Abstract

Febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES) is characterized by new onset refractory status epilepticus in a previously healthy child that is associated with poor cognitive outcomes and chronic epilepsy. Innate immune system dysfunction is hypothesized to be a key etiologic contributor, with a potential role for immunotherapy blocking pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1β and interleukin-6. We present a case of FIRES refractory to anakinra, an interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, subsequently treated with the ketogenic diet and tocilizumab, an interleukin-6 receptor antagonist, temporally associated with seizure cessation and a favorable 1-year outcome.

Keywords: status epilepticus, super refractory status epilepticus, febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome, anakinra, tocilizumab, neuroimmunology, antiseizure drugs, ketogenic diet, children

Introduction

Febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES) is marked by super refractory status epilepticus (SRSE) in previously healthy school-aged children preceded by a febrile illness 2 weeks to 24 hours prior to seizure onset. FIRES is a subcategory of new onset refractory status epilepticus (NORSE).1 Neuroimaging, neural autoantibodies, genetic, infectious, and metabolic studies are often normal.2 As seizures progress, MRI may show hippocampal and temporal T2 hyperintensities with atrophy.2 Potentially specific EEG features include delta-beta complexes resembling extreme delta brush (EDB) and prolonged focal fast activity.3 Seizures are progressive and refractory to antiseizure medications (ASMs) and first-line immunotherapies, including steroids, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) and plasma exchange. Ketogenic diet (KD) is efficacious in some cases.1 Outcomes are poor, with 12% mortality and two-thirds of patients acquiring cognitive disability. Nearly all surviving patients have refractory epilepsy.2

Pathogenesis is unknown, but a central role of innate immune system dysregulation is hypothesized. Some patients with FIRES have elevated CSF pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β and IL-6, and genetic variants in IL1RN, the gene encoding IL-1 receptor antagonist.4,5 In an index patient, blockade with an IL-1 receptor antagonist, anakinra, resulted in seizure cessation.4 Use of anakinra in patients with FIRES has been subsequently reported to be associated with decreased duration of intubation and hospital and intensive care unit stay.6 Tocilizumab, an IL-6 receptor antagonist, has been reported in 7 NORSE and 2 FIRES cases, but not with prior anakinra failure.7,8 We present a case of anakinra-refractory FIRES treated with ketosis and tocilizumab with temporally related cessation of SRSE and favorable 1-year outcome.

Case Report

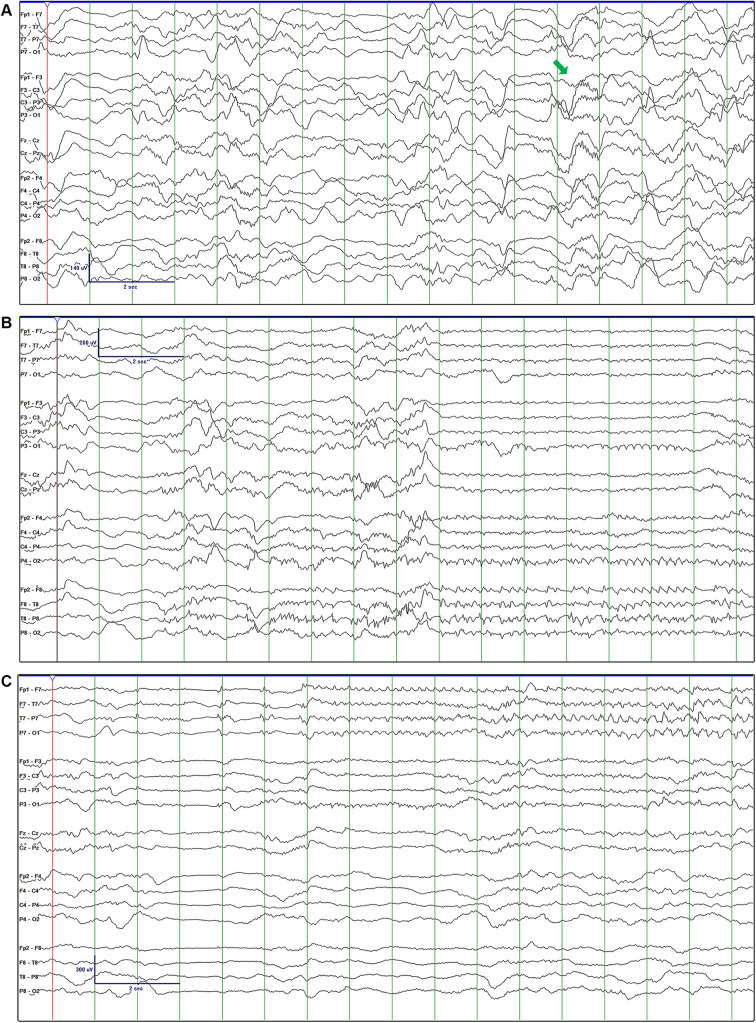

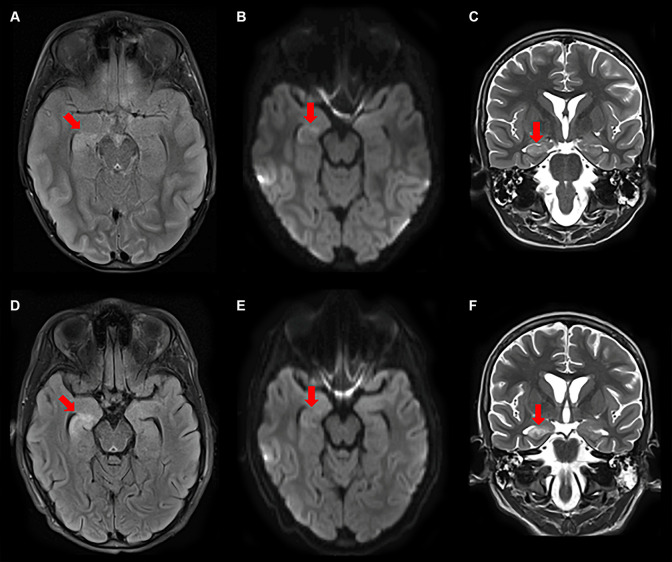

A previously healthy 6-year-old boy presented with focal seizures culminating in SRSE 1 week after a febrile illness, meeting criteria for FIRES.1 He initially had 2 clinical seizures marked by full body stiffening and left eye deviation. EEG showed at least 2 electrographic seizures per hour arising predominantly from the right and left temporal regions (Figure 1B and 1C) despite IV levetiracetam, fosphenytoin, phenobarbital and continuous midazolam infusion. Interictally, intermittent delta waves with overriding 15-16 Hz beta activity were observed, resembling interictal discharges described in other children with FIRES (Figure 1A).3 Initial CSF analysis was normal. MRI showed scattered nonspecific T2 hyperintensities. Two subsequent CSF analyses revealed 15 and 7 white blood cells/mm3 on day 2 and 17, respectively, with elevated neopterin of 91 nmol/L (reference 7-40 nmol/L). Serial MRIs (Figure 2) showed progressive T2/FLAIR hyperintensities with diffusion restriction in the right hippocampus. Serum and CSF autoimmune encephalopathy antibody panels (Mayo Medical Laboratories) were negative, except low-titer serum glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 (GAD65) (0.09 nmol/L) only after IVIg. Infectious studies included positive respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) nasopharyngeal PCR and elevated serum Mycoplasma pneumoniae IgM and IgG, with negative M. pneumonia CSF PCR and antibody levels. CSF metagenomic next generation sequencing was negative. Whole-exome sequencing was non-diagnostic.

Figure 1.

Initial EEG revealed delta-beta complexes (A). Electrographic seizures onset predominantly in the right temporal (B) and left temporal (C) regions.

Figure 2.

Serial MRIs on day 7 (A-C) and 16 (D-F) showed progressive T2 (C, F)/FLAIR (A, D) hyperintensities with diffusion restriction (B, E) in the right hippocampus and generalized atrophy.

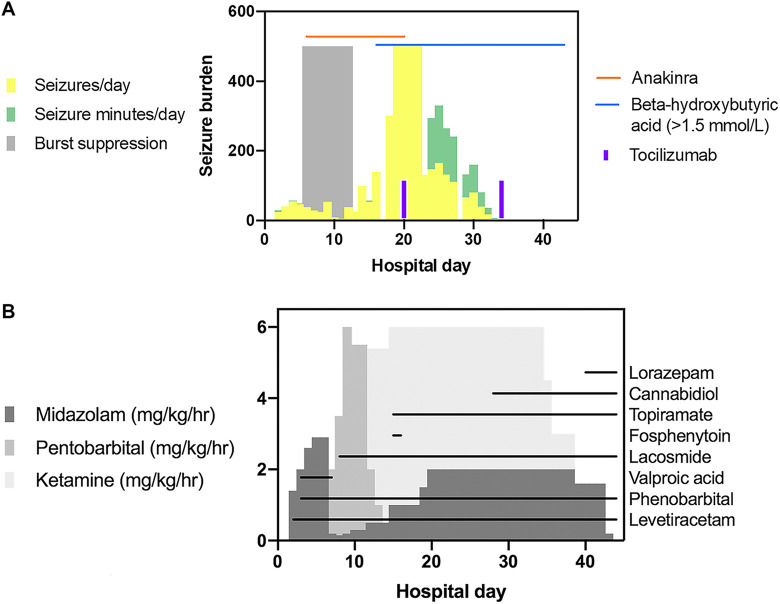

Seizures became near continuous prompting 2 trials of burst suppression and remained refractory to midazolam (2.9 mg/kg/hour), ketamine (100 mcg/kg/minute or 6 mg/kg/hour), pentobarbital (6 mg/kg/hour), IV methylprednisolone (30 mg/kg daily for 5 days), IVIg (2 g/kg over 2 days), and anakinra (titrated to 20 mg/kg/day, hospital day 6-20) (Figure 3). Maintenance ASMs were sequentially added, including levetiracetam (100 mg/kg/day), phenobarbital (13 mg/kg/day), valproic acid (40 mg/kg/day), lacosamide (20 mg/kg/day), topiramate (10 mg/kg/day), cannabidiol (20 mg/kg/day), and lorazepam (1.5 mg/kg/day) (Figure 3B). KD was initiated on day 14, and a beta-hydroxybutyric acid level of >1.5 mmol/L was obtained on day 16 and sustained until discontinuation on day 63 (Figure 3A). On day 17, CSF cytokine analysis showed elevated IL-6 (84, reference ≤25 pg/mL) and IL-8 (605, reference ≤205 pg/mL). Serum cytokines were normal. Tocilizumab 12mg/kg every 2 weeks was initiated on day 20, with 4 doses administered over 8 weeks. By day 23, seizure burden decreased, allowing for weaning of continuous infusions. Seizures did not recur with subsequent discontinuation of tocilizumab or KD.

Figure 3.

Seizure burden displayed as approximate seizures/day and daily seizure time (minutes/day) is summarized. Notably, seizure burden on days 19-22 was nearly continuous at times and challenging to quantify, and thus represented as 500 seizures and seizure minutes/day (A). Administration of immunotherapy, ketogenic diet, (A) continuous infusions, and maintenance anti-seizure medications is highlighted (B). There was a decrease in approximate seizures/day and daily seizure time (minutes/day) within 3 days of tocilizumab and 9 days of KD initiation (A). Decreased seizure burden allowed for weaning of continuous infusions (B).

At 1-year follow-up, he has approximately 0-1 seizures per day on 5 ASMs outside of times of illness and ASM weans. Current seizure semiology is described as a sensation of abdominal discomfort, behavioral arrest, and head deviation. Repeat MRI revealed right mesial temporal sclerosis in the area of prior T2/FLAIR signal abnormality. He attends school with an individualized education plan and has acquired behavioral dysregulation and inattention. IQ subsets for processing speed, performance, and verbal IQ are 60, 86, and 81, respectively. Given that his ASMs are likely contributing to his slow processing speed and seizures increase with medication weans, an epilepsy presurgical evaluation is planned.

Discussion

This case highlights the potential efficacy of tocilizumab in a child with FIRES refractory to anakinra. Despite prolonged SRSE, our patient experienced favorable seizure control and neuropsychiatric scores relative to prior reports.2 Tocilizumab was previously used in 7 adults with NORSE refractory to other immunotherapies, including rituximab, noting seizure cessation after 1 to 2 doses in 6 patients. Two patients experienced serious infections, including death in 1 case with sepsis that onset prior to tocilizumab administration.7 Two children with FIRES experienced a decrease in seizures after two 4mg/kg doses of tocilizumab without side effects.8

Given the multiple treatments received, causality of our patient’s improvement is uncertain, but tocilizumab and KD were most temporally associated with seizure resolution. IL-6 elevation was CNS-restricted, prohibiting non-invasive trending of IL-6 blockade. Tocilizumab-associated side effects were not noted in our patient; however, infections in the NORSE series7 suggest proceeding with caution. Further controlled treatment trials of tocilizumab in FIRES are needed to understand its safety, efficacy, and treatment duration.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Coral M. Stredny, MD  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1176-640X

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1176-640X

Arnold J. Sansevere, MD  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7805-8948

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7805-8948

References

- 1. Gaspard N, Hirsch LJ, Sculier C, et al. New-onset refractory status epilepticus (NORSE) and febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES): state of the art and perspectives. Epilepsia. 2018;59(4):745–752. doi:10.1111/epi.14022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kramer U, Chi CS, Lin KL, et al. Febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES): pathogenesis, treatment, and outcome: a multicenter study on 77 children. Epilepsia. 2011;52(11):1956–1965. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03250.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Farias-Moeller R, Bartolini L, Staso K, Schreiber JM, Carpenter JL. Early ictal and interictal patterns in FIRES: the sparks before the blaze. Epilepsia. 2017;58(8):1340–1348. doi:10.1111/epi.13801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kenney-Jung DL, Vezzani A, Kahoud RJ, et al. Febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome treated with anakinra. Ann Neurol. 2016;80(6):939–945. doi:10.1002/ana.24806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clarkson BD, LaFrance-Corey RG, Kahoud RJ, Farias-Moeller R, Payne ET, Howe CL. Functional deficiency in endogenous interleukin-1 receptor antagonist in patients with febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES). Ann Neurol. 2019;85(4):526–537. doi:10.1002/ana.25439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lai YC, Muscal E, Wells E, et al. Anakinra usage in febrile infection related epilepsy syndrome: an international cohort. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2020. doi:10.1002/acn3.51229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jun JS, Lee ST, Kim R, Chu K, Lee SK. Tocilizumab treatment for new onset refractory status epilepticus. Ann Neurol. 2018;84(6):940–945. doi:10.1002/ana.25374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cantarin-Extremera V, Jimenez-Legido M, Duat-Rodriguez A, et al. Tocilizumab in pediatric refractory status epilepticus and acute epilepsy: experience in two patients. J Neuroimmunol. 2020;340:577142 doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2019.577142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]