Abstract

Background

Familial atrial fibrillation, an autosomal dominant disease, was previously mapped to chromosome 10q22. One of the genes mapped to the 10q22 region is DLG5, a member of the MAGUKs (Membrane Associated Gyanylate Kinase) family which mediates intracellular signaling. Only a partial cDNA was available for DLG5. To exclude potential disease inducing mutations, it was necessary to obtain a complete cDNA and genomic sequence of the gene.

Methods

The Northern Blot analysis performed using 3' UTR of this gene indicated the transcript size to be about 7.2 KB. Using race technique and library screening the entire cDNA was cloned. This gene was evaluated by sequencing the coding region and splice functions in normal and affected family members with familial atrial fibrillation. Furthermore, haploid cell lines from affected patients were generated and analyzed for deletions that may have been missed by PCR.

Results

We identified two distinct alternately spliced transcripts of this gene. The genomic sequence of the DLG5 gene spanned 79 KB with 32 exons and was shown to have ubiquitous human tissue expression including placenta, heart, skeletal muscle, liver and pancreas.

Conclusions

The entire cDNA of DLG5 was identified, sequenced and its genomic organization determined.

Background

Atrial fibrillation is a chaotic atrial rhythm resulting from abnormal signal generation and conduction in the atria. The molecular basis for atrial fibrillation remains unknown. It usually occurs in association with structural or metabolic abnormalities. Atrial fibrillation, however, does occur in individuals with none of these causes, referred to as lone atrial fibrillation. Recently, we identified several families of multiple generations affected with atrial fibrillation with no other underlying cause detected. This subset of familial atrial fibrillation provides an opportunity to explore a molecular basis for atrial fibrillation.

Atrial fibrillation segregates as an autosomal dominant disease characterized by atrial fibrillation on an electrocardiogram [1]. We diagnosed atrial fibrillation in five families from Spain in which the arrhythmia was the primary manifestation and not associated with any gross cardiac or metabolic abnormality [1]. Genetic linkage analysis was performed and the locus responsible for atrial fibrillation in our family was mapped to 10q22 between markers D101786 and D10S1630, an area of about 11 cM [1]. We proceeded with the candidate gene approach and DLG5 was on of the genes mapped to the critical region between the flanking markers [2]. This gene belongs to the MAGUK (Membrane Associated Gyanylate Kinase) family of proteins known to form scaffolds for proteins involved in intracellular signal transduction [2]. The MAGUK family of proteins has been extensively studied in recent years and shown to play a role in the formation of cell junctions, maintenance of cell shape, [3-5] and clustering of channel proteins at the cell surface [6-8]. Given its location in our critical region and its function it was selected as a candidate for atrial fibrillation. A partial cDNA sequence of DLG5 (GenBank accession #AB011155) of about 5.3 K B was available. To determine if there is a mutation responsible for the disease, it is necessary to have the complete cDNA. Furthermore, recognizing that the responsible mutation may be present in one of the intron-exon splice junctions, it is also necessary to obtain the corresponding genomic sequence. Thus, we cloned and sequenced the cDNA of the DLG5 gene and, from the complete cDNA sequence, determined the intron-exon boundaries of the gene as well as its human tissue expression profile.

Materials And Methods

Northern blot analysis

The ESTym59b11 (ATCC clone #409942) clone was confirmed by sequencing a part of exon 31 and exon 32 with the 3' untranslated region of the DLG5 cDNA. It was used as a probe, labeled with the random primer labeling kit from Gibco with 32P-dCTP and hybridized to an adult multi tissue RNA blot from Clontech. Pre hybridization and hybridization were performed with Express Hyb. Solution (Clontech) using the manufacturer's protocol. The membrane was washed once with 2X SSC/0.1% SDS for 15 minutes at room temperature and twice in 0.2%X SSC/0.1% SDS for 20 minutes at 68 C°. Membranes were exposed to X-ray film (Kodak) overnight at -80 C.

Cloning and sequencing of the cDNA for DLG5

Using the RACE technique (Clontech, Marathon Ready Heart cDNA) as per manufacturer's protocol, products were generated using primers designed in the 5' end of the described cDNA DLG5. Nested RACE was performed on the product and the generated PCR product cloned by using TA cloning (Invitrogen). The clones were plated on kanamycin IPTG plates. Colonies were picked and grown in 5 ml LB-Kan broth. Subsequent to miniprep using Qiagen Miniprep Kit (QIAgen, Valencia, CA), the clones were sequenced on the ABI310 genetic analyzer using the Big Dye terminator chemistry. The Race primers are: Primer A 5' GCATACACTCCATTCTCCAGACTGATGC 3'; primer B (nested to primer A) 5'CACTCATGATGAGCTTGTACTCGCTGTA 3'; primer F 5'GTGTGGTAGAAGTCAGTCTCCTTGGCCA 3';primer E (nested to primer F) and 5'GCTGAATGGAGAGGTTCTCCACCTTCTC 3. We generated additional 1.702 KB of cDNA for this gene for a total cDNA length of 7.194 KB. The cDNA generated had an overlap of 305 bp with the published DLG5 cDNA (Genbank Acc. #AB011155) in the 5' end of the gene. We further cloned, in two pieces with an overlap of 226 bp, the cDNA covering about 2 Kb of this gene in the 5' end from bp 1–2007 of the cDNA. The clones were: Clone T/F 1–471 bp of 7.194 Kb cDNA [using primers T 5' GGTCTCAACTTAAACTCCAGCACCACGA 3' with the primer F] and clone G/A 246–2007 bp of 7.194 Kb cDNA [using primer G 5' GAGAAGGTGGAG AACCTCTCCATTCAGC 3' with primer A]. As mentioned there is an overlap of 226 bp (246–471 bp of 7.194 KB cDNA) between the two clones. We performed multiple RACE reactions using heart and placental cDNA until no further extension was made to the cDNA suggesting we had reached the end of the gene.

In addition to RACE, we also used PCR based heart library screening (Origene Technologies, Cat#1001). We isolated a clone that matched our RACE clone which gave confirmation to the cDNA sequence generated by the RACE technique. We used Sequencer 3.1 program to assemble our sequences. There was considerable overlap between the 305 bp fragment of the new sequence and that of the published cDNA of DLG5. We identified an ORF with a stop codon preceding it indicating we had obtained the entire coding region of the gene. The complete cDNA sequence has been submitted to Genbank, Accession Number AF352034.

In-Silicon mapping and genomic organisation Of DLG5

The newly generated DLG5 cDNA sequence (7.195 Kb) was subjected to a search for homology to genomic sequences in Genbank using BLASTN algorithm on Search Launcher, available at Molecular Biology Computational Resources (MBCR) server, Baylor College of Medicine (BCM) http://www.mbcr.bcm.tmc.edu. Homologous sequences were identified on BAC 651 c23 (Acc. No. AC013252) and BAC 126h7 (Acc. No. AL391421). The Sequencer 3.1 program was employed to assemble genomic sequences from these BACs and to map the cDNA to these sequences. The genomic sequences for the gene were deposited in GenBank with Accession Number AF352033.

Analysis of patient DNA

Using available genomic sequences, primers were designed to analyze the patient DNA. Primers were anchored in introns and PCR products generated from genomic DNA of patients. PCR was performed with 200 ng genomic DNA, 50 μM each deoxynucleotide triphosphate, 02 μM of forward and reverse primers each and 2.5 units of Taq Polymerase (life Technologies). PCR was done on PE9600 or PE9700 thermocycler. Sequencing reactions were performed using fluorescent labeled Big Dye terminator (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) on a PE9600 thermocycler. Each reaction was then cleaned over the Edge Biosystems column and subsequently sequenced on an ABI310 or ABI377 genetic analyzer. Sequences were assembled using Sequencer 3.1 program.

Use of a novel technique to rule out deletion mutations

We utilized a newly available somatic cell hybrid technique from GMP Genetics, Inc. [9] to obtain haploid cell lines. In brief, this technology provides a means whereby the two homologous chromosomes are separated and isolated into separate cell lines. Our affected patient's diploid leucocytic cell line was converted to haploid somatic cell hybrid lines. The hybrid cell lines were screened to identify those cell lines that contain the chromosome 10 homologues. We further confirmed by genotyping that the DNA of one of these haploid lines had the alleles segregating with the disease. Thus, if a mutation in the DLG5 gene is responsible for the disease it would be in this cell line. We then performed PCR using primers anchored in the introns of DLG5 for each of the exons on both the normal haploid DNA and the disease bearing haploid DNA. The presence of amplification products from both haploid lines would detect any exon deletion that may have eluded detection by PCR from genomic DNA.

Results and discussion

We previously mapped the locus for familial atrial fibrillation to 10q22-24 between markers D10S1694 and D10S1786. In the NCBI database DLG5 had been mapped to 10q22. We subsequently mapped the entire cDNA on to genomic sequences from BACs RPII651C23 & RPII126H7, which also have the marker D10S569 that lies between our flanking markers. Thus DLG5 lies within our critical region at 10q22 within 100 KB of D10s569.

Human tissue expression patterns of DLG5

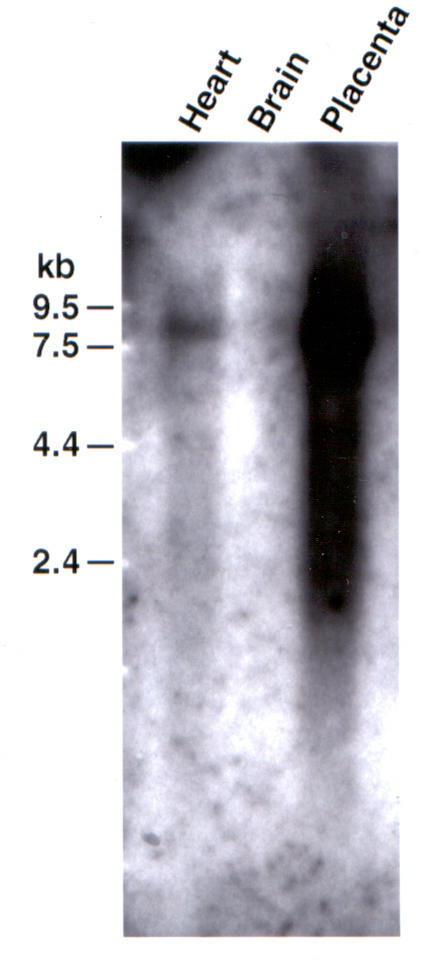

The expression pattern of the DLG5 gene was analyzed in multiple adult human tissues by Northern Blot Analysis using as a probe the ATCC clone #409942 (EST ym59b11) with insert an size of 2.386 Kb which contains exon 31 and 32 with 3' untranslated region of the gene. A twenty-four hour exposure showed abundant expression in placenta with minimal expression in skeletal muscle, liver, kidney and pancreas and no expression in heart (data not shown). Exposure for six days showed expression in heart, no expression in the brain and abundant expression in placenta as shown in Figure 1. We observed a single transcript of approximately 7.2 Kb thus, the published sequence of the cDNA for the DLG5 gene was incomplete.

Figure 1.

Six day exposure of Human Multi Tissue Northern Blot (Clontech Cat. #7760-1) probed with EST ym59b11 (with insert size 2.386 Kb which contains exon 31 and exon 32 (3'UTR) of DLG5) shows a transcript of about 7.2 Kb with expression in the heart, absence of expression in brain and abundant expression in placenta.

Cloning and sequencing of the DLG5 cDNA

On Northern Blot Analysis a single transcript of approximately 7.2 Kb was observed. Using Race Technique on Heart cDNA and heart library screening as described above we characterized the entire cDNA of 7.195 Kb: a 5'UTR from bp 1 to 94, ORF from bp 95–5547 and 3'UTR from bp 5548–7195. The translation start codon of the cDNA is at bp 118 in exon 2 and the stop codon is at bp 5545 in exon 32. As multiple clones were sequenced after RACE, 2 distinct forms were observed: one with a 12 nucleotide deletion in the beginning of exon 4 and the form without the deletion. The deletion did not result in any change in the ORF of the gene.

Search for ESTS homologous to the cDNA

Using Search Launcher available on the Molecular Biology Computational Resources (MBCR) server at Baylor College of Medicine (BCM) http://www.mbcr.bcm.tmc.edu homology searches on the new cDNA sequence against DBEST database identified several ESTs, {Acc. #BF357671 and Acc. #bf336740} which overlap each other and match the new cDNA

Determining the intron exon boundaries of DLG5

We mapped 31 exons (2–32) of the 7.195 Kb of the cDNA to a genomic region spanning about 79 Kb. We could not map 1–94 bp (5'UTR) on to the genomic region. This may be because none of these BACs are completely sequenced in Genbank and there are still gaps in the genomic sequencing. Attempts at direct BAC walking to place these nucleotides were unsuccessful, perhaps because these regions of genomic DNA are difficult to sequence due to its secondary structure. The details of the genomic organization of the gene are shown in Table 1 and Figure 2. All but two of the resulting intron-exon boundaries concur with the typical splice donor and acceptor motif-GT/AG. The sequences around each splice site are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Position of the DLG5 exons within the cDNA sequence

| EXON | START BASE | END BASE | LENGTH (bp) |

| 2 | 95 | 159 | 67 |

| 3 | 160 | 325 | 163 |

| 4 | 326 | 468 | 144 |

| 5 | 375 | 560 | 184 |

| 6 | 561 | 816 | 260 |

| 7 | 817 | 1131 | 312 |

| 8 | 1132 | 1315 | 185 |

| 9 | 1316 | 1442 | 126 |

| 10 | 1443 | 1576 | 133 |

| 11 | 1577 | 1703 | 128 |

| 12 | 1704 | 1879 | 176 |

| 13 | 1880 | 1983 | 104 |

| 14 | 1984 | 2076 | 93 |

| 15 | 2077 | 3096 | 1020 |

| 16 | 3097 | 3220 | 124 |

| 17 | 3221 | 3365 | 145 |

| 18 | 3366 | 3478 | 113 |

| 19 | 3479 | 3568 | 90 |

| 20 | 3569 | 3719 | 151 |

| 21 | 3720 | 3882 | 163 |

| 22 | 3883 | 4016 | 134 |

| 23 | 4017 | 4157 | 141 |

| 24 | 4158 | 4341 | 184 |

| 25 | 4342 | 4490 | 149 |

| 26 | 4491 | 4661 | 171 |

| 27 | 4662 | 4858 | 197 |

| 28 | 4859 | 5002 | 144 |

| 29 | 5003 | 5130 | 128 |

| 30 | 5131 | 5240 | 110 |

| 31 | 5241 | 5350 | 110 |

| 32 | 5351 | 7101 | 1751 |

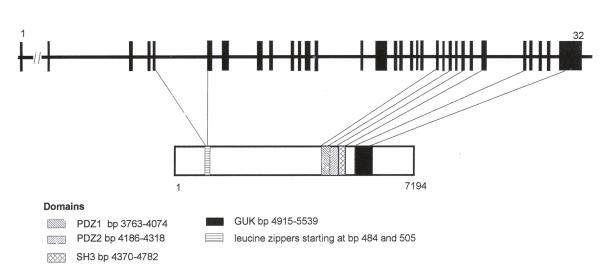

Figure 2.

Genomic organization of the gene DLG5 with 32 exons spliced over 79 Kb region. The protein domains are shown with reference to the exons. Domains not shown here are Regulator of Chromosomal Condensation (RCC1) starting at bp 4333 and the CAAX domain at bp 5536–5545 of the cDNA.

Table 2.

Sequence of the intron-exon junctions*

| Intron | Size (bp) | 5' splice donor | 3' splice acceptor |

| 2 | 12236 | AGCAGTGTGG/gtgagtacca | ccttccacag/GCACTACCGG |

| 3 | 2359 | TTGACAAGAG/gtagtaattgg | tctgggccag/GCCCTACCAC |

| 4 | 689 | ACTTCTACCA/gtgagtgagg | ggtgtttcag/CACACTCCAC |

| 5 | 9647 | CCAGCAGCAG/gtaggcccag | ctgtctccag/GTGTTGAAGC |

| 6 | 1254 | CCCTGAGGAG/gtagggctag | tcttgccagg/TTTGAGGCG |

| 7 | 5958 | GCTGCGGCAG/gtaggtgggt | ctcccaccag/ATCAAAGACA |

| 8 | 1698 | ACAGCATCCG/gtatggggt | cttccaccag/GACACTGTG |

| 9 | 3040 | AGGAGCTCAA/gtaggctcgg | ctgttcacag/GGACACTGTG |

| 10 | 396 | GAGGGAGACG/gtaagctgcct | gtttttgcag/GAGGATATTG |

| 11 | 686 | GCCGCTTAAG/gtaagagttg | cctttctcag/GGTCAATGAC |

| 12 | 369 | GGACAGAAAG/gtagcgggcc | tggcttgcag/ACAGTGGCAT |

| 13 | 4404 | GATCGTTGCG/gtaagtctca | cctgctctag/ATCAATGGCA |

| 14 | 2282 | CCTCCTGAAG/gtaagggctg | ccctgcctag/GTATTCCCTC |

| 15 | 1064 | GTTCCTGGAG/gtatagctga | gcatctgcag/GAACAGAAGT |

| 16 | 429 | CCGTCTGTGG/gtgagtcagc | ccatttctag/GTACTGTTCC |

| 17 | 1431 | TGCATCCCAG/gtatgtgaag | ttttacgcag/TGTCCAGCAC |

| 18 | 680 | GCCCGCCTGG/gtaactgcac | ggaacaatag/GTTCTTCGAG |

| 19 | 305 | TCCGAGAGAG/gtaaggactt | ctctctgcag/GTTCAGTGTC |

| 20 | 4187 | GAAAGGACAG/gtgagcatgg | ttttccttag/GCCTTATGTG |

| 21 | 157 | GTTACTGGAG/gtgagaggga | gtttccccag/TTCAACGGCA |

| 22 | 689 | CCCGGTCCAG/gtgagtgcgg | ccgcctccag/CTCACACCTG |

| 23 | 1363 | GCAGCTCCAG/gtcagcagac | ttcctgaaag/GATTGCGGGA |

| 24 | 1602 | CATCCTGGAG/gtgagttctg | tccctggcag/TATGGCAGCC |

| 25 | 867 | TCTACATCAG/gtaccagtgg | tgtggtccag/GGCCCTGTAC |

| 26 | 896 | GCAAATATGT/gtaagtgttc | tgtgccacag/GATGGACCAA |

| 27 | 9070 | CTCTTTGAAG/gcaagtggct | tctccctcag/ATTCGGTGAG |

| 28 | 262 | TGTCCCCTTG/gtaaggggca | tg cattg cag/AG GTGATGAA |

| 29 | 1102 | CACAGAAAAG/gtacccaggg | cccaccccag/AACCGACACT |

| 30 | 731 | AGCACATCAA/gtaggtaact | gtccccacag/GGAGCAGAGA |

| 31 | 1464 | TACTTCACAG/gtaggtgtgc | tcttttgcag/GGGTCATCCA |

*The capital letters represent exon sequence, the lower case letter the intron sequence

Determining the functional domains in DLG50

The MAGUK family of proteins [2,10] have characteristic domains which are present in DLG5: PDZ1 at bp 3763–4074, PDZ 2 domain 4186–4518 bp, SH3 domain bp 4570–4782 and the GUK domain at bp 4915–5539 (Figure 2).

Several domains were identified in the novel cDNA using MOTIF at SEQ WEB. A single repeat unit of the Regulator of Chromosomal Chromatin (RCC1) domain was detected starting at bp 4333. RCC1 is a eukaryotic protein that has seven tandem repeats units which comprise a domain of 50–60 amino acids. This domain binds to chromatin and interacts with Ran, a nuclear GTP-binding protein that stimulates a guanine nucleotide dissociation. Thus, RCC1 probably plays a role as a gene regulator. Only one repeat unit is present in DLG5 which makes it difficult to predict whether it also has such gene regulating function.

A prenyl group-binding site (CAAX box) was also detected starting at 5536 bp. A number of proteins are post translationally modified by the attachment of either a fresnyl or a geranyl-geranyl group to a cysteine residue. This modification occurs on a cysteine residue, three residues proximal to the C-terminus with two aliphatic amino acids separating the cysteine from the C-terminus (hence the term CAAX box). Certain proteins such as Ras proteins and the Ras-like protein Rho, nuclear lamins A and B and some G protein alpha subunits have this modification. These proteins are involved in intracellular signal transduction. This is another mechanism by which DLG5 may be involved in intracellular signal transduction. In addition to these domains there are two leucine zippers starting at base pairs 484 and 505 suggesting protein-protein interaction.

Exclusion of DLG50 as a candidate for familial atrial fibrillation in our family

The exons and flanking intronic sequences of DLG50 were amplified by PCR and sequenced in four members of the family, two affected and two normals. There were no missense or nonsense mutations segregating with the disease in either the coding regions or splice junctions of this gene. To exclude a large deletion that might have eluded amplification from diploid DNA by PCR sequencing was performed on the haploid cell lines and no mutation was identified. Thus, DLG50 is excluded as a possible cause of familial atrial fibrillation in these families.

Utilizing the available partial cDNA sequence, we confirmed the localization of DLG5 to the locus for atrial fibrillation at 10q22 and subsequently cloned and sequenced the DLG5 gene which spanned 79 KB. The available 5.5 KB cDNA sequence was extended by RACE and confirmed on northern analysis to be about 7.2 KB. The genomic structure of the DLG5 was determined to consist of 32 exons and shown to have ubiquitous human tissue expression including placenta, heart, skeletal muscle, liver and pancreas, with placenta being the tissue of strongest expression. Exclusion of a deletion from the haploid cell lines confirmed the absence of any mutation and thus, DLG5 was excluded as a cause for the atrial fibrillation in these families. Two distinct transcripts of DLG5 were observed differing by only 12 bp, which would predict the addition (or deletion) of 4 amino acids, but would not alter the translation frame of the gene.

The DLG5 gene encodes for a protein that is a member of the MAGUK (Membrane Associated Guan late Kinase homologs) family of proteins located in the plasma membrane [2]. MAGUK is a new family of proteins that act as a molecular scaffold for intracellular signaling pathways [11]. The MAGUK family of proteins is characterized by domains that interact with other proteins to create an assembly of large multi-protein complexes [10]. The PDZ (PSD-95, DLG and ZO-1) domains are the best characterized for their binding to the C-terminal region of channels and transmembrane proteins [11]. Usually each protein has 1–3 copies of such domains [8,12,13]. The SH3 domain (Src homology 3) are present in proteins that couple transmembrane receptors to signaling molecules [14]. The presence of this domain in MAGUKs increases their possibilities of interacting with signaling pathways. The GUK domain shows a high degree of similarity to guanylate kinase enzyme, which converts GMP to GDP using ATP as a phosphate donor. The dlg-like MAGUKs do not have kinase activity [15]. Furthermore this domain has been shown to interact with other proteins [16-18]. MAGUKs function by binding to the transmembrane proteins at the cytoplasmic side and to other signal transduction proteins and thus appear to provide the platform for efficient and specific signal interactions between the different components of the signaling pathway. Acting as scaffold proteins, these proteins play a pivotal role in creating an efficient signaling pathway by localizing the signaling molecules at regions of cell surface preferentially exposed to the ligand, and by spatially restricting the molecules to provide specific downstream responses.

The DLG5 gene encodes for 2 PDZ domains, with another region in the N-terminus having very weak homology to an additional two PDZ domains. It is notable that the PDZ domains predicted for the DLG5 protein do not have the GLGF motif [2], present in most members of the MAGUK family. This motif helps in the binding of the MAGUK with the C-terminus of proteins that have the consensus E (S/T) × (V/l) motif [19]. However the studies on the Drosophila protein InaD, which also has a PDZ domain, show that are other targets for the PDZ domain that do not have the consensus C-terminus binding motif [20]. Thus in DLG5 the PDZ domain may be binding to other targets that do not require the classic GLGF motif for interaction. Like other members of this family DLG5 also has one SH3 and GUK domain. In addition it has two leucine zippers and an RCC1 domain that represents other potential protein-protein interactions.

Previously reported MAGUKs have been studied for these interactions, and elegant work has shown one of its members, p55, to form a ternary complex that links the cytoskeleton and the plasma membrane to maintain proper cell shape [3]. Also there is significant evidence that MAGUKs are active in protein clustering especially of ion channels and membrane bound receptors [6]. This interaction has been proven by experiments in which DLG5 mutants show loss of clustering of the Shaker channels at neuromuscular junction [6]. Mammalian PSD-95 is a MAGUK which binds Kir4.1, an inwardly rectifying K+ channel expressed in glial cells and also clusters it to cell membranes in vitro [21]. Thus MAGUKs may regulate the distribution and also the function of transmembrane receptors and channels.

Conclusions

Given these observations, its pattern of expression in the human adult heart, we considered it to be an excellent candidate for the familial atrial fibrillation and evaluated it in our family by sequencing. We have ruled out functional mutation in the coding region and splice junction as well as any exon deletion as possible cause of the disease in this family. This gene remains an interesting candidate for other inherited cardiac diseases.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

We greatly appreciate the secretarial assistance of Moira Long and Debbie Graustein in the preparation of this manuscript and figures. This work is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health Specialized Center of Research in Heart Failure (HL54313-07) and the National Institutes of Health Training Center in Molecular Cardiology (T32-HL07706). This work was funded by a grant from the Human Genome Project.

Contributor Information

Gopi Shah, Email: gshah@bcm.tmc.edu.

Ramon Brugada, Email: rbrugada@bcm.tmc.edu.

Oscar Gonzalez, Email: oscarg@bcm.tmc.edu.

Grazyna Czernuszewicz, Email: graznac@bcm.tmc.edu.

Richard A Gibbs, Email: agibbs@bcm.tmc.edu.

Linda Bachinski, Email: lindab@bcm.tmc.edu.

Robert Roberts, Email: rroberts@bcm.tmc.edu.

References

- Brugada R, Tapscott T, Czernuszewicz GZ, Marian AJ, Iglesias A, Mont L, et al. Identification of a genetic locus for familial atrial fibrillation. N EngI J Med. 1997;336:905–911. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199703273361302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura H, Sudo T, Tsuiki H, Miyake H, Morisaki T, Sasaki J, et al. Identification of a novel human homolog of the Drosophila dlg, P-dlg, specifically expressed in the gland tissues and interacting with p55. Lett. 1998;433:63–67. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)00882-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marfatia SM, Morais Cabral JH, Lin L, Hough C, Bryant PJ, Stolz L, et al. Modular organization of the PDZ domains in the human discs-large protein suggests a mechanism for coupling PDZ domain-binding proteins to ATP and the membrane cytoskeleton. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:753–766. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.3.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas U, Phannavong B, Muller B, Garner CC, Gundelfinger ED. Functional expression of rat synapse-associated proteins SAP97 and SAP102 in Drosophila dlg-1 mutants: effects on tumor suppression and synaptic bouton structure. Mech Dev. 1997;62:161–174. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4773(97)00658-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey T, Gorczyca M, Jia XX, Budnik V. The Drosophila tumor suppressor gene dlg is required for normal synaptic bouton structure. Neuron. 1994;13:823–835. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90249-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tejedor FJ, Bokhan A, Rogero O, Gorczyca M, Zhang J, Kim E, et al. Essential role for dlg in synaptic clustering of Shaker K+ channels in vivo. J Neurosci. 1997;17:152–159. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-01-00152.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornau HC, Schenker LT, Kennedy MB, Seeburg PH. Domain interaction between NMDA receptor subunits and the postsynaptic density protein PSD-95. Science. 1995;269:1737–1740. doi: 10.1126/science.7569905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Niethammer M, Rothschild A, Jan YN, Sheng M. Clustering of Shaker-type K+ channels by interaction with a family of membrane-associated guanylate kinases. Nature. 1995;378:85–88. doi: 10.1038/378085a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos N, Leach FS, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Monoallelic mutation analysis (MAMA) for identifying germline mutations. Nat Genet. 1995;11:99–102. doi: 10.1038/ng0995-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stehle T, Schuiz GE. Refined structure of the complex between guanylate kinase and its substrate GMP at 2.0 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 1992;224:1127–1141. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90474-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitratos SD, Woods DF, Stathakis DG, Bryant PJ. Signaling pathways are focused at specialized regions of the plasma membrane by scaffolding proteins of the MAGUK family. Bioessays. 1999;21:912–921. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199911)21:11<912::AID-BIES3>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitratos SD, Woods DF, Bryant PJ. Camguk, Lin-2, and CASK: novel membrane-associated guanylate kinase homologs that also contain CaM kinase domains. Mech Dev. 1997;63:127–130. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4773(97)00668-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JM. Cell signalling: MAGUK magic. Curr Biol. 1996;6:382–384. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00501-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon MA, Dodson GS, Rubin GM. An SH3-SH2-SH3 protein is required for p21Ras1 activation and binds to sevenless and Sos proteins in vitro. Cell. 1993;73:169–177. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90169-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kistner U, Garner CC, Linial M. Nucleotide binding by the synapse associated protein SAP90. FEBS Lett. 1995;359:159–163. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00030-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi M, Hata Y, Hirao K, Toyoda A, Irie M, Takai Y. SAPAPs. A family of PSD-95/SAP90-associated proteins localized at postsynaptic density. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:11943–11951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.18.11943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh K, Yanai H, Senda T, Kohu K, nakamura T, Okumura N, et al. DAP-1, a novel protein that interacts with the guanylate kinase-like domains of hDLG and PSD-95. Genes Cells. 1997;2:415–424. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1997.1310329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Naisbitt S, Hsueh YP, Rao A, Rothschild A, Craig AM, et al. GKAP, a novel synaptic protein that interacts with the guanylate kinase- like domain of the PSD-95/SAP90 family of channel clustering molecules. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:669–678. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.3.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Songyang Z, Fanning AS, Fu C, Xu J, Marfatia SM, Chishti AH, et al. Recognition of unique carboxyl-terminal motifs by distinct PDZ domains. Science. 1997;275:73–77. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5296.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shieh BH, Zhu MY. Regulation of the TRP Ca2+ channel by INAD in Drosophila photoreceptors. Neuron. 1996;16:991–998. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hono Y, Hibino H, Inanobe A, Yamada M, Ishii M, Tada Y, et al. Clustering and enhanced activity of an inwardly rectifying potassium channel, Kir4.1, by an anchoring protein, PSD-95/SAP90. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:12885–12888. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.20.12885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]