Abstract

Community-engaged approaches to research can increase trust, enhance the relevance and use of research, address issues of equity and justice, and increase community knowledge and capacity. The HERCULES Exposome Research Center sought to engage local Atlanta communities to learn about and address their self-identified environmental health concerns. To do this, HERCULES and their stakeholder partners collaboratively developed a community grant program. The program was evaluated using mixed qualitative methods that included document review and semi-structured interviews. This paper presents the development, implementation, and evaluation of the grant program. HERCULES awarded one-year grants of $2,500 to 12 organizations within the Atlanta region, for a total 13 grants and $32,500 in funding. Grantees reported accomplishments related to community knowledge, awareness, and engagement in addition to material accomplishments. All grantees planned to sustain their programs, and some received additional funding to do so. Some grantees remained actively involved with HERCULES beyond the grant program. The HERCULES Community Grant Program was able to increase awareness of HERCULES among applicant communities, establish or enhance relationships with community-based organizations, and identify local environmental health concerns while providing tangible results for grantees and the communities they serve. Mini-grant programs are a feasible approach to address community environmental health and establish new relationships. This model may benefit others who aim to establish community-academic relationships while addressing community health concerns.

Keywords: environmental health, mini-grant, community engagement, community-academic partnerships, community health

Introduction

This article describes the implementation process and evaluation outcomes of a community grant program, which is a model for community engagement. The practical aim of this article is to share the process and outcomes of this program so that other researchers, academic centres, and agency professionals seeking to strengthen their community engagement efforts may replicate and adapt this community grant program in their own settings and communities. The academic aims of this article, documented through the evaluation of our community-engagement approach, are to 1) demonstrate the achievements of the program and 2) determine which aspects of the grant program met, or did not meet, community grantees’ needs.

Community-engaged approaches to research have been found to increase trust, enhance the relevance and use of research, address issues of equity and social justice, and increase community knowledge and capacity (Allen et al. 2010; Allen et al. 2011; Cargo and Mercer 2008; Israel et al. 1998; Jagosh et al. 2012; Minkler 2005; Viswanathan et al. 2004). Several federal agencies have acknowledged the value of community engagement and published the “Principles of Community Engagement” to provide guidance to researchers and community members in their collaborative efforts (CTSAC 2011). The Community-Campus Partnerships for Health (2018) and the Citizen Science Association (2018) were founded to support public participation in scientific research and to provide a platform for community leadership in science. Given the potential benefits of CE to science and the partnering community, there is a need to document community-engagement approaches and their outcomes.

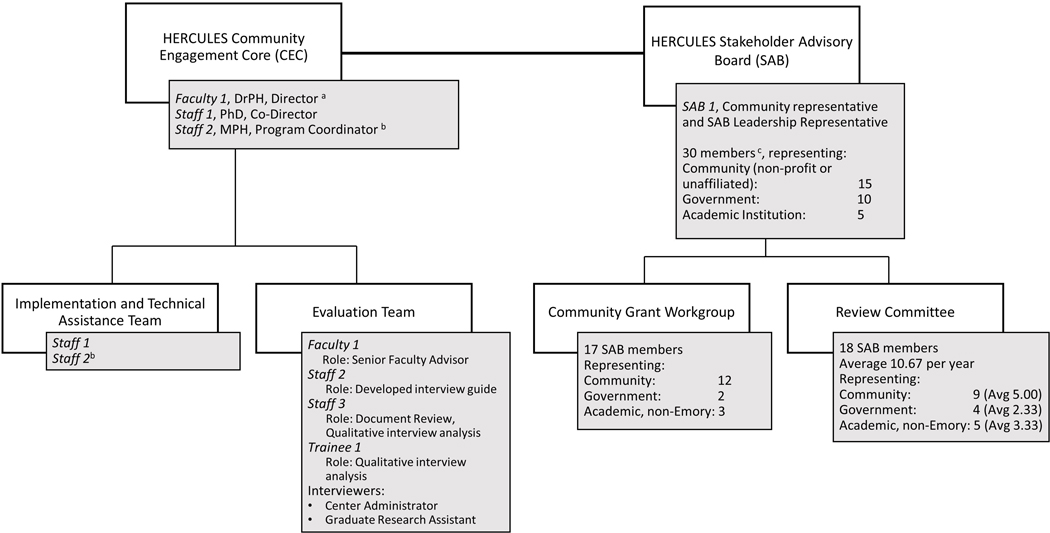

The HERCULES Exposome Research Center (HERCULES) is an environmental health science core centre at Emory University that was established in 2013 and funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS). As a core centre, HERCULES does not have its own research projects, but provides infrastructure for environmental health science at Emory. The Community Engagement Core (CEC) is one of five cores integral to HERCULES. When developing the centre, involved faculty and staff convened a Stakeholder Advisory Board (SAB) to guide the centre’s community engagement efforts and inform the centre itself. The SAB consists of approximately 25–30 active members, including community leaders, neighbourhood residents, non-profit organizations, government agencies (local, state, and federal), and other local academic institutions (See Figure 1). The SAB oversees the centre’s community engagement activities and engages with HERCULES scientists in an effort to integrate community concerns into science. Together, the CEC and SAB are committed to developing multi-directional communication with metro-Atlanta communities to understand and address their environmental health and exposome-related concerns. The exposome is a measure of cumulative environmental influences and associated biological responses throughout the lifespan, including exposures from the environment, diet, behaviour, and endogenous processes (Miller and Jones 2014, 2). This holistic perspective on environmental influences is relatively new to the field of environmental health sciences yet relevant to the daily lived experience of communities in Atlanta. Atlanta is a majority Black city (U.S. Census 2017) that was recently rated as having the worst income inequality in the United States (Berube 2018). Clear disparities exist in the Atlanta region by geography and race; Black residents in the region have a median household income that is 35% less than White residents (Bellows 2019) and are more likely to live in the southern and western parts of the metro area (ARC Research 2019). These regions also have the lowest life expectancy and higher rates of poverty, unemployment, and chronic health conditions (ARC Research 2019). As such, this is an important time and place to integrate community knowledge into exposome science.

Figure 1.

Sheheed DuBois Community Grant Program Organization Chart

a The CEC Director is a faculty member in Behavioural Sciences and contributed expertise in planning, implementing and evaluating community grant programs.

b Replaced by Staff 3 MPH staff member in Behavioural Sciences, in Year 3 of the Grant Program.

c Membership slightly varied over the program years, numbers shown are from 2016.

In 2013, as a new Center, the HERCULES CEC, led by co-authors Kegler and Pearson, and the SAB (see Figure 1), sought to move beyond community outreach approaches that view community members as passive recipients of research findings and instead considered CE approaches to build additional relationships with local Atlanta communities and learn about and support them as they address their environmental health concerns. Together, the CEC and SAB considered several approaches, including community-based participatory research (CBPR) pilot projects, seed money for community-academic partnerships, community forums, photovoice projects, and citizen science. Several of these strategies, when implemented by other academic centres, involved providing grant funding to community partners. Because the HERCULES CEC does not provide direct research benefit to communities, the SAB liked the idea of providing funding directly to communities to address their concerns. Grant programs they reviewed varied in funding amount (anywhere from $1000 to $30,000) and in purpose (Jacob Arriola et al. 2015; Deacon et al. 2009; Johnson et al. 2006; Kegler et al. 2016; Kegler et al. 2015; Honeycutt et al. 2012; Teufel-Shone et al., 2019; Thompson et al. 2010; Tendulkar et al. 2011; Main et al. 2012). Many use pilot or seed funding to establish or strengthen partnerships between researchers and community partners (Kegler et al. 2016; Main et al. 2012; Tendulkar et al. 2011; Teufel-Shone et al., 2019). Other community grant programs are used to disseminate evidence-based interventions, funding communities to implement specific programs or strategies (Jacob Arriola et al. 2015; Kegler et al. 2015; Honeycutt et al. 2012), while others are used to involve communities in ongoing work (Deacon et al. 2009; Johnson et al. 2006).

Given that HERCULES does not conduct its own research, has a different mechanism that prioritizes funding for community-driven research projects (HERCULES Research Pilot Grants (2018)) and does not develop or disseminate specific public health interventions, the HERCULES CEC and SAB collaboratively developed another type of community grant program. A subset of SAB members volunteered to participate in a workgroup to develop details of the grant program, reporting progress and making final decisions with the full SAB (See Figure 1). SAB members representing their community receive financial incentive for their participation in all SAB meetings (full, workgroup, and review meetings). The final HERCULES community grant program directly funded local community-based organizations in the Atlanta-area (determined by the SAB to be the 10-county Atlanta region as defined by the Atlanta Regional Commission (2018)) to identify and implement their own solutions to self-identified environmental health concerns, with the goal of learning about those concerns and establishing a relationship with the community while enhancing their capacity. This approach also had the potential to raise community awareness of HERCULES, an important initial step for a new centre.

Given the proven potential for community-engaged research to improve outcomes, we are sharing this grant model as a specific approach to community engagement that may benefit other researchers, academic centres, and agency professionals who, like HERCULES, aim to establish relationships with the community while increasing community capacity to identify and address their health concerns. In fact, since sharing program information within the NIEHS Core Centres Network, two other centres have replicated the program. To that end, this paper shares the implementation process and selected evaluation results from the HERCULES community grant program, named the “Shaheed DuBois Community Grant Program” in memory of a dedicated SAB member who was critical to the development and implementation of the program. We first describe the development and implementation details, which include the application, review, funding, and technical assistance processes. We then present the evaluation results, which demonstrate what a community grant program may achieve, including program reach, types of projects, accomplishments, lessons learned, project sustainability, and areas to consider for improvement. Finally, based on the experience of our grant program in relation to other similar programs, we conclude with recommendations for other researchers, academic centres, and agency professionals. The main benefit of sharing this model for community engagement is to minimize barriers and facilitate the use of similar community-engaged approaches that go beyond traditional outreach and provide tangible results for communities.

Materials and Methods

Description of the community grant program

HERCULES launched the Shaheed DuBois Community Grant Program in January 2014. The purpose and major components of the grant program are described in Table 1. The HERCULES CEC and the SAB adapted the program from similar programs at Emory University (the Atlanta Clinical Translational Science Initiative (Kegler et al. 2016)) and the Emory Prevention Research Center (Honeycutt et al. 2012; Jacob Arriola et al. 2015; Kegler et al. 2015)) with guidance from the CEC Director, co-author Kegler, a senior faculty member with experience in community grant programs. In addition to the broad goals of supporting communities to address their environmental health concerns and developing relationships with the local community, the SAB workgroup chose to support smaller organizations with lower capacity such as neighbourhood-level grassroots organizations with minimal staff. This is reflected in the $2500 grant amount chosen by the SAB, which SAB members representing small organizations thought could provide significant benefits to a small, neighbourhood-level organization. It is also reflected in the grant requirements, such as progress reports, which were co-developed by the CEC and SAB workgroup to both provide practical experience with grant skills while minimizing burden on smaller organizations. HERCULES CEC personnel implemented all program elements according to decisions and guidance from the SAB.

Table 1.

Major components of the grant announcement and application

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

| Purpose as stated in Funding Announcement |

The HERCULES Community Grants Program provides funding to organizations that aim to conduct outreach, promote community awareness of local environmental health concerns, or collect information needed to address local environmental health concerns in the 10-county Atlanta region. |

| Eligibility | • Located in or serve the 10-county Atlanta region • 501c(3) status or a fiscal agent with this status |

| Funding | $2,500 |

| Funding Period | One year (12 months) |

| Proposal Elements | Project and Community Description • Environmental health focus of the project a • Why the selected topic is an environmental health concern for the community b • Community description and how the project will meet the identified community need Strategies and Activities • Detailed plan of the proposed activities and events plus any barriers and how they will be addressed • Proposed 12-month timeline c Experience and Capacity • The Organization: organizational structure, resources available, leadership support b • Experience: organization’s past experience in addressing related community concerns • Staffing: Project coordinator(s), relevant experience, key staff members or volunteers who will be involved with the project, how needed expertise will be obtained b Budget and justification • Estimated budget not to exceed $2500 |

| Selection Criteria | • Description of community’s environmental health concern d • Description of target population & community need for project (15 points total) • Realistic strategies and activities that are connected to topic and community needs (25 points total) • Realistic timeline for completion and reasonable budget (15 points) • Organizational experience, time commitment, and leadership to conduct project. (10 points) • Overall impact - reviewer’s assessment of the likelihood for the project to have impact and address environmental health concerns in the stated community (10 points total) |

Changed from open-ended to a check box list in Years 2 and 3.

Included in the Year 1 application only.

A table with columns for dates and activities was added in Years 2 & 3.

Scored in Year 1 applications only.

Application Process

The application form included common grant application elements (see Table 1) that were simplified into a short-answer format appropriate for lower capacity organizations with minimal staff and grant writing experience. The CEC and SAB members distributed the Funding Opportunity Announcement (FOA) through their existing organizational communication channels and community networks, at in-person community events, and via email to attendees of an environmental health community forum organized by the CEC and SAB. Additionally, we equitably distributed the FOA to the target funding area through Neighbourhood Planning Units, the metro-wide formal system of neighbourhood level decision making.

The HERCULES CEC and SAB workgroup made small modifications to the application and FOA between grant years to better collect the information reviewers needed to determine if organizations and proposed projects met the goals of the program (See Table 1). In the third year of the program, SAB members expressed concern that smaller organizations were at a disadvantage relative to larger or higher capacity organizations so an in-person grant writing workshop was offered six weeks prior to the application due date and made available online. In addition, CEC personnel pre-reviewed submitted applications and provided feedback to all applicants with the option of revising and resubmitting their application.

Review Process

SAB members volunteered to participate in the review committee.. CEC personnel coordinated the review and in-person meeting at which reviewers discussed scores and finalized award decisions. The staff assigned two reviewers to each application, one community-based reviewer and one institutional reviewer (governmental or non-Emory academic). No HERCULES or Emory-based faculty or staff scored applications, and members of the review committee disclosed any conflicts of interest prior to reviewing. The HERCULES CEC developed a scoring process and rubric to align with the selection criteria, modelled after that used by the Emory Prevention Research Center (Honeycutt et al. 2012) (Table 1). As part of the decision notifications, CEC compiled and provided reviewer comments for each applicant. All steps in the application and review process were intended to provide transparency and increase the capacity of all applicants, including providing a clear rationale and steps for applying again if not funded.

Funding Process

A fee-for-service agreement between the grantee and Emory University detailed the project activities, reporting and invoicing requirements, and payment structure, and established the grantee organization as a service provider with Emory procurement. Further detail of this payment mechanism can be requested from the lead author.

Technical Assistance

In an effort to enhance the capacity of the grantee organizations to conduct their programmatic activities and program management, the HERCULES CEC provided technical assistance (TA) both systematically and ad hoc (see Figure 1). TA supplemented the grant funding with non-financial assistance such as skills-training and information sharing (e.g., grant skills in program implementation, evaluation, action planning, tracking and reporting progress, creating budgets and invoices, and connecting grantees to available resources, partners, and expertise). Structured TA is described below, during which the CEC identified opportunities for ad hoc TA.

TA process prior to initiating project.

Pre-application call/workshop.

In Years 1 and 2, the CEC hosted a pre-application call to briefly describe the exposome, the HERCULES mission, the goals of the grant program, elements of the application, and to answer questions from potential applicants. In Year 3, the call was replaced with a grant writing workshop that expanded upon the above content and stepped potential applicants through each element of the application.

Grantee presentations:

At the beginning of the grant period, grantees presented their planned project to the HERCULES SAB, who gave feedback and suggestions on their project activities, their evaluation plans, potential challenges/barriers, and resources available in the community.

HERCULES CEC site visits with each grantee.

Site visits varied from grantee to grantee; for some, it served as a planning meeting between CEC staff and the grantee, for others, CEC staff observed a grantee event. This initial site visit provided a mechanism for the CEC to provide TA and identify additional areas for future TA.

Invoices.

As part of the payment terms, grantees submitted invoices for their planned expenses. For many of the grantees, this was their first experience creating an invoice and tracking program expenses, so the CEC provided a sample invoice with possible expense items based on the grantee’s proposed project timeline and proposed budget.

TA process during grant period

Progress Reports.

Grantees submitted progress reports to document their activities and outcomes, which the CEC assessed for TA needs. In Year 1, grantees submitted quarterly progress reports; however, to reduce the burden on grantees, the SAB workgroup and CEC decided to change to a mid-year and final report in Years 2 and 3. Like the application, the CEC and SAB workgroup developed a a progress report form with elements common to many grant programs yet simplified into a short-answer format appropriate for organizations with modest capacity and minimal programmatic experience. The one-page template asked for a description of project activities to-date, project successes, any challenges or barriers encountered, and if any TA from Emory staff was needed.

Grantee presentations.

At the end of each grant cycle, grantees presented their project outcomes to the HERCULES SAB. These final presentations served to recognize the grantees’ accomplishments, identify potential future partners and/or resources, and explore next steps.

Evaluation Methods

The purpose of our evaluation was to determine what the grant program achieved and how, to report those results back to the SAB and funders, and for program improvement and dissemination. To explore various aspects and possible outcomes of the grant program within real-world contexts, we conducted a multiple case study with each participating grantee organization to evaluate the grant program(Yin, 2017). We used mixed qualitative methods to assess 1) who the grant program reached, 2) what environmental health concerns Atlanta-area communities have, 3) what grantees were able to accomplish with $2500, 4) what lessons they learned from implementing their projects, 5) how (and if) they planned to sustain their projects, and 6) how aspects of the grant program met, or didn’t meet, their needs. Qualitative methods included document review and semi-structured interviews with a point of contact from each grantee organization. The CEC planned the evaluation with input from the SAB, and the CEC evaluation team carried out the evaluation (See Figure 1). The SAB workgroup was involved in utilizing interim evaluation results to shape the program and the evaluation. The Emory University Institutional Review Board determined that the evaluation did not require IRB review.

Reviewed documents included the grant application, progress reports, and final report. Trained staff not previously involved in the grant program (See Figure 1) conducted semi-structured interviews within 2 months of project completion using a standardized interview guide adapted from a previous evaluation of a Technical Assistance program (Kegler and Redmon 2006). Interview topics included capacity building, community impact and partnerships, grant administration and technical assistance, and funding and project sustainability. Interviews averaged 30 minutes in length, were audio recorded, and transcribed verbatim. The CEC modified the interview guide each year to reflect feedback from previous interviews, such as minor edits needed to clarify certain questions.

To assess who the program reached and what their environmental health concerns were, the CEC evaluation team analysed grant applications for grantee and project characteristics, such as organization size, geographic location and project topic, and conducted content analysis of progress and final reports to identify accomplishments, challenges, and plans for sustainability. The initial codebook included the topics covered in the interview guide, and then evaluation team members individually reviewed one transcript to identify additional codes to include. Team members discussed their findings, collaboratively revised the codebook, and coded the first transcript to ensure consistency in coding. Two members of the evaluation team independently coded the additional transcripts and resolved all discrepancies through discussion. NVivo qualitative analysis software was used for data management and analysis (QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 11, 2015). After all coding discrepancies were resolved, the evaluation team generated reports for all codes and conducted a second round of inductive coding, identifying themes and subthemes within each code, and organizing themes by transcript into matrices to ensure trustworthiness of the results (Miles, Huberman, and Saldana 2014). The matrices listed each grantee as a column and each potential theme as a row, thus allowing for an assessment of patterns across cases and also providing an audit trail (Miles, Huberman, and Saldana 2014; Yin, 2017).

Results

Grantee Characteristics: Reach and Environmental Health Concerns

Twelve distinct organizations received thirteen grants of $2500 each over three years (2014 – 2016), for a total of $32,500 in grant funding. Document review revealed that funded organizations were from six distinct geographic sectors within two counties of the Metro-Atlanta region, with half of them located in historically disinvested areas of West or Southwest Atlanta (see Table 2). Grantee organizations tended to have smaller staff numbers and rely largely on volunteers (see Table 2). Organizations varied, with the smallest having no staff and eight volunteer board members to the largest having 15 staff and 200 volunteers. The projects addressed topics varying from pollution to social stressors and the built environment. The most common grant topics included healthy food access, water pollution, and waste disposal/illegal dumping (see Table 3). Table 2 provides details about each grantee and the project they pursued.

Table 2.

Shaheed DuBois Community Grant Program: Grantee and Project Descriptions

| Yr | Grantee ID | Location | # of Staff | # of Volunteers or Members | Community Need | Project Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.1 | West Atlanta | 1 | 30 | · Local Creek suffers from high pollution levels. · Current redevelopment plans lack community engagement. |

· Identify and document adverse environmental and public health hazards in local watershed through photovoice and participatory mapping |

| 1 | 1.2 | Metro-Atlanta/SW Atlanta | 0 | 600 | · Neighborhood farm and community garden impacted by soil contamination and polluted watershed. · Atlanta’s 10,000 nightly homeless residents lack access to fresh fruit and vegetables. |

· Improve soil health and production through composting, cover crops, and bio remediation · Create stream buffers to protect watershed · Plant fruit trees to improve soil, prevent erosion and flooding, and increase access to fresh fruit |

| 1 | 1.3 | Dekalb County | 5 | 15 | · Large increase in Atlanta’s refugee population · US farming techniques are new to otherwise experienced farmers. |

· Develop promotional program to raise awareness of farmer training program and support services · Conduct a culturally and linguistically appropriate education and training program |

| 1 | 1.4 | Clarkston, GA | 3 | 13 | · High rates of heart disease and stroke among Georgia’s black population · High rates of poverty and lack of access to affordable quality healthcare |

· Conduct a workshop on the effects of secondhand smoke and cumulative exposures · Train Community Health Advocates to disseminate smoke-free home information to other households |

| 2 | 2.1 | Decatur, GA | 6 | 250 | · Senior public housing residents are 90% African American, half use SNAP benefits · Public housing garden not maintained, low production, lack of programming, resident knowledge and skills |

· Improve garden at senior public housing community via soil amendments, organic pest controls, and a worm composting system · Coach seniors about best growing practices |

| 2 | 2.2 | West Atlanta | 7 | 52 | · Community garden located in USDA designated food desert. Expense, access, and knowledge reported as barriers to eating healthy and living a healthy lifestyle. | · Increase production of healthy foods and opportunities for community engagement by adding raised beds to existing garden |

| 2 | 2.3 | SW and West Atlanta | 4 | 2 | · Inner city area and watershed facing abandoned and dilapidated properties, illegal dumping, pervasive flooding, high bacteria levels, combined sewer and sanitation overflows, and soil erosion | · Implement education and awareness campaign to empower residents and institutions as creek stewards |

| 2 | 2.4a | Clarkston, GA | 5 | 3 | · Condominium community with primarily African American and immigrant residents with low levels of education and income · Improper disposal of used tires, cleaning materials and automobile fluids |

· Provide knowledge to identify, handle, and properly dispose of chemicals and illegally dumped items · Mobilize residents for clean-up day campaign |

| 3 | 3.1 a | Clarkston, GA | 3 | 2 | · See need reported by Grantee 2.4 · Previous project was unable to reach all residents who requested training |

· Training and awareness campaign about illegal dumping, hazardous waste, and environmental health · Clean-up events with residents, management, and county officials |

| 3 | 3.2 | NW Atlanta | 0 | 40 | · Park in a local watershed, in a neighborhood that is 93% African American, with high rates of under/unemployment, illegal drug use, high school drop outs, crime, and vandalism (also at park). | · Engage youth as park stewards to deter them from vandalism, etc. · Organize clean-up events to remove tires from creek, dispose of trash, and mulch trees |

| 3 | 3.3 | West Atlanta | 0 | 9 | · Targeted neighborhoods have median income of $22,300, high rates of unemployment, 80% of children receive free/reduced lunch · Community Benefits Plan recommended urban farming as neighborhood revitalization strategy |

· Increase community cohesion, vitality, and resilience through food · Families will have home garden or community garden plot at garden hub · Includes a garden coach and gathering at the hub · Excess produce sold at hub |

| 3 | 3.4 | North Atlanta | 0 | 8 | · Fork of local creek overgrown, inaccessible, used for illegal dumping · Area covers 12.3 miles and crosses multiple jurisdictions, complicating coordination and partnerships |

· Increase knowledge of the waterway and potential greenway by engaging officials, residents, and businesses via presentations/education, meetings/facilitation, community outreach & marketing, board/organizational development |

| 3 | 3.5 | SW and West Atlanta | 15 | 200 | · USDA designated food desert where residents also report time and expense as barriers to healthier living. · Community suffers high rates of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and obesity |

· Install fruit tree orchard at community center · Include orchard in existing gardening and nutrition education with youth and seniors at the center |

This grantee was awarded a Community Grant in two consecutive years

Table 3:

Health Topics Addressed and Accomplishments Achieved by Grantees

| Health Topics Addressed in Grant Application | Number of grantees (n=13) |

|---|---|

| Healthy Food Access | 6 |

| Water Pollution | 5 |

| Waste Disposal / Illegal Dumping | 5 |

| Built Environment | 3 |

| Soil Contamination | 3 |

| Cumulative Exposures / Multiple Risks | 3 |

| Air Pollution (indoor and outdoor) | 3 |

| Abandoned Buildings / Sites | 2 |

| Chemicals in the Home | 2 |

| Alternative Transportation | 1 |

| Lifetime Exposures | 1 |

| Industrial Sites | 0 |

| Other a | 6 |

| Project Accomplishments as Reported in Progress Reports | Number of grantees (n=13) |

| Community knowledge, awareness, and involvement | 13 |

| Community members participated in trainings/workshops | 9 |

| Attracted new volunteers/participants | 4 |

| Increased community knowledge and skills | 4 |

| Community members took on leadership role | 3 |

| Increased community awareness | 3 |

| Community members organized to remove neighborhood waste | 3 |

| Community youth engaged | 3 |

| Other b | |

| Material accomplishments (all food related) | 5 |

| Improved garden/farm c | 5 |

| Increased vegetable production (and consumption) | 4 |

| Fresh produce provided (donated or sold) to the community | 4 |

| Participants made or saved money by growing and/or selling produce for themselves and others | 2 |

| Challenges | |

| Population-specific factors | 6 |

| Organizational capacity | 6 |

| Environmental factors | 4 |

| Site-specific | 4 |

| Community engagement and participation | 3 |

| Local government | 2 |

Other topics included: Poverty & unemployment, economic opportunities, secondhand smoke, nutrition education, community empowerment, underserved populations

Other accomplishments reported by two or fewer grantees: hosted community and/or volunteer events, held and attended meetings with influential stakeholders, improved organizational structure (e.g., board structure, strategic plan), received project approval from local municipality, aligned project with environmental health, community members informed development priorities or identified concerns and priorities, or lack of accomplishments due to limited funding

Includes soil improvements, new beds, planting seeds or trees, and other infrastructure

Accomplishments

Grantees reported project accomplishments in their progress reports and expanded upon them in semi-structured interviews. All grantees reported accomplishments related to community knowledge, awareness, and involvement. For example, most grantees reported that community members participated in trainings or workshops, such as one grantee who hosted 43 classes, 3 field trips, and 2 garden visits a week. A third of the grantees reported that they attracted new volunteers or participants and increased community knowledge and/or skills. For example, one grantee organized over 50 volunteer events that attracted over 300 unique volunteers, while another trained 20 community members to carry out a door-to-door campaign promoting smoke-free homes that reached 98 households. Another grantee described educating the community and raising awareness about household chemicals:

...people did not know the effects of waste disposal and living with waste and how it affects the environment, the human being, all of this. They did not know that this affects their lives long term. It was very much a mixture of excitement and surprise and very shocking to learn the long-term effects of this.

– Second year grantee

In addition, during interviews grantees described creating opportunities for the community to come together, build community trust, and increase organizational capacity. For example:

For me it would be definitely forming a strong relationship with the residents … with whom we worked with. It felt like [they] really came to trust us and really enjoyed the program and we were able to really get to know them and what they were looking for…- Second year grantee

Another grantee described creating opportunities for local community members to get involved:

I will never forget after we started building the garden, one woman that was a senior citizen came over and asked us what we were doing and said ‘I live in an apartment, and you are the answer to my prayers because I have been praying for something to do, I’m lonely, I used to garden with my grandmother and great grandmother and living in an apartment I have no dirt’ . . . but she started coming every day.

– Second year grantee

Grantees working on food access also reported accomplishments that were material in nature, with almost all of them reporting that they had improved their garden or farm by either making soil improvements, building additional beds, planting seeds or trees, or adding other infrastructure. For example:

Our project included building or planting a fruit tree orchard in that community so that people would have access to fresh fruits, not only immediately, but for years and years to come. So we were able to plant, I think between 12 and 15 trees as a result of the grant.

– Third year grantee

These and other accomplishments are presented in Table 3.

Lessons Learned

During semi-structured interviews, grantees reported that they were able to learn valuable lessons as a result of conducting their community grant project. The grant allowed them to try things out, which enabled them to assess their approach, identify important project components, identify additional needs, and identify challenges.

About half of the grantees talked about confirming or refining their project’s approach. This included things like confirming their organization’s priorities, refining their curriculum, confirming their decision to work with youth (rather than adults), and refining their enrolment process. For example:

We saw a great improvement in the yield on the farm and the health of the soil. Because of this… we really reconfirmed like we want to invest in the soil health and we want to invest in compost and amendments first and foremost… This experience really bumped that to the top of our list of priorities for our farm.

– First year grantee

About half of the grantees also said they identified elements that were critical to the success of their project. These elements varied, and included the importance of spending the time to plan, organize, and engage stakeholders; partnerships; working directly in the community; flexibility; and staffing that is consistent and has appropriate expertise. For example:

So one of the things I’ve learned is really to possess a little more time in checking the boxes, meeting with people, establishing that kind of support up front. The second thing is try to get more of a cross-section of community participants. – Third year grantee

Some grantees also said that the project helped them identify additional needs, of both the community and the organization. For example, one grantee learned the extent of the need for education in the community and used that to apply for additional funding.

Grantees also reported challenges in both their progress reports and interviews. The most common challenges were related to the population with which they worked, such as language and cultural barriers or the need to provide childcare, and their organizational capacity, including funding, staff, and turnover. Other challenges were site-specific, such as not owning the land or irrigation, and environmental, such as weather or invasive plants. A few grantees also experienced challenges engaging community members and partnering with local governments. These challenges are summarized in Table 3.

Regarding working with a population with a high proportion of renters, for example, one grantee said:

…that’s what we’re building, trying to build a community with a culture of trust and get rid of the negative ideas and the negative thoughts and nothing good comes out of here and this type of thing, so yes, we still - We achieve that to a certain level, but as I said, the other populations that come in may not stay you know, a year or however long they rent or whatever, they’re renting. It’s hard to capture those people, and it’s very unfortunate.

– Third year grantee

Another grantee had this to say about partnering with a local government:

...while the community and the community centre was on board with this grant, we did not get the support we had wanted from the [city] parks system. The places they allowed for us to plant the trees were not the most ideal environment for growing fruit trees.

– Third year grantee

Project Sustainability

Grantees described their plans for sustainability in their final reports and expanded on those plans in semi-structured interviews. These results are presented in Table 4. All grantees stated that they planned to continue or expand their projects, and most had identified specific goals for the future of their project. For example, one grantee described expanding their program to include transportation:

So there’s all sorts of elements that go into having a garden or dealing with food insecurity, for example if you don’t have a way to get to a store doesn’t matter how good the food is in the store so we’re continuing to develop our transportation and our community’s supplemental transportation initiative where we are helping people get to the gardens, grocery stores, the doctors, the dentist, the laundromat, the children’s school.

– Second year grantee

Five grantees reported in their final reports that they had already obtained additional funding, while others had plans to seek additional funding. During interviews, many grantees discussed how their participation in the grant program helped them do this because they had documented results:

...we’ve been able to take the success of last year’s program and use that to demonstrate our capacity to deliver quality programming and also to speak to the results and the change in knowledge and things like that in order to be able to obtain new funding with the demand for continued support or a next level of support.

– First year grantee

A third of the grantees reported that they established or maintained partnerships that contributed to their sustainability, by providing a sustained volunteer base or offering potential for future collaborations or funding.

Programs were also sustained by being institutionalized in some way, such as community members maintaining the program, incorporating it into ongoing programming, or a policy change within a jurisdiction. A third of the grantees stated in their final reports that they provided community members with the knowledge or skills to maintain the project, such as one first-year grantee who increased community participation in their ongoing local water quality monitoring activities. One grantee described how a policy change would sustain their project:

Because over the past year we were able to see the adoption of our project plan officially adopted in the city that will be completing like the model mile of our project, and also we.... We’ve also seen a zoning change in a different jurisdiction that ensures that our project will be built in that jurisdiction upon redevelopment of the one property that the project will go through.

– Third year grantee

The HERCULES CEC also hopes to maintain partnerships with grantees beyond the grant program. Contact information is obtained from all applicants and grantees, allowing HERCULES to maintain communication, for example by sending information about local events and resources. Some grantees also remain engaged as SAB members or by linking up with additional Emory resources. For example, HERCULES connected one grantee to an Emory University Environmental Sciences faculty member and they are now partnering to engage students from Emory and the local community in stream monitoring. Two grantees remained involved as partners with Emory scientists on HERCULES Community Based Participatory Research Pilot Grants. Grantees’ ongoing partnerships with HERCULES are reported in Table 4.

Table 4:

Project and Partnership Sustainability

| Methods to Sustain Project Reported in Final Reports | Number of grantees (n=13) |

|---|---|

| Funding and Resources | |

| Received additional funding | 5 |

| Established or maintained partnerships a | 4 |

| Seeking additional funding | 2b |

| Other c | 2 |

| Institutionalization | |

| Provided community members knowledge/skills for maintenance | 4 |

| Increased community commitment/membership | 3 |

| Incorporated project into ongoing programming | 2 |

| Other d | 3 |

| Ongoing HERCULES Engagement | Number of grantees (n=13) |

| Email list only | 8 |

| SAB Member | 3 |

| Linked to additional Emory resources | 3 |

| HERCULES Pilot Project Partner | 2 |

| Received a 2nd Community Grant | 1 |

Partnerships contributed to an increased volunteer base, project collaborations, or funding potential.

Reported by the same organization funded twice

Other sustainability methods related to funding included establishing an organizational structure with low overhead and establishing a successful funding mechanism.

Other sustainability methods related to institutionalization included: increasing community awareness about the issue, achieving local government policy adoption, and making physical improvements (e.g., soil health).

Grant Program Feedback

During the semi-structured interviews grantees were asked to provide feedback about the grant program itself. They discussed the funding amount, the technical assistance provided by HERCULES staff, additional needs of their organization that HERCULES or Emory could help address, and overall feedback about the grant program.

Funding

Grantees discussed the funding amount, how they used it, and whether or not they had additional external funding.

Grantees were mixed in their opinions of the $2500 funding amount, with about half saying that it was enough and half saying that it was insufficient to accomplish what they needed to do. For example:

2,500 was very fair, and because we’re a small organization that has like a decently low input to yield.

– First year grantee

Grantees primarily used the funds to purchase needed supplies or to support volunteers and community members’ participation or training. For example, funding provided opportunities to engage new volunteers in planting trees or filled a gap in needed supplies for a training or stipends for community members. One grantee described how they were able to engage community members:

…it gave us more autonomy and we were able to do some outreach in the community and bring people together and talk about you know, being good stewards of this little park that we have.- Third year grantee

Many grantees complemented HERCULES funding with external funding before, during, and/or after the grant period. Two grantees had not had any additional funding prior to receiving the HERCULES community grant, but acquired additional funding by the end of the grant period. Several grantees also thought that the funding increased their organization’s credibility, which, in some cases, led to additional funding opportunities. For example:

You know when we applied for funding with [the Foundation] they always want to know who else you are receiving money from. It is very important for them to see that someone else is also funding the program. So when we were applying for [the Foundation grant] we listed HERCULES and that was a benefit for us.

– Second year grantee

Technical Assistance

Most of the grantees were satisfied with the TA offered by HERCULES staff. Some grantees reported that the TA provided them with knowledge about applying for other grants and improved evaluation skills. Grantees liked that the TA was hands on and specifically liked receiving site visits.

It was just probably a little bit more hands on than some other grants that I’ve received with other non-profits, and I think for me it was a really pleasant experience to have some conversations or in person conversations with [HERCULES staff], and I think in some ways it sort of demystified the grant process… - First year grantee

A third of the grantees thought that the TA wasn’t helpful, either because they didn’t need it or they didn’t know what they needed. For example:

You know, we didn’t really receive any of that type of assistance, and it wasn’t because the HERCULES folks didn’t offer or want to you know, avail themselves to us. It was more just we had a hard time kind of identifying a way for that to happen, and it was just really because of the - kind of the nature of the work we were doing during the time of the grant. – Third year grantee

Additional Organizational Needs

Several grantees identified additional things that Emory or HERCULES could help their organizations with. These included having access to Emory’s scientists, experts, volunteer base, office space and supplies; providing administrative and professional capacity building; serving as a fiscal sponsor; and helping to secure additional funding. For example:

I’m thinking that perhaps if there is a way to connect perhaps expertise at Emory, if folks have expertise in the areas that grantees are doing their work, perhaps to kind connect folks with those resources, and I know it’s a matter of whether those researchers even have time, but I think it could have been nice to get some feedback beyond the core HERCULES team.

– First year grantee

Other Grant Program Feedback

Other feedback from grantees included the usefulness of meeting the other grantees, their interaction with the HERCULES CEC and SAB, and general comments.

Most grantees valued meeting other grantees at the beginning and end of the grant period, saying that it was helpful and increased their knowledge about other community-based work going on in the Atlanta area:

…then seeing all the other grantees at the end I was quite intrigued by each and every project, so I was able to glean from some of the things that they’ve done, and it also validated some of the things that we had done.

– Third year grantee

Several grantees also mentioned positive interactions with the HERCULES CEC or the SAB. Overall, most grantees spoke positively of the grant program, offering compliments and gratitude when asked for additional comments:

We feel like we have a super helpful program and the kind of work that you all are doing is also very helpful and so we really want to say keep doing that and picking these enthusiastic optimistic people who can take a very small amount of money and turn it to a lot of activity and progress and product and outcome. – Second year grantee

Discussion

Summary

The HERCULES Shaheed DuBois Community Grant Program, while only $2500, was able to meet the goals of a new research centre and its community engagement core (CEC). The program increased awareness of HERCULES among applicant communities, established or enhanced new relationships with community-based organizations, and identified Atlanta communities’ environmental health concerns while providing tangible results for grantees and the communities they serve.

Grantees were predominantly smaller, lower-capacity organizations that served seven distinct areas in two metro-Atlanta counties, most in historically disinvested areas. Grantees tackled a variety of community concerns, the most common being access to healthy foods, water pollution, and waste disposal/illegal dumping. Despite some grantees expressing the limitations of the funding amount, grantees were able to identify many ways in which the funding directly helped them and/or their community. Most reported using the funding to provide opportunities to participants and community members and/or to purchase needed supplies. Several grantees also said that receiving the funding increased their credibility and provided outcomes and results that helped them apply for and acquire additional funding.

Grantees also reported a variety of accomplishments, including increased community trust, knowledge, awareness, and involvement, increased organizational capacity, and material improvements. Together, the ability to document accomplishments, increase capacity and credibility, and make procedural improvements to their projects could contribute to the future success of their programming and grant applications. In fact, some grantees already reported receiving additional funding. All of our grantees planned to continue their programming, indicating that these small grants may serve as a seed for organizations to engage their community around an environmental health issue and refine or confirm their approach prior to sustaining or expanding their efforts.

The semi-structured interviews identified several components of the Shaheed Dubois Community Grant Program that enhanced community-academic partnerships. Grantees said they enjoyed the hands-on nature of the TA provided by the HERCULES CEC, and specifically mentioned using the reporting process and evaluation assistance to document activities and results. Grantees also enjoyed meeting the other grantees, HERCULES CEC, and SAB. The grant program gave community-based organizations an entry point to interface with Emory staff, students and scientists. While some grantees only interfaced with staff who were administering the grant program, others had additional interaction with Emory through program administrators, student projects, and HERCULES scientists.

Other mini grant programs have shared similar outcomes, citing new partnerships (Tendulkar et al. 2011; Teufel-Shone et al. 2019; Kegler et al. 2015), increased credibility (Kegler et al. 2016) and knowledge (Johnson et al. 2006), tangible outcomes (Jacob Arriola et al. 2015; Deacon et al. 2009), the ability to make progress on goals (Johnson et al. 2006), and leveraging funds (Kegler et al. 2015; Tendulkar et al. 2011) as successes while also noting TA as a beneficial program component (Honeycutt et al. 2012; Deacon et al. 2009).

Recommendations

Consider these successful aspects when implementing a community grant program: requirements and assistance for reporting and evaluation (Thompson et al. 2010; Kegler et al. 2015) ongoing hands-on TA (Jacob Arriola et al. 2015; Honeycutt et al. 2012; Kegler et al. 2015; Johnson et al. 2006; Deacon et al. 2009; Tendulkar et al. 2011), and opportunities for grantees to meet each other and others at the institution (Johnson et al. 2006). Additional attention should be given to identifying and addressing the TA needs of all grantees as well as identifying additional resources that the institution can provide its grantees to supplement the grant funding. As part of the TA, anticipate and plan for challenges related to a grantee’s population, program site, stakeholder engagement, and the local environment.

Another critical component is the role of an advisory board. The leadership and involvement of the HERCULES SAB in the development, implementation, and evolution of this grant program was integral. Though the CEC administered the program, the SAB ultimately chose to use the mini-grants approach and gave important input on all aspects of the program. Before replicating the model presented here it should first be discussed with a diverse group of stakeholders who can give salient advice and perspective about whether and how the program can work in a specific community. Others have also involved advisory boards when developing similar grant programs (Jacob Arriola et al. 2015; Thompson et al. 2010; Tendulkar et al. 2011; Main et al. 2012) and likewise identified stakeholder engagement as an integral component that contributed to continual program improvement.

An important aspect of the program stressed by the SAB was the emphasis on building capacity without over-burdening small organizations with time-consuming requirements. For example, our application and progress reports contain common elements but are not as lengthy or in-depth as most. Johnson et al. (2006) sought a similar capacity building balance in their Micro-Grant Project, and recommended adding trainings, specifically a grant-writing workshop, much like the grant-writing workshop recommended by our SAB.

SAB involvement also had unintended positive outcomes, including building SAB members’ capacity while strengthening our relationship with them. Similar to Tendulkar et al. (2011), a sub-group of SAB members developed the application and participated in a grant review committee, learning how to apply scoring criteria similar to a typical grant review process. These SAB members informally reported that they volunteered in order to contribute to bringing the program they developed to Atlanta-area communities (in a separate survey, a majority of SAB members said they participate in the SAB to help ensure that HERCULES activities truly benefit the community). They also reported an improved understanding of the grant process and called it an enriching experience that added value to the time they commit to HERCULES and strengthened our relationship with them In addition, some SAB members were also grantees and have remained some of the most active members.

The overall goal of building community-academic partnerships between HERCULES, community-based organizations, and SAB members was successfully achieved. The program gave community-based organizations an entry point to interface with Emory staff, students, SAB members, and scientists, increased scientists’ awareness of Atlanta communities’ environmental health concerns, and identified potential partners for subsequent projects in collaboration with HERCULES scientists (e.g., HERCULES Pilot Projects studying neighbourhood flooding, indoor mould, and soil contamination). Building partnerships has also been a key accomplishment of other grant programs (Johnson et al. 2006; Honeycutt et al. 2012; Kegler et al. 2015; Tendulkar et al. 2011; Teufel-Shone et al., 2019). Structures to establish and strengthen partnerships should be built into grant programs, either through TA or by providing networking opportunities to grantees, much like the opportunities for our grantees to present to our SAB.

The community grant program has since evolved, guided by the SAB and based on the CEC’s community-engagement goals and the evaluation results presented here. For example, a third of the grantees had difficulty utilizing the TA offered, and all wanted to sustain their programming. Others (Deacon et al. 2009) also identified the need for ongoing, adaptive, and structured TA and had similar concerns about sustainability (Deacon et al. 2009; Thompson et al. 2010). Our SAB proposed that if we worked with a given community for a longer duration we would be better equipped to identify their TA needs early, ensure the sustainability of their efforts, and establish a longer-term relationship with that community to better enhance their capacity to address social and environmental injustices while focusing our own resources on working more in-depth with fewer communities. This has resulted in our new Shaheed DuBois Exposome Roadshow and Community Grant Program, which consists of four phases over three years with up to $6000 in funding for each community group. This enhanced program includes structured TA around goal setting and action planning to address a community-identified need, similar to that described by Deacon et al. (2009) and Teufel-Shone et al. (2018). This program also intends to build on our SAB capacity, by incorporating SAB members into the TA process, documenting their assets and making them available to grantees.

Limitations

The multiple case study evaluation presented here also had its limitations, which we plan to address when evaluating our new program. In the future, we plan to more systematically assess SAB members’ experience with the grant program, partnerships established as a result of the interactions with the SAB or faculty, whether the grant program reached the intended audience of smaller organizations with limited capacity, who utilized the opportunity to revise and resubmit their application, and whether grant-writing workshop attendees were more likely to apply and be selected. For the current evaluation, two SAB members involved in developing the grant program and reviewing applications contributed to the manuscript as co-authors, providing input on their experience with the program. Additional limitations of the current evaluation include social desirability bias, lack of long-term follow-up, and only obtaining one perspective per grantee. We address social desirability by hiring an interviewer who has not worked with the grantees and is not involved in funding decisions, who also reviews our confidentiality procedures of de-identifying interview transcripts with interviewees. SAB members, and no Emory personnel, make the funding decisions and are only shown de-identified evaluation results. Additionally, these grant reviewers give priority to new applicants each year, so reporting bias related to funding is unlikely. While we interviewed only one representative per organization (partially dictated by funding and staff limitations), we triangulated this data with document review, and this person was in the best position to identify the organizational changes reported here, as is common when evaluating community engagement initiatives (Deacon et al., 2009, Kegler et al., 2008, Kreuter et al., 2012). However, we acknowledge the possibility that social desirability influenced their responses. We have also added a focus group with participating community members to our revised program evaluation to assess additional perspectives and outcomes for each grantee. This evaluation was able to capture organizational outcomes that occurred immediately during or upon completion of the one-year grant. Lastly, long-term follow-up is built-in to our revised program due to program duration. While a multiple case study has inherent limitations, this evaluation allowed us to explore a range of implementation factors and outcomes to document the potential of and improve upon our community grant program. Future evaluations could assess the processes and outcomes of similar grants programs in other settings.

Conclusion

This grant program differs from other community grant programs in that the goal was not to establish research partnerships or implement specific programming. Instead, it was to establish a relationship between our centre and communities in the Atlanta-area. Others have found that this is perhaps an appropriate goal for a small mini-grant, noting that they are unlikely to produce typical research results (Kegler et al. 2016; Thompson et al. 2010). Despite their differences, many public health mini-grant programs have achieved similar results.

Mini-grants are a feasible approach to build community trust and establish new partnerships in communities facing social and environmental injustices. As such, the potential implication of sharing the implementation and evaluation of this model is that other academics and agency professionals replicate and adapt it, building their own capacity for community-engaged work while increasing community capacity to address health concerns. This model goes well beyond a more typical community outreach approach in which community members are viewed as passive recipients of research findings. Specifically, we hope broad application of this unique mini-grant model will bring similar benefits to other communities, including increased community trust, knowledge, awareness, and involvement, as well as increasing capacity among both academics and communities for community-engaged research that prioritizes community concerns

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the HERCULES Stakeholder Advisory Board for their role in designing and implementing the Shaheed DuBois Community Grant Program. We would especially like to thank and honour Clarence “Shaheed” DuBois for his integral contributions, who passed after the first year of the program. This work was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P30ES019776. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest statement

The authors declare they have no actual or potential competing financial interests.

Contributor Information

Melanie Pearson, Gangarosa Department of Environmental Health, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, 1518 Clifton Rd NE, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Erin Lebow-Skelley, Department of Behavioral, Social, and Health Education Sciences, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, 1518 Clifton Rd NE, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Laura Whitaker, Department of Behavioral, Social, and Health Education Sciences, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Lynne Young, HERCULES Stakeholder Advisory Board, Pathways to Sustainability, Duluth, GA, USA.

Camilla B. Warren, HERCULES Stakeholder Advisory Board, Atlanta, GA, USA

Dana Williamson, Department of Behavioural Sciences and Health Education, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Michelle C. Kegler, Department of Behavioral, Social, and Health Education Sciences, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA

References

- Allen Michele L., Culhane-Pera Kathleen A., Pergament Shannon L., and Call Kathleen T.. 2011. “A capacity building program to promote CBPR partnerships between academic researchers and community members.” Clin Transl Sci 4 (6):428–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2011.00362.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen Michele L., Culhane‐Pera Kathleen A., Pergament Shannon L., and Call Kathleen T.. 2010. “Facilitating Research Faculty Participation in CBPR: Development of a Model Based on Key Informant Interviews.” Clin Transl Sci 3 (5):233–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2010.00231.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atlanta Regional Commission (ARC). 2018. “Atlanta Region.” Accessed October 2018 https://atlantaregional.org/.

- ARC Research. 2019. “Regional Health: Public Health in Metro Atlanta.” Atlanta Regional Commission. Accessed June 2019 https://33n.atlantaregional.com/. [Google Scholar]

- Bellows Layla. 2019. “Special Feature: Examining wage gaps by race and ethnicity.” Atlanta Regional Commission. Accessed June 2019 https://33n.atlantaregional.com/. [Google Scholar]

- Berube Alan. 2018. “City and metropolitan income inequality data reveal ups and downs through 2016.” Brookings Institution Report. [Google Scholar]

- Cargo M, and Mercer SL. 2008. “The value and challenges of participatory research: strengthening its practice.” Annu Rev Public Health 29:325–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.091307.083824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citizen Science Association. 2018. “CitizenScience.org.” Accessed October 2018 https://www.citizenscience.org/.

- Clinical Translational Science Awards Consortium. 2011. “Principles of community engagement” In, edited by Department of Health and Human Services. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Government Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- Community Campus Partnerships for Health. 2018. Accessed October 2018 www.ccphealth.org.

- Deacon Zermarie, Foster-Fishman Pennie, Mahaffey Michael, and Archer Gretchen. 2009. “Moving from preconditions for action to developing a cycle of continued social change: tapping the potential of mini-grant programs.” Journal of Community Psychology 37 (2):148–55. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20285. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- HERCULES Exposome Research Center. 2018. “HERCULES Pilot Program.” Accessed October 2018 https://emoryhercules.com/pilot-program/.

- Honeycutt S, Carvalho M, Glanz K, Daniel SD, and Kegler MC. 2012. “Research to reality: a process evaluation of a mini-grants program to disseminate evidence-based nutrition programs to rural churches and worksites.” J Public Health Manag Pract 18 (5):431–9. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e31822d4c69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel Barbara A., Schulz Amy J., Parker Edith A., and Becker Adam B.. 1998. “REVIEW OF COMMUNITY-BASED RESEARCH: Assessing Partnership Approaches to Improve Public Health.” 19 (1):173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arriola Jacob, Kimberly R, Hermstad April, Shauna St. Flemming Clair, Honeycutt Sally, Carvalho Michelle L., Cherry Sabrina T., Davis Tamara, et al. 2015. “Promoting Policy and Environmental Change in Faith-Based Organizations: Outcome Evaluation of a Mini-Grants Program.” Health Promotion Practice 17 (1):146–55. doi: 10.1177/1524839915613027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagosh J, Macaulay AC, Pluye P, Salsberg J, Bush PL, Henderson J, Sirett E, et al. 2012. “Uncovering the benefits of participatory research: implications of a realist review for health research and practice.” Milbank Q 90 (2):311–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2012.00665.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Hans H., Bobbitt-Cooke Mary, Schwarz Miriam, and White David. 2006. “Creative Partnerships for Community Health Improvement: A Qualitative Evaluation of the Healthy Carolinians Community Micro-Grant Project.” Health Promotion Practice 7 (2):162–9. doi: 10.1177/1524839905278898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kegler Michelle C., Blumenthal Daniel S., Tabia Henry Akintobi Kirsten Rodgers, Erwin Katherine, Thompson Winifred, and Hopkins Ernest. 2016. “Lessons Learned from Three Models that Use Small Grants for Building Academic-Community Partnerships for Research.” Journal of health care for the poor and underserved 27 (2):527–48. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2016.0076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kegler Michelle C., Carvalho Michelle L., Ory Marcia, Kellstedt Deb, Friedman Daniela B., James Lyndon McCracken Glenna Dawson, and Fernandez Maria. 2015. “Use of Mini-Grant to Disseminate Evidence-Based Interventions for Cancer Prevention and Control.” Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 21 (5):487–95. doi: 10.1097/phh.0000000000000228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kegler Michelle C., Norton Barbara L., and Aronson Robert. 2008. “Achieving organizational change: findings from case studies of 20 California healthy cities and communities coalitions.” Health Promotion International 23(2): 109–118. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dan009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kegler MC, & Redmon PB (2006). Using technical assistance to strengthen tobacco control capacity: evaluation findings from the Tobacco Technical Assistance Consortium. Public Health Rep, 121(5), 547–556. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter Marshall W., Kegler Michelle C., Joseph Karen T., Redwood Yanique A., Hooker Margaret. 2012. “The impact of implementing selected CBPR strategies to address disparities in urban Atlanta: a retrospective case study.” Health Education Research 27(4): 729–741. doi.org/ 10.1093/her/cys053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Main Deborah S., Felzien Maret C., Magid David J., Calonge B. Ned, O’Brien Ruth A., Kempe Allison, and Nearing Kathryn. 2012. “A Community Translational Research Pilot Grants Program to Facilitate Community–Academic Partnerships: Lessons From Colorado’s Clinical Translational Science Awards.” Progress in community health partnerships : research, education, and action 6 (3):381–7. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2012.0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM, and Saldana J. 2014. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Miller Gary W., and Jones Dean P.. 2014. “The Nature of Nurture: Refining the Definition of the Exposome.” Toxicological Sciences 137 (1):1–2. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kft251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler Meredith. 2005. “Community-based research partnerships: Challenges and opportunities.” Journal of Urban Health : Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 82 (Suppl 2):ii3–ii12. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tendulkar Shalini A., Chu Jocelyn, Opp Jennifer, Geller Alan, Ann DiGirolamo Ediss Gandelman, Grullon Milagro, Patil Pratima, King Stacey, and Hacker Karen. 2011. “A Funding Initiative for Community-Based Participatory Research: Lessons from the Harvard Catalyst Seed Grants.” Progress in community health partnerships : research, education, and action 5 (1):35–44. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2011.0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teufel-Shone NI, Schwartz AL, Hardy LJ, De Heer HD, Williamson HJ, Dunn DJ, Polingyumptewa K, Chief C. (2019). “Supporting new community-based participatory research partnerships.” International journal of environmental research and public health, 16(1), 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson Beti, Ondelacy Stephanie, Godina Ruby, and Coronado Gloria D.. 2010. “A Small Grants Program to Involve Communities in Research.” Journal of Community Health 35 (3):294–301. doi: 10.1007/s10900-010-9235-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2017. “ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates” In 2013–2017 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. American FactFinder; Accessed June 2019 https://factfinder.census.gov/. [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, Garlehner G, Lohr KN, Griffith D, Rhodes S, et al. 2004. “Community-based participatory research: assessing the evidence.” Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ) (99):1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin RK (2017). Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]