Abstract

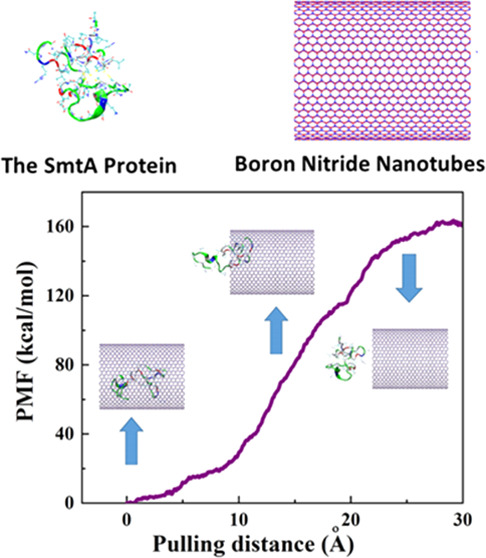

Nanotubes have been considered as promising candidates for protein delivery purposes due to distinct features such as their large enough volume of cavity to encapsulate the protein, providing the sustain and target release. Moreover, possessing the properties of suitable cell viabilities, and biocompatibility on the wide range of cell lines as a result of structural stability, chemical inertness, and noncovalent wrapping ability, boron nitride nanotubes (BNNTs) have caught further attention as protein nanocarriers. However, to assess the encapsulation process of the protein into the BNNT, it is vital to comprehend the protein–BNNT interaction. In the present work, the self-insertion process of the protein SmtA, metallothionein, into the BNNT has been verified by means of the molecular dynamics (MD) simulation under NPT ensemble. It was revealed that the protein was self-inserted into the BNNT through the protein–BNNT van der Waals (vdW) interaction, which descended and reached the average value of −189.63 kcal·mol–1 at 15 ns of the simulation time. The potential mean force (PMF) profile of the encapsulated protein with increasing trend, which was obtained via the pulling process unraveled that the encapsulation of the protein into the BNNT cavity proceeded spontaneously and the self-inserted protein had reasonable stability. Moreover, due to the strong hydrogen interactions between the nitrogen atoms of BNNT and hydrogen atoms of SmtA, there was no evidence of an energy barrier in the vicinity of the BNNT entrance, which resulted in the rapid adsorption of this protein into the BNNT.

1. Introduction

In the recent decade, advancements in designing a new concept and strategies for the therapeutics delivery have emerged based on the simple, low-cost, and adjustable nanomaterials. In this regard, experiments based on the chemical and physical parameters including the solubility, stability, ζ-potential, particle size, surface morphology, and functional groups have been conducted;1−3 however, these experiments are time-consuming and, in most cases, the parameters that are studied have unrecognizable effects on each other. Therefore, it is necessary to use computational methods to check any of the physical, chemical, and even biological parameters before any experiment.4,5

Nanotube (NT)-based drug delivery systems have attracted a lot of attention as nanovehicles due to their distinct properties such as large enough interior volume for drug encapsulation,6,7 and their distinctive surfaces that provide the practical functional groups including carboxylates and hydroxyls for potential functionalization to improve the selectivity as well as the sustained release for targeted delivery applications.8−10 Besides the benefits of sustained and targeted release to obviate the side effects of drugs,11,12 these hollow nanocarriers bring the advantages of drug protection from environmental tension, oxidization, and other destructive reactions13 along with the ability to penetrate into bacteria, cells, and tissues.14 Several reports regarding the use of hollow mesoporous nanotubes as a nanocarrier for the delivery of protein- and peptide-based therapeutics have been conducted and revealed that the physicochemical properties of these nanocarriers play an important role in this procedure.15−17 In addition, these carriers are considered as the next-generation precursors for the synthesis of new types of bacterial ghosts for immunization and therapeutics delivery as well.18 Carbon nanotubes (CNTs), the best-known hallow nanovectors,19 have been widely applied as nanocarriers for biomolecules including peptides,20 proteins,21 and DNA.21 However, due to the possible cytotoxicity caused by CNTs, the usage of carbon-based nanotubes has been restricted in biomedical applications.19,22 Instead, boron nitride nanotubes (BNNTs) have emerged as alternatives to CNTs due to their prominent features such as nontoxicity and biocompatibility as a result of their structural stability and chemical inertness.23,24 Moreover, because of the superior partial charges of the BNNTs over CNTs, they demonstrate higher permeation coefficients in the water as a result of considerable polarization.25 However, pure experimental tools cannot capture the molecular image of nanotube–drug interaction.

Considering the theoretical research studies employed in the prediction of the performance of the BNNTs as nanocarriers of biomolecules, it can be understood that the interaction between the BNNT and the biomolecule plays a vital role in the encapsulation process. For example, Roosta et al.26 studied the insertion process of gemcitabine in the BNNT (18, 0) and its release performance using the releasing agent through molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. They reported that gemcitabine is successfully located at the center of the BNNT spontaneously, as reflected in the negative interaction energy value of −0.9 kcal·mol–1. In terms of the encapsulated gemcitabine release, the releasing agent is introduced into the system and moved inside the BNNT, which subsequently resulted in the drug release with a total potential energy difference of −140.1 kcal·mol–1. In another work done by Mirhaji et al.,27 the effect of water/ethanol ratio on the encapsulation process of the anticancer drug of docetaxel into the BNNT (13, 13) has been explored using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. According to the calculated van der Waals (vdW) energies, the BNNT–docetaxel systems containing 60 and 75% showed the weakest interaction between the drug and the BNNT. The drug delivery performance of the OH-functionalized BNNT is also studied by Mortazavifar et al.28 through the density functional theory (DFT) computations and MD simulations. The adsorption energy calculated by means of DFT suggested that the anticancer drug (Carmustine (CMT)) is attached to the surface of the BNNT via hydrogen bonding with hydroxyl groups on the surface of the nanotube. Moreover, they reported that the increase in the Carmustine concentration and temperature enhances the vdW force between the OH-functionalized BNNT and the aforementioned drug. The adsorption processes of two anticancer drugs, namely, temozolomide (TMZ) and carmustine (CMT), into the BNNT(6, 6) cavity are compared by Xu et al.29 based on DFT calculations. They revealed that the adsorption energies of these drugs in the inner wall of the BNNT are remarkably higher than those on the outer wall. Moreover, the adsorption of TMZ on the surface of the nanotube occurred through both π–π and electrostatic interactions, which resulted in the larger adsorption energy compared to the CMT/BNNT system with electrostatic interactions. Khatti et al.30 studied the penetration rate of carboplatin drug into the BNNT and the BNNT having 18 hydroxyl groups on one edge. They underlined that the hydroxyl groups facilitate the insertion of drugs into the nanotube cavity.

In the light of the above finding, in the desired BNNT-based drug delivery system, the drug should have the ability to pass the potential barrier at the entrance of the BNNT and subsequently be encapsulated stably as a result of the interior deep potential. Therefore, there is a need to provide a computational research to evaluate the encapsulation behavior of the BNNT as a nanocarrier, the stability of the encapsulated biomolecule through the calculations of vdW interaction between the drug and the nanotube during the encapsulation process, and the potential of the mean force (PMF) of the encapsulated molecule respectively. SmtA as a zinc-fabricated gene is a kind of bacterial metallothionein (metal-binding protein), which significantly contributes to intercellular homeostasis of zinc and protects tissues and cells against oxidation by free radicals and also toxicity arising from heavy metals.31−33 The objective of this work was to assess the performance of the BNNT as a nanocarrier in an aqueous medium for protein delivery purposes by means of the MD simulations. The encapsulation of the protein SmtA into the BNNT was evaluated through the estimation of the vdW interaction between the protein and the BNNT. In addition, the stability of the protein in BNNT was investigated by calculation of the potential of the mean force (PMF) of the encapsulated protein.

2. Computational Details

In the current work, the molecular dynamics (MD) calculation was performed using Large-Scale Atomic/Molecular Simulator (LAMMPS) software34 to investigate the insertion process of the protein SmtA into the boron nitride nanotube (BNNT) and subsequently the stability of the encapsulated protein in the BNNT. The protein SmtA with the ID code of 1JJD was selected from the protein data bank. This ellipsoidal protein consists of a cleft lined with His-imidazole and Cys-sulfur ligands binding four zinc ions in a Zn4Cys9His2 cluster. Two ZnCys3His and two ZnCys4 sites are attached by thiolate sulfurs of five Cys ligands and caused the formation of two rings with six members.33 The visualization was obtained using VMD.35 In accordance with the size of SmtA, the armchair BNNT (28, 28) with a length of 48.8 Å has been selected as a nanocarrier for this protein. The axial direction of the nanotube was parallel to the z-axis of the simulation box.

At the beginning of the simulation, SmtA was placed at the initial distance of 2 Å from the BNNT. The complex of BNNT and SmtA was immersed in the simulation box consisting of TIP3P water molecules with periodic boundary conditions. Then, counterions were introduced into the simulation box to neutralize the simulated solution. Tersoff potential was applied to consider the interaction between boron and nitrogen.36 All MD simulations were done using the CHARMM27 force field.37 For an investigation of the protein encapsulation process, first, the system was minimized in the NVT ensemble at 300 K, while the BNNT was fixed. Next, the MD runs were performed in the NPT ensemble for 15 ns with the time step of 2 fs. Considering van der Waals (vdW) interaction, the inner and outer cutoff distances for the Lennard–Jones potential and Coulombic potential were 8 and 12 Å, respectively. The Lorentz–Berthelot combination rule was applied to estimate the parameters of the Lennard–Jones potential for cross-vdW interactions between nonbonded atoms.38 The vdW interaction between SmtA and the BNNT can be obtained as below35

| 1 |

where EvdW–int is the vdW energy between SmtA and the BNNT, ESmtA+BNNT corresponds to the vdW interaction of SmtA combined with BNNT. ESmtA and EBNNT refer to the vdW energies of SmtA and the BNNT, respectively.

In terms of the stability of the encapsulated drug in the BNNT, an external force was applied to the encapsulated SmtA along the z-axis of the nanotube to pull it out from the BNNT in the direction opposite to the penetrating process. The pulling velocity and spring constant k were 0.005 Å ps–1 and 15 kcal·mol–1·Å–2, respectively.39 The pulling process was repeated ten times to obtain the potential of the mean force (PMF) profile according to Jarzynski’s equality as37

| 2 |

where ΔG and W are the free energy difference between two states and the performed work on the system, respectively. β is equal to (KBT)−1 where KB refers to the Boltzmann constant.

Langevin dynamics was applied to obtain the temperature of the system about 300 K. Moreover, the pressure of 101.3 KPa was fixed using the Langevin piston Nosé–Hoover method.40

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Localization of SmtA within the Protein–BNNT Complex

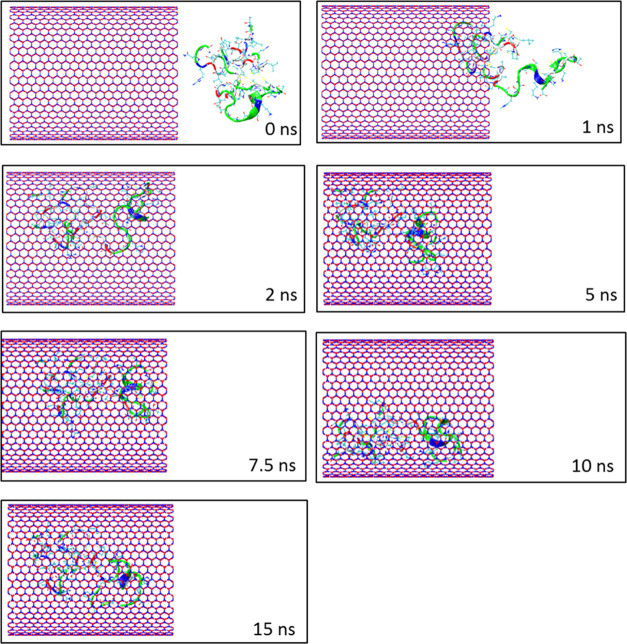

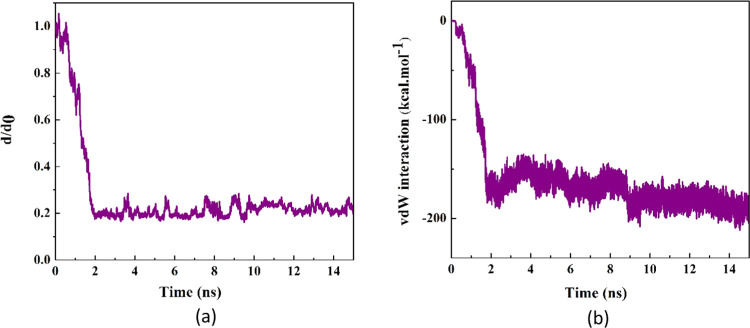

The self-insertion of the protein SmtA into the BNNT (28, 28) cavity in the water simulation box was kept under observation through MD simulation. Figure 1 demonstrates the snapshots captured by VMD software at various simulation times. As observed, SmtA was completely encapsulated into the BNNT cavity and showed reasonable stability until 15 ns. The normalized center-of-mass (CoM) distance between the protein and the BNNT (d/d0) as a function of the simulation time is shown in Figure 2a. The fluctuation of the d/d0 curve at the initial time of the simulation was related to the self-adjustment of the protein before entering into the BNNT. After that, the value of the d/d0 decreased dramatically to the value of 0.2 so that the insertion process was completed at 2 ns. With passing time, it was seen that the CoM distance between the protein and the BNNT experienced negligible changes and fluctuated around the value of 0.2 until the termination of simulation at 15 ns.

Figure 1.

Representative snapshots of insertion of the protein SmtA into an armchair BNNT (28, 28) at various times. For clarity, molecules of water have not been shown.

Figure 2.

(a) d/d0 (normalized CoM distance where d0 is the initial CoM distance) between the protein SmtA and BNNT as a function of simulation time. (b) vdW interaction between the protein SmtA and the BNNT (28, 28) as a function of simulation time.

The van der Waals (vdW) interaction energy is an important parameter to predict the encapsulating behavior of the nanocarrier so that the decrease in the vdW energy during the insertion process of the protein in the BNNT corresponds to the affinity of the protein to the BNNT. Figure 2b represents changes in the SmtA–BNNT vdW interaction energy as a function of simulation time. As observed, the value of the vdW interaction energy between the protein SmtA and BNNT dwindled by decreasing the CoM distance between the protein and the BNNT during the insertion process and reached an approximate value of −189.63 kcal·mol–1 at the end of the simulation. The similar downtrends of the changes in the vdW interaction energy in the systems containing DNA oligonucleotides–CNT and protein–CNT complexes in which the insertion process of the biomolecules into the nanotube occurred spontaneously have been reported by Gao et al.41 and Kang et al.,42 respectively. In the first 2 ns of simulation, the peptide moves rapidly toward the BNNT cavity with no evidence of the pause in the vicinity of the BNNT entrance. This was revealed as the dramatic drop in the value of the vdW interaction energy of the systems during this period. It can be explained that hydrogen bonding between the nitrogen atoms of the BNNT and hydrogen atoms of the protein caused a strong interaction between the protein and the BNNT, which subsequently passes the energy barrier caused by the hydrogen-bonding networks of water molecules accumulated at the entrance of the BNNT.43 After the encapsulation of the protein inside the BNNT, the vdW energy decreased with fluctuation in the range between the values of −200 and −150 kcal·mol–1, which showed a strong interaction in the protein–BNNT complex. Comparing the encapsulation process of SmtA into the CNT studied by Kang et al.39 and into the BNNT investigated in the present work, it was clarified that SmtA was absorbed into the BNNT cavity in the shorter time span (3.9 ns shorter). However, the adsorption of SmtA into the CNT not only occurred slower but also a pause in this process was observed due to the energy barrier in the vicinity of the CNT.

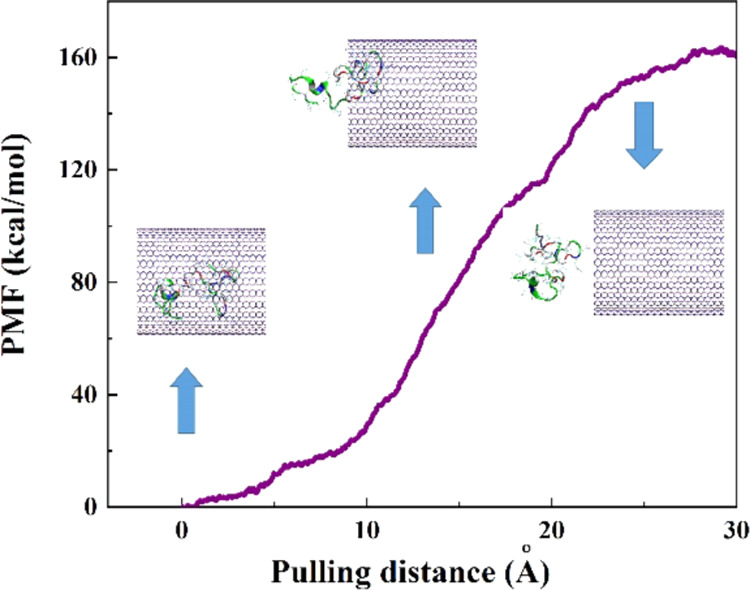

3.2. Free Energy Calculation from MD Simulation

After the termination of the simulation at 15 ns, the pulling process with the velocity of 0.005 Å ps–1 (chosen according to the velocity of the encapsulation process) was performed on the encapsulated protein through the MD simulation to obtain the potential of the mean force (PMF) profile. This pulling process was simulated ten times so that the average value of work (W) at every pulling distance was computed, which was illustrated as the PMF profile in Figure 3. Moreover, the snapshots related to three positions of the protein along the z-axis corresponding to the BNNT are displayed in this figure. As observed, the value of free energy increased during the simulation of the pulling process and reached a value of 160 kcal·mol–1 at the pulling distance of 30 Å, which was 60 kcal·mol–1 higher than the obtained free energy for the SmtA–CNT complex studied by Kang et al.39 This shows that the SmtA–BNNT complex possesses more stability compared to the SmtA–CNT complex in water due to a stronger hydrogen bonding. However, the encapsulation process of this protein into both BNNT and CNT occurred spontaneously due to the negative values of the free energy of −160 and −100.2 kcal·mol–1, respectively.

Figure 3.

Potential of the mean force (PMF) computed from 10 pullings through the MD simulation. The images represent the positions of the protein SmtA corresponding to the z-coordinate along the BNNT at some key positions.

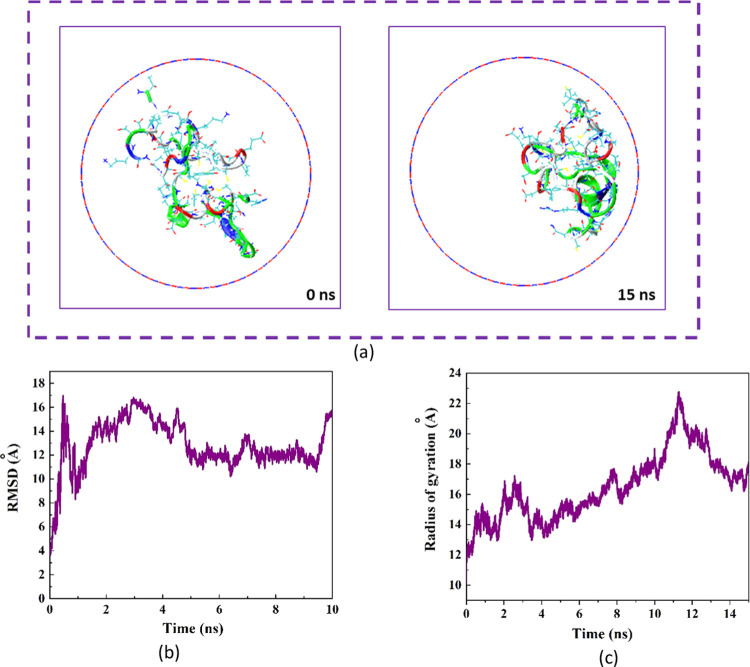

3.3. Variations in the Conformation of the Protein SmtA

The structural changes in the protein in the presence of BNNT at 0 and 15 ns of MD simulation are shown in Figure 4a. The image on the left illustrates the snapshot related to the natural form of the protein immersed in the water molecules at 0 ns of MD simulation. The protein has an ellipsoidal conformation in which hydrophilic groups fabricate the outer surface. The image on the right shows the snapshot of the encapsulated protein′s conformation, which was matched to the geometry of the BNNT at 15 ns of the simulation time. In other words, the protein was absorbed on one side of the interior wall of BNNNT with its hydrophobic surface. Similar variations in arrangement and configuration of the encapsulated drug (doxorubicin) in the CNT cavity affected by the changes in the chirality and diameter of CNT was reported by Zhang et al.44

Figure 4.

(a) Axial views of the protein SmtA at 0 and 15 ns in the MD simulation. For the sake of clarity, molecules of water have not been shown. (b) Root mean square deviation (RMSD) of the protein SmtA as a function of simulation time. (c) Radius gyration of the protein SmtA as a function of simulation time.

Figure 4b demonstrates the variations in the root mean square deviation (RMSD) corresponding to the changes in the protein conformation as a function of simulation time. As observed, before the complete insertion of protein inside the BNNT by 1.5 ns, the RMSD changed significantly, which was attributed to the intense conformational alteration of the protein influenced by the high SmtA–BNNT vdW interaction during the movement of the protein into the BNNT. However, after the encapsulation of SmtA into the BNNT, the RMSD varied continuously due to the self-adjustment of the protein according to the interior geometry of the BNNT, which was accompanied by the phase separation between the hydrophilic and hydrophilic groups absorbed on water solvent and BNNT, respectively. A similar difference in the affinity of the hydrophobic and the hydrophilic parts to the solvent and the nanotube was also reported in the system containing larger biomolecules.45

In addition to RSMD calculation, monitoring the variations in the gyration radius of the protein during the encapsulation process provides insight into the structural changes of the protein. Figure 4c shows the changes in the gyration radius as a function of the simulation time. As can be seen, the structure of the protein was stretched affected by the protein–BNNT vdW interaction, which was revealed as a higher gyration radius during the encapsulation process comparing the natural state of the protein.

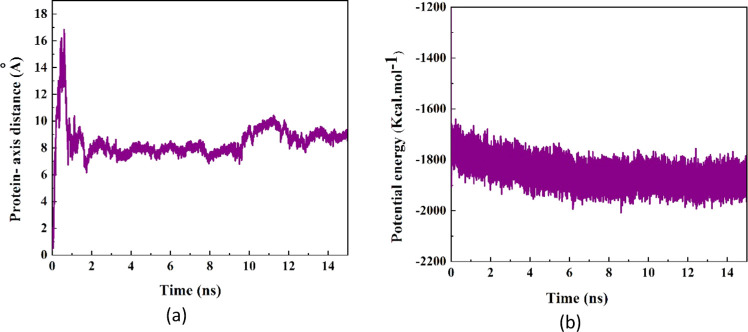

The alteration in the distance between the CoM of the protein SmtA and the central axis of the BNNT during the simulation time is depicted in Figure 5a. As shown, at the beginning of the simulation time, the protein was placed in a position in the simulation box so that the CoM of the protein was located on the central axis of the BNNT. Affected by the vdW interaction, the protein SmtA was then moved toward one side of the BNNT wall, and subsequently the SmtA–axis distance increased to 17 Å at 0.11 ns. However, this conformation of the protein was unstable and changed through the probable adsorption to other sidewalls of the BNNT, which resulted in a sudden drop in the cRW3–axis distance. After the complete insertion of the protein in the BNNT at 2 ns, there was a competition among the BNNT and water molecules to adsorb hydrophobic and hydrophilic groups of the protein, respectively, which caused a continuous alteration in the distance between the CoM of the protein SmtA and subsequently a moderate fluctuation in the SmtA–axis distance curve in a specified range of 6–10 Å.

Figure 5.

(a) Distance between the CoM of the protein SmtA and the central axis of the BNNT as a function of simulation time. (b) Potential energy of the protein SmtA as a function of simulation time.

Figure 5b shows the potential energy variations of the protein SmtA during the encapsulation procedure. It was seen that the potential energy of SmtA decreased during the first 2 ns of the encapsulation process, which is in favor of the rapid insertion of SmtA inside the BNNT cavity due to the high SmtA–BNNT vdW interaction energy. While the unfavorable increase in potential energy of the SmtA–CNT system was reported at the beginning of the simulation process.39 After the completion of the encapsulation procedure, the potential energy of the peptide fluctuated around the value of −1850 kcal·mol–1, which represents continuous changes in the conformation of the protein.

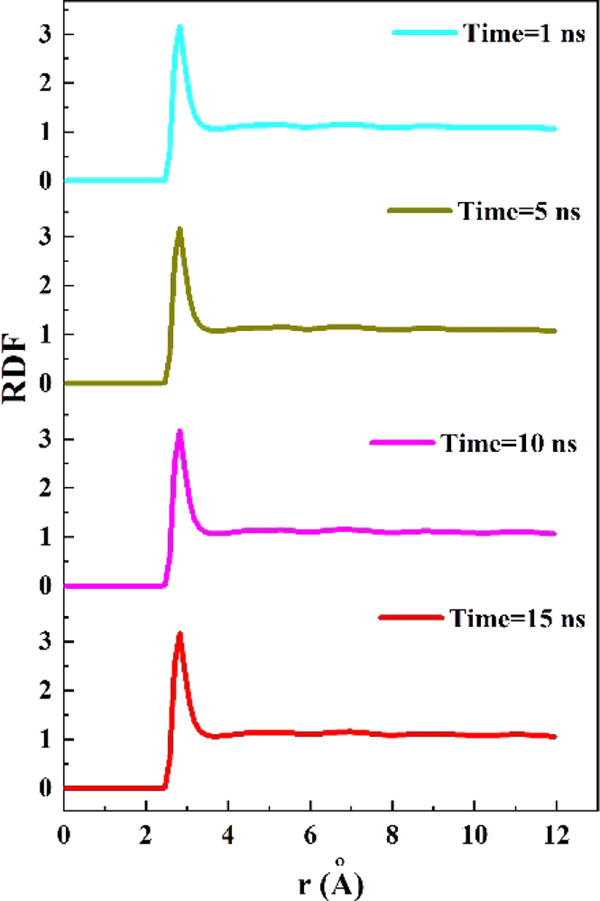

Radial distribution function (RDF) of the water molecules at various simulation times were determined to provide the estimation of the structure and distance between the water molecules in the simulation box.46Figure 6 shows the RDF curves of water molecules in the simulation box at 1, 5, 10, and 15 ns of simulation time. As observed, the emergence of similar sharp peaks at the distance of 3 Å indicated that the distance between the water molecules was 3 Å during the simulation process.47 This means that the water molecules were in the liquid phase during the insertion process, and the protein stability inside the BNNT was the result of the SmtA–BNNT vdW interaction and not of being trapped between frozen water molecules.

Figure 6.

Radial distribution function (RDF) of water molecules in the simulation box at different simulation times.

4. Conclusions

In summary, we investigated the encapsulation process of the protein SmtA in the boron nitride nanotube (BNNT) in an aqueous medium through molecular dynamics (MD) simulation. The normalized center-of-mass (CoM) distance between the protein and the BNNT (d/d0) and the SmtA–BNNT van der Waals (vdW) interaction energy decreased dramatically and reached approximate values of 0.2 and −189.63 kcal·mol–1, respectively. It was observed that the insertion process of SmtA into the BNNT occurred with no pause in the vicinity of the BNNT, which indicated that a strong SmtA–BNNT vdW interaction caused by hydrogen bonding between the nitrogen atoms of the BNNT and hydrogen atoms of the protein could pass the energy barrier caused by the hydrogen-bonding networks of water molecules accumulated at the entrance of the BNNT. According to the potential mean force obtained through a pulling process, it was revealed that the encapsulation process occurred automatically with the free energy of −160 kcal·mol–1. The significant change in the root mean square deviation (RMSD) before the complete insertion of protein inside the BNNT by 1.5 ns showed an intense conformational alteration in the protein as an effect of a strong SmtA–BNNT vdW interaction during the movement of the protein into the BNNT.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (2020M2D8A206983011). Furthermore, the financial supports of the Basic Science Research Program (2017R1A2B3009135) through the National Research Foundation of Korea are appreciated.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Maghsoudi S.; Shahraki B. T.; Rabiee N.; Fatahi Y.; Dinarvand R.; Tavakolizadeh M.; Ahmadi S.; Rabiee M.; Bagherzadeh M.; Pourjavadi A.; et al. Burgeoning polymer nano blends for improved controlled drug release: a review. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 4363. 10.2147/IJN.S252237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabiee N.; Ahmadvand S.; Ahmadi S.; Fatahi Y.; Dinarvand R.; Bagherzadeh M.; Rabiee M.; Tahriri M.; Tayebi L.; Hamblin M. R. Carbosilane dendrimers: Drug and gene delivery applications. J. Drug Delivery Sci. Technol. 2020, 59, 101879 10.1016/j.jddst.2020.101879. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maghsoudi S.; Shahraki B. T.; Rabiee N.; Afshari R.; Fatahi Y.; Dinarvand R.; Ahmadi S.; Bagherzadeh M.; Rabiee M.; Tayebi L.; et al. Recent Advancements in aptamer-bioconjugates: Sharpening Stones for breast and prostate cancers targeting. J. Drug Delivery Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 101146 10.1016/j.jddst.2019.101146. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chavoshi S.; Rabiee M.; Rafizadeh M.; Rabiee N.; Shamsabadi A. S.; Bagherzadeh M.; Salarian R.; Tahriri M.; Tayebi L. Mathematical modeling of drug release from biodegradable polymeric microneedles. Bio-Des. Manuf. 2019, 2, 96–107. 10.1007/s42242-019-00041-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nasr S. M.; Rabiee N.; Hajebi S.; Ahmadi S.; Fatahi Y.; Hosseini M.; Bagherzadeh M.; Ghadiri A. M.; Rabiee M.; Jajarmi V.; et al. Biodegradable Nanopolymers in Cardiac Tissue Engineering: From Concept Towards Nanomedicine. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 4205. 10.2147/IJN.S245936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arsawang U.; Saengsawang O.; Rungrotmongkol T.; Sornmee P.; Wittayanarakul K.; Remsungnen T.; Hannongbua S. How do carbon nanotubes serve as carriers for gemcitabine transport in a drug delivery system?. J. Mol. Graphics Modell. 2011, 29, 591–596. 10.1016/j.jmgm.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi M.; Mansouri M. R.; Rabiee N.; Hamblin M. R.. Carbon-Based Nanomaterials.In Advances in Nanomaterials for Drug Delivery: Polymeric, Nanocarbon, and Bio-inspired, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yoosefian M.; Etminan N. Density functional theory (DFT) study of a new novel bionanosensor hybrid; tryptophan/Pd doped single walled carbon nanotube. Phys. E 2016, 81, 116–121. 10.1016/j.physe.2016.03.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skandani A. A.; Al-Haik M. Reciprocal effects of the chirality and the surface functionalization on the drug delivery permissibility of carbon nanotubes. Soft Matter 2013, 9, 11645–11649. 10.1039/C3SM52126E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi M.; Mansouri M. R.; Rabiee N.; Hamblin M. R.. Advances in Nanomaterials for Drug Delivery; Morgan & Claypool Publishers, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Zhang J.; Chen M.; Gong H.; Thamphiwatana S.; Eckmann L.; Gao W.; Zhang L. A bioadhesive nanoparticle–hydrogel hybrid system for localized antimicrobial drug delivery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 18367–18374. 10.1021/acsami.6b04858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moseke C.; Hage F.; Vorndran E.; Gbureck U. TiO2 nanotube arrays deposited on Ti substrate by anodic oxidation and their potential as a long-term drug delivery system for antimicrobial agents. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2012, 258, 5399–5404. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2012.02.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernkop-Schnürch A.; Bratengeyer I.; Valenta C. Development and in vitro evaluation of a drug delivery system protecting from trypsinic degradation. Int. J. Pharm. 1997, 157, 17–25. 10.1016/S0378-5173(97)00198-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos M. A. D. S.; Da Silva P. B.; Spósito L.; De Toledo L. G.; Bonifacio B. V.; Rodero C. F.; Dos Santos K. C.; Chorilli M.; Bauab T. M. Nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems for control of microbial biofilms: a review. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 1179. 10.2147/IJN.S146195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toudeshkchoui M. G.; Rabiee N.; Rabiee M.; Bagherzadeh M.; Tahriri M.; Tayebi L.; Hamblin M. R. Microfluidic devices with gold thin film channels for chemical and biomedical applications: a review. Biomed. Microdevices 2019, 21, 93 10.1007/s10544-019-0439-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajebi S.; Rabiee N.; Bagherzadeh M.; Ahmadi S.; Rabiee M.; Roghani-Mamaqani H.; Tahriri M.; Tayebi L.; Hamblin M. R. Stimulus-responsive polymeric nanogels as smart drug delivery systems. Acta Biomater. 2019, 92, 1–18. 10.1016/j.actbio.2019.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nik A. B.; Zare H.; Razavi S. S.; Mohammadi H.; Torab-Ahmadi P.; Yazdani N.; Bayandori M.; Rabiee N.; Mobarakeh J. I. Smart drug delivery: Capping strategies for mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2020, 110115 10.1016/j.micromeso.2020.110115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farjadian F.; Moghoofei M.; Mirkiani S.; Ghasemi A.; Rabiee N.; Hadifar S.; Beyzavi A.; Karimi M.; Hamblin M. R. Bacterial components as naturally inspired nano-carriers for drug/gene delivery and immunization: Set the bugs to work?. Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36, 968–985. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2018.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottini M.; Bruckner S.; Nika K.; Bottini N.; Bellucci S.; Magrini A.; Bergamaschi A.; Mustelin T. Multi-walled carbon nanotubes induce T lymphocyte apoptosis. Toxicol. Lett. 2006, 160, 121–126. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2005.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G.; Cheng Y.; Mi D.; Li Z. A study on self-insertion of peptides into single-walled carbon nanotubes based on molecular dynamics simulation. Int. J. Mod. Phys. C 2005, 16, 1239–1250. 10.1142/S0129183105007856. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allen O.; áHill H. Immobilization of small proteins in carbon nanotubes: high-resolution transmission electron microscopy study and catalytic activity. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Comm. 1995, 1803–1804. [Google Scholar]

- Lewinski N.; Colvin V.; Drezek R. Cytotoxicity of nanoparticles. Small 2008, 4, 26–49. 10.1002/smll.200700595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.; Wu P.; Rousseas M.; Okawa D.; Gartner Z.; Zettl A.; Bertozzi C. R. Boron nitride nanotubes are noncytotoxic and can be functionalized for interaction with proteins and cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 890–891. 10.1021/ja807334b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M. L.; Zettl A. The physics of boron nitride nanotubes. Phys. Today 2010, 63, 34–38. 10.1063/1.3518210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Won C. Y.; Aluru N. R. Structure and dynamics of water confined in a boron nitride nanotube. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 1812–1818. 10.1021/jp076747u. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roosta S.; Nikkhah S. J.; Sabzali M.; Hashemianzadeh S. M. Molecular dynamics simulation study of boron-nitride nanotubes as a drug carrier: from encapsulation to releasing. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 9344–9351. 10.1039/C5RA22945F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mirhaji E.; Afshar M.; Rezvani S.; Yoosefian M. Boron nitride nanotubes as a nanotransporter for anti-cancer docetaxel drug in water/ethanol solution. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 271, 151–156. 10.1016/j.molliq.2018.08.142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mortazavifar A.; Raissi H.; Akbari A. DFT and MD investigations on the functionalized boron nitride nanotube as an effective drug delivery carrier for Carmustine anticancer drug. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 276, 577–587. 10.1016/j.molliq.2018.12.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H.; Wang Q.; Fan G.; Chu X. Theoretical study of boron nitride nanotubes as drug delivery vehicles of some anticancer drugs. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2018, 137, 104 10.1007/s00214-018-2284-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khatti Z.; Hashemianzadeh S. M. Boron nitride nanotube as a delivery system for platinum drugs: Drug encapsulation and diffusion coefficient prediction. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 88, 291–297. 10.1016/j.ejps.2016.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Si M.; Lang J. The roles of metallothioneins in carcinogenesis. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2018, 11, 107 10.1186/s13045-018-0645-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi S. Positive and negative regulators of the metallothionein gene. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 795–799. 10.3892/mmr.2015.3459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blindauer C. A.; Harrison M. D.; Parkinson J. A.; Robinson A. K.; Cavet J. S.; Robinson N. J.; Sadler P. J. A metallothionein containing a zinc finger within a four-metal cluster protects a bacterium from zinc toxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001, 98, 9593–9598. 10.1073/pnas.171120098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plimpton S. Fast Parallel Algorithms for Short-Range Molecular Dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 1995, 117, 1–19. 10.1006/jcph.1995.1039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey W.; Dalke A.; Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graphics 1996, 14, 33–38. 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tersoff J. New empirical approach for the structure and energy of covalent systems. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 6991–7000. 10.1103/PhysRevB.37.6991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.; Schulten K. Calculating potentials of mean force from steered molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 2004, 120, 5946–5961. 10.1063/1.1651473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfelder J. O.; Curtiss C. F.; Bird R. B.; Mayer M. G.. Molecular Theory of Gases and Liquids; Wiley: New York, 1964; Vol. 165. [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y.; Liu Y.-C.; Wang Q.; Shen J.-W.; Wu T.; Guan W.-J. On the spontaneous encapsulation of proteins in carbon nanotubes. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 2807–2815. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feller S. E.; Zhang Y.; Pastor R. W.; Brooks B. R. Constant pressure molecular dynamics simulation: the Langevin piston method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995, 103, 4613–4621. 10.1063/1.470648. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H.; Kong Y.; Cui D.; Ozkan C. S. Spontaneous insertion of DNA oligonucleotides into carbon nanotubes. Nano Lett. 2003, 3, 471–473. 10.1021/nl025967a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y.; Wang Q.; Liu Y.-C.; Wu T.; Chen Q.; Guan W.-J. Dynamic mechanism of collagen-like peptide encapsulated into carbon nanotubes. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 4801–4807. 10.1021/jp711392g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortazavifar A.; Raissi H.; Shahabi M. Comparative prediction of binding affinity of Hydroxyurea anti-cancer to boron nitride and carbon nanotubes as smart targeted drug delivery vehicles. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2019, 37, 4852–4862. 10.1080/07391102.2019.1567385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Peng G.; Li J.; Liang L.; Kong Z.; Wang H.; Jia L.; Wang X.; Zhang W.; Shen J.-W. Molecular dynamics study on the configuration and arrangement of doxorubicin in carbon nanotubes. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 262, 295–301. 10.1016/j.molliq.2018.04.097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J.-W.; Wu T.; Wang Q.; Kang Y. Induced stepwise conformational change of human serum albumin on carbon nanotube surfaces. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 3847–3855. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saadat Tabrizi N.; Vahid B.; Azamat J. Functionalized Single-atom Thickness Boron Nitride Membrane for Separation of Arsenite Ion from Water: A Molecular Dynamics Simulation Study. J. Phys. Chem. A 2020, 8, 843–856. [Google Scholar]

- Koide A.; Meath W.; Allnatt A. Molecular physics: an international journal at the interface between chemistry and physics. Mol. Phys. 1980, 39, 895–911. 10.1080/00268978000100771. [DOI] [Google Scholar]