Abstract

Since the beginning of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, the responses of countries to emerging infectious diseases have altered dramatically, increasing the demand for health-care practitioners. Telehealth (TH) applications could have an important role in supporting public health precautions and the control of the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. This review summarizes the existing literature on the current status of TH applications used during COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia and discusses the extent to which TH can support public health measures. TH mobile applications (e.g., Seha, Mawid, Tawakklna, Tabaud, and Tetamman) have found effective tools to facilitate delivering healthcare to persons with COVID-19, and tracking of COVID-19 patients. TH has been essential in the control of the spread of COVID-19 and has helped to flatten the growth curve in Saudi Arabia. Further research is needed to explore the impact of TH applications on the progression of COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia.

Keywords: Care coordination, COVID-19, telehealth, telemedicine

Introduction

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has already claimed thousands of lives, incapacitated even more, and infected >185 nations. Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the response of nations to emerging infectious diseases has altered dramatically, increasing the demand on health-care practitioners.[1,2] Health-care authorities around the world are continue to discuss preventive measures that governments should consider appropriate to halt the spread of COVID-19. In Saudi Arabia, the Ministry of Health (MOH) recently devised a strategy for tackling the disease. This strategy includes the use of current telehealth (TH) applications to screen suspected cases, provide long-distance care, and track COVID-19 patients.[2,3,4,5,6] Various terminologies are used in medical agencies to refer to specific applications for TH, and these are outlined in Table 1.[7] Although no TH technology can be developed overnight, the MOH in Saudi Arabia has been operating extensively on TH throughout the pandemic.[2,6,8,9,10] The aim of this paper is to summarize existing literature about the current status concerning the use of TH applications during COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia and discuss the extent to which TH is capable of supporting public health measures.

Table 1.

Terminologies of telehealth applications

| Terminology | Definitions |

|---|---|

| TH | Using electronic information and communication technologies to support distance healthcare, which allows healthcare professionals and long-distance patients to exchange information and support access to healthcare services[7] |

| Telemonitoring | Using electronic technologies, equipment, and sensors to transfer clinical data from patient settings to the healthcare providers in clinical settings[7] |

| Telemedicine | Using e-health and communications networks for the delivery of healthcare services and medical education from one geographical location to another[7] |

| Telehomecare | Using electronic information and communication technologies to support the care and treatment between a patient’s home and professional healthcare settings[7] |

| Teleconsultation | Using videoconferencing and webcams to connect the healthcare provider with patients, allowing the healthcare provider to assess, diagnose, and treat patients[7] |

| Tele-education | Using web-based platforms to educate patients about disease management[7] |

TH=Telehealth

Telehealth to Mitigate the Spread of COVID-19

Studies regarding the use of TH have shown that it has a positive impact on the delivery of health-care services.[11,12,13,14] COVID-19 is transmitted quickly, and each infected case could spread the disease to more than one person, which means an exponential and very high rate of increase.[15] The MOH in Saudi Arabia has encouraged people to use mobile applications rather than visit primary care clinics during the outbreak. TH has been central in the role of primary health services to help mitigate the spread of COVID-19.[16]

Telehealth in Saudi Arabia

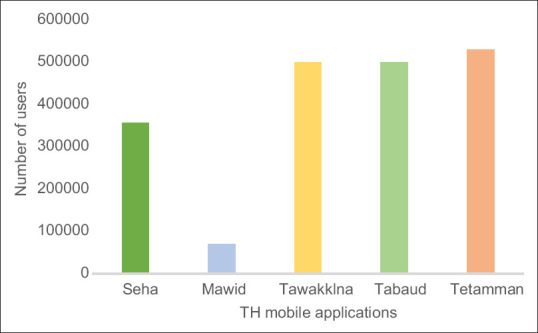

The MOH in Saudi Arabia has recently introduced additional features to the current TH services, which have been effectively incorporated into the provision of healthcare using mobile applications (e.g., Seha, Mawid, Tawakklna, Tabaud, and Tetamman) to cope with the pandemic,.[9,16,17] A cross-sectional survey on the knowledge, attitude, and practice of parents to TH mobile applications (e.g., Seha and Mawid) was recently conducted on 402 Saudi and non-Saudi parents. The study reported that 346/402 (86%) of the respondents acknowledged the potential benefits of these mobile applications, and had used them before to book appointments for their children.[18] Another public survey with 781 participants, showed that 392/781 (51%) of the users were satisfied with the current services of TH mobile applications (e.g., Seha and Mawid).[17] As demonstrated in Figure 1, there were >2 million users for the TH applications established by the MOH.[5,6] This was a considerable facilitator that shows that the Saudi health-care system had been fully prepared to deal with such outbreaks as COVID-19.

Figure 1.

Numbers of current users of telehealth mobile applications

Capabilities and Advantages of Telehealth Applications during the COVID-19 Pandemic

The MOH established a clear vision of how to improve health-care services accessibility across the kingdom following the Saudi Vision 2030 plan that stressed the importance of adopting and developing a national TH network.[2,4,19,20] Across all health-care agencies in the kingdom, TH has been found efficient in reducing patient expense for health-care services provided, including online consultations, prescription refills, and follow-ups. All of these services are accessible with a tap of the finger leading one to a specific health-care provider.[20] TH mobile applications have also allowed the monitoring of the progression of chronic condition and minimized nonessential hospital visits during COVID-19, especially for children and vulnerable people.[18,21,22,23] In addition, TH has helped patients to avoid nosocomial infections common in hospital settings. The nature of COVID-19 transmission[24] is still being debated; however, previous studies have found that nosocomial infections have played an important role in coronavirus transmissions.[25,26] TH can prevent this since it promotes self-isolation, which is in line with the recommendations of the World Health Organization.[27,28] Furthermore, symptoms evaluation through TH mobile apps is found to be vital in the detection and surveillance of COVID-19.[5,6]

Role of Telehealth in Care Coordination

The COVID-19 pandemic has illustrated that TH is an excellent facilitator for care coordination and care delivery in Saudi Arabia.[9,10] However, TH services in Saudi Arabia are yet to reach expectation, and hence, there is a pressing need for the development of simpler and more interactive TH applications.[6,9,16,29] This development could be achieved by evaluating user satisfaction over time, ensuring that applications are being used properly,[30] and optimizing the design of the applications, taking into consideration cultural and behavior factors against the use of technology.[31]

Hajj Season versus COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia

Historically, health authorities in Saudi Arabia have been prepared to face any potential spread of infectious diseases associated with mass gatherings (e.g., the Hajj season).[32] Studies have shown that this inevitable overcrowding is mostly associated with travel-related infections.[33,34] Given all the expertise that has accrued over the years, the Saudi Arabian health authorities are familiar with the way the massing of people can result in a pandemic like COVID-19.[33,34] The concurrence of COVID-19 with the Hajj season provides an extra indication of the insights and benefits that TH could provide care delivery during such a crisis. TH seems to be changing the nature of care delivery in Saudi Arabia since the majority of residents and noncitizens, can access the services quickly and easily.[8,35] Consequently, it seems that TH can make an essential contribution in the COVID-19 pandemic, by mitigating the risk of infection and helping to flatten the growth curve.

Conclusion

TH applications have been found to be vital in supporting public health precautions taken by the MOH in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 epidemic. TH contributions in the COVID-19 pandemic has played an essential role in mitigating the risk of COVID-19 infection. Further rigorous research is needed to develop the implementation and design of TH, and explore the impact of TH applications on the progress of COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Alaboudi A, Atkins A, Sharp B, Balkhair A, Alzahrani M, Sunbul T. Barriers and challenges in adopting Saudi telemedicine network: The perceptions of decision makers of healthcare facilities in Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health. 2016;9:725–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ministry of Health (Saudi Arabia): National E-Health Strategy; 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 10]. Available from: https://wwwmohgovsa/en/Ministry/nehs .

- 3.Hollander JE, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1679–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2003539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Mahalli AA, El-Khafif SH, Al-Qahtani MF. Successes and challenges in the implementation and application of telemedicine in the eastern province of Saudi Arabia. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2012;9:1–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ministry of Health (Saudi Arabia): COVID-19 Daily Briefing 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 10]. Available from: https://wwwmohgovsa/en/Ministry/MediaCenter .

- 6.Saudi Center for Disease Prevention and Control: (Covid-19) Disease Interactive Dashboard 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 10]. Available from: https://covid19cdcgovsa/daily-updates .

- 7.Alghamdi SM, Janaudis-Ferreira T, Alhasani R, Ahmed S. Acceptance, adherence and dropout rates of individuals with COPD approached in telehealth interventions: A protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e026794. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Health Information Center: Achievement Percentage; 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 10]. Available from: https://nhicgovsa/en .

- 9.Muzafar S, Jhanjhi N. Success Stories of ICT Implementation in Saudi Arabia Employing Recent Technologies for Improved Digital Governance: IGI Global. 2020:151–63. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rahman R, Al-Borie HM. Strengthening the Saudi Arabian healthcare system: Role of Vision 2030. Int J Healthcare Manag. 2020;13:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shati A. mhealth applications developed by the ministry of health for public users in ksa: A persuasive systems design evaluation. Health Inform Int J. 2020;9:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alkhudairi B. Technology Acceptance Issues for a Mobile Application to Support Diabetes Patients in Saudi Arabia. University of Brighton; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alajmi D, Khalifa M, Jamal A, Zakaria N, Alomran S, El-Metwally A, et al. The Role and use of Telemedicine by Physicians in Developing Countries: A Case Report from Saudi Arabia Transforming Public Health in Developing Nations: IGI Global. 2015:293–308. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albarrak AI, Mohammed R, Almarshoud N, Almujalli L, Aljaeed R, Altuwaijiri S, et al. Assessment of physician's knowledge, perception and willingness of telemedicine in Riyadh region, Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health. 2019;13:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2019.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gates B. Responding to COVID-19 - A once-in-a-century pandemic? N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1677–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2003762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jalabneh R, Zehra Syed H, Pillai S, Hoque Apu E, Hussein MR, Kabir R, et al. Use of mobile phone apps for contact tracing to control the COVID-19 pandemic: A literature review.Anwarul, use of mobile phone apps for contact tracing to control the COVID-19 pandemic. Literature Rev. 2020;5:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alshammari F. Perceptions, preferences and experiences of telemedicine among users of Information and communication technology in Saudi Arabia. J Health Inform Dev Ctries. 2019;13:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alruzaiza SA, Mahrous RM. Assessment of knowledge, attitude, and practice on level of awareness among pediatric emergency department visitors-Makkah City, Saudi Arabia: Cross-sectional study. Int J Psychosoc Rehabil. 2020;24:5186–202. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alkhateeb AF, AlAmri JM, Hussain MA, editors. Industrial & Systems Engineering Conference (ISEC) IEEE; 2019. Healthcare Facility Variables Important to Biomedical Staffing in Line with 2030 Saudi Vision, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al Otaibi MN. Internet of things (IoT) Saudi Arabia healthcare systems: State-Of-the-art, future opportunities and open challenges. J Health Inform Dev Ctries. 2019;13:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alqahtani JS, Oyelade T, Aldhahir AM, Alghamdi SM, Almehmadi M, Alqahtani AS, et al. Prevalence, Severity and mortality associated with COPD and Smoking in patients with COVID-19: A rapid systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0233147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alsharari AF, Aroury AM, Dhiabat MH, Alotaibi JS, Alshammari FF, Alshmemri MS, et al. Critical care nurses' perception of care coordination competency for management of mechanically ventilated patients. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29:1341–51. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Al-Sofiani ME, Alyusuf EY, Alharthi S, Alguwaihes AM, Al-Khalifah R, Alfadda A. Rapid implementation of a diabetes telemedicine clinic during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak: Our protocol, experience, and satisfaction reports in Saudi Arabia. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2020;14:1–10. doi: 10.1177/1932296820947094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bai Y, Yao L, Wei T, Tian F, Jin DY, Chen L, et al. Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;14:1406–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Memish ZA, Cotten M, Meyer B, Watson SJ, Alsahafi AJ, Al Rabeeah AA, et al. Human infection with MERS coronavirus after exposure to infected camels, Saudi Arabia, 2013. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1012–5. doi: 10.3201/eid2006.140402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oboho IK, Tomczyk SM, Al-Asmari AM, Banjar AA, Al-Mugti H, Aloraini MS, et al. 2014 MERS-CoV outbreak in Jeddah-a link to health care facilities. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:846–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alumran A. Role of precautionary measures in containing the natural course of novel coronavirus disease. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2020;13:615–20. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S261643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization: Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic; 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 10]. Available from: https://wwwwhoint/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public .

- 29.Karan A. To control the covid-19 outbreak, young, healthy patients should avoid the emergency department. BMJ. 2020;368:m1040. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chandran D, Aljohani N. The role of Cultural Factors on Mobile Health Adoption: The Case of Saudi Arabia. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alghamdi SM, Al Rajeh A. Top Ten Behavioral Change Techniques Used in Telehealth Intervention with COPD: A Systematic Review Respiratory Care. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shafi S, Booy R, Haworth E, Rashid H, Memish ZA. Hajj: Health lessons for mass gatherings. J Infect Public Health. 2008;1:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahmed QA, Arabi YM, Memish ZA. Health risks at the Hajj. Lancet. 2006;367:1008–15. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68429-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.El Bashir H, Rashid H, Memish ZA, Shafi S Health at Hajj and Umra Research Group. Meningococcal vaccine coverage in Hajj pilgrims. Lancet. 2007;369:1343. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60625-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alsulame K, Khalifa M, Househ M. E-health status in Saudi Arabia: A review of current literature. Health Policy Technol. 2016;5:204–10. [Google Scholar]