Key Points

Question

How prevalent are financial hardships because of medical bills in families of children with congenital heart disease, and how do these hardships affect access to basic needs and medical care?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study including 188 families (weighted sample of 151 537 families), approximately 50% of US families of children with congenital heart disease reported experiencing financial hardship because of medical bills, which is associated with greater food insecurity and delays in care. These associations were stronger among patients with private insurance than those with Medicaid.

Meaning

Financial hardship because of medical bills is common among families of children with congenital heart disease and may adversely affect access to basic needs and medical care.

Abstract

Importance

Congenital heart disease (CHD) carries significant health care costs and out-of-pocket expenses for families. Little is known about how financial hardship because of medical bills affects families’ access to essential needs or medical care.

Objective

To assess the national prevalence of financial hardship because of medical bills among families of children with CHD in the US and the association of financial hardship with adverse outcomes.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional survey study used data on children 17 years and younger with self-reported CHD from the National Health Interview Survey of US households between 2011 and 2017. Data were analyzed from March 2019 to April 2020.

Exposures

Financial hardship because of medical bills was classified into 3 categories: no financial hardship, financial hardship but able to pay medical bills, and unable to pay medical bills.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Food insecurity, delayed care because of cost, and cost-related medication nonadherence.

Results

Of 188 families of children with CHD (weighted sample of 151 537 families), 48.9% reported some financial hardship because of medical bills, with 17.0% being unable to pay their medical bills at all. Compared with those who denied financial hardships because of medical bills, families who were unable to pay their medical bills reported significantly higher rates of food insecurity (61.8% [SE, 11.0] vs 13.6% [SE, 4.0]; P < .001) and delays in care because of cost (26.2% [SE, 10.4] vs 4.8% [SE, 2.5]; P = .002). Reported medication adherence did not differ across financial hardship groups. After adjusting for age, race/ethnicity, and maternal education, the differences between the groups persisted. The association of financial hardship with adverse outcomes was stronger among patients with private insurance than those with Medicaid.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, financial hardship because of medical bills was common among families of children with CHD and was associated with high rates of food insecurity and delays in care because of cost, suggesting possible avenues for intervention.

This cross-sectional study assesses the national prevalence of financial hardship because of medical bills among families of children with congenital heart disease in the US and the association of financial hardship with adverse outcomes.

Introduction

Congenital heart disease (CHD) affects nearly 1% of US children and is associated with significant health care costs. Recurrent hospitalizations, surgical procedures, and outpatient services create large expenditures for families of children with CHD, even for those who have insurance,1 and children with CHD frequently have additional comorbidities that contribute to out-of-pocket costs.2 Indirect costs from lost wages and caregiver responsibilities further compound the financial burden associated with direct medical care.

Recent data estimate that approximately 90% of families of children with CHD experience financial hardship.3 However, little is known about how financial hardship affects families’ ability to meet essential needs or obtain medical care. Studies on adults with atherosclerotic disease, cancer survivors, and families of children with medical complexities suggest that competing financial priorities may result in cost shifting away from patients’ medical care, which can negatively impact patient outcomes.3,4,5,6,7 We used data from the National Health Interview Survey to assess the national prevalence of financial hardship because of medical bills among families of children with CHD and the association of such hardship with food insecurity, delayed care because of cost, and cost-related medication nonadherence.

Methods

Data from the National Health Interview Survey between 2011 and 2017 were used for these analyses (eAppendix in the Supplement). Children 17 years and younger with a self-reported diagnosis of CHD were included.8 Participants were divided into 3 categories—no financial hardship because of medical bills, financial hardship because of medical bills but able to pay, and unable to pay medical bills—based on their responses to the following questions: “Have you had problems paying medical bills in the past 12 months?” and “Are you unable to pay medical bills at all?” Food insecurity was evaluated using the US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service 10-item questionnaire (score 3 to 10).9 Cost-related medication nonadherence was defined as skipping medication doses, taking less medicine, or delaying filling a prescription to save money at any time in the 12 months prior to responding to the survey. Delays in care because of cost were defined as the inability to afford follow-up or specialty care or delaying medical care because of cost in the 12 months prior to responding to the survey. The Institutional Review Board at Boston Children’s Hospital reviewed the study and determined that it did not represent human subjects research as defined in federal regulations. The study thus met regulatory requirements necessary to obtain a waiver of informed consent/authorization.

Sample characteristics were compared across financial hardship categories using survey-specific Rao-Scott χ2 tests for categorical variables and weighted linear regression for continuous variables. Financial hardship categories were compared between CHD and other disease groups using Rao-Scott χ2 tests. We evaluated the association of not being able to pay medical bills at all with food insecurity, delayed care because of cost, and cost-related medication nonadherence using logistic regression. Models were adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, maternal education, and annual income based on prior literature.4,5 Missing covariate data were minimal (less than 8% total) and were multiply imputed (n = 10 data sets) using the Markov chain Monte Carlo method. All analyses were performed using the survey procedures in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute).10All statistical tests were 2-sided with significance defined as P < .05.

Results

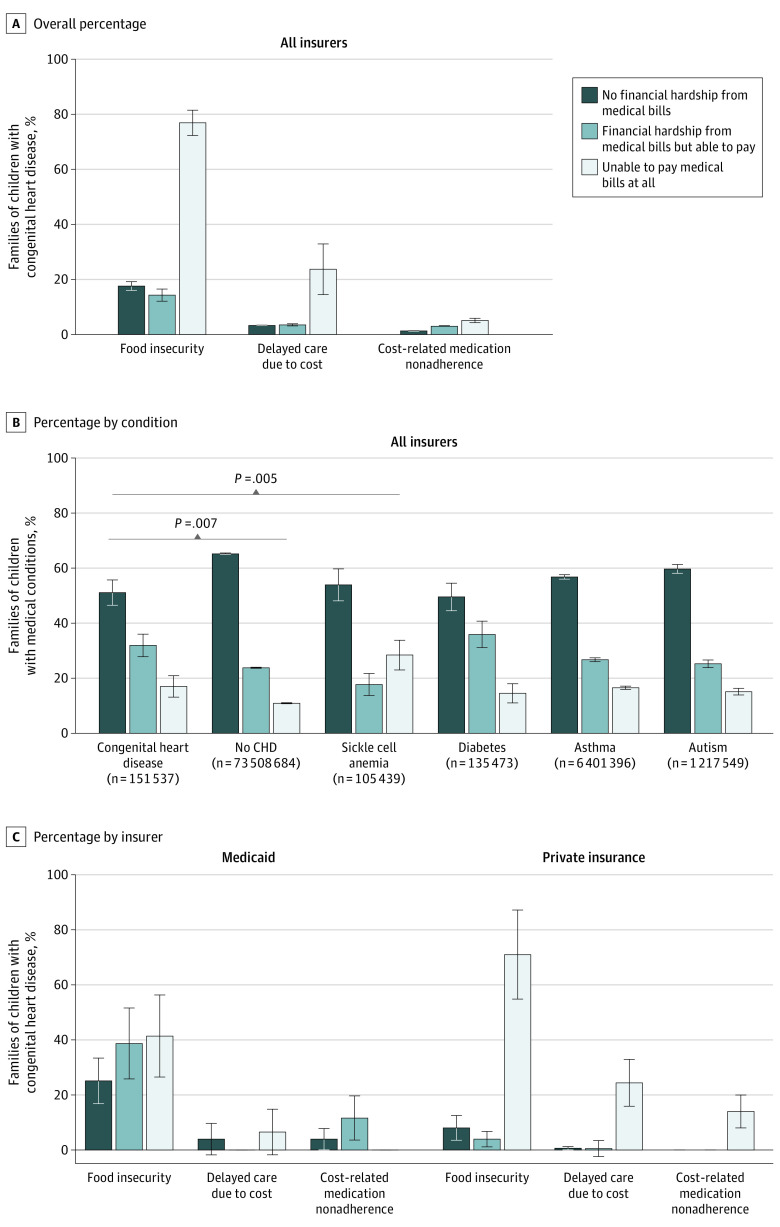

Of 188 families of children with CHD (weighted to a national sample of 151 537 families), 51.1% reported no financial hardship because of medical bills and 48.9% reported some financial hardship because of medical bills, including 31.9% who reported financial hardship but were able to pay medical bills and 17.0% who were unable to pay medical bills at all. Families that were unable to pay medical bills were significantly more likely to have incomes of less than 200% below the federal poverty line and less likely to be privately insured or to have prescription benefits compared with families without financial hardship (Table). Compared with those who denied financial hardships because of medical bills, families who were unable to pay their medical bills reported significantly higher rates of food insecurity (61.8% [SE, 11.0] vs 13.6% [SE, 4.0]; P < .001) and delays in care because of cost (26.2% [SE, 10.4] vs 4.8% [SE, 2.5]; P = .002) (Figure, A). Medication nonadherence was low (5% or less) in families both with and without financial hardship. Families of children with CHD had higher levels of financial hardship because of medical bills than families without children with CHD (48.9% [SE, 4.6] vs 34.8% [SE, 0.3]; P = .007) (Figure, B). Their distribution of financial hardship because of medical bills differed from that of families of children with sickle cell disease but not from those with diabetes, asthma, or autism (Figure, B).

Table. General Characteristics of Children With Congenital Heart Disease (CHD) by Financial Hardship Because of Medical Bills.

| Characteristic | % (SE)a | P valueb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total CHD population | No financial hardship because of medical bills | Financial hardship because of medical bills but able to pay | Unable to pay medical bills at all | ||

| Unweighted, No. | 188 | 94 | 62 | 32 | NA |

| Weighted, No. | 151 537 | 77 402 | 48 301 | 25 744 | NA |

| Age, mean (SE), y | 9.2 (0.2) | 9.5 (0.7) | 9.3 (0.8) | 8.1 (1.3) | .37 |

| Sex | .32 | ||||

| Male | 53.1 (2.3) | 56.6 (6.2) | 43.5 (8.1) | 60.7 (10.7) | |

| Female | 46.9 (2.3) | 43.4 (6.2) | 56.5 (8.1) | 39.3 (10.7) | |

| Race/ethnicity | .66 | ||||

| White | 66.9 (2.4) | 65.1 (6.2) | 74.8 (6.6) | 48.4 (12.6) | |

| Black | 10.2 (1.3) | 13.3 (5.5) | 5.7 (3.6) | 9.0 (6.4) | |

| Asian | 2.9 (0.2) | 3.3 (1.9) | 1.0 (1.0) | 4.7 (3.0) | |

| Hispanic | 20.0 (2.1) | 18.3 (4.0) | 18.4 (5.8) | 27.8 (11.9) | |

| Maternal education | .24 | ||||

| Some college or more | 65.7 (1.9) | 70.1 (5.5) | 67.8 (8.6) | 47.1 (13.5) | |

| High school or less | 34.3 (1.9) | 29.9 (5.5) | 32.2 (8.6) | 52.9 (13.5) | |

| Paternal education | .32 | ||||

| Some college or more | 72.8 (2.9) | 74.2 (6.0) | 77.8 (6.8) | 54.8 (17.3) | |

| High school or less | 27.2 (2.9) | 25.8 (6.0) | 22.2 (6.8) | 45.2 (17.3) | |

| Family income, FPL | <.001 | ||||

| <200% | 35.3 (1.6) | 28.3 (5.6) | 21.2 (5.9) | 79.1 (12.2) | |

| 200%-400% | 30.8 (3.0) | 26.0 (6.0) | 43.1 (8.1) | 20.7 (12.2) | |

| >400% | 33.9 (2.4) | 45.7 (7.0) | 35.7 (8.3) | 0.2 (0.2) | |

| Insurance status | .22 | ||||

| Uninsured | 4.8 (2.0) | 1.6 (1.6) | 3.7 (2.3) | 16.1 (11.0) | |

| Medicaid | 33.3 (2.2) | 33.5 (5.6) | 25.8 (6.4) | 46.9 (12.3) | |

| Private or other | 62.0 (2.5) | 64.9 (5.7) | 70.5 (6.7) | 36.9 (12.8) | |

| Prescription benefits | <.001 | ||||

| No | 49.6 (2.6) | 37.7 (6.0) | 48.3 (8.2) | 87.6 (6.9) | |

| Yes | 50.4 (2.6) | 62.3 (6.0) | 51.7 (8.2) | 12.4 (6.9) | |

| Dependent on medical equipment | .22 | ||||

| No | 84.6 (1.9) | 85.2 (4.2) | 89.6 (4.3) | 73.2 (10.4) | |

| Yes | 15.4 (1.9) | 14.8 (4.2) | 10.4 (4.3) | 26.8 (10.4) | |

| Food security | <.001 | ||||

| Secure | 78.5 (2.4) | 86.4 (4.0) | 87.2 (4.7) | 38.2 (11.0) | |

| Insecure | 21.5 (2.4) | 13.6 (4.0) | 12.8 (4.7) | 61.8 (11.0) | |

| Medication nonadherence because of cost | .45 | ||||

| No | 97.5 (0.1) | 98.7 (1.3) | 97.0 (2.2) | 94.9 (3.2) | |

| Yes | 2.5 (0.1) | 1.3 (1.3) | 3.0 (2.2) | 5.1 (3.2) | |

| Delayed care or failed to obtain care because of cost | .002 | ||||

| No | 91.5 (2.0) | 95.2 (2.5) | 94.9 (2.8) | 73.8 (10.4) | |

| Yes | 8.5 (2.0) | 4.8 (2.5) | 5.1 (2.8) | 26.2 (10.4) | |

Abbreviations: FPL, federal poverty level; NA, not applicable.

Data are presented as column percentages for weighted values. Rao-Scott weighted χ2 tests were used to evaluate differences across categorical variables and weighted linear regression was used to evaluate differences across continuous variables.

P values refer to differences between financial hardship groups, not the total CHD population.

Figure. Financial Hardship From Medical Bills According to Basic Needs, Diagnosis, and Insurer.

A, Overall percentage of families of children with congenital heart disease (CHD) across financial hardship categories. B, Percentage of families of children with CHD, no CHD, and select noncardiac chronic conditions reporting financial hardship because of medical bills. P values represent weighted Rao-Scott χ2 tests comparing the distribution of financial hardship reported by families of children with CHD with that of other conditions. Only significant P values are noted in the figure. When families reported both CHD and another illness, they were dichotomized into the CHD category and excluded from the other disease category. C, Percentage of families of children with congenital heart disease reporting financial hardship because of medical bills by Medicaid vs private insurance.

In unadjusted models, families unable to pay medical bills had increased odds of food insecurity and delayed care compared with families without financial hardship or with hardship but able to pay. After adjustment, these associations persisted (food insecurity: odds ratio, 11.2; 95% CI, 3.7-34.1; P < .001; delays in care: odds ratio, 3.3; 95% CI, 1.3-8.5; P = .01).

The association of financial hardship because of medical bills with adverse outcomes varied by insurance type (Figure, C). Among those with private insurance, families that were unable to pay medical bills had significantly higher food insecurity, delayed care, and medication nonadherence than those without financial hardship (food insecurity: 70.9% [SE, 8.3] vs 8.0% [SE, 1.8]; delays in care: 24.4% [SE, 4.0] vs 0.6% [SE, 0.1]; medication nonadherence: 13.9% [SE, 2.3] vs 0% [SE, 0]). The differences in these outcomes were smaller across financial hardship categories among children insured by Medicaid (food insecurity: 41.4% [SE, 7.7] vs 25.1% [SE, 4.4]; delays in care: 6.5% [SE, 0.9] vs 3.9% [SE, 0.3]; medication nonadherence: 0% [SE, 0] vs 3.9% [SE, 0.3]). Significant interactions between financial hardship and insurance type were observed for both food insecurity and medication nonadherence; however, the interaction for delays in care did not reach statistical significance.

Discussion

Using data from a nationally representative survey of households, this study found that nearly 50% of families of children with CHD reported financial hardship because of medical bills, with 17% of families being unable to pay their bills at all. Financial hardship was associated with higher rates of food insecurity and delayed care because of cost. The association of financial hardship because of medical bills with adverse outcomes was stronger among patients with private insurance than those with Medicaid.

Prior studies have shown that families of children with CHD experienced financial burdens because of out-of-pocket expenses, missed work, job loss, child care demands, caregiving hours, and medical needs not covered by insurance.3,11 Our study adds to this literature by examining the association of financial hardship because of medical bills with other expenses.

The interaction between insurance type and financial hardship because of medical bills may be related to several factors. In adults, enrollment in Medicaid is associated with lower out-of-pocket spending and lower likelihood of catastrophic financial burden.5,12 The higher prevalence of financial hardship among families of children with CHD with private insurance may be related to the high cost of deductibles or copayments accompanying private insurance plans or to the cost of more expensive plans with fewer benefits for low-income families that do not qualify for Medicaid. Furthermore, individuals who pay for a share of their health care services use fewer health services than those who receive free care.13

Studies have shown that financial hardship is associated with worse patient-reported outcomes.14 Moreover, food insecurity is associated with worse cardiovascular and other health outcomes, which could lead to a higher strain on our health care system as these children become adults.15

Limitations

Our study had several limitations. The number of patients in some insurance categories was small. The National Health Interview Survey data does not include expense data, exact household income data, or state-specific data, precluding analyses of these variables. Additionally, because the National Health Interview Survey does not account for dual insurance coverage, we were unable to analyze the association of dual coverage with financial hardship because of medical bills.

Conclusions

In summary, a large percentage of families of children with CHD experienced financial hardship because of medical bills, which is associated with difficulties meeting basic needs and obtaining medical care. Further studies should explore whether systematic assessment of families’ financial situations during CHD care could improve outcomes.

eAppendix. National Health Information Survey and definitions of medical conditions.

References

- 1.Arth AC, Tinker SC, Simeone RM, Ailes EC, Cragan JD, Grosse SD. Inpatient hospitalization costs associated with birth defects among persons of all ages—United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(2):41-46.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=28103210&dopt=Abstract doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6602a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen MY, Riehle-Colarusso T, Yeung LF, Smith C, Farr SL. Children with heart conditions and their special health care needs—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(38):1045-1049.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=30260943&dopt=Abstract doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6738a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McClung N, Glidewell J, Farr SL. Financial burdens and mental health needs in families of children with congenital heart disease. Congenit Heart Dis. 2018;13(4):554-562.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=29624879&dopt=Abstract doi: 10.1111/chd.12605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valero-Elizondo J, Khera R, Saxena A, et al. Financial hardship from medical bills among nonelderly U.S. adults with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(6):727-732.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=30765039&dopt=Abstract doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gotanda H, Jha AK, Kominski GF, Tsugawa Y. Out-of-pocket spending and financial burden among low income adults after Medicaid expansions in the United States: quasi-experimental difference-in-difference study. BMJ. 2020;368:m40.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=32024637&dopt=Abstract doi: 10.1136/bmj.m40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomson J, Shah SS, Simmons JM, et al. Financial and social hardships in families of children with medical complexity. J Pediatr. 2016;172:187-193.e1.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=26897040&dopt=Abstract doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.01.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zheng Z, Jemal A, Han X, et al. Medical financial hardship among cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer. 2019;125(10):1737-1747.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=30663039&dopt=Abstract doi: 10.1002/cncr.31913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parsons VL, Moriarity C, Jonas K, et al. Design and estimation for the National Health Interview Survey, 2006-2015. Accessed on January 14, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_02/sr02_165.pdf [PubMed]

- 9.Economic Research Services . U.S. adult food security survey module: three-stage design, with screeners. Accessed July 14, 2020. https://www.ers.usda.gov/media/8279/ad2012.pdf

- 10.National Center for Health Statistics . Variance estimation guidance, National Health Interview Survey, 2016-2017. Accessed on January 14, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/methods.htm.

- 11.Connor JA, Kline NE, Mott S, Harris SK, Jenkins KJ. The meaning of cost for families of children with congenital heart disease. J Pediatr Health Care. 2010;24(5):318-325.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=20804952&dopt=Abstract doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2009.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nguyen KH, Sommers BD. Access and quality of care by insurance type for low-income adults before the Affordable Care Act. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(8):1409-1415.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=27196646&dopt=Abstract doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brook RH, Keeler EB, Lohr KN, et al. The Health Insurance Experiment: a classic RAND study speaks to the current health care reform debate. Accessed April 28, 2020. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_briefs/2006/RAND_RB9174.pdf

- 14.Abel GA, Albelda R, Khera N, et al. Financial hardship and patient-reported outcomes after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22(8):1504-1510.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=27184627&dopt=Abstract doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Myers CA, Martin CK, Newton RL Jr, et al. Cardiovascular health, adiposity, and food insecurity in an underserved population. Nutrients. 2019;11(6):E1376.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=31248113&dopt=Abstract doi: 10.3390/nu11061376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. National Health Information Survey and definitions of medical conditions.