Abstract

L.P. Li, L. Venkataraman, S. Chen, and H.J. Fu. Function of WFS1 and WFS2 in the Central Nervous System: Implications for Wolfram Syndrome and Alzheimer’s Disease. NEUROSCI BIOBEHAV REVXXX-XXX,2020.-Wolfram syndrome (WS) is a rare monogenetic spectrum disorder characterized by insulin-dependent juvenile-onset diabetes mellitus, diabetes insipidus, optic nerve atrophy, hearing loss, progressive neurodegeneration, and a wide spectrum of psychiatric manifestations. Most WS patients belong to Wolfram Syndrome type 1 (WS1) caused by mutations in the Wolfram Syndrome 1 (WFS1/Wolframin) gene, while a small fraction of patients belongs to Wolfram Syndrome type 2 (WS2) caused by pathogenic variants in the CDGSH Iron Sulfur Domain 2 (CISD2/WFS2) gene. Although currently there is no treatment for this life-threatening disease, the molecular mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of WS have been proposed. Interestingly, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), an age-dependent neurodegenerative disease, shares some common mechanisms with WS. In this review, we focus on the function of WFS1 and WFS2 in the central nervous system as well as their implications in WS and AD. We also propose three future directions for elucidating the role of WFS1 and WFS2 in WS and AD.

Keywords: Wfs1, Wolframin, Wfs2, Cisd2, Wolfram Syndrome, Alzheimer’s Disease, Er Stress, Unfolded Protein Response, Mitochondria, Mitophagy, Excitotoxicity

1. Introduction

Two causative genes, WFS1 and WFS2, have been identified for Wolfram Syndrome type 1 (WS1) and Wolfram Syndrome type 2 (WS2), respectively (Amr et al., 2007; Inoue et al., 1998). The cardinal and diagnostic features of WS are insulin-dependent juvenile-onset diabetes mellitus, diabetes insipidus, progressive optic atrophy, and deafness (Barrett et al., 1995). In addition, WS patients exhibit a wide spectrum of neurological and psychiatric manifestations including brainstem and cerebellum atrophy, seizure, depression, anxiety, and cognitive decline (Barrett et al., 1995; Chaussenot et al., 2011; Rando et al., 1992; Scolding et al., 1996). Given the localization and function of WFS1 and WFS2 in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and mitochondria associated ER membrane (MAMs), WS is recognized as a rare neurodegenerative disorder associated with ER and mitochondrial dysfunction (Abreu and Urano, 2019; Pallotta et al., 2019; Urano, 2016). The dysregulated ER Ca2+ signaling, ER stress-induced unfolded protein response (UPR), and impaired mitochondrial function have also been found to play important roles in the pathogenesis of many neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Delprat et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2014c; Woods and Padmanabhan, 2012). Importantly, recent studies demonstrate that WFS1 and WFS2 may be directly and/or indirectly involved in the pathogenesis of AD (Chen et al., 2020; Lu et al., 2014). The aim of this review is to focus on the function of WFS1 and WFS2 in the central nervous system (CNS) and the molecular mechanisms underlying the neurodegeneration induced by loss-of-function of these two proteins in WS and AD. We also propose three future directions for elucidating the role of WFS1 and WFS2 in WS and AD. The development of novel therapeutic strategies for WS will not be discussed in this review since it has been covered by two recent excellent reviews (Abreu and Urano, 2019; Pallotta et al., 2019).

2. WFS1 and WS1

2.1. Structure, localization and function of WFS1

WFS1, also known as wolframin, is a hydrophobic, tetrameric glycoprotein of 890 amino acids (~ 100 kDa) with nine transmembrane domains (Inoue et al., 1998). The amino terminal is in the cytosol and the carboxy terminal of the protein is located in the ER lumen (Hofmann et al., 2003; Inoue et al., 1998; Takeda et al., 2001). WFS1 is encoded by the gene WFS1 spanning 33.4 kb, which is located in the short arm of chromosome 4 (4p.16) and has a total of 8 exons (Inoue et al., 1998). The first exon is non-coding, while exon 2–7 are small coding regions followed by exon 8, which encodes for most of the transmembrane region and the carboxy terminal (Inoue et al., 1998; Strom et al., 1998). Autosomal recessive mutations of the WFS1 gene causes WS1, the classical form of WS (Inoue et al., 1998). It is worthy of note that some dominant WFS1 mutations have been reported to cause non-syndromic diabetes (Bonnycastle et al., 2013) or progressive hearing loss with optic atrophy (Rendtorff et al., 2011). Non-syndromic optic atrophy has also been found to be associated with autosomal recessive mutations of WFS1 (Grenier et al., 2016).

WFS1 is highly expressed in the brain and the pancreas (Hofmann et al., 2003; Strom et al., 1998). Neurons in the brain and islet β-cells in the pancreas exhibit similar features and express proteins like glutamic acid decarboxylase, glutamate receptor, neurofilament proteins and receptors for neurotrophins (Atouf et al., 1997). It is interesting to note that both these cell populations, with high WFS1 expression are severely affected in WS leading to neurodegeneration and diabetes, two cardinal features of WS (Barrett et al., 1995). Within the brain, WFS1 expression is high in amygdala, hippocampus, olfactory tubercles, brainstem nuclei and thalamic reticular nucleus (Luuk et al., 2008; Takeda et al., 2001), explaining the high incidence of psychiatric disorders in WS (Blackwood et al., 1996; Swift et al., 1998). In the eyes, WFS1 is typically expressed in glial cells of the optic nerve, and across various layers of retina, including the pigment epithelium, inner nuclear layer, inner segment layer and the ganglion cell layer (Schmidt-Kastner et al., 2009; Yamamoto et al., 2006). WFS1 deficiency has been shown to induce reduced myelinization of optic nerve and neuronal death of ganglion cells, both of which contribute to optic nerve atrophy (Lugar et al., 2016; Plaas et al., 2017; Yamamoto et al., 2006) and the clinical symptoms of cataracts, color blindness, loss of peripheral vision and blindness (Hoekel et al., 2014). Strong immunoreactivity of WFS1 is found in the organ of Corti and spiral ganglion neurons in both mice and adult marmoset cochlea (Suzuki et al., 2016). However, staining is also observed in stria vascularis basal cells of marmoset cochlea that is absent in mice (Suzuki et al., 2016). These finding along with absence of deafness in WFS1 knockout (KO) model indicates that WFS1 dysfunction in basal cells could be the reason for hearing loss in WS (Suzuki et al., 2016).

Human WFS1 protein expression is low at fetal stage (14–16 weeks) and gradually increases with time to reach a plateau after attaining sexual maturity (De Falco et al., 2012). Mouse WFS1 mRNA expression in the forebrain also starts during late embryonic development in the dorsal striatum and amygdala and then spreads throughout other brain regions after birth (Tekko et al., 2014). The mRNA expression of WFS1 closely correlates with neuronal differentiation (Tekko et al., 2014). Furthermore, WS is associated with smaller intracranial volume with specific abnormalities in the brainstem and cerebellum, even at the earliest stage of clinical symptoms (Hershey et al., 2012). This pattern of abnormalities suggests that WFS1 has a pronounced impact on early brain development. Altogether, these data indicate the important role of WFS1 in neuronal development. Interestingly, the mRNA level of WFS1 has been shown to increase with aging in the brains of rodents and flies (Pereira et al., 2017; Sakakibara et al., 2018). A recent study showed that knockdown of WFS1 renders neurons more susceptible to age-induced degeneration (Sakakibara et al., 2018). These findings suggested an evolutionarily conserved role of WFS1 in regulating neuronal integrity during aging (Sakakibara et al., 2018).

As an ER-resident protein, WFS1 has an important role in maintaining ER Ca2+ homeostasis and regulating UPR in different cell populations (Fonseca et al., 2010). A majority of the mutations in WFS1 occur in the largest exon 8 (Inoue et al., 1998; Rigoli et al., 2011; Strom et al., 1998), leading to high ER stress activating UPR (Yamada et al., 2006). There is complete absence of WFS1 protein rather than truncated species due to immediate degradation of nonsense WFS1 transcripts (Hofmann et al., 2003). This results in a loss-of-function of WFS1 leading to severe neurodegeneration and other symptoms associated with WS. WFS1 has also been shown to stabilize and interact with the V1A subunit of the H+ V-ATPase (proton pump) located in secretory vesicles based on electron microscopy and co-immunoprecipitation studies in human neuroblastoma cell lines (Gharanei et al., 2013). The vesicular proton pump is involved in the acidification of secretory granules in both pancreatic and neuronal cells, which is essential for protein secretion. In WFS1 deficient mice, changes in Na-pump activity and in mRNA expression levels of the α1 and β1 subunits in amygdala, striatum and other brain regions have been observed (Sütt et al., 2015). Proteasomal inhibition studies with MG132 in WFS1-depleted neuroblastoma (SK-N-AS) cells and control cell lines show that WFS1 targets SERCA (sacro/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase) for proteosomal degradation, suggesting a role for WFS1 in SERCA protein turnover (Zatyka et al., 2015). Taken together, these studies indicate that WFS1 is involved in protein biosynthesis, stabilization, folding, maturation, and secretion.

The protein stability of WFS1 has been shown to be regulated by post-translational modification and ubiquitin-mediated proteosomal degradation. For example, inhibition of N-glycosylation of WFS1 increases its protein turnover rate (Yamaguchi et al., 2004). Interaction of the C-terminal luminal region of WFS1 with Smad ubiquitination regulatory factor 1 (Smurf1), a ubiquitin ligase can promote the ubiquitination and proteosomal degradation of WFS1 (Guo et al., 2011).

2.2. Clinical manifestations of WS1 in the central nervous system

Optic atrophy and progressive neurodegeneration are two main characteristics in defining the clinical manifestations of WS1 in the CNS (Barrett and Bundey, 1997). Neuroimaging studies with MRI show widespread atrophic changes throughout the brain of WS1 patients, primarily in the cerebellum, brainstem, thalamus and the white matter that connect them (Chaussenot et al., 2011; Hershey et al., 2012; Lugar et al., 2019; Rando et al., 1992; Scolding et al., 1996). Altered white matter microstructural integrity in optic radiations have been observed in patients at early stage of WS1 (Lugar et al., 2016). Neurological manifestations are also frequently seen in patients with WS1. Ataxia (Barrett et al., 1995; Chaussenot et al., 2011) and gait abnormalities (Marshall et al., 2013; Pickett et al., 2012) are present in patients’ early life and may reflect early cerebellar and/or brainstem impairment; Dysphagia (swallowing disorders) or central respiratory failure resulted from brainstem atrophy are the common cause of mortality (Barrett et al., 1995). Sleep disturbances (Bischoff et al., 2015; Licis et al., 2019) and decreased ability to taste and to identify smell (Alfaro et al., 2020; Bischoff et al., 2015; Marshall et al., 2013) have been recently reported and are thought to be useful biomarkers of early disease (Bischoff et al., 2015). Psychiatric symptoms related to anxiety, depression, psychosis, panic attack and mood wings have also been reported in WS1 patients and are receiving increasing attention in WS research (Hardy et al., 1999; Matsunaga et al., 2014; Swift et al., 1990; Waschbisch et al., 2011). It has been reported that carriers of WFS1 mutations display an increased likelihood of psychiatric hospitalization primarily due to depression (Swift and Swift, 2005; Swift and Swift, 2000). It has been noted in a more recent study that psychiatric symptoms were not present in relatively early stage of WS1, indicating psychiatric symptoms as a later emerging problem in WS1 (Bischoff et al., 2015).

2.3. Molecular mechanisms underlying the loss of neuronal function of WFS1 in WS1

In this section, we summarize the findings from WFS1 research with pancreatic β cells, neurons, and cell lines followed by a discussion of potential mechanisms by which WFS1 deficiency causes impaired neuronal function and neuronal death.

ER stress triggers the activation of UPR, which comprises three major signaling branches, initiated by the protein kinase RNA-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK), inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1) and the activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) (da Silva et al., 2020; Hetz and Saxena, 2017). WFS1 seems to regulate all three UPR pathways (Fonseca et al., 2005; Fonseca et al., 2010; Kakiuchi et al., 2006; Yamada et al., 2006). Previous studies with rodent pancreatic β-cells and human fibroblast cell line show that WFS1 suppresses the activation of ATF6α through HRD1-mediated ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of ATF6α, thus positing WFS1 as a negative modulator of ER stress (Fonseca et al., 2010). In consistency with these findings, downregulation of WFS1 has been shown to enhance ER stress, as evidenced by increased phosphorylation of PERK, enhanced chaperone gene expression and elevated protein level of XBP-1, downstream of IRE1 activation (Fonseca et al., 2005; Yamada et al., 2006). Enhanced ER stress, on the other hand, increases WFS1 mRNA and protein levels (Kakiuchi et al., 2006; Ueda et al., 2005; Yamaguchi et al., 2004). These data, together, indicates a negative-feedback loop that regulates ER stress signaling pathways by WFS1 (Fonseca et al., 2010). ATF6 has two isoforms - ATF6α and ATF6β. While ATF6α directly affects UPR genes leading to its suboptimal induction, ATF6β knockdown in insulinoma cells increases susceptibility of β-cells to ER stress leading to death (Odisho et al., 2015). ATF6β binds to the WFS1 promoter and induces expression of WFS1 (Odisho et al., 2015), which suppresses the ER stress response and maintains the survival of β-cells (Odisho et al., 2015). Other studies suggest that WFS1 is also a novel calmodulin-binding protein and involved in Ca2+ signaling transduction (Yurimoto et al., 2009). Overexpression of WFS1 increases Ca2+ concentration in the ER, whereas knockdown of WFS1 reduces ER Ca2+ level (Takei et al., 2006). The effects of WFS1 on ER Ca2+ signaling are partially mediated through the regulation of the filling state of ER Ca2+ store (Takei et al., 2006). A follow-up study further demonstrates that this regulation of ER Ca2+ filling by WFS1 may be mediated via a mechanism involving SERCA, which is an important Ca2+ transporter required for the ER Ca2+ homeostasis. It has been shown that WFS1 can bind with SERCA and regulate its function and level of expression (Zatyka et al., 2015).

A recent study reports that treatment of liraglutide, a GLP-1 receptor agonist reduces ER stress and prevents neuronal loss in the inferior olive of the brainstem in WFS1-mutant mice as evidenced by reduced signal of ER stress marker GRP78 and an increased number of neurons in liraglutide treated WFS1-KO rats compared to vehicle treated WFS1-KO rats (Seppa et al., 2019). These findings suggest GLP-1 and its receptor as a potential mechanism linking ER stress to neuronal death or brainstem atrophy seen in patients with WS. In the same study, the authors also observe increased neuronal volume defined by neuronal swelling in WFS1-KO rats relative to wild type (WT) controls (Seppa et al., 2019). Neuronal swelling is a process whereby an unchecked extracellular ions, especially Na+ enter into neurons and usually involves dysfunction of Na+/K+-ATPase (Liang et al., 2007). Interestingly, WFS1 has been reported to interact with Na+/K+-ATPase, and decreased Na+/K+-ATPase is seen in multiple brain regions of WFS1-deficient mice (Sütt et al., 2015). These observations collectively indicate that WFS1 deficiency-induced neuronal death may also be caused by neuronal swelling that induced by the dysregulation of Na+/K+-ATPase activity.

It has been reported that ER stress is also able to modulate mitochondrial function, and ER-mitochondria interaction has a vital role in Ca2+ homeostasis (Senft and Ze’ev, 2015). A series of experiments conducted by Cagalinec et al. demonstrate that loss of WFS1 triggers ER stress (increased ATF6 and ATF4), which impairs IP3R (inositol 1, 4, 5-trisphosphate receptor)-mediated ER Ca2+ release and therefore leading to a disturbed Ca2+ homeostasis in primary cortical neurons (Cagalinec et al., 2016). Impaired IP3R function associated with WFS1-deficiency may result from a decreased level of neuronal calcium sensor 1 (NCS1) (Angebault et al., 2018), which is a neuronal calcium-binding protein and is able to increase the channel activity of IP3R (Schlecker et al., 2006). It has been shown that NCS1 binds with WFS1 and is downregulated when WFS1 is deficient (Angebault et al., 2018). Altered Ca2+ homeostasis due to decreased NCS1 abundance and/or impaired IP3R function leads to defective mitochondrial dynamics, which are featured with decreased Ca2+ uptake, impaired respiratory chain function, enhanced mitophagy and inhibited fusion (Angebault et al., 2018; Cagalinec et al., 2016). Importantly, overexpression of NCS1 restores normal Ca2+ uptake and respiration in patient fibroblasts (Angebault et al., 2018); and overexpression of IP3R or blocking mitophagy can prevent deficits in the development and survival of WFS1-mutant neurons (Cagalinec et al., 2016). Overall, these data reveal critical roles of NCS1 and IP3R in ER-mitochondria cross talk and shed new light onto the mechanisms underlying WS, and potentially provide valuable insights into the pathogenesis of other neurodegenerative diseases.

Although converging evidence suggests ER stress and mitochondrial dysfunction as the main mechanisms by which WFS1 deficiency affects neuronal function and cell death, discrepant results still exist. ER stress-induced activation of the UPR is not observed in non-pancreatic tissues of WFS1 knockout mice (Yamada et al., 2006). A primary mitochondrial dysfunction is not found in WS patients, although there is calcium mishandling between ER and mitochondria (La Morgia et al., 2020). A recent study using the fly model also finds that the neurodegeneration induced by knockdown of wfs1 in the fly brains is not associated with dysregulated ER stress or mitochondrial dysfunction, as wfs1 deficiency has no effects on the mRNA levels of UPR-related genes or the genes involved in mitochondrial fission and fusion (Sakakibara et al., 2018). Instead, knockdown of wfs1 significantly reduces the gene expression of excitatory amino acid transporter 1 (Eaat1), a glutamate transporter expressed in the glial cells, leading to increased oxidative stress and altered neuronal excitability (Sakakibara et al., 2018). These results suggest that wfs1 deficiency increases the susceptibility to neuronal dysfunction caused by altered neuronal excitability in flies.

A study performed by Lu et al. shows that neural progenitor cells derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) of a WS patient are more susceptible to thapsigargin-induced cell death when compared with the progenitors derived from an unaffected patient (Lu et al., 2014). This susceptibility is due to the hyperactivation of calpain, a Ca2+-dependent cysteine protease, which happens under the condition of dysregulated ER Ca2+ signaling induced by WFS1 deficiency (Lu et al., 2014). As iPSCs can be differentiated into different types of neurons, it remains unclear which cell type is more vulnerable to WFS1 deficiency-induced damage (Lu et al., 2014). Previous studies identify that WFS1 mRNA and protein are preferentially expressed in excitatory neuron in prefrontal cortex (PFC), hippocampal CA1 and entorhinal cortex (EC) (Cembrowski et al., 2016; Kawano et al., 2009; Luuk et al., 2008; Shrestha et al., 2015; Takeda et al., 2001). In the inferior olive of rat brainstem, WFS1 protein is localized exclusively in FOXP2-expressing excitatory neurons (Plaas et al., 2017). Whether excitatory neurons in these brain regions are more susceptible to WFS1 deficiency-induced damage and whether this damage is associated with ER stress signaling pathways remain to be investigated.

Gene-expression network-based analysis across specific cell types has suggested that the expression of WFS1 and its functionally related genes occur preferentially in oligodendrocytes and oligodendrocyte progenitors during early brain development (Samara et al., 2019). Oligodendrocytes-associated WFS1 deficiency is thought to be responsible for the abnormal white matter myelination found in the early stage of WS (Samara et al., 2019). Additional studies also detect WFS1 mRNA and protein in glial cells of the optic nerve in mammals (Kawano et al., 2008; Yamamoto et al., 2006). It has been proposed that astrocytes-specific absence of glutamine synthetase (GS) and the resulted impaired glutamate clearance within the astrocytic filament dense of optic nerve may contribute to the axonal atrophy in the optic nerve (Kawano et al., 2008). The strong presence of WFS1 protein in both retinal ganglion cells and optic nerve glial cells in the cynomolgus monkey also suggests that dual deficiency of WFS1 in these two cell types may additively contribute to the optic nerve atrophy in WS (Yamamoto et al., 2006). In support of this cell autonomous (neurons) and non-autonomous (glia) role of WFS1 in neurodegeneration, a recent study demonstrates that WFS1 knockdown in both neurons and glial cells in fly brains leads to a more severe neurodegeneration than knockdown of WFS1 only in neurons (Sakakibara et al., 2018), suggesting that neuronal and glial WFS1 work in concert to maintain neuronal function and survival.

WFS1 has also been shown to interfere with dopaminergic and serotonergic systems. The gene expressions of dopamine (DA) transporter (DAT) and serotonin (5-HT) transporter (SERT) are significantly decreased in the midbrain and the pons of WFS1 KO mice, respectively, when compared with WT controls (Visnapuu et al., 2013a; Visnapuu et al., 2013b). In addition, amphetamine-induced release of DA and stress (brightness)-induced release of 5-HT and its metabolite 5-HIAA are significantly blunted in the striatum of WFS1 KO mice relative to WT mice (Visnapuu et al., 2013a; Visnapuu et al., 2013b). The compromised function of dopaminergic and serotonergic systems associated with WFS1 deficiency may provide a possible explanation of depressive symptoms seen with WS patients. Recently, by using single molecule fluorescent in situ hybridization (smFISH) and RNA-sequencing of D2R (dopamine D2 receptors)-expressing striatal neurons, it has been shown that WFS1 gene displays a segregated expression pattern along the dorsal-ventral axis in the striatum with a prominent expression of WFS1 in the nucleus accumbens (Acb, part of ventral striatum) and a much weaker expression in the dorsal striatum (Puighermanal et al., 2020). Conditional knockout of D2R from WFS1-positive neurons caused a significant impairment in digging behavior and an enhanced response to amphetamine (Puighermanal et al., 2020). How Acb-associated expression of WFS1 relating to WS1 remains to be further explored.

A previous study showed that WFS1 KO mice displayed altered responses in stressful environment, including a significantly greater increase of plasma corticosterone upon exposure to stress compared with WT littermates (Luuk et al., 2009). Later studies confirmed that the enhanced sensitivity to stress of WFS1 KO mice was in part due to abnormal function of forebrain neurons (Shrestha et al., 2015). It has also been shown that conditional knockout (CKO) of WFS1 in the layer2/3 pyramidal neurons of the PFC leads to a hyperactivation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis accompanied by elevated level of serum corticosterone in response to stress (Shrestha et al., 2015). In addition, WFS1 expression within the PFC appeared to be critical for the regulation of stress-induced depressive phenotypes. WFS1 CKO mice displayed increased immobility in forced swim test and reduced intake of sucrose in sucrose preference test following acute stress, two featured depressive phenotypes in mice (Shrestha et al., 2015). These findings together suggest that the clinical manifestation of depression in WS patients may in part due to dysfunction of WFS1 in the PFC and a hyperactivation of HPA axis in response to stress.

3. WFS2 and WS2

3.1. Structure, localization and function of WFS2

Although WFS1 gene accounts for a large fraction of the WS cases, linkage analysis study of four Jordanian families points towards WFS2 gene, of which mutations cause WS2, a second and rarer form of WS (Amr et al., 2007; El-Shanti et al., 2000). WFS2 is located at 4q24 and encodes the zinc-finger protein WFS2 (Amr et al., 2007) (also known as CISD2, Miner1, ERIS and NAF-1). WFS2 is a member of the novel 2Fe-2S CDGSH protein family and contains an atypical ER localization sequence, an N-terminal transmembrane domain, and a CDGSH 2Fe-2S domain (Conlan et al., 2009). The protein has high redox potential due to the presence of 2Fe-2S, which facilitates its involvement in protein modification, ER stress response and mitochondrial function (Conlan et al., 2009). It is folded into two spatially distinct sub-regions- a β rich ‘β-Cap’ domain and a helical 2Fe-2S ‘cluster-binding’ domain. This unique fold is similar to an outer mitochondrial membrane protein called mitoNEET (Wiley et al., 2013). This conformation of WFS2 aids in the FeS cluster assembly, its mobilization within the cell, and its ability to function in a redox capacity (Wiley et al., 2013).

Initial studies based on staining in COS-7 cells and immunoprecipitation in mouse P19 and human HEK293 cells, show that WFS2 is colocalized with ER marker protein calnexin, indicating it is located in the ER (Amr et al., 2007; Wiley et al., 2007). However, WFS2 has also been shown to localize in the mitochondrial outer membrane (MOM) based on experiments in NIH3T3 cells and analysis of cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions derived from skeletal muscle of wild type mice (Chen et al., 2009). A recent study demonstrates that WFS2 is abundant in ER enriched fractions and mitochondria associated ER membrane (MAMs), but not in pure mitochondria based on the analysis of microsomal (ER), MAMs and mitochondrial fractions from rat livers, indicating that WFS2 is mainly localized to the ER (Wiley et al., 2013).

A homozygous mutation at nucleotide 109 in WFS2 gene has been reported to cause aberrant mRNA splicing leading to exon 2 skipping and premature termination, which results in the elimination of 75% of the protein, including the transmembrane and zinc-finger domains (Amr et al., 2007). A more recent case study reported a novel homozygous WFS2 mutation mapping within the donor splice site of intron 1 and presumably results in a deletion of exon 1 (Rondinelli et al., 2015). Mutations in WFS2 gene has been associated with premature aging, mitophagy and mitochondrial dysfunction (Angebault et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2009; Kanki and Klionsky, 2009). WFS2 KO mice show decreased ER Ca2+ and increased mitochondrial Ca2+, which induces the ER stress and activation of UPR, resulting in the neuronal and muscle degeneration (Chen et al., 2009). Autophagic vacuoles and elevated levels of autophagosome marker LC3-II are observed in skeletal and cardiac muscles of WFS2 KO compared to WT mice, indicating the involvement of WFS2 in mitophagy and its regulation (Chen et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2014b). WFS2 deficiency also results in accelerated aging, muscular dystrophy, abnormal skeleton, impaired glucose tolerance and blindness (Chen et al., 2009; Wiley et al., 2013). WFS2 seems to be playing an important role in aging and metabolic dysfunction, and further investigation is required to understand its role in neurodegeneration associated with WS2.

3.2. Clinical manifestations of WS2 in the central nervous system

Neurological abnormalities such as atrophy of optic nerve, brainstem and cerebellum are also common in WS2 (Aloi et al., 2012; Pallotta et al., 2019; Rigoli and Di Bella, 2012; Rouzier et al., 2017). Case studies have shown a presentation of anxiety with psychosis and cognitive impairments in WS2 patients (Aloi et al., 2012). Different from WS1, WS2 patients have no diabetes insipidus (Rigoli and Di Bella, 2012), but display additional symptoms such as upper gastrointestinal ulceration, significant bleeding tendency and impaired platelet aggregation with collagen (Al-Sheyyab et al., 2001; El-Shanti et al., 2000; Mozzillo et al., 2014).

3.3. Molecular mechanisms underlying the loss of neuronal function of WFS2 in WS2

The important role of WFS2 in regulating mitochondria integrity and mitophagy in neurons is first revealed by the work from Tsai group (Chen et al., 2009). By conducting transmission electron microscopy (TEM) study, they find mitochondrial degeneration in the axons of sciatic nerves and hippocampal neurons in the WFS2 KO mice (Chen et al., 2009). Remarkably, in agreement with their observation that WFS2 is a MOM protein, the outer membrane of mitochondria is destroyed prior to the breakdown of the inner cristae (Chen et al., 2009). Impaired mitochondrial integrity has been shown to induce mitophagy, a self-degradative process for eliminating defective organelles (Mijaljica et al., 2007). Increased autophagic vacuoles enclosing mitochondria are observed in the axon of Schwann cells from sciatic nerve of WFS2 null mice at an age as early as 2-weeks old (Chen et al., 2009), providing morphological evidence of neuronal death with autophagic features (Kanki and Klionsky, 2009). It is thought that mitochondrial dysfunction and subsequent autophagic cell death may underlie the optic atrophy and neurodegeneration seen with WS2 patients (Chen et al., 2009). Interestingly, WFS2 deficiency-induced dysregulated autophagy and mitochondrial function is associated with premature aging phenotypes in WFS2 KO animals, which include prominent eyes and protruding ears, impaired vision, neuron and muscle degeneration (Chen et al., 2009). Overexpression of WFS2 significantly elongates lifespan, protects age-related mitochondrial damage and delays neuron and muscle degeneration in WFS2 transgenic mice (Wu et al., 2012).

Previous studies on different types of cancer cells and muscle cell have identified that ER-resident protein Bcl-2 (B cell lymphoma 2), via preventing the formation of autophagosome-initiating complex, plays a critical role in autophagy inhibition in the context of nutrient-deprivation (Pattingre et al., 2005). WFS2 is required for Bcl-2 to execute this role (Chang et al., 2012; Chang et al., 2010). WFS2 knockdown significantly increases Bcl-2-associated autophagy upon starvation as measured by the level of LC3-II, a marker for autophagic response (Chang et al., 2010). These findings, together with the ones described by Tsai group indicate that WFS2 appears to mediate mitophagy via a Bcl-2 related mechanism. It remains to be elucidated if WFS2 deficiency-induced mitophagy in neurons is mediated by the same mechanism or by an unknown mechanism independent of Bcl-2. Results from this investigation will further our understanding of the mechanisms underlying WFS2 deficiency-induced mitophagy in neurons.

Similar to the role of WFS1 in regulating ER stress and UPR, WFS2 has also been shown to play a role in UPR induction. The mRNA and protein levels of ER stress genes such as Bip and CHOP are significantly increased in mouse embryo fibroblast cells (MEF) from WFS2 KO animals (Wiley et al., 2013). The gene expression of XBP1 is also increased in WFS2 KO MEFs (Wiley et al., 2013). Additionally, in the same cells, immunostaining of ER protein calreticulin demonstrates an increase in the density of the reticular staining pattern throughout the cell (Wiley et al., 2013), which suggests an ER expansion, a hallmark of ER stress and activated UPR (Zheng et al., 2011). Based on these findings and the ones from WFS1 research, the authors argue that ER stress and activation of UPR might be the common pathway that underlying the etiology of WS (Wiley et al., 2013).

Ca2+ signaling is critical in regulating various cellular and molecular processes, including ER stress induced UPR (Görlach et al., 2006; Marchi et al., 2018). Altered UPR induced by WFS2 deficiency may be accompanied by impaired Ca2+ homeostasis. Indeed, increased cytosolic Ca2+ is found in different types of cells from WFS2 KO animals and WS2 patient-derived fibroblast based on multiple independent studies (Chang et al., 2012; Rouzier et al., 2017; Tsai et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2014a). However, discrepant results are also reported (Amr et al., 2007; Wiley et al., 2013). A study of lymphoblastoid cell line derived from WS2 patients demonstrates that when treated with thapsigargin, a known ER Ca2+ store depleter, there is significantly more intracellular Ca2+ release when compared with the cells from unaffected controls (Amr et al., 2007), indicating there might be a higher level of ER Ca2+. In support of this idea, a previous study using Ca2+-sensitive ER-targeted aequorin photoprotein technique to directly measure ER Ca2+ levels reports an increase in ER Ca2+ concentration in WFS2 KO cells (Chang et al., 2012). A later study, however, does not reveal a significant change in ER Ca2+ level (Wang et al., 2014a).

In addition to the role of WFS2 in regulating ER Ca2+ store, previous studies also reveal an involvement of WFS2 in modulating the ability of mitochondria to uptake ER-released Ca2+. Efficient Ca2+ transmission from ER to mitochondria is enabled by localizing the ER Ca2+ efflux channel, such as IR3R to a specific site where the MOM and ER are physically interacted (Marchi et al., 2017). This specific contact site is known as mitochondria-associated ER membrane (MAM) (Marchi et al., 2017). Studies have shown that WFS2 is enriched in the MAMs in different cells and tissues, including MEF (Wang et al., 2014a; Wiley et al., 2013), brain, liver and muscle (Wang et al., 2014b). It has been reported that WFS2 deficiency decreases the uptake of Ca2+ by mitochondria; and the decreased uptake is more pronounced when there is an additional deficiency of Gimap5, a WFS2-interacting protein also found in the MAMs (Wang et al., 2014a). However, conflict results show an increased Ca2+ flux from the ER to mitochondria in both WS2 patient derived fibroblast (Rouzier et al., 2017) and WFS2 KO MEFs (Wiley et al., 2013), which is possibly mediated through enhanced activity of the ER Ca2+ efflux channel IP3R. Augmented IP3R activity is associated with the oxidative microenvironment that created by WFS2 deficiency (Wiley et al., 2013). Albeit with the discrepancies from previous studies, WFS2 appears to be a key molecular player in the regulation of Ca2+ homeostasis (Delprat et al., 2018). Since the previous studies mostly focus on cell lines and fibroblasts and may not accurately reflect the role of WFS2 in neurons, it is of great interest to conduct related investigations in neurons, which will provide insights on the mechanisms underlying WFS2 deficiency-mediated neurodegeneration.

WFS2 deficiency results in neuron and β cell death. However, the mechanisms behind it remain unclear. Studies show that similar to WFS1, loss of WFS2 also induces the hyperactivation of the proapoptotic protein calpain, which ultimately leads to cell death (Lu et al., 2014). Pre-treatment of calpeptin, a calpain inhibitor prevents WFS2 deficiency-induced cell death in both neuronal and β cell lines. Furthermore, WFS2 reduces the protein stability of calpain via regulating the degradation of CAPNS1, the regulatory subunit of calpain through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (Lu et al., 2014).

4. WFS1, WFS2 and Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by accumulation of extracellular amyloid β (Aβ) plaques, intracellular neurofibrillary tangles, progressive neuronal loss and cognitive decline. Although a previous case-control study shows that two haplotype-tagging single nucleotide (htSNP) of WFS2, rs223330 and rs223331 are not associated with the risk for AD (Hsieh et al., 2015), a recent study provides direct evidence for the role of WFS2 in the pathogenesis of AD. By crossing APP/PS1 transgenic mice (AD-like mice) with WFS2 transgenic mice, the authors are able to show that overexpression of WFS2 protects Aβ-induced neuronal loss in the hippocampus. On the contrary, WFS2 KO in the AD-like mice induces more severe neuronal loss (Chen et al., 2020). The protective effect of WFS2 in neuronal loss appears to be mediated through the regulation of mitochondrial function. WFS2 overexpression has been found to protect against mitochondrial damage and improve mitochondrial function as measured by oxygen consumption rate (OCR) (Chen et al., 2020). Furthermore, transcriptional profiling studies in the hippocampus of WT, AD and AD;WFS2 transgenic mice discover that a total of 154 genes that dysregulated in AD are rescued or reserved by overexpression of WFS2 (Chen et al., 2020). Some of the genes play important roles in mitochondrial function and neurotransmission (Chen et al., 2020). It is worth mentioning that WFS2 also plays a role in the regulation of neuroinflammation. AD-like mice display enhanced microglia activation, a prominent inflammatory feature in the brain (Chen et al., 2020). However, when overexpressed with WFS2, AD-like mice have a significantly decreased number of activated microglia (Chen et al., 2020). The role of WFS2 in neuroinflammation has also been reported previously. By measuring pro-inflammatory mediators such as iNOS, TNFα and IL-1α, knockdown of WFS2 has been shown to enhance inflammatory responses in LPS-treated SH-SY5Y cells (Kuo et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2019). In addition, increased expression of iNOS is also found to be associated with decreased WFS2 in the injured spinal cord (Lin et al., 2015).

A systemic investigation on the relationship of WFS1 and AD is lacking, however, emerging evidence does suggest a role of WFS1 in AD. The role of WFS1 in tau toxicity-induced neurodegeneration is investigated in a recent study using the fly model. It has been shown that neuronal knockdown of WFS1 aggravates axon degeneration in the eyes induced by overexpression of human tau (Sakakibara et al., 2018). Interestingly, although overexpression of human tau alone slightly increases the mRNA level of UPR marker genes, knockdown of WFS1 in combination of tau expression does not further enhance UPR signaling (Sakakibara et al., 2018), indicating that WFS1 deficiency-induced increased tau toxicity may be mediated via a UPR-independent mechanism. It will be of great interest to extend this study to tau mice models and investigate if WFS1 play a role in tau-pathology induced neurodegeneration and if UPR-related mechanism is involved.

WFS1-positive excitatory neurons represent a subpopulation of grid cells in the medial entorhinal cortex (MEC) and have a critical role in modulating spatial memory (Sun et al., 2015). By utilizing a transgenic mouse model (EC-tau model) in which accumulation of tau pathology is observed in the entorhinal cortex (EC) (Liu et al., 2012), a previous study shows that EC-tau mice display impaired spatial memory and that tau aggregates in the EC is associated with excitatory neuronal loss and grid cell dysfunction (Fu et al., 2017). These data indicate a novel role of WFS1 in neuronal vulnerability to tau pathology associated with AD. Similarly, the expression of WFS1 also renders neurons more vulnerable to ischemia-induced damage. Neurons in the dorsal hippocampal CA1 region with a high level of WFS1 are typically damaged by ischemia while the neurons in the CA3 region where WFS1 signal is absent are spared (Luuk et al., 2008; Schmidt-Kastner, 2015). This selective vulnerability in CA1 might be associated with suppressed protein synthesis induced by WFS1 upon ischemia-induced ER stress (Schmidt-Kastner, 2015). Additional studies are needed to address if WFS1 deficiency or knockdown-induced protein synthesis suppression is one possible mechanism underlying EC and/or CA1 neuronal loss in the context of AD.

Gene expression profiling studies on WFS1-deficient mice have provided additional information on the molecular mechanisms leading to neurodegeneration in AD (Ivask et al., 2018; Kõks et al., 2013; Koks et al., 2009). Emerging evidence indicates that TRP channels play an important role in regulating Ca2+ homeostasis disruption and ER stress in AD (Sukumaran et al., 2016; Yamamoto et al., 2007). RNA sequencing in the hippocampus of WFS1 mutant mice demonstrates an increased gene expression of Trpm8 and Trpv3, both of which encode subtypes of transient receptor potential (TRP) channels (Ivask et al., 2018). Transthyretin, known as a transport protein carrying thyroxine and retinol, plays a protective role in amyloid mediated neurodegeneration (Buxbaum et al., 2008). It has been shown that transthyretin is significantly downregulated in the temporal lobe of mice with WFS1 gene deletion (Koks et al., 2009). Further studies on WFS1 interactions with TRP channels and transthyretin in affected brain regions of AD could provide additional evidence for the involvement of WFS1 in the pathogenesis of AD and shed light on the mechanisms underlying neuronal loss in AD.

Although no Aβ plaques or tangles are found in WS patients and WFS1 or WFS2 KO animals, a study of 59 WS subjects shows that cognitive disability involves 32% of those patients (Chaussenot et al., 2011). Furthermore, previous studies on the pathological mechanisms of AD and WS have demonstrated that these two neurodegenerative diseases may share common physiopathological signaling pathways, including the pathways associated with dysregulated Ca2+ signaling, ER stress and UPR, impaired mitochondrial function and autophagic pathology, and excitotoxicity (Delprat et al., 2018; Esposito et al., 2013; Uddin et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2014c; Woods and Padmanabhan, 2012). Based on above direct and indirect evidence of the relationship between WFS1/WFS2 vs AD, it is tempting to hypothesize that WFS1 or WFS2 dysfunction may increase the risk of development and/or progression of AD. It should be noted that the spatial and temporal properties of neurodegenerative process in WS and AD are very different, i.e. the degeneration of brainstem, cerebellum and visual pathway at an early age for WS vs hippocampal and cortical degeneration in later life for AD (Fu et al., 2018; Lugar et al., 2019). Thus, we think WFS1 or WFS2 dysfunction may mainly increase the risk of AD, but itself cannot cause AD. In the presence of WFS1 or WFS2 dysfunction, other disease-contributing factors may synergistically increase the neuronal vulnerability to AD pathology in those vulnerable brain regions of AD such as the hippocampus and cortex.

5. Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

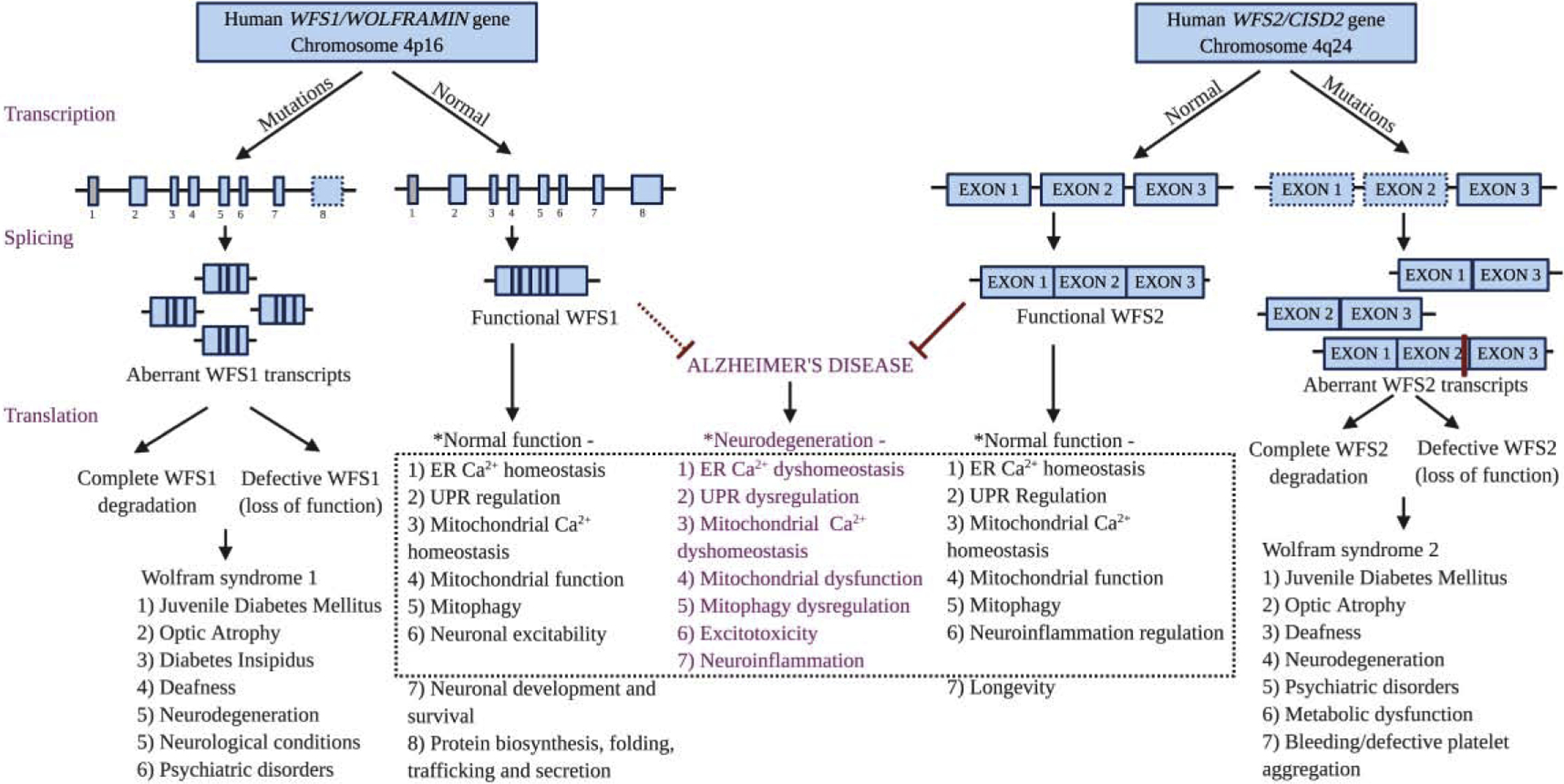

WS is a rare genetic neurodegenerative disorder with a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations. Although it is difficult and challenging to find out the exact mechanisms underlying the neurodegeneration in individual WS patients, a few common mechanisms arise from extensive multidisciplinary studies. These common mechanisms may include the ER Ca2+ dyshomeostasis, UPR dysregulation, mitochondrial Ca2+ dyshomeostasis, mitochondrial dysfunction, mitophagy, and excitotoxicity (Figure 1). Interestingly, AD shares these common mechanisms with WS. Furthermore, deficiency of WFS1 or WFS2 increases the neurodegeneration in Drosophila overexpressing human tau and AD-like mouse model, respectively. The overexpression of WFS2 protects Aβ-induced neuronal loss in the hippocampus. These studies strongly suggest that WFS1 and WFS2 may play important roles in the development and progression of AD. The current ongoing clinical trials targeting WS may also provide very useful insights for developing novel therapeutic strategies against AD, which is the most common form of dementia without cure or disease-modifying treatments.

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of the structure and function of WFS1 and WFS2 under normal and disease conditions.

Mutations in both the genes cause aberrantly spliced transcripts leading to complete degradation or loss of function of the WFS1 and WFS2 protein, resulting in Wolfram syndrome type 1 and type 2, respectively. Potential overlap mechanisms underlying the neurodegeneration in Wolfram syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are highlighted in purple at the center of the dotted black box. * Based on animal and cell culture studies. Most of the identified mutations of WFS1 are situated in exon 8 indicated by dashed line square. The first exon of WFS1 is a non-coding exon indicated by grey square. The exons of WFS2 in dashed line square (exon 1 and exon 2) represent the exons found to be deleted in patients with mutations. The red bar between exon 2 and exon 3 of WFS2 transcript indicates the reported mutations of human WFS2 in exon 2. The red dotted line indicates that the role of WFS1 in AD is speculated according to previously published indirect evidence. Created with BioRender.com.

In addition, we believe there are a few new directions need to pay attention in the future. First, the expression and distribution of WFS1 and WFS2 varies in different cell types and brain regions. However, their roles in different cell types remain largely unknown. Given the high heterogeneous property of cells, especially neurons in the brain, the single-cell or single-nucleus RNA-seq analysis will help identify the vulnerable neurons in WS and AD, and elucidate the novel mechanisms underlying the cell-type specific role of WFS1 and WFS2 in WS and AD. Second, most of current studies on WS are using animals and/or immortalized cell lines, which may not fully recapitulate the molecular, structural, and genetic complexity of human WS. The emerging human iPSCs derived from WS patients or human cerebral organoids generated from these iPSCs may provide a more relevant disease model compared to pre-existing methods and offers a new platform for discovery of novel mechanisms and/or targets and screening of drugs for therapeutic intervention. Third, current evidence of the role of WFS1 and WFS2 in AD is based on the transgenic fly or mouse model with overexpression of human tau or APP mutation. Furthermore, knockdown or deficiency of WFS1 or WFS2 did not change the tau pathology or Aβ pathology, although it does accelerate the neurodegeneration. Due to the disadvantage of those transgenic models, further detailed study of the role of WFS1 and WFS2 in more disease-relevant AD models are warrantied.

Highlights.

WS is a rare neurodegenerative disorder caused by mutations in WFS1 or WFS2 gene.

Molecular mechanisms underlying the loss of neuronal function of WFS1 and WFS2 are addressed.

Emerging evidences reveal common physiopathological mechanisms in WS and AD.

Multidisciplinary approaches for elucidating the role of WFS1 and WFS2 in the pathogenesis of AD are proposed.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant number, AG056673]; the Department of Defense [grant number, W81XWH1910309]; the Alzheimer’s Association [grant number, AARF-17-505009]; and the Neuroscience Research Institute Pilot Award and the Chronic Brain Injury Pilot Award from The Ohio State University.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Completing Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Abreu D, Urano F, 2019. Current landscape of treatments for Wolfram syndrome. Trends Pharmacol. Sci 40, 711–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sheyyab M, Jarrah N, Younis E, Shennak MM, Hadidi A, Awidi A, El-Shanti H, Ajlouni K, 2001. Bleeding tendency in Wolfram syndrome: a newly identified feature with phenotype genotype correlation. Eur. J. Pediatr 160, 243–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfaro R, Doty T, Narayanan A, Lugar H, Hershey T, Pepino MY, 2020. Taste and smell function in Wolfram syndrome. Orphanet J. Rare Dis 15, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aloi C, Salina A, Pasquali L, Lugani F, Perri K, Russo C, Tallone R, Ghiggeri GM, Lorini R, d’Annunzio G, 2012. Wolfram syndrome: new mutations, different phenotype. PLoS One 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amr S, Heisey C, Zhang M, Xia X-J, Shows KH, Ajlouni K, Pandya A, Satin LS, El-Shanti H, Shiang R, 2007. A homozygous mutation in a novel zinc-finger protein, ERIS, is responsible for Wolfram syndrome 2. The American Journal of Human Genetics 81, 673–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angebault C, Fauconnier J, Patergnani S, Rieusset J, Danese A, Affortit CA, Jagodzinska J, Mégy C, Quiles M, Cazevieille C, 2018. ER-mitochondria cross-talk is regulated by the Ca2+ sensor NCS1 and is impaired in Wolfram syndrome. Sci. Signal 11, eaaq1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atouf F, Czernichow P, Scharfmann R, 1997. Expression of neuronal traits in pancreatic beta cells Implication of neuron-restrictive silencing factor/repressor element silencing transcription factor, a neuron-restrictive silencer. J. Biol. Chem 272, 1929–1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett T, Bundey S, 1997. Wolfram (DIDMOAD) syndrome. J. Med. Genet 34, 838–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett TG, Bundey SE, Macleod AF, 1995. Neurodegeneration and diabetes: UK nationwide study of Wolfram (DIDMOAD) syndrome. The Lancet 346, 1458–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff AN, Reiersen AM, Buttlaire A, Al-Lozi A, Doty T, Marshall BA, Hershey T, Group WUWSR, 2015. Selective cognitive and psychiatric manifestations in Wolfram Syndrome. Orphanet J. Rare Dis 10, 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwood DH, He L, Morris SW, McLean A, Whitton C, Thomson M, Walker MT, Woodburn K, Sharp CM, Wright AF, 1996. A locus for bipolar affective disorder on chromosome 4p. Nat. Genet 12, 427–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnycastle LL, Chines PS, Hara T, Huyghe JR, Swift AJ, Heikinheimo P, Mahadevan J, Peltonen S, Huopio H, Nuutila P, 2013. Autosomal dominant diabetes arising from a Wolfram syndrome 1 mutation. Diabetes 62, 3943–3950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxbaum JN, Ye Z, Reixach N, Friske L, Levy C, Das P, Golde T, Masliah E, Roberts AR, Bartfai T, 2008. Transthyretin protects Alzheimer’s mice from the behavioral and biochemical effects of Aβ toxicity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105, 2681–2686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagalinec M, Liiv M, Hodurova Z, Hickey MA, Vaarmann A, Mandel M, Zeb A, Choubey V, Kuum M, Safiulina D, 2016. Role of mitochondrial dynamics in neuronal development: mechanism for Wolfram syndrome. PLoS Biol. 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cembrowski MS, Wang L, Sugino K, Shields BC, Spruston N, 2016. Hipposeq: a comprehensive RNA-seq database of gene expression in hippocampal principal neurons. elife 5, e14997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang NC, Nguyen M, Bourdon J, Risse P-A, Martin J, Danialou G, Rizzuto R, Petrof BJ, Shore GC, 2012. Bcl-2-associated autophagy regulator Naf-1 required for maintenance of skeletal muscle. Hum. Mol. Genet 21, 2277–2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang NC, Nguyen M, Germain M, Shore GC, 2010. Antagonism of Beclin 1-dependent autophagy by BCL-2 at the endoplasmic reticulum requires NAF-1. The EMBO journal 29, 606–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaussenot A, Bannwarth S, Rouzier C, Vialettes B, Mkadem SAE, Chabrol B, Cano A, Labauge P, Paquis-Flucklinger V, 2011. Neurologic features and genotype-phenotype correlation in Wolfram syndrome. Ann. Neurol 69, 501–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y-F, Kao C-H, Chen Y-T, Wang C-H, Wu C-Y, Tsai C-Y, Liu F-C, Yang C-W, Wei Y-H, Hsu M-T, 2009. Cisd2 deficiency drives premature aging and causes mitochondria-mediated defects in mice. Genes Dev. 23, 1183–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YF, Chou TY, Lin IH, Chen CG, Kao CH, Huang GJ, Chen LK, Wang PN, Lin CP, Tsai TF, 2020. Upregulation of Cisd2 attenuates Alzheimer’s-related neuronal loss in mice. The Journal of Pathology 250, 299–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conlan AR, Axelrod HL, Cohen AE, Abresch EC, Zuris J, Yee D, Nechushtai R, Jennings PA, Paddock ML, 2009. Crystal structure of Miner1: The redox-active 2Fe-2S protein causative in Wolfram Syndrome 2. J. Mol. Biol 392, 143–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva DC, Valentão P, Andrade PB, Pereira DM, 2020. Endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling in cancer and neurodegenerative disorders: tools and strategies to understand its complexity. Pharmacol. Res, 104702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Falco M, Manente L, Lucariello A, Baldi G, Fiore P, Laforgia V, Baldi A, Iannaccone A, De Luca A, 2012. Localization and distribution of wolframin in human tissues. Front. Biosci 4, 1986–1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delprat B, Maurice T, Delettre C, 2018. Wolfram syndrome: MAMs’ connection? Cell Death Dis. 9, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Shanti H, Lidral AC, Jarrah N, Druhan L, Ajlouni K, 2000. Homozygosity mapping identifies an additional locus for Wolfram syndrome on chromosome 4q. The American Journal of Human Genetics 66, 1229–1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito Z, Belli L, Toniolo S, Sancesario G, Bianconi C, Martorana A, 2013. Amyloid β, glutamate, excitotoxicity in Alzheimer’s disease: are we on the right track? CNS Neurosci. Ther. 19, 549–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca SG, Fukuma M, Lipson KL, Nguyen LX, Allen JR, Oka Y, Urano F, 2005. WFS1 is a novel component of the unfolded protein response and maintains homeostasis of the endoplasmic reticulum in pancreatic β-cells. J. Biol. Chem 280, 39609–39615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca SG, Ishigaki S, Oslowski CM, Lu S, Lipson KL, Ghosh R, Hayashi E, Ishihara H, Oka Y, Permutt MA, 2010. Wolfram syndrome 1 gene negatively regulates ER stress signaling in rodent and human cells. The Journal of clinical investigation 120, 744–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu H, Hardy J, Duff KE, 2018. Selective vulnerability in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Neurosci 21, 1350–1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu H, Rodriguez GA, Herman M, Emrani S, Nahmani E, Barrett G, Figueroa HY, Goldberg E, Hussaini SA, Duff KE, 2017. Tau pathology induces excitatory neuron loss, grid cell dysfunction, and spatial memory deficits reminiscent of early Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 93, 533–541. e535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gharanei S, Zatyka M, Astuti D, Fenton J, Sik A, Nagy Z, Barrett TG, 2013. Vacuolar-type H+-ATPase V1A subunit is a molecular partner of Wolfram syndrome 1 (WFS1) protein, which regulates its expression and stability. Hum. Mol. Genet 22, 203–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Görlach A, Klappa P, Kietzmann DT, 2006. The endoplasmic reticulum: folding, calcium homeostasis, signaling, and redox control. Antioxidants & redox signaling 8, 1391–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenier J, Meunier I, Daien V, Baudoin C, Halloy F, Bocquet B, Blanchet C, Delettre C, Esmenjaud E, Roubertie A, 2016. WFS1 in optic neuropathies: mutation findings in nonsyndromic optic atrophy and assessment of clinical severity. Ophthalmology 123, 1989–1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Shen S, Song S, He S, Cui Y, Xing G, Wang J, Yin Y, Fan L, He F, 2011. The E3 ligase Smurf1 regulates Wolfram syndrome protein stability at the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem 286, 18037–18047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy C, Khanim F, Torres R, Scott-Brown M, Seller A, Poulton J, Collier D, Kirk J, Polymeropoulos M, Latif F, 1999. Clinical and molecular genetic analysis of 19 Wolfram syndrome kindreds demonstrating a wide spectrum of mutations in WFS1. The American Journal of Human Genetics 65, 1279–1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershey T, Lugar HM, Shimony JS, Rutlin J, Koller JM, Perantie DC, Paciorkowski AR, Eisenstein SA, Permutt MA, Group WUWS, 2012. Early brain vulnerability in Wolfram syndrome. PLoS One 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetz C, Saxena S, 2017. ER stress and the unfolded protein response in neurodegeneration. Nature Reviews Neurology 13, 477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoekel J, Chisholm SA, Al-Lozi A, Hershey T, Tychsen L, Group WUWS, 2014. Ophthalmologic correlates of disease severity in children and adolescents with Wolfram syndrome. Journal of American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus 18, 461–465. e461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann S, Philbrook C, Gerbitz K-D, Bauer MF, 2003. Wolfram syndrome: structural and functional analyses of mutant and wild-type wolframin, the WFS1 gene product. Hum. Mol. Genet 12, 2003–2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh C-J, Weng P-H, Chen J-H, Chen T-F, Sun Y, Wen L-L, Yip P-K, Chu Y-M, Chen Y-C, 2015. Sequence variants of the aging gene CISD2 and the risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association 114, 627–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue H, Tanizawa Y, Wasson J, Behn P, Kalidas K, Bernal-Mizrachi E, Mueckler M, Marshall H, Donis-Keller H, Crock P, 1998. A gene encoding a transmembrane protein is mutated in patients with diabetes mellitus and optic atrophy (Wolfram syndrome). Nat. Genet 20, 143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivask M, Pajusalu S, Reimann E, Kõks S, 2018. Hippocampus and hypothalamus RNA-sequencing of WFS1-deficient mice. Neuroscience 374, 91–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakiuchi C, Ishiwata M, Hayashi A, Kato T, 2006. XBP1 induces WFS1 through an endoplasmic reticulum stress response element-like motif in SH-SY5Y cells. J. Neurochem 97, 545–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanki T, Klionsky DJ, 2009. Mitochondrial abnormalities drive cell death in Wolfram syndrome 2. Cell Res. 19, 922–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano J, Fujinaga R, Yamamoto-Hanada K, Oka Y, Tanizawa Y, Shinoda K, 2009. Wolfram syndrome 1 (Wfs1) mRNA expression in the normal mouse brain during postnatal development. Neurosci. Res 64, 213–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano J, Tanizawa Y, Shinoda K, 2008. Wolfram syndrome 1 (Wfs1) gene expression in the normal mouse visual system. J. Comp. Neurol 510, 1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kõks S, Overall RW, Ivask M, Soomets U, Guha M, Vasar E, Fernandes C, Schalkwyk LC, 2013. Silencing of the WFS1 gene in HEK cells induces pathways related to neurodegeneration and mitochondrial damage. Physiol. Genomics 45, 182–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koks S, Soomets U, Paya-Cano J, Fernandes C, Luuk H, Plaas M, Terasmaa A, Tillmann V, Noormets K, Vasar E, 2009. Wfs1 gene deletion causes growth retardation in mice and interferes with the growth hormone pathway. Physiol. Genomics 37, 249–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo C-Y, Kung W-M, Lin M-S, 2020. Neuronal CISD2 plays a minor anti-inflammatory role in LPS-stimulated neuron-like SH-SY5Y cells. J. Neurol. Sci 408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Morgia C, Maresca A, Amore G, Gramegna LL, Carbonelli M, Scimonelli E, Danese A, Patergnani S, Caporali L, Tagliavini F, 2020. Calcium mishandling in absence of primary mitochondrial dysfunction drives cellular pathology in Wolfram Syndrome. Sci. Rep 10, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang D, Bhatta S, Gerzanich V, Simard JM, 2007. Cytotoxic edema: mechanisms of pathological cell swelling. Neurosurg. Focus 22, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licis A, Davis G, Eisenstein SA, Lugar HM, Hershey T, 2019. Sleep disturbances in Wolfram syndrome. Orphanet J. Rare Dis 14, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C-C, Chiang T-H, Chen W-J, Sun Y-Y, Lee Y-H, Lin M-S, 2015. CISD2 serves a novel role as a suppressor of nitric oxide signalling and curcumin increases CISD2 expression in spinal cord injuries. Injury 46, 2341–2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C-C, Chiang T-H, Sun Y-Y, Lin M-S, 2019. Protective effects of CISD2 and influence of curcumin on CISD2 expression in aged animals and inflammatory cell model. Nutrients 11, 700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Drouet V, Wu JW, Witter MP, Small SA, Clelland C, Duff K, 2012. Trans-synaptic spread of tau pathology in vivo. PLoS One 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu S, Kanekura K, Hara T, Mahadevan J, Spears LD, Oslowski CM, Martinez R, Yamazaki-Inoue M, Toyoda M, Neilson A, 2014. A calcium-dependent protease as a potential therapeutic target for Wolfram syndrome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111, E5292–E5301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugar HM, Koller JM, Rutlin J, Eisenstein SA, Neyman O, Narayanan A, Chen L, Shimony JS, Hershey T, 2019. Evidence for altered neurodevelopment and neurodegeneration in Wolfram syndrome using longitudinal morphometry. Sci. Rep 9, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugar HM, Koller JM, Rutlin J, Marshall BA, Kanekura K, Urano F, Bischoff AN, Shimony JS, Hershey T, 2016. Neuroimaging evidence of deficient axon myelination in Wolfram syndrome. Sci. Rep 6, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luuk H, Koks S, Plaas M, Hannibal J, Rehfeld JF, Vasar E, 2008. Distribution of Wfs1 protein in the central nervous system of the mouse and its relation to clinical symptoms of the Wolfram syndrome. J. Comp. Neurol 509, 642–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luuk H, Plaas M, Raud S, Innos J, Sütt S, Lasner H, Abramov U, Kurrikoff K, Kõks S, Vasar E, 2009. Wfs1-deficient mice display impaired behavioural adaptation in stressful environment. Behav. Brain Res 198, 334–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchi S, Bittremieux M, Missiroli S, Morganti C, Patergnani S, Sbano L, Rimessi A, Kerkhofs M, Parys JB, Bultynck G, 2017. Endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria communication through Ca 2+ signaling: the importance of mitochondria-associated membranes (MAMs), Organelle Contact Sites. Springer, pp. 49–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchi S, Patergnani S, Missiroli S, Morciano G, Rimessi A, Wieckowski MR, Giorgi C, Pinton P, 2018. Mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum calcium homeostasis and cell death. Cell Calcium 69, 62–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall BA, Permutt MA, Paciorkowski AR, Hoekel J, Karzon R, Wasson J, Viehover A, White NH, Shimony JS, Manwaring L, 2013. Phenotypic characteristics of early Wolfram syndrome. Orphanet J. Rare Dis 8, 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga K, Tanabe K, Inoue H, Okuya S, Ohta Y, Akiyama M, Taguchi A, Kora Y, Okayama N, Yamada Y, 2014. Wolfram syndrome in the Japanese population; molecular analysis of WFS1 gene and characterization of clinical features. PLoS One 9, e106906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mijaljica D, Prescott M, Devenish RJ, 2007. Different fates of mitochondria: alternative ways for degradation? Autophagy 3, 4–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozzillo E, Delvecchio M, Carella M, Grandone E, Palumbo P, Salina A, Aloi C, Buono P, Izzo A, D’Annunzio G, 2014. A novel CISD2 intragenic deletion, optic neuropathy and platelet aggregation defect in Wolfram syndrome type 2. BMC Med. Genet 15, 88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odisho T, Zhang L, Volchuk A, 2015. ATF6β regulates the Wfs1 gene and has a cell survival role in the ER stress response in pancreatic β-cells. Exp. Cell Res 330, 111122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallotta MT, Tascini G, Crispoldi R, Orabona C, Mondanelli G, Grohmann U, Esposito S, 2019. Wolfram syndrome, a rare neurodegenerative disease: from pathogenesis to future treatment perspectives. J. Transl. Med 17, 238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattingre S, Tassa A, Qu X, Garuti R, Liang XH, Mizushima N, Packer M, Schneider MD, Levine B, 2005. Bcl-2 antiapoptotic proteins inhibit Beclin 1-dependent autophagy. Cell 122, 927–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira AC, Gray JD, Kogan JF, Davidson RL, Rubin TG, Okamoto M, Morrison JH, McEwen BS, 2017. Age and Alzheimer’s disease gene expression profiles reversed by the glutamate modulator riluzole. Mol. Psychiatry 22, 296–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickett KA, Duncan RP, Hoekel J, Marshall B, Hershey T, Earhart GM, Group WUWS, 2012. Early presentation of gait impairment in Wolfram Syndrome. Orphanet J. Rare Dis 7, 92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaas M, Seppa K, Reimets R, Jagomäe T, Toots M, Koppel T, Vallisoo T, Nigul M, Heinla I, Meier R, 2017. Wfs1-deficient rats develop primary symptoms of Wolfram syndrome: insulin-dependent diabetes, optic nerve atrophy and medullary degeneration. Sci. Rep 7, 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puighermanal E, Castell L, Esteve-Codina A, Melser S, Kaganovsky K, Zussy C, Boubaker-Vitre J, Gut M, Rialle S, Kellendonk C, 2020. Functional and molecular heterogeneity of D2R neurons along dorsal ventral axis in the striatum. Nature Communications 11, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rando TA, Horton JC, Layzer RB, 1992. Wolfram syndrome: evidence of a diffuse neurodegenerative disease by magnetic resonance imaging. Neurology 42, 1220–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendtorff ND, Lodahl M, Boulahbel H, Johansen IR, Pandya A, Welch KO, Norris VW, Arnos KS, Bitner-Glindzicz M, Emery SB, 2011. Identification of p. A684V missense mutation in the WFS1 gene as a frequent cause of autosomal dominant optic atrophy and hearing impairment. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 155, 1298–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigoli L, Di Bella C, 2012. Wolfram syndrome 1 and Wolfram syndrome 2. Curr. Opin. Pediatr 24, 512–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigoli L, Lombardo F, Di Bella C, 2011. Wolfram syndrome and WFS1 gene. Clin. Genet 79, 103–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rondinelli M, Novara F, Calcaterra V, Zuffardi O, Genovese S, 2015. Wolfram syndrome 2: a novel CISD2 mutation identified in Italian siblings. Acta Diabetol. 52, 175–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouzier C, Moore D, Delorme C, Lacas-Gervais S, Ait-El-Mkadem S, Fragaki K, Burté F, Serre V, Bannwarth S, Chaussenot A, 2017. A novel CISD2 mutation associated with a classical Wolfram syndrome phenotype alters Ca2+ homeostasis and ER-mitochondria interactions. Hum. Mol. Genet 26, 1599–1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakakibara Y, Sekiya M, Fujisaki N, Quan X, Iijima KM, 2018. Knockdown of wfs1, a fly homolog of Wolfram syndrome 1, in the nervous system increases susceptibility to age-and stress-induced neuronal dysfunction and degeneration in Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 14, e1007196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samara A, Rahn R, Neyman O, Park KY, Samara A, Marshall B, Dougherty J, Hershey T, 2019. Developmental hypomyelination in Wolfram syndrome: new insights from neuroimaging and gene expression analyses. Orphanet J. Rare Dis 14, 279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlecker C, Boehmerle W, Jeromin A, DeGray B, Varshney A, Sharma Y, Szigeti-Buck K, Ehrlich BE, 2006. Neuronal calcium sensor-1 enhancement of InsP 3 receptor activity is inhibited by therapeutic levels of lithium. The Journal of clinical investigation 116, 1668–1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Kastner R, 2015. Genomic approach to selective vulnerability of the hippocampus in brain ischemia–hypoxia. Neuroscience 309, 259–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Kastner R, Kreczmanski P, Preising M, Diederen R, Schmitz C, Reis D, Blanks J, Dorey CK, 2009. Expression of the diabetes risk gene wolframin (WFS1) in the human retina. Exp. Eye Res 89, 568–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scolding NJ, Kellar-Wood HF, Shaw C, Shneerson JM, Antount N, 1996. Wolfram syndrome: hereditary diabetes mellitus with brainstem and optic atrophy. Annals of Neurology: Official Journal of the American Neurological Association and the Child Neurology Society 39, 352–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senft D, Ze’ev AR, 2015. UPR, autophagy, and mitochondria crosstalk underlies the ER stress response. Trends Biochem. Sci 40, 141–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seppa K, Toots M, Reimets R, Jagomäe T, Koppel T, Pallase M, Hasselholt S, Mikkelsen MK, Nyengaard JR, Vasar E, 2019. GLP-1 receptor agonist liraglutide has a neuroprotective effect on an aged rat model of Wolfram syndrome. Sci. Rep 9, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha P, Mousa A, Heintz N, 2015. Layer 2/3 pyramidal cells in the medial prefrontal cortex moderate stress induced depressive behaviors. Elife 4, e08752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strom TM, Hörtnagel K, Hofmann S, Gekeler F, Scharfe C, Rabl W, Gerbitz KD, Meitinger T, 1998. Diabetes insipidus, diabetes mellitus, optic atrophy and deafness (DIDMOAD) caused by mutations in a novel gene (wolframin) coding for a predicted transmembrane protein. Hum. Mol. Genet 7, 2021–2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukumaran P, Schaar A, Sun Y, Singh BB, 2016. Functional role of TRP channels in modulating ER stress and autophagy. Cell Calcium 60, 123–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C, Kitamura T, Yamamoto J, Martin J, Pignatelli M, Kitch LJ, Schnitzer MJ, Tonegawa S, 2015. Distinct speed dependence of entorhinal island and ocean cells, including respective grid cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112, 9466–9471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sütt S, Altpere A, Reimets R, Visnapuu T, Loomets M, Raud S, Salum T, Mahlapuu R, Kairane C, Zilmer M, 2015. Wfs1-deficient animals have brain-region-specific changes of Na+, K+-ATPase activity and mRNA expression of α1 and β1 subunits. J. Neurosci. Res 93, 530–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki N, Hosoya M, Oishi N, Okano H, Fujioka M, Ogawa K, 2016. Expression pattern of wolframin, the WFS1 (Wolfram syndrome-1 gene) product, in common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) cochlea. Neuroreport 27, 833–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift M, Swift R, 2005. Wolframin mutations and hospitalization for psychiatric illness. Mol. Psychiatry 10, 799–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift M, Swift RG, 2000. Psychiatric disorders and mutations at the Wolfram syndrome locus. Biol. Psychiatry 47, 787–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift R, Polymeropoulos M, Torres R, Swift M, 1998. Predisposition of Wolfram syndrome heterozygotes to psychiatric illness. Mol. Psychiatry 3, 86–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift R, Sadler D, Swift M, 1990. Psychiatric findings in Wolfram syndrome homozygotes. The Lancet 336, 667–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda K, Inoue H, Tanizawa Y, Matsuzaki Y, Oba J, Watanabe Y, Shinoda K, Oka Y, 2001. WFS1 (Wolfram syndrome 1) gene product: predominant subcellular localization to endoplasmic reticulum in cultured cells and neuronal expression in rat brain. Hum. Mol. Genet 10, 477–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takei D, Ishihara H, Yamaguchi S, Yamada T, Tamura A, Katagiri H, Maruyama Y, Oka Y, 2006. WFS1 protein modulates the free Ca2+ concentration in the endoplasmic reticulum. FEBS Lett. 580, 5635–5640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tekko T, Lilleväli K, Luuk H, Sütt S, Truu L, Örd T, Möls M, Vasar E, 2014. Initiation and developmental dynamics of Wfs1 expression in the context of neural differentiation and ER stress in mouse forebrain. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci 35, 80–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai P-H, Chien Y, Chuang J-H, Chou S-J, Chien C-H, Lai Y-H, Li H-Y, Ko Y-L, Chang Y-L, Wang C-Y, 2015. Dysregulation of mitochondrial functions and osteogenic differentiation in Cisd2-deficient murine induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 24, 2561–2576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uddin M, Stachowiak A, Mamun AA, Tzvetkov NT, Takeda S, Atanasov AG, Bergantin LB, Abdel-Daim MM, Stankiewicz AM, 2018. Autophagy and Alzheimer’s disease: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic implications. Front. Aging Neurosci 10, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda K, Kawano J, Takeda K, Yujiri T, Tanabe K, Anno T, Akiyama M, Nozaki J, Yoshinaga T, Koizumi A, 2005. Endoplasmic reticulum stress induces Wfs1 gene expression in pancreatic β-cells via transcriptional activation. European journal of endocrinology 153, 167–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urano F, 2016. Wolfram syndrome: diagnosis, management, and treatment. Curr. Diab. Rep 16, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visnapuu T, Plaas M, Reimets R, Raud S, Terasmaa A, Kõks S, Sütt S, Luuk H, Hundahl CA, Eskla K-L, 2013a. Evidence for impaired function of dopaminergic system in Wfs1-deficient mice. Behav. Brain Res 244, 90–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visnapuu T, Raud S, Loomets M, Reimets R, Sütt S, Luuk H, Plaas M, Kõks S, Volke V, Alttoa A, 2013b. Wfs1-deficient mice display altered function of serotonergic system and increased behavioral response to antidepressants. Front. Neurosci 7, 132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C-H, Chen Y-F, Wu C-Y, Wu P-C, Huang Y-L, Kao C-H, Lin C-H, Kao L-S, Tsai T-F, Wei Y-H, 2014a. Cisd2 modulates the differentiation and functioning of adipocytes by regulating intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis. Hum. Mol. Genet 23, 4770–4785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C-H, Kao C-H, Chen Y-F, Wei Y-H, Tsai T-F, 2014b. Cisd2 mediates lifespan: is there an interconnection among Ca2+ homeostasis, autophagy, and lifespan? Free Radic. Res 48, 1109–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Wang W, Li L, Perry G, Lee H. g., Zhu X, 2014c. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease 1842, 1240–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waschbisch A, Volbers B, Struffert T, Hoyer J, Schwab S, Bardutzky J, 2011. Primary diagnosis of Wolfram syndrome in an adult patient—Case report and description of a novel pathogenic mutation. J. Neurol. Sci 300, 191–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley SE, Andreyev AY, Divakaruni AS, Karisch R, Perkins G, Wall EA, van der Geer P, Chen YF, Tsai TF, Simon MI, 2013. Wolfram Syndrome protein, Miner1, regulates sulphydryl redox status, the unfolded protein response, and Ca2+ homeostasis. EMBO Mol. Med 5, 904–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley SE, Murphy AN, Ross SA, van der Geer P, Dixon JE, 2007. MitoNEET is an iron-containing outer mitochondrial membrane protein that regulates oxidative capacity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104, 5318–5323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods NK, Padmanabhan J, 2012. Neuronal calcium signaling and Alzheimer’s disease, Calcium signaling. Springer, pp. 1193–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C-Y, Chen Y-F, Wang C-H, Kao C-H, Zhuang H-W, Chen C-C, Chen L-K, Kirby R, Wei Y-H, Tsai S-F, 2012. A persistent level of Cisd2 extends healthy lifespan and delays aging in mice. Hum. Mol. Genet 21, 3956–3968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada T, Ishihara H, Tamura A, Takahashi R, Yamaguchi S, Takei D, Tokita A, Satake C, Tashiro F, Katagiri H, 2006. WFS1-deficiency increases endoplasmic reticulum stress, impairs cell cycle progression and triggers the apoptotic pathway specifically in pancreatic β-cells. Hum. Mol. Genet 15, 1600–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi S, Ishihara H, Tamura A, Yamada T, Takahashi R, Takei D, Katagiri H, Oka Y, 2004. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and N-glycosylation modulate expression of WFS1 protein. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 325, 250–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto H, Hofmann S, Hamasaki DI, Yamamoto H, Kreczmanski P, Schmitz C, Parel J-M, Schmidt-Kastner R, 2006. Wolfram syndrome 1 (WFS1) protein expression in retinal ganglion cells and optic nerve glia of the cynomolgus monkey. Exp. Eye Res 83, 1303–1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto S, Wajima T, Hara Y, Nishida M, Mori Y, 2007. Transient receptor potential channels in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease 1772, 958–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurimoto S, Hatano N, Tsuchiya M, Kato K, Fujimoto T, Masaki T, Kobayashi R, Tokumitsu H, 2009. Identification and characterization of wolframin, the product of the wolfram syndrome gene (WFS1), as a novel calmodulin-binding protein. Biochemistry 48, 3946–3955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatyka M, Da Silva Xavier G, Bellomo EA, Leadbeater W, Astuti D, Smith J, Michelangeli F, Rutter GA, Barrett TG, 2015. Sarco (endo) plasmic reticulum ATPase is a molecular partner of Wolfram syndrome 1 protein, which negatively regulates its expression. Hum. Mol. Genet 24, 814–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Z, Zhang C, Zhang K, 2011. Measurement of ER stress response and inflammation in the mouse model of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, Methods Enzymol. Elsevier, pp. 329–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]