Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has put the world economy at an unprecedented position and protecting society from the infection is at the core of all measures. As the COVID-19 virus stays longer on plastic and stainless steel materials, hence the healthcare wastes (HCW), coming out of the treatment of COVID-19 infected patients can be one of the potential route for transmission of infection. Therefore, the present study analyses the dimensions of sustainable HCWM by using a multi-method approach: PESTEL (political, economic, social, technological, environmental and legal) analysis, TISM (total interpretive structural modeling) and fuzzy- MICMAC (cross-impact matrix multiplication applied to classification) analysis. The opted research framework yields 17 PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak through the literature survey and experts’ discussions. Then, the TISM methodology developed a hierarchical digraph of all the 17 dimensions of sustainable HCWM based on the interrelationships. Fuzzy-MICMAC analysis classified all 17 PESTEL dimensions into four groups depending upon their driving and dependence powers. The study concluded that the policy framework for targeting political, legal and environmental issues should be the immediate concern of the worldwide governments and health officials. The effluent control and compliance to environmental laws being the output dimensions should be tracked regularly for ensuring the cleaner production in healthcare services. The PESTEL analysis will help the hospitals’ managers and policymakers to understand the macro-environment surrounding the HCWM.

Keywords: COVID-19 outbreak, Pandemic, Sustainability, Healthcare waste management (HCWM), PESTEL, TISM

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

History has witnessed the various pandemics like: SARS (Meyers et al., 2005), H5N1 (De Jong et al., 2006), H1N1 swine flu (Coburn et al., 2009), HIV (Fischl et al., 1992), Dengue (Radke et al., 2012), Plague (Rayor, 1985), Ebola (Bermejo et al., 2006), Cholera (Chin et al., 2011), Zika Virus (Duffy et al., 2009), COVID 19 (Rothan and Byrareddy, 2020), etc. which have endangered the whole world from time to time. The recent COVID-19 outbreak has also put the healthcare services at the alarming positions worldwide. More than 48 million people have been infected and approximately 1.2 million people have already lost their lives due to the COVID-19 outbreak worldwide (Health Bulletin, WHO, 06th Nov 2020). India is also adversely effected and right standing in the second position after USA, accounting for more than 8.4 million COVID-19 patients (Health Bulletin, WHO, 06th Nov 2020).https://indianexpress.com/article/india/coronavirus-india-live-news-updates-covid-19-cases-tracker-deaths-lockdown-latest-news-covid-19-vaccine-6522197/Consequently, the health emergencies have exerted an exceptional burden on routine activities and commercial businesses (Rothan and Byrareddy, 2020). For every Nation, providing immediate medical services and setting up more and more COVID-19 healthcare facilities is the need of the hour. Curing the active cases of COVID-19 infected patients, as well as nipping the spread of the infection in the whole society, have come out as significant challenges for the World Health Organization (WHO) and all States’ Governments.

One of the critical steps in controlling the spread of the infection is to handle the healthcare wastes (HCW) coming from the COVID-19 treatment centers more carefully. As the HCWs coming from corona positive patients will keep on mounting with an increasing number of infected patients, the handling and disposal will continue to pose considerable challenges to healthcare facilities. Hence, HCW handling and management have become a crucial part in controlling the spread of the COVID-19 virus.

With recent developments due to the COVID-19 outbreak, the definition of medical waste has also changed. As now, some of the wastes like food wastes and other stationery items, which were not earlier considered as infectious medical wastes, but, soon after coming in contact with COVID-19 patients need to be handled like infectious wastes (World Health Organization, 2020). Corona waste is not only limited to hospitals, but people who are recovering at homes or asymptomatic patients are throwing their garbage in the common dustbins, which may spread the infection to the whole society (World Health Organization, 2020). The healthcare workers, infected patients, housekeeping staff, waste handlers etc. are rapidly exposed to disposable medical wastes like: masks, gloves, personal protectives equipment, testing kits.

Not only the infectious nature of the COVID-19 infected HCW, but the sudden increase in the generation rates of wastes, is also a significant challenge to the hospitals’ managers. As per Calma (2020), due to the Corona pandemic, the hospitals in China are daily producing tons of medical wastes and are almost six times higher than the regular quantity is generated. One study conducted in Wuhan, China, which is also considered as the epicentre for the COVID-19 outbreak, has shown that after the coronavirus outbreak the daily quantity of medical wastes generated has increased from 0.6 kg/patient to 2.5 kg/patient (Yu et al., 2020). Abu-Qdais et al. (2020) did the statistical analysis of the medical waste generated from the hospital in Jordan and resulted that the quantity of medical waste has jumped from 3.95 kg/patient/day to 14.16 kg/patient/day after the COVID-19 outbreak. Hence, the COVID-19 pandemic has escalated the medical waste quantity by approximately five-seven times higher in all over the healthcare facilities worldwide.

The scope of the current study is to provide the cleaner and sustainable healthcare services worldwide, while fighting against COVID-19 outbreak. Therefore, the macro-environment surrounding the management of HCW coming from COVID-19 treatment centers have been analyzed in the present study. In this regrad, WHO has also published the initial update on March 2020, where, the focus was on sanitation, hand hygiene, safeguarding waste handling workers, and stressed more on strengthening the water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) services in the COVID-19 healthcare facilities. WHO has issued some strict guidelines for WASH and COVID-19 facilities (World Health Organization, 2020): i) WASH practitioners should continuously ensure hand hygiene by using alcohol-based sanitizer or soap. ii) For providing safe drinking water and sanitation services, the water should be disinfected regularly. Also, the WASH practitioners should be adequately trained to use personal protective equipment (PPE). iii) The safe water management and sanitation services will not only help in fighting against the COVID-19 epidemic outbreak, but, will also control the other infectious diseases.

1.1. Research questions and objectives

The various environmental protection agencies (like: WHO, Environment and Pollution Control Boards, Central Pollution Control Board etc.) regulate the healthcare waste management (HCWM) as per the guidelines provided in the BMW (handling and management rules, 1998). But, still, to fight against the current pandemic and to analyze the various hurdles for implementing sustainable HCWM during this COVID-19 outbreak, the present study seeks to answer the following research questions like: what are the various political, economic, social, technological, environmental and legal factors in the macro-environment, which can affect the decision-making and strategy formulation, for developing a sustainable HCWM system? Secondly, how can these identified factors be arranged as per their dependence and driving powers in the overall framework? And lastly, how can the factors of sustainable HCWM be classified as per their importance for improving the overall performance during the COVID-19 outbreak? To answer the above research questions, the present study has targeted the following objectives:

-

i)

To identify the various factors under political, economic, social, technological, environmental, and legal dimensions of sustainable HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak using PESTEL analysis approach.

-

ii)

To explore the interrelationships among the various factors under PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM by using total interpretive structural modeling (TISM).

-

iii)

To classify the factors of sustainable HCWM during COVID-19 outbreak into the following four groups: autonomous, dependent, linkage, and independent groups using Fuzzy-MICMAC analysis.

Hence, the present study seeks the application of PESTEL analysis (Song et al., 2017) to identify the dimensions of sustainable HCWM during COVID-19 breakout. PESTEL analysis has been used as a qualitative tool to explore the macro-environment surrounding the sustainable HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak (Song et al., 2017; Mkude and Wimmer, 2015). PESTEL analysis will help in understanding the whole situation, including an extra burden on the existing waste management system from the macro perspective (Mkude and Wimmer, 2015). Thereafter, the study has applied a TISM methodology to model the factors under PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak (Zorpas, 2020; Zhao et al., 2020). TISM is very useful in defining the interrelationships among all the identified factors under PESTEL dimensions and articulates the problem in a simplified structure (Raut et al., 2018; Thakur and Ramesh, 2016). Since, the strength of interrelationships among all the PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM is not equal, hence, the fuzzy-MICMAC analysis will do the sensitivity analysis of the defined interrelationships (Zhao et al., 2020).

The remainder of the study has been organized in the following sections: Section 2 highlights the current status of HCWM and also the supportive literature for the various PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM. Justification of the proposed solution methodology has also been given in this section. Section 3 illustrates the research methods and proposed research framework for implementing sustainable HCWM practices during the COVID-19 outbreak. Section 4 applies the proposed research framework to develop the TISM model and classifying the PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM depending upon their overall importance in the system. The results of the study have been presented and discussed in Section 5 and also managerial implications have been highlighted. Section 6 concludes the whole paper and highlights future research directions in the concerned area.

2. Literature review

2.1. HCWM: challenges during COVID-19 outbreak

The COVID-19 outbreak has put extra pressure on the hospitals to manage their infectious wastes from the treatment of corona-virus infected people. Throughout the world, steep growth has been noticed in the generation rates of the HCW, while treating the COVID-19 patients. And if this infectious HCW is not collected and treated properly, then it will poss significant risks to both medical workers as well as the patients (Saeidi-Mobarakeh et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2020). This extra amount of HCW is evident in every part of the world, due to the enhanced usage of protection items like: personal protective kits, masks, face shielding, gloves and other disposable items (ECDC, 2020). Hence, the role of reverse supply chain becomes crucial to protect the society and environment from the infectious HCW (Qdais et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2020). So far, researchers around the world have focussed on optimizing the reverse supply chains for minimizing the operational costs (Yu et al., 2020; Budak and Ustundag, 2017; Shi et al., 2009). But, the COVID-19 outbreak requires more focus on controlling the spread of infections from the HCWs coming from treatment centers.

The HCWM in developing nations like India is continuously facing challenges since its inception: i) recycling of plastic medical wastes like syringes, bottles etc., by the rag-pickers without using proper protection and sterilization (Thakur and Ramesh, 2017). ii) As per the report of the International Clinical Epidemiology Network, approximately 54% of tertiary, 60% of secondary and 82% of the primary healthcare facilities have failed to implement the proper HCWM system (INCLEN, 2014). iii) increasing level of healthcare facilities, disposable items and population burden are creating an alarming situation for the Pollution Control Board, in developing countries like India and China (Thakur and Ramesh, 2018). iv) mixing of the general wastes with the infectious HCW and open burning of the HCWs releasing harmful gases in the environment (Aung et al., 2019; Thakur and Ramesh, 2016; Gupta et al., 2009). v) poor maintenance of HCWs records, hiding the actual data, unauthorized hospitals are some of the key administrative issues in managing the HCW. This poorly managed HCW may lead to the generation of so many other diseases along with COVID-19, like: gastroenteric infection, respiratory infection, ocular infection, genital infection, skin infection, anthrax, meningitis, AIDS, haemorrhagic fevers, septicaemia, bacteraemia, candidaemia, viral hepatitis A, B and C, avian influenza etc. (WHO, 2014).

2.2. PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM

Here, the macro-environment surrounding the sustainable HCWM during the COVID-19 pandemic, has been explored under six main dimensions: political, economic, social, technological, environmental, and legal.

2.2.1. Political dimensions

The Governments’ willingness and support are crucial for ensuring sustainable practices in any industry, especially when it is related to the handling of byproducts produced (Thakur and Mangla, 2019; Townend et al., 2009). Through the regulatory body, political interventions are required to set and monitor the constitutional framework for handling the HCW during the COVID-19 outbreak (Song et al., 2017; WHO, 2020). Moreover, the Government should promote research and development (R&D) activities in the area of sustainable HCWM. Also, financial subsidies in-terms of tax benefits, price subsidy, developing SEZs (special economic zones), etc. to waste handlers should be provided (Rothan and Byrareddy, 2020; Mkude and Wimmer, 2015). The worldwide governments can invite the private investments in HCWM by adopting PPP (public-private partnership) model to develop better healthcare infrastructure and ease out the financial burden on the Government (Song et al., 2017). Only a stable government can provide sustainable political policies to develop an efficient HCWM system during the COVID-19 outbreak (Zorpas, 2020; Rothan and Byrareddy, 2020). As per Aung et al. (2019), Government facilities are full of deficiencies in HCWM practices. Hence, the worldwide governments needs to come up with the policies on the collection and segregation of the infectious wastes coming from the COVID-19 patients and channelize separately from the regular wastes to the disposal centers.

Hence, the following dimensions have been considered in the present study for configuring the role of political sustainability in HCWM: i) Separate regulatory framework for HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak; ii) PPP model for handling HCW during the COVID-19 outbreak; iii) Financial subsidies to HCW handlers; iv) Policies on promoting R&D in HCWM.

2.2.2. Economical dimensions

Stringent economic policies are the backbone of the sustainable HCWM system (Thakur and Ramesh, 2016). Literature has shown the empirical evidence that with increased investments/costs, the effectiveness of the HCWM has improved, which has lead to a safe environment for healthcare workers and economic sustainability (Caniato et al., 2015; Bennett, 2013; Podein and Hernke, 2010). As per Caniato et al. (2015), the world has now to shift the focus on greening their healthcare services, including HCWM, while targeting the economic sustainability in the healthcare system during this COVID-19 outbreak. Hence, to fight against the epidemic, the Government should intervene with the investment policies in the development of a sustainable HCWM system like: PPP (public-private partnership) model, BOT (build-operate-transfer) projects, O&M (operate-maintenance) projects, SEZs (special economic zone) (Song et al., 2017). The investments done during the COVID-19 outbreak in any nation, will help in fighting the health outbreaks in the future also.

Therefore, the present study has identified the following dimensions under the economic sustainability of HCWM: i) Government investment policies during COVID-19 outbreak; ii) Relaxed tax structure during disease outbreaks; iii) HCW disposal/treatment costs.

2.2.3. Social dimensions

The quantity of HCW has increased at an unprecedented rate due to the significant part coming out from the temporary built COVID-19 healthcare facilities (World Health Organization, 2020). The escalating number of COVID-19 patients are resulting in a higher quantity of infectious wastes daily. But, the HCW treatment facilities are limited with their disposal capacity, which is restricting the society to fight against the COVID-19 outbreak (Calma, 2020; Song et al., 2017). The Indian media has also reported various incidents of open dumping of the infectious wastes (PPE kits, masks, gloves, face shields, etc.). This negligence can lead to the spread of infection to the whole society through community displacements and social disturbances (Sun et al., 2020). World Health Organization (2020) has also pointed out that the poor awareness about the disposable items to be used during the COVID-19 outbreak, is a significant threat to society. Therefore, the concerned Government should educate the people about the handling of infectious wastes coming from the infected as well as non-infected people.

Hence, to ensure the social well-being during the COVID-19 outbreak, the following sustainable dimensions of HCWM have been considered in the present study: i) Community displacements and disturbances during the COVID-19 outbreak; ii) Social awareness about infectious HCW iii) Compensation for the local community.

2.2.4. Technological dimensions

The special treatment capacity to dispose of the HCW during the COVID-19 outbreak, equipped with the latest technologies, should be developed depending upon the local requirements, Governments’ guidelines, technical inputs, and experts’ opinions (Caniato et al., 2015). The tracking systems should be designed to trace every single bag of HCW coming out of COVID-19 patients’ treatment starting from the generation, collection, transportation and till the final disposal (Wang et al., 2020; Caniato et al., 2015). Also, the frequent and regular sanitization of the workplace should be done by using innovative contact-free techniques like: using drones, contactless sanitization machines, etc.

The following technological dimensions have been considered for sustainable HCWM during COVID-19 outbreak: i) Latest incineration technology to treat infectious HCW; ii) Tracking based supply chain (collection, storage and transportation) of HCW; iii) Regular sanitization of the contact points.

2.2.5. Environmental dimensions

The adverse impact on the environment due to the used infectious disposable items coming out from the treatment of COVID-19 patients, has to be considered to build up a sustainable HCWM system. In the recent past, due to the emerging environmental contamination problems, the sustainable ecological policy has been the primary concern worldwide, including India (Ferronato and Torretta, 2019). The open burnings and the incineration of the HCWs lead to the emissions of harmful gases to the environment (Aung et al., 2019). One study conducted in India, Vietnam, Canbodia and Philippines, have shown that contaminants like: polychlorinated dibenzofurans, polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins, and polychlorinated biphenyls were detected in the land nearby the ash and other left-outs’ dumping sites (Ferronato and Torretta, 2019; Minh et al., 2003). As per the study conducted on the assessment of groundwater quality in Tamilnadu, India, chromium level of up to 275 mg/L was found, which is 1000 times higher than WHO’s recommendations for safe drinking water (Rao et al., 2011). The higher concentration of heavy metals like Cd, Cr and Mn in the groundwater due to leachate is adversely affecting the nearby society and environment (Ferronato and Torretta, 2019). Another study conducted in Tiruchirappalli, India, the open dumping of the solid wastes has increased the lead and cadmium 5 and 11 times higher than the standard limits (Kanmani and Gandhimathi, 2013).

Therefore, in the present study, the following dimensions of the sustainable environment for managing HCW during COVID-19 outbreak have been included: i) Modified environmental policy for fighting against COVID-19 outbreak; ii) Effluents and emissions control at treatment sites.

2.2.6. Legal dimensions

Although, the existing legislations have the provisions for handling the infectious wastes, but, sudden COVID-19 outbreak has posed many threats in terms of extra infectious wastes coming out from the infected people. In the existing legal framework, there is a lack of special attention to the handling of disposable medical items and other general wastes generated from the COVID-19 hospitals. Earlier, which was considered the general waste, is now should be treated as the infectious wastes as it might be contaminated with the coronavirus (WHO, 2020). Hence, separate legal policies need to be defined in order to handle and treat the infectious wastes more effectively (Wang et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2020). Therefore, the present study has considered the following legal dimensions to ensure the sustainable HCWM system during COVID-19 outbreak: i) developing separate environmental policy for COVID-19 hospitals; ii) Compliance of environmental laws.

2.3. Literature review on the solution methodology

To target the above objectives, the PESTEL analysis has been integrated with TISM and fuzzy-MICMAC approach. To understand the nature of any industry, it is essential to explore the macro-environment surrounding that industry and PESTEL analysis is instrumental in defining the role of the macro-environment in handling the HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak (Pan et al., 2019; Mkude and Wimmer, 2015). After identifying the PESTEL dimensions, the hierarchical as well as non-hierarchical interrelationships among these dimensions have been explored using TISM (Zhao et al., 2020; Zorpas, 2020). TISM framework will facilitate the hospitals’ administration and waste handlers to pinpointing the short-term and long-term objectives for managing the HCW efficiently during the COVID-19 outbreak (Raut et al., 2018). The present study also utilizes the fuzzy-MICMAC approach to highlight the critical success factors of sustainable HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak (Thakur and Ramesh, 2016). Table 2 gives an overview of some of the applications of PESTEL, TISM and MICMAC methodologies to explore the macro-environment dimensions and their interrelationships in various industries.

Table 2.

Applications of PESTEL and TISM-MICMAC methodologies.

| Sources | Applications |

|---|---|

| Zorpas (2020) | Developing a strategy for waste management using SWOT-PESTEL analysis. |

| Lakshmi Priyadarsini and Suresh (2020) | TISM-MICMAC approach for handling COVID-19 pandemic. |

| Zhao et al. (2020) | Analyzed risk in the agri-food supply chain using TISM-MICMAC methodology. |

| Shankar et al. (2019) | Development of dedicated freight corridors using TISM-MICMAC framework. |

| Kumar et al. (2019) | TISM-Fuzzy MICMAC approach for selecting a city for smart city transformation in India. |

| Mishra et al. (2019) | Efficient management of international manufacturing network under circular economy using SWOT-PESTEL-ISM-MICMAC framework. |

| Pan et al. (2019) | PESTEL analysis of the construction industry for enhancing productivity. |

| Turkyilmaz et al. (2019) | Construction and demolition waste management model using PESTEL |

| Raut et al. (2018) | Analyzed the barriers to implementing sustainable practices using TISM and MICMAC approach. |

| Song et al. (2017) | PESTEL analysis of waste to energy industry in China. |

| Thakur and Anbanandam (2016) | Analyzed the barriers of implementing HCWM practices using ISM and fuzzy-MICMAC analysis. |

2.4. Research gaps and highlights

The COVID-19 outbreak has come out as a significant threat to the whole world, hence, maintaining hygiene within the hospitals and in the societies, are the primary responsibilities of the administration (Yu et al., 2020). Therefore, managing the infectious HCWs generating from various COVID-19 treatment centers, is the major challenge. Till now, many studies have been targeted on generation rates of HCW, treatment of infectious wastes, collection and transportation of HCW, optimization of treatment costs, etc. (Saeidi-Mobarakeh et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2020; Budak and Ustundag, 2017; Shi et al., 2009) but, focussing on developing the sustainable HCWM during COVID-19 outbreak is the unique contribution of the present study. The literature lacks studies on exploring the macro-environment surrounding the HCWM system and the interrelationships among the factors affecting the sustainable handling of infectious wastes. The present study tries to bridge the above research gaps and contributes to the knowledge body by:

-

•

Identifying the PESTEL (political, economic, social, technological, environmental, and legal) dimensions of sustainable HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak (shown in Table 1 ).

-

•

Exploring the hierarchical and non-hierarchical interactions among the PESTEL dimensions to develop sustainable HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak (see Section 4.3).

-

•

TISM-MICMAC analysis will help in analyzing the driving and dependence power of each PESTEL dimension, which will help the administration, to develop their strategic as well operational planning (see Section 4.4).

-

•

The implications for the hospitals’ managers and waste treatment facilities have been suggested to develop the HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak (highlighted in 5.1).

Table 1.

PESTEL dimensions to sustainable HCWM during COVID-19 outbreak.

| PESTEL dimensions | Factors | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| POL (Political) | Separate regulatory framework for HCWM during COVID-19 outbreak (POL 1) | Regulatory framework will define the separate procedures and policies for handling the infectious wastes. | WHO (2020), Zorpas (2020) |

| PPP model for handling HCW during COVID-19 outbreak (POL 2) | PPP model will help in setting up a quick response HCWM system and infrastructure in the COVID-19 hospitals. | Experts’ contribution | |

| Financial subsidies to HCW handlers (POL 3) | During the outbreak emergency period, the Government may think of special financial policies to promote the waste handling industry. | Rothan and Byrareddy (2020), Mkude and Wimmer (2015) | |

| Policies on promoting R&D in HCWM (POL 4) | Government should come up with more R&D schemes to promote research in the HCWM filed during the COVID-19 outbreak for developing a sustainable and safer environment. | Zorpas (2020), Rothan and Byrareddy (2020) | |

| ECO (Economical) | Government investment policies during COVID-19 outbreak (ECO 1) | Government should intervene with the new investment policies separately for urban and rural areas. | Caniato et al. (2015), Bennett (2013), |

| Relaxed tax structure during disease outbreaks (ECO 2) | Relaxed tax structure will help the HCW handlers to set up new facilities and import the latest technologies to treat the infectious wastes with minimum carbon prints. | Mkude and Wimmer (2015), Podein and Hernke (2010) | |

| HCW treatment costs (ECO 3) | Setting up the common bio-medical waste treatment facility for all the hospitals in a particular radius will help in achieving the economies of scale. | Caniato et al. (2015), Thakur and Ramesh (2016) | |

| SOC (Social) | Community displacements and disturbances during COVID-19 outbreak (SOC 1) | COVID-19 outbreak has forced many people to leave their working place due to shut down and come back to their villages, which has lead to the spread of coronavirus in rural areas also. | Sun et al. (2020), Calma (2020), Song et al. (2017) |

| Social awareness about infectious HCW (SOC 2) | Social awareness will encourage infected people to keep their contaminated wastes separate from the regular ones. | WHO (2020), Calma (2020), Windfeld and Brooks (2015) | |

| Compensation for the local community (SOC 3) | The continuous pollution emissions from the waste treatment facilities, should be compensated with some CSR activities for the local community. | Experts’ contribution | |

| TEC (Technological) | Latest incineration technology to treat infectious HCW (TEC 1) | Advanced incineration technologies will help in reducing the carbon footprints and also the left-outs contaminants will be very less. | Thakur and Ramesh (2016), Caniato et al. (2015) |

| Tracking based supply chain (collection, storage and transportation) of HCW (TEC 2) | Deploying the tracking system in the bags carrying COVID-19 infected wastes, will ensure the proper records maintaining and safe handling of HCW till the final disposal. | Wang et al. (2020), Caniato et al. (2015) | |

| Regular sanitization of the contact points (TEC 3) | Regular sanitization of the workplace will stop the spread of the infection to the local community. | Experts’ contribution | |

| ENV (Environmental) | Modified environmental policy for fighting against COVID-19 outbreak (ENV 1) | Modified environmental guidelines issued for the wastes treatment facilities and COVID-19 hospitals, will ensure sustainable environmental development. | Ferronato and Torretta (2019), Rao et al. (2011) |

| Effluents and emissions control at treatment sites (ENV 2) | Byproducts coming out of the treatment facilities should be addressed properly by safe dumping after chemical disinfection. | Kanmani and Gandhimathi (2013), Minh et al. (2003) | |

| LEG (Legal) | Developing legal policy for COVID-19 hospitals (LEG 1) | Legislation framework should be developed on the working of all the establishments dealing with the COVID-19 outbreak. | Wang et al. (2020), Yu et al. (2020) |

| Compliance of environmental laws (LEG 2) | Meeting the environmental obligations while fighting against the COVID-19 outbreak will ensure the sustainable HCWM system. | WHO (2020) |

3. Research methods

Integrating PESTEL with TISM and fuzzy-MICMAC is the novel methodological approach in the present study. Also, the application of PESTEL analysis in developing sustainable HCWM is the uniqueness of the present study. These techniques have been combined for the following reasons: firstly, PESTEL analysis being a multifaceted approach, helps in capturing the strategic forces present in the macro-environment and supports the decision-making in the organization (Pan et al., 2019; Song et al., 2017). Secondly, PESTEL analysis is a structured approach to identify the macro-environmental factors, which can affect the particular industry (Sandberg et al., 2016). Thirdly, the hierarchical as well as non-hierarchical relationships among the identified PESTEL factors of sustainable HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak, can be explored using the TISM methodology, which will facilitate the hospitals’ management for real-life decisions (Thakur and Ramesh, 2016). Fourthly, the fuzzy-MICMAC analysis combined with TISM will help in capturing the relationships among elements more precisely than conventional MICMAC (Zhao et al., 2020).

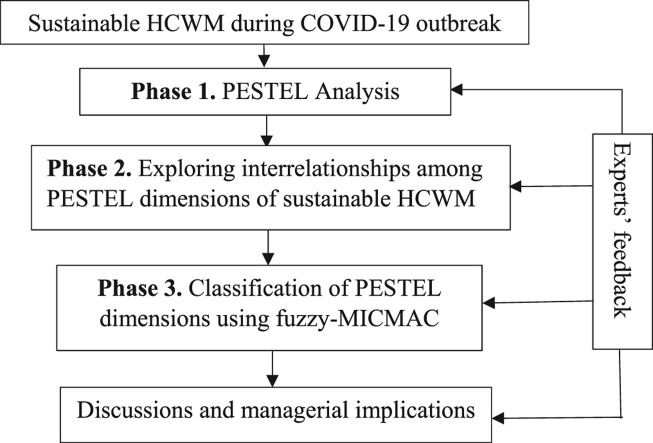

Hence, considering the synergetic effects of combined PESTEL-TISM and fuzzy-MICMAC, the present study has used these tools to analyze the sustainable dimensions of HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak. Fig. 1 represents the research framework opted for the present study, where the factors of sustainable HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak, have analyzed in three phases:

Fig. 1.

Proposed research framework for PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM.

Phase 1: PESTEL analysis: Identifying the factors to sustainable HCWM during coronavirus pandemic.

In the first part of the study, to understand the HCWM industry’s macro-environment, the PESTEL framework has been used (Mkude and Wimmer, 2015; Yüksel, 2012). Here, PESTEL analysis will explore the various political, economic, social, technological, environmental, and legal dimensions which will affect the implementation of sustainable HCWM system within the hospitals and at the waste treatment facilities (Song et al., 2017; Mkude and Wimmer, 2015).

Phase 2: TISM methodology: Exploring the interrelationships among PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM.

As per Yüksel (2012), for any industry’s strategic planning, it is crucial to find the interrelationships and interdependencies among the surrounding PESTEL dimensions. Therefore, TISM methodology has been opted for analyzing the contextual relationships among the various PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM. TISM is a very useful tool in handling the complex problems, by taking the experts’ inputs and developing an operational framework for a better understanding of the challenges and elements involved in sustainable HCWM (Sindhu et al., 2016). The present study includes the following steps of TISM methodology:

Step 1. Defining elements of sustainable HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak

Step 2. Defining the contextual relationships among the PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM

Here, the contextual relationships among the various PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM have been studied. For the present study, the following structure for defining the contextual relationships among various PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM has been considered: “Whether one PESTEL dimension triggers/influences the other one?” (Zhao et al., 2020; Hasan et al., 2019).

Step 3. Interpretation of contextual relationships

This step generates the information for theory building, as TISM not only defines the nature of the relationship, but also mentions the cause of the relationship (Hasan et al., 2019). This step will extract the knowledge-base by asking the experts: “How the one PESTEL dimension triggers/influences the other one?” The opinions about the established relationships among dimensions have been collected from the experts through structured interviews (Zhao et al., 2020; Hasan et al., 2019; Jena et al., 2017).

Step 4. Interpretive logic of pair-wise comparisons

Here, the ‘interpretive logic-knowledge base’ has been developed for all the pair-wise comparisons for which the particular comparison cell entry is ‘yes’ (Zhao et al., 2020).

Step 5. Prepare reachability matrix and conduct the transitivity checks

For preparing the reachability matrix, the ‘Y’ in the pair-wise comparison matrix is replaced by ‘1’ and ‘N’ is replaced by ‘0’. The same reachability matrix is observed for any transitivity conditions. The transitivity means if ‘A’ influences ‘B’, and ‘B’ further influences ‘C’, then ‘A’ necessarily influences ‘C’ and the corresponding cell entry for A-C should also be ‘1’.Step 6. Partitioning the PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM

Here, the reachability sets and antecedent sets for all the PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM are defined as discussed in by Jena et al. (2017). Thereafter, a series of iterations are run to identify all the elements at different levels in the hierarchical structure, as explained by Zhao et al. (2020) and Thakur and Anbanandam (2017).

Step 7. Developing digraph

Here, all the direct relationships among the PESTEL dimensions are represented in the form of a directed digraph. Digraph also retains the significant transitive relations.

Step 8. Preparing the interpretive matrix

The interpretive matrix is prepared by providing the explanation for each cell, where the entry is ‘1’ to form the developed knowledge-base.

Step 9. Developing the TISM model

The directed graph and interpretive matrix have been used to develop the final TISM model. All the direct and transitive links in the TISM hierarchy have been interpreted by adding a brief explanation on the directed link itself.

Phase 3: Fuzzy-MICMAC analysis: classification of PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM

TISM hierarchical digraph depicts the relationships among the various PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak and take the inputs values like: ‘1’ (for relationship existence) and ‘0’ (for no relationship) (Zhao et al., 2020; Hasan et al., 2019). Irrespective of the strength of the relationships among various PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM, the TISM digraph gives equal weightage (‘1’) to all the direct as well as the transitive links. Hence, to avoid this limitation of TISM and include more sensitivity analysis in the relationships among various dimensions, fuzzy-MICMAC has been used for the present study (Thakur and Ramesh, 2016). In the present study, the fuzzy-MICMAC analysis includes the following three steps:

Step 1. Preparing binary direct relationship matrix (BDRM).

The BDRM is prepared by converting the diagonal entries in the final reachability matrix into 0. The BDRM matrix also ignores the transitivity relationships.

Step 2.Preparing a fuzzy direct relationship matrix (FDRM).

Then, the BDRM matrix has been converted into FDRM by replacing all the binary relationships by the fuzzy values as defined by the experts. The experts’ inputs on the strength of relationships among various PESTEL dimensions, are defined on the fuzzy scale ranging from 0 to 1 (0 - no, 0.1 - negligible, 0.3 – low, 0.5 - medium, 0.7 – high, 0.9 - very high, 1 - full).

Step 3. Computing stabilized fuzzy-MICMAC matrix.

Here, the FDRM is multiplied repeatedly until the driving and dependence powers of the dimensions are stabilized. The fuzzy set theory says that if fuzzy matrices are multiplied, then the resultant matrix will also be the fuzzy matrix only (Zhao et al., 2020). The following rule has been used to multiply the fuzzy matrices:

| (1) |

where, , ,

In the present study, MATLAB software has been used to calculate the stabilized FDRM. Further, the stabilized FDRM is used to calculate the driving and dependence powers of each dimension of sustainable HCWM by taking the corresponding dimension’s row sum and column’s sum, respectively in the FDRM matrix.

4. Application of proposed research framework

4.1. Case of Indian HCWM industry

In India, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEF), in collaboration with State Pollution Control Boards of different states (SPCB) regulates the safe disposal and recycling of the wastes (Thakur and Ramesh, 2017). National Environment Policy, 2006 has set up various measures for handling infectious wastes coming out from the healthcare facilities. For the first time, the Ministry of Environment & Forest (MoEF) introduced the biomedical waste rules in July 1998, which were further revised from time to time in the subsequent years: 2000, 2003, 2011 and 2016 (Datta et al., 2018). The latest amendments in the BMW rules, published in March 2016, where more focus was given to storage, collection, transportation, and safe disposal of the infectious wastes to protect the environment (Datta et al., 2018).

As per the latest report on BMW Management rule, 2016 published in Gazette of India (March 2016), a total of 1,31,837 healthcare facilities in India are using the common bio-medical waste treatment facilities, while 21,870 hospitals are using on-site facilities to treat their HCW. In India, a total number of 198 common bio-medical waste treatment facilities daily process more than 447 tons of HCW. Still, approximately 40 tons per day is going untreated to the environment, which is very harmful. As per the report published on health economics in The Economic Times (2018), the HCWM market will touch USD 13.62 billion by 2025 and the bio-medical waste market will expand with a compound annual growth rate of 8.14%.

4.2. Data collection

For recording the contextual relationships among various PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM, it is necessary to include the doyens from the related domain expertise (Zhao et al., 2020). Therefore, the present study also includes the two experts from the COVID-19 treatment hospitals. A total of six experts (as shown in Table 3 ) have been invited to develop the relationship matrix, which is well supported by the literature for group decision-making (Zhao et al., 2020; Thakur and Mangla, 2019; Jena et al., 2017). The structured brainstorming sessions through ‘google meet’ online digital platform were conducted with all the experts. After so many revisions and discussions, the contextual relationships among dimensions of sustainable HCWM were recorded (Vinodh and Asokan, 2018).

Table 3.

Experts’ profile.

| Organization | Designation | Operational responsibilities | Experience (years) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital | Senior superintendent (COVID center now) | Hospital’s management, wastes collection and outsourcing, handling staff and other operational issues | 23 |

| Hospital | Superintendent (COVID center now) | Fulfilling statuary requirements of hospitals, implementing routine systems and procedures. | 17 |

| CBWTFa | Operations manager | Regular collection and disposal of wastes from various hospitals, maintaining records of wastes generated, conducting training programs for staff. | 13 |

| CBWTFa | Chairman | Coordinating operations of five different CBMWTFs and various hospitals coming under the radius. | 37 |

| State regulatory body | General secretary | Ensuring the implementation of BMW handling rules, regular audits, compiling records. | 22 |

| Academics | Professor | Experts in healthcare management, supply chain management, operations management. | 16 |

Common bio-medical waste treatment facility.

4.3. TISM model development of PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM during COVID-19 outbreak

In the present study, a total of 17 dimensions of sustainable HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak have been identified through the structured PESTEL analysis (shown in Table 1). Thereafter, the contextual relationships (‘Y’ for yes and ‘N’ for no relationship) among 17 PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak have been defined (as shown in Appendix 1). For developing the knowledge base, six experts (shown in Table 3), who are responsible for managerial and technical decision-making on implementing HCWM practices, have been involved through the structured interviews for depicting the established relationships. A sample interpretive logic-knowledge base for PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak is shown in Appendix 2. In the present study, there are a total of 272 (that is 17∗17-17 = 272) rows for 17 PESTEL dimensions in the developed knowledge base for implementing a sustainable HCWM system during the COVID-19 outbreak (Zhao et al., 2020). To compute the final reachability matrix, the transitivity conditions are removed from the whole pair-wise comparison matrix by replacing the cell entry by ‘1’ and also the explanation is given for all the significant transitive positions in the ‘interpretive logic-knowledge base’. The final reachability matrix, including all the transitive positions, has been shown in Table 4 . Then, the reachability sets and antecedent sets for all the PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM are defined from the final reachability matrix and iterations will be run until all the 17 PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM have been placed in the hierarchical digraph (shown in Appendix 3). This step has placed all the 17 PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM into a hierarchy of six levels.

Table 4.

Final reachability matrix of PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM.

| Dimensions | POL 1 | POL 2 | POL 3 | POL 4 | ECO 1 | ECO 2 | ECO 3 | SOC 1 | SOC 2 | SOC 3 | TEC 1 | TEC 2 | TEC 3 | ENV 1 | ENV 2 | LEG 1 | LEG 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POL 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1∗ | 1∗ | 1∗ | 0 | 1∗ | 1∗ | 0 | 1∗ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| POL 2 | 0 | 1 | 1∗ | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1∗ | 0 | 0 | 1∗ | 1 | 1∗ | 0 | 0 | 1∗ | 0 | 1∗ |

| POL 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1∗ | 0 | 0 | 1∗ | 1∗ | 1∗ | 0 | 0 | 1∗ | 0 | 1∗ |

| POL 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1∗ | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1∗ |

| ECO 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1∗ | 1∗ | 1∗ | 1 | 1 | 1∗ | 1∗ | 0 | 1∗ | 0 | 1∗ |

| ECO 2 | 0 | 1 | 1∗ | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1∗ | 1∗ | 0 | 1∗ | 1 | 1∗ | 0 | 0 | 1∗ | 0 | 1∗ |

| ECO 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1∗ | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1∗ | 0 | 0 | 1∗ | 0 | 0 |

| SOC 1 | 0 | 1∗ | 1∗ | 1∗ | 0 | 1∗ | 1∗ | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1∗ | 1∗ | 0 | 0 | 1∗ | 0 | 1∗ |

| SOC 2 | 0 | 1∗ | 1∗ | 1∗ | 1∗ | 1∗ | 1∗ | 1 | 1 | 1∗ | 1∗ | 1∗ | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| SOC 3 | 0 | 1∗ | 1∗ | 1∗ | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1∗ | 1∗ | 0 | 0 | 1∗ | 0 | 1∗ |

| TEC 1 | 0 | 1∗ | 1∗ | 1∗ | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1∗ | 1 | 1∗ | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1∗ |

| TEC 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1∗ | 0 | 0 | 1∗ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| TEC 3 | 0 | 1∗ | 1∗ | 1∗ | 1∗ | 1∗ | 1 | 1∗ | 1∗ | 1∗ | 1∗ | 1∗ | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| ENV 1 | 1 | 1∗ | 0 | 1∗ | 1∗ | 0 | 1∗ | 1∗ | 1∗ | 1∗ | 1∗ | 1∗ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| ENV 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| LEG 1 | 1 | 1∗ | 1∗ | 1∗ | 1∗ | 0 | 1∗ | 1∗ | 1∗ | 1∗ | 0 | 1∗ | 1 | 1∗ | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| LEG 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1∗ | 0 | 1 |

1∗ represents reachability condition.

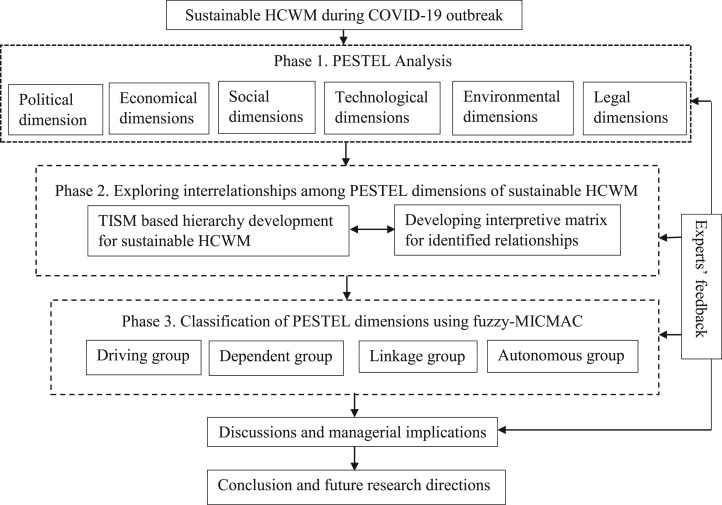

For pictorial representation, all the 17 PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak have been placed in the form of a directed graph, highlighting the direct relationships as per the final reachability matrix. Only those transitive relations, which are significant and whose interpretation is essential for implementing sustainable HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak, have been retained in the digraph highlighted by dotted lines (Hasan et al., 2019; Jena et al., 2017). Dotted lines in the digraph show the significant transitive links and all other plane lines represent the direct links between PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM (as shown in Fig. 2 ). Thereafter, the binary interpretive matrix for 17 PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM, has been prepared by converting all the direct relationships as well as the significant transitive links into ‘1’ (Zhao et al., 2020). Appendix 4 represents the ‘interpretive logic-knowledge base’ for all the interactions among the PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM. Finally, from the directed graph and interpretive matrix, the TISM model for 17 PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak, has been shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

TISM model for PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM during COVID-19 outbreak.

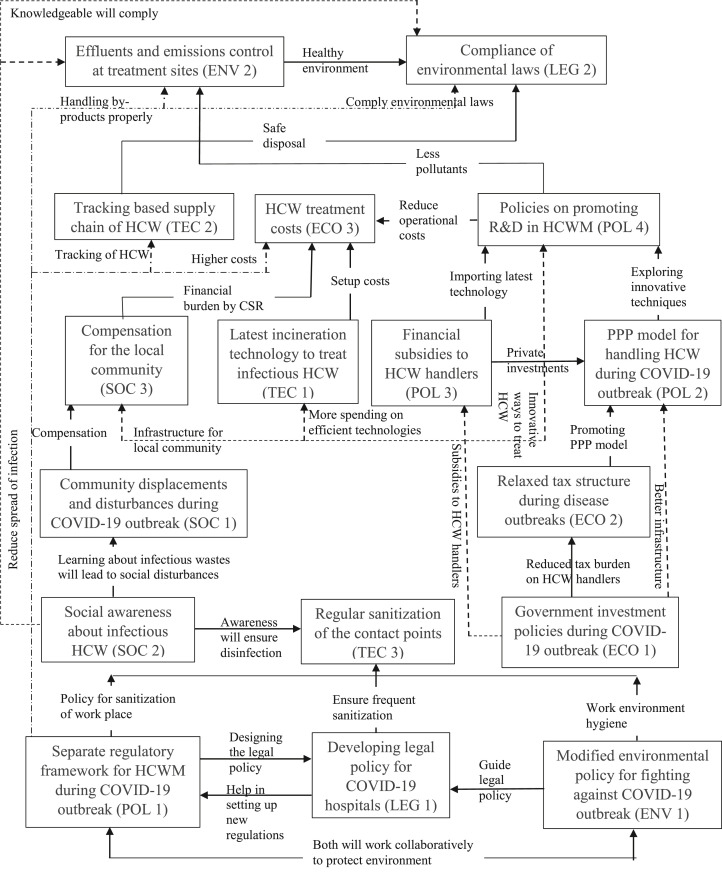

4.4. Classifying PESTEL dimensions using fuzzy-MICMAC analysis

Fuzzy-MICMAC analysis divides all the 17 PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM into four categories depending upon their driving and dependence powers in the overall system: autonomous group, dependent group, linkage group and independent group. First of all, the BDRM for the PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM is prepared by converting the diagonal entries of the final reachability matrix (shown in Table 4. Then, the BDRM matrix has been converted into FDRM matrix by including the fuzzy values to depict the strength of relationships among the PESTEL dimensions (shown in Appendix 5). By applying Eqn. (1), the FDRM is converted into a stabilized fuzzy-MICMAC matrix. The final ranking of all the 17 PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM has been calculated using driving and dependence powers (as shown in Table 5 ).

Table 5.

MICMAC stabilized matrix for PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM.

| Dimensions | POL 1 | POL 2 | POL 3 | POL 4 | ECO 1 | ECO 2 | ECO 3 | SOC 1 | SOC 2 | SOC 3 | TEC 1 | TEC 2 | TEC 3 | ENV 1 | ENV 2 | LEG 1 | LEG 2 | Driving Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POL 1 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 5.6 |

| POL 2 | 0 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.9 | 0 | 0 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.9 | 4.1 |

| POL 3 | 0 | 0 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.7 | 4.6 |

| POL 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0.8 |

| ECO 1 | 0 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 | 4.1 |

| ECO 2 | 0 | 0 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.3 | 3.6 |

| ECO 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SOC 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.9 |

| SOC 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.7 | 2.6 |

| SOC 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.7 |

| TEC 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 1.2 |

| TEC 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| TEC 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 2.6 |

| ENV 1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 5.6 |

| ENV 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.7 |

| LEG 1 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 5.8 |

| LEG 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dependence power | 1.7 | 3.1 | 3.8 | 4.5 | 0 | 0 | 4.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 3.6 | 2.9 | 2 | 1.3 | 5.4 | 2.2 | 5.8 |

Fig. 3 represents the 17 PESTEL dimensions on a two-dimensional graph: dependence power and driving power. Fuzzy-MICMAC analysis has resulted in the following four classifications of the 17 PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak: Cluster 1 (autonomous group); Cluster 2 (dependent group); Cluster 3 (linkage group) and Cluster 4 (independent group).

Fig. 3.

Classifying PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM.

5. Results and discussions

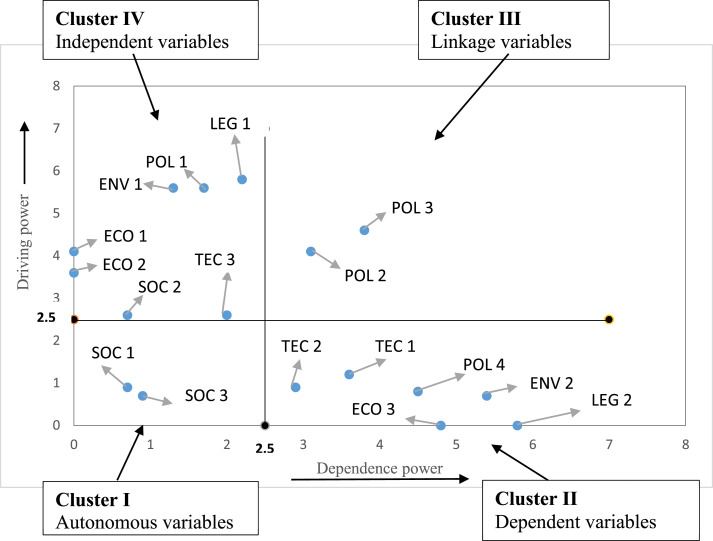

The healthcare organizations and pollution control boards need to adopt sustainable HCWM practices, especially during the COVID-19 outbreak, to reduce the virus’s spread and protect society from the infection. The investigation into the first research question raised in the present study (What are the PESTEL factors, which can affect the decision-making and strategy development for handling HCW dusring COVID-19 outbreak?), explored the macro-environment surrounding the sustainable HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak, using PESTEL analysis. The PESTEL framework resulted in a total of 17 dimensions (shown in Table 1), which may affect the decision-making for handling the infectious HCW suring COVID-19 outbreak. The examination of the second research question (how can the identified factors be arranged in the overall framework?), requires the application of the TISM methodology to develop the relationships hierarchy among the PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak. TISM methodology resulted in six levels hierarchy of interrelationships among the 17 PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM (shown in Fig. 2). The investigation into the last research question (how can these factors be classified as per their importance for improving the overall performance of the HCWM system?) sought the application of fuzzy-MICMAC analysis, which divided all the 17 PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM into four groups (as shown in Fig. 3). The key findings of the fuzzy-MICMAC analysis are as follows:

Independent/Driving group: In the present study, the following dimensions of sustainable HCWM are having the weak dependence power and strong driving power: ‘separate regulatory framework for HCWM during COVID-19 outbreak (POL 1)’; ‘government investment policies during COVID-19 outbreak (ECO 1)’; ‘relaxed tax structure during disease outbreaks (ECO 2)’; ‘social awareness about infectious HCW (SOC 2)’; ‘modified environmental policy for fighting against COVID-19 outbreak (ENV 1)’; ‘regular sanitization of the contact points (TEC 3)’ and ‘developing legal policy for COVID-19 hospitals (LEG 1)’. These dimensions are placed at the bottom of the hierarchy and influence all other dimensions above them. These independent dimensions feed as the inputs for developing the sustainable HCWM system during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Dependent group: The following PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM have been identified as a dependent group: ‘policies on promoting R&D in HCWM (POL 4)’; ‘HCW treatment costs (ECO 3)’; ‘latest incineration technology to treat infectious HCW (TEC 1)’; ‘tracking based supply chain of HCW (TEC 2)’; ‘effluents and emissions control at treatment sites (ENV 2)’; and ‘compliance of environmental laws (LEG 2)’. These dimensions are having low driving power and very high dependence power. Hence, for ensuring sustainable HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak, the implementation of dependent group dimensions requires all the other dimensions in the system to enhance their performance.

Linkage group: The following PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM are having very high dependence as well as driving power and have been placed in the linkage group: ‘PPP model for handling HCW during COVID-19 outbreak (POL 2)’; and ‘financial subsidies to HCW handlers (POL 3)’. These dimensions of sustainable HCWM are most unstable as they affect the other dimensions in the system and also get affected.

Autonomous group: Dimensions falling under this group will be having very low driving and dependence power. In the present study, the following PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM have been in the autonomous group: ‘community displacements and disturbances during COVID-19 outbreak (SOC 1)’; and ‘compensation for the local community (SOC 3)’. Hence, these have no influence on the development of a sustainable HCWM system during the COVID-19 outbreak.

TISM model has placed the dimensions: a separate regulatory framework for HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak (POL 1); developing legal policy for COVID-19 hospitals (LEG 1); and modified environmental policy for fighting against the COVID-19 outbreak (ENV 1) at the base of the hierarchy, showing the highest driving/influencing power to the whole HCWM system. Fuzzy-MICMAC analysis has also validated that these three factors (POL 1, LEG 1, ENV 1) are the essential pillars for setting up the sustainable HCWM system during the COVID-19 outbreak. The policy framework developed for these three levels: political, legal and environmental will have the highest impact on managing the HCW during the COVID-19 outbreak situation (Klemeš et al., 2020; Windfeld and Brooks, 2015). These guiding policies will ensure the regular sanitization of the contact points at the COVID-19 hospitals and the HCW treatment facilities. The results support the recent study conducted by Serge Kubanza and Simatele (2020), where they mentioned that institutional failure for developing strict rules and regulations is a significant threat to waste management. Social awareness about the infectious HCW coming out from the virus-infected people, is another important driver for implementing the efficient HCWM system during health outbreak. The lack of awareness among the people about handling the infected disposable items and poor education about handling the infectious wastes are the main hurdle for sustainable HCWM (World Health Organization, 2020; Windfeld and Brooks, 2015; Botelho, 2012). Pinzone et al. (2019) surveyed 260 healthcare professionals and concluded that the training and awareness programs on greening activities motivate them towards pro-environmental behaviors. Klemeš et al. (2020) added that not only techno-economic assessment is required to set up a sustainable waste management system, but, also the society has a significant role in managing the COVID-19 outbreak.

Government investment policies during the COVID-19 outbreak (ECO 1) are another strong driver identified in the HCWM system, which will help in promoting the HCWM sector with the latest technologies, financial subsidies and liberalized tax policies for HCW handlers. The relaxed tax structure during this pandemic and Government investment policies will enhance the PPP model for handling the infectious wastes during the health outbreaks and also develop a better infrastructure for infection free treatment of HCW. PPP model for handling HCW during COVID-19 outbreak (POL 2) and financial subsidies to HCW handlers (POL 3) dimensions have been placed in the middle of the TISM model and also fuzzy-MICMAC analysis has identified these two dimensions as the most important by placing them in the linkage group (Malek and Desai, 2019). These two dimensions will form the link between the various input and output dimensions in implementing a sustainable HCWM system. The worldwide governments need to focus more on these sensitive dimensions to set up sustainable HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak. The worldwide governments can make policies for promoting the private players for handling the HCW and also financial help to HCW handlers, which will help in importing the latest treatment technologies with minimum impact on the environment and also reducing the operational costs (Rothan and Byrareddy, 2020; Zorpas, 2020). The latest study conducted in China has shown that the COVID-19 outbreak has not only increased the amount of medical waste generated (from 40 tons/day to 240 tons/day), but also escalated the costs (from 14 USD/ton to 422 USD/ton) of treating the infectious medical wastes (Tang, 2020). Hence, the existing system for waste quality and quantity has to cope up with the extra burden due to the COVID-19 outbreak (Klemeš et al., 2020). Through the PPP model structure, the disposal capacity of the treatment facilities can be enhanced and the extra burden during the COVID-19 outbreak can be managed more efficiently.

Effluents and emissions control at treatment sites (ENV 2) and compliance of environmental laws (LEG 2) dimensions with the highest dependence power and being the ultimate objectives of the hospitals’ administration and HCW treatment facilities, have been placed at the top of the TISM hierarchy. Fuzzy-MICMAC analysis also validated the results through the empirical investigations and classified these dimensions into the dependent group by keeping them on the extreme right corner of the second quadrant. The hospitals’ administration should closely track these outputs to implement sustainable HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak. As per Klemeš et al. (2020), the traditional incineration technology coupled with waste heat energy recovery, can minimize the environmental impacts of the waste emissions. Mishra et al. (2020) recently revealed in their study that steam sterilization is the best method for safe disposal HCW. Moreover, the tracking based supply chain of HCW (TEC 2) should be designed to track the movement of each bag of HCW down to the supply chain from hospitals to the waste treatment facilities.

The present study has resulted that dimensions like: ‘compensation for the local community’ and ‘community displacements and disturbances during COVID-19 outbreak’ do not have much impact on sustainable HCWM, as they are having very weak driving and dependence power. But, Sun et al. (2020) revealed that community movements and disturbances could spread the infection from one place to another. This community displacement may be due to the reason that people are losing their jobs because of shutting down and they are shifting to their villages.

5.1. Managerial implications

The present study has investigated the impactful PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak to develop the TISM based hierarchy. The identified PESTEL dimensions are constructive for the hospitals’ administration for handling their infectious wastes. The combined TISM-fuzzy MICMAC analysis presents the following insights for the managers:

-

•

The TISM digraph based on the interrelationships among the dimensions of sustainable HCWM, will assist the hospitals’ administration to understand the role of every PESTEL dimension for implementing the sustainable HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak.

-

•

The worldwide governments in collaboration with COVID-19 hospitals and HCW treatment facilities, can focus on the key areas (separate political framework, legal and environmental policies), which have been highlighted as the base of the TISM framework. The robust policy framework will guide the whole HCWM system during the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

•

The study findings suggest that immediate attention should be paid to the dimensions belonging to the driving group (like: regular sanitization of contact points, social awareness, governments’ investment policies, legal framework, environmental policy for fighting against COVID-19 outbreak).

-

•

The hospitals’ administration and waste treatment facilities should closely monitor the outcome dimensions like: effluent and emissions control at the HCW treatment sites and compliance of the environment protection laws. And also, the tracking system should be installed through the supply chain carrying infectious HCW from the COVID-19 treatment centers.

-

•

For theoretical implications, the study develops the TISM hierarchical structure of PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak, which will help in better understanding of the challenges and their impact on handling the infectious HCW during the COVID-19 outbreak

6. Conclusion

The present scenario of the COVID-19 outbreak demands serious attention from the healthcare practitioners and researchers to stop the spread of the infection to the whole society. Moreover, in developing countries like India, the HCWM industry is completely unorganized in rural areas compared to urban and semi-urban areas. During the lockdown period, most of the people working in the cities (industrial zones) shifted to their villages because of shutdown operations, which posed a massive challenge to the local administration and hospitals’ administration. Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to facilitate the hospitals’ managers in implementing sustainable HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak. The major findings of the study are as below:

-

•

The study applied a PESTEL analysis to identify the 17 dimensions of sustainable HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak under six main dimensions: political, economic, social, technological, environmental and legal.

-

•

The study adopts the TISM approach and revealed that the separate policy framework for targeting political, legal and environmental issues form the basis of the sustainable HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak.

-

•

Further, the application of fuzzy-MICMAC analysis determined the role of the individual dimension for the development of a sustainable HCWM system and identified the following strong drivers of sustainable HCWM: regular sanitization of contact points, social awareness, governments’ investment policies, legal framework, environmental policy for fighting against COVID-19 outbreak.

-

•

The study identified the following dimensions as the outcome variables for sustainable HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak: ‘effluent and emissions control at the HCW treatment sites’ and ‘compliance of the environment protection laws’.

The present study does have some limitations, which open further research directions:

-

•

Firstly, the study highlights the various dimensions targeting six main areas (political, economic, social, technological, environmental and legal) for implementing the sustainable HCWM during the COVID-19 outbreak, but the detailed action plan on every dimension for strategic planning has not been highlighted. Hence, further study can be conducted proposing the operational strategies for handling each aspect separately.

-

•

Secondly, the present study discusses the PESTEL dimensions for broad policy-making on HCWM for any nation, hence, future regional specific studies can be replicated for having a better understanding and implementation at the operational level. Conducting regional specific studies may add some more dimensions to the existing list.

-

•

Thirdly, only the qualitative inputs have been considered for representing the PESTEL dimensions of sustainable HCWM, which can be further validated by conducting the empirical study on a large scale by applying structural equation modeling (SEM).

-

•

Lastly, the TISM methodology investigates only the interrelationship between two elements without considering the direction (positive/negative) of influence. But, for the hospitals’ administration viewpoint, it is important to identify the direction of relationship to control the output dimensions (effluents and emissions control, and compliance of environmental laws).

Author contributions

Being the single author, the whole manuscript has been prepared and compiled by the corresponding author only.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Handling editor: Mingzhou Jin

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125562.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Abu-Qdais H.A., Al-Ghazo M.A., Al-Ghazo E.M. Statistical analysis and characteristics of hospital medical waste under novel Coronavirus outbreak. Global Journal of Environmental Science and Management. 2020;6:21–30. Special Issue (Covid-19)) [Google Scholar]

- Aung T.S., Luan S., Xu Q. Application of multi-criteria-decision approach for the analysis of medical waste management systems in Myanmar. J. Clean. Prod. 2019;222:733–745. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett C.C. Are we there yet? A journey of health reform in Australia. Med. J. Aust. 2013;199(4):251–255. doi: 10.5694/mja13.10839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermejo M., Rodríguez-Teijeiro J.D., Illera G., Barroso A., Vilà C., Walsh P.D. Ebola outbreak killed 5000 gorillas. Science. 2006;314(5805):1564. doi: 10.1126/science.1133105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botelho A. The impact of education and training on compliance behavior and waste generation in European private healthcare facilities. J. Environ. Manag. 2012;98:5–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budak A., Ustundag A. Reverse logistics optimisation for waste collection and disposal in health institutions: the case of Turkey. Int. J. Logistics Res. Appl. 2017;20(4):322–341. [Google Scholar]

- Calma J. 2020. The COVID-19 Pandemic Is Generating Tons of Medical Waste.https://www.theverge.com/2020/3/26/21194647/the-covid-19-pandemic-is-generating-tons-of-medical-waste [Google Scholar]

- Caniato M., Tudor T., Vaccari M. International governance structures for healthcare waste management: a systematic review of scientific literature. J. Environ. Manag. 2015;153:93–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin C.S., Sorenson J., Harris J.B., Robins W.P., Charles R.C., Jean-Charles R.R., et al. The origin of the Haitian cholera outbreak strain. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364(1):33–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coburn B.J., Wagner B.G., Blower S. Modeling influenza epidemics and pandemics: insights into the future of swine flu (H1N1) BMC Med. 2009;7(1):30. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-7-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta P., Mohi G.K., Chander J. Biomedical waste management in India: critical appraisal. J. Lab. Phys. 2018;10(1):6. doi: 10.4103/JLP.JLP_89_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong M.D., Simmons C.P., Thanh T.T., Hien V.M., Smith G.J., Chau T.N.B., Qui P.T. Fatal outcome of human influenza A (H5N1) is associated with high viral load and hypercytokinemia. Nat. Med. 2006;12(10):1203–1207. doi: 10.1038/nm1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy M.R., Chen T.H., Hancock W.T., Powers A.M., Kool J.L., Lanciotti R.S., et al. Zika virus outbreak on Yap Island, Federated States OF Micronesia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360(24):2536–2543. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ECDC . ECDC; 2020. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, Stockholm; Stockholm: 2020. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic: Increased Transmission in the EU/EEA and the UK – Seventh Update, 25 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ferronato N., Torretta V. Waste mismanagement in developing countries: a review of global issues. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2019;16(6):1060. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16061060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl M.A., Uttamchandani R.B., Daikos G.L., Poblete R.B., Moreno J.N., Reyes R.R., et al. An outbreak of tuberculosis caused by multiple-drug-resistant tubercle bacilli among patients with HIV infection. Ann. Intern. Med. 1992;117(3):177–183. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-3-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S., Boojh R., Mishra A., Chandra H. Rules and management of biomedical waste at Vivekananda Polyclinic: a case study. Waste Manag. 2009;29(2):812–819. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan Z., Dhir S., Dhir S. Modified total interpretive structural modelling (TISM) of asymmetric motives and its drivers in Indian bilateral CBJV. Benchmark Int. J. 2019;26(2):614–637. [Google Scholar]

- Jena J., Sidharth S., Thakur L.S., Pathak D.K., Pandey V.C. Total interpretive structural modeling (TISM): approach and application. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2017;14(2):162–181. [Google Scholar]

- Kanmani S., Gandhimathi R. Assessment of heavy metal contamination in soil due to leachate migration from an open dumping site. Appl. Water Sci. 2013;3(1):193–205. [Google Scholar]

- Klemeš J.J., Van Fan Y., Tan R.R., Jiang P. Minimising the present and future plastic waste, energy and environmental footprints related to COVID-19. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020;127:109883. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2020.109883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar H., Singh M.K., Gupta M.P. A policy framework for city eligibility analysis: TISM and fuzzy MICMAC-weighted approach to select a city for smart city transformation in India. Land Use Pol. 2019;82:375–390. [Google Scholar]

- Lakshmi Priyadarsini S., Suresh M. Factors influencing the epidemiological characteristics of pandemic COVID 19: a TISM approach. Int. J. Healthc. Manag. 2020;13(2):89–98. [Google Scholar]

- Malek J., Desai T.N. Interpretive structural modelling based analysis of sustainable manufacturing enablers. J. Clean. Prod. 2019;238:117996. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers L.A., Pourbohloul B., Newman M.E., Skowronski D.M., Brunham R.C. Network theory and SARS: predicting outbreak diversity. J. Theor. Biol. 2005;232(1):71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2004.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minh N.H., Minh T.B., Watanabe M., Kunisue T., Monirith I., Tanabe S., et al. Open dumping site in Asian developing countries: a potential source of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and polychlorinated dibenzofurans. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003;37(8):1493–1502. doi: 10.1021/es026078s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra A.R., Mardani A., Rani P., Zavadskas E.K. A novel EDAS approach on intuitionistic fuzzy set for assessment of healthcare waste disposal technology using new parametric divergence measures. J. Clean. Prod. 2020:122807. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra S., Singh S.P., Johansen J., Cheng Y., Farooq S. Evaluating indicators for international manufacturing network under circular economy. Manag. Decis. 2019;57(4):811–839. [Google Scholar]

- Mkude C.G., Wimmer M.A. 2015. Studying interdependencies of e-government challenges in Tanzania along a PESTEL analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Pan W., Chen L., Zhan W. PESTEL analysis of construction productivity enhancement strategies: a case study of three economies. J. Manag. Eng. 2019;35(1) [Google Scholar]

- Pinzone M., Guerci M., Lettieri E., Huisingh D. Effects of ‘green’ training on pro-environmental behaviors and job satisfaction: evidence from the Italian healthcare sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2019;226:221–232. [Google Scholar]

- Podein R.J., Hernke M.T. Integrating sustainability and health care. Prim. Care Clin. Off. Pract. 2010;37(1):137–147. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radke E.G., Gregory C.J., Kintziger K.W., Sauber-Schatz E.K., Hunsperger E.A., Gallagher G.R., et al. Dengue outbreak in key west, Florida, USA, 2009. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012;18(1):135. doi: 10.3201/eid1801.110130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao G.T., Rao V.G., Ranganathan K., Surinaidu L., Mahesh J., Ramesh G. Assessment of groundwater contamination from a hazardous dump site in Ranipet, Tamil Nadu, India. Hydrogeol. J. 2011;19(8):1587–1598. [Google Scholar]

- Raut R., Narkhede B.E., Gardas B.B., Luong H.T. An ISM approach for the barrier analysis in implementing sustainable practices: The Indian oil and gas sector. Benchmark.: Int. J. 2018;25(4):1245–1271. [Google Scholar]

- Rayor L.S. Dynamics of a plague outbreak in Gunnison’s prairie dog. J. Mammal. 1985;66(1):194–196. [Google Scholar]

- Rothan H.A., Byrareddy S.N. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. J. Autoimmun. 2020:102433. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeidi-Mobarakeh Z., Tavakkoli-Moghaddam R., Navabakhsh M., Amoozad-Khalili H. A bi-level and robust optimization-based framework for a hazardous waste management problem: a real-world application. J. Clean. Prod. 2020;252:119830. [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg A.B., Klementsen E., Muller G., De Andres A., Maillet J. Critical factors influencing viability of wave energy converters in off-grid luxury resorts and small utilities. Sustainability. 2016;8(12):1274. [Google Scholar]

- Serge Kubanza N., Simatele M.D. Sustainable solid waste management in developing countries: a study of institutional strengthening for solid waste management in Johannesburg, South Africa. J. Environ. Plann. Manag. 2020;63(2):175–188. [Google Scholar]

- Shankar R., Pathak D.K., Choudhary D. Decarbonizing freight transportation: an integrated EFA-TISM approach to model enablers of dedicated freight corridors. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 2019;143:85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Shi L., Fan H., Gao P., Zhang H. International Symposium on Intelligence Computation and Applications. Springer; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2009. Network model and optimization of medical waste reverse logistics by improved genetic algorithm; pp. 40–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sindhu S., Nehra V., Luthra S. Identification and analysis of barriers in implementation of solar energy in Indian rural sector using integrated ISM and fuzzy MICMAC approach. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016;62:70–88. [Google Scholar]

- Song J., Sun Y., Jin L. PESTEL analysis of the development of the waste-to-energy incineration industry in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017;80:276–289. [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Lei L., Zhou W., Chen C., He Y., Sun J., et al. A chemical cocktail during the COVID-19 outbreak in Beijing, China: insights from six-year aerosol particle composition measurements during the Chinese New Year holiday. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;742:140739. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W. 21st Century Business Herald; 2020. The Medical Waste Related to COVID-2019 Is Cleaned up Every Day—The Medical Waste Treatment Market Needs to Be Standardised.www.21jingji.com/2020/3-12/xNMDEz ODFfMTU0MjIxNQ.html Accessed on April, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur V., Anbanandam R. Healthcare waste management: an interpretive structural modeling approach. Int. J. Health Care Qual. Assur. 2016;29(5):559–581. doi: 10.1108/IJHCQA-02-2016-0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur V., Anbanandam R. Management practices and modeling the seasonal variation in health care waste. J. Model. Manag. 2017;12(1):162–174. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur V., Mangla S.K. Change management for sustainability: Evaluating the role of human, operational and technological factors in leading Indian firms in home appliances sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2019;213:847–862. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur V., Ramesh A. Analyzing composition and generation rates of biomedical waste in selected hospitals of Uttarakhand, India. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2018;20(2):877–890. [Google Scholar]

- The Economic Times . 5 March. 2018. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/healthcare/biotech/healthcare/india-to-generate-775-5-tonnes-of-medical-waste-daily-by-2020-study/articleshow/63426284.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst (India to Generate 775.5 Tonnes of Medical Waste Daily by 2020: Study). [Google Scholar]

- Townend W.K., Cheeseman C., Edgar J., Tudor T. Factors driving the development of healthcare waste management in the United Kingdom over the past 60 years. Waste Manag. Res. 2009;27(4):362–373. doi: 10.1177/0734242X09335700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinodh S., Asokan P. ISM and Fuzzy MICMAC application for analysis of Lean Six Sigma barriers with environmental considerations. Int. J. Lean Six Sigma. 2018;9(1):64–90. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Shen J., Ye D., Yan X., Zhang Y., Yang W., et al. Disinfection technology of hospital wastes and wastewater: suggestions for disinfection strategy during coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in China. Environmental Pollution. 2020:114665. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]