Abstract

Background:

Leadless pacemakers (LPs) provide ventricular pacing without the risks associated with transvenous leads and device pockets. LPs are appealing for patients who need pacing, but do not need defibrillator or cardiac resynchronization therapy. Most implanted LPs provide right ventricular pacing without atrioventricular synchrony (VVIR mode). The Mode Selection Trial in Sinus Node Dysfunction Trial (MOST) showed similar outcomes in patients randomized to dual chamber (DDDR) vs ventricular pacing (VVIR). We compared outcomes by pacing mode in LP-eligible patients from MOST.

Methods:

Patients enrolled in the MOST study with an LVEF >35%, QRSd <120ms and no history of ventricular arrhythmias or prior implantable cardioverter defibrillators were included (LP-eligible population). Cox proportional hazards models were used to test the association between pacing mode and death, stroke or heart failure hospitalization and atrial fibrillation (AF).

Results:

Of the 2,010 patients enrolled in MOST, 1,284 patients (64%) met inclusion criteria. Baseline characteristics were well balanced across included patients randomized to DDDR (N=630) and VVIR (N=654). Over four years of follow-up, there was no association between pacing mode and death, stroke or heart failure hospitalization (VVIR HR 1.28 [0.92–1.75]). VVIR pacing was associated with higher risk of AF (HR 1.32 [1.08–1.61], p=0.007), particularly in patients with no history of AF (HR 2.38 [1.52–3.85], p<0.001).

Conclusion:

In patients without reduced LVEF or prolonged QRS duration who would be eligible for LP, DDDR and VVIR pacing demonstrated similar rates of death, stroke or heart failure hospitalization; however, VVIR pacing significantly increased the risk of AF development.

Keywords: pacemaker, leadless pacing, outcomes, heart failure, atrial fibrillation

Introduction:

Complications occur in approximately 10% of traditional transvenous pacemaker implantations with the majority of complications being lead-related.1 Leadless pacemakers (LP) are a safe and effective method of ventricular pacing without the need for implantation of transvenous leads and pulse generators.2–5 Currently, LPs do not have the ability to function as implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) or deliver cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT). Therefore, patients who have a need for a pacemaker and do not meet indications for either ICD or CRT are the ideal candidates for LPs.

First-generation LPs are self-contained pacemakers that provide asynchronous right ventricular (RV) pacing, although a very recently approved second-generation device is able to provide VDD pacing in some patients with AV block.6,7 LPs that provide atrial pacing are in development but are not yet commercially available. In patients with sinus node dysfunction, implantation of an LP would provide asynchronous RV pacing only. The effect of pacing mode in patients with sinus node dysfunction was evaluated in the Mode Selection Trial in Sinus Node Dysfunction (MOST), which randomized patients to dual chamber pacing (DDDR mode) or single chamber pacing (VVIR mode). The MOST trial demonstrated similar rates of stroke free survival in both arms; however, DDDR paced patients had lower rates of atrial fibrillation (AF) and heart failure (HF) hospitalizations.8 In patients with QRS duration (QRSd) <120ms, a high amount of ventricular pacing in DDDR was also associated with higher rates of AF and HF hospitalizations.9 Frequent ventricular pacing has also been associated with the development of pacemaker syndrome among patients with sinus rhythm treated with VVIR pacing.10 Understanding how pacing mode affects these outcomes in patients without indications for an ICD or CRT will inform clinical decision making regarding the risks and benefits of LP implantation for patients with sick sinus syndrome. In this study, we analyzed patients enrolled in the MOST trial without substantial left ventricular (LV) dysfunction and QRSd <120ms to evaluate the effect of pacing mode on clinical outcomes in a LP-eligible population.

Methods:

Study Population

The details of the MOST trial have been previously published.8 Briefly, 2,010 patients with sick sinus syndrome were enrolled at 91 US sites between September 25, 1995 and October 13, 1999 and implanted with a dual-chamber pacing system. Patients were randomized to VVIR or DDDR pacing mode (patient blinded) at time of implantation and were followed four times during the first year and biannually thereafter. To better emulate an LP-eligible population, we applied additional exclusion criteria. Patients with moderately reduced or unknown LV function at baseline (LV ejection fraction [EF] ≤ 35%, or “moderate” or “severe” dysfunction, or LVEF unknown), a personal history of ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation, or those with a previous ICD implantation were excluded due to their need for defibrillation capabilities from their device. Additionally, patients with a QRSd ≥ 120ms or unknown were excluded due to their potential need for cardiac resynchronization therapy. After these exclusions were applied, 1,284 patients enrolled from 89 sites remained (630 randomized to VVIR, 654 randomized to DDDR). This study was approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of interest was the composite of death, stroke, or heart failure (HF) hospitalization. Secondary outcomes included the components of the composite endpoint as well as the diagnosis of pacemaker syndrome, and the first episode of AF. The occurrence of AF subsequent to device implantation was stratified by patient’s history of AF prior to device implantation. Pacemaker syndrome was only reported on patients assigned to VVIR mode. Thus, this outcome was not compared across pacing modes, but rather the rate of pacemaker syndrome in this population is reported.

Statistical Analyses

Demographic and patient baseline characteristics among included patients were compared between patients randomized to VVIR and DDDR pacing modes. Categorical variables were compared using chi-square tests and continuous variables were compared with the Wilcoxon rank sum test. All analyses were conducted using an intention to treat approach.

Outcomes were compared by pacing mode using Kaplan-Meier curves and Cox proportional hazards models adjusting for variables identified as significant predictors of outcomes using backward selection and an inclusion threshold of alpha = 0.05. For the outcome of AF occurrence, independent models were generated for patients with and without a clinical history of AF at time of randomization. A robust covariance estimate was included in each model to account for within site correlation. Because pacing percentage is typically not known at the time of device implantation, it was not included as a covariate in the multivariable Cox models; however, because this variable is known to have a significant impact on the key outcomes of HF hospitalization and AF,9 we conducted a sensitivity analysis in which pacing percentage was included in the above described models. Ventricular pacing percentage data was treated as a time-dependent covariate with last recorded value carried forward to the last date of follow up.

Results:

Study Population

Among 1,284 patients with LVEF >35%, QRSd <120 ms and no history of ventricular arrhythmias or prior ICD, 630 were randomized to VVIR mode and 654 were randomized to DDDR mode. Demographics and baseline characteristics by pacing mode are shown in Table 1. The median age was 74 years (interquartile range [IQR] 67–80) and 51.9% of patients were female. Mild heart failure symptoms (New York Heart Association [NYHA] class I or II) were present in 86.3% of patients. Compared with the overall MOST trial population, this subpopulation had less cardiomyopathy (4.9% vs 11.9%) but was otherwise similar. Baseline characteristics were well balanced by pacing mode with the exceptions of higher rates of cardiomyopathy (6.3% vs 3.5%, p=0.021) and diabetes (21.7% vs 17.1%, p =0.039) among patients randomized to DDDR mode.

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics by pacing mode

| Characteristic | Overall N=1,284 |

VVIR N=630 |

DDDR N=654 |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 74 (67–80) | 74 (67–80) | 73 (66–79) | 0.3839 |

| Female | 667 (51.9) | 339 (53.8) | 328 (50.2) | 0.1898 |

| Non-white race | 202 (15.7) | 96 (15.2) | 106 (16.2) | 0.6333 |

| Hypertension | 789 (61.4) | 377 (59.8) | 412 (63.0) | 0.2455 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 478 (37.4) | 231 (36.8) | 247 (37.9) | 0.7004 |

| Current smoker | 115 (9.0) | 55 (8.8) | 60 (9.2) | 0.5406 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 261 (20.3) | 117 (18.6) | 144 (22.0) | 0.1285 |

| Prior heart failure | 178 (13.9) | 81 (12.9) | 97 (14.9) | 0.3008 |

| New York Heart Association class I or II heart failure | 1,092 (86.3) | 545 (87.8) | 547 (84.8) | 0.1268 |

| Cardiomyopathy | 63 (4.9) | 22 (3.5) | 41 (6.3) | 0.0209 |

| Prior stroke | 134 (10.4) | 60 (9.5) | 74 (11.3) | 0.2940 |

| Diabetes | 250 (19.5) | 108 (17.1) | 142 (21.7) | 0.0387 |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | 125 (9.7) | 56 (8.9) | 69 (10.6) | 0.3153 |

| Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty | 158 (12.3) | 73 (11.6) | 85 (13.0) | 0.4360 |

| Coronary-artery bypass grafting | 212 (16.5) | 105 (16.7) | 107 (16.4) | 0.8827 |

| Other cardiac surgery | 29 (2.3) | 16 (2.5) | 13 (2.0) | 0.5030 |

| Any supraventricular tachycardia | 706 (55.0) | 337 (53.5) | 369 (56.4) | 0.2914 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 573 (44.6) | 267 (42.4) | 306 (46.8) | 0.1122 |

| Other atrial tachycardia | 123 (9.6) | 60 (9.5) | 63 (9.6) | 0.9470 |

| Complete heart block | 49 (3.8) | 29 (4.6) | 20 (3.1) | 0.1486 |

| Second-degree heart block | 82 (6.4) | 38 (6.0) | 44 (6.7) | 0.6101 |

| Prolonged atrioventricular interval | 122 (9.5) | 65 (10.3) | 57 (8.7) | 0.3278 |

| Other heart block | 22 (1.7) | 12 (1.9) | 10 (1.5) | 0.6040 |

| Vasovagal syndromes | 41 (3.2) | 23 (3.7) | 18 (2.8) | 0.3591 |

Continuous variables are presented as median (inter-quartile range).

Categorical variables are presented as frequencies (percentages).

Clinical Outcomes by Pacing Mode

Over four years of follow up, there were 198 deaths, 54 strokes and 112 HF hospitalizations. Of the 630 patients randomized to VVIR mode, 120 (19.0%) developed pacemaker syndrome. A total of 303 (23.6%) patients experienced one of the primary endpoints (death, stroke or HF hospitalization). Event rates according to the randomized pacing mode are shown in Figure 1. The multivariable Cox-proportional hazard model for the primary endpoint was adjusted for Charlson Comorbidity Index,11 age, Karnofsky performance status score,12 mini-mental state exam score, presence of lower extremity edema, heart rate, sex, prior congestive HF, NYHA class, antiarrhythmic use at admission, and prior myocardial infarction. There was no association between pacing mode and the primary outcome (VVIR hazard ratio [HR]: 1.28 [0.92–1.75], p=0.14) (Table 2A). Similarly, no relationship was shown between pacing mode and the individual components of the composite endpoint, including death (HR 1.11 [0.77–1.61]), stroke (HR 1.33 [0.81–2.17]), and HF hospitalization (HR 1.35 [0.94–1.96]).

Figure 1:

Product-Limit Survival Curves by Pacing Mode for Death, Stroke or Heart Failure Hospitalization

Table 2A:

Adjusted Hazard Models (Baseline Variables Only)

| Outcome | VVIR HR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Outcome | 1.28 (0.92–1.75) | 0.14 |

| Death | 1.11 (0.77–1.61) | 0.56 |

| Stroke | 1.33 (0.81–2.17) | 0.25 |

| HF Hospitalization | 1.35 (0.94–1.96) | 0.09 |

| AF- All patients | 1.31 (1.08–1.61) | 0.007 |

| AF- Patients with No AF History | 2.38 (1.52–3.85) | 0.0002 |

AF = atrial fibrillation; CI = confidence interval; HF = heart failure; HR = hazard ratio

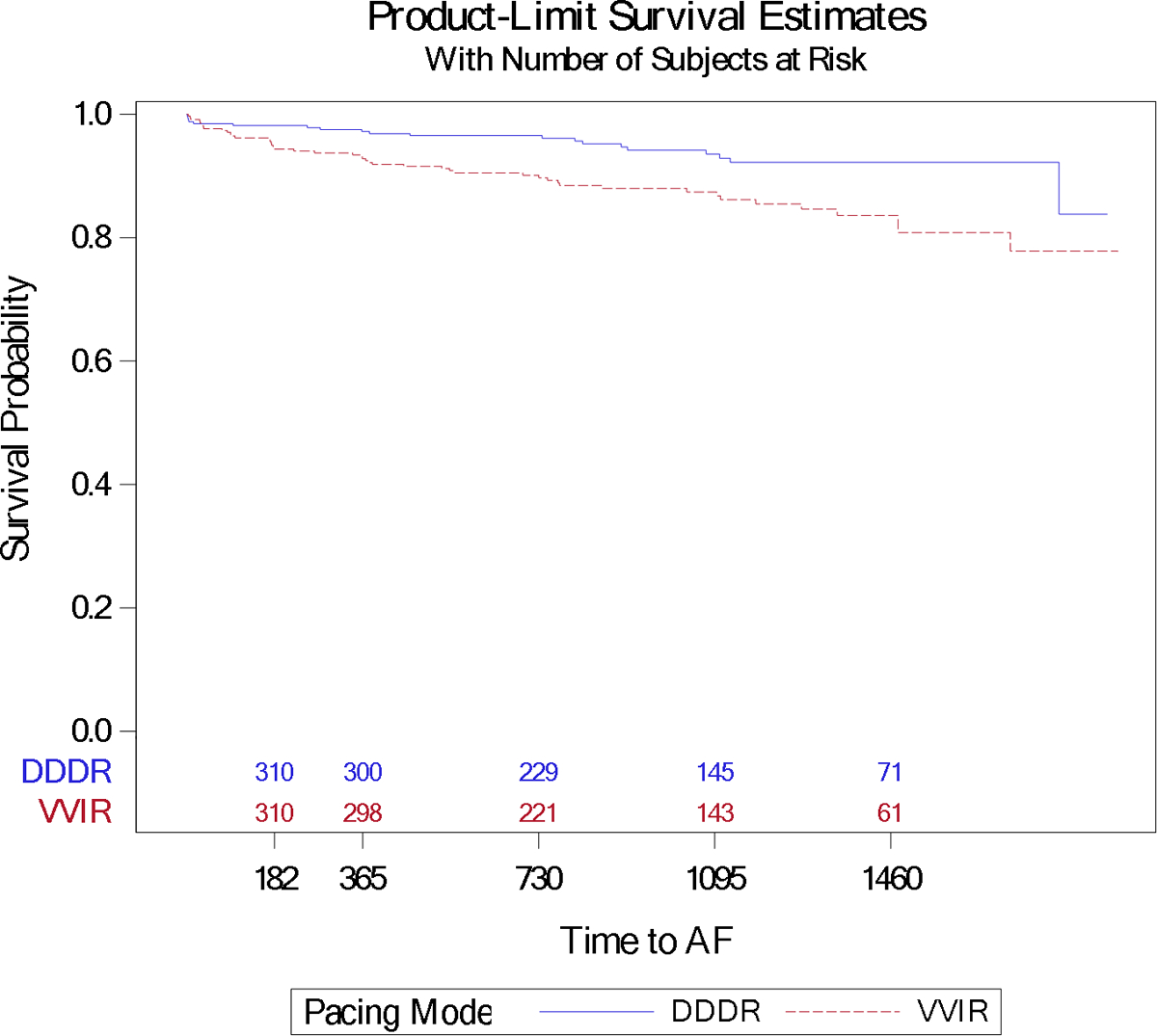

AF occurred in a total of 313 patients (24.4%), including 66 patients (9.9%) who had no known history of AF. AF event rates are shown for all patients (Figure 2A) and those with no known history of AF (Figure 2B). The multivariable Cox-proportional hazard model for the occurrence of AF was adjusted for prior AF/flutter, mitral regurgitation murmur, weight, hypercholesterolemia, age, prior atrioventricular (AV) block, and hypertension. Among patients with no history of AF, the model was adjusted for Charlson Comorbidity Index, age, hypercholesterolemia, African-American race, prior AV block, and cardiomyopathy. VVIR pacing mode was associated with a higher risk of AF (HR 1.32 [1.08–1.61], p=0.007), particularly among those with no history of AF (HR 2.38 [1.52–3.85], p<0.001) (Table 2A).

Figure 2A:

Product-Limit Survival Curves by Pacing Mode for Atrial Fibrillation Episodes among All Patients

Figure 2B:

Product-Limit Survival Curves by Pacing Mode for Atrial Fibrillation Episodes Among Patients with No Known History of Atrial Fibrillation

Sensitivity Analysis

Frequency of ventricular pacing data was available in 1,198 (93.3%) of the 1,284 included patients. The average pacing burden in the study population was 65 ± 33%. Patients in the DDDR mode had an average ventricular pacing burden of 74 ± 31%, whereas patients in the VVIR mode had a pacing burden of 55 ± 34%. When the multivariable hazards models were adjusted for pacing burden there were no differences in the primary outcome, death, or stroke (Table 2B); however, there was a higher rate of HF hospitalization among patients randomized to VVIR pacing (HR 1.69 [1.11–2.56], p=0.02).

Table 2B:

Adjusted Hazard Models (Including %V pacing)

| Outcome | VVIR HR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Outcome | 1.32 (0.97–1.78) | 0.07 |

| Death | 1.01 (0.74–1.39) | 0.94 |

| Stroke | 1.33 (0.76–2.33) | 0.32 |

| HF Hospitalization | 1.69 (1.11–2.56) | 0.02 |

| AF- All patients | 1.47 (1.12–1.92) | 0.005 |

| AF- Patients with No AF History | 3.22 (1.96–5.26) | <0.0001 |

AF = atrial fibrillation; CI = confidence interval; HF = heart failure; HR = hazard ratio

When adjusted for ventricular pacing burden, multivariable models for AF occurrence showed similar trends as the base model. VVIR pacing mode was associated with a higher risk of AF (HR 1.47 [1.12–1.92], p=0.005), particularly among those with no history of AF (HR 3.22 [1.96–5.26], p<0.0001) (Table 2B).

Discussion:

In this retrospective analysis of the MOST study focused on patients without reduced LVEF or prolonged QRS duration, pacing mode was not associated with the composite endpoint of death, stroke or HF hospitalization. However, VVIR pacing was associated with a higher hazard of AF and a greater than two-fold increase in hazard of the development of new-onset AF. In patients with sick sinus syndrome who might be considered for a LP, VVIR pacing may not influence the risk of death, stroke or HF hospitalization, but may carry an increased risk of AF particularly among those with no known history of AF.

In many respects, LP is an innovation that simplifies device implant and pacing but provides RV-only pacing. Prospective studies of LPs have demonstrated good safety profiles and acute implant success rates with low procedural complication rates; however, there have been no randomized outcome studies comparing single RV LPs to dual chamber devices. Currently, LPs are used primarily to treat patients with persistent atrial fibrillation and bradycardia; however, a significant minority of LPs are implanted for sinus node dysfunction, bradycardia with infrequent pauses or syncope (15% of patients in LEADLESS, 35.4% in LEADLESS-II, 17.5% in the Micra Transcatheter Pacing Study, and 8% in the Micra Post Approval Registry).2–5 We took advantage of the randomized treatments inherent to the MOST study and examined outcomes in those patients who would have been eligible for RV LP. The results of this analysis in MOST suggest that use of VVIR pacing with LP in this population would likely not have impacted death, stroke or HF hospitalization rates, but may have increased the risk of AF. Interestingly, sick sinus syndrome patients in the DANPACE trial randomized to AAIR pacing also demonstrated higher rates of AF compared with those randomized to DDDR pacing.13 The authors of that study hypothesized that this finding was driven by prolonged AV conduction and possibly more AV dyssynchrony in the AAIR arm highlighting the importance of the AV relationship in the risk of developing subsequent AF. In the model controlling for pacing burden, VVIR pacing was associated with a higher hazard of HF hospitalization despite a lower overall pacing burden compared with DDDR pacing; however, this was a sensitivity analysis using data not always available at the time of pacemaker implantation (ventricular pacing burden) and is hypothesis generating. The majority of patients enrolled in these trials and post-approval registries had a history of AF (67% in LEADLESS, 77% in LEADLESS-II, 73% in the Micra Transcatheter Pacing Study, 67% in the Micra Post Approval Registry); however, a substantial minority of patients did not have a history of AF.14 These patients may be at increased risk for developing AF with a VVIR LP pacing system. Additionally, the lack of an atrial lead may delay identification of subclinical AF which carries a substantial risk of ischemic stroke or systemic embolism.15

The MARVEL study demonstrated that using an accelerometer based pacing algorithm designed to detect atrial contraction (VDD pacing) in LPs resulted in significantly higher AV synchrony compared to patients with VVI pacing.6 The MARVEL-2 study evaluated an updated algorithm which showed an improvement in median AV synchrony from 27% to 94% using VDD pacing compared to VVIR pacing.7 We were unable to directly compare VVI pacing to VDD pacing in this study as only seven patients randomized to DDDR had 0% atrial pacing (which would be the equivalent of VDD pacing). Our results reflect a comparison of VVI pacing and DDDR pacing with an average amount of atrial pacing (58% ± 32% in this population). While there have not yet been cardiovascular outcomes studies of this algorithm, the results of the present study suggest that maintenance of AV synchrony may help reduce the risk of developing AF. Due to the lower burden of intravascular foreign material, LPs are an attractive option for patients at higher risk for infection (e.g. immunocompromised patients) and those for whom vascular access is of critical importance (e.g. renal failure patients with a need for current or future dialysis). Current generation LPs do not routinely identify AF episodes;16 therefore, consideration of AF risk when selecting a pacing device and mode is of particular importance in these patients who are often at high risk for thromboembolic events given AF paroxysms may remain undetected and not appropriately treated with anticoagulation therapy.17

Limitations

This is a sub-study of a randomized trial and the introduction of additional exclusion criteria may have introduced additional confounding. While the balance of baseline characteristics was similar to the trial as a whole, there were differences in rates of cardiomyopathy and diabetes. However, patients randomized to DDDR had more of these comorbidities which would bias the results towards the null. Additionally, the MOST study was conducted before the advent of algorithms designed to reduce RV pacing burden.18 Modern devices using these algorithms may have even lower RV pacing percentages, which could result in an even larger benefit with DDDR pacing. For patients in the VVIR group, AF incidence was based on clinical presentation with AF; thus, the incidence of asymptomatic AF may be underestimated in this group and the association between VVIR pacing and AF incidence may be more substantial than shown in this study.

Conclusion:

In patients without reduced LVEF or prolonged QRS duration, DDDR and VVIR pacing demonstrated similar rates of death, stroke, and HF hospitalization. VVIR pacing was associated with a significantly higher risk of developing AF, particularly among patients without a history of AF. Atrial-asynchronous ventricular pacing in an LP-eligible population may not affect the risk of death, stroke, or HF hospitalization, but may confer an increased risk of AF development.

Disclosures:

ZL is supported by NIH T32 training grant #5T32HL069749, receives grant support from Boston Scientific, and serves a consultant to Huxley Medical Inc. RN is supported in part by NIH T32 training grant #HL079896. ASH reports no conflicts of interest. BDA receives grants for clinical research from Abbott and Boston Scientific and serves as a consultant to Abbott, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Biosense Webster, and Siemens. CGFM reports no disclosures. KPJ receives research support and serves as a consultant for Medtronic. SDP reports research support from Boston Scientific, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, and Janssen Pharmaceuticals; consulting/advisory board support from Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Phillips, and Zoll.. GAL reports no disclosures. JPP receives grants for clinical research from Abbott, American Heart Association, Boston Scientific, Gilead, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and the NHLBI and serves as a consultant to Abbott, Allergan, ARCA Biopharma, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Johnson & Johnson, LivaNova, Medtronic, Milestone, Oliver Wyman Health, Sanofi, Philips, and Up-to-Date.

Abbreviations:

- AF

Atrial fibrillation

- AV

Atrioventricular

- CRT

Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy

- EF

Ejection Fraction

- HF

Heart failure

- HR

Hazard ratio

- ICD

Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator

- IQR

interquartile range

- LP

Leadless pacemaker

- LV

left ventricular

- MOST

Mode Selection Trial in Sinus Node Dysfunction

- NYHA

New York Heat Assoication

- RV

Right ventricular

References:

- 1.Udo EO, Zuithoff NP, van Hemel NM, et al. Incidence and predictors of short- and long-term complications in pacemaker therapy: the FOLLOWPACE study. Heart rhythm. 2012;9(5):728–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reddy VY, Exner DV, Cantillon DJ, et al. Percutaneous Implantation of an Entirely Intracardiac Leadless Pacemaker. The New England journal of medicine. 2015;373(12):1125–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reynolds D, Duray GZ, Omar R, et al. A Leadless Intracardiac Transcatheter Pacing System. The New England journal of medicine. 2016;374(6):533–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts PR, Clementy N, Al Samadi F, et al. A leadless pacemaker in the real-world setting: The Micra Transcatheter Pacing System Post-Approval Registry. Heart rhythm. 2017;14(9):1375–1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reddy VY, Knops RE, Sperzel J, et al. Permanent leadless cardiac pacing: results of the LEADLESS trial. Circulation. 2014;129(14):1466–1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chinitz L, Ritter P, Khelae SK, et al. Accelerometer-based atrioventricular synchronous pacing with a ventricular leadless pacemaker: Results from the Micra atrioventricular feasibility studies. Heart rhythm. 2018;15(9):1363–1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steinwender C, Khelae SK, Garweg C, et al. Atrioventricular synchronous pacing using a leadless ventricular pacemaker: Results from the MARVEL 2 study. JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology. 2019:1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lamas GA, Lee KL, Sweeney MO, et al. Ventricular pacing or dual-chamber pacing for sinus-node dysfunction. The New England journal of medicine. 2002;346(24):1854–1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sweeney MO, Hellkamp AS, Ellenbogen KA, et al. Adverse effect of ventricular pacing on heart failure and atrial fibrillation among patients with normal baseline QRS duration in a clinical trial of pacemaker therapy for sinus node dysfunction. Circulation. 2003;107(23):2932–2937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Link MS, Hellkamp AS, Estes NA 3rd, et al. High incidence of pacemaker syndrome in patients with sinus node dysfunction treated with ventricular-based pacing in the Mode Selection Trial (MOST). Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2004;43(11):2066–2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. Journal of chronic diseases. 1987;40(5):373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crooks V, Waller S, Smith T, Hahn TJ. The use of the Karnofsky Performance Scale in determining outcomes and risk in geriatric outpatients. Journal of gerontology. 1991;46(4):M139–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nielsen JC, Thomsen PE, Højberg S, et al. A comparison of single-lead atrial pacing with dual-chamber pacing in sick sinus syndrome. European heart journal. 2011;32(6):686–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piccini JP, Stromberg K, Jackson KP, et al. Patient selection, pacing indications, and subsequent outcomes with de novo leadless single-chamber VVI pacing. Europace : European pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac electrophysiology : journal of the working groups on cardiac pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac cellular electrophysiology of the European Society of Cardiology. 2019;21(11):1686–1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Healey JS, Connolly SJ, Gold MR, et al. Subclinical Atrial Fibrillation and the Risk of Stroke. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;366(2):120–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garweg C, Sheldon TJ, Chinitz L, Ritter P, Steinwender C, Willems R. Response to atrial arrhythmias in an atrioventricular synchronous ventricular leadless pacemaker: A case report in a paroxysmal atrial fibrillation patient. HeartRhythm case reports. 2018;4(12):561–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ovbiagele B, Bath PM, Cotton D, Sha N, Diener H-C. Low Glomerular Filtration Rate, Recurrent Stroke Risk, and Effect of Renin–Angiotensin System Modulation. Stroke. 2013;44(11):3223–3225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sweeney MO, Hellkamp AS, Lee KL, Lamas GA. Association of prolonged QRS duration with death in a clinical trial of pacemaker therapy for sinus node dysfunction. Circulation. 2005;111(19):2418–2423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]