As Canada has moved out of full public health lock-down to restart the economy, we know that flares of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infections causing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) will need to be promptly detected to mitigate the second and third outbreak waves in the coming months. During the coming year or two, it is likely that the vaccines and antiviral drugs needed to combat this pandemic will still be going through development, testing, and production, and will not yet be ready for full implementation. During this vulnerable period, reliable and valid testing of acute cases will remain an important means to control community spread.

However, current COVID-19 results from nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabbing suggest that, overall, the testing procedures used in Canada need improvement. As of June 1, 2020, 263 074 tests had been conducted on 237 747 persons in Alberta.1 And yet, despite its having one of the highest per capita testing rates in North America, Alberta had only 7044 confirmed cases of COVID-19 (or a positive rate of 3%), which included those cases that entered from outside the country at the start of the pandemic. While the surge of cases in the province (most occurring in Calgary) reached an apex on April 23, 2020, steady daily cases have continued to be reported since May 3, 2020, which suggests ongoing undetected community spread.2 So why are the tests not identifying more of these cases?

Factors affecting accurate testing

There are many reasons for a patient to have a negative result from a test using reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), as outlined in Table 1. In Canada, true negative tests are certainly plausible during the spring season. However, it is unlikely that most of the mild to moderate flulike illnesses reported from April to June this year were owing to something other than SARS-CoV-2 infection. Typically, viral respiratory infections in Canada are at a low ebb outside of the annual influenza season (ie, November to March). Domestic arthropod-borne infections that can create symptoms similar to those of COVID-19 (eg, Jamestown Canyon virus, West Nile virus, or Rocky Mountain spotted fever) are not common in Canada and occur primarily in late spring and summer months.3

Table 1.

Causes of a negative RT-PCR COVID-19 test result (nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal swabbing)

| RESULT | CAUSE |

|---|---|

| a. True negative | Properly conducted test in a patient with another viral infection or condition |

| b. False negative | Delayed testing of patient beyond the time when the virus is in the upper airway |

| c. False negative | Sampling for virus has been inadequate (a throat swab is less effective than a nasopharyngeal swab) |

| d. False negative | Transport of specimen to laboratory is faulty (delays, integrity of specimen, etc) |

| e. False negative | Insensitivity inherent in the testing platform (eg, manufacturer shortcomings) |

COVID-19—coronavirus disease 2019, RT-PCR—reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction.

Although jurisdictions in other countries have cited varying false-negative rates, some as high as 50%,4 provincial systems, such as Alberta’s laboratory testing process, have yielded 100% accuracy, as confirmatory testing by Canada’s National Microbiology Laboratory has shown.5 Moreover, the local-provincial-federal system of specimen collection and transport to centralized laboratory sites has been reliable during several decades in its testing for other infectious diseases. Thus, the timing and technique of sampling during clinical encounters could potentially be the factors most amenable to improvement. Those patients with severe acute COVID-19 will be hospitalized and tested immediately; however, testing in the community is another story.

While nasopharyngeal swabbing requires trust between the provider and the patient to perform, the swab is unlikely to miss sampling the infected mucosa, compared with either a deep nasal or an oropharyngeal (throat) swab.6 Canadian family physicians have a long history of competently conducting nasopharyngeal testing during the annual influenza season, including formal participation in the FluWatch Sentinel Practitioner ILI Surveillance Program.7 Deep nasal swabbing was quickly abandoned by Alberta Health Services following a preliminary study6 showing it to be less reliable, especially when used by nonphysicians at large drive-through assessment centres. Owing to a global shortage of nasopharyngeal swabs, Canadian jurisdictions have been forced to use the alternative swabbing techniques.8 Until there is improvement in the supply of nasopharyngeal swabs within Canada, this factor cannot be addressed.

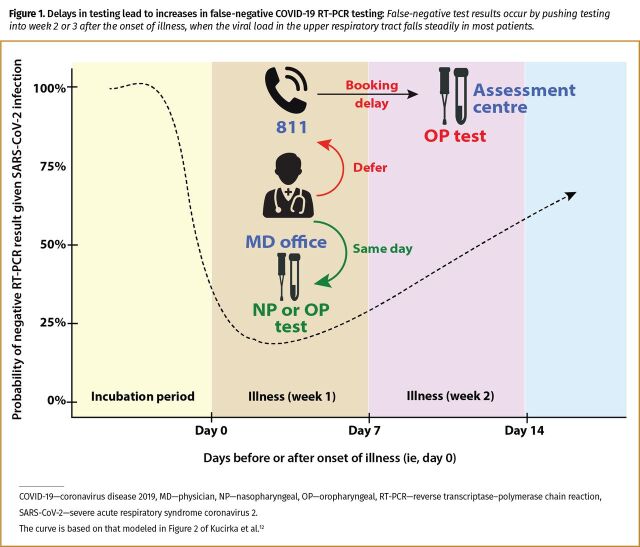

The only factor that can be substantially improved at the population level is to reduce the time between the onset of illness and high-quality oropharyngeal (or nasopharyngeal) testing, so as to ensure that sampling occurs during the optimal time for detecting the virus in the upper respiratory tract.9-11 Although there is limited published information on the testing period with the lowest number of false-negative results, Kucirka and colleagues have modeled that the best testing period from the onset of any symptoms is within the first 7 to 10 days.12 Testing someone before symptom onset or more than 10 days after symptom onset risks a higher likelihood of false-negative results. Systemic delays in the booking of patients for testing unnecessarily increases the number of false-negative results, and can be addressed by returning to a decentralized process that reintroduces family medicine clinics as testing sites for moderately ill cases (Figure 1).12

No time to wait when the testing window is narrow

The following scenario illustrates the problem with delays when the system relies on an ad hoc centralized process for COVID-19 testing, such as currently exists in Alberta.13 During the first 3 weeks of April 2020, one encountered patients with several symptoms characteristic of mild to moderate COVID-19.14 After dialing 811 or going online to reach Health Link, Alberta Health Services’ 24-hour health advice line, to book an appointment, many patients waited between 3 and 14 days (averaging 5 days) to be tested. The results from all these patients were negative. Thus, suspected mild to moderate COVID-19 cases were consistently being tested beyond 7 days from onset of symptoms, when the risk of a false-negative RT-PCR test result increases substantially.12 Up to this point in the outbreak, the only positive COVID-19 cases encountered were those patients discharged from hospital after a severe clinical course and requiring follow-up in the community. The test results of all suspected cases sent to the drive-through testing centres were negative.

Figure 1.

Delays in testing lead to increases in false-negative COVID-19 RT-PCR testing: False-negative test results occur by pushing testing into week 2 or 3 after the onset of illness, when the viral load in the upper respiratory tract falls steadily in most patients.

During the third week of April 2020, 3 patients called our medical clinic requesting to be tested for possible infection with SARS-CoV-2. All 3 were unrelated community cases with moderate symptoms, including fever, sweats, muscle aches, and mild cough or chest congestion without shortness of breath. The onset of symptoms was within the previous 6 days. All had already called 811 and were still waiting for an appointment to have an oropharyngeal swab at one of the government-run assessment centres. Although family medicine clinics in Alberta were not provided viral testing kits for COVID-19 screening, our clinic had a few nasopharyngeal testing kits left over from the previous year’s influenza surveillance program. All 3 patients were brought into the clinic immediately for testing, and 2 of the 3 patients received positive test results for SARS-CoV-2 infection the following day.

One of the confirmed cases was a parent with a spouse and 2 children at home with similar flulike symptoms. The positive case and the older child had symptoms on the same day. The spouse developed symptoms a few days later, and the younger child shortly thereafter. Because our remaining supply of swab kits was limited, we were unable to test the rest of the family; we suggested that they assume themselves to be infected and self-isolate. The parent booked the 3 untested family members through the 811 centralized booking process and waited 7 more days to be tested at a drive-through assessment centre. The test result for the older child with the most severe symptoms came back negative, the spouse’s result came back as indeterminate (and was later classified as positive), and the test result for the younger child with the mildest symptoms was positive. Subsequent COVID-19 serology test results for the RT-PCR negative and indeterminate cases were later found to also be positive. This situation reinforces the observation that the window for reliably using RT-PCR testing and avoiding false-negative results is narrow—7 to 10 days from the onset of illness.9-12

Decentralize the process for more accurate and timely tests

A number of factors might cause unnecessary delays in testing through a centralized booking system, including but not limited to a communication choke point that leads to long wait times (eg, 811), problems with surge capacity for doing tests (eg, insufficient staff at different times of the day or week), and ineffectual triaging that does not exclude inappropriate cases for testing. The last factor has been well documented through the debriefing of patients who received testing in the past. Several patients with chronic sinus congestion, allergic rhinosinusitis, mild asthma, or other nonspecific upper respiratory symptoms for the previous 2 to 8 weeks were still triaged to be tested at an assessment centre. None of these chronic cases should have been booked for COVID-19 swabs, and such bookings probably contribute to those with acute symptoms having to wait longer than is appropriate.

What is worse than randomly testing a group of asymptomatic people with no recent cold or flulike illness is to systemically test all symptomatic patients beyond the window period when a COVID-19 RT-PCR test result would likely be positive. While one might pick up asymptomatic infections in the first group, there will likely be no cases found in those with resolving COVID-19 infections. If one is testing symptomatic patients beyond 7 to 10 days from the onset of illness, then the RT-PCR test result has a greater probability of being negative owing to clearance of the virus from the upper airway (Figure 1).12 The current approach of testing with systemic delays will only serve to ensure that community spread continues mostly undetected in the coming months.

As the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic passes over various Canadian communities, it seems appropriate to consider moving from a centralized to a decentralized approach to COVID-19 testing that is better aligned with community-based family practices. With a decentralized approach, sporadic cases with nonspecific upper respiratory infection symptoms will present to primary care centres, where physicians should be able to immediately test their patients as part of normal medical care. This was the normal approach before the onset of the pandemic, and one that has worked quite well during annual influenza seasons over several decades. Public health officials will still want to do widespread surveillance testing of staff and residents living or working in close quarters in high-risk locations such as nursing homes, hospitals, prisons, group homes, meat-packing plants, fulfilment centres, and so forth.

However, if we want to better characterize community spread during the lull following the first wave of the COVID-19 outbreak, we need to test more patients in a timely manner within 7 to 10 days from the onset of any flulike symptoms. Only when an approved serology test is disseminated throughout Canada15 will we be able to determine the full extent to which the current testing strategy has missed most mild and asymptomatic community cases. Until then, centralized assessment centres could reduce unnecessary delays by declining to test anyone who, at the time of their test appointment, has had symptoms longer than 7 days. Doing so would slash the backlog and move acutely ill patients up in the queue, so that they can be tested, ideally, within 24 to 48 hours of calling 811.

In addition, provincial governments could restock medical offices with swabs (oropharyngeal or nasopharyngeal, or both) and transport media kits to allow same-day testing.

Although this analysis has focused on Alberta, the basic premise is the same for all Canadian provinces. We need to return to a less centralized process of patient testing by increasing the number of access points within the health care system. By doing more timely testing, we can reduce the number of COVID-19 RT-PCR false-negative test results—a number that will only be confirmed by future seroprevalence studies.

Footnotes

This article was submitted on June 2, 2020.

Competing interests

None declared

The opinions expressed in commentaries are those of the authors. Publication does not imply endorsement by the College of Family Physicians of Canada.

This article has been peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Government of Alberta [website] . Update 80: COVID-19 pandemic in Alberta (June 1 at 6:15 p.m.). Edmonton, AB: Government of Alberta; 2020. Available from: https://www.alberta.ca/release.cfm?xID=7150077CEB4C6-B2B6-DB3C-C3AF3B209F64DA9A. Accessed 2020 Jun 2. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Government of Alberta [website] . COVID-19 Alberta statistics: interactive aggregate data on COVID-19 cases in Alberta, Jun 01, 2020 [archived]. Edmonton, AB: Government of Alberta; 2020. Available from: https://web.archive.org/web/20200602212403/https://www.alberta.ca/stats/covid-19-alberta-statistics.htm. Accessed 2020 Jun 2. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kulkarni MA, Berrang-Ford L, Buck PA, Drebot MA, Lindsay LR, Ogden NH. Major emerging vector-borne zoonotic diseases of public health importance in Canada. Emerg Microbes Infect 2015;4(6):e33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.West CP, Montori VM, Sampathkumar P. COVID-19 testing: the threat of false-negative results. Mayo Clin Proc 2020;95(6):1127-9. Epub 2020 Apr 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erdmann R; COVID-19 Scientific Advisory Group . Rapid response report: comparison of testing characteristics for RT-PCR using different swab methods. Edmonton, AB: Alberta Health Services; 2020. Available from: https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/info/ppih/if-ppih-covid-19-sag-comparison-of-testing-sites-rapid-review.pdf. Accessed 2020 Jun 2. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang X, Tan L, Wang X, Liu W, Lu Y, Cheng L, et al. Comparison of nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs for SARS-CoV-2 detection in 353 patients received tests with both specimens simultaneously. Int J Infect Dis 2020;94:107-9. Epub 2020 Apr 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Government of Canada [website] . FluWatch Sentinel Practitioner ILI Surveillance Program. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2018. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/flu-influenza/influenza-surveillance/influenza-sentinel-recruiters.html. Accessed 2020 Jun 2. [Google Scholar]

- 8.LeBlanc JJ, Heinstein C, MacDonald J, Pettipas J, Hatchette TF, Patriquin G. A combined oropharyngeal/nares swab is a suitable alternative to nasopharyngeal swabs for the detection of SARS-CoV-2. J Clin Virol 2020;128:104442. Epub 2020 May 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pan Y, Zhang D, Yang P, Poon LLM, Wang Q. Viral load of SARS-CoV-2 in clinical samples. Lancet Infect Dis 2020;20(4):411-2. Epub 2020 Feb 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zou L, Ruan F, Huang M, Liang L, Huang H, Hong Z, et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med 2020;382(12):1177-9. Epub 2020 Feb 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He X, Lau EHY, Wu P, Deng X, Wang J, Hao X, et al. Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. Nat Med 2020;26(5):672-5. Epub 2020 Apr 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kucirka LM, Lauer SA, Laeyendecker O, Boon D, Lessler J. Variation in false-negative rate of reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction-based SARS-CoV-2 tests by time since exposure. Ann Intern Med 2020;173(4):262-7. Epub 2020 May 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Government of Alberta [website] . Symptoms and testing. COVID-19 testing is available to all Albertans with symptoms, close contacts of confirmed cases and those linked to an outbreak. Edmonton, AB: Government of Alberta; 2020. Available from: https://www.alberta.ca/covid-19-testing-in-alberta.aspx. Accessed 2020 Nov 8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alberta Health Services [website] . Novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Frequently asked questions—staff. Edmonton, AB: Alberta Health Services; 2020. Available from: https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/info/ppih/if-ppih-ncov-2019-staff-faq.pdf. Accessed 2020 May 19. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Canadian Press . Health Canada approves serological test to detect COVID-19 antibodies. Toronto Star 2020. May 12. Available from: https://web.archive.org/web/20200521224834/https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2020/05/12/health-canada-approves-serological-test-to-detect-covid-19-antibodies.html. Acccessed 2020 May 21.