Abstract

Amelogenin, a protein critical to enamel formation, is presented as a model for understanding how the structure of biomineralization proteins orchestrate biomineral formation. Amelogenin is the predominant biomineralization protein in the early stages of enamel formation and contributes to the controlled formation of hydroxyapatite (HAP) enamel crystals. The resulting enamel mineral is one of the hardest tissues in the human body and one of the hardest biominerals in nature. Structural studies have been hindered by the lack of techniques to evaluate surface adsorbed proteins and by amelogenin’s disposition to self-assemble. Recent advancements in solution and solid state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, atomic force microscopy (AFM), and recombinant isotope labeling strategies are now enabling detailed structural studies. These recent studies, coupled with insights from techniques such as CD and IR spectroscopy and computational methodologies, are contributing to important advancements in our structural understanding of amelogenesis. In this review we focus on recent advances in solution and solid state NMR spectroscopy and in situ AFM that reveal new insights into the secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structure of amelogenin by itself and in contact with HAP. These studies have increased our understanding of the interface between amelogenin and HAP and how amelogenin controls enamel formation.

Keywords: Amelogenin, LRAP, Solid state NMR (ssNMR), Solution state NMR, Atomic force microscopy (AFM), Hydroxyapatite (HAP), Biomineralization, Enamel, Protein structure

1. Introduction

Driven by millions of years of evolution, living organisms use highly specialized proteins to generate biomaterials with unique physical properties that are often essential for survival (Lowenstam and Weiner, 1989). These biominerals include everything from the shells of mollusks to the bones in vertebrates to the enamel in teeth. While the basic components of biominerals are simple: silicates, carbonates, and calcium phosphates, scientists are often unable to mimic these material properties in purely synthetic systems even though the controlled formation of materials with unique properties such as high aspect ratios, unusual strength, and unusual hardness is desirable in many applications. Proteins are clearly essential in controlling biomineralization in natural systems and protein structure is often related to protein function, however, only recently have methods become available to probe the structure of biomineralization proteins in their functional state, bound to a mineral surface. This is because while the mineral is crystalline, the protein bound to the surface is in a non-crystalline form (Addadi and Weiner, 1985, Lowenstam and Weiner, 1989, Hunter, 1996). Therefore, traditional protein structure techniques, such as protein X-ray crystallography or solution NMR spectroscopy, are not applicable to the problem, and techniques like cryo-transmission electron microscopy (TEM) do not offer enough spatial resolution to provide essential residue specific structural characterization (Fang et al., 2011).

Biomineralization proteins are believed to play important roles in controlling the nucleation and growth of minerals by interacting with ions and growing minerals. Proposed mechanisms to explain how the structure of the adsorbed protein may control nucleation and growth include: 1) a lattice matching mechanism where charged side chains of the protein align with oppositely charged sites on the inorganic surface (Hunter, 1996); 2) a dynamic protein structure at the mineral surface which enables the blocking of multiple crystal sites simultaneously (Shaw et al., 2000a, Long et al., 2001); and 3) a folded protein structure which exposes one part of the protein to the mineral surface and another part to the solution which could enable additional functions (Tarasevich et al., 2013). It addition to the question of mechanism, there is also the question of whether the protein is structured appropriately in solution for its role on the mineral surface, or if protein association with the mineral surface induces the protein to adopt the structure necessary to perform its biomineralization function. It is now possible to start addressing these and other questions regarding biomineralization protein structure and function with recent advancements in solution and solid state NMR spectroscopy and in situ AFM.

Only a handful of protein structures in biomineral systems have been characterized in detail (Shaw et al., 2000a, Shaw et al., 2000b, Gibson et al., 2005, Goobes et al., 2006, Chen et al., 2008, Masica et al., 2011, Lu et al., 2013a, Roehrich and Drobny, 2013, Goobes, 2014, Zane et al., 2014, Matlahov et al., 2015, Shaw, 2015, Iline-Vul et al., 2019) and one of these is amelogenin, the predominant protein associated with enamel formation. Enamel is a carbonated hydroxyapatite (HAP; Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2), has a hardness between iron and carbon steel while also maintaining high elasticity, and is among the strongest biological materials (Simmer and Fincham, 1995). Unlike bone, enamel proteins are nearly completely removed by enzymatic degradation and the resulting enamel lasts a lifetime. These proteins include amelogenin, enamelin, ameloblastin, and amelotin, and of these, amelogenin is the dominant protein present during enamel formation (Simmer and Fincham, 1995, Margolis et al., 2006) and has been demonstrated with knock-out animal models to control the thickness and interweaved pattern of the resulting enamel (Gibson et al., 2001, Hu et al., 2016).

Amelogenin is a 170–180 residue protein depending on species, is highly hydrophobic, and has high homology across species (Fig. 1). It is typically described in three parts: the N-terminal “TRAP” region, the hydrophobic central region rich in histidine, glutamine, and proline, and the mineral binding C-terminus (blue, white, and magenta, respectively, Fig. 1). The N- and C-termini contain all of the 13 charged residues, and for this reason were thought to bind to HAP, and more recent studies using both full length amelogenin and a common splice variant, called Leucine Rich Amelogenin Peptide or LRAP (Fig. 1), have demonstrated that they are oriented next to the surface (Shaw et al., 2004, Masica et al., 2011, Tarasevich et al., 2013). The central portion of amelogenin has also recently been proposed to play a role in interacting with HAP via the histidines when protonated (Gungormus et al., 2012).

Fig. 1.

(A) Primary amino acid sequence of murine, porcine, and human amelogenin. LRAP is a naturally occurring splice-variant of amelogenin present in ameleoblasts and it consists of the N- and C-terminal regions of full length amelogenin (in bold and boxed). Amelogenin and LRAP have been the focus of most studies on the secondary and tertiary structure of amelogenins. The amelogenin primary amino acid sequence is highly conserved across species with the variations usually observed in the length of the hydrophobic region. The pS at position 16 is a phosphoserine observed in native protein. While S16 is phosphorylated in amelogenins isolated from natural sources or in chemically synthesized LRAP, it is NOT phosphorylated in proteins generated recombinantly in Escherichia coli. Arrows indicate the site of two naturally occurring point mutations that have been studied, T21I and P41T. The colored squares above the primary amino acid sequences indicate the position of residue specific isotopic labels introduced for our solid state NMR studies on murine amelogenin: T (blue), K (orange), R (green). The number in parentheses indicates the number of residues in LRAP. (B) Cartoon representation of the three regions present in amelogenin and LRAP: N-terminal Tyrosine-Rich Region (TRAP; blue), Hydrophobic Region (HR; white) and C-terminal Hydrophilic Region (CTHR; magenta).

Structural studies have been slow for several reasons. Under physiological solution conditions at pH 7.4, amelogenin forms nanospheres which consist of a self-assembly of 20–200 monomers (Fincham et al., 1995, Du et al., 2005, Margolis et al., 2006, Chen et al., 2011, Fang et al., 2011). The resulting MDa superstructures hinder the standard use of traditional atomic level structural techniques such as solution state NMR. This is because their isotropic tumbling is too slow, causing the resulting resonances to broaden due to increased transverse relaxation rates, sometimes to the point of not being observable, and can cause severe overlap (Sattler and Fesik, 1996). Because it does not crystallize, x-ray crystallography is also not possible. Amelogenin can also form into beads or nanoribbons (Du et al., 2005, He et al., 2011, Wiedemann-Bidlack et al., 2011, Habelitz, 2015). The nanosphere in solution has been covered extensively and we will not cover it here (Moradian-Oldak et al., 2000, Moradian-Oldak, 2001, Bartlett et al., 2006, Bromley et al., 2011a).

Progress in obtaining high resolution structural data for amelogenin in solution has also been slowed by the intrinsically disordered nature of amelogenin. Intrinsically disordered proteins are a group of proteins with a high degree of conformational plasticity prevalent in eukaryotic organisms. Such proteins often resemble random coils or contain elements of transient secondary structure (Tompa, 2005, Delak et al., 2009, Uversky, 2009, Buchko et al., 2010, Lakshminarayanan et al., 2010, Ndao et al., 2011, Ozenne et al., 2012, Kragelj et al., 2013, Holt et al., 2019) and may only adopt binding-induced folding in the presence of the correct substrate (Wright and Dyson, 2009). The heterogenous conformational space adopted by intrinsically disordered proteins means that they do not crystallize well, eliminating the use of X-ray crystallography. Solution state NMR can be used, however, as a result of the difficulty in studying amelogenin in the nanosphere state, initial structural studies, discussed below, were performed at pH 3 where amelogenin forms monomers or at pH 5–6 where amelogenin forms oligomers (Bromley et al., 2011a). Ultimately, amelogenins functional form is bound to HAP making it necessarily “solid state” in nature. The use of solid state NMR (ssNMR) spectroscopy to study proteins is challenging and significant inroads have been made over the past twenty years (Shaw et al., 2000a, Shaw et al., 2000b, Gibson et al., 2005, Goobes et al., 2006, Chen et al., 2008, Masica et al., 2011, Lu et al., 2013a, Roehrich and Drobny, 2013, Goobes, 2014, Zane et al., 2014, Matlahov et al., 2015, Shaw, 2015, Iline-Vul et al., 2019). At the same time, advances in the sensitivity of AFM imaging techniques coupled with new methods to synthesize larger HAP crystals has made AFM a powerful resource to probe the structure of amelogenin-HAP complexes (Tao et al., 2015).

For all of these reasons, structural studies of amelogenin with atomic precision have only been successful over the past 10–20 years. This review will survey these successes with a focus on recent advances in solution and solid state NMR and in situ AFM that reveal new insights into the secondary, tertiary and quaternary structure of amelogenin by itself and in contact with HAP. These studies have increased our understanding of the interface between amelogenin and HAP and, coupled with in vivo studies, are beginning to elucidate how amelogenin controls enamel formation.

2. Studies of amelogenin in solution

The studies described in this review elucidate various levels of structure. Primary (1°) structure is the linear sequence of amino acid residues starting from the N-terminus, secondary (2°) structure defines individual elements of canonical structure dispersed throught the 1° structure such as α-helices, 310-helices, β-strands, and turns/loops. Tertiary (3°) structure describes how the individual elements of secondary structure fold around each other, and quaternary structure (4°) describes how proteins interact with themselves and/or other proteins and biomolecules in complexes.

2.1. Strategies for structural studies and early insights

Because of the challenges identified in the Introduction, in large part due to the range of large quaternary structures that amelogenin self-assembles into, most of the early studies on amelogenin secondary and tertiary structure utilized techniques that focused on identifying the average secondary structure, such as circular dichroism (CD), Fourier transform infrared (FTIR), and Raman spectroscopy (Renugopalakrishnan et al., 1986, Goto et al., 1993, Lakshminarayanan et al., 2007). CD spectroscopy takes advantage of the optical properties of proteins and is largely confined to studying proteins in solution (Kelly et al., 2005, Greenfield, 2006). FTIR and Raman spectroscopy are vibrational techniques that are extremely sensitive to global conformational changes in protein structure and have the added advantage that they can more readily be used to study proteins adsorbed onto surfaces (Tuma, 2005, Wang et al., 2010, Kim and Cho, 2013). All these methods depend on computer-based deconvolution programs to estimate the quantity of the different elements of secondary structure. The consensus from the CD, FTIR, and Raman data was that over a multitude of solution conditions, amelogenin contained mostly β-strands, β-turns, polyproline II (PPII), and random coil secondary structure (Renugopalakrishnan et al., 1986, Zheng et al., 1987, Renugopalakrishnan et al., 1989, Goto et al., 1993, Renugopalakrishnan, 2002). Included in these early efforts was an approach to overcome some of the challenges of investigating the full length structure of amelogenin by studying protein fragments. Aoba and coworkers found that the CD spectrum of full length porcine amelogenin was equivalent to the sum of the three separate sections, which in this case were defined as the N-terminal TRAP region (residues 1–45), the central hydrophobic region (residues 46–148), and the C-terminal region (residues 149–173) (Goto et al., 1993). While the intrinsically disordered nature of amelogenin had not yet been established, and removing even one amino acid may significantly destabilize secondary and tertiary structure of a protein, the lack of change of secondary structure when significant portions of the protein were removed was surprising. As will be demonstrated later, this ability to “slice and dice” amelogenin is a trait observed in the intrinsically disordered human high mobility group-A protein (Buchko et al., 2007) and a feature seen when fragments of amelogenin were studied (Buchko et al., 2010, Buchko et al., 2018).

While CD, FTIR, and Raman spectroscopy provide information on protein secondary structure, global tertiary and quaternary structure can be probed with techniques such as dynamic light scattering (DLS) (Stetefeld et al., 2016), small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS), (Kikhney and Svergun, 2015) and more recently, sedimentation velocity analytical ultracentrifugation (SV) (Lebowitz et al., 2002). DLS provides an indirect measure of particle size and distribution, providing a measure of mean particle size reported as a hydrodynamic radii (RH). SAXS is a technique that complements DLS with the advantage that it is sensitive to electron density differences and can better survey the shape of complexes. By the determination of sedimentation coefficients, SV provides detailed information of the molecular weight of species in solution but is restricted to studying protein solutions that are at a concentration of less than 2 mg/mL. An early SAXS study under acidic conditions (2% acetic acid) showed that amelogenin adopted an asymmetric elongated shape of 150 × 20 Å that was interpreted as a dimer (Matsushima et al., 1998). Based on later work, this interpretation is likely incorrect as it has since been shown that amelogenin is largely monomeric at 10 mg/mL (~0.4 mM) in 2% acetic acid (Buchko et al., 2008a, Delak et al., 2009). Molecular modeling of the SAXS data in combination with previous FTIR and CD data led them to conclude that the secondary structure of amelogenin contained PPII and/or β-strands, both interspersed with β-turns/loops (Matsushima et al., 1998), an interpretation that is consistent with more recent, detailed NMR studies discussed in detail below.

A limitation of the above techniques is that they provide average structures over the entire protein, providing little insight into the location of specific secondary structure elements in the primary amino acid sequence. This is due to the sensitivity of the chemical shift of NMR active nuclei, 1H, 13C, and 15N, to their local environment which vary between structural states. Consequently, NMR spectroscopy is the tool of choice for studying the secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures of proteins up to ~50 kDa in molecular weight that do not crystallize (Frueh et al., 2013). This size limitation has created a challenge in studying self-assembled amelogenin which has a size in the MDa range at physiological pH, limiting most studies to the monomer (~22 kDa) at pH 3 and the assembly of dimers (~44 kDa).

The earliest NMR structural experiment with amelogenin was the creative study by Aoba et al., using solution state NMR with photo-Chemically Induced Polarization Transfer (CIDNP), a technique which allows the identification of residues exposed on the surface of porcine amelogenin and its degradation products, specifically Trp, His, Tyr, and Phe residues (Aoba et al., 1990). This study, performed at a concentration of 5 mg/mL (~2 mM) at pH 5.2 (likely oligomers), demonstrated that in full length amelogenin the C-terminal Trp was more exposed than the two N-terminal Trp residues and some of the six Tyr residues in the N-terminal TRAP region were also solvent exposed in full length amelogenin, consistent with the proposal that both the N- and C-termini are more solvent exposed then the central region of the protein and better able to interact with HAP and/or other biomolecules. Studies of the His residues of various natural cleavage products differed from the full length protein indicating that the tertiary or quaternary structure was affected by truncation. The degradation products showed differences in side chain exposure of these residues, indicating changes in the tertiary or quaternary structure as different protein regions are removed, in contrast to the relative stability of the secondary structure observed in amelogenin fragments by CD discussed above (Goto et al., 1993). This structural study was supported by a later enzymatic degradation study by Moradian-Oldak and coworkers which showed that both the N- and C-termini are exposed on the surface of amelogenin oligomers, with perhaps somewhat hindered access to the N-terminus due to protein-protein interactions (Moradian-Oldak, 2001).

2.2. The NMR epoch – the first chemical shift assignments for amelogenin

The influx of solution state NMR data on amelogenin began in 2008 with the successful collection of an 1H-15N heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) spectrum by Buchko et al., with resolved amide cross peaks obtained at low pH (~2.8) in salt-free 2% acetic acid solution where amelogenin is a monomer (Buchko et al., 2008a). The 1H-15N HSQC spectrum provides a diagnostic fingerprint for a protein—a broad dispersion of uniformly sized amide resonances in both 1H and 15N dimensions is characteristic of a folded protein (Yee et al., 2002). The lack of dispersion of the resonances for amelogenin shown in Fig. 2, as compared to a folded protein, in this case reduced Xanthomonas campestris peroxiredoxin Q (PrxQ) (Buchko et al., 2016), is characteristic of a lack of structure. The technology advance that assisted this turning point in the solution state studies of amelogenin was the acquisition of data on one of the first available magnets that operated at a proton resonance frequency of 900 MHz.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the 1H-15N HSQC spectrum for a (left) folded protein, Xanthomonas campestris peroxiredoxin Q (PrxQ) and (right) murine amelogenin. Note the broad distribution of resonances in the 1H chemical shift dimension (horizontal) for the folded protein, while the distribution of resonances for amelogenin is much narrower, consistent with an unfolded protein. Data taken from Buchko, et al. Biochem. NMR Assign, 2016 and Buchko, et al., Biochem. NMR Assign., 2008, respectively.

Using a suite of two- and three-dimensional NMR backbone assignment experiments with 15N- and 13C-labeled samples along with residue specific 15N-labeled samples it was possible to assign 143 of the expected 146 amide cross peaks in the 1H-15N HSQC of murine amelogenin (Table 1; Fig. 2) (Buchko et al., 2008a). The lack of dispersion of the amide cross peaks in the proton dimension (~1 ppm) in the 1H-15N HSQC spectrum for amelogenin, Fig. 2, suggested the protein was largely unstructured (Yee et al., 2002). This was corroborated by the analysis of the assigned 13Cα and 13Cβ side chain atoms which are sensitive to their secondary structure environment as illustrated in Fig. 3 (Wuthrich, 1986, Wishart and Sykes, 1994, Wishart and Sykes, 1994, Wishart et al., 1995a, Wishart et al., 1995b). While these carbon chemical shifts did not vary much from random coil values, there was a slight overall propensity toward β-strand structure based on the generally positive Δδ13Cα and negative Δδ 13Cβ changes (Buchko et al., 2008a). These observations were consistent with the now current classification of amelogenin as an intrinsically disordered protein (Delak et al., 2009, Uversky, 2009, Buchko et al., 2010 Lakshminarayanan et al., 2010, Ndao et al., 2011, Ozenne et al., 2012, Kragelj et al., 2013, Holt et al., 2019), and consistent with multiple earlier optical structural studies (Renugopalakrishnan et al., 1986, Goto et al., 1993, Lakshminarayanan et al., 2007) suggesting amelogenin was largely a random coil structure with the presence of varying degrees of β-strand and turn elements (Renugopalakrishnan et al., 1986, Zheng et al., 1987, Goto et al., 1993).

Table 1.

Solution conditions of the major solution state NMR studies conducted on amelogenin since the first assignment was reported in 2008. In the protein recombinantly expressed by E. coli, the N-terminal methionine is absent, and the side chain of S16 is not phosphorylated. Full length murine (M) and porcine (P) amelogenin correspond to M179 and P173, respectively.

| Protein | N-terminal tag | pH | Temp | Solution conditions | Protein concentration | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M179 | MRGSHHHHHHGS- | 3.0 | 25 °C | 2% acetic acid | ~40 mg/mL (~2 mM) | Buchko et al., Biomol. NMR Assign, 2008 |

| M179 | MRGSHHHHHHGS- | 3.0 | 20 °C | 2% acetic acid/300 mM NaCl or 2% acetic acid/165 mM CaCl2 | ~20–28 mg/mL (~1–1.4 mM) | Buchko et al., Biochemistry, 2008 |

| P173 | none | 3.8 | 10 °C | water only | 1.5 mg/mL (0.075 mM) | Delak et al., Biochemistry, 2009 |

| murine LRAP | MRGSHHHHHHGS- | 3.0 | 20 °C | 2% acetic acid and up to 440 mM NaCl | 2.7–4.8 mg/mL 0.3–0.6 mM | Buchko et al., Biochem Biophys Acta, 2010 |

| M179 | MRGSHHHHHHGAGDRGPE- | 5.5 | 25 °C | 0.02% acetic acid and 5 mM NaH2PO4 | ~ 10 mg/mL (~0.4–0.7 mM) | Zhang et al., PlosOne, 2011 |

| M(1–92) | MRGSHHHHHHGAGDRGPE- | 5.5 | ||||

| M(34–154) | MRGSHHHHHHGAGDRGPE- | 5.5 & 7.0 | ||||

| M(86–180) | MRGSHHHHHHGAGDRGPE- | 5.5 and 7.0 | ||||

| P173 | none none |

3.8 3.8 |

10 °C | water only 70% TFE |

1.5 mg/mL (0.075 mM) | Ndao et al., Protein Science, 2011 |

| M179 | MRGSHHHHHHGS- | 8.0 | 37 to −35 °C | 20 mM Tris | 300 mg/mL (15 mM) | Lu et al., J. Dent Res, 2013 |

| M179-(P41T) | MRGSHHHHHHGS- | 3.0 | 20 °C | 2% acetic acid Up to 400 mM NaCl | 2–36 mg/mL (0.1–1.8 mM) | Buchko et al., Arch. Biochem. Bipohys, 2013 |

| M179-(T21I) | MRGSHHHHHHGS- | |||||

| P173 | none | 3.8 | 20 °C | 50 mM SDS micelles 100 mM SDS micelles | 1.5 mg/mL (0.075 mM) | Chandrababu, et al., Biopolymers, 2014 |

| M179-(P71T) | none | 2.8 | 20 °C | 2% acetic acid and up to 367 mM NaCl | 2–36 mg/mL (0.1–1.8 mM) | Buchko et al., Protein Expr. Purif., 2015 |

| murine LRAP | MRGSHHHHHHGS- | 2.8 & 7.4 | 20 °C | 2% acetic acid and 0.15 M NaCl in SCP | 2 mg/mL (0.1 mM) | Tarasevich et al., J Struct Biol, 2015 |

| murine TRAP | GPGS- | 2.8 | 20 °C | 2% acetic acid | ~4 mg/mL (~0.2 mM) | Buchko et al., Arch Oral Biol, 2018 |

Fig. 3.

Protein NMR chemical shifts are highly sensitive to structure. Random coil structures have resonances with very little chemical shift dispersity and are always centered between helical structures and β-sheet structures. Carbonyl carbons and Cα carbons shift to the left, or downfield, from the average random coil structure for a helical structure, and upfield, or to the right, for a β-sheet structure. The Cβ carbons shift opposite.

Two structural studies with solution NMR followed the NMR assignments and provided additional insight. Both studies were reported under low pH conditions which favor a monomer structure. To capture the residual structure of porcine amelogenin, Moradian-Oldak, Evans, and coworkers collected NMR data under conditions that reduced interactions with itself or other molecules, using dilute amelogenin solution (1.5 mg/mL, 0.075 mM) at pH 3.8 (Delak et al., 2009). These NMR experiments were assisted by a major technology advance in NMR probe technology, the cryoprobe Kovacs et al., 2005). By cooling NMR probes down to liquid helium temperatures the signal-to-noise ratio is increased by about four-fold, making it possible to acquire NMR data on dilute samples. As illustrated for a representative structure for this ensemble in Fig. 4, amelogenin was found to be extended, stretching out almost 200 Å from the N- to C-terminal, and devoid of any global or tertiary structure. This led to the classification of amelogenin as an intrinsically disordered category of proteins (Delak et al., 2009).

Fig. 4.

Normalized summary of the identified residual elements of secondary structure reported in amelogenin as deduced from various available NMR data collected under a range of conditions. All of the data is from solution NMR data except the ssNMR data at pH 8.0. From the top: A representative cartoon structure of a single porcine amelogenin monomer based on the pH 3.8 data with matching color scheme; murine amelogenin nanospheres (pH 8.0); murine amelogenin that are likely oligomers (pH 5.5); porcine amelogenin monomers (pH 3.8 in dilute water); porcine amelogenin oligomers with 70% TFE. Coloring scheme: extended β-strand = dark cyan, α-helix = red, 310-helix = pink, random coil = white, β-turn/loop = yellow, polyproline II = orange, unassigned = light cyan. On the bottom is a linear cartoon representation of the three regions present in amelogenin: N-terminal Tyrosine-Rich Region (TRAP; blue), Hydrophobic Region (HR; white) and C-terminal Hydrophilic Region (CTHR; magenta). Partially reproduced with permission from Delak et al, Biochemistry, 2009 and Ndao et al, Protein Science, 2011.

A structure for murine amelogenin based on NMR data was also reported by Zhang et al. (2011). Unlike the structure reported by Delak et al. under conditions designed to maximize the monomeric state of amelogenin to isolate transient structure (Delak et al., 2009), Zhang et al. collected their NMR data at pH 5.5 in a low salt environment (5 mM NaH2PO4 and 0.02% acetic acid) at a concentration of 10 mg/mL (~0.4 mM) and collected data on four different segments of amelogenin: the full length and three fragments, (Amel-N (1–92), Amel-M (34–154) and Amel-C (86–180) (Zhang et al., 2011). The NMR-based structures in these studies also showed an extended structure with some regions of residual structure, as summarized in Fig. 4. The largest differences between the pH 3.8 and 5.5 structures were increased random coil and α-helical structural elements at the expense of PPII and extended β-strand structural elements upon increasing pH. Of interest was the observation of long-range NOEs which were proposed to be due to intramolecular helix-helix interactions. Given the solution conditions for the NMR studies, amelogenin may have been self-associated under these experimental conditions (Bromley et al., 2011a) and these long-range NOEs might be due to intermolecular interactions near the N-terminus. If so, they would represent the first NOE data to confirm the model of amelogenin self-association through interactions in this region.

2.3. Solution structure under conditions mimicking physiological features

In the complex environment of the enamel matrix, amelogenin interacts with other proteins, membrane surfaces, and minerals to effect enamel formation. In an effort to tease out and map the structural features responsible for these multiple intermolecular interactions, Moradian-Oldak and colleagues used 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol (TFE) (Ndao et al., 2011) and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) micelles (Chandrababu et al., 2014) as proxies for other proteins and cell membranes, respectively. The fluorinated alcohol TFE is a helix stabilizing agent commonly used to expose folding predispositions of peptides and proteins (Sonnichsen et al., 1992, Buck, 1998, Buchko et al., 2013a) and micelles formed by the detergent SDS are commonly used to mimic cell membrane (Henry and Sykes, 1994) and lipoprotein (Rozek et al., 1995) environments. Both additives resulted in a clear increase in helical structure by CD spectroscopy (Fig. 5) based on the appearance of an ellipticity double minimum at 208 and 222 nm and a maximum at 195 nm in the CD profile (Holzwarth and Doty, 1965, Ndao et al., 2011, Chandrababu et al., 2014). However, NMR data collected under similar conditions do not show significant changes, suggesting that the increase in helical content observed by the CD data was transient in nature (Ndao et al., 2011, Chandrababu et al., 2014). Fig. 5 summarizes the structural changes. These observations confirm that the termini are “conformationally responsive”, perhaps enabling them to interact and function with other components in the enamel matrix (Ndao et al., 2011, Chandrababu et al., 2014).

Fig. 5.

Addition of TFE to porcine amelogenin results in the formation of some helical content, indicated by the double minima in the CD spectra at 208 and 222 nm. Reproduced with permission from Ndao et al., Protein Science, 2011.

While solution NMR is valuable in providing sequence specific structural insights for 22 kDa amelogenin in the monomeric state, upon self-assembly into even a 44 kDa dimer the acquisition and interpretation of NMR data becomes difficult due to the slower isotropic tumbling that results in line-broadening (Sattler and Fesik, 1996, Frueh et al., 2013). Therefore, to obtain structural insights, particularly at more physiologically relevant pH’s where oligomers and nanospheres form, it is necessary to use other “size-friendly” methods.

Solid state NMR (ssNMR) spectroscopy was used to study amelogenin at pH 8 in a nanosphere gel form (Lu et al., 2013a). Studies under these physiological conditions were possible due to the inherent technology that enables high resolution spectra with ssNMR. A technique called magic angle spinning (Schaefer and Stejskal, 1976, Alemany et al., 1983a) is used to mechanically simulate isotropic tumbling, removing these interactions in ssNMR, something that is needed to obtain high resolution on many solid state samples. This now common methodology allows the protein to be studied under conditions very close to physiological. This study revealed the secondary structure of fully 13C and 15N labeled recombinant tagged murine amelogenin at pH 8, 20 mM Tris and ~300 mg/mL (15 mM), in a nanosphere gel (in the absence of HAP), to be highly mobile and largely unstructured, even when frozen. To provide more specific structural information, amelogenin with 13C-, and 15N-labeled Lys was prepared and ssNMR data collected under the same conditions used for the fully labelled sample. The Lys residues are present near both termini (K24, K173, K175, Figs. 1 and 4) enabling us to probe the structure of amelogenin via the chemical shift analyses of the Lys 13CO, 13Cα, and 13Cβ resonances (Fig. 3). Such an analysis indicated that all the Lys residues were highly mobile and largely unstructured. However, a small percentage of the protein (~10%) existed in a β-sheet structure and the Lys residues that were β-sheet were less mobile than the ones in the random coil structure. Importantly, these studies suggest that the protein exists in two conformations: one which is mobile and unstructured and the other which is less mobile and β-sheet structured under the nanosphere condition. It is possible that these two structures are in equilibrium with each other and that the detected β-sheet structure is waiting to interact with HAP. While this ssNMR experiment only sampled the three Lys residues in amelogenin, they are in regions believed to play roles in protein-protein interactions and protein-HAP interactions during enamel formation.

Fig. 4 compares the residual structure observed in the nanosphere and in amelogenin oligomers and monomers (Delak et al., 2009, Ndao et al., 2011, Zhang et al., 2011, Lu et al., 2013a). It is interesting to note that the residual structure in the nanosphere, while only sampling three amelogenin esidues, is different than that observed in the monomers or oligomers at lower pH values, accenting the sensitive nature of amelogenin’s structure to environmental conditions.

Another set of experiments comparing structure under physiological and non-physiological conditions involved an FTIR study by Beniash et al. on full length porcine recombinant amelogenin at pH 3.0, 5.6, 7.2, and 8.0 with a summary of the deconvoluted spectra shown in Fig. 6 (Beniash et al., 2012). The most significant structural change at pH 3.0 (monomers) compared pH 5.6 (oligomers) was a decrease in the random coil character with a concomitant increase in intramolecular β-sheet and hydrated PPII structure, suggesting an increase in folded structure that contrasts the absence of increased folding as detected by CD (Bromley et al., 2011a). More significant changes were observed from pH 5.6 (oligomers) to pH 7.2 and 8.0 (nanospheres) where the total β-strand structure (aggregated β-strands plus intramolecular β-strands) increased, an increase consistent with CD observations (Bromley et al., 2011a). The most prominent feature in Fig. 6 is the large amount of PPII structure identified by FTIR at pH 5.6 (oligomers), structure that has been seen in amelogenin under various solution conditions and reported using several methods (Goto et al., 1993, Matsushima et al., 1998, Lakshminarayanan et al., 2007, Delak et al., 2009, Zhang et al., 2011).

Fig. 6.

FTIR data showing changes in secondary structure of recombinant porcine amelogenin as a function of pH or surface. Note in particular the difference in structure between protein bound to a pre-formed HAP surface compared to that when protein is present with HAP forming in situ. Data modified from Beniash et al. J. Dent. Res. 2012.

A series of CD studies also provided additional insight into global secondary structure within the oligomer structure. Through a series of CD thermal melting experiments designed to follow PPII structure, along with a combination of DLS and fluorescence experiments, Lakshminarayanan et al. were able to follow global protein folding as a function of temperature (Lakshminarayanan et al., 2010). Using recombinant murine amelogenin at 0.4 mg/mL (0.02 mM), 25 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.8 (oligomers), they observed that amelogenin transformed into a stable, partially folded conformation upon heating up to 45 °C and then unfolded at higher temperatures (Lakshminarayanan et al., 2010). This was accompanied by a nearly complete overlap of the ellipticity at 224 nm upon cooling, consistent with an intrinsically disordered protein lacking any hysteresis effects as a function of temperature (Uversky, 2009). The CD and fluorescence data at 25 °C suggest it is a more compact structure than a fully extended protein.

2.4. The residue specific self-assembly properties of amelogenin

Since amelogenin self-assembles into oligomers that in turn self-assemble into nanospheres, a number of studies of amelogenin in solution provide insight into the protein regions stabilizing early protein-protein interactions. The first of these studies by Buchko, et al. involved the collection of 1H-15N HSQC spectra, starting in 2% acetic acid (pH ~2.8), as a function of increasing NaCl and CaCl2 concentration. In both cases, as the concentration of the salt increased, amide cross peaks began to broaden and their intensity decreased until they could no long be observed (Buchko et al., 2008a). The line broadening suggested an increase in molecular weight (Reid, 1997), consistent with the formation of dimers and corroborated by larger overall rotational correlations times (τc) (Krishnan and Cosman, 1998) and DLS at higher salt concentrations. Mapping the resonances showed that self-association of murine amelogenin began at a region near the N-terminus (L12 – I51) followed by a region near the C-terminus (L141–T171) as the salt concentration was increased. No interactions in the central part of the protein were observed under these conditions (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

A solution state NMR study demonstrated the initial interaction regions for amelogenin self-assembly induced by salt were in the N-terminus, followed later by interactions near the C-terminus. Of interest is that studies done with TFE also demonstrated N-terminal interactions but not C-terminal, suggesting different modes of interactions with different function. Reproduced with permission from Buchko et al., Biochemistry, 2008.

The ability of amelogenin to self-associate had previously been reported to be triggered by changes in pH (Moradian-Oldak et al., 1994, Moradian-Oldak et al., 1998, Wiedemann-Bidlack et al., 2007), and was fully described by Moradian-Oldak and colleagues who showed with DLS and fluorescence experiments a gradual transition from the monomeric state at pH 3 to oligomers of increasing size that maxed out at approximately octamers at a pH of around 6, prior to self-assembling into nanospheres (Fig. 3) (Bromley et al., 2011a). It should be noted that throughout this pH driven self-assembly process from monomers (pH 3) to oligomers (pH 6.5), CD spectroscopy studies detected no increase in folding (Bromley et al., 2011b) while during the transition from octamers to nanospheres a slightly greater increase in the magnitude of β-strand character was reported.

Using dynamic light scattering to measure the diameter of species, Bromley et al. also illustrated that the oligomerization state of amelogenin depended on the protein’s concentration at pH 5.6 (Bromley et al., 2011a). To track the regions/residues of amelogenin responsible for self-association, a series of 1H-15N HSQC spectra were collected for amelogenin as a function of protein concentration at pH 2.8 (2% acetic acid) from 2 to 36 mg/mL (~0.1 to 1.8 mM) (Buchko et al., 2008b). Unlike the earlier experiments where amide cross peaks disappeared upon self-association in the presence of increasing concentrations of salt, in the presence of increasing protein concentrations, the amide line widths increased but did not disappear, and small chemical shift perturbations were observed (Buchko et al., 2013b). Both of these observations are features of concentration induced self-association, and in this case suggest that the association may only be transient in nature. Small perturbations were all clustered towards the N-terminus between Y12 – I30, a region associated with the first region of salt-induced self-association of murine amelogenin (L12 – I51) (Buchko et al., 2008b). Of note based on the concentration studies is that the concentration used to make the original chemical shift assignments for murine amelogenin (~40 mg/ml, 2 mM), (Buchko et al., 2008a) amelogenin likely was not completely monomeric and some transient self-association was present.

In a similar vein, Zhang et al. used a combination of SV and NMR experiments to study the self-assembly properties of full length murine amelogenin and three regions (Amel-N (1–92), Amel-M (34–154) and Amel-C (86–180) at pH 5.5 (oligomers) and pH 7.0 (nanospheres) (Zhang et al., 2011). The Diekwisch NMR study also reported the observation that N-termini interact with N-termini and C-termini interact with C-termini when forming oligomers at pH 5.5, based on the disappearance of resonances from these regions (Zhang et al., 2011). At pH 7.0 they found that only the N-terminal fragment showed signs of self-assembly and that the C-terminal fragment did not interact with the N-terminal fragment. Together, the findings from the salt and protein concentration chemical shift perturbation experiments (Buchko et al., 2008b, Buchko et al., 2013a) and those from Zhang et al (Zhang et al., 2011) support the model of primarily N-terminally mediated initial oligomer formation, with the C-terminus contributing later in the process.

It was also concluded that oligomerization in the presence of 70% TFE was also confined to the N-terminal region, though no evidence for C-terminal interactions were observed in the presence of TFE, (Ndao et al., 2011) possibly due to the presence of salt, the different pH values, or the ~ 10-fold difference in protein concentrations used in both the Buchko and Diekwisch studies (Buchko et al., 2008b, Zhang et al., 2011). Such differences in self-association further highlight the sensitive nature of the structure to environmental conditions, both ex situ, and likely, also in vivo.

Further evidence for the importance of C-terminal interactions are supported by a cryo-TEM study, suggesting they are critical for the formation of oligomers, the proposed foundation of the nanospheres (Fang et al., 2011). Beniash and coworkers studied recombinant untagged murine proteins, including full length and M166, the protein representing the first naturally occurring cleavage product which is missing the C-terminal 13 residues, and consequently, the majority of the charged residues. The samples were prepared in 4 mM PBS at pH 8.0 and 20–50 uL aliquots sat on a TEM grid for times ranging from 1 to 30 min prior to plunge freezing and transferring to the microscope. Amelogenin monomers were observed at short time periods and were ellipsoid in shape with the C-terminus protruding from the ellipsoid. At later times, oligomers were observed consisting of a hollow dodecamer ring. The dodecamer was formed by the assembly of dimers that were stabilized by interactions between the C-termini. This resulted in the C-termini positioned on the outside and at the equator of the ring (Fig. 8). Similar results were seen for recombinant porcine amelogenin, as well as for isolated and purified phosphorylated porcine amelogenin studied under identical solution conditions (Fang et al., 2013).

Fig. 8.

A cryo-TEM study showing how recombinant murine amelogenin (both full length (A) and M166 (B)) assembles when frozen from a 4 mM PBS solution, revealing a dodecamer ring structure (C) made by the assembly of six dimers stabilized by C-terminal anti-parallel interactions. Reproduced with permission from Fang et al., PNAS, 2011.

The C-termini in this case are associated in an anti-parallel fashion, an orientation that is consistent with later ssNMR studies and MD calculations to be discussed in greater detail below. In contrast, the solution state NMR studies we have just described (Buchko et al., 2008b, Delak et al., 2009, Zhang et al., 2011) suggest amelogenin self-assembly begins with parallel alignment of monomers. The solution state NMR studies of amelogenin were performed at low pH values, pH 3 and pH 5.5, in contrast to the pH 8 condition used for the cryo-TEM studies. At pH 3, amelogenin is a monomer that has an extended rod-like tertiary structure based on the SAXS and NMR studies (Matsushima et al., 1998, Buchko et al., 2008b, Delak et al., 2009, Zhang et al., 2011). In contrast, the monomers imaged by cryo-TEM at pH 8 have a much more collapsed tertiary structure, appearing to be an ellipsoid with a protrusion by the C-terminus. Interestingly, the NMR and cryo-TEM studies of the aggregation of monomers suggest that the interactions of the C-terminus depend on the tertiary structure of the protein monomer. The step-wise assembly process that has been demonstrated in in vitro studies going from a low pH to a high pH (Bromley et al., 2011a) suggest that there is an entropically and energetically favorable way to undergo this transition. At low pH the initial dimer interaction between extended monomers is parallel, i.e. N-terminal to N-terminal and C-terminal to C-terminal as suggested by solution state NMR studies. As the pH increases, the monomer collapses into an ellipsoid shape and the C-termini interact in an antiparallel conformation in order to maximize the interactions between the C-termini and minimized steric hindrance between the ellipsoids. More studies of these interactions are needed under similar conditions to fully inform our understanding of the protein–-protein interactions as a function of the changing conditions during enamel formation.

2.5. The splice variant, LRAP

The most common splice variant present during amelogenesis is a ~60 residue protein, LRAP, containing the complete N- and C-terminal regions of the full length protein (Fig. 1). Because LRAP contains both amelogenin termini associated with functional properties, it has often been used as a surrogate for full length amelogenin. Using 15N-labelled amelogenin to start, it was observed that there was little change in the fingerprint 1H-15N HSQC spectrum for LRAP. (Le et al., 2006) (Buchko et al., 2010) Different from the 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of the full length protein was the presence of an additional set of amide cross peaks for the seven non-proline residues at the N-terminus suggesting two unique, slowly interconverting conformations for the N-terminal region of the protein (Buchko et al., 2010). A further difference from full length amelogenin was that self-association (4.8 mg/mL, 0.6 mM) as a function of NaCl concentration began in the middle of the protein, followed by contributions towards the N- and C-termini at overall 4-fold lower salt concentration. It was proposed that the different self-assembly properties between LRAP and full length amelogenin may reflect different biological functions for the two proteins (Buchko et al., 2010).

Margolis and coworkers conducted SAXS studies on chemically synthesized porcine LRAP with and without S16 phosphorylation at pH 7.4 and ~5 mg/mL (0.8 mM) (Le Norcy et al., 2011a, Le Norcy et al., 2011b) to obtain an estimation of the overall size and shape for LRAP. Calcium was added up to a Ca:LRAP ratio of 8:1. Non-phosphorylated LRAP appeared to have some level of folding in the absence of calcium based on the shape of the resulting curve, a curve which did not change upon the addition of calcium. These results suggest that the addition of calcium did not change the overall structure and are consistent with an earlier CD study (Le et al., 2006). On the other hand, the SAXS signal for phosphorylated LRAP changed significantly as a function of increasing calcium as illustrated in Fig. 9. Based on the shapes of the SAXS scattering curves, the data was interpreted to indicate a change from an extended unfolded structure in the absence of Ca2+ to a more globular structure with bound Ca2+.

Fig. 9.

Small angle X-ray scattering studies of porcine LRAP show that the overall shape of the phosphorylated LRAP changes significantly upon addition of Ca2+(left), while the unphosphorylated variant does not (right). This was interpreted to represent a global structural change in phosphorylated LRAP due to Ca2+ binding and could represent an important functional role for S16 phosphorylation. Reproduced with permission from Le Norcy et al., EJOS, 2011.

Tarasevich and coworkers used small angle neutron scattering (SANS), SV, and solution state NMR to study the secondary and tertiary structure of synthetic phosphorylated LRAP (≤2 mg/mL, 0.1 mM) under a variety of salt concentrations (50–150 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2) and pH conditions (3.0 to 7.4) (Tarasevich et al., 2015). They found for the first time that LRAP is a monomer under all conditions studied and does not self-associate except for aggregates formed at the isoelectric point at pH 4.2. The SV studies showed that the monomer has an asymmetric tertiary structure that is slightly more collapsed with increasing pH and more collapsed in the presence of NaCl and CaCl2. The more collapsed structure in the presence of calcium is consistent with the LeNorcy study (Le Norcy et al., 2011a, Le Norcy et al., 2011b). While Rosetta, a Monte Carlo computational technique, predicted helical structure, solution state NMR studies of unphosphorylated LRAP at pH 7.4 suggested that the helices were transient in nature as little canonical structure was observed upon analysis of the carbon chemical shifts. Further, both CD (phosphorylated LRAP) and NMR (unphosphorylated LRAP) spectroscopy studies showed no change in secondary structure upon the addition of calcium, consistent with previous CD studies, (Le et al., 2006) suggesting that changes observed by Margolis (Le Norcy et al., 2011a, Le Norcy et al., 2011b) were not due to secondary structural changes.

Collectively, these structural studies on amelogenin in solution, using an army of methods to probe secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structure, are consistent with an unstructured protein under all conditions – monomers, oligomers, and nanospheres. What appears to change subtly over the course of the different self-associated states and solution conditions is the population and general location of the transient structure. The highly dynamic nature may allow amelogenin to adopt different roles throughout its residence time during amelogenesis including the interaction with solid mineral surfaces such as HAP, the subject of the second half of this review.

3. Structure of amelogenin adsorbed on surfaces

Ultimately, the structure of any given biomineralization protein is of most interest bound to its relevant surface, which would represent its functional form. Directly studying amelogenin on the surface is challenging both because of the large size of the protein, the difficulty to crystallize the protein, which would allow X-ray crystallography to be used, the highly repetitive nature of the primary sequence, and the small size of typical HAP crystals. Ideally, the secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structure, the protein orientation, and the dynamic nature of the protein bound to surfaces would be determined. Because of the nature of the protein adsorbed sample, solid state techniques need to be used. The lack of opacity of HAP creates challenges with optical techniques like CD spectroscopy, although ATR-FTIR can still provide important average structures, as discussed below.

Early work in this area was done using ssNMR. For instance, a ssNMR study in 1980 reported the extraction of all the enamel proteins from fetal calf (along with mineral (60%) and water (25%)) (Termine and Torchia, 1980). Ninety percent of the protein present was determined to be amelogenins (Margolis et al., 2006). The resulting studies were largely able to characterize the motion of the protein using proton decoupling, a technique which removes interactions of protons with protons and other nuclei, and cross polarization, a technique which allows the magnetization from one nucleus be transferred to another nucleus. Cross polarization allows signal enhancement and combined with in depth analysis, provides insight into the mobility of the species being studied. These studies showed that 70% of the protein is highly mobile, with correlation times faster than 10−6 sec and isotropic motion, i.e. movement in all directions. The other 30% of the sample was motionally restricted, meaning that it did not adhere to one of the above two conditions. A surface immobilized protein is generally expected to have less motional freedom than one not restricted by a surface, so this study suggested several possibilities—either a significant part of the protein was not immobilized, or of the protein immobilized, only a small portion of it is strongly bound to the surface. Later studies, discussed below, provide additional insight into these early observations.

Ultimately residue and molecular specificity in these three areas (structure, orientation, and dynamics) is desired, and ssNMR emerged as a technique of choice for studying biomolecules bound to surfaces. This technique experienced large advancements in the 1990s allowing narrow enough lines and advanced pulse sequences to enable site specific distance determinations to allow the characterization of secondary and tertiary structure (Alemany et al., 1983a, Alemany et al., 1983b, Alemany et al., 1983c, Gullion and Schaefer, 1989, Pan et al., 1990, Bennett et al., 1995, Gregory et al., 1995, Gullion, 1998, Schaefer, 1999). Further developments beginning in the 2000s in both sample preparation, pulse sequence development, and line shape led to the applicability of techniques that had commonly only been relevant for solution state NMR of biological molecules (Tycko, 2001, Igumenova et al., 2004, Zech et al., 2005, Zhou et al., 2012, Hong and Schmidt-Rohr, 2013, Tang et al., 2013, Mandala et al., 2017). These techniques opened up a much bigger scope of structural characterization for immobilized biomineralization proteins. While some of this has been reviewed previously, (Shaw, 2015) the amelogenin relevant work is summarized again here briefly for completeness.

3.1. LRAP bound to HAP

While LRAP is an interesting protein to investigate in its own right, initial investigations of amelogenin using ssNMR required a smaller protein than full length amelogenin. This was driven by a technological limitation of NMR spectroscopy at that time: structures of large, immobilized proteins that would use fully isotopically labeled proteins had not yet been achieved. Instead, structural determination was enabled by inserting isolated isotopic labels (Fig. 10). The requirement for the specific location of isotopically labeled residues necessitated preparing the protein using a peptide synthesizer. While powerful, this synthetic approach at the time limited the length ~60 residues (Shaw, 2015). Early ssNMR spectroscopy structural studies utilized the introduction of single isotopic labels to measure specific distances, either within the protein or from the protein to the HAP surface. Because LRAP consists of the N- and C-terminal regions of full length amelogenin, and further, those are the regions thought to interact with HAP, it was used as a model for amelogenin to start to provide residue specific detail of the structure of an amelogenin protein bound to HAP.

Fig. 10.

Protein structure and orientation can be determined using ssNMR by introducing single isotopic labels into the protein (yellow and magenta) and taking advantage of the NMR active 31P in HAP (blue explosions). Dynamics can also be studied for any of the labeled residues.

The structure through most regions of LRAP has been evaluated by Shaw and coworkers using a pulse sequence called rotational echo double resonance (REDOR), which measures the distance between the 13C and 15N atoms in the i and i + 4 residues (Fig. 10 and Fig. 11) (Shaw et al., 2004, Shaw and Ferris, 2008, Shaw and Ferris, 2008, Masica et al., 2011, Lu et al., 2013a, Lu et al., 2014). Residues at these positions are involved in the hydrogen bond stabilizing an α-helical structure and are 4.2 Å apart in a perfect helix. Because the natural abundance of these stable isotopes is <1% for 13C and <0.1% for 15N, the specific isotopes introduced are the only atoms observed in the ssNMR experiments. Additionally, if the structure is random coil or β-sheet, the i to i + 4 distances are 5.8 Å and 10.2 Å respectively, distances easily discriminated between using REDOR (Shaw, 2015).

Fig. 11.

Summary of the LRAP regions labeled to determine the structure, orientation, and mobility of the protein bound to HAP.

Using this technique, Shaw and coworkers explored a number of features, including the importance of the phosphoserine at position 16, the effect of salt concentration, carbonated vs. non-carbonated apatite, pH, hydration, and mutations (Shaw et al., 2004, Shaw and Ferris, 2008, Shaw and Ferris, 2008, Masica et al., 2011, Lu et al., 2013a, Lu et al., 2013b). These and other structural studies for HAP adsorbed amelogenins are summarized in Table 2. For WT LRAP, the N-terminus was found to be very helical and the C-terminus more consistent with an extended or random coil structure (Shaw and Ferris, 2008, Shaw and Ferris, 2008, Masica et al., 2011). Replacing the phosphoserine with serine resulted in a loosely coiled or random coil N-terminus with limited effect on the C-terminus, (Masica et al., 2011, Lu et al., 2013a, Lu et al., 2014) as summarized in a recent review (Shaw, 2015).

Table 2.

Summary of the major structural studies of amelogenin bound to a surface. In the protein recombinantly expressed by E. coli, the N-terminal methionine is not present, and the side chain of S16 is not phosphorylated. Full length murine (M) and porcine (P) amelogenin correspond to M179 and P173, respectively. In LRAP (murine), +P and −P denotes the phosphorylation state of S16. PBS – phosphate buffered saline; SCP – saturated calcium phosphate in 0.15 NaCl; co-mineralized – HAP mineralized in the presence of the proteins.

| Protein | N-terminal tag | Surface | Solution condition | Analysis technique | Type of structure studied | Structural feature of adsorbate | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LRAP + P LRAP-P | None | HAP particles | pH 7.4 | ssNMR | Orientation | C-terminus (A46) oriented next to HAP | Shaw et al, J. Biol. Chem., 2004 |

| LRAP + P LRAP-P | None | HAP particles | pH 7.4 | ssNMR | Secondary Dynamics Orientation | C-terminus (K54, V58) extended, mobile, next to HAP | Shaw et al, J. Phys. Chem. B, 2008 |

| LRAP-P | None | HAP particles | pH 7.4 SCP | ssNMR | Secondary Dynamics Orientation | C-terminus (A46, A49, K52) extended, mobile, next to HAP | Shaw et al, Biophys. J., 2008 |

| M179 | MRGSHHHHHHGS- | CH3, NH2, COOH-terminated SAMs, FAP | pH8 50 mM NaCl; solution nanospheres | AFM | Quaternary | monomers to oligomers | Tarasevich et al, J. Phys. Chem.B,, 2009 |

| LRAP + P | None | CH3, NH2, COOH-terminated SAMS | pH 7.4, PBS or SCP | AFM, ellipsometry | Quaternary | monomers | Tarasevich et al, J. Struct. Biol., 2010 |

| P173 | None | mica, NH2-terminated silanes on mica | pH 3.8, 25 mM NaOAc-HOAc; pH 8, 25 mM Tris•HCl; solution nanospheres | AFM | Quaternary | monomers to decamers | Chen et al, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2011 |

| LRAP + P LRAP-P | None | HAP particles | pH 7.4 SCP | ssNMR | Secondary Dynamics Orientation | N-terminus (G8, Y12, L15, V19, L23, K24, S28) Oriented near the surface, largely unstructured, dynamics and orientation modulated by phosphorylation | Masica et al, J Phys. Chem. C, 2011 |

| P173 | None | HAP particles; co-mineralized HAP | pH 7.2, PBS | FTIR | Secondary | Sensitive to pre-formed vs co-mineralized: β-sheet, PPII, random coil, β-turn/310 helix | Beniash et al; J. Dent. Res. 2012 |

| LRAP + P LRAP-P | None | HAP particles | pH 5.8, 7.4, 8.0; 50, 150, 200 mM, NaCl SCP | ssNMR | Secondary Orientation Dynamics | N-terminus (L15, V19, L23, K24, S28) Structure fairly stable to condition, orientation changes, K24 may be a critical residue | Lu et al, Biochem. 2013 |

| M179 | MRGSHHHHHHGS- | co-mineralized HAP | pH 7.8 | ssNMR | Secondary | β-sheet (K24, K173, K175) | Lu et al, J. Dent. Res., 2013 |

| LRAP + P | None | COOH-terminated SAM | pH 7.4 SCP | Neutron reflectivity | Tertiary Quaternary | oriented monomer | Tarasevich et al, J. Phys. Chem. B. 2013 |

| LRAP + P, LRAP-P LRAP-T21I | None | HAP particles, carbonated HAP particles | pH 7.4 50, 150, 200 mM NaCl SCP; 0.07, 0.4 mM Ca2+ | ssNMR | Secondary Dynamics Orientation | N-terminus (K24, S28) Significant sensitivity to conditions. CAP and Ca2+ induce helix, Confirms structural flexibility and suggests key residue | Lu et al, Front. Physiol, 2014 |

| M179 | MRGSHHHHHHGS- | HAP (100) | pH 8 | AFM | Quaternary | oligomers (25-mer average) | Tao et al, Langumuir, 2015 |

| M179 | None | 25 mM Tris•HCl solution nanospheres | |||||

| M179 | None | co-mineralized HAP | pH 8 | ssNMR | Secondary | β-sheet (Thr and Arg) α-helix (Thr) and anti-parallel intermolecular interactions |

Arachchige et al, Biophys. J. 2018 |

| M179 M179-(T21I) M179-(P41T) M179-(P71T) | None | HAP (100) | pH8 25 mM Tris•HCl | AFM ssNMR | Quaternary Secondary Dynamics | oligomers (21–45-mer average) all β sheet (K24, K173, K175) T21I more mobile | Tao et al, PNAS, 2019 |

The distance from the backbone and side chains of several residues in the N- and C- terminus relative to the HAP surface was also evaluated to understand the orientation of the protein on the surface. Both termini were close enough to the HAP surface to influence crystal growth, however, the C-terminus was consistently closer than the N-terminus, except when S16 was phosphorylated (Masica et al., 2011, Lu et al., 2013a, Lu et al., 2014). This experimental observation of the importance of the C-terminus in HAP binding was supported by a steered molecular dynamics computational study, which found that the COO- groups were important in interacting with the Ca2+ ions (Chen et al., 2007). Further, the mobility was studied for each of the backbone residues for which the structure and orientation was studied. The N-terminus was found to be more mobile than the C-terminus. Together, this suggests that the unstructured C-terminus is interacting very closely with the HAP surface, restricting its motion, and from this we conclude it is critical in interacting with HAP. The more structured N-terminus is further from the surface and more dynamic, suggesting that it may play another role, in addition to helping stabilize the protein on HAP. Combining the NMR constraints with the protein-surface docking methodology of Rosetta-Surface, the average structure was determined as shown in Fig. 12 (Masica et al., 2011).

Fig. 12.

One of the lowest energy LRAP-HAP structures from RosettaSurface calculations using the ssNMR constraints. The C-terminus is on the left and the N-terminus to the right. The calculations suggested a slight energetic preference for the 010 surface of HAP. Reproduced with permission from Masica et al., JPC, 2011.

As mentioned, a range of experimental conditions were varied in the ssNMR studies given the importance of the highly variable conditions seen during enamel development (Simmer and Fincham, 1995, Margolis et al., 2006) Specifically, the effects of pH values of 5.8, 7.4, and 8.0, ionic strength values of 0.05, 0.15, and 0.2 M, and the phosphorylation state on residues L15-V19, V19-L23, and K24-S28 in the N-terminal region of the protein were studied. Importantly, very little change in protein binding to the HAP surface was observed for all of the different preparation conditions examined (within ~10%) (Lu et al., 2013a, Lu et al., 2014). When bound to HAP, LRAP was found to be largely stable to the solution conditions tested, with the exception that the region from V19 to L23 transitioned from a random coil structure to a β-sheet structure when bound from a solution with an ionic strength of 0.2 M, but only when S16 was phosphorylated.

The experimental conditions with the biggest impact on LRAP’s secondary structure was the phosphorylation state of S16. The negative charge of the group at S16 moved the protein closer to the positive charges on the HAP surface. A couple of unexpected observations include: 1) phosphorylating S16 results in increased mobility of the backbone at L15, an observation that may facilitate function such as protein–protein interactions or proteolytic cleavage during amelogenesis; and 2) the structure of the protein from residues 15 to 23 did not change upon phosphorylation, however, the structure of LRAP bound to HAP from residues 24–28 changed from random coil to a loose helix when phosphorylated. Further, two distinct resonances were observed for K24, suggesting multiple co-existing structures that potentially interconvert. Computational evaluation suggested a turn at or near K24, and the significant structural change upon phosphorylation suggest that this residue or region could have functional importance (Lu et al., 2013a, Lu et al., 2014). Other studies have also highlighted the potential impact of phosphorylation in the structure and interaction of amelogenins with HAP (Le Norcy et al., 2011a, Le Norcy et al., 2011b, Wiedemann-Bidlack et al., 2011, Shin et al., 2020).

Due to the evidence for structural switching as a function of phosphorylation of S16, the K24 to S28 region was examined even more closely as a potential region of functional interest and was found to be much more sensitive to the solution conditions during binding than the L15-V19 and V19-L23 regions (Lu et al., 2014). The structure from K24 to S28 was a loose helix under a set of conditions defined as standard, including pH 7.4, ionic strength of 0.15 M, a binding surface of HAP, and 0.3 mg/mL of LRAP (Lu et al., 2014). When carbonated apatite was used as the binding surface or 0.4 mM Ca2+ was present in solution (eight times more than what was typically used), the structure tightened to become a nearly perfect helix. At low ionic strengths, the helix in this region loosened, much closer to a random coil structure. Perhaps even more indicative of a function is that the K24-S28 region is helical when lyophilized from solution, regardless of phosphorylation state, while the structure switches when bound to HAP. In solution, a residue in this region, W25, has been suggested to be important in stabilizing helices in the N-terminus, (Zhang et al., 2011) and in stabilizing protein–protein interactions (Bromley et al., 2011a). A region close to W25 has been found to interact with micelles (Chandrababu et al., 2014).

Another technique used to study the tertiary structure of LRAP bound to surfaces was neutron reflectivity (NR) (Tarasevich et al., 2013). Several residues in the C-terminus of LRAP were deuterated to increase the scattering length density (SLD) of the protein in that region and probe for the protein orientation relative to the distance from the NR surface, molecularly smooth COOH-terminated self-assembled mono-layers. Reflectivity curves were collected from three humid atmospheres with varying amounts of D2O and H2O and two polarization states for each sample. The six curves were simultaneously fit to determine an SLD profile as a function of the distance from the surface. The NR determined z-dimension of 32 Å was consistent with the diameter of the LRAP monomer determined by SV and Rosetta computer simulations (Tarasevich et al., 2015). The NR data suggested that the protein is not completely flat on the surface but has some portion away from the surface. Simulations of the SLD profiles using various models found that a protein orientation with the more hydrophilic, deuterated domains (C-terminal and inner N-terminal) near the surface and the more hydrophobic domains away from the surface had the best fit to the data. This orientation is consistent with the ssNMR REDOR experiments of LRAP adsorbed onto HAP (Masica et al., 2011). This data not only provided some of the first direct evidence of a tertiary structure of amelogenin on a surface, but of any biomineralization protein on a surface. While NR is a challenging technique with complicated instrumentation, sample preparation, and data fitting, it offers a lot of promise for probing surface adsorbed proteins for the right system.

3.2. Full length amelogenin bound to HAP

Secondary structure.

Over the last 10 years, our group has implemented ssNMR techniques that have allowed the characterization of the location of specific secondary structure of full length amelogenin adsorbed onto HAP for the first time. The development of ssNMR techniques which enabled the characterization of fully labeled proteins (Zech et al., 2005, Hong and Schmidt-Rohr, 2013, Tang et al., 2013, Mandala et al., 2017) allowed the adoption of new approaches with which to study amelogenin bound to HAP. Specifically, rather than needing to only label one or two precisely placed residues (i.e. the i and i + 4 residues strategy for LRAP), in principle the protein of interest could be labeled 100%, in the same way a solution state NMR protein is labeled, and a full structure could be generated. Importantly, this allowed larger proteins to be examined because there was no longer the requirement of introducing specific isotopic labels, a major advancement that allowed the structural investigation of full length amelogenin on HAP.

Due to the intrinsically disordered nature of the protein, using a 100% labeled sample resulted in far too much spectral overlap to allow interpretation, as shown by Shaw and coworkers (Lu et al., 2013a). Consequently, a minimal labeling scheme was adopted which focused on labeling only individual amino acids which are minimally represented in amelogenin (Lu et al., 2013a). To achieve this, the protein is expressed in non-isotopically labeled media, with the desired labeled amino acids added, resulting in residue specific labels in the expressed protein. By labeling amino acids that are minimally represented in the protein primary structure, fewer overall labeled residues are present and therefore, the potential for spectral overlap is reduced. For amelogenin, the few charged residues are of the most interest because of their likely interactions with HAP.

The initial residue-specific labeling focus for Shaw and coworkers was on Lys, of which there are only three, one in the N-terminus and two in the C-terminus (Fig. 1) (Lu et al., 2013a). The resulting data suggested that in the nanosphere, studied as an exceedingly concentrated gel, these three residues were in highly unstructured and dynamic regions of the protein (discussed above). Significant changes were observed in the NMR signatures of the protein when HAP crystals were grown in its presence. The protein was found to exist in two different states: one a relatively immobile β-sheet structure and the second a highly mobile random coil structure, interpreted as being protein that was more intimately associated with HAP and protein that was not, respectively. Further studies which reduced the amount of protein, and consequently, reduced the contribution of the mobile, unstructured species in the spectrum are consistent with this hypothesis (Arachchige et al., 2018). The ssNMR studies with site specific labeling in the Lys suggest that both the C and N-termini have β-sheet secondary structures upon adsorption to HAP.

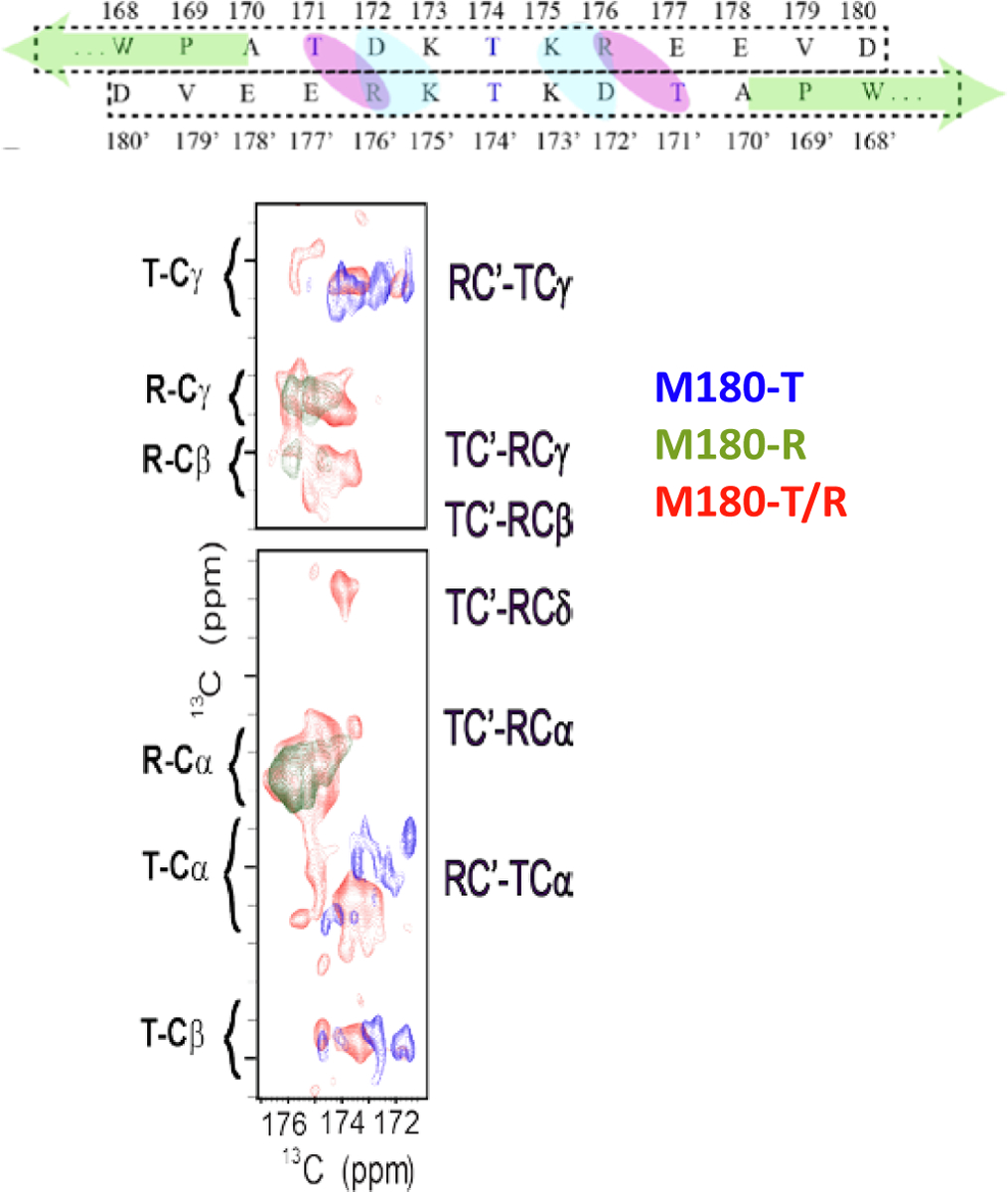

An additional study by Shaw and coworkers investigated the Arg and Thr residues for murine amelogenin in solution at pH 3 and precipitated in the presence of forming mineral (i.e. bound to HAP) (Arachchige et al., 2018). There is one Arg and one Thr in the N-terminus, one Arg and two Thr in the C-terminus, and three Thr in the central protein region. The ssNMR spectra in Fig. 13 show dashed lines representing the random coil resonance for the respective residues for the carbonyl (vertical) and the Cα carbon (horizontal). Resonances upfield (to the right, or to the top) of these dashed lines indicate residues in β-sheet structure and resonances downfield (to the left or to the bottom) represent residues with α-helical structure (generalized summary in Fig. 3). The spectra suggest that most of the Arg and Thr residues are in a β-sheet conformation. There are two Thr resonances that lie near to or downfield of the Cα chemical shift indicating that they may exist in a random coil or α-helical conformation. There are more resonances for both Arg (four) and Thr (eight) than there are residues, two for Arg and six for Thr, suggesting that there are multiple structures for at least some parts of the protein. Since the three Lys residues located in the N and C-termini in previous studies were found to have β-sheet structures, the β-sheet resonances found for Arg and Thr most likely represent the two amino acids for Arg and three amino acids for Thr that are located in the C and N-termini. The two Thr resonances that have helical or random coil conformations are likely to be the three Thr residues in the central part of the protein, though further studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Fig. 13.

The 2D 13C–13C DARR NMR spectra are shown. The black, bold dashed vertical and horizontal lines indicate the random coil values for the carbonyl carbon and the Cα carbon, respectively. At least eight Thr resonances are observed, though there are only six Thr residues, indicating multiple structures for at least two of the residues. Similarly, four Arg resonances are observed but only have two Arg residues. Further, the Arg residues are all upfield of the average random coil chemical shift for both Cα and carbonyl, indicating β-sheet structure. In general, this is true for the Thr, however, two of the Thr resonances are downfield of the Cα and on top of the carbonyl average chemical shift, suggesting either random coil or α-helical structures. Reproduced from Archchige et al., JDR, 2018.

The structure at the Arg and Thr residues was further analyzed by evaluating the chemical shifts in more detail. Fig. 14 shows the changes in chemical shifts from the random coil values for each residue.

Fig. 14.

The difference in the observed chemical shifts from the average random coil chemical shifts is shown for amelogenin in solution and bound to HAP. The larger differences observed for the protein bound to HAP indicates significantly more structure than for the protein in solution. Reproduced from Archchige et al., JDR, 2018.

The larger the difference in chemical shift from the random coil value, the more structured the protein (Fig. 3). The protein bound to HAP has much larger chemical shift differences from random coil values than the protein in solution, indicative of a much more structured protein. This is consistent with the definition of an intrinsically disordered protein which are seen to adopt structure in their functional form (Kragelj et al., 2013).

FTIR has also been used to study recombinant, full length porcine amelogenin in the presence of forming minerals under conditions similar to the ssNMR studies (Fig. 6) (Beniash et al., 2012). Quantification of the spectra by peak fitting methods suggested that the amount of intramolecular β-sheet structure increased upon amelogenin adsorption onto the forming mineral compared to the amount within solution nanospheres at pH 7.2 and pH 8.0. In contrast, the amount of intermolecular β-strand decreased upon amelogenin adsorption onto HAP and was explained by the loss of protein–protein interactions because of the disassembly of amelogenin nanospheres into smaller structures upon adsorption (Beniash et al., 2012, Tao et al., 2015). Amelogenin adsorption onto the forming mineral also resulted in a decrease in PPII structure and an increase in random coil structure compared to nanospheres in solution.

Both the ssNMR and FTIR data showed significant amounts of β-sheet secondary structure in amelogenin when adsorbed onto HAP mineralized in the presence of the protein and an increase in β-sheet structure compared to the protein in solution. Although the FTIR data reports on the average structure over the entire protein, ssNMR has advantages over FTIR in being able to assign specific secondary structures to specific regions of the protein. The ssNMR studies revealed that the β-sheets are localized in the C and N-terminal regions of the protein. Since the C-terminus is believed to be important in amelogenin adsorption onto surfaces, this result suggests that the β-sheet secondary structure is critical in promoting binding interactions between the C-terminus and HAP surface. The presence of β-sheet structure in the N-terminus also indicates the β-sheet structure may be important in promoting protein–protein interactions between monomers.

The FTIR data shows a significant amount of hydrated PPII and random coil structure within amelogenin and these structures are believed to be found in the central, proline-rich region of amelogenin (Table 2). The ssNMR data also found several random coil or α-helical resonances for Thr that likely represent the Thr residues in the central region of the protein. Further ssNMR studies with residues in the central part of the protein will be necessary to further characterize the local secondary structure.

The ssNMR studies of a nanosphere gel at pH 8.0 estimated the β-sheet content to be ~10% compared to the FTIR estimations of ~40% for nanospheres in solution at pH 8.0. The differences between the two methods may reflect the different protein concentrations used for the studies but may also reflect the difficulties in quantification for both methods. Further development of quantitation techniques is of interest in understanding how secondary structures change upon adsorption.

Protein-protein interactions.

The site specificity of ssNMR allows not only the observation of secondary structure and mobility, it also provides the opportunity to explore interactions between proteins. A recent cryo-TEM study of solubilized, frozen, untagged-recombinant amelogenin suggested that amelogenin self- assembled aligned in an anti-parallel fashion, overlapping only at C-termini (Fig. 8) (Fang et al., 2011). This interaction was probed using ssNMR which is uniquely suited to identify the molecular level details of this type of interaction. A dual labeling scheme that assumed the interaction was stabilized via salt bridges was used (Fig. 15): one protein was labeled with Arg (two in amelogenin) and one protein was labeled with Thr (six in amelogenin). The two proteins were mixed in equal parts and intermolecular interactions between the Arg and the Thr were investigated. Intermolecular interactions were observed, indicating that the C-termini are interacting. Several models were considered with molecular dynamics studies to determine if they were perfectly aligned in an anti-parallel orientation or if the alignment was offset. Either a perfect alignment or an under alignment which only aligned 12 of the C-terminal residues instead of all 13 fit the data equally well, consistent with the anti-parallel structure seen in the cryo-TEM studies (Fang et al., 2011).

Fig. 15.