Abstract

Backgrounds

The epidemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) is spreading across the world. As the first country who suffered from the outbreak, China has been taking strict and effective measures to contain the epidemic and treat the disease under the instruction of updating guidance.

Aims

To compare the changes and updates in China's clinical guidance for COVID‐19.

Methods

We explored China's experience in dealing with the epidemic by longitudinal comparison of China's clinical guidance for COVID‐19.

Results

As of March 4, there are 7 editions of the guidance. With the increasing understanding of COVID‐19, changes have been made in aetiology, epidemiology, pathology, clinical features, diagnostic criteria, clinical classification, and treatment.

Conclusions

We have made a summary of the changes and updates in China's clinical guidance for COVID‐19, which mirrors the deepening understanding of the disease over the course of fighting it, hoping to help clinicians worldwide.

1. INTRODUCTION

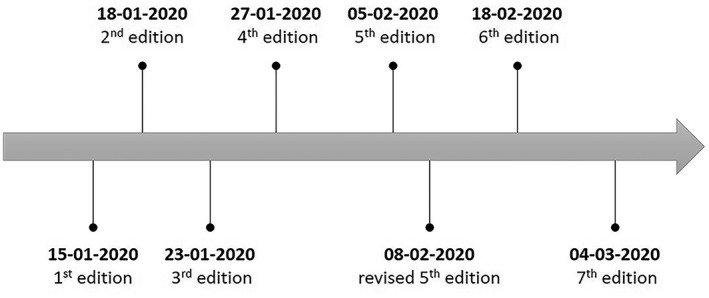

From December 2019, after multiple cases of novel coronavirus pneumonia start to appear in the City of Wuhan, an epidemic affecting China and the world had then begun. 1 With the deepening of Chinese experts' understanding of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19), multiple versions of China's clinical guidance have been made (available on the official website of the National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China, www.nhc.gov.cn). As of March 4, China National Health Commission published the 7th edition of clinical guidance (Figure 1). So far, the cases of COVID‐19 in China have decreased significantly, indicating that the prevention and control of the virus during this period have reached success in the current stage. This article reviews the changes in China's clinical guidance for COVID‐19, hoping to help clinicians worldwide.

FIGURE 1.

Timeline of China's clinical guidance for COVID‐19

2. CHANGES AND UPDATES IN CHINA’S CLINICAL GUIDANCE FOR COVID‐19

2.1. Aetiology

The pathogen of COVID‐19 is constantly being recognised. In the first three editions, we only knew that it was a novel coronavirus. The description of the coronavirus aetiology was based on the previous physicochemical understanding of coronavirus. With the study of the full‐length genomic sequence of the virus, 2 the characteristics of the pathogen were refined in the 4th edition.

The novel coronavirus (termed as SARS‐CoV‐2 by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses) shares more than 85% homology with SARS‐like coronavirus isolated from the bat (bat‐SL‐CoVZC45). 3 SARS‐CoV‐2 can be inactivated by ultraviolet, heat (56°C for 30 minutes), 75% ethanol (w/v), chlorine‐containing disinfectant, and chloroform.

2.2. Epidemiology

With the increase in the cases of COVID‐19 and the progress of epidemiological research, since the 4th edition of the guidance, the epidemiological characteristics of COVID‐19 have been specifically listed, including the source of infection, the route of transmission, and the susceptible population (See Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Changes in epidemiological understanding amongst editions

| Source of infection | Route of transmission | Susceptible population | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4th Edition | Infected patients are the main source of infection | Transmitted through respiratory droplets and contact | Human beings are generally susceptible |

| Revised 5th Edition | Infected patients (symptomatic or asymptomatic) are the main source of infection | Respiratory droplets and contact are the main routes of transmission, and Aerosol transmission is possible | No change |

| 6th Edition | No change | Aerosol transmission is possible when exposed to high concentration virus‐containing aerosols for a period of time and in a relatively closed environment | No change |

| 7th Edition | No change | SARS‐CoV‐2 has been isolated from stool and urine, special attention should be paid to human waste disposal and avoid contamination | No change |

2.3. Pathology

On February 17, Fusheng Wang et al 4 reported the pathological findings of COVID‐19, which showed bilateral diffuse alveolar damage with hyaline membrane formation and peripheral blood T cells over‐activation, indicating that the disease mainly damages lung and immune system, and the impairment in other organs is mostly secondary. Based on the results of the currently limited autopsy of histopathological specimens, the pathological manifestations of the disease have been added in the 7th edition.

2.4. Clinical features

2.4.1. Clinical manifestation

With the accumulation of experience in diagnosis and treatment, our understanding of the clinical characteristics of COVID‐19 is being deepened. (A) The 3rd edition of the guidance pointed out that COVID‐19 mainly showed fever, fatigue, and dry cough, and added descriptions of rare symptoms, complications, and severe symptoms in severe patients; (B) The 4th edition of the guidance added diarrhoea as one of the symptoms and noted the phenomena that some confirmed cases showed no signs of pneumonia, relatively mild symptoms in children, as well as greater mortality in elderly people, especially those with underlying chronic diseases. (C) In the 5th edition of the revised guidance further clarify that the incubation period ranges from 1 to 14 days, as compared with 3‐7 days shown in previous editions; (d) The 6th edition of the guidance added clinical symptom of myalgia and pointed out that severe cases may have multiple organ dysfunction syndromes; (e) The 7th edition added that some children and neonatal cases may have atypical symptoms, such as vomit, diarrhoea, or merely listlessness, and the pregnant female patients have similar manifestations with that of the patients of the same age.

2.4.2. Aetiological examination

COVID‐19's aetiology examination method is also constantly being improved. (a) In the 4th edition of the guidance, it was proposed that SARS‐CoV‐2 nucleic acids can be detected in nasopharyngeal swabs, sputum, lower respiratory tract secretions, and blood by RT‐PCR; (b) The 5th edition of the revised version of the guidance added stool test; (c) The 6th edition of the guidance pointed out that severe and critically ill patients often have elevated inflammatory factors and recommended collecting lower respiratory tract secretions in patients undergoing tracheal intubation; (d) In the latest version of the guidance, the next‐generation sequencing technology (NGS) method is added for the detection of nucleic acids, and the serological examination of the SARS‐CoV‐2 specific IgM, IgG antibody is also introduced.

2.4.3. Chest imaging

As an important lung disease examination method, chest CT plays an important role in the diagnosis of COVID‐19, 5 , 6 and it is also an important indicator for judging and detecting the change in the patient's condition, guiding the treatment, and predicting the development of the disease. Considering that false negatives in nucleic acid testing can lead to misdiagnosis, clinicians recommend that CT be included as a screening tool. Since the 3rd edition of the guidance, the CT characteristics of COVID‐19 were clarified.

2.5. Diagnostic criteria

The diagnostic criteria of COVID‐19 mainly include epidemiological history, clinical manifestations, and aetiological evidence. In the 7th edition of the guidance, suspected cases with one of the following aetiological or serological evidence can be identified as confirmed cases: (a) RT‐PCR detects positive for SARS‐CoV‐2 nucleic acid; (b) Sequencing of viral genes is highly homologous with SARS‐CoV‐2; (c) The SARS‐CoV‐2‐specific IgM and IgG antibodies are tested positive.

2.6. Clinical classification

The clinical classification of disease types is conducive to effective case management thus improving the cure rate. COVID‐19 clinical classification has been gradually improved since the 3rd edition of guidance. A comparison of clinical classification amongst editions is listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Changes in clinical classification amongst editions

| Mild type | Moderate type | Severe type | Critically severe type | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3rd Edition | — | — | Anyone of the following: (a) shortness of breath (RR ≥ 30 breaths/min); (b) Oxygen saturation ≤93%; (c) alveolar oxygen partial pressure/fraction of inspiration O2 (PaO2/FiO2) ≤300 mmHg; (d) chest imaging shows a significant progression of lesion >50% within 48 h; (e) with comorbidities requiring hospitalisation | Anyone of the following: (a) Respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation; (b) shock; (c) multiple organ failure needed ICU monitoring |

| 4th Edition | — | Fever and respiratory symptoms, and chest imaging displays pneumonia | Anyone of the following: (a) shortness of breath (RR ≥ 30 breaths/min); (b) Oxygen saturation ≤93% at rest; (c) PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 300 mmHg | No change |

| Revised 5th Edition | Symptoms are mild without pneumonia sign on chest imaging | No change | No change | No change |

| 6th Edition | No change | No change | Anyone of the following: (a) shortness of breath (RR ≥ 30 breaths/min); (b) Oxygen saturation ≤93% at rest; (c) PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 300 mmHg; (d) chest imaging shows a significant progression of lesion >50% within 24‐48 hours | No change |

| 7th Edition | No change | No change | Criteria for children: (a) Shortness of breath (<2 mo old, RR ≥ 60 breaths/min; 2‐12 mo old, RR ≥ 50 breaths/min; 1‐5 y old, RR ≥ 40 breaths/min; >5 y old, RR ≥ 30 breaths/min), excluding the effects of fever and crying; (b) Oxygen saturation ≤92% at rest; (c) Sighing respiration, flaring of alae nasi, three depressions sign, cyanosis, intermittent apnoea; (d) lethargy and convulsions; (e) Refuse to feed, signs of dehydration | No change |

2.7. Treatment

Antiviral therapy, including Interferon‐α inhalation, Lopinavir/Ritonavir, Chloroquine phosphate, Arbidol, and Ribavirin are recommended in the 7th edition of guidance. The treatment for COVID‐19 has been continuously updating. Table 3 concludes the changes in antiviral therapy amongst editions.

TABLE 3.

Changes in antiviral therapy amongst editions

| Name | Usage and dosage for adults | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4th Edition |

Interferon‐α Lopinavir/Ritonavir(200/50 mg) |

Inhalation, 5 million U, twice daily Oral administration, two capsules each time, twice daily |

— |

| Revised 5th Edition | +Ribavirin | Intravenously, 500 mg, 2‐3 times daily | Be aware of the side effects and drug interactions. |

| 6th Edition |

+Chloroquine phosphate +Arbidol |

Oral administration, 500 mg each time, twice daily Oral administration, 200 mg each time, three times daily |

It is not recommended to use three or more antiviral drugs at the same time. The course of treatment should be less than 10 d. Related medications should be stopped on the occurrence of intolerable side effects. |

| 7th Edition | No change | No change | For the treatment of pregnant women, the weeks of pregnancy should be considered, and medication should be as less influential to foetus as possible. Informed consent is required if the termination of pregnancy is needed. |

3. CONCLUSION

In the gradual understanding of COVID‐19, China's clinical guidance is constantly changing. For an emerging epidemic, we need to clarify its aetiology, epidemiology, pathogenesis, pathology, and clinical manifestations, so as to find accurate methods to cut off the transmission route, control the source of infection, and protect susceptible populations. The development of effective antiviral medication and vaccine plays a vital role in containing the COVID‐19 epidemic. At present, more and more institutions around the world are actively developing antiviral medicine and vaccines, hoping to succeed in the near future.

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None.

Wang Q‐C, Wang Z‐Y. Continuous focus on COVID‐19 epidemic: Changes in China’s clinical guidance. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75:e13869. 10.1111/ijcp.13869

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets analysed for this article can be found on the website (http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653p/new_list.shtml).

REFERENCES

- 1. Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al.; China Novel Coronavirus Investigating and Research Team . A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727‐733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270‐273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses . The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome‐related coronavirus: classifying 2019‐nCoV and naming it SARS‐CoV‐2. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5:536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Xu Z, Shi L, Wang Y, et al. Pathological findings of COVID‐19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:420‐422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guan W‐J, Ni Z‐Y, Hu Y, et al.; China Medical Treatment Expert Group for Covid‐19 . Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease in China. N Engl J Med. 2019;382:1708‐1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bernheim A, Mei X, Huang M, et al. Chest CT findings in coronavirus disease‐19 (COVID‐19): relationship to duration of infection. Radiology. 2020;295:200463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analysed for this article can be found on the website (http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653p/new_list.shtml).