Abstract

Background

Dopamine and dopamine receptor D1 (DRD1), a member of the dopamine receptor family, have been indicated to play important roles in cancer progression, but dopamine secretion in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and the effects of DRD1 on HCC remain unclear. This study was designed to explore the contribution of the dopaminergic system to HCC and determine the relationship between DRD1 and prognosis in HCC patients.

Methods

The dopamine metabolic system was monitored using enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs). The expression of DRD1 was detected by microarray analysis, immunohistochemistry (IHC), and quantitative real‐time PCR (qRT‐PCR). Stable DRD1 knockout and overexpression cell lines were established for investigation. Transwell, colony formation, and Cell Counting Kit 8 (CCK8) assays were performed to assess the malignant behaviors of cancer cells. The cAMP/PI3K/AKT/ cAMP response element‐binding (CREB) signaling pathway was evaluated by Western blot. This pathway, which is agitated by DRD1 in striatal neurons, had been proven to participate in tumor progression. Xenograft HCC tumors were generated for in vivo experiments.

Results

Dopamine secretion increased locally in HCC due to an imbalance in dopamine metabolism, including the upregulation of dopa decarboxylase (DDC) and the downregulation of monoamine oxidase A (MAOA). Dopamine promoted the proliferation and metastasis of HCC. DRD1 was highly expressed in HCC tissues and positive DRD1 expression was related to a poor prognosis in HCC patients. The upregulation of DRD1 agitated malignant activities, including proliferation and metastasis in HCC by regulating the cAMP/PI3K/AKT/CREB pathway, and the downregulation of DRD1 had opposing effects. The effects of dopamine on HCC was reversed by depleting DRD1. SCH23390, a selective DRD1 antagonist, inhibited the proliferation and metastasis of HCC cells both in vitro and in vivo.

Conclusion

Dopamine secretion was locally increased in HCC and promoted HCC cell proliferation and metastasis. DRD1 was found to exert positive effects on HCC progression and play a vital role in the dopamine system, and could be a potential therapeutic target and prognostic biomarker for HCC.

Keywords: dopamine, dopamine receptor D1, hepatocellular carcinoma, prognosis, target therapy

Abbreviations

- CCK8

Cell Counting Kit 8

- DDC

dopa decarboxylase

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium

- DMSO

Dimethyl sulfoxide

- DRD1

dopamine receptor 1

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- MAOA

monoamine oxidase A

- OS

overall survival

- RFS

relapse‐free survival

1. BACKGROUND

Liver cancer has become one of the most common cancers in many countries and is responsible for approximately 800,000 deaths each year [1]. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) accounts FOR 70%‐85% of liver cancers in adults [2]. In China, HCC is the fourth most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer‐related death ([3, 4]). Surgical treatment is still the main therapeutic option used to treat early‐stage HCC, however, the surgical indications are limited. When the opportunity for surgery is missed, nonsurgical treatment becomes very important. Targeted molecular therapy has provided an important and effective means for treating liver cancer. Some targeted drugs, such as lenvatinib [5], regorafenib [6], and sorafenib [7], have been developed and improved the survival rate of cancer patients by approximately 30% due to their antiangiogenic and antiproliferative effects.

Neurotransmitters affect the progression of tumors by altering the tumor microenvironment [8]. Dopamine, as one of the major catecholamine neurotransmitters, plays an important role in the central nervous system. Dysfunction of the dopaminergic system can cause schizophrenia and Parkinson's disease [9]. Some epidemiological and molecular biology studies have found that schizophrenia and Parkinson's disease had different effects in different cancers and even in the same cancer, and different conclusions have been drawn [10, 11, 12, 13]. These findings implied that an imbalance in the dopaminergic system may be related to cancer development.

Dopamine works via its receptors, which belong to the G protein‐coupled receptor family. There are five subtypes of dopamine receptors, dopamine receptor D1 (DRD1), dopamine receptor D2 (DRD2), dopamine receptor D3 (DRD3), dopamine receptor D4 (DRD4), and dopamine receptor D5 (DRD5), which are divided into 2 classes, D1‐like receptors (DRD1, DRD5) and D2‐like receptors (DRD2, DRD3, DRD4), depending on their biochemical and pharmacological properties [14].

It has been found that positive expression of DRD1 in breast cancer patients indicated a poor prognosis [15], the expression of DRD2 was found in an increased level in pancreatic cancer patients, and inhibitors of DRD2 could slow tumor growth by suppressing the ERK signaling pathway [16]. In addition, inhibiting the function of DRD4 prevented the autophagy and proliferation of brain glioma stem cells, as reported by Sonam Dolma [17]. DRD1 and DRD5 had different expression levels in HCC, and thioridazine, as a dopamine receptor antagonist, suppressed metastasis in HCC and proliferation in breast cancer ([18, 19]). These evidence suggest that dopamine and dopamine receptors could influence different types of cancer [20].

The effect of dopamine on HCC has been reported in some studies ([18, 21]), however, studies on the local dopamine metabolic system in HCC are lacking. Some reports have observed an increased local secretion of dopamine in cholangiocarcinoma cell lines which contributed growth‐promoting effects [22]; suggesting an imbalance in the dopaminergic system in HCC. DRD1 has been proven to be involved in cancer progression [15] but research on the contribution of DRD1 to HCC is still lacking.

We designed this study to verify the function of the dopamine metabolic system and the expression of dopamine receptors in HCC, to explore the contribution of the dopaminergic system to HCC, and to determine the mechanisms involved in this process. The significance of dopamine receptors in the prognosis of HCC patients was also analyzed.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1. HCC patients and tissue specimens

This study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Identification code, GZR2016‐037) of Sun Yat‐sen University Cancer Center (Guangzhou, China), and informed consent was obtained from all participants. All the data and material were collected in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and conformed to relevant aspects of the ARRIVE guidelines [23]. Six pairs of HCC and corresponding non‐tumor tissue samples, which were collected from 10 patients who underwent curative surgery at the Department of Hepatobiliary Oncology, Sun Yat‐sen University Cancer Center, were used for microarray analysis. Supplementary Table 1 shows the characteristics of the patients for transcriptome sequencing. Furthermore, tissue samples from 221 HCC patients confirmed by pathology were used in this study. The patients were not treated with preoperative therapy and had no history of other malignancies. Patients with extrahepatic metastasis and HCC invading the biliary system were excluded. All the patients underwent hepatectomy for primary HCC by the same surgeon between June 9, 1999, and February 15, 2012, at the Department of Hepatobiliary Oncology, Sun Yat‐sen University Cancer Center. All 221 samples were analyzed by immunohistochemistry (IHC). The overall survival (OS) and relapse‐free survival (RFS) of the patients were analyzed using Kaplan‐Meier analysis.

2.2. Cell lines

The MHCC97‐H (RRID: CVCL_4972), MHCC97‐L (RRID: CVCL_4973), SK‐HEP‐1 (RRID: CVCL_0525), PLC/PRF/5 (RRID: CVCL_0485), Huh‐7 (RRID: CVCL_0336) human HCC cell lines were purchased from the cell bank of the Chinese Type Culture Collection (Shanghai, China), while the Hep‐3B (RRID: CVCL_0326) and hepatoblastoma Hep‐G2 (RRID: CVCL_0027) cell lines were purchased from the Guangzhou Cellcook Biotech Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, Guangdong, China). The normal liver Miha (RRID: CVCL_SA11) cell line was purchased from the cell bank of the Chinese Type Culture Collection (Shanghai, China). MHCC97‐H and MHCC97‐L represent subclones of the parental MHCC97 cell line with high and low metastatic potential, respectively. All cell lines were authenticated using short tandem repeat (STR) profiling over the last three years. The cells were cultured with Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM, Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 100 µg/mL penicillin, 100 µg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) in a 37°C incubator with 5% carbon dioxide and 85% humidity. The cells were cultured for 3 to 6 passages. All experiments were performed with mycoplasma‐free cells.

2.3. Reagents

Dopamine (S2529) was purchased from Selleck Chemicals (Houston, TX, USA). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, 20‐139) and SCH23390 (D054) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). The DRD1 antibody (NBP2‐16213) was purchased from Novus Biological (CO, USA). The PI3K (p110) (4249S), AKT (4685S), p‐AKT (R4060S), cAMP response element‐binding (CREB) (9197S), p‐CREB (9198S), glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH, 2118S) antibodies, and anti‐rabbit antibody (7074S), which served as a secondary antibody, were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA).

2.4. Microarray analysis

Samples from cancer tissues were purified and processed for hybridization according to the Agilent One‐Color Microarray‐Based Gene Expression Analysis protocol (Agilent Technologies Inc., CA, USA) with minor modifications. Array images were analyzed using the Agilent Feature Extraction software (version 11.0.1.1, Agilent Technologies Inc.). The GeneSpring GX v11.5.1 software package (Agilent Technologies Inc.) was used to perform the quantile normalization and subsequent data processing. The screening conditions used to identify differential expression were a false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05, a fold change (FC) ≥ 1.5, and a P value < 0.05. Normalized and log‐transformed data were analyzed and a hierarchical clustering heat map was drawn to visualize the genes that were differentially expressed between tumor and paired non‐tumor tissues.

2.5. Overexpression and knockout of DRD1 in HCC cells

The overexpression and shRNA sequences of DRD1 were designed by GeneCopoeia (Rockville, MD, USA), and the pEZ‐Lv105 human DRD1 overexpression vector, psi‐LVRU6GP human DRD1 shRNA vector, and pEZ‐Lv105‐GFP control vector were also constructed by GeneCopoeia. HCC cells were allowed to grow to 70% confluency before transfection. Lenti‐Pac™ HIV Expression Packaging Kits (HPK‐LvTR‐40, GeneCopoeia, Atlanta, GA, USA) were used according to the manufacturer's instructions before transfection. Overexpression and knockout were verified by Western blot analysis.

2.6. Quantitative real‐time PCR (qRT‐PCR)

RNA was extracted from HCC cell lines with the TRIzol reagent (15596026, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. cDNA synthesis was performed using a PrimeScript RT Kit (RR047A, Takara, Dalian, China). Primer pairs (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) were specific for DRD1, and GAPDH (Supplementary Table 2) served as the endogenous control. qRT‐PCR was performed with SYBR Green qRT‐PCR SuperMix (C11744500, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) on an ABI 7900HT Sequence Detector System (A46109, Applied Biosystems, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions.

2.7. Immunohistochemistry

Tumor samples from primary HCC patients were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, and serial sections were obtained after embedding in paraffin. Tissue sections were deparaffinized and hydrated through an alcohol gradient to water, and subsequently, they were blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide for endogenous peroxidase for 45 min. The sections were subjected to microwave antigen retrieval in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 10 min. Then, the primary antibody (anti‐DRD1 at a dilution of 1:150; LSA44, Lifespan Biosciences, Seattle, WA, USA) was added and incubated at 4°C overnight, followed by the addition of biotinylated goat anti‐rabbit secondary antibody (Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA) and incubation for 30 min at room temperature. DAB (K500711‐2, Dako) detection was performed under a microscope. Two experienced pathologists performed the staining assessments using the German immunoreactive score (IRS) in a double‐blinded manner. Based on staining intensity, we graded DRD1 protein staining as follows: 0 = not stained, 1 = weakly stained, 2 = moderately stained, or 3 = strongly stained. In addition, the percentage of positive tumor tissue was evaluated as follows: 0 (< 10%), 1 (10%–25%), 2 (26%–50%), 3 (51%–75%), or 4 (> 75%). After multiplying the two scores and producing a weighted score for each sample, four categories of IHC staining were determined: absent staining (−) (score, 0–3), weak staining (+) (score, 4–6), moderate staining (++) (score, 7–9), and strong staining (+++) (score, 10–12) [24].

2.8. Western blot analysis

All the proteins from HCC cell lines, whether they received treatment or not, were extracted using the Cell Lysis Buffer (9803S, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) supplemented with Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Set I (535142, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), and protein concentrations were quantified with a BCA Protein Assay Kit (23225, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) following the manufacturer's protocol. Protein electrophoresis was performed on 8%, 10%, or 12% SDS‐PAGE gels depending on the target protein's molecular weight, and the proteins were then transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (p0807, PVDF, Millipore, MA, USA). The blots were probed with primary antibodies against DRD1 (1:500 dilution), PI3K, AKT, p‐AKT, CREB, p‐CREB (1:1,000 dilution), and GAPDH (1:1,000 dilution) at 4°C overnight, and then, incubated for 1 h using the secondary antibody (1:5,000 dilution). Membranes were developed with BeyoECL Plus (P0018S, Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) and the blots were detected by using the enhanced chemiluminescence system (Pierce, USA).

2.9. Cell viability assay

Cell viability was examined with the Cell Counting Kit 8 (CCK8) assay (CK04, Dojindo, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer's protocols. The cells were seeded into 96‐well plates at a density of 6×103 cells per well overnight and then treated with DA (100 µM), SCH23390 (50 µM), and 0.1% DMSO (as a control) for 24 h. CCK8 reagent was added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 2 h. The absorbance of each well was detected at 450 nm (OD450). The sh‐NC, sh‐DRD1‐1, sh‐DRD1‐2, ex‐vector, and ex‐DRD1 cell lines were seeded at a density of 6×103 cells per well without any treatment. CCK8 assays were performed on days 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6.

2.10. Colony formation assay

Cells were seeded into 6‐well plates at a density of 1000 cells/well. After 14 days of incubation at 37°C and 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator, PBS was used to wash the colonies. All the colonies were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min. The colonies were counted after staining with 0.1% crystal violet.

2.11. Cell migration and invasion assays

Transwell assays were used to examine cell migration and invasion. The migration assays were performed using 24‐well tissue culture plates (BD Bioscience, Becton, NJ) with an 8‐µm‐pore polycarbonate membrane, and invasion using Matrigel was examined with a Membrane Invasion Culture System (Corning, NY, USA). A total of 2.0×104 SK‐Hep‐1 cells or 1.0×104 MHCC‐97H cells were inserted into each filter with serum‐free DMEM containing DA (100 µM), SCH23390 (50 µM), or 0.1% DMSO (as a control). Then, the filters were placed into 24‐well plates and surrounded with DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum. The plates were incubated for 24 h. Cotton swabs were used to remove the non‐migrated cells, and cells that had migrated through the membrane were fixed with dehydrated alcohol and stained with crystal violet. Cell migration and invasion assays were performed on cells transfected with sh‐NC, sh‐DRD1‐1, sh‐DRD1‐2, ex‐vector, and ex‐DRD1 using the same materials and methods described above, except without treatment.

2.12. Enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

The Human DDC/DOPA Decarboxylase ELISA Kit (Cat.: LS‐F7499), Human MAOA/Monoamine Oxidase ELISA Kit (Cat.: LS‐F54991), the All Species cAMP/Cyclic AMP ELISA Kit (Cat.: LS‐F10530), and the All Species Dopamine ELISA Kit (Cat.: LS‐F39204) were purchased from Lifespan Biosciences (Seattle, WA, USA). All kits were used according to the manufacturer's protocols.

2.13. Experimental animals and ethical statement

All animal experimental protocols were approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Sun Yat‐sen University Cancer Center under Project License L102012016002Q and conformed to relevant aspects of the ARRIVE guidelines [23]. Male athymic nude mice (4 weeks old) with an average body weight of 18 g were purchased from the Guangdong Medical Laboratory Animal Center (Foshan, Guangdong, China). and raised under specific pathogen‐free (SPF) conditions at the animal center of Zhongshan School Medicine, Sun Yat‐sen University.

2.14. Animal housing

Two or three mice were housed in one ventilated cage. All the cages were maintained in an animal room with 23 ± 2°C and 55 ± 10% humidity. Cages were enriched with nesting material, and food and water were provided ad libitum. The mice were monitored daily by a professional technician. A total of 30 6‐week‐old nude mice were used for the xenograft mouse model experiment, and each group of six mice was divided into five subgroups. The mice were given at least 1 week to acclimate to the conditions of the animal room before performing the experiments.

2.15. Xenograft tumor formation

Twenty‐four mice were randomly divided into group A and group B, with 12 mice in each group. In group A, xenograft tumors were generated by subcutaneously injecting 1×106 MHCC‐97H cells in 100 µL of PBS mixed with 100 µL of Matrigel (356234, Corning, NY, USA), while in group B, xenograft tumors were generated by injecting 1×106 SK‐Hep‐1 cells. When the tumors were visible (one week after inoculation), the mice in group A were allocated to groups 1 and 2 based on a computer‐generated random number, and those in group B were allocated to groups 3 and 4 in the same manner. Groups 1 and 3 were treated with vehicle control, while groups 2 and 4 were treated with SCH23390 (0.1 mg/kg) daily by intraperitoneal injection. Every 3rd day, the tumor volumes were calculated by the formula a (length) × b2 (width)/2, and their body weights were measured at the same time. After 30 days, the mice were sacrificed under anesthesia with isoflurane (Y0000858, Guidechem, Shenzhen, China) by cervical dislocation, and the weights of the tumors were measured post‐autopsy.

2.16. Statistical analysis

All the data are presented as the means with their respective standard errors (SEMs), and data analyses were performed with GraphPad Software 6 for Windows (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA) and the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 22.0, New York, USA). The association between DRD1 expression and the clinicopathological features of HCC patients was evaluated using the chi‐square test. The Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to perform multivariate analysis of all prognostic factors that were found to be significant in the univariate analysis. Kaplan‐Meier survival analysis with the log‐rank test was used to evaluate the relationship between DRD1 and OS or RFS. RFS was defined as the time from the date of the initial operation to recurrence, and OS was defined as the time from the date of the initial operation to death or June 1, 2016. Student's t‐test was used for comparisons between two groups, and the Bonferroni test was used for comparisons between all groups when the data were in normal distribution by one‐way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The homogeneity of variances between the groups was tested. P < 0.05 was considered significant. At least three replicates were performed for each in vitro experiment.

3. RESULTS

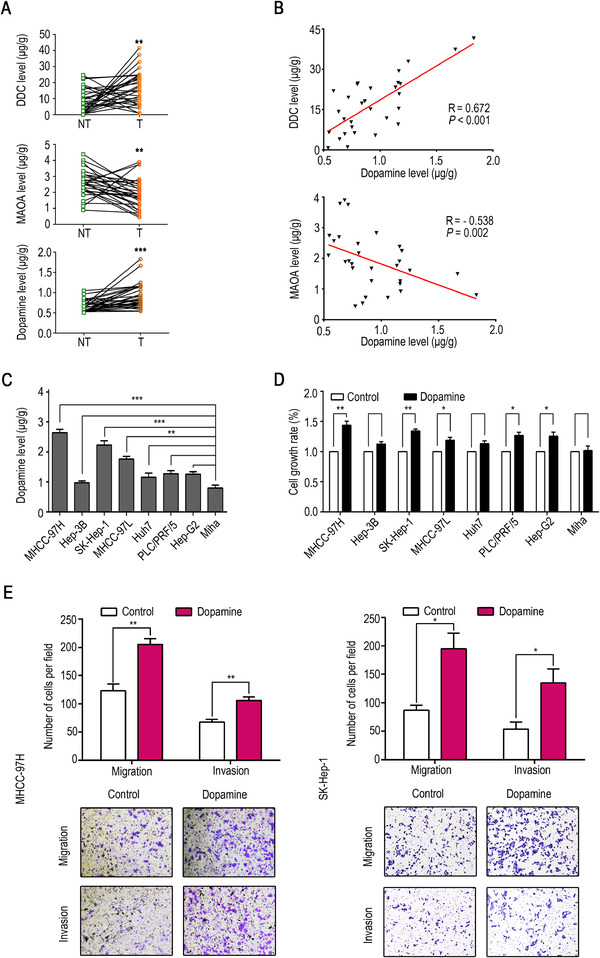

3.1. Dopamine is increased in HCC and increases the proliferation, migration, and invasion of HCC cell lines in vitro

To determine the status of dopamine secretion in HCC, we examined two key enzymes, dopa decarboxylase (DDC) and monoamine oxidase A (MAOA), which are related to dopamine secretion and can be used to monitor dopamine levels. DDC, an important enzyme for peripheral dopamine synthesis, was found more highly expressed in HCC tissues than in normal tissues and showed a positive correlation with dopamine levels (Fig. 1A and B). In contrast, the key enzyme for dopamine degradation, MAOA, was significantly decreased in HCC tissues and showed a negative correlation with dopamine levels (Fig. 1A and B). Consistent with our hypothesis, the abnormal expression of DDC and MAOA could lead to an increase in dopamine (Fig. 1A). Moreover, dopamine levels were higher in HCC cell lines MHCC‐97H, SK‐Hep‐1, and MHCC‐97L than in the non‐malignant liver cell line (Miha) (Fig. 1C). To explore the functional role of dopamine in HCC, cell viability experiments were performed, and the results showed that the MHCC‐97H, SK‐Hep‐1, MHCC‐97L, PLC/PRF/5, and Hep‐G2 cell growth rates were significantly elevated by treatment with dopamine (1 µM), for 24 h (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, transwell assays revealed that dopamine facilitated HCC cell migration and invasion in vitro (Fig. 1E). In summary, dopamine levels were increased in HCC tissues and enhanced the malignant activity of cancer cells.

FIGURE 1.

Dopamine accumulates locally in HCC and promotes the proliferation, migration, and invasion of HCC cells in vitro. (A) DDC, MAOA, and dopamine levels in 30 matched non‐tumor and tumor tissues from HCC patients. (B) Analysis of the correlation between the levels of MAOA, DDC, and dopamine in 30 human HCC tissues. (C) Dopamine levels in HCC cell lines, hepatoblastoma Hep‐G2, and a normal liver cell line (Miha). (D) The growth rate of HCC cell lines, hepatoblastoma Hep‐G2, and a normal liver cell line (Miha) after treatment with dopamine (1 µM). (E) Migration and invasion in MHCC‐97H and SK‐Hep‐1. The data are presented as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

Abbreviations: DDC, dopa decarboxylase. DRD1, dopamine receptor D1. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase. HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma. MAOA, monoamine oxidase A.

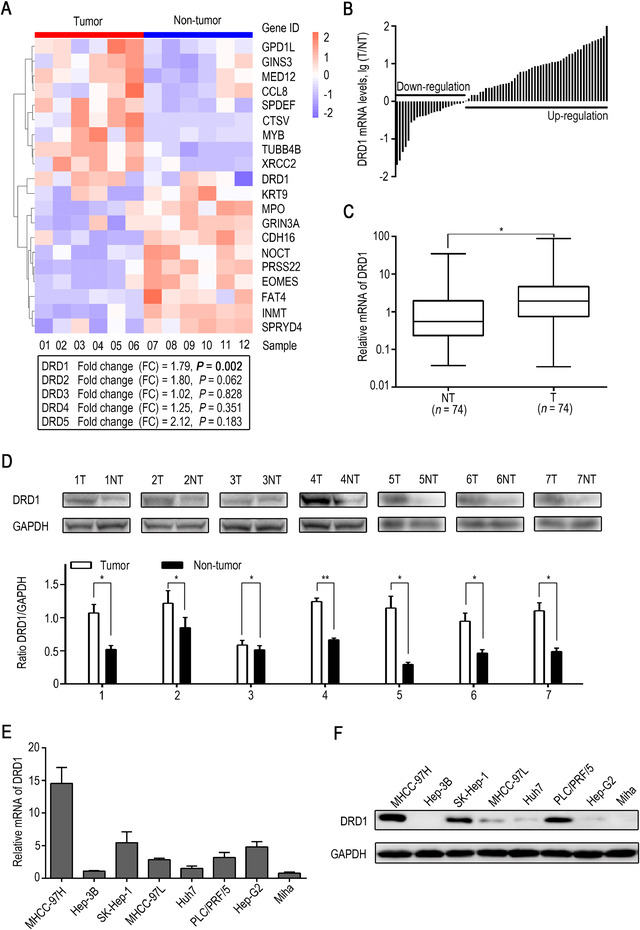

3.2. DRD1 expression in human HCC tissues and cell lines

To determine the actual target receptor of dopamine, all the dopamine receptors (DRD1, DRD2, DRD3, DRD4, and DRD5) were subjected to microarray analysis. Among all DRDs, only DRD1 mRNA was more highly expressed in HCC tissues than in matching non‐tumor tissues, while the other mRNAs were not differentially expressed (Fig. 2A). Therefore, the function of DRD1 in HCC progression was the focus of our research. To further confirm our finding, the expression of DRD1 mRNA in 74 pairs of HCC samples was examined by qRT‐PCR, and the DRD1 protein was detected in 7 pairs of HCC samples by Western blot analysis. DRD1 was more highly expressed in tumor tissues than in normal tissues at both the mRNA (Fig. 2B and C) and protein levels (Fig. 2D). DRD1 expression was also examined in liver cancer cell lines and the normal liver cell line Miha by qRT‐PCR and Western blot analyses. DRD1 was positively expressed in the HCC cell lines MHCC‐97H, SK‐Hep‐1, and PLC/PRF/5 (Fig. 2E and F), consistent with earlier results.

FIGURE 2.

Expression of dopamine receptors in human HCC tissue. (A) Hierarchical clustering heat map showing the expression of mRNAs in HCC tissues and adjacent non‐tumor tissues by microarray analysis. The whole gene list and information are supplied in the Supplementary Table 5. (B) Waterfall plot of dopamine receptor D1 (DRD1) mRNA expression in 74 paired tumor and non‐tumor samples tested by qRT‐PCR. (C) DRD1 mRNA expression in tumor and adjacent non‐tumor tissues. (D) DRD1 expression in 7 paired tumor tissues and adjacent non‐tumor tissues tested by Western blot analysis and quantification of DRD1 protein levels. (E) DRD1 mRNA levels in HCC cell lines, hepatoblastoma Hep‐G2, and a normal liver cell line (Miha) were tested by qRT‐PCR. (F) DRD1 protein levels in HCC cell lines, hepatoblastoma Hep‐G2, and a normal liver cell line (Miha) were tested by Western blot analyses. * P < 0.05.

Abbreviations: DRD1, dopamine receptor D1. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase. HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

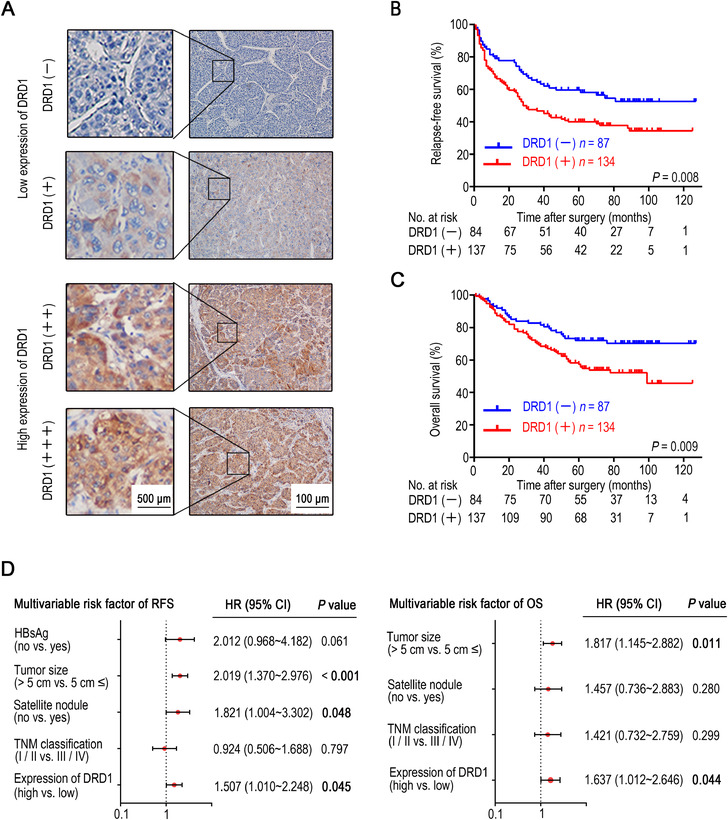

3.3. Expression of DRD1 is an independent prognostic factor for HCC

Figure 3A shows the immunohistochemical score in HCC tissues, based on which the patients were classified into a low and high DRD1 expression group. According to Kaplan‐Meier analysis of 221 patients, including 190 males and 31 females whose mean age was 48.9 (range: 20‐79) years and had a median follow‐up period of 54 (range: 1‐127) months, the expression of DRD1 was related to RFS (P = 0.008) and OS (P = 0.009) (Fig. 3B and 3C). Analysis of the correlation between DRD1 and other clinicopathological characteristics showed that the positive expression of DRD1 was significantly associated with HbsAg (P = 0.024), satellite nodule (P = 0.029), and TNM classification (P = 0.015) (Table 1). Moreover, the univariate analysis of all clinicopathological characteristics showed that DRD1 expression (P = 0.008), HbsAg (P = 0.038), tumor size (P < 0.001), satellite nodule (P < 0.001), and TNM classification (P = 0.007) were related to RFS, while DRD1 expression (P = 0.009), tumor size (P = 0.001), satellite nodule (P < 0.001), and TNM classification (P < 0.001) were related to OS (Supplementary Table 3). A multivariate Cox model was built to determine whether DRD1 is an independent prognostic factor of HCC. The analysis revealed that DRD1 expression (P = 0.045), tumor size (P < 0.001), and satellite nodule (P = 0.048) were independent prognostic factors for RFS in HCC patients. For OS, multivariate Cox analysis revealed that DRD1 (P = 0.044) and tumor size (P = 0.011) were independent prognostic factors (Fig. 3D and Supplementary Table 4). All these results suggested that DRD1 protein expression could be used to predict the prognosis of HCC and that it may be a target of dopamine in HCC.

FIGURE 3.

DRD1 expression is an independent prognostic factor for HCC. (A) DRD1 immunohistochemical score in HCC tissues according to four staining intensity classes. (B) RFS curves of patients with HCC in relation to DRD1 protein expression by Kaplan‐Meier survival analysis. (C) OS curves of patients with HCC in relation to DRD1 protein expression by Kaplan‐Meier survival analysis. (D) Cox multivariate analysis of contributory factors to recurrence‐free survival and overall survival among 221 HCC patients after hepatectomy.

Abbreviations: DRD1, dopamine receptor D1. HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma. OS, overall survival. RFS, relapse‐free survival.

TABLE 1.

Correlation of DRD1 expression with the clinicopathological characteristics in 221 patients with HCC 1

| DRD1 protein | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Total no. of cases | Low expression (case, n[%]) | High expression (case, n[%]) | P Value |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 31 | 9 (29.0) | 22 (71.0) | |

| Male | 190 | 78 (41.1) | 112 (58.9) | 0.204 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| ≤ 50 | 120 | 51 (42.5) | 69 (57.5) | |

| > 50 | 101 | 36 (35.6) | 65 (64.4) | 0.299 |

| HBsAg | ||||

| Negative | 27 | 16 (59.3) | 11 (40.7) | |

| Positive | 194 | 71 (36.6) | 123 (63.4) | 0.024 |

| Child‐Pugh classification 2 | ||||

| A | 218 | 87 (39.9) | 131 (60.1) | |

| B | 3 | 0 (0) | 3 (100) | 0.160 |

| AFP (ng/mL) | ||||

| < 20 | 78 | 29 (37.2) | 49 (62.8) | |

| 20‐400 | 53 | 19 (35.8) | 34 (64.2) | |

| >400 | 90 | 39 (43.3) | 51 (56.7) | 0.599 |

| GGT (units/L) | ||||

| ≤ 50 | 104 | 42 (40.4) | 62 (59.6) | |

| > 50 | 117 | 45 (38.5) | 72 (61.5) | 0.770 |

| Tumour size (cm) | ||||

| ≤ 5 | 103 | 41 (39.8) | 62 (60.2) | |

| > 5 | 118 | 46 (39.0) | 72 (61.0) | 0.901 |

| Satellite nodule | ||||

| Absent | 189 | 80 (42.3) | 109 (57.7) | |

| Present | 32 | 7 (21.9) | 25 (78.1) | 0.029 |

| Tumour capsule | ||||

| Absent | 69 | 29 (42.0) | 40 (58.0) | |

| Present | 152 | 58 (38.2) | 94 (61.8) | 0.585 |

| Vascular invasion | ||||

| Absent | 196 | 79 (40.3) | 117 (59.7) | |

| Present | 25 | 8 (32.0) | 17 (68.0) | 0.423 |

| Cirrhosis | ||||

| Absent | 40 | 17 (42.5) | 23 (57.5) | |

| Present | 181 | 70 (38.7) | 111 (61.3) | 0.654 |

| TNM classification 3 | ||||

| I / II | 184 | 79 (42.9) | 105 (57.1) | |

| III / IV | 37 | 8 (21.6) | 29 (78.4) | 0.015 |

Values of statistical significance are in bold.

There is no patient with Child‐Pugh Class C.

Tumor node metastasis (TNM) was evaluated based on the seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC).

Abbreviations: DRD1, dopamine receptor D1. HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma. AFP, Alpha‐fetoprotein. GGT, Gamma‐glutamyl transferase. TNM, Tumor Node Metastasis.

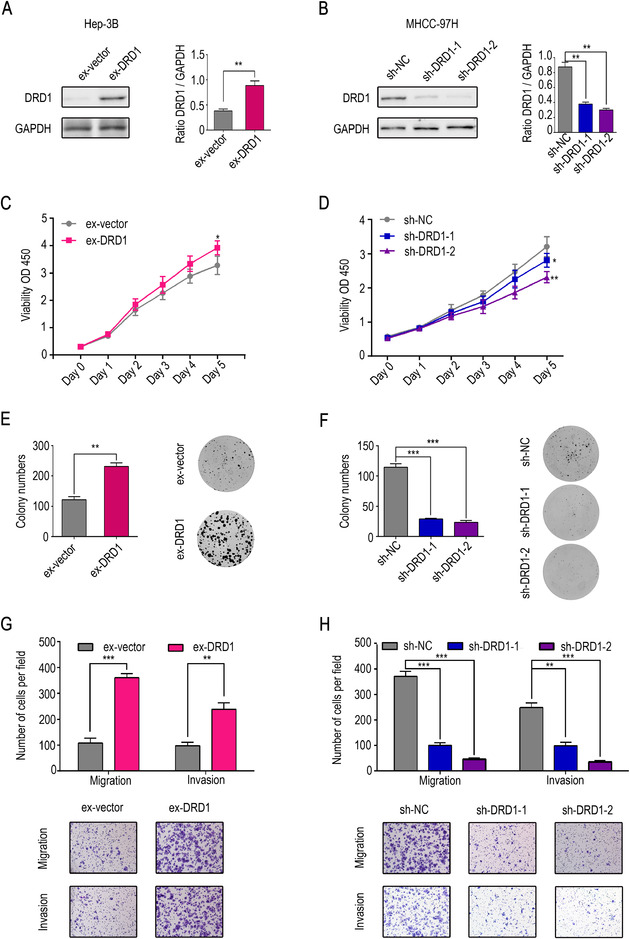

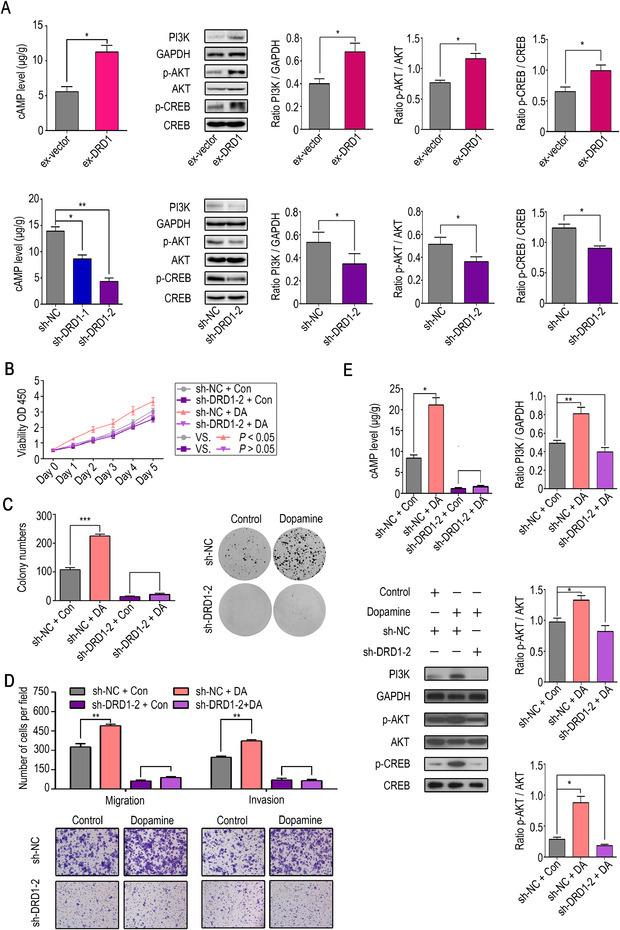

3.4. Interfering with DRD1 expression influences HCC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion in vitro by targeting the cAMP/PI3K/AKT/CREB pathway

Additional experiments were performed, and we found that DRD1 was less expressed in the Hep‐3B cell line and more highly expressed in the MHCC‐97H cell line than in other liver cancer cell lines (Fig. 2E and F), therefore, these two cell lines were used to establish a stable DRD1 knockout cell line (sh‐DRD1‐MHCC‐97H‐1, sh‐DRD1‐MHCC‐97H‐2) and a DRD1 overexpression cell line (ex‐DRD1‐Hep‐3B). DRD1 expression in the stable cell lines was significantly altered relative to that in the negative control cell lines (Fig. 4A and B).

FIGURE 4.

HCC can be regulated by interfering with DRD1 expression. (A) Western blot analysis confirmed the overexpression of DRD1 in Hep‐3B cells by stable transfection. (B) Western blot analysis confirmed the knockout of DRD1 expression in MHCC‐97H cells by stable transfection. (C) The upregulation of DRD1 expression significantly enhanced cell proliferation. (D) The downregulation of DRD1 expression weakened cell proliferation. (E) The upregulation of DRD1 expression significantly increased the colony numbers. (F) The downregulation of DRD1 expression decreased the colony numbers. (G) The upregulation of DRD1 expression significantly enhanced cell migration and invasion. (H) The downregulation of DRD1 expression weakened cell migration and invasion. The data are presented as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

Abbreviations: DRD1, dopamine receptor D1. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase. HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

In vitro experiments were performed to verify the potential function of DRD1 in HCC cell lines. Results from the CCK8 and colony formation assays revealed that the upregulation of DRD1 expression significantly enhanced cell proliferation, while the downregulation of DRD1 expression exerted the opposite effect (Fig. 4C‐F). Moreover, cell migration and invasion assays indicated that ex‐DRD1 cells had stronger migration and invasion potential than negative control cells. In contrast, sh‐DRD1 cells had weaker migration and invasion potential than negative control cells (Fig. 4G and H).

DRD1, which belongs to the Gαq family of G proteins, could stimulate the activation of the cAMP/protein kinase B (AKT)/CREB pathway in striatal neurons [25]. Furthermore, PI3K/AKT plays a vital role in many kinds of cancer, including HCC [26]. Thus, we hypothesized that DRD1 could function by targeting the cAMP/PI3K/AKT/CREB pathway in HCC cell lines. Next, ELISA and Western blot analysis were carried out to prove this hypothesis. Our findings showed that the downregulation of DRD1 suppressed the cAMP/PI3K/AKT/CREB pathway, and overexpression of DRD1 stimulated the cAMP/PI3K/AKT/CREB pathway (Fig. 5A).

FIGURE 5.

DRD1 activates the cAMP/PI3K/AKT/CREB pathway and Dopamine regulates HCC cell malignant behaviors via DRD1. (A) ELISA and Western blot analysis showed that the downregulation of DRD1 suppressed the cAMP/PI3K/AKT/CREB pathway, and the overexpression of DRD1 stimulated the cAMP/PI3K/AKT/CREB pathway. (B) Cell viability assay in sh‐DRD1 and sh‐NC cells with or without dopamine treatment (1 µM). (C) Colony formation assay in sh‐DRD1 and sh‐NC cells with or without dopamine treatment (1 µM). (D) Migration and invasion in sh‐DRD1 and sh‐NC cells with or without dopamine treatment (1 µM). (E) The cAMP/PI3K/AKT/CREB pathway was affected by treatment with dopamine (1 µM). The data are presented as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Abbreviations: DRD1, dopamine receptor D1. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase. HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma. cAMP, 3',5'‐cyclic adenosine monophosphate. PI3K, phosphoinositide 3‐kinase. AKT, protein kinase B. CREB, cAMP response element‐binding protein.

3.5. DRD1 expression plays a key role in the effects of dopamine on HCC cell lines

It was previously shown that DRD1 expression could alter HCC cell malignant activity. DRD1 interacted with dopamine much more easily than other dopamine receptors because of its very lower Ki value [27]. Therefore, we hypothesized that DRD1 might play a key role in the mechanism by which dopamine impacts HCC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion in vitro. To confirm our hypothesis, RNA interference was first implemented to knockout DRD1 expression, and then the cell lines were treated with dopamine. Cell proliferation and invasion were observed by CCK8, colony formation assay, and transwell assays. The results suggested that the shRNA knockout of DRD1 abrogated the effects of dopamine on HCC cells, including both proliferation (Fig. 5B and C) and invasion (Fig. 5D). Consistent with previous results, dopamine activated the cAMP/PI3K/AKT/CREB pathway, which was reversed by the shRNA knockout of DRD1 (Fig. 5E). In conclusion, dopamine promotes HCC cell malignant activity through DRD1.

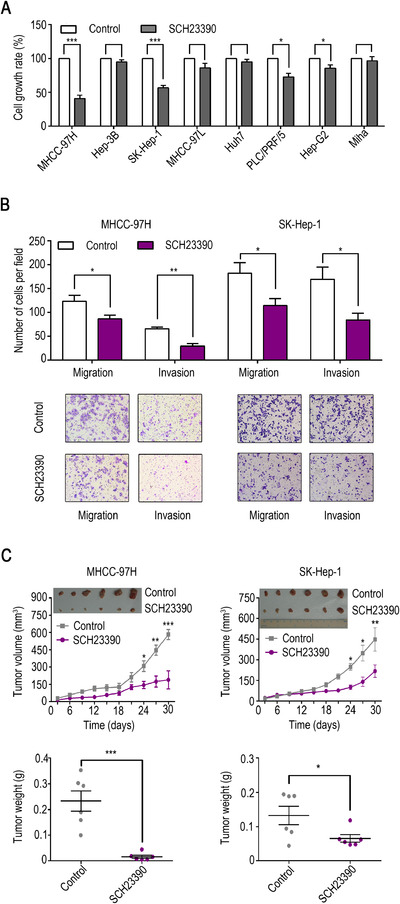

3.6. SCH23390 displays a tumor‐suppressive role both in vitro and in vivo

To determine whether DRD1 could be a potential target in the treatment of HCC, SCH23390, a selective DRD1 antagonist, was used as a targeted therapy for HCC. First, the viability of liver cancer cell lines and Miha cells was assessed after treatment with SCH23390 (100 µM), and we found that the viability of MHCC‐97H and SK‐Hep‐1 cells was the most significantly suppressed (P < 0.001) (Fig. 6A). Moreover, SCH23390 significantly reduced the number of migrated and invaded cells (Fig. 6B). In addition to these in vitro experiments, a xenograft tumor model was built to verify the effect of SCH23390 in vivo. As expected, SCH23390 inhibited tumor growth (compared to the control treatment) (Fig. 6C). All these results demonstrated that SCH23390 plays a tumor‐suppressive role both in vitro and in vivo.

FIGURE 6.

SCH23390 plays a tumor‐suppressive role both in vitro and in vivo. (A) Cell viability assay in HCC cell lines, hepatoblastoma Hep‐G2, and Miha cells after treatment with SCH23390 (100 µM, a selective DRD1 antagonist). (B) Migration and invasion of MHCC‐97H and SK‐Hep‐1 cells after treatment with SCH23390. (C) SCH23390 (0.1 mg/kg) restrained tumor growth (compared with the control) in the xenograft tumor model. The data are presented as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

Abbreviations: DRD1, dopamine receptor D1. HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

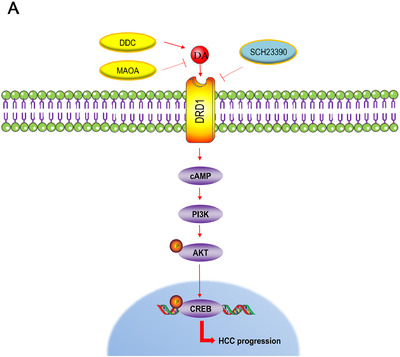

All these results suggest that the abnormal expression of DDC and MAOA could lead to an increase in dopamine which could contribute to HCC progression, and DRD1 plays a vital role in the dopamine system. SCH23390, a selective DRD1 antagonist, displays a tumor‐suppressive role both in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 7).

FIGURE 7.

Model depicting the possible mechanisms of the dopaminergic system locally contributed to HCC progression via DRD1.

4. DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to verify that dopamine secretion was increased locally in HCC due to an imbalance in dopamine metabolism, including the upregulation of DDC and the downregulation of MAOA. Dopamine promoted the proliferation and metastasis of HCC, but the effects were reversed by the depletion of DRD1. DRD1 altered the malignant activities of HCC cells by regulating the cAMP/PI3K/AKT/CREB pathway. SCH23390, a selective DRD1 antagonist, inhibited the proliferation and metastasis of HCC both in vitro and in vivo. DRD1 was highly expressed in HCC tissues, and the positive expression of DRD1 was related to poor prognosis in HCC patients.

Previous research demonstrated that increased local dopamine secretion because of metabolic enzyme dysregulation promoted cell growth in cholangiocarcinoma [22] because DDC was increased locally. Furthermore, unambiguous evidence showed that MAOA, the major degrading enzyme of catecholamines, including dopamine, inhibited HCC metastasis but was downregulated in HCC [28]. We found that abnormal increases in DDC and decreases in MAOA caused dopamine to accumulate locally in HCC. In addition, dopamine was shown to facilitate HCC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion; consistent with observations in cholangiocarcinoma [22].

Dopamine, as a neurotransmitter in the central nervous system, can bind to DRD1 to induce changes in cell behavior [29]. According to the results of the present study, DRD1 played a vital role in the dopaminergic system of HCC, and blocking DRD1 interrupted the effects of dopamine. SCH23390 has been shown to increase the susceptibility of colorectal cancer cells to the anticancer effects of ONC201 [30]. Furthermore, we proved that SCH23390 suppresses the progression of HCC. To date, there are few reports of DRD1 as a biomarker for prognosis prediction in cancer, especially in regard to HCC. Our data showed that DRD1 was an independent prognostic factor for OS and RFS, and the positive expression of DRD1 was related to a poor prognosis, which was also consistent with observations found in breast cancer [15].

The PI3K/AKT signaling pathway has been reported to be constantly stimulated in cancer and plays a major role in regulating the malignant behaviors of cancer cells [26]. Emerging evidence has shown that activating the PI3K/AKT/CREB signaling pathway promotes cancer progression [31]. DRD1 accomplishes its function by increasing cAMP ([32, 33]). Our current research revealed that interfering with DRD1 expression effectively influenced HCC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion in vitro by targeting the cAMP/PI3K/AKT/CREB pathway. A previous investigation indicated that the DRD1 agonist SKF38393 agitated the AKT/CREB signaling pathway in striatal neurons.

In previous studies, we found that the relationship between dopamine receptors and tumors was very diverse and unclear, and dopamine receptors functioned differently in various tumors. For example, DRD2 exerted opposite functions in the development of brain gliomas and lung cancer ([34, 35]), and dopamine promoted the proliferation of cholangiocarcinoma cells [22] and inhibited the growth of glioma [36]. In the same tumor type, different dopamine receptors could also have different functions. Thioridazine, a DRD2 inhibitor, inhibited the growth of breast tumors, and fenoldopam, a DRD1 agonist, exerted a similar effect [15]. We hypothesized that this could be because D1‐like receptors and D2‐like receptors have contrasting functions in many signaling pathways [27]. Moreover, according to our experimental results, the expression levels of five dopamine receptors were varied in different tumor tissues. Even a single type of dopamine receptor could be expressed differently in different HCC cell lines. Furthermore, the affinity between dopamine and each receptor is diverse [27], and these complicated relationships may lead to the diverse and unclear findings of dopamine receptors in cancer.

It is important to obtain a more detailed and accurate understanding of the interaction between dopamine, DRD1, and HCC to identify a treatment strategy for HCC patients. Patients with positive DRD1 expression have a poor prognosis, but DRD1 targeted therapy may slow tumor progression and could benefit the patients. Dopamine participates in various normal physiological activities in the whole body, especially the nervous system. If it simply had direct interference with the function of dopamine, there may be various uncontrollable side effects, and the health of the patient may even be threatened. According to our research, DRD1 is a key player involved in dopamine's effect on HCC, so blocking the function of DRD1 in HCC could be a safe treatment and could provide additional options for the comprehensive treatment of HCC.

Although DRD2, DRD3, DRD4, and DRD5 were not the major subjects of this research, the effects of other dopamine receptors on HCC cannot be ignored. The interplay between DRD1 and HCC remains complex, so additional experiments and clinical studies are needed in the future.

5. CONCLUSION

Dopamine secretion was increased locally in HCC and promoted HCC cell proliferation and metastasis. DRD1 was more highly expressed in tumor tissues at both the mRNA and protein levels. DRD1 was found to exert positive effects on HCC progression and played a vital role in the dopamine system. SCH23390, a selective DRD1 antagonist, displayed a tumor‐suppressive role both in vitro and in vivo. DRD1 could be a potential therapeutic target and prognostic biomarker for HCC.

DECLARATIONS

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Sun Yat‐sen University Cancer Center (Guangzhou, Guangdong, China), and informed consent was obtained from the participants. All the data and material have been performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and conformed to relevant aspects of the ARRIVE guidelines.

AUTHOR'S CONTRIBUTIONS

DTC and WAZ designed this study. YY, JHP, YHC, and WX performed all the experiments. YY, JHP, YHC, and QL collected clinical data. YY, WX, QL, DYW, and XSZ interpreted the data. DTC, JDX, CHM, YFY, and WAZ offered technical support. YY, DTC, and WAZ wrote the manuscript. All authors polished the paper.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

6.

FUNDING

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 81971057 to WAZ and grant 81902490 to DTC).

Supporting information

Supporting Table S1‐S4

Supporting Table S5

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank our group members for all the assistance they provided for this study. We thank Springer Nature Author Services (SNAS) for proofreading this manuscript.

Yan Y, Pan J, Chen Y, et al. Increased dopamine and its receptor dopamine receptor D1 promote tumor growth in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Commun. 2020;40:694–710. 10.1002/cac2.12103

Contributor Information

Weian Zeng, Email: zengwa@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Dongtai Chen, Email: chendt@sysucc.org.cn.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The raw data of this paper have been uploaded onto the Research Data Deposit (RDD) with an RDD number of RDDB2020000964.

REFERENCES

- 1. Collaborators GBDCoD . Global, regional, and national age‐sex‐specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980‐2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1736‐1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394‐424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yang JD, Hainaut P, Gores GJ, Amadou A, Plymoth A, Roberts LR. A global view of hepatocellular carcinoma: trends, risk, prevention and management. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2019;16(10):589‐604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cao M, Li H, Sun D, Chen W. Cancer burden of major cancers in China: A need for sustainable actions. Cancer Commun (Lond). 2020;40(5):205‐210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baxter MA, Glen H, Evans TR. Lenvatinib and its use in the treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Future Oncol. 2018;14(20):2021‐2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Personeni N, Pressiani T, Santoro A, Rimassa L. Regorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma: latest evidence and clinical implications. Drugs Context. 2018;7:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, Kim JS, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia‐Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(1):25‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Faulkner S, Jobling P, March B, Jiang CC, Hondermarck H. Tumor Neurobiology and the War of Nerves in Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2019;9(6):702‐710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Howes OD, Kambeitz J, Kim E, Stahl D, Slifstein M, Abi‐Dargham A, et al. The nature of dopamine dysfunction in schizophrenia and what this means for treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(8):776‐86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li H, Li J, Yu X, Zheng H, Sun X, Lu Y, et al. The incidence rate of cancer in patients with schizophrenia: A meta‐analysis of cohort studies. Schizophr Res. 2018;195:519‐528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Agay N, Flaks‐Manov N, Nitzan U, Hoshen MB, Levkovitz Y, Munitz H. Cancer prevalence in Israeli men and women with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2017;258:262‐267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fois AF, Wotton CJ, Yeates D, Turner MR, Goldacre MJ. Cancer in patients with motor neuron disease, multiple sclerosis and Parkinson's disease: record linkage studies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81(2):215‐221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Driver JA, Logroscino G, Buring JE, Gaziano JM, Kurth T. A prospective cohort study of cancer incidence following the diagnosis of Parkinson's disease. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(6):1260‐1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gingrich JA, Caron MG. Recent advances in the molecular biology of dopamine receptors. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1993;16:299‐321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Borcherding DC, Tong W, Hugo ER, Barnard DF, Fox S, LaSance K, et al. Expression and therapeutic targeting of dopamine receptor‐1 (D1R) in breast cancer. Oncogene. 2016;35(24):3103‐3113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jandaghi P, Najafabadi HS, Bauer AS, Papadakis AI, Fassan M, Hall A, et al. Expression of DRD2 Is Increased in Human Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma and Inhibitors Slow Tumor Growth in Mice. Gastroenterology. 2016;151(6):1218‐1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dolma S, Selvadurai HJ, Lan X, Lee L, Kushida M, Voisin V, et al. Inhibition of Dopamine Receptor D4 Impedes Autophagic Flux, Proliferation, and Survival of Glioblastoma Stem Cells. Cancer Cell. 2016;29(6):859‐873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lu M, Li J, Luo Z, Zhang S, Xue S, Wang K, et al. Roles of dopamine receptors and their antagonist thioridazine in hepatoma metastasis. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;8:1543‐52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yin T, He S, Shen G, Ye T, Guo F, Wang Y. Dopamine receptor antagonist thioridazine inhibits tumor growth in a murine breast cancer model. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12(3):4103‐4108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jiang SH, Hu LP, Wang X, Li J, Zhang ZG. Neurotransmitters: emerging targets in cancer. Oncogene. 2020;39(3):503‐515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhang QB, Zhang BH, Zhang KZ, Meng XT, Jia QA, Zhang QB, et al. Moderate swimming suppressed the growth and metastasis of the transplanted liver cancer in mice model: with reference to nervous system. Oncogene. 2016;35(31):4122‐4131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Coufal M, Invernizzi P, Gaudio E, Bernuzzi F, Frampton GA, Onori P, et al. Increased local dopamine secretion has growth‐promoting effects in cholangiocarcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2010;126(9):2112‐22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kilkenny C, Browne WJ, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. Improving bioscience research reporting: the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20(4):256‐260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chen DT, Pan JH, Chen YH, Xing W, Yan Y, Yuan YF, et al. The mu‐opioid receptor is a molecular marker for poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma and represents a potential therapeutic target. Br J Anaesth. 2019;122(6):e157‐e167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Brami‐Cherrier K, Valjent E, Garcia M, Pages C, Hipskind RA, Caboche J. Dopamine induces a PI3‐kinase‐independent activation of Akt in striatal neurons: a new route to cAMP response element‐binding protein phosphorylation. J Neurosci. 2002;22(20):8911‐8921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jiang N, Dai Q, Su X, Fu J, Feng X, Peng J. Role of PI3K/AKT pathway in cancer: the framework of malignant behavior. Mol Biol Rep. 2020;47(6):4587‐4629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vallone D, Picetti R, Borrelli E. Structure and function of dopamine receptors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24(1):125‐132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li J, Yang XM, Wang YH, Feng MX, Liu XJ, Zhang YL, et al. Monoamine oxidase A suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis by inhibiting the adrenergic system and its transactivation of EGFR signaling. J Hepatol. 2014;60(6):1225‐1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yan Y, Jiang W, Liu L, Wang X, Ding C, Tian Z, et al. Dopamine controls systemic inflammation through inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome. Cell. 2015;160(1‐2):62‐73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kline CLB, Ralff MD, Lulla AR, Wagner JM, Abbosh PH, Dicker DT, et al. Role of Dopamine Receptors in the Anticancer Activity of ONC201. Neoplasia. 2018;20(1):80‐91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ji M, Yao Y, Liu A, Shi L, Chen D, Tang L, et al. lncRNA H19 binds VGF and promotes pNEN progression via PI3K/AKT/CREB signaling. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2019;26(7):643‐658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Monsma FJ, Jr., Mahan LC, McVittie LD, Gerfen CR, Sibley DR. Molecular cloning and expression of a D1 dopamine receptor linked to adenylyl cyclase activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87(17):6723‐6727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cosentino M, Kustrimovic N, Ferrari M, Rasini E, Marino F. cAMP levels in lymphocytes and CD4(+) regulatory T‐cell functions are affected by dopamine receptor gene polymorphisms. Immunology. 2018;153(3):337‐341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li J, Zhu S, Kozono D, Ng K, Futalan D, Shen Y, et al. Genome‐wide shRNA screen revealed integrated mitogenic signaling between dopamine receptor D2 (DRD2) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in glioblastoma. Oncotarget. 2014;5(4):882‐893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cherubini E, Di Napoli A, Noto A, Osman GA, Esposito MC, Mariotta S, et al. Genetic and Functional Analysis of Polymorphisms in the Human Dopamine Receptor and Transporter Genes in Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2016;231(2):345‐356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Qin T, Wang C, Chen X, Duan C, Zhang X, Zhang J, et al. Dopamine induces growth inhibition and vascular normalization through reprogramming M2‐polarized macrophages in rat C6 glioma. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2015;286(2):112‐123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Table S1‐S4

Supporting Table S5

Data Availability Statement

The raw data of this paper have been uploaded onto the Research Data Deposit (RDD) with an RDD number of RDDB2020000964.