagon regulation by transplanted human islet α cells. Here we generated immunocompromised mice lacking mature glucagon coding sequences (GKO-NSG) that enable investigations of glucagon regulation in transplanted human islets. We demonstrate the utility of GKO-NSG mice for analyzing in vivo α cell function in human islets from non-diabetic and diabetic donors.

Results

Generation of GKO-NSG mice

To develop mice that permit transplantation of human islets and detection of human glucagon, we used CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in NSG-derived oocytes to create an in-frame deletion of nucleotides from Gcg exon 3, which encode mature glucagon (Figure 1a and Extended Data 1a). This strategy should preserve production of metabolic regulators derived from the proglucagon carboxy-terminus, including GLP-1. After generating candidate founder mice, genotype screening identified one NSG founder harboring an in-frame 93 base pair (bp) deletion of the 3’ end of Gcg exon 3. This in-frame deletion includes the elimination of 84 nucleotides encoding amino acids 2–29 of mature glucagon (Figures 1a-b and Extended Data 1a). Subsequent breeding of heterozygous F1 mice produced viable, fertile homozygous GKO-NSG mice that were born at a rate of 22.1% (compared to 32.8% wild type, and 45.1% heterozygous; n= 122 mice). Three-week-old male and female GKO-NSG mice weighed significantly less than NSG control littermates (Extended Data 1c). However, by eight weeks of age, no difference in body weight was detected in adult NSG and GKO-NSG mice (Extended Data 1c). This transient reduction of body mass in GKO-NSG mice likely reflects a combination of reduced circulating insulin levels in GKO-NSG mice (see below), and possibly unrecognized roles for glucagon in development25–28. Thus, beginning at eight weeks of age, GKO-NSG mice of both sexes were characterized for phenotypes associated with glucagon signaling loss.

Figure 1. Generation of GKO-NSG mice.

(a) Schematic showing Glucagon (Gcg) gene structure, guide RNA (gRNA) targeting sites (green arrows), and genotyping primers (blue arrows). Exon 3 is highlighted in red with the portion encoding mature glucagon marked by hatch lines. (b) Representative genotyping PCR of GKO-NSG mice following a heterozygous GKO-NSG cross; similar results were seen from 30 crosses of heterozygous GKO-NSG mice. DNA ladder on right side of genotyping gel image is marked at the size indicators for 850 and 650 base pairs (bp). (c) Plasma glucagon levels in 2–3 month old GKO-NSG and NSG mice during ad libitum feeding or after a 3-hour fast. Due to distribution of data from GKO-NSG mice, these data were not analyzed with statistical tests. (NSG mice, n= 6 males and 4 females; GKO-NSG mice, n= 4 males and 8 females). (d) Plasma active GLP-1 levels from 2.5–3 month old GKO-NSG and NSG controls following oral glucose challenge (30’: P= 0.027573 by Repeated Measures ANOVA, with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test) (NSG mice, n= 5 males and 3 females; GKO-NSG mice, n= 8 males and 2 females). Dashed lines indicate limit of detection. Data are represented as mean of biological replicates with individual data points overlaid and error bars indicate ± SEM. * P ≤ 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01, *** P ≤ 0.001. N.D.= not detected. See also Extended Data 1.

To verify elimination of mature glucagon production in GKO-NSG mice, plasma glucagon levels were measured from ad libitum fed and fasted GKO-NSG and NSG control mice. Unlike control NSG mice, plasma glucagon was undetectable in GKO-NSG mice in both fed and fasted states (Figure 1c). Consistent with this, immunostaining with antibodies that detect mature glucagon (GCG 1–29) did not label islet α cells in GKO-NSG pancreata, whereas these α cells were readily identified with an antibody that detects proglucagon (Extended Data 1b). By contrast, plasma total and active GLP-1 levels following an oral glucose tolerance test were higher in GKO-NSG mice compared to NSG control littermates (Figure 1d and Extended Data 1f). Similar to previous studies using glucagon-signaling deficient mice19, 29, extracts of isolated islets from GKO-NSG mice had increased active GLP-1 levels that may account for increased circulating GLP-1 (Extended Data 1g). This increase in circulating GLP-1 was accompanied by lower glycemic levels in both fasting and feeding (Extended Data 1d), as well as improved glucose tolerance (Extended Data 1e) in GKO-NSG mice. Thus, our CRISPR-based strategy successfully eliminated glucagon while sparing GLP-1 production in GKO-NSG mice.

Transplanted human islets retain regulated glucagon secretion in GKO-NSG mice

To assess the possibility of measuring circulating glucagon from human islets in GKO-NSG mice, we transplanted human islets from previously-healthy donors under the renal capsule of GKO-NSG mice (GKO-NSG Tx mice; Figure 2a). Plasma glucagon was detectable in GKO-NSG Tx mice two weeks after transplantation and thereafter for at least fourteen weeks, at which point GKO-NSG Tx mice were sacrificed for tissue analysis. Four weeks after human islet transplantation, plasma glucagon levels in fasted GKO-NSG Tx and control NSG mice were remarkably similar, but circulating glucagon remained undetectable in sham-transplanted GKO-NSG mice (Figure 2b).

Figure 2. Transplanted human islets retain regulated glucagon secretion in GKO-NSG mice.

Human islets were transplanted under the renal capsule of GKO-NSG mice. Mice were then examined for presence of glucagon in the circulation and regulation of glucagon secretion from transplanted islets. Data are from NSG control, GKO-NSG, and GKO-NSG mice post-transplantation (GKO-NSG Tx). (a) Schematic of islet transplantation and phenotyping schedule. (b) Plasma glucagon levels from 4–6 month old mice after a 6-hour fast. Due to the distribution of data from GKO-NSG mice, these data points were omitted from one-way ANOVA, with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. (NSG mice, n= 10 males and 3 females; GKO-NSG mice, n= 11 males and 2 females; GKO-NSG Tx mice, n= 6 males). (c) 4.5–6.5 month old mice were challenged with human insulin; glucagon response to acute hypoglycemia was measured from plasma at 0 and 30-minutes post-insulin injection (0’ vs 30’: NSG: P= 0.033030; GKO-NSG Tx: P= 0.002262 by paired two-tailed Student’s t-test, with Bonferroni correction). Due to the distribution of data from GKO-NSG mice, these data points were omitted from statistical analysis. (NSG mice, n= 5 males; GKO-NSG mice, n= 2 males and 1 female; GKO-NSG Tx mice, n= 5 males). Dashed lines indicate limit of detection. Data are represented as mean of biological replicates with individual data points overlaid and error bars indicate ± SEM. N.D.= not detected. N.S.= not significant. * P ≤ 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01, *** P ≤ 0.001. See also Extended Data 2.

To assess dynamic regulation of glucagon secretion from human α cells in GKO-NSG Tx mice, we measured glucagon secretion in vivo after an intraperitoneal insulin challenge, which elicits transient hypoglycemia. Reduced blood glucose levels stimulate α cell glucagon secretion1, 30, and, as expected, acute hypoglycemia was accompanied by increased circulating glucagon levels in NSG controls (Figures 2c and Extended Data 2). By contrast, insulin challenge and hypoglycemia elicited no glucagon output in sham-transplanted GKO-NSG mice (Figure 2c and Extended Data 2). Like in NSG controls, circulating human islet-derived glucagon levels increased upon induction of hypoglycemia in GKO-NSG Tx mice (Figure 2c and Extended Data 2). As transplanted human islets are the sole source of circulating glucagon in GKO-NSG Tx mice, we conclude that insulin challenge and ensuing transient hypoglycemia evoked glucagon secretion by human α cells in these mice, an in vivo response not previously reported for human islets transplanted in mice. These results suggest human α cell mechanisms governing regulated glucagon secretion remained intact after transplantation.

Human islets establish a glucagon-signaling axis that corrects liver phenotypes in GKO-NSG mice

Glucagon signaling is an essential regulator of hepatic amino acid metabolism, gluconeogenesis, and glycogenolysis20, 31, 32. Consistent with prior mouse models of impaired glucagon signaling from glucagon or glucagon receptor deficiency20–22, we observed increased total plasma amino acid levels in GKO-NSG mice compared to NSG control littermates (Figure 3a). Moreover, measures of individual amino acids from plasma revealed that 23 of 28 amino acids profiled were significantly increased in GKO-NSG mice (Figure 3b and Extended Data 3). To examine if these changes could result from altered hepatic metabolism, expression of genes encoding enzymes involved in gluconeogenesis (G6pc and Pepck) and amino acid metabolism (Tat, Oat, Nnmt, and Gls2) were measured by qPCR. G6pc, Tat, Oat and Gls2 were significantly decreased in GKO-NSG mice compared to NSG controls (Figure 3d). To assess differences in glycogenolysis, liver glycogen levels were measured from fasted GKO-NSG and NSG control mice. We observed a trend of increased average hepatic glycogen levels in GKO-NSG mice compared to NSG controls (Figure 3c). Together, these data suggest that, like in previous studies of glucagon signaling loss20–22, 24, 33, gluconeogenesis and amino acid metabolism are impaired in GKO-NSG mice.

Figure 3. Human islet transplantation establishes a glucagon-signaling axis that corrects liver phenotypes in GKO-NSG mice.

Mice were examined for liver phenotypes associated with glucagon loss following transplantation of human islets. Data are from NSG control, GKO-NSG, and GKO-NSG mice post-transplantation (GKO-NSG Tx). (a) Total plasma amino acids from 5–7 month old mice (NSG vs. GKO-NSG P= 0.000198; GKO-NSG vs. GKO-NSG Tx P= 0.044206 by one-way ANOVA, with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test) (NSG mice, n= 8 males and 2 females; GKO-NSG mice, n= 4 males and 3 females; GKO-NSG Tx mice, n= 6 males). (b) Concentration of individual plasma amino acids that showed significant change in GKO-NSG mice by one-way ANOVA, with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (P values listed in Supplementary Table 2) (NSG mice, n= 10 males and 2 females; GKO-NSG mice, n= 5 males and 3 females; GKO-NSG Tx mice, n= 6 males). (c) Liver glycogen quantification from the left lobe of 6–8 month old mice (GKO-NSG vs. GKO-NSG Tx: P= 0.015738 by one-way ANOVA, with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test) (NSG mice, n= 9 males and 1 female; GKO-NSG mice, n= 6 males and 2 females; GKO-NSG Tx mice, n= 6 males). (d) Gene expression in the left liver lobe of indicated genes from 6–8 month old mice (significant P values generated by one-way ANOVA, with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test are listed in Supplementary Table 2) (NSG mice, n= 9 males; GKO-NSG mice, n= 6 males; GKO-NSG Tx mice, n= 6 males). Dashed lines indicate limit of detection. Data are represented as mean of biological replicates with individual data points overlaid and error bars indicate ± SEM. N.S.= not significant. * NSG vs. GKO-NSG mice and + GKO-NSG vs. GKO-NSG Tx mice (b and d). + or * P ≤ 0.05, ++or ** P ≤ 0.01, +++ or ***P ≤ 0.001. See also Supplementary Table 2 and Extended Data 3.

To determine if human islet-derived glucagon was able to rescue the phenotypes found in GKO-NSG host tissues, we examined GKO-NSG Tx mice fourteen weeks after human islet transplantation. The liver defects were corrected, including reduction of total and individual plasma amino acids (Figures 3a-b and Extended Data 3), decreased liver glycogen levels (Figure 3c), and normalization of hepatic G6pc, Tat, Oat, and Gls2 expression (Figure 3d). Together, these findings suggest that glucagon secretion by human islet grafts durably reconstituted a physiological islet-liver signaling axis in GKO-NSG mice.

Glucagon secreted by human islet grafts corrects α cell hyperplasia in GKO-NSG mice

Impaired glucagon signaling in mice can evoke compensatory α cell proliferation and hyperplasia19, 23, 24, 34. Elevated circulating amino acids in mice lacking glucagon signaling were previously demonstrated to induce α cell proliferation and hyperplasia20–22 through a mechanism involving an amino acid transporter, Slc38a5 20, 21. As GKO-NSG mice exhibited hyperaminoacidemia, we assessed islet α cell and β cell hyperplasia and proliferation in GKO-NSG islets. For α cell morphometry in GKO-NSG islets, we used a proglucagon-specific antibody that detected both wild type and internally-deleted GKO proglucagon (proglucagonΔ). Antibodies to MafB, an adult α cell-specific islet transcription factor in mice35 (Figures 4a-c), were also used to identify changes in islet α cell mass. Islet morphometry in adult GKO-NSG mice revealed an increased percentage of α cells expressing the proliferation marker Ki67 (Figures 4e-h) and increased α cell mass (Figures 4a-d). No differences were observed in β cell mass or proliferation in islets of GKO-NSG and NSG control mice (Figures 4a-h). To examine if α cell hyperplasia might be driven by a previously described mechanism involving Slc38a5 20, 21, islets from GKO-NSG and NSG control mice were surveyed for Slc38a5 protein production. As expected, GKO-NSG mice showed increased α cell production of Slc38a5 compared to islets from NSG control mice and, as previously reported36, we also detected Slc38a5 in acinar cells (Figures 4i-n). Thus, like in prior models of glucagon deficiency, we observed adaptive α cell expansion, stimulated by hyperaminoacidemia and accompanied by increased α cell Slc38a5 production.

Figure 4. Human islet-derived glucagon corrects GKO-NSG α cell hyperplasia.

(a-c) Representative immunostaining for quantification of α and β cell mass (d) from 4–8 month old NSG control, GKO-NSG, and GKO-NSG Tx mice with antibodies detecting Proglucagon (green), Insulin (white), and MafB (red) (NSG vs. GKO-NSG P= 0.000958; GKO-NSG vs. GKO-NSG Tx P= 0.001530 by one-way ANOVA, with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test) (NSG mice, n= 3 males and 1 female; GKO-NSG mice, n= 3 males and 1 female; GKO-NSG Tx mice, n= 5 males). (e-g) Representative immunostaining for quantification of α and β cell proliferation (h) in 4–8 month old NSG control, GKO-NSG, and GKO-NSG Tx mouse pancreata using antibodies detecting Proglucagon (green), Insulin (white), and Ki67 (red). (P= 0.022675 by two-tailed Student’s t-test) (NSG mice, n= 3 males and 1 female; GKO-NSG mice, n= 3 males and n= 1 female; GKO-NSG Tx mice, n= 3 males). For (a-h): images for morphometric quantifications are acquired from 10 pancreatic sections per individual mouse (see methods). (i-q) Representative immunostaining of Slc38a5 expression in NSG control, GKO-NSG, and GKO-NSG Tx mouse pancreata using antibodies detecting Proglucagon (green), Insulin (white), and Slc38a5 (red). Similar results for Slc38a5 staining were seen across n= 3 NSG control, n= 5 GKO-NSG, and n= 3 GKO-NSG Tx mice. All images are shown at the same resolution; scale bars, 50 μm. Data are represented as mean of biological replicates with individual data points overlaid and error bars indicate ± SEM. N.S.= not significant. * P ≤ 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01, *** P ≤ 0.001.

Since human glucagon from islet grafts restored circulating amino acid levels in GKO-NSG mice (Figures 3a-b), we next assessed the impact on host islet α cells in GKO-NSG Tx mice and controls. Morphometry analysis revealed that host α cell mass ‘normalized’ in GKO-NSG Tx mice compared to NSG control mouse islets (Figures 4c-d), and was accompanied by a reduction in the number of proglucagonΔ+ Ki67+ cells (Figures 4g-h), and loss of Slc38a5 in mouse α cells (Figures 4o-q). Thus, restoration of glucagon signaling by human islet grafts in GKO-NSG mice corrected adaptive pancreatic islet α cell expansion observed in GKO-NSG mice. However, further studies are needed to assess the basis of this correction, including the possibility of α cell apoptosis24.

Restoration of glucose and insulin regulation in transplanted GKO-NSG mice

Glucagon increases blood glucose levels by promoting hepatic glucose output, and is also implicated in regulating normal insulin secretion37–39. Hence, mice lacking glucagon signaling are hypoinsulinemic18 and hypoglycemic19, 23, 33. Consistent with these extant glucagon signaling mutant mouse models, GKO-NSG mice had chronically reduced blood glucose levels and lower ad libitum fed plasma insulin levels compared to NSG control mice (Figures 5a-b, Extended Data 1d, and Extended Data 4b-c). Four weeks after human islet transplantation, ad libitum fed blood glucose and total plasma insulin levels in GKO-NSG Tx mice were increased and indistinguishable from NSG controls (Figures 5a-b and Extended Data 4b-c). In GKO-NSG Tx mice, total plasma insulin levels reflected contributions from both host mouse β cells and transplanted human islets (Figure 5b and Extended Data 4d). While circulating glucagon levels differed in ad libitum fed NSG and GKO-NSG Tx mice, human glucagon in GKO-NSG Tx mice was sufficient to maintain normoglycemia (Figures 2b, 5a, and Extended Data 4a-b). Thus, transplanted human islets improved glycemic and insulin control in GKO-NSG Tx mice.

Figure 5. Improved glucose and insulin regulation in transplanted GKO-NSG mice.

4–6 month old GKO-NSG mice post-transplantation (GKO-NSG Tx), GKO-NSG mice, and NSG control mice were assessed for ad libitum fed blood glucose (a) (NSG vs. GKO-NSG P= 0.000086; GKO-NSG vs. GKO-NSG Tx P= 0.004522 by one-way ANOVA, with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test) (NSG mice, n= 10 males and 3 females; GKO-NSG mice, n= 12 males and 2 females; GKO-NSG Tx mice, n= 6 males) and plasma insulin levels (b) (NSG vs. GKO-NSG P= 0.000047; GKO-NSG vs. GKO-NSG Tx P= 0.000066 by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test) (NSG mice, n= 9 males and 3 females; GKO-NSG mice, n= 11 males and 2 females; GKO-NSG Tx mice, n= 6 males). 5–7 month old mice were given an intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test and monitored for blood glucose measures (c) and plasma mouse (d) and human (e) insulin levels (P values generated by Repeated Measures ANOVA, with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test are listed in Supplementary Table 3). For (c-e): NSG mice, n= 3 males; GKO-NSG mice, n= 3 males; GKO-NSG Tx mice, n= 4 males. Human insulin excursion is measured by human insulin-specific ELISA in the same IPGTT test as in panels (c) and (d). Dashed lines indicate limit of detection. Data are represented as mean of biological replicates with individual data points overlaid and error bars indicate ± SEM. N.S.= not significant. * NSG vs. GKO-NSG mice and + GKO-NSG vs. GKO-NSG Tx mice (c-d). + or * P ≤ 0.05, ++ or ** P ≤ 0.01, +++ or *** P ≤ 0.001. See also Supplementary Table 3 and Extended Data 4.

To examine insulin and glucose regulation further in GKO-NSG mice after human islet transplantation, we performed an intraperitoneal glucose challenge. Compared to NSG controls, glucose clearance by GKO-NSG mice was faster (Figure 5c) and accompanied by an exaggerated (mouse) insulin excursion (Figure 5d). Glucose and insulin excursions in GKO-NSG Tx mice more closely resembled that of NSG controls (Figures 5c-d). Dynamic total circulating insulin levels in GKO-NSG Tx mice reflected a combination of mouse and human insulins (Figures 5d-e). Notably, it appeared that human insulin release from transplanted islets was well-regulated during glucose challenge, including an acute hormone rise followed by clearance from the circulation (Figure 5e). These data suggest that human islet-derived glucagon improved glycemic and insulin regulation in GKO-NSG Tx mice, and thus highlight the role of glucagon in maintaining euglycemia and normal insulin secretion.

Excessive glucagon secretion by transplanted T2D islets in GKO-NSG mice

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is often associated with increased circulating glucagon levels, which appear less responsive to inhibitory elevations in blood glucose40, 41. However, it remains unclear if hyperglucagonemia in T2D reflects increased glucagon secretion by islets. We used in vitro assays and human islet transplantation into GKO-NSG mice to examine glucagon secretion by islets from subjects with T2D (Extended Data 5 and Figure 6). Compared to control islets from non-diabetic donors, islets from T2D donors had similar increases of glucagon secretion in response to glucose reduction in vitro: however, in 2 out of 3 T2D donor islets, the response to the secretagogue L-arginine was exaggerated (Extended Data 5a). Transplantation of T2D islets into GKO-NSG mice (hereafter, GKO-NSG Tx T2D) led to elevated plasma glucagon levels (Figure 6b and Extended Data 5c). However, there was no detectable difference in islet glucagon content between non-diabetic and T2D donors (Extended Data 5b). Hyperglucagonemia was accompanied by an average glycemic increase of 32 mg/dL in fasted GKO-NSG Tx T2D mice, (96± 8 vs. 128 ± 8 mg/dL; P= 0.042886; Extended Data 5d), and a trend toward increased glycemia during ad libitum feeding (P= 0.071059; Figure 6a).

Figure 6. Excessive glucagon secretion by transplanted T2D islets in GKO-NSG mice.

4–6 month old GKO-NSG mice transplanted with islets from non-diabetic (GKO-NSG Tx) or T2D diabetic (GKO-NSG Tx T2D) donors were assessed for ad libitum fed blood glucose levels (a), 6-hour fasted plasma glucagon levels (b) (P= 0.015626 by two-tailed Student’s t-test), and ad libitum fed plasma insulin levels (d). In (d), black dashed line indicates limit of detection for mouse insulin and red dashed line indicates limit of detection for human insulin. (e) 4.5–6.5 month old mice were challenged with human insulin; glucagon response to acute hypoglycemia was measured from plasma at 0 and 30-minutes post-insulin injection (0’ vs 30’: GKO-NSG Tx P= 0.002262 by paired two-tailed t-test, with Bonferroni correction) (GKO-NSG Tx vs. GKO-NSG Tx T2D 0’: P= 0.013266; 30’: P= 0.000985 by Mixed-effects analysis, with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test). For all data in (a-e), GKO-NSG Tx mice, n= 6 males; GKO-NSG Tx T2D n= 1 male and 2 females. Dashed lines indicate limit of detection. Data are represented as mean of biological replicates with individual data points overlaid and error bars indicate ± SEM. * P ≤ 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01, *** P ≤ 0.001. See also Extended Data 5.

Despite relative hyperglycemia and hyperglucagonemia in GKO-NSG Tx T2D mice, circulating total and human islet-derived insulin levels in these mice were comparable to those in GKO-NSG mice transplanted with islets from non-diabetic donors (Figures 6c-d and Extended Data 5e). When challenged with insulin and subsequent transient hypoglycemia, GKO-NSG Tx T2D mice had elevated plasma glucagon levels compared to GKO-NSG mice transplanted with non-diabetic human islets (Figure 6e and Extended Data 5f). Collectively, these results demonstrate that hyperglucagonemia in T2D reflects intrinsic islet defects in regulated glucagon secretion. Moreover, compared to in vitro secretion studies, defective T2D islet secretion was more robustly detected after transplantation in GKO-NSG mice, highlighting the need for in vivo systems to assess glucagon secretion.

Discussion

To address the absence of animal models to study regulated glucagon secretion from human islet α cells in vivo, here we used CRISPR/Cas9 to develop the GKO-NSG mouse. Human islets engrafted durably in GKO-NSG mice and retained regulated glucagon and insulin secretion. Reconstituting glucagon signaling to ‘glucagon-target’ organs like the pancreas and liver rescued multiple phenotypes associated with glucagon deficiency, including deviations in circulating glucose, amino acid, and insulin levels. Additionally, we provide index evidence that transplanted islets from human donors with T2D display chronically elevated glucagon output, accompanied by significantly increased blood glucose levels. Prior reports of mice that lack glucagon signaling18–23, 29, 42 revealed many phenotypes associated with loss of glucagon signaling in pancreatic islets and other organs - phenotypes that we observed in GKO-NSG mice. However, GKO-NSG mice also have distinct properties not previously reported18, 23, 29, likely reflecting preserved production of ‘nested’ proglucagon-derived peptides like GRPP, GLP-1, and GLP-2, in addition to the superior receptivity of the NSG strain background to xenotransplantation6, 7. While our approach led to the unavoidable loss of the oxyntomodulin and glicentin peptide hormones (which incorporate amino acids 1–29 of GCG), this also creates opportunities to study the in vivo functions of these hormones in GKO-NSG mice.

Glucagon is a crucial intercellular and inter-organ regulator of pancreatic islet cells, liver, and other organs43. Our results suggest that the GKO-NSG model should be useful for investigating these signaling interactions. Here, we observed that hyperaminoacidemia, hypoglycemia, α cell hyperplasia, and islet Slc38a5 production in GKO-NSG mice are reversed after human islet transplantation, indicating (re)-establishment of at least two homeostatic in vivo signaling axes mediated by human glucagon and circulating amino acids. The first signaling axis links transplanted human islets to the host liver and the second links the liver to native pancreatic islets cells. Reversion of hyperaminoacidemia and hypoglycemia reflect signaling of human glucagon to the host GKO-NSG liver, which then appropriately triggers glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis, and amino acid metabolism to correct hypoglycemia (Figures 3 and 5a). Thus, GKO-NSG mice should be useful in future studies to determine how α cells regulate glycemic levels, a phenotype that likely reflects multiple signals between the host liver and islets. For example, systematic modulation of variables like the number of transplanted human islets44 in GKO-NSG mice could be used to clarify the basis of distinct44, 45 mouse and human glycemic ‘set-points’. While reversion of liver phenotypes is largely driven by human islet-derived glucagon signaling, reversion of α cell hyperplasia in GKO-NSG Tx mice likely reflects corrected liver to native pancreas signaling. However, further studies are needed to assess the basis for this observation, including the possibility of host α cell apoptosis with glucagon repletion 24.

Studies here also demonstrate powerful ways the GKO-NSG mouse can be used to investigate human islets from subjects with diseases like diabetes. For example, our work compared in vivo glucagon output by transplanted islets from non-diabetic and T2D donors, and revealed that T2D islets maintained significantly increased glucagon output, providing index in vivo evidence that islet-intrinsic or α cell-intrinsic defects lead to excessive glucagon secretion in T2D. Moreover, relative hyperglucagonemia in GKO-NSG mice transplanted with T2D human islets was accompanied by a significant increase in fasted blood glucose levels, compared to mice transplanted with islets from non-diabetic donors. These data suggest that glucagon hypersecretion by islets in T2D may contribute to hyperglycemia. Notably, human insulin output in GKO-NSG Tx T2D mice did not increase in response to the elevated glycemic levels, indicating that β cell dysfunction is also maintained after T2D islet transplantation in GKO-NSG mice.

To evaluate the function of candidate T2D risk genes identified by GWAS and discover human islet β cell regulators, we previously used loss-, and gain-of-function genetics in human pseudo-islets transplanted in NSG mice4, 10. This experimental logic, using GKO-NSG mice, can be expanded to human α cells in islets from previously-healthy, pre-diabetic, or diabetic donors. Thus, we can now examine how α cell enriched genes3, 46 and genetic changes in diabetes mellitus3, 47, 48 impact human α cell identity and function. Aside from intrinsic genetic mechanisms governing hormone secretion from islet cells, intra-islet signaling between α cells, β cells, δ cells, and other islet cells is also known to regulate islet hormone secretion1, 37, 38, 49–55. To the extent that regulated interactions between human α cells, β cells, and δ cells are reconstituted and measurable in GKO-NSG mice, these mice could be useful for in vivo studies of these and other intra-islet signaling interactions. Moreover, we envision that GKO-NSG mice transplanted with islets from human donors (or other species) will be useful for examining how pharmacological agents, or acquired environmental stressors, like starvation or diet-induced obesity, impact human α cells. Using NSG mice, we recently reported that responses of transplanted human islet β cells to high fat diet challenge were distinct from those observed in (host) mouse β cells9. Additionally, GKO-NSG mice should be useful for assessing the function of transplanted islet-like cells produced from renewable sources like human stem cell lines56–60. Thus, GKO-NSG mice should be a valuable resource for in vivo studies of human islets, islet replacement cells using genetics, small molecules, or modeling of acquired in vivo physiological or pathological risk states in diabetes mellitus.

Methods

Glucagon gene targeting in NSG mice

GKO-NSG mice were generated through the NIDDK Type 1 Diabetes Resource (TIDR) and the Jackson Laboratory. Two mouse Gcg Exon 3 guide RNAs (sgRNA 3569: GAAGACAAACGCCACTCACA and sgRNA 3572: CAGACTCTTACCGGTTCCTCT) and the CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid were injected into NSG (NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ, The Jackson Laboratory, stock 005557) oocytes to generate founders. Out of 33 progeny, one male (termed 18–1) was confirmed by TOPO cloning and DNA sequencing to carry the desired in-frame deletion and bred to NSG females for germ line transmission. Verified F1 heterozygous offspring were used for further breeding to homozygosity. Subsequent genotyping were performed using PCR amplification with 3573_F1 (TGAGAACCACTGCAAGGCAAC) and 3575_R1 (AACGATCAATACAGCTAAGGTCTC) primers, which produce a 715 bp wildtype product or a 622 bp Gcg exon 3 deletion product (Figure 1b). Homozygous glucagon knockout mice were born at near Mendelian ratios, however some lethality was observed around weaning. To promote survival of GKO-NSG mice, mice were provided with DietGel 76A (Clear H2O) mixed with wet chow one week before weaning and for two weeks after weaning. Additionally, mice were provided with water supplemented with 0.045% D-glucose (Sigma-Aldrich) for two weeks after weaning. All mice, including littermate controls, were given this supplemental care. Mice were housed in a pathogen-free barrier facility at Stanford University Medical School, and were exposed to a normal 12-hour light cycle. Male and female mice (2–8 months old) were used for experiments along with age- and sex- matched control littermate NSG mice. GKO-NSG mice, i.e. NOD.Cg-Gcgem1Dvs Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/DvsJ (Strain 029819), are available through The Jackson Laboratory.

Human islet procurement and transplantation

Deidentified human pancreatic islets were procured through the Integrated Islet Distribution Program, Alberta Diabetes Institute IsletCore, and International Institute for the Advancement of Medicine. Five hundred human islet equivalents (IEQ) from previously healthy, nondiabetic organ donors (n=6) or type 2 diabetic donors (n=3) with less than 15-hour cold ischemia time (Table 1) were used for transplantation under the kidney capsule of GKO-NSG mice as previously described8,10. In brief, 2–5 month-old male and female GKO-NSG mice were used as transplantation recipients. Animals were anesthetized using ketamine/xylazine. Upon confirmation of appropriate depth of anesthesia, human islets resuspended in cold Matrigel (Corning) were transferred into the left renal capsular space of recipient mice through a 10ul PCR micro-pipet (Drummond).

Table 1.

Donor information of human islets used for transplantation studies

| Sample ID | Source ID | Age | Sex | BMI | Purity | HbA1c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SAMN08773444 | 40 | M | 25.5 | 95% | 5.3 |

| 2 | R278 | 57 | M | 27.6 | 80% | 5.7 |

| 3 | SAMN09862214 | 31 | M | 31.8 | 80% | 5.3 |

| 4 | R292 | 47 | M | 27.6 | 90% | 5.6 |

| 5 | SAMN10574375 | 60 | F | 30.6 | 80% | 6 |

| 6 | R338 | 30 | M | 25.5 | 90% | 5.3 |

| 7 | SAMN11157311 | 34 | F | 31.7 | 92% | 7.3 |

| 8 | AGJU173 | 53 | F | 29.2 | 75% | 9.8 |

| 9 | R347 | 57 | M | 27.9 | 75% | 6.3 |

Glucose tolerance testing

After a 5-hour fast (starting from 9–10 AM), mice were administered an intraperitoneal (IP) injection of D-glucose (3 g/kg body weight). Blood glucose levels were measured with a Contour glucometer (Bayer) at 0, 5, 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, and 120 minutes post injection and EDTA-treated plasma samples were collected for insulin hormone assays at the same time intervals. 5–7 month-old male GKO-NSG, GKO-NSG Tx, and NSG littermate control mice were used. For circulating GLP-1 assessment, mice were fasted for 6 hours (starting at 9AM), then D-glucose (6 g/ kg body weight) was given by oral gavage. Blood glucose was measured with a Contour glucometer (Bayer) at 0, 5, 15, 30, 60, 90, 120, and 180 minutes post-gavage and EDTA-, DPP4-inibitor- (Millipore), and HALT protease inhibitor- (Thermo Scientific) treated plasma samples were collected at 0, 15, and 30 minutes post-gavage. 2.5–3 month-old male and female GKO-NSG and NSG littermate control mice were used.

Insulin tolerance test (ITT)

After a 5-hour fast (starting from 9–10 AM), mice were administered an intraperitoneal injection of Novolin R U-100 (1U/kg body weight). Blood glucose levels were measured with a Contour glucometer (Bayer) at 0, 15, and 30 minutes post insulin injection. EDTA- and protease cocktail-treated (Bimake) plasma samples were collected at 0 and 30 minutes post-insulin injection for circulating glucagon measurement. 4.5–6.5 month-old male and female GKO-NSG, GKO-NSG Tx, GKO-NSG Tx T2D, and NSG littermate control mice were used.

Plasma hormones and amino acids assays

Plasma insulin and glucagon levels were assessed using an ultrasensitive mouse insulin ELISA (Mercodia) and glucagon ELISA (Mercodia), respectively. Circulating human insulin levels in transplanted GKO-NSG recipients were measured with a human insulin ELISA (Mercodia). Due to ultrasensitive mouse insulin ELISA cross-reactivity with human insulin, mouse insulin from GKO-NSG Tx and GKO-NSG Tx T2D plasma was determined by subtracting values obtained from human insulin ELISA. 2–7 month-old male and female GKO-NSG, GKO-NSG Tx, GKO-NSG Tx T2D, and NSG littermate control mice were used. Plasma GLP-1 levels were quantified with an active GLP-1 ELISA (Eagle Biosciences) and a total GLP-1 NL-ELISA (Mercodia). 2.5–3 month-old male and female GKO-NSG, GKO-NSG Tx, and NSG littermate control mice were used. Mice were fasted for 4-hours (starting from 9:30–10:30 AM) prior to blood collection for amino acid quantification. Plasma amino acid levels were determined using a L-Amino Acid Quantitation Kit (Sigma Aldrich) following manufacture’s instruction, and individual amino acids by the Vanderbilt University Hormone Assay and Analytical Services Core using a Biochrom 30 amino acid analyzer. 5–7 month-old male and female GKO-NSG, GKO-NSG Tx, and NSG littermate control mice were used.

Immunostaining and morphometry

Pancreata were weighed (wet weight), fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C, and 10 μm thick cryosections were prepared. At least 10 sections per pancreas spaced at least 100 μm apart were stained with the following primary antibodies: Guinea pig anti-insulin (Dako, 1:500), Rabbit anti-proglucagon (Cell Signaling Technologies, 1:400), Mouse anti-proglucagon (Novus Biologicals, 1:300), Guinea pig anti-glucagon (Takara, 1:2000), Rabbit anti-Mafb (Bethyl, 1:250), Rat anti-Ki67 (Biolegend, 1:100), Rabbit anti-Slc38a5 (Abcam 1:200). Hoechst 33342 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 1:2000) was used to detect nuclei. For fluorescent detection of primary antibodies, sections were subsequently stained with Alexa Flour-conjugated (488, 555, or 647) secondary antibodies (1:500, donkey-anti-primary-host, Jackson ImmunoResearch). Detailed product information and validation methods are provided in Reporting Summary.

Fluorescent micrographs were captured using a Zeiss AxioM1 microscope and a Leica SP2 confocal microscope. Images were processed in Image J for islet cell mass quantification and Image-Pro Plus for islet cell proliferation using previously described methods61, 62. For islet mass analysis, fluorescent micrographs were captured with a 10X objective lens on a Zeiss AxioM1 microscope and individual 10X images were captured as tiled images of entire pancreatic sections using the tiling feature in Zeiss AxioVision software (version 4.8). Pancreata were imaged using fluorescent detectors for secondary antibodies, Hoechst, and an autoflourescent ‘background’ channel used to capture the entire pancreatic tissue section area. Merged Hoechst and ‘background’ tiled images were used to measure total pancreatic area, where tissue was manually traced in Image J using the freehand selection tool and areas of traces were measured using the measure function. To measure hormone positive areas, tiled images of individual channels were thresholded and positive areas were measured using the analyze particles function. To calculate islet cell mass, total hormone positive area was divided by the total pancreatic area and then subsequently multiplied by pancreatic weight. For islet proliferation analysis and representative images presented in this manuscript, fluorescent micrographs were captured with a 40x objective lens. 200 islets per pancreata were randomly selected for islet proliferation imaging and analysis. Total α and β cell number were measured using individual channel images and were determined by performing an initial manual count (for each animal) to estimate an average cell number/fluorescent area; once initial counts were performed, subsequent counting was performed using the automatic bright object count function in Image-Pro Plus software (version 5). Islet cell co-expression of Ki67 and hormones was analyzed using merged channel images; Ki67+ hormone+ cells were manually counted in Image-Pro Plus software (version 5) using the manual count function. 4–8 month-old male and female GKO-NSG, GKO-NSG Tx, and NSG littermate control mice were used.

Liver glycogen content assessment

60 mg of tissue from the liver (left lateral lobe) was collected from mice fasted for 5 hours (starting from 9–10 AM), and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Liver samples were homogenized on ice in buffer containing protease cocktail inhibitor (Bimake) and quantified using a fluorometric glycogen assay kit according to manufacturer’s instructions (Cayman Chemicals). 6–8 month-old male and female GKO-NSG, GKO-NSG Tx, and NSG littermate control mice were used.

RNA extraction and quantitative PCR

90 mg of tissue from the liver (left lateral lobe) was collected from mice fasted for 5 hours. Then, total RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) and complementary DNA was synthesized using Maxima First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Thermo Fischer Scientific) following manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed using TaqMan assays (Supplementary Table 1) and reagents from Applied Biosystems with Actb used as an endogenous control. 6–8 month-old male GKO-NSG, GKO-NSG Tx, and NSG littermate control mice were used.

In vitro glucagon secretion assay

Technical replicates (2–3) containing 25–30 human islets were used for in vitro glucagon secretion assays. Secretion assay media was composed of RPMI 1640 (Gibco) supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum (HyClone) and the glucose (Sigma-Aldrich) concentrations detailed below. In an initial equilibration step, islets were incubated twice in media containing 7 mM glucose for 45 minutes (90 minutes total). After pre-incubation steps, islets were incubated in media containing 7 mM glucose, 1 mM glucose and, 1 mM glucose + L-Arginine (Sigma-Aldrich) for 60 minutes each and supernatant was collected. At the end of the assay, islets were lysed by sonication in a TE/BSA buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl (Calbiochem), 1 mM EDTA (Calbiochem), and 0.1% BSA (Fisher)) that was subsequently mixed with equal parts of an acid-ethanol solution to extract the total islet glucagon content. Secreted glucagon (from islet supernatant) and total glucagon (islet lysate) were quantified using a glucagon ELISA kit (Mercodia). Measures of secreted glucagon were normalized to total glucagon content (presented as a percentage of total glucagon content). Donor information is listed in Table 1.

Study approvals

All studies involving human islets were conducted in accordance with Stanford University Institutional Review Board guidelines. All animal experiments and methods were approved by and performed in accordance with the guidelines provided by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Stanford University.

Statistics

Data are presented as the mean of biological replicates ± SEM with individual data points overlaid. All data are the result of one experiment per biological replicate, where each data point is a distinct biological replicate (n values listed in figure legends), except where noted in Extended Data 5a (figure legend). GraphPad Prism v. 7 and Microsoft Excel 2016 were used to perform Student’s t-test (two-tailed), repeated measures ANOVA (with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test), Mixed-effects analysis (with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test), and one-way ANOVA (with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test) for statistical comparisons between data. For data point values falling below detection limits, statistical tests were run with these data points as 0. As noted in figure legends, data that did not show a normal distribution (plasma glucagon measures from GKO-NSG mice) were omitted from statistical tests. P values ≤0.05 were considered significant. Exact P values for data with significant differences are listed in figure legends or in supplementary tables.

Extended Data

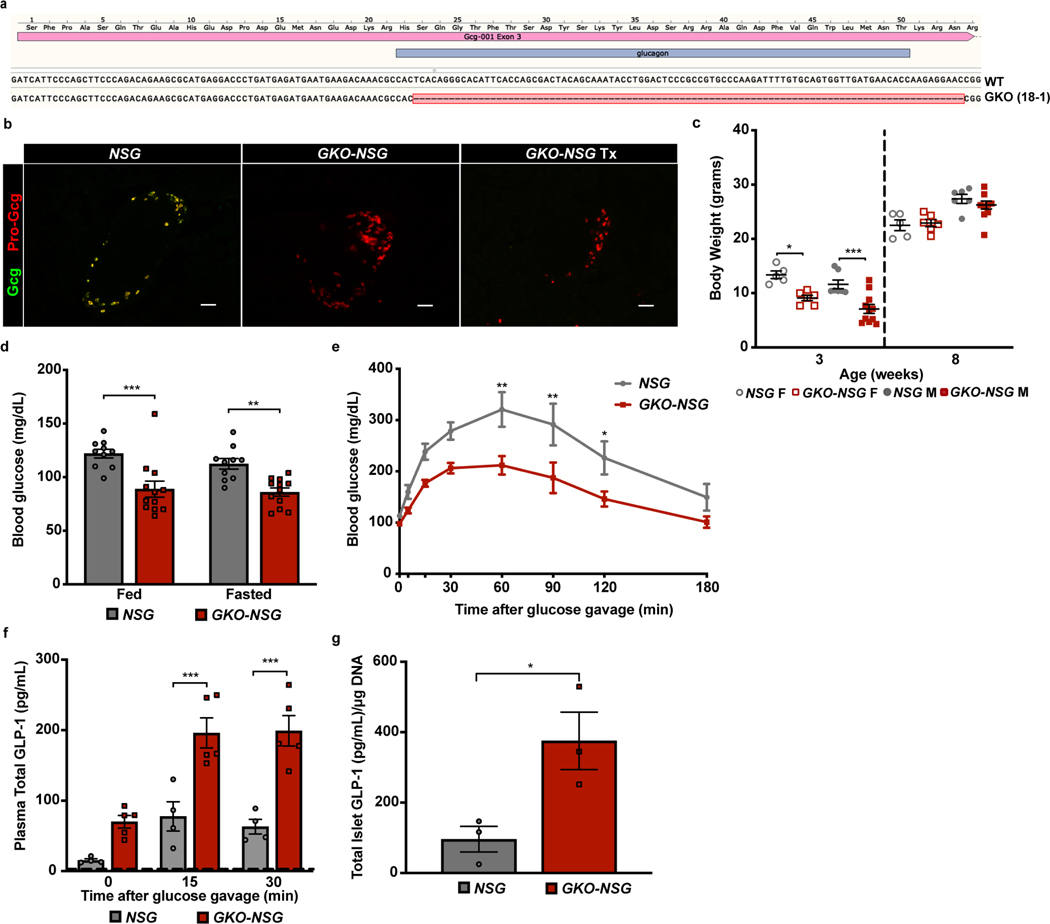

Extended Data Fig. 1. Design and characterization of GKO-NSG mice.

Related to figure 1. (a) Sequence from GKO-NSG founder (18–1) showing an in-frame deletion of 93 base pairs within exon 3 of the Gcg gene compared to the wild type NSG sequence (WT). Pink bar on top depicts exon 3 of Gcg. Blue bar represents nucleotide sequences encoding mature glucagon peptide. Red-highlighted dashes indicate deleted nucleotides in founder 18–1. (b) Representative immunostaining of GKO-NSG pancreatic islets with antibodies raised against mature glucagon (GCG, green) and proglucagon (Pro-GCG, red) - peptide sequences of GLP-1 (7–17). Similar results were seen across n= 3 NSG littermate control, n= 3 GKO-NSG, and n= 2 GKO-NSG Tx mice. (c) Body weight of male and female GKO-NSG and NSG control littermates at 3 and 8-weeks of age (3-week old female mice P= 0.025667 and 3-week old male mice P= 0.000454 by Repeated Measures ANOVA, with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test) (NSG mice, n= 7 males and 5 females; GKO-NSG mice, n= 11 males and 6 females). (d) Blood glucose measures of 2–3 month old GKO-NSG and NSG control mice during ad libitum feeding or after a 3-hour fast (fed: P= 0.000223; fasted: P= 0.003003 by Repeated Measures ANOVA, with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test) (NSG mice, n= 6 males and 4 females; GKO-NSG mice, n= 4 males and 8 females). (e) GKO-NSG and NSG control blood glucose measures over 180 minutes post oral glucose gavage (60’: P= 0.001383; 90’: P= 0.002618; 120’: P= 0.040657 by Repeated Measures ANOVA, with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test) (6g/kg body weight) (NSG mice, n= 5 males and 3 females; GKO-NSG mice, n= 8 males and 2 females) and (f) plasma total GLP-1 levels from 2.5–3 month old GKO-NSG and NSG controls following oral glucose challenge (15’: P= 0.000194, and 30’: P= 0.000034 by Repeated Measures ANOVA, with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test) (NSG mice, n= 4 males; GKO-NSG mice, n= 5 males). (g) Quantification of active GLP-1 present in islet lysates from 5–7 month old NSG (n= 3 males) and GKO-NSG (n= 3 males) mice (P= 0.035323 by two-tailed Student’s t-test). Dashed lines indicate limit of detection. Scale bars, 50 μm. Data are represented as mean of biological replicates with individual data points overlaid and error bars indicate ± SEM. * P ≤ 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01, *** P ≤ 0.001.

Extended Data Fig. 2. Blood glucose reduction following insulin challenge.

Related to Figure 2. Percent of basal blood glucose 30-minutes post insulin injection (1U/kg body weight) from 4.5–6.5 month old NSG, GKO-NSG, and GKO-NSG Tx mice (P= 0.017712 by one-way ANOVA, with Tukey’s multiple comparison test) (NSG mice, n= 5 males; GKO-NSG mice, n= 2 males and 1 female; GKO-NSG Tx mice, n= 5 males). Data are represented as mean of biological replicates with individual data points overlaid and error bars indicate ± SEM. * P ≤ 0.05.

Extended Data Fig. 3. Concentrations of individual plasma amino acids showing no change in GKO-NSG mice.

Related to Figure 3. Concentration of individual plasma amino acids that showed no significant changes in 6–7 month old GKO-NSG mice (NSG mice, n= 10 males and 2 females; GKO-NSG mice, n= 5 males and 3 females; GKO-NSG Tx mice, n= 6 males). Data are represented as mean of biological replicates with individual data points overlaid and error bars indicate ± SEM.

Extended Data Fig. 4. Further assessment of blood glucose, plasma insulin, and glucagon phenotypes in GKO-NSG mice after human islet transplantation.

Related to Figure 5. Data are from 4–6 month old NSG control, GKO-NSG, and GKO-NSG mice post-transplantation (GKO-NSG Tx). (a) Plasma glucagon levels in ad libitum fed mice (NSG vs. GKO-NSG Tx: P= 0.005112 by two-tailed Student’s t-test). Due to the distribution of data from GKO-NSG mice, these data points were omitted from statistical analysis. (NSG mice, n= 10 males and 3 females; GKO-NSG mice, n= 12 males and 1 female; GKO-NSG Tx mice, n= 6 males). Blood glucose (b) (P= 0.013846 by one-way ANOVA, with Tukey’s multiple comparison test) (NSG mice, n= 10 males and 3 females; GKO-NSG mice, n= 8 males and 2 females; GKO-NSG Tx mice, n= 6 males) and plasma insulin levels (c) (NSG mice, n= 10 males and 3 females; GKO-NSG mice, n= 7 males and 2 females; GKO-NSG Tx mice, n= 6 males) in fasted mice. (d) Mouse and human plasma insulin levels in ad libitum fed GKO-NSG Tx mice (n=6 males). Dashed lines indicate limit of detection (d: black dashed line indicates limit of detection of mouse insulin and red dashed line indicates limit of detection of human insulin). Data are represented as mean of biological replicates with individual data points overlaid and error bars indicate ± SEM. * P ≤ 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01, *** P ≤ 0.001.

Extended Data Fig. 5. In vitro characterization of donor human islets and more physiological assessment of GKO-NSG mice transplanted with islets either non-diabetic or T2D diabetic donors.

Related to Figure 6. (a) In vitro glucagon secretion assay on islets from non-diabetic (n= 4 donors) and type 2 diabetic donors (n= 3 donors), shown as technical replicates from individual donors. (b) Glucagon content of donor islets transplanted into GKO-NSG mice (P=0.558605 by two-tailed Student’s t-test; non-diabetic donor n= 5, type 2 diabetic donor n= 3). Data in (c-e) are from 4–6 month old GKO-NSG mice post-transplantation with islets from non-diabetic (GKO-NSG Tx) or type 2 diabetic donors (GKO-NSG Tx T2D). For data presented in (c-e): GKO-NSG Tx mice, n= 6 males; GKO-NSG Tx T2D mice n= 1 male and 2 females. (c) Plasma glucagon levels in ad libitum fed mice (P= 0.034687 by two-tailed Student’s t-test). Blood glucose (d) (P= 0.042886 by two-tailed Student’s t-test) and plasma insulin levels (e) in 6-hour fasted mice. (f) Percent of basal blood glucose 30-minutes post insulin injection (1U/kg body weight) from 4.5–6.5 month old GKO-NSG Tx and GKO-NSG Tx T2D mice (GKO-NSG Tx mice, n= 5 males; GKO-NSG Tx T2D n= 1 male and 1 female). Dashed lines indicate limit of detection. Data are represented as mean of biological replicates with individual data points overlaid, except in a, where individual data points represent technical replicates from single donors. Error bars indicate ± SEM. * P ≤ 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01, *** P ≤ 0.001.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank past and current members of the Kim group for advice and encouragement, Dr. S. Park for assistance in gene targeting, Dr. K. Abraham (NIDDK/NIH) for guidance in initial stages of this work, Dr. O. McGuinness and the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Hormone Core (DK059637 and DK020593) for amino acid measurements and advice, Dr. E. Walker for advice on glycogen quantification, the Stanford University Veterinary Service Center for animal care and advice, Dr. C. Sabatti and the Stanford Department of Biomedical Data Science Data Studio for advice on statistical analyses, the Stanford Cell Sciences Imaging Facility for microscope usage, and Dr. D. Serreze (JAX) for generation of mouse lines. We also thank the Integrated Islet Distribution Program (UC4 DK098085-02), Alberta Diabetes Institute IsletCore, and International Institute for the Advancement of Medicine for processing and coordinating human islet distribution. This work was supported by the Type 1 Diabetes Mouse Resource (1UC4DK097610 to D. Serreze), a graduate research fellowship award from the National Science Foundation (DGF-114747 to K. Tellez), RO1 awards (DK107507; DK108817; CA21192701 to S.K.Kim) and a U01 award (DK120447 to Dr. P. MacDonald, Univ. of Alberta). Work in the Stein lab was supported by NIH grants (DK106755, DK050203, and DK090570 to R.W. Stein). Work in the Kim lab was also supported by NIH grant P30 DK116074, the HL Snyder Foundation, the Mulberry Foundation, a gift from S. and M. Kirsch, and by the Stanford Islet Research Core, and Diabetes Genomics and Analysis Core of the Stanford Diabetes Research Center.

Footnotes

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References:

- 1.Gromada J, Franklin I. & Wollheim CB α-Cells of the Endocrine Pancreas: 35 Years of Research but the Enigma Remains. Endocr. Rev 28, 84–116 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKnight KD, Wang P. & Kim SK Deconstructing pancreas development to reconstruct human islets from pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 6, 300–8 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xin Y. et al. RNA Sequencing of Single Human Islet Cells Reveals Type 2 Diabetes Genes. Cell Metab. 24, 608–615 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arda HE et al. Age-Dependent Pancreatic Gene Regulation Reveals Mechanisms Governing Human β Cell Function. Cell Metab. 23, 909–920 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodriguez-Diaz R. et al. Alpha cells secrete acetylcholine as a non-neuronal paracrine signal priming beta cell function in humans. Nat. Med 17, 888–892 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishikawa F. et al. Development of functional human blood and immune systems in NOD/SCID/IL2 receptor {gamma} chain(null) mice. Blood 106, 1565–73 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shultz LD et al. Human lymphoid and myeloid cell development in NOD/LtSz-scid IL2R gamma null mice engrafted with mobilized human hemopoietic stem cells. J. Immunol 174, 6477–89 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dai C. et al. Age-dependent human β cell proliferation induced by glucagon-like peptide 1 and calcineurin signaling. J. Clin. Invest 127, 3835–3844 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dai C. et al. Stress-impaired transcription factor expression and insulin secretion in transplanted human islets. J. Clin. Invest 126, 1857–1870 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peiris H. et al. Discovering human diabetes-risk gene function with genetics and physiological assays. Nat. Commun 9, 3855 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bell GI, Sanchez-Pescador R, Laybourn PJ & Najarian RC Exon duplication and divergence in the human preproglucagon gene. Nature 304, 368–371 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heinrich G, Gros P. & Habener JF Glucagon gene sequence. Four of six exons encode separate functional domains of rat pre-proglucagon. J. Biol. Chem 259, 14082–7 (1984). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drucker DJ, Philippe J, Mojsov S, Chick WL & Habener JF Glucagon-like peptide I stimulates insulin gene expression and increases cyclic AMP levels in a rat islet cell line. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 84, 3434–8 (1987). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holst JJ The Physiology of Glucagon-like Peptide 1. Physiol. Rev 87, 1409–1439 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho YM, Fujita Y. & Kieffer TJ Glucagon-Like Peptide-1: Glucose Homeostasis and Beyond. Annu. Rev. Physiol 76, 535–559 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drucker DJ, Habener JF & Holst JJ Discovery, characterization, and clinical development of the glucagon-like peptides. J. Clin. Invest 127, 4217–4227 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knop FK EJE PRIZE 2018: A gut feeling about glucagon. Eur. J. Endocrinol 178, R267–R280 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayashi Y. et al. Mice Deficient for Glucagon Gene-Derived Peptides Display Normoglycemia and Hyperplasia of Islet α-Cells But Not of Intestinal L-Cells. Mol. Endocrinol 23, 1990–1999 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gelling RW et al. Lower blood glucose, hyperglucagonemia, and pancreatic cell hyperplasia in glucagon receptor knockout mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 100, 1438–1443 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Solloway MJ et al. Glucagon Couples Hepatic Amino Acid Catabolism to mTOR- Dependent Regulation of α-Cell Mass. Cell Rep. 12, 495–510 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dean ED et al. Interrupted Glucagon Signaling Reveals Hepatic α Cell Axis and Role for L-Glutamine in α Cell Proliferation. Cell Metab. 25, 1362–1373.e5 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim J. et al. Amino Acid Transporter Slc38a5 Controls Glucagon Receptor Inhibition- Induced Pancreatic α Cell Hyperplasia in Mice. Cell Metab. 25, 1348–1361 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Furuta M. et al. Defective prohormone processing and altered pancreatic islet morphology in mice lacking active SPC2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 94, 6646–51 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Webb GC, Akbar MS, Zhao C, Swift HH & Steiner DF Glucagon replacement via micro-osmotic pump corrects hypoglycemia and alpha-cell hyperplasia in prohormone convertase 2 knockout mice. Diabetes 51, 398–405 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fowden AL The role of insulin in fetal growth. Early Hum. Dev 29, 177–181 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Milner RDG & Hill DJ Fetal growth control: the role of insulin and related peptides. Clin. Endocrinol. (oxf). 21, 415–433 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vuguin PM et al. Ablation of the Glucagon Receptor Gene Increases Fetal Lethality and Produces Alterations in Islet Development and Maturation. Endocrinology 147, 3995–4006 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ouhilal S. et al. Hypoglycemia, hyperglucagonemia, and fetoplacental defects in glucagon receptor knockout mice: a role for glucagon action in pregnancy maintenance. Am. J. Physiol. Metab 302, E522–E531 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng X. et al. Glucagon contributes to liver zonation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 115, E4111–E4119 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohneda A, Aguilar-Parada E, Eisentraut AM & Unger RH Control of pancreatic glucagon secretion by glucose. Diabetes 18, 1–10 (1969). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller RA et al. Targeting hepatic glutaminase activity to ameliorate hyperglycemia. Nat. Med 24, 518–524 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holst JJ, Wewer Albrechtsen NJ, Pedersen J. & Knop FK Glucagon and Amino Acids Are Linked in a Mutual Feedback Cycle: The Liver-α-Cell Axis. Diabetes 66, 235–240 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hancock AS, Du A, Liu J, Miller M. & May CL Glucagon Deficiency Reduces Hepatic Glucose Production and Improves Glucose Tolerance In Adult Mice. Mol. Endocrinol 24, 1605–1614 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vincent M. et al. Abrogation of Protein Convertase 2 Activity Results in Delayed Islet Cell Differentiation and Maturation, Increased α-Cell Proliferation, and Islet Neogenesis. Endocrinology 144, 4061–4069 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Artner I. et al. MafB: an activator of the glucagon gene expressed in developing islet alpha- and beta-cells. Diabetes 55, 297–304 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schaum N. et al. Single-cell transcriptomics of 20 mouse organs creates a Tabula Muris. Nature 562, 367–372 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sørensen H. et al. Immunoneutralization of endogenous glucagon reduces hepatic glucose output and improves long-term glycemic control in diabetic ob/ob mice. Diabetes 55, 2843–8 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Svendsen B. et al. Insulin Secretion Depends on Intra-islet Glucagon Signaling. Cell Reports 25, 1127–1134.e2 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Capozzi ME et al. Glucagon lowers glycemia when β-cells are active. JCI Insight (2019). doi: 10.1172/JCI.INSIGHT.129954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Müller WA, Faloona GR, Aguilar-Parada E. & Unger RH Abnormal Alpha-Cell Function in Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med 283, 109–115 (1970). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reaven GM, Chen Y-DI, Golay A, Swislocki ALM & Jaspan JB Documentation of Hyperglucagonemia Throughout the Day in Nonobese and Obese Patients with Noninsulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus*. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 64, 106–110 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bozadjieva N. et al. Loss of mTORC1 signaling alters pancreatic α cell mass and impairs glucagon secretion. J. Clin. Invest 127, 4379–4393 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Müller TD, Finan B, Clemmensen C, DiMarchi RD & Tschöp MH The New Biology and Pharmacology of Glucagon. Physiol. Rev 97, 721–766 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rodriguez-Diaz R. et al. Paracrine Interactions within the Pancreatic Islet Determine the Glycemic Set Point. Cell Metab. 27, 549–558.e4 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schwartz NS, Clutter WE, Shah SD & Cryer PE Glycemic thresholds for activation of glucose counterregulatory systems are higher than the threshold for symptoms. J. Clin. Invest 79, 777–81 (1987). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arda HE et al. A Chromatin Basis for Cell Lineage and Disease Risk in the Human Pancreas. Cell Syst. 7, 310–322.e4 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brissova M. et al. α Cell Function and Gene Expression Are Compromised in Type 1 Diabetes. Cell Rep. 22, 2667–2676 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Camunas-Soler J. et al. Pancreas patch-seq links physiologic dysfunction in diabetes to single-cell transcriptomic phenotypes. bioRxiv 555110 (2019). doi: 10.1101/555110 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van der Meulen T. et al. Urocortin3 mediates somatostatin-dependent negative feedback control of insulin secretion. Nat. Med 21, 769–776 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arrojo e Drigo R. et al. Structural basis for delta cell paracrine regulation in pancreatic islets. Nat. Commun 10, 3700 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vergari E. et al. Insulin inhibits glucagon release by SGLT2-induced stimulation of somatostatin secretion. Nat. Commun 10, 139 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cejvan K, Coy DH & Efendic S. Intra-islet somatostatin regulates glucagon release via type 2 somatostatin receptors in rats. Diabetes 52, 1176–81 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hauge-Evans AC et al. Somatostatin Secreted by Islet δ-Cells Fulfills Multiple Roles as a Paracrine Regulator of Islet Function. Diabetes 58, 403–411 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patton GS et al. Pancreatic immunoreactive somatostatin release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 74, 2140–2143 (1977). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weir GC, Samols E, Day JA & Patel YC Glucose and glucagon stimulate the secretion of somatostatin from the perfused canine pancreas. Metabolism 27, 1223–1226 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kroon E. et al. Pancreatic endoderm derived from human embryonic stem cells generates glucose-responsive insulin-secreting cells in vivo. Nat Biotechnol 26, 443–452 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Micallef SJ et al. INS GFP/w human embryonic stem cells facilitate isolation of in vitro derived insulin-producing cells. Diabetologia 55, 694–706 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Basford CL et al. The functional and molecular characterisation of human embryonic stem cell-derived insulin-positive cells compared with adult pancreatic beta cells. Diabetologia 55, 358–371 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pagliuca FW et al. Generation of Functional Human Pancreatic β Cells In Vitro. Cell 159, 428–439 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nair GG et al. Recapitulating endocrine cell clustering in culture promotes maturation of human stem-cell-derived β cells. Nat. Cell Biol 21, 263–274 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Method-only References

- 61.Chakravarthy H. et al. Converting adult pancreatic islet α cells into β cells by targeting both Dnmt1 and Arx. Cell Metab 25, 622–634. (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pauerstein PT et al. A radial axis defined by semaphorin-to-neuropilin signaling controls pancreatic islet morphogenesis. Development 144, 3744–3754. (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.